Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Incentive Travel: Overview and Case Study of Canada As A Destination For The UK Market

Incentive Travel: Overview and Case Study of Canada As A Destination For The UK Market

Uploaded by

NEFSYA KAMALOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Incentive Travel: Overview and Case Study of Canada As A Destination For The UK Market

Incentive Travel: Overview and Case Study of Canada As A Destination For The UK Market

Uploaded by

NEFSYA KAMALCopyright:

Available Formats

Incentive travel

Overviewand case study of Canada

as a destinationfor the UKmarket

StephenF.Witt,SusanGammonandJillWhi

The role of incentive travel is discussed The UK (generated) incentive travel market appears to have experi-

and the potential of the UK (generated) enced rapid growth during recent years in the number of user companies

incentive travel market is examined.

The study focuses on Canada as an

engaging in incentive travel schemes, in the number of incentive travel

incentive travel destination for the UK organizers (providers) and in the value of the industry. Corresponding-

market, and reports the results of a ly, the competition among national tour&t organizations (NTOs) to

survey of UK incentive travel organiz-

ers. Canada appears to have much to

attract this market has become fierce. There are over 40 NTOs vying for

offer as an incentive travel destination, market share, and it is believed that the majority of these has dedicated

but its image and tourism product ben- staff and resources.

efits need to be clearly defined and

projected in order to be able to compete Canada has been faced with a declining VFR (visits to friends and

better with other long-haul incentive relatives) market and a rising deficit on the balance of payments. The

travel destinations. Tourism Section of the Canadian High Commission and the Ontario

Stephen F. Witt is Lewis Professor of Tour- Regional Tourist Office therefore expressed interest in increasing

Ism Studies and Susan Gammon is Canada’s penetration of the UK incentive travel market. In 1989

research assistant in Tourism in the Euro- research was undertaken with a view to ascertaining the value of the

pean Business Management School,

University of Wales, Singleton Park, market and assisting in formulating decisions regarding product de-

Swansea SA2 8PP, UK. Jill White is Com- velopment and promotional strategy. This paper presents the main

mercial Officer (Tourism) with responsibil- findings of the research. The discussion is based upon a review of the

ity for Meetings and Incentive Travel at the

Canadian High Commission, Canada literature pertaining to incentive travel, together with an analysis of

House, Trafalgar Square, London SWlY primary data collected from in-depth interviews with 14 UK incentive

5BJ, UK. travel organizers during 1989. The study centres around Canada’s

potential as an incentive travel destination for the UK market.

Submitted October 1991; accepted De-

cember 1991.

Background

‘See A. Hampton, ‘The UK incentive travel Within the areas of sales and marketing management, incentives

market: a user’s view’, European Journal (financial, merchandise, travel, etc) have been utilized for some time as

of Marketing. Vol 21, No 9, 1987, pp 1O- a means of motivating individuals to achieve and sustain exceptional

20; B. Hastings, J. Kiely and T. Watkins,

‘Sales force motivation using travel incen- levels of performance - and to recognize and reward such effort. Several

tives’, Journal of Personal Sellinq and studies undertaken within the UK have examined the effectiveness of

Sales Management, Vol 8, No 2. 1988, pp travel as a motivational tool for salesforce personnel and/or dealer

43-51: H.P. Schickhoff. ‘An lnvestiaation

into the UK Motivation Business and its networks.’ Research from these studies has focused upon either the

Provision of Specialised Incentive Prog- users (both purchasers and recipients) or providers of incentive travel.

rammes to Stimulate the Performance of a Hastings et al surveyed the participants in an incentive programme

Salesforce’, unpublished BA (Hons) Busi-

ness Studies dissertation, Leeds and sought information on matters such as their perceptions of different

Polytechnic, 1984; J. Westwood, ‘The In- kinds of incentives and their willingness to increase their sales level in

centive Travel Market in the UK: Potential order to qualify for various incentives.* Over 2000 questionnaires were

for Marketing Australia’, unpublished MSc

dissertation, Umversity of Surrey, 1985. sent to all sales associates employed by ;I major life insurance company,

‘Hastings et al, op tit, Ref 1, and a response rate of 54% was obtained. Different incentives were

0261-5177/92/030275-l 3 0 1992 Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd 275

[tlcenrive rravel: overview and case study of Canada as a deslinariorl fm- tile UK tuarkef

evaluated by respondents as either a major incentive, a minor incentive

or no (real) incentive. The survey demonstrated clearly the attraction of

travel-this is classified as a major incentive by the highest proportion of

tespondents. Lower ranked incentives included household goods, busi-

ness goods, retail vouchers and recognition certificates. Not surprising-

ly, respondents indicated that they would be willing to increase their

sales achievements in order to qualify for incentive rewards:

The rank order of the intended sales percentage increases for the incentives was

practically identical to the rank order given for the extent to which each of the

incentives was considered to be a major incentive. [Hence travel [was]

the [incentive] for which respondents expressed the most willingness to increase

their sales achievements?

The above ranking is supported by incentive experts who regard travel

as more attractive and effective than other types of incentives because of

the exclusive and unique experiences which money alone cannot buy, ie

creating events or activities which are exceptional for a group but could

neither be purchased nor made available to an individual traveller.

These may include staged events, treasure hunts, costume parties and

gala evenings ‘themed’ to the venue.

Definitions of incentive travel

Incentive travel is one of the three major segments of business-related

travel. Mill and Morrison describe the incentive travel segment as a

‘hybrid’ because it is ‘a type of pleasure travel that has been financed for

business reasons. Thus, the persons on incentive trips are pleasure

travelers and the purchasers are businesses.”

A user company which engages in an incentive travel programme

views it as both a motivational and management tool. Some definitions

focus on the former aspect while others concentrate on the latter. For

example, Wason cites a definition which incorporates the motivational

aspect of incentive travel when he quotes Irzcetltive Travel World

Magazine:

Incentive travel . uses the promise, fulfilment and memory of an exceptional

travel related experience to motivate participating individuals to attain excep-

tional levels of achievement in their places of work or education.’

An alternative definition of incentive travel which lays more stress on

the management aspects of incentives is provided by Westwood, who

defines incentive travel as ‘offering the reward of a visit to a highly

desirable destination in return for meeting clearly defined and attain-

able objectives within a fixed programme period’.”

Reasons for incentive travel

Businesses may engage in incentive travel for a variety of reasons:

‘/bid, pp 47-48. 0 to attain business objectives through individual and/or group

‘See R.C. Mill and A.M. Morrison, The targets;

Tourism System: An Introductory Texf,

Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1985, 0 to facilitate communications and ‘networking’ opportunities, parti-

0 100. cularlv , with comoanv

I , executives:

%ee p 68 of G. Wason, ‘The incentive 0 to foster corporate culture and social interaction;

travel market in Europe’, Travel and Tour-

ism Analyst, Vol 3. 1990, pp 6578. 0 to generate enthusiasm for the following business period;

‘Westwood, op tit, Ref 1, p 24. l to foster loyalty to the company.

