Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Hindu As Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh

The Hindu As Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh

Uploaded by

Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Persepolis IODocument1 pagePersepolis IOVikas Tanwar100% (1)

- The 102 101 Questionnaires For Moorish Children and Moorish AmericansDocument11 pagesThe 102 101 Questionnaires For Moorish Children and Moorish AmericansRaziel Bey100% (3)

- 86 Tarbiat e Aulad Eng - PDFDocument47 pages86 Tarbiat e Aulad Eng - PDFAzadar HussainNo ratings yet

- Communal Violence in Twentieth Century Colonial Bengal - An Analytical Framework by Suranjan DasDocument18 pagesCommunal Violence in Twentieth Century Colonial Bengal - An Analytical Framework by Suranjan DasSumon ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Ranjan2017 Article UnravelingTheNarrativesOfAdivaDocument9 pagesRanjan2017 Article UnravelingTheNarrativesOfAdivaLakshmi SachidanandanNo ratings yet

- Bhadralok Communalism in Bengal 1932 194Document16 pagesBhadralok Communalism in Bengal 1932 194maham sanayaNo ratings yet

- Importance of DecentralisationDocument3 pagesImportance of DecentralisationShivangi ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- MukhopadhyayDocument30 pagesMukhopadhyaypRice88No ratings yet

- Land Acquisition Compensation in India A Thumb Rule Ijlljs v2 n1 Jan15Document22 pagesLand Acquisition Compensation in India A Thumb Rule Ijlljs v2 n1 Jan15bac hoNo ratings yet

- Between Global Flows and Local Dams: Indigenousness, Locality, and The Transnational Sphere in Jharkhand, IndiaDocument34 pagesBetween Global Flows and Local Dams: Indigenousness, Locality, and The Transnational Sphere in Jharkhand, IndiaBrandt PetersonNo ratings yet

- Land Acquisition and Development Induced Displacement: India and International Legal FrameworkDocument13 pagesLand Acquisition and Development Induced Displacement: India and International Legal FrameworkAshish pariharNo ratings yet

- Monika Verma-RETURN of POLITICS of NATIVISM in Maharashtra-2011Document13 pagesMonika Verma-RETURN of POLITICS of NATIVISM in Maharashtra-2011anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- J 51 Calq 2021 99Document18 pagesJ 51 Calq 2021 99Shubhra AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Jal, Jangal Aur Jameen - ' The Pathalgadi Movement and Adivasi Rights PDFDocument5 pagesJal, Jangal Aur Jameen - ' The Pathalgadi Movement and Adivasi Rights PDFDiXit JainNo ratings yet

- Hills Valley Divide As A Site of ConfliDocument27 pagesHills Valley Divide As A Site of ConfliSangha RajNo ratings yet

- Ghosh - Between Local Flows & Global DamsDocument34 pagesGhosh - Between Local Flows & Global DamsanirbanNo ratings yet

- Devadasis Dharma and The StateDocument11 pagesDevadasis Dharma and The StatePriyanka MokkapatiNo ratings yet

- Law of The LandlessDocument29 pagesLaw of The LandlessSandeep ShankarNo ratings yet

- Project On DecentralizationDocument38 pagesProject On Decentralizationkartikbag67No ratings yet

- Human RightDocument18 pagesHuman Rightadvocatekishanrhc1993No ratings yet

- Ghafur HomesforHumanDevelopmentDocument27 pagesGhafur HomesforHumanDevelopmentNazifa SubhaNo ratings yet

- Reference 1Document15 pagesReference 1Hira Ashfaq SubhanNo ratings yet

- Aggressive Land Development of Ancestral DomainsDocument6 pagesAggressive Land Development of Ancestral DomainsDenise Reign Mercado MutiaNo ratings yet

- Socio Assignent 3Document3 pagesSocio Assignent 3Ausmiita SarkarNo ratings yet

- Communication For Social Change I365Document9 pagesCommunication For Social Change I365xzvnjmdtsjNo ratings yet

- POl SC ProejctDocument27 pagesPOl SC Proejctsara.chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Political LeadershipDocument12 pagesPolitical LeadershipSandie Daniel GabalunosNo ratings yet

- Quantifying The Impact of Social Mobilisation in RDocument55 pagesQuantifying The Impact of Social Mobilisation in RLutful HakimNo ratings yet

- Sample ProposalDocument12 pagesSample ProposalBubbles Beverly Neo AsorNo ratings yet

- Legal Pluralism and Urban Land Tenure in India: ArticleDocument12 pagesLegal Pluralism and Urban Land Tenure in India: ArticleShikafaNo ratings yet

- Aleaz MadrasaEducationState 2005Document11 pagesAleaz MadrasaEducationState 2005Agniswar GhoshNo ratings yet

- Globalization of LawDocument24 pagesGlobalization of LawEmil KledenNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Constitutional Morality in IndiaDocument6 pagesThe Evolution of Constitutional Morality in IndiaSrushti ShashikumarNo ratings yet

- Of Marriage, Divorce and CrimiDocument26 pagesOf Marriage, Divorce and Crimiadvocate.karimaNo ratings yet

- Socio-Book ReviewDocument14 pagesSocio-Book ReviewAdishree KrishnanNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 106.208.148.124 On Wed, 14 Sep 2022 12:29:50 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 106.208.148.124 On Wed, 14 Sep 2022 12:29:50 UTCKshitij KumarNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Big BusinessmenDocument33 pagesPakistan's Big BusinessmenEylemNo ratings yet

- Land Grabbing Under The Cover of Law AreDocument43 pagesLand Grabbing Under The Cover of Law AresriramnatrNo ratings yet

- Economic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyDocument8 pagesEconomic and Political Weekly Economic and Political Weeklylokesh chandra ranjanNo ratings yet

- Ramsey, Charles - Covenantal Pluralism in Pakistan - Assessing The Conditions of Possibility (2021)Document14 pagesRamsey, Charles - Covenantal Pluralism in Pakistan - Assessing The Conditions of Possibility (2021)Pedro SoaresNo ratings yet

- Rezensiert Von:: © H-Net, Clio-Online, and The Author, All Rights ReservedDocument2 pagesRezensiert Von:: © H-Net, Clio-Online, and The Author, All Rights ReservedArchisha DainwalNo ratings yet

- Herklotz Holz LawinContext SAChrDocument9 pagesHerklotz Holz LawinContext SAChrAakash KNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument10 pagesSynopsisittifaqanNo ratings yet

- Utsa Patnaik-On The Evolution Class of Agricultural Labourers in India-1983Document23 pagesUtsa Patnaik-On The Evolution Class of Agricultural Labourers in India-1983anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Project Towards The Partial Fulfilment of Assessment in The Subject of Family LawDocument8 pagesProject Towards The Partial Fulfilment of Assessment in The Subject of Family LawShubh DixitNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Tribal Politics in KeralaDocument7 pagesContemporary Tribal Politics in KeralaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Cooperation and AmbedkarismDocument8 pagesCooperation and AmbedkarismAjay ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Gender Equality, Inclusivity and Corporate Governance in IndiaDocument24 pagesGender Equality, Inclusivity and Corporate Governance in Indiammonemmtwo9925No ratings yet

- Gender Equality, Inclusivity and Corporate Governance in IndiaDocument24 pagesGender Equality, Inclusivity and Corporate Governance in Indiammonemmtwo9925No ratings yet

- Democracy and Social Justice in India Lessons From Lohias SocialismDocument14 pagesDemocracy and Social Justice in India Lessons From Lohias Socialismshimlahites0% (1)

- Report AnnemiekDocument19 pagesReport AnnemiekammyNo ratings yet

- Jaasarticle09 12 21Document16 pagesJaasarticle09 12 21Anugrah EkkaNo ratings yet

- Partha Chatterjee - EPW.2008.response PDFDocument5 pagesPartha Chatterjee - EPW.2008.response PDFAakansha MukhiaNo ratings yet

- Imagining The Tribe in Colonial and Post-Independece IndiaDocument16 pagesImagining The Tribe in Colonial and Post-Independece IndiaVanshika KunduNo ratings yet

