Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mecanica Automotriz

Mecanica Automotriz

Uploaded by

Patricia Zaragoza FloresCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mecanica Automotriz

Mecanica Automotriz

Uploaded by

Patricia Zaragoza FloresCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Article

Determinants of Occupational Health Hazards among Roadside

Automobile Mechanics in Sokoto Metropolis, Nigeria

Oche Mansur Oche1,2, Okafoagu Christina Nneka1, Oladigbolu Remi Abiola1, Ismail Raji1, Ango Timane Jessica1, Hashimu Abdulmumini Bala1, Ijapa Adamu1

1

Department of Community Medicine, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, 2Department of Community Health, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto,

Sokoto State, Nigeria

Abstract

Background: Roadside automobile mechanics are in the course of their work exposed to several hazards that put them at risk of severe

debilitating health challenges. This group of workers, however, is reported not to know much about such hazards and to have little or no

training on workplace safety. Aim: The study aimed to identify the determinants of occupational health hazards among roadside automobile

mechanics in Sokoto Metropolis. Methodology: This was a descriptive, cross‑sectional study, and using a two‑stage sampling technique, a

total of 205 roadside mechanics were recruited for the study. A semi‑structured interviewer‑administered questionnaire was used, and the data

were imputed into and analyzed using IBM SPSS. Results: The mean age of the respondents was 31.10 ± 10.19 years, and over one‑third

of them (38.1%) were general vehicle repairers. Majority of the respondents had good knowledge of and attitude toward workplace hazards.

However, a good proportion (91.0%) of the mechanics felt that their occupation was a risky one and 80.1% ate and 86.1% drank while working.

Type of training and job description were the predictors of knowledge of workplace hazards. Job description was the only predictor of attitude.

Burns, bruises, headache/dizziness, and cuts were the most reported work‑related illnesses and injuries. Conclusion: Although most of the

auto‑mechanics were aware and had good knowledge of workplace hazards, they did not adhere to safety practices in the workplace, mostly

due to nonavailability of protective apparels. There is, therefore, need for continuous health education under the platform of the auto‑mechanics

association so that they can voluntarily adopt safety practices in their workplace.

Keywords: Auto‑mechanics, health hazards, predictors, Sokoto

Résumé

Contexte: Au cours de leur travail, les mécaniciens d’automobiles au bord de la route sont exposés à plusieurs risques qui les exposent à de

graves problèmes de santé débilitants. Cependant, ce groupe de travailleurs ne connaît pas grand‑chose à ces dangers et n’a pas ou peu de

formation sur la sécurité au travail. Objectif: L’étude visait à identifier les déterminants des risques professionnels en matière de santé chez

les mécaniciens automobiles de Sokoto Metropolis. Matériel et Méthodes: Il s’agissait d’une étude transversale descriptive et, en utilisant

une technique d’échantillonnage en deux étapes, un total de 205 mécaniciens de bord de route ont été recrutés pour l’étude. Un questionnaire

administré par un intervieweur semi‑structuré a été utilisé et les données ont été imputées et analysées à l’aide d’IBM SPSS. Résultats: L ‘âge

moyen des répondants était de 31.10 ± 10.19 et plus d’ un tiers d ‘entre eux (38.1%) étaient des réparateurs de véhicules généraux. La majorité

des répondants avaient de bonnes connaissances et une bonne attitude à l’égard des dangers au travail. Cependant, une bonne partie des

mécaniciens estimaient que leur profession était risquée 183 (91,0%)

et majoritaire, en mangeait 161 (80,1%) et en buvait 173 (86,1%) Address for correspondence: Prof. Oche Mansur Oche,

pendant qu’ils travaillaient. Le type de formation et la description Department of Community Medicine, Usmanu Danfodiyo University,

de poste étaient des prédicteurs de la connaissance des dangers au Sokoto, Sokoto State, Nigeria.

travail. La description de travail était le seul prédicteur de l’attitude. E‑mail: ochedr@hotmail.com

Les brûlures, les ecchymoses, les maux de tête/vertiges et les coupures

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to

remix, tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as appropriate credit

is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Access this article online For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

Quick Response Code:

Website: How to cite this article: Oche OM, Nneka OC, Abiola OR, Raji I,

www.annalsafrmed.org Jessica AT, Bala HA, et al. Determinants of occupational health hazards

among roadside automobile mechanics in Sokoto Metropolis, Nigeria. Ann

Afr Med 2020;19:80-8.

DOI:

10.4103/aam.aam_50_18 Submitted: 05-Nov-2018 Revised: 18-Jul-2019

Accepted: 25-Aug-2019 Published: 03-Jun-2020

80 © 2020 Annals of African Medicine | Published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

étaient les maladies et les blessures liées au travail les plus souvent rapportées. Conclusion: Bien que la plupart des mécaniciens et des

mécaniciennes d’automobiles aient été au courant et aient une bonne connaissance des risques au travail, ils n’ont pas respecté les pratiques de

sécurité sur le lieu de travail. Il existe donc un besoin d’éducation continue en matière de santé dans le cadre de la plate‑forme de l’association

de mécanique automobile afin qu’ils puissent adopter volontairement des pratiques de sécurité sur leur lieu de travail.

Mots-clés: Auto-mécanique, déterminants, risques pour la santé, Sokoto

Introduction auto‑mechanics directly involved in the vehicular repair were

included in the study. Spare part dealers and hawkers were

The automobile service industry has a large group of workers

excluded. Participation in the study was limited to consenting

with many being in the unorganized sector.[1] They are involved

respondents.

in numerous activities which expose them to many physical,

biological, and chemical agents that can be hazardous to their A two‑stage sampling technique was used to recruit the study

health.[2] These workers are also prone to workplace accidents subjects. In the first stage, one auto‑mechanic area (cluster)

and injuries, many of which are preventable.[2] The International was selected using simple random sampling technique, out of

Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that yearly, approximately four auto‑mechanic areas (clusters) within Sokoto Metropolis.

270 million work‑related accidents occur worldwide. [3] In the second stage, a systematic sampling technique was used

Employees in small and medium enterprises have been shown to recruit 205 auto‑mechanics, out of 615 (using a sampling

to be more prone to work‑related hazards and risks.[4] This interval of 3–N/n) in the selected area (after obtaining a

group of workers, however, is reported not to know much about comprehensive list of all the auto‑mechanics in the selected

such hazards and to have little or no training on workplace area from the executives of the association of auto‑mechanics

safety.[5] The control of occupational hazards decreases the in Sokoto).

incidence of accidents and work‑related diseases, as well as

The data were collected using a pretested semi‑structured

improves the health and general morale of the labor force. This,

interviewer‑administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was

in turn, leads to increased workers’ efficiency and decreased

pretested among auto‑mechanics in another cluster – Sahara

absenteeism from work.[6] In most cases, the economic benefits

in Sokoto. The questionnaire contained both open‑ and

far outweigh the costs of eliminating hazards.[6‑8] In Nigeria,

closed‑ended questions on sociodemographic characteristics

roadside automobile mechanics belong to the informal sector

and work profile of the respondents and the knowledge,

of the economy and the occupational problems and health

attitude, and practice of safety measures. The questionnaire

needs of these workers are not well documented.[9] Therefore,

was adopted from previous studies.[12,13] Research assistants

their coverage by occupational health services is negligent and

were recruited and were trained on the objectives of the study

they are exposed to precarious conditions in the workplace.[10]

and the general administration of the study instruments.

