Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Greengross (2012)

Greengross (2012)

Uploaded by

Yossa PratamaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- CEPE - Printable BDSM Checklist. August 2014Document41 pagesCEPE - Printable BDSM Checklist. August 2014hollywoodbear999990% (10)

- Day 1 SolutionsDocument6 pagesDay 1 SolutionsLiz KiNo ratings yet

- The 3D Printing Handbook - Technologies, Design and ApplicationsDocument347 pagesThe 3D Printing Handbook - Technologies, Design and ApplicationsJuan Bernardo Gallardo100% (7)

- Related Literature (Study Habits/Peer Pressure)Document11 pagesRelated Literature (Study Habits/Peer Pressure)William T. Ladrera75% (12)

- Extending Non-Monogamies: T&F Proofs: Not For DistributionDocument15 pagesExtending Non-Monogamies: T&F Proofs: Not For DistributionAaron HellrungNo ratings yet

- The Effects Absent Fathers Have On Female Development and College AttendanceDocument6 pagesThe Effects Absent Fathers Have On Female Development and College AttendanceShen ZertlahNo ratings yet

- Fostering Traditional Gender Roles or Androgyny in ChildrenDocument8 pagesFostering Traditional Gender Roles or Androgyny in ChildrenMegan Van DorenNo ratings yet

- 42-Article Text-39-1-10-20190619 PDFDocument28 pages42-Article Text-39-1-10-20190619 PDFZohra Mehboob AliNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles in Animated Cartoons_ Has the Picture Changed -- Teresa L_ Thompson; Eugenia Zerbinos -- Sex Roles, #9-10, 32, Pages 651-673, 1995 May -- 10_1007_bf01544217 -- Ffd29e2d6630a2046c65d303e879f455 -- AnnDocument23 pagesGender Roles in Animated Cartoons_ Has the Picture Changed -- Teresa L_ Thompson; Eugenia Zerbinos -- Sex Roles, #9-10, 32, Pages 651-673, 1995 May -- 10_1007_bf01544217 -- Ffd29e2d6630a2046c65d303e879f455 -- Annstudyprep19No ratings yet

- Stereotypes Influence How A Person Perceive One's Self and One's Self-IdentityDocument7 pagesStereotypes Influence How A Person Perceive One's Self and One's Self-IdentityezmoulicNo ratings yet

- (2008) VernonDocument10 pages(2008) VernonDrusya ThampiNo ratings yet

- Humor Style Similarity and Difference in Friendship DyadsDocument8 pagesHumor Style Similarity and Difference in Friendship DyadsElena NuțăNo ratings yet

- Katie BrookesDocument18 pagesKatie BrookesManole Eduard MihaitaNo ratings yet

- Rubin 1984Document28 pagesRubin 1984Yến NguyễnNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Parenting Styles On Strengths of Humanity: Love, Kindness and Social Intelligence in Myanmar AdolescentsDocument11 pagesThe Effect of Parenting Styles On Strengths of Humanity: Love, Kindness and Social Intelligence in Myanmar Adolescentsতা মা ন্নাNo ratings yet

- Thesis Gender StereotypesDocument8 pagesThesis Gender Stereotypesdenisehalvorsenaurora100% (2)

- סטריאוטיפים מגדריים-חבריםDocument51 pagesסטריאוטיפים מגדריים-חבריםsabagraniNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles and SocializationDocument6 pagesGender Roles and SocializationJenny May GodallaNo ratings yet

- Summary Feb 6 ArticlesDocument7 pagesSummary Feb 6 ArticlesRaphia MallickNo ratings yet

- Thesis Gender RolesDocument6 pagesThesis Gender RolesJim Jimenez100% (2)

- Gender Studies AssignmentDocument18 pagesGender Studies AssignmentPenuganti Ruthvij kumarNo ratings yet

- What Do Children Learn About Prosocial Behavior From The Media?Document6 pagesWhat Do Children Learn About Prosocial Behavior From The Media?Heather Edey WilliamsNo ratings yet

- A StudyDocument21 pagesA StudyNgười Trong BaoNo ratings yet

- Sex Stereotyping in Children's Toy AdvertisementsDocument14 pagesSex Stereotyping in Children's Toy AdvertisementsHanna GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Regarding: InvestigationDocument14 pagesRegarding: InvestigationJosé Augusto RentoNo ratings yet

- Modefying GenderDocument8 pagesModefying Genderwaleedms068467No ratings yet

- Santos Et Al-2017-Frontiers in PsychologyDocument9 pagesSantos Et Al-2017-Frontiers in PsychologyLiana Maria DrileaNo ratings yet

- Bullying and Victimization - Cause For Concern For Both Families and SchoolsDocument21 pagesBullying and Victimization - Cause For Concern For Both Families and SchoolsRosalinda RizzoNo ratings yet

- You Dippy TwatDocument24 pagesYou Dippy Twatjas3113No ratings yet

- Children With Absent Fathers Author(s) : Mary Margaret Thomes Source: Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Feb., 1968), Pp. 89-96 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 12/02/2014 00:12Document9 pagesChildren With Absent Fathers Author(s) : Mary Margaret Thomes Source: Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Feb., 1968), Pp. 89-96 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 12/02/2014 00:12Yuhao ChenNo ratings yet

- Parenting Styles and Self-Esteem, LucyDocument35 pagesParenting Styles and Self-Esteem, LucyMariam JintcharadzeNo ratings yet

- Update: KPWKPDocument11 pagesUpdate: KPWKPWilliam T. LadreraNo ratings yet

- T3week9 - Commonlit - Bullying-In-Early-Adolescence - StudentDocument8 pagesT3week9 - Commonlit - Bullying-In-Early-Adolescence - StudentJoshua Williams100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography - EditedDocument13 pagesAnnotated Bibliography - EditedMoses WathikaNo ratings yet

- Soc Psych Research 5Document7 pagesSoc Psych Research 5OSABEL GILLIANNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory and Child AbuseDocument7 pagesAttachment Theory and Child AbuseAlan Challoner100% (3)

- Grandparenting and Its Relationship To ParentingDocument30 pagesGrandparenting and Its Relationship To ParentingElsa PaulinaNo ratings yet

- Peer Relations and Later Personal AdjustDocument33 pagesPeer Relations and Later Personal AdjustPatricia TanaseNo ratings yet

- Masculinity and FemininityDocument6 pagesMasculinity and FemininitymuskanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0160252716300553 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0160252716300553 MainDiego Alejandro ZambranoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.141 On Thu, 06 Jan 2022 13:08:48 UTCDocument10 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.141 On Thu, 06 Jan 2022 13:08:48 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- Family Deficit ModelDocument11 pagesFamily Deficit ModelApril Joy Andres MadriagaNo ratings yet

- Sex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case StudyDocument8 pagesSex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case Studyapi-99042879No ratings yet

- Controversial Yet CompellingDocument15 pagesControversial Yet Compellingapi-495066746No ratings yet

- Hafen Et Al 2011 Homophily in Stable and Unstable Adolescent FriendshipsDocument6 pagesHafen Et Al 2011 Homophily in Stable and Unstable Adolescent FriendshipsJohn AnagnostouNo ratings yet

- Fathers GaysDocument10 pagesFathers GaysKevin Arditti VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- IPA Fathers and Daughters EDDocument16 pagesIPA Fathers and Daughters EDMaria CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Treatment of Deviant Sex-Role Behaviors in A Male ChildDocument18 pagesBehavioral Treatment of Deviant Sex-Role Behaviors in A Male ChildGabriel CandidoNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-312534222No ratings yet

