Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IndianJPsychiatry63135-46714 125834

IndianJPsychiatry63135-46714 125834

Uploaded by

gion.nandOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IndianJPsychiatry63135-46714 125834

IndianJPsychiatry63135-46714 125834

Uploaded by

gion.nandCopyright:

Available Formats

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org on Saturday, April 10, 2021, IP: 117.217.158.

253]

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Addiction‑like behavior associated with social media usage in undergraduate

students of a government medical college in Delhi, India

Saurav Basu, Ragini Sharma, Pragya Sharma, Nandini Sharma

Department of Community Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India

ABSTRACT

Background: Excessive use of social media is increasingly being recognized as a source of technological addiction in

young people globally.

Objective: The aim of this study is to assess social media addiction in medical students using a self‑designed questionnaire.

Materials and Methods: We collected data from undergraduate medical students (MBBS) in Delhi, India using a

self‑administered 20‑item social media addiction questionnaire (SMAQ) to measure addiction‑like behavior, and the

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to assess sleep quality.

Results: We enrolled 264 (62.3%) male and 160 (37.7%) female participants of mean (standard deviation) age 19.83 (1.6)

years. The Cronbach’s alpha of the SMAQ was 0.879. A principal component analysis revealed a 4‑component SMAQ

structure based on eigenvalue cutoff (>1), loading score >0.3, and inspection of the Scree‑plot that explained 54.7% of

the total variance. We observed strong loadings of impaired control items on Component 1, decreased alternate pleasure

items on Component 2, intense desire items on Component 3, and harmful use items on Component 4. The mean SMAQ

score was significantly higher in the students reporting poor sleep quality and older students.

Conclusion: The SMAQ has acceptable psychometric properties, with higher scores associated with sleep deprivation.

A majority of students were unable to reduce their time spent on social media despite wanting to do so, signifying the

presence of tolerance and impaired control.

Key words: India, sleep deprivation, social media addiction, validation

INTRODUCTION exponentially increased in the previous decade due to

the dissemination of affordable Internet and smartphone

Social media constitutes a variety of internet applications technology in developing countries, especially among

that have provided >3 billion people with a platform to their younger populations.[1] However, there is growing

connect in real‑time and share texts, messages, photos, recognition that excessive use of social media is a form of

and videos. The popularity of social media networks has behavioral addiction associated with high levels of anxiety

and depressive symptomatology.[2,3] Some researchers have

Address for correspondence: Dr. Saurav Basu,

even compared extreme cases of addiction to social media

Department of Community Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical comparable to substance‑related addictions involving

College, New Delhi, India. tobacco smoking or alcohol.[4]

E‑mail: saurav.basu1983@gmail.com

Submitted: 25‑Feb‑2020, Revised: 08‑Jul‑2020 This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of

Accepted: 12‑Aug‑2020, Published: 15-Feb-2021 the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 4.0 License,

which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially,

Access this article online as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under

the identical terms.

Quick Response Code

Website: For reprints contact: WKHLRPMedknow_reprints@wolterskluwer.com

www.indianjpsychiatry.org

How to cite this article: Basu S, Sharma R, Sharma P, Sharma N.

DOI:

Addiction-like behavior associated with social media usage in

undergraduate students of a government medical college in

10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_153_20

Delhi, India. Indian J Psychiatry 2021;63:35-40.

© 2021 Indian Journal of Psychiatry | Published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow 35

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org on Saturday, April 10, 2021, IP: 117.217.158.253]

Basu, et al.: Addiction to social media in medical students

Social media can promote the feeling of social envy 9, 10, 19), impaired control (Q. 3, 11, 12, 15, 16, 19),

and anxiety, and can potentially interfere with sleep.[5] withdrawal (Q. 13), tolerance (Q. 5, 6, 11, 12, 16, 18),

Responding to late‑night social media ping notifications decreased alternate pleasure (Q. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13),

on smartphones can reduce sleep quality, whereas blue and harmful use (Q. 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20). The SMAQ

light emissions can increase sleep latency by disturbing also corresponded to the four components of the CAGE

the circadian rhythm.[6] Furthermore, an extended number screening questionnaire for potential drinking‑related

of hours spent on social media contributes to sleep problems[18] and Griffith’s six core components of

displacement.[7] In younger age‑group students, poor addictions,[19] (b) Pretesting of the questionnaire was

sleep quality can cause cognitive impairment and reduced conducted in 10 students who were not part of the final

concentration.[8] Studies have also linked excessive social study, (c) Content validity of the items was determined by

media use with diminished academic performance in young two experts on behavioral health who went through each

students.[9] of the items and their pretest responses. Subsequently,

they, by consensus, accepted the appropriateness of all

The prevalence of social media addiction has been estimated the items subject to language modification in certain

to be particularly high among adolescents and young items. The response to the each of the SMAQ items

people in developed countries.[10,11] India, the country with was self‑rated by the students on a 6‑point Likert scale

the largest youth population globally, has become a world with options being 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree),

leader in the adoption of smartphones and mobile data in 3 (weakly disagree), 4 (weakly agree), 5 (agree), and

the past 5 years, which has materialized the growth and 6 (strongly agree). The total SMAQ score was the sum of

popularity of social media use.[12] However, there are very individual scores for all the 20 items of the questionnaire,

few studies that have evaluated social media addiction with higher scores indicating a greater risk of addiction

in India, especially with locally validated questionnaires. 2. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) ‑ The PSQI is a

A recent study estimated that 36.9% of students in Southern valid instrument used to differentiate “poor” from

