Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dinardo 2018

Dinardo 2018

Uploaded by

Elaine IllescasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dinardo 2018

Dinardo 2018

Uploaded by

Elaine IllescasCopyright:

Available Formats

ARTICLE IN PRESS

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS • www.jpeds.com ORIGINAL

ARTICLES

Allergic Proctocolitis Is a Risk Factor for Functional Gastrointestinal

Disorders in Children

Giovanni Di Nardo, MD, PhD1,2,*, Cesare Cremon, MD3,*, Simone Frediani, MD4, Sandra Lucarelli, MD4, Maria Pia Villa, MD5,

Vincenzo Stanghellini, MD3, Giuseppe La Torre, MD6, Luigi Martemucci, MD1, and Giovanni Barbara, MD3

Objective To test the hypothesis that allergic proctocolitis, a cause of self-limiting rectal bleeding in infants, can

predispose to the development of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) later in childhood.

Study design We studied a cohort of 80 consecutive patients diagnosed with allergic proctocolitis. Their sibling

or matched children presenting to the same hospital for minor trauma served as controls. Parents of the patients

with allergic proctocolitis and controls participated in a telephone interview every 12 months until the child was at

least 4 years old. At that time, they were asked to complete the parental Questionnaire on Pediatric Gastrointes-

tinal Symptoms, Rome III version.

Results Sixteen of the 160 subjects (10.0%) included in the study met the Rome III criteria for FGIDs. Among

the 80 patients with allergic proctocolitis, 12 (15.0%) reported FGIDs, compared with 4 of 80 (5.0%) controls (P = .035).

After adjustment for age and sex, the OR for FGIDs in allergic proctocolitis group was 4.39 (95% CI, 1.03-18.68).

FGIDs were significantly associated with iron deficiency anemia, duration of hematochezia, and younger age at

presentation. In a multivariate analysis, only the duration of hematochezia was significantly associated with the

development of FGIDs (OR, 3.14; 95% CI,1.72-5.74).

Conclusions We have identified allergic proctocolitis as a new risk factor for the development of FGIDs in chil-

dren. Our data suggest that not only infection, but also a transient early-life allergic inflammatory trigger may induce

persistent digestive symptoms, supporting the existence of “postinflammatory” FGIDs. (J Pediatr 2017;■■:■■-■■).

See editorial, p •••

F

unctional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are defined as symptoms that, after appropriate medical evaluation, cannot

be attributed to another medical condition.1 These disorders are characterized by a dysregulation of the brain-gut axis,

associated with psychosocial factors, changes in intestinal motility, and visceral hypersensitivity.1-4 In addition, several

other abnormalities have been identified in subgroups of patients, including genetic factors, enteroendocrine dysfunction, neuroplastic

changes, gastrointestinal infections, altered microbiota, dietary factors, mucosal and systemic immune activation, and in-

creased mucosal permeability.5,6 Infectious gastroenteritis is a common trigger of FGIDs, particularly irritable bowel syndrome

(IBS), also in children.7-11 A long-term, prospective, controlled, culture-proven, follow-up study examining the association between

a single episode of Salmonella gastroenteritis and new-onset FGIDs showed that Salmonella-induced gastroenteritis during child-

hood, but not adulthood, is a risk factor for IBS.9 These results suggest that disruption of gut homeostasis early in life by acute

triggers may predispose the individual to susceptibility to the development of FGIDs later in life.9

Animal studies also have stressed the importance of early-life events in the development of visceral hypersensitivity.12 Psy-

chological or biological stressful events occurring soon after birth result in increased intestinal permeability during both the

neonatal and adult period and favor the occurrence of FGIDs later in life.13 Studies have shown that colonic inflammation during

an early, vulnerable period of neural plasticity leads to long-lasting hypersensi-

tivity that outlasts the acute inflammation.14 This phenomenon was not seen in

a similar experiment conducted in adult rats.14 Taken together, these studies point

toward a predominantly neurogenic mechanism that is more pronounced when From the 1Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit, Santobono-

Pausilipon Children’s Hospital, Naples, Italy; 2Pediatric

the inflammation occurs early in life. Gastroenterology Unit, International Hospital Salvator

Mundi, Rome, Italy; 3Department of Medical and Surgical

Although animal data are of great value in understanding the basic mecha- Sciences, University of Bologna, S. Orsola-Malpighi

nisms underlying neuroimmune interactions in the pathogenesis of sensorimo- Hospital, Bologna, Italy; 4Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit,

Sapienza University of Rome, Umberto I Hospital, Rome,

tor dysfunction, their translation to humans is not always possible. Human data Italy; 5Pediatric Unit, School of Medicine and Psychology,

Sapienza University of Rome, S. Andrea Hospital, Rome,

Italy; and 6Department of Public Health and Infectious

Diseases, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

*Authors contributed equally.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FAP Functional abdominal pain

FGID Functional gastrointestinal disorder 0022-3476/$ - see front matter. © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights

IBS Irritable bowel syndrome reserved.

https://doi.org10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.10.073

FLA 5.5.0 DTD ■ YMPD9576_proof ■ January 15, 2018

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS • www.jpeds.com Volume ■■ • ■■ 2017

on the role of inflammation in the first weeks of life in the risk sedation with midazolam (0.2 mg/kg). Endoscopic appear-

of developing subsequent FGIDs could greatly advance our ance of rectal and left colonic mucosa (Figure 2, A and B) was

knowledge on the pathogenesis of FGIDs. Saps et al15 sur- scored as reported previously.24 Mucosal biopsy specimens (at

veyed a large group of children with cow’s milk allergy early least 2) were obtained from the left colon (splenic flexure to

in life several years after their initial diagnosis and found a the rectosigmoid junction) and the rectum. A pathologist

higher frequency of FGID symptoms in children diagnosed with unaware of the clinical and laboratory data of the patients per-

cow’s milk allergy compared with healthy controls. formed all histological examinations. Histological grading was

