Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Geriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. Tucker

Geriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. Tucker

Uploaded by

Dini indrianyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Dialysis Notes 1Document3 pagesDialysis Notes 1SarahSigrid88% (24)

- Depression OutlineDocument8 pagesDepression OutlineErica93% (15)

- Coping, Stress, and Negative Childhood Experiences The Link To Psychopathology, Self-Harm, and Suicidal BehaviorDocument14 pagesCoping, Stress, and Negative Childhood Experiences The Link To Psychopathology, Self-Harm, and Suicidal BehaviorDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Prismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFDocument5 pagesPrismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFalex100% (1)

- Manejo Depresion 1Document10 pagesManejo Depresion 1Luis HaroNo ratings yet

- Park, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionDocument10 pagesPark, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionFabian WelchNo ratings yet

- Depression in The Elderly: Clinical PracticeDocument9 pagesDepression in The Elderly: Clinical PracticejpenasotoNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Treatment of Major Depression in Older AdultsDocument7 pagesAssessment and Treatment of Major Depression in Older AdultsNelson GuerraNo ratings yet

- Depression in The ElderlyDocument9 pagesDepression in The Elderlyscabrera_scribd100% (1)

- Comorbid Depression in Medical DiseasesDocument22 pagesComorbid Depression in Medical DiseasesArmando Marín FloresNo ratings yet

- Unsaved Preview Document 3Document6 pagesUnsaved Preview Document 3NadewdewNo ratings yet

- 06 Fagiolini 3Document10 pages06 Fagiolini 3gibbiNo ratings yet

- Trastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasDocument15 pagesTrastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasManuel Dacio Castañeda CabelloNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareMaria Jose OcNo ratings yet

- Depression in Cancer Patients: Pathogenesis, Implications and Treatment (Review)Document6 pagesDepression in Cancer Patients: Pathogenesis, Implications and Treatment (Review)Fira KhasanahNo ratings yet

- Mitchell Et All 2011 Prevalence Depression Anxiety Oncoligical HaematologicalDocument15 pagesMitchell Et All 2011 Prevalence Depression Anxiety Oncoligical HaematologicalGuillermoNo ratings yet

- Crit Care Nurse 2014 Chapa 14 25Document12 pagesCrit Care Nurse 2014 Chapa 14 25Ferdy LainsamputtyNo ratings yet

- Depression After Stroke-Frequency, Risk Factors, and Mortality OutcomesDocument2 pagesDepression After Stroke-Frequency, Risk Factors, and Mortality OutcomesCecilia FRNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Depression in Elderly PatientsDocument8 pagesDiagnosis of Depression in Elderly PatientsJosé Jair Campos ReisNo ratings yet

- Depression in Doctors A Bitter Pill To SwallowDocument5 pagesDepression in Doctors A Bitter Pill To SwallowSusan FNo ratings yet

- DialoguesClinNeurosci 13 101Document8 pagesDialoguesClinNeurosci 13 101Fira KhasanahNo ratings yet

- Komorbid 1Document15 pagesKomorbid 1ErioRakiharaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Late-Life Unipolar Depression - UpToDateDocument60 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Late-Life Unipolar Depression - UpToDatearthur argantaraNo ratings yet

- Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument8 pagesGeneralized Anxiety DisorderTanvi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Galuh Nilam P 1041511073 DepresiDocument15 pagesGaluh Nilam P 1041511073 DepresiThiiwiie'thiiwiie PrathiiwiieNo ratings yet

- Depresion en GeriatricosDocument6 pagesDepresion en GeriatricosmmsNo ratings yet

- Suicide and Treatm EntDocument8 pagesSuicide and Treatm EntSourav DasNo ratings yet

- Janberidze Et Al 2015Document10 pagesJanberidze Et Al 2015Elene JanberidzeNo ratings yet

- Comorbidity of Depression With Physical Disorders: Research and Clinical ImplicationsDocument11 pagesComorbidity of Depression With Physical Disorders: Research and Clinical ImplicationsEduardo Niieto MoralesNo ratings yet

- Depresion y Ciclo MenstrualDocument10 pagesDepresion y Ciclo MenstrualPaloma CorreaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument15 pagesHHS Public AccessReginaNo ratings yet

- s11 PDFDocument11 pagess11 PDFIwanNo ratings yet

- J Jocn 2017 09 022Document5 pagesJ Jocn 2017 09 022ÁngelesNo ratings yet

- Identifying and Treating Depression in Patients With Heart FailureDocument10 pagesIdentifying and Treating Depression in Patients With Heart FailureTri Anny RakhmawatiNo ratings yet

- Reading Practice - CNNDocument6 pagesReading Practice - CNNThang Thang100% (1)

- DepressionDocument9 pagesDepressionErica100% (4)

- A Key Problem For Medicine in TheDocument2 pagesA Key Problem For Medicine in TheSenaNo ratings yet

- Judd 1997Document3 pagesJudd 1997María CastilloNo ratings yet

- First Page PDFDocument1 pageFirst Page PDFFernanda SilveiraNo ratings yet

- 120-Article Text-616-1-10-20230414Document6 pages120-Article Text-616-1-10-20230414NOOR SYAFAWATI HANUN MOHD SOBRINo ratings yet

- NMSPostgrad Med J 2008 Jackson 121 6Document7 pagesNMSPostgrad Med J 2008 Jackson 121 6afeda_886608No ratings yet

- Depressao Ansiedade Pcte TerminalDocument4 pagesDepressao Ansiedade Pcte Terminalgabrielapetitot_9179No ratings yet

- A Longitudinal Follow-Up Study of Anti-Depressant Drugs Causing Hepatotoxicity in Patients With Major Depressive DisordersDocument4 pagesA Longitudinal Follow-Up Study of Anti-Depressant Drugs Causing Hepatotoxicity in Patients With Major Depressive DisordersAbdul SamadNo ratings yet

- Fatigue Review OkDocument9 pagesFatigue Review OkDacson LacerdaNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Epidemiology, Comorbidity, and DiagnosisDocument11 pagesSeminar: Epidemiology, Comorbidity, and DiagnosisMartin GiraudoNo ratings yet

- Nejmp 1311047Document3 pagesNejmp 1311047Sebastian Andres Salazar VidalNo ratings yet

- 7 MardervigilanciaDocument7 pages7 Mardervigilanciamahysp7170sanchezislasNo ratings yet

- Delirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewDocument9 pagesDelirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewCristopher Castro RdNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology AntidepresantDocument17 pagesPharmacology Antidepresantandhita96No ratings yet

- Palazidou 2012Document19 pagesPalazidou 2012gharrisanNo ratings yet

- PCC 11258Document5 pagesPCC 11258Alina PopaNo ratings yet

- Implicaţiile Stărilor Depresive Asupra Patologiei SomaticeDocument8 pagesImplicaţiile Stărilor Depresive Asupra Patologiei SomaticeaesocidNo ratings yet

- Inter TB Konsep WordDocument8 pagesInter TB Konsep WordHariCexinkwaeNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Management of Late-Life DepressionDocument8 pagesAssessment and Management of Late-Life DepressionIzza Aliya KennedyNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1059131106001208Document5 pagesPi Is 1059131106001208Murli manoher chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Depression in adolescentsDocument5 pagesDepression in adolescentsJosé Luis AyalaNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial Infarction and Depression: Sabri K. Shaikhow, MBCHB, MRCP, FRCP, Alias A. Hussin, MBCHB, CabsDocument12 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarction and Depression: Sabri K. Shaikhow, MBCHB, MRCP, FRCP, Alias A. Hussin, MBCHB, Cabssarhang talebaniNo ratings yet

- Delirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsDocument11 pagesDelirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- DepresssionDocument10 pagesDepresssionShajid Shahriar ShimantoNo ratings yet

- Delirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsDocument11 pagesDelirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsNavodith FernandoNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric in MDRDocument11 pagesPsychiatric in MDRArnab ChaudhuriNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Behavioral Emergencies - Geriatric Psychiatric PatientDocument14 pages2017 - Behavioral Emergencies - Geriatric Psychiatric PatientAna María Arenas DávilaNo ratings yet

- The Holistic Approach to Redefining Cancer: Free Your Mind, Embrace Your Body, Feel Your Emotions, Nourish Your SoulFrom EverandThe Holistic Approach to Redefining Cancer: Free Your Mind, Embrace Your Body, Feel Your Emotions, Nourish Your SoulNo ratings yet