India had social media addiction by using a questionnaire “good” sleep by measuring seven domains: subjective

adapted from Young’s internet addiction test.[13] A previous sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual

study among medical students in Delhi had reported sleep efficiency, and sleep disturbances, use of sleep

a high prevalence of mobile phone addiction, which medication, and daytime dysfunction over the last

coupled with academic stress and anxiety, possibly renders month.[20] The cutoff for poor and good sleepers

them susceptible to social media addiction and sleep was considered at a PSQI score >6, which has been

deprivation.[14] previously validated in Indian university students.[21]

We conducted the present study to assess social media Sampling and data collection

addiction in medical students using a self‑designed The college has five batches of undergraduate medical

questionnaire. students for the MBBS course lasting for five and a half years

duration. We selected a total of 95 students from among

MATERIALS AND METHODS the 250 cohorts in each batch, with final year students

and interns considered as one‑batch during participant

Design, setting, and participants selection. A sample size of ≥400 with item‑to‑respondent

We conducted a cross‑sectional study among adult medical ratio of 20:1 is considered excellent for factor analysis.[22]

undergraduate (MBBS) and interns of a government We selected the participants by simple random sampling

medical college in Delhi situated in Northern India during using a computer‑generated set of random numbers for

September–November 2019. All the students could read, selection through student roll numbers. The selected

comprehend, and respond in the English language, and it is participants were administered the questionnaires in groups

the official medium of instruction. in a separate lecture room. An investigator was present at

these sites during this time to resolve any participant query

Study instruments regarding filling of the questionnaires and also prevent any

1. We constructed a 20‑item social media addiction interpersonal interaction among the participants.

questionnaire (SMAQ) in the English language after the

application of the following steps: (a). Identification Statistical analysis

of domains that corresponded to the International We analyzed the data with the IBM SPSS Statistics for

Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision criteria for Windows, Version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

substance dependence syndrome,[15] and the inclusion

of items from the literature search and previously Handling of missing data

validated questionnaires related to behavioral and We assumed that the missing data was at random. We

technological addiction.[14,16,17] The SMAQ assessed excluded questionnaires with more than ≥4 incomplete

the presence of intense desire (Q.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, entries in the social media questionnaire. Missing items

36 Indian Journal of Psychiatry Volume 63, Issue 1, January-February 2021

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org on Saturday, April 10, 2021, IP: 117.217.158.253]

Basu, et al.: Addiction to social media in medical students

were imputed, taking the item median score as per the Psychometric properties of the social media addiction

gender and age‑group to which the participant belonged. questionnaire

The Cronbach’s alpha of the 20‑item SMAQ was 0.879 and

The quantitative data were expressed in terms of mean, the split‑half reliability coefficient was 0.765, indicating

median, and standard deviations (SDs) and qualitative data in very good reliability. The dataset was assessed to be

terms of frequency and proportions. The significance of the suitable for the application of PCA in terms of sampling

association between categorical variables was determined adequacy. The overall Kaiser‑Meyer‑Olkin (KMO) measure

by Chi‑square/Fisher’s exact test. The independent samples was 0.89 classifications of “Meritorious” according to

t‑test was applied to test for the significance of the mean Kaiser. All the individual KMO measures were >0.8. The

difference between groups. A P < 0.05 was considered correlation matrix showed that all variables had at least one

statistically significant. We also conducted a principal correlation coefficient >0.3. The Bartlett’s test of Sphericity

component analysis (PCA) of the SMAQ. was statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

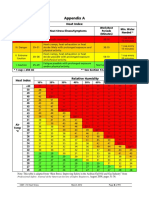

Ethical considerations We found four components that had eigenvalues >1, which

The study was approved with an exemption from full review explained 30.4%, 10.5%, 7.4%, and 6% of the total variance,

by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the medical college. respectively, thereby cumulatively explaining 54.7% of

We obtained written and informed consent from all the the total variance. Visual inspection of the Scree plot also

study participants, and we maintained data confidentiality, indicated that four components should be retained [Figure 2].

with the data being used for research purposes only. We observed strong loadings of impaired control items

on Component 1, decreased alternate pleasure items on

RESULTS Component 2, intense desire items on Component 3, and

harmful use items on Component 4. Component loadings

Participant characteristics and communalities of the rotated solution are presented

We distributed a total of 475 questionnaires to medical in Table 1.

undergraduate students and interns of the selected

medical college with a response rate of 100%. We excluded Construct validity of the social media addiction

51 questionnaires with incomplete responses, and hence, questionnaire

the effective sample size was 424. We enrolled 264 (62.3%) On dichotomizing responses into “agree” and “disagree”

male and 160 (37.7%) female participants. The mean (SD) categories, higher mean scores were seen for items

age of the participants was 19.83 (1.6) years. 1, 2, 3, 6 (eye‑opener/intense desire), 11 (cut‑down/