Despite marked mucosal abnormalities, allergic proctoco- assessed as described previously.24 The scoring for eosinophil

litis is generally a cause of self-limiting rectal bleeding.16-23 Al- infiltration was adapted from previously described criteria

lergic proctocolitis may provide a human model in which to (Figure 2, C and D).25

study the role of temporary colitis on the development of FGID, Concentrations of serum-specific IgE antibody titers to

thus supporting a role for noninfectious causes of inflamma- common foods (cow’s milk, soy, rice, wheat, egg) were mea-

tion as an early-life predisposing factor for the development sured using the immuno-CAP system with a detection limit

of FGIDs later in childhood. of 0.35 kU/L IgE.26 Prick tests for common food proteins (eg,

The aim of this study was to prospectively evaluate the effect cow’s milk, soy, rice, wheat, egg) were performed as de-

of an early-life self-limiting human model of colitis on the de- scribed previously.27 Calprotectin was detected in the fecal

velopment of FGIDs, and the associated risk factors at least 4 samples of allergic proctocolitis group by a commercially avail-

years after the acute trigger. able enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test (Calprest

Eurospital, Trieste, Italy).

Methods

Therapeutic Approach and Follow-Up

This prospective controlled cohort study on the long-term Cow’s milk protein maternal avoidance has been recom-

outcome of allergic proctocolitis on digestive functional symp- mended for breast-feeding infants. If rectal bleeding contin-

toms and related risk factors comprised a cohort of consecu- ues for 72-96 hours, an extensively hydrolyzed formula is

tive patients diagnosed with allergic proctocolitis at the Pediatric prescribed. Children unresponsive within 72-96 hours to the

Gastroenterology Unit of Sapienza, University of Rome between extensively hydrolyzed formula are suggested an amino acid-

October 2006 and November 2011. The diagnosis of allergic based formula.23 Children with allergic proctocolitis had a clini-

proctocolitis was based on the American Gastroenterological cal follow-up every month until stable remission of symptoms

Association’s guidelines on the evaluation of food allergy in and tolerance acquisition were achieved, and then a tele-

gastrointestinal disorders.16 phone interview every 12 months until they reached at least

Owing to their similar genetic, environmental, and socio- 4 years of age, at which time they were mailed the validated

economic backgrounds, which can play a role in the preva- questionnaire. Healthy controls participated in a telephone in-

lence of FGIDs, siblings aged <6 years without a history of cow’s terview every 12 months until they reached at least 4 years of

milk allergy were selected as controls. Each index case was as- age. The cutoff of 4 years was fixed because FGID cannot be

signed a unique control. If a patient did not have a sibling or diagnosed according to the Rome III criteria until this age.

the sibling was aged >6 years or had a history of food allergy, Participants who met the following criteria were eligible for

another child of similar age and sex presenting to the same inclusion: at least 4 years of age at the time of mailing the ques-

hospital in the emergency department for evaluation of minor tionnaire, and no diagnosis of organic chronic disorder (based

trauma in the absence of previous chronic gastrointestinal on self-report and review of medical records). Parents of all

symptoms was recruited as a control. Each control subject was invited participants received a postal questionnaire and were

recruited within 4 weeks of the index case. A flow chart of re- asked to complete it and return it by mail. The questionnaire

cruitment is provided in Figure 1 (available at www.jpeds.com). was mailed up to 3 times to nonresponders. When no reply

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and was obtained, these individuals were contacted by telephone

conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A to encourage participation in the study. No personal inter-

letter explaining the rationale of the present study was pro- views were performed, to avoid interference with responses and

vided at all parents of the enrolled children, and written in- potential clinician assessment bias.

formed consent was obtained in all eligible cases. Parents were asked to review the child’s history and com-

Consecutive patients referred to our unit for suspected al- plete the parental Questionnaire on Pediatric Gastrointesti-

lergic proctocolitis underwent a screening visit including anal nal Symptoms, Rome III version (QPGS-RIII), a validated

inspection and stool culture to exclude other causes of rectal questionnaire for the diagnosis of FGIDs in children aged >4

bleeding. Blood tests, including concentrations of serum- years.28

specific IgE antibody, skin prick tests, and fecal calprotectin,

were performed within 1 week before the endoscopy in all eli- Statistical Analyses

gible cases. Rectosigmoidoscopy was performed to confirm the We estimated the sample size assuming that 2.0% of the sub-

diagnosis and to exclude other entities. One pediatric gastro- jects in the control group29 and 19.2% of the subjects in the

enterologist performed all endoscopic evaluation with a neo- exposed group15 would meet the criteria for FGIDs (ie, the

natal videogastroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), after deep primary endpoint of the study). With this assumption, a sample

2 Di Nardo et al

FLA 5.5.0 DTD ■ YMPD9576_proof ■ January 15, 2018

■■ 2017 ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Figure 2. Endoscopic (A and B) and histological (C and D) appearance of colonic mucosa in infants with allergic proctocolitis.

A, Partial lack of vascular pattern and mucosal friability with contact bleeding. B, Spontaneous bleeding and exudation. C, He-

matoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained section (10× hpf) showing a prominent, full-thickness eosinophilic infiltrate in the lamina propria.

D, H&E-stained section at higher magnification (40× hpf) showing numerous eosinophils in the epithelium and lamina propria

with associated degenerative changes in the surface epithelium, focal goblet cell loss, and mucin depletion.

of at least 60 subjects would be needed in each group to have tients with allergic proctocolitis experienced complete reso-

80% power with a type I error of 0.05. The sample size was lution of rectal bleeding, and their diagnosis was unchanged

estimated according to Dupont and Plummer30,31 using the “PS during follow-up. In the control group, no patients devel-

Power and Sample Size Calculations” software of the Depart- oped an organic disorder during follow-up. Demographic data

ment of Statistics, Vanderbilt University; version 3.0.12 were compared between the subjects who were successfully fol-

(http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/twiki/bin/view/Main/Power lowed up and completed the questionnaire and the eligible non-

SampleSize). The analysis was conducted using frequency and participants. Sex (P = .635) and age (P = .951) were well

contingency tables. Differences between groups were as- balanced between the 2 groups; thus, no selection bias was

sessed using c2 and Mann-Whitney tests for categorical and present in the study population. The demographic data of the

quantitative variables, respectively. A logistic regression analy- participants in the present study are provided in Table I.

