Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Desordenes Testiculares Agudos

Desordenes Testiculares Agudos

Uploaded by

Hernan Del CarpioOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Desordenes Testiculares Agudos

Desordenes Testiculares Agudos

Uploaded by

Hernan Del CarpioCopyright:

Available Formats

Acute Testicular Disorders

John M. Gatti and J. Patrick Murphy

Pediatr. Rev. 2008;29;235-241

DOI: 10.1542/pir.29-7-235

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/29/7/235

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2008 by the American Academy of

Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0191-9601. Online ISSN: 1526-3347.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

Article genital system

Acute Testicular Disorders

John M. Gatti, MD,*

Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to:

J. Patrick Murphy, MD†

1. Describe the appropriate evaluation and management of the acute scrotum.

2. Discern testicular torsion from other, less urgent conditions that may mimic it.

Author Disclosure 3. Discuss the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment of testicular torsion for

Drs Gatti and Murphy gonadal salvage.

have disclosed no

financial relationships

relevant to this

Introduction

Acute scrotal pain with or without swelling and erythema in the child or adolescent male

article. This

should be treated as an emergent condition. The differential diagnosis includes: torsion of

commentary does not the spermatic cord, appendix testis or epididymis, epididymitis/orchitis, hernia, hydrocele,

contain a discussion trauma, sexual abuse, tumor, idiopathic scrotal edema (dermatitis/insect bite), cellulitis,

of an unapproved/ and vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein purpura). Most of the conditions are nonemergent, but

investigative use of a the prompt diagnosis and treatment of torsion of the spermatic cord is imperative to avoid

permanent ischemic damage to the testicle. The most common causes of acute scrotal pain

commercial

are testicular (spermatic cord) torsion and torsion of the rudimentary vestigial appendages

product/device.

of the testicle or epididymis. The child’s age suggests the cause of the acutely painful

scrotum because torsion of the appendix testes/epididymis is more common in prepuber-

tal boys and spermatic cord torsion occurs more frequently in adolescents and newborns.

Testicular Torsion

Torsion of the testicle results from twisting of the spermatic cord, which compromises

testicular blood supply. The number of twists determines the amount of vascular impair-

ment, although generally a 4- to 8-hour window exists before significant ischemic damage

occurs that can affect long-term testicular morphology and sperm formation. Testicular

torsion is a true surgical emergency. Adolescent males tend to present beyond the

“golden” 4- to 8-hour period, but urgent surgical treatment is indicated because viability

of the testis is difficult to predict.

Two types of testicular torsion may occur. Extravaginal torsion results from twisting of

the cord proximal to the tunica vaginalis. This mechanism occurs perinatally during

descent of the testicle before the scrotal investment of the tunica vaginalis has taken place,

allowing the tunica and testis to spin on their vascular pedicles. The tunica vaginalis likely

becomes adherent to the surrounding tissues by 6 weeks of age.

Intravaginal torsion occurs beyond the perinatal period and can result from abnormal

fixation of the testicle and epididymis within the tunica vaginalis. Normally, the tunica

invests the epididymis and posterior surface of the testicle, which fixes it to the scrotum and

prevents it from twisting (Fig. 1). If the tunica vaginalis attaches in a more proximal

position on the spermatic cord, the testicle and epididymis hang free in the scrotum and

can twist within the tunica vaginalis. Such abnormal fixation is described classically as the

“bell-clapper” deformity and occurs in only a minority of males (Fig. 2). This type of

deformity is common, as discerned by autopsy studies, and usually is bilateral. Because

testicular torsion occurs relatively infrequently, other factors also play a role in its

occurrence.

Rapid growth and increasing vascularity of the testicle also may be precursors to torsion.

*Associate Professor, University of Missouri at Kansas City School of Medicine; Director, Minimally Invasive Urology, Children’s

Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Kan.

†

Professor, University of Missouri at Kansas City School of Medicine; Chief, Section of Urology, Children’s Mercy Hospital,

Kansas City, Kan.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.29 No.7 July 2008 235

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

genital system acute testicular disorders

ular torsion. The pain usually is unrelenting, but seem-

ingly minimal pain may occur in patients who are very

stoic or when the torsion has been longstanding. A his-

tory of previous bouts of intermittent testicular pain may

be given and likely represents previous intermittent tor-

sion and detorsion.