- The Role of The FatherDocument2 pagesThe Role of The FatherTrish LauNo ratings yet

- Child Development - 2008 - Bolger - Peer Relationships and Self Esteem Among Children Who Have Been MaltreatedDocument27 pagesChild Development - 2008 - Bolger - Peer Relationships and Self Esteem Among Children Who Have Been MaltreatedMădălina MarincaşNo ratings yet

- Identity Confusion, Bisexuality, and Flight From The MotherDocument14 pagesIdentity Confusion, Bisexuality, and Flight From The Mothermgcm8No ratings yet

- Effects of Dysfunctional FamiliesDocument10 pagesEffects of Dysfunctional FamiliesemeraldNo ratings yet

- Jackson - 2006 - Wild Girls An Exploration of Ladette Cultures in Secondary SchoolsDocument24 pagesJackson - 2006 - Wild Girls An Exploration of Ladette Cultures in Secondary SchoolsAitanaNo ratings yet

- Cook, P.WDocument182 pagesCook, P.WManole Eduard MihaitaNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotypes and RolesDocument29 pagesGender Stereotypes and Rolesakhilav.mphilNo ratings yet

- Gender StereotypeDocument3 pagesGender StereotypeFreddie Bong Salvar PalaadNo ratings yet

- Child Rearing PracticesDocument8 pagesChild Rearing PracticesJessica Chin-loyNo ratings yet

- The Assessment of Elaborated Role-Play in Young Children: Invisible Friends, Personified Objects, and Pretend IdentitiesDocument19 pagesThe Assessment of Elaborated Role-Play in Young Children: Invisible Friends, Personified Objects, and Pretend IdentitiesGloria StahlNo ratings yet

- Gender Early SocializationDocument34 pagesGender Early SocializationYzelle Mae SaUmatNo ratings yet

- C o M M I T M e N T and Rival Attractiveness: Their Effects On Male and Female Reactions To Jealousy-Arousing SituationsDocument18 pagesC o M M I T M e N T and Rival Attractiveness: Their Effects On Male and Female Reactions To Jealousy-Arousing SituationsAlina Maria Burete-HeraNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Parental Conflict and Infidelity 1Document11 pagesRunning Head: Parental Conflict and Infidelity 1Angelica NicholeNo ratings yet

- 1.socio Economic Determinants of HealthDocument64 pages1.socio Economic Determinants of HealthdenekeNo ratings yet

- Maerskgroup Evaluatingstrategic TalentmanagementinitiativesDocument22 pagesMaerskgroup Evaluatingstrategic TalentmanagementinitiativesSameer FaisalNo ratings yet

- UserGuide - 510 - 570 - 653 PDFDocument25 pagesUserGuide - 510 - 570 - 653 PDFMurugananthamParamasivamNo ratings yet

- 1b Reading Output 2Document1 page1b Reading Output 2Elisha Maurelle AncogNo ratings yet

- Carter Procession Closure MapDocument1 pageCarter Procession Closure Mapcookiespiffey21No ratings yet

- 15 Win1 Midas-Xr New Brand enDocument18 pages15 Win1 Midas-Xr New Brand encristiNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution: How It Effect Victorian Literature in A Progressive or Adverse WayDocument2 pagesIndustrial Revolution: How It Effect Victorian Literature in A Progressive or Adverse WaydjdmdnNo ratings yet

- Photo Essay PDFDocument2 pagesPhoto Essay PDFMartha Glorie Manalo WallisNo ratings yet

- Office of The Punong Barangay Barangay Certification of AcceptanceDocument1 pageOffice of The Punong Barangay Barangay Certification of AcceptanceMah Jane DivinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - The Subject and Content of ArtDocument5 pagesChapter 3 - The Subject and Content of ArtJo Grace PazNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Philippine National Philippine National Philippine National Standard Standard Standard StandardDocument14 pagesPhilippine National Philippine National Philippine National Philippine National Standard Standard Standard StandardBernard Karlo BuduanNo ratings yet

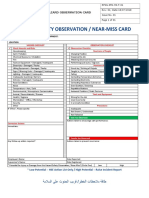

- RPSG-IMS-HS-F - 01 - Hazard Observation CardDocument2 pagesRPSG-IMS-HS-F - 01 - Hazard Observation CardRocky BisNo ratings yet

- A Study in Satin I by TiggerDocument120 pagesA Study in Satin I by TiggerCereal69No ratings yet

- Mutiple Choice Question For Satellite CommunicationDocument4 pagesMutiple Choice Question For Satellite CommunicationRaja Pirian67% (3)

- Football g.9 s.2Document51 pagesFootball g.9 s.2apNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Full ExercisesDocument6 pagesSimple Past Full Exercisespablo1130No ratings yet

- Verge PH Swot AnalysisDocument3 pagesVerge PH Swot AnalysisPamela ApacibleNo ratings yet

- Easy Add-On Projects For Spectrum Zx81 and AceDocument189 pagesEasy Add-On Projects For Spectrum Zx81 and AceArkinuxNo ratings yet

- PeriodontitisDocument14 pagesPeriodontitisDanni MontielNo ratings yet

- Answer Scheme Test 1 MechanicsDocument10 pagesAnswer Scheme Test 1 MechanicsJayashiryMorganNo ratings yet

- Read Aloud Firefighters A To ZDocument3 pagesRead Aloud Firefighters A To Zapi-252331501No ratings yet

- Gardenia PlantsDocument6 pagesGardenia PlantsyayayayasNo ratings yet

- Mushaf Qiraat Hamzah - (Khalaf) PDF Latin SCRDocument26 pagesMushaf Qiraat Hamzah - (Khalaf) PDF Latin SCRujair ahmedNo ratings yet

- WRITING NewDocument21 pagesWRITING Newtini cushingNo ratings yet

- Operazione DoMS IITR IntroDocument1 pageOperazione DoMS IITR IntroSaransh MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Knowledge L3/E Comprehension L4/D Application L5/C Analysis L6/B Synthesis L7/A Evaluation L8/ADocument2 pagesKnowledge L3/E Comprehension L4/D Application L5/C Analysis L6/B Synthesis L7/A Evaluation L8/AWaltWritmanNo ratings yet

- Comparative Adjectives/advervbs, Past Tense PassiveDocument2 pagesComparative Adjectives/advervbs, Past Tense PassiveGintarė Staugaitytė-FedianinaNo ratings yet

Greengross (2012)

Greengross (2012)

Uploaded by

Yossa PratamaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Greengross (2012)

Greengross (2012)

Uploaded by

Yossa PratamaCopyright:

Available Formats

DOI 10.

1515/humor-2012-0026 Humor 2012; 25(4): 491 – 505

Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

Childhood experiences of professional

comedians: Peer and parent relationships

and humor use

Abstract: This study examines a commonly held belief, left over from psychoana-

lytic theories of humor as a coping mechanism, that relationships with parents

strongly influence comedians’ temperaments and career choices. Thirty one pro-

fessional stand-up comedians and 400 students completed the Parental Bonding

Instrument (PBI), which concerns recollected parental care and protectiveness,

and a new self-report questionnaire that measures popularity and humor use

among peers during adolescence. Results show that comedians’ parents did not

differ from students’ parents in care or protectiveness, and comedians did not dif-

fer from students in adolescent popularity, but comedians did use more humor

among adolescent peers (were more likely to be class clowns, make fun of others,

laugh at themselves, and be the butt of jokes). The results suggest that stand-up

comedians do not differ much from ordinary college students in their parental or

adolescence peer relationships.

