Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Prokalsitonin

Prokalsitonin

Uploaded by

Farmasi RSUD Kramat JatiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare 4th Edition Melnyk Test BankDocument4 pagesEvidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare 4th Edition Melnyk Test Bankqwivy.com33% (3)

- Written Report - 6.419x Module 1Document8 pagesWritten Report - 6.419x Module 1聂宝鹏No ratings yet

- CONSORT Checklist of Information To Include When Reporting A Randomised TrialDocument3 pagesCONSORT Checklist of Information To Include When Reporting A Randomised TrialJoko Tri WahyudiNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin and AB DecisionsDocument10 pagesProcalcitonin and AB DecisionsDennysson CorreiaNo ratings yet

- Rab 8Document21 pagesRab 8Belia DestamaNo ratings yet

- 10.1515 - CCLM 2022 1072Document7 pages10.1515 - CCLM 2022 1072ENFERMERIA EMERGENCIANo ratings yet

- Effect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticDocument11 pagesEffect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticRaul ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Hochreiter2009 PDFDocument7 pagesHochreiter2009 PDFmr_curiousityNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial ResistanceDocument11 pagesAntimicrobial Resistanceapi-253312159No ratings yet

- Golden Hour CCM Arthur Van Zanten IC1Document3 pagesGolden Hour CCM Arthur Van Zanten IC1Sara NicholsNo ratings yet

- Abdul Aziz2015 PDFDocument18 pagesAbdul Aziz2015 PDFSambit DashNo ratings yet

- Jiaa 221Document13 pagesJiaa 221AndradaLavricNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Strategies in Severe Nosocomial Sepsis: Why Do We Not De-Escalate More Often?Document7 pagesAntibiotic Strategies in Severe Nosocomial Sepsis: Why Do We Not De-Escalate More Often?Anonymous 2kPiJhIlFNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics 11 00022Document16 pagesAntibiotics 11 00022Putri RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- CAP Treatamnet AcortadoDocument8 pagesCAP Treatamnet Acortadoapi-3707490No ratings yet

- Association Between Immune-Related Adverse Event TDocument8 pagesAssociation Between Immune-Related Adverse Event TAndrew FincoNo ratings yet

- Antibiotecoterapia en SepsisDocument13 pagesAntibiotecoterapia en SepsisJuan Pablo Arteaga VargasNo ratings yet

- Wjco 12 712Document14 pagesWjco 12 712ovatanaNo ratings yet

- Thu 2012Document5 pagesThu 2012Nadila Hermawan PutriNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument15 pagesHHS Public AccessGustavo GomezNo ratings yet

- Lam 2018Document7 pagesLam 2018adrifen adriNo ratings yet

- The Bio Immune Gene Medicineorhowtouseamaximumofmolecularresourcesofthecellfortherapeuticpurposes ARTICLEDocument8 pagesThe Bio Immune Gene Medicineorhowtouseamaximumofmolecularresourcesofthecellfortherapeuticpurposes ARTICLEGines RoaNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Prophylactic Antibiotics For Neurosurgical ProceduresDocument6 pagesThe Ethics of Prophylactic Antibiotics For Neurosurgical ProceduresBahtiar ArasNo ratings yet

- Colistin Monotherapy Versus Combination Therapy For Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms NEJM EvidenceDocument27 pagesColistin Monotherapy Versus Combination Therapy For Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms NEJM Evidencerac.oncologyNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Clinical Evaluation of Antibiotic Use Among Patients With InfectionDocument11 pagesLongitudinal Clinical Evaluation of Antibiotic Use Among Patients With InfectionMITA RESTINIA UINJKTNo ratings yet

- Mitos InfeccionesDocument8 pagesMitos InfeccionesAmmon10famNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Microbiology-2011-Wolk-S62.fullDocument6 pagesJournal of Clinical Microbiology-2011-Wolk-S62.fullAli AhmedNo ratings yet

- Appropriate AntibioticDocument18 pagesAppropriate AntibioticLAYSANY CAVAZOSNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial StewardshipDocument7 pagesAntimicrobial StewardshipJohn TusselNo ratings yet

- De-Escalacion de ATM en UCI Revisión 2015 y en ShockDocument15 pagesDe-Escalacion de ATM en UCI Revisión 2015 y en ShockLesly Peinado TorresNo ratings yet

- PMK No. 43 TTG Penyelenggaraan Laboratorium Klinik Yang BaikDocument16 pagesPMK No. 43 TTG Penyelenggaraan Laboratorium Klinik Yang BaikyantuNo ratings yet

- Joc90090 1059 1066Document8 pagesJoc90090 1059 1066Roxana Maria MunteanuNo ratings yet

- NouwenDocument2 pagesNouwenmarkinceNo ratings yet

- The Active Comparator, New User Study Design in Pharmacoepidemiology: Historical Foundations and Contemporary ApplicationDocument8 pagesThe Active Comparator, New User Study Design in Pharmacoepidemiology: Historical Foundations and Contemporary ApplicationDici RachmandaNo ratings yet

- SHEA Position Paper: I C H EDocument17 pagesSHEA Position Paper: I C H EIFRS SimoNo ratings yet

- Studi Kasus Resistensi Bakterial 2020-02Document5 pagesStudi Kasus Resistensi Bakterial 2020-02esti mNo ratings yet

- 2667 PDFDocument6 pages2667 PDFMahmudi Sudarsono MNo ratings yet

- Probiotics For Prevention of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea and Meta-AnalysisDocument6 pagesProbiotics For Prevention of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea and Meta-AnalysisRicky FullerNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobialstewardship Approachesinthe Intensivecareunit: Sarah B. Doernberg,, Henry F. ChambersDocument22 pagesAntimicrobialstewardship Approachesinthe Intensivecareunit: Sarah B. Doernberg,, Henry F. ChambersecaicedoNo ratings yet

- ProcalcitonicaDocument27 pagesProcalcitonicaDanny XavierNo ratings yet

- Overuse of AntibioticDocument10 pagesOveruse of AntibioticshinNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Stewardship and Therapeutic Drug.10Document9 pagesAntibiotic Stewardship and Therapeutic Drug.10Khanh Ha NguyenNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional CollaboratioDocument16 pagesInterprofessional CollaboratioAnggito AbimanyuNo ratings yet

- ProkalsitoninDocument9 pagesProkalsitoninAndhika HamdanyNo ratings yet

- Fmed 08 584813Document12 pagesFmed 08 584813Annisa SetyantiNo ratings yet

- Bacteriostatic Versus Bactericidal Antibiotics For Patients With Serious Bacterial Infections: Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument14 pagesBacteriostatic Versus Bactericidal Antibiotics For Patients With Serious Bacterial Infections: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysisblade masterNo ratings yet

- IDSA Gram Negative Guideline 2020Document38 pagesIDSA Gram Negative Guideline 2020Shasha ShakinahNo ratings yet

- Antibiotico en SepsisDocument15 pagesAntibiotico en SepsisJuan RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Applying Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Principles in Critically Ill Patients: Optimizing Ef Ficacy and Reducing Resistance DevelopmentDocument18 pagesApplying Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Principles in Critically Ill Patients: Optimizing Ef Ficacy and Reducing Resistance DevelopmentValentina Lcpc CajaleonNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Lock Therapy: Review of Technique and Logistical ChallengesDocument21 pagesAntibiotic Lock Therapy: Review of Technique and Logistical ChallengesFacundo AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Time To Antibiotic Therapy On Clinical Outcome I 2021 Clinical MicDocument7 pagesImpact of Time To Antibiotic Therapy On Clinical Outcome I 2021 Clinical MicSusanyi ErvinNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated ArthritisDocument15 pagesHHS Public Access: Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated ArthritisJose PiñaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Procalcitonin-Guided Antibiotic Treatment On Mortality in Acute Respiratory Infections: A Patient Level Meta-AnalysisDocument36 pagesEffect of Procalcitonin-Guided Antibiotic Treatment On Mortality in Acute Respiratory Infections: A Patient Level Meta-Analysisrista ria ariniNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Outpatient Antibiotic Use in Beijing General Hospitals in 2015Document9 pagesEvaluation of Outpatient Antibiotic Use in Beijing General Hospitals in 2015UdtjeVanDerJeykNo ratings yet

- Top Myths of Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diseases in Hospital MedicineDocument8 pagesTop Myths of Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diseases in Hospital MedicineLibrosNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Interna UTIDocument8 pagesJurnal Interna UTIErdika Satria WahyuonoNo ratings yet

- Medical Immunology: Optimal Clinical Trial Designs For Immune-Based Therapies in Persistent Viral InfectionsDocument4 pagesMedical Immunology: Optimal Clinical Trial Designs For Immune-Based Therapies in Persistent Viral InfectionsFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin GuidanceDocument44 pagesProcalcitonin GuidanceMiguel Chung SangNo ratings yet

