Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Protecting High Quality Habitat From Green Energy

Protecting High Quality Habitat From Green Energy

Uploaded by

api-545814513Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Protecting High Quality Habitat From Green Energy

Protecting High Quality Habitat From Green Energy

Uploaded by

api-545814513Copyright:

Available Formats

Keeping Green From Being Mean

By: Bailey Johnson

The need for speed

How would you feel if your home and everything you need to survive was destroyed and

taken by over-sized invaders and you had no means to stop them? This is a possibility for five

rare and listed species with ranges that overlap with many other sensitive species. In order to

meet 2015 Senate Bill (SB 350), growth of solar farming as an industry will undoubtedly

increase. Large-scale solar energy facilities will need to be built while also safeguarding high to

moderate-quality habitat for rare and listed species in the San Joaquin Valley (SJV). SB 350 was

put into action to increase economic reliability on sources of green, renewable energy. By 2026,

fifty-percent of energy must come from renewable sources, which is in just six short years. We

will need to take into account the habitat suitability for rare and endangered species with the

rapid development of solar facilities soon to take place. There are currently about 8,000 km2 of

low-quality habitat that have high potential for solar development. Insolation, which is defined

as having heightened exposure to the sun's rays would be the most energetically efficient and it

would also be much easier and more accessible to build these solar farms on flat land. In comes

the SJV, where the demand can be met in ways that help to prevent the extinction of endangered

species by building on low-quality, rare species habitat and providing a corridor in which these

species can travel through. There is going to be an accelerated response to develop large scale

solar farms which are insolation efficient and can meet the demands of SB 350.

Figure 1. Ivanpah solar energy facility. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/103707855@N05/16487460430

Why is the San Joaquin Valley so high in demand for green

development?

The San Joaquin Valley extends

400 miles from Northern California down to

Southern California and it is near 75 miles

wide. SJV is low in elevation and is

surrounded by mountain ranges and coastal

communities. Historically, the valley was

flooded with ocean water, allowing

sediments to deposit and fertilize the

mineral-rich soils, making this land very

attractive for irrigated agriculture and

human development. What was once

historical prairie habitat; home to endemic,

rare, federally, and state-listed species have

been displaced by the fact that 70% of what

was once their historic range has been

converted into agriculture and human use. If

you have never been to the SJV it is often

characterized by being flat, and arid which

are two conditions perfect for constructing

large-scale solar farms. Urban areas in the

region continue to grow along with our

statewide demand to meet the need for more

Figure 2. Historical San Joaquin Valley. Source: http://www.tws- renewable energy resources.

west.org/westernwildlife/vol6/Phillips_Cypher_WW_2019.pdf, page 33.

The method to the madness

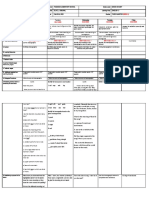

Authors Phillips and Cypher developed a GIS-based modeling (geographic information

system) approach to find areas that had a high probability of solar and urban along with places

that contained high to moderate quality habitat for listed and rare species. Next, they looked at

areas that were not only attractive for solar farming but also had poor-quality habitat for listed

species. By developing on lands with poor quality habitat it would not only ease any harmful

effects for rare species but also create wildlife bridges between the areas of high quality and

developed habitat. Green energy sources are a good alternative for fighting against climate

change because it offers a solution for not using fossil fuels. Fossil fuels can induce climate

change by burning ancient plant biomass, which then release carbon dioxide, CO2, into our

atmosphere which then gets trapped by our ozone. If we're not careful about where we build

these utility-scale facilities then it could have a serious impact on sensitive species. There were

5 species chosen to be modeled after; blunt-nosed leopard lizard, San Joaquin kit fox, San

Joaquin Antelope squirrel, Giant kangaroo rat, and the San Joaquin kangaroo rat. These species

have ranges and habitat requirements that coincided with other rare species so findings were not

just to the five species in question but rather a wider proportion of the species of concern in the

SJV.

The grass really is greener on the other side

The good news is that there’s an area found by this modeling approach to be suitable for

these proposed solar farm facilities is just west of Fresno County in the Westland's Water

District. Due to high salinity in soils and already degraded habitat, it might actually benefit the

habitat by providing wildlife corridors for listed species. In previous studies, at the Topaz Solar

Farm location in NE San Luis Obispo County, there were documented sightings of San Joaquin

kit fox populations persisting through construction and after construction was completed actively

reproducing populations were observed. Green energy doesn't have to be mean as long as we're

making sure that we're building on poor quality habitat that would not support populations

anyway. Perhaps, by building on poor quality habitat zones we can also provide green bridges so

that listed species may travel around or through these facilities from one high-quality habitat to

the next.