- 2011 AbstractsDocument328 pages2011 AbstractsAnonymous n8Y9NkNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Approaches of Local Government: Finding Applicable Approaches To Analyze Bangladesh's Local GovernanceDocument8 pagesTheoretical Approaches of Local Government: Finding Applicable Approaches To Analyze Bangladesh's Local Governancesatudas149No ratings yet

- Rural Governance AssignmentDocument13 pagesRural Governance Assignmentakhil karunanithiNo ratings yet

- Regionalism in India: Potti SriramuluDocument10 pagesRegionalism in India: Potti SriramuluAgam ヅ AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Covenantal Pluralism in BangladeshDocument17 pagesCovenantal Pluralism in Bangladeshc_christine_fairNo ratings yet

- Journal4thIssue 2022Document11 pagesJournal4thIssue 2022Anushka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Defining IndigeneityDocument20 pagesDefining IndigeneityJoshua Parks100% (1)

- Reclaiming The Nation Muslim Women and TDocument12 pagesReclaiming The Nation Muslim Women and TYashica HargunaniNo ratings yet

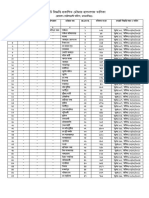

- M Ru Weáwß Cökvwkz Gšrvi NVJBVMV' ZVWJKV: Cvzv-.......Document3 pagesM Ru Weáwß Cökvwkz Gšrvi NVJBVMV' ZVWJKV: Cvzv-.......Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- Aeration of Water Supplies For Fish Culture in Flowing WaterDocument5 pagesAeration of Water Supplies For Fish Culture in Flowing WaterRafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh (BGD) : Administrative Boundary Common Operational Database (COD-AB)Document2 pagesBangladesh (BGD) : Administrative Boundary Common Operational Database (COD-AB)Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- D V Wku A Vkzqvkvjpvi: BBW Wrs BBKVG, Wvbfviwmdvbwqs WV Qu&M A Vû Ggcviqvwis DB GB BB Evsjv 'KDocument2 pagesD V Wku A Vkzqvkvjpvi: BBW Wrs BBKVG, Wvbfviwmdvbwqs WV Qu&M A Vû Ggcviqvwis DB GB BB Evsjv 'KRafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- Caste-Based Discrimination in Bangladesh IIDS Working PaperDocument68 pagesCaste-Based Discrimination in Bangladesh IIDS Working PaperRafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- DR Lutfor Rahman - Bangla Academy (1962)Document91 pagesDR Lutfor Rahman - Bangla Academy (1962)Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- The Standards of Weights and Measures Ordinance, 1982 - Ordinance No. Xii of 1982 - English Version - OriginalDocument33 pagesThe Standards of Weights and Measures Ordinance, 1982 - Ordinance No. Xii of 1982 - English Version - OriginalRafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- Gazette of East Pakistan1966Document31 pagesGazette of East Pakistan1966Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- Savar Second City.Document155 pagesSavar Second City.Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- NarayanganjDocument188 pagesNarayanganjRafiur Rahman Khan SaikotNo ratings yet

- Urdu-Hindi Controversy: by Harris SheikhDocument11 pagesUrdu-Hindi Controversy: by Harris SheikhHarris SheikhNo ratings yet

- Rapor STS Ganjil 2023 FixDocument54 pagesRapor STS Ganjil 2023 Fixg-69962692-13No ratings yet

- Print PDFDocument7 pagesPrint PDFprincemuchono0No ratings yet

- Sahih al-Bukhari 5590 - Drinks - كتاب الأشربة - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)Document1 pageSahih al-Bukhari 5590 - Drinks - كتاب الأشربة - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)tkv8npwkfbNo ratings yet

- 2022 09 23 Sisa To Penagihan BillerDocument1,484 pages2022 09 23 Sisa To Penagihan Billerjhon parkurNo ratings yet

- Simnani Ala Dawlah2017 KSDocument16 pagesSimnani Ala Dawlah2017 KSMuzamil Khan50% (2)

- CURE1110 Religion and Contemporary Life 2019-2020 T2 - OutlineDocument5 pagesCURE1110 Religion and Contemporary Life 2019-2020 T2 - OutlinejonNo ratings yet

- Printable Ramadan Planner 2022 JjemghDocument48 pagesPrintable Ramadan Planner 2022 JjemghArsalan AbdullahNo ratings yet

- 2013 DeedatDocument301 pages2013 DeedatDawudBryantNo ratings yet

- Salvation of Abu Talib Abstract - 0Document2 pagesSalvation of Abu Talib Abstract - 0Carlos Cabral JrNo ratings yet

- Concept of Public AdministrationDocument4 pagesConcept of Public AdministrationHamza Bilal100% (3)

- Amber, 2002, Islamic - PsychologyDocument7 pagesAmber, 2002, Islamic - Psychologyمحمد نصير مسرومNo ratings yet

- India ResearchDocument86 pagesIndia Researchms_paupauNo ratings yet

- AI Aur Sunni Naujawan (Roman Urdu)Document26 pagesAI Aur Sunni Naujawan (Roman Urdu)Mustafawi PublishingNo ratings yet

- Tentatif & Master PlanDocument6 pagesTentatif & Master PlanNur NabilahNo ratings yet

- Methodology of Interpretation in Tafsīr Anwār Al-Bayān Fī Kashf Isrār al-Qur'ān:An Analytical StudyDocument20 pagesMethodology of Interpretation in Tafsīr Anwār Al-Bayān Fī Kashf Isrār al-Qur'ān:An Analytical StudyShahid RafiqNo ratings yet

- Detailed SunnatDocument253 pagesDetailed SunnatmahdeeeeeeeeNo ratings yet

- Pembagian Input FotoDocument18 pagesPembagian Input FotoRofiqoh nurul ANo ratings yet

- A Shijra QuadriaDocument5 pagesA Shijra Quadriafatima atherNo ratings yet

- ID Kajian Hukum Perjanjian Perkawinan Di Kalangan Wni Islam Studi Di Kota Medan PDFDocument17 pagesID Kajian Hukum Perjanjian Perkawinan Di Kalangan Wni Islam Studi Di Kota Medan PDFsabila azilaNo ratings yet

- Doa Doa JumatanDocument1 pageDoa Doa JumatanSaeran SaeranNo ratings yet

- Khandani Shakh Jadd Nama-Khankha-E-Chisht Ahl-E-Bahisht Bagalkot Shrief KarnatakaDocument1 pageKhandani Shakh Jadd Nama-Khankha-E-Chisht Ahl-E-Bahisht Bagalkot Shrief KarnatakaSayyedna shah khwaja Basheer Ahmed ChishtipeeraNo ratings yet

- Doa Bada ShalatDocument3 pagesDoa Bada ShalatMuhammad Maulana Panji SaputraNo ratings yet

- Tareeqa Jadeeda Fi Taleem Ul ArabiaDocument217 pagesTareeqa Jadeeda Fi Taleem Ul ArabiaChahra IlhamNo ratings yet

- A Question of Identity in Pakistani NovelDocument15 pagesA Question of Identity in Pakistani Novelasim aqeelNo ratings yet

- Religious and Moral EducationDocument4 pagesReligious and Moral EducationAbena KonaduNo ratings yet

- Alaeddin and The Enchanted LampDocument133 pagesAlaeddin and The Enchanted LampGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

The Hindu As Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh

The Hindu As Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh

Uploaded by

Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Hindu As Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh

The Hindu As Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh

Uploaded by

Rafiur Rahman Khan SaikotCopyright:

Available Formats

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic

Journal

13 | 2016

Land, Development and Security in South Asia

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations

in Contemporary Bangladesh

Shelley Feldman

Electronic version

URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/4111

DOI: 10.4000/samaj.4111

ISSN: 1960-6060

Publisher

Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS)

Electronic reference

Shelley Feldman, « The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh »,

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 13 | 2016, Online since 08 March 2016,

connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/4111 ; DOI : 10.4000/

samaj.4111

This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0

International License.