Our study therefore was aimed at assessing the determinants

of occupational health hazards among roadside automobile The questionnaire was checked for completeness and entered

mechanics in Sokoto Metropolis, Nigeria. into IBM SPSS® Version 25 (NY, USA). The data were

summarized using frequencies and percentages and were

Methodology presented as tables. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were

carried out to determine the level of associations and predictors

This was a descriptive cross‑sectional study carried out in

of workplace hazards.

Sokoto Metropolis located at Sokoto State, Northwest Nigeria.

The study population comprised all roadside mechanics in Each correct answer on the knowledge questions was

Sokoto Metropolis. Sokoto State has 23 local government awarded a mark, with no marks awarded for wrong answers.

areas (four of which are within the metropolis), with a land Knowledge was graded with scores ≥75 and <75 adjudged

mass of 25,972 km2 and an estimated population of 4,802,298 adequate and inadequate knowledge, respectively. Similarly,

projected for 2017.[11] Farmers form the greater percentage every correct answer to the attitude question was awarded one

of the population, and they majorly reside in the rural areas, mark, with no marks for wrong answers. Attitude was graded

while the rest are civil servants, traders, artisans, and people with scores ≥65 and <65% adjudged as positive and negative

of other occupations such as tanning and dyeing (and these attitude, respectively. The level of statistical significance was

are mainly concentrated in the metropolis, being the center of set at P < 0.05 at 95% confidence interval.

commercial activities in the State).

Approval for the study was sought from the Ethical Committee

The sample size for the study was calculated using the formula of the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital,

for cross‑sectional descriptive study; using the assumption that Sokoto. Permission to carry out the study was sought from the

the proportion of those estimated to use protective devices was Association of Auto‑Mechanics, and verbal informed consent

14% from a previous study[12] and a 10% nonresponse rate, a was obtained from each study subject after detailed explanation

total of 205 auto‑mechanics were recruited into the study. Only of the objectives and the procedures of the study.

Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020 81

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

Results 185 (92.0%) reported cuts and lacerations, and 145 (71.4%)

reported incidents of fire outbreak as part of hazards at

A total of 205 questionnaires were administered to the

their workplace. One hundred and twenty‑one (59.6%)

respondents. All questionnaires administered were completely

of the auto‑mechanics had good knowledge of workplace

filled, returned, and analyzed after validation (giving a response

hazards [Table 3].

rate of 100%). The ages of the study participants ranged from

15 to 56 years, with a mean age of 31.1 ± 10.2 years. Of More than three‑quarters, 87 (73.7%), of the general repair/

205 auto‑mechanics, 95 (46.8%) of them were single, only engine mechanics had adequate knowledge of workplace

1 (0.5%) was either separated, divorced, or cohabiting, with hazard compared to 33 (39.3%) of body works/electrical and

more than half, 104 (51.7%) of them having secondary school other mechanics. The difference was statistically significant,

education [Table 1]. P < 0.001. All other sociodemographic variables were not

associated with knowledge of work place hazard [Table 4].

Majority, i.e. 169 (86.2%), of the respondents worked on

full‑time basis, with 118 (58.4%) working as general vehicle Majority of the mechanics felt that their occupation was a risky

repairers/engine mechanics. One hundred and seven (53.2%) one 183 (91.0%), dangers of their occupation can be reduced by

respondents had put in less than 10 years of working experience. any means 193 (96.5%), and the use of protective appliances

One hundred and twenty (59.4%) respondents worked for more were desirable at their workplace 193 (96.5%). Almost all

than 8 h a day, 76 (37.4) were apprentices, and only 20 (10%) 188 (93.5%) the respondents had positive attitude toward

had attended a training on hazard prevention [Table 2]. workplace hazards with 112 (96.6%) of the general repair/engine

mechanics having positive attitude, while 75 (89.3) of body

One hundred and eighty (90.0%) of the respondents had never works/electrical/others had positive attitude and the differences

attended any training on the prevention of hazards at workplace, were statistically significant, P = 0.04 [Tables 5 and 6]. Table 7

190 (94.5%) were aware of exposure to hazards at their shows that those with formal education were 96% less likely to

workplace, 183 (92.4%) reported harsh weather conditions; have poor knowledge, P = 0.032 (or those with good knowledge

were 5.1 times more likely to have good knowledge of workplace

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents hazard). Roadside mechanics whose job involved general

repair or engine repair were 4.6 times more likely to have

Variables Frequency (%)

good knowledge compared to car electrician, body works, and

Age (years)

others, P < 0.001 (or body works, electrical, and others were

<40 159 (78.3)

≥40 44 (21.7)

Total 203 (100) Table 2: Work pattern and job description of respondents

Marital status of respondents

Variables Frequency (%)

Single 95 (46.8)

Married 103 (50.7) Work pattern

Separated 1 (0.5) Full-time 169 (86.2)

Divorced 1 (0.5) Part-time 27 (13.8)

Widowed 2 (1.0) Total 196 (100.0)

Co-habiting 1 (0.5) Job description

Total 203 (100) General repair/engine 118 (58.4)

Educational level Body works/electrical/others 84 (41.6)

Informal 9 (4.5) Total 202 (100.0)

Formal 192 (95.5) Work experience (years)

Total 201 (100) <10 107 (53.2)

Tribe ≥10 94 (46.8)

Hausa 43 (21.2) Total 201 (100.0)

Fulani 0 (0.0) Work hours per day

Igbo 15 (7.4) ≤8 82 (40.6)

Yoruba 121 (59.6) >8 120 (59.4)

Others* 24 (11.8) Total 202 (100.0)

Total 203 (100) Work category

Daily income (Naira) Apprentice 76 (37.4)

<500 11 (5.5) Employed 127 (62.6)

500-1000 55 (27.6) Total 203 (100.0)

1001-2999 23 (11.6) Attended any training on hazard prevention

≥3000 110 (55.3) Yes 20 (10.0)

Total 199 (100) No 180 (90.0)

*Others - Zuru, Edo, Igala, Kaaba, and Bandel Total 200 (100.0)

82 Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

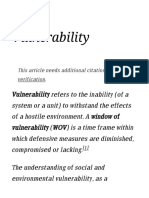

180

Table 3: Awareness and knowledge of workplace hazard 166

161

160

among respondents 153

140 131

Variables Frequency (%)

Number of respondents

120

Are you aware that you are exposed to hazard at your

100

workplace?