- Palliative Sedation at The End of Life: Patterns of Use in An Israeli HospiceDocument5 pagesPalliative Sedation at The End of Life: Patterns of Use in An Israeli HospiceDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument21 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- 7226 FullDocument13 pages7226 FullDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Attempted Suicide in Gay and Bisexual YouthDocument9 pagesRisk Factors For Attempted Suicide in Gay and Bisexual YouthDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Medical and Psychiatric ComorbiditiesDocument6 pagesMedical and Psychiatric ComorbiditiesDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ForensikDocument9 pagesJurnal ForensikDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- MBChB4 5PastPapersDocument172 pagesMBChB4 5PastPapersHariharan NarendranNo ratings yet

- History of Dialysis: DR Manjunath JDocument65 pagesHistory of Dialysis: DR Manjunath JDani Dany100% (1)

- Chapter 8Document14 pagesChapter 8Farhad HossainNo ratings yet

- The Best Foods To Increase Kidney FunctionDocument12 pagesThe Best Foods To Increase Kidney Functionindian2011No ratings yet

- ICD 10 CM Coding - DiabetesDocument68 pagesICD 10 CM Coding - Diabeteschaitanya varmaNo ratings yet

- Nursing CS Acute-Kidney-Injury 04Document1 pageNursing CS Acute-Kidney-Injury 04Mahdia akterNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Expenditure Burden of Disease and Management in 5 Eu CountriesDocument123 pagesDiabetes Expenditure Burden of Disease and Management in 5 Eu CountrieszilahparviNo ratings yet

- Chronic Renal FailureDocument54 pagesChronic Renal FailureAkia Cayasan BayaNo ratings yet

- Mumbai Claim FormDocument5 pagesMumbai Claim FormsunsangraNo ratings yet

- Department of Chemical Pathology 2019-2020: Status CompletedDocument5 pagesDepartment of Chemical Pathology 2019-2020: Status CompletedIdrissa John Sebeh ContehNo ratings yet

- Session 19Document6 pagesSession 19nicoleangela ubasroselloNo ratings yet

- 6 Poststreptococcal GlomerulonephritisDocument20 pages6 Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritisbrunob78No ratings yet

- MHD Exam 5 MaterialDocument122 pagesMHD Exam 5 Materialnaexuis5467100% (1)

- Chronic Renal Disease and Risk of Cardiovascular Morbidity-MortalityDocument6 pagesChronic Renal Disease and Risk of Cardiovascular Morbidity-MortalityPaola QuindeNo ratings yet

- PHCP FinalsDocument75 pagesPHCP FinalsSamantha SantosNo ratings yet

- NURS1027 Course Outline FALL 2010Document11 pagesNURS1027 Course Outline FALL 2010Lee KyoJeongNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Natural Killer Cells in HCV Patients Undergoing HemodialysisDocument13 pagesEvaluation of Natural Killer Cells in HCV Patients Undergoing HemodialysisMaged SaadNo ratings yet

- Aditya Birla Sun Life Insurance Life Shield PlanDocument12 pagesAditya Birla Sun Life Insurance Life Shield PlanRitesh AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Ronco - Textbook of Cardiorenal Medicine 2021Document381 pagesRonco - Textbook of Cardiorenal Medicine 2021Adiel OjedaNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation On Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) : Presented By: Mahitha Karimsetti 616175802018 Pharm. D InternDocument35 pagesCase Presentation On Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) : Presented By: Mahitha Karimsetti 616175802018 Pharm. D Internsrija vijjapuNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Midterm HandoutDocument17 pagesNCLEX Midterm Handoutjomel magalonaNo ratings yet

- CKD - For Concept MappingDocument7 pagesCKD - For Concept MappingKennette Lim0% (1)

- Where Are You Going, Nephrology? Considerations On Models of Care in An Evolving DisciplineDocument13 pagesWhere Are You Going, Nephrology? Considerations On Models of Care in An Evolving DisciplineEdmilson R. LimaNo ratings yet

- Aims of Obstetric Critical Care Management 160303161653 PDFDocument25 pagesAims of Obstetric Critical Care Management 160303161653 PDFNinaNo ratings yet

- Combination Therapy Hemodialysis-Hemoperfusion in Dialysis Patients Dr. Jonny, SP - PD-KGH, M.Kes, MMDocument32 pagesCombination Therapy Hemodialysis-Hemoperfusion in Dialysis Patients Dr. Jonny, SP - PD-KGH, M.Kes, MMAzzis MualifNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY ON ACUTE Renal FailureDocument38 pagesCASE STUDY ON ACUTE Renal FailureOdey Godwin100% (1)

- Nurco-2 (Deliverables) Group 4-2Document3 pagesNurco-2 (Deliverables) Group 4-2Nur Fatima SanaaniNo ratings yet

- Renal Exam Class TestDocument8 pagesRenal Exam Class Test1fleetingNo ratings yet

Geriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. Tucker

Geriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. Tucker

Uploaded by

Dini indrianyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Geriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. Tucker

Geriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. Tucker

Uploaded by

Dini indrianyCopyright:

Available Formats

Geriatric Depression

Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. Tucker

Depression in the elderly is more common than once thought, especially in nursing home settings,

where as many as 25% of residents can exhibit signs and symptoms of depression. Depression in the el-

derly can have a significant impact on overall health and desired outcome. The depressed elderly pa-

tient has been shown to have worsened prognosis of concomitant medical conditions, increased use of

health care, decreased recovery time, and more likelihood to experience accelerated physical deterio-

ration. Suicide represents the most serious complication of depression of the older depressed individ-

ual. The elderly are at a disproportionate risk for suicide attempts and are more likely to be successful.

Diagnosis should be made using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) (DSM-

IV) criteria, and clinicians should use standardized rating scales such as the Geriatric Depression Scale

to assist in monitoring the severity of depressive symptoms and the efficacy of antidepressant treat-

ment. Several treatment options are available to the clinician and include psychotherapy, electro-

convulsive therapy, older antidepressants such as the tricyclics, and newer more tolerable therapies

such as the serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Drug therapy should be individualized and should take into

account the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes that are associated with normal aging.

KEY WORDS: depression, elderly, suicide, SSRI, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic geriatric depression.

INTRODUCTION cians and patients view symptoms of depres-

sion as an inevitable consequence of late life,

elderly population is both evidence and experts agree that depres-

D EPRESSION IN THE

more common than once previously

thought. Recognition and treatment of this dis-

sion is not a normal condition of the elderly.

Depression causes more social disability than

order can be confounded by physiologic and many other common ailments of late life such

psychological changes that are part of the nor- as diabetes, arthritis, back pain, hypertension,

mal process of aging. Depression in the elderly and cardiovascular disease.3 Adequate and

is associated with increased mortality, de- efficacious antidepressant treatment strategies

creased quality of life, and worsened prognosis for late-life depression exist; however, recogni-

of accompanying medical disorders.1 Elderly tion and assessment as well as provider educa-

depression is associated with an increased risk tion must be enhanced to improve the treatment

of completed suicide.2 Although many physi- of this disorder.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed: Ste-

phen C. Cooke, PharmD, BCPP, Director of Pharmacy Ser- EPIDEMIOLOGY

vices, Memphis Mental Health Institute, 865 Poplar Avenue,

Memphis, TN 38105 and Assistant Professor, University of Ten-

nessee, College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacy Prac- Studies analyzed by the National Institutes

tice, 847 Monroe Avenue, Suite 210, Memphis, TN 38163. E- of Health Consensus Panel on Diagnosis and

mail: scooke6024@aol.com Treatment of Depression in Late Life show that

Melissa L. Tucker, PharmD, Psychiatric Pharmacy Practice

Resident, University of Tennessee, College of Pharmacy, De-

15% of elderly individuals in community sam-

partment of Pharmacy Practice, 847 Monroe Avenue, Suite 210, ples showed evidence of depressive symptoms.

Memphis, TN 38163.

498 JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

DOI: 10.1106/76VR-VNP7-T1EW-6HGY

© 2001 Sage Publications

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

GERIATRIC DEPRESSION 499

Fully 3% met criteria for major depression.4 Of Depression is common in patients with

particular note and concern was the finding that chronic pain syndromes such as cancer and

elderly residents of nursing homes are at a dis- rheumatoid arthritis. Up to 50% of patients

proportionately high risk, with a prevalence of with chronic pain will experience depression.13

major depression between 15% and 25% and Pain and depression are so intertwined that ade-

an incidence of approximately 13% of new quate antidepressant therapy can itself reduce

cases each year. severity of chronic pain. Current recommenda-

tions suggest that depression screens be rou-

tinely used during chronic pain evaluation and

ASSOCIATED DISORDERS treatment.