- tmpA70B TMPDocument3 pagestmpA70B TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Vincent J 2020Document11 pagesVincent J 2020Kala PatharNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Twenty-Four Nutrients and Phytonutrients On Immune System Function and Inflammation A Narrative ReviewDocument44 pagesThe Effects of Twenty-Four Nutrients and Phytonutrients On Immune System Function and Inflammation A Narrative ReviewVeronica Ferreiro BlazeticNo ratings yet

- Audit&FeedbackDocument8 pagesAudit&FeedbackfatiisaadatNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: HypertensionDocument48 pagesHHS Public Access: HypertensionFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Kerja ABDocument72 pagesKerja ABFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Lab MikrobiologiDocument6 pagesLab MikrobiologiFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Terapi AbDocument5 pagesTerapi AbFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Suspected Penicillin Allergy: Risk Assessment Using An Algorithm As An Antibiotic Stewardship ProjectDocument7 pagesSuspected Penicillin Allergy: Risk Assessment Using An Algorithm As An Antibiotic Stewardship ProjectFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Beta-Lactam Cross Allergy Matrix: (Based On Similar Core And/or Side Chain Structures)Document1 pageBeta-Lactam Cross Allergy Matrix: (Based On Similar Core And/or Side Chain Structures)Farmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Lab MikrobiologiDocument6 pagesLab MikrobiologiFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Health PEI: Provincial Antibiotic Advisory Team Empiric Antibiotic Treatment Guidelines For Sepsis Syndromes in AdultsDocument10 pagesHealth PEI: Provincial Antibiotic Advisory Team Empiric Antibiotic Treatment Guidelines For Sepsis Syndromes in AdultsFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Provincial Drugs & Therapeutics Committee MemorandumDocument2 pagesProvincial Drugs & Therapeutics Committee MemorandumFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Penisilin Dan Beta LaktamDocument11 pagesPenisilin Dan Beta LaktamFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Infection Recommended Duration Comments Urinary Tract InfectionsDocument2 pagesInfection Recommended Duration Comments Urinary Tract InfectionsFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Ab OperasiDocument28 pagesAb OperasiFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- Antibiotik IV Ke PODocument3 pagesAntibiotik IV Ke POFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiNo ratings yet

- 2023 Article 3988Document18 pages2023 Article 3988Niko TrogerNo ratings yet

- Piracetam Cognitive Vitality For ResearchersDocument13 pagesPiracetam Cognitive Vitality For ResearchersreubenmercadoNo ratings yet

- Electrocardiographic Monitoring 2017Document72 pagesElectrocardiographic Monitoring 2017Mirela Marina BlajNo ratings yet

- (2018) Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Ankle Sprains Update of An Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline PDFDocument16 pages(2018) Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Ankle Sprains Update of An Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline PDFTsz Kwan CheungNo ratings yet

- Wong Et Al-2013-Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews-2Document47 pagesWong Et Al-2013-Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews-2mehakNo ratings yet

- INSPIRE Journal Club Guide PDFDocument3 pagesINSPIRE Journal Club Guide PDFGems GlasgowNo ratings yet

- NOAF en Paciente Critico RevisionDocument11 pagesNOAF en Paciente Critico RevisionARTURO YOSHIMAR LUQUE MAMANINo ratings yet

- How To Make A Young Child Smarter Evidence From The Database of Raising IntelligenceDocument17 pagesHow To Make A Young Child Smarter Evidence From The Database of Raising IntelligenceGary Moller100% (1)

- 10 Simulation Exercises As A Patient Safety Strategy PDFDocument9 pages10 Simulation Exercises As A Patient Safety Strategy PDFAmanda DavisNo ratings yet

- Articulo #6Document9 pagesArticulo #6Jorge GámezNo ratings yet

- Alexander Technique A Systematic Review of Controled TrialsDocument11 pagesAlexander Technique A Systematic Review of Controled TrialsAna Rita PintoNo ratings yet

- Research Methods For Massage and Holistic Therapies (Glenn M. Hymel, EdD, LMT (Auth.) )Document323 pagesResearch Methods For Massage and Holistic Therapies (Glenn M. Hymel, EdD, LMT (Auth.) )Juliano de andradeNo ratings yet

- AphasiaDocument28 pagesAphasiaEmilio Emmanué Escobar CruzNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument382 pagesPDFSastees AllstarNo ratings yet

- Change Without Struggle PRINT QUALDocument66 pagesChange Without Struggle PRINT QUALSanjeev SampathNo ratings yet

- What Is It?: PharmacoeconomicsDocument17 pagesWhat Is It?: PharmacoeconomicssalimNo ratings yet

- EAU Guidelines On Urological Infections 2022Document78 pagesEAU Guidelines On Urological Infections 2022Annia KurniawatiNo ratings yet

- Kaltenborn MethodDocument9 pagesKaltenborn Methodhari vijayNo ratings yet

- Landmark Studies in GlaucomaDocument53 pagesLandmark Studies in GlaucomaDrEknathPawarNo ratings yet

- Lavigne-Forrest - Do No Harm Are You Is Your Dental Hygiene Practice Evidence-Based Part 1Document7 pagesLavigne-Forrest - Do No Harm Are You Is Your Dental Hygiene Practice Evidence-Based Part 1NasecaNo ratings yet

- The Value of Preoperative Exercise and Education For Patients Undergoing Total Hip and Knee ArthroplastyDocument15 pagesThe Value of Preoperative Exercise and Education For Patients Undergoing Total Hip and Knee ArthroplastyemilNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Deep Oscillation Therapy On Reducing Swelling and Pain in Athletes With Acute Lateral Ankle SprainsDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness of Deep Oscillation Therapy On Reducing Swelling and Pain in Athletes With Acute Lateral Ankle SprainsNyLa LibertyNo ratings yet

- Io Sumber Dan LiteraturDocument42 pagesIo Sumber Dan LiteraturIndra PratamaNo ratings yet

- A Five-Year Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Per PDFDocument10 pagesA Five-Year Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Per PDFJoel SantosNo ratings yet

- Importance, Roles, Scope and Characteristics of ResearchDocument12 pagesImportance, Roles, Scope and Characteristics of ResearchMaricar CacaoNo ratings yet

- Advances in The Management of Cardiogenic ShockDocument12 pagesAdvances in The Management of Cardiogenic ShockJoelGámezNo ratings yet

- Guideline - Nutrition Support of Adult Patients With Enterocutaneous FistulaDocument9 pagesGuideline - Nutrition Support of Adult Patients With Enterocutaneous FistulaAlexandra RodriguesNo ratings yet

Prokalsitonin

Prokalsitonin

Uploaded by

Farmasi RSUD Kramat JatiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Prokalsitonin

Prokalsitonin

Uploaded by

Farmasi RSUD Kramat JatiCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/51555349

Procalcitonin Algorithms for Antibiotic Therapy Decisions: A Systematic Review

of Randomized Controlled Trials and Recommendations for Clinical Algorithms

Article in Archives of Internal Medicine · August 2011

DOI: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.318 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

332 387

4 authors, including:

Philipp Schuetz Matthias Briel

Kantonspital Aarau AG Universitätsspital Basel

573 PUBLICATIONS 13,561 CITATIONS 314 PUBLICATIONS 20,236 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Jeffrey L Greenwald

Massachusetts General Hospital

47 PUBLICATIONS 2,678 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Development of guidelines on nutritional support of polymorbid internal medicine inpatients View project

Psychological adaptation of medical patients following an emergency department admission: The role of individual resources, demographic characteristics and illness-

related variables View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Philipp Schuetz on 20 May 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

REVIEW ARTICLE

Procalcitonin Algorithms for Antibiotic

Therapy Decisions

A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

and Recommendations for Clinical Algorithms

Philipp Schuetz, MD, MPH; Victor Chiappa, MD; Matthias Briel, MD, MSc; Jeffrey L. Greenwald, MD

P

revious randomized controlled trials suggest that using clinical algorithms based on pro-

calcitonin levels, a marker of bacterial infections, results in reduced antibiotic use with-

out a deleterious effect on clinical outcomes. However, algorithms differed among trials

and were embedded primarily within the European health care setting. Herein, we sum-

marize the design, efficacy, and safety of previous randomized controlled trials and propose adapted

algorithms for US settings. We performed a systematic search and included all 14 randomized con-

trolled trials (N = 4467 patients) that investigated procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic treat-

ment decisions in adult patients with respiratory tract infections and sepsis from primary care, emer-

gency department (ED), and intensive care unit settings. We found no significant difference in

mortality between procalcitonin-treated and control patients overall (odds ratio, 0.91; 95% con-

fidence interval, 0.73-1.14) or in primary care (0.13; 0-6.64), ED (0.95; 0.67-1.36), and intensive

care unit (0.89; 0.66-1.20) settings individually. A consistent reduction was observed in antibiotic

prescription and/or duration of therapy, mainly owing to lower prescribing rates in low-acuity pri-

mary care and ED patients, and shorter duration of therapy in moderate- and high-acuity ED and

intensive care unit patients. Measurement of procalcitonin levels for antibiotic decisions in pa-

tients with respiratory tract infections and sepsis appears to reduce antibiotic exposure without

worsening the mortality rate. We propose specific procalcitonin algorithms for low-, moderate-,

and high-acuity patients as a basis for future trials aiming at reducing antibiotic overconsumption.

Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1322-1331

The advent of antibiotic therapy led to dra- Patients and physicians share the com-

matic reductions in mortality and morbid- mon goals of improving the patient’s health

ity rates due to bacterial infections and sep- and resolving infections as quickly as pos-

sis.1 However, overuse of antibiotics to fight sible; they often believe use of antibiotics

infections may cause considerable harm by to be the most expeditious intervention to

exposing individual patients to adverse address these goals. This one-size-fits-all

events resulting from antibiotic use and by

increasing the development of bacterial re- CME available online at

sistance. Combating the emergence of bac- www.jamaarchivescme.com

terial resistance to antimicrobial agents re- and questions on page 1311

quires more effective efforts to reduce the

inappropriate or unnecessarily prolonged approach fails to consider the following ba-

use of antibiotics.2 sic questions: (1) Who truly benefits from

Author Affiliations: Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard School of Public

antibiotic therapy? and (2) If treated, what

Health (Dr Schuetz), and Department of Medicine, Inpatient Clinician Educator is the optimal treatment duration?1

Service, Massachusetts General Hospital (Drs Chiappa and Greenwald), Boston, Considerable interest has been ex-

Massachusetts; and Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, pressed in antibiotic stewardship pro-

McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (Dr Briel). grams aiming at reducing antibiotic over-

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1322

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

use and the associated emergence of roidal anti-inflammatory drugs. ing, in which the term appears in the title,

multiresistant pathogens.3,4 A previ- Based on these promising preclinical abstract, or subject heading]) and calci-

ous cohort study3 of hospitalized adult data, many studies have investigated tonin AND pneumonia (exp [explode, a

patients illustrated the effect of anti- the clinical usefulness of measuring search term that automatically includes

closely related MeSH terms]), sepsis (exp),

microbial-resistant infections on hos- PCT levels for different clinical set-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

pitalization duration, mortality rate, tings and infections.7 However, ow- (exp), or respiratory tract infections (exp).

and cost. In this study, the 188 pa- ing to the diagnostic uncertainty as- We also included procalcitonin (mp) and

tients with antimicrobial-resistant in- sociated with sepsis and other calcitonin AND intensive care units, emer-

fections stayed 6.4 to 12.7 days lon- infectious diseases and the lack of a gency services, hospital, or ambulatory care

ger in the hospital, had attributable diagnostic criterion standard, the re- facilities. We restricted the search to RCTs

mortality of 6.5%, and incurred so- sults of many observational studies performed only in adults. We also iden-

cietal costs ranging from $18 588 to have been inconclusive.7 tified relevant systematic reviews, meta-

$29 069 (2008 dollars) per patient. To circumvent the limitations of analyses, and controlled clinical trials and

A novel approach for determin- observational studies, including ob- reviewed their references; in addition, we

searched trial registries (http://www

ing the necessity and optimal dura- server bias, selection bias, sample

.clinicaltrials.gov and http://www.isrctn

tion of antibiotic therapy is the use availability, coinfection, coloniza- .org) and contacted experts in the field

of biomarkers, such as procalcito- tion, and difficulty of pathogen iden- for additional eligible studies. We in-

nin (PCT) levels, which become up- tification owing to time constraints, cluded articles in any language and did

regulated during bacterial infec- several randomized controlled trials not exclude articles based on other

tions and appear to mirror the severity (RCTs) have been conducted focus- comorbidities.

of infections.5,6 A growing body of lit- ing primarily on the outcomes of pa-

erature supports the measurement of tients with or without the use of PCT- ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

PCT levels to improve the ability to guided algorithms for antibiotic AND STUDY SELECTION

differentiate bacterial from nonbac- therapy. The clinical harm and ben-

terial infections because nonbacte- efit of using PCT thereby were mea- Eligible trials had to be RCTs including

adults with a diagnosis of respiratory

rial infections and nonspecific in- sured by clinical outcomes, assum-

tract infections (ie, pneumonia, acute ex-

flammatory reactions do not result in ing that if the patient recovers without acerbations of chronic obstructive pul-

elevated PCT levels.7 Also, an initial antibiotics, no relevant bacterial ill- monary disease [AECOPD] or other re-

study8 has shown that a decrease in ness had existed, and if the patient re- spiratory tract infections) or sepsis.

PCT levels indicates a favorable pa- covers with fewer days taking anti- Clinical settings included primary care,

tient response to antimicrobial biotics, the bacterial illness was the ED, or the ICU. Interventions in-

therapy. Thus, PCT is a promising adequately controlled with shorter cluded measurement of PCT levels to in-

candidate marker to help physicians antibiotic exposure. form decisions regarding antibiotic

more rationally decide on prescrip- The aim of this systemic review therapy (ie, regarding its initiation and/or

tion and duration of antibiotic therapy is to summarize the evidence based duration). Abstracts or full-text ar-

ticles for which no abstract was avail-

in patients with infections. on previous RCTs for using PCT

able were reviewed by 2 of us (P.S. and

Procalcitonin, the precursor pep- measurement in respiratory infec- J.L.G.) to ensure topic appropriateness

tide of the hormone calcitonin, is re- tions and sepsis from the clinical set- and adherence to inclusion and exclu-

leased ubiquitously in response to tings for which the most RCT data sion criteria. Disagreements were re-

primarily bacterial toxins and bac- are available, namely, primary care, solved by consensus.

teria-specific proinflammatory me- the emergency department (ED), the

diators, particularly interleukin 1b, medical intensive care unit (MICU), DATA EXTRACTION AND

tumor necrosis factor, and interleu- and the surgical intensive care unit QUALITY ASSESSMENT

kin 6.5 In previous studies,9,10 a strong (SICU). Because most published

correlation was observed between studies were conducted in Europe, Working in teams of 2, 3 investigators

the concentration of PCT and the ex- we also aim to propose clinical al- (P.S., V.C., and J.L.G.) independently ex-

tracted data from the included trials. Dis-

tent and severity of bacterial infec- gorithms for use in future United agreements were resolved by consen-

tions. Of particular interest, PCT lev- States trials. sus. A standardized data abstraction tool

els are attenuated by the cytokines was used that included clinical setting,

typically released in response to vi- METHODS study design, number of study subject

ral infections, namely, interferon- individuals, clinical outcomes, and study

␥.10 Levels of PCT have been shown protocols. Also, an assessment of the

to increase within 6 to 12 hours of LITERATURE SEARCH methodological study quality was pe-

the initial bacterial infection, and cir- formed, based on the following criteria:

culating PCT levels are expected to We searched EMBASE (from 1974 to the adequate sequence generation (eg, com-

decrease by half daily when the in- present), MEDLINE via PubMED and puter-generated random numbers, com-

Ovid (from 1948 to the present), and the pared with inadequate approaches,

fection is controlled by the host im- Cochrane Central Register of Con- which included the use of alternation,

mune system and antibiotics (Abx).11 trolled Trials (from 1991 to 2011) for ar- case record numbers, or days of the

A previous study12 has shown that ticles regarding PCT levels taken into ac- week); adequate allocation conceal-

the production of PCT, in contrast count when making decisions regarding ment (deemed adequate if a central ran-

to other blood markers, is not at- Abx. The following search terms were in- domization procedure [ie, telephone or

tenuated by nonsteroidal and ste- cluded: procalcitonin (mp [multiple post- Web-based] or the use of sequentially

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1323

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

Meta-Analyses guidelines.20 All calcula-

tions were performed using commer-

120 Articles identified by search of EMBASE,

MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of cially available software (STATA, ver-

Controlled Trials, and trial registries and references sion 9.2 [StataCorp LP, College Station,

Texas] and RevMan, version 5.1 [Coch-

76 Articles excluded rane Collaboration]).

45 Not directly related to the topic being reviewed

13 Not RCTs

4 In pediatric populations

14 Ongoing trials RESULTS

44 Articles met eligibility criteria and

were reviewed in full LITERATURE SEARCH

AND QUALITY OF STUDIES

30 Articles excluded for being duplicates identified

by different databases searched

The literature searches of MEDLINE,

14 Articles included in final analysis EMBASE, and the Cochrane Cen-

tral Register of Controlled Trials and

mining of trial registries and refer-

Figure 1. Flowchart depicting the process of article selection. RCT indicates randomized controlled trial. ences yielded 120 potential results

(Figure 1). A total of 58 articles

Table 1. Quality of Studies a

were then excluded owing to non-

randomization and/or not focusing

Sequence Allocation Incomplete Selective

on our population of interest. Also,

Source Generation Concealment Masking Outcome Data Outcome Reporting we excluded 4 articles focusing on