Keywords: humor, comedians, stand-up comedy, parental bonding, development

Gil Greengross: Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico, MSC01-1040,

Albuquerque, NM 87131, United States. E-mail: humorology@gmail.com

Rod A. Martin: Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario,

Canada, N6A 5C2. E-mail: ramartin@uwo.ca

Geoffrey Miller: Department of Psychology, MSC03-2220, 1 University of New Mexico,

Albuquerque, NM 87131. E-mail: gfmiller@unm.edu

1 Introduction

There is a widely held belief that professional humorists, such as comedians and

clowns, are sad or depressed, which has received partial empirical support in

previous research (Janus 1975; Janus et al. 1978). The reasons for this alleged

glumness vary, but many think that its roots have to do with an unhappy child-

hood or troubled relationships with parents. According to this view, comedians’

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

492 Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

performances on stage serve as a coping mechanism, enabling them to escape

from their daily troubles (Janus 1975, Janus et al. 1978).

Early research showed that comedians are likely to come from a low socioeco-

nomic stratum (Fisher and Fisher 1981, Janus 1975, Janus et al. 1978). Approxi-

mately 80–85% of comedians in two separate studies, one with 55 nationally

known comedians (51 males), and another with 14 female comedians, came from

low socioeconomic homes (Janus 1975, Janus et al. 1978). The harsh conditions at

home may explain why comedians went on to pursue their career.

In a study of 43 comedians (35 males, 8 females, 15 of them clowns), Fisher

and Fisher (1981) found that, compared to a control group of professional actors

and other entertainers, comedians were more preoccupied with themes of

good and evil in their responses to interviews and projective tests. The authors of

the study attributed this finding to the fact that the parents of future comedians

placed much responsibility on their shoulders early in childhood, requiring them

to take on an adult role at an early age. They had to take care not only of them-

selves, but also of their siblings, and many of them worked as teens to support

their parents. According to Fisher and Fisher, these untimely demands and heavy

expectations put pressure on the comedians while growing up and drove them to

seek approval, hence trying to be as “good” as their parents wanted them to be.

Falling short of parents’ expectations produced different responses from their

parents. Fathers usually were disappointed that the comedians did not reach

their high expectations; thus the comedians felt they were “bad” from their

fathers’ perspective. Many of the comedians’ mothers expected them to fail, just

waiting for this to happen. Fisher and Fisher proposed that one of the main rea-

sons why these comedians pursued a comic career was to prove that they are not

bad, and they are doing “good”.

Compared to the actors, Fisher and Fisher (1981) observed that comedians

typically described their fathers in much more positive terms, such as “good”,

“nice”, and “respected”. On the other hand, they describe their mothers as being

rule enforcers, disciplinarians, punishers, and aggressive critics. Many comedians

acknowledged that they were spanked, hit, and punished when they violated

their mothers’ rules. In reaction to pictures depicting mother figures in the

Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), comedians were less likely than the actors to

describe these women as having maternal qualities or to refer to them specifically

as mothers. In contrast, they did ascribe paternal identity to father-like figures in

the same task.

Contrary to Fisher and Fisher, Janus (1975) found that male comedians over-

whelmingly reported being closer to their mothers, indicating that mothers

played a more active role in their lives than did their fathers. Mothers were seen

as more accepting figures than fathers, spending more time with them, encourag-

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Childhood experiences of comedians 493

ing them to pursue a comic career, and better understanding their need to become

a comedian. Fathers were often absent during their childhood, or generally unin-

terested in their career and even discouraging them from pursuing it. Fathers also

failed in many cases to support their families, forcing the mothers to go to work.

The fathers were also resentful of the close bond between the mothers and the

aspiring comedians.

In a subsequent study with female comedians, Janus et al. (1978) found an

opposite trend. Female comedians felt closer to their fathers, and several of them

reported being raised without a mother, who died at an early age. Fathers were

role models for the comediennes, and they grew up admiring them. Similar to the

male comedians, fathers were generally described as poor providers, and the co-

mediennes felt they needed to support and encourage them. Their mothers were

described as unsuccessful, struggling, and unhappy, and most of them lived the

traditional role of a housewife. Relationships with their siblings were good, over-

all, and interestingly, 55% of comediennes were the youngest child in the family.

With regard to academic performance and relationships with peers, Fisher

and Fisher (1981) found that comedians struggled with school and were below

average students. Comedians tended to be funny early in life and in school, de-

scribing themselves as being the class clowns, mocking teachers and friends and

making practical jokes. In Janus’ (1975) study, comedians reported having good

relationships with peers and siblings, though they often felt misunderstood,

being picked on and disparaged. Janus also reported that comedians’ childhood

experiences were marked by isolation, suffering, and deprivation feelings. In his

view, being funny serves as a defense mechanism against panic and anxiety. Only

when on stage could they enjoy a short period of relief from their fears. Janus

concluded that comedians were sad, depressed, suspicious, and angry (Janus

1975). These findings are consistent with another study of 96 class clowns, most

of them male, from a middle school (Damico & Purkey 1978). The study found that

the class clowns were more assertive, disobedient, attention-seeking, cheerful

and showed leadership, but were worse students, compared to their classmates,

as evaluated by their teachers. The class clowns in this study asserted that they

were not well understood by their parents and had negative attitudes toward

teachers and principals.

All these experiences in school, combined with their relationship with their

parents, suggest that comedians become what they are in an effort to seek con-

trol, get approval from friends and family, and prove that they are good and

worthy. Comedians’ performance on stage, in this view, comes as a defense or

compensation mechanism for their melancholy lives, whereby they attempt to

channel feelings of anger and anxiety into their comedy act and seek the love of

the audiences (Fisher and Fisher 1981). Using humor as a coping mechanism is

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

494 Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

not unique to professional comedians; humor has long been viewed as a healthy

defense mechanism or coping strategy for adults as well as children (Dixon 1980,

Freud 1928, Vaillant 2000).

The Janus and Fisher and Fisher studies rely heavily on a psychoanalytical ap-

proach that is largely based on projective tests with low reliability and validity and

subjective interpretation (e.g. Wood et al. 2001, Wood et al. 2003). This makes it hard

to come to robust conclusions about comedians’ childhood and early experiences,

and may account for the contradictory results in these studies, despite using similar

samples. Moreover, the comedy scene has changed dramatically since the time of

these studies, and comedians today may be quite different from the ones studied in

the past. Today there are many more professional comedians and aspiring comics,

and many more comedy clubs that host several performances each week. Thus, a

career in comedy may be less unusual and peripheral than it once was.

A further potential limitation of the Fisher and Fisher (1981) study is the use

of actors and other stage entertainers as a comparison group. These comparisons

might not be adequate to assess whether comedians indeed had unique child-

hoods and distinct relationships with parents, since both groups had unique

vocations that do not represent most of the population.