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 1

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and

Land Relations in Contemporary

Bangladesh

Shelley Feldman

Depeasantization and victimization are active

elements in the process of [exclusion,] […] Not only

[are] the Muslim peasants depeasantized,

pauperized and lumpenized on their arrival in

India, the Hindu peasantry of Bangladesh is

cynically and most systematically robbed of land

on communal considerations in the villages of

Bangladesh and this [results in] peasants […]

[being] forced to flee. The catalyst in this case is

the enemy (vested) property laws (Trivedi 2007).

Introduction

1 In this paper, I argue that the Enemy or Vested Property Act (VPA)1 and its multiple

reforms provide a window into on the construction of Hindu citizens of Bangladesh as

Other. I draw particular attention to the regimes in power since 1971 for what they reveal

about the reproduction of a minority population, since the country is premised on

democratic principles of equality among citizens. In so doing, I expose the paradox that

resides in the relationship between the genocidal struggle for independence and

secularism and a presumed ethnic, rather than religious, basis for belonging. I suggest

that the construction of Hindus as the other legitimates state appropriations2 of their

property and, by challenging their rights to land ownership as a right of all citizens,

constructs Hindus as a threat to national security. This construction legitimates land

appropriation in the interest of state needs, as well as for private accumulation. It finds a

parallel in Ayesha Jalal’s suggestion of a significant feature legitimating the offensive

position of Pakistan during the independence struggle: ‘If Hindu India is the enemy

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 2

without, the proponents of regional autonomy alongside the ungodly secularists3 are the

enemies within’ (Jalal 1995: 82).

2 To explore these themes, I draw on interviews conducted during three periods of

fieldwork, in 2013 in Rajshahi, a northern district of Bangladesh, and in 2014 in Dhaka, as

well as over the course of numerous field trips in Bangladesh during earlier stays in the

country. I also draw on lengthy discussions with a key informant, a scholar from

Bangladesh temporarily in the U.S. Finally, the argument builds on cases examined from

the Dacca (subsequently Dhaka) Law Review, 1960–2011, although it does not focus on

particular cases, and an exploration of newspaper reports that are critical for signalling

recent public expressions of violence against Hindus. The discussion unfolds first by

examining land appropriation as a relation of subjection. This is followed by an

examination of the making of majoritarian rule, both before and after independence,

including a focus on the current conjuncture about what it portends for property

relations and the differential rights of Bangladeshi citizens. The principal purpose of the

paper, however, is not to offer new evidence on land appropriation. Rather, I provide a

new interpretation of extant evidence, one that moves from structuralist accounts that

contribute to our understanding of accumulation practices, to an argument for the

inseparability of accumulation practices in/as a relation of rule and subjection. In other

words, I argue that distinct from studies that view subjection as a response to structural

and political change, these processes are relational and co-constitutive. I also show that

marking people as the other from whom property appropriations could be justified was

not an outcome of a single policy, fixed once and for all, but, instead, a set of ongoing and

contradictory policy reforms and practices that reproduce both difference and

majoritarian rule.

Land appropriation as a relation of subjection

3 Debates focused on land grabbing, including both large-scale appropriations by

governments as well as everyday takings from small producers, have renewed interest in

Marx’s conception of ‘so-called primitive accumulation’ understood as the enclosure of

private land holdings and the separation of direct producers from their means of

subsistence and production.4 These debates have opened to scrutiny the character of

accumulation processes, as well as their costs for particular constituencies who are most

often the poor and unprotected. The basis of these debates is Marx’s understanding of

primitive accumulation that transforms ‘the social means of subsistence and of

production into capital [and] the immediate producers into wage labourers’ (Marx 1983:

668).

4 Crucially, Marx presupposes ‘the complete separation of labourers from all property in

the means by which they can realize their labour’ as the basis of capitalism. Debate

continues, however, as to whether this separation or ‘historical premise’ refers solely to

the original appropriation or to an ongoing process of social transformation. As Marx

maintains:

As soon as capitalist production is once on its own legs, it not only maintains this

separation, but reproduces it on a continually extending scale. The process,

therefore, that clears the way for capitalist production, can be none other than the

process which takes away from the labourer the possession of his means of

production (Marx 1983: 668, emphasis added).

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 3

5 Two points are significant for the discussion to follow. One is that the appropriation of

land is central to the reorganization of capitalist agriculture and, hence, to processes of

accumulation. This builds on the assumption that meeting the world’s food needs

requires increasingly large-scale commercial agricultural production that can no longer

be accommodated under the mix of large, medium, subsistence, and under-subsistence

producers. This assumption, and declining support for small-scale agricultural producers,

sets the conditions for the consolidation of landholdings. This assumption is part of a

neoliberal development strategy that supports investment in non-farm work, credit, and

micro-enterprise development under the premise that wage labour is better able than

agriculture to meet the reproduction needs of small-scale producers.5 Second, and

following from the separation of people from their productive resources, is the need to

continually reproduce this separation through both direct and indirect property

appropriations. Together, these processes enable ongoing, if historically contingent,

relations of accumulation. Further, tethering land appropriation and the

commodification of labour power produces particular subjectivities, since how people

make a life through work and social reproduction casts them in relation to each other, to

their communities as sites marked by specific senses of security and responsibility, and to

the constitution of a national imaginary that shapes identification, identity, and

belonging.6

6 Following S. Charusheela (2011: 323), I engage the connection between land appropriation

and the violent establishment ‘of the conditions for the subjugation and subjective

emergence of the wage labourer’, a relation that is particularly suggestive in examining

contemporary land relations in Bangladesh, with three critical qualifications. First, unlike

the need to release labour to support a large and emergent labour market that explained

the first so-called primitive accumulation, today the expropriation of people from their

property ‘release[s] a set of assets (including labour power) at very low (and in some

instances zero) cost. Over-accumulated capital can seize hold of such assets and

immediately turn them to profitable use’ (Harvey 2003: 149). This expropriation, often by

private capital, has transformed the landscape in the areas around Bangladeshi cities,

particularly Dhaka, as agricultural land becomes the ground for both industrial

production and residential communities. Under eminent domain, the state has also seized

large tracts of peri-urban land for military housing.

7 A second qualification of Charusheela’s contribution concerns the people from whom

private property can be confiscated. To be sure, the category of the poor is highly

differentiated in ways that lead one to ask: From whom, among the vulnerable, can land

or property grabs be legitimated without sparking broad-based reprisal? What context

shapes identification of this constituency, and precisely how are property and resource

grabs justified and enacted based upon the specificity of a group’s identity? These

questions raise the third qualification of Charusheela’s suggestive intervention, the

importance of understanding relations of rule and the constitutive character of

belonging, identification, and national identity for policy reform. Focusing on this

constitutive process draws attention to how institutional, bureaucratic, and governance

practices shape the ways in which rule is enacted. It also draws attention to how building

legitimacy, as the substance of rulemaking, aids in establishing who belongs and who is

marginalized or excluded, who has rights, and whose rights can be compromised without

fear of public outrage. Included in this process is what Philip Abrams (1988: 61)

understands as the building of hegemony, constituted by institutional and discursive

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 4

practices that are often enshrined in law, embedded in the ‘public aspects of politics’

(Abrams 188: 61), and routinized in symbolic gestures and moral judgments. These

processes provide the ground for patterns of social inclusion/exclusion,7 ethnicization, 8

and minoritization,9 which produce communities in a hierarchy of economic and social

security positioned in relation to their rights and ability to demand legal accountability.

8 In examining these relations of othering, I ask the following questions: How do the social

relations that embody land and property appropriations, notorious for their enactment

through ‘conquest, enslavement, robbery, murder, and in short, force, [which] plays the

greatest part’ (Marx 1983: 668), help to create particular kinds of subjects? What role does

policy and governance, including claims of national interest and security play in

legitimating land appropriation? What, for example, is the role of bureaucratic elites in

facilitating and securing land grabs through violent, as well as non-violent, means?

Finally, how do rhetorics of othering secure the legitimacy of dispossession among

minority populations? Responses to these questions will expose the mutually constitutive

character of relations of accumulation and subjection.

