Professional Documents

Culture Documents

"Tupy or Not Tupy?" Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

"Tupy or Not Tupy?" Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

Uploaded by

DavidCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Rizal, Jose. 1963. Rizal Correspondence With Fellow ReformistsDocument401 pagesRizal, Jose. 1963. Rizal Correspondence With Fellow Reformistsordinaireangelo100% (1)

- Case Analysis of Administrative Law (Himmat Lal Shah V Commissioner of PoliceDocument18 pagesCase Analysis of Administrative Law (Himmat Lal Shah V Commissioner of PoliceShubham PhophaliaNo ratings yet

- David Craven - Abstract and Third WorldDocument24 pagesDavid Craven - Abstract and Third WorldBrigitta Isabella100% (1)

- 2022 - America Indigena And...Document29 pages2022 - America Indigena And...dorotinskyNo ratings yet

- Trump V House Select NARA DeclarationDocument57 pagesTrump V House Select NARA DeclarationFile 411No ratings yet

- Capitalism and Accounting in The Dutch East-India Company 1602-16Document538 pagesCapitalism and Accounting in The Dutch East-India Company 1602-16Saarvin சர்வின் 李在山 سرفينNo ratings yet

- Gilbert, McKinney, Roberson IndictmentDocument34 pagesGilbert, McKinney, Roberson IndictmentIvana HrynkiwNo ratings yet

- Cultural Cannibalism and Tropicalia An Alternative Modernism in Brazil - EditedDocument20 pagesCultural Cannibalism and Tropicalia An Alternative Modernism in Brazil - EditedDalvin Jr.No ratings yet

- Antropofagia Cultural CannibalismDocument8 pagesAntropofagia Cultural CannibalismLuisa MarinhoNo ratings yet

- Abaporu TropicalistaDocument18 pagesAbaporu Tropicalistalis gomesNo ratings yet

- Is It Possible To Decolonize The Concept of Cultural Antropophagy. MARIA INIGO CLAVODocument5 pagesIs It Possible To Decolonize The Concept of Cultural Antropophagy. MARIA INIGO CLAVOTatiane CovaNo ratings yet

- Antropofagia Cultural Cannibalism PDFDocument8 pagesAntropofagia Cultural Cannibalism PDFSara ArosioNo ratings yet

- Mosquera, Gerardo - Takeoff - Arte Desde América Latina - y Otros Pulsos GlobalesDocument5 pagesMosquera, Gerardo - Takeoff - Arte Desde América Latina - y Otros Pulsos GlobalesPaola PeñaNo ratings yet

- Brown University, 5.3 Modern Art WeekDocument9 pagesBrown University, 5.3 Modern Art Weekjeronimo_pizarroNo ratings yet

- Ab psr-2Document7 pagesAb psr-2api-709033375No ratings yet

- 09 GarciaCanclini MulticulturalismDocument5 pages09 GarciaCanclini MulticulturalismStergios SourlopoulosNo ratings yet

- 05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Document25 pages05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Anamaria Garzon MantillaNo ratings yet

- Cangoma Calling Spirits and Rhythms of FDocument27 pagesCangoma Calling Spirits and Rhythms of Fmyahaya692No ratings yet

- Leigh Sharman, Russell. - The Invention of Fine Art PDFDocument24 pagesLeigh Sharman, Russell. - The Invention of Fine Art PDFAlfonso Martinez TreviñoNo ratings yet

- Latino - A Art - Race and The Illusion of Equality - Art21 MagazineDocument5 pagesLatino - A Art - Race and The Illusion of Equality - Art21 MagazineMarcopó JuarezNo ratings yet

- Research To Action Essay-3Document6 pagesResearch To Action Essay-3api-709033375No ratings yet

- A Popular Brazilian MusicDocument17 pagesA Popular Brazilian MusicAurora PerezNo ratings yet

- Mário de Andrade, Mentor Modernism and Musical Aesthetics in Brazil, 1920-1945 - Hamilton-TyrrellDocument29 pagesMário de Andrade, Mentor Modernism and Musical Aesthetics in Brazil, 1920-1945 - Hamilton-TyrrellHenrique BorgesNo ratings yet

- Narratives EnglishDocument26 pagesNarratives EnglishNicolás Perilla ReyesNo ratings yet

- Pages From Stimson - Sholette - Collectivism - After - ModernismDocument49 pagesPages From Stimson - Sholette - Collectivism - After - Modernismmary mattinglyNo ratings yet

- Eisenman Gauguin Review ResponseDocument18 pagesEisenman Gauguin Review ResponseMariana AguirreNo ratings yet

- "Where Do We Go From Here?": Themes and Comments On The Historiography of Colonial Art in Latin AmericaDocument31 pages"Where Do We Go From Here?": Themes and Comments On The Historiography of Colonial Art in Latin AmericaIsabel GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Craven Abstract ExpressionismDocument24 pagesCraven Abstract ExpressionismNguyễn Thành Minh TâmNo ratings yet

- Jackson, Three Glad RacesDocument24 pagesJackson, Three Glad Racesjeronimo_pizarroNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Race in Brazilian Painting - Rafael CardosoDocument26 pagesThe Problem of Race in Brazilian Painting - Rafael CardosoJeanNo ratings yet

- Benezra - Media Art in ArgentinaDocument24 pagesBenezra - Media Art in ArgentinaGabriela SolNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Fantastic Mari Carmen Ramirez TrechosDocument2 pagesBeyond The Fantastic Mari Carmen Ramirez Trechosalvaro malagutiNo ratings yet

- Greeley Forum On Latin American WeissDocument12 pagesGreeley Forum On Latin American WeissJody TurnerNo ratings yet

- Cultural PolicyDocument24 pagesCultural PolicyJeniffer Fernandez HernandezNo ratings yet

- Propositions For A Decolonial Aesthetics and Five Days of Decolonial DaysDocument14 pagesPropositions For A Decolonial Aesthetics and Five Days of Decolonial DayspedrooyeNo ratings yet

- Folklore and The Politics of Region and Nation Building: Cuzco 1920-1950Document9 pagesFolklore and The Politics of Region and Nation Building: Cuzco 1920-1950Anonymous J5vpGuNo ratings yet

- Maricarmen Ramirez - Beyond The FantasticDocument10 pagesMaricarmen Ramirez - Beyond The FantasticMarina TorreNo ratings yet

- Forging A Popular Art HistoryDocument17 pagesForging A Popular Art HistoryGreta Manrique GandolfoNo ratings yet

- Select Works by Cesare SyjucoDocument19 pagesSelect Works by Cesare SyjucoDaniel DevelaNo ratings yet

- GUZY HATOUM KAMEL Globalisation and MuseumsDocument18 pagesGUZY HATOUM KAMEL Globalisation and Museumsvladimir_sibyllaNo ratings yet

- FENERICK - Tom Zé S Unsong and The Fate of The Tropicália MovimentDocument16 pagesFENERICK - Tom Zé S Unsong and The Fate of The Tropicália MovimentVitor MoraisNo ratings yet

- The Terms Postmodernism, Postcoloniality and Postfeminism in The American LiteratureDocument4 pagesThe Terms Postmodernism, Postcoloniality and Postfeminism in The American LiteratureResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Afterward, Librito, 3Document5 pagesAfterward, Librito, 3silverdy79No ratings yet

- Macari Uchicago 0330D 16635Document290 pagesMacari Uchicago 0330D 16635Hordago El SaltoNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Race in Brazilian Paintin PDFDocument24 pagesThe Problem of Race in Brazilian Paintin PDFGuilherme Rodrigues LeiteNo ratings yet

- To Defend the Revolution Is to Defend Culture: The Cultural Policy of the Cuban RevolutionFrom EverandTo Defend the Revolution Is to Defend Culture: The Cultural Policy of the Cuban RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Art Official HistoriesDocument6 pagesArt Official HistoriesUCLA_SPARCNo ratings yet

- Between Past and Present - Nationalist Tendencies in Bolivian Art, 1925-1950 PDFDocument32 pagesBetween Past and Present - Nationalist Tendencies in Bolivian Art, 1925-1950 PDFAna RuizNo ratings yet

- Comp Gilroy: Black Atlantic Modernity ConsciousnessDocument2 pagesComp Gilroy: Black Atlantic Modernity ConsciousnessDaveShawNo ratings yet

