Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Francesca Aran Murphy - Imaginative Apologetics

Francesca Aran Murphy - Imaginative Apologetics

Uploaded by

JacobPaulShermanCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

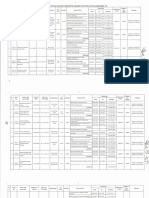

- Choral Speaking MoneyDocument2 pagesChoral Speaking Moneyyuvaranist60% (5)

- Web Application Development Dos and DontsDocument18 pagesWeb Application Development Dos and Dontsaatish1No ratings yet

- Bank Shi-Urkantzu 4 PDFDocument91 pagesBank Shi-Urkantzu 4 PDFJames Johnson100% (3)

- Velde 2013 Modern - TheologyDocument13 pagesVelde 2013 Modern - TheologyJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Fraser MacBride - On The Genealogy of Universals - The Metaphysical Origins of Analytic Philosophy-Oxford University Press (2018)Document272 pagesFraser MacBride - On The Genealogy of Universals - The Metaphysical Origins of Analytic Philosophy-Oxford University Press (2018)JacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Thomas Prufer - Recapitulations - Essays in Philosophy-CUA Press (2018)Document127 pagesThomas Prufer - Recapitulations - Essays in Philosophy-CUA Press (2018)JacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- New Polity Feb 2021 IssueDocument86 pagesNew Polity Feb 2021 IssueJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Religions Faith After The AnthropoceneDocument132 pagesReligions Faith After The AnthropoceneJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Logan Gage - A Saint For Our Times Newman On Faith, Fallibility, and CertitudeDocument17 pagesLogan Gage - A Saint For Our Times Newman On Faith, Fallibility, and CertitudeJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Christian Jambet-TheConstitution of The SUbject and Spiritual PracticeDocument8 pagesChristian Jambet-TheConstitution of The SUbject and Spiritual PracticeJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Carolyn Merchant - Nature As Female ExcerptDocument4 pagesCarolyn Merchant - Nature As Female ExcerptJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Contrasting Concepts of Harmony in Architecture - The 1982 Debate Between Christopher Alexander and Peter EisenmanDocument11 pagesContrasting Concepts of Harmony in Architecture - The 1982 Debate Between Christopher Alexander and Peter EisenmanJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Nature: A Parable: A Poem in Seven BooksDocument9 pagesNature: A Parable: A Poem in Seven BooksJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Patrick Ryan Cooper - The Virginal Middle Towards A Marian MetaxologyDocument25 pagesPatrick Ryan Cooper - The Virginal Middle Towards A Marian MetaxologyJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Mother of Fair LoveDocument43 pagesMother of Fair LoveJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- HE Orld As IFT: - Nicholas J. Healy IIIDocument12 pagesHE Orld As IFT: - Nicholas J. Healy IIIJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Christianity and Platonism in East and West PDFDocument54 pagesChristianity and Platonism in East and West PDFJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Anglican Theology Review of Jacob Holsinger Sherman's Partakers of The DivineDocument4 pagesAnglican Theology Review of Jacob Holsinger Sherman's Partakers of The DivineJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Metaphysics and The Redemption of Sacrifice FinalDocument15 pagesMetaphysics and The Redemption of Sacrifice FinalCubanMonkeyNo ratings yet

- Karen Barad Interview - New MaterialismDocument23 pagesKaren Barad Interview - New MaterialismJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- Aquinas and The Platonists 2002 RevisedDocument34 pagesAquinas and The Platonists 2002 RevisedJacobPaulSherman100% (1)

- (15735664 - Nicholas of PDFDocument33 pages(15735664 - Nicholas of PDFJacobPaulShermanNo ratings yet

- IBIG 04 06 MA Deals Merger Models TranscriptDocument4 pagesIBIG 04 06 MA Deals Merger Models TranscriptіфвпаіNo ratings yet

- Chocolate Cake RecipeTin EatsDocument2 pagesChocolate Cake RecipeTin Eatsantoniapatsalou1No ratings yet

- Constellation Program BrochureDocument2 pagesConstellation Program BrochureBob Andrepont100% (1)

- Title - Different Valuation Models On Jet Airways and SpicejetDocument4 pagesTitle - Different Valuation Models On Jet Airways and SpicejetMohd MudassirNo ratings yet

- Influenza: David E. Swayne and David A. HalvorsonDocument27 pagesInfluenza: David E. Swayne and David A. HalvorsonMelissa IvethNo ratings yet

- Maxwell Flitton - Rust Web Programming - A Hands-On Guide To Developing, Packaging, and Deploying Fully Functional - 53821945Document582 pagesMaxwell Flitton - Rust Web Programming - A Hands-On Guide To Developing, Packaging, and Deploying Fully Functional - 53821945Kwaame Ofori-AdjekumNo ratings yet

- Github Test: Mithun Technologies +91-9980923226 Git and Github Author Mithun Reddy L Web SiteDocument4 pagesGithub Test: Mithun Technologies +91-9980923226 Git and Github Author Mithun Reddy L Web Sitesai bNo ratings yet

- The Art & Science of Coaching 2022Document23 pagesThe Art & Science of Coaching 2022ak cfNo ratings yet

- Barclays 2 Capital David Newton Memorial Bursary 2006 MartDocument2 pagesBarclays 2 Capital David Newton Memorial Bursary 2006 MartgasepyNo ratings yet

- Managing General Overhead Costs FinalDocument43 pagesManaging General Overhead Costs FinalCha CastilloNo ratings yet

- Exercise 5.4 Analyzing EnthymemesDocument2 pagesExercise 5.4 Analyzing EnthymemesMadisyn Grace HurleyNo ratings yet

- Film Title Superhit, Higenre Year of Releholiday Weebudget (In Box Office Cprofit/Loss (Profit/Loss Imdb RatingDocument6 pagesFilm Title Superhit, Higenre Year of Releholiday Weebudget (In Box Office Cprofit/Loss (Profit/Loss Imdb Ratingsenjaliya tanviNo ratings yet

- JohnsonEvinrude ElectricalDocument5 pagesJohnsonEvinrude Electricalwguenon100% (1)

- Kilosbayan Inc. vs. GuingonaDocument1 pageKilosbayan Inc. vs. GuingonaJo LumbresNo ratings yet

- Film Arts Grade - 10Document46 pagesFilm Arts Grade - 10KendrickNo ratings yet

- About Me Working Experiences: Name: Nationality: Marital Status: Gender: Aug 2021 / Present FulfilmentDocument1 pageAbout Me Working Experiences: Name: Nationality: Marital Status: Gender: Aug 2021 / Present FulfilmentHanin MazniNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineer ListDocument9 pagesCivil Engineer ListMohammad AtiqueNo ratings yet

- Modals of InferenceDocument5 pagesModals of InferenceMerry Lovelyn Celez100% (1)

- Passive VoiceDocument1 pagePassive VoiceElhassania ElmouatrachNo ratings yet

- Impairment or Disposal of Long Lived AssetsDocument94 pagesImpairment or Disposal of Long Lived Assetsdiogoross100% (2)

- SUMMATIVE MUSIC AND ARTS With Answer KeyDocument2 pagesSUMMATIVE MUSIC AND ARTS With Answer KeyCath E RineNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Cohesion and Coherence in Modern Linguistics With Reference To English and KurdishDocument11 pagesThe Concept of Cohesion and Coherence in Modern Linguistics With Reference To English and Kurdishنورا عبد النبي خليفNo ratings yet

- Application of Rock Mass Classification Systems ForDocument238 pagesApplication of Rock Mass Classification Systems Fordrtahirnmc100% (1)

- Siemens-BT300 VFDDocument6 pagesSiemens-BT300 VFDdiansulaemanNo ratings yet

- Transportation ModelDocument6 pagesTransportation ModelWang KarryNo ratings yet

- Updated Judicial Notice and ProclamationDocument5 pagesUpdated Judicial Notice and Proclamational malik ben beyNo ratings yet

- Surat Pengajuan PTSL Ke Pertanahan - BPNDocument58 pagesSurat Pengajuan PTSL Ke Pertanahan - BPNdeni hermawanNo ratings yet

Francesca Aran Murphy - Imaginative Apologetics

Francesca Aran Murphy - Imaginative Apologetics

Uploaded by

JacobPaulShermanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Francesca Aran Murphy - Imaginative Apologetics

Francesca Aran Murphy - Imaginative Apologetics

Uploaded by

JacobPaulShermanCopyright:

Available Formats

Louvain Studies 34 (2009-2010) 146-168 doi: 10.2143/LS.34.2.