Social media usage Table 1: Rotated structure matrix for principal

The total typical weekly mean (SD) time spent on social component analysis with varimax rotation of a

media by the participants was 21.8 (11.2) hours, with 4‑component social media addiction questionnaire

adolescents reporting significantly lower time spent on social showing major loadings

media compared to older participants (P < 0.001), although Item Component Communalities

no association existed with participant gender (P = 0.165). 1 2 3 4

Popular social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube SAS16 0.832 0.722

were accessed more frequently by older or male students SAS15 0.735 0.629

SAS17 0.694 0.362 0.627

compared to adolescent or female students [Figure 1]. SAS12 0.683 0.326 0.591

SAS11 0.670 0.477

SAS10 0.695 0.319 0.588

SAS7 0.684 0.304 0.585

SAS9 0.630 0.388 0.548

SAS8 0.615 0.588

SAS13 0.478 0.312 0.473

SAS14 0.472 0.413 0.436

SAS6 0.390 0.465 0.412 0.563

SAS3 0.750 0.639

SAS1 0.655 0.496

SAS4 0.641 0.549

SAS2 0.608 0.445

SAS5 0.490 0.569 0.572

SAS19 0.320 0.687 0.592

SAS20 0.664 0.532

SAS18 0.598 0.476

Figure 1: Social media usage in medical students of Delhi Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis

(n = 424). *Mean number of days accessed in a typical week Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization

Indian Journal of Psychiatry Volume 63, Issue 1, January-February 2021 37

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org on Saturday, April 10, 2021, IP: 117.217.158.253]

Basu, et al.: Addiction to social media in medical students

tolerance) and 11, 15, 16 (impaired control) [Table 2]. spent on social media also correlated with higher addiction

Older students compared to their junior counterparts scores. The evaluation of item‑responses of the SMAQ

were significantly more likely to agree that “life would revealed that a majority of participants were unable to

be less interesting,” “they could not imagine living” reduce their time spent on social media despite wanting

and “felt unhappy and annoyed when not connected” to do so signifying the presence of tolerance and impaired

to social media. The students with poor quality sleep control.

were also significantly more likely to agree regarding the

harmful consequences of social media use compared to Although it is well‑established that school‑going adolescents

good sleepers [Table 3]. The average time spent on social are at high risk of social media addiction,[10] in the present

media showed a moderate correlation with the SMAQ study, college‑going adolescents reported less likelihood

score (r = 0.4, P < 0.001). of addiction‑like behavior compared to their senior

Association with sleep quality

The mean (SD) global PSQI score was 5.66 (2.6). We classified

276 (65.1%) participants as having a good sleep (PSQI ≤6)

and 148 (34.9) as having a poor sleep (PSQI ≥7). The

mean SMAQ score was significantly higher in the students

reporting poor sleep compared to those showing good

sleep quality [Table 4].

DISCUSSION

The exponential increase in social media users globally

intensifies the need for its measurement, which is particularly

challenging in the absence of validated instruments.[23] We

found the 20‑item SMAQ displayed acceptable psychometric

properties for the assessment of self‑reported social media

addiction in young medical undergraduates. Social media

addiction scores were significantly higher in poor sleepers Figure 2: Scree plot of a 4-component social media addiction

compared to good sleepers. Furthermore, increased time questionnaire

Table 2: Distribution of responses to the social media addiction questionnaire in medical students (n=424)

Item Question Corrected item‑total Cronbach’s alpha Mean

correlation if items deleted (SD)

1 Check my social media notifications as soon as I receive them 0.493 0.873 3.7 (1.6)

2 Check my social media notifications right after waking up from sleep 0.438 0.875 3.8 (1.8)

3 Check my phone for social media notifications even during classes 0.456 0.874 3.2 (1.7)

4 Constantly check my phone so as not to miss out on social media updates from groups/those I 0.554 0.871 2.8 (1.6)

follow/followers

5 Cannot imagine living without social media 0.510 0.872 2.7 (1.6)

6 Prefer spending time on social media when alone 0.526 0.872 3.8 (1.6

7 Feel life will be very less interesting without social media 0.457 0.874 3.1 (1.5)

8 Prefer communication with friends and family through social media 0.306 0.879 3.0 (1.6)

9 Feel my online friends on social media are more interesting and captivating than those offline 0.406 0.876 1.9 (1.2)

10 Feel my online personality in the world of social media to be more popular compared to that 0.432 0.875 2.2 (1.4)

offline

11 Often think that I should shorten my time spent on social media 0.414 0.876 4.2 (1.5)

12 Feel that I am increasingly spending more and more time on social media 0.563 0.871 3.6 (1.6)

13 Feel unhappy and annoyed when not connected to social media 0.589 0.870 2.6 (1.4)

14 Feel anxious and stressed on getting less than expected likes for a social media post like a 0.495 0.873 2.1 (1.4)

picture or video

15 Feel that my academic performance and productively suffers due to excessive social media usage 0.548 0.871 3.3 (1.7)

16 Feel that I am wasting my time on social media 0.519 0.872 3.9 (1.6)

17 Feel tired and lack adequate sleep from excessive social media use 0.535 0.871 3.0 (1.7)

18 See social media as an escape from the real world 0.483 0.873 3.0 (1.7)

19 Compulsively check for social media notifications even in places where it is dangerous to do so 0.488 0.873 2.0 (1.4)

like driving or crossing the street

20 Reading other people’s posts on social media makes me envious and feel that I am missing out 0.466 0.874 2.6 (1.6)

on things

38 Indian Journal of Psychiatry Volume 63, Issue 1, January-February 2021

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org on Saturday, April 10, 2021, IP: 117.217.158.253]

Basu, et al.: Addiction to social media in medical students

Table 3: Item agreement on the social media addiction questionnaire and association with age, gender, and sleep

quality among medical students (n=424)

Item Agree Gender Age (years) Sleep quality

number Male (n=264) Female (n=160) 18‑19 (n=187) ≥20 (n=237) Good (n=276) Poor (n=148)

1 249 (58.7) 157 (59.5) 91 (56.9) 106 (56.7) 143 (60.4) 157 (56.9) 92 (62.1)

