Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J Geriatr Cardiol 2020 17 7 441-6

J Geriatr Cardiol 2020 17 7 441-6

Uploaded by

Fernando SousaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J Geriatr Cardiol 2020 17 7 441-6

J Geriatr Cardiol 2020 17 7 441-6

Uploaded by

Fernando SousaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology (2020) 17: 441446

©2020 JGC All rights reserved; www.jgc301.com

Letter to the Editor

Open Access

Measuring frailty in patients with severe aortic stenosis: a comparison of

the edmonton frail scale with modified fried frailty assessment in patients

undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Francisco J Romeo1,#, Maximiliano Smietniansky2, Mariela Cal2, Cristian Garmendia1, Juan M Valle Raleigh1,

Ignacio M. Seropian1, Mariano Falconi3, Pablo Oberti3, Vadim Kotowicz4, Carla R. Agatiello1,

Daniel H Berrocal1

1

Division of Interventional Cardiology, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2

Division of Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

3

Division Cardiology, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

4

Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

J Geriatr Cardiol 2020; 17: 441446. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2020.07.001

Keywords: Aortic stenosis; Frailty; Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Frailty is generally defined as a clinical syndrome of de- ment (‘timed up and go’) were recently described in a small

creased physiologic reserve which drives to increased vul- cohort of TAVR patients identifying patients likely to ex-

nerability and susceptibility to different stressors together perience longer hospital stays.[12] The aim of this clinical

with poor recovery to homeostasis.[1] The relevance of frailty experience sought to compare the prevalence of frailty using

status in a wide range of prospective cohorts is mostly re- the two scales, and agreement between them.

lated to an increasing burden in both mortality, hospital re- A retrospective analysis of 128 patients who underwent

admissions, disability, and falls.[ 2,3] TAVR at an Argentinean academic hospital from July 2014

In aortic stenosis (AS) population, the spectrum of frail to July 2018 was performed. All patients met criteria for

patients significantly differs according to which frailty scale severe AS defined by the American College of Cardiol-

is used. Scales such as Rockwood Frailty Index,[4] Canadian ogy/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice

Study of Health and Aging,[5] Katz ADL,[6] 6 min walk Guidelines.[13]

test,[7] up and go,[8] gait speed[9] have been described for im- Ours is a tertiary care academic medical center in which

proving risk stratification in transcatheter aortic valve repla- all possible pre-TAVR candidates are discussed by a mul-

cement (TAVR) patients alone or in combination. More than tidisciplinary heart valve team (cardiac surgeons, interven-

25 subjective or objective frailty markers have been devel- tional cardiologists, cardiologists specialized in multimodal-

oped but because of a lack of consensus, there is variability ity imaging and geriatricians) on a weekly basis.

among studies and confusion about which marker to use. Final decisions regarding TAVR, surgical aortic valve

The Modified Fried Frailty Assessment (MFFA) has replacement (SAVR) or futility patients are integrated into a

been widely validated in different clinical scenarios and, in core clinical discussion with frailty assessments, pre-TAVR

TAVR, has shown incremental prognostic value for func- multislice computed tomography (MSCT) measurements,

tional decline including discharge to a rehabilitation facility cardiac biomarkers, and echocardiographic data.

after TAVR[10] and 1-year mortality.[4–11] Patient comorbidities were collected using the definitions

However, the assessment involves five domains and re- provided by the STS data collection system.[14]

quires special equipment, though hard to apply in clinical Frailty status was assessed by seven trained geriatricians

practice for cardiologists involved in the care of valvular using a MFFA which incorporated five domains of frailty:

patients. unintentional weight loss, exhaustion, muscle weakness,

The Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS), a simple frail assess- slowness while walking and low levels of activity. Each

ment that involves 10 questions and one physical assess- domain was scored individually in a binary fashion as nor-

mal or summed to generate a frailty score. We classified

#

Correspondence to: francisco.romeo@hospitalitaliano.org.ar patients with a frailty score of ≥ 3/5 as frail, whereas those

http://www.jgc301.com; jgc@jgc301.com | Journal of Geriatric Cardiology

442 Romeo FJ, et al. Frail scales in patients undergoing TAVR

with a score of 1-2/5 were classified as pre-frail, and those statistics and standard errors are reported for the frail and

with a score of 0/5 were classified as non-frail.[1] pre-frail classifications. The interpretation of kappa values

Each frailty domain was scored by commonly accepted was based on the suggestions by Viera and Garrett. All of

methods of the MFFA. Patients with self-reported uninten- the analyses were considered significant at a two-tailed

tional weight loss (5% of body weight lost unintentionally P-value of ≤ 0.05. All statistical tests were performed using

in the prior year) were considered as “shrinking”. statistical software SPSS 23.0 for Microsoft (SPSS Inc;