2118198

© 2010 by Louvain Studies, all rights reserved

In Defence of Imaginative Apologetics

Francesca Aran Murphy

Abstract. — The past half century has involved a renewed interest in the role of

imagination in Christian theology. During this period, several thinkers have mis-

takenly subjugated imagination to systematic theology. This article develops a more

adequate understanding of the relationship between imagination and systematic

theology on the basis of an analysis of thinkers who reflected on this relationship in

the past and by drawing upon the example provided by writers of imaginative

apologetics. The article first illustrates how imaginative apologetics and systematic

theology have more in common with each other than with Theology-and-Imagina-

tion. Then it illustrates and defends the distinction drawn between imaginative

apologetics and systematic theology. Finally, it argues that, although distinct, imag-

inative apologetics and systematics strengthen one another and even coincide in the

discernment of God’s objective self-expression.

I. Imaginative Apologetics Has a Specific Calling

The past half century has given us much historical scholarship into

the thought of two very different theologians, John Henry Newman and

Samuel Taylor Coleridge. It is no coincidence that, simultaneously, quite

disparate voices have claimed that imagination should be central to

Christian theology. It is commonly presupposed that it is to Systematics

that imagination should contribute. Likewise, it is spontaneously

assumed that vigorously imaginative Christian writing can be interpreted

as if it was a contribution to Systematic Theology. So we have academic

clubs dedicated to ‘Theology-and-Imagination’ or ‘Theology-and-the-

Arts’. Theology-and-Imagination shifts uneasily between Theology and

Religious Studies. Scientific theologians don’t see to what use the par-

ticularity and descriptiveness of Christian art can be put; students of

Religion are uncomfortable with its religious intentions. ‘Theological

Imagining’ is often left talking about itself, that is, about the centrality

of Imagination to theology. Academic Christians are ever inclined to give

imagination a capital I, and thus having rendered it suitably theoretical,

to annex it to abstract thought.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 146 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 147

I don’t think this works because, when it takes to the imaginative

mode, the origin and effect of Christian writing is more like that of

poetry than that of theology. I call such writing ‘imaginative apologetics’.

It is the writing which most Christians who read have read and read

again. It is popular Christian writing. From Chesterton’s journalism to

C. S. Lewis’ children’s books to the inspired Christian bloggers like Eve

Tushnet and Maclin Horton, imaginative apologetics jumps in to the

most accessible media of the day. It is consistently down to earth. Its

roots run into popular feeling and spirituality, liturgy, and Scripture.

This is why, to defend the place of imagination in theology, one

needs to defend the distinct existence of ‘imaginative apologetics’, that is,

its resistance to absorption into Systematic theological thought. Many of

the people who grasp the importance of imagination to Christian thinking

reject such a distinction. They feel it would be better to find ‘imaginative

moments’ in the great Systematicians or to invent a more inclusive defini-

tion of Systematics than clearly to distinguish the kinds of human activity

which go into imagining the story of salvation and conceptualizing the dog-

mas of faith. They want to defend imaginative theology against any move

to class it as a forerunner which is left behind as one climbs the intellectual

ladder to Systematics. There are lines in Newman’s writing which seem to

accede to such a ranking. “Without being a poet,” Charles Reding, the

hero of Loss and Gain, is, Newman tells us, “in the season of poetry, in the

sweet spring-time, when the year is most beautiful because it is new. Novelty

was beauty to a heart so open and cheerful as his … because when we first

see things, we see them in a gay confusion, which is a principal element of

the poetical. As time goes on, and we number and sort and measure things

– as we gain views – we advance toward philosophy and truth, but we

recede from poetry.”1 Likewise in imagining the sequence of the great

religious foundations, Newman gives historical priority to the ‘poetical’:

“To St Benedict,” he writes, “let us assign, for his distinctive badge, the

Poetical; to St. Dominic, the Scientific; and to St. Ignatius, the Practical

and Useful.”2 The question is whether such priority entails the precedence

of the imaginative order or, conversely, its supercession, by truth and

science. To defend the distinction, one needs to show that giving poetic

apologetic a special role does not entail subordinating it to Systematics.

1. John Henry Newman, Loss and Gain: The Story of a Convert (London: Burns

& Oates, 1962) 11.

2. John Henry Newman, The Mission of the Benedictine Order (London: John

Long, 1923) 17.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 147 6/06/11 13:56

148 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

It seems to make matters doubly bad to call it imaginative apologetics,

since then we not only have the traditional perception of imagination as

lower than knowledge against us, but we also land smack in the middle

of the traditional construction of apologetics as a precursor to theology.

‘Apologetics’ seems nonetheless to capture the vulgar, extroverted char-

acter of this kind of writing. Christian imaginative writing is popular

because of its breadth. Christians don’t like it only for its exposition of

Christian doctrine, but for its broad humanity: because of this humanity,

it is read by non-Christians, and so functions apologetically. One kind of

philosophical apologetics used to attempt to address the ‘natural man’,

that is, its ideal audience was a purported extra-religious human thinker.

Though it took imagination to invent this character, no one with much

imagination could believe he existed. The philosophical argumentation

which addressed a hypothetical open-minded ‘human’ with no special

religious concerns was a semi-disguised theological apologetic, the reason-

ing a fig-leaf on the faith. Imaginative apologetics has never addressed a

religiously neutral figure. Its breadth consists in addressing human beings

in their aboriginal religiosity. It taps the human sense of wonder, of guilt,

and of the sacrality of certain kinds of things and actions. It spontane-

ously touches on the commonality between Christian ideas and those of

the religions, especially the archaic ones. For instance, when C. S. Lewis

speaks about the natural law, he describes it as the Tao, connecting it to

ancient Chinese religious wisdom.3 It takes imagination to recognize the

human being and his acts and desires as religious. Drawing on Newman’s

theory of a ‘primal revelation’ to all humanity, Tolkien’s Lord of the

Rings creates a cosmos and a combat whose religious dimension is analo-

gous to the Christian cosmos.4 It’s the defining paradox of imaginative

apologetics that, on the one hand, its language and its objects have the

particularity of poetry but, on the other, its reach is broad and diffuse.

By contrast, scientific theology makes commanding generalizations, but

its scope is narrow and precise. Like the prophets, scientific theology

overcomes heathenism and heresy by negation; like the psalmists, imag-

ination overcomes them by infiltration. Its ‘religious’ rather than nar-

rowly ‘theological’ orientation enables imaginative Christian writing to

vault over the apparent ‘subjectivity’ of imaginative thought. It’s the

purported universality of abstract argument which is supposed to make

it superior to imagining. Imaginative apologetics has its own universality,

3. C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (New York: Macmillan, 1947) 28-29.

4. Father Derek Cross of the Toronto Oratory has shown the depth of Newman’s

influence on Tolkien in his unpublished paper, “The Lord of the Rings: A Christian

Fantasy.”

