Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Engaged Versus Disengaged Ownership: The Case of Pension Funds in The UK

Engaged Versus Disengaged Ownership: The Case of Pension Funds in The UK

Uploaded by

sita deliyana FirmialyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Engaged Versus Disengaged Ownership: The Case of Pension Funds in The UK

Engaged Versus Disengaged Ownership: The Case of Pension Funds in The UK

Uploaded by

sita deliyana FirmialyCopyright:

Available Formats

165

Corporate Governance: An International Review, 2013, 21(2): 165–182

Engaged versus Disengaged Ownership: The

Case of Pension Funds in the UK

Anna Tilba* and Terry McNulty

ABSTRACT

Manuscript Type: Empirical

Research Question/Issue: This study examines how the practice of pension fund investment management informs the

ownership behavior of pension funds vis-à-vis investee corporations.

Research Findings/Insights: Using data from: 35 in-depth semi-structured interviews with pension fund trustees, execu-

tives, investment officers and financial intermediaries; documentary analysis; and observations of four fund investment

meetings, we find a variation in pension fund behavior, where a very small number of well-resourced and internally

managed pension funds exhibit engaged ownership behavior. By contrast, the vast majority of pension funds operate at a

considerable distance from their investee corporations having delegated pension fund investment management to a chain

of external relationships involving actuaries, investment consultants, and fund managers. These relationships are laced with

divergent interests and influence dynamics, which explain why these pension funds give primary emphasis to fund

investment performance and display little concern for matters of ownership and corporate governance.

Theoretical/Academic Implications: The “New Financial Capitalism” is characterized by ownership concentration, yet at

the same time liquidity and a lack of institutional investor engagement with corporations. Findings suggest that the

principal-agent view of the relationship between institutional investors and corporate managers is more assumed than

demonstrated. This widely assumed theory of investor ownership and control is shown to be contingent upon the meanings

and practices that underpin investment fund management by institutions.

Practitioner/Policy Implications: Shareowner engagement is proposed as a solution to problems of corporate governance.

Findings about the relationships within the investment chain undermine the notions of pension funds behaving as owners

and upholding corporate governance and accountability. This raises skepticism about realizing aspirations for engaged

ownership and shareowner stewardship contained in institutional investors’ engagement codes such as the Stewardship

Code (2010) and contemporary policy debate in the UK and beyond.

Keywords: Corporate Governance, Institutional Shareholder, Pension Fund, Ownership, Stewardship

INTRODUCTION paradox is that while institutional investors seem to be

increasing in size and also the concentration of their stakes,

A gency theory provides a rationale for why investors, as

owners of corporate equity, should engage with firms

(Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Leech &

which gives them potential influence over managers, their

use of equity is generally liquid and without commitment.

This ownership paradox motivates us to examine whether

Leahy, 1991; Maug, 1998; Shleifer & Vishny, 1986). The institutional investors are actually able and/or willing to

underlying assumption is that the need to align the interests engage as owners.

of managers (the agents) with those of investors (the princi- An apparent lack of investor engagement in corporate

pals) provides investors with an incentive to participate in governance is of major concern to not only scholars of cor-

the company’s strategic direction (Anabtawi, 2006; Gillian & porate governance but also to practitioners and policy

Starks, 2000), in short to act as engaged owners. makers seeking to effect better corporate governance. Inves-

However, pointing to the present era of Financial Capital- tor disengagement is a subject of wide debate and signifi-

ism, Davis (2008, 2009) and Jackson (2008) observe an cance beyond the realm of academe. In the US such concerns

ownership paradox related to institutional investors. The are evidenced by Conference Board reports (e.g., Tonello,

2006), whilst in the UK the financial crisis has served to

*Address for correspondence: Dr. Anna Tilba, University of Liverpool Management

School, Chatham Street, Liverpool L69 7ZH, UK. Tel: 44 151 795 3717; E-mail: a.tilba@ heighten expectations of policy makers on institutional

liverpool.ac.uk investors to act as stewards and engaged owners of shares

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

doi:10.1111/j.1467-8683.2012.00933.x

166 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

(The Ownership Commission Report, 2012; The Stewardship held theory and set of assumptions about relations of own-

Code, 2010). A UK government sponsored study in 2011–12 ership and control. In keeping with qualitative inquiry being

(The Kay Review, 2012) aspires to longer-term investment a means to reconsider established theoretical ideas, this

behavior and equity markets that better serve fund benefi- research suggests that the principal-agent relationship as

ciaries and corporations. The Ownership Commission applied to institutional investor and corporate relations is

Report (2012) promotes the culture of “engaged ownership” more assumed than demonstrated in practice. Rather, the

with better links between the interests of the ultimate applicability of the theory is much more contingent on the

owners and the firms they own. features of investment funds as well as meanings and prac-

Pension funds are a type of institutional investor often tices employed by those managing funds, including finan-

associated with a potential to adopt a long-term perspective cial intermediaries. The contingent nature of the practice of

on equity holding and management and they are therefore investment management offers alternative explanations of

seen as potential model investors for stewardship (Davis, institutional investor behavior rooted in “trading” and

Lukomnik, & Pitt-Watson, 2006). Against this theoretical and “exit” behavior rather than “owner” and “voice” behavior.

practical backdrop, this study examines how pension funds’ The structure of this paper is as follows. We first review

investment management practice informs the ownership the literature on corporate ownership and control, highlight-

behavior of pension funds vis-à-vis investee corporations. ing an apparent paradox of institutional share-ownership

Consequently, through qualitative inquiry of actors and insti- concentration, which lacks the corresponding or desirable

tutions involved on the capital side of the ownership and investor engagement, vis-à-vis investee corporations

control debate, this study reports a marked difference in implied by agency theory. We then introduce UK pension

behavior of pension funds. On the one hand, a very small funds as the research context. Following a discussion of the

number of well-resourced and internally managed pension research design and methods, we draw on multi-method

funds exhibit behavior of engaged owners. However, these qualitative inquiry involving: interviews with pension fund

funds are an exception rather than the norm. By contrast, the trustees, executives, investment officers, and financial inter-

vast majority of pension funds operate at a considerable mediaries; observation of pension fund investment meet-

distance from their investee corporations, having delegated ings; and documentary analysis to explain the practices at

pension fund investment management to a chain of external work along the investment chain between pension funds

relationships involving financial intermediaries such as actu- and investee corporations, to reveal whether pension funds

aries, investment consultants, and fund managers. Further- behave as owners. We conclude by considering the signifi-

more, these relations of dependence along the investment cance of our findings with respect to academic and current

chain are laced with interests and influence which predispose policy debates, and offer some implications for further cor-

pension funds to give primary emphasis to fund investment porate governance research.

performance rather than an engaged approach to ownership.