We measured 5-m gait speed (the time required for the IBM, Chicago, IL).

patient to complete a 5-m walk test), and we defined slow- The median (IQR) age and BMI of participants was 84

ness as a 5-m gait speed slower than the twentieth percentile (8087) years and 27 (24–32) kg/m2, respectively. Patients

from a cohort of over 5,000 community-dwelling adults > who died at 1-year follow-up were more anemic at baseline

65 years stratified by gender and height.[1] Grip strength for and presented higher surgical risk scores (P ≤ 0.05) (Ta-

defining sarcopenia (i.e “weakness”) was not evaluated due ble 1).

to the risk of syncope in this population. However, we used As reported in Table 2, we did not find differences in ei-

the SARC-F, a questionnaire with five questions, which has ther of the frailty scales according to alive or deceased pa-

high specificity, albeit low sensitivity, to identify patients tients at follow-up. Interestingly, the median (IQR) Mini-

with sarcopenia.[15–17] Cog score was 3 (1–4), and approximately 35% (45/130) of

Finally, we assessed functional performance using the the study participants were classified as having cognitive

Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living impairment. Moreover, the median (IQR) TUG was 13.4

(ADL) scale which is a patient-reported 6-point scale meas- (11–17) s and gait speed 0.62 (0.48–0.79) m/s indicating a

uring dependence with 6 ADLs (bathing, dressing, hygiene, state of moderate muscular performance with subsequent

mobility, continence, and feeding). Congruous with previ- risk of both health decline, ADL difficulty, and falls.

ous reports using the Katz ADL scale, we defined declined As shown in Figure 1, according to MFFA, 54/130 (40%)

functional performance as the presence of any disability patients were frail, 49/130 (38%) patients were pre-frail and

(any score < 6). 28/130 (22%) were non-frail. Thirty-day outcomes were

As previously mentioned, the EFS comprised 10 ques- very similar between the frail and non-frail groups accord-

tions and one physical assessment (“timed up and go”) per- ing to MFFA. Ten (7%) patients died within 30 days of un-

formed by the same team of geriatricians. The EFS assesses dergoing TAVR. Of these, seven were non-frail (9% of the

nine domains of frailty (cognition, general health status, non-frail group) and three were frail (5% of the frail group).

functional independence, social support, medication usage, Median (IQR) length of stay (LOS) of the surviving to

nutrition, mood, continence, functional performance).[18,19] discharge patients (120 patients) was five days; IQR 3–7 days

We classified patients with a frailty score of ≥ 8/17 as frail, post procedure. Non-frail median LOS was five days and the

whereas those with a score of 6-7/17 were classified as frail group was four; (P = NS).

pre-frail, and those with a score below 6 were classified as As shown in Figure 2, according to EFS, 39/130 (30%)

non-frail. Of note, the EFS was validated in the hands of patients were frail, 44/130 (34%) patients were vulnerable

non-specialists who had no formal training in geriatric care and 46/130 (36%) patients were non-frail. Thirty-day out-

and the administration requires few minutes.[18] comes were very similar between the frail and non-frail

Activities Daily Living (ADL) and Independent Activi- groups according to EFS. From the total of 10 patients who

ties Daily Living (IADL) were measured by interviewing died within 30-days after TAVR, eight patients were classi-

patients, relatives or caregivers.[20] The Timed Up and Go fied as non-frail (8% of the non-frail group) and two were frail

test (TUG) is a mobility assessment that evaluates patients’ (5% of the frail group).

pace, balance, and timing in a walking exercise.[8] Finally, according to EFS, the median (IQR) LOS of the

Continuous variables are presented as median [interquar- surviving to discharge patients was 5 days for non-frail and 4

tile range (IQR)] and compared using t-test or Wilcoxon days for the frail group, respectively (P = NS). There was fair

rank sum test when appropriate. Categorical variables were to moderate agreement between methods for determining

summarized as counts (frequency percentages). Categorical which participants were frail [0.40 (0.084), P = 0.001].

data were compared with the Chi2 test or Fisher’s exact test In this single-center experience of elderly patients under-

when appropriate. Frailty scales were primarily analyzed in going TAVR, the prevalence of frailty was 40% according

their continuous form and secondarily in their dichotomous to MFFA, and 30% according to the EFS. Of note, the EFS

form based on a priori cutoffs. was validated in the hands of non-specialists who had no for-

To test the agreement between measures, Cohen kappa mal training in geriatric care. Thus, the EFS has the potential

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology | jgc@jgc301.com; http://www.jgc301.com