sis was used to verify the association between FGID on aller- Overall, 16 of the 160 patients (10.0%) met the Rome III

gic proctocolitis, adjusted for age and sex. The results are criteria for FGIDs. In particular, among the 80 patients with

presented as OR and 95% CIs. The analysis was carried out allergic proctocolitis, 12 (15.0%) reported FGIDs, compared

using SPSS for Windows, release 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, New with 4 of 80 (5.0%) controls (P = .035). The univariate OR for

York). The statistical significance was set at P < .05. FGIDs in the patients was allergic proctocolitis was 3.35 (95%

CI, 1.03-10.89). In the allergic proctocolitis group, after ad-

justment for age and sex in the multivariate analysis, the OR

Results

Of the 189 subjects potentially eligible to participate in the study,

29 subjects (15.3%) were not included, 8 who could not be

Table I. Demographic characteristics of all patients in-

reached (change of address) and 21 who did not return the

cluded in the analysis

questionnaire (Figure 1). One hundred and sixty subjects

(84.7%) completed the symptom questionnaire, including 80 Allergic proctocolitis Control group

Characteristics group (n = 80) (n = 80)

in the allergic proctocolitis group and 80 in the control group.

Among these subjects, we were able to successfully match 53 Age, mean (SD) 5.96 (0.88) 7.66 (2.17)

Female sex: n (%) 43 (53.8) 38 (47.5)

patients with allergic proctocolitis with healthy siblings. All pa-

Allergic Proctocolitis Is a Risk Factor for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children 3

FLA 5.5.0 DTD ■ YMPD9576_proof ■ January 15, 2018

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS • www.jpeds.com Volume ■■

Table II. Univariate and multivariate analysis of vari- Table III. Demographic, clinical, laboratory, endo-

ables associated with development of FGIDs scopic, and histologic characteristics of patients with al-

Characteristic Unadjusted OR (95% CI) aOR (95% CI) lergic proctocolitis included in the analysis

Mean age, wk 0.94 (0.70-1.26) 1.15 (0.80-1.67) No FGIDs FGIDs

Sex Characteristics (n = 68; 85%) (n = 12; 15%) P value

Female 1.28 (0.45-3.64) 1.22 (0.42-3.51) Continuous variables

Male (reference) 1 1 Age, wk, mean ± SD 16.56 (4.45) 12.25 (6.09) .017

Group Duration of hematochezia, 3.50 (1.70) 8.00 (1.86) <.001

Alergic proctocolitis 3.35 (1.03-10.89) 4.39 (1.03-18.68) wk, mean ± SD

Control (reference) 1 1 Fecal calprotectin, µg/g, 115.23 (71.21) 123.42 (60.45) .329

mean ± SD

Categorical variables

Sex, n (%)

Female 36 (83.7) 7 (16.3) .730

for developing FGIDs was 4.39 (95% CI, 1.03-18.68) (Table II). Male 32 (86.5) 5 (13.5)

Among the 80 patients with allergic proctocolitis, 8 (10%) re- Breast-fed, n (%)

ported IBS, 3 (3.7%) functional abdominal pain (FAP), and No 57 (85.1) 10 (14.9) .966

Yes 11 (84.6) 2 (15.4)

1 (1.3%) reported constipation. Among the 80 controls, 1 Family history of atopy, n (%)

patient (1.3%) reported IBS, 2 patients (2.5%) reported FAP, No 55 (84.6) 10 (15.4) .841

and 1 patient (1.3%) reported constipation. Yes 13 (86.7) 2 (13.3)

Increased IgE, n (%)

Univariate analysis was performed to identify factors asso- No 66 (84.6) 12 (15.4) .547

ciated with FGIDs in the allergic proctocolitis group. FGIDs Yes 2 (100) 0 (0)

was significantly associated with the presence of iron defi- Positive allergy tests, n (%)

No 67 (85.9) 11 (14.1) .160

ciency anemia (1 of 68 [1.5%] patients who did not develop Yes 1 (50) 1 (50)

FGIDs vs 4 of 12 [33.3%] who developed FGIDs; P < .001), Iron deficiency anemia, n (%)

mean duration of hematochezia (3.5 ± 1.7 weeks in the 68 pa- No 67 (89.3) 8 (10.7) <.001

Yes 1 (20) 4 (80)

tients who did not develop FGIDs vs 8.0 ± 1.9 weeks in the 12 Endoscopic score, n (%)

who developed FGIDs; P < .001), and younger age at presen- 1 47 (85.5) 8 (14.5) .611

tation (mean, 16.6 ± 6.4 weeks in the 68 patients who did not 2 17 (81) 4 (19)

3 4 (100) 0 (0)

develop FGIDs vs 12.3 ± 6.1 weeks in the 12 who developed Histologic score, n (%)

FGIDs; P = .017). We did not find any significant correlation 1 46 (85.2) 8 (14.8) .650

between FGIDs and family history of atopy, positivity of allergy 2 20 (87) 3 (13)

3 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3)

tests, fecal calprotectin, endoscopic score, histological score, or Eosinophilic score, n (%)

eosinophil score (Table III). Using a multivariate approach and 1 23 (82.1) 5 (17.9) .628

including only the variables with a P value < .25 on the uni- 2 38 (88.4) 5 (11.6)

3 7 (77.8) 2 (22.2)

variate analysis, the only variable significantly associated with

the development of FGIDs was the duration of hematochezia

(OR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.72-5.74).

fecal calprotectin, and endoscopy with biopsies have been used

as tools to verify our hypothesis, but they should not be done

Discussion routinely.