The present study attempts to answer two questions: (1) Do professional

comedians have unique relationships with parents compared to others? and (2)

What were their experiences in school and the nature of the relationships they

had with peers? The results could shed light on what factors influence the pursuit

of comedy as a career choice.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Thirty-one professional comedians (28 men, 3 women) were recruited through a

local comedy club in Albuquerque, NM. The comedians had an average age of

38.9 years (SD = 8.6, range 27–58). Comedians had an average of 15.3 years of edu-

cation (SD = 2.6). Twenty-two participants (71%) self-identified as White, 5 (16%)

as African American and 4 (13%) as Hispanic.

Four hundred undergraduates (200 males, 200 females) enrolled in psychol-

ogy courses at the University of New Mexico participated in the study and re-

ceived partial course credit for participation. The average age of the students was

20.6 years (SD = 4.7, range 18–57). Participants had an average of 13.4 years of edu-

cation (SD = 1.3). Two hundred thirty-one participants (58%) self-identified as

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Childhood experiences of comedians 495

White, 117 (29%) as Hispanic, 19 (5%) as Asian, 14 (3.5%) as American Indian, 12

(3%) as African American, and 5 (1.5%) as other.

Up to 15 students sat in a classroom together and completed the question-

naires. Professional comedians were recruited by the first author introducing

himself after they performed at the comedy club, and asking if they wanted to

participate in a study on the psychology of humor. A meeting on a later day was

scheduled for those who agreed to participate. Meetings were held in a coffee

shop during the day, while the comedians were off work. All comedians signed

informed consent before participating and were debriefed after they completed

the questionnaires. After each questionnaire was completed, it was put in a box

with the other comedians’ questionnaires to ensure anonymity. Comedians were

compensated with a small meal during the meeting.

2.2 Relationship with parents

To assess relationships with parents, participants completed the Parental Bond-

ing Instrument (PBI) (Parker et al. 1979). The PBI is a 25-item questionnaire that

measures parental styles as perceived by the participant in retrospect. The par-

ticipants were instructed to answer how much a described behavior or attitude

reflected their parent in the first 16 years of their lives. The answers range from 1

– “very like” to 4 – “very unlike”. Twelve items measure the parent’s “care” (e.g.

“Was affectionate to me”), and 13 measure “overprotection” (e.g. “Tried to control

everything I did”). For each parental style, the scores for those items are summed.

The instrument is completed for both mothers and fathers separately.

Some of the participants in this study were raised by only one parent. These

participants were included in the data analysis pairwise, for that parent only, but

were omitted from analyses where no relevant data is available. Also, if partici-

pants had a stepparent, while still maintaining a relationship with their biological

parent, they were instructed to answer about the parent that was more significant

for them, and with whom they had spent the most time.

The PBI has good reliability and validity (Lizardi & Klein 2005, Wilhelm et al.

2005, Wilhelm & Parker 1990). Cronbach’s αs for the current study revealed

high internal consistencies: mother’s care = .93, father’s care = .93, mother’s

overprotection = .86, and father’s overprotection = .86.

2.3 Relationship with peers

To measure relationships with peers, participants completed the Peer Relation-

ships and Humor Questionnaire, which was developed specifically for this study

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

496 Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

and consists of questions about social life and humor used in school. There were

eight retrospective questions, repeated for each of three grades (6th, 9th, and 12th).

Participants had to compare themselves to others on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1

means they were below average on this question and 7 means they were above

average. Scores were averaged for each question across the three time periods.

Cronbach’s αs for the all eight constructed averages were high and ranged from

.66 to .88. The first four questions measure popularity, while the last four ques-

tions assess social uses of humor. The questions were:

1. Compared to others, how many same sex friends did you have during the

following periods of time?

2. Compared to others, how many opposite sex friends did you have during the

following periods of time?

3. Compared to others, how often did others seek you out for social activities

during the following periods of time?

4. Compared to others, how popular were you during the following periods of

time?

5. Compared to others, how often did you make fun of yourself during the

following periods of time?

6. Compared to others, how much were you considered as the class clown

during the following periods of time?

7. Compared to others, how much were you the butt of the jokes of other

people during the following periods of time?

8. Compared to others, how much did you make fun of other people during the

following periods of time?

3 Results

An index for each question on the Peer Relationships and Humor Questionnaire

was calculated, based on the average score for each question across the three

time periods. Table 1 displays the correlations among all four social uses of humor

for both comedians and students in the full sample. For comedians there were

two significant positive correlations, between being the butt of the jokes and

made fun of oneself (.42), and between making fun of others and being the class

clown (.36). All correlations among students were positive and significant.

Since most of the comedians in this study were men, a separate analysis for

male only was conducted and is shown in table 2. In this analysis, only the cor-

relation between being the butt of the jokes and made fun of oneself was signifi-

cant for comedians (r = .39, p < .05). For students, all correlations were again

positive and significant, albeit slightly lower compared to the entire sample.

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Childhood experiences of comedians 497

Made fun of Class clown Butt of jokes Made fun of

oneself others

Made fun of oneself .17 .42* .31

Class clown .35*** .13 .36*

Butt of jokes .29*** .39*** .21

Made fun of others .35*** .34*** .27***

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Table 1: Full sample Pearson correlations between the four social uses of humor scales for

comedians (N = 31, above the diagonal) and for students (N = 400, below the diagonal)

Made fun of Class clown Butt of jokes Made fun of

oneself others

Made fun of oneself .12 .39* .32

Class clown .32*** .03 .29

Butt of jokes .27*** .33*** .14

Made fun of others .34*** .34*** .25***

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Table 2: Men only Pearson correlations between the four social uses of humor scales for

comedians (N = 28, above the diagonal) and for students (N = 200, below the diagonal)

Next, the correlations between the four humor behaviors with PBI and peer

relationships are displayed in Tables 3 (for the whole sample) and table 4 (for

men only). Overall, the results indicate that for comedians, both being the class

clown and making fun of others positively correlate with number of friends of

both sexes and popularity. There were no significant correlations between the

humor questions and the PBI. Very similar results were obtained using only the

men’s data.

Table 5 shows the means and standard deviations for each scale for comedi-

ans and students, for both the full sample and the men only sample. Using t-test,

we compared the differences between comedians and students on each of the

four scales of the PBI. None of the differences were statistically significant for

both the full sample and the men-only sample.

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

498 Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

Made fun of Class clown Butt of jokes Made fun of

oneself others

Mother care

Comedians −.06 −.24 .10 −.06

Students . 04 .04 .03 .11*

Mother overprotection

Comedians .18 .24 .24 .26

Students −.04 −.04 .02 .01

Father care

Comedians .33 .38 −.02 .06

Students .11* .01 −.01 .07

Father overprotection

Comedians .10 −.07 .16 .25

Students −.09 −.06 .10 −.05

Same sex friends

Comedians .25 .44* −.09 .40*

Students .20** .15** .04 .08

Opposite sex friends

Comedians −.01 .46* −.01 .43

Students .17** .19** −.04 .07

Seek social activities

Comedians .33 .26 .09 .40*

Students .21** .24* −.09 .16**

Popular

Comedians −.01 .59** −.19 .34*

Students .23** .26** −.07 .12*

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

Table 3: Full sample Pearson correlations between the four humor behaviors, PBI and peer

relationships for stand-up comedians (N = 31) and for students (N = 400)

Next, we compared the two groups on each of the items in the Peer Relation-

ships and Humor Questionnaire. Results are shown in Table 6, along with Co-

hen’s d (Cohen 1988). There were no significant differences in any of the four

scales that measure social relationships with peers. In contrast, comedians

scored significantly higher on each of the questions that pertain to humor activi-

ties with peers.