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 148 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 149

that of religion. The apparent drawback of speaking of imaginative apolo-

getics is outweighed by the fact that religion is as much rooted in our

common humanity and as universal as rational argument is.

In this paper, I will first draw a clear line between how ‘Imaginative

Theology’ and Systematic Theology evaluate the imagination. This com-

parison will help us see that imaginative apologetics and Systematic

Theology have more in common with each other than with Theology-

and-Imagination. Thirdly, I say how imaginative apologetics differs from

Systematic Theology. Then I will defend the distinction, drawing on

John Henry Newman’s exposition of the differences between real assent,

on the one hand, and notional assent on the other. Finally, to show that

the distinction is not a demarcation, I will mention the necessary influence

of the realism of imaginative apologetics upon the notions of Systematic

Theology and I will note the point where they coincide, in that discern-

ment of God’s objective self-expression which Newman calls the illative

sense.

II. Where do Systematic Theology and Imaginative Theology

Diverge?

The Prophecy of Ezekiel begins with a vision of the glory of the

Lord:

the heavens were opened and I saw visions of God … I looked, and

behold, a whirlwind was coming out of the north, a great cloud with

raging fire engulfing itself; and brightness was all around it and radi-

ating out of its midst like the color of amber, out of the midst of the

fire … from within it came the likeness of four living creatures …

they had the likeness of a man. Each one had four faces, and each

one had four wings … They sparkled like the color of burnished

bronze … Their wings touched one another. The creatures did not

turn when they went, but each one went straight forward … they

went wherever the spirit wanted to go, … their appearance was like

burning coals of fire, like the appearance of torches going back and

forth among the living creatures. The fire was bright, and out of the

fire went lightning … [And], behold, a wheel was on the earth beside

each living creature with its four faces … The appearance of their

workings was … a wheel in the middle of a wheel … Wherever the

spirit wanted to go, they went, because there the spirit went; and the

wheels were lifted together with them, for the spirit of the living

creatures was in the wheels. When those went, these went; when

those stood, these stood; and when those were lifted up from the

earth, the wheels were lifted up together with them, for the spirit of

the living creatures was in the wheels. And above the firmament over

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 149 6/06/11 13:56

150 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

their heads was the likeness of a throne, … like a sapphire stone; on

the likeness of the throne was a likeness with the appearance of a

man high above it. from the appearance of His waist and upward I

saw … the color of amber with the appearance of fire all around …;

and from the appearance of His waist and downward … the appear-

ance of fire with brightness all around. Like the appearance of a

rainbow in a cloud on a rainy day, so was the appearance of the

brightness all around it. This was the appearance of the likeness of

the glory of the LORD (Ezekiel 1:1-28).

This Biblical passage hits those of an aesthetic sensibility in their

G-spot. For the theological Imaginer, the first chapter of Ezekiel func-

tions like a definition of imagination. The patron saint of Theology-and-

Imagination, Samuel Taylor Coleridge famously wrote of Ezekiel’s

vision:

In the Scriptures there are “the living educts of the imagination; of

that reconciling and mediatory power, which incorporating the reason

in images of the sense, and organising … the flux of the senses by

the … self-circling energies of the reason, gives birth to a system of

symbols … consubstantial with the truths of which they are the con-

ductors. These are the wheels within wheels which Ezekiel beheld,

when … he saw visions of God as he sate … by the river of Chebar:

‘Whithersoever the Spirit was to go, the wheels went, and … the

spirit of the living creature was in the wheels also’” (Ezek 1:20).5

For Coleridge, the imaginative quality of Ezekiel’s vision defines it

as inspired. As he sees it, Imagination is not only a condition but the root

cause of theology. Seeking to prove to Victorian doubters that Scripture

is inspired, Coleridge brings in evidence the similarity between the

revelation in Ezekiel 1 and the process of imagination.

The patron saint of Systematic Theology, Thomas Aquinas, reacted

more drily to such imaginative visions. In his discussion of prophecy, in

the Summa Theologiae, Thomas states that “whatever images are used to

express the prophesied reality is a matter of indifference to prophecy.”6

We would be wrong to leap to the conclusion that Thomas is dismissing

the imagination here. The article is called “The Cause of Prophecy,” and

the question is whether prophecy can be natural. Thomas means that the

cause of prophecy is not Ezekiel’s natural poetic sensibility, it is super-

natural revelation. Thomas is reminding us that the lift-off point for

those wheels in wheels is revelation, a supernatural event, the hand of the

Lord showing Ezekiel a vision.

5. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “The Statesman’s Manual,” Lay Sermons, ed.

R. J. White (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972) 29.

6. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 172, a. 3, reply obj. 1.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 150 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 151

Thomas defines prophecy as a “Supernatural knowledge:” he says

that “prophetic knowledge relates to what naturally surpasses human

knowledge.”7 Those imaginative theologians who don’t like this Sys-

tematician’s intellectualism have sometimes tossed out the baby of the

supernatural with the bathwater of knowledge. Defending imagination

against the claims of knowledge, they sometimes elevate ‘imaginativeness’

into a measure of supernatural origin, effectively making Imagination its

judge. And yet, the more the ‘I’ is majusculed, the more the concrete

content of prophetic vision is replaced with talk about Imagination,

rather than object of theology, God and salvation.

That’s why Thomas treats imagination instrumentally: the phantasm

is a means to an end, an enabling device. Whereas modern Romantics

value the phantasm or the image in and for itself, Thomas values it for

fixing the intellect on a particular object. It is because the things which

thought takes off from are physical that the human intellect needs to be

fed by phantasms to know truth: the “body is necessary for the action

of the intellect, not as its organ of action, but on the part of the object,”

Thomas says, “for the phantasm is to the intellect what colour is to

sight.”8 As Thomas sees it, God shows Ezekiel this luminous vision to

fix his mind on the truth it expresses. What really matters for Thomas

is the judgement which the image or phantasm enables us to make.

A good teacher uses telling examples to convey an idea. If you have a very

fine mental image, like wheels of fire, all the better for the judgement.

So, Thomas says that, sometimes, the “intellectual image in prophetic

revelation … derives from imaginative forms with the help of prophetic

light, because from these same imaginative forms a more delicate truth

becomes apparent in the radiance of a higher light.”9 To enable Ezekiel

to perceive the delicate truth of the glory of the Lord, God presents him

with a splendiferous vision of sparkling wheels within wheels. The principle

is: the object of prophecy matters more than the media.

This pedagogical, functionalist attitude is drawn into statements

Thomas makes about imagination which really are disparaging. Stating

that the “excellence of means is principally assessed from the end,”

Thomas defines the “end of prophecy” as “the manifestation of some

truth which surpasses the faculty of man. The more this manifestation

is effective, the greater is the prophecy to be esteemed … a manifestation

of divine truth which derives from a bare contemplation of the truth

7. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 172, a. 1.