2 262 (61.8) 166 (62.9) 95 (59.4) 108 (57.8) 154 (65) 170 (61.6) 92 (62.1)

3 197 (46.5) 120 (45.5) 77 (48.1) 83 (44.4) 114 (48.1) 125 (45.3) 72 (48.5)

4 152 (35.8) 100 (37.9) 52 (32.5) 60 (32.1) 92 (38.8) 101 (36.6) 51 (34.5)

5 133 (31.4) 85 (32.2) 48 (30) 49 (26.2) 84* (35.5) 76 (27.5) 57 (38.5)

6 254 (60) 155 (58.7) 98 (61.2) 112 (59.9) 142 (59.9) 159 (57.6) 85 (57.4)

7 184 (43.4) 118 (44.7) 66 (41.2) 68 (36.4) 116* (48.9) 104 (37.7) 80* (54)

8 162 (38.2) 106 (40.1) 56 (35) 71 (38) 91 (38.4) 102 (37) 60 (40.5)

9 48 (11.3) 31 (11.7) 17 (10.6) 18 (9.6) 30 (12.6) 26 (9.4) 22 (14.9)

10 83 (19.6) 54 (20.4) 29 (18.1) 36 (19.2) 47 (19.8) 45 (16.3) 38* (25.7)

11 304 (71.7) 181 (68.6) 122 (76.2) 127 (68) 177 (74.7) 190 (68.8) 114 (77)

12 230 (54.2) 144 (54.5) 85 (53.1) 96 (51.3) 134 (56.5) 143 (51.8) 87 (58.8)

13 110 (25.9) 73 (27.6) 37 (23.1) 37 (19.8) 73* (30.8) 68 (24.6) 42 (28.4)

14 88 (20.7) 57 (21.6) 31 (19.4) 33 (17.6) 55 (23.2) 54 (19.5) 34 (23)

15 197 (46.5) 120 (45.4) 77 (48.1) 84 (45) 113 (47.7) 113 (40.9) 84* (56.7)

16 260 (61.3) 162 (61.4) 98 (23.1) 115 (61.5) 145 (61.2) 152 (55) 108* (73)

17 172 (40.5) 102 (38.6) 70 (16.5) 78 (41.7) 94 (39.7) 98 (35.5) 74* (50)

18 164 (38.7) 102 (38.6) 62 (38.7) 72 (38.5) 92 (38.8) 91 (32.3) 73* (49.3)

19 73 (17.2) 49 (18.6) 24 (15) 28 (15) 45 (19) 40 (14.5) 33* (22.3)

20 133 (31.3) 81 (30.7) 52 (32.5) 53 (28.3) 80 (33.7) 78 (28.3) 55 (37.2)

*Statistically significant

Table 4: Construct validity of the social media addiction previously linked to diminished academic performance.[7,24]

questionnaire in medical students (n=424) In this study, nearly half (46.5%) of the students were in

Variable Total SMAQ score Mean Difference between P agreement with the view that excessive social media use

(n=424) (SD) 60.9 (17.5) means, 95% CI was negatively affecting their academic performance.

Age (years) However, another study in Eastern India reported a majority

18-19 187 (44.1) 58.8 (16.1) 3.7 (0.35-7.05) 0.028 of medical students having a positive perception of social

≥20 237 (55.9) 62.5 (18.4)

media impact on their academic performance.[25]

Gender

Male 264 (62.3) 60.9 (17.5) 0.07 (−3.4-3.5) 0.968

Female 160 (37.7) 60.9 (17.6) Finally, most participants did not agree that social media

Sleep quality diminished their interpersonal relationships, promoted

Good 276 (65.1) 59 (17.7) 5.3 (1.8-8.8) 0.003 narcissism, or impacted their self‑esteem, in contradiction

Poor 148 (34.9) 64.3 (16.7)

to a study in Norway,[11] suggesting significant cross‑cultural

CI – Confidence interval; SMAQ – Social media addiction questionnaire;

SD – Standard deviation differences in the long‑term influence of social media on an

individual’s personality.

counterparts reiterating the persistent addiction potential

of the technology among youth. In conclusion, self‑reported social media overuse leading

to addiction‑like symptoms was reported by a large

In this study, gender was not associated with the potential proportion of medical undergraduates when assessed

for social media addiction in contradiction to a previous with a self‑designed SMAQ. Despite the lack of compelling

study conducted in India that found male gender to be evidence for recognizing social media addiction as a

a risk factor.[13] However, another large‑scale study in disorder,[23] we found it was significantly associated with

Norway found women to be predisposed to a higher risk objective parameters like poor sleep quality.

of addiction to activities on social media[11] indicating

nonavailability of any definite evidence in studies limited by There are certain limitations to the study. In the absence

the cross‑sectional design. of an objective or gold standard for the measurement of

social media addiction,[26] we could not determine a cutoff

The study revealed that one in three medical undergraduates point for distinguishing addiction and lack of addiction.

experienced poor sleep, with bad sleepers more likely Moreover, as the collected data were self‑reported, it is

to report excessive social media use compared to good likely to be influenced by the social desirability bias. The

sleepers. This corroborates the evidence from previous test–retest reliability analysis was also not performed. The

studies, which also found worsening sleep with increasing cross‑sectional study design precluded the identification

duration of social media use.[7] Poor sleep has been of any potential causality between addiction and adverse

Indian Journal of Psychiatry Volume 63, Issue 1, January-February 2021 39

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org on Saturday, April 10, 2021, IP: 117.217.158.253]

Basu, et al.: Addiction to social media in medical students

health, academic or interpersonal problems in the students. 9. Azizi SM, Soroush A, Khatony A. The relationship between social

networking addiction and academic performance in Iranian students of

The estimated time spent on social media could be medical sciences: A cross‑sectional study. BMC Psychol 2019;7:28.

overestimated since multiple social media accounts can be 10. Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, et al.