276 TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992

incentive travel: overview and case sludy of Canada us u destination for rhe UK marker

Each of these points is now elaborated upon.

Business objectives

The Society of Incentive Travel Executives (SITE) lists over 10 business

objectives,7 but corporations usually have one or more of the following

in mind when purchasing incentive trips:

0 increasing overall sales volumes;

0 increasing sales of specific product(s);

0 increasing sales of a high-profit product;

l reducing high inventory;

0 introducing new product(s);

0 balancing seasonal sales variations;

0 gaining new accounts/reactivating ‘old’ customers;

0 decreasing credit exposure;

0 obtaining more store displays and supporting consumer promotions.

Companies should, of course, allocate most of the incentive money that

is available to the most important objective(s) to be achieved. ‘Allocat-

ing rewards in this way is simply a form of “weighting”, but it does have

important implications for directing selling effort towards those targets

that are considered to be in the best interests of the organisation.‘”

In general, companies establish individual or group targets at diffe-

rent levels in order that each sales representative, dealer/distributor or

employee has a realistic chance of meeting and, hopefully. exceeding

his/her target. It is important that these targets are discussed and agreed

with the participants in order to ensure clear understanding and

commitment. Each level has its own reward; for esample, a weekend

break in London, four days in Paris, or 10 days in the Orient.

Communications and ‘networking’ opportunities

An incentive trip can facilitate meaningful communications among the

participants themselves and, particularly, with management. ‘It should

. . signal the beginning of an intense phase of communications - a

special phase during which management acknowledges the importance

of each individual’s contributions and reinforces the value of sustained,

superior performance.‘” It is also an opportune time for management to

seek new ideas and marketing intelligence from its top performers.

Corporate and social interaction

Incentive programmes designed for sales representatives, dealers or

distributors bring together people who have been working independent-

ly throughout the previous business period. An incentive trip offers

‘Society of Incentive Travel Executives, excellent opportunities to convey a sense of ‘belonging’ to the corpora-

‘Incentive travel in the USA’, Travel and tion and encourages team spirit and camaraderie.

Tourism Analyst, September 1986, pp 26

36.

%ee G. Holmes and N. Smith, Sales Force Generating enthusiasm

Incentives, Heinemann, Oxford, 1987, p

60. An incentive trip must not only be viewed in terms of the positive

%ee R. Graham, ‘Reinforcing the import- feedback it provides to the participants, but also ‘what it achieves in the

ance of achievement continuing com-

way of fresh enthusiasm and new business generated during the

munication with winners and qualifiers’,

INSITE, Vol 2, No 5, 1989, pp 2C-23 and following months.“’ It is an excellent moment to announce or reinforce

32-33. business objectives and also to inspire and excite the top performers.

“‘See p 40 of M. Murray, ‘Incentive travel:

Conference Britain,

Thus, an incentive trip can be as much a vehicle for ‘feedforward’ as for

making it pay’,

January/February 1989, pp 40-41. ‘feedback’ to the participants.

TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992 277

incemive travel: overview and case study of Cunada as a desiinatiorr for the UK marker

Fostering loyalty to the conzparzy

Table 1. US industry expenditure on incentive

travel in 1985. Hampton notes that:”

Industry Expenditure

(US$, millions)

It is generally upheld in the motivation industry that only the top 10 per cent of a

Insurance 2i5.0 company’s salesforce will work to their full potential and that the lowest IO per

Electronics, radio, television 152.0 cent will barely reach a satisfactory level. incentive travel is aimed at the

Automobile Darts 147.2

Cars and tricks 134.7 remaining 80 per cent producing average results, and whose performance is

Farm equipment 94.8 likely to improve, providing that they perceive the reward as valuable.

Heating and arr conditioning 90.7

Office equipment 71.6 However, incentives are also necessary to retain key sales representa-

Electrlcial appliances 56.7

Buildtng materials 46.6 tives (the top 10%) within the company; incentive travel can counteract

Toiletries 46.3 ‘head-hunting’ by competitors.

Fostering loyalty to the company also extends to the dealer network,

but manifests itself differently. Manufacturers which offer the ‘best’ trip

as perceived by the participating dealers are likely to experience

increased business. Some incentive experts believe that within certain

sectors of industry a company’s market share will vary according to the

trip offered.

Users of incentive travel

A study undertaken by SITE in the USA indicates that incentive travel

is used by virtually every major industry, but just a few of these

industries account for most of the market in terms of value. Expenditure

on incentive travel in 19X5, ranked in order of industry importance to

the market, is given in Table 1. It can be seen that the insurance industry

is by far the largest user of incentive travel, but electronics/radio/

television, automobile parts, and cars and trucks art‘ also very important

users.

In the UK the pattern of user-ship differs only slightly. Automobile

manufacturers and motor support sectors (tyres and parts) are the

principal users of incentive travel. The leading UK car makers spend as

much as $1.5 billion or more a year on programmes for their sales forces

and huge dealer networks (Ford, for example, has approximately 1200

UK dealers and Rover has 1400). Other major user indllsrries/se~tors

are: computer and office equipment manufacturers, insurance com-

panies, food and drinks manufacturers (particularly breweries), off-

highway equipment manufacturers, building materials firms (eg double-

glazing) and pharmaceutical industries.

Incentive travel programmes arc still primarily targeted to marketing

and sales ~~~lnagernent. Wowever, there has been a noticeable move-

ment towards companies involving non-sales persons in incentive travel

schemes; these schemes usually involve attainment of the corporate

objectives Of Cost reductions and efficiency iniproven1ents.l~ It is

expected that within a few years the ratio of sales to non-sales

programmes in the UK will narrow to nearer 50:50.

Potential of the UK incentive travel market

In attempting to ascertain the potential of the UK-generated incentive

travel market, a host of obstacles is encountered. First, although

“Hampton, up cif, Ref 1, p 14. statistics on UK residents cravefling abroad are grouped according to

“See R. Cfeverdon and K. O’Brien, Inter- purpose of visit, incentive travel is not one of the categories; further-

national Business Travel 1988. Special

Report No. 7 740, Economist Intelligence

more, the Department of Employment cannot verify whether incentive

Unit, London, 1988. travel is captured under ho&day or business travel. Second, in 1954 the

278 TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992

Incentive travel: overview md case study of Cunada as a destination for the UK mar&t

British Tourist Authority (BTA) commissioned its last study of the UK

conference and incentive market. Since then, budget cuts and a new

corporate policy have put an end to these government issued reports.

Third, owing to the competitive nature of some firms using this reward

system, certain companies are reluctant to disclose the nature of their

programmes or the amounts spent. Finally, employees rewarded with

incentive travel are heavily taxed on their prize (up to 40% depending

on the employee’s salary level). In some cases, companies absorb

employees’ tax costs. It is even more difficult, therefore, to put an

accurate value on the industry because firms may either include or

exclude tax rebates to winners.