Briel et al,14 2008 3 3 2 3 3

pediatric populations and 14 ongo-

Burkhardt et al,21 2010 2 2 2 3 3 ing trials, leaving 44 articles that we

Christ-Crain et al,22 2004 2 1 2 3 3 further assessed for eligibility. Af-

Christ-Crain et al,23 2006 3 2 1 3 3 ter exclusion of 2 duplicate publi-

Stolz et al,24 2007 2 1 2 3 3 cations in different journals and re-

Long et al,25 2009 1 1 1 2 3 dundantly identified articles from the

Kristoffersen et al,26 2009 2 1 1 3 3

different databases, 14 articles re-

Schuetz et al,15 2009 3 3 1 3 3

Svoboda et al,27 2007 3 2 2 2 2

mained. Review of the reference lists

Nobre et al,28 2008 3 2 2 2 3 from the 14 articles and those from

Stolz et al,29 2009 2 1 1 3 3 selected meta-analyses and reviews

Hochreiter et al,30 2009 2 1 1 3 2 regarding the topic yielded no ad-

Schroeder et al,31 2009 3 2 1 3 3 ditional trials. Thus, the final quan-

Bouadma et al,32 2010 3 3 2 3 3 titative analysis includes 14 RCTs.

a Evaluated using the methods of Higgins and Green.13 No other bias was applicable. 1, poor quality or not Table 1 shows the quality assess-

reporting; 2, unclear reporting; 3, excellent performance and reporting. ment of included trials with regard

to sequence generation, allocation

numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes was mon, and studies have balanced num- concealment, masking, incomplete

reported); adequate masking of physi- bers in intervention and control groups.17 outcome data, selective outcome re-

cians, patients, and outcome assessors; We tested for heterogeneity with the porting, and other biases. The meth-

low risk of attrition bias (ie, minimal loss Cochran Q test and measured the in- odological quality varied across in-

to follow-up and performance of ad- consistency (I 2 [the percentage of total cluded studies; only 3 trials could be

equate sensitivity analyses); and free- variance across studies that is due to considered at low risk for bias,

dom from selective outcome reporting heterogeneity rather than chance]) of in- namely, 1 in the primary care,14 1 in

(eg, if all stated outcomes were tervention effects across trials.18 Also, we

the ED,15 and 1 in the ICU setting.32

reported).13 Two of us (P.S. and M.B.) who performed sensitivity analyses compar-

were coauthors of eligible studies14,15 were ing trials with low risk of bias (ie, ad- The other studies lacked several qual-

excluded from reviewing our own work. equate sequence generation, allocation ity criteria and need to be consid-

concealment, and unlikely attrition bias) ered at high risk for bias. None of the

DATA SYNTHESIS vs trials at higher risk. We investigated studies managed to mask physicians

the presence of publication bias by with respect to treatment allocation

For all included RCTs, we report sum- means of funnel plots.19 Concerning an- of patients.

mary data, including antibiotic prescrip- tibiotic treatment, the different studies

tion rate, duration of antibiotic treat- were too few in number and lacked ad- STUDY SETTING, DESIGN,

ment, mortality rate, and adverse event equate consistency in reporting across

rate, as defined in the individual stud- study design and population for a pooled

AND PCT ALGORITHMS

ies. We pooled results and calculated analysis of antibiotic treatment data for

Table 2 summarizes clinical de-

odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence different diagnoses and settings. In-

intervals (CIs) for overall mortality rate stead, we summarized antibiotic expo- sign and study setting. It also dis-

using the Peto method.16 The Peto ORs sure and outcome data from the differ- plays the underlying diagnoses of pa-

are appropriate when intervention ef- ent studies grouped by clinical setting. tients, the study question, the PCT

fects are small (ie, when ORs are close This report adheres to the Preferred Re- algorithm used, and the outcomes

to 1), events are not particularly com- porting Items for Systematic Reviews and investigated of all included RCTs.

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1324

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

Table 2. Overview of Design and Content of the RCTs Grouped by Study Setting

Study Research

Source Design a Diagnosis Question Algorithm by PCT Level, µg/L Outcome

Primary Care Setting

Briel et al,14 Multicenter, Upper and Safety and reduction of Abx ⬍0.10, SRAA; 0.10-0.25, RAA; ⬎0.25, RFA; Primary: days with restricted

2008 noninferiority lower RTI with repeated PCT-level recheck PCT level at 6-24 h if no Abx activity in first 14 d

measurement? initiated Secondary: Abx exposure,

adverse events at day 28

Burkhardt Multicenter, Upper and Safety and reduction of Abx ⬍0.25, RAA; ⬎0.25, RFA Primary: days with significant

et al,21 2010 noninferiority lower RTI with single PCT-level health impairment at day 14

measurement? Secondary: Abx exposure

ED Settings

Christ-Crain ED only, single CAP, AECOPD, Reduction of Abx for lower ⬍0.10, SRAA; 0.10-0.25, RAA; 0.25-0.50, Primary: Abx prescriptions at

et al,22 2004 center bronchitis RTI with repeated CAP in RFA; ⬎0.50, SRFA; recheck PCT level day 14

ED with single PCT-level after 6-24 h if no Abx initiated Secondary: readmission,

measurement? relapse, QOL, cost

Christ-Crain ED and CAP Reduction of Abx for CAP ⬍0.10, SRAA; 0.10-0.25, RAA; 0.25-0.50, Primary: duration of Abx at

et al,23 2006 inpatient, with repeated PCT-level RAA; ⬎0.50, SRFA; recheck PCT level day 28

single center measurements? every 2 d; discontinue Abx with same Secondary: mortality, adverse

cutoffs outcomes

Stolz et al,24 ED and AECOPD Reduction of Abx for ⬍0.10, SRAA; 0.10-0.25, RAA; 0.25-0.50, Primary: Abx use in hospital and

2007 inpatient, AECOPD with repeated RFA; ⬎0.50, SRFA; retest PCT level every first 6 mo

single center PCT-level measurements? 2 d; discontinue Abx with same cutoffs Secondary: ICU, death, LOS,

AECOPD recurrence rate

Long et al,25 ED at 2 centers CAP Reduction of Abx for CAP in ⬍0.25, RAA; ⱖ0.25, RFA; if no Abx, retest Primary: Abx use within 28 d

2009 outpatients with repeated PCT at 8-12 h; recheck PCT every 3 d; Secondary: clinical recovery,

PCT-level measurements? discontinue Abx with same cutoffs treatment failure, cost of Abx

Kristoffersen ED and Lower RTI Reduction of Abx for lower ⬍0.25, RAA; 0.25-0.50, RFA; ⬎0.50, SRFA Primary: Abx use

et al,26 2009 inpatient, RTI with single PCT-level Secondary: adherence to

single center measurement? algorithm, mortality, ICU

Schuetz et al,15 ED and CAP, AECOPD, Safety, Abx use, and ⬍0.10, SRAA; 0.10-0.25, RAA; 0.25-0.50, Primary: noninferiority of

2009 inpatient, bronchitis feasibility in CAP, AECOPD, RFA; ⬎0.50, SRFA; retest PCT level every adverse outcomes at day 28

multicenter and bronchitis? 2 d; discontinue Abx with same cutoffs Secondary: duration of Abx

ICU and Inpatient Settings b

Svoboda et al,27 ICU, single Postop septic Improvement of outcomes ⬎2.00, change in use of Abx and catheters; Primary: ICU LOS, ICU mortality

2007 center shock after multiple traumas or ⬍2.00, ultrasonography and CT, followed rate, SOFA score, days using

major surgery? by surgery ventilator

Nobre et al,28 ICU, single Sepsis Reduction of Abx in ICU Discontinue Abx on day 5 when ⬍0.25 or Primary: duration of Abx

2008 center patients with sepsis? decrease of ⱖ90% from peak occurs Secondary: mortality rate and

LOS at day 28

Stolz et al,29 European and VAP Reduction of Abx in VAP in ⬍0.25, discontinue Abx; ⬍0.50 or decrease Primary: Abx-free days alive

2009 US ICU, different ICUs? of ⬎80%, consider discontinuing Abx;

multicenter ⬎0.50 or decreased ⬍80%, continue

Abx; ⬎1, continue Abx

Hochreiter ICU, single Postop with Reduction of Abx in postop Discontinue Abx if clinically improvement Primary: Abx use

et al,30 2009 center infection ICU patients with observed and ⬍1.00 or if decrease to Secondary: LOS

infection? 25%-35% of initial value for 3 d

observed

Schroeder ICU, single Postop with Reduction of Abx duration in Discontinue Abx if decrease to ⬍1.00 or Primary: Abx use

et al,31 2009 center severe sepsis severe sepsis in postop decrease by 25%-35% for 3 d observed Secondary: LOS, mortality rate

ICU patients?

Bouadma ICU, Sepsis Safety and reduction of Abx ⬍0.25, SRAA; 0.25-0.50, RAA; ⬎0.50-1.00, Primary: mortality rate at days

et al,32 2010 multicenter in ICU patients with RFA; ⬎1.00, SRFA; retest PCT level in 28 and 60, Abx use at day 28

sepsis? 6-12 h if Abx not initiated; discontinue

Abx when ⬍0.50 or decrease ⬎80%

from peak level observed

Abbreviations: Abx, antibiotics; AECOPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CT, computed

tomography; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; PCT, procalcitonin; Postop, postoperative; QOL, quality of life; RAA,

recommendation against use of antibiotics; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RFA, recommendation for use of antibiotics; RTI, respiratory tract infection; SICU, surgical

ICU; SOFA, sepsis-related organ failure assessment; SRAA, strong recommendation against use of antibiotics; SRFA, strong recommendation for use of antibiotics;

VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

a All trials test for superiority unless designated noninferiority.

b Mostly medical ICU patients, with some SICU and general inpatients.