The physical examination should include an investiga-

tion of the abdomen, inguinal area, and scrotum. The

abdomen and inguinal area should be inspected for other

causes of scrotal pain, such as an inguinal hernia. De-

pending on the duration of the torsion, the scrotum can

show various degrees of erythema and induration. If

landmarks are still present, the involved testicle may be

riding higher, have a transverse orientation, or have the

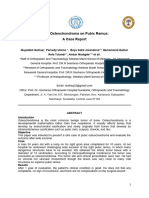

Figure 1. Intraoperative example of testicle that has a normal, epididymis located anteriorly. The cremasteric reflex fre-

wide mesentery (M) and good intrascrotal fixation, not sus- quently is absent in patients who have torsion, but pres-

ceptible to torsion.

ence of the cremasteric reflex certainly does not exclude

This phenomenon occurs at puberty and is believed to torsion. The testicle usually is palpably tender when there

account for the age distribution of torsion, which in- is spermatic cord torsion, whereas the focal area of ten-

creases in adolescence. Rapid cremasteric muscle con- derness is in the superior testis or caput epididymis when

traction elevates the testicle and can have a rotational the patient has a torsed appendix testis or epididymitis. In

effect on the spermatic cord that can induce torsion. The the later stages of testicular torsion, scrotal edema and

congestion associated with an inflammatory process or erythema may obliterate these landmarks, making the

minor trauma also may predispose to torsion in a male examination more difficult.

who has a “bell-clapper” deformity. It is especially im- Manual detorsion may be attempted when torsion is

portant to maintain a high level of suspicion in boys who suspected and the patient’s pain tolerance allows it. Clas-

experience increasing pain after being diagnosed as hav- sically, detorsion should be attempted in a medial to

ing epididymitis or mild blunt scrotal trauma, who may lateral or “open book” rotation. If successful, the testicle

have developed testicular torsion as a secondary event. changes its orientation and usually drops lower in the

scrotum. The patient reports sudden pain relief. The

Clinical Findings direction of rotation described is only the case in about

The sudden onset of severe unilateral pain, often with two thirds of patients, and if the initial attempt at out-

nausea and vomiting, is the classic presentation of testic- ward rotation is unsuccessful, an attempt in the other

direction may be made. Analgesics are helpful when

attempting this procedure. Because manual detorsion

may not detorse the cord totally, prompt surgical explo-

ration still is required. Manual detorsion may play a role

in decreasing the degree of ischemia when a substantial

delay in reaching the operating room is anticipated, but it

is not a substitute for exploration and fixation.

Other diagnostic studies may help determine the

cause of the acutely painful scrotum. Urinalysis is indi-

cated because pyuria and bacteriuria are more likely in

infectious epididymitis/orchitis. High-resolution ultra-

sonography with color-flow Doppler and radionuclide

imaging are two studies that provide information about

testicular blood flow. Most clinicians use these studies to

help confirm a clinical diagnosis other than testicular

Figure 2. Intraoperative example of detorsed testicle that has torsion.

a narrow mesentery (M) and poor intrascrotal fixation (“bell- Radionuclide imaging of the scrotum was, at one

clapper” deformity). time, the study of choice. Ultrasonography with color

236 Pediatrics in Review Vol.29 No.7 July 2008

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

genital system acute testicular disorders

Doppler now has become a more popular study in most gonad may be responsible for later effects on the other

institutions because it allows determination of blood testis, some suggest removal of all testes that have expe-

flow, is less time-consuming, is more readily available, rienced any significant ischemic change. Our practice is

and does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation. It to remove the testis only if it appears nonviable.

also is highly reliable in experienced hands.

The ability to evaluate the testicle and spermatic cord Intermittent Testicular Torsion

anatomically is an additional advantage of ultrasonogra- A number of boys who present with torsion have a

phy. Coiling of the spermatic cord, indicating testicular history of prior acute episodes of testicular pain that

torsion, may be detected even when testicular blood flow resolve spontaneously. Unfortunately, intermittent tes-

is normal. Such studies are adjunctive to the clinical ticular pain in adolescent males is not an unusual com-

evaluation for testicular torsion and are used when that plaint. Such episodes may represent intermittent torsion

diagnosis is equivocal. If torsion is strongly suspected by with spontaneous resolution. In adolescent males who

history and physical findings, imaging only wastes time present with a history of significant acute testicular pain

when emergent surgical exploration is indicated. that has resolved (particularly with multiple events), in-

termittent testicular torsion should be strongly consid-

Surgical Correction ered. Transverse testicular orientation or excess testicular

Surgical exploration should be undertaken with as little mobility on physical examination adds to this suspicion.

delay as possible when torsion is suspected. Most sur- Doppler ultrasonography performed while the patient

geons use a midline median raphe incision, entering the has symptoms provides the diagnosis, but such a study

symptomatic hemiscrotum initially to deliver the testicle may be difficult to obtain in a timely fashion. In this

and allow detorsion. With the torsion relieved, the testi- scenario, even with normal examination findings, elective

cle is placed in warm, moist

sponges while the opposite

hemiscrotum is explored. The

contralateral testis is fixed in

three positions with nonabsorb- Surgical exploration should be undertaken

able suture. The suture should with as little delay as possible when torsion is

attach the testicle to the scrotal

wall, excluding the tunica vagi- suspected.

nalis by excising a portion or

tucking it back into the scrotum.