8. Ibid., I, q. 75, a. 2, reply obj. 3.

9. Ibid., I, q. 173, a. 2, reply obj. 2.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 151 6/06/11 13:56

152 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

itself is more effective than that which derives from images of bodily

things. Sheer contemplation is … nearer to the vision of heaven, according

to which truth is gazed upon in the essence of God. So it follows,”

Thomas believes, “that a prophecy which enables some supernatural

truth to be perceived, starkly, in terms of intellective vision, is more to

be prized than that in which supernatural truth is manifested by like-

nesses of bodily things in terms of imaginative vision … a prophet’s mind

is more sublime, even as in human teaching, a pupil is shown to have a

better mind when he can grasp an intellectual truth which the master

puts out without adornment, than the pupil who needs sense-perceptible

examples, to lead him up to that truth.” Adding cold water to pour on

imaginative vision, Thomas concludes that, “prophecy in which intel-

lectual truth is revealed without adornment is superior to all.”10

III. Imagination: Seeing Tragic Downfall and Comedic Elevation

It is disheartening to learn that the amber fire and the rainbow

could have been dispensed with if Ezekiel had been a sharper pupil. But,

unlike the proponent of ‘theological Imagining’, the imaginative apolo-

gist doesn’t instinctively retort that Thomas has lost sight of the value

of the image: rather, holding, with the systematician that it is the super-

natural which is at the root of the vision, he wonders if discarding the

image might endanger our grip on its object. As the apologist sees it, it’s

unrealistic to be preoccupied with the internal operative ideals of systematic

theology itself. Because its best media are concepts, systematics some-

times forgets that the object matters more than the media. “Logicians,”

as Newman says, “are more set upon concluding rightly, than on right

conclusions.” The “simplicity and exactness” which are the great achieve-

ments of every “Science” – and Systematics is theology as science –

prevent science from becoming “the measure of the fact:” “As to Logic,

its chain of conclusions hangs short at both ends” falling “short both of

first principles and of concrete issues.”11 Rising imperiously above the

demands of science, God knows the only way to make Ezekiel encounter

him is with a show of fireworks. What he shows Ezekiel is not just a

‘picture’ of the divine nature, accommodated to Ezekiel’s sensory

apparatus, but a dramatic expression of the firey love of God. For the

10. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 174, a. 2 reply and reply obj. 1.

11. John Henry Newman, An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (Notre Dame,

IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1979) 90 and 225.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 152 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 153

imaginative apologist, what stands out in this passage is not its poetical

character as such, but the fact that its poetry is revelatory of God. The

man on a throne, in the appearance of fire with brightness all around,

makes himself present to the “religious imagination” as a “reality.” On

the other hand, the “theological intellect” sees not so much the reality of

the vision but its “truth.”12 To what Newman calls the “religious imag-

ination,” the poetical qualities bring home the outward reality of the

vision. Because, for the theological scientist, not the reality but the truth

of the vision is at stake, the poetical qualities distract from its truth.

It is as a systematician that Thomas claims that the human thinking

is superior, which can rise above images. Of course he is governed by

theocentric principle, by believing that it is of the nature of God to be

knowable (in part), but unimaginable. But Thomas is also directed and

governed by the demands of science. Thomas states that, “imaginative

vision in prophetic knowledge is not required for its own sake, but for

the manifestation of intellectual truth. So all the more effective is prophecy

when it has less need of imaginative vision.”13 He is talking about the

“effective” quality of the intellectual truth, its clarity. The criterion to

which Thomas appeals is the clarity of intellectual truth, not the unim-

aginability of God. A good workman needs good materials, and the

‘matter’ of systematics is the conceptual judgement. This is where the

paths diverge between systematics and imaginative apologetics. The

concept is clearer and so, for Thomas, truthier than the image, or

“adornment.” It is therefore the concept and not the image which is the

building block of systematic theology. Thomas’ attitude is exemplary of

his style of theology: Barth, Rahner and Calvin would agree with

Thomas that the building blocks of systematic theology are conceptual

judgements. Because they are not images, they are not experiences. The

medium of the concept is the best way to harness the intellectual content

of theology.

The encounter between God and Ezekiel seems unprovoked. Prophetic

ecstasy, Thomas tells us, inflicts a certain violence: “That a man should

be so uplifted by God is not against nature, but above the capacities of

nature.”14 One reason why science must distrust the human imagination

is that the “vivid and forcible” character of our images can mislead us,

that is, lead us away from truth. Subjectively overwhelming, they can be

objectively mistaken. Newman was perhaps thinking of this subjective

12. Newman, Grammar, 93.

13. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 174, a. 2 reply obj. 2.

14. Ibid., I, q. 175, a. 1 reply obj. 2.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 153 6/06/11 13:56

154 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

quality of imagination when he had inscribed, over the archway leading

into the Birmingham Oratory, Augustine’s maxim, Ex umbris et imag-

inibus in Veritas – out of shadows and images into truth. On the one hand,

religious imagination gives real assent, that is, assent to realities, in their

singularity and personified character, but, on the other, the strength of

the assent is not necessarily in proportion to the truth of the object. Real

assent, or religious conviction can prove false: real assents, Newman says

with fine irony, “have given form to the medieval theocracy and to the

Mahometan superstition; they are now the life both of ‘Holy Russia’,

and of that freedom of speech and action which is the special boast of

Englishmen.”15

Newman thought that, by its constant efforts to expiate the anger

of God or the gods, ‘natural religion’ exhibits a “sense of sin and guilt.”16

Emerging rather unexpectedly, near the close of The Grammar of Assent,

Newman’s claims about ‘natural religion’ can seem just too easy – we

know how the ‘problem’ of ‘natural religion’ is going to be solved!

Armed with Christian revelation, of course Newman, unlike Casaubon,

never had to spend a lifetime fruitlessly seeking the key to all mytholo-

gies! The investigation was over before it began. Certainly, it was super-

natural revelation which put the key in Newman’s hand, but the door

did not open until that key had generated an act of imagination into the

violent and bloody sacrifices of the people the Victorians called ‘primi-

tives’, and into their spontaneous fearfulness about their gods, their

dread and awe before the sacred. Resting in revelation, Newman could

imagine the crude sacrifices of archaic peoples, their felt need to propitiate

the gods, as a visceral acknowledgement that humanity has slipped into

a tragic predicament. Unlike the Victorian reductionist ‘keys’ to the

primitive animisms which supposedly gave rise to monotheism, New-

man doesn’t see through heathen religions; imagining is the opposite act

to that of seeing through. The great shadow which he sees upon primi-

tive propitiation of the gods falls from the Cross.

Rather than seeing through incongruous particulars, imaginative

apologetics comes to a stop before their poetic quality, like seeing the

glory of the Lord among the captives by the River Chebar. Taking the

particularity of revelation literally can make it sound comedic, as when

Walker Percy wrote that,

Judaism … is a preposterous religion. It proposes as a serious claim

to truth … that a God exists as a spirit separate from us, that he made

15. Newman, Grammar, 86.

16. Ibid., 311.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 154 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 155

the Cosmos from nothing, that he made man … that man suffered

a fall or catastrophe, and that as a consequence God entered into a

unique covenant with one of the most insignificant tribes on one of

the most insignificant planets of one of the most insignificant of the

100 billion stars … of the Cosmos. Protestant Christianity is even

more preposterous … It proposes not only all of the above but fur-

ther that God himself … appeared as a man … at a … certain place

in history, that he came to save us from our sins, that he was killed,

lay in a tomb for three days, and was raised from the dead, and that

the salvation of man depends on his hearing the news of this event

and believing it! Catholic Christianity is the most preposterous of

the three. It proposes, not only all of the above, but also that the

man-god founded a church, appointed as its first head a … pusil-

lanimous person, like himself a Jew, the most fallible of his friends,

gave him and his successors the power to loose and to bind, required

of his followers that they eat his body and drink his blood in order

to have life in them, empowered his priests to change bread and wine

into his body and blood, and vowed to protect this institution until

the end of time. At which time he promised to return.”17

As the imaginative apologist sees it, this litany of absurdities some-

how resonates with the religious mind: just because of its sense of the

tragic state of humanity, the only key to human self-understanding is

the comedy of Christ and his creation, the Church.