Our study contributes to existing governance research in

several respects. Our analysis goes beyond a dyadic focus on CORPORATE OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL:

institutional investors and investee corporations as princi- INSTITUTIONAL OWNERSHIP AS A

pals and agents respectively, to attend to a broader examina- MECHANISM OF GOVERNANCE

tion of a wider system of diverse actors and relationships

involved in the investment chain that links capital providers Since Berle and Means (1932) examined the implications of

to corporations. Attention to the detailed practice of fund dispersed ownership using the separation of ownership and

investment reflects theoretical and methodological turns control thesis, ownership behavior by institutional investors

within the fields of organization studies and corporate gov- has been considered an important governance mechanism of

ernance research that are inclined to the detailed study of control to help align the interests of shareowners (princi-

behavior and processes (Ahrens, Filatotchev, & Thomsen, pals) and managers (agents) (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen &

2011; Pettigrew, 1992). Using this approach allows us to Meckling, 1976; Leech & Leahy, 1991; Maug, 1998; Shleifer &

account for heterogeneity among pension funds which is Vishny, 1986). Jensen and Meckling (1976) refer to agency

something that has been observed but not explained in the theory as “a theory of ownership” (p. 309) where equity-

literature (Cox, Brammer, & Millington, 2007; Del Guercio & holding institutional investors are seen as significant moni-

Hawkins, 1999; Monks & Minow, 1995; Ryan & Schneider, tors of managerial decisions (Anabtawi, 2006; David, Hitt, &

2002). By puncturing the image of homogeneity that often Gimeno, 2001; Gillian & Starks, 2000; Hoskisson, Hitt,

characterizes debates about institutional investors, this Johnson, & Grossman, 2002; Johnson, Schnatterly, Johnson,

study finds that pension funds are not a monolithic category & Chiu, 2010; Mallin, 1994).

of investor but vary according to fund type, size of assets, A relationship between institutional investor equity own-

maturity, internal investment management capabilities, and ership and corporate control has provided a theoretical plat-

liquidity requirements. These differences are critical to form for a substantial body of research aimed at addressing

explaining their investment practice and behavior vis-à-vis the fundamental agency problem involved in the separation

corporate management, and why there are marked differ- of corporate ownership and control. In his seminal work,

ences in engagement between pension funds. Hirschman (1970) has identified the investor/company rela-

Theoretically, the analysis serves not to overturn or rebut tionship within the “exit” or “voice” framework, where

agency theory and its view of institutional investors’ behav- investors sell the shares, or “exit,” if they are dissatisfied, or

ior (indeed, there is some evidence to support this – scenario express concerns to management though “voice.” Indeed,

A later in the paper), but it is a significant jolt to a widely the empirical evidence investigating this relationship is

Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013 © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

PENSION FUNDS’ OWNERSHIP 167

decidedly mixed (Bainbridge, 2003; Dalton, Hitt, Certo, & control the investee companies. Webb, Beck, and McKinnon

Dalton, 2007) and there is research both in the US and the UK (2003) argue that it is not the role of the institutional inves-

which casts doubts on the claims that institutional investors tors to act like banks, developing a long-term relationship

can and/or do act as an effective corporate governance with investee companies, because institutional investors

mechanism (Conyon & Sadler, 2010; Edwards and Hubbard, have different time horizons and abilities. Similarly,

2000; Gillian & Starks, 1998; Kahan and Rock, 2007; Karpoff, Hellman (2005) suggests that even large institutional inves-

2001; Renneboog & Trojanowski, 2003; Song & Szewczyk, tors cannot assume active ownership because these organi-

2003). zations do not have the organizational capacity or design to

Inconclusive evidence as to the institutional investor role acquire adequate knowledge about specific investee compa-

in corporate governance provides added impetus to research nies, so as to make any genuine or worthwhile contribution

a paradox observed by Davis (2008), and Jackson (2008), to discussions on corporate strategy.

in what they describe as a transition from “Managerial Significantly, Hendry, Sanderson, Barker, and Roberts

Capitalism” to an era of “New Financial Capitalism.” For (2006) find that in the case of investment fund managers, the

these writers an era of “New Financial Capitalism” is traditional conceptualizations of fund managers as “princi-

characterized by a re-concentration of corporate ownership pals” are not reflected in the day-to-day practice of these

in the hands of large investment fund managers and actors, who primarily behave as traders. Hendry, Sanderson,

pension funds, yet those same institutional investors are not Barker, and Roberts (2007) emphasize that the meetings

engaged in ownership behavior and lack voice (Davis, 2008; between the fund managers and the corporate executives are

Jackson, 2008). primarily used to inform trading decisions, rather than over-

seeing management as “owners” or “principals,” concerning

themselves with corporate governance issues such as execu-

Institutional Ownership Paradox: Concentration

tive pay, board structure and independence, and other

without Commitment governance concerns. In terms of the fund manager’s gover-

Davis (2008, 2009) and Jackson (2008), observe that although nance practices, they go on to conclude that any desire to

institutional investors seem to be increasing, in size, and the maximize shareholder value, and any political/moral moti-

concentration of their stakes, which gives them potential vations related to ideas of responsible ownership, act prima-

influence over managers, this concentrated ownership is rily as rationalizations rather than as genuine motivators,

generally liquid and without commitment. This is reflected and identify the main driving force for the “new

in the trend towards increased turnover and shorter average shareholder activism” of the institutional investor as the

stockholding periods (Tomorrow’s Owners, 2008). In the US, institutions’ own profit maximization and the need to posi-

Societe Generale Cross Asset Research (2008) shows that the tion themselves competitively in the lucrative investment

average period of holding stock on the New York Stock market.