9 As a predatory political formation, Bangladesh’s so-called democracy includes universal

suffrage and free and fair elections. As popularly understood, however, the political

process consists of competition over which party will benefit from the ‘unethical but,

nevertheless, socially accepted’ struggle over state resources and privileges, including

exploitation of the environment and extractive and natural resources (Pertev 2009: 9). A

variant of crony capitalism, these predations entail illegal appropriations that further the

control and concentration of scarce resources that can be leveraged for state patronage,

as well as for private gain. But importantly, such appropriations are not usually directed

at an undifferentiated vulnerable population. Rather, such seizures target particular

populations through practices that are legitimated in state rule. This is precisely the case

in Bangladesh, where Hindu citizens have been subjected to property appropriations

legitimized by the Enemy/Vested Property Act, established specifically to justify land

enclosures of their property. The result is the constitution of forms of rule and subjection

that are best understood as both the process and product of the construction of the Hindu

as other.

The Vested Property Act (VPA) and the making of

majoritarian rule: the East Pakistan period

10 Following the 1947 partition of India into the predominantly Muslim state of Pakistan,

including its East and West Wings, and the Hindu majority state of India, Mohammad Ali

Jinnah, the founder and first governor general of Pakistan, initially repudiated the

theocratic foundations of the Pakistani state, noting that, ‘You may belong to any religion

or caste or creed. That has nothing to do with the business of the state. We are starting

with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of the state’

(Jinnah 2004). But despite this proclamation, he soon thereafter attempted to build a

nationalist project in an idiom of a shared Urdu language, ostensibly to create a sense of

collective belonging that would bring the East and West Wings together. The argument

against Bengali, and for Urdu, was that Bengali did not comport with the construction of

a national narrative articulated in the sacralized language and cultural traditions of

Islam. At this time, the Hindu population was estimated to be between 10 and 12 million

with Muslims accounting for 32 million (Lambert 1950, Schechtman 1951). Thus,

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 5

introducing Urdu as the lingua franca was a response to the perceived threat of Bengali

nationalism in the East, where Bengali language and culture were infused with Hindu

religious and linguistic idioms, and a significant proportion of the population was Hindu.

This language initiative can thus be understood as an effort to mark Hindus as a

community distinct from East Bengal’s Muslim majority.

11 In addition to the 1948 struggle against Urdu, the 1949 effort to introduce the Arabic

script instead of the Sanskritized Devanagari Bengali script, led to the Language

Movement—bhasha andolan—in East Pakistan. The Movement sought recognition of the

East as a multi-religious community whose mark of national belonging was shared

language rather than religious identity.10,11 A bloody battle ensued following a five-year

struggle against the imposition of Urdu as the lingua franca. A number of university

students were killed and today, for many Bengalis, Hindus and Muslims alike, Ekushy, 21

February, remains a hallmark of national pride.

12 Struggles over recognition of the multiethnic character of East Pakistan, and the

particular place of Hindus in the body politic, also included the State’s proposal for a

separate electorate for minorities. But Bengali Muslims and Hindus alike rejected this

proposal, even as a 1956 Constitutional provision only allowed Muslims to serve as the

president of Pakistan. Arguing against the proposal were Basant Kumar Das, Peter Paul

Gomez and B.K. Dutta, as well as H.S. Suhrawardy and Mujib-ur-Rahman,12 all members of

the Constituent Assembly that included Hindus, Christians, and Muslims. They claimed

that the proposal would relegate minorities to the status of second-class citizens and,

significantly, would put Muslims residing in India at risk, since the politics of the period

reflected an implicit or explicit engagement with policies in India.

13 Passage of The East Bengal (Emergency) Requisition of Property Act (XIII of 1948) 13 was

Jinnah’s final action aimed at marking Hindus as second-class citizens. The Act

empowered the government to ‘acquire, either on a temporary or permanent basis, any

property it considered needful for the administration of the state’ (Barkat et al. 1997: 27).

Although claimed to be necessary to meet the administrative needs of the newly

independent province, including the need to accommodate government offices and civil

servants, it also obfuscated illegal appropriations, particularly of Hindus (Mohsin 2004).

According to Lambert (1950), ‘80 percent of the urban property in East Bengal was in the

hands of Hindus’, as were large estates. The value of real property and other assets

assumed abandoned in East Pakistan ‘was officially estimated by the Chief Minister of

West Bengal at 870 million rupees (US$ 182,700,000)’ (Schechtman 1951: 412). Such

unequal ownership of property helped to publically justify state confiscations without

compensation.

14 Thus, in theory, the agreement signed by Prime Ministers Liaquat Ali Khan of Pakistan,

and Jawaharlal Nehru of India on 10 April 1950, provided a hopeful sign for migrants, as it

acknowledged that refugees would be permitted to take with them their movable

personal effects, including up to 150 rupees. It further acknowledged that immovable

property would not be confiscated, even if occupied by another person, if its owner

returned to East Pakistan before the end of 1950. If, however, landowners chose not to

return, they were free to either sell or exchange their property (Schechtman 1951: 412).

Significantly, the agreement promised that ‘[r]ent or compensation for requisitioned

property was to be promptly assessed and paid over to the owner’ (Schechtman 1951:

412). In practice, however, these Acts instead dispossessed Hindus who opted for Pakistan

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 6

and instantiated a long, and still ongoing, process that reproduced religious difference as

central to the project of Pakistani state- and nation-making.

15 The India-Pakistan War in 1965 also legitimated relations of Hindu othering by providing

the state with an opportunity to reiterate the criticality of Muslim unity in Pakistan and

to mark Hindus as potential threats to this unity. This short war also legitimated

President Ayub Khan’s passing of Order XXIII of 1965, The Defense of Pakistan Ordinance,

declaring India an enemy country and authorizing the confiscation of all interests of the

enemy.14 This ‘undisguised act of retaliation’, (Benkin 2009: 79) included taking

possession of property from those who were citizens of India but also citizens of

territories in which Hindus, now proclaimed as the enemy, resided, occupied, controlled,

or were captured. The conflation of India with all Hindus in undivided India justified

Ayub Khan’s passage of the Ordinance with the Enemy Property (Custody and

Registration) Order of 1965 and 1966, and the East Pakistan Enemy Property (Lands and

Buildings) Administration and Disposal Order, 1966, under Rule 182 (1) of the Defense of

Pakistan Rule. Together, both Ordinances reconfirmed in law the Hindu as other, thus

framing the national narrative in an idiom of Islam.

16 Despite revoking the state of emergency on 16 February 1969, The Defense of Pakistan

Rules relating to the control of trade with the enemy and their firms continued, as did use

of the term ‘enemy’. This continuance empowered the District Commissioners, who held

bureaucratic control in the rural areas, to implement these ordinances and rules under

the Government’s declaration of the Enemy Property, Continuance of Emergency

Provisions Ordinance, 1969 (Ordinance I of 1969), even in the absence of war (Barkat et al.

2008).

17 Shrouded in claims of national security, together these orders imposed draconian rules

aimed at Hindu landowners and those owning firms and buildings that sanctioned

property acquisition by the state (Shafi 2007, Mohsin 2004). The enemy, couched in an

idiom of state security, included all Hindus who resided in India, even if they had family

or kin in Pakistan and who, according to Hindu inheritance law, could be the recipients of

their property (Barkat et al. 1997). Thus, declaring India an enemy state meant that even

Hindus living in East Pakistan were included among those whose allegiance was suspect

and assumed to be inevitably tied to India. It led, as well, to a second major displacement,

since Hindus were now deprived of their rights to property and to its transfer, sale, and

gifting.

18 Despite these takings, Hindus continued to opt for East Pakistan as their country of

belonging, a choice that valorized its syncretic tradition, language, and the identification

of the majority of its inhabitants as Bengali rather than Muslim. Those Hindus remaining

in the East, however, challenged the leadership in the West, who feared their potential

electoral power and their progressive orientation, and viewed their decision as a threat to

national security. These challenges eventually helped catalyse the West Pakistan response

to the East Wing’s call for autonomy—the threat of Bengali nationalism and a

questionable identification with Islam, stemming, in some measure, from the haunting

success of the Language Movement and the struggle against Urdu as the national

language.

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 7

Reproducing majoritarian rule: the politics of

independence

19 Paradoxically, recognizing the syncretism that defined what was distinctive about Bengali

cultural practices provided not only a marked other for the West but also the grounds for

the secular demands that would shape the movement for an independent Bangladesh.