The imaginative apologist interprets the natural, religious intuition

of human fallenness, in religious rather than theological terms, that is,

as a concrete experience of a tragic state. The imaginative apologist rec-

ognizes that, to be lifted up as Ezekiel was is contrary to the proclivities

of fallen human nature: “We are unable not to want truth and happi-

ness,” Pascal tells us, “and are incapable of either … This desire has been

left in us as much to punish us as to make us realize what we are fallen

from.” Here Pascal speaks to the human religious instinct, which recog-

nizes itself as enigmatically, unaccountably out of sorts with the Tao.

Highly intelligent fallen people can become fixated by images. Here

abstract argument may be of little avail: as Thomas Swift is supposed to

have said, you cannot reason a man out of a position he did not reason

himself in to. Just as the fallen imagination can be misled as to the truth

of its images, so the fallen intellect can mistake their reality. And some-

times, only a re-imagining the position from another perspective can help

one past the mental blocks set up by the intellect. A case in point is the

modern ‘Whig Scientist’ idea that the mediaevals thought our world was

at the centre of the Universe. It took an imaginative apologist to blow

17. Walker Percy, Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (New York: Farrar,

Straus, and Giroux, 1983) 252-253.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 155 6/06/11 13:56

156 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

the lid on the purported religious comforts of ‘geocentric astronomy’:

“You must go out on a dark night,” Lewis says, “and walk about …

trying to see the sky in terms of the old cosmology … you now have an

absolute Up and Down. The Earth is really the centre, really the lowest

place; movement to it from whatever direction is downward movement

… the medieval universe … was … unambiguously finite. And one …

result of this is to make the smallness of Earth more vividly felt.”18 The

imaginative apologist loves the incongruous ‘smallness’ of the earth.

That’s why he laughs at – it’s personable.

IV. Imaginative Apologetics is Experiential,

Systematic Theology Scientific

Ezekiel himself is part of the image in the prophetic vision. The

prophet is not shy about putting himself in the story:

On the fifth day of the month, … in the fifth year of King Jehoiachin’s

captivity, the word of the LORD came expressly to Ezekiel the priest,

the son of Buzi, in the land of the Chaldeans by the River Chebar;

and the hand of the LORD was upon him there (Ezek 1:2-3).

No scientist would put it like that, and no systematic theologian:

what the systematician wants is the truth conveyed by this vision, not

Ezekiel’s seeing of it. For the systematician, the presence of Ezekiel is an

ornamental anecdote, which helps dim people remember it, but has no

share in the intellectual truth it conveys. For the imaginative apologist,

the personal witness is important: the singular personality of the super-

natural object of the vision is shaped to speak through the personal wit-

ness of the prophet to the individual heart. Whether in God or in human

beings, the person has a finality: it brings the imagination to a halt. Real

or religious assent has a “personal character” because its objects are the

subjects of the Christian Scriptures and Creeds taken as singulars, that

is, arrayed by the imagination not as ‘dissolved’ into a system, not in

their scientific relations, but as images whose solid literality arrests the

mind. This literality is a kind of finality: the four living creatures do not,

for the religious imagination, stand for a higher idea common to them

and other theological notions. There just are living creatures, four of

them, each with four wings. The literalism which locks the fallen mind

18. C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance

Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964) 98-99.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 156 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 157

into misconceptions lifts the “theology of a religious imagination”19 up

above the capacities of its fallen nature. Imaginative apologetics absolu-

tizes the image because it is supernaturally given. Such apologetic is thus

genuinely theological, that is, not an uninformed imaginative guess, not

mistaken in its object; but it is not Systematic.

The point of divergence between any Systematic Theology and

imaginative apologetics is not over God’s nature: both agree that God is

supernatural. The difference is that Systematics is scientific, an inte-

grated, law-abiding system, and so must distance itself from experience.

Etienne Gilson noted that, so as “to constitute theology as a science,

saint Thomas had to objectivize it completely, that is to say, radically

detach it from the subjectivity of concrete spiritual lives, for it shall no

longer tell a story, but formulate laws.”20 At the outset of the Summa

Theologiae, Thomas states that sacra doctrina “is speculative rather than

practical, because it is more concerned with divine things than with

human acts; though it does treat of these latter, inasmuch as man is

ordained by them to the perfect knowledge of God.”21 Though Thomas

admits practical human acts into systematic theology, he is thinking of

human acts so far as they express human nature in its universal, concep-

tually knowable form: he thinks that theology is a “science of salvation,”

a practical science, but of salvation “in general. He does not conceive of

“theology as the instrument of salvation for each man in particular.” So,

not only the experience of Ezekiel, but Thomas’ own spiritual experience,

is rigorously excluded.22

Gilson pinpoints this contrast when he compares Aquinas and Bon-

aventure: Aquinas “conceived theology as a wisdom which will be the

highest form of knowledge,” whereas Bonaventure, “preferred the theology

conceived as a wisdom which would be the summit of an experience: scire

enim et non gustare nihil valet”23 – it is useless to know and not to taste.

As a typical imaginative apologist, Bonaventure wishes to taste Ezekiel’s

imaginative experience, and writes in order to communicate the taste of

the supernatural – so that his reader will eat and drink for himself. The

religious apologist is an “experimentalist” by calling. “Singular nouns,”

Newman says, derive from “experience.” Imaginative apologetics treats

each of the Scriptural scenes and the Credal articles as separately ‘final’,

19. Newman, Grammar, 82 and 106.

20. Étienne Gilson, “Le Christianisme et la tradition philosophique,” Revue des

Sciences Philosophiques et Theologiques 30 (1941) 249-266, p. 262.

21. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 1, art 4.

22. Gilson, “Le Christianisme,” 263.

23. Ibid.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 157 6/06/11 13:56

158 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

because we do not experience them as abstracted from their particularity.

Viewed in their truth, that is, taken as “common” nouns, and in “abstrac-

tion” from real experience, the Scriptural and Credal descriptions of God

and the divine life can be related, and their concreteness can be con-

sumed by their commonality, that is, by what the separate scenes and

articles have in common.24

A typical form of imaginative apologetics is the dramatic story. This

is not because it ascribes a special value to images, in the sense of sup-

plying fine exhibitions of the poetical trade. The book of Revelation is

packed with striking images, but they are more arresting than they are

aesthetic. The quality of the Greek is acknowledged as weak, even by the

low standard which classicists ascribe to Koine. “‘But look at their books

of devotion’, insisted Carlton,” pressing the aesthetic disadvantages of

Papistry upon the hero of Loss and Gain: “‘they can’t write English’.

Reding smiled at Carlton, … while he said, ‘they write English, I sup-

pose, as classically as St. John writes Greek’.”25 Imaginative apologetics

looks to drama not because it’s well-written but because it is the best

form in which to express the series of conversions and relapses in which

the concrete human being travels toward God. The drama captures

human beings in their actions. The scientific “theology of saint Thomas

has naturally sought its perfect expression in a Summa, whilst that of

saint Bonaventure came into its own in an Itinerary. On one side a tableau,

on the other side the story of a voyage.”26 From this perspective,

Augustine of Hippo is the patron saint of religious apologetics. The

imaginative apparatus which Augustine uses is fairly simple: the tale of

the pear theft or the child in the garden might have been more subtly

portrayed by the great literary artists of the Western tradition. Although

Augustine confesses to having been initially put off by its low brow quality,

his own writing has more in common with Scripture than with the

polished perfection of Tacitus’ Annals or Plotinus Enneads. How Augustine

tells the story can be aesthetically crude. What sticks in the mind is not

that, but the voyage, Augustine’s journey to faith. The non-brainy reader

identifies with the fact that an ‘I’ is the narrator, a chap we can love or

hate. One can also appreciate that the “God Augustine wants to know

is one to whom the soul can say Thou.”27 Using cartoon-like images,

likes the child chanting, ‘take it and read it’, Augustine describes his

particular experience so starkly that it becomes universal.