Infectious gastroenteritis is the strongest risk factor for the

In this prospective controlled cohort study assessing the as- development of IBS and, to a lesser extent, functional dyspep-

sociation between allergic proctocolitis and new-onset FGIDs, sia, 2 of the main FGIDs.9,32,33 Here we have identified aller-

the novel main finding is evidence suggesting that an gic proctocolitis as a new risk factor for the development of

inflammatory/allergic self-limiting disorder occurring early in FGIDs, supporting the existence of “postinflammatory” FGIDs.

life, such as allergic proctocolitis, is a risk factor for the de- Allergic proctocolitis, a cause of rectal bleeding in exclusively

velopment later in life of digestive symptoms meeting the Rome breast-fed infants aged 1-6 months,17-23 may constitute an

III criteria for FGIDs. This was due especially to IBS, which elegant human model of colitis, with similarities to early-life

accounted for 66% of the new FGIDs in the allergic procto- inflammation in animal studies. In the rat model of neonatal

colitis group. Furthermore, we identified the duration of maternal separation, stress induces visceral hypersensitivity and

hematochezia as the only variable significantly associated with increased pain perception via mast cell degranulation, nerve

the development of FGIDs. These data suggest that not only growth factor, and transient receptor ion channel 1 modula-

infections, but also a self-limiting early-life allergic inflam- tion, in the absence of overt inflammation.34 Similar patho-

matory trigger, especially if prolonged, may induce digestive physiological mechanisms likely play a role also in our patients.

symptoms meeting the criteria for FGIDs. We did not find any In fact, adult studies suggest that an abnormal mucosal milieu

significant correlation between FGIDs and family history of and neuro-immune interactions, via mast cell activation and

atopy, positivity of allergy tests, fecal calprotectin, endo- nerve growth factor release, may be identified as key mecha-

scopic score, or histological score. We clarify that allergy tests, nisms in the pathophysiology of intestinal dysfunction and pain

4 Di Nardo et al

FLA 5.5.0 DTD ■ YMPD9576_proof ■ January 15, 2018

■■ 2017 ORIGINAL ARTICLES

transmission of IBS.35 It is interesting to note that the type of equally, the diagnosis of allergic proctocolitis was certain and

inflammation, as well as the period of life in which it occurs, other organic disorders that could mimic allergic proctocoli-

are crucial to defining its long-term effects. In fact, 2 re- tis were excluded, and colonic inflammation was evaluated and

search groups have recently showed that celiac patients on a staged by means of endoscopy, histology, and fecal calprotectin.

gluten-free diet36 and patients with inflammatory bowel disease Furthermore, the study was planned based on sample size cal-

in clinical remission37-39 have an FGIDs prevalence similar to culation, and the number of subjects who returned the ques-

that of the general pediatric population. tionnaires exceeded the calculated sample size, thus ensuring

The pathogenesis of FGIDs remains elusive and is likely a correctly powered primary endpoint of the study.

multifactorial.1 The new pathophysiological vision of FAP dis- A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing new-

orders in children suggests that sensitizing medical factors, in- onset IBS in 21 421 subjects with infectious enteritis showed

cluding distention, inflammation, and motility disorders, on an estimated pooled point prevalence of postinfectious IBS of

a background of genetic predisposition and early-life events 11%.33 The overall risk of new IBS is 4.2-fold higher in exposed

may induce changes in pain processing and visceral hyper- subjects compared with nonexposed subjects, and remains high

sensitivity, leading to abdominal pain and gastrointestinal beyond the first year of exposure and stable across adults and

symptoms.1 Our data show that an early-life event of allergic/ children. In adult patients, factors associated with an in-

inflammatory origin, such as allergic proctocolitis, occurring creased risk of postinfectious IBS include female sex, psycho-

in the first weeks of life may be the trigger for the develop- logical distress at the time of infection, use of antibiotics, and

ment of persistent digestive symptoms, particularly IBS. Early severity of the initial illness.33

in life, the intestine is characterized by an immature immune Interestingly, this study shows for the first time that the du-

system, altered intestinal permeability, and a delicate stage of ration of rectal bleeding in infants with allergic proctocolitis

microbiotic development, with complex interactions between is the sole variable significantly associated with the develop-

host and microbiota.40,41 In this critical phase, which repre- ment of FGIDs. This suggests that even in postinflammatory

sents a window of vulnerability, an early disruption of gut ho- FGIDs, the severity of the acute trigger is a determinant of per-

meostatic equilibrium by an acute trigger, such as allergic sistent digestive sequels. This could be explained by the pro-

proctocolitis, might predispose to susceptibility to the devel- longed release of inflammatory mediators during an early,

opment of FGIDs later in life. vulnerable period of neural plasticity, leading to altered enteric

In most cases, allergic proctocolitis is due to cow’s milk pro- nervous system physiology. Recent data support the concept

teins transferred via breast milk. Diagnosis is based on clini- that the release of factors with known effects on nerves in the

cal features and recovery after dietetic therapy.17-19 Rectal intestinal milieu not only might have functional effects, but

bleeding usually resolves within 72-96 hours of cow’s milk also might affect the enteric nervous system and sensory fibers

protein maternal avoidance; however, approximately 7% of pa- in a structural manner, inducing long-lasting neuroplastic

tients need an extensively hydrolyzed formula, and another 5% changes.35

require an amino acid-based formula.17,23 Recent data showed This study does have some limitations. Potential weakness

that preschoolers with a history of allergic disease had an in- includes the fact that all subjects were recruited in a single

creased risk of development of IBS on reaching school age, and center, and no information was collected on psychological status

that this risk increased in the presence of concurrent allergic and family dynamics, which may play a role in the pathogen-

disease and a higher clinical allergy burden.42 Saps et al15 pos- esis of FGIDs in children. Finally, although 66% of our new

tulated a link between food allergy and FGIDs, and studied a cases of FGIDs were linked to IBS, this study was not powered

large group of children with cow’s milk allergy early in life. for statistical comparisons among single FGIDs in patients with

They found a higher frequency of FGIDs symptoms in chil- allergic proctocolitis.

dren diagnosed with cow’s milk allergy compared with the In conclusion, we have identified allergic proctocolitis as a

healthy controls. Interestingly, our results are similar to those new risk factor for the development of FGIDs, particularly IBS,

reported by Saps et al, including the prevalence of new cases in early stages of life, and we have shown that the severity of

of FGIDs (19.2% in their study vs 15% in our present study), this illness is the most relevant factor in symptom develop-

largely linked to IBS (70% in their study vs 66% in our study). ment. If confirmed in future large-scale, multicenter studies,