This claim acknowledges that, following the Indo-Pakistan war, there was a growing

demand for political and economic autonomy of the East Wing. This was especially so

following Army Chief Yahya Khan’s passing of the Enemy Property (Continuance of

Emergency Provision) Ordinance in 1969, which, by declaring martial law, annulled the

Constitution that recognized the fundamental right to ‘profess any religion’. This

militarization of the region sustained state efforts to eliminate from the East any

association with the region’s Hindu past and to control progressive elements that sought

regional autonomy. Notable here is not only Khan’s refusal to address Sheik Mujibur

Rahman’s initial demand for the autonomy of East Pakistan—and, eventually, an

independent Bangladesh—but also his ordering of military intervention to suppress the

Awami League, as well as to curtail political mobilization. Rather than negotiate for

autonomy, the military entered East Pakistan, targeting Hindus and progressive forces in

one of the most brutal genocides in world history.

20 Hindu faculty at Dhaka University were among the first assassinated by the Pakistan

army during Operation Searchlight on 26 March 1971, as they, and other progressive

faculty, were assumed to have instigated the movement for autonomy. The military was

particularly hostile to Hindus—who, they believed, ‘played a malevolent role in East

Bengal’,—given their assumption that Hindus were ‘natural’ inhabitants of India and,

thus, were intent on either exterminating or driving them out of the country (Beachler

2007: 467). As van Schendel (2009: 162) wrote:

In these first gruesome hours of army terror, people all over Dhaka were picked up

from their homes and ‘dispatched to Bangladesh’—the army’s euphemism for

summary execution. There were verbal and later written orders to shoot Hindu

citizens. Dhaka’s old artisan neighborhood of Shankharipotti […] was attacked and

Hindu inhabitants murdered. Many prominent Hindus were sought out and put to

death.

21 US Senator Edward Kennedy likewise remarked about the targeting of Hindus during the

independence war:

Field reports to the US Government, countless eye-witnesses, journalistic accounts,

reports of international agencies […] document the reign of terror which grips East

Bengal (East Pakistan). Hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community

who have been robbed of their lands and shops, systematically slaughtered, and in

some cases, painted with yellow patches marked ‘H’. All of this has been officially

sanctioned, ordered and implemented under martial law from Islamabad (Lintner

2003: 2).

22 The result of this reign of terror was another mass migration of Hindu East Pakistanis to

India, signaling the complex identifications shaping the lives of those who chose to

remain in the country.15

23 This targeting of Hindus institutionalized the right to violence that can turn neighbors

into enemies and people to be feared for the threat they pose to conceptions of national

belonging. It also can destroy community and forms of sociality that make such behavior

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 8

against kin or neighbor possible. Paradoxically, this construction of the Hindu as other

became most evident when, on 10 April 1971, after declaring liberation on 26 March 1971

following a nine month bloody struggle, the provisional government, under the Vice

President and Acting President Syed Nazrul Islam, ordered that all laws in force on 25

March would continue. This included the Laws of Continuance Enforcement Order, 1971,

which retained those same laws regarding enemy property that were promulgated prior

to Independence. The following year, on 4 November 1972, the Bangladesh Parliament

adopted the independence principles of nationalism, socialism, democracy, and

secularism, but also The Bangladesh (Vesting of Property and Assets) Order which

recognized the new government as vested with ‘enemy’ properties seized since the 1965

War and stipulated that its provisions shall not be subjected to judicial review.

Consequently, land owned by Hindus, their legal heirs, or family members currently

residing on the property, was subject to dispossession, including by force.16 The Order

also led to illegal appropriations as government officials were given the power to

arbitrarily designate land as enemy property, thus undermining the ownership rights of

Hindus as citizens, as well as their rights to state protection.

24 Later, in 1975, and following the murder of Sheik Mujibir Rahman, popularly known as

Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengal) and the founding father of Bangladesh, religious and

ethnic identities were again challenged, especially by Bangladeshi nationalism which

accompanied the ascendency of the military regimes of Zia Rahman (1975–1981) and

Hossain Mohammad Ershad (1981–1990). Bangladeshi nationalism was a project aimed at

purging Hindu idioms from Bengali national identification in efforts to distance the

country’s cultural landscape from both the Awami League and (Hindu) West Bengal.

Crucially, it answered the national identity question by reframing ‘we are Bengali first

and Muslim second’ as ‘we are Muslims first and Bengalis second’, recasting national

belonging from an ethnic identification with Hindu West Bengal, India, to a religious

identification with Pakistan. Unsurprisingly, this shift also recognized Islamist interests

and political party participation, particularly of the Jaamat-i-Islami, thereby

compromising the secular principle of independence. The change led first, in 1977, to the

deletion from the Constitution of secularism as a state principle and, second, in 1988, to

the declaration of Islam as the state religion. At play during the shift from Bengali to

Bangladeshi nationalism was a rhetoric that emphasized the specter of caste Hindu

domination, the tensions of partition, and the communal violence that shaped political

rule in what was characterized as Hindu India (Chowdhury 2009).

25 The reproduction of Hindus as other was thus further entrenched by practices of cultural

and social enclosure, including when, under military rule, Muslim prayer before public

meetings and on television, was first promoted and then required; and again, in 1979,

when Zia Rahman added ‘Bismillah ar-Rahman ar-Rahim’ before the Preamble of the

Constitution and replaced the words ‘historic struggle for national liberation’ with

‘historic war for national independence’. This latter move signals the shift from a

liberation struggle to a nationalist project to claim sovereignty and safeguard Bangladesh

from her foreign enemy, India. These changes reflected Zia’s effort to elide connections

between the liberation movement and those of the 1952 Language Movement that

recognized struggles for a shared Bengali culture against an Urdu dominated Islamic one.

To accomplish this shift, he introduced ‘Islamiyat’ (Islamic religious study) as compulsory

from Class I-VIII, giving minority students the option of taking similar religious courses

(Samad 1998) and requiring school instruction in vernacular Bangla, including at the

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 9

university, as a way to encourage identification with Islam and Pakistan (Guhathakurta

2002). Critical to his state-making project was Zia’s distinction between Bengali and

Bangladeshi identity, which not only marked Hindu Bengalis and Bangladeshis as

dissimilar, but also gave credence to the sense that all Hindus, those in India as well as

Hindu Bengali citizens of Bangladesh, were always potential enemies of the state. Such

practices reignited insecurity and fear in the everyday lives of minority populations,

while also encouraging the temporary and permanent migration of Hindus to India.

Contingencies of ownership and the politics of

difference under democratic rule

26 Expectations changed with the public uprising against the autocratic regime of General

Ershad that led, in 1991, to the first democratic elections that brought Khaleda Zia and

the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) to power. Their alliance with the Jamaat-i-Islami

made the victory of the BNP possible and raised, again, the specter of Islam as a defining

feature of the ruling project. Ali Riaz (2003) suggests that the turn to Jamaat occurred

precisely because the two leading political parties failed to secure hegemonic rule and,

thus, allied with Jamaat simply for electoral expediency. Claims of expediency

notwithstanding, such alliances have long-term consequences that build on Jamaat’s

institutionalization during military rule and continue as part of a process of Islamization

that threatens the security of minority populations. Meghna Guhathakurta (2012)

acknowledges this threat as contributing to a growing sense of alienation, while Abul

Barkat and his coauthors (2008) show that it led to ongoing Hindu forced, or ‘last resort’,

migration.

27 Sheikh Hasina’s ascendency to power in 1996 led to passage of the Restoration of Vested

Property Act, 2001 (Act No. 16 of 2001) which stipulated that previously confiscated lands

should be returned to their original Hindu owners. However, the Act referred only to

properties vested prior to February 1969, while ignoring properties confiscated

afterwards that were likely in the hands of government officials or miscreants, and often

confiscated illegally. It also excluded land that was no longer in government hands or

currently used by or leased to an authorized person. Thus, despite this initial sense of

promise, these and other restrictions of the Act failed to offer claimants access to the

return of land that they or their families owned.