24. Newman, Grammar, 37-38.

25. Newman, Loss and Gain, 211.

26. Gilson, “Le Christianisme,” 264.

27. Ibid., 260.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 158 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 159

That no single experience is universal is a problem only in name.

Ever since Coleridge, Theology-and-Imagination has been stuck with a

misplaced contrast between “Allegory,” considered merely to “trans-

lat[e] … abstract notions into a picture-language” and “Symbol,” said to

capture the “Special in the Individual.”28 When we say that philosophy

goes from the universal to the particular, but poetry from the particu-

lar to the universal, we neglect the incurable egotism of poets. Imagina-

tive apologetics often begins from experiencing one’s own, individual

state as Allegorical. The poetic soul senses the massive, stark exemplarity

of her experience long before she notice its individuality or uniqueness.

The imaginative apologist exaggerates a single feature of human phe-

nomenology to larger than single life proportions. The first thing

the imaginative apologist feels about his experience is its universal, rep-

resentative applicability, its being an expression of something bigger.

By dint of his faith in their expressive quality, he makes his own eccentric

exploits, fears, crimes and misdemeanours recognizable.

Blaise Pascal appreciated that the human being is a creature of

imagination, or what he calls “whim,” who “hate[s] someone who croaks

or who breathes heavily while eating.” Because we are dominated by

imagination, trying to know “truth and morality” is like trying to see

“pictures” which are always “too far off, or … too close up” when “there

is only one indivisible point which is the right position.” Likewise in

attempting to know one self, no one can “know on what level to put

himself.” The experiential fact that we wish to know ourselves and our

destiny is recognizable: it is an untoward reminder that each one of “is

obviously lost and has fallen from his true place without being able to

find it again,” searching for it “everywhere restlessly and unsuccessfully

in impenetrable darkness.” Imagination in its fallen state is a form of

concupiscence. And yet, Pascal claims, “God has granted faith” to the

human heart. It is the heart which loves the images of Scripture. Pascal’s

imaginative apologetic describes the drama of the individual human soul

fruitlessly searching for happiness and self-knowledge because it lacks the

heart to recognize that “it is only through Jesus Christ that we know

ourselves. We know life and death only through Jesus Christ.”29 The

only evidence leading to Christ Pascal admits is prophecy. It is illogical

to conceive a lost soul chancing upon Ezekiel and taking him as a guide.

But, reality and history are packed with conceptual plot-flaws, and the

likeness of a man on a heavenly throne is a torch by which imagination

28. Coleridge, “The Statesman’s Manual,” 30.

29. Pascal, Pensées, # 228, 55, 142 and 36.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 159 6/06/11 13:56

160 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

has navigated through human perplexity. The Augustinian conceives the

supernatural exemplar of apologetics as having a human face. The ‘some-

thing bigger’ it feels in its experience is the divine call. It senses the

drama of its own experience as a reflection and expression of God’s

action.

Augustine’s City of God begins with ten books of knock-about

polemics against the poetics of the classical world. The author has a

crude fascination with the double-entendres hidden in Hebrew words,

leading the reader into discursions upon the Biblical ‘puns’ whose length

seems to be disproportionate to their weight. So one might hesitate to

present him as the patron saint of imaginative apologetics. Augustine’s

point is that no earthly community has been able to supply the eternal

happiness that we desire. He makes it by recounting a drama. He tells

the drama of human history, entwining within it two supersized pro-

tagonists, the city of man and the city of God. For, “Augustine reduces

the world’s history to the history of sin and grace because he thinks of

the cosmic drama in terms of that enacted within his own soul.” He does

not address himself to ‘humanity’ in the abstract but to human beings

as they concretely and historically have been and are.30 Conceptually

speaking, this way of doing theology is a mess, unclear and untidy.

It can only be absorbed into the Summas and Church Dogmatics after a

systematic clean up in which all the things which are set down in the

contingent sequence of human history are re-located into an abstract but

lawlike and generalisable sequence of ideas. In place of the vulgar prolif-

eration of words and puns, the “characteristic talent” of “syllogistic rea-

soning” is, Newman says, “to have starved each term down till it has

become the ghost of itself, and everywhere one and the same ghost… so

that it may stand for just one unreal aspect of the concrete thing to

which it properly belongs.”31

V. Imaginative Apologetics Sneaks Under Abstract Categories

(like Morality)

C. S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity tries to outline the voyage in a

sequence of graphic and intelligible thought-pictures. Scene One: we

appeal to right and wrong when we argue, and yet we do not ourselves

30. Étienne Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of Saint Augustine, trans. L. E. M. Lynch

(London: Victor Golancz, 1961) 238-240.

31. Newman, Grammar, 214-215.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 160 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 161

act as we expect others to do. People “know the Law of Nature; they

break it.” Scene Two: each of us is given a choice between a materialist

view of the universe and a religious one: the materialist view can’t explain

the moral laws to which we appeal, since “you can hardly imagine a bit

of matter giving instructions” on morality. Scene Three: Christianity

thinks that nature is something “God ‘made up out of His head’ as a

man makes up a story. But it also thinks … many things have gone

wrong with the world.” Scene Four: a power made by God has gone

over to the “dark” side, so that the universe is “Enemy-occupied terri-

tory.” “Christianity is the story of how the rightful king has … landed

in disguise.” Scene Five: God selects “a particular people and spent sev-

eral centuries hammering into their heads … that He cared about right

conduct.” One of them “turns up” “talking as if he were God:” and we

must decide whether to think he was “a lunatic” or “a fiend” or “what

He said.”32

Some would say that the choices presented in each Act have colour-

less clarity. Pascal did not imagine that an apologist clamouring with

graphic moral alternatives would help anyone who awakes without much

recollection of how he got into this predicament: “All very well to shout

out to someone who does not know himself to make his own way to

God!” he says, sarcastically. Though Lewis tells a ‘supernatural story’,

some may feel he has in this instance forgotten that it takes a super-

natural fire to show us that wherever we are now standing in the drama

of salvation cannot be “the state of your creation.”33 The drama of the

voyage excites curiosity because something more archaic than the moral

is at stake. Imaginative apologetics has to go below the category of the

moral to the religious, the holy and unholy, to become genuinely dra-

matic. Then it reminds us of the enigmatic character of our lives by

showing us God in the enigmatic appearance of a rainbow in a cloud on

a rainy day.

Imaginative apologetics is much simpler than a messy variant on

systematic theology. The great imaginative apologists have composed

enduringly popular works which have assisted in the conversion of

untold numbers of people. I’m thinking not only of Lewis’ children’s

books but also of books like Scott Hahn’s The Supper of the Lamb, with

its continuous stream of terrible puns. The book opens with the story of

the author going by chance into a Catholic mass and seeing the book of

32. C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, revised edition (London: Harper Collins,

1952) 2002, pp. 8, 25, 50 and 53.