This technique allows better fixation of the testicle to the scrotal exploration looking for a “bell-clapper” defor-

scrotal connective tissue, much like the dartos pouch mity may be warranted. Scrotal ultrasonography prior to

fixation used in newborn scrotal fixation. elective exploration ensures that no inapparent testicular

The ipsilateral testis then is reassessed. If it is obviously lesions are present.

nonviable, it is removed. If it is reperfused or fresh

bleeding can be seen from the cut surface, it should be

replaced into the scrotum and fixed in the same fashion as Perinatal Testicular Torsion

the contralateral testis. Testicular fixation is not an abso- Perinatal torsion is a term used to include both prenatal

lute guarantee against the possibility of future torsion; and postnatal events. The difference between the two

cases of torsion after fixation have been reported. Any types of torsion is important but sometimes may be

patient presenting with suspected testicular torsion difficult to determine clinically. Prenatal torsion classi-

should be evaluated and treated with the same diligence, cally presents at birth as a hard, nontender mass in the

whether or not a previous fixation has been performed. hemiscrotum, usually with underlying dark discoloration

Antisperm antibodies can be formed in response to of the skin and fixation of the skin to the mass. This

testicular damage in the torsed gonad, raising concern picture is characteristic of infarction of the testis caused

about later damage to the contralateral testis. Although by previously occurring torsion. Postnatal torsion pre-

such damage has been demonstrated in animals, whether sents with more classic, acute inflammation, including

this antibody response is physiologically significant in erythema and tenderness. A report of a previously normal

humans remains a question. Because of speculation that scrotum at delivery suggests an acute event. The differ-

an immune response to testicular damage in the torsed ence is important because postnatal torsion requires

Pediatrics in Review Vol.29 No.7 July 2008 237

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

genital system acute testicular disorders

emergent exploration and treatment with detorsion and

fixation.

Testicular salvage in perinatal torsion generally is rare,

but some have reported surprisingly good salvage rates.

If there is any question of the timing of the torsion,

prompt exploration is the best course unless underlying

medical conditions make general anesthesia unduly risky.

Color Doppler ultrasonography may be useful in ques-

tionable cases. For patients experiencing prenatal torsion

and presumed infarction of the testes, the classic teaching

has been that surgical exploration is not indicated and

salvage rates are negligible. This doctrine, however, has

been challenged more recently, given reports of asyn-

chronous torsion and the devastating consequences of

loss of the remaining contralateral testis.

Torsion of the Contralateral Testis

Although torsion of the contralateral testis is extremely

rare, many clinicians, fueled by fear of litigation, have

become more aggressive with surgical exploration to fix

the contralateral side and prevent future torsion. This is

an area of considerable controversy. Unless medical con-

ditions make anesthesia unduly risky, it has been our

practice to explore these testes early to prevent contralat-

eral torsion and ascertain the correct diagnosis because

testicular teratoma or meconium/blood in a hernia sac

may present with the same findings.

Figure 3. “Blue dot” sign of torsed testicular appendage.

Many surgeons prefer an inguinal approach to the Testicle (T) isolated in lower scrotum and torsed appendage

involved side, which allows easier delivery and removal of (white arrow) in upper scrotum.

the necrotic, fixed gonad. The inguinal approach also is

more appropriate when an alternate diagnosis is sus-

pected. Contralateral exploration is accomplished tis, implying a bacterial origin. The testicular appendage

through a transverse scrotal incision, with placement of is a remnant of the Müllerian duct, whereas the epididy-

the testis in a dartos pouch between the external sper- mal appendages are of Wolffian duct origin. Torsion of

matic fascia of the scrotum and the dartos layer. This an appendage occurs more commonly in the prepubertal

technique is less traumatic to the small, delicate gonad age group. It is theorized that this event results from

and probably accomplishes better fixation than does hormonal stimulation, which increases the mass of the

suturing. pedunculated structures, making them susceptible to

twisting.

Mimics of Testicular Torsion The sudden onset of pain from torsion of an append-

True bacterial epididymitis/orchitis is rare in children, age can mimic testicular torsion. Findings on urinalysis

but commonly is identified inaccurately as the cause of are uniformly normal. Classically, torsion of the append-

scrotal pain in the absence of testicular torsion. Inflam- age is associated with the blue-dot sign, in which the

mation of the testis and epididymis in the adult com- infarcted appendage can be seen as a subtle blue mass

monly results from bacterial epididymitis or epididymo- through the scrotal skin (Fig. 3). Early in the condition,

orchitis that extends from the bladder and urethra in the appendage can be palpated and is exquisitely and

retrograde fashion, especially in postpubertal, sexually focally tender to palpation. As local inflammation occurs,

active males. however, the epididymis, testis, and superficial tissues

Torsion of the appendix testis or appendix epididymis become edematous, and the diagnosis becomes more

is a common cause of acute scrotal pain and frequently is difficult to make. Early ultrasonography can be diagnos-

misdiagnosed as acute epididymitis or epididymoorchi- tic, showing the discrete appendage; later, however, the

238 Pediatrics in Review Vol.29 No.7 July 2008

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

genital system acute testicular disorders

bladder ultrasonography and voiding cystourethrogra-

phy, should be obtained after the infection has resolved.