- Black Museum ModernDocument17 pagesBlack Museum ModernRaúl Moarquech Ferrera-BalanquetNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Community Art and ActivismDocument9 pagesAn Introduction To Community Art and ActivismAntonio ColladosNo ratings yet

- Art and Post ColonialDocument23 pagesArt and Post ColonialRaquel Torres ArzolaNo ratings yet

- Getty Research Journal,: The University of Chicago Press J. Paul Getty TrustDocument17 pagesGetty Research Journal,: The University of Chicago Press J. Paul Getty Trustjhon_lenon_30No ratings yet

- 07 g6b ReadingDocument5 pages07 g6b Readingapi-404789172No ratings yet

- English Afro-Diasporic Imaginaries PDFDocument6 pagesEnglish Afro-Diasporic Imaginaries PDFMichel Mingote Ferreira de AzaraNo ratings yet

- 31692-Texto Del Artículo-79326-1-10-20201201Document30 pages31692-Texto Del Artículo-79326-1-10-20201201Francisco OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Who Are The Folk in Folk Art Inside and Outside The Cultural ContextDocument7 pagesWho Are The Folk in Folk Art Inside and Outside The Cultural ContextNyannnNo ratings yet

- Cecilia Vicuña - Juliet LyndDocument21 pagesCecilia Vicuña - Juliet LyndCarola Vesely AvariaNo ratings yet

- Monica Juneja - Global Art History and The Burden of RepresentationDocument24 pagesMonica Juneja - Global Art History and The Burden of RepresentationEva MichielsNo ratings yet

- Adès, Dawn. Constructing Histories of Latin American Art, 2003 PDFDocument14 pagesAdès, Dawn. Constructing Histories of Latin American Art, 2003 PDFLetícia LimaNo ratings yet

- Migrants - Workers of Metaphors, Néstor García CancliniDocument15 pagesMigrants - Workers of Metaphors, Néstor García CancliniGerardo Montes de OcaNo ratings yet

- Mosquera - Latin American Art Ceases To Be Latin American ArtDocument3 pagesMosquera - Latin American Art Ceases To Be Latin American ArtMatthew MasonNo ratings yet

- White, Steven F. - Reinventing A Sacred Past in Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Poetry (An Introduction Five Afro-Brazilian Poets)Document39 pagesWhite, Steven F. - Reinventing A Sacred Past in Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Poetry (An Introduction Five Afro-Brazilian Poets)Marcus ViníciusNo ratings yet

- The Space In-Between Essays On Latin American Culture (Silviano Santiago)Document197 pagesThe Space In-Between Essays On Latin American Culture (Silviano Santiago)Alexandra ErdosNo ratings yet

- Dean & Leibsohn - Hybridity and Its Discontents Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish AmericaDocument33 pagesDean & Leibsohn - Hybridity and Its Discontents Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish AmericaJuan GomezNo ratings yet

- Cocktail Reception With Mitt Romney For Romney Victory Inc.Document2 pagesCocktail Reception With Mitt Romney For Romney Victory Inc.Sunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- The Future of Comparative Politics Is Its PastDocument13 pagesThe Future of Comparative Politics Is Its PasthugoNo ratings yet

- Consing V CADocument2 pagesConsing V CACarl AngeloNo ratings yet

- 26 Jusmag Philippines vs. NLRCDocument2 pages26 Jusmag Philippines vs. NLRCMavic Morales100% (3)

- Data Pegawai Untuk BalihoDocument26 pagesData Pegawai Untuk BalihoWa Ode SuriantiNo ratings yet

- Who Killed Democracy in Africa PDFDocument12 pagesWho Killed Democracy in Africa PDFAnonymous 7AMqr4No ratings yet

- This Week in Syria, DeeplyDocument2 pagesThis Week in Syria, DeeplyimpunitywatchNo ratings yet

- Posting Plan: Government of Pakistan Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) (Recruitment On Contract Basis)Document1 pagePosting Plan: Government of Pakistan Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) (Recruitment On Contract Basis)Suhyl AhmedNo ratings yet

- In Partial Fulfillment For The Requirement in Economics: Lira, Liezel ADocument4 pagesIn Partial Fulfillment For The Requirement in Economics: Lira, Liezel ARea Ann Autor LiraNo ratings yet

- List of PRI Members of Zilla Parishad (Zone Wise) of Kendrapara DistrictDocument3 pagesList of PRI Members of Zilla Parishad (Zone Wise) of Kendrapara DistrictGOutam DashNo ratings yet

- Vellama D/o Marie Muthu V Attorney-General (2012) SGHC 74Document9 pagesVellama D/o Marie Muthu V Attorney-General (2012) SGHC 74Gavin NgNo ratings yet

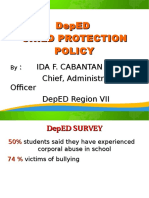

- Deped Child Protection PolicyDocument50 pagesDeped Child Protection Policymark montenegro100% (1)

- Elu Va-Elu Divre Elokim HayyimDocument17 pagesElu Va-Elu Divre Elokim HayyimarienimNo ratings yet

- Respondent - Sample MemorialDocument23 pagesRespondent - Sample MemorialAMITHAB SANKARNo ratings yet

- The National Bolshevist ManifestoDocument88 pagesThe National Bolshevist ManifestoSp At100% (4)

- Critical AnalysisDocument3 pagesCritical AnalysisGERRY CHEL LAURENTENo ratings yet

- City of Lapu-Lapu v. Philippine Economic Zone AuthorityDocument92 pagesCity of Lapu-Lapu v. Philippine Economic Zone Authorityblue_blue_blue_blue_blueNo ratings yet

- Analisis Kontrastif Nominalisasi Dalam Bahasa Inggris, Bahasa Indonesia, Dan Bahasa JawaDocument17 pagesAnalisis Kontrastif Nominalisasi Dalam Bahasa Inggris, Bahasa Indonesia, Dan Bahasa JawaZelda NameNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Concept of HeroDocument28 pagesLesson 2: Concept of HeroRhiza Paelmo IINo ratings yet

- History of The Peace Corps in MoroccoDocument5 pagesHistory of The Peace Corps in MoroccoTaoufik AfkinichNo ratings yet

- Bull Cat 4Document66 pagesBull Cat 4totochakraborty0% (1)

- Roman Involvement in Anatolia, 167-88 B.C. Author(s) : A. N. Sherwin-White Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 67 (1977), Pp. 62-75 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 03/10/2010 01:21Document15 pagesRoman Involvement in Anatolia, 167-88 B.C. Author(s) : A. N. Sherwin-White Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 67 (1977), Pp. 62-75 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 03/10/2010 01:21Daniel BogdanNo ratings yet

- Ghida NouriDocument1 pageGhida Nouriapi-210149307No ratings yet

- Leadership AnalysisDocument8 pagesLeadership Analysisapi-276879599No ratings yet

- 98Document1 page98Muhammad OmerNo ratings yet

"Tupy or Not Tupy?" Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

"Tupy or Not Tupy?" Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

Uploaded by

DavidOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

"Tupy or Not Tupy?" Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

"Tupy or Not Tupy?" Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

Uploaded by

DavidCopyright:

Available Formats

Studies in Art Education

A Journal of Issues and Research

ISSN: 0039-3541 (Print) 2325-8039 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/usae20

“Tupy or Not Tupy?” Examining Hybridity in

Contemporary Brazilian Art

Flavia M. C. Bastos

To cite this article: Flavia M. C. Bastos (2006) “Tupy or Not Tupy?” Examining

Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art, Studies in Art Education, 47:2, 102-117, DOI:

10.1080/00393541.2006.11650488

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2006.11650488

Published online: 18 Dec 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 53

View related articles

Citing articles: 3 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=usae20

Copyright 2006 by the Studies in Art Education

National An Education Association A Journal of Issues and Research

2006, 47(2). 102-117

"Tupy or not tupy?" Examining Hybridity

in Contemporary Brazilian Art

Flavia M. C. Bastos

UniversityafCincinnati

Correspondence Updating the 1920s notion of Anthropophagy developed to symbolize through

regarding this article cannibalistic ritual the process of cultural assimilation that influences art, this

should be addressed article examines issues of naming, describing, and representing contemporary

to the author at School Brazilian art. In the first part of the article, the work of four contemporary

of Art, Universityof Brazilian artists recently exhibited in the United States frames criticism to the

Cincinnati, P.O. Box common practice of labeling contemporary artworks according to national iden-

210016, Cincinnati,

tity. In the article's second section, Brazil's multifaceted cultural and artistic

OH 45221-0016.

context will be used to outline implications for art education and institutional

E-mail:

flavia.bastos@uc.edu practices more attuned to the transnational dimensions of art. In conclusion,

hybridity becomes a twofold framework. It describes, as Anthropophagy did

before, cultural layering, negotiations, and disputes. It also articulates a political

position more fitting to capture and interpret the art produced in our global age,

not only in Brazil.