Problematic social media use: Results from a large‑scale nationally

handled simultaneously and often in short bursts rather representative adolescent sample. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169839.

than in prolonged sessions. Finally, we conducted the 11. Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between

study in medical students who are more likely to have a addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self‑esteem: Findings from

a large national survey. Addict Behav 2017;64:287‑93.

better awareness of addiction compared to other student 12. Pew Research Center, “Mobile Connectivity in Emerging Economies”.

populations, reducing the generalizability of the study 2019. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp‑content/

uploads/sites/9/2019/03/PI_2019.030.07_Mobile‑Connectivity_FINAL.

findings. pdf. [Last accessed on 2019 Dec 31].

13. Ramesh Masthi NR, Pruthvi S, Phaneendra MS. A comparative study

on social media usage and health status among students studying in

Financial support and sponsorship preuniversity colleges of urban Bengaluru. Indian J Community Med

Nil. 2018;43:180‑4.

14. Basu S, Garg S, Singh MM, Kohli C. Addiction‑like behavior associated

with mobile phone usage among medical students in Delhi. Indian J

Conflicts of interest Psychol Med 2018;40:446‑51.

There are no conflicts of interest. 15. World Health Organization. The ICD‑10 Classification of Mental and

Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

REFERENCES 16. Al‑Menayes J. Psychometric properties and validation of the Arabic social

media addiction scale. J Addict 2015;2015:291743.

1. Clement J. Mobile Social Media‑Statistics & Facts. Available from: https:// 17. Cengiz S. Social media addiction scale‑student form: The reliability and

www.statista.com/topics/2478/mobile‑social‑networks/. [Last accessed on validity study. Turk Online J Educ Technol 2018;7:169‑82.

2019 Dec 31]. 18. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA

2. Lee‑Won RJ, Herzog L, Park SG. Hooked on Facebook: The role of social 1984;252:1905‑7.

anxiety and need for social assurance in problematic use of Facebook. 19. Griffiths MD. Is “loss of control” always a consequence of addiction? Front

Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2015;18:567‑74. Psychiatry 2013;4:36.

3. da Veiga GF, Sotero L, Pontes HM, Cunha D, Portugal A, Relvas AP. 20. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The

Emerging adults and Facebook use: The validation of the Bergen Facebook Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice

addiction scale (BFAS). Int J Ment Health Addict 2019;17:279‑94. and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193‑213.

4. Hofmann W, Baumeister RF, Förster G, Vohs KD. Everyday temptations: 21. Manzar MD, Moiz JA, Zannat W, Spence DW, Pandi‑Perumal SR,

An experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self‑control. J Pers Ahmed S BaHammam, et al. Validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index

Soc Psychol 2012;102:1318‑35. in Indian university students. Oman Med J 2015;30:193‑202.

5. Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A. A systematic review: The influence of 22. Tsang S, Royse CF, Terkawi AS. Guidelines for developing, translating,

social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi

adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth 2019;25:79-93. J Anaesth 2017;11:S80‑9.

6. Gooley JJ, Chamberlain K, Smith KA, Khalsa SB, Rajaratnam SM, 23. Zendle D, Bowden‑Jones H. Is excessive use of social media an addiction?

Van Reen E, et al. Exposure to room light before bedtime suppresses BMJ 2019;365:l2171.

melatonin onset and shortens melatonin duration in humans. J Clin 24. Andreassen CS, Pallesen S. Social network site addiction‑An overview.

Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:E463‑72. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:4053‑61.

7. Scott H, Biello SM, Woods HC. Social media use and adolescent sleep 25. Lahiry S, Choudhury S, Chatterjee S, Hazra A. Impact of social media on

patterns: Cross‑sectional findings from the UK millennium cohort study. academic performance and interpersonal relation: A cross‑sectional study

BMJ Open 2019;9:e031161. among students at a tertiary medical center in East India. J Educ Health

8. Ahrberg K, Dresler M, Niedermaier S, Steiger A, Genzel L. The interaction Promot 2019;8:73.

between sleep quality and academic performance. J Psychiatr Res 26. Andreassen CS. Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive

2012;46:1618‑22. review. Curr Addic Rep 2015;2:175‑8410.

40 Indian Journal of Psychiatry Volume 63, Issue 1, January-February 2021

You might also like

- The Neural Basis of Religious Cognition: Jordan Grafman, Irene Cristofori, Wanting Zhong, and Joseph BulbuliaDocument8 pagesThe Neural Basis of Religious Cognition: Jordan Grafman, Irene Cristofori, Wanting Zhong, and Joseph Bulbuliagion.nand100% (1)

- Urinalysis Lab Report 2Document7 pagesUrinalysis Lab Report 2salman ahmedNo ratings yet

- 5 Jurnal Pak Mahfudli 2020Document6 pages5 Jurnal Pak Mahfudli 2020aria.aulia.nNo ratings yet

- JFMPC 11 325Document5 pagesJFMPC 11 325Luis Arturo Huaman VicenteNo ratings yet