Anatomic abnormalities such as ectopic ureter to the vas,

ejaculatory duct, or seminal vesical; ejaculatory duct ob-

struction; or urethral valves are uncommon but should

be excluded.

Viral infections likely are an underappreciated cause

for acute epididymitis and usually are diagnosed pre-

sumptively. Mumps orchitis occurs in about one third of

postpubertal boys affected by the virus and, fortunately,

is rare in the modern era of immunization. Adenovirus,

enterovirus, influenza, and parainfluenza virus infections

also have been described. Management is supportive,

antibiotics are not indicated, and the pain syndrome

Figure 4. Intraoperative example of torsed appendage of generally is self-limited. Aggressive testing usually is not

testicle (white arrow) with two other nontorsed appendages warranted, but viral cultures and serologic studies may be

held in forceps. useful in clustered familial or community cases.

Voiding dysfunction is a common but underreported

study may show only increased blood flow to the adja- cause of scrotal pain that frequently is unrecognized

cent epididymis and testis and possibly a reactive hydro- unless the diagnosis is sought. Recurrent bouts of scrotal

cele, resulting in the misdiagnosis of acute epididymitis pain warrant this consideration, especially if the pain is

or epididymoorchitis. bilateral. The pathophysiology involves bladder instabil-

Torsion of the appendage is a self-limited condition ity causing high pressure in a patient who is voiding

that responds best to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory against a voluntarily closed external sphincter. It is com-

medications and comfort measures such as limited activ- mon to see dilation of the posterior urethra (“spinning-

ity and a warm compress. As the appendage infarcts and top” urethra) on voiding in affected children during

necroses, the pain resolves. Such torsion can recur be- voiding cystourethrography. Urine may be forced up the

cause five appendages potentially may experience torsion ejaculatory duct, resulting in local inflammation, and a

(appendix testis, appendix epididymis, paradidymis- “chemical” epididymitis or epididymoorchitis may re-

organ of Giraldes, superior and inferior vas aberrans of sult. Renal and bladder ultrasonography may show a

Haller). Surgical intervention is indicated when the diag- thickened bladder wall and is useful in ruling out ureteral

nosis of testicular torsion cannot be eliminated or when ectopia to the ejaculatory duct or vas deferens as a

the symptoms are prolonged and do not resolve sponta- potential cause in recurrent cases. There is no pathogno-

neously. The torsed appendage can be excised easily monic test for voiding dysfunction, but the history often

through a small scrotal incision, resulting in relief of reveals urinary urgency, incontinence, a staccato (stop-

symptoms (Fig. 4). start) urinary stream indicative of inappropriate sphincter

Classic bacterial epididymitis generally has a slow on- activity, and occult constipation. Treatment of affected

set and is characterized by scrotal pain and swelling that children via a timed voiding regimen, dietary modifica-

worsens over days rather than hours. Usually, there is no tion, aggressive management of constipation, and some-

nausea or vomiting. Bacteria are believed to reach the times anticholinergic or alpha-antagonist medication is

epididymis in retrograde fashion via the ejaculatory ducts effective.

and can be associated with a urinary tract infection or Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a vasculitic syndrome

urethritis. A positive result from urinalysis and culture, or that can affect the skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract, and

urethral swab in sexually active adolescents, suggests the genitourinary system. Pain, erythema, and swelling of the

diagnosis. Chlamydia and gonococci are described as the scrotum and spermatic cord occur in up to one third of

classic causative agents in the sexually active individual; patients. The swelling seems to occur more commonly in

common urinary pathogens, however, including coli- boys younger than 7 years of age. Scrotal findings and

forms and Mycoplasma sp, are more probable in younger onset of pain may mimic testicular torsion, but Doppler

children. When studies suggest a bacterial infection, an- ultrasonography reveals good blood flow to the testes.

tibiotics are indicated. Just as for any urinary tract infec- The history may document other systemic symptoms

tion in a boy, radiographic imaging, including renal and such as purpura of the skin, joint pain, and hematuria.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.29 No.7 July 2008 239

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

genital system acute testicular disorders

Usually supportive measures are adequate, but systemic Doppler ultrasonography is a helpful adjunct in differ-

steroids sometimes are helpful. Despite the rarity of entiating testicular torsion from other nonemergent

overlapping diagnoses, Henoch-Schönlein purpura and conditions of acute scrotal swelling (Baker 2000).

torsion of the testis have been reported together. ● Based on strong research evidence, testicular torsion is

Scrotal swelling of unknown cause is termed idio- diagnosed on the basis of history, physical examina-

pathic scrotal edema or sometimes “summer penile syn- tion, and imaging studies. When testicular torsion can-

drome.” The syndrome is characterized by thickening not be excluded, exploration is warranted (Kalfa

and erythema of the scrotum, but the testes generally are 2004).