Since 1984 several studies have been conducted to determine the

potential of the UK incentive travel market. The most significant and

comprehensive one to date was carried out by Westwood, wherein

incentive travel organizers and companies which were potential users of

incentive travel were surveyed.‘3 A response rate of 36% was obtained

for the former survey and 22% for the latter. Based on the data

collected from the incentive travel organizers’ survey, Westwood was

able to provide a ‘glimpse ;It the overall value of the market .

Calculations from the data showed it to be in the vicinity of El47 million

in 1984. This information is based on the turnover of [incentive travel]

organisers only and a base of 105 firms.“’ It was not possible to draw

any conclusions for total incentive travel expenditure from the company

survey as some companies included expenditure on all incentives (ie,

merchandise and travel).

lncerltive Travel World Magazine also undertook a survey of incentive

travel organizers (in 1956), but obtained a response rate of only 90/o.”

The value of the UK incentive travel market was determined to be in the

region of f12&150 million, which is in line with the Westwood estimate

of f147 million.

A further survey was carried out by Incentive Travel World Magazine

in 1989, and this time they obtained a much higher response rate

(77%).lh The 36 respondent companies operated 1332 incentive travel

movements and carried 98 055 participants. The average group size was

‘3Westwood, op cit. Ref 1.

74 people and the average amount spent per person was f735. Most of

‘%id, p 95. these companies reported substantial growth over their 19S8 figures.

‘51nformation obtained from untitled article Although classified as group travel, incentive trips are considered to

by S. Bryant in incentive Travel World

Magazine, August 1989.

be at the ‘upper’ end of this market. It is not unusual for a company to

“Whereas in 1984 Westwood was ham- finance an incentive trip for a group of 50 to 100 winners at, say, f1200

pered in her research by the lack of an per person to a long-haul destination. Incentive travel is therefore

industry coordinating body for incentive

travel in the UK. bv 1989 Incentive Travel

regarded as a highly lucrative market.

World Magazine determined that the num-

ber of companies operating in the industry

was about 200: 44 members of the Incen- Research objectives and methodology

tive Travel Association of the United King-

dom (ITA:UK), 60 members of the UK The objectives of the survey research included:

chapter of the American-based SITE and

about 100 other companies which either 0 ascertaining product benefits and features associated with incentive

promote themselves as incentive houses travel;

or are in-house travel departments of large

companies, public relations organizations 0 identifying Canada’s strengths and weaknesses as an incentive travel

or sales promotion companies, or are high destination from the perspective of the UK market;

street travel agents who book travel incen- 0 evaluating some of the current promotional material for Canada

tives. Thus, there appears to have been a

100% growth in the number of incentive

and identifying areas for improvement.

companies operating in the UK, from the

105 Westwood estimated to be active in

Qualitative marketing research was undertaken in the form of semi-

1984 to over 200 in 1989. structured, in-depth interviews with UK incentive travel organizers. The

TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992 279

Incentive travel: overview and case study of Canada as a destination for the UK market

participants were drawn from the Incentive Travel Association of the

United Kingdom (ITA:UK) - a readily identifiable group purposely

selected to form a discriminating sample. Most of the 1TA:UK members

were located in the London/Southeast catchment area, and, of these, 14

executives agreed to be interviewed.

In analysing the responses of the incentive travel organizers, common

themes or patterns emerged, and these are discussed in the next two

sections.

Evaluation of Canada as an incentive travel destination

The incentive travel product may be analysed in terms of attractions,

facilities and accessibility. (These criteria are used to evaluate tourism

products in general because of their composite nature.) Burkart and

Medlik define attractions as:

those elements in the tourist product which determine the choice of the tourist

to visit one destination rather than another. They are factors which generated a

flow of tourists to their location.”

Tourist futilities, on the other hand, are:

those elements which do not normally themselves generate tourist flows but

whose absence might deter the tourist from seeking the attractions. The facilities

complement the attractions They are basically utilitarian, even though they

contribute significantly to the tourist’s enjoyment.‘”

Lastly, accessibility can be interpreted in terms of:

0 mode of transport available both to and within a destination;

0 the travelling time required;

0 the cost of travel;

0 the combination of comfort, speed and reliability.

It is generally believed that a destination is considered suitable for the

incentive travel market when it is in the mature stage of the tourism

product life cycle. This means that the destination should possess a

sufficient number and mix of attractions, its infrastructure should be

highly developed and it should have good accessibility. Other important

factors include adaptability to a variety of audiences, image, competi-

tive pricing and favourable currency exchange rates.

Table 2 analyses Canada according to the criteria deemed essential

for a successful incentive travel destination, and those of a generic

tourism product. The table incorporates information both from the

literature review and from the interviews with incentive travel organiz-

ers.

Table 2 shows that Canada has both strengths and weaknesses as an

incentive travel destination. Canada’s sophisticated city products, ex-

ceedingly good outdoor life and variety of sporting activities lend

themselves to the incentive travel market. According to the respon-

dents, this combination allows for a variety of styles in designing an

incentive programme, wherein, for example, a contrast between city

and resort experiences can be offered.

The most common theme to emerge from the interviews was Cana-

da’s potentiul as an incentive destination, especially in view of new

17See A.J. Burkart and S. Medlik, Tourism: trends which have emerged during the past few years. One is the move

Pasf, Present and Future, Heinemann,

London, 1981, p 195. away from the beach holiday in favour of a more sophisticated incentive

“Ibid, p 195. experience, driwing out the extruordirury elements of a destination, ie

TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992

Incentive travel: overview and case study of Canada as a destination for the UK market

Table 2. Product analysis of Canada as an incentive travel destination.

Incentive

Tourism travel

product product Canada

Attractions Historical sites Several ‘colonial’ historical sites. but too far apart. Few

places of historical or cultural significance.

Scenery Outstanding scenery Clean environment but lack of

beaches (as in sun, sand and sea holidays).

Unique cultural appeal Multicultural (European-type influences). Yet Canadian cul-

ture is perceived as being similar to US culture.

Entertainment/nightlife/ Canada is perceived to be boring and lacking in excitmg

cuisine nightlife.

Variety of sights and Wide variety of winter and water sports/activities offered -

activities an increasingly important aspect of an Incentive trip

programme.

Climate Not reltable. especially in the spring and autumn (peak

periods for incentive travel).

Facilities Quality hotels and World-class hotels available in major centres and resort

fleeting facilities areas, yet there is a perception of too little concern for inter-

national standards of quality.

Good local destination Good DMCs available but not well known to incentive

management comp- spectalists in the UK.

anies (DMCs)

Accessibiilty Available transport to Good accessibility. AIrlInes becoming more flexible.

and within the

destination

Value for money Perceived to be expensive to travel to and within Canada.