Exchange (NYSE) was just 7 months. Similarly, in the UK, Together, the above studies provide a fair amount of skep-

the institutional investors’ portfolio turnover reached 56 ticism about the link between concentration of ownership

percent (Jackson, 2008), while the average duration of equity and active ownership on the part of institutional investors.

holding has fallen from five years in the 1960s to just over 7 This also causes us to question whether viewing the

months in 2009 (Haldane, 2010). investor/company relationship through the agency lens

The change in duration of shareholding and the apparent offers only a partial, idealized, and simplified view of this

lack of investor involvement with the investee companies relationship. Furthermore, there are also studies that iden-

provides an interesting context in which to consider the tify weaknesses and flaws in the investor’s own governance

question as to the investor’s desire and/or ability to act as an and accountability mechanisms, as a contributory factor in

owner. An impression of the distant and disengaged insti- the investor’s failure to exercise the desired shareowner

tutional investor runs counter to the principal/agent logic of stewardship (Davis, Lukomnik, & Pitt-Watson, 2009). Inter-

shareholder incentives to monitor and hold management to estingly and significantly for this study, Hendry et al. (2006)

account. Davis (2008) observes this “New Finance Capital- suggest that viewing the investor/company relationship

ism” to be theoretically puzzling since, historically, large through a simple lens of principal/agent does not provide

blockholders are generally associated with influence, if not an accurate reflection of current investment practices.

direct control, and generally building long-term relation- Hendry et al. (2006) also note a separation of the lines of

ships with the investee companies. For this reason, Davis accountability and responsibility between shareholding and

(2009) suggests that there is a need to develop new concep- share ownership. For example, the relationship between

tual tools to reflect the current changes in institutional inves- pension funds and their investment managers involves two

tor ownership behavior. This necessitates an examination of further intermediaries: the trustees of the pension fund and

the governance role and practices of other actors, such as the small group of investment consultants who advise them,

financial institutions and their intermediaries, within the and that the “agency problems of such layered relationships

market. are palpable” (p. 1124). Pye (2001) and Roberts, Sanderson,

Previously regarded as “the dominant conceptual founda- Barker, and Hendry (2006) also indicate that the multi-

tion for corporate governance research” (Dalton et al., layered relationships that the fund managers have both with

2007:34), agency theory is now challenged on the grounds the owners who supply capital, such as pension funds, and

of doubtful assumptions, uncertain predictions, and unin- the pension fund trustees, require further examination.

tended effects. A number of scholars articulate concern Theoretically, this line of argument stimulates attention to

about the ability and inclination of investors to monitor and the practices and complex relationships between a variety of

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013

168 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

actors, whose identity as principals or agents is not clear. choice of investment products, the level of investment in

Implied here is a more complex view of corporate gover- particular assets, and the choice of investment managers

nance, and specifically, the relational dynamics associated (Trustee Act, 2000). Clark (2000) observes that the dominant

with the governance notion of institutional investors acting arrangement of pension fund investment management is

as “owners” holding managers to account. Rather, emphasis extensive delegation through investment experts, mostly

is given to attending to what is happening within the pro- due to the lack of expertise inside the fund. A lack of trustee

cesses and relationships that encompass this array of actors investment expertise opens up a vital role for other financial

and institutions. Herein lays a conceptual platform from intermediaries and experts in the investment process (Clark,

which we build this study. In the next section, we introduce 2000). However, one of the principal concerns of the Myners

this research context by using a selection of UK pension Report (2001) and subsequent reviews of its progress, is that

funds as a case scenario, to examine institutional ownership of trustees’ excessive reliance on investment consultants.2

as a mechanism of corporate governance. Notwithstanding the apparent significance of consultants in

pension fund investment, they have received little attention

within the research literature. Furthermore, it is unclear how

RESEARCH CONTEXT: PENSION FUNDS the relationship between pension funds and their invest-

IN THE UK ment fund managers informs share ownership behavior.

Coincidentally, there are heightened expectations on

Pension funds are a good case to explore, as they may be pension funds to become engaged owners. Following gov-

considered to be the archetypal long-term investor. Pension ernance scandals, from Enron in 2001, to the collapse of

funds are one of the largest asset-owning types of investor in Lehman Brothers in 2008, a number of regulatory “soft-law”

the UK. Although pension fund ownership of the total UK codes in the UK such as the Myners Report (2001) and its

equity market has been declining, from 32.4 percent in 1992 subsequent reviews (HM Treasury, 2004, 2008); ISC’s

to 5.1 percent in 2010, in the period that preceded this study Responsibilities of Institutional Shareholders and Agents:

they held nearly 13 percent of total UK equity, exceeded only Statements of Principles (Institutional Shareholders Com-

by insurance companies, who owned nearly 15 percent mittee, 2007); NAPF (2007); The Walker’s Review (2009); and

(ONS, 2010). Pension funds invested 43.1 percent of their the most recent UK Stewardship Code (2010), have encour-

assets in UK equities, a figure that amounts to nearly £400 aged pension funds to be more engaged corporate owners.

billion (The Purple Book, 2010). By owning a considerable Yet UK studies that examine pension funds in relation to

share of UK equities, pension funds continue to play a major corporate governance are few, and yield conflicting results.

role in the evolution of UK ownership (Franks, Mayer, & Solomon, Solomon, Joseph, and Norton (2000), Clark and

Rossi, 2009). Furthermore, pension fund ownership of over- Hebb (2004), Mallin (1994, 2001, 2010) and Becht, Franks,

seas equity has been steadily increasing from 24 percent in Mayer, and Rossi (2009) suggest behavior of pension funds

2006 (The Purple Book, 2006) to 57.2 percent in 2011 (The akin to that of the engaged and active owner. However,

Purple Book, 2011). This suggests that the significance of Faccio and Lasfer (2000), Cox et al. (2007), Crespi and

pension fund ownership behavior stretches beyond the UK. Renneboog (2010) and FairPensions (2008; 2009) create an

The pension fund industry is remarkably concentrated, impression of pension funds operating very much as distant

with a relatively small proportion of big pension funds holders of shares.

dominating the flow of capital. The current conditions All in all, the nature of the interaction between pension

within the industry are characterized by economic recession, funds and corporations is subject to much theoretical and

unstable financial markets, and increasing pension fund normative prescription, but the empirical picture is ambigu-

liabilities and deficits. Since the financial crisis of 2008, and ous. It is crucial to examine how pension funds are

falls in equity markets, UK pension fund funding levels have connected to their investee companies, what practices and

dramatically worsened, decreasing from the highest of 111.4 relationships are at work along the investment chain, and

percent of pension fund funding in March 2007 to only 79.5 how these inform pension funds’ “ownership” behavior.

percent in March 2009 (The Purple Book, 2009). Further-

more, operating in a world where people live longer, also

means that pension funds’ liabilities have substantially RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

increased. Assuming the s179 valuation,1 the total assets of

6,885 pension funds in 2009 stood at £780.4 billion, while In the interest of research rigor and transparency, this

total liabilities were £981 billion. In effect, industry condi- section explains the research methods used; the sampling of

tions signify a profound change within the industry, which pension funds; the process of gaining access; and how the

is now characterized by most pension funds moving away data were collected and analyzed.

from being largely in surplus, to being in massive deficit.