80

Yes 190 (94.5)

No 11 (5.5) 60

Is the weather part of the hazards at your workplace? 40

Yes 176 (92.4) 20

No 14 (7.6) 0

Handwashing with fuel Washing vehicle Applying Sucking of fuel

If yes, what weather conditions affect you most at parts with fuel fuel/hydraulic bruises

your workplace?

Excessive sunlight 148 (84.2) Figure 1: Respondents’ work habits

Excessive cold 4 (2.2)

Wind 14 (8.2) 2.3 times more likely to have good practice), P = 0.029. Those

Rainfall 9 (4.9)

who had good knowledge were 64.9% less likely to have poor

Others 1 (0.5)

practice (or those who have poor knowledge were 2.9 times

Cuts and Lacerations are part of hazards at your

workplace more likely to have good practice), P = 0.003 [Table 9].

Yes 162 (92.0) Majority of the respondents exhibited habits such as washing

No 14 (8.0) hands with fuel, 166 (82.6%), and applying fuel or hydraulics to

Fire outbreak is part of hazard at your workplace wounds [Figure 1]. Table 10 shows that there was a statistically

Yes 126 (71.4) significant relationship between job description and all the

No 50 (28.6) habits examined. A higher percentage of general repair/engine

Tetanus is a complication of hazards in your mechanics were involved in the harmful habits compared to the

workplace

other mechanics, P < 0.001.

Yes 96 (54.7)

No 80 (45.3) The commonly experienced work‑related illnesses were bruises

Is your workplace prone to breading of mosquitoes? 171 (89.5%), headaches/dizziness 159 (83.7%), and cuts and

Yes 189 (94.5) punctures 152 (80.0%). A higher proportion of general vehicle

No 11 (5.5) repairers/engine mechanics (61, 61.0%), experienced burns

Is your workplace prone of rat infestation? compared to body works and other mechanics, although this

Yes 170 (84.6)

was not statistically significant, P = 0.302. Crushed digits, cuts

No 31 (15.4)

and punctures, and headaches/dizziness were more common

Petrol is a hazard at your workplace?

among the general repair/engine mechanics, and this were all

Yes 133 (75.9)

No 43 (24.1)

statistically significant, P < 0.005 [Tables 11 and 12].

Grease causes hazards at your workplace?

Yes 102 (58.1) Discussion

No 74 (41.9)

Auto‑mechanics are involved in numerous activities which

Drinking engine oil is harmful?

expose them to many physical and chemical hazards that

Yes 155 (76.7)

No 47 (23.3)

could be detrimental to their health.[2] Auto‑mechanics in this

Battery acid is harmful to the skin? study were found to be predominantly males, and this is not

Yes 173 (85.2) surprising as the job is physically demanding and strenuous

No 30 (14.8) limiting female participation. This is in agreement with several

Hazards in your occupation include fatigue? similar studies.[5,9,10,12‑14] Over half of the respondents worked

Yes 170 (89.9) for over 8 h per day. This is not encouraging as most of the

No 20 (10.1) workers did not meet the limit of a maximum work hour of

Knowledge of workplace hazards 8 h per day as stipulated by the hours of work convention

Adequate (≥ 75%) 113 (59.6) 1930 (No. 30), which is an ILO standard aimed at providing

Inadequate (50%-74.9%) 82 (40.4) protection for workers’ safety and health, thereby allowing

for a fair balance between work and family life.[15] Workers

4.6 times more likely to have poor knowledge of workplace who spent more than 8 h per day may experience more stress

hazards). Those with inadequate knowledge were 82% less at the end of the day, and this could also increase the risk of

likely (or 5.5 times less likely) to have positive attitude [Table 8]. hazards at the workplace. A similar study in Uyo, Nigeria, is

Those with apprenticeship training were 56.5% less likely to in consonance with this finding as over half of the respondents

have poor practice (or those with apprenticeship training were in that study worked for 9–12 h per day.[16]

Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020 83

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

Table 4: Factors associated with knowledge of workplace hazard among respondents

Variables Inadequate knowledge Adequate knowledge Test statistic P

Age group (years)

<40 66 (41.5) 93 (58.5) 0.379 0.538

≥40 16 (36.4) 28 (63.6)

Education

Informal 6 (66.7) 3 (33.3) Fisher’s exact 0.163

Formal 76 (39.6) 116 (60.4)

Training

Nonapprenticeship 27 (34.6) 51 (65.4) 1.757 0.185

Apprenticeship 55 (44.0) 70 (56.0)

Nature of work

Apprentice 33 (43.4) 43 (56.6) 0.462 0.497

Employed 49 (38.6) 78 (61.4)

Years of experience

<10 47 (43.9) 60 (56.1) 1.251 0.263

≥10 34 (36.2) 60 (63.8)

Job description

General repair/engine 31 (26.3) 87 (73.7) 24.139 <0.001

Body works, electrical, and others 51 (60.7) 33 (39.3)

Attended any training on how to prevent hazards at workplace

Yes 7 (35.0) 13 (65.0) 0.331 0.565

No 75 (41.7) 105 (58.3)

In this study, majority of the respondents were aware of

Table 5: Respondents’ attitude toward workplace hazard

exposure to hazards at their workplace. This may not be

Variables Frequency (%) unrelated to the fact that most of them had secondary level

Do you feel your occupation is a dangerous one? of education and had worked for more than 5 years and so

Yes 183 (91.0) were aware of the hazards. This is in contrast to a study in

No 18 (9.0) Ilorin, Nigeria, which revealed that auto‑mechanics were

Do you feel the danger of your occupation can be not aware of the full extent of occupational hazards to which

reduced by any means?

Yes 193 (96.5)

they were exposed.[14] Although this group of workers has

No 7 (3.5)

been reported not to know much about hazards in their

Do you feel the use of protective gadgets is desirable workplace,[4] it is impressive to note that workers in this study

in your occupation? were quite knowledgeable as a large proportion of them had

Yes 193 (96.5) good knowledge of the hazards they were exposed to in the

No 7 (3.5) workplace. A similar study in Uyo, Nigeria, also found that

Would you be willing to use protective gadgets if eight out of every ten respondents had good knowledge of the

introduced to you?

use of personal protective equipment (PPE).[16] However, very

Yes 198 (98.5)

few respondents in this study reported receiving any form of

No 3 (1.5)

training on workplace safety. Adequate training has been found

Do you feel the tools you use at the workplace can

cause bodily harm to you? to lead to increased consciousness of workplace hazards and

Yes 190 (94.5) the role of safety measures in minimizing their effects. Other

No 11 (5.5) studies in Nigeria and India even revealed that no respondents

Do you feel you are fully aware of safety measures received any form of training on workplace safety.[1,16]

that you should use to protect yourself while

working? The study also found that more than half of the respondents

Yes 177 (88.1) with apprenticeship training (56.4%) and nonapprenticeship

No 24 (11.9) training (51, 65.4%) had adequate knowledge of workplace

Do you feel you can help protect your health and hazards, and these findings were statistically significant.

safety while working by making some changes to the A higher proportion of general vehicle repairer/engine

way you work?

mechanics had adequate knowledge of workplace hazard. This

Yes 193 (96.0)

No 8 (4.0)

could be related to their more in‑depth and extensive training

General attitude toward workplace hazards compared to the other forms of mechanics.