Primary Care cal outcomes, focused on upper and the study by Briel et al14 used re-

lower respiratory tract infections, and peated PCT measurements and ad-

Two studies in the primary care set- used a similar PCT algorithm (ie, no dressed subjects’ activity limitations

ting were found.14,21 Both were non- antibiotics in patients with PCT levels and antibiotic exposure as out-

inferiority trials with regard to clini- of ⬍0.25 µg/L). However, although comes, the study by Burkhardt et al21

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1325

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

Table 3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes of the Different RCTs, Grouped by Study Setting

Mortality, Control

Total vs PCT Groups, Abx Use, Relative

Source Diagnoses No. No. Dead/Total (%) Control vs PCT Reduction, % Key Findings

Primary Care Settings

Briel et al,14 Upper and 458 1/226 (0.4) vs Prescription: 97% vs 25% Prescription: −74 Reduction of Abx without additional

2008 a lower RTI 0/232 (0) Duration (mean): 7.1 vs 6.2 d Duration: −13 days of restricted activity

Burkhardt Upper and 550 0/275 (0) vs Prescription: 36.7% vs 21.5% Prescription: −42 Reduction of Abx without causing

et al,21 2010 lower RTI 0/275 (0) Duration (mean): 7.7 vs 7.8 d Duration: 1 heath impairment

ED Settings

Christ-Crain CAP, AECOPD, 243 4/119 (3.4) vs Prescription: 83% vs 44% Prescription: −47 Reduction of Abx prescriptions

et al,22 2004 bronchitis 4/124 (3.2) Duration (mean): 12.8 vs 10.9 d Duration: −15

Christ-Crain CAP 302 20/151 (13.2) vs Prescription: 99% vs 85% Prescription: −14 Reduction of initiation and duration

et al,23 2006 18/151 (11.9) Duration (mean): 12.9 vs 5.8 d Duration: −55 of Abx without adverse

outcomes

Stolz et al,24 AECOPD 208 9/106 (8.5) vs Prescription: 72% vs 40% Prescription: −44 Reduced Abx exposure without

2007 5/102 (4.9) adverse outcome

Long et al,25 CAP 127 0/64 (0) vs Prescription: 97% vs 86% Prescription: −11 Reduction of Abx use and shorter

2009 0/63 (0) Duration (median): 10 vs 6 d Duration: −40 Abx duration

Kristoffersen Lower RTI 210 1/107 (0.9) vs Prescription: 79% vs 85% Prescription: 8 Reduction of duration of Abx use

et al,26 2009 2/103 (1.9) Duration (mean): 6.8 vs 5.1 d Duration: −25

Schuetz et al,15 CAP, AECOPD, 1359 33/688 (4.8) vs Prescription: 87.7% vs 75.4% Prescription: −14 Noninferiority for clinical outcomes

2009 bronchitis 34/671 (5.1) Duration (median): 8.7 vs 5.7 d Duration: −34 and decreased Abx use

Inpatient and ICU Settings

Svoboda et al,27 Postop septic 72 13/34 (38.2) vs NA NA Trend to decrease in SOFA and

2007 shock 10/38 (26.3) ventilator/ICU days

Nobre et al,28 Sepsis 79 12/40 (30.0) vs Duration (median): 9.5 vs 6.0 d Duration: −37 Reduction in Abx duration and ICU

2008 8/39 (20.5) LOS without adverse events

Stolz et al,29 VAP 101 12/50 (24.0) vs Abx-free days alive: 9.5 vs 13 Abx-free days Decreased Abx use without

2009 8/51 (15.7) Duration (median): 15 vs 10 d alive: 27 increasing mortality rate

Duration: −33

Hochreiter Postop 110 14/53 (26.4) vs Duration (mean): 7.9 vs 5.9 d Duration: −25 Reduction in Abx duration and ICU

et al,30 2009 patients with 15/57 (26.3) LOS without adverse events

infection

Schroeder Postop severe 27 3/13 (23.1) vs Duration (mean): 8.3 vs 6.6 d Duration: −20 Shorter Abx duration

et al,31 2009 sepsis 3/14 (21.4)

Bouadma Sepsis 621 64/314 (20.4) vs Abx-free days alive: 11.6 vs 14.3 Abx-free days Reduction in Abx use without

et al,32 2010 b 65/307 (21.2) Duration (mean): 9.9 vs 6.6 d alive: 19 increase in mortality rate

Duration: −33

Abbreviations: NA, not available. Other abbreviations: See Table 2.

a Indicates intention-to-treat analysis.

b Indicates 28-day mortality.

only measured PCT levels once on ad- Intensive Care Unit studies were multicenter trials,29,32

mission but also measured health im- and the trial by Bouadma et al32 was

pairment and antibiotic exposure. In the ICU setting, 6 RCTs were a noninferiority trial in terms of mor-

identified27-32 that differed substan- tality rate and adverse outcomes. An-

Emergency Department tially in terms of underlying diag- tibiotic exposure, length of stay, and

noses (ie, postoperative infections in mortality rate were the most com-

A total of 6 studies in the ED set- the SICU, severe sepsis and/or sep- monly reported outcomes.

ting were identified.15,22-26 All stud- tic shock, and ventilator-associated

ies used a similar PCT algorithm (ie, pneumonia) and the PCT cutoffs EFFICACY AND

no initiation of Abx or, if already ini- used. All studies based their recom- CLINICAL OUTCOMES

tiated, discontinuation of Abx in pa- mendation primarily on repeated

tients with PCT levels of ⬍0.25 µg/ PCT measurements and specified Overall, a total of 4467 patients were

L). Two studies22,26 measured PCT discontinuing Abx when PCT lev- included in the 14 RCTs (ie, 2240 in

levels only on admission, and the re- els dropped to a range of less than the control group and 2227 in the

maining 4 studies15,23-25 used re- 0.25 to less than 1.00 µg/L or by at PCT group). Table 3 displays the de-

peated measurements. All studies re- least 80% to 90%. One study27 did tailed results of all RCTs with regard

ported antibiotic exposure and not focus on de-escalation of anti- to the number of included patients

patient outcomes, but only the trial biotics but specified to change an- and underlying diagnoses, mortality

by Schuetz et al15 was powered for tibiotics or to perform a diagnostic rate, absolute and relative antibiotic

noninferiority with regard to clini- workup if PCT levels did not de- prescription rates, and duration be-

cal outcomes. crease by an adequate amount. Two tween the 2 groups. Overall, no sig-

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1326

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

PCT Algorithm No PCT Algorithm

Fixed, Peto OR Peto Fixed OR

Study or Subgroup Events Total Events Total Weight, % (95% CI) (95% CI)

1.1.1 Primary care trials

Briel et al,14 2008 0 232 1 226 0.3 0.13 (0-6.64)

Burkhardt et al,21 2010 0 275 0 275 Not estimable

Subtotal 507 501 0.3 0.13 (0-6.64)

Total No. of events 0 1

Heterogeneity: not applicable

Test for overall effect: z = 1.01; P = .31

1.1.2 Emergency department trials

Christ-Crain et al,22 2004 4 124 4 119 2.6 0.96 (0.23-3.91)

Christ-Crain et al,23 2006 18 151 20 151 11.2 0.89 (0.45-1.75)

Stolz et al,24 2007 5 102 9 106 4.4 0.57 (0.19-1.67)

Kristoffersen et al,26 2009 2 103 1 107 1.0 2.04 (0.21-19.81)

Schuetz et al,15 2009 34 671 33 688 21.4 1.06 (0.65-1.73)

Long et al,25 2009 0 63 0 64 Not estimable

Subtotal 1214 1235 40.6 0.95 (0.67-1.36)

Total No. of events 63 67

Heterogeneity: χ42 = 1.54; P = .82; I 2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: z = 0.27; P = .78

1.1.3 Intensive care unit trials

Svoboda et al,27 2007 10 38 13 34 5.3 0.58 (0.22-1.56)

Nobre et al,28 2008 8 39 12 40 5.1 0.61 (0.22-1.67)

30

Hochreiter et al, 2009 15 57 14 53 7.2 0.99 (0.43-2.32)

29

Stolz et al, 2009 8 51 12 50 5.4 0.60 (0.22-1.58)

Schroeder et al,31 2009 3 14 3 13 1.6 0.91 (0.15-5.42)

32

Bouadma et al, 2010 65 307 64 314 34.4 1.05 (0.71-1.55)

Subtotal 506 504 59.1 0.89 (0.66-1.20)

Total No. of events 109 118

Heterogeneity: χ53 = 2.67; P = .75; I 2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: z = 0.76; P = .45

Total 2227 2240 100.0 0.91 (0.73-1.14)