These deficits have perhaps fuelled the trend towards the

Liability Driven Investment (LDI) strategies that also focus

Data Sources

on short-term investment performance. Qualitative data allow the researcher to build and develop

When it comes to pension fund governance and invest- theory by getting close to actors and settings in order to

ment management, pension fund trustees are given a central examine relationships and understand complex practices

role by virtue of their common law heritage. They have been (Shah & Corley, 2006). To understand pension funds owner-

entrusted with general investment powers and their fidu- ship behavior, we used data collected from actors involved

ciary responsibilities include making decisions about the in pension fund investment via an extensive semi-

Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013 © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

PENSION FUNDS’ OWNERSHIP 169

structured interview program (35 interviews), documentary under management exceeding £22 and £13 billion, respec-

analysis, and observations of four pension fund investment tively. Observing investment meetings enabled us to contex-

meetings. tualize interviewee’s accounts and shed more light on the

kind of processes and interactions that take place within

Sample of Funds and Interviewees. We used theoretical pension fund investment.

sampling (Shah & Corley, 2006) to identify the funds to The combination of interviews with observations signifies

study, and whom to interview. The literature on pension an important strength of this study. The formal and system-

fund governance suggests that pension fund context, size of atic method of data collection from multiple sources helped

assets, maturity, internal investment management capabili- to ensure the trustworthiness of our work (Shah & Corley,

ties, liquidity requirements, as well as pension fund type 2006). The two methods have also complemented one

(e.g., occupational or local authority fund), may be relevant another by illuminating and “validating” themes and issues

when determining the approach to investment management of interest (Bluhm, Harman, Thomas, & Mitchell, 2011).

and ultimately the fund’s relationship with investee corpo-

rations. Accordingly, these pension fund characteristics Documentary Analysis. Written documents were also

served as sample criteria which informed the identification an important source of information about pension funds,

of the pension funds in two phases of the research process. their organization, and investment management. In order to

As a first step, the Pension Funds Online Database3 was minimize the time spent asking general questions during

searched. Using the sorting tools in the database, 2,866 UK the interviews about matters for which information was

pension funds were sorted by their share of UK ownership. publicly available, pension fund organizational charts, offi-

The population range was generated according to fund size cial role descriptions, investment policy statements, invest-

in terms of capital value, the highest being over £37 billion ment performance evaluations, funding strategy statements,

and the lowest being just over £2 million. From the sorted annual reports and accounts, valuation reports, and similar

list, the largest top 100 occupational and local authority types of information were collected and studied prior to

pension funds were then selected for the second screening each interview.

phase.

In the next phase, the Top 100 pension funds were ana-

lyzed and cross-compared, to establish the characteristics Data Collection

such as pension fund type, amount of assets under manage-

Overall, data collection took place between August 2008 and

ment, allocation to equity, mode of investment management,

May 2009. As the fieldwork progressed, the research benefit-

and maturity. After examining these characteristics within

ted from a “snowball” effect in getting access to the inter-

the database listings, it was decided that there was enough

viewees and to observe meetings. Creswell (2007) suggests

diversity within these funds to reflect the different charac-

that 20–30 interviews are sufficient for building grounded

teristics and ensure a representative sample. The sample

theory, and this figure served as an approximate indicator of

represents both local authority and occupational pension

the extent of the interviewing component of the fieldwork.

funds, with assets under management ranging from £30

Subsequently, we found that we were reaching data satura-

billion to just under £1 billion, and total membership

tion point after conducting around 25 interviews, as it

ranging from 239,144 to just over 10,000.

became apparent that further distinct themes were no longer

All interviewees were selected with careful consideration

emerging from the interviews. After a short break and

of their professional role and the expected contribution to

further data analysis, the remaining ten participants were

this research project. Thus, the interview program covered

interviewed as a useful way to “validate” the existing

the roles of trustees, pension fund officers, executives and

accounts. In total, 35 semi-structured discussions occurred,

chief investment officers. In recognition that pension fund

with each respondent, lasting between 60 and 90 minutes.

investment decision making and management also involves

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed,

external experts, actuaries, investment consultants, and

resulting in approximately 42 hours of recordings and 548

investment fund managers were also interviewed. The

pages of transcriptions. Appendix A provides the list of

names and interviewee contact information were obtained

respondents. Appendix B contains the interview protocol.

from the Pension Funds Online UK Top 100 pension funds

listings; Actuaries & Pension Fund Consultants League Table

2007; and Investment Managers and Advisers League Table

2007.

Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. The

Observations. As the fieldwork gained momentum, process of initial data analysis began during the data collec-

access to observe four pension fund investment committee tion, and therefore lasted between August 2008 and Septem-

meetings was successfully negotiated. The lead author ber 2010. The data analysis was inductive and interpretative

observed an investment committee meeting of a local and aimed at obtaining deeper understanding of the pro-

authority pension fund with assets under management cesses and relationships between the key actors involved in

exceeding £3 billion; the Annual General Meeting of a Local pension fund investment. The process of analyzing the inter-

Authority Pension Fund Forum, which brings together 48 view data, comparing it with observational and documen-

local authority pension funds with combined assets under tary data, recoding the initial findings and going back to the

management exceeding £95 billion; and two investment literature resulted in a more systematic development of the

outlook meetings in occupational pension funds, with assets research themes.