That pioneering study had some important limitations, our findings may have important clinical implications. Because

however. First, its retrospective design does not exclude the pos- allergic proctocolitis is usually seen as a brief and self-

sibility of recall bias. Second, patients were categorized as having limited illness, its long-term effects are not considered. Future

cow’s milk allergy based on the physician’s clinical suspicion studies are warranted to evaluate whether different interven-

following diagnostic recommendations by the American tion strategies could potentially minimize the development of

Gastroenterological Association, and thus we cannot exclude FGIDs in allergic proctocolitis patients at higher risk. ■

the possibility that some of the patients labeled as having cow’s

milk allergy may have a different, unspecified condition. Third,

a lack of histological confirmation of colonic inflammation is Submitted for publication Jul 24, 2017; last revision received Sep 23, 2017;

accepted Oct 30, 2017

lacking. In contrast, our study was prospective with a well-

Reprint requests: Giovanni Barbara, MD, Department of Medical and Surgical

selected and characterized control group and a long-term Sciences, University of Bologna, S. Orsola-Malpighi Hospital, Pavilion 5, Via

follow-up period during which the 2 groups were surveyed Massarenti 9, Bologna, 40138, Italy. E-mail: giovanni.barbara@unibo.it

Allergic Proctocolitis Is a Risk Factor for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children 5

FLA 5.5.0 DTD ■ YMPD9576_proof ■ January 15, 2018

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS • www.jpeds.com Volume ■■

21. Dupont C, Heyman M. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: labo-

References ratory perspectives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;30 Suppl:S50-7.

1. Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg 22. Odze RD, Wershil BK, Leichtner AM, Antonioli DA. Allergic colitis in

M. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gas- infants. J Pediatr 1995;126:163-70.

troenterology 2016;150:1456-68. 23. Molnár K, Pintér P, Győrffy H, Cseh A, Müller KE, Arató A, et al. Char-

2. Zhou Q, Fillingim RB, Riley JL 3rd, Malarkey WB, Verne GN. Central and acteristics of allergic colitis in breast-fed infants in the absence of cow’s

peripheral hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain milk allergy. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:3824-30.

2010;148:454-61. 24. Oliva S, Di Nardo G, Ferrari F, Mallardo S, Rossi P, Patrizi G, et al.

3. Faure C, Wieckowska A. Somatic referral of visceral sensations and rectal Randomised clinical trial: the effectiveness of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC

sensory threshold for pain in children with functional gastrointestinal dis- 55730 rectal enema in children with active distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment

orders. J Pediatr 2007;150:66-71. Pharmacol Ther 2012;35:327-34.

4. Chumpitazi BP, Shulman RJ. Underlying molecular and cellular mecha- 25. Casella G, Villanacci V, Fisogni S, Cambareri AR, Di Bella C, Corazzi N,

nisms in childhood irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Cell Pediatr 2016;3:11. et al. Colonic left-side increase of eosinophils: a clue to drug-related colitis

5. Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:535-41.

J Med 2012;367:1626-35. 26. Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting

6. Barbara G, Feinle-Bisset C, Ghoshal UC, Quigley EM, Santos J, Vanner symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107:891-6.

S, et al. The intestinal microenvironment and functional gastrointesti- 27. Verstege A, Mehl A, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Staden U, Nocon M, Beyer

nal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1305-18. K, et al. The predictive value of the skin prick test weal size for the outcome

7. Saps M, Pensabene L, Di Martino L, Staiano A, Wechsler J, Zheng X, et al. of oral food challenges. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;35:1220-6.

Post-infectious functional gastrointestinal disorders in children. J Pediatr 28. Caplan A, Walker L, Rasquin A. Validation of the pediatric Rome II cri-

2008;152:812-6, 816.e1. teria for functional gastrointestinal disorders using the questionnaire on

8. Thabane M, Simunovic M, Akhtar-Danesh N, Garg AX, Clark WF, Collins pediatric gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr

SM, et al. An outbreak of acute bacterial gastroenteritis is associated with 2005;41:305-16.

an increased incidence of irritable bowel syndrome in children. Am J 29. Miele E, Simeone D, Marino A, Greco L, Auricchio R, Novek SJ, et al. Func-

Gastroenterol 2010;105:933-9. tional gastrointestinal disorders in children: an Italian prospective survey.

9. Cremon C, Stanghellini V, Pallotti F, Fogacci E, Bellacosa L, Morselli- Pediatrics 2004;114:73-8.

Labate AM, et al. Salmonella gastroenteritis during childhood is a risk 30. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations. A

factor for irritable bowel syndrome in adulthood. Gastroenterology review and computer program. Control Clin Trials 1990;11:116-28.

2014;147:69-77. 31. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations for

10. Pensabene L, Talarico V, Concolino D, Ciliberto D, Campanozzi A, Gentile studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials 1998;19:589-601.

T, et al. Postinfectious functional gastrointestinal disorders in children: 32. Spiller R, Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroen-

a multicenter prospective study. J Pediatr 2015;166:903-7.e1. terology 2009;136:1979-88.

11. Dupont AW. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol 33. Klem F, Wadhwa A, Prokop L, Sundt WJ, Farrugia G, Camilleri M, et al.

Rep 2007;9:378-84. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome after

12. Barreau F, Ferrier L, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. New insights in the etiol- infectious enteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenter-

ogy and pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome: contribution of ology 2017;152:1042-54.e1.

neonatal stress models. Pediatr Res 2007;62:240-5. 34. van den Wijngaard RM, Klooker TK, Welting O, Stanisor OI, Wouters MM,

13. Klooker TK, Braak B, Painter RC, de Rooij SR, van Elburg RM, van den van der Coelen D, et al. Essential role for TRPV1 in stress-induced (mast

Wijngaard RM, et al. Exposure to severe wartime conditions in early life cell-dependent) colonic hypersensitivity in maternally separated rats.

is associated with an increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome: a Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009;21:1107-94.

population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2250-6. 35. Dothel G, Barbaro MR, Boudin H, Vasina V, Cremon C, Gargano L, et al.