"Tupy or not Tupy? That is the question" was the motto of a Brazilian

vanguard movement of the '20s. Reacting to European supremacy,

Anthropophagy [Antropofagia] took cannibalism as metaphor for the

process of cultural assimilation. The strong, often negative associations we

have about consuming human flesh intended to provide an image for the

symbolic (and sometimes actual) violence of cultural assimilation. Poet

Oswald de Andrade proposed in the movement's 1928 manifesto that to

break with cultural dependency on foreign models and create art that was

strongly Brazilian, it would be necessary to consume and transform

European influences, in the same way Tupinamba Indians would devour

and digest the enemy in order to take his strength (Canejo, 2004).

Therefore, to name this activist art of Brazil required avoiding the

denomination imposed by the colonizer in favor of one used by the

region's early habitants-Tupy, the name of one of the largest branches

of native languages in South America. An intentionally blatant paraphrase

of Hamlet, "Tupy or not Tupy?" encapsulated the cultural politics of

national art identity.

Issues associated with naming, describing, and representing the art of

different countries extend to present-day. On the one hand, art is in and

of a nation. Art is created within the constraints, influence, and support

of modern-era nation-states. Often art is exhibited and labeled according

to the place it was created or its creator's nationality. Nonetheless, under-

standing art frequently requires transcending the boundaries of a nation.

As the cannibalist approach underscores, at the core of making, exhibiting,

and interpreting art are the processes of transforming, appropriating, and

102 Studies in Art Education

Examining Hybridity in Contemporary BrazilianArt

exchanging ideas, perspectives, and cultural norms. In the global system

we experience today, these boundaries between nation and culture are

constantly being re-drawn, raising questions about taken-for-granted

practices of labeling works of art according to national origin. I invite

readers, especially art educators in the United States, to explore other,

perhaps more productive, ways to think about works of art from other

nations, particularly Brazil. This article inquires into the contemporary

condition of hybridity through the examination of four internationally

known contemporary artists recently exhibited in the United States,

Mestre Didi, Helio Oiricica, Anna Bella Geiger, and Adriana Varejao,

Brazilian art provides a case in point to investigate the transnational

dimensions of contemporary art and invites awareness of the political

implications of a hybrid position.

A Renewed Interest in Brazilian Art

In 1998, for the first time since its establishment, the Sao Paulo

Biennial was completely devoted to the truly Brazilian subject of

Anthropophagy. More recently in 2000, the large-scale exhibition Mostra

do Redescobrimento: Brasil 500 anos [The Rediscovery Show: Brazil 500

years], also held. in Sao Paulo, examined the multiplicity of Brazilian

artistic production from the indigenous to the contemporary. In 2002 the

Guggenheim Museum organized Brazil: Body and Soul, the largest and

most comprehensive exhibition of Brazilian art abroad. Partaking in the

spirit of the Rediscovery Show, the Guggenheim shows in New York and

Bilbao, Spain, presented prominent works created by Brazilian artists to

foster a more comprehensive understanding of the country and its art.

As a Brazilian art educator working in the United States, I have mixed

feelings about the usefulness of the label "Brazilian art." On the one hand,

it serves to draw attention, qualify, and perhaps justify, the unfamiliarity

of certain audiences with certain artists or forms. By and large, Brazil has

been excluded from the efforts of English-speaking America to correct

Eurocentric practices by directing scholarship and exhibits on many

aspects of Latin American art during the last two decades (Sullivan,

2001). Therefore, the label Brazilian art can be useful in focusing curato-

rial and interpretive practices on artists and visual culture manifestations

at risk of being excluded. On the other hand, Brazilian art can be a

misleading and perhaps problematic label. As Canclini (2004) observes,

the modern history of art has been practiced and written, to a great extent

as a history of art of nations.

Nations appeared to be a logical mode of organization of culture and

the arts. Even the vanguards that meant to distance themselves from

the socio-cultural codes are identified with certain countries, as if

these national profiles would help define their renovative projects:

thus, one talks about Italian Futurism, Russian Constructivism, and

the Mexican Muralist school. (p. 702)

Studies in Art Education 103

Flavia M. C. Bastos

The tendency to oversimplify the national and cultural identities of

works of art and visual culture obstructs understanding. As an interpretive

device, national affiliation or origin is a weak category. By stressing

national boundaries, the dynamics of cultural influences that are both

regional and transnational are often overlooked. In the case between

Brazil and the United States an emphasis on national borders has stressed

differences and promoted stereotypical views.

Brazil, A North American Gaze

For most people in the United States, Brazil evokes cliched notions

that have permeated Hollywood cinema since the early twentieth century.

Eccentric Brazilian characters were present in silent movies as early as

1925 (Augusto, 1982). However, in the 1930s, with the growth of capital

investment by the United States in Latin America and the beginning of

Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy, the deformation of Brazil, and for

that matter the rest of Latin America, in Hollywood movies began in

earnest. The 1933 musical Flying Down to Rio, with Ginger Rogers and

Fred Astaire, transformed the ciry in a world-renowned romantic vortex.

In Breakfast at TiffimJ's (1961), the heroine played by Audrey Hepburn,

falls in love with a man from Rio. Hitchcock gave the ciry a new spin,

depicting it as a site for Nazi spies in his 1946 film Notorious. But

certainly, the most prominent Brazilian Hollywood icon was Carmen

Miranda. Born in Portugal and raised in Brazil, Miranda served as the all-

purpose Latina bombshell in films throughout her career. Brazilian audi-

ences disliked Miranda's "Americanized" music, Caribbean outfits, and

tutti-frutti hat, considering them all emblematic of Yankee ignorance

about Latin America (Sullivan, 2001). Other stereotypes of Brazil exist in

the popular imagination, most of these deriving from television. Soccer is

seen as the national preoccupation, Carnival the national orgy, and

violence the norm. I know, along with many other Brazilians, that these

elements are to a greater or lesser degree present in Brazilian society. Yet,

due to the power of mass communication, they stand in the minds of

many as the defining characteristics of the country. Contrasting these

truisms with greater levels of understanding is a prerequisite to a more

profound engagement with the country's realities and art.

Another way of thinking about Brazil embraces its similarities with

the United States. The two vast continent-size New World countries are

comparable in both historical formation and ethnic diversity. Brazil

constitutes "a kind of southern twin whose strong affinities with the U.S.

have been obscured by ethnocentric assumptions and media stereotypes,"

(Starn, 2003, p. 203). After millennia of indigenous habitation and

culture, both Brazil and United States were discovered as part of Europe's

alleged search for a trade route to India. Their histories ran on parallel

tracks. Both countries' official histories start as European colonies, one of

Portugal, the other of Great Britain. In both countries, colonization led to

104 Studies in Art Education

Examining Hybridiry in Contemporary Brazilian Art

the occupation of vast territories and the dispossession of indigenous

peoples. In the United States, the occupiers were called pioneers; in Brazil,

they were called bandeirantes [explorers]. Subsequently, both countries

massively imported Africans to form the two largest slave societies of

modern times, up until slavery was abolished, with the Emancipation

Proclamation in 1863 in the United States and the "Golden Law" of

1888 in Brazil. Both countries received parallel waves of immigration

from all over the world, ultimately forming multicultural societies with

substantial indigenous, African, Italian, German, Japanese, Slavic, Arab,

and Jewish populations and influences (Almeida, 2003). This view of

Brazil and the United States can support a dialogue in which issues of

culture, identity, and representation as examined by artists of different

backgrounds can be discussed in a novel way.