Several neurological and psychiatric disor-

Medical comorbidity is common and is ders have also been shown to be associated with

associated with worsened disease outcome, in- depression. As many as one-fourth of Alzhei-

creased health care use, decreased recovery mer’s patients will exhibit signs of depres-

time, delayed resumption of normal activities, sion.14 Parkinson’s patients appear to be at par-

and interference with treatment compliance.3 ticular risk, with almost 50% experiencing de-

The relationship between cardiovascular dis- pressive symptoms.15 Depressive episodes are

ease and depression has been reported for over also common in patients who have also been di-

60 years.5 Up to 30% of patients recovering agnosed with anxiety or substance abuse or

from stroke experience depression.6 Almost who are experiencing withdrawal from sub-

20% of patients who have had a recent myocar- stances of abuse, particularly cocaine.

dial infarction will meet criteria for major de-

pression.7 Rates of coexisting depression in pa-

tients with coronary artery disease have been COMPLICATIONS

reported as high as 18%.8 In all of these groups,

mortality is increased and overall prognosis is Depression has been shown to accelerate

diminished as compared to patients who are not physical deterioration in the elderly. A large

depressed.7,9 The relationship between cardio- study of community residents that assessed

vascular disease and depression is confounded physical function over a 4-year period showed

by several factors. Patients with depression that depressive symptoms were predictive of

have a higher rate of cigarette smoking, a loss of physical skills and self-care.16 This

known modifiable risk factor for cardiovascu- finding is especially important as individuals

lar disease. These patients are also less likely to with declining self-care skills are at risk for

succeed in smoking cessation efforts.10 How- nursing home placement. Adequate identifica-

ever, several studies that controlled for smok- tion and treatment of these individuals may de-

ing, as well as other cardiovascular risk factors, crease subsequent admission to long-term care

still showed an increase in ischemic heart dis- facilities.

ease in those study patients who were de- The most severe and serious complication of

pressed.11 Some researchers have also hypoth- depression, at any age, is suicide. Although

esized that increased cardiovascular risk is they represent only 13% of the U.S. population,

secondary to the use of tricyclic antidepres- the elderly account for 25% of suicide at-

sants (TCAs), a class of medications that is as- tempts.2 In fact, elderly individuals account for

sociated with slowed cardiac conduction, the highest suicide rate among all age groups.

orthostasis, and fatal ventricular arrhythmias in By age 85, the suicide rate is over twice that en-

overdose. This idea, however, was refuted in a countered in the general population.17 Suicidal

well-designed study that showed that cardio- attempts in the depressed elderly patient are

vascular death rate was actually lower after the also more likely to be successful than in youn-

tricyclics became available.12 ger individuals.2 Tragically, opportunities for

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

500 STEPHEN C. COOKE and MELISSA L. TUCKER

intervention prior to suicidal attempts are often development of depression, increases with nor-

missed. A retrospective study of completed sui- mal aging.20 In addition, older individuals ex-

cide revealed that 75% had seen their primary perience changes in their circadian rhythm that

care provider within 1 month of death, 40% affect sleep architecture to a similar degree as

were seen within 1 week, and 20% were seen that seen in those with depression. Older pa-

within 1 day.18 Simply put, failure to identify, tients exhibit increased periods of nighttime

diagnose, and adequately treat depression can wakefulness, have more difficulty initiating

have tragic consequences. sleep, and also experience decreased stage 4

and rapid-eye-movement sleep.21

Many psychosocial causes of elderly depres-

AGE CLASSIFICATION AND DEFINITIONS sion have also been postulated. Although not

clearly recognized as causative, these psycho-

Generally speaking, patients older than 65 social factors should be identified and ad-

have been traditionally defined as elderly. This dressed in an effort to improve overall treat-

nomenclature is, however, inadequate to de- ment and to possibly reduce or minimize future

scribe the complete range of physiologic func- depressed episodes. According to one psycho-

tion encountered in a sample of older patients. social theory, the development of a triad of neg-

Biologic variability in this population does not ative beliefs regarding self-worth, current ex-

lend itself to precise numerical definitions of periences, and a negative view of the future

“elderly.” Some patients appear and are indeed contribute to elderly depression.19 Stressors

elderly several years prior to the age of 65. Con- can also contribute to the development and se-

versely, some patients in their seventh decade verity of elderly depression. Stressful life

of life are physiologically and functionally events such as the loss of a spouse, onset of a

much younger than their stated age. New termi- major medical illness, retirement, and nursing

nology has been devised to clarify these differ- home placement can herald the onset of a de-

ences. “Young old” describes a person between pression or worsen a depressive episode al-

the ages of 60 and 74. The terms “very old” and ready in place. Other stressors associated with

“old old” are being used to describe individuals elderly depression include loss of mobility, de-

over the age of 75. “Oldest-old” describes an crease in independent decision making, loss of

individual that is greater than 90 years of age. defining roles (“head of family”), debits in

The term “frail elderly” describes an individual mental acumen, and loss of support and peer

who is functionally older than he or she actu- groups.

ally is.

DIAGNOSIS AND EVALUATION

ETIOLOGY

The diagnosis of depression in the elderly

The etiology of depression in the elderly is should be made using the DSM-IV criteria

thought to be influenced by both biological and mentioned elsewhere in this series of articles.

psychosocial components. Biologic factors in The presentation of symptoms in an elderly de-

the elderly, such as hereditary influence and pressed patient may be similar to or may differ

neurotransmitter abnormalities appear to be from a younger depressed patient.22 Elderly de-

similar to younger individuals with depres- pressed patients may exhibit more cognitive

sion.19 Less similar to younger depressed pa- impairment and social isolation and may com-

tients, however, are the neuroendocrine and cir- plain less of dysphoric mood.23 The elderly

cadian rhythm changes that accompany normal may also be more somatically focused, experi-

aging. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic- ence a higher level of fatigue and psychomotor

pituitary-adrenal axis, long associated with the retardation, and complain more about loss

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

GERIATRIC DEPRESSION 501

of interest in usual activities.4 Vegetative become debilitating or severe, antidepressant

complaints such as decreased appetite and treatment (either pharmacotherapy or psycho-

poor sleep may prompt initial contact with therapy) should be initiated. Patients should be

a clinician. reassured that antidepressant therapy does not

The elderly are at increased risk for interfere with the grieving process.27

comorbid medical conditions, and therefore,

generally take more medications than younger

patients. Many diseases and medications have PHARMACOKINETICS

been associated with causing or exacerbating

depression. A comprehensive history regarding Pharmacokinetics is the study of a drug’s ac-

medical conditions and routine medications tion within the body over a period of time. The

taken, including over-the-counter and herbal various components of pharmacokinetics in-

preparations, is invaluable at baseline to assist clude the absorption, distribution, metabolism,

in differential diagnosis. As noted earlier, car- and excretion of drug substances. These pro-

diovascular conditions such as stroke, coronary cesses may change substantially due to physio-

artery disease, and myocardial infarction have logical transformations that occur as a part of

been closely tied to development of depression. the aging process. These age-related changes

Alzheimer’s and other dementias are also com- are often unpredictable and vary from patient

monly linked to depression. Other diseases that to patient (Table 1). In addition to increasing

should be ruled out or evaluated at the time of age, other factors such as comorbid disease

initial evaluation include thyroid abnormali- states, multiple drug regimens, and environ-

ties, diabetes, cancer, vitamin deficiency, mental changes may further influence pharma-

fibromyalgia, inflammatory bowel disease, cokinetic processes.28

multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.24 Alterations in pharmacokinetic processes in

The exact relationship between these diseases elderly patients are extremely important for cli-

and depression is unclear. Some clinicians have nicians to consider when prescribing agents for

hypothesized a direct connection between dis- this population. Most antidepressant studies

ease and neurotransmitter dysregulation. Oth- that have been conducted in the elderly popula-

ers suggest that stress secondary to chronic ill- tion have only included healthy young-old pa-

ness may precipitate depressive symptoms in a tients. Therefore, the adverse effects reported

susceptible elderly patient.25 Current treatment in these studies have limited usefulness in pa-

recommendations suggest treatment of both tients who are elderly with multiple disease

underlying illness and the depressive episode. states and complex drug regimens. It is im-

Medications that have been noted to worsen portant for the clinician to individualize each

or cause depressive symptoms are numerous. patient’s overall physiological status (i.e., nu-