14. Al-Chaer ED, Kawasaki M, Pasricha PJ. A new model of chronic visceral Nerve fiber outgrowth is increased in the intestinal mucosa of patients

hypersensitivity in adult rats induced by colon irritation during postna- with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1002-11.e4.

tal development. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1276-85. 36. Saps M, Sansotta N, Bingham S, Magazzu G, Grosso C, Romano S, et al.

15. Saps M, Lu P, Bonilla S. Cow’s milk allergy is a risk factor for the devel- Abdominal pain-associated functional gastrointestinal disorder preva-

opment of FGIDs in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;52:166- lence in children and adolescents with celiac disease on gluten-free diet:

9. a multinational study. J Pediatr 2017;182:150-4.

16. Sampson HA, Sicherer SH, Birnbaum AH. AGA technical review on the 37. Diederen K, Hoekman DR, Hummel TZ, de Meij TG, Koot BG, Tabbers

evaluation of food allergy in gastrointestinal disorders. American MM, et al. The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms

Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1026-40. in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease, and the relationship with bio-

17. Lucarelli S, Di Nardo G, Lastrucci G, D’Alfonso Y, Marcheggiano A, Federici chemical markers of disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:181-

T, et al. Allergic proctocolitis refractory to maternal hypoallergenic diet 8.

in exclusively breast-fed infants: a clinical observation. BMC Gastroenterol 38. Zimmerman LA, Srinath AI, Goyal A, Bousvaros A, Ducharme P, Szigethy

2011;11:82. E, et al. The overlap of functional abdominal pain in pediatric Crohn’s

18. Maloney J, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Educational clinical case series for pedi- disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:826-31.

atric allergy and immunology: allergic proctocolitis, food protein- 39. Watson KL Jr, Kim SC, Boyle BM, Saps M. Prevalence and impact of func-

induced enterocolitis syndrome and allergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis tional abdominal pain disorders in children with inflammatory bowel dis-

with protein-losing gastroenteropathy as manifestations of non IgE- eases (IBD-FAPD). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;65:212-7.

mediated cow’s milk allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2007;18:360-7. 40. Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Mo-

19. Pumberger W, Pomberger G, Geissler W. Proctocolitis in breast-fed infants: lecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intes-

a contibution to differential diagnosis of haematochezia in early child- tine. Science 2001;291:881-4.

hood. Postgrad Med J 2001;77:252-4. 41. Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the

20. Xanthakos SA, Schwimmer JB, Melin-Aldana H, Rothenberg ME, Witte microbiota and the immune system. Science 2012;336:1268-73.

DP, Cohen MB, et al. Prevalence and outcome of allergic colitis in healthy 42. Tan TK, Chen AC, Lin CL, Shen TC, Li TC, Wei CC. Preschoolers with

infants with rectal bleeding: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr allergic diseases have an increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome when

Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;41:16-22. reaching school age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64:26-30.

6 Di Nardo et al

FLA 5.5.0 DTD ■ YMPD9576_proof ■ January 15, 2018

■■ 2017 ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Figure 1. Flowchart of study participants.

Allergic Proctocolitis Is a Risk Factor for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children 6.e1

FLA 5.5.0 DTD ■ YMPD9576_proof ■ January 15, 2018

You might also like

- D&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveDocument208 pagesD&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveLeonardo Sanchez100% (12)

- Nocerino, 2019Document8 pagesNocerino, 2019Adhytio YasashiiNo ratings yet

- Alergi Susu Sapi JurnalDocument12 pagesAlergi Susu Sapi JurnalIzni AyuniNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Rome IV Nonerosive Esophageal Phenotypes in ChildrenDocument6 pagesThe Prevalence of Rome IV Nonerosive Esophageal Phenotypes in ChildrenJonathan SaveroNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of A New Hypotonic Oral Rehydration Solution Containing Zinc and Prebiotics in The Treatment of Childhood Acute Diarrhea: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument6 pagesEfficacy of A New Hypotonic Oral Rehydration Solution Containing Zinc and Prebiotics in The Treatment of Childhood Acute Diarrhea: A Randomized Controlled TrialOlpinNo ratings yet

- Different Fecal Microbiota in Hirschsprung's Patients With and Without Associated EnterocolitisDocument12 pagesDifferent Fecal Microbiota in Hirschsprung's Patients With and Without Associated Enterocolitisklinik kf 275No ratings yet

- 1471 230X 11 82 PDFDocument7 pages1471 230X 11 82 PDFfennchuNo ratings yet

- Probiotics in Late Infancy Reduce The Incidence of Eczema: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument6 pagesProbiotics in Late Infancy Reduce The Incidence of Eczema: A Randomized Controlled TrialarditaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guidelines Secondary Prevention of Gastric CancerDocument1 pageClinical Guidelines Secondary Prevention of Gastric Cancerhenrique.uouNo ratings yet

- 19d. CPG Article - ESPGHAN 2008Document42 pages19d. CPG Article - ESPGHAN 2008Aditya Angela AdamNo ratings yet

- Foreign Body and Caustic Ingestions in Children - A Clinical Practice GuidelineDocument16 pagesForeign Body and Caustic Ingestions in Children - A Clinical Practice GuidelineMaría José Medina MercadoNo ratings yet

- Poi 140028Document8 pagesPoi 140028د. محمد فريد الغنامNo ratings yet

- Ajg 2009 524Document10 pagesAjg 2009 524Alex Cristian IonutNo ratings yet

- Allergy and Constipation Borelli Am J Gastroenterol 2009 PDFDocument10 pagesAllergy and Constipation Borelli Am J Gastroenterol 2009 PDFVanessadeOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Differential Mechanism of Periodontitis Progression in PostmenopauseDocument9 pagesDifferential Mechanism of Periodontitis Progression in PostmenopauseFelipe TitoNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Mortality in Newborns With EsophageaDocument5 pagesPredictors of Mortality in Newborns With EsophageaElvira PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Reliability of 17 Celiac DiseaseDocument9 pagesComparison of The Reliability of 17 Celiac Diseasesiddhi divekarNo ratings yet