Romeo FJ, et al. Frail scales in patients undergoing TAVR 443

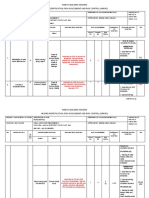

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Total (n = 130) Alive (n = 113) Deceased (n = 17) P-value

Age, yrs 84 (80–87) 84 (81–87) 84 (79–87) 0.86

Men 56 (43%) 50 (44.2%) 6 (35.2%) 0.48

2

BMI, kg/m 27 (24–32) 27 (23–32) 28 (25–32) 0.38

Hypertension 118 (90.7%) 102 (90.2%) 16 (94.1%) 0.60

Diabetes mellitus 28 (21.5%) 23 (20.3%) 5 (29.4%) 0.39

Coronary artery disease 64 (49.2%) 55 (48.6%) 9 (52.9%) 0.74

Coronary artery stent 36 (27.6%) 30 (26.5%) 6 (35.2%) 0.46

Coronary artery bypass surgery 19 (14.6%) 17(15%) 2 (11.7%) 0.72

Peripheral artery disease 34 (26.1%) 28 (24.7%) 6 (35.2%) 0.35

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 14 (10.7%) 11 (9.7%) 3 (17.6%) 0.32

Chronic kidney disease 45 (34.6%) 40 (35.3%) 5 (29.4%) 0.65

Hemoglobin, mg/dL 12.4 (11.4–13.5) 12.5 (11.6–13.5) 11.2 (10.6–12.7) 0.04

Atrial fibrillation or flutter 33 (25.3%) 30 (26.5%) 3 (17.6%) 0.43

NYHA class 3 or 4 39 (30%) 32 (28.3%) 7 (41.1%) 0.28

Euroscore II 3 (1.9–4.6) 2.9 (1.9–4.5) 3.5 (2.6–6.7) 0.002

STS-predicted 30-day operative mortality, % 3.4 (2.5–5) 3.1 (2.2–4.9) 5.5 (4–8.9) 0.002

NT pro-BNP, ng/dL 877 (405–2207) 849 (377–2440) 1412 (796–1871) 0.86

Left ventricular ejection fraction, % 56 (55–65) 55 (56–65) 60 (55–65) 0.97

Aortic valve area, cm2 0.79 (0.67–0.90) 0.80 (0.68–0.90) 0.69 (0.64–0.94) 0.43

Trans-femoral TAVR 96 (73.8%) 82 (72.5%) 14 (82.3%) 0.39

Transapical TAVR 34 (26.2%) 31 (27.5%) 3 (17.7%)

Categorical variables presented as n (%) with P-value indicating result of chi-square test between frailty groups. Continuous variables presented as median (IQR) with

P-value indicating result of 1-way analysis of variance between frailty groups. BMI: body mass index; IQR: interquartile range; NYHA: New York Heart Associa-

tion; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TAVR: trans-catheter aortic valve replacement.

Table 2. Frailty scales and geriatric domains.

Total (n = 130) Alive (n = 113) Deceased (n = 17) P-value

Frailty scales

Fried, 0 to 5 2 (1–3) 2 (1–3) 2 (1–3) 0.98

Edmonton, 0 to 17 6 (4–8) 6 (4–8) 6 (4–8) 0.72

Individual items

Timed Up and Go test, s 13.4 (11–17) 13.9 (10.7–17.1) 12.2 (11.2–15.5) 0.39

Gait speed, m/s 0.62 (0.48–0.79) 0.62 (0.48–0.80) 0.62 (0.51–0.71) 0.78

Charlson score 2 (1–3) 2 (1–3) 2 (1–3) 0.22

Weight loss 24 (18.4) 21 (18.5) 3 (17.6) 0.84

Cognitive impairment (Mini-Cog) 3 (1–4) 2 (1–4) 2 (1–3) 0.48

Depressed mood (PHQ-2) 0 (0–1) 0 (0–1) 1 (0–2) 0.01

ADL disability 6 (5–6) 6 (5–6) 5 (4–6) 0.22

IADL disability 7 (5–8) 7 (5–8) 6 (5–8) 0.74

Data are presented as median (IQR) with P-values indicating result of one-way analysis of variance between frailty groups. ADL: activities of daily living; IADL:

independent activities daily living; IQR: interquartile range.

as a practical and clinically meaningful measure of frailty in between alive and deceased patients at follow-up, most of

a variety of settings including pre-TAVR assessment. the patients were frail or pre-frail, i.e., “vulnerable”. It is