Again, a comparison between male comedians and male students was con-

ducted on the same scales. Results were similar to the whole sample, albeit with

smaller effect sizes. There were non-significant differences on the first four scales.

For the other four scales, male comedians scored higher on each dimension.

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Childhood experiences of comedians 499

Made fun of Class clown Butt of jokes Made fun of

oneself others

Mother care

Comedians .01 −.27 .21 −.09

Students −.10 −.06 −.01 .03

Mother overprotection

Comedians .17 .08 .09 .11

Students −.02 −.04 .06 .07

Father care

Comedians .28 .40 −.01 .13

Students .01 .01 .04 −.01

Father overprotection

Comedians .08 −.22 .03 .14

Students .01 −.03 −.06 −.01

Same sex friends

Comedians .31 .43* .02 .44*

Students .32** .17* −.01 .14*

Opposite sex friends

Comedians −.03 .51** −.08 .35

Students .23** .21** −.01 .15*

Seek social activities

Comedians .28 .25 −.01 .45*

Students .28** .27** −.09 .19**

Popular

Comedians −.07 .56** −.26 .34

Students .27** .23** −.13 .10

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

Table 4: Men only Pearson correlations between the four humor behaviors, PBI and peer relation-

ships for stand-up comedians (N = 28) and for students (N = 200)

The students’ sample reveals two significant sex differences. Men were more

likely to report being the class clown (t [396] = 6.55, p < .001, d = 0.66), and more

likely to be the butt of the joke (t [395] = 3.84, p < .001, d = 0.39). There was a slight

tendency for men to be more likely to make fun of others, (t [398] = 1.75, p < .1,

d = 0.18).

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine whether professional comedians differ

from others in their relationships with parents and peers during childhood and

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

500 Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

Students Comedians (n = 31) t d

Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

PBI–mother

Care

Full sample 28.26 (7.88) 28.00 (6.61) 0.18 0.03

Men only 29.25 (5.86) 28.04 (6.73) 0.91 0.19

Overprotection

Full sample 14.41 (7.64) 13.87 (6.63) 0.39 0.07

Men only 14.06 (7.79) 13.78 (5.96) 0.18 0.04

PBI–father

Care

Full sample 24.04 (9.13) 22.32 (9.77) 0.91 0.18

Men only 22.87 (8.95) 23.22 (9.65) 0.16 0.04

Overprotection

Full sample 12.62 (7.89) 10.56 (5.85) 1.73 0.30

Men only 11.42 (7.66) 10.44 (5.72) 0.62 0.15

Table 5: Means, standard deviations and effect sizes for PBI scales by group for the full sample

(400 students, 31 comedians) and for men only sub-sample (200 students, 28 comedians)

adolescence. Overall, there were no differences in the way comedians describe

how their parents treated them, compared to the students’ descriptions. Major

differences emerged in respect to the way they report having used humor with

their peers during adolescence. Results also showed that relationships with par-

ents are largely independent of relationships with peers.

The results suggest that the interactions of comedians-to-be with people

within the same age group are important to their development as comedians. This

is consistent with the fact that humor is a social phenomenon. There is abundant

evidence showing that people engage in humor and laugh more frequently when

they are with other people than alone, and that humor plays an important role in

peer bonding and attracting mates (Greengross & Miller 2008, Lundy et al., 1998,

Martin & Kuiper 1999, Provine 2000). Making fun of others and being the class

clown allow individuals to connect with others. Granted, not all class clowns be-

come professional comedians, but those who do might observe how others enjoy

their humor, and decide to advance their skills toward the pursuit of a comic ca-

reer. Comedians’ use of different types of humor growing up might have built

their confidence, provided important experiences and contributed to the devel-

opment of their personality.

Comedians in this study also reported having a tendency to make fun of

themselves and being the butt of the joke. This tendency to use self-directed

humor was not related to any social benefits (popularity or number of friends) for

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Childhood experiences of comedians 501

Students Comedians t d

Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

Same sex friends 4.67 (1.25) 4.58 (1.69) −0.29 −0.06

Men only 4.86 (1.19) 4.76 (1.62) −0.31 −0.07

Opposite sex friends 4.39 (1.39) 4.14 (1.75) −0.95 −0.16

Men only 4.27 (1.36) 4.11 (1.82) −0.45 −0.10

Seek social activities 4.72 (1.30) 4.54 (1.18) −0.72 −0.14

Men only 4.62 (1.33) 4.55 (1.19) −0.23 −0.05

Popular 4.34 (1.22) 4.30 (1.27) −0.20 −0.04

Men only 4.39 (1.19) 4.38 (1.29) −0.06 −0.01

Made fun of oneself 3.88 (1.40) 4.50 (1.80) 2.32** 0.38

Men only 3.85 (1.35) 4.56 (1.84) 2.47* 0.44

Class clown 3.12 (1.74) 4.65 (1.64) 4.72*** 0.90

Men only 3.66 (1.78) 4.77 (1.55) 3.14** 0.67

Butt of the joke 3.05 (1.28) 3.60 (1.30) 2.32* 0.43

Men only 3.29 (1.18) 3.54 (1.21) 1.04 0.21

Made fun of others 3.47 (1.35) 4.35 (1.75) 3.41*** 0.56

Men only 3.59 (1.39) 4.34 (1.74) 2.60** 0.48

Positive effect size denotes that professional comedians scored higher than the students. df for

full sample comparisons are 427, and for the men sample df = 226.

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

Table 6: Comparisons and effect sizes between professional comedians and students on the

Peer Relationships and Humor Questionnaire indices. Results are shown for both the full

sample (N = 400 for students; N = 31 for comedians), and the men only sample (N = 200 for

students; N = 28 for comedians)

comedians, whereas among students it was moderately linked to popularity and

number of same and opposite sex friends. To attempt to explain this difference

between the comedians and students, it is important to note that people use self-

deprecating humor in a variety of ways, some beneficial and some not. For some

people, self-deprecating humor arises from a negative self-image and involves ex-

cessively self-disparaging humorous comments. For others, it arises from positive

self-esteem, and involves an ability to make light of one’s own weaknesses and

failures, in a self-accepting way (Greengross & Miller 2008, Martin et al. 2003).

The findings of Fisher and Fisher (1981) suggest that self-disparaging humor of

comedians may be more of the negative kind. They found that comedians, com-

pared to actors and other entertainers, were more likely to perceive themselves as

unworthy, to make negative remarks about themselves, and to view themselves

as small. These findings suggest feelings of uncertainty or lack of confidence

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

502 Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

among comedians, resulting in excessively self-disparaging humor that others

find unfunny and hence lowers the perceived popularity of the joke-teller. Cor-

roborating this is the strong relationship between self-deprecating humor and

being the butt of others’ jokes (for both comedians and students), suggesting that

comedians indeed used a negative style of humor. On the other hand, students

who use a keen self-deprecating humor that makes others laugh, enjoy higher

esteem among friends, as shown by the significant positive correlation between

self-directed humor and popularity in this group, whereas this correlation was

non-significant among comedians.

Consistent with previous studies, being the class clown was related to being

popular in general, and was also associated with having more friends from both

sexes (Warnars-Kleverlaan et al. 1996). These relationships are stronger for come-

dians than for students, suggesting that comedians might use humor as a tool for

social approval.