A Personal Selection of Brazilian Contemporary Art

My selection of four artists seeks to exemplify significant themes in

Brazilian contemporary art and their transnational connections. For

example, an awareness of Black Atlantic cultural patterns and aesthetics is

embodied in Mestre Didi's Afro-Brazilian art; a negotiation between

international fine arts discourse and local references is at the core of

Oiticica's Tropicalism; and an attempt to represent the dual subaltern

status of Latin American women is common thread in Geiger's and

Varjeaos creations. These works are not emblematic of an essential

Brazilianess, but indicative of the diverse cultural influences shaping a

multifaceted contemporary art production.

Mestre Didi and the Art of Candornble

During the Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries,

hundreds of thousands of the Yoruba were exported to the New World to

work on plantations. Yoruba slaves preserved a significant part of their

cultural heritage, which markedly influenced the New World's culture in

the new religions that were created, including Candornble in Brazil. In

contemporary culture, these New World religions of Candornble,

Santeria, and Shang6, among others, create spaces of African culture not

diluted within the national cultures, although the practitioners are part of

their respective national entities and within these boundaries consider

themselves Brazilian, Cuban, Trinidadian, and so on (Lindsay, 1996).

According to Thompson (1984), the Yoruba have sophisticated artistic

sensibilities. One of the earliest dictionaries of the language, published in

1858, included the entry amewa, which means knower of beauty,

connoisseur. The Yoruba appreciate freshness and improvisation in the

arts, qualities that are evident in the vast body of artworks celebrating reli-

gion. This balance between tradition and renewal marks the artworks

created by Mestre Didi.

Mestre Didi is an 80-year-old Afro-Brazilian artist who is a devout

follower of the Orishas, Yoruba ancestral deities. His own religious

Studies in Art Education 105

Flavia M. C. Basros

authority formed the basis for his work in sculpture. Using diverse voices

to express himself and his art, Mestre Didi is a writer who narrates stories

and myths of origin, a priest, and a visual artist (Araujo, 200 l ). The

vigorous insertion of Mestre Didi into the international scene started in

the mid 1960s (Costa, 1997). His work was shown in African museums

(in Accra, Dakar, Lagos) as well as in European, Latin American, and

New York venues.

Figure 1. Mestre Didi, abd

Obadena (King ofthe

Sentinels). Bundled palm

ribs, leather, beads, and

cowrie shells,

68 x 24 x 24 em. Collection

of the artist. Used with

permission of the artist.

106 Studies in Art Education

Examining Hybridiry in Contemporary Brazilian Art

Mestre Didi's works begin wirh a systematic unit: a bunch of palm-tree

ribs bound together by strips of leather. His sculptures range from about

2 to 10 feet and are adorned with leather, glass beads, cowrie shells, and

fiber skirts of different colors. His materials are evocative of straight and

looped Yoruba ritual brooms, shashara and ibiri, sacred implements for

purifying spaces, places, and persons, and assuring of well being and good

fortune. According to dos Santos (2001), his works convey both a sense

of tradition and renewal. Starting with a shashara, each sculpture repre-

sents a variation, fugue, an ode dedicated to the perpetuation of tradi-

tional form. During most of his life he has made ritual objects; his

aesthetic production, inspired by traditional matrixes, has led to new

symbolizing interpretations, offering innovative insight into tradition.

Didi's work is part of the important tradition of Afro-Brazilian ritual

and aesthetics. The role played by Africa in the formation of the Brazilian

collective consciousness cannot be overstated. From the earliest contacts

between the New and the Old Worlds, cultural patterns emerged in

Brazil that parallel those of many of the African civilizations from which

the slaves were taken. Food, language, visual art, music, dance, and reli-

gion are all elements of Brazilian culture that have permeated and have

been forged in these contacts with Africa. The aesthetic experience of

African-Brazilian religion is part of a system of references in which each

object has a function and an objective with regard to the sacred (Montes,

2001). The sacred is the source of an entire production of art that has

remained clandestine, and the origin of an aesthetic that is not recognized

by official history but which nevertheless presents unique Afro-Brazilian

characteristics. Mestre Didi's works reflect this vibrant tradition brought

to Brazil by the African Diaspora. The assimilation of African-Brazilian

art such as Didi's in the contemporary international art milieu can be

understood as a layered Anthropophagic phenomenon. Yoruba's roots

form the core layer that is surrounded by New World's oppression, and

finally festooned with mainstream art world's recognition. These power

struggles shape not only the art itself, but more importantly, how it is

absorbed into our experience.

Music, Art, and Revolution: Helio Oiticica and Tropicalism

An inclusive art movement of the late 1960s, T ropicalism began with

pop music, as a reaction to the international popularity and lax political

message of bossa nova, Brazilian cool jazz. Initiated by two musicians,

Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, the rebellious art movement voiced

strong opposition and resistance to the military dictatorship that started

in 1964. In Veloso's words, Tropicalism's purpose was

... to sort out the tension between Brazil-the parallel universe and

Brazil the country peripheral to the American Empire. A country,

which at the time was ruled by a military dictatorship, believed to

have been fostered by anticommunist maneuvers of the American

Studies in Art Education 107

Flavia M. C. Bastos

Empire Central Intelligence Agency. [... J Tropicalism wanted to

project itself as the triumph over two notions: one, that the version

of the Western enterprise offered by American pop and mass culture

was potentially liberating and two, the horrifying humiliation

represented by capitulation to the narrow interests of dominant

groups, whether at home or internationally. (2003, pp. 6-7)

Helie Oiticica (1937-1980) has been credited with developing the

visual art component to this politically charged movement. The name,

Tropicalism, derives from the made up word Tropictilia, a 1967 installation.

Already an established artist at the time, Oiticica's Tropicdlia revisited

Anthropophagy's ideas to inquire into national identiy and representation.

Oiticica attempted to impose an obviously Brazilian image upon the

current context of the avant-garde and national art manifestations in

general.

Tropicdlia installation. The work consists of two structures that can be

penetrated by the spectator, called penetrdveis [penerrables]. According to

Canejo's description (2004), the larger of the two works, PN3, is a small

labyrinth that combines international modernist concepts with the innov-

ative architecture of the favelas (squatter housing on the hillside of Rio de

Janeiro). This combination of canonical art and vernacular style questions

set values in raising the structural design of the favelas to the level of high

art. Oiticica was highly conscious of the latest contemporary perfor-

mances, installations, and happenings and Tropictilia must also be seen as

his attempt to co-opt these forms. The other penetrable in Tropicdlia,

PN2, is an open-roofed "booth" in which the spectator is enclosed with

sensory objects: fragrant herbs and soil. The two structures in Tropictilia

are to be seen and experienced together. They are multi-sensory installa-

tions surrounded by stereo typically emblematic Brazilian elements. This

backyard is made up of picturesque sandy paths, small rock beds,

common tropical plants, and, originally, live macaws. From the outside,

the visitor hears the sounds of birds mixed with muffled voices from

inside the labyrinth. Walking barefoot across the sand, the spectator

enters the small corridor of the labyrinth. As s/he ventures further inside,

the hall darkens; the material overhead becomes solid and the slits of light

between the exterior wallboards grow smaller and finally close up. Thus,

once in the interior, space diminishes and there is a gradual loss of light

and air. The corridors are narrow and there is no out at the other end.

Rounding the last corner, the participant sees a fluctuating glow and hears

a low sound, although not yet discerning the source. Then, suddenly s/he

encounters a flickering television set. Oiticica has described the internal

spiral of the structure as a "shell." At its center, the participant is capti-

vated by a constant bombardment of "global" images. According to

Helie's 1968 diary entry (as cited in the 1996 Helio Oiticica exhibit cata-

108 Studies in Art Education

Examining Hybridiry in Contemporary Brazilian Art

logue), "it is the image that devours the spectator. .. [this] is in my

opinion the most anthropophagic work in Brazilian art" (p.12S).

Oiricica proposes to cannibalize features of international contemporary

and modernistic artistic styles. At the same time, the work intends to

absorb the power of the colonizers in reproducing the exotic Brazil of

their imagination in the backyard of his environmental work. Surpassing

original Antbropophagic tenets proposed by Oswald de Andrade, Oiricica

was deconsrrucring the myth of a Brazilian tropical paradise through a

contrast between the isolated calm exterior fashioned with typical

elements of the tropics (birds, colorful fabric, white sand, erc.) and the

interior assault of broadcast television images. This combination of

symbolic situations (interior vs, exterior) and cliched objects (national vs.

international) is effective and powerful. This way of alluding indirectly,

figure 2. Helie Oiricica. Tropicdlia pmetrable! PN2 and PN3, 1967, installed at State University

of Rio de Janeiro, 1990. Used with permission of the artist.