Medications commonly used by the elderly trition, hydration, cardiac output) and sub-

such as steroids, diuretics, nonsteroidal anti- sequently recognize how this status may affect

inflammatory agents, propranolol, methyl- the pharmacokinetic aspects of various medi-

dopa, and central nervous system depressants cations. By individualizing each patient’s drug

such as the benzodiazepines have been impli- therapy, safer and more efficacious dosing regi-

cated in causing or worsening depressive mens may be attained.28

symptoms.26 Absorption of most drugs occurs primarily

A common occurrence for the elderly is be- in the small intestine via passive diffusion. Al-

reavement over the loss of close friends or other terations in gastric motility, gastric emptying,

family members. The process of grief or be- and gastric pH are just a few of the gastrointes-

reavement can resemble a major depressive ep- tinal changes that occur during aging. These

isode. Generally, if bereavement lasts for more physiologic changes may or may not affect how

than a few months or if depressive symptoms the patient absorbs a drug. For example, a de-

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

502 STEPHEN C. COOKE and MELISSA L. TUCKER

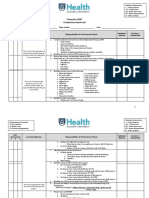

Table 1. Physiologic Changes Relevant to Drug Pharmacokinetics in the Elderly

Pharmacokinetic

Process Physiologic Change Clinical Significance

Absorption Altered gastrointestinal motility Little change in absorption with

Decreased absorptive surface increasing age

Decreased gastric emptying rate

Decreased splanchnic blood flow

Increased gastric pH

Distribution Altered protein binding Increased or decreased unbound

Decreased serum albumin concentration of drugs in plasma

Increased α-acid glycoprotein

Decreased lean body mass Higher concentration of drugs that

Decreased total body weight distribute into body fluids; altered

Increased adipose tissue volume of distribution of some

drugs often leads to a prolonged

elimination half-life

Metabolism Decreased phase I metabolism Decreased hepatic clearance of drugs

No change in phase II metabolism and metabolites with increased

Decreased hepatic blood flow plasma concentrations

Decreased hepatic mass

Elimination Reduced glomerular filtration rate Decreased renal clearance of drugs

Reduced renal blood flow and metabolites with increased

Decreased tubular secretion function plasma concentrations

Adapted from References 28, 29, and 34.

crease in an elderly patient’s gastric motility creased during acute illnesses and inflammation.

can cause a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory The increase in AAG may cause enhanced

drug to remain in contact with the gastric mu- binding of basic drugs with subsequent decre-

cosa for a longer period of time, potentially in- ment in unbound or free fraction of the drug

creasing the risk for ulceration.28,29 leading to subtherapeutic levels and decreased

Active transport is decreased in the elderly pharmacologic effect.33

population. Various nutrient drugs such as thia- As a person ages, the ratio of lean body mass

mine, folic acid, calcium, and iron are absorbed to fat as well as the total body water content of

via this process.30 Use of vitamin supplemen- the person changes, which can affect drug dis-

tation should be a consideration in these pa- tribution and thus pharmacologic response. A

tients because vitamin deficiency has been pos- decrease in lean body mass with a subsequent

tulated as a medical cause of depression.24,29 increase in adipose tissue affects the volumes

Distribution is generally variable in the el- of distribution for hydrophilic as well as

derly population. Elderly patients commonly lipophilic medications. Between the ages of 20

have decreased availability of the plasma pro- and 80 years, total body water content is de-

tein albumin, which is necessary for the bind- creased approximately 10%–15%. Physical in-

ing of acidic drugs. When plasma albumin is activity of the elderly population may also con-

decreased, more active and unbound drug is tribute to these changes that occur in body

available to receptors, placing the patient at risk composition.34

for toxicity.31 Factors that may contribute to the Generally, the volumes of distribution as

decrease in albumin include malnutrition, im- well as the half-lives for hydrophilic medica-

mobility, and chronic illnesses.32 tions are decreased in the elderly.28 Water-

Conversely, α1-acid glycoprotein (AAG) tends soluble drugs, such as lithium and morphine,

to be increased in the elderly population. AAG are distributed primarily in lean body mass or

is an acute phase reactant protein to which body water, which is decreased in the elderly

many basic drugs bind. This protein is also in- population.29 Therefore, a lower dose of water-

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

GERIATRIC DEPRESSION 503

soluble drugs is usually required for these addition, the reduction in hepatic blood flow is

patients to reach therapeutic plasma concentra- the rate-limiting step for medications that are

tions. In addition, shorter intervals between ad- highly metabolized in the liver. As a result, the

ministration times may be required due to the decline in hepatic blood flow, and thus hepatic

decreased half-lives of these water-soluble clearance of the drug, could increase the

medications.35 plasma drug concentrations to potentially toxic

Conversely, lipophilic drugs have increased levels.29

volumes of distribution as well as increased Age-related physiologic changes in hepatic

half-lives in the elderly population due to the metabolizing activity affect the ability of the

accumulation of these agents in adipose tissue. liver to eliminate certain medications from the

Because of the physiologic alterations in this body through biotransformation reactions.29

population, the duration of action and the pro- These reactions involve both microsomal and

cess of eliminating the drug is delayed, poten- nonmicrosomal enzymes and are classified as

tially increasing the risk for adverse effects of either phase I or phase II reactions. Phase I re-

the drug. For example, sedative-hypnotics and actions are normally reduced in the geriatric

analgesics are given on an intermittent basis to patient, while phase II reactions are generally

decrease the incidence of adverse effects com- unaffected by normal aging.34

monly associated with these agents. Diazepam, Phase I reactions are associated with the

a long-acting benzodiazepine, has an almost 2- cytochrome P-450 system and involve oxida-

fold increase in the volume of distribution in tion, reduction, and hydrolysis, typically pro-

elderly patients and a half-life of approxi- ducing compounds with pharmacologic ac-

mately 90 hours compared to 24 hours in young tivity. The key cytochrome P-450 isoenzymes

patients.28 responsible for the metabolism of certain

Metabolism in the liver, excretion by the kid- psychotropic medications include CYP1A2,

neys, or a combination of these processes are CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and the CYP2C subfamily.36

the primary mechanisms by which medications Phase II reactions involve glucuronidation,

are eliminated from the body. Higher plasma acetylation, and sulfation and usually produce

drug concentrations with a subsequent increase inactive metabolites. For example, chlora-

in pharmacologic response can result due to a zepate, diazepam, and prazepam are benzo-

decrease in total body clearance that occurs as a diazepines that undergo biotransformation to

person ages, placing the patient at risk for drug active metabolites via oxidation, a phase I reac-

toxicity. With increasing age, physiologic tion. All of these agents demonstrate decreased

changes regarding kidney function have a greater clearance and prolonged elimination half-lives

influence on drug elimination compared to in the elderly population, increasing the risk of

physiologic changes in hepatic function.29 excessive sedation and other adverse effects.

Age-related physiological changes that oc- Alternately, the benzodiazepines lorazepam,

cur in the hepatic system, such as decreased oxazepam, and temazepam are metabolized to

liver mass, hepatic blood flow, and metaboliz- inactive metabolites by undergoing conjuga-

ing activity, contribute to problems with the tion, a phase II reaction.37 Overall, the cumula-

elimination of medications that are biotrans- tive effect of increased volumes of distribution

formed in the liver. Other factors such as diet, and half-lives in conjunction with decreased

gender, genetics, smoking, concomitant drugs, hepatic metabolism in the elderly population

and diseases can also affect the process of drug may dramatically prolong the desired clinical

metabolism.29 Autopsy studies have shown effect of numerous medications.

that between the ages of 20 and 80 years, Renal function progressively declines with

the size of the liver is decreased approximately age and provides the most consistent reflection

18%–25%, which has been associated with a of aging on pharmacokinetic variables.34,35 Ef-

decreased clearance of certain drugs.34 In fects such as reduced renal blood flow, reduced

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

504 STEPHEN C. COOKE and MELISSA L. TUCKER

glomerular filtration rate (GFR), lack of glomeruli high-risk situations such as suicidality or in in-

in the renal cortex, and diminished tubular se- dividuals with complex comorbidities.24

cretion lead to renal impairment in the elderly Baseline evaluations should include a com-

population.35 Generally, renal blood flow de- plete physical exam including laboratory stud-

clines 1.9% every year. The GFR may decline ies. Clinicians should also routinely make use

as much as 50% as age increases, likely result- of well-validated rating scales such as the

ing in lesser elimination of drugs that are par- patient-rated Geriatric Depression Scale41 or

tially or completely cleared by the kidneys.34 the clinician-administered Hamilton Depres-