- Pedsos 1Document7 pagesPedsos 1RizalMarubobSilalahiNo ratings yet

- Romani 2020Document9 pagesRomani 2020riri siahaanNo ratings yet

- Growth and The Microbiome - Integrating Global Health With Basic ScienceDocument3 pagesGrowth and The Microbiome - Integrating Global Health With Basic ScienceTania ItovaNo ratings yet

- Abses PayudaraDocument18 pagesAbses Payudaragastro fkikunibNo ratings yet

- Alergia AlimentariaDocument18 pagesAlergia AlimentariaLUIS PARRANo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0740002017304409 Main PDFDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0740002017304409 Main PDFDIEGO FERNANDO TULCAN SILVANo ratings yet

- Jurnal 7Document5 pagesJurnal 7aliyaNo ratings yet

- 2022 - Fecal Calprotectin As A Biomarker of Microscopic Bowel Inflammation in Patients With SpondyloarthritisDocument9 pages2022 - Fecal Calprotectin As A Biomarker of Microscopic Bowel Inflammation in Patients With SpondyloarthritisGustavo ResendeNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0091674916324873 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0091674916324873 MainDea PuspitaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673623009662 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0140673623009662 MainKesia MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Probiotics and Preterm Infants A Position Paper.26 ShareDocument17 pagesProbiotics and Preterm Infants A Position Paper.26 Shareendy tovarNo ratings yet

- Togias 2017Document16 pagesTogias 2017Jessica LópezNo ratings yet

- Changes in Fecal Microbiota and Metabolomics in A Child With JIA Responding To Two Treatment Periods With Exclusive Enteral NutritionDocument6 pagesChanges in Fecal Microbiota and Metabolomics in A Child With JIA Responding To Two Treatment Periods With Exclusive Enteral Nutritiondoc0814No ratings yet

- Microbiology 2Document2 pagesMicrobiology 2Horatiu NaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 141 Part2Document5 pages2017 Article 141 Part2Karina MonasaNo ratings yet

- Probiotics in The Prevention of Eczema A Randomised Controlled Trial 2014 Archives of Disease in ChildhoodDocument7 pagesProbiotics in The Prevention of Eczema A Randomised Controlled Trial 2014 Archives of Disease in ChildhoodThiago TartariNo ratings yet

- Full Text Jurnal LactobasilusDocument10 pagesFull Text Jurnal Lactobasilusrisda aulia putriNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Biomarkers As Predictive Indicators of Endometriosis A Prospective Case Control StudyDocument7 pagesPeripheral Biomarkers As Predictive Indicators of Endometriosis A Prospective Case Control StudySSR-IIJLS JournalNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Barrier Breakdown and Mucosal Microbiota Disturbance in Neuromyelitis Optical Spectrum DisordersDocument15 pagesIntestinal Barrier Breakdown and Mucosal Microbiota Disturbance in Neuromyelitis Optical Spectrum DisordersmagarciacastilloNo ratings yet

- Probiotics For The Prevention of Allergy A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesProbiotics For The Prevention of Allergy A Systematic ReviewadhyNo ratings yet

- Oral Candidiasis and in Ammatory Response: A Potential Synergic Contribution To The Onset of Type-2 Diabetes MellitusDocument8 pagesOral Candidiasis and in Ammatory Response: A Potential Synergic Contribution To The Onset of Type-2 Diabetes MellituskevandmwnNo ratings yet

- Pro BioticDocument6 pagesPro BioticYoga Zunandy PratamaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal RdsDocument6 pagesJurnal RdsNaman KhalidNo ratings yet

- Complex Gastrointestinal and Endocrine Sources ofDocument9 pagesComplex Gastrointestinal and Endocrine Sources ofBianca CaterinalisendraNo ratings yet

- Effect of A Glutamine-Enriched Enteral Diet OnDocument6 pagesEffect of A Glutamine-Enriched Enteral Diet Ondiajeng gayatriNo ratings yet

- Pro BioticDocument6 pagesPro BioticRizki WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Probiotic Allergic RhinitsDocument7 pagesProbiotic Allergic Rhinitscharoline gracetiani nataliaNo ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Trial of Talactoferrin Oral Solution in Preterm InfantsDocument9 pagesRandomized Controlled Trial of Talactoferrin Oral Solution in Preterm InfantsSardono WidinugrohoNo ratings yet

- Acute Gastroenteritis in Children of The World: What Needs To Be Done?Document8 pagesAcute Gastroenteritis in Children of The World: What Needs To Be Done?yoonie catNo ratings yet

- Biomarker 4Document6 pagesBiomarker 4Devianti TandialloNo ratings yet

- SpergelDocument11 pagesSpergelAnak Agung Ayu Ira Kharisma Buana Undiksha 2019No ratings yet

- Jurnal 3 Fater 2Document8 pagesJurnal 3 Fater 2ANDIANY CAHYANTY TAHIRNo ratings yet

- Association Between Vegf 936cT Gene Polymorphism With Gastric Premalignant Lesions and Vegf Levels in Helicobacter Pylori PatientsDocument3 pagesAssociation Between Vegf 936cT Gene Polymorphism With Gastric Premalignant Lesions and Vegf Levels in Helicobacter Pylori PatientsDavid NicholasNo ratings yet

- Does Atopic Dermatitis Cause Food Allergy? A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesDoes Atopic Dermatitis Cause Food Allergy? A Systematic ReviewInten WulandariNo ratings yet

- Diarrea en QuimioterapiaDocument6 pagesDiarrea en QuimioterapiaPaola DiazNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Study of Korean Adults With Food Allergy: Differences in Phenotypes and CausesDocument6 pagesA Retrospective Study of Korean Adults With Food Allergy: Differences in Phenotypes and CausesAngga Aryo LukmantoNo ratings yet