Studies in Art Education 109

Flavia M. C. Bastos

rather than explicitly confronting issues, becomes the trademark of

Tropicalisr artists, including musicians, playwrights, film directors, and

poets (Canejo, 2004). Additionally, this subtlety of expression was a

necessary strategy to sidestep the increasing censorship to the arts imposed

by the military dictatorship at the time.

Counter-narratives of Conquest: Two Contemporary Women Artists

Unveiling the dynamics of conquest that have marked Brazilian history

from the arrival of the Portuguese in 1500, these two women artists

working today in Brazil explore continuities and discontinuities in time

and space. The conceptual maps of Anna Bella Geiger and the post-

modern history paintings of Adriana Varejao illustrate the dualities of

center/periphery, hegemony/subordination, globaillocal as they apply to

Latin America's relationship to European colonialism and dominance by

the United States (Sterling, 2001).

Anna Bella Geiger's maps incorporate the constituent elements cartog-

raphers have used to represent the world since the voyages of discovery. In

this reinvented cartography she does nor offer the rypical coherent vision

of global order. Instead, Geiger's mapping strategies have emphasized

geographic fragmentation, elision, and discontinuity, played out in a

Figure 3. Anna Bella Geiger. Orbis Descriptio (Description o/the WorldJ.

Courtesy of Tepper Takayama Fine Arts.

110 Studies in Art Education

Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

variety of media. She fills shallow file drawers with elegantly reconfigured

maps of the Southern and Northern Hemispheres. Whether stamped out

in encaustic or traced in precious and base metals, her waxen seas are

fluid, the continents drift, meridians reposition themselves, and their exis-

tence seems poised to continue outside the box. Since the early 1970s,

Geiger has explored representation, redefining maps to allude to her own

interrogations about the territorial construction of Brazil's new global

sphere.

As many artists of her generation, Geiger explored the function and

nature of the work of art. However, in the politically and culturally

repressed Brazil of the early 1970s (post-Tropicalism), Geiger found

herself torn between criticizing the concept of "Brazilianess" that had

been co-opted as part of the authoritarian ideology of the government

and having her work attacked as ideologically traditional. Fearing her

work would simply illustrate this tension, Geiger opted for using parody,

turning her work into derritorialized and dissonant fragments (Cocchiarale,

2001). These disturbing orbs and charts also speak of the Brazilian artist

cultural exile as s/he occupies a secondary position in an international and

hierarchical art system.

Adriana Varejao's contemporary baroque history paintings created in

the style of Portugal's famed azulejos (blue-and-white decorative tiles)

deftly invert the official history of Brazil's invasion by appropriating a

language favored by the Portuguese conquerors. She recontextualizes

cannibal scenes lifted from early explorers' travel narratives, depicting

relics and votive offerings, and incorporating images of dismembered

organs on her chosen canvas of Portuguese tiles. Visually representing

Anthropophagy's notion of absorption with the Other, Varejao's works

depict parallels between the alleged cannibal practices of Brazil's natives

and the Eucharistic ritual as a symbolic consumption of the body of

Christ (Carvajal, 2001).

Evoking a sense of passage, a journey among divergent images,

cultures, times and spaces, Varejao appropriates and re-maps a vast body

of images, forms, and ideas disseminated by the Europeans during their

colonization of Brazil. Commenting on this history of violence and domi-

nation, resistance, displacements, and syncretisms, she says,

I am interested in verifying in my work dialectical processes of

power and persuasion. I subvert those processes and try to gain

control over them in order to become an agent of history rather

than remaining an anonymous, passive spectator. I not only

appropriate historic images-I also attempt to bring back to life

the processes, which created them and use them to construct new

versions. (cited in Carvajal, 2001, p. 116)

Varejao makes us aware of the continuous reformulation of history

and our role in it. A common thread in these two artists' works is, on the

Studies in Art Education III

Flavia M. C. Bastes

Figure 4. Adriana Varejao. Proposalfor a Catechesis: Part I Diptych: D~ath and Dismemberment;

1993. Oil on canvas, 53 1/ 8 x 94 1/ 2 in. Used with permission of the artist.

one hand, unveiling the processes of the construction of Brazil as an

entity with a geographic, historical, and cultural existence; and on the

other, representing transnational relationships that inform Brazil's position

in past and present history. Highly political, their works make a powerful

commentary about Brazil's subjugated relat ionship with Europe and ,

more recently, the United States . Adriana Varejao and Anna Bella Geiger ,

like Helie Oiticica before them, give continuity to the Antbropopbagic

preoccupation of examining Brazilian cultural and artistic identity,

providing counter-narratives of identity that encompass history, domina-

tion, and otherness.

Beyond Essentialist Conceptions of Brazilian Art

Museum and cultural institutions that have recently exhibited Brazilian

art, such as the Guggenheim, the Walker Art Center, and the National

Museum of Women in the Arts, have revisited traditional practices,

Echoing some of the same concerns voiced in this article, these institutions

strived to address and minimize rhe problems of representing geograph -

ical-political enti ties such as nation-stares through selected works of an.

In practice, however , these efforts to meet the demands of a global agenda

112 Studie« in Art Education

Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

and the need to educate English-speaking audiences about largely unfa-

miliar artworks, resulted in Brazilian art exhibits that sought to capture

"the essential nature of an extraordinary country" (Krens, 2001, p. xiii).

I am the first to acknowledge that Brazilian art is a recognizable cate-

gory. Nonetheless, as Schultz, Sims, Rotilie, Atkinson, and Walters (2003)

observe, while descriptors such as Brazilian art or Japanese art may give

audiences some familiar information, their usefulness is questionable. A

considerable risk is to make the meaning behind one artist's work speak

for an entire culture. Additionally, increasingly nomadic lifestyles make

nationality an incomplete indicator of artists' cultural background.

Clearly, it is relevant to know if the person making the work has lived or

studied other places or is connected to other cultures. However, as we

become aware of the limitations of understanding of contemporary works

of art though nationality labels, we are faced with a paradox. On the one

hand, the existence of nation-states cannot be denied, along with the

intellectual habit of expecting to gain insights into artworks from their

geographical provenance. On the other hand, postmodern perspectives

have sensitized us to multi-layered and complex understandings of culture

that cannot be contained by national frontiers. According to Canclini

(2004), the current interest in investigating artistic and cultural identities

is shaped by a discordant dialogue between fundamentalism and global-

ization. The pretension of constructing national cultures and representing

them by specific iconographies is challenged in our time by the processes

of an economic and symbolic transnationalization. Herkenhoff (2003)

reminds us that the mechanisms of global articulation are all-encom-

passing, including immigration, drugs, corporations, terrorism, commu-

nications, weapons smuggling, capital, omnipotent governments, war,

weather, human-made global warming, natural catastrophes, disease, sex,

AIDS, tourism, and art. The world in which we live today is marked by

the dual presence of abject misery and unprecedented abundance, both

outcomes of the global economic order (Sen, 2001). To understand the

art produced in this complex, layered, and many times incongruent

world, it is important to operate outside conventional labels and notions

of art history, making room for what Becker (2002) calls "unruly forms of

intelligence." The modern affair of looking at art and artifacts from other

cultures and other countries must evolve in response to postmodern

concerns and world order. The final section of this article will propose an

alternate way to access the art recently produced in Brazil.

Considering Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

International interest in Brazilian art invites robust interpretive frame-

works that break usual cliches (Farias, 1997). Such frameworks can enable

viewers and institutions to engage with these works in a novel way.

Particularly in the United States, this renewed interest in Brazilian art can

open up a conversation about complementary perspectives that take into

Studies in Art Education 113

Flavia M. C. Bastos

account socio-cultural and political issues. On the one hand, these issues

influence artworks' form and content; and, on the other hand, they struc-

ture the experience of viewing such works in the United States. More

specifically, the American hegemonic relationship with Brazil and other

Latin American countries, in a similar vein to the earlier European domi-

nation of the New World, is an important theme in Brazilian art.