Reasonable travel time Canada is considered a medium- (east coasVcentral region)

to long-haul (west coast) destination from the UK.

Several points of de- important aspect as many firms do not wish all their top

parture from the UK sales representatives/dealers to travel on the same aero-

plane.

Other Promotability and im- Posltlve image of Canada as a nation-weaker image as a

age development holiday desttnation. Lack of public awareness. Perceptjon

of Canada as dull and bonng - not a motivating or emotive

image for an incentive destination.

Favourable currency Yes. However, there is the perception that the Canadtan

exchange rates dollar is at par with the American dollar.

Adaptability to a variety Yes. Different venues and theme evenings are available

of audiences. (eg Klondike days). Yet more creative and imaginative

events required.

Safety Canada perceived as a safe holiday destination-becoming

increasingly important.

those unusual or unique factors that are characteristic of the

destination. l9 Another trend is the emphasis upon active rather than

passive involvement by the participants in an incentive programme.

Participation in activities, sports and events has increased for two

reasons: first, such exercises are enjoyed more by ‘winners’; and

second, they develop team building skills. Finally, there is an increasing

demand for incentive programmes which are both tailored to the clients’

needs and which create a unique experience for the participants. As the

salaries of likely incentive programme participants are high, developing

exclusive travel experiences which money alone cannot buy has become

necessary.

From the travel organizers’ point of view, Canada promises many

incentive opportunities. However, convincing the client and participants

of this is very difficult because of their low awareness of Canada and its

predominant image as a destination for VFR tourism. One respondent

elaborated upon this point as follows:

Places which excel in the incentive travel world are those which already have an

established image with holidaymakers. America. for example, has a massive

amount of promotion for Florida and you’ll find lots of incentives going to

“See M. Harding, ‘Making the break - Florida, in the same way as you have lots of holidaymakers going to Florida.

how far do you go?‘, Marketing Week, Vol

12, No 28, 1989, pp 63-64, 66 and 68. He further explained:

TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992 281

Incerlrive travel: overview and case slud~ of Cunada as a drsrinarion for rhe UK marker

USA 46%

127%

Canada

Far East/Asia

26%

Australia/New Zealand -12%

122%

Central/South Africa

West Indies/Caribbean

Central/South America m Most recent trips

Figure 1. Current and preferred over-

0 Most preferred destination

seas travel destinations for the UK Mexico

Travel Market. I I I I

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Source: Market Facts of Canada, op tit,

Ref 20. % of trips

As far as Canada is concerned, leisure travel between the United Kingdom and

Canada has historically consisted largely of people visiting friends and relations,

rather than going on package holidays. There have been a certain amount of

fly-drive holidays, but there has WI been a promotion of Canada as a holiday -

an inclusive holiday - destination in the same way that there has been of the

United States. Until Canada becomes more of ;I package destination, if you like,

I don’t think that’s going to change a great deal.

In jointly-funded travel market research conducted for Tourism Canada

and the United States Travel and Tourism Administration, Market

Facts of Canada noted significant changes in the UK outbound holiday

market during the period 198&89.“’ These include the following:

l a strong growth in actual and intended long-haul vacation travel

with the size of the target market essentially doubling;

0 the USA increasing its share of long-haul vacation trips from 40% to

4X%, with Canada’s share remaining constant at 16%;

0 the number of times the USA was mentioned as a most preferred

destination increasing from 21% to 27(X,, with, again, Canada

remaining steady at 10%.

Trends in the UK outbound holiday market also indicate a growing

preference for long-haul travel to the Far East/Asia and Australia/New

Zealand in addition to the USA, as indicated in Figure 1.

How strongly trends in the British pleasure travel market indicate

likely trends in the UK incentive travel market is difficult to measure.

Many of the incentive specialists interviewed believe that until the

British public becomes more interested and aware of Canada as a

holiday destination, the country will continue to be a ‘hard sell’ as an

incentive travel destination. As one travel organizer commented, ‘Cana-

da is just not one of the destinations that [participants] think of as being

at the top of their list; so they’re not likely to either ask for it or be that

“See Market Facts of Canada, Pleasure excited if we put it forward’.

Travel Markets to North America: United

Kingdom, France, West Germany, Japan

(7989 Highlights Report), published under The irmge issue

the authority of the Department of Industry,

It follows that Canada needs to project its image more and improve its

Science and Technology Canada, Ottawa,

1989. promotion in order to put the ‘dream’ into the incentive winner’s mind

282 TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992

Incenlive travel: overview and case study of Cunada as a destinatiorz for the IJK marker

initially. As indicated by the survey responses, Canada often loses out to

a destination that has a stronger, more clearly-defined image. The

competition may not have as good an incentive product, but because it

has the ‘right’ image it will be selected by the client.

Ashworth and Goodall refer to this type of situation as a mismatch

between demand and supply images:

Naive (demand) images represent tourists’ perceptions of whether destinations

contain the holiday attributes that they consider necessary for a successful

holiday. these images [can be] compared with whether or not the destination

actually contains those attributes (which a factually accurate supply image would

reveal).”

One of four situations may exist:

0 positive demand and supply images;

0 positive supply image but negative demand image;

0 positive demand image but negative supply image;

0 negative demand and supply images.

From the respondents’ point of view, Canada as an incentive travel

destination appears to fall within the second category. The discfepancy

between a positive supply image and a negative demand image leads to

potential participants rejecting such a destination on account of the low

evaluative image. ‘The destination area therefore needs to improve both

the targeting and the nature of its promotional image.“*

Similar to other types of travel products, incentive destinations may

easily become substitutes for one another unless imbued with distinctive

benefits or unique selling points (USPS). It is not a simple task either to

develop or to promote them. As Holloway and Plant explain, ‘If the

product is not really new - if it is only an attempt to emulate existing

products on the market, offering no appreciable advantages over what is

currently available - it stands a poor chance of success.“’ Canada’s

greatest competitor in this respect is, of course, the USA.

Competition

USA. Canada is often assumed by the British to be similar to the USA,

not only because of the geographical proximity but also because of its

economic and cultural domination by the USA. Hence it is not

surprising that during the in-depth interviews with UK incentive orga-

nizers, the USA was often referred to as a point of comparison when

discussing Canada. When asked why people perceive Canada to be

similar to the USA, the following responses kept recurring:

a Both countries are ‘English-speaking’ with similar accents.

a Both countries make up the North American continent with a land

border as opposed to a water border separating them. (From the

UK perspective, a land border is not as definitive.) Both Canada

and the USA are vast countries with similar topography.

“See G. Ashworth and B. Goodall, ‘Tour- a Modern architecture and skyscrapers characterize both American

ist images: marketing considerations’, in B. and Canadian cities.

Goodall and G. Ashworth, eds, Marketing . The basic culture seems to be the same in both countries - for

in the Tourism Industry: The Promotion of

Destination Regions, Routledge, London, example, common sports prevail, such as baseball and (American)

1988, p 232. football.