Also consistent with previous studies, there were overwhelmingly more male

than female comedians in this study (Fisher & Fisher 1981; Janus 1975). Despite

changes in the comedy industry over the last few decades, the percentage of

female comedians has remained at about 10–15%. It is not yet clear why there are

relatively few female comedians. However, it is noteworthy that more men report

being the class clowns, something that is consistent with previous studies

(Damico & Purkey 1978, Fisher & Fisher 1981, Janus 1975). Thus, males’ greater

tendency to use humor to make others laugh seems to begin in childhood and

adolescence.

Although this study uses a relatively small sample of professional stand-up

comedians, it is the largest quantitative study of such comedians done since the

pioneering work of Janus (1975) and Fisher & Fisher (1981). The results give no

support to the common view that comedians had especially difficult relationships

with their parents (as indexed by the care and over-protectiveness scales of the

PBI) or their adolescent peers. The main difference between professional come

dians and ordinary college students is that the comedians recalled being funnier

during adolescence.

While it is true that sense of humor is heritable to some degree (Manke 1998;

Vernon et al. 2008), humor is dynamic and changes throughout one’s life. It is not

known how comedians’ humor is similar to their parents, but it seems that they

develop their sense of humor in response to other people and to their own experi-

ences and feelings (Fisher & Fisher 1981, Janus 1975).

The current research is part of a larger study that aims to understand how

the personality, intelligence, humor styles and other aspects of modern stand-up

comedians differ from others (Greengross et al. 2012, Greengross & Miller 2009).

We used the Parental Bonding Instrument in an attempt to understand the

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Childhood experiences of comedians 503

r elationship between comedians and their parents. PBI is considered one of

the most reliable and valid measures for assessing relationships with parents.

Clearly, there are other measures that could be taken into account, most notably

the Parental Attachment Questionnaire (PAQ), which measures the extent to

which one experienced secure attachment with his or her parents (Kenny 1987).

We can only speculate as to how the two measures will compare, but we think

that the PAQ will replicate our findings that comedians exhibit no difference in

their attachment styles compared to the general population. Humor is a social

activity, and as such, we expect that the motivation to be a comedian and actual

humor ability are shaped in response to peers, not parents. This is of course just

an educated guess, and further studies should use different tools such as the

PAQ and other measures, in an attempt to examine different aspects of the

relationship between comedians and their parents, to better understand the pos-

sible differences in experiences comedians might have had compared to other

people.

We should note that the sample of comedians in our study, although it in-

cluded professional stand-up comedians, did not include any nationally known

comedians, or comedians that are at the top of their profession. The previous em-

pirical studies of comedians included top tier comedians (Janus 1975, Janus et al.

1978). Thus while all comedians in both studies were professionals, comparison

between the data in our study to the previous research may not be entirely accu-

rate. The results from the current study may therefore not generalize to great

comedians, ones that are on top of the comedy world.

One limitation to this study is that the comedians were older than the stu-

dents, and thus might be less accurate in their recall of childhood experiences.

However, the fact that comedians expressed both positive and negative attributes

about themselves growing up may indicate that the bias is relatively small. It is

also possible that while parents do not greatly influence adolescence, they do

influence the development of children’s humor in early years (McGhee and Chap-

man 1980). Another limitation is the relatively small sample of comedians (31).

The lack of statistical power might have yielded null results whereas it is possible

that with a larger sample size more results would have been significant. On the

other hand, because of the large sample size of students, some of the significant

results for the comparisons between the students and the comedians might be

overstated. Also, when comparing the full sample to the men only sample, similar

correlations and effect sizes might not retain their significant value. Thus, the

data should be interpreted as suggestive and not definitive. Further studies should

use larger sample size and take a deeper look at the interactions of comedians

among peers and others to better understand how and to what degree this dy-

namic might inspire the decision to become a comedian.

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

504 Gil Greengross, Rod A. Martin and Geoffrey Miller

References

Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edn.). Hillsdale,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Damico, Sandra B. & William W. Purkey. 1978. Class clowns: A study of middle school students.

American Educational Research Journal 15. 391–398.

Dixon, N. F. 1980. Humor: A cognitive alternative to stress? In I. G. Sarason & C. D. Spielberger

(eds.), Stress and anxiety, Vol. 7, 281–289. Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Fisher, Seymour & Rhoda Lee Fisher. 1981. Pretend the world is funny and forever: A

psychological analysis of comedians, clowns, and actors. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Freud, Sigmund. 1928. Humor. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 9. 1–6.

Greengross, Gil, Rod A. Martin & Geoffrey F. Miller. 2012. Personality traits, intelligence, humor

styles, and humor production ability of professional stand-up comedians compared to

college students. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts 6. 74–82.

Greengross, Gil & Geoffery F. Miller. 2009. The Big Five personality traits of professional

comedians compared to amateur comedians, comedy writers, and college students [July].

Personality and Individual Differences 47. 79–83.

Greengross, Gil & Geoffrey F. Miller. 2008. Dissing oneself versus dissing rivals: Effects of

status, personality, and sex on the short-term and long-term attractiveness of self-

deprecating and other-deprecating humor. Evolutionary Psychology 6. 393–408.

Janus, Samuel S. 1975. The great comedians: Personality and other factors. American Journal

of Psychoanalysis 35. 169–174.

Janus, Samuel S., Barbara E. Bess & Beth R. Janus. 1978. The great comediennes: Personality

and other factors. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis 38. 367–372.

Kenny, Maureen E. 1987. The extent and function of parental attachment among first-year

college students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 16. 17–29.

Lizardi, Humberto & Daniel N. Klein. 2005. Long-term stability of parental representations in

depressed outpatients utilizing the Parental Bonding Instrument. Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease 193. 183–198.

Lundy, Duane E., Josephine Tan & Michael R. Cunningham. 1998. Heterosexual romantic

preferences: The importance of humor and physical attractiveness for different types of

relationships. Personal Relationships 5. 311–325.

Manke, Beth. 1998. Genetic and environmental contributions to children’s interpersonal humor.

In Willibald Ruch (ed.), The sense of humor: Explorations of a personality characteristic

(Humor Research 3), 361–384. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Martin, Rod A. & Nicholas Kuiper. 1999. Daily occurrence of laughter: Relationships with age,

gender, and type A personality. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 12(4).

355–384.

Martin, Rod A., P. Puhlik-Doris, G. Larsen, J. Gray & K. Weir. 2003. Individual differences in uses

of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles

Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality 37. 48–75.

McGhee, Paul E. & Antony J. Chapman (eds.). 1980. Children’s humour. Chichester: John Wiley &

Sons.

Parker, Gordon, Hilary Tupling & L. B. Brown. 1979. A parental bonding instrument. British

Journal of Medical Psychology 52. 1–10.

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Childhood experiences of comedians 505

Provine, Robert. 2000. Laughter: A scientific investigation. New York: Viking.

Vaillant, George E. 2000. Adaptive mental mechanisms: Their role in a positive psychology.

American Psychologist 55. 89–98.

Vernon, Philip, Rod A. Martin, J. A. Schermer, L. Cherkas & T. Spector. 2008. Genetic and

environmental contributions to humor styles: A replication study. Twin Research and

Human Genetics 11. 44–47.

Warnars-Kleverlaan, Nel, Louis Oppenheimer & Larry Sherman. 1996. To be or not to be

humorous: Does it make a difference? Humor: International Journal of Humor Research

9(2). 117–141.