not involved. Pruritus may be present, but the condition

is not usually painful. Ultrasonography shows normal

testicular blood flow and usually is not required. Other Suggested Reading

Baker LA, Sigman D, Mathews RI, Benson J, Docimo SG. An

causes should be sought to rule out cellulitis from an

analysis of clinical outcomes using color Doppler testicular ultra-

adjacent infection (inguinal, perirectal, or urethral). Un- sound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000;105:604 – 607

doubtedly, many cases of contact dermatitis, insect bites, Bartsch G, Frank S, Marberger H, Mikuz G. Testicular torsion: late

and minor trauma are given this diagnosis. Management results with special regard to fertility and endocrine function.

is supportive, and antihistamines or topical steroids may J Urol. 1980;124:375–378

Bukowski TP, Lewis AG, Reeves D, Wacksman J, Sheldon CA.

relieve symptoms considerably. Oral antibiotics are ad-

Epididymitis in older boys: dysfunctional voiding as an etiology.

ministered if cellulitis is a concern. J Urol. 1995;154:762–765

Other causes of the acutely painful scrotum that must Gatti JM, Murphy JP. Current management of the acute scrotum.

be considered include hernia, hydrocele, sexual abuse or Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16:58 – 63

other trauma, and neoplasia. Usually, the history, physi- Haecker FM, Hauri-Hohl A, von Schweinitz D. Acute epididymitis

in children: a 4-year retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr Surg.

cal examination, and selective imaging can differentiate

2005;15:180 –186

these causes of scrotal swelling from testicular torsion. Hutson J. Undescended testis, torsion, and varicocele. In: Grosfeld

JL, O’Neill JA, Coran AG, Fonkalsrud EW, eds. Pediatric

Conclusion Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:1193–1214

Kalfa N, Veyrac C, Baud C, Couture A, Averous M, Galifer RB.

Acute scrotal pain in the child or adolescent male always

Ultrasonography of the spermatic cord in children with testicu-

should be treated as an emergent condition. Prompt lar torsion: impact on the surgical strategy. J Urol. 2004;172:

diagnosis and surgical treatment of torsion of the sper- 1692–1695

matic cord is imperative to avoid permanent ischemic Karmazyn B, Steinberg R, Livne P, et al. Duplex sonographic

damage to the testicle. Fortunately, most of the condi- findings in children with torsion of the testicular appendages:

overlap with epididymitis and epididymoorchitis. J Pediatr Surg.

tions causing this syndrome are nonurgent. An accurate

2006;41:500 –504

diagnosis can be made with the history, physical exami- Nagler HM, White RD. The effect of testicular torsion on the

nation, and imaging. contralateral testis. J Urol. 1982;128:1343–1348

Sessions AE, Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC, Goldstein MM, Mevo-

rach RA. Testicular torsion: direction, degree, duration and

Summary disinformation. J Urol. 2003;169:663– 665

● Based on strong research evidence, prompt operative Somekh E, Gorenstein A, Serour F. Acute epididymitis in boys:

evidence of a post-infectious etiology. J Urol. 2004;171:391–394

intervention for torsion of the testicle is imperative for Sorensen MD, Galansky SH, Striegl AM, Mevorach R, Koyle MA.

testicular survival (Bartsch 1980). Perinatal extravaginal torsion of the testis in the first month of

● Based on strong research evidence, scrotal color life is a salvageable event. Urology. 2003;62:132–134

240 Pediatrics in Review Vol.29 No.7 July 2008

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

genital system acute testicular disorders

PIR Quiz

Quiz also available online at www.pedsinreview.org.

9. During a health supervision visit, a 13-year-old boy who is new to your practice relates that over the past

2 years he has had three bouts of severe unilateral scrotal pain that have resolved over several minutes.

Your examination reveals genitalia and pubic hair at Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR) 4. No clear

abnormalities are identified on palpation. Your chief concern should be the possibility of:

A. Intermittent testicular torsion.

B. Intermittent torsion of the appendix testis.

C. Recurrent epididymitis.

D. Recurrent orchitis.

E. Recurrent thrombosis of a varicocele.

10. Physical examination of the affected hemiscrotum early in the course of acute testicular torsion is most

likely to reveal:

A. A low-riding testicle.

B. A small blue mass in the superior testis.

C. Anterior location of the epididymis.

D. Focal tenderness in the superior portion of the testis.

E. Purpura of the scrotal skin.

11. Ten hours ago, a previously healthy 14-year-old boy developed sudden excruciating pain in his right

hemiscrotum. He recalls no injury or antecedent illness. He is sexually active. On physical examination, the

right hemiscrotum is red, swollen, and exquisitely tender. The most appropriate first step is to:

A. Attempt manual detorsion.

B. Order color Doppler ultrasonography.

C. Order urinalysis.

D. Order radionuclide imaging.

E. Proceed immediately to the operating room.

12. A previously healthy 8-year-old boy presents to the emergency department 1 hour after developing the

acute onset of right-sided scrotal pain. Aside from obvious discomfort, findings of his general examination

are normal. Genitalia are at SMR 1. Examination of the contents of the right hemiscrotum is made

difficult by edema and tenderness. Urinalysis results are normal. Color Doppler ultrasonography reveals

increased blood flow to the right epididymis and testis. These data best support a diagnosis of:

A. Acute epididymitis.

B. Acute testicular torsion.

C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

D. Summer penile syndrome.

E. Torsion of the appendix testis.

13. A previously healthy 14-year-old boy has been experiencing left scrotal pain for the past 3 days. He

recalls no injury or antecedent illness. He is sexually active. His general examination findings are normal,

but his left hemiscrotum is warm, swollen, and slightly tender to palpation. Both testes are palpable at the

same level. A urinalysis reveals 40 white blood cells per high-power field with a negative nitrite test. The

most appropriate next step is to:

A. Apply cold compresses.

B. Attempt manual detorsion.

C. Begin oral antibiotics.

D. Order color Doppler ultrasonography.

E. Proceed immediately to the operating room.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.29 No.7 July 2008 241

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

Acute Testicular Disorders

John M. Gatti and J. Patrick Murphy

Pediatr. Rev. 2008;29;235-241

DOI: 10.1542/pir.29-7-235

Updated Information including high-resolution figures, can be found at:

& Services http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/29/7/235

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Genital System Disorders

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/genital_sy

stem_disorders Renal Disorders

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/renal_diso

rders

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/misc/Permissions.shtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/misc/reprints.shtml

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org. Provided by Health Internetwork on September 26, 2009

You might also like

- CBLDocument13 pagesCBLdanush pathirana50% (4)

- Testicular Torsion: Dr. Hari Krismanuel, Sp. B, FinacsDocument19 pagesTesticular Torsion: Dr. Hari Krismanuel, Sp. B, FinacsVanessa Modi AlverinaNo ratings yet

- Geothermal Energy Poster 2Document1 pageGeothermal Energy Poster 2api-298575301100% (2)

- ITP PLUMBING WORKS SampleDocument1 pageITP PLUMBING WORKS SampleJay Chris L. Beron67% (3)

- Calculation of Septic Tank & Sock PitDocument11 pagesCalculation of Septic Tank & Sock Pitakram1978No ratings yet

- 2017 Pediatric Testicular TorsionDocument12 pages2017 Pediatric Testicular TorsionVladimir BasurtoNo ratings yet

- Acute Scrotum PDFDocument9 pagesAcute Scrotum PDFthejaskamathNo ratings yet

- Lopez 2011Document3 pagesLopez 2011nadira wardaNo ratings yet

- M 1: T A S: Odule HE Cute CrotumDocument10 pagesM 1: T A S: Odule HE Cute CrotumROMANNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Acute Scrotum PDFDocument11 pagesModule 1 Acute Scrotum PDFbayutrihatmajaNo ratings yet

- Torsio TestisDocument55 pagesTorsio TestisAulia RizkiaNo ratings yet

- Acutescrotalemergencies: Molly M. Bourke,, Joshua Z. SilverbergDocument18 pagesAcutescrotalemergencies: Molly M. Bourke,, Joshua Z. SilverbergSebastian ChavesNo ratings yet

- Bowl in 2017Document12 pagesBowl in 2017kafosidNo ratings yet

- Campbell - Walsh-Wein UROLOGY 12th Ed ADocument6 pagesCampbell - Walsh-Wein UROLOGY 12th Ed Awijana410No ratings yet

- Acute ScrotumDocument9 pagesAcute ScrotumIsabel ReyNo ratings yet

- The Acute ScrotumDocument9 pagesThe Acute ScrotumAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Acute Scrotum PDFDocument9 pagesAcute Scrotum PDFJody FelizioNo ratings yet

- 8412-Article Text-29472-1-10-20130809Document8 pages8412-Article Text-29472-1-10-20130809NenyNo ratings yet

- Testicular Torsion: A Urological EmergencyDocument4 pagesTesticular Torsion: A Urological EmergencycorsaruNo ratings yet

- Undescended Testes: What General Practitioners Need To KnowDocument4 pagesUndescended Testes: What General Practitioners Need To KnowRizka Desti AyuniNo ratings yet

- Referat Torsio TestisDocument22 pagesReferat Torsio TestisStefanieAngeline100% (1)

- Testicular Torsion - ClinicalKeyDocument10 pagesTesticular Torsion - ClinicalKeyWialda Dwi rodyahNo ratings yet

- Testis and ScrotumDocument7 pagesTestis and Scrotumyoussef.aziz2020No ratings yet

- 1843 1pqu7ccDocument8 pages1843 1pqu7ccOttofianus Hewick KalangiNo ratings yet

- Mehu108 - U8 - T8 - Afecciones Del Escroto y Contenido3Document18 pagesMehu108 - U8 - T8 - Afecciones Del Escroto y Contenido3Elaine Alondra Ortiz OrtizNo ratings yet

- Testicular AppendagesDocument4 pagesTesticular AppendagesJohn stamosNo ratings yet

- Testicular Torsion: The Right Clinical Information, Right Where It's NeededDocument34 pagesTesticular Torsion: The Right Clinical Information, Right Where It's NeededHarshpreet KaurNo ratings yet