*‘Ibid, p 232. l Both countries have dollar currencies.

‘%ee J.C. Holloway and R.V. Plant, .

Marketing for Tourism, Pitman, London, Both countries are of the same age and perceived to have a similar

1988, p i32 history.

TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992 283

Incentive travel: overview and case study of Canada as a desrinution for lhe UK marker

Such strong similarities between the two countries give rise to a rather

uniform image from the perspective of the UK market.

Certain advantages can be gained, however. from Canada’s proximity

to the USA. Experience suggests that it is easier to sell Canada as an

add-on to an incentive trip to the USA. Incentive organizers have

discovered that although participants do not look forward to visiting

Canada as much as the USA. after experiencing both destinations, they

tend to express a preference for the former. Therefore, initially, it may

be necessary to ‘bait’ the client with the USA in order to market Canada

as an incentive travel destination. Once the group has experienced

Canada, it may be possible to follow-up with future trips solely to this

destination.

Europe. New opportunities in Eastern Europe and increased competi-

tion thanks to the creation of the Single European Market in 1992 are

predicted. Regarding the former, the countries of Eastern Europe will

need time to adapt and improve their outdated infrastructure and poor

ground handling arrangements before becoming a major competitor for

incentive travel movements.24 Concerning the latter, the Canadian

Tourism Research Institute forecasts that long-haul travel will experi-

ence fast growth, owing to the improved economic climate expected

from a united Europe after 1992.‘5

Promotion of an incentive travel destination

Promoting a destination will, of course, be influenced by the level of

overseas representation of a tourist organization. This varies consider-

ably in accordance with the resources of the country, the nature of its

competitors’ activities and the characteristics of the product it

promotes.2h

Similar to private enterprise, the aim of tourist organizations is

primarily to increase market share. However, unlike the commercial

sector, the role of an NT0 is viewed more as ‘facilitator’ than ‘seller’.”

The marketing effort of an official tourist organization is one of

influence and persuasion rather than control - a very different perspec-

tive from that used to explain commercial practice.‘”

Ashworth and Goodall point out that, ‘In practice, much official

?See Wason. op tit, Ref 5. (destination area> tourism promotion is “defensive”; that is, endeavour-

‘%anadian Tourism Research Institute, ing to correct or counter-balance images obtained elsewhere.“” When a

The Impact of a Frontier Free Europe on destination such as Canada has an image problem, the tourist office

Canada’s Tourism Industry, published

under the authority of the Department of must decide whether to maintain the traditional image, slightly modify it

Industry, Sctence and Technology Cana- or dramatically change it. The dilemma, therefore, is whether to project

tziettawa, October 1989. the simple, recognizable and expected image based on well-known

Economist Intelligence Unit,

‘National tourist offices: the role and func- symbols (eg moose, moutains and mounties), or to convey potentially

tion of an NT0 abroad’, lnfernational Tour- less acceptable and more complex images which indicate a more varied

ism Quarterly, No 2, 1983, pp 48-61. tourist destination. On the one hand, ‘the image built up of a destination

270p tit, Fief 17.

“See V.T.C. Middleton, Marketing in in a market takes years to achieve.‘3” Yet, on the other hand, rather

Travel and Tourism, Heinemann, Oxford, than reinforcing existing patterns, should not the present-day Canadian

1988. ways of thinking and a more multicultural image be used as ‘an

290p tit, Ref 21, p 222.

3oSee p 1 of J. Bonnett, ‘Overseas promo- instrument for encouraging the tourism industry in new directions’?j’

tion by national tounst offices’, Proceed- Another controversy surrounding the image of a destination is

ings of Tourism - Managing for Results whether the official tourist image should prevail over the image held by

Seminar, University of Surrey, 1989, pp

1-4. the tourist or some third party company. Dilley argues that -the success

3’Op tit, Ref 21, p 222. of any image is something that only the relevant tourist authority can

284 TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992

Incentive travel: overview and case sludy of Canada as a desrirlarion fir rhe I/K market

decide, as only the country producing the brochures and projecting the

image knows what it wants from it’.” Nevertheless, it is recognized that

the official image is not the most important source of ideas about a

tourist destination held by the potential visitor. The latter’s image of a

destination is influenced and shaped more by the news media, personal

experience and personal contacts than by the publicity emanating from

the tourist destination itself.

Embacher points out that, ‘The promotion of a country’s tourism

image is generally a matter not of creating an image from nothing but of

transforming an existing image’.33 He further states:

[The aim of the promotional effort should be] to transform negative and

indifferent attitudes into positive ones and consequently to convert positive

reactions into a dynamic attitude in order to provoke action The marketers

should develop a picture of the desired image which may even be in contrast

to the current image. The desired image must be feasible in terms of the

country’s present reality and resources and must also be relevant to the

target group at which the promotional campaign will be addressed.”

The gradual transformation of Canada’s traditional image into a more

cosmopolitan one is reflected through television advertising of recent

years and promotional print. In advertising targeted to the UK plenslwe

tmveller, beautiful scenery, art and culture, outdoor’activities, shop-

ping, dining and colonial historical sites have been included. One major

theme which has been communicated is that of Canada as a destination

which offers variery or ‘a world of possibilities’. This has been under-

taken with a view to increasing awareness. In the incentive travel

market, it is in the areas of quality promotional videos and print, and

public relations, that a tourist organization can excel in marketing a

destination.

Promotioruzl videos and print

The survey respondents strongly recommend that videos be produced

by tourism offices to support their ‘sales pitch’ to the client and to

convey a ‘feel’ for the destination. Videos are emotive. Since Canada is a

vast country, it was thought that each region should be presented on a

separate video and with sufficient detail. If this is not possible, an

incentive video for Canada wou!d suffice - containing a few minutes on

each region - but care would need to be taken to ensure it was not too

wide-ranging. In cases where clients do not have video equipment in

their office or home, a good slide presentation is required.

However, there is still strong reliance upon promotional print as a

tangible representation of the destination. Brochures perform a product

substitute role, particularly during the period between purchase and

consumption. A brochure ‘establishes expectations of quality, value for

money, product image and status’.” It also becomes a document to be

32See p 64 of R. Dilley, ‘Tourist brochures viewed several times to stimulate expectations of the forthcoming trip.

and tourist images’, The Canadian Geog-

rapher, Vol 30, No 1, 1986, pp 59-65. Public relations

33J, Embacher, Austria’s image as a Sum-

mer Holiday Destination, unpublished MSC ‘Personal communications channels derive their effectiveness through

dissertation, University of Surrey, 1986, p the opportunities for individualising the presentation and feedback.‘36

11.

In general, personal influence and communications carry the greatest

?bid, p 15.