- Efficiency of Web Application and Spaced Repetition Algorithms As An Aid in Preparing To Practical Examination of HistologyDocument2 pagesEfficiency of Web Application and Spaced Repetition Algorithms As An Aid in Preparing To Practical Examination of HistologyduffuchimpsNo ratings yet

- Esmaeilinezhad Et Al 2019Document8 pagesEsmaeilinezhad Et Al 2019ahmad azhar marzuqiNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0016508520302651Document11 pagesPi Is 0016508520302651ntnquynhproNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AnakDocument7 pagesJurnal AnakNurul SahanaNo ratings yet

- Once-Daily Plazomicin For Complicated Urinary Tract InfectionsDocument12 pagesOnce-Daily Plazomicin For Complicated Urinary Tract InfectionsharvardboyNo ratings yet

- Chronic DiareDocument13 pagesChronic Diareclara FNo ratings yet

- E794 FullDocument10 pagesE794 FullMaria Camila Ramírez GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Food Protein Induced Enterocolitis (FPIES): Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandFood Protein Induced Enterocolitis (FPIES): Diagnosis and ManagementTerri Faye Brown-WhitehornNo ratings yet

- Moore RDocument7 pagesMoore RElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- Payment Instructions For Docs RequestedDocument1 pagePayment Instructions For Docs RequestedElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- Outpatient Cheat CodeDocument18 pagesOutpatient Cheat CodeElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- Complications After Thigh Sarcoma ResectionDocument7 pagesComplications After Thigh Sarcoma ResectionElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- PAINAD ScaleDocument2 pagesPAINAD ScaleElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- Functional Actvity ScaleDocument1 pageFunctional Actvity ScaleElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- EPM BookmarkDocument2 pagesEPM BookmarkElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- CNB Vs IncisionDocument12 pagesCNB Vs IncisionElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- A Case of Recurrent Mesocolon Myxoid Liposarcoma and Review of The LiteratureDocument7 pagesA Case of Recurrent Mesocolon Myxoid Liposarcoma and Review of The LiteratureElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- AJCC 8th STSDocument5 pagesAJCC 8th STSElaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 690786Document17 pagesNi Hms 690786Elaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- Mansoor 2017Document36 pagesMansoor 2017Elaine IllescasNo ratings yet

- DCS Operating InstructionsDocument80 pagesDCS Operating InstructionsJavierNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in ResearchDocument14 pagesEthical Considerations in ResearchJoshua Laygo Sengco0% (1)

- antiheroDocument1 pageantiheroRakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Concepts of DemandDocument27 pagesConcepts of Demandujjwal chaudharyNo ratings yet

- PPTDocument30 pagesPPTAyush BaranwalNo ratings yet

- UGCF-Flowchart (4 Yrs Course)Document4 pagesUGCF-Flowchart (4 Yrs Course)cooljishu2020No ratings yet

- HRM Self StudyDocument19 pagesHRM Self StudyZiyovuddin AbduvalievNo ratings yet

- Caste, Identity Politics & Public SphereDocument7 pagesCaste, Identity Politics & Public SpherePremkumar HeigrujamNo ratings yet

- FlightDocument2 pagesFlightRich BaguiNo ratings yet

- Third Quarter Summative Test in Health 6Document3 pagesThird Quarter Summative Test in Health 6genghiz065No ratings yet

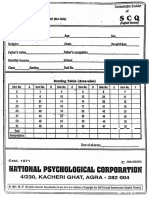

- Response Sheet For SCQDocument7 pagesResponse Sheet For SCQChandresh Gambhir100% (1)

- Bacillus Atrophaeus: (Atcc 9372™)Document2 pagesBacillus Atrophaeus: (Atcc 9372™)lenongnikaimutNo ratings yet

- Colegio Elena Ch. de Pinate: Ministry of EducationDocument10 pagesColegio Elena Ch. de Pinate: Ministry of EducationEdna Elida Guittens CamposNo ratings yet

- DOLE Philippines, Inc. vs. Medel Esteva, Et Al. G.R. No. 161115, November 30, 2006 Chico-Nazario, J.Document2 pagesDOLE Philippines, Inc. vs. Medel Esteva, Et Al. G.R. No. 161115, November 30, 2006 Chico-Nazario, J.Natalio Repaso IIINo ratings yet

- 18 Making Math Meaningful For Students With Learning Problems Powerful Teaching Strategies That WorkDocument79 pages18 Making Math Meaningful For Students With Learning Problems Powerful Teaching Strategies That WorkFroilan TinduganNo ratings yet

- Advanced Modeling of Online Consumer BehaviorDocument17 pagesAdvanced Modeling of Online Consumer BehaviorCesar GranadosNo ratings yet

- Revision QuestionsDocument2 pagesRevision QuestionsDimpho Sonjani-SibiyaNo ratings yet

- Ejercicio de InglesDocument1 pageEjercicio de InglesAleida PamelaNo ratings yet

- Ict PresentationDocument22 pagesIct Presentationadilattique859No ratings yet

- Structure, Properties, and Characterization of Polymeric BiomaterialsDocument45 pagesStructure, Properties, and Characterization of Polymeric BiomaterialsDedy FahriszaNo ratings yet

- Appeal To Force Examples - Google SearchDocument1 pageAppeal To Force Examples - Google Searchmark justine SosasNo ratings yet

- Anti-Drugs LawDocument2 pagesAnti-Drugs LawStrawHat LinagNo ratings yet

- Energetics PDFDocument166 pagesEnergetics PDFteeeNo ratings yet

- Announcement of Test Date, Time and VenueDocument240 pagesAnnouncement of Test Date, Time and VenueAriful IslamNo ratings yet

- Wade 1Document3 pagesWade 1api-609396716No ratings yet

- IEC 61850 Basics Modelling and ServicesDocument48 pagesIEC 61850 Basics Modelling and ServicesChristos ApostolopoulosNo ratings yet

- Constitution and By-Laws of SSCDocument12 pagesConstitution and By-Laws of SSCJaypee Mercado Roaquin100% (1)

- Voluntary Blood Donation in FemalesDocument8 pagesVoluntary Blood Donation in FemalesSam Chandran CNo ratings yet