Despite we did not found differences in frailty prevalence important to mention that frailty is a dynamic concept that is

http://www.jgc301.com; jgc@jgc301.com | Journal of Geriatric Cardiology

444 Romeo FJ, et al. Frail scales in patients undergoing TAVR

Figure 1. (A): Percentage of screened TAVR patients according to frailty status; (B): percentage of TAVR patients scoring 0 to 5 on

adapted Fried’s frailty index. TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Figure 2. (A): Percentage of screened TAVR patients according to frailty status; (B): percentage of TAVR patients scoring 0 to 17 on

adapted Edmonton frailty index. TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

able to be reversed with adequate intervention.[21] We be- Islam, et al.[26] and Theou, et al.[27] whom both showed agree-

lieve our results may be influenced by the fact that patients ment between MFFA and CFS, i.e., Clinical Frailty Scale.

with extreme frailty, severely impaired functional perform- Although the EFS has been compared against the clinical

ance, dementia and less than a year of life expectancy were impression of frailty by geriatric specialists[18] appearing to

excluded from TAVR according to our comprehensive geri- be valid, reliable and feasible for routine use by non-geria-

atric assessment. tricians, there is no previous data in the literature comparing

The association of both EFS[22] and MFFA[23,24] with multi- these two scales for frailty assessment neither agreement

dimensional geriatric conditions has already been studied between them.

showing an association with several geriatric conditions such Given that physical activity expressed by the TUG and

as independence, drug assumption, mood, mental, functional gait speed are important indicators of frailty,[28] it is not sur-

and nutritional status. prising that agreement between the EFS and MFFA is fair to

In general, we found a similar distribution of cognition moderate. Our findings show that for identifying frail or

impairment, deficits in physical performance and comorbid- pre-frail older adults, either method could be used, but con-

ities burden between alive and deceased patients at 1-year sideration should be provided to other aspects specifically

follow-up. However, deceased patients showed significantly involving motor abilities.

higher rates of mood disorders. The influence of both cogni- Unfortunately, there is still a lack of consensus for a sin-

tive impairment and depression on TAVR has not been gle frailty method in clinical practice. In this direction, in

conclusive in the literature. order to improve understanding of how frailty impacts sur-

There was a fair to moderate agreement between assess- vival, functionality, and quality of life in TAVR recipients,

ment methods in our cohort. These findings are similar to a protocol has been recently published for a systematic re-

those reported by Pritchard, et al.[25] who showed agree- view which will surely shed light on this issue.[29]

ment between MFFA and other frailty assessment method Our study has some limitations. Our data are derived from

(SPPB, i.e., Short Performance Physical Battery) and also a retrospective, single-center experience, which limits the

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology | jgc@jgc301.com; http://www.jgc301.com

Romeo FJ, et al. Frail scales in patients undergoing TAVR 445

external validity of our findings. Second, the sample size in 8 Stortecky S, Schoenenberger A, Moser A, et al. Evaluation of

our report is modest, which limits our ability to detect small multidimensional geriatric assessment as a predictor of mor-

but important differences in outcomes between groups. In this tality and cardiovascular events after transcatheter aortic valve

direction, because of the lack of statistically significant dif- implantation. JACC Cardiovas Interv 2012; 5: 489–496.

9 Kano S, Yamamoto M, Shimura T, et al. Gait speed can pre-

ferences between frail and non-frail patients with mortality,

dict advanced clinical outcomes in patients who undergo

we did not perform adjusted multivariate analysis. Moreover,

transcatheter aortic valve replacement insights from a Japa-

it is probable that frail patients had more incidence of other

nese multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017; 10:

important outcomes such as falls, disabilities and long-term e005088.

functional decline which were not analyzed in this manu- 10 Huded CP, Huded JM, Friedman JL, et al. Frailty Status and

script. Outcomes after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am

Finally, the hand grip test was not performed in the vast J Cardiol 2016; 117: 1966–1971.

majority of the patients due to the risk of syncope regarding 11 Chauhan D, Haik N, Merlo A, et al. Quantitative increase in

their clinical status (AS). Weakness in MFFA was then punc- frailty is associated with diminished survival after transcathe-

tuated by geriatricians regarding other method (SARC-F ter aortic valve replacement. Am Heart J 2016; 182: 146–154.

questionnaire). Although the prevalence of frailty rates where 12 Koizia L, Khan S, Frame A, et al. Use of the reported edmon-

similar to those reported in the literature, this limitation could ton frail scale in the assessment of patients for transcatheter

aortic valve replacement. a possible selection tool in very

influence our results.

high-risk patients? J Geriatr Cardiol 2018; 15: 463–466.

In conclusion, the prevalence of frailty using both MFFA

13 Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACC

and EFS is similar to that reported in the literature. A fair to

guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart

moderate agreement was estimated between methods. disease: executive summary: a report of the American College

of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on

Acknowledgements Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 2438–2488.

14 STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database data collection forms

Many thanks to the staff in our team who participated in and specifications. http://www.sts.org/sts-national-database/

the patient follow-up. All authors have no conflicts of interest database-managers/adultcardiac-surgerydatabase/data-collec-

to disclose. tion (accessed October 24, 2019).