Wilhelm, Kay, Heather Niven, Gordon Parker & Dusan Hadzi-Pavlovic. 2005. The stability of the

Parental Bonding Instrument over a 20-year period. Psychological Medicine 35. 387–393.

Wilhelm, Kay & Gordon Parker. 1990. Reliability of the Parental Bonding Instrument and

Intimate Bond Measure scales. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 24.

199–202.

Wood, James M., M. Teresa Nezworski, Howard N. Garb & Scott O. Lilienfeld. 2001. Problems

with the norms of the Comprehensive System for the Rorschach: Methodological and

conceptual considerations. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 8. 397–402.

Wood, James M., M. Teresa Nezworski, Scott O. Lilienfeld & Howard N. Garb. 2003. What’s

wrong with the Rorschach?: Science confronts the controversial inkblot test. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

Acknowledgements

We thank Steve Gangestad, James Boone and two anonymous reviewers for their

useful comments and suggestions. A special thanks to Kari Greengross for her

assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

Brought to you by | Oakland University

Authenticated

Download Date | 6/1/15 9:39 PM

You might also like

- CEPE - Printable BDSM Checklist. August 2014Document41 pagesCEPE - Printable BDSM Checklist. August 2014hollywoodbear999990% (10)

- Day 1 SolutionsDocument6 pagesDay 1 SolutionsLiz KiNo ratings yet

- The 3D Printing Handbook - Technologies, Design and ApplicationsDocument347 pagesThe 3D Printing Handbook - Technologies, Design and ApplicationsJuan Bernardo Gallardo100% (7)

- Related Literature (Study Habits/Peer Pressure)Document11 pagesRelated Literature (Study Habits/Peer Pressure)William T. Ladrera75% (12)

- Extending Non-Monogamies: T&F Proofs: Not For DistributionDocument15 pagesExtending Non-Monogamies: T&F Proofs: Not For DistributionAaron HellrungNo ratings yet

- The Effects Absent Fathers Have On Female Development and College AttendanceDocument6 pagesThe Effects Absent Fathers Have On Female Development and College AttendanceShen ZertlahNo ratings yet

- Fostering Traditional Gender Roles or Androgyny in ChildrenDocument8 pagesFostering Traditional Gender Roles or Androgyny in ChildrenMegan Van DorenNo ratings yet

- 42-Article Text-39-1-10-20190619 PDFDocument28 pages42-Article Text-39-1-10-20190619 PDFZohra Mehboob AliNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles in Animated Cartoons_ Has the Picture Changed -- Teresa L_ Thompson; Eugenia Zerbinos -- Sex Roles, #9-10, 32, Pages 651-673, 1995 May -- 10_1007_bf01544217 -- Ffd29e2d6630a2046c65d303e879f455 -- AnnDocument23 pagesGender Roles in Animated Cartoons_ Has the Picture Changed -- Teresa L_ Thompson; Eugenia Zerbinos -- Sex Roles, #9-10, 32, Pages 651-673, 1995 May -- 10_1007_bf01544217 -- Ffd29e2d6630a2046c65d303e879f455 -- Annstudyprep19No ratings yet

- Stereotypes Influence How A Person Perceive One's Self and One's Self-IdentityDocument7 pagesStereotypes Influence How A Person Perceive One's Self and One's Self-IdentityezmoulicNo ratings yet

- (2008) VernonDocument10 pages(2008) VernonDrusya ThampiNo ratings yet

- Humor Style Similarity and Difference in Friendship DyadsDocument8 pagesHumor Style Similarity and Difference in Friendship DyadsElena NuțăNo ratings yet

- Katie BrookesDocument18 pagesKatie BrookesManole Eduard MihaitaNo ratings yet

- Rubin 1984Document28 pagesRubin 1984Yến NguyễnNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Parenting Styles On Strengths of Humanity: Love, Kindness and Social Intelligence in Myanmar AdolescentsDocument11 pagesThe Effect of Parenting Styles On Strengths of Humanity: Love, Kindness and Social Intelligence in Myanmar Adolescentsতা মা ন্নাNo ratings yet

- Thesis Gender StereotypesDocument8 pagesThesis Gender Stereotypesdenisehalvorsenaurora100% (2)

- סטריאוטיפים מגדריים-חבריםDocument51 pagesסטריאוטיפים מגדריים-חבריםsabagraniNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles and SocializationDocument6 pagesGender Roles and SocializationJenny May GodallaNo ratings yet

- Summary Feb 6 ArticlesDocument7 pagesSummary Feb 6 ArticlesRaphia MallickNo ratings yet

- Thesis Gender RolesDocument6 pagesThesis Gender RolesJim Jimenez100% (2)

- Gender Studies AssignmentDocument18 pagesGender Studies AssignmentPenuganti Ruthvij kumarNo ratings yet

- What Do Children Learn About Prosocial Behavior From The Media?Document6 pagesWhat Do Children Learn About Prosocial Behavior From The Media?Heather Edey WilliamsNo ratings yet

- A StudyDocument21 pagesA StudyNgười Trong BaoNo ratings yet

- Sex Stereotyping in Children's Toy AdvertisementsDocument14 pagesSex Stereotyping in Children's Toy AdvertisementsHanna GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Regarding: InvestigationDocument14 pagesRegarding: InvestigationJosé Augusto RentoNo ratings yet

- Modefying GenderDocument8 pagesModefying Genderwaleedms068467No ratings yet

- Santos Et Al-2017-Frontiers in PsychologyDocument9 pagesSantos Et Al-2017-Frontiers in PsychologyLiana Maria DrileaNo ratings yet

- Bullying and Victimization - Cause For Concern For Both Families and SchoolsDocument21 pagesBullying and Victimization - Cause For Concern For Both Families and SchoolsRosalinda RizzoNo ratings yet

- You Dippy TwatDocument24 pagesYou Dippy Twatjas3113No ratings yet

- Children With Absent Fathers Author(s) : Mary Margaret Thomes Source: Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Feb., 1968), Pp. 89-96 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 12/02/2014 00:12Document9 pagesChildren With Absent Fathers Author(s) : Mary Margaret Thomes Source: Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Feb., 1968), Pp. 89-96 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 12/02/2014 00:12Yuhao ChenNo ratings yet

- Parenting Styles and Self-Esteem, LucyDocument35 pagesParenting Styles and Self-Esteem, LucyMariam JintcharadzeNo ratings yet

- Update: KPWKPDocument11 pagesUpdate: KPWKPWilliam T. LadreraNo ratings yet

- T3week9 - Commonlit - Bullying-In-Early-Adolescence - StudentDocument8 pagesT3week9 - Commonlit - Bullying-In-Early-Adolescence - StudentJoshua Williams100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography - EditedDocument13 pagesAnnotated Bibliography - EditedMoses WathikaNo ratings yet

- Soc Psych Research 5Document7 pagesSoc Psych Research 5OSABEL GILLIANNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory and Child AbuseDocument7 pagesAttachment Theory and Child AbuseAlan Challoner100% (3)

- Grandparenting and Its Relationship To ParentingDocument30 pagesGrandparenting and Its Relationship To ParentingElsa PaulinaNo ratings yet

- Peer Relations and Later Personal AdjustDocument33 pagesPeer Relations and Later Personal AdjustPatricia TanaseNo ratings yet