Positive (≥75%) 188 (93.5) The significant predictors of knowledge of workplace hazard

Negative (<75%) 13 (6.5) in this study were education and job description. Respondents

84 Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

Table 6: Factors associated with attitude toward Table 8: Predictors of attitude toward workplace hazards

workplace hazards among respondents among respondents using binary logistic regression

Variables Poor Good Test P analysis

attitude attitude statistics Predictors aOR 95% CI for Exp(B) P

Age group (years) Lower Upper

<40 11 (7.0) 146 (93.0) Fisher’s 0.738

Age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years*) 1.094 0.149 8.014 0.930

≥40 2 (4.5) 42 (95.5) exact test

Education (informal vs. formal*) 0.186 0.023 1.503 0.115

Education

Training (nonapprenticeship vs. 0.652 0.176 2.411 0.521

Informal 2 (22.2) 7 (77.8) Fisher’s 0.109 apprenticeship*)

Formal 11 (5.8) 179 (94.2) exact test

Nature of work 0.366 0.079 1.699 0.200

Training (apprentice vs. employed*)

Nonapprenticeship 5 (6.5) 72 (93.5) Fisher’s 1.000 Work experience 1.286 0.236 7.022 0.772

Apprenticeship 8 (6.5) 116 (93.5) exact test (<10 years vs. ≥10 years*)

Nature of work Job description (general repair/engine 3.728 0.781 17.790 0.099

Apprentice 7 (9.3) 68 (90.7) Fisher’s 0.241 vs. bod works, electrical, and others*)

Employed 6 (4.8) 120 (95.2) exact test Attended any training on hazard 0.928 0.094 9.144 0.949

prevention (yes vs. no*)

Work experience (years)

Knowledge 0.182 0.036 0.909 0.038

<10 8 (7.5) 98 (92.5) 0.382 0.536

(inadequate vs. adequate*)

≥10 5 (5.4) 88 (94.6)

*Reference group. aOR=Adjusted odds ratio, CI=Confidence interval

Job description

General repair/engine 4 (3.4) 112 (96.6) 4.232 0.040

Body works, electrical, 9 (10.7) 75 (89.3) Table 9: Predictors of practice

and others

Work hours per day Predictors aOR 95% CI for aOR P

≤8 3 (3.7) 79 (96.3) 1.846 0.174 Lower Upper

>8 10 (8.5) 108 (91.5) Age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years*) 0.690 0.266 1.787 0.445

Knowledge Education (informal vs. formal*) 0.199 0.035 1.125 0.068

Inadequate 11 (13.6) 70 (86.4) 11.346 0.001 Training (nonapprenticeship vs. 0.435 0.206 0.918 0.029

Adequate 2 (1.7) 118 (98.3) apprenticeship*)

Nature of work 0.583 0.249 1.365 0.214

(apprentice vs. employed*)

Table 7: Predictors of knowledge of workplace hazards Work experience 0.799 0.333 1.917 0.615

(<10 years vs. ≥10 years*)

among respondents

Job description (general repair/engine 1.617 0.785 3.330 0.192

aOR 95% CI for aOR P vs. bod works, electrical, and others*)

Lower Upper Attended any training on hazard 1.006 0.302 3.348 0.992

prevention (yes vs. no*)

Training (nonapprenticeship vs. 1.154 0.580 2.297 0.683

Knowledge 0.351 0.176 0.701 0.003

apprenticeship*)

(inadequate vs. adequate*)

Education (informal vs. formal*) 0.191 0.042 0.868 0.032

Attitude (<75% vs. ≥75%) 0.416 0.102 1.691 0.220

Nature of work (apprentice vs. 0.682 0.299 1.557 0.363

*Reference group. aOR=Adjusted odds ratio, CI=Confidence interval

employed*)

Work experience 0.877 0.374 2.056 0.763

(<10 years vs. ≥10 years*) secondary education. This finding highlights the importance of

Job description (general repair/engine 4.608 2.402 8.842 <0.001 education even among apprentices. Another study by Sambo

vs. bod works, electrical, and others*) et al. in Zaria, Northwestern Nigeria, reported that the major

Age (<40 years vs. ≥ 40 years*) 1.020 0.415 2.503 0.966 determinants of hazard among roadside mechanics were

Attended any training on hazard 1.081 0.361 3.235 0.889 training type, training duration, years of experience, and level

prevention (yes vs. no*)

*Reference group. aOR=Adjusted odds ratio, CI=Confidence interval

of awareness of protective device.[13]

It is noteworthy that a good number of the respondents had

who had formal education were more likely to have good a positive attitude toward workplace hazards. Psychological

knowledge compared to those with informal education. research has shown that an individuals’ attitude toward

Knowledge about workplace hazard may not necessitate any personal responsibility for safety is closely related to their

form of training because, with observation, it is apparent to likelihood of suffering a workplace accident or disease.[11]

see machines or equipment that may be hazardous to man. Therefore, the positive attitude exhibited by the respondents

The general vehicle repairers/engine mechanics had higher meant that they were less likely to suffer a workplace accident

odds of having adequate knowledge. This might be related to or disease. Furthermore, most of the workers in this study

high literacy among the respondents, half of whom had at least felt that their work was a risky one. In a similar study in

Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020 85

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

Table 10: Association between sociodemographic characteristics and respondents’ work habits

Variable Sucking of fuel Test statistic* P

Job description Yes No

General repair/engine 100 (86.2) 16 (13.8) 54.599 <0.001

Body works, electrical, and others 30 (35.7) 54 (64.3)

Variable Hand - washing with fuel Test statistic* P

Job description Yes No

General repair/engine 115 (99.1) 1 (0.9) 52.956a <0.001

Body works, electrical, and others 50 (59.5) 34 (40.5)

Variable Washing vehicle parts with fuel Test statistic* P

Job description Yes No

General repair/engine 116 (100.0) 0 (0.0) 69.048 <0.001

Body works, electrical, and others 44 (52.4) 40 (47.6)

Variable Applying fuel/hydraulic to treat bruises Test statistic* P

Job description Yes No

General repair/engine 98 (84.5) 18 (15.5) 10.896 0.001

Body works, electrical, and others 54 (64.3) 30 (35.7)

*Pearson’s Chi-square test. aP≤ 0.001 is significant for all the variables examined there

encouraged most of the respondents to use them. This would

Table 11: Work-related illnesses/injuries*

go a long way in reducing the risks associated with their work.