- Social Media Addiction Among Adolescents: Its Relationship To Sleep Quality and Life SatisfactionDocument11 pagesSocial Media Addiction Among Adolescents: Its Relationship To Sleep Quality and Life SatisfactionSAFWA BATOOL NAQVINo ratings yet

- Kec ReferenceDocument9 pagesKec ReferenceKhaira AdilaNo ratings yet

- Socila Media Detoxification ScaleDocument7 pagesSocila Media Detoxification ScaleHODPSYCHIATRY DEPT100% (1)

- Sablaturova Et Al. (2022)Document15 pagesSablaturova Et Al. (2022)AnaNo ratings yet

- Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences: Manjur Kolhar, Raisa Nazir Ahmed Kazi, Abdalla AlameenDocument7 pagesSaudi Journal of Biological Sciences: Manjur Kolhar, Raisa Nazir Ahmed Kazi, Abdalla AlameenKenneth FlorescaNo ratings yet

- Stressful Life Experiences Among Women With AUDDocument8 pagesStressful Life Experiences Among Women With AUDkanuNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry613265-1908886 003148Document5 pagesIndianJPsychiatry613265-1908886 003148Liza FathiarianiNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0286766Document14 pagesJournal Pone 0286766Sanvi prajuNo ratings yet

- Article 4 The - Influence - of - Social - Media - On - Body - DissatisfactDocument6 pagesArticle 4 The - Influence - of - Social - Media - On - Body - DissatisfactdivyanshuNo ratings yet

- Debate ArticleDocument20 pagesDebate ArticlehridanshhirparaNo ratings yet

- Diss FinalDocument27 pagesDiss FinalNasrawi SamNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Screen Time, Sleep Duration and Behavioural Disturbances in Urban and Rural High School ChildrenDocument24 pagesA Comparative Study of Screen Time, Sleep Duration and Behavioural Disturbances in Urban and Rural High School ChildrenAira RamosaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Social Media On Mental Health A StuDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Social Media On Mental Health A StusanglikarayeshaNo ratings yet

- Smartphone Addiction Reduction: Effectiveness of Print and Social Media EducationDocument9 pagesSmartphone Addiction Reduction: Effectiveness of Print and Social Media EducationIJPHSNo ratings yet

- A Study of Psychiatric Morbidity Among School Going AdolescentsDocument6 pagesA Study of Psychiatric Morbidity Among School Going AdolescentsfabianaNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument13 pagesContent ServerJohn Fredy Sanchez GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument18 pagesBackground of The StudyLost ChildeNo ratings yet

- University Students' Use of Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument34 pagesUniversity Students' Use of Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisMr. BeansNo ratings yet

- Parent-Adolescent Interaction and Risk of Adolescent Internet Addiction: A Population-Based Study in ShanghaiDocument11 pagesParent-Adolescent Interaction and Risk of Adolescent Internet Addiction: A Population-Based Study in ShanghaiAnindita Nayang SafitriNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Sleep Quality and Its Association With Problematic Internet Use Among University Students A Cross-Sectional Investigation in BangladeshDocument9 pagesAssessment of Sleep Quality and Its Association With Problematic Internet Use Among University Students A Cross-Sectional Investigation in BangladeshElham AjmotgirNo ratings yet

- (Lakkunarajah 2022) A Trying Time - PIU and Its Association With Depression and Anxiety During COVID-19Document9 pages(Lakkunarajah 2022) A Trying Time - PIU and Its Association With Depression and Anxiety During COVID-19Hana Lazuardy RahmaniNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Social Media Volume and Addiction On.5-1Document16 pagesThe Impact of Social Media Volume and Addiction On.5-1Maybeline Bilbao LastimadoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Coronavirus Imposed Lockdown On Indian Population and Their HabitsDocument10 pagesImpact of Coronavirus Imposed Lockdown On Indian Population and Their HabitsAkásh BhandwalkarNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Problem Technology Use, Life Stress, and Self-Esteem Among High School StudentsDocument9 pagesAssociations Between Problem Technology Use, Life Stress, and Self-Esteem Among High School Students73586817No ratings yet

- Social Media On StudentsDocument5 pagesSocial Media On StudentsHisham TariqNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 11133 v2Document21 pagesIjerph 19 11133 v2Ali ZunairaNo ratings yet

- Beyond Screen TimeDocument12 pagesBeyond Screen TimeGermán Eduardo Lagos SepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- The Emerging Crisis in University Students Essay Final 1Document5 pagesThe Emerging Crisis in University Students Essay Final 1api-665854486No ratings yet

- Social Media Use and Its Connection To Mental Health: A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesSocial Media Use and Its Connection To Mental Health: A Systematic ReviewSahadeva DasaNo ratings yet

- Addiction Like Behavior Associated With Mobile PhoneDocument6 pagesAddiction Like Behavior Associated With Mobile PhoneShwetha RameshNo ratings yet

- 46-Article Text-861-2-10-20221101Document13 pages46-Article Text-861-2-10-20221101djokopri07No ratings yet

- Emotional Disturbance and Neurological Effects of Overuse of Social MediaDocument13 pagesEmotional Disturbance and Neurological Effects of Overuse of Social Mediafahadmalik33000No ratings yet

- Social Media Addiction Among Vietnam Youths PatterDocument13 pagesSocial Media Addiction Among Vietnam Youths PatterBảo NgọcNo ratings yet

- Final Proposal 2Document10 pagesFinal Proposal 2shabinarana342No ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument6 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Internet AddicationDocument5 pagesInternet Addicationleila.mirzazadeh62No ratings yet