- Parurethral CystsDocument3 pagesParurethral CystsIoannis ValioulisNo ratings yet

- A Giant Osteochondroma On Pubic Ramus (Case Report) JAMBIDocument7 pagesA Giant Osteochondroma On Pubic Ramus (Case Report) JAMBINugroho Tri WibowoNo ratings yet

- Urological Science: Jiun-Hung Geng, Chun-Nung HuangDocument4 pagesUrological Science: Jiun-Hung Geng, Chun-Nung Huangyerich septaNo ratings yet

- University Journal of Surgery and Surgical Specialities: Dhivya Lakshmi S JDocument4 pagesUniversity Journal of Surgery and Surgical Specialities: Dhivya Lakshmi S JYonathanWaisendiNo ratings yet

- 14 Vol. 11 Issue 11 Nov 2020 IJPSR RE 3646Document7 pages14 Vol. 11 Issue 11 Nov 2020 IJPSR RE 3646Ehwanul HandikaNo ratings yet

- Fracture of The Penis - A ReviewDocument6 pagesFracture of The Penis - A ReviewNatalindah Jokiem Woecandra T. D.No ratings yet

- Testicular Torsion - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument6 pagesTesticular Torsion - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfwijana410No ratings yet

- Paraurethral Cyst: A Case Report: Central European Journal ofDocument3 pagesParaurethral Cyst: A Case Report: Central European Journal ofEltohn JohnNo ratings yet

- Mini Review: Current Concepts in The Management of Anterior Urethral StricturesDocument8 pagesMini Review: Current Concepts in The Management of Anterior Urethral StricturesDwi WiraNo ratings yet

- Reproductive Path oDocument7 pagesReproductive Path oMae ANo ratings yet

- 1.4 Management of Constriction Ring of The Uterus Using Isoxuprine M. Barker and J.V. Laursen - 2Document5 pages1.4 Management of Constriction Ring of The Uterus Using Isoxuprine M. Barker and J.V. Laursen - 2Sunil ShastryNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Agenesis or HypoplasiaDocument18 pagesVaginal Agenesis or Hypoplasianikd_6No ratings yet

- Essential Skills of Scrotal Examination: A Step-By-Step TechniqueDocument5 pagesEssential Skills of Scrotal Examination: A Step-By-Step TechniqueDielika CharlierNo ratings yet

- Parameatal Cyst :A Case ReportDocument3 pagesParameatal Cyst :A Case ReportDr.ankit AnandNo ratings yet

- Goh 2004Document3 pagesGoh 2004Brendan DiasNo ratings yet

- Various Sonographic Appearances of The Hemorrhagic Corpus Luteum CystDocument14 pagesVarious Sonographic Appearances of The Hemorrhagic Corpus Luteum CystBerry BancinNo ratings yet

- Luh Putu Dian SuryaningsihDocument3 pagesLuh Putu Dian SuryaningsihAngga PutraNo ratings yet

- Hysteroscopic Management of Omentum Incarceration (Ingles)Document6 pagesHysteroscopic Management of Omentum Incarceration (Ingles)silviadmcastellanNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Endometriosis in Turners SyndromeDocument3 pagesA Rare Case of Endometriosis in Turners SyndromeElison J PanggaloNo ratings yet

- Scrotal Conditions: Done By: Enas Almazraway Sarah Al-HawamdehDocument65 pagesScrotal Conditions: Done By: Enas Almazraway Sarah Al-HawamdehMohammad GharaibehNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument3 pagesCase ReportArman MukhtarNo ratings yet

- Extrusio N de Pro Tesis Testicular: Presentacio N de Un Caso y Revisio N de La Literatura Me DicaDocument3 pagesExtrusio N de Pro Tesis Testicular: Presentacio N de Un Caso y Revisio N de La Literatura Me DicaJorge IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous Rupture of An Unscarred GravidDocument4 pagesSpontaneous Rupture of An Unscarred GraviddelaNo ratings yet

- Imperforate Anus and Cloacal MalformationsDocument110 pagesImperforate Anus and Cloacal MalformationsAhmad Abu KushNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery Case ReportsDocument3 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery Case ReportsDr David NekouNo ratings yet

- Anal AtresiaDocument13 pagesAnal AtresiaAhmad Ihsan100% (1)

- Vesico Vaginal FistulaDocument6 pagesVesico Vaginal Fistulaapi-3705046No ratings yet

- Case Presentation Testicular TorsonDocument16 pagesCase Presentation Testicular TorsonMestikarini AstariNo ratings yet

- Intrauterine Device (IUD) in Bladder Stone: B Shetty, M VDocument3 pagesIntrauterine Device (IUD) in Bladder Stone: B Shetty, M VMangkubumi PutraNo ratings yet

- Testicular Torsion, Hydrocele & Fournier GangreneDocument41 pagesTesticular Torsion, Hydrocele & Fournier GangreneNur Insyirah100% (1)