Variables* Frequency (%) However, a study conducted among auto‑mechanics in Ibadan

Burns 101 (53.2) found that protective clothing was not used by the majority of

Bruises 171 (89.5) workers.[5] In contrast to our findings, studies in Tanzania and

Crushed digits 98 (51.6) Saudi Arabia reported low use of PPEs by auto‑echanics.[21,22]

Cuts and punctures 152 (80.0) Several studies have alluded to the fact that PPE provides a

Backaches 145 (76.3)

physical barrier to workplace hazards.[23,24]

Joint pains 95 (50.0)

Eye irritation/eye injury 44 (23.2) A worrisome trend seen in this study was that a good proportion

Fall from elevated platform 6 (3.2) of workers ate and drank at the workplace. Being in the

Fall on wet floor 11 (5.8) informal sector, there are no specially designated areas for

Fracture bone 13 (6.8) eating or drinking, and so, the workers have no choice but to do

Skin irritation/rashes 35 (18.4) so at the workplace. It is known that some of these workers who

Headaches/dizziness 159 (83.7) consumed their meals in the workshops were greatly exposed

Coughing/chest congestions 98 (51.6) to lead and this has adverse effect on their health.[25,26] This

*Multiple response analysis

underscores the need for the provision of designated eating

areas to reduce exposure to such risks.

India, most of the mechanics opined that their work was

also risky.[17] The study also reported a poor habit practiced among

automobile mechanics at workplace, with majority of them

Respondents’ job description and knowledge of workplace

reported sucking fuel with rubber tubes, washing hands, and

hazards were the only variables associated with attitude of

vehicle parts with fuel. They also applied fuel/hydraulic oil

workplace hazards. However, after controlling for other factors,

to treat bruises and burns. This was common among general

knowledge was the only significant predictor of attitude. This

vehicle repairer/engine compared with other groups. Fuel,

finding is important because, if knowledge of the mechanics

for instance, if absorbed can increase blood lead and benzene

is improved through training or adequate mentorship, then

levels.[27,28] There have been reported cases of lead poisoning

they can have positive attitude toward workplace hazards and

and death from ingestion and inhalation of fuel among

therefore take adequate and necessary precautions to prevent

mechanics.[29] Further, a man whose hands and forearms

workplace hazards.

were heavily exposed to mineral oil hydraulic fluids in his

The self‑reported safety practices among the respondents were job developed weakness in his hands.[30] The different groups

generally good. However, over a third did not wear PPE. PPE of auto‑technicians therefore came in contact with fuel

provides a physical barrier to chemical, physical, and biological while working which may have numerous negative health

hazards at the workplace when these hazards cannot be consequences that includes dermatitis, skin sensitization,

completely precluded.[18‑20] The availability of some of the PPEs eczema, and oil acne.[31]

86 Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

Table 12: Health problems among different groups of automobile mechanics

Variables General repair/engine Body works, electrical, and others Test statistic* P

Burns 61 (61.0) 39 (39.0) 1.067 0.302

Bruises 105 (62.1) 64 (37.9) 8.661 0.003

Crushed digits 65 (67.0) 32 (33.0) 6.504 0.011

Cuts and punctures 95 (62.9) 56 (37.1) 8.283 0.004

Backaches 88 (61.1) 56 (38.9) 2.309 0.129

Joint pains 61 (64.2) 34 (35.8) 3.72 0.054

Eye irritation/eye injury 21 (47.7) 23 (52.3) 2.436 0.119

Fall from elevated platform 3 (50.0) 3 (50.0) 0.146 0.702

Fall on wet floor 10 (90.9) 1 (9.1) Fisher’s exact 0.026

Fracture bone 9 (69.2) 4 (30.8) 0.812 0.367

Skin irritation/rashes 13 (38.2) 21 (61.8) 5.988 0.014

Headaches/dizziness 98 (62.0) 60 (38.0) 7.101 0.008

Coughing/chest ingestion 56 (57.7) 41 (42.3) 0.043 0.835

*Pearson’s Chi square

The common work‑related illnesses/injuries reported by Conflicts of interest

respondents were mainly bruises, headache, dizziness, There are no conflicts of interest.

and cuts/punctures. Burns was reported in a significant

proportion of the respondents. This was probably due

to contact with soldering and welding operations on hot

References

1. Philip M, Alex RG, Sunny SS, Alwan A, Guzzula D, Srinivasan R.

surfaces, exhaust pipes, radiator, and cooling system A study on morbidity among automobile service and repair workers in an

pipes.[31] Although majority of the respondents reported urban area of South India. Indian J Occup Environ Med 2014;18:9‑12.

being aware of the hazards associated with their jobs, that 2. Santana VS, Loomis D. Informal jobs and non‑fatal occupational

awareness did not seem to help reduce the health problems injuries. Ann Occup Hyg 2004;48:147‑57.

3. International Labor Organization. Facts on Safe Work. Available from:

they suffered. The bruises reported could have been due https://www.ilo.org/safework. [Last accessed on 2017 May 18].

to failure to wear PPEs at work while crushed digits, cuts 4. Schneider S, Becker S. Prevalence of physical activity among the

and punctures may occur during lifting of engine parts or working population and correlation with work‑related factors: Results

falls. All these injuries could be worsened due to failure to from the first German National Health Survey. J Occup Health

2005;47:414‑23.

use PPEs. Studies have revealed that working underneath 5. Omokhodion FO. Environmental hazards of automobile mechanics in

vehicles and using heavy machinery and tool for several Ibadan, Nigeria. West Afr J Med 1999;18:69‑72.

hours make auto‑technicians prone to musculoskeletal 6. Asogwa SE. A survey of working conditions in small‑scale industries in

problems and injuries.[32] Nigeria. J Occup Med 1981;23:775‑7.

7. Adegbola O. The impact of urbanization and industrialization on health

Headache or dizziness were often reported by at least eight of conditions: The case of Nigeria. World Health Stat Q 1987;40:74‑83.

every ten general vehicle repairers, auto‑electricians, welders, 8. Asogwa SE. A Guide to Occupational Health Practice in Developing

Countries. 3rd Edition. Nigeria: Fourth Dimension Publisher; 2007 p. 86-90.

motor engine repairers, and panel beaters. Some of them 9. Jinadu MK. Occupational health problems of motor vehicle mechanics,

may work for hours without eating since they do not have a welders, and painters in Nigeria. R Soc Health J 1982;102:130‑2.

restaurant nearby predisposing them to hypoglycemia that can 10. NPC and ICF Macro. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008.

present with headache and dizziness. Abuja, Nigeria: National Population Commission and ICF Macro; 2009.