15 Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Simonsick EM, et al. SARC-F: a

References symptom score to predict persons with sarcopenia at risk for

poor functional outcomes. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Mus-

1 Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: cle 2016; 7: 28–36.

evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 16 Woo J, Leung J, Morley JE. Defining sarcopenia in terms of

56: M146–M156. incident adverse outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015; 16:

2 Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. 247–252.

Lancet 2013; 381: 752–762. 17 Bahat G, Yilmaz O, Kiliç C, et al. Performance of SARC-F in

3 Tom SE, Adachi JD, Anderson FA, et al. Frailty and fracture, regard to sarcopenia definitions, muscle mass and functional

disability, and falls: a multiple country study from the global measures. J Nutr Health Aging 2018; 22: 898–903.

longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. J Am Geriatr 18 Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, et al. Validity and

Soc 2013; 61: 327–334. reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing 2006; 35:

4 Afilalo J, Lauck S, Kim DH, et al. Frailty in older adults un- 526–529.

dergoing aortic valve replacement: The FRAILTY-AVR Study. 19 Partridge JSL, Judith SL, Fuller M, et al. Frailty and poor

J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70: 689–700. functional status are common in arterial vascular surgical pa-

5 Kleczynski P, Dziewierz A, Bagienski M et al. Impact of tients and affect postoperative outcomes. Int J Surg 2015; 18:

frailty on mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implanta- 57–63.

tion. Am Heart J 2017; 185: 52–58. 20 Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan A, et al. Frailty consensus: a

6 Puls M, Sobisiak B, Bleckmann A, et al. Impact of frailty on call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013; 14: 392–397.

short- and long-term morbidity and mortality after transcatheter 21 Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in

aortic valve implantation: Risk assessment by Katz Index of the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of bio-

activities of daily living. EuroIntervention 2014; 10: 609–613. logical and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963; 185: 914–919.

7 Green P, Cohen DJ, Genereux P, et al. Relation between 22 Perna S, Francis MD, Bologna C, et al. Performance of Ed-

six-minute walk test performance and outcomes after tran- monton Frail scale on frailty assessment: its association with

scatheter aortic valve implantation (from the PARTNER multi-dimensional geriatric conditions assessed with specific

Trial). Am J Cardiol 2013; 112: 700–706. screening tools. BMC Geriatr 2017; 17: 2.

http://www.jgc301.com; jgc@jgc301.com | Journal of Geriatric Cardiology

446 Romeo FJ, et al. Frail scales in patients undergoing TAVR

23 Akin S, Mazicioglu MM, Mucuk S, et al. The prevalence identification: comparison of two methods among community-

of frailty and related factors in community-dwelling Turkish dwelling older adults. J Frailty Aging 2014; 3: 216–221.

elderly according to modified Fried Frailty Index and FRAIL 27 Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, et al. Operationalization

scales. Aging Clin Exp Res 2015; 27: 703–709. of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison

24 Buttery AK, Busch MA, Gaertner B, et al. Prevalence and of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc

correlates of frailty among older adults: findings from the Ger- 2013; 61: 1537–1551.

man health interview and examination survey. BMC Geriatr 28 Viana JU, Silva SL, Torres JL, et al. Influence of sarcopenia

2015; 15: 22. and functionality indicators on the frailty profile of commu-

25 Pritchard J, Kennedy C, Karampatos S, et al. Measuring nity-dwelling elderly subjects: a cross-sectional study. Braz J

frailty in clinical practice: a comparison of physical frailty as- Phys Ther 2013; 17: 373–381.

sessment methods in a geriatric outpatient clinic. BMC Geri- 29 Li Z, Dawson E, Moodie J, et al. Frailty in patients undergo-

atr 2017; 17: 264. ing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a protocol for a

26 Islam A, Muir-Hunter SW, Speechley M, et al. Facilitating frailty systematic review. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e024163.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology | jgc@jgc301.com; http://www.jgc301.com

You might also like

- MoH Adverse Events Policy PDFDocument33 pagesMoH Adverse Events Policy PDFnayan4uNo ratings yet

- JC Frailty As A Risk Predictor in Cardiac SurgeryDocument30 pagesJC Frailty As A Risk Predictor in Cardiac SurgeryFaizan Ahmad AliNo ratings yet

- Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2021 May 27 Romeo FJDocument8 pagesCatheter Cardiovasc Interv 2021 May 27 Romeo FJFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal Failure in Critically Ill Surgical Patients PDFDocument7 pagesAcute Renal Failure in Critically Ill Surgical Patients PDFRomán Jiménez LópezNo ratings yet