- Penis Fracture - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument5 pagesPenis Fracture - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Cystic Ovary Research 1Document3 pagesCystic Ovary Research 1adarshthakur41973No ratings yet

- Ovarian CystDocument3 pagesOvarian Cystaira11No ratings yet

- Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy A Case ReportDocument4 pagesInterstitial Ectopic Pregnancy A Case ReportRina Auliya WahdahNo ratings yet

- KistokelDocument4 pagesKistokelIntan PermataNo ratings yet

- HP y CancerDocument14 pagesHP y CancerHernan Del CarpioNo ratings yet

- Gastro Colopatia HTPDocument18 pagesGastro Colopatia HTPHernan Del CarpioNo ratings yet

- Fisiopato HTPDocument11 pagesFisiopato HTPHernan Del CarpioNo ratings yet

- Overlap Syndrome: A Real Syndrome?: Underlying ConceptsDocument5 pagesOverlap Syndrome: A Real Syndrome?: Underlying ConceptsHernan Del CarpioNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Hepatitis: Diagnostic Criteria and Serological TestingDocument4 pagesAutoimmune Hepatitis: Diagnostic Criteria and Serological TestingHernan Del CarpioNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Hepatitis: HistopathologyDocument5 pagesAutoimmune Hepatitis: HistopathologyHernan Del CarpioNo ratings yet

- Gobi ManchurianDocument3 pagesGobi ManchurianPriya JuligantiNo ratings yet

- Elnova Pharma: India's Leading Softgel Capsules ManufacturerDocument29 pagesElnova Pharma: India's Leading Softgel Capsules ManufacturerAnkur GulatiNo ratings yet

- Vashikaran Mantra For Love PDFDocument4 pagesVashikaran Mantra For Love PDFmustafaaldin0% (2)

- Q Bank Chem MCD Viii 2019Document19 pagesQ Bank Chem MCD Viii 2019hgbv tttbNo ratings yet

- Lecture, Activity, OutlineDocument12 pagesLecture, Activity, OutlineJhnJn EvnglstNo ratings yet

- UKA Athletics Coach Induction Pack v2 Jan 2013Document36 pagesUKA Athletics Coach Induction Pack v2 Jan 2013gpitbullNo ratings yet

- FDA Dairy Product Recall Rizo-Lopez Foods IncDocument9 pagesFDA Dairy Product Recall Rizo-Lopez Foods IncWXMINo ratings yet

- Capgemini Excelity Payroll FAQDocument16 pagesCapgemini Excelity Payroll FAQAbhijitNo ratings yet

- Bombas SumergiblesDocument79 pagesBombas SumergiblesInstinct_brNo ratings yet

- Significant Risk RegisterDocument8 pagesSignificant Risk RegisterswestyNo ratings yet

- Flowers For Algernon ThesisDocument6 pagesFlowers For Algernon Thesiss0kuzej0byn2100% (2)

- 1.2 Safety & Rules in Biology LaboratoryDocument32 pages1.2 Safety & Rules in Biology LaboratoryasyuraNo ratings yet

- Carbon and Its Compounds Revision SheetDocument2 pagesCarbon and Its Compounds Revision Sheetyashvibhatia5No ratings yet

- Adam S. Tricomo: Concordia University Irvine, Irvine, CADocument2 pagesAdam S. Tricomo: Concordia University Irvine, Irvine, CAapi-518371548No ratings yet

- Ke-45-Ts Sds JPN EngDocument9 pagesKe-45-Ts Sds JPN Engsouradeepmukherjee20No ratings yet

- Vaginal Discharge in DogsDocument5 pagesVaginal Discharge in DogsDarmawan Prastyo100% (1)

- Dermatology: Professional Certificate inDocument4 pagesDermatology: Professional Certificate inmadimadi11No ratings yet

- Recruitment MSCDocument40 pagesRecruitment MSCViji MNo ratings yet

- 11th Zoology Volume 1 New School Books Download English MediumDocument240 pages11th Zoology Volume 1 New School Books Download English Mediumaishikanta beheraNo ratings yet

- Wallmat Supply Chain Analysis PDFDocument44 pagesWallmat Supply Chain Analysis PDFProsenjit RoyNo ratings yet

- Unit 5. PHCDocument24 pagesUnit 5. PHCFenembar MekonnenNo ratings yet

- Alexandra Marchuk V Faruqi and Faruqi AnswerDocument52 pagesAlexandra Marchuk V Faruqi and Faruqi Answerdavid_latNo ratings yet

- Heridity: Table of SpecificationsDocument8 pagesHeridity: Table of SpecificationsJoseph GratilNo ratings yet

- UN SMA 2008 Bahasa Inggris: Kode Soal P44Document7 pagesUN SMA 2008 Bahasa Inggris: Kode Soal P44hestyNo ratings yet

- Offtake Oc035 Preparation Go No Go ChecklistDocument8 pagesOfftake Oc035 Preparation Go No Go ChecklistIhwan AsrulNo ratings yet