- The Emerging Crisis in University Students Essay Final RevisedDocument5 pagesThe Emerging Crisis in University Students Essay Final Revisedapi-665854486No ratings yet

- Journal of Sleep Research - 2023 - Dibben - Adolescents Interactive Electronic Device Use Sleep and Mental Health ADocument18 pagesJournal of Sleep Research - 2023 - Dibben - Adolescents Interactive Electronic Device Use Sleep and Mental Health AneiralejandroblpNo ratings yet

- Brainsci 12 01625 v3Document15 pagesBrainsci 12 01625 v3Joury 5No ratings yet

- Pros & Cons Impacts of Social MediaDocument2 pagesPros & Cons Impacts of Social MediaWan NursyakirinNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument23 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundAlthea ʚĩɞNo ratings yet

- Eclinicalmedicine: Yvonne Kelly Afshin Zilanawala, Cara Booker, Amanda SackerDocument10 pagesEclinicalmedicine: Yvonne Kelly Afshin Zilanawala, Cara Booker, Amanda SackerEva LibaNo ratings yet

- Psy224 Group 4 Final Paper PDFDocument49 pagesPsy224 Group 4 Final Paper PDFHanna BatanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Social Media Use On Learning Social InteDocument19 pagesEffect of Social Media Use On Learning Social InteAiko EugeniaNo ratings yet

- Initial Program Proposal Group3 4Document9 pagesInitial Program Proposal Group3 4api-577798077No ratings yet

- Parents Perception of Electronic Gadgets and Internet Use Among ChildrenDocument8 pagesParents Perception of Electronic Gadgets and Internet Use Among ChildrenpuneetsbarcNo ratings yet

- Research Social Media AddictionDocument23 pagesResearch Social Media AddictionldrnsolanoNo ratings yet

- Social Media Usage and Mental Health A CDocument12 pagesSocial Media Usage and Mental Health A Cmuhammad.shahzainahmedNo ratings yet

- EBSCO FullText 2022 12 12Document27 pagesEBSCO FullText 2022 12 12Rand MattaNo ratings yet

- TSWJ2021 2556679Document12 pagesTSWJ2021 2556679Tiago BaraNo ratings yet

- Functional Connectivity Changes in The Brain of Adolescents With Internet Addiction: A Systematic Literature Review of Imaging StudiesDocument20 pagesFunctional Connectivity Changes in The Brain of Adolescents With Internet Addiction: A Systematic Literature Review of Imaging StudieslukaonlineNo ratings yet

- Covid19hbmdl 2020Document9 pagesCovid19hbmdl 2020Alexandra IonițăNo ratings yet

- Psych Nursing EQDocument7 pagesPsych Nursing EQPriyanka paulNo ratings yet

- Social MediaDocument9 pagesSocial MediaMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Sexual Functioning During The Lockdown Period in India: An Online SurveyDocument8 pagesSexual Functioning During The Lockdown Period in India: An Online Surveygion.nandNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Smart Phone Addiction, Sleep Quality and Associated Behaviour Problems in AdolescentsDocument5 pagesPrevalence of Smart Phone Addiction, Sleep Quality and Associated Behaviour Problems in AdolescentsRupika DhurjatiNo ratings yet

- Schizotaxia - A Review - IJSP 2004Document8 pagesSchizotaxia - A Review - IJSP 2004gion.nandNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry632171-3970252 110142Document4 pagesIndianJPsychiatry632171-3970252 110142gion.nandNo ratings yet

- Awards CriteriaDocument4 pagesAwards Criteriagion.nandNo ratings yet

- Quality of Psychiatry Journals Published From.13Document5 pagesQuality of Psychiatry Journals Published From.13gion.nandNo ratings yet

- Das N Das S Medical Writers and GhostwriDocument6 pagesDas N Das S Medical Writers and Ghostwrigion.nandNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry618149-4008418 110804Document1 pageIndianJPsychiatry618149-4008418 110804gion.nandNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and EmploymentDocument13 pagesSchizophrenia and Employmentgion.nandNo ratings yet

- From The Desk of Vice President-Elect: Mrugesh VaishnavDocument1 pageFrom The Desk of Vice President-Elect: Mrugesh Vaishnavgion.nandNo ratings yet

- Early Onset Bipolar Disorder, Stress, and Coping Responses of Mothers: A Comparative StudyDocument10 pagesEarly Onset Bipolar Disorder, Stress, and Coping Responses of Mothers: A Comparative Studygion.nandNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry632146-3947242 105752Document6 pagesIndianJPsychiatry632146-3947242 105752gion.nandNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry632179-396519 110051Document5 pagesIndianJPsychiatry632179-396519 110051gion.nandNo ratings yet

- Sexual Functioning During The Lockdown Period in India: An Online SurveyDocument8 pagesSexual Functioning During The Lockdown Period in India: An Online Surveygion.nandNo ratings yet

- Telemedicine Practice Guidelines of India, 2020: Implications and ChallengesDocument5 pagesTelemedicine Practice Guidelines of India, 2020: Implications and Challengesgion.nandNo ratings yet

- Pain Threshold and Pain Tolerance As A Predictor of Deliberate Self-Harm Among Adolescents and Young AdultsDocument4 pagesPain Threshold and Pain Tolerance As A Predictor of Deliberate Self-Harm Among Adolescents and Young Adultsgion.nandNo ratings yet

- Body (13-112)Document100 pagesBody (13-112)gion.nandNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry631102-4698058 130300Document2 pagesIndianJPsychiatry631102-4698058 130300gion.nandNo ratings yet