Therefore encounters with these works must inquire into the power rela-

tions that forged the two countries and informed their current and past

relationships. Art educators interested in cultural understanding (Chanda,

1995; Krug, 2003; Mason, 2004; Stuhr, 2003; Zimmerman, 1990)

propose a shift from binary relations of difference that stereotype what we

think of as culture. Gooding-Brown (2000) suggests a disruptive model of

interpretation that highlights the social construction of interpretation,

self, and difference. Inspired by border studies, Garber (I995) discusses

the development of a border consciousness, which implies the knowledge

of at least two sets of reference codes operating simultaneously. The

ability to simultaneously negotiate two codes-as seen in Mestre Didi's

coalescing of Brazilian experiences and Yoruba traditions, Oiticica's juxta-

position of fine art and vernacular architecture, and Varejao and Geiger's

pulsing internal and external perspectives-is essential to grasp contem-

porary works. The four Brazilian artists presented in this article beg for an

unruly analysis that requires a rupture from conventional ways of engaging

with art from other countries.

Alternative approaches such as these have the potential to concurrently

denounce the perils of nationalism and offer a framework to understand

contemporary hybridity. For Canclini (I995) hybridity is the ongoing

condition of all cultures, which contain no zones of purity, because they

undergo continuing processes of transculturation (two-way borrowing

and lending between cultures). In other words, hybridiry is a character-

istic of contemporary times and art, underlining the existence of multiple

and simultaneous influences and associations. Ir acknowledges that

neither the artist's nor the work's identity can be reduced to a simplified

notion of nation. Enwezor, curator of the most recent Documenta,

suggested contemporary art practices should model the "hybridization of

the world where roots are replaced by routes taking people on unsure

travels into the future" (Belting, 2001, p. 337).

A dynamic concept, hybridiry refers to the coexisting influences nego-

tiated in and through works of art. It focuses less on the mixed cultural or

ethnic codes that may have been articulated, then on the power dynamics

that produced these various references. Hybridity encompasses a political

dimension, rendering cultural borrowing and landing visible as well as the

frequently inequitable social conditions in which it occurs, such as colo-

nization, war, or imperialism. Pointedly, hybridity can refer us to our

shared humanity, without simplifying or homogenizing cultures or

nations. Furthermore, it can become a valuable tool to delve deeply into

114 Studies in Art Education

Examining Hybridity in Contemporary Brazilian Art

the complexities of cultural negotiation and creativity that surpass modern

conceptions of nation.

Tupy or not Tupy? The Conclusion May Be Both

By criticizing domination through parody-literally and metaphori-

cally depicting cannibalism as the ultimate act of absorption with the

orher, the Anthropophagic movement has inspired Brazilian artists to

politicize their practice. As a result, this critical genre of art sought to

denounce the historical, political, cultural, and economic domination;

celebrate the mixed ethnic and cultural heritages that existed in Brazil as a

result of that; and promote a twofold understanding of Brazilian art and

culture as, (1) a counter-narrative of oppression, and (2) the articulation

of a hybrid position. Contemporary Brazilian artists such as Didi, Geiger,

Oiticica, and Varejao have drawn upon a mix of cultural influences to

articulate a progressive political position. We can learn by engaging with

their art that hybridity is not only a condition of contemporary artworks,

but also an empowering position from which to speak.

Our engagement with these works can give priority to concerns about

labeling their characteristics "Brazilian" or "Tupy" or "Latin." This

labeling practice only invites disembodied expertise and reinforces the

status quo. Alternatively, a transformative approach inquires into social

construction of the artwork. Such an encounter has the potential to

engender an act of cultural translation that according to Bhabha (1994),

"desacralizes the transparent assumptions of cultural supremacy" (p. 228).

Therefore, encounters with contemporary artworks demand debunking

monolithic views of nation, culture, and art, in favor of a more nuanced

and layered examination of self, other, and context. Such encounters also

require embracing the notion of hybridity as a powerful and more appro-

priate analytical framework to reflect upon and interpret art created

within the complex cultural negotiations of the global system.

It seems to me, hybridity can become a framework with the potential to

transcend traditional nation-state boundaries, and a more fitting approach

to inquiry into contemporary artworks. Hybridity can be seen as a shared

condition of these four Brazilian artists, and conceivably of many other

contemporary artists who seek to make statements about the transitional

cultural spaces they occupy and their journeys in getting there. Building

on the post-colonial notion of contact zone, or Garber's concept of

borderland, both spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with one

another, hybridity has the potential to replace imperialist understandings

of nation with an organic articulation of cultural identity. Men and

women of our global and multicultural age, among them artists, do not

necessarily find their place within any particular culture, but in these

many in-between and transitional spaces they occupy. Embracing a

hybrid view of art and culture is a challenge that art educators and

cultural institutions begin to recognize as essential in an age when the

articulation of difference strives to replace hegemonic art practices.

Studies in Art Education 115

Flavia M. C. Bastos

References

Almeida, A. F. J. (2003). Unveiling the mirror: Afro-Brazilian identity and the emergence of a

community school movement. Comparative Education Review, 47(1),41-63.

Araujo, E. (2001). Exhibiting Afro-Brazilian art. In Brazil, body, and soul (pp. 312-325). New

York: Guggenheim Museum Publications.

Augusto, S. (1982). Hollywood looks at Brazil: From Carmen Miranda to Moonraker. In R.

Johnson & R. Starn (Eds.), Brazilian cinema (pp. 351-61). New York: Columbia University

Press.

Becker, C. (2002). A conversation with Okwui Enwezor, Art[ournal; 61, 8-27.

Belting, H. (2001). Hybrid art? A look behind the global scenes. janus, 9, 41-46.

Bhabha, H. (1994). The location ofculture. New York: Routledge.

Canclini, N. (2004). Remaking passports: Visual thought in the debate of multiculturalism.

In D. Preziosi & C. Farago (Eds.), Grasping the world: The idea ofthe museum (pp. 699-707).

Hants, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Canclini, N. G. (1995). Hybrid cultures: Strategies[or entering and leaving modernity. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

Canejo, C. (2004). The resurgence of Anthropophagy: Tropicalia, tropicalism, and Helio Oirica,

Third Text, 18(1),61-68.

Carvajal, R. (2001). Adriana Varejao: Travel chronicles. In Virgin territory: Women. gender and

history in contemporary Brazilian art (pp. 116-119). Washington, DC: Narional Museum of

Women in the Arts.

Chanda, J. (1995). The possibiliries and limitations of cross-cultural understanding. The journal

ofAesthetics Education, 29, 34-7.

Cocchiarale, F. (2001). Anna Bella Geiger: A sense of constellation. In Virgin territory: Women.

gender and history in contemporary Brazilian art (pp. 62-65). Washingron, DC: National

Museum of Women in the Arts.

Costa, E. (1997, July). Mestre Didi at Prova do Artista. Art in America, 85, 101.

dos Santos, J. E. (2001). Afro-Brazilian tradition and contemporaneity. In Brazil. body, and soul

(pp. 326-333). New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications.

Farias, A. (1997). Bresil: Petit manuel d'insrructions [Brazil: A mini-manual]. Art Press, 221,

34-39.

Garber, E. (1995). Teaching art in the context of culture: A srudy in the borderlands. Studies in

Art Education, 36(4), 218-232.

Gooding-Brown, J. (2000). Conversations about art: A disruptive model of interpretation. Studies

in Art Education, 42(1),36-50.

Helio Oiticica Exibition Catalogue. (1996). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Secreraria Municipal de Cultura,

Herkenhoff, P. (2003). Learning and dislearning ro be global: Questions at 44053' N, 93013' W

and 220 54' 24" S, 430 10' 21" W. In How latitudes becomefOrms: Art in a global age (pp. 124-

129). Minneapolis: Walker Arts Center.

Krens, T. (200 I). Foreword. In Brazil, body. and soul (pp. x-xiii). New York: Guggenheim

Museum Publications.

Krug, D. (2003). Symbolic culture and art education. Art Education. 56\.2), 13-19.

Lindsay, A. (Ed.) (1996). Santeria aesthetics in contemporary Latin American art. Washingron, DC

and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

116 Studies in Art Education

Examining Hybridiry in Contemporary Brazilian An

Mason, R. (2004). Culrural projection and racial politics in art education. Visual Arts Research,

3!X2), 38-54.