11. One Test. Work Safety Assessment. Available from: http://www.onetest.

com.au/home/work‑safety. [Last accessed on 2017 May 04].

Conclusion 12. Omokhodion FO, Osungbade OO. Health problems of automobile

mechanics in Nigeria. Trop Doct 1996;26:102‑4.

The study reported good knowledge and attitude of automobile 13. Sambo MN, Idris SH, Shamang A. Determinants of occupational health

mechanics toward workplace hazards. However, their hazards among roadside automobile mechanics in Zaria, North Western

knowledge did not translate to good practices since most of Nigeria. Bo Med J 2012;9:5‑9.

them had poor practices generally, leading to work‑related 14. Awoyemi AO. Awareness about occupational hazards among Roadside

auto mechanics in Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger J Comm Med Prim Health Care

illnesses and injuries. There is need to conduct routine 2002;14:27‑33.

education on work‑related hazards and ensure provision and 15. International Labour Organization. Working Time in the Twenty‑First

utilization of PPEs during their monthly association meeting Century. Report for Discussion at the Tripartite Meeting of Experts on

to reduce work‑related illnesses and injuries. The provision of Working‑Time Arrangements (17‑21 October 2011). 1st ed. Geneva:

International Labour Office; 2011. p. 3‑9.

designated eating areas will go a long way to reducing exposure 16. Johnson OE, Motilewa OO. Knowledge and use of personal protective

to workplace hazards. equipment among auto technicians in Uyo, Nigeria. Br J Educ Soc

Behav Sci 2016;15:1‑8.

Financial support and sponsorship 17. Thangaraj S, Shireen N. Occupational health hazards among automobile

Nil. mechanics working in an urban area of Bangalore – A cross sectional

Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020 87

Oche, et al.: Annals of African medicine 2020

study. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2017;6:18‑22. association with smoking and personal hygienic behaviour among lead

18. Alli BO. Fundamental Principles of Occupational Health and Safety. exposed workers. Occup Environ Med 2005;62:300‑3.

2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office; 2008. 26. World Health Organization. Recommended Health‑Based Limits in

19. Yeung RS, Chan JT, Lee LL, Chan YL. The use of personal protective Occupational Exposures to Health Metals, Report of WHO Study

equipment in Hazmat incidents. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 2002;9:171‑6. Group 647. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980.

20. Felicia N, Karen‑Leigh E, Cally M. Current evidence regarding 27. Oluwagbemi BF. Basic Occupational Health and Safety. 2nd ed. Ibadan,

non‑compliance with personal protective equipment: An integrative Nigeria: Vertex Media Limited; 2007.

review to illuminate implications for nursing practice. ACORN J 28. Udonwa NE, Uko EK, Ikpeme BM, Ibanga IA, Okon BO. Exposure

Perioper Nurs Aust 2012;25:22‑30. of petrol station attendants and auto mechanics to Premium

21. Rongo LM, Barten F, Msamanga GI, Heederik D, Dolmans WM. Motor Spirits Fumes in Calabar, Nigeria. J Environ Public Health

Occupational exposure and health problems in small‑scale industry 2009;2009:1‑5.

workers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: A situation analysis. Occup 29. Anetor JI, Babalola OO, Adeniyi FA, Akingbola TS. Observations on

Med (Lond) 2004;54:42‑6. the hemapoeitic systems in tropical lead poisoning. Niger J Physiol Sci

22. Taha AZ. Knowledge and practice of preventive measures in small 2002;17:9‑15.

industries in Al‑Khobar. Saudi Med J 2000;21:740‑5. 30. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological

23. Neo F, Edward K, Mills C. Current evidence regarding noncompliance Profile for Hydraulic Fluid. Atlanta, GeorgiaA, USA: Agency for Toxic

with personal protective equipment: An integrative review to illuminate Substances and Disease Registry; 1997.

implications for nursing practice. ACORN J Perioper Nurs Austr 31. International Labour Organization. Encyclopaedia of Occupational

2012;25:22‑6. Health and Safety. 4th ed., Vol. 3. Geneva: International Labour

24. Yeung RS, Chan JT, Lee LL, Chan YL. The use of personal protective Organization; 1998. p. 26‑102.

equipment in Hazmat incidents. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 2002;9:171‑6. 32. Punnett L, Wegman DH. Work related musculoskeletal disorders: The

25. Karita K, Nakao M, Ohwaki K, Yamanouchi Y, Nishikitani M, epidemiological evidence and the debate. L Electromyogr Kinesiol

Nomura K, et al. Blood lead and erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels in 2004;14:13‑2.

88 Annals of African Medicine ¦ Volume 19 ¦ Issue 2 ¦ April-June 2020

Copyright of Annals of African Medicine is the property of Wolters Kluwer India Pvt Ltd and

its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the

copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email

articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Research ProposalDocument8 pagesResearch Proposalaeinekipla100% (1)

- 2019, Evaluation of Ergonomic Working Conditions Among Standing Sewing Workstation in Sri LankaDocument14 pages2019, Evaluation of Ergonomic Working Conditions Among Standing Sewing Workstation in Sri LankaEyob MinbaleNo ratings yet

- An Instructional Aid For Occupational Safety and Health in Mechanical Engineering Design: Enter asset subtitleFrom EverandAn Instructional Aid For Occupational Safety and Health in Mechanical Engineering Design: Enter asset subtitleNo ratings yet

- List of Hospital in ChennaiDocument42 pagesList of Hospital in Chennaisandeep pathare0% (1)

- Occupational Hazards in Two Automobile ADocument8 pagesOccupational Hazards in Two Automobile AChuka OmeneNo ratings yet

- Mansur 2016 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 105 012033Document10 pagesMansur 2016 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 105 012033Fahmi MatarangNo ratings yet

- IOP Conference OSHA 1994Document9 pagesIOP Conference OSHA 1994Sangary SubraNo ratings yet

- Safety and Health at Work: Original ArticleDocument6 pagesSafety and Health at Work: Original ArticlePedro RojasNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Associated Factors With Work Related Injuries Among Workers in Etab Soap and DeteregentDocument8 pagesPrevalence and Associated Factors With Work Related Injuries Among Workers in Etab Soap and DeteregentAnonymous 3G8yot4No ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Workers Towards Accident Prevention in A Selected Construction Company, Kano State, NigeriaDocument31 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Practice of Workers Towards Accident Prevention in A Selected Construction Company, Kano State, NigeriaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment at The Cosmetic ProductDocument7 pagesRisk Assessment at The Cosmetic ProductKoukis PericlesNo ratings yet