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013

170 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

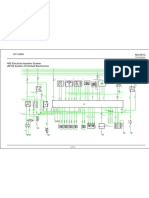

FIGURE 1

Data Analysis

First-Order Codes Second-Order Codes High-Level Themes Overarching Themes

Content analysis was used to analyze the interview tran- “interests” and “accountability.” This was a recursive rather

scripts. To warrant the robustness of this data analysis, we than a linear process; with analysis moving iteratively

used techniques similar to those used by Eisenhardt (1989), between the first- and second-order codes, with patterns in

Dacin, Munir, and Tracey (2010) and Creed, DeJordy, and the data emerging into conceptual themes (Dacin et al., 2010;

Lok (2010), which consisted of four steps. NVivo 8.0, a piece Eisenhardt, 1989).

of qualitative research software, was used to assist and facili- In the fourth step of the analysis, the emerging conceptual

tate the analysis of our qualitative data. Figure 1 demon- themes were organized into the overarching themes that

strates the data analysis showing the categories and themes informed our main findings and theoretical reflections.

from which we developed the findings and the relationship Three themes strongly emerged here: reliance on external

between them. expertise; dependencies along the investment chain; and

In the first step of the analysis, interview transcripts, influence and focus on investment performance.

entered in NVivo as text files, were coded on the basis of “in To ensure credibility of our analysis (Shah & Corley, 2006),

vivo” words. These consisted of descriptions offered by throughout the process, the authors discussed coding, cross-

interviewees, all revolving around pension fund investment referencing, and emerging themes. Also NVivo allowed the

and the associated practices of actuaries, investment consult- interview content to be analyzed systematically using codes,

ants and investment fund managers. These formed the first- keywords, word frequencies, reference counts, quantifying

order codes. theme coverage and theme cross-comparisons. To ensure

In the second step of the analysis, second-order codes were coding consistency, a random selection of ten interview tran-

identified. For example, comments on the first-order code, scripts were re-coded by an independent third-party inves-

such as pension fund investment management, were further tigator, albeit a person not directly involved in the study. The

grouped into codes or “tree nodes” labeled “context,” degree of agreement was measured using the Kappa value

“roles,” “investment aims.” Following Lincoln and Guba’s through NVivo Code Comparison Queries. There was a

(1985) recommendations, the second-order codes were then substantial agreement above chance with the Kappa value

refined through triangulation of interviews, with the notes found to be .71.

taken during the observations of meetings and documentary We also aimed to ensure that during the interpretation, the

analysis, to produce a set of higher-level nodes. This process data was linked with the research questions and concepts,

resulted in 1185 coded passages. and there was a close fit between the data and the research

In the third step of the analysis, links between second- claims (Easterby-Smith, Golden-Biddle, & Locke, 2008).We

order codes and higher-level nodes were collapsed to also kept a record of our data collection, management, and

produce theoretically distinct themes, for example, the analysis process to ensure objectivity. To help improve accu-

wider context was further grouped into nodes labelled racy, respondents’ feedback was also sought where possible

Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013 © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

PENSION FUNDS’ OWNERSHIP 171

(Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Usually this was done during the ing a fiduciary responsibility, to act in the best interests of

interview process, by reiterating the respondent’s state- the pension scheme’s beneficiaries, by deciding on pension

ments, to make sure the intended message was understood fund investment strategy – pension fund trustees and execu-

correctly. tives rely upon external expertise, for example, actuaries,

investment consultants, investment managers, and corpora-

tions. Accordingly, for this vast majority of pension funds the

RESEARCH FINDINGS investment management process is laced with dynamics of

dependence and influence, and the primary focus is on fund

Empirically, the research findings enable a distinction to be

investment performance, rather than corporate governance

drawn between engaged and disengaged pension funds, the

considerations. These findings are elaborated upon below,

latter being much more prevalent (as indicated by the larger

beginning with Scenario A on the engaged pension funds

circle in Figure 2) and more reliant on external financial

where we explain this behavior through the operating struc-

experts for investment strategy formulation and implemen-

ture of the in-house investment management.

tation. Within Figure 2, the horizontal axis indicates the

engaged and disengaged behavior vis-à-vis investee corpo-

rations, the associated management style, and the specific

actions vis-à-vis investee corporations. The vertical axis

Scenario A: Engaged Pension Funds

illustrates the distinction between engaged and disengaged When it comes to the investment of pension funds, trustees

funds by outlining the respective features of pension fund have the ultimate responsibility for first, establishing the

investment management practice. extent of fund liabilities, then considering the suitability of

Overall, Figure 2 is intended to show that large pension different asset classes for meeting the scheme’s funding

funds with sufficient internal resources and in-house invest- requirements, and finally selecting investment fund manag-

ment management (Scenario A, below) are linked more ers to manage fund investments. Although pension funds

directly with their investee corporations, being able to within our interview sample can be characterized as “large”

exhibit a more engaged ownership stance. The size of pension funds, of all those within the UK top 100 pension

pension fund ownership stake in a corporation and the ethos funds, only two pension funds exhibited engaged owner-

of the fund also inform engagement. By contrast, the major- ship behavior: namely, conducting company research and

ity of pension funds delegate their investment management monitoring, voting and proxy voting, writing letters, and

to external experts (Scenario B, below) and operate at a con- holding face-to-face meetings with senior management

siderable distance from the investee corporations. In exercis- and boards of directors about structural and strategic corpo-

FIGURE 2

Engaged and Disengaged Pension Funds

Engaged Funds Disengaged Funds

Ability & Lack of

Willingness In-house Investment Delegation Ability &

Management Willingness

Delegating voting and all to

Hiring/Firing management

do with engagement to the

Fund manager mandate:

fund manager and focus

primarily on investment

Discipline is exercised

Resolutions/Proposals

Face to face dialogue

Company research &

Voting/Proxy voting

Threats of EGMs

(selling/trading)

Public Tactics

performance.

monitorning

through exit

Letters

Internal Resources Reliance on external expertise

Share Ownership Dependencies along the

investment chain

Pension fund Ethos Influence and focus on

investment performance

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013

172 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

rate governance issues. Even then those pension funds which doesn’t sound much but actually that puts us at the top

respondents gave preference to discussions and routine in most companies, so our level of influence is the strongest in

negotiations “behind the scenes” and cast their behavior in the UK. (Head of Responsible Investment/Occupational

terms of “sophisticated engagement debate” and “trying to create Pension Fund/over £30 billion).

and maintain long-term relationships with the companies.” These

Another pension fund CEO notes that owning large stakes at

pension funds were also investing in specialist corporate

companies allows gaining access to the corporate manage-

governance teams to work in-house and working with exter-

ment, where “the management would take corporate governance

nal industry bodies such as Pensions Investment Research

concerns more seriously and pull in more senior company repre-

Consultants (PIRC), RImetrics or the National Association of

sentatives to those meetings.”