Drug elimination is associated with creatinine sion Rating Scale.42 The use of these scales im-

clearance. On average, the creatinine clearance proves diagnostic reliability and can give the

of an individual declines by 50% from the ages clinician a concrete mechanism to evaluate symp-

of 25 to 85 years.28 Common methods of esti- tom progression, symptom severity, and anti-

mating creatinine clearance, such as the ubiqui- depressant efficacy. A complete drug history,

tous Cockcroft and Gault formula, should be including past antidepressant treatment successes

used with a certain degree of caution because and failures, should be recorded at baseline.

some studies have suggested that the formula Individualization of overall antidepressant

may not be accurate for residents of nursing treatment is key to the successful treatment of

homes.38 the elderly depressed patient. Symptom sever-

Decreased renal elimination may lead to pro-

longed half-lives of medications excreted by

the kidneys, resulting in increased plasma con-

centrations. This is particularly important for Individualization of overall

medications with narrow therapeutic indices, antidepressant treatment is key

as clinically significant adverse effects may oc- to successful treatment of the

cur in elderly patients if dosages are not ad- elderly depressed patient.

justed accordingly.28 In addition, elimination

of hydroxy metabolites of tricyclic antidepres-

sants, which are potentially cardiotoxic to el-

derly patients, is dependent on renal function.39 ity, disease comorbidity, economic means, ex-

Since renal function usually declines with age, pected tolerance to adverse effects, concurrent

accumulation of cardiotoxic metabolites may drug therapies, and patient attitude must be

occur and can potentially lead to impaired car- taken into consideration when developing an

diac conduction.40 initial treatment plan. Psychotherapies may be

used as the primary therapy in mild depression

or may be combined with antidepressants in

TREATMENT

more moderate or severe depression.43 Severe

or treatment-resistant depression may respond

The overall goal of any antidepressant treat- to a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

ment modality is to improve and maximize Clinicians that are presented with a clinical

quality of life, to maintain independent living case involving a possible disease-induced de-

skills in a community setting, and finally to pressive episode should generally treat both the

avoid or delay placement in a long-term care fa- depression and the underlying disease for max-

cility or nursing home. In most treatment facili- imal efficacy. Concurrent medications that are

ties, the older depressed individual is most known to worsen depression should be evalu-

likely to be evaluated and subsequently treated ated for possible substitution.

by a primary care practitioner. Psychiatric re- Psychotherapies for geriatric patients, such

ferral to a mental health specialist should be as group therapy, family therapy, and cognitive

made in treatment refractory patients or in therapy, can aid in understanding and adapta-

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

GERIATRIC DEPRESSION 505

tion to the inevitabilities of older age. These Table 2. Dosage Recommendations of Selected

Antidepressants in the Elderly

nonpharmacological therapies can improve

self-esteem, reduce helplessness and anger, Adult: Age < 65 Geriatric: Age ≥ 65

Medication (mg/day) (mg/day)

and can improve quality of life.44 Common is-

sues for the geriatric patient involve grief, fam- Amitriptyline1 75–300 25–150

Bupropion 225–450 50–100

ily and peer losses, assumption of new roles, Citalopram 20–40 20

and acceptance of mortality. Group therapy is Desipramine2 75–300 10–100

especially effective in that it can provide an op- Doxepin 75–300 10–75

Fluoxetine 20–80 10–40

portunity for mutual support as well as provide

Fluvoxamine 50–300 N/A

a mechanism for new friendships at a time Imipramine 75–300 10–150

when many long-term friends may have died. Mirtazapine 15–45 N/A

Family therapy helps to increase familial un- Nefazodone 300–600 N/A

Nortriptyline2 75–300 10–75

derstanding of the changes that an elderly per- Paroxetine2 20–50 10–30

son is undergoing. Involving family can reduce Sertraline2 75–200 25–200

resentment, prevent elder abuse, and can pro- Trazodone 150–600 25–150

Venlafaxine 75–375 N/A

vide the depressed individual with a sense of

belonging and support. Cognitive therapy can Adapted from References 29 and 57.

N/ARecommended dosage range presently unavailable in geriatric

minimize self-induced prejudices about grow- patients.

1Not recommended for use in geriatric patients.

ing older. Cognitive therapy can correct distor- 2Preferred antidepressant in geriatric patients.

tions in thinking, especially as relates to new

skill acquisition, maintenance of sexual activ- maxim to “start low and go slow” has particular

ity, learning, and helping others.45 significance and application in the elderly. Ta-

ECT has been shown to be a safe and effec- ble 2 describes the usual dosage recommenda-

tive treatment for elderly depression, espe- tions of commonly used antidepressants in el-

cially in the context of symptom severity, treat- derly depression.

ment resistance, or the presence of psychosis.46

In fact, elderly individuals make up over one-

half of patients who receive ECT in the United PHARMACOTHERAPY

States.47 Although most studies of ECT have

included only young-old patients, a more re- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

cent study has concluded that ECT is safe and

effective in the old-old patient. The overall con- The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

clusion of this most recent study was that de- (SSRIs) are as efficacious as TCAs and have

spite a higher medical comorbidity and wors- become the preferred medications for the treat-

ened cognitive functioning, ECT is tolerated as ment of depression in most elderly patients due

well as in younger patients and acute to easier dosing schedules and more tolerable

response was similar or better than seen in adverse effects.39,48 Although all SSRIs appear

younger patients.46 to be effective for late-life depression, only

Antidepressant selection, as in younger pa- paroxetine has been studied in patients older

tients, should be based on past history of re- than 80 years of age.39 The primary difference

sponse, avoidance of adverse effects, presence between the SSRIs involves pharmacokinetic

of comorbidities, concurrent medications, and parameters. The SSRIs are highly protein

any known age-related physiological change bound and undergo extensive metabolism.

that would impact pharmacodynamic or Paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine have

pharmacokinetic functioning. The lowest ef- relatively shorter half-lives compared to

fective dose of any antidepressant should be fluoxetine and citalopram. Norfluoxetine, the

used to minimize toxicity and enhance patient active metabolite of fluoxetine, has a 7 to 9 day

acceptance and compliance. The time-honored half-life, possibly leading to accumulation in

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

506 STEPHEN C. COOKE and MELISSA L. TUCKER

the adipose tissue of elderly patients. Clinically, zapine, may also play a role for elderly patients

agents with longer half-lives have the advan- suffering from depression. Compared to the

tage of increased compliance and stable blood TCAs and the SSRIs, these agents have been

concentrations if doses are missed, while studied to a lesser extent in the elderly popula-

agents with shorter half-lives possess the ad- tion. Although there are fewer studies in these

vantage of increased dosing flexibility. Drug patients, clinical experience indicates that

interactions are also a concern due to hepatic these antidepressants are effective in the el-

metabolizing enzymes that are shared between derly. Similar to other antidepressants, these

SSRIs and other medications that are fre- agents should be initiated with lower doses and

quently prescribed in this population.39 slowly titrated to effect in elderly patients.

Compared to the TCAs, the SSRIs report- Bupropion is considered to be a favorable

edly cause more gastrointestinal (GI) adverse antidepressant in many elderly patients due to

effects such as nausea and vomiting, especially its minimal anticholinergic, sedative, ortho-

during the first few weeks of therapy. To help static, and cardiovascular adverse profile. Bup-

alleviate or lessen GI irritation, the patient ropion is believed to inhibit the reuptake of do-

should consume food 20 to 30 minutes before pamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. The

taking these medications.48 In addition, the el- aspect of dopamine reuptake inhibition may be

derly patient should also be monitored for especially useful in patients suffering from de-

weight loss, especially in the low-weight el- pression who also have been diagnosed with

derly. The SSRIs, especially fluoxetine, may Parkinson’s disease. Common adverse effects

cause agitation, anxiety, and/or insomnia in el- include nausea, vomiting, agitation, and in-

derly patients. Decreasing the dose or switch- somnia.48 Because this medication tends to be

ing to a less stimulating antidepressant may be activating for most patients, administration at

helpful in these patients.48,49 bedtime should be avoided. Another adverse

Another adverse effect associated with the effect that limits dosing is the increased risk of

SSRIs is drug-induced parkinsonism. This syn- seizure activity at single doses greater than

drome is characterized by dystonias, akathisia, 150 mg or total daily doses greater than 450 mg.

and potential exacerbation of symptoms in el- Bupropion should be avoided in patients with

derly patients suffering from idiopathic Parkin- seizures.39,48 Elderly patients should be initi-

son’s disease.50,51 In addition, a rare adverse ef- ated with 75 mg twice daily with at least 6 to 8

fect associated with both the TCAs and SSRIs hours between each dose.48 The availability of

is the syndrome of inappropriate antidiurectic a sustained-release (SR) formulation offers an-

hormone secretion (SIADH). Although both other option for elderly which may improve