28 Khaleda Zia’s return to power further diluted the Restoration Act by removing time limits

on the government’s responsibility to enforce the return of property. Emphasizing the

role of political power in illegal land appropriations, Barkat (2000) calculates that 44.2

percent of vested property was appropriated by members of the AL, 31.7 percent by the

BNP, 5.8 percent by Ershad’s Jatiya Party, 4.8 percent by Jamaat-e-Islami, and 13.5 percent

by others. And, under BNP rule (2001 to 2006) an additional eight percent of the incidents

of land encroachment were added to the more than 2 million acres of land, or 45 percent

of all land owned by Hindus taken before this period (ASK 2006).

29 Also consequential for the social and economic security of Bangladeshi Hindus are

communal relations in India. For example, soon after the elections, the country witnessed

the 1992 destruction of the Babri Masjid by Hindu fundamentalists that led to the death of

more than 2000 people, not only in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, but also in a number of cities

across the country. The Gujarat riots that followed a decade later, in 2002, resulted in the

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 10

death of more than 2000 Muslims and displaced hundreds more. In each case, there were

retaliatory attacks on Hindu people and property in Bangladesh with little government

intervention to stop them, which further deprived Hindus of a sense of social security and

access to adjudication.

30 The result of such failures of government has been a growing sense of alienation among

those against whom violence can be justified by routine practices of rule that reflexively

render them different, unworthy, and devalued. Such practices recall women who met

the wrath of witch-hunters as they resisted usurpations in their struggle for more

egalitarian gender relations, leading to, among other acts of violence, ‘the murder of the

accused and the confiscation of their properties’ (Federici 2008: 21). Reproducing such

difference, in other words, is a process of ongoing social enclosure—othering, devaluation,

and exclusion—that entail public discourse that constructs the other as enemy and makes

subjects of presumed citizens. Critical to this account are the claims that such

appropriations are carried out in the name of protecting the Muslim majority and

securing their rights as citizens of the state.

31 Such practices build on demonizing narratives against Hindus that once initiated gain

currency as they circulate in the press, in literature, and in memoirs, as well as in private

discussion and rumor within families and communities (Guhathakurta 2012). They are

materialized in state policies that construct difference and justify differential state action

that gradually alienates, marginalizes, and discriminates against Hindus. But,

importantly, they include reluctance amongst Hindus to adjudicate or claim ownership

rights because they fear retribution. Further, even among those with the social networks

and financial resources to fight for control of their property, fear, angst, and disrespect

shape processes of adjudication. Arild Ruud (1996) suggests that such practices can lead

personnel, acting on behalf of state institutions, to refuse or fail to safeguard members of

the Hindu community by ignoring illegal practices, including violence committed against

them, or to defer responsibility when requests for fairness or recompense have been

made. Benkin (2009: 80) suggests these actions can lead to legalized oppression, even

ethnic cleansing. Another way to make the same point, indicating the recursive character

of policy reforms and subjection, is that the Hindu minority community in majoritarian

Bangladesh is deemed to require destruction of their power through ‘extermination’, an

experience that also characterizes relations in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (Federici 2004:

63, Introduction to this volume).

32 Importantly, these relations of social enclosure and, in the extreme, extermination, both

accompany and justify forms of expropriation that recast social life, turning peasants into

proletarians or worse, since today, processes of land appropriation go hand-in-hand with

the withdrawal of state support for the rural poor. For all Hindus, but particularly the

land-poor, this leads to lives that are increasingly precarious, as usurpation through legal

and contractual transgressions are secured, as a matter of state, in a context that includes

the privatization of public resources and market-driven solutions to social issues.

Differential access to new resources can be legitimated on the basis of Hindu difference/

enmity and claimed in the name of national security. Finally, in struggles over land claims

and illegal expropriations by government personnel, aligning the management of vested

property claims with primarily rural and town administrators turns a blind eye to the

state’s complicity with elite expropriators in ways that further limit the possibilities for

redress.

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 11

The current conjuncture: amending the VPA

33 The return to power of the AL, following the Caretaker government (2006–2008), again led

to rising expectations among those seeking redress for the VPA. On 6 November 2008, the

High Court division of the Supreme Court challenged the Enemy Property (Continuance of

Emergency Provision) (Repeal) Act of 1974, arguing that it contradicts the fundamental

rights and charter of the Bangladesh Declaration of Independence. The Government

followed with the Vested Property Repeal (Amendment) Act, 2011, which was amended

again in 2012 and 2013.17 Each of these amended Acts raised expectations among

Bangladeshi Hindu citizens, even as pre-election violence in 2013, including demolition of

Hindu temples and failure of the government to protect those targeted, dashed their

hopes for redress.

34 But this time, frustration with the failure of the AL to implement the return of seized

property led to a critical public discussion organized by nine rights organizations and

citizen groups18 which argued that the amended Vested Property Repeal (Amendment)

Act of 2013 ‘is part of a plot by corrupt land officials to prolong the return of “vested

property”’.19Under current law, not only do ‘corrupt officials’ illegally enlist land as

vested property, but they also publish gazettes on newly identified lands that create

opportunities for the continual harassment of Hindu landowners by district officers.

Moreover, Subrata Chowdhury of Arpito Sampatti Ain Protirodh Andolon (ASAPA)

suggests that the move to allow the publication of supplementary gazettes, expand the

list of properties, and extend ‘the timeline for publishing the supplementary gazettes is

an attempt to prolong the crisis of vested property laws in a new form’ (Jahangir 2013).

35 Identifying the complicity of ‘corrupt officials’ was a central concern. As Kazal Debnath of

the Bangladesh Hindu Buddha Christian Oikya Parishad (HBCOP) makes evident, each of

the 16 or 17 documents required under the law to file a complaint entail bribes to

officials. Barkat et al. (2008) similarly argued in reference to an earlier period that ‘the

notorious ordinance of 1965 began the vesting of property of religious minorities who

were temporarily forced out of the country, but corrupt land officials benefit from

refusing to enforce the Supreme Court verdict of 23 March 1974 that declared the Enemy

Property Order 1965 dead’ (Guhathakurta 2002: 82). The new amendment similarly

advantages land officials who have been involved in vesting for a long period, allowing

them 300 more days to list vested properties while offering the plaintiffs only 30 days to

file their complaints (Jahangir 2013).

36 Sadly, but unsurprisingly, the amended Act has yet to be implemented, further

contributing to Hindu insecurity and affecting forms of adaptation and avoidance,

including everyday linguistic choices that people make when in public. As Guhathakurta

explains, ‘Muslim terminology [is often chosen] […] in order to disguise their (Hindu)

difference of identity in public; either to cause less hassle or simply to avoid eyebrows

being raised’ (2002: 82). Such relations of sociality are constitutive of the vulnerabilities of

those who are likely to fall prey to potential land expropriation and the poor who fear

reprisal should they complain or challenge the behavior of Muslim elites or government

officials.

37 Middle class Hindus express similar feelings of vulnerability, although they are more

likely to assert their rights and use legal resources to secure family property. As one key

middle class informant lamented, ‘I have the resources and the connections to fight for

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 12

my property, but it takes a lot of money and connections to do so… we always have to

worry… we don’t often win’ (Feldman 2014). Thus, despite their status as members of the

middle class, living with the continual threat of land grabbing means that many Hindus

choose not to seek redress:

This is the story of 23 acres of land in Faridpur District: The original owners went to

India during the Indo-Pak War, the land was recorded as vested property but was

actually taken by three men, Khaleque, Rashid, and Hakim. Khaleque ‘prepared’

false documents for part of the land, ignoring the fact that vested property cannot

be sold, and subsequently sold a portion of it to Muktar and Ismail. Ismail sold ‘his’

land to Hafizur. Yet, what is also clear is that a nephew of the original owner still

resides in the area, a 50-year-old village physician (Feldman 2014).