Pension Funds (NAPF).

This study finds that pension fund ethos and trustees’ and

We found that such ownership behavior is explained by

managers’ understandings of their own roles and duties in

pension fund internal resources which underpin in-house

relation to the trust seem to be crucial in the form of engage-

investment management; relatively large ownership stakes

ment adopted. This study finds that actors within more

in corporations; and a pension fund ethos and organiza-

involved pension funds are not only able but also willing to

tional values pursued by trustees and fund executives.

be more engaged. The respondents within this group of

Engaged pension funds with in-house investment manage-

funds argue that involved engagement “makes sense” for two

ment are atypical in the UK pension fund landscape as the

distinct reasons. One underlying motivation behind engage-

following quotations from actors involved in the pension

ment relates to trustees considering that engagement adds

fund industry suggest:

value and produces better financial returns for the pension

We are different in that we do have a little bit more in-house fund. Since better investment performance is in the best

resources and . . . we probably do have more hands on involve- interests of the pension fund members, engagement

ment. Because of our size we take a more direct approach . . . we becomes part of pension fund ethos and trustees’ fiduciary

do see that it is the job of the trustees to influence the compa- duty. In other words, trustees see engagement as part of their

nies. (CEO of an occupational pension fund with over £5 fiduciary duty. A Chief Investment Officer (CIO) of a UK top

billion of assets under management) 5 occupational pension fund with assets under management

exceeding £30 billion explains:

We are probably two of the most active pension funds in terms

of resources for corporate governance within the pension fund We actually follow our corporate governance approach because

itself . . . we are a large pension fund and we have the luxury of we believe that it would lead to better performance and we do the

being able to employ two full-time people to look at these sorts same with our sustainability and responsible investment. We

of issues – some pension funds wouldn’t have the resource and actually believe that over the longer term the companies which

I think that generally resource within corporate governance is a are better governed are likely to outperform those companies that

huge issue – Hermes has a team of 25 people looking at corpo- are not (CIO/Pension Fund/Industry: Education).

rate governance around the word, they can obviously have a

much bigger impact than our team of two could have, so I spent many years meeting UK companies, chairmen of the

resource is a huge issue. (Corporate governance counselor board, promoting better governance because I firmly believe

of a UK top 10 occupational pension fund) that well-governed companies do actually improve long-term

performance of investment funds (Corporate Governance

These few pension funds with in-house investment exper- Counselor/Pension Fund/over £15 billion).

tise have more control over shaping pension fund invest-

ment strategy and investment management. Unlike most The other reason relates to trustees’ personal values and sense

pension schemes that would externalize their investment of altruism and responsibility that resonate with the pension

management from a cost perspective, funds like the Univer- fund ethos of being a responsible owner of shares, providing

sities Superannuation Scheme (USS) are able to either not only capital but also concerned with environmental,

manage the investments internally and/or have specialist social, and governance issues for the greater good of society.

corporate governance teams in-house who engage directly According to a CEO of one occupational pension fund with

with the investee companies. Beyond these funds, the only nearly £14 billion in assets, the pension fund’s mission is:

other example of pension fund “voice” we could find was by

Not just about the money but what the money would buy – the

collective bodies such as NAPF and the Local Authority

quality of life, which is where the social responsibility is. That

Pension Fund Forum (LAPFF) on behalf of a multitude of

is the mission, if I am evangelical about anything it is about

local authority funds.

what the responsibility could lead to – it is that kind of influ-

We found that relatively large share ownership stakes in

ence, rather than the short-termism, that self-individualistic,

companies to be another factor that facilitates ownership

hedge funds – that kind of philosophy (CEO/Pension Fund).

behavior in pension funds. For example, even a stake of .3

percent in a company was considered to be quite substantial, I am a firm believer that there are other things that need to be

providing access into the board arena and enabling these taken into account other than just profit when it comes to

funds to directly voice corporate governance concerns, as a investing money and the pension fund has the biggest pot of

Head of Responsible Investment at the UK top 5 occupa- money in the region (Trustee/Pension Fund/£4 billion).

tional pension fund explains:

Discussions with trustees about their values and motivations

We are a relatively large UK pension fund so our influence in behind engagement suggest that the actions associated with

the UK is roughly between .3–.5% of anything that is listed – engagement are not “alien” or externally imposed by codes

Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013 © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

PENSION FUNDS’ OWNERSHIP 173

such as the Myners Report (2001) or The Stewardship Code adopting higher or lower liability projections has implica-

(2010). Rather engagement is embedded in the investment tions for pension fund asset allocation, exposure to equity

management philosophy and connected to the overall investments, and the terms of the mandate issued to fund

in-house investment decision making. managers. The higher the liability, the greater demand for

In sum, we observe clear and significant connections more funding. It is here that funds may look to the invest-

between pension fund in-house investment management, ment “market” to produce required investment returns. The

i.e., the pension fund size, the presence of internal resources, actuary, then, plays an important role in setting the founda-

the level of expertise, pension fund share ownership, ethos tion for the subsequent investment choices of asset alloca-

and trustees’ values and the level of pension fund involve- tion and fund manager selection by trustees. In respect of

ment with their investee companies. A small minority of the latter, trustees typically call on the advice of another

extremely large pension funds have sufficient internal financial expert: the investment consultant.

resources and willingness to engage in a direct way with Following actuarial advice, the investment consultant

corporations, while the majority of pension funds delegate then plays a crucial role in the next phase of the investment

investment management to external specialists and are sin- process by advising trustees about the appropriate asset

gularly concerned with investment performance rather than allocation mix and by recommending investment fund man-

considerations of ownership and governance. We explain agers. This research found that similar to the actuary, invest-

this alternative scenario (Scenario B) in more detail below. ment consultants consider their role as identifying different

investment alternatives, rather than suggesting specific

investment solutions. Consultants will indicate the advan-

Scenario B: Disengagement and Delegated Fund tages and disadvantages of the alternatives, and let the trust-