SIADH and parkinsonism have been primarily compliance. Approximately 6000 patients par-

reported with fluoxetine, data regarding these ticipated in clinical trials with the SR formula-

adverse effects are limited.52,53 tion in which 275 patients were 65 years and

Recommended starting doses for the SSRIs over and 47 were 75 years and older. There

in the elderly population are generally between were no overall differences in the clinical effec-

one-third and one-half of the usual dose for tiveness or safety profile between younger and

young and middle-aged adults. Doses of SSRIs older patients. With the SR formulation, elderly

are usually administered in the morning due to patients should be initiated with 150 mg SR

the stimulating effects, but can be given at bed- daily, preferably as a morning dose.54

time if the patient complains of sedation.48 Trazodone is believed to inhibit the reuptake

of serotonin as well as antagonize the serotonin-

Other Newer Antidepressants 2 postsynaptic receptor, which may contribute

to anti-anxiety effects reported with this medi-

The other newer antidepressants, bupropion, cation. Trazodone also antagonizes alpha-1-

trazodone, nefazodone, venlafaxine, and mirta- adrenergic receptors, resulting in significant

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

GERIATRIC DEPRESSION 507

orthostatic hypotension that commonly occurs lacks the anticholinergic effects that are com-

1 to 2 hours after administration. This adverse monly associated with the TCAs. Adverse effects

effect greatly limits its usefulness as a clini- associated with venlafaxine include nausea,

cally effective antidepressant, especially in el- headache, insomnia, confusion, and a possible

derly patients. Trazodone also inhibits alpha-2- elevation in blood pressure. The adverse effects

adrenergic receptors, which has been reported of venlafaxine emphasize the need for caution

to rarely induce priapism in patients.48 Al- with its use in the elderly population, especially

though trazodone lacks significant anti- those with brittle or severe hypertension.39,48

cholinergic adverse effects, the agent produces This agent is metabolized to an active metabo-

significant sedation in patients. For this reason, lite by the cytochrome P-450 system and is also

the most common use of trazodone in the geri- excreted through the kidneys. Therefore, dos-

atric population is as a sedative-hypnotic.29 age adjustments may be required in elderly pa-

However, for elderly patients who have been tients with renal impairment.48

resistant to other antidepressant therapy, Mirtazapine is a relatively new antidepres-

trazodone may be considered as an alternative sant that antagonizes alpha-2 receptors and is

medication.29,49 postulated to cause an increase in noradrener-

Nefazodone is another atypical antidepres- gic and serotonergic activity. This agent is also

sant that has been used in elderly patients. Like believed to antagonize 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 re-

trazodone, this serotonergic agent is believed to ceptors. Adverse effects associated with mirta-

inhibit the reuptake of serotonin as well as an- zapine include sedation, orthostasis, increased

tagonize serotonin-2 postsynaptic receptors. appetite, weight gain, and increases in triglyc-

Adverse effects frequently experienced with erides and total cholesterol. Because mirta-

this medication include sedation, headache, zapine is substantially excreted by the kidney

and orthostasis.48 This antidepressant has mini- (75%), dosages must be adjusted in patients

mal to no anticholinergic effects, cardiac con- with decreased renal function. A majority of

duction abnormalities, or seizure risk and has elderly patients have impaired renal func-

been found to be safer than TCAs in over- tion and consequently require a lower dose,

dose.55 Nefazodone is metabolized to 3 active especially on initiation of therapy. Due to

metabolites that have relatively shorter half- the risk of oversedation and orthostasis with

lives and therefore requires twice daily dosing. mirtazapine, this antidepressant should be re-

Due to sedation and orthostasis that may occur served as second-line therapy in the elderly

with this medication, doses as low as 50 mg population.56

twice daily are recommended for initiating

drug therapy in elderly patients. Additionally, TCAs

nefazodone inhibits the CYP3A4 enzyme

which is responsible for metabolizing many TCAs are effective medications for elderly

other medications.48 Because elderly patients patients diagnosed with major depression but

are commonly prescribed multiple medica- are more frequently used in lower doses for

tions, it is important to monitor the patient’s chronic pain syndromes. The TCA adverse ef-

medication profile for potential drug interac- fect profile of anticholinergic effects (dry

tions with nefazodone. mouth, blurred vision, constipation, confu-

Venlafaxine is generally used as a second- sion), inhibition of histamine-1 receptor activ-

line agent in elderly patients who have not re- ity (sedation), inhibition of alpha-1-adrenergic

sponded to other antidepressant therapy. This activity (orthostatic hypotension), and prolon-

antidepressant resembles the pharmacologic pro- gation of cardiac repolarization (responsible

file of the TCAs in that it selectively inhibits the for widening of the QT interval) reduce their

reuptake of both norepinephrine and serotonin utility in the elderly.50 The cardiac effects can

from the synaptic cleft.48 However, venlafaxine make TCAs contraindicated in many elderly

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

508 STEPHEN C. COOKE and MELISSA L. TUCKER

patients. The secondary amines (desipramine their adverse effects and drug-drug and drug-

and nortriptyline) are the preferred TCAs for el- food interactions, have not been well studied in

derly patients due to decreased adverse effects and the geriatric population. These medications are

the availability of serum concentration moni- not considered first-line agents used for major

toring.48 However, significant adverse effects depression. However, the MAOIs may be effec-

have been noted in patients who were within tive for elderly patients suffering from atypical

the therapeutic range for the medications. For depression that is characterized by dysphoric

this reason, geriatric patients should also be mood accompanied by increases in vegetative

monitored for signs and symptoms of toxicity, symptoms such as sleep, appetite, and libido.48

whether mild (blurred vision, urinary retention, MAOIs should only be prescribed to re-

and confusion) or severe (arrhythmias and re- sponsible, compliant elderly patients or to el-

spiratory depression).48 derly patients whose medications are closely

Elderly patients with cardiovascular disease, supervised.49

benign prostatic hypertrophy, urinary retention,

narrow-angle glaucoma, or a history of seizures

should be closely supervised while using TCAs. CONCLUSION

Anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth and

constipation may cause severe problems within Depression in the elderly is underdiagnosed,

the gastrointestinal system. Central nervous sys- undertreated, and associated with poor out-

tem anticholinergic effects of these agents are comes. Older depressed individuals are at risk

more pronounced in elderly patients and may for cardiovascular disease, poor quality of life,

cause difficulties with memory and attention,

potentially escalating to severe cognitive impair-

ment over time.35 TCAs should be dosed at

bedtime to decrease the incidence of falls, which MAOIs may be effective

can be serious or possibly fatal in these patients. for elderly patients suffering

Caution is also advised in elderly patients with from atypical depression.

suicidal ideation, given that an accidental or

purposeful overdose of as little as a 2-week

supply of TCAs can prove to be lethal.48

Before initiating TCA therapy in an elderly increased risk of suicide, and worsened prog-

patient, the clinician should obtain a complete nosis of medical comorbidities. Treatment op-

physical exam including an electrocardiogram tions are numerous, effective, and now more

(ECG). Use of the ECG aids the clinician in tolerable than in the past. The SSRIs are cur-

monitoring the patient for potential cardiotoxic rently recognized as the preferred pharmaco-

effects of the TCAs. Starting doses should be therapy due to their improved adverse effect

especially low (e.g., amitriptyline equivalents profile, ease of dosing, and documented effi-

10–25 mg qd), and titrated upward to a dose cacy across all geriatric age groups. Other treat-

that elicits the therapeutic response with the ment options, in the case of treatment failure or

least amount of adverse effects.49 See Table 2 treatment intolerance, include bupropion,

for the usual dosage recommendations of the venlafaxine, and the secondary TCAs,

TCAs and other commonly used antidepres- nortriptyline and desipramine. Failure to rec-

sants in elderly depression. ognize and treat depression in the elderly has

economic, psychosocial, and ethical conse-

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors quences. As the “baby boomer” generation

ages, increased focus and attention on depres-

The monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), sion in the older patient will become even more

phenelzine and tranylcypromine, because of of a priority.

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

GERIATRIC DEPRESSION 509

REFERENCES 18. Clark RC. “Rational” suicide and people with termi-

nal conditions or disabilities. Issues Law Med. 1992;

8:147–66.

1. Montano CB. Primary care issues related to the treat-

19. Blazer D. Depression and the older man. Med Clin

ment of depression in elderly patients. J Clin Psychi-

North Am. 1999; 83(5):1305–16.

atry. 1999; 60(suppl 20):45–51.

2. Conwell Y. Management of suicidal behavior in the 20. Veith R, Raskin M. The neurobiology of aging: does

elderly. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997; 20:667–83. it predispose to depression? Neurobiol Aging. 1988;

9:101–17.

3. Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, et al. Func-

tioning and well-being outcomes of patients with de- 21. Prinz P, Vitello M, Raskind M. Geriatrics: sleep dis-

pression compared with chronic general medical orders and aging. N Engl J Med. 1990; 323:520–6.

illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995; 52:11–19. 22. Donner DL. An overview of paroxetine in the el-

4. National Institutes of Health Consensus Develop- derly. Gerontology. 1994; 40(suppl 1):21–27.

ment Panel on Depression in Late Life. Diagnosis 23. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guide-

and treatment of depression in late life. JAMA. 1992; line for major depressive disorder in adults. Am J

268:1018–24. Psychiatry. 1993; 150(suppl 4):1–26.

5. Malzberg B. Mortality among patients with 24. Mulsant BH, Ganguli MD. Epidemiology and diag-

involutional melancholia. Am J Psychiatry. 1937; nosis of depression in late life. J Clin Psychiatry.

93:1231–8. 1999; 60(suppl 20):9–15.

6. Hermann N, Black SE, Lawrence J, et al. The 25. Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, et al. The impact

Sunnybrook Stroke Study: a prospective study of de- of depressive symptomatology on physical disabil-

pressive symptoms and functional outcome. Stroke. ity: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J

1998; 29:618–24. Public Health. 1994; 84:1796–9.

7. Schleifer SJ, Macari-Hinson MM, Coyle DA, et al. 26. Pies RW, Shader RI. Approaches to the treatment of

The nature and course of depression following myo- depression. In: Shader RI, ed. Manual of Psychiatric

cardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1989; Therapeutics. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown and

149:1785–9. Company: 1994; 22:217–46.

8. Carney RM, Rich MW, Freedland KE. Major de- 27. Pasternak RE, Reynolds CF, Schlernitzauer M, et al.

pressive disorder predicts cardiac events in patients Acute open-trial nortriptyline therapy of bereave-

with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1988; ment-related depression in late life. J Clin Psychia-

50:627–33. try. 1991; 52:307–10.

9. Wells KB, Rogers W, Burnam MA, et al. Course of 28. Beyth RJ, Shorr RI. Medication use. In: Duthie EH,

depression in patients with hypertension, myocar- Katz PR, eds. Practice of Geriatrics. 3rd ed. Phila-

dial infarction, or insulin-dependent diabetes. Am J delphia: W.B. Saunders Company: 1998; 38–47.

Psychiatry. 1993; 150:632–38. 29. Miller SW. Geriatric drug therapy. In Textbook of

10. Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS. Smoking, Therapeutics: Drug and Disease Management. 7th

smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA. ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins:

1990; 264:1546–9. 2000; 2063–76.

11. Roose SP, Spatz E. Treatment of depression in pa- 30. Bhanthumnavin K, Schuster MM. Aging and gastro-

tients with heart disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999; intestinal function. In: Finch CE, Hayflick L, eds.

60(suppl 20):34–37. Handbook of the Biology of Aging. New York: Van

12. Weeke A, Vaeth M. Excess mortality of bipolar and Nostrand Reinhold: 1977; 709–23.

unipolar manic-depressive patients. J Affect Disord. 31. Hayes MJ, Langman, MS, Short AH. Changes in

1986; 11:227–34. drug metabolism with increasing age. Br J Clin

13. Ruoff GE. Depression in the patient with chronic Pharmacol. 1975; 2:73–9.

pain. J Fam Pract. 1996; 43:S25–S34. 32. Greenblatt DJ, Sellers EM, Koch-Weser J. Impor-

14. Reifler BV, Larson E, Hanley R. Coexistence of cog- tance of protein binding for the interpretation of se-

nitive impairment and depression in geriatric outpa- rum or plasma drug concentrations. J Clin

tients. Am J Psychiatry. 1982; 139:623–6. Pharmacol. 1982; 22:259–63.

15. Dooneief G, Mirabello E, Bell K, et al. An estimate 33. Davis D, Grossman SH, Kitchell BB, et al.

of the incidence of depression in idiopathic Parkin- Age related changes in the plasma protein

son’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1992; 49:305–7. binding of lidocaine and diazepam. Clin Res. 1980;

16. Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. De- 28:234A.

pressive symptoms and physical decline in 34. Vestal RE, Gurwitz JH. Geriatric pharmacology. In:

community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 1998; Carruthers SG, Hoffman BB, Melmon, KL,

279:1720–6. Nierenberg DW, eds. Clinical Pharmacology: Basic

17. NIH Consensus Development Conference. Diagno- Principles in Therapeutics. 4th ed. New York:

sis and treatment of depression in late life. NIH Con- McGraw-Hill: 2000:1151–77.

sensus Development Conference Consensus State- 35. Devane CL, Pollock BG. Pharmacokinetic consider-

ment. 1991; 9(3,Nov):4–6. ations of antidepressant use in the elderly. J Clin

Psychiatry. 1999; 60(suppl 20):38–44.

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

510 STEPHEN C. COOKE and MELISSA L. TUCKER

36. Devine B. Gantamycin therapy. Drug Intel Clin sion in the old-old. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;

Pharm. 1974; 8:650–5. 156(12):1865–70.

37. Bellantuono C, Reggi V, Tognoni G, et al. Benzo- 47. Olfson M, Marcus M, Sackheim HA, et al. Use of

diazepines: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic ECT for the inpatient treatment of recurrent major

use. Drugs. 1980; 19:195–219. depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998; 155:22–29.

38. Drusano GL, Munice HL, et al. Commonly used 48. Hay DP, Franson KL, Hay L, Grossberg GT. Depres-

methods of estimating creatinine clearance are inad- sion. In: Duthie EH, Katz PR, eds. Practice of Geri-

equate for elderly debilitated nursing home patients. atrics, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Com-

J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988; 36:437–41. pany: 1998; 286–94.

39. Salzman, Carl. Practical considerations for the treat- 49. Salzman C, Satlin A, Burrows AB. Geriatric

ment of depression in elderly and very elderly long- psychopharmacology. In: Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff

term care patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999; 60 (suppl CB, eds. The American Psychiatric Press Textbook

20):30–33. of Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: Ameri-

40. Kutcher SP, Reid K, et al. Electrocardiogram can Psychiatric Press: 1995; 803–21.

changes and therapeutic desipramine and 2- 50. Steur E. Increase of Parkinson disability after

hydroxydesipramine concentrations in elderly de- fluoxetine medication. Neurology. 1993; 43:211–3.

pressives. Br J Psychiatry. 1986; 148:676–9. 51. Caley CF, Friedman JH. Does fluoxetine exacerbate

41. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Develop- Parkinson’s disease? J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;

ment and validation of a geriatric depression screen- 57:278–82.

ing scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 52. Sharma H, Pompei P. Antidepressant-induced

1983; 17:1737–49. hyponatremia in the aged: avoidance and manage-

42. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol ment strategies. Drugs Aging. 1996; 8:430–5.

Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960; 23:56–62. 53. Woo MH, Smythe MA. Association of SIADH with

43. Reynolds CF, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, et al. Treatment selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Ann

outcome in recurent major depression: a post hoc Pharmacotherapy. 1997; 31:108–9.

comparison of elderly (“young-old”) and midlife pa- 54. Bupropion package insert. Greenville, NC:

tients. Am J Psychiatry. 1996; 153:1288–92. GlaxoWellcome; 1999 Sept.

44. Weiss LJ, Lazarus LW. Psychosocial treatment of 55. Preskorn SH. Recent pharmacologic advances in an-

the geropsychiatric patient. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. tidepressant therapy for the elderly. Am J Med. 1993;

1993; 8:95–106. 94(suppl 5A):2S–12S.

45. Geriatric Psychiatry. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. 56. Mirtazapine package insert. West Orange, NJ:

Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Organon; 1999 Mar.

Psychiatry, 8th ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins 57. Citalopram package insert. St. Louis, MO: Forest

1998; 54:1289–1304. Laboratories; 2000 May.