- Fried Frailty Pred Surg Outcomes AmCSurg 10Document8 pagesFried Frailty Pred Surg Outcomes AmCSurg 10edos838No ratings yet

- El Kersh2015Document8 pagesEl Kersh2015Sathoodeh BanuNo ratings yet

- Pengertian Status Fisik ASADocument8 pagesPengertian Status Fisik ASARiki HidayatullahNo ratings yet

- Santos 2018Document7 pagesSantos 2018Bertha FransiscaNo ratings yet

- PIIS1078588419310755Document7 pagesPIIS1078588419310755zeeshan qurbanNo ratings yet

- Tabata 2014Document6 pagesTabata 2014Kings AndrewNo ratings yet

- Serum Biomarkers Related To Frailty Predict Negative Outcomes in Older Adults With Hip FractureDocument10 pagesSerum Biomarkers Related To Frailty Predict Negative Outcomes in Older Adults With Hip FractureBernardo Abel Cedeño VelozNo ratings yet

- Repair of Rotator Cuff Tears in The Elderly: Does It Make Sense?Document10 pagesRepair of Rotator Cuff Tears in The Elderly: Does It Make Sense?Gustavo BECERRA PERDOMONo ratings yet

- Frailty and AnesthesiaDocument33 pagesFrailty and AnesthesiaRadmila KaranNo ratings yet

- Gait Speed, Grip Strength, and Clinical Outcomes in Older Patients With Hematologic MalignanciesDocument9 pagesGait Speed, Grip Strength, and Clinical Outcomes in Older Patients With Hematologic MalignanciesTícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Increased Heart Rate During Walk Test Predicts Chronic-Phase Worsening of Renal Function in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Normal Kidney FunctionDocument10 pagesIncreased Heart Rate During Walk Test Predicts Chronic-Phase Worsening of Renal Function in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Normal Kidney Functionvn0328897777No ratings yet

- Giglio 2018Document11 pagesGiglio 2018yafanitaizzatiNo ratings yet

- Cardiac ValveDocument9 pagesCardiac Valveikbal rambalinoNo ratings yet

- Addendum of Newer Anticoagulants To The SIR Consensus GuidelineDocument5 pagesAddendum of Newer Anticoagulants To The SIR Consensus GuidelineCenith De Los ReyesNo ratings yet

- 2021 Special Care in Dentistry Detection of Calcified AtheromasDocument6 pages2021 Special Care in Dentistry Detection of Calcified AtheromasNATALIA SILVA ANDRADENo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Eurger 2016 01 005 PDFDocument4 pages10 1016@j Eurger 2016 01 005 PDFBasilio Papuico RomeroNo ratings yet

- Reliability of Gait Performance Tests in Men and Women With Hemiparesis After StrokeDocument8 pagesReliability of Gait Performance Tests in Men and Women With Hemiparesis After StrokeKaniNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Post Operative Systemic To Pulmonary Artery Shunt FailureDocument5 pagesAnalysis of Post Operative Systemic To Pulmonary Artery Shunt FailurePaul HartingNo ratings yet

- The Shortfall in Long-Term Survival of Patients With Repaired Thoracic Orabdominal Aortic Aneurysms Retrospective CaseeControl Analysis Ofhospital Episode StatisticsDocument9 pagesThe Shortfall in Long-Term Survival of Patients With Repaired Thoracic Orabdominal Aortic Aneurysms Retrospective CaseeControl Analysis Ofhospital Episode StatisticsJeffery TaylorNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of Achalasia Quality of Life and Eckardt Scores For Assessment of Clinical Improvement Post Treatment For AchalasiaDocument9 pagesAccuracy of Achalasia Quality of Life and Eckardt Scores For Assessment of Clinical Improvement Post Treatment For AchalasiaykommNo ratings yet

- Calder 2016 - Meta Analysis and Suggested Guidelines For Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) in Foot and Ankle SurgeryDocument12 pagesCalder 2016 - Meta Analysis and Suggested Guidelines For Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) in Foot and Ankle SurgeryNoel Yongshen LeeNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical & Translational EndocrinologyDocument5 pagesJournal of Clinical & Translational EndocrinologyRicky BooyNo ratings yet

- Hs 15069Document4 pagesHs 15069Deepak RanaNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Versus Open Surgery For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in Low - To Moderate-Risk PatientsDocument8 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Versus Open Surgery For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in Low - To Moderate-Risk Patientsvfd08051996No ratings yet

- Atm 09 02 118Document10 pagesAtm 09 02 118idham shadiqNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Cardiology: Contents Lists Available atDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Cardiology: Contents Lists Available atWesleyMesquitaNo ratings yet