Figure 3. Wildflower bloom (high-quality habitat) in the Central valley.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/marc_cooper/25546095485

References

Phillips, Scott E, and Brian L Cypher. “Solar Energy Development and Endangered Species in

the San Joaquin Valley, California: Identification of Conflict Zone.” Solar Energy

Development and Endangered Species in the San Joaquin Valley, California: Identification

of Conflict Zone, vol. 6, 4 Aug. 2019, pp. 29–44., www.tws-

west.org/westernwildlife/vol6/WW_Volume6.pdf#page=32.

You might also like

- DLL ENGLISH 3 WEEK 2 Q3 HomographsDocument7 pagesDLL ENGLISH 3 WEEK 2 Q3 HomographsOlive L. Gabunal100% (2)

- Grade 5 SLM Q2 Module 6 Interactions Among Living Things and Non Living EditedDocument21 pagesGrade 5 SLM Q2 Module 6 Interactions Among Living Things and Non Living EditedRenabelle Caga100% (2)

- 4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXDocument24 pages4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXdavidNo ratings yet

- Fragmenting The Western American LandscapeDocument10 pagesFragmenting The Western American LandscapeJULISSA RESENDIZNo ratings yet

- Audubon Canyon Ranch Bulletin, Spring 2009Document12 pagesAudubon Canyon Ranch Bulletin, Spring 2009LiaPrqoiouNo ratings yet

- Water History, Art, and Culture Water History, Art, and CultureDocument51 pagesWater History, Art, and Culture Water History, Art, and CultureDrn PskNo ratings yet

- El Paisano Summer 2008 #201Document8 pagesEl Paisano Summer 2008 #201chris-clarke-5915No ratings yet

- 24a44 Environment Part 1 Compressed - 1320066 103 115 PDFDocument13 pages24a44 Environment Part 1 Compressed - 1320066 103 115 PDFAbhay kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- VEAC CW Summary 8pp A3fold WEB SmallDocument5 pagesVEAC CW Summary 8pp A3fold WEB Smalljolyon AttwoollNo ratings yet

- Eco Notes - HabitatDestructionDocument4 pagesEco Notes - HabitatDestructionTapasya VoraNo ratings yet

- Ecesis: Considerations For Designing Riparian Restoration For Wildlife in California's Central ValleyDocument12 pagesEcesis: Considerations For Designing Riparian Restoration For Wildlife in California's Central ValleyEfiArqgyridoyNo ratings yet

- The Natural and Social History of The Indigenous Lands and Protected Areas Corridor of The Xingu River BasinDocument13 pagesThe Natural and Social History of The Indigenous Lands and Protected Areas Corridor of The Xingu River BasinMariusz KairskiNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument4 pages1 PBNELZON CARDENAS CHAICONo ratings yet

- Waterfowl Management Handbook: Beaver Ponds As Breeding Habitats For WaterfowlDocument7 pagesWaterfowl Management Handbook: Beaver Ponds As Breeding Habitats For WaterfowlfouineuNo ratings yet

- Landscapes Newsletter, Winter 2003 Peninsula Open Space TrustDocument15 pagesLandscapes Newsletter, Winter 2003 Peninsula Open Space TrustZafiriouErifilhNo ratings yet

- Habitat Restoration in The Arroyo SecoDocument47 pagesHabitat Restoration in The Arroyo Secothor888888No ratings yet

- Riverside Documents "Hit The Street": Phainopepla Has Odd Nesting HabitsDocument4 pagesRiverside Documents "Hit The Street": Phainopepla Has Odd Nesting HabitsEndangered Habitats LeagueNo ratings yet

- Deserts DraggedDocument5 pagesDeserts DraggedArnold VasheNo ratings yet

- Hallie Morrison Portfolio 2017Document25 pagesHallie Morrison Portfolio 2017Hallie MorrisonNo ratings yet

- Meadows in The Sierra Nevada of California: State of KnowledgeDocument59 pagesMeadows in The Sierra Nevada of California: State of KnowledgePACIFIC SOUTHWEST RESEARCH STATION REPORTNo ratings yet

- Geoarchaeology - 2022 - Kirch - Soils Agriculture and Land Use in Island Socio Ecosystems Three Case Studies FromDocument15 pagesGeoarchaeology - 2022 - Kirch - Soils Agriculture and Land Use in Island Socio Ecosystems Three Case Studies FromKaterina BlackNo ratings yet

- Red Swamp CrayfishDocument21 pagesRed Swamp CrayfishmalamskiNo ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument1 pageExecutive SummaryTeja MaheshNo ratings yet

- Open Mind Nonnative SpeciesDocument2 pagesOpen Mind Nonnative SpeciesEmilio EsquivelNo ratings yet

- Last Child in The Woods: AcornDocument12 pagesLast Child in The Woods: AcornSalt Spring Island ConservancyNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 90.120.46.220 On Wed, 29 Sep 2021 14:01:37 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 90.120.46.220 On Wed, 29 Sep 2021 14:01:37 UTCKjellaNo ratings yet