Total No. of events 172 186

Heterogeneity: χ112 = 5.22; P = .92; I 2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: z = 0.81; P = .42

Test for subgroup differences: χ22 = 1.01; P = .60; I 2 = 0%

0.01 0.10 1.00 10.00 100.00

Favors PCT Favors No PCT

Algorithm Algorithm

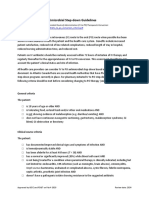

Figure 2. Mortality rate in the procalcitonin (PCT) and control groups. The forest plot depicts the Peto odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs),

comparing patients treated in the PCT and control groups in different trials and clinical settings.

nificant difference was observed in ment duration. In both trials, no dif- ond study by Christ-Crain et al,23 a

mortality in patients in the PCT ferences were observed in the pri- 40% reduction in the study by Long

groups (172 of 2227 [7.7%]) com- mary safety end points (ie, days with et al,25 and a 34% reduction in the

pared with the control group (186 of restricted activities and days with trial by Schuetz et al15). The study

2240 [8.3%]), with a summary OR health impairment within a 14-day by Kristoffersen et al26 had similar

of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.73-1.14) follow-up) between the controls and antibiotic prescription rates but a

(Figure 2). We found no evidence the PCT-group patients. The mortal- 25% reduction in the duration of

of relevant heterogeneity among ity rate in both trials was similarly low antibiotic therapy. Those authors

trials. The analysis for publication bias in both groups (OR, 0.13; 95% CI, noted, however, that physicians were

indicated no evidence of such bias for 0-6.64) (Figure 2). not asked to wait for PCT results be-

mortality rate (eFigure 1; http://www fore initiating antimicrobial therapy.

.archinternmed.com). Emergency Department Therefore, PCT values were, in most

The 6 ED trials15,22-26 included a total cases, used to motivate cessation or

Primary Care

of 2449 patients, mostly with com- continuation of already-initiated

The 2 primary care trials included a munity-acquired pneumonia and treatments.

total of 1008 patients with upper and AECOPD. For community-ac- For patients with AECOPD, the

lower respiratory tract infections. The quired pneumonia, the main effect of trial by Stolz et al24 found a 44% re-

study by Briel et al,14 which used re- using PCT was to shorten the dura- duction in prescription rates. The

peated PCT measurements, found a tion of antibiotic treatment. Trials patients with COPD guided by a

74% reduction in antibiotic prescrip- using only a single initial PCT mea- PCT-based algorithm included by

tion and a 13% reduction in mean an- surement had less effect on dura- Christ-Crain et al22 and Schuetz et

tibiotic duration. However, the study tion of antibiotic therapy (ie, a 15% al15 also had lower prescription rates

by Burkhardt et al21 only used a single reduction in the first study by Christ- compared with controls (ie, 87% vs

PCT measurement at admission and Crain et al22) compared with those 38% and 70% vs 49%, respectively).

found a 42% reduction in antibiotic requiring repeated PCT measure- In none of the ED trials was an in-

exposure but not a reduction in treat- ments (ie, a 55% reduction in the sec- crease in adverse outcomes noted,

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1327

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

although only the trial by Schuetz et nia and sepsis in the hospital and ICU The algorithms in the included

al was powered for this end point. settings. Critically, none of the trials studies varied moderately. Never-

Within all ED trials, mortality in PCT reported an increase in adverse out- theless, a few commonalities can be

groups was 5.2% (63 of 1214) com- comes, including mortality rate, al- identified. First, regarding the most

pared with 5.4% (67 of 1235) in con- though only a subset of the included severe diseases (eg, sepsis and pneu-

trol groups (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.67- trials were powered to detect changes monia) or the highest-acuity care set-

1.36) (Figure 2). in clinical outcomes. tings (ie, the ICU and the hospital),

Given the limited number of stud- PCT levels were not used to deter-

Intensive Care Unit ies included across a breadth of di- mine whether antibiotic therapy

agnoses and settings in this analysis should be initiated but when to dis-

The 2 ICU trials that focused on pa- and the limited methodological qual- continue it. Second, the decrease of

tients with severe sepsis/septic shock ity of many of the included studies elevated PCT levels appears to cor-

(ie, Nobre et al28 and Bouadma et al32) (ie, their being at high risk for bias), relate adequately with sufficient reso-

found reductions in antibiotic expo- caution must be used when general- lution of bacterial infections to al-

sure of 37% and 33%, respectively. izing these findings. Although it is re- low for the safe discontinuation of

The trial by Svoboda et al27 did not assuring to note the uniform ab- antibiotic therapy, even if this dis-

report antibiotic exposure because it sence of adverse events paralleling the continuation occurs before the tradi-

only focused on patient outcomes. similarly uniform presence of anti- tional length of a typical course of

The trial reported by Stolz et al29 in- biotic use reduction across the stud- antibiotics has elapsed. Third, in

cluded only patients with ventilator- ies, further data are needed before lower-acuity settings (eg, the pri-

associated pneumonia and found a PCT-based algorithms should be con- mary care setting) or with clinical

27% increase in antibiotic-free days sidered the criterion standard of care, entities that are generally less im-

alive. Two trials30,31 focused on pa- especially for diagnoses such as ven- minently dangerous (eg, bronchi-

tients with postoperative infection tilator-associated pneumonia or post- tis), PCT values may be used to as-

and sepsis; they reported reductions operative infection, in which ran- sist in the initial determination of

of antibiotic exposure by 20% and domized trial data are limited. Clearly, whether antibiotics should be pre-

25%, respectively. None of the stud- the most robust data are for pneu- scribed at all. However, all patients

ies reported a difference in mortality monia; in this diagnosis, as with the should undergo reassessment in

rate or adverse outcome, but only the others, the findings are promising. cases in which Abx are withheld to

study by Bouadma et al32 was pow- Previous meta-analyses have in- ensure that the clinical condition im-

ered for noninferiority. Within all ICU vestigated the use of PCT levels for proves spontaneously in a clini-

trials, mortality in the PCT group pa- detection of sepsis in adult pa- cally appropriate period.

tients was 21.5% (109 of 506), com- tients33-37 and children38 from obser- Most of the studies of PCT-based

pared with 23.4% (118 of 504) in vational studies. Also, 3 previous algorithmic approaches to antibi-

standard group patients (OR, 0.89; meta-analyses focused on random- otic management of respiratory tract

95% CI, 0.66-1.20) (Figure 2). A sen- ized trials only to investigate the mea- infections have been conducted in Eu-

sitivity analysis contrasting the 3 trials surement of PCT levels for antibi- rope. Despite the recognized impor-

at low risk of bias14,15,32 with the re- otic decisions in the critical care tance of antibiotic stewardship and

maining higher-risk trials yielded setting39,40 and in patients with sus- health care cost containment in the

similar results (eFigure 2A and B). pected bacterial infections.41 Our sys- United States,3,4 further studies in a

tematic review included all pub- US population may be needed to as-

lished RCTs that investigated PCT suage concerns regarding practice and

COMMENT algorithms for antibiotic treatment de- population differences. Therefore, we

cisions concerning escalation and de- recommend the PCT algorithms de-

Within this systematic review, we ad- escalation of dosage in adult pa- scribed herein for use in future US

dress the question of the safety and tients with respiratory tract infections studies. However, algorithms for

efficacy of using a PCT-based algo- and sepsis from primary care, ED, and PCT use, much like those for other

rithm for antibiotic therapy deci- ICU settings. We focus our analysis biomarkers, should supplement and

sions in patients with respiratory tract on the differences in PCT algo- not supplant clinical impressions.

infections and sepsis using data de- rithms used for low-, moderate-, and

rived from previous RCTs. We found high-acuity patients; this is a basis for LOW RISK/LOW ACUITY

a marked reduction in antibiotic ex- future trials aiming at reducing an-

posure in all settings, levels of dis- tibiotic overconsumption and it may For patients with a low pretest prob-

ease acuity, and patient popula- be of particular importance for prac- ability of contracting a bacterial in-

tions. This reduction occurred ticing physicians who want to in- fection (eg, patients with nonpneu-

because of lower prescription rates in clude PCT findings in their hospital monic upper and lower respiratory

low-acuity infections such as bron- protocols. Owing to differences of tract infection treated in the pri-

chitis, exacerbation of AECOPD in PCT levels in different clinical set- mary care setting), a single measure-

primary care and ED settings, and tings and patient populations, the cor- ment of PCT level and a cutoff rang-

shorter duration of antibiotic courses rect and safe practical use of this ing from less than 0.10 to less than

in moderate- and high-acuity pa- marker will likely vary with the level 0.25 µg/L appears to be an appro-

tients, such as those with pneumo- of disease acuity in patients. priate, safe, and simple approach in