- Yejvs - 7376Document14 pagesYejvs - 7376Francisco Álvarez MarcosNo ratings yet

- 24 Rudrajit EtalDocument6 pages24 Rudrajit EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- The Model For End-Stage Liver DiseaseDocument9 pagesThe Model For End-Stage Liver Diseasegwyneth.green.512No ratings yet

- CC 4915Document10 pagesCC 4915Livia Meidy UbayidNo ratings yet

- 3 Ijmpsoct20173Document6 pages3 Ijmpsoct20173TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Wang Et Al - Older Age and Outcome AfterDocument9 pagesWang Et Al - Older Age and Outcome AfterMurat MukharyamovNo ratings yet

- 11 134 v12n4 2013 PredictingPortalDocument11 pages11 134 v12n4 2013 PredictingPortalDevy Widiya GrafitasariNo ratings yet

- Alvarado Scoring in Acute Appendicitis-A Clinicopathological CorrelationDocument5 pagesAlvarado Scoring in Acute Appendicitis-A Clinicopathological CorrelationMahlina Nur LailiNo ratings yet

- A New Operational Definition of Frailty The Frailty Trait Scale - Garcia - Garcia2014Document7 pagesA New Operational Definition of Frailty The Frailty Trait Scale - Garcia - Garcia2014dariorguezNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 10158Document10 pages2021 Article 10158juajimenez55No ratings yet

- Displasia de CaderaDocument10 pagesDisplasia de CaderaPAOLA ESTEFANIA ESPINOZA CASTRONo ratings yet

- Bessire 2014Document7 pagesBessire 2014andrei3cucuNo ratings yet

- Radiol 2019190734Document10 pagesRadiol 2019190734Dimas agung okoputraNo ratings yet

- F QRSDocument9 pagesF QRSaisyah hamzakirNo ratings yet

- The Alvarado Score For Predicting Acute Appendicitis: A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesThe Alvarado Score For Predicting Acute Appendicitis: A Systematic ReviewAndy Zevallos AraujoNo ratings yet

- 2003-Academic Emergency MedicineDocument154 pages2003-Academic Emergency MedicinealiceNo ratings yet

- Annsurg00185 0122Document6 pagesAnnsurg00185 0122Fajr MuzammilNo ratings yet

- SMJ 56 626Document6 pagesSMJ 56 626Andy HongNo ratings yet

- Vesconi 2009Document14 pagesVesconi 2009Nguyễn Đức LongNo ratings yet

- Validity of Grace Risk Score To Predict The Prognosis in Elderly Patients With Acute Coronary SyndromeDocument9 pagesValidity of Grace Risk Score To Predict The Prognosis in Elderly Patients With Acute Coronary SyndromeFachry MuhammadNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11739 019 02196 ZDocument10 pages10.1007@s11739 019 02196 ZMaharani Sari NastitiNo ratings yet

- Søvik2019 Article AcuteKidneyInjuryInTraumaPatie PDFDocument13 pagesSøvik2019 Article AcuteKidneyInjuryInTraumaPatie PDFamal.fathullahNo ratings yet

- ScienceDocument6 pagesSciencesddfsfNo ratings yet

- CSM 3 2 46 52Document7 pagesCSM 3 2 46 52Santoso 9JimmyNo ratings yet

- NutritionDocument10 pagesNutritionDani ursNo ratings yet

- Management of AclfDocument30 pagesManagement of Aclfsaraswathy sNo ratings yet

- Extracorporeal Life Support in Pediatric Cardiac DysfunctionDocument5 pagesExtracorporeal Life Support in Pediatric Cardiac DysfunctionNoor Aida AriyaniNo ratings yet

- Artigo TX Bia 2011Document5 pagesArtigo TX Bia 2011gutorpNo ratings yet

- Vanreijen 2019Document10 pagesVanreijen 2019Ivor Wiguna Hartanto WilopoNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 3: CardiologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 3: CardiologyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 17: OncologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 17: OncologyNo ratings yet