Montes, M. L. (2001). African cosmologies in Brazilian culture and society. In Brazil, body, and

soul (pp.334-343). New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications.

Schultz, S., Sims, K. M., Rotilie, S., Atkinson, C, & Walters, M. (2003). Interactions/intersec-

tions: Cultural globalism and educational practice. In How latitudes become[orms. Art in a

global age (pp. 76-87). Minneapolis: Walker Arts Center.

Sen, A. (2001, July 17). Ten theses on globalization. Los Angeles Times.

Starn, R. (2003). Brazilian cinema: Reflections on race and representation. In S. Hart & R. Young

(Eds.), Contemporary Latin American cultural studies (pp. 203-214). London: Arnold.

Sterling, S. F. (2001). Virgin territory. In Virgin territory: Women, gender and history in contempo-

rary Brazilian art (pp. 20-33). Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Stuhr, P. (2003). A rake on why social and cultural content is often excluded from art education

-and why it should not be. Studies in Art Education, 44(4), 301-314.

Sullivan, E. (2001). Brazil: body and soul. In Brazil, body, and soul (pp, 2-33). New York:

Guggenheim Museum Publications.

Thompson, R. F. (1984). Flash ofthe spirit: African and Afro-American art and philosophy. New

York: Vintage Books.

Veloso, C. (2003). Tropical truth: A story ofmusic and revolution in Brazil New York: Da Capo

Press.

Zimmerman, E. (1990, December). Teaching art from a global perspective. Bloomington, IN:

ERIC Art Design/ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education,

no. EDO-SO-90-10.

Studies in Art Education 117

You might also like

- Rizal, Jose. 1963. Rizal Correspondence With Fellow ReformistsDocument401 pagesRizal, Jose. 1963. Rizal Correspondence With Fellow Reformistsordinaireangelo100% (1)

- Case Analysis of Administrative Law (Himmat Lal Shah V Commissioner of PoliceDocument18 pagesCase Analysis of Administrative Law (Himmat Lal Shah V Commissioner of PoliceShubham PhophaliaNo ratings yet

- David Craven - Abstract and Third WorldDocument24 pagesDavid Craven - Abstract and Third WorldBrigitta Isabella100% (1)

- 2022 - America Indigena And...Document29 pages2022 - America Indigena And...dorotinskyNo ratings yet

- Trump V House Select NARA DeclarationDocument57 pagesTrump V House Select NARA DeclarationFile 411No ratings yet

- Capitalism and Accounting in The Dutch East-India Company 1602-16Document538 pagesCapitalism and Accounting in The Dutch East-India Company 1602-16Saarvin சர்வின் 李在山 سرفينNo ratings yet

- Gilbert, McKinney, Roberson IndictmentDocument34 pagesGilbert, McKinney, Roberson IndictmentIvana HrynkiwNo ratings yet

- Cultural Cannibalism and Tropicalia An Alternative Modernism in Brazil - EditedDocument20 pagesCultural Cannibalism and Tropicalia An Alternative Modernism in Brazil - EditedDalvin Jr.No ratings yet

- Antropofagia Cultural CannibalismDocument8 pagesAntropofagia Cultural CannibalismLuisa MarinhoNo ratings yet

- Abaporu TropicalistaDocument18 pagesAbaporu Tropicalistalis gomesNo ratings yet

- Is It Possible To Decolonize The Concept of Cultural Antropophagy. MARIA INIGO CLAVODocument5 pagesIs It Possible To Decolonize The Concept of Cultural Antropophagy. MARIA INIGO CLAVOTatiane CovaNo ratings yet

- Antropofagia Cultural Cannibalism PDFDocument8 pagesAntropofagia Cultural Cannibalism PDFSara ArosioNo ratings yet

- Mosquera, Gerardo - Takeoff - Arte Desde América Latina - y Otros Pulsos GlobalesDocument5 pagesMosquera, Gerardo - Takeoff - Arte Desde América Latina - y Otros Pulsos GlobalesPaola PeñaNo ratings yet

- Brown University, 5.3 Modern Art WeekDocument9 pagesBrown University, 5.3 Modern Art Weekjeronimo_pizarroNo ratings yet

- Ab psr-2Document7 pagesAb psr-2api-709033375No ratings yet

- 09 GarciaCanclini MulticulturalismDocument5 pages09 GarciaCanclini MulticulturalismStergios SourlopoulosNo ratings yet

- 05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Document25 pages05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Anamaria Garzon MantillaNo ratings yet

- Cangoma Calling Spirits and Rhythms of FDocument27 pagesCangoma Calling Spirits and Rhythms of Fmyahaya692No ratings yet

- Leigh Sharman, Russell. - The Invention of Fine Art PDFDocument24 pagesLeigh Sharman, Russell. - The Invention of Fine Art PDFAlfonso Martinez TreviñoNo ratings yet

- Latino - A Art - Race and The Illusion of Equality - Art21 MagazineDocument5 pagesLatino - A Art - Race and The Illusion of Equality - Art21 MagazineMarcopó JuarezNo ratings yet

- Research To Action Essay-3Document6 pagesResearch To Action Essay-3api-709033375No ratings yet

- A Popular Brazilian MusicDocument17 pagesA Popular Brazilian MusicAurora PerezNo ratings yet

- Mário de Andrade, Mentor Modernism and Musical Aesthetics in Brazil, 1920-1945 - Hamilton-TyrrellDocument29 pagesMário de Andrade, Mentor Modernism and Musical Aesthetics in Brazil, 1920-1945 - Hamilton-TyrrellHenrique BorgesNo ratings yet

- Narratives EnglishDocument26 pagesNarratives EnglishNicolás Perilla ReyesNo ratings yet

- Pages From Stimson - Sholette - Collectivism - After - ModernismDocument49 pagesPages From Stimson - Sholette - Collectivism - After - Modernismmary mattinglyNo ratings yet

- Eisenman Gauguin Review ResponseDocument18 pagesEisenman Gauguin Review ResponseMariana AguirreNo ratings yet

- "Where Do We Go From Here?": Themes and Comments On The Historiography of Colonial Art in Latin AmericaDocument31 pages"Where Do We Go From Here?": Themes and Comments On The Historiography of Colonial Art in Latin AmericaIsabel GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Craven Abstract ExpressionismDocument24 pagesCraven Abstract ExpressionismNguyễn Thành Minh TâmNo ratings yet

- Jackson, Three Glad RacesDocument24 pagesJackson, Three Glad Racesjeronimo_pizarroNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Race in Brazilian Painting - Rafael CardosoDocument26 pagesThe Problem of Race in Brazilian Painting - Rafael CardosoJeanNo ratings yet

- Benezra - Media Art in ArgentinaDocument24 pagesBenezra - Media Art in ArgentinaGabriela SolNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Fantastic Mari Carmen Ramirez TrechosDocument2 pagesBeyond The Fantastic Mari Carmen Ramirez Trechosalvaro malagutiNo ratings yet

- Greeley Forum On Latin American WeissDocument12 pagesGreeley Forum On Latin American WeissJody TurnerNo ratings yet

- Cultural PolicyDocument24 pagesCultural PolicyJeniffer Fernandez HernandezNo ratings yet

- Propositions For A Decolonial Aesthetics and Five Days of Decolonial DaysDocument14 pagesPropositions For A Decolonial Aesthetics and Five Days of Decolonial DayspedrooyeNo ratings yet

- Folklore and The Politics of Region and Nation Building: Cuzco 1920-1950Document9 pagesFolklore and The Politics of Region and Nation Building: Cuzco 1920-1950Anonymous J5vpGuNo ratings yet

- Maricarmen Ramirez - Beyond The FantasticDocument10 pagesMaricarmen Ramirez - Beyond The FantasticMarina TorreNo ratings yet

- Forging A Popular Art HistoryDocument17 pagesForging A Popular Art HistoryGreta Manrique GandolfoNo ratings yet

- Select Works by Cesare SyjucoDocument19 pagesSelect Works by Cesare SyjucoDaniel DevelaNo ratings yet

- GUZY HATOUM KAMEL Globalisation and MuseumsDocument18 pagesGUZY HATOUM KAMEL Globalisation and Museumsvladimir_sibyllaNo ratings yet