46. Tew JD, Mulsant BH, Haskett RF, et al. Acute

efficacy of ECT in the treatment of major depres-

JOURNAL OF PHARMACY PRACTICE, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2001

Downloaded from jpp.sagepub.com at Universitas Padjadjaran on July 25, 2016

You might also like

- Dialysis Notes 1Document3 pagesDialysis Notes 1SarahSigrid88% (24)

- Depression OutlineDocument8 pagesDepression OutlineErica93% (15)

- Coping, Stress, and Negative Childhood Experiences The Link To Psychopathology, Self-Harm, and Suicidal BehaviorDocument14 pagesCoping, Stress, and Negative Childhood Experiences The Link To Psychopathology, Self-Harm, and Suicidal BehaviorDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Prismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFDocument5 pagesPrismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFalex100% (1)

- Manejo Depresion 1Document10 pagesManejo Depresion 1Luis HaroNo ratings yet

- Park, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionDocument10 pagesPark, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionFabian WelchNo ratings yet

- Depression in The Elderly: Clinical PracticeDocument9 pagesDepression in The Elderly: Clinical PracticejpenasotoNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Treatment of Major Depression in Older AdultsDocument7 pagesAssessment and Treatment of Major Depression in Older AdultsNelson GuerraNo ratings yet

- Depression in The ElderlyDocument9 pagesDepression in The Elderlyscabrera_scribd100% (1)

- Comorbid Depression in Medical DiseasesDocument22 pagesComorbid Depression in Medical DiseasesArmando Marín FloresNo ratings yet

- Unsaved Preview Document 3Document6 pagesUnsaved Preview Document 3NadewdewNo ratings yet

- 06 Fagiolini 3Document10 pages06 Fagiolini 3gibbiNo ratings yet

- Trastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasDocument15 pagesTrastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasManuel Dacio Castañeda CabelloNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareMaria Jose OcNo ratings yet

- Depression in Cancer Patients: Pathogenesis, Implications and Treatment (Review)Document6 pagesDepression in Cancer Patients: Pathogenesis, Implications and Treatment (Review)Fira KhasanahNo ratings yet

- Mitchell Et All 2011 Prevalence Depression Anxiety Oncoligical HaematologicalDocument15 pagesMitchell Et All 2011 Prevalence Depression Anxiety Oncoligical HaematologicalGuillermoNo ratings yet

- Crit Care Nurse 2014 Chapa 14 25Document12 pagesCrit Care Nurse 2014 Chapa 14 25Ferdy LainsamputtyNo ratings yet

- Depression After Stroke-Frequency, Risk Factors, and Mortality OutcomesDocument2 pagesDepression After Stroke-Frequency, Risk Factors, and Mortality OutcomesCecilia FRNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Depression in Elderly PatientsDocument8 pagesDiagnosis of Depression in Elderly PatientsJosé Jair Campos ReisNo ratings yet

- Depression in Doctors A Bitter Pill To SwallowDocument5 pagesDepression in Doctors A Bitter Pill To SwallowSusan FNo ratings yet

- DialoguesClinNeurosci 13 101Document8 pagesDialoguesClinNeurosci 13 101Fira KhasanahNo ratings yet

- Komorbid 1Document15 pagesKomorbid 1ErioRakiharaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Late-Life Unipolar Depression - UpToDateDocument60 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Late-Life Unipolar Depression - UpToDatearthur argantaraNo ratings yet

- Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument8 pagesGeneralized Anxiety DisorderTanvi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Galuh Nilam P 1041511073 DepresiDocument15 pagesGaluh Nilam P 1041511073 DepresiThiiwiie'thiiwiie PrathiiwiieNo ratings yet

- Depresion en GeriatricosDocument6 pagesDepresion en GeriatricosmmsNo ratings yet

- Suicide and Treatm EntDocument8 pagesSuicide and Treatm EntSourav DasNo ratings yet

- Janberidze Et Al 2015Document10 pagesJanberidze Et Al 2015Elene JanberidzeNo ratings yet

- Comorbidity of Depression With Physical Disorders: Research and Clinical ImplicationsDocument11 pagesComorbidity of Depression With Physical Disorders: Research and Clinical ImplicationsEduardo Niieto MoralesNo ratings yet

- Depresion y Ciclo MenstrualDocument10 pagesDepresion y Ciclo MenstrualPaloma CorreaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument15 pagesHHS Public AccessReginaNo ratings yet

- s11 PDFDocument11 pagess11 PDFIwanNo ratings yet

- J Jocn 2017 09 022Document5 pagesJ Jocn 2017 09 022ÁngelesNo ratings yet

- Identifying and Treating Depression in Patients With Heart FailureDocument10 pagesIdentifying and Treating Depression in Patients With Heart FailureTri Anny RakhmawatiNo ratings yet

- Reading Practice - CNNDocument6 pagesReading Practice - CNNThang Thang100% (1)

- DepressionDocument9 pagesDepressionErica100% (4)

- A Key Problem For Medicine in TheDocument2 pagesA Key Problem For Medicine in TheSenaNo ratings yet

- Judd 1997Document3 pagesJudd 1997María CastilloNo ratings yet

- First Page PDFDocument1 pageFirst Page PDFFernanda SilveiraNo ratings yet

- 120-Article Text-616-1-10-20230414Document6 pages120-Article Text-616-1-10-20230414NOOR SYAFAWATI HANUN MOHD SOBRINo ratings yet

- NMSPostgrad Med J 2008 Jackson 121 6Document7 pagesNMSPostgrad Med J 2008 Jackson 121 6afeda_886608No ratings yet

- Depressao Ansiedade Pcte TerminalDocument4 pagesDepressao Ansiedade Pcte Terminalgabrielapetitot_9179No ratings yet

- A Longitudinal Follow-Up Study of Anti-Depressant Drugs Causing Hepatotoxicity in Patients With Major Depressive DisordersDocument4 pagesA Longitudinal Follow-Up Study of Anti-Depressant Drugs Causing Hepatotoxicity in Patients With Major Depressive DisordersAbdul SamadNo ratings yet

- Fatigue Review OkDocument9 pagesFatigue Review OkDacson LacerdaNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Epidemiology, Comorbidity, and DiagnosisDocument11 pagesSeminar: Epidemiology, Comorbidity, and DiagnosisMartin GiraudoNo ratings yet

- Nejmp 1311047Document3 pagesNejmp 1311047Sebastian Andres Salazar VidalNo ratings yet

- 7 MardervigilanciaDocument7 pages7 Mardervigilanciamahysp7170sanchezislasNo ratings yet

- Delirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewDocument9 pagesDelirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewCristopher Castro RdNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology AntidepresantDocument17 pagesPharmacology Antidepresantandhita96No ratings yet

- Palazidou 2012Document19 pagesPalazidou 2012gharrisanNo ratings yet

- PCC 11258Document5 pagesPCC 11258Alina PopaNo ratings yet

- Implicaţiile Stărilor Depresive Asupra Patologiei SomaticeDocument8 pagesImplicaţiile Stărilor Depresive Asupra Patologiei SomaticeaesocidNo ratings yet

- Inter TB Konsep WordDocument8 pagesInter TB Konsep WordHariCexinkwaeNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Management of Late-Life DepressionDocument8 pagesAssessment and Management of Late-Life DepressionIzza Aliya KennedyNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1059131106001208Document5 pagesPi Is 1059131106001208Murli manoher chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Depression in adolescentsDocument5 pagesDepression in adolescentsJosé Luis AyalaNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial Infarction and Depression: Sabri K. Shaikhow, MBCHB, MRCP, FRCP, Alias A. Hussin, MBCHB, CabsDocument12 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarction and Depression: Sabri K. Shaikhow, MBCHB, MRCP, FRCP, Alias A. Hussin, MBCHB, Cabssarhang talebaniNo ratings yet

- Delirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsDocument11 pagesDelirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- DepresssionDocument10 pagesDepresssionShajid Shahriar ShimantoNo ratings yet

- Delirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsDocument11 pagesDelirium in Hospitalized Older AdultsNavodith FernandoNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric in MDRDocument11 pagesPsychiatric in MDRArnab ChaudhuriNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Behavioral Emergencies - Geriatric Psychiatric PatientDocument14 pages2017 - Behavioral Emergencies - Geriatric Psychiatric PatientAna María Arenas DávilaNo ratings yet

- The Holistic Approach to Redefining Cancer: Free Your Mind, Embrace Your Body, Feel Your Emotions, Nourish Your SoulFrom EverandThe Holistic Approach to Redefining Cancer: Free Your Mind, Embrace Your Body, Feel Your Emotions, Nourish Your SoulNo ratings yet

- Palliative Sedation at The End of Life: Patterns of Use in An Israeli HospiceDocument5 pagesPalliative Sedation at The End of Life: Patterns of Use in An Israeli HospiceDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument21 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- 7226 FullDocument13 pages7226 FullDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Attempted Suicide in Gay and Bisexual YouthDocument9 pagesRisk Factors For Attempted Suicide in Gay and Bisexual YouthDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Medical and Psychiatric ComorbiditiesDocument6 pagesMedical and Psychiatric ComorbiditiesDini indrianyNo ratings yet