- J Clin Rheumatol 2021 Aug 2 Fernandez-Avila DGDocument4 pagesJ Clin Rheumatol 2021 Aug 2 Fernandez-Avila DGFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- J Hepatol 2022 Jan 20 Pape S Mat Compl 1Document17 pagesJ Hepatol 2022 Jan 20 Pape S Mat Compl 1Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2021 Aug 2 Cereghini JDocument11 pagesDisaster Med Public Health Prep 2021 Aug 2 Cereghini JFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Pediatr Transplant 2021 E14105Document4 pagesPediatr Transplant 2021 E14105Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- J Rheumatol 2021 Jun 15 Fernandez-Avila DGDocument7 pagesJ Rheumatol 2021 Jun 15 Fernandez-Avila DGFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension 2020 76 2 333-41Document9 pagesHypertension 2020 76 2 333-41Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Orthop J Sports Med 2021 9 7 23259671211013394Document6 pagesOrthop J Sports Med 2021 9 7 23259671211013394Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020 29 1 71-81Document11 pagesEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020 29 1 71-81Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Eur J Ophthalmol 2020 May 13 Diamint DVDocument5 pagesEur J Ophthalmol 2020 May 13 Diamint DVFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Epilepsy Behav 2020 112 107447Document4 pagesEpilepsy Behav 2020 112 107447Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Effect of PEEP On Dead Space in An Experimental Model of ARDSDocument10 pagesEffect of PEEP On Dead Space in An Experimental Model of ARDSFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- J Thromb Thrombolysis 2020 Sep 14 Smith DDocument8 pagesJ Thromb Thrombolysis 2020 Sep 14 Smith DFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Acr 1st NsedDocument2 pagesAcr 1st NsedRey SilvestreNo ratings yet

- Yseali Younified 2020 A Guide To Planning A Community Service ActivityDocument17 pagesYseali Younified 2020 A Guide To Planning A Community Service ActivityHamidatun NisaNo ratings yet

- Home EconomicsDocument5 pagesHome EconomicsNicole Kathleen Caranto100% (1)

- Anandhu M AVT Academy 1486Document17 pagesAnandhu M AVT Academy 1486anandmg41No ratings yet

- COPD Case Pres2Document29 pagesCOPD Case Pres2Kelly Queenie Andres100% (2)

- 2012 Resistant HypertensionDocument9 pages2012 Resistant HypertensionBarry Tumpal Wouter NapitupuluNo ratings yet

- SPC HIRADC - 022 - Road WorksDocument5 pagesSPC HIRADC - 022 - Road WorksKalai ArasanNo ratings yet

- FORM 4.1 Self Assesment Check ListDocument3 pagesFORM 4.1 Self Assesment Check ListNica ManlugonNo ratings yet

- Medical GasesDocument20 pagesMedical Gasesmagicarray.hrNo ratings yet

- Chronic MeningitisDocument7 pagesChronic Meningitisneurojuancarfab100% (1)

- Janitorial ProductivityDocument7 pagesJanitorial ProductivityThe Cleaning LibraryNo ratings yet

- The Who Five Keys To Safer Food A Tool For Food Safety Health PromotionDocument15 pagesThe Who Five Keys To Safer Food A Tool For Food Safety Health PromotionCarlos RuizNo ratings yet

- KasaiDocument7 pagesKasaishalukiriNo ratings yet

- MSDS AstDocument6 pagesMSDS AstKRRNo ratings yet

- Things We Do For No Reason: Calculating A "Corrected Calcium" LevelDocument3 pagesThings We Do For No Reason: Calculating A "Corrected Calcium" LevelCsr ArsNo ratings yet

- Macro Analysis PhilippinesDocument9 pagesMacro Analysis PhilippinesAnthony AlferesNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan - Fatigue (Antepartum)Document3 pagesNursing Care Plan - Fatigue (Antepartum)kaimimiyaNo ratings yet

- MEDICARDDocument19 pagesMEDICARDSrcdc CooperativeNo ratings yet

- Advance Project Final FeasibilityDocument31 pagesAdvance Project Final FeasibilityMohammad Adil ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Codependency Treatment Systematic Review 2015Document12 pagesCodependency Treatment Systematic Review 2015Ryan PetersonNo ratings yet

- 37 - Hematuria & RCCDocument53 pages37 - Hematuria & RCCRashed ShatnawiNo ratings yet

- Reviste Medicale Internationale Cotate IsiDocument28 pagesReviste Medicale Internationale Cotate IsidoruNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Rifampicin Resistance Tuberculosis and Associated Factors Among Presumptive TB or MDRDocument3 pagesPrevalence of Rifampicin Resistance Tuberculosis and Associated Factors Among Presumptive TB or MDRTigray OutlookNo ratings yet

- Research Agenda of The College of Business and Entrepreneurship - DDocument57 pagesResearch Agenda of The College of Business and Entrepreneurship - DSev BlancoNo ratings yet

- Pharm Test BankDocument5 pagesPharm Test BankMorgan SmithNo ratings yet

- Requirements For Vessels Arriving in The Port of SingaporeDocument10 pagesRequirements For Vessels Arriving in The Port of SingaporenarutorazNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - Detecting The Mood Disorder FinalDocument2 pagesLesson Plan - Detecting The Mood Disorder FinalTrixie MizonaNo ratings yet

- SCIDDocument10 pagesSCIDIbrahimNo ratings yet

- Checked Testing Effectiveness of Types of ToothpasteDocument9 pagesChecked Testing Effectiveness of Types of ToothpasteMaya AltahaNo ratings yet