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1328

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

this setting to determine the need for

antibiotics. Clinical follow-up with re- A

measurement of PCT should be per- Evaluation at time of admission

formed in all patients in whom Abx PCT result < 0.10 µg/L < 0.25 µg/L ≥ 0.25 µg/L > 0.50 µg/L

were withheld and who show no Recommendation Strongly Discouraged Encouraged Strongly

clinical improvement (Figure 3A). regarding use of Abx discouraged encouraged

Overruling Consider use of antibiotics if patients are clinically

MODERATE RISK/ the algorithm unstable, have strong evidence of pneumonia,

are at high risk (ie, COPD GOLD III-IV),

MODERATE ACUITY or need hospitalization

Follow-up/other Follow-up only needed if no symptom Clinical reevaluation as appropriate

For patients who are clinically stable comments resolution after 1 to 2 days; if clinical

situation is not improving; consider Abx

and are treated at the ED or are hos- if PCT level increases to ≥ 0.25 µg/L

pitalized with pneumonia, the initia-

tion of antibiotic therapy should be B

based on clinical grounds and a PCT

Evaluation at time of admission

threshold of at least 0.25 µg/L, as-

suming the PCT results can be ob- PCT result < 0.10 µg/L < 0.25 µg/L ≥ 0.25 µg/L > 0.50 µg/L

tained expeditiously. In patients with Recommendation Strongly Discouraged Encouraged Strongly

regarding use of Abx discouraged encouraged

an initial PCT level of no higher than Overruling Consider alternative diagnosis, or Abx

0.25 µg/L, alternative diagnoses (eg, the algorithm if patients are clinically unstable,

are at high risk for adverse outcome

viral infection and pulmonary em- (eg, PSI classes IV-V, immunosupression),

bolism) should be considered. There- or have strong evidence of a bacterial pathogen

after, repeated measurement of PCT Follow-up/other Reassess patients’ condition and recheck Recheck PCT level every 2 to 3 days to

comments PCT level after 6 to 12 hours if no clinical consider early cessation of Abx

levels every other day should occur, improvement is observed

with directions to discontinue anti-

Follow-up evaluation every 2 to 3 days

biotic therapy when PCT levels drop

PCT result < 0.10 µg/L < 0.25 µg/L ≥ 0.25 µg/L > 0.50 µg/L

to less than 0.25 µg/L or by at least

Recommendation Cessation of Cessation of Cessation of Cessation of

80% to 90% of the peak value and regarding use of Abx therapy strongly therapy therapy therapy strongly

when the patient has improved clini- encouraged encouraged discouraged discouraged

cally. If Abx are withheld initially, al- Overruling Consider continuation of Abx if patients

the algorithm are clinically not stable

gorithms should suggest retesting

Follow-up/other Clinical reevaluation as appropriate Consider treatment to have failed if PCT

PCT levels 6 to 12 hours after the ini- comments level does not decrease adequately

tial measurement (Figure 3B).

C

HIGH RISK/HIGH ACUITY

Evaluation at time of admission

In high-risk or ICU patients with sus- PCT result < 0.25 µg/L < 0.50 µg/L ≥ 0.50 µg/L > 1.0 µg/L

pected sepsis, algorithms should dic- Recommendation Strongly Discouraged Encouraged Strongly

regarding use of Abx discouraged encouraged

tate that empirical antibiotic therapy

Overruling Empirical therapy recommended in all patients with clinical suspicion of infection

not be delayed for PCT measure- the algorithm

ment. Periodic monitoring of PCT Follow-up/other Consider alternative diagnosis; reassess Reassess patients’ condition and recheck

levels after initiation of antibiotic comments patients condition and recheck PCT level PCT level every 2 days to consider

every 2 days cessation of Abx

therapy may be the preferred strat- Follow-up evaluation every 1 to 2 days

egy, and a drop of PCT levels to less

PCT result < 0.25 µg/L or < 0.50 µg/L or ≥ 0.50 µg/L > 1.0 µg/L

than 0.50 µg/L or by at least 80% to drop by > 90% drop by > 80%

90% from baseline in patients who Recommendation Cessation Cessation of Abx Cessation of Abx Cessation

show a clinical improvement after regarding use of Abx of Abx strongly encouraged discouraged of Abx strongly

encouraged discouraged

therapy are reasonable thresholds for Overruling Consider continuation of Abx if patients are

cessation of antibiotic therapy in this the algorithm clinically unstable

fragile population (Figure 3C). For Follow-up/other Clinical reevaluation as appropriate Consider treatment to have failed if PCT

postoperative patients in the SICU, comments level does not decrease adequately

a decrease in PCT level to less than

1.0 µg/L may be sufficient to discon- Figure 3. Proposed algorithms for use of procalcitonin (PCT) values to determine antibiotic treatment of

infections. A, An algorithm for low-acuity nonpneumonic infections (ie, low risk) in primary care and

tinue Abx. As with moderate risk/ emergency department (ED) settings. B, Algorithm for moderate-acuity pneumonic infections (ie, moderate

moderate acuity algorithms, if Abx is risk) in hospital and ED settings; C, Algorithm for high-acuity infections (ie, high risk; sepsis) in intensive care

withheld initially based on a low PCT unit settings. Abx indicates antibiotics; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD, Global Initiative

level, a second measurement should for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; PSI, pneumonia severity index.

be obtained within 6 to 12 hours.

LIMITATIONS RCTs in an attempt to minimize bias, clusion may have led to the inad-

it excluded a reasonably large body vertant omission of relevant find-

Our review has a number of limita- of literature pertaining to PCT that ings. Second, although we conducted

tions. First, because it is limited to did not derive from RCTs. This ex- an extensive literature search for

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1329

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

RCTs on the topic and a funnel plot santésuisse and the Gottfried and Ju- mediated calcitonin gene-related peptide and ad-

renomedullin expression in human adipose tissue.

did not suggest the presence of pub- lia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation.

Endocrinology. 2005;146(6):2699-2708.

lication bias, such a bias cannot defi- Online-Only Material: The eFig- 12. Müller B, Peri G, Doni A, et al. High circulating lev-

nitely be ruled out. Third, the meth- ures are available at http://www els of the IL-1 type II decoy receptor in critically ill

odological quality of most included .archinternmed.com. patients with sepsis: association of high decoy re-

trials was low to moderate. How- Additional Contributions: Qing ceptor levels with glucocorticoid administration.

J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72(4):643-649.

ever, a sensitivity analysis focusing Wang, PhD, of the Basel Institute for 13. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Assessing risk of bias

on 3 trials at low risk for bias yielded Clinical Epidemiology, University in included studies. In: Cochrane Handbook for Sys-

similar results, and no evidence was Hospital Basel, Switzerland, helped tematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0.

observed of heterogeneity among ef- with the translation of an article pub- March 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook

fects on mortality rate. lished in Chinese. Carole Foxman, .org. Accessed April 21, 2011.

14. Briel M, Schuetz P, Mueller B, et al. Procalcitonin-

In conclusion, this systematic re- MA, MS, Coordinator for Education guided antibiotic use vs a standard approach for

view of mostly moderate-quality and Database Services/Research acute respiratory tract infections in primary care.

RCTs suggests that the use of PCT- Liaison at the Treadwell Library, Mas- Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):2000-2007; dis-

guided algorithms for antibiotic sachusetts General Hospital, as- cussion, 2007-2008.

therapy decisions in patients with re- sisted with the EMBASE and Coch- 15. Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al; Pro-

HOSP Study Group. Effect of procalcitonin-based

spiratory tract infections, including rane Central Register of Controlled guidelines vs standard guidelines on antibiotic use

bronchitis, AECOPD, and pneumo- Trials database searches. in lower respiratory tract infections: the ProHOSP

nia and in patients with sepsis ap- randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302

pears to be effective at reducing use (10):1059-1066.

of Abx without sacrificing patient REFERENCES 16. Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P.

Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarc-

safety. These types of algorithms also tion: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Car-

appear to be useful in different clini- 1. Yealy DM, Fine MJ. Measurement of serum pro-

diovasc Dis. 1985;27(5):335-371.

calcitonin: a step closer to tailored care for respi-

cal settings. Based on the available ratory infections? JAMA. 2009;302(10):1115-

17. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Peto odds ratio method

evidence, we have proposed PCT al- [chapter 9.4.4.2]. In: Cochrane Handbook for Sys-

1116.

tematic Reviews on Interventions, Version 5.1.0.

gorithms based on clinical acuity lev- 2. Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, et al; Active Bac-

March 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook

els, which should be used in future terial Core Surveillance Program of the Emerging

.org. Accessed April 21, 2011.

Infections Program Network. Increasing preva-

large multicenter trials within the lence of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneu-

18. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG.

United States, powered for patient moniae in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2000;

Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ.

outcomes and aimed at reducing an- 343(26):1917-1924. 2003;327(7414):557-560.

19. Sterne JAC, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic re-

tibiotic overconsumption. 3. Roberts RR, Hota B, Ahmad I, et al. Hospital and

views in health care: investigating and dealing with

societal costs of antimicrobial-resistant infections

in a Chicago teaching hospital: implications for an- publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ.

Accepted for Publication: May 10, tibiotic stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(8): 2001;323(7304):101-105.