33. Pascal, Pensées, # 174 and 182.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 161 6/06/11 13:56

162 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

Revelation played live before his eyes, like Ezekiel’s vision. Hahn recog-

nized the book of Revelation in the Mass. Imaginative apologetics are

works of very concrete example and testimony, graphic dramas which

slide under the categories of the intellect, and awaken a sense of recogni-

tion. The apologist is seeking to make the supernatural recognizable to

the religious mind, seeking to make it remember of what its experience

is the Allegory. A primary dimension of such apologetics is the conver-

sion story. A secondary dimension would bring out the religious qualities

of artistic works. For instance, it would take a work like the Coen Brothers’

version of No Country for Old Men, and show how the evil depicted in

the film is extreme to the extent of transcendence, and name the enigma

with the religious word, demonic.34 Such secondary apologetics appears

on Robert Barron’s Word on Fire site, where he presents youtube videos

on recent movies.35 Imaginative apologetics isn’t trying to substitute for

systematics: it comes in long before anyone is ready for systematics. And

long after.

VI. Accentuate the Positive

In the first chapter of Ezekiel, the prophet uses the term ‘like’

twenty three times, and ‘appearance’ seventeen. The great advantage of

apologetics in making the supernatural recognizable is its imitation of

this license to say that one thing is like another. C. S. Lewis presses this

advantage when he makes fun of the ‘negative’ theology which has such

a grip on the imaginations of unimaginative theologians:

Let us suppose a mystical limpet, a sage among limpets, who (rapt

in vision) catches a glimpse of what Man is like. In reporting it to

his disciples, who have some vision themselves … will have to use

many negatives. He will have to tell them that Man has no shell, is

not attached to a rock, is not surrounded by water. And his disciples,

having a little vision of their own to help them, do get some idea of

Man. But then there come erudite limpets, limpets who write histo-

ries of philosophy and give lectures on comparative religion, and

who have never had any vision of their own. What they get out of

the prophetic limpet’s words is simply and solely the negatives. From

these, uncorrected by any positive insight, they build up a picture of

Man as a sort of amorphous jelly (he has no shell) existing nowhere

in particular (he is not attached to a rock) and never taking nourishment

34. I am thinking of Christian Badeaux’s “Fear, Faith and Cormack McCarthy,”

on http://www.civitate.org/2009/01/faith-fear-cormac-mccarthy/.

35. http://www.youtube.com/user/wordonfirevideo.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 162 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 163

(there is no water to drift it towards him). And having a traditional

reverence for Man they conclude that to be a famished jelly in a

dimensionless void is the supreme mode of existence, and reject as

crude, materialistic superstition any doctrine which would attribute

to Man a definite shape, a structure, and organs.36

Any good systematician knows that the Danger! High Voltage!

signs are there to preserve the greater Positive reality of God, but few

systematicians dare to go so far as Ezekiel’s circumspect, likeness of the

appearance of a man. Because he treats of God as a “complex whole,”

known in many diverse propositions, the Systematician assents to God

as a “mystery:”37 the approach to knowing God through notions is orien-

tated to apophasis. The supernaturally inspired Ezekiel can enter the

cataphatic mode, because he’s been clouted with expressive Energy and

Movement, and casts it in the image of spirits moving in wheels.

Scripture expresses God’s nature, working top down, from exemplar

to particular vision. Following in Scripture’s footsteps works as apolo-

getics, because its top-down movement reflects the shape of human

remembering.

So, Lewis can tackle head-on the pre-theoretical and imaginative

road-block which most moderns come up against in relation to God:

our imagination supplies us with two conceivable ideas of God, either

the material ‘Sky-fairy’ of atheist apologetics or a “jelly in a dimension-

less void,” God as the soul of Science. Supernatural revelation requires

us to manoeuvre around these imaginative obstacles. Lewis isn’t meeting

imagination on its own ground, but using supernatural imagination to

rise above the forms natural human imagining takes. Inspired by the

Christian teaching about the drama of salvation, Lewis uses imagination

to help his reader move around the obstacles which pictorial imagination

presents to faith. He knows that the hindrance to making Christian faith

recognizable is the imaginative homage to ‘God the essence of Science’

paid by Alexander Pope’s “maxim: ‘the first Almighty Cause/ Acts not

by partial, but by general laws’.” Unafraid of theological anthropomor-

phism, Lewis claims that, when God responds to human prayer, the

“Person” in God “meets those who can … face it. He speaks as ‘I’ when

we truly call Him ‘Thou’.” Lewis realizes that speaking like this creates

problems about divine impassibility. He thinks we must “admit that

Scripture doesn’t take the slightest paints to guard the doctrine of Divine

Impassibility” – a God who forgives our sins reacts to us, just as much as

36. C. S. Lewis, Miracles (London: Collins, 1947) 93.

37. Newman, Grammar, 115.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 163 6/06/11 13:56

164 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

a God who answers our prayers. Pascal thought of prayer as God’s way

of enabling humans to be causes. But Lewis prefers his experiential image

of God meeting the petitioner, because, he says, “for our spiritual life as

a whole, the ‘being taken into account’, or ‘considered’, matters more

than the being granted. Religious people don’t talk about the ‘results’ of

prayer; they talk about its being ‘answered’ or ‘heard’.”38

VII. The Real and the Notional

There are limitations and defects in the theological practice of

imaginative writers. Many have voiced doubts about the orthodoxy of

Lewis’ Christology, and Pascal stands accused of Jansenism. The thought

of applying their phenomenological approach to the centre-piece of sys-

tematics, Trinitarian theology, gives some people nightmares.39 Ian Kerr

has deployed such rigorous scholarship on Chesterton’s remarks about

Gethsemane in Orthodoxy that only a fool would rush in where lesser

scholars should fear to tread. But, I happen to have used the same cita-

tion which Fr. Kerr unpacks so well as the frontispiece to a chapter on

the Trinity in a recent publication, so I hope to be excused for glancing

at it too. We know that, according to Newman, ‘natural religion’

expresses the human need for atonement in its rites of “sacrifice:” he

finds in this a ley-line leading to the Cross. Newman tells us that, “Nat-

ural religion is based upon the sense of sin; it recognizes the disease, but

cannot find, it does but look out for the remedy. That remedy, both for

guilt and for moral impotence, is found in the central doctrine of Rev-

elation, the Mediation of Christ.”40 If one applied the phenomenological

approach which Newman has taken to ‘natural religion’ to the Event

which heals the predicament of humanity, one will envisage the cruci-

fixion of Christ as the final act in a tragedy, and partaking of the tragic

character of all sacrificial rite. “In that terrific tale of the Passion there is

a distinct emotional suggestion,” Chesterton says, “that the author of all

things (in some unthinkable way) went not only through agony, but

through doubt. It is written, ‘Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God’.

No; but the Lord thy God may tempt Himself; and it seems as if this

38. C. S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (London: Geoffrey Bles,

1963, 1964) 73-75.

39. Paul S. Fiddes expresses doubts about Lewis’ grasp of Trinitarian Theology in

“C. S. Lewis The Myth Maker,” A Christian for All Christians: Essays in Honour of C. S. Lewis,

ed. Andrew Walker and James Patrick (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1990).