- Masculinity and FemininityDocument6 pagesMasculinity and FemininitymuskanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0160252716300553 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0160252716300553 MainDiego Alejandro ZambranoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.141 On Thu, 06 Jan 2022 13:08:48 UTCDocument10 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.141 On Thu, 06 Jan 2022 13:08:48 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- Family Deficit ModelDocument11 pagesFamily Deficit ModelApril Joy Andres MadriagaNo ratings yet

- Sex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case StudyDocument8 pagesSex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case Studyapi-99042879No ratings yet

- Controversial Yet CompellingDocument15 pagesControversial Yet Compellingapi-495066746No ratings yet

- Hafen Et Al 2011 Homophily in Stable and Unstable Adolescent FriendshipsDocument6 pagesHafen Et Al 2011 Homophily in Stable and Unstable Adolescent FriendshipsJohn AnagnostouNo ratings yet

- Fathers GaysDocument10 pagesFathers GaysKevin Arditti VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- IPA Fathers and Daughters EDDocument16 pagesIPA Fathers and Daughters EDMaria CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Treatment of Deviant Sex-Role Behaviors in A Male ChildDocument18 pagesBehavioral Treatment of Deviant Sex-Role Behaviors in A Male ChildGabriel CandidoNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-312534222No ratings yet

- The Role of The FatherDocument2 pagesThe Role of The FatherTrish LauNo ratings yet

- Child Development - 2008 - Bolger - Peer Relationships and Self Esteem Among Children Who Have Been MaltreatedDocument27 pagesChild Development - 2008 - Bolger - Peer Relationships and Self Esteem Among Children Who Have Been MaltreatedMădălina MarincaşNo ratings yet

- Identity Confusion, Bisexuality, and Flight From The MotherDocument14 pagesIdentity Confusion, Bisexuality, and Flight From The Mothermgcm8No ratings yet

- Effects of Dysfunctional FamiliesDocument10 pagesEffects of Dysfunctional FamiliesemeraldNo ratings yet

- Jackson - 2006 - Wild Girls An Exploration of Ladette Cultures in Secondary SchoolsDocument24 pagesJackson - 2006 - Wild Girls An Exploration of Ladette Cultures in Secondary SchoolsAitanaNo ratings yet

- Cook, P.WDocument182 pagesCook, P.WManole Eduard MihaitaNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotypes and RolesDocument29 pagesGender Stereotypes and Rolesakhilav.mphilNo ratings yet

- Gender StereotypeDocument3 pagesGender StereotypeFreddie Bong Salvar PalaadNo ratings yet

- Child Rearing PracticesDocument8 pagesChild Rearing PracticesJessica Chin-loyNo ratings yet

- The Assessment of Elaborated Role-Play in Young Children: Invisible Friends, Personified Objects, and Pretend IdentitiesDocument19 pagesThe Assessment of Elaborated Role-Play in Young Children: Invisible Friends, Personified Objects, and Pretend IdentitiesGloria StahlNo ratings yet

- Gender Early SocializationDocument34 pagesGender Early SocializationYzelle Mae SaUmatNo ratings yet

- C o M M I T M e N T and Rival Attractiveness: Their Effects On Male and Female Reactions To Jealousy-Arousing SituationsDocument18 pagesC o M M I T M e N T and Rival Attractiveness: Their Effects On Male and Female Reactions To Jealousy-Arousing SituationsAlina Maria Burete-HeraNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Parental Conflict and Infidelity 1Document11 pagesRunning Head: Parental Conflict and Infidelity 1Angelica NicholeNo ratings yet

- 1.socio Economic Determinants of HealthDocument64 pages1.socio Economic Determinants of HealthdenekeNo ratings yet

- Maerskgroup Evaluatingstrategic TalentmanagementinitiativesDocument22 pagesMaerskgroup Evaluatingstrategic TalentmanagementinitiativesSameer FaisalNo ratings yet

- UserGuide - 510 - 570 - 653 PDFDocument25 pagesUserGuide - 510 - 570 - 653 PDFMurugananthamParamasivamNo ratings yet

- 1b Reading Output 2Document1 page1b Reading Output 2Elisha Maurelle AncogNo ratings yet

- Carter Procession Closure MapDocument1 pageCarter Procession Closure Mapcookiespiffey21No ratings yet

- 15 Win1 Midas-Xr New Brand enDocument18 pages15 Win1 Midas-Xr New Brand encristiNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution: How It Effect Victorian Literature in A Progressive or Adverse WayDocument2 pagesIndustrial Revolution: How It Effect Victorian Literature in A Progressive or Adverse WaydjdmdnNo ratings yet

- Photo Essay PDFDocument2 pagesPhoto Essay PDFMartha Glorie Manalo WallisNo ratings yet

- Office of The Punong Barangay Barangay Certification of AcceptanceDocument1 pageOffice of The Punong Barangay Barangay Certification of AcceptanceMah Jane DivinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - The Subject and Content of ArtDocument5 pagesChapter 3 - The Subject and Content of ArtJo Grace PazNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Philippine National Philippine National Philippine National Standard Standard Standard StandardDocument14 pagesPhilippine National Philippine National Philippine National Philippine National Standard Standard Standard StandardBernard Karlo BuduanNo ratings yet

- RPSG-IMS-HS-F - 01 - Hazard Observation CardDocument2 pagesRPSG-IMS-HS-F - 01 - Hazard Observation CardRocky BisNo ratings yet

- A Study in Satin I by TiggerDocument120 pagesA Study in Satin I by TiggerCereal69No ratings yet

- Mutiple Choice Question For Satellite CommunicationDocument4 pagesMutiple Choice Question For Satellite CommunicationRaja Pirian67% (3)

- Football g.9 s.2Document51 pagesFootball g.9 s.2apNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Full ExercisesDocument6 pagesSimple Past Full Exercisespablo1130No ratings yet

- Verge PH Swot AnalysisDocument3 pagesVerge PH Swot AnalysisPamela ApacibleNo ratings yet

- Easy Add-On Projects For Spectrum Zx81 and AceDocument189 pagesEasy Add-On Projects For Spectrum Zx81 and AceArkinuxNo ratings yet

- PeriodontitisDocument14 pagesPeriodontitisDanni MontielNo ratings yet

- Answer Scheme Test 1 MechanicsDocument10 pagesAnswer Scheme Test 1 MechanicsJayashiryMorganNo ratings yet

- Read Aloud Firefighters A To ZDocument3 pagesRead Aloud Firefighters A To Zapi-252331501No ratings yet

- Gardenia PlantsDocument6 pagesGardenia PlantsyayayayasNo ratings yet

- Mushaf Qiraat Hamzah - (Khalaf) PDF Latin SCRDocument26 pagesMushaf Qiraat Hamzah - (Khalaf) PDF Latin SCRujair ahmedNo ratings yet

- WRITING NewDocument21 pagesWRITING Newtini cushingNo ratings yet

- Operazione DoMS IITR IntroDocument1 pageOperazione DoMS IITR IntroSaransh MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Knowledge L3/E Comprehension L4/D Application L5/C Analysis L6/B Synthesis L7/A Evaluation L8/ADocument2 pagesKnowledge L3/E Comprehension L4/D Application L5/C Analysis L6/B Synthesis L7/A Evaluation L8/AWaltWritmanNo ratings yet

- Comparative Adjectives/advervbs, Past Tense PassiveDocument2 pagesComparative Adjectives/advervbs, Past Tense PassiveGintarė Staugaitytė-FedianinaNo ratings yet