2011. 1175-1184. 20. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA

Correspondence: Philipp Schuetz, 4. Ohl CA, Luther VP. Antimicrobial stewardship for Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic re-

inpatient facilities. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(suppl views and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement.

MD, MPH, Department of Emer- Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-269, W264.

1):S4-S15.

gency Medicine, Harvard School of 5. Becker KL, Nylén ES, White JC, Müller B, Snider 21. Burkhardt O, Ewig S, Haagen U, et al. Procalcito-

Public Health, 667 Huntington Ave, RH Jr. Procalcitonin and the calcitonin gene fam- nin guidance and reductions of antibiotic use in

Boston, MA 02115 (philipp.schuetz ily of peptides in inflammation, infection, and sep- acute respiratory tract infection. Eur Respir J. 2010;

@post.harvard.edu). sis: a journey from calcitonin back to its precur- 36(3):601-607.

sors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1512- 22. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al.

Author Contributions: Study con- Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibi-

1525.

cept and design: Schuetz, Green- 6. Müller F, Christ-Crain M, Bregenzer T, et al; Pro- otic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract in-

wald, and Chiappa. Acquisition of HOSP Study Group. Procalcitonin levels predict bac- fections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded inter-

data: Schuetz, Greenwald, Chiappa, teremia in patients with community-acquired pneu- vention trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):600-607.

monia: a prospective cohort trial. Chest. 2010; 23. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Procal-

and Briel. Analysis and interpreta-

138(1):121-129. citonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-

tion of data: Schuetz, Greenwald, 7. Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Procalcitonin acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J

Chiappa, and Briel. Drafting of the and other biomarkers to improve assessment and Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(1):84-93.

manuscript: Schuetz and Green- antibiotic stewardship in infections: hope for hype? 24. Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibi-

wald. Critical revision of the manu- Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(23-24):318-326. otic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a random-

8. Karlsson S, Heikkinen M, Pettilä V, et al; Finnsep- ized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-

script for important intellectual con- guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;

sis Study Group. Predictive value of procalcito-

tent: Schuetz, Greenwald, Chiappa, nin decrease in patients with severe sepsis: a pro- 131(1):9-19.

and Briel. Statistical analysis: Schuetz spective observational study. Crit Care. 2010; 25. Long W, Deng XQ, Tang JG, et al. The value of

and Briel. 14(6):R205. doi:10.1186/cc9327. serum procalcitonin in treatment of community

Financial Disclosure: Dr Schuetz 9. Gogos CA, Drosou E, Bassaris HP, Skoutelis A. acquired pneumonia in outpatient [in Chinese].

Pro- versus anti-inflammatory cytokine profile in Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2009;48(3):216-219.

was supported by research grant patients with severe sepsis: a marker for prog- 26. Kristoffersen KB, Søgaard OS, Wejse C, et al.

PASMP3-127684/1 from the Swiss nosis and future therapeutic options. J Infect Dis. Antibiotic treatment interruption of suspected lower

Foundation for Grants in Biology 2000;181(1):176-180. respiratory tract infections based on a single pro-

and Medicine and received support 10. Linscheid P, Seboek D, Nylen ES, et al. In vitro calcitonin measurement at hospital admission: a

from BRAHMS USA Inc and bio- and in vivo calcitonin I gene expression in paren- randomized trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;

chymal cells: a novel product of human adipose 15(5):481-487.

Mérieux to attend meetings and to tissue. Endocrinology. 2003;144(12):5578-5584. 27. Svoboda P, Kantorová I, Scheer P, Radvanova J,

fulfill speaking engagements. Dr 11. Linscheid P, Seboek D, Zulewski H, Keller U, Mül- Radvan M. Can procalcitonin help us in timing of

Briel is supported by grants from ler B. Autocrine/paracrine role of inflammation- re-intervention in septic patients after multiple

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1330

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

trauma or major surgery? Hepatogastroenterology. tients’ exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units JA. Procalcitonin test in the diagnosis of bacter-

2007;54(74):359-363. (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised con- emia: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;

28. Nobre V, Harbarth S, Graf J-D, Rohner P, Pugin J. trolled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9713):463-474. 50(1):34-41.

Use of procalcitonin to shorten antibiotic treatment 33. Simmonds MC, Higgins JP, Stewart LA, Tierney 38. Yu Z, Liu J, Sun Q, Qiu Y, Han S, Guo X. The accu-

duration in septic patients: a randomized trial. Am J JF, Clarke MJ, Thompson SG. Meta-analysis of in- racy of the procalcitonin test for the diagnosis of

Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(5):498-505. dividual patient data from randomized trials: a re- neonatal sepsis: a meta-analysis. Scand J Infect Dis.

29. Stolz D, Smyrnios N, Eggimann P, et al. Procal- view of methods used in practice. Clin Trials. 2005; 2010;42(10):723-733.

citonin for reduced antibiotic exposure in ventilator- 2(3):209-217. 39. Kopterides P, Siempos II, Tsangaris I, Tsantes A,

associated pneumonia: a randomised study. Eur 34. Uzzan B, Cohen R, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Perret Armaganidis A. Procalcitonin-guided algorithms of

Respir J. 2009;34(6):1364-1375. G-Y. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic test for sepsis antibiotic therapy in the intensive care unit: a sys-

30. Hochreiter M, Köhler T, Schweiger AM, et al. in critically ill adults and after surgery or trauma: tematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

Procalcitonin to guide duration of antibiotic therapy a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2229-

in intensive care patients: a randomized prospec- Med. 2006;34(7):1996-2003. 2241.

tive controlled trial. Crit Care. 2009;13(3):R83. doi: 35. Tang BM, Eslick GD, Craig JC, McLean AS. Accu- 40. Heyland DK, Johnson AP, Reynolds SC, Mus-

10.1186/cc7903. racy of procalcitonin for sepsis diagnosis in criti- cedere J. Procalcitonin for reduced antibiotic ex-

31. Schroeder S, Hochreiter M, Koehler T, et al. cally ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. posure in the critical care setting: a systematic re-

Procalcitonin (PCT)-guided algorithm reduces Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(3):210-217. view and an economic evaluation [published online

length of antibiotic treatment in surgical inten- 36. Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK, Saint-Louis P, La- February 24, 2011]. Crit Care Med. doi:10.1097

sive care patients with severe sepsis: results of a croix J. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive pro- /CCM.0b013e3182120a5.

prospective randomized study. Langenbecks Arch tein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a sys- 41. Tang H, Huang T, Jing J, Shen H, Cui W. Effect of

Surg. 2009;394(2):221-226. tematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. procalcitonin-guided treatment in patients with in-

32. Bouadma L, Luyt C-E, Tubach F, et al; PRORATA 2004;39(2):206-217. fections: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

trial group. Use of procalcitonin to reduce pa- 37. Jones AE, Fiechtl JF, Brown MD, Ballew JJ, Kline Infection. 2009;37(6):497-507.

ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 15), AUG 8/22, 2011 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1331

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Corrected on August 18, 2011

DownloadedViewFrom:

publicationhttp://archinte.jamanetwork.com/

stats on 02/25/2013

You might also like

- Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare 4th Edition Melnyk Test BankDocument4 pagesEvidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare 4th Edition Melnyk Test Bankqwivy.com33% (3)

- Written Report - 6.419x Module 1Document8 pagesWritten Report - 6.419x Module 1聂宝鹏No ratings yet

- CONSORT Checklist of Information To Include When Reporting A Randomised TrialDocument3 pagesCONSORT Checklist of Information To Include When Reporting A Randomised TrialJoko Tri WahyudiNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin and AB DecisionsDocument10 pagesProcalcitonin and AB DecisionsDennysson CorreiaNo ratings yet

- Rab 8Document21 pagesRab 8Belia DestamaNo ratings yet

- 10.1515 - CCLM 2022 1072Document7 pages10.1515 - CCLM 2022 1072ENFERMERIA EMERGENCIANo ratings yet

- Effect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticDocument11 pagesEffect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticRaul ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Hochreiter2009 PDFDocument7 pagesHochreiter2009 PDFmr_curiousityNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial ResistanceDocument11 pagesAntimicrobial Resistanceapi-253312159No ratings yet

- Golden Hour CCM Arthur Van Zanten IC1Document3 pagesGolden Hour CCM Arthur Van Zanten IC1Sara NicholsNo ratings yet

- Abdul Aziz2015 PDFDocument18 pagesAbdul Aziz2015 PDFSambit DashNo ratings yet

- Jiaa 221Document13 pagesJiaa 221AndradaLavricNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Strategies in Severe Nosocomial Sepsis: Why Do We Not De-Escalate More Often?Document7 pagesAntibiotic Strategies in Severe Nosocomial Sepsis: Why Do We Not De-Escalate More Often?Anonymous 2kPiJhIlFNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics 11 00022Document16 pagesAntibiotics 11 00022Putri RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- CAP Treatamnet AcortadoDocument8 pagesCAP Treatamnet Acortadoapi-3707490No ratings yet

- Association Between Immune-Related Adverse Event TDocument8 pagesAssociation Between Immune-Related Adverse Event TAndrew FincoNo ratings yet