350~ cit. Ref 28, II 178. weight where the product is expensive, risky or purchased infrequently

‘%be p. Kotler, ‘Marketing Management: and where the product has a significant social status. Nowhere in

Analysis, Planning, Implementation and

tourism is this likely to be more applicable than in the incentive travel

Control, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs,

NJ, 1988, p 601. market, where companies finance trips at vast expense in order that

TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992 285

Incentive travel: overview and case study of Canada as a destination for the UK market

participants may be made to feel that they have won something unique

and valuable.

Within the UK incentive travel market, a great deal of emphasis is

placed upon ‘networking’. Public relations can contribute strongly to

increasing awareness and stimulating interest in a destination, influenc-

ing the incentive trade and building the corporate image in a way that

reflects favourably on the product.

Although public relations has become a vital aspect of the com-

munications strategy for the UK incentive travel market, it is unlikely to

stimulate a noticeable increase in attracting incentive groups to Canada

unless at the same time a vigorous advertising campaign is initiated. In

order to heighten awareness of the country and to increase its share of

the UK pleasure travel market and, hence, the incentive travel market,

promotion in the form of advertising may be the only way forward.

Conclusion

Canada offers great potential as an incentive travel destination. Incen-

tive travel organizers consider the destination to possess strong selling

points in terms of scenery, culture, infrastructure, modern conveni-

ences, possible programme variety, facilities for sports activities (rang-

ing from ‘easy’ to ‘strenuous’) and personal safety. Furthermore,

opportunities exist for creating two-centre programmes; this may take

the form of, say, combining a city and resort experience, two cultural

experiences (English/French), or two countries - Canada and the USA

(eg Boston/Quebec City-Montreal; Seattle/Vancouver-Whistler; New

York/Toronto). However, both Canada’s image and its tourism product

benefits need to be clearly defined and projected; otherwise, Canada as

an incentive travel destination will continue to be easily substituted by

other destinations and remain a ‘hard sell’.

Canada competes with other long-haul destinations - in particular,

the USA, the Far East and Australia/New Zealand. Awareness of and

interest in these latter countries has certainly increased in recent years,

with the result that there has been a considerable increase in the volume

of UK holiday (particularly inclusive tour) travel to these destinations.

According to the incentive executives interviewed, a growing interest in

these countries has also been expressed by the UK incentive travel

market. This lends support to the argument that an incentive travel

destination will become successful once the country is an established

(inclusive tour) holiday destination.

Although the UK incentive travel market appears to be lucrative,

increased competition, the demand for a quality product and the

requirement for a sophisticated promotional campaign means that

tourist offices need to be particularly astute in targeting this market

segment. Incentive travel is both a ‘people’ and an ‘idea’ business. Thus,

effective public relations and professional, exciting, promotional print

and support material, videos and slide presentations are essential

requirements in a communications programme for the incentive travel

market.

The number of VFR tourists from the UK to Canada is continuing to

fall; at the same time more British tour operators than ever before are

offering Canadian programmes. Also, interest in Canada as an incentive

travel destination has recently increased substantially, and the Canadian

High Commission in London reports a sharp rise in the number of

286 TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992

Incentive truvei: overview and case study of Canada as u ciestinarion for the UK marker

incentive trips being held in Canada. The outlook for Canada as an

incentive travel destination thus appears to be highly positive.

However, considerable caution needs to be exercised when predicting

future growth in the incentive travel market. The recession of the early

1990s together with the 1991 Gulf War show the extreme vulnerability

of this particular tourist segment to economic and political factors. In a

recessionary period, the first perk to be cut back is foreign travel; and

even if incentive travel is continued, there is a tendency for group sizes

to be reduced and for trip durations to be shortened. During the Gulf

War many companies cancelled international travel for their entire

workforces, but even when the war was over companies were more

reluctant than before to send their best sales forces. management and

other key personnel abroad.

TOURISM MANAGEMENT September 1992 287

You might also like

- Product Planning, Branding & Packaging - Assignment FinalDocument31 pagesProduct Planning, Branding & Packaging - Assignment FinalDgl100% (2)

- Walmart Takes On Amazon FinalDocument21 pagesWalmart Takes On Amazon FinalSandala Aditya Ramakrishna PadmavathiNo ratings yet

- Grand WanderlusterDocument36 pagesGrand WanderlustercocorocaraNo ratings yet

- Progress Report For Post Doctoral Fellowship 2016Document9 pagesProgress Report For Post Doctoral Fellowship 2016Rajesh Singh KumabamNo ratings yet

- MARKET Strategies in Different Phases of Destination Life CycleDocument22 pagesMARKET Strategies in Different Phases of Destination Life CycleJeevesh ViswambharanNo ratings yet

- Mba International Business Project ReportDocument17 pagesMba International Business Project Reportgscentury2769370% (2)

- Grab Food Food Panda RRL ADocument6 pagesGrab Food Food Panda RRL AAui Pau50% (2)

- Nike Target MarketDocument2 pagesNike Target MarketAlicia Ramai100% (3)

- Ariel Marketing MixDocument9 pagesAriel Marketing MixIann AcutinaNo ratings yet

- Creating A Tour: Chapter ObjectivesDocument26 pagesCreating A Tour: Chapter ObjectivesDũng NguyênNo ratings yet

- Tourist Loyalty To Tour Operator Effects of PriceDocument11 pagesTourist Loyalty To Tour Operator Effects of PriceNynda RachmalinaNo ratings yet

- LR 1Document26 pagesLR 1nareshNo ratings yet

- 10 5923 J Tourism 20150403 03 PDFDocument16 pages10 5923 J Tourism 20150403 03 PDFDeckerChua0% (1)

- MM 33 40Document8 pagesMM 33 40Kishor KhatikNo ratings yet

- Promotional Competitions: A Winning Tool For Tourism MarketingDocument10 pagesPromotional Competitions: A Winning Tool For Tourism MarketingkutukankutuNo ratings yet

- Examining The Link Between Visitors' Motivations and Convention Destination ImageDocument18 pagesExamining The Link Between Visitors' Motivations and Convention Destination ImageAbdullah MalikNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Motivations, PerDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Motivations, PerikaNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Importance of Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in The Tourism IndustryDocument15 pagesAnalyzing The Importance of Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in The Tourism IndustryhortensiasfamfestNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Demarketing in The Tourism Industry and Implications For Sustainability - IJISRT19OCT2080 PDFDocument6 pagesEvolution of Demarketing in The Tourism Industry and Implications For Sustainability - IJISRT19OCT2080 PDFAGBOOLA OLUGBENGA MAYOWANo ratings yet

- Olga Borovschi - TLH124 Marketing and Business .EditedDocument15 pagesOlga Borovschi - TLH124 Marketing and Business .Editedinfotechedge10No ratings yet

- ID Worksheets Glossary PDFDocument12 pagesID Worksheets Glossary PDFEdwin M. R. LolowangNo ratings yet

- Tourism MarketingDocument43 pagesTourism MarketingAdarsh Jain100% (1)