Investment Management ees decide the most appropriate course of action. However,

significantly, all interviews with pension fund trustees and

For the majority of pension funds studied, this research

investment experts indicate that, while consultants perceive

found that in making strategic investment decisions, trust-

their role purely as advisory, the trustees for the most part

ees employ the expertise of actuaries, investment consult-

regard the consultant’s advice to be “telling” or directing the

ants, and investment fund managers, typically drawn from

trustee as to what investment strategy to pursue. A pension

outside the fund. Indeed, all pension funds employed actu-

fund trustee illustrated this difference in perception and the

aries and investment advisers from external retirement

significant implications in terms of responsibility as follows:

consultancy firms, and delegated pension fund asset man-

agement to professional investment fund managers. Using The problem [is] . . . I am a trustee, you are a consultant and

Figure 2 and the concept of an investment chain, the follow- you say “I recommend that you do this”, I hear you saying, “I

ing sections show how disengaged pension fund ownership advise you that the best option for you is this” . . . but ulti-

behavior plays out, starting first with an analytical descrip- mately, the buck stops with the trustees, and the Regulator will

tion of how delegation to fund managers occurs and then be asking them questions. If the scheme meets problems further

moving on to explain how dependencies and influences down the line, it is the trustees who will be held to account.

along the investment chain ensure that pension funds focus

Another trustee observed about investment recommenda-

on investment performance rather than matters of corporate

tions: “Recommendation to me has this ring of endorsement about

governance.

it.” We find that trustees’ lack of investment expertise, their

reliance on investment consultants and their perception of

Strategic Investment: Reliance on External Expertise. consultants’ recommendations as “endorsing” in this way,

During the actuarial valuation of pension fund liabilities, have huge implications for pension fund investment strat-

which occurs at least once every three years, an actuary egy, such as investing equity allocations via active invest-

establishes the funding needs of the scheme based on vari- ment fund managers, and focusing fund mandates on

ables such as human longevity, future salary levels, rates of producing short-term investment returns.

inflation, and pension fund investment portfolio perfor- When it comes to relationships between pension funds

mance. Through interviews with actuaries and observation and their investment fund managers, the picture that

of four pension fund investment committee meetings, emerges from the study is that trustees delegate the running

during which pension fund investment strategy was dis- of pension fund investments, and more specifically equity

cussed, we found there to be considerable ambiguity asso- investments, to fund managers. However, fund managers

ciated with actuarial valuation. The ambiguity comes from are only responsible for the obligations set within the man-

the approximate nature of the variables that the actuaries are dates provided by pension fund trustees. Our interviews

working with, since it is difficult to predict future human indicate that this agenda is overwhelmingly oriented

longevity or the rates of return on pension fund invest- towards generating investment performance, rather than

ments. For example, assumptions about the total pension attending to matters of corporate governance.

fund liabilities covered by the Pension Protection Fund, A clear finding from this study is that trustees perceive

range from £834.2 billion to £981.0 billion (The Purple Book, that their “primary fiduciary responsibility is to maximize the

2009). In reality therefore, rather than providing the trustees return to be able to pay the pensions to the members,” which in

with one precise liability calculation, an actuary produces turn means that trustees “leave it to the fund manager to go and

several assumptions, and then highlights the advantages talk to the companies they invest in.” We did find that there is

and disadvantages of each, leaving trustees to decide which an expectation that the fund managers will do “something”

figures to use as a basis for funding fund needs. Accordingly, about the corporate governance of the investee companies,

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013

174 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

but there is no clear prescription within the mandate as to colleagues in the firm. But the dynamic is sometimes difficult.

how to behave in relation to shares and shareholdings, other There is a risk of people becoming a bit lazy about finding

than selling if the investment performance is poor. what’s involved and they rely too much on each other.

A CEO of an occupational pension fund with assets under

A pension fund CEO also intimated that experts may have a

management exceeding £11 billion illustrated this point as

tendency to support each other’s recommendations:

follows:

Consultants have a house view on whether it is appropriate for

What we delegate to our fund managers is “make us money,

pension funds to be in certain asset classes. If the consultants

provide good returns” and what we select our fund managers

have cornered the market and have 70 percent of pension fund

on . . . are people who can pick the right stocks. We ask them to

clients, and if they don’t like hedge funds, they don’t tend to get

vote and they vote, and that means they can tick the corporate

many clients investing in hedge funds . . . we are very con-

governance box. But it is box ticking. And if they don’t like the

scious that they have a house view behind them . . . but what the

way the company is being run, they will do what we all can do,

actuary and the consultants say goes.

which is sell it.

By way of further explanation about how this interdepen-

Making a similar point, albeit from a different role and orga-

dence plays out within pension fund investment, we found

nization, a Head of a Client Accounts Team for a global

that if a consultancy house is specializing in researching

investment manager with assets under management exceed-

(and recommending) particular active or “trading” equity

ing £300 billion, said:

managers, an actuary can support these recommendations

What is surprising on corporate governance is that more clients by producing actuarial valuations of the effects of these asset

aren’t asking more questions. Often corporate governance takes managers on pension scheme’s funding. In so doing, an

a back seat and [our clients] seem quite comfortable devolving actuary would be endorsing the consultant’s advice and

responsibility to us. I am not sure if they ever read what we do on inadvertently “channeling” pension fund equity allocations

their behalf. I go to trustee meetings and I never get asked about via these fund managers.

corporate governance. Trustees are focused on the delivery of Supporting this interview data, examination of actuarial

performance, not the drivers of that performance at the company and investment consultants appointments within the UK

level. What they employ us to do is to implement the strategy top 100 schemes (Pension Funds Online4, http://www.

that they have decided on, that they take the responsibility for. pensionfundsonline.co.uk/, accessed November 2008)

revealed that 45 percent of schemes appoint actuaries and

Furthermore, we found that pension fund trustees reinforce

investment consultants from the same firms. The fact that 45

the short-term investment performance focus by quarterly

pension funds within the UK top 100, and over half of

fund manager performance appraisals and giving incentives

pension funds within this study, are employing consultants

and rewards to fund managers “for outperforming” their

and actuaries from the same firm, suggests that the phenom-

target benchmarks. Unsurprisingly, fund managers focus on

enon of dual appointments is widespread. Coincidentally,

producing short-term investment returns which they pursue

we also document relatively high equity asset allocations

through active stock trading.