38 While this window on the social life of land ownership illuminates the violence and illegal

transfers associated with the VPA, it fails to address what these processes mean for Hindu

owners. In this case, Mr. Das does not have living relatives in the area; nor did his uncle

formally transfer the land to him or his family. However, any legal successor to the real

owner is eligible to petition for the property if they can produce a legal succession

certificate. Yet, as a man of some means, he has not petitioned for his land and makes

plain why he has not done so: ‘The court may issue an order in favour of me, but if I

would like to take possession, they (those currently on the land) will kill me. Moreover, I

[…] am in doubt whether I would be able to secure my own properties from the grabbers’

(Feldman 2013). This and numerous similar stories reveal the costs of being a Bangladeshi

Hindu, particularly regarding everyday social behavior and access to resources and

rights.

39 In other instances, a person’s village status changes when their land is vested. To

summarize a finding from Barkat et al. (2008: 133–37): As a school teacher, Mr. Debnath

was a respected member of the local School Managing Committee, the local Puja

Committee, the shalish (local village court), and regularly contributed to community

ceremonies. However, his financial security deteriorated when he brought a legal suit

against Abdul Aziz and Kalipad Ghoshal, who had grabbed his agricultural land. He first

discovered that someone had claimed his property when he visited the tehsil office to pay

his taxes and was told the land was recorded in the name of two others. After working

with the Deputy Commissioner, he was informed that the title would be reissued in his

name, but, when he went to harvest his crop, a violent exchange ensued with Aziz’s gang.

A shalish followed only to confirm that the land belonged to Aziz, a prominent BNP

businessman in the community.

40 In addition to revealing the Bangladeshi Hindu’s own cautious behavior and routine

disrespect from others, Barkat et al. (2008) show how usurpers both threaten Hindu

landowners with eviction and harass young girls (‘eve-teasing’) in ways that lead families

to stop sending girls to school simply to avoid harassment. Others note that in some

communities, every male has been beaten at least once. But, as community members

argue, most disturbing is the lack of response to such acts of violence by authorities who

implicitly condone continued attacks and harassment. As Shuruz (2004) similarly notes,

the desperation of a Gopalpur villager is evident as she recounts that the brutality of

crimes committed this year was greater than the brutality committed by this same group

in last year’s attack: ‘In the past, women were spared, but now some are even forcefully

disrobed… Yet no officer from the police station or administration […] showed up to

‘assure our security’, except after the news of it hit the press that the apathetic

administration received a stirring.’ Another villager recalls how, after the demolition of

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 13

the Babri Mosque in India, a different cremation ground was usurped by this same group:

‘It is a vicious, manmade cycle.’ These experiences highlight the reproduction of senses of

insecurity and fear in a context where perpetrators of local, community-based tensions,

threats, and outbursts against Hindus do not face government redress and, in some

instances, even have their actions condoned by state authorities.

41 In a final example, Mr. Das, a Hindu and member of the Land Ministry who accompanied

me on a drive to a peri-urban area of Dhaka, made quite evident that the region, once the

vegetable basket of the city, was now a major site for industrial and export production.

On the drive, I queried Mr. Das about the dramatic transformation of this once rural

countryside. But, he met every effort I made to casually discuss this dramatic change in

the landscape with a variant of ‘I cannot really discuss land matters since they are a

matter of national security.’ And when, over tea, and in the company of an Upazilla

officer, I shared my experience of having been in the area 15 years earlier, and now was

surprized at how quickly Bangladesh was being urbanized, Mr. Das quickly intervened,

making it clear that his junior officer was not permitted to comment. Even when talking

about the recent amendments to the Vested Property Act, and whether and how it was

affecting his office—more work and a backlog of cases—Mr. Das quickly cut the

conversation short, saying that they had no information, since the gazetteers listing

vested properties had yet to be released. In sharing my experience with other

researchers, policy makers, and NGO members, my interpretation of the lack of

transparency and obfuscation on the part of government representatives was confirmed

(Feldman 2013).

42 As land seizures continue, including the taking of buildings located in provincial towns

where they are increasingly valued, even those with resources and connections to top-

level administrators may be unable to ward off property grabs. Under these conditions,

and without holding accountable those who use their power and are complicit in land

grabbing, there is little guarantee that Hindu owners will ever be able to secure their

rights to property and full citizenship. What these examples also show is that

dispossession depends on the expropriation of property, the governance structures that

legitimate the practice, and the constitution of fear among those who might have legal

claims to the property. One can only wonder whether the tease of policy change, and

accompanying claims of opportunities for redress, will actually be able to deliver on the

promise to stop illegal land grabbing. And one can only wonder if patterns of othering,

engendering fear among Hindus marked as threats to national security, will also be

undermined, particularly under current regimes that claim to be, and are recognized

internationally as, democratic formations.

Conclusion

43 In this paper, I have sought to explain the loss of as much as 75 percent of religious

minority property confiscated and justified under the VPA (Choudhury 2009). Not only

did the Pakistani state claim rights to Hindu land for government and public use prior to

Independence, but the most concentrated appropriations, often taken illegally, occurred

immediately following independence during the first AL and BNP governments (1972–

1975; 1976–1980) (Choudhury 2009). These expropriations were followed by a period of

unregulated land grabs during continued military rule (1980–1990) and, again, under the

democratically elected formations of the Bangladesh National Party (1991–1996; 2006–

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 14

2008) and the Awami League (1996–2000; 2009–2013; 2014–). Despite these appropriations,

aspirations for Hindu recognition, under Sheik Hasina and the AL, and fear of Hindu

hostility under Khaleda Zia and the BNP, characterize the experiences of Hindu citizens.

The fear of retribution by Hindu property owners, and the class and regional dispersion

of the Hindu population have contributed to limited resistance but also to a sense that

survival may sometimes depend on hiding one’s sense of self. In Arjun Appadurai’s words,

identifications can become

unstable, indeterminate, and socially volatile, [and] a means of satisfying one’s

sense of one’s categorical self. […] Uncertainty about identification and violence can

lead to actions, reactions, complicities, and anticipations that multiply the pre-

existing uncertainty about labels. Together, these forms of uncertainty call for the

worst kind of certainty: dead certainty (Appadurai 1998: 922–23).

44 I have argued that focusing on the Vested Property Act and its various iterations offers an

optic through which to explain relations of dispossession and subjection that

simultaneously constitute the logic and the institutionalization of the Act. In so doing, I

offer four critical interventions to contemporary discussions of land grabbing. First is the

need to explore further everyday forms of expropriation as constitutive of contemporary

neoliberal practice. By exploring neoliberal practice, I emphasize the continued

valorization of accumulation for some, on the one hand, and wage labour, rather than

subsistence production, on the other. To realize processes of accumulation, I lend support

to what Gardner and Gerharz (Introduction to this volume) refer to as ‘crony capitalism’,

a form of hyper development enabled by the state’s neoliberal ‘open door’ policies.

Second, I argue that the material and structural aspects of land grabbing should be

understood as mutually constitutive processes that depend on both cultural enclosures

and relations of subjection. This means that cultural enclosures and relations of

subjection are not merely effects of legal and illegal land grabs; rather, they depend on

such relations of rule for their enactment.

45 To understand the institutionalization of land grabbing, in other words, requires

attention to the ways in which relations of rule minoritize, subjugate, and create fear

among selected members of a social formation and how such fear is deployed to

legitimize their subjugation. In some instances, they enable removal, extermination,

looting, burning, eve-teasing, and other forms of violence, or what Appadurai (1998)

perceptively reveals in his discussion as ethnic violence in the era of globalization. The

third point, then, is that while all vulnerable people are potential targets of land

grabbing, only the construction of particular others from whom such grabs can be

legitimated will secure popular support and not spark general unrest. I have also

emphasized the criticality of historically specific relations of dispossession as the basis

for understanding land appropriations and the need to tether forms of rule to the

expropriation of people and communities from their property as well as economic and

social security. Finally, in showcasing these points I have emphasized the criticality of

viewing land grabs as an ongoing process that is reproduced under changing

circumstances, where tensions of property ownership are not claimed once and for all,

but rather, are constituted through continual, if changing, processes of rule and the

creation of difference.

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 15

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abrams, Philip (1988) ‘Notes on the Difficulty of Studying the State’, Journal of Historical Sociology,

1(1), pp. 58–89.

Adnan, Shapan (2013) ‘Land Grabs and Primitive Accumulation in Deltaic Bangladesh:

Interactions between Neoliberal Globalization, State Interventions, Power Relations, and Peasant

Resistance’, Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(1), pp. 87–128.