- Journal of Tourism Research - 1999 - Lumsdon - The Role of The Tour Operator in South America Argentina Chile ParaguayDocument11 pagesJournal of Tourism Research - 1999 - Lumsdon - The Role of The Tour Operator in South America Argentina Chile ParaguayHelen WaibaNo ratings yet

- Tuorism Word 1Document17 pagesTuorism Word 1Adarsh JainNo ratings yet

- T N T MGT PPT TwoDocument37 pagesT N T MGT PPT TwoRubylene Jane BactadanNo ratings yet

- TourismDocument28 pagesTourismtauseef00No ratings yet

- 05 Tourism Marketing and PromotionDocument40 pages05 Tourism Marketing and PromotionGolamSarwar100% (1)

- Chapter7 GroupPresentationDocument41 pagesChapter7 GroupPresentationKyi Cin ShweNo ratings yet

- TPDM Assignment 2 by Avi Thakur (19BMSR0279)Document6 pagesTPDM Assignment 2 by Avi Thakur (19BMSR0279)Avi ThakurNo ratings yet

- Perception of Sustainability of A Tourism DestinatDocument13 pagesPerception of Sustainability of A Tourism DestinatCristina LupuNo ratings yet

- Case Study Analysis of Interpid TravelDocument10 pagesCase Study Analysis of Interpid TravelNicky byrneNo ratings yet

- Branding Asian Tourist DestinationsDocument7 pagesBranding Asian Tourist DestinationsAmit AntaniNo ratings yet

- FundingFutures FullReport Final 08282020Document127 pagesFundingFutures FullReport Final 08282020Elif Nas UnalNo ratings yet

- Understanding Market Segmentation Key To Repeat Visits by Tourists'Document3 pagesUnderstanding Market Segmentation Key To Repeat Visits by Tourists'Reyhan0% (1)

- Niche TourismDocument13 pagesNiche TourismBrazil offshore jobs100% (1)

- BSBMKG501 Identify and Evaluate Marketing Opportunities - Assessment Task 1Document11 pagesBSBMKG501 Identify and Evaluate Marketing Opportunities - Assessment Task 1Venta MeylanNo ratings yet

- Course in TourismDocument27 pagesCourse in TourismMilan KoiralaNo ratings yet

- Marketing in Travel and Tourism OkDocument36 pagesMarketing in Travel and Tourism OkAncuta TabarceaNo ratings yet

- California Sustainable Tourism Marketing HandbookDocument29 pagesCalifornia Sustainable Tourism Marketing HandbookPresa Rodrigo Gómez, "La Boca"No ratings yet

- The Perceptions and Motivations That Impact Travel and Leisure of Millenial GenerationsDocument22 pagesThe Perceptions and Motivations That Impact Travel and Leisure of Millenial GenerationsMarco Ramos JacobNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Tourism Success For DMOs & Destinations - An Empirical Examination of Stakeholders' PerspectivesDocument18 pagesDeterminants of Tourism Success For DMOs & Destinations - An Empirical Examination of Stakeholders' PerspectivesMinh Tiến PhạmNo ratings yet

- Siripen Paper Push Pull Motives and Destination Choice With Cover Page v2Document7 pagesSiripen Paper Push Pull Motives and Destination Choice With Cover Page v2Dave LarteyNo ratings yet

- Task# 1: Primary and Secondary Sources To Be Used in Data CollectionDocument4 pagesTask# 1: Primary and Secondary Sources To Be Used in Data CollectionSamrah QamarNo ratings yet

- The Tour Operator Industry An Analysis: Pauline J. SheldonDocument17 pagesThe Tour Operator Industry An Analysis: Pauline J. SheldonChinmayJoshiNo ratings yet

- Assignment:SITXMPR007 Name Rajdeep Kaur Sandhu Student Id 43132Document25 pagesAssignment:SITXMPR007 Name Rajdeep Kaur Sandhu Student Id 43132Anu Saroch25% (4)

- Topic: Destination Marketing: Student Name: IdDocument10 pagesTopic: Destination Marketing: Student Name: Idmd. sharshahNo ratings yet

- Strategic Marketing Planning For The Tourism Industry Articol Turistic PDFDocument7 pagesStrategic Marketing Planning For The Tourism Industry Articol Turistic PDFNoruca SiminiceanuNo ratings yet

- 10 - Tourism PromotionDocument13 pages10 - Tourism Promotiondubeyavanish691No ratings yet

- Tourism Marketing and Consumer Behaviour: April 2015Document11 pagesTourism Marketing and Consumer Behaviour: April 2015Jesús Ismael Morales SánchezNo ratings yet

- Shaping The Future of Luxury Travel ReportDocument32 pagesShaping The Future of Luxury Travel ReportRobert Komartin100% (1)

- Travel Destinations Choice and Activities The Case of Gondar and Its EnvironsDocument6 pagesTravel Destinations Choice and Activities The Case of Gondar and Its EnvironsarcherselevatorsNo ratings yet

- Tourism MarketingDocument2 pagesTourism MarketinglaughjerkerNo ratings yet

- Tourist Loyalty in Creative Tourism: The Role of Experience Quality, Value, Satisfaction, and MotivationDocument14 pagesTourist Loyalty in Creative Tourism: The Role of Experience Quality, Value, Satisfaction, and Motivationolyvia resyanaNo ratings yet

- Script MSTM 512Document17 pagesScript MSTM 512sodelahannahshieneNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument18 pagesAbstractzyra bitaraNo ratings yet

- Tourism MarketingDocument11 pagesTourism Marketingvijay goutamNo ratings yet

- Tourism Promotion: Guinto, Angelika Aira Tamba, Raisa PrincessDocument12 pagesTourism Promotion: Guinto, Angelika Aira Tamba, Raisa PrincessAira GuintoNo ratings yet

- Unit 20 Trade Fairs Festivals: StructureDocument8 pagesUnit 20 Trade Fairs Festivals: StructureRahul SinghNo ratings yet

- Market Strategies in Opening Phase, Growing Phase and Declining Phase. Identification of Attractive Market SegmentsDocument19 pagesMarket Strategies in Opening Phase, Growing Phase and Declining Phase. Identification of Attractive Market SegmentsJeevesh ViswambharanNo ratings yet

- Gitanjali More 028 Rucha Puntambekar 195Document25 pagesGitanjali More 028 Rucha Puntambekar 195abhishek kunalNo ratings yet

- Kozak, M. - Measuring Tourist Satisfaction With Multiple Destination AttributesDocument12 pagesKozak, M. - Measuring Tourist Satisfaction With Multiple Destination AttributesAli KhavariNo ratings yet

- TS311 Unit 10 PDFDocument31 pagesTS311 Unit 10 PDFVictoria MaraginNo ratings yet