- Ergonomic Study of Power-Loom Industry Woman Workers From Solapur City, Maharashtra, IndiaDocument5 pagesErgonomic Study of Power-Loom Industry Woman Workers From Solapur City, Maharashtra, IndiaJournalNX - a Multidisciplinary Peer Reviewed JournalNo ratings yet

- Journal Paper - Batch b6Document7 pagesJournal Paper - Batch b6Sushma SriNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Ergonomic Hazards in Workstations and The Effects On Selected Public ServantsDocument6 pagesAssessment of Ergonomic Hazards in Workstations and The Effects On Selected Public ServantsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- A Risk Assessment of Two Automobile Repair CentresDocument12 pagesA Risk Assessment of Two Automobile Repair CentressajinNo ratings yet

- ManufactringPublicServiceandConstructionHazard TsHjEsa MLROct2020Document16 pagesManufactringPublicServiceandConstructionHazard TsHjEsa MLROct2020Ummi SyafiqahNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Work Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Electronics Manufacturing Workers: A Cross-Sectional Analytical Study in ChinaDocument11 pagesThe Prevalence and Risk Factors of Work Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Electronics Manufacturing Workers: A Cross-Sectional Analytical Study in ChinaMohamad Ashraf Mohd AminudinNo ratings yet

- JPNR - S01, 2023 - 199Document16 pagesJPNR - S01, 2023 - 199Education serviceNo ratings yet

- WishaDocument12 pagesWishaRisnaldi Nur HakikiNo ratings yet

- Icmere2017 Pi 326Document8 pagesIcmere2017 Pi 326giovadiNo ratings yet

- Safety and Health at Work: Original ArticleDocument9 pagesSafety and Health at Work: Original ArticleAfrisal AriefNo ratings yet

- A Survey On Fatigue Detection of Workers Using Machine LearningDocument8 pagesA Survey On Fatigue Detection of Workers Using Machine Learningotik brebesNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Impact of Occupational Health and Safety Practice On The Lives of Construction Workers.A Case Study of Consa LimitedDocument8 pagesAssessing The Impact of Occupational Health and Safety Practice On The Lives of Construction Workers.A Case Study of Consa LimitedrookieNo ratings yet

- Knowledge of Occupational Hazards and Safety PractDocument7 pagesKnowledge of Occupational Hazards and Safety PractJoven CastilloNo ratings yet

- Identifying and Eliminating Industrial Hazards in RMG Industries: A Case StudyDocument8 pagesIdentifying and Eliminating Industrial Hazards in RMG Industries: A Case StudyijsretNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ScopusDocument5 pagesJurnal ScopusfaniNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2093791122000439 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S2093791122000439 MainCsanyi EditNo ratings yet

- Identification of Occupational Injury Among The Workers of Selected Cement Industries in Bangladesh-A Case StudyDocument7 pagesIdentification of Occupational Injury Among The Workers of Selected Cement Industries in Bangladesh-A Case StudyAnonymous iI88LtNo ratings yet

- Ozge Acuner Selcuk Cebi: An Effective Risk-Preventive Model Proposal For Occupational Accidents at ShipyardsDocument18 pagesOzge Acuner Selcuk Cebi: An Effective Risk-Preventive Model Proposal For Occupational Accidents at ShipyardsAli AliyevNo ratings yet

- Akar Report 0055Document25 pagesAkar Report 0055AkarNo ratings yet

- ECONOMIC ImplicationDocument12 pagesECONOMIC ImplicationIdris Aji DaudaNo ratings yet

- Arimbi 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 505 012038Document9 pagesArimbi 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 505 012038Muhammad IzehagaNo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 8888Document10 pages2020 Article 8888Gebisa GuyasaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 PDFDocument15 pagesAssignment 1 PDFaqilah fatinNo ratings yet

- Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems and Their Compliance Among Petrol Stations in Kenya: A Case Study in Nakuru CountyDocument8 pagesOccupational Safety and Health Management Systems and Their Compliance Among Petrol Stations in Kenya: A Case Study in Nakuru CountymichealNo ratings yet

- Butil, J.M - Laboratory No. 1Document13 pagesButil, J.M - Laboratory No. 1Jefrey M. ButilNo ratings yet

- 188850-Article Text-479663-1-10-20190813 PDFDocument8 pages188850-Article Text-479663-1-10-20190813 PDFLuis EcheverriNo ratings yet

- Awareness of Construction Workers On Occupational Hazards, Illness and Injuries Associated With Construction Industry in Mombasa CountyDocument8 pagesAwareness of Construction Workers On Occupational Hazards, Illness and Injuries Associated With Construction Industry in Mombasa CountyIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Workplace Harzards in An Onshore Facility Located at Ozoro Delta SDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Workplace Harzards in An Onshore Facility Located at Ozoro Delta SImonikosaye ToboreNo ratings yet

- Health and Safety AMENDED - 20mayDocument48 pagesHealth and Safety AMENDED - 20mayAmit PasiNo ratings yet

- Ayob 2018 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 140 012095Document11 pagesAyob 2018 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 140 012095Amirul AmmarNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics For Electronics Manufacturing: January 2006Document7 pagesErgonomics For Electronics Manufacturing: January 2006andrei CalloNo ratings yet

- Analisis Penyebab Human Error Terhadap Kejadian Kecelakaan Pada Teknisi Di Perusahaan Otomotif X, SemarangDocument7 pagesAnalisis Penyebab Human Error Terhadap Kejadian Kecelakaan Pada Teknisi Di Perusahaan Otomotif X, SemarangTejaPradnyanaNo ratings yet

- Occupational Accidents: A Comparative Study of Construction and Manufacturing IndustriesDocument6 pagesOccupational Accidents: A Comparative Study of Construction and Manufacturing IndustriesEric 'robo' BaafiNo ratings yet

- Study of Ergonomics in Textile Industry: Nemailal TarafderDocument9 pagesStudy of Ergonomics in Textile Industry: Nemailal TarafderSAURAV KUMARNo ratings yet

- Study of Ergonomics in Textile IndustryDocument9 pagesStudy of Ergonomics in Textile IndustryThu Lan NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Construction SafetyDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Construction Safetyakjnbowgf100% (1)

- The Importanceof Trainingfor Preventing Occupational RisksDocument6 pagesThe Importanceof Trainingfor Preventing Occupational RisksJosiahNo ratings yet

- Environmental Risk Assessment To Prevent Occupational Diseases in Industry 4.0 An IoT Based Model of Hydrocarbon Processing ComplexDocument11 pagesEnvironmental Risk Assessment To Prevent Occupational Diseases in Industry 4.0 An IoT Based Model of Hydrocarbon Processing ComplexragilpriyantoNo ratings yet

- 6507 With Cover Page v2Document9 pages6507 With Cover Page v220P438 - BALAJI V GNo ratings yet