Ain o Salish, Kendra (2006) ‘Rights of Religious Minorities’, Bangladesh Policy Brief, Fall, URL:

http://www.askbd.org/Hr06/Minorities.htm.

Appadurai, Arjun (1996) Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

Appadurai, Arjun (1998) ‘Dead Certainty: Ethnic Violence in the Era of Globalization’, Development

and Change, 29, pp. 905–25.

Barkat, Abul (2000) An Inquiry into Causes and Consequences of Deprivation of Hindu Minorities in

Bangladesh through the Vested Property Act: Framework for a Realistic Solution, Dhaka, Bangladesh:

PRIP Trust.

Barkat, Abul; Zaman, Shafique uz; Khan, Md. Shahnewaz; Poddar, Avijit; Hoque, Saiful; Uddin, M.

Taher (2008) Deprivation of Hindu Minority in Bangladesh: Living with Vested Property, Dhaka: Pathak

Shamabesh.

Barkat, Abul; Zaman, Shafique uz; Rahman, Azizur; Poddar, Avijit (1997) Political Economy of the

Vested Property Act in Rural Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh: Association for Land Reform and

Development.

Beachler, Donald (2007) ‘The Politics of Genocide Scholarship: The Case of Bangladesh’, Patterns of

Prejudice, 41(5), pp. 467–92.

Benkin, Richard L. (2009) ‘Ethnic Cleansing in Bangladesh’, Himalayan and Central Asian Studies, 13

(4), pp. 79–94.

Bonefeld, Werner (2001) ‘The Permanence of Primitive Accumulation: Commodity Fetishism and

Social Constitution’, The Commoner, September.

Charusheela, S. (2011) ‘Response: History, Historiography, and Communal Subjectivity’,

Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society, 23(3), pp. 322–27.

Choudhury, Salah Uddin Shoaib (2009) ‘Vested Property Act Being Scrapped in Bangladesh’,

September 10, URL: http://www.weeklyblitz.net/273/vested-property-act-being-scrapped-in-

bangladesh [accessed 31 October 2010].

Chowdhury, Iftekhar Uddin (2009) ‘Caste Based Discrimination in South Asia: A Study of

Bangladesh’, Working Paper Series, Volume III, No. 7, New Delhi: Indian Institute of Dalit Studies.

De Angelis, Massimo (2001) ‘Marx and Primitive Accumulation: The Continuous Character of

Capital’s “Enclosures”’, The Commoner, September.

De Angelis, Massimo (2004) ‘Separating the Doing and the Deed: Capital and the Continuous

Character of Enclosures’, Historical Materialism, 12(2), pp. 57–87.

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 16

Federici, Silvia (2004) ‘Witch-Hunting, Globalization, and Feminist Solidarity in Africa Today’,

Journal of International Women’s Studies, 10(1), pp. 21–35.

Federici, Silvia (2004) Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation, Brooklyn

(New York): Autonomedia.

Guhathakurta, Meghna (2012) ‘Amidst the Winds of Change: The Hindu Minority in Bangladesh’,

South Asian History and Culture, 3(2), pp. 288–301.

Guhathakurta, Meghna (2002) ‘Communal Politics in South Asia and the Hindus of Bangladesh’, in

Monirul Hasan & Lipi Ghosh (eds.), Religious Minorities in South Asia: Selected Essays on Post-Colonial

Situations, New Delhi: MANAK Publications Pvt. Ltd., pp. 70–87.

Hall, Derek (2013) ‘Primitive Accumulation, Accumulation by Dispossession and the Global Land

Grab’, Third World Quarterly, 34(9), pp. 1582–604.

Harvey, David (2003) The New Imperialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jahangir (2013) ‘The Bangladeshi parliament has passed a landmark bill that will enable the

return of property seized from the country’s Hindu minority: ‘Vested Property Repeal

(Amendment) Act 2013 part of plot’, BBC News, 14 June.

Jalal, Ayesha (1995) ‘Conjuring Pakistan: History as Official Imagining’, International Journal of

Middle East Studies, 27(1), pp. 73–89.

Jinnah, Mohammed Ali (2004) Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Speeches as Governor-General of

Pakistan, 1947–1948, Lahore: Sang-i-Meel Publications.

Lambert, Richard D. (1950) ‘Religion, Economics, and Violence in Bengal: Background of the

Minorities Agreement’, Middle East Journal, 4(3), pp. 307–28.

Lintner, Bertil (2003) ‘The Plights of Ethnic and Religious Minorities and the Rise of Islamic

Extremism in Bangladesh’, Asia Pacific Media Services, 2 February, URL: www.asiapacificms.com.

Marx, Karl (1983) Capital, Volume I, Chapters 26–33, London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Midnight Notes Collective (2001) ‘The New Enclosures’, The Commoner, September, URL: http://

www.commoner.org.uk/02midnight.pdf.

Mohsin, Amena (2004), ‘Religion, Politics and Security: The Case of Bangladesh’, in Satu P.

Limaye, Robert G. Wirsing & Mohan Malik (eds.), Religious Radicalism and Security in South Asia,

Hawaii: Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies. pp. 467–88.

Pertev, Rasit (2009) ‘Economics of Corruption by Democracy’, Available at Social Science Research

Network, URL: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1467900.

Riaz, Ali (2003) ‘“God Willing”: The Politics and Ideology of Islamism in Bangladesh’, Comparative

Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 23(1–2), pp. 301–20.

Ruud, Arild Engelsen (1996) ‘Contradictions and Ambivalence in the Hindu Nationalist Discourse

in West Bengal’, in Stein Tonnesson & Hans Antlov (eds.), Asian Forms of the Nation, Richmond:

Routledge Curzon, pp. 151–80.

Samad, Saleem (1998) ‘State of Minorities in Bangladesh: From Secular to Islamic Hegemony’,

URL: www.sacw.net [accessed 31 October 2010].

Schechtman, Joseph B. (1951) ‘Evacuee Property in India and Pakistan’, Pacific Affairs, 24(4),

pp. 406–13.

Shafi, Salma A. (2007) ‘Land and Tenure Security and Land Administration in Bangladesh’, Final

Report, Dhaka: LGED, UNDP & UN-Habitat Project BGD/98/006, June.

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016

The Hindu as Other: State, Law, and Land Relations in Contemporary Bangladesh 17

Shuruz, Mominul Islam (2004) ‘Caught in the Land-grabber’s Grasp’, Star Weekend Magazine, 4, 24,

December 10.

Trivedi, Rabindranath (2007) ‘The Legacy of Enemy Turned Vested Property Act in Bangladesh’,

Asian Tribune, 11, 632, 29 May.

van Schendel, Willem (2009) A History of Bangladesh, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Verdery, Katherine (1994) ‘Ethnicity, Nationalism, and State-making: Ethnic Groups and

Boundaries: Past and Future,’ in Hans Vermeulen & Cora Govers (eds.), The Anthropology of

Ethnicity: Beyond ‘Ethnic Groups and Boundaries’, Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis, pp. 33–58.

Vermeulen, Hans; Govers, Cora (eds.) (1994) The Anthropology of Ethnicity: Beyond ‘Ethnic Groups and

Boundaries’, Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis.

NOTES

1. Under the “Defense of Pakistan Rules” (DPR), the Government of Pakistan passed the Enemy

Property (Custody and Regulation) Order II of 1965 that was reconfirmed as the Enemy Property

Ordinance, 1969 after the Indo-Pakistan war. This was followed by the East Pakistan Rule 161, the

East Pakistan Enemy Property (Lands and Building) Administration and Disposal Order, which

continued after the independence of Bangladesh. While the practice remained the same, the

name formally changed under the Vested and Non-resident Property (Administration) Act (Act

XLVI) of 1974.

2. Included here is theft by private interests and the state’s failure to intervene to protect the

property rights of Hindu citizens.

3. The ‘ungodly secularists’ include the Hindu population who were especially targeted during

the war. While other groups in Bangladesh have been marginalized, particularly the Bihari and

tribal communities, it is Hindu property that is the target of the Vested Property Act and the sole

focus of this paper.