- Middle Market M & A: Handbook for Investment Banking and Business ConsultingFrom EverandMiddle Market M & A: Handbook for Investment Banking and Business ConsultingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Creating Experience Value in TourismFrom EverandCreating Experience Value in TourismNina K PrebensenNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Destination Branding and Marketing: Strategies for Tourism DevelopmentFrom EverandSustainable Destination Branding and Marketing: Strategies for Tourism DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Fleischeretal 2013 FestivalisationDocument25 pagesFleischeretal 2013 FestivalisationNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

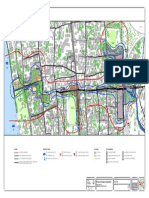

- Entekochi Design Competition: Stretch A.1Document1 pageEntekochi Design Competition: Stretch A.1NEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Entekochi Design Competition: Transport Nodes Legend Site/ LandmarkDocument1 pageEntekochi Design Competition: Transport Nodes Legend Site/ LandmarkNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Assignment TOPIC:Tourism and Resort Architecture in Kerala With Case Studies. Name:Nefsya Kamal Roll No:23Document7 pagesAssignment TOPIC:Tourism and Resort Architecture in Kerala With Case Studies. Name:Nefsya Kamal Roll No:23NEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Entekochi Design Competition: Transport Nodes Site/ Landmarks Sub Zones LegendDocument1 pageEntekochi Design Competition: Transport Nodes Site/ Landmarks Sub Zones LegendNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Key Plan: Entekochi Design CompetitionDocument1 pageKey Plan: Entekochi Design CompetitionNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Morphological Analysis of A Historical Urban Landscape: The Case of Greater Gwalior City, Madhya PradeshDocument4 pagesMorphological Analysis of A Historical Urban Landscape: The Case of Greater Gwalior City, Madhya PradeshNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Disaster ManagmentDocument21 pagesDisaster ManagmentNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Architectural Conservation: AssignmentDocument11 pagesArchitectural Conservation: AssignmentNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Trauma Rehabiltation Center For Medical Tourism: Synopsis ofDocument17 pagesTrauma Rehabiltation Center For Medical Tourism: Synopsis ofNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- The Gomti Riverfront in Lucknow, India: Revitalization of A Cultural Heritage LandscapeDocument20 pagesThe Gomti Riverfront in Lucknow, India: Revitalization of A Cultural Heritage LandscapeNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- CRZ Port Blair FortuneDocument19 pagesCRZ Port Blair FortuneNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Jewish CemetryDocument17 pagesJewish CemetryNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- UDC - Kochi - Section 2Document15 pagesUDC - Kochi - Section 2NEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Thesis Synopsis 2Document10 pagesThesis Synopsis 2NEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Main Pergola PDFDocument1 pageMain Pergola PDFNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- 5622-Article Text-12603-1-10-20180921Document12 pages5622-Article Text-12603-1-10-20180921NEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- RFD PDFDocument454 pagesRFD PDFNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Bay Island HotelDocument2 pagesBay Island HotelNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Nefsya Kamal FinalDocument102 pagesDissertation Nefsya Kamal FinalNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- 4th AugDocument1 page4th AugNEFSYA KAMALNo ratings yet

- Employee List 05mar2022Document1,631 pagesEmployee List 05mar2022UJJINENI SAI VAMSINo ratings yet

- Case Study - Supply Chain Management JohDocument9 pagesCase Study - Supply Chain Management JohAzeem AhmadNo ratings yet

- Distributor Aggrement New TemplateDocument15 pagesDistributor Aggrement New TemplatePrachi RajputNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 DEFINING MARKETING FOR THE 21st CENTURYDocument12 pagesTopic 1 DEFINING MARKETING FOR THE 21st CENTURYSharrymae Tumanguil MatoteNo ratings yet

- Functional Level Strategies: Learning OutcomesDocument46 pagesFunctional Level Strategies: Learning OutcomesAKSHAY PATERIYANo ratings yet

- 03 7 Eleven AnswersDocument8 pages03 7 Eleven AnswersAb Id Khan100% (1)

- Group Member: Adi Supriadi Muhammad Rizki Ovan Maulana Doni Ramadhan Yoga AnggraenaDocument13 pagesGroup Member: Adi Supriadi Muhammad Rizki Ovan Maulana Doni Ramadhan Yoga Anggraenavan malNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 AnsDocument47 pagesChapter 4 Ansdung03062005.9a1No ratings yet

- 5 Concept of MarketDocument19 pages5 Concept of MarketAshish GangwalNo ratings yet

- Final Term Paper On TK GroupDocument32 pagesFinal Term Paper On TK GroupSyed Salman RahmanNo ratings yet

- Package Tourism: August 2022Document4 pagesPackage Tourism: August 2022Bilal TajNo ratings yet

- Dairy Products and Alternatives in Pakistan - Analysis: Country Report - Sep 2022Document4 pagesDairy Products and Alternatives in Pakistan - Analysis: Country Report - Sep 2022Maryam DoustNo ratings yet

- L3 Fundamentals of LogisticsDocument40 pagesL3 Fundamentals of LogisticsDu Lich Vung TauNo ratings yet

- Statement of Axis Account No:920010006130934 For The Period (From: 01-04-2021 To: 31-03-2022)Document20 pagesStatement of Axis Account No:920010006130934 For The Period (From: 01-04-2021 To: 31-03-2022)subhadeepNo ratings yet

- Amul Distribution Channel and Sales ProjectDocument100 pagesAmul Distribution Channel and Sales Projectsaswat mohanty100% (1)

- Duke SIP Project ReportDocument61 pagesDuke SIP Project Reportarijit maity100% (1)

- Vertical Integration in Apparel IndustryDocument15 pagesVertical Integration in Apparel IndustryAyushi ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15 Channels of Distribution: Conflict, Cooperation, and ManagementDocument23 pagesChapter 15 Channels of Distribution: Conflict, Cooperation, and ManagementJ.C100% (2)

- Marketing in PractiseDocument19 pagesMarketing in PractiseMikhil Pranay SinghNo ratings yet

- Gourav Weikfield FileDocument24 pagesGourav Weikfield FileGourav RajputNo ratings yet

- Ateneo de Davao University Senior High School E. Jacinto ST., Davao CityDocument43 pagesAteneo de Davao University Senior High School E. Jacinto ST., Davao CityShaira CogollodoNo ratings yet

- Distribution Strategy: Presented By: Mr. Lalit P. PatilDocument32 pagesDistribution Strategy: Presented By: Mr. Lalit P. PatilAsad khanNo ratings yet

- Policy Analysis of Cocoa Marketing Development in Pohuwato Regency, Gorontalo Province, IndonesiaDocument4 pagesPolicy Analysis of Cocoa Marketing Development in Pohuwato Regency, Gorontalo Province, IndonesiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Icon Iimb Casebook 12 (B)Document182 pagesIcon Iimb Casebook 12 (B)Vasu SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Global Operations Management in AppleDocument20 pagesThe Role of Global Operations Management in AppleMOHAMED rabei ahmedNo ratings yet