- Ganser Syndrome: Intricacy in Diagnosis and ManagementDocument2 pagesGanser Syndrome: Intricacy in Diagnosis and Managementgion.nandNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Methods in Psychiatry in India: Landscaping The TerrainDocument10 pagesQualitative Research Methods in Psychiatry in India: Landscaping The Terraingion.nandNo ratings yet

- Long Term Management of SchizophreniaDocument11 pagesLong Term Management of Schizophreniagion.nandNo ratings yet

- 13 Common Errors in Psychopharmacology: EditorialDocument8 pages13 Common Errors in Psychopharmacology: Editorialgion.nandNo ratings yet

- Newer Documentary Practices As Per Mental Healthcare Act 2017Document7 pagesNewer Documentary Practices As Per Mental Healthcare Act 2017gion.nandNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry 2019 61 4 423 262795Document2 pagesIndianJPsychiatry 2019 61 4 423 262795gion.nandNo ratings yet

- Mental Healthcare Act 2017: Preface To The Supplement: Shahul Ameen, Mahesh Gowda, G. S. RamkumarDocument3 pagesMental Healthcare Act 2017: Preface To The Supplement: Shahul Ameen, Mahesh Gowda, G. S. Ramkumargion.nandNo ratings yet

- The F Word-Feminism and Its DetractorsDocument46 pagesThe F Word-Feminism and Its DetractorsSibel UlusoyNo ratings yet

- 1088 in Vitro & in Vivo Evaluation of Dosage Forms - USP 36 PDFDocument10 pages1088 in Vitro & in Vivo Evaluation of Dosage Forms - USP 36 PDFKarlaBadongNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Introduction RationaleDocument16 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction RationaleTaurus SilverNo ratings yet

- PDF Spirituality in Nursing Standing On Holy Ground 6Th Edition Mary Elizabeth Obrien Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Spirituality in Nursing Standing On Holy Ground 6Th Edition Mary Elizabeth Obrien Ebook Full Chaptercarl.jones252100% (1)

- Program Details: Day 1: Wednesday, December 18, 2019Document17 pagesProgram Details: Day 1: Wednesday, December 18, 2019fee faysal tusarNo ratings yet

- Prep 2011Document819 pagesPrep 2011Rita Maya HaddadNo ratings yet

- Hatchery Brochure PDFDocument8 pagesHatchery Brochure PDFUmair ShafiqueNo ratings yet

- Title of Proposal AcronymDocument51 pagesTitle of Proposal AcronymHadish BekuretsionNo ratings yet

- Notes - Stages of Alzheimer'sDocument1 pageNotes - Stages of Alzheimer'sSassNo ratings yet

- AD8A9d01 PDFDocument8 pagesAD8A9d01 PDFAfaceri InternationaleNo ratings yet

- GlenmarkDocument23 pagesGlenmarkKnow IT-Whats happening MARKETNo ratings yet

- BHHP 7-9 PDFDocument1 pageBHHP 7-9 PDFSiti MasturaNo ratings yet

- PP-2525 EMS Radio Report FormatDocument2 pagesPP-2525 EMS Radio Report FormatNunuy NuriahNo ratings yet

- New HookDocument5 pagesNew Hookhugeellis2No ratings yet

- Mental Health EssayDocument5 pagesMental Health Essaycameronbullard2000No ratings yet

- Part I - 13 Heat Stress 8Document1 pagePart I - 13 Heat Stress 8SKH CultureNo ratings yet

- Pricelist PT. DHS-KB PKLNGNDocument4 pagesPricelist PT. DHS-KB PKLNGNnur khasanahNo ratings yet

- Systems-Heart Dissection Lab - Answer KeyDocument1 pageSystems-Heart Dissection Lab - Answer KeyGiorde PasambaNo ratings yet

- TATA Power Scaffold Safety StandardDocument7 pagesTATA Power Scaffold Safety StandardDSG100% (1)

- Sumaoang C. - Exercise No. 1 - Follow UpDocument3 pagesSumaoang C. - Exercise No. 1 - Follow UpBogartNo ratings yet

- UnmadaaDocument34 pagesUnmadaaArathi laxman100% (1)

- Essentials of Prosthetics and Orthotics With Mcqs and Disability Assessment Guidelines 1st EditionDocument6 pagesEssentials of Prosthetics and Orthotics With Mcqs and Disability Assessment Guidelines 1st EditionYasir RasoolNo ratings yet

- Social Movement Inclusive Citizenship and Participatory GovernanceDocument7 pagesSocial Movement Inclusive Citizenship and Participatory GovernancePhilippines QatarNo ratings yet

- Intermediate 2 B (1 - 5) RespuestasDocument9 pagesIntermediate 2 B (1 - 5) RespuestasUserMotMooNo ratings yet

- LLDA Vs CA - Case DigestDocument1 pageLLDA Vs CA - Case DigestOM MolinsNo ratings yet

- 25.signal HIV Immuno DotDocument5 pages25.signal HIV Immuno DotprastacharNo ratings yet

- Cadcor Safety ManualDocument54 pagesCadcor Safety ManualMARY ANN GUEVARRANo ratings yet

- DOE Standard - Hoisting and Rigging - 2020 UpdateDocument39 pagesDOE Standard - Hoisting and Rigging - 2020 UpdateLogic TurnipNo ratings yet

- Health First SemDocument17 pagesHealth First SempadmaNo ratings yet