- Coastal Wetlands ReadingDocument4 pagesCoastal Wetlands ReadingHân LêNo ratings yet

- Beaver-Human Conflict and Habitat Suitability AnalysisDocument2 pagesBeaver-Human Conflict and Habitat Suitability AnalysisTeja MaheshNo ratings yet

- Effects of Climate Change:: (I) AfricaDocument25 pagesEffects of Climate Change:: (I) AfricaUrsu AlexNo ratings yet

- Jan 2001 San Diego SierraDocument17 pagesJan 2001 San Diego SierraU8x58No ratings yet

- LPRYouth FINALDocument3 pagesLPRYouth FINALversloeildhorusNo ratings yet

- 05 Designing Livelihoods Sustainable Livelihood Options in Little Rann of KutchDocument13 pages05 Designing Livelihoods Sustainable Livelihood Options in Little Rann of KutchRiddhi ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Carrying CapacityDocument2 pagesCarrying CapacityPangiDoank100% (2)

- 2023 - T2 - U2 - 7HASS - WORK RETURN - Water in The WorldDocument3 pages2023 - T2 - U2 - 7HASS - WORK RETURN - Water in The Worldsamm musiccaNo ratings yet

- The Roadrunner: Residents Oppose Solar Project in Kelso ValleyDocument10 pagesThe Roadrunner: Residents Oppose Solar Project in Kelso ValleyKern Kaweah Sierrra ClubNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 (11.07Document10 pagesLecture 1 (11.07api-3801916No ratings yet

- Management of Forests: Biology Presentation Class 10GDocument26 pagesManagement of Forests: Biology Presentation Class 10Ghrishikesh khadeNo ratings yet

- Making The Link PhilippinesDocument11 pagesMaking The Link PhilippinesmzerrahNo ratings yet

- FokkensDocument98 pagesFokkenshasan aliNo ratings yet

- Period 1 KCODocument12 pagesPeriod 1 KCOWilliam HaywoodNo ratings yet

- Postglacial Foraging in The Forests of EuropeDocument13 pagesPostglacial Foraging in The Forests of EuropeShreyashi KashyapNo ratings yet

- Deforestation by Aditya DharapureDocument10 pagesDeforestation by Aditya DharapureJethalal GadaNo ratings yet

- IJHSS - Human Environment - Special Reference With Settlement, Transport and Communication - 1Document6 pagesIJHSS - Human Environment - Special Reference With Settlement, Transport and Communication - 1iaset123No ratings yet

- The Decline of The Beluga Sturgeon: A Case Study About Fisheries ManagementDocument11 pagesThe Decline of The Beluga Sturgeon: A Case Study About Fisheries ManagementBlade Of DespairNo ratings yet

- Crawfish Culture A Louisiana Aquaculture Success StoryDocument6 pagesCrawfish Culture A Louisiana Aquaculture Success StoryNito EspadilhaNo ratings yet

- Their Communities and Includes A Number of References About Recognizing Indigenous Peoples As ADocument25 pagesTheir Communities and Includes A Number of References About Recognizing Indigenous Peoples As AUrsu AlexNo ratings yet

- Places To Remember Before They Disappear: WorldDocument17 pagesPlaces To Remember Before They Disappear: WorldiomimaNo ratings yet

- Just Add Water: Richard G. Roberts Is Intrigued by The Idea That EarlyDocument2 pagesJust Add Water: Richard G. Roberts Is Intrigued by The Idea That EarlyLaura VelásquezNo ratings yet

- P Jdisturbanceregimes Shortsynthesis 5 07Document16 pagesP Jdisturbanceregimes Shortsynthesis 5 07Annisa Pe WeNo ratings yet

- Article - Cereal Killer Was Agriculture The Greatest Blunder in Human HistoryDocument3 pagesArticle - Cereal Killer Was Agriculture The Greatest Blunder in Human HistorySamantha Beatriz B ChuaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Desert Exploitation and Abuse: A Formal United Nations ReportDocument9 pagesThe Effects of Desert Exploitation and Abuse: A Formal United Nations Reportapi-276104352No ratings yet

- Bolivien 12 Ruthsatz WM PDFDocument49 pagesBolivien 12 Ruthsatz WM PDFFernanda Cordova HernandezNo ratings yet

- SST Activity 4.0Document17 pagesSST Activity 4.0Prisha BatraNo ratings yet

- Hydrological CycleDocument9 pagesHydrological CycleGodwillProsperSizibaNo ratings yet

- Esrm 479 - Final BookletDocument113 pagesEsrm 479 - Final Bookletmel7torres-3No ratings yet