40. Newman, Grammar, 315 and 375.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 164 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 165

was what happened in Gethsemane. In a garden Satan tempted man:

and in a garden God tempted God. He passed in some superhuman

manner through our human horror of pessimism. When the world

shook and the sun was wiped out of heaven, it was not at the crucifixion,

but at the cry from the cross: the cry which confessed that God was

forsaken of God … let the atheists themselves choose a God. They will

find only one divinity who ever uttered their isolation; only one religion

in which God for an instant seemed to be an atheist.”41 Taken as sys-

tematic theology, this is utterly hair-raising. If Chesterton hadn’t been

canonized in the sensus fidelium, systematicians would be writing PhD

dissertations on his Tritheism. Chesterton has taken the “cry” from the

Cross in its literality, not as a notional idea to be modified in relation to

other ideas which we know to be true about God (such as that God is

non-material and impassible), but in its real, ‘singular’, finality. He is

trying to approach, not the whole truth of God, which is a ‘mystery’

only to be tackled by the systematician, according to Newman, but at

one, singular ‘moment’ in God’s being. All this could be deemed the

result of failing to see that, “all the more effective is prophecy when it

has less need of imaginative vision.”42 And yet, systematicians turn a

blind eye to the dangerous Origenism of Lewis, Tolkien, and Chesterton:

the good ones love the stuff, and know they need it. What Chesterton

gives us here is not Systematics, but the results of long “meditation on

the Sacred Text:” for, as Newman says, the “purpose … of meditation is

to realize” the “Divine Word” in the “Gospels,” that is “to make the facts

which they relate stand out before our minds as objects, such as may be

appropriated by a faith as living in the imagination which apprehends

them.” Since “theology has to do with the Dogma of the Holy Trinity

as a whole made up of many propositions,” to it, the persons of the

Trinity act as one; on the other hand, Chesterton approaches it from the

imaginative standpoint of “religion” which “has to do with each of those

separate propositions which compose it.” He meditates upon the acts of

the persons of the Trinity in their literal ‘finality’: “Religion has to do

with the real, and the real is the particular.”43

41. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (London: William Clowes, 1908) 254-255.

42. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 174, a. 2 reply obj. 2.

43. Newman, Grammar, 77 and 122.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 165 6/06/11 13:56

166 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

VIII. Closer to Scripture

Systematics goes on further than imaginative apologetics, and cov-

ers territories which are beyond the reach of imaginative thinking – such

as spelling out the logic of the relations of the persons in the Trinity: it

“forms and protects them by virtue of its function of regarding them,

not merely one by one, but as a system of truth.”44 In that sense, imag-

inative apologetics is a preamble to Systematics, that is, literally subordi-

nate to it. In another way, Systematics looks to imaginative apologetics as

an ever necessary partner. I have given two reasons why. Systematics is

written for systematicians, whereas apologetics has an outward orienta-

tion. Logically, a book focussed on some chap’s experiences should only

be of interest to him, and appeal to ‘experience’ is a subjectivising

manoeuvre within systematic theology. But, the imaginative apologist

conceives of his experiences, like that of prayer, as expressing the move-

ment of God toward the human soul: he primarily views them as

archtypical, rooted in what God is, and only secondarily as his own

experiences. So, in reality, the confessional and experiential writings of

Augustine and Bonaventure, and the spiritual biographies, like Surprised

by Joy are the books which convert people to Christianity. Like the

madeleine, they make us remember the taste of the self, tasting God. In

the second place, systematics has a certain inclination to developing an

inward looking focus on its own conceptual method. It can start to

substitute its own method and way of thinking about God for God’s

self-revelation. It can slide into thinking that supernaturality equates

with the same abstraction from materiality which characterises the con-

ceptual judgement. But, in Scripture and salvation history, supernatural

revelation is concrete and dramatic. It is filled with the incongruities of

personal experience. In Scripture, God writes crooked, in straight lines.

The imaginative apologist is dim enough to take this literally. Because

its vulgar form is closer to the form of the supernatural cause of theo-

logical knowledge, that is, closer to Biblical revelation, imaginative apol-

ogetics reminds systematics that looking ‘upward’ to God is not gazing

toward a “dimensionless void.”

44. Newman, Grammar, 122.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 166 6/06/11 13:56

IN DEFENCE OF IMAGINATIVE APOLOGETICS 167

IX. Expression: The Illative Sense

I want to conclude by briefly noting what Systematics, Imaginative

Apologetics and Theological Imagining have in common. It is, on the

one hand, objectively speaking, a cosmos and salvation history which

expresses the mind and the purpose of God, and, subjectively speaking,

the use of what Newman called the ‘illative sense’ to discern the chief

markers of God’s self-expression in cosmos and history. Coleridge says

that it is because Scripture speaks in “symbols consubstantial with the

truths of which they are the conductors” that “the Sacred Book is wor-

thily entitled the Word of God.”45 Coleridge’s idea of the image as “con-

substantial” with the truth it conveys means that the image really

expresses its truth; the medium is the message. Augustine, and, following

him, Bonaventure, speak of the cosmos as the expression of the divine

Creator. A truth is expressive when the message positively exudes its

medium. Thomas Aquinas does not use the idea of expression in his

Trinitarian theology. But he does use it in relation to prophecy. He

thinks that, if a prophet is merely granted a vision (instead of words,

which are clearer), the “prophecy is the more lofty the more the signs

are expressive: as when Jeremiah saw the burning of the city under the

similitude of a boiling pot.”46 A systematic theologian could agree with

the contemporary disciple of Coleridge, that Ezekiel’s vision of wheels

of fire is telling because it’s expressive.

The illative sense is the ability to read things as expressions, gener-

alizing from many particular sensations and experiences to what they

represent, and not only to what they represent to us, but to what they

tell us about reality. So, for instance, Newman thought the repeated

experience of conscience is taught by the illative sense to read that expe-

rience as telling of a Judge. The illative sense works from “perceptions”

to realities known as truths. The illative sense is a medium between

experience and truth, between the ‘real’ and the ‘notional’. As we saw,

real assent is “forcible” but can be mistaken as to the truth of the objects

to which it spontaneously gives credence; notional assent is logical, but

can refer only to “ghosts of notions.” Here’s where both systematics and

imaginative apologetics need to be guided by an illative sense. There is

no “party wall” between real and notional assent, because what it means

to say that “every religious man is to a certain extent a theologian, and

no theology can … thrive without the initiative and abiding presence of

45. Coleridge, “The Statesman’s Manual,” 29.

46. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 174, a. 3.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 167 6/06/11 13:56

168 FRANCESCA ARAN MURPHY

religion” is that Christian thinkers are united in their reliance upon an

illative sense which perceives things and language as expressive of the

mind of the Maker. However much Thomas may distance himself from

experience, the inner beauty of the Summa, its aesthetic feeling for the

‘congruities’ of salvation history, could only derive from the exercise of

an ‘illative sense’ upon the object of theology. Newman tells us, “He

who has once detected in his conscience the outline of a Lawgiver and

Judge, needs no definition of Him, whom he dimly but surely contem-

plates there, and he rejects the mechanism of logic, which cannot con-

tain in its grasp matters so real and so recondite. Such a one … is able

to pronounce about the great Sight which encompasses him, as about

some visible object; and, in his investigation of the Divine Attributes, is

not inferring abstraction from abstraction, but noting down the aspects

and phases of the one thing on which he is ever gazing.”47 As different

as Systematic Theology and Imaginative Apologetics are, that seems as

good a description of St. Thomas at work as Chesterton ever gave; it is

difficult to conceive of the writings of Augustine, Bonaventure, Pascal,

Lewis or Newman himself as having emerged from anything other than

such a “great Sight.”

Francesca A. Murphy is Reader in Systematic Theology in the Department of

Divinity and Religious Studies of the University of Aberdeen, Scotland. Address:

School of Divinity, History and Philosophy, King’s College, University of

Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UB. E-mail: f.a.murphy@abdn.ac.uk.

47. Newman, Grammar, 97, 93 and 250.

94434_LouvainStudies_2009-2_02.indd 168 6/06/11 13:56

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)