- 875-Article Text-5689-1-10-20200925Document9 pages875-Article Text-5689-1-10-20200925Muhammad KashifNo ratings yet

- CE (Ra1) F (SK) PF1 (SHG SL) PFA (SHG KM) PN (KM)Document5 pagesCE (Ra1) F (SK) PF1 (SHG SL) PFA (SHG KM) PN (KM)MetinNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0213911120302806 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0213911120302806 Mainafri pakalessyNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Industrial ErgonomicsDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Industrial ErgonomicsErick YamamotoNo ratings yet

- Evaluation - of - Safety - and - Health - Performance - On - Con KulaDocument11 pagesEvaluation - of - Safety - and - Health - Performance - On - Con KulaabdirahmanNo ratings yet

- Work Related Injuries and Associated Factors Among Small Scale Industry Workers of Mizan-Aman Town, Bench Maji Zone, Southwest EthiopiaDocument9 pagesWork Related Injuries and Associated Factors Among Small Scale Industry Workers of Mizan-Aman Town, Bench Maji Zone, Southwest EthiopiaaamichoNo ratings yet

- Ergonomic Risk Assessment of Workers in Garment IndustryDocument7 pagesErgonomic Risk Assessment of Workers in Garment IndustryEngrWasiAhmadNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Occupational Safety and Health Administration Status of College of Health Sciences and Technology, Idah Kogi StateDocument11 pagesEvaluation of Occupational Safety and Health Administration Status of College of Health Sciences and Technology, Idah Kogi StateInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal Work-Related Disorders and Ergonomic Hazards Among Bank - Employees in State of KuwaitDocument8 pagesMusculoskeletal Work-Related Disorders and Ergonomic Hazards Among Bank - Employees in State of KuwaitInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- A Study To Assess The Knowledge Regarding Occupational Hazards and Utilization of Safety Measures Among Construction Labourers at Selected Construction Sites of JodhpurDocument3 pagesA Study To Assess The Knowledge Regarding Occupational Hazards and Utilization of Safety Measures Among Construction Labourers at Selected Construction Sites of JodhpurInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Bienestar LaboralDocument16 pagesBienestar LaboralVILLY YAQUELINY PEREZ DIAZNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry Quiz OneDocument5 pagesBiochemistry Quiz Onesehrish_salamNo ratings yet

- Contraception Is Not A New Idea.: Contraception (Birth Control Methods and Techniques)Document2 pagesContraception Is Not A New Idea.: Contraception (Birth Control Methods and Techniques)Ivan Dennis SalupanNo ratings yet

- NoneDocument4 pagesNoneMaw BerryNo ratings yet

- NARAYANA Hrudayala - TariffDocument82 pagesNARAYANA Hrudayala - TariffRama VenugopalNo ratings yet

- Cathy Mertz, RMR, CRR, Official Court Reporter (717) 299-8098Document26 pagesCathy Mertz, RMR, CRR, Official Court Reporter (717) 299-8098Travis KellarNo ratings yet

- Kidney Specialist in Pune - Kidney Doctor in PuneDocument4 pagesKidney Specialist in Pune - Kidney Doctor in PunePriime NephrocareNo ratings yet

- Admission Form 2021-22 MBBS & BDSDocument4 pagesAdmission Form 2021-22 MBBS & BDSAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- Kesehatan Mental Dan Strategi Koping Dalam Perspektif Budaya: Sebuah Studi Sosiodemografi Di Kampung AminweriDocument16 pagesKesehatan Mental Dan Strategi Koping Dalam Perspektif Budaya: Sebuah Studi Sosiodemografi Di Kampung AminweriScritte SNo ratings yet

- Psych Report - Snow WhiteDocument2 pagesPsych Report - Snow Whiteirish xNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology Block 1.3 - PharmacodynamicsDocument12 pagesPharmacology Block 1.3 - Pharmacodynamicsdaleng subNo ratings yet

- EWMA2022 ProgrammeDocument100 pagesEWMA2022 ProgrammeBaitika HayatunnufusNo ratings yet

- Mono Ethylene GlycolDocument9 pagesMono Ethylene GlycolAdminpp MpwkepriNo ratings yet

- LKPD - Recount Text 2Document2 pagesLKPD - Recount Text 2Sabian KalifiNo ratings yet

- Drug Control and Enforcement ActDocument82 pagesDrug Control and Enforcement ActTito MnyenyelwaNo ratings yet

- Orthodontics and Pediatric DentistryDocument62 pagesOrthodontics and Pediatric DentistryAnggaHumalaBeltsazarNapitupuluNo ratings yet

- Initial Medical Evaluation Form For JO1 ApplicantsDocument1 pageInitial Medical Evaluation Form For JO1 ApplicantsBilly Joe BaradiNo ratings yet

- Acupuncture Miriam LeeDocument27 pagesAcupuncture Miriam LeeAnonymous V9Ptmn080% (5)

- Alvin Case 17 EDocument2 pagesAlvin Case 17 EIvyNo ratings yet

- Activity 3 Form 3 - A Physical Fitness Test Score CardDocument4 pagesActivity 3 Form 3 - A Physical Fitness Test Score CardChing DialomaNo ratings yet

- Intraoperative Radiotherapy (IORT) For Surgically Resected Brain Metastases: Outcome Analysis of An International Cooperative StudyDocument15 pagesIntraoperative Radiotherapy (IORT) For Surgically Resected Brain Metastases: Outcome Analysis of An International Cooperative Studyuyenminh2802No ratings yet

- NCP Impaired Social InteractionDocument2 pagesNCP Impaired Social InteractionKristian Karl Bautista Kiw-isNo ratings yet

- Correction and Rehabilitation - Parole and Probation AdministrationDocument12 pagesCorrection and Rehabilitation - Parole and Probation AdministrationRoi BosiNo ratings yet

- Vulnerability - WikipediaDocument24 pagesVulnerability - WikipediaAkhil MeramNo ratings yet

- XI IPA IPS Bahasa Inggris - Kisi2Document11 pagesXI IPA IPS Bahasa Inggris - Kisi2fikriansyah1236No ratings yet

- Professional Teachers - ELEMENTARY 09-2023Document123 pagesProfessional Teachers - ELEMENTARY 09-2023PRC Baguio100% (2)

- Other Hospital Information System (Week 13)Document3 pagesOther Hospital Information System (Week 13)JENISEY CANTOSNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Sexuality: Perceptions, Myths, and RealitiesDocument6 pagesGender Differences in Sexuality: Perceptions, Myths, and RealitiesNicolas Rosales FlorezNo ratings yet

- Asa Physical Status Classification System PDFDocument2 pagesAsa Physical Status Classification System PDFalvionitarosaNo ratings yet

- We Are Like Co WifesDocument9 pagesWe Are Like Co WifesTricianne Merielle S. Bano-oyNo ratings yet