- Bio Book 1st Ed-CompressedDocument76 pagesBio Book 1st Ed-Compressedapi-548699613No ratings yet

- W2 Exposure & VulnerabilityDocument2 pagesW2 Exposure & VulnerabilityGwen Stefani DaugdaugNo ratings yet

- Kautz Et Al 2006 BiolConsDocument16 pagesKautz Et Al 2006 BiolConsOlga SeregNo ratings yet

- History MergedDocument58 pagesHistory MergedRohith ReddyNo ratings yet

- Natural ResourceDocument30 pagesNatural ResourcejdidiwoodkdorNo ratings yet

- Pak Studies O Levels CAIE Past Paper NotesDocument58 pagesPak Studies O Levels CAIE Past Paper Notesbilal ayub100% (1)

- Billionaire Song ExerciseDocument1 pageBillionaire Song ExerciseLisa DXNo ratings yet

- Tle 6 Lesson 3Document8 pagesTle 6 Lesson 3Mayaman UsmanNo ratings yet

- Maths Specimen Paper 1 2014 2017Document16 pagesMaths Specimen Paper 1 2014 2017Ly Shan100% (1)

- Mathematics Grade 10Document270 pagesMathematics Grade 10TammanurRaviNo ratings yet

- SHRM PerspectivesDocument14 pagesSHRM PerspectivesNoman Ul Haq Siddiqui100% (2)

- Unitized Billet and BarDocument3 pagesUnitized Billet and BarRamesh Krishnan BalasubramanianNo ratings yet

- Spill Kit ChecklistDocument1 pageSpill Kit Checklistmd rafiqueNo ratings yet

- Final Examination (Open Book) Koc3466 (Corporate Writing)Document9 pagesFinal Examination (Open Book) Koc3466 (Corporate Writing)Shar KhanNo ratings yet

- HDHR-242U: High Density PolyethyleneDocument1 pageHDHR-242U: High Density Polyethylenefrancisca ulloa riveraNo ratings yet

- Doctor Kekalo Pinto Bean Whole Supplier: 1. Executive SummaryDocument12 pagesDoctor Kekalo Pinto Bean Whole Supplier: 1. Executive Summaryalemayehu tarikuNo ratings yet

- Psycosocial Activities Day 3Document40 pagesPsycosocial Activities Day 3John Briane CapiliNo ratings yet

- SeleniumDocument8 pagesSeleniumSai ReddyNo ratings yet

- Manual Motores DieselDocument112 pagesManual Motores Dieselaldo pelaldoNo ratings yet

- Jak Na Power Bi Cheat SheetDocument3 pagesJak Na Power Bi Cheat SheetenggdkteNo ratings yet

- Phi Theta Kappa Sued by HonorSociety - Org Lawsuit Details 2024 False AdvertisingDocument47 pagesPhi Theta Kappa Sued by HonorSociety - Org Lawsuit Details 2024 False AdvertisinghonorsocietyorgNo ratings yet

- 2016 Hyundai Grand I10 Magna 1.2 VTVT: Great DealDocument4 pages2016 Hyundai Grand I10 Magna 1.2 VTVT: Great DealBoby VillariNo ratings yet

- Giant Water Heater Parts - DT016-172-BPS-EPS-EnDocument2 pagesGiant Water Heater Parts - DT016-172-BPS-EPS-EnFrancois TheriaultNo ratings yet

- Composition 1 S2 2020 FinalDocument46 pagesComposition 1 S2 2020 Finalelhoussaine.nahime00No ratings yet

- Lab 16 - Law of Definite CompositionDocument6 pagesLab 16 - Law of Definite CompositionMicah YapNo ratings yet

- Sheila Mae Seville CVDocument1 pageSheila Mae Seville CVc21h25cin203.2hc1No ratings yet

- (20-58) Charging Case Firmware Update Guide For R180 - Rev1.1Document6 pages(20-58) Charging Case Firmware Update Guide For R180 - Rev1.1Brandon CifuentesNo ratings yet

- 99tata Motors Ltd. Letter of Offer 18.09.08Document403 pages99tata Motors Ltd. Letter of Offer 18.09.08Sharmilanoor Nurul BasharNo ratings yet

- How To Analyse Non-Fictional Texts-1Document5 pagesHow To Analyse Non-Fictional Texts-1chaymaelmeknassi2No ratings yet

- PDFDocument233 pagesPDFtuNo ratings yet

- Tracebility MatrixDocument4 pagesTracebility Matrixmkm969No ratings yet

- Bhaktisiddhanta Appearance DayDocument5 pagesBhaktisiddhanta Appearance DaySanjeev NambalateNo ratings yet

- Genesis g16Document2 pagesGenesis g16Krist UtamaNo ratings yet

- R Trader Trader's GuideDocument93 pagesR Trader Trader's Guidelearn2shareNo ratings yet