- FENERICK - Tom Zé S Unsong and The Fate of The Tropicália MovimentDocument16 pagesFENERICK - Tom Zé S Unsong and The Fate of The Tropicália MovimentVitor MoraisNo ratings yet

- The Terms Postmodernism, Postcoloniality and Postfeminism in The American LiteratureDocument4 pagesThe Terms Postmodernism, Postcoloniality and Postfeminism in The American LiteratureResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Afterward, Librito, 3Document5 pagesAfterward, Librito, 3silverdy79No ratings yet

- Macari Uchicago 0330D 16635Document290 pagesMacari Uchicago 0330D 16635Hordago El SaltoNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Race in Brazilian Paintin PDFDocument24 pagesThe Problem of Race in Brazilian Paintin PDFGuilherme Rodrigues LeiteNo ratings yet

- To Defend the Revolution Is to Defend Culture: The Cultural Policy of the Cuban RevolutionFrom EverandTo Defend the Revolution Is to Defend Culture: The Cultural Policy of the Cuban RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Art Official HistoriesDocument6 pagesArt Official HistoriesUCLA_SPARCNo ratings yet

- Between Past and Present - Nationalist Tendencies in Bolivian Art, 1925-1950 PDFDocument32 pagesBetween Past and Present - Nationalist Tendencies in Bolivian Art, 1925-1950 PDFAna RuizNo ratings yet

- Comp Gilroy: Black Atlantic Modernity ConsciousnessDocument2 pagesComp Gilroy: Black Atlantic Modernity ConsciousnessDaveShawNo ratings yet

- Black Museum ModernDocument17 pagesBlack Museum ModernRaúl Moarquech Ferrera-BalanquetNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Community Art and ActivismDocument9 pagesAn Introduction To Community Art and ActivismAntonio ColladosNo ratings yet

- Art and Post ColonialDocument23 pagesArt and Post ColonialRaquel Torres ArzolaNo ratings yet

- Getty Research Journal,: The University of Chicago Press J. Paul Getty TrustDocument17 pagesGetty Research Journal,: The University of Chicago Press J. Paul Getty Trustjhon_lenon_30No ratings yet

- 07 g6b ReadingDocument5 pages07 g6b Readingapi-404789172No ratings yet

- English Afro-Diasporic Imaginaries PDFDocument6 pagesEnglish Afro-Diasporic Imaginaries PDFMichel Mingote Ferreira de AzaraNo ratings yet

- 31692-Texto Del Artículo-79326-1-10-20201201Document30 pages31692-Texto Del Artículo-79326-1-10-20201201Francisco OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Who Are The Folk in Folk Art Inside and Outside The Cultural ContextDocument7 pagesWho Are The Folk in Folk Art Inside and Outside The Cultural ContextNyannnNo ratings yet

- Cecilia Vicuña - Juliet LyndDocument21 pagesCecilia Vicuña - Juliet LyndCarola Vesely AvariaNo ratings yet

- Monica Juneja - Global Art History and The Burden of RepresentationDocument24 pagesMonica Juneja - Global Art History and The Burden of RepresentationEva MichielsNo ratings yet

- Adès, Dawn. Constructing Histories of Latin American Art, 2003 PDFDocument14 pagesAdès, Dawn. Constructing Histories of Latin American Art, 2003 PDFLetícia LimaNo ratings yet

- Migrants - Workers of Metaphors, Néstor García CancliniDocument15 pagesMigrants - Workers of Metaphors, Néstor García CancliniGerardo Montes de OcaNo ratings yet

- Mosquera - Latin American Art Ceases To Be Latin American ArtDocument3 pagesMosquera - Latin American Art Ceases To Be Latin American ArtMatthew MasonNo ratings yet

- White, Steven F. - Reinventing A Sacred Past in Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Poetry (An Introduction Five Afro-Brazilian Poets)Document39 pagesWhite, Steven F. - Reinventing A Sacred Past in Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Poetry (An Introduction Five Afro-Brazilian Poets)Marcus ViníciusNo ratings yet

- The Space In-Between Essays On Latin American Culture (Silviano Santiago)Document197 pagesThe Space In-Between Essays On Latin American Culture (Silviano Santiago)Alexandra ErdosNo ratings yet

- Dean & Leibsohn - Hybridity and Its Discontents Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish AmericaDocument33 pagesDean & Leibsohn - Hybridity and Its Discontents Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish AmericaJuan GomezNo ratings yet

- Cocktail Reception With Mitt Romney For Romney Victory Inc.Document2 pagesCocktail Reception With Mitt Romney For Romney Victory Inc.Sunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- The Future of Comparative Politics Is Its PastDocument13 pagesThe Future of Comparative Politics Is Its PasthugoNo ratings yet

- Consing V CADocument2 pagesConsing V CACarl AngeloNo ratings yet

- 26 Jusmag Philippines vs. NLRCDocument2 pages26 Jusmag Philippines vs. NLRCMavic Morales100% (3)

- Data Pegawai Untuk BalihoDocument26 pagesData Pegawai Untuk BalihoWa Ode SuriantiNo ratings yet

- Who Killed Democracy in Africa PDFDocument12 pagesWho Killed Democracy in Africa PDFAnonymous 7AMqr4No ratings yet

- This Week in Syria, DeeplyDocument2 pagesThis Week in Syria, DeeplyimpunitywatchNo ratings yet

- Posting Plan: Government of Pakistan Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) (Recruitment On Contract Basis)Document1 pagePosting Plan: Government of Pakistan Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) (Recruitment On Contract Basis)Suhyl AhmedNo ratings yet

- In Partial Fulfillment For The Requirement in Economics: Lira, Liezel ADocument4 pagesIn Partial Fulfillment For The Requirement in Economics: Lira, Liezel ARea Ann Autor LiraNo ratings yet

- List of PRI Members of Zilla Parishad (Zone Wise) of Kendrapara DistrictDocument3 pagesList of PRI Members of Zilla Parishad (Zone Wise) of Kendrapara DistrictGOutam DashNo ratings yet

- Vellama D/o Marie Muthu V Attorney-General (2012) SGHC 74Document9 pagesVellama D/o Marie Muthu V Attorney-General (2012) SGHC 74Gavin NgNo ratings yet

- Deped Child Protection PolicyDocument50 pagesDeped Child Protection Policymark montenegro100% (1)

- Elu Va-Elu Divre Elokim HayyimDocument17 pagesElu Va-Elu Divre Elokim HayyimarienimNo ratings yet

- Respondent - Sample MemorialDocument23 pagesRespondent - Sample MemorialAMITHAB SANKARNo ratings yet

- The National Bolshevist ManifestoDocument88 pagesThe National Bolshevist ManifestoSp At100% (4)

- Critical AnalysisDocument3 pagesCritical AnalysisGERRY CHEL LAURENTENo ratings yet

- City of Lapu-Lapu v. Philippine Economic Zone AuthorityDocument92 pagesCity of Lapu-Lapu v. Philippine Economic Zone Authorityblue_blue_blue_blue_blueNo ratings yet

- Analisis Kontrastif Nominalisasi Dalam Bahasa Inggris, Bahasa Indonesia, Dan Bahasa JawaDocument17 pagesAnalisis Kontrastif Nominalisasi Dalam Bahasa Inggris, Bahasa Indonesia, Dan Bahasa JawaZelda NameNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Concept of HeroDocument28 pagesLesson 2: Concept of HeroRhiza Paelmo IINo ratings yet

- History of The Peace Corps in MoroccoDocument5 pagesHistory of The Peace Corps in MoroccoTaoufik AfkinichNo ratings yet

- Bull Cat 4Document66 pagesBull Cat 4totochakraborty0% (1)

- Roman Involvement in Anatolia, 167-88 B.C. Author(s) : A. N. Sherwin-White Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 67 (1977), Pp. 62-75 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 03/10/2010 01:21Document15 pagesRoman Involvement in Anatolia, 167-88 B.C. Author(s) : A. N. Sherwin-White Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 67 (1977), Pp. 62-75 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 03/10/2010 01:21Daniel BogdanNo ratings yet

- Ghida NouriDocument1 pageGhida Nouriapi-210149307No ratings yet

- Leadership AnalysisDocument8 pagesLeadership Analysisapi-276879599No ratings yet

- 98Document1 page98Muhammad OmerNo ratings yet