within these funds. The average asset allocation to both

domestic and overseas equities at the time of data collection

Dependence along the Investment Chain. Within a exceeded 50 percent. Thirty seven percent of pension funds

chain of investment management relationships we found that employed an actuary and the investment consultant

dependence between actors. Of particular note here is the from the same consultancy house, invested roughly over 55

interdependence between actuaries and investment consult- percent of their assets in equities. One pension fund

ants; investment consultants and the fund managers; and invested almost 100 percent of their assets in equity. These

between fund managers and the investee corporations. We findings indicate that there may be a link between the rela-

explain these dependencies and how they play out in the tionships between an actuary and investment consultant and

pension fund investment process next. trustee focus on investment performance within the fund

Within the relationship between an actuary and an invest- manager mandate.

ment consultant, we found that although an actuary and an Within relationships between investment consultants and

investment consultant provide different expertise and ser- the fund managers, we also found mutual dependence,

vices, their tasks often go “hand in hand,” and the advice which reinforces the short-term investment performance

they provide to trustees is overlapping. All the interviews focus among equity fund managers. Investment consultants

with actuaries and investment consultants indicated that it is rely on investment fund managers and their investment

common practice for both experts to work together on the strategies, to provide a “value-added” service to their

same pension fund client and discuss particular issues from pension fund clients. Significantly, and at the same time, the

different angles. Hence the actuary and the investment con- fund managers depend on consultants for their recommen-

sultant can develop similar views on how to advise the dations and access to prospective pension fund clients. A

trustees on a particular investment issue. This is especially CEO of a local authority pension fund with over £2 billion of

so when both experts work for the same firm, use the same assets under management explained consultants’ depen-

pool of research resources, and have the same “house view” dency on the fund managers in this way:

on investment managers. As an actuary explained:

Consultants have to keep a good relationship with the fund

[Name of the firm] is one of the biggest consultancies and managers because they need the intelligence about all of them to

we have a central pool of expertise, so we share it with our be able to do their job and advise us.

Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013 © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

PENSION FUNDS’ OWNERSHIP 175

A fund manager from a global asset management house All our interviews with investment fund managers indi-

confirmed a dependence on consultants: cated that fund managers see themselves primarily as

“money managers,” whose business model is to maximize a

The dynamics are interesting because most of our business is return against a given benchmark, which is achieved by

brought to us, or introduced to us, by those consultants. They trading shares. For example, when asked about the signifi-

are crucial to the way our business operates and runs . . . con- cance of monitoring and disciplining corporate executives,

sultants are closer to the clients sometimes than we are (Head one Investment Director admitted that he would keep

of Client Account Team/Global Financial Services investing in a company with poor corporate governance

Provider). compliance records, and not challenge the management, as

A pension fund Chief Executive also confirmed that invest- long as it does not affect the performance of the fund. If and

ment consultants are “the gatekeepers” between the pension when it does, he would simply sell the shares. Equally, it was

fund trustees and the investment fund managers, whilst, an felt that the perceived value of the company with higher

Investment Manager highlighted that “investment perfor- corporate governance standards was “really negligible.”

mance becomes a key in trying to keep investment consultants These observations provide a platform to discuss our next

happy and staying on their buy lists.” finding about the relations of influence within the invest-

Within the third set of relationships between the invest- ment chain that further encourage a focus on investment

ment fund managers and corporations, we also observe performance.

dependence (on the fund manager side) and find little

evidence of engaged ownership behavior on behalf of Influence and Focus on Investment Performance. The

pension funds. Among five well-known and reputable preceding sections observed trustee reliance on external

asset-managing houses investigated for this study, only expertise within the process of strategic investment and rela-

one showed evidence of engaging with the investee com- tional interdependencies between actors along the invest-

panies on corporate governance matters, ranging from ment chain that links pension funds to corporations. This

executive remuneration, board structure and indepen- section builds on these findings by examining the influence

dence, combined roles of CEO and Chairman and the dynamics between trustees and other actors within the

overall strategic direction of the company – and even that pension fund investment chain, which encourages trustees

engagement was said to have “had very little influence” on to focus on investment performance within fund manager

corporate practices. We found that even those investment mandates, in keeping with, and achieved through, the share-

fund managers who may be in a position to monitor trading activities of the fund managers. The effects of the

and discipline the corporate executives, because of their external influence can be seen in several stages of the

vast internal resources and the size of the stakes they pension fund investment process.

hold in these companies, tend to keep their distance, for a During the actuarial valuation there are several opportu-

number of reasons. Firstly, a lot of significance is given nities when an actuary can influence the trustees to

to maintaining “good relationships” with the company (over)rely on the market, and focus the investment fund

executives. The fund managers are dependent on these manager mandates on investment performance to help

very executives for information that help develop their address pension fund deficits. The situation is most evident

stock trading models and make buy-and-sell decisions. A in the case of Occupational Funds wherein an actuary who

Head of Client Accounts Team for a fund manager represents both the employer and the pension fund faces

explained: employer pressure to recommend lower employer contribu-

tions to the fund. This may inadvertently influence the trust-

A lot of managers go along with the executives . . . they want to ees to rely more on the market and investment performance

have good relationships with these senior execs because that is of the active fund managers, for fund growth. An actuary

the source of information to help them with making buy/sell from a leading UK retirement consultancy house explained

decisions. And so they don’t push . . . they are not incentivized the nature of actuarial influence:

to do it at the moment.

Essentially, to provide the pension scheme benefits, the money

When meetings between fund managers and corporate has either got to come from the company, or from investment

executives do happen, they are focused on obtaining (more returns. The idea is that equities would strike a fair balance

subjective) information, which would indicate managerial between the two. The employer may request that trustees invest

ability to deliver what has been agreed in terms of corporate more in equities . . . it’s very rare for the company not to have

strategy rather than engaging with the executives on issues influence into actuarial valuation, because it directly affects

of corporate governance, such as code compliance. An how much money the company is going to pay into the scheme

Investment Fund Manager managing over £4 billion in over the next 5 or 10 years.

assets reflected on the nature of their meetings with

company executives by saying that: Accordingly, faced with balancing both the long-term needs

of the fund and the short-term costs to the employer, an

It comes down to the relationship. What we are looking for is to actuary may set the trustees on the course of investing more

understand the change which we think is going to take place. “in the market” to compensate for lower employer contribu-

It’s crucial that we believe that the management can deliver, so tions. Documentary analysis and the observations of

we’d go to a meeting and try to get that information. It’s a actuarial presentations during the investment committee

question of keeping a relationship going with the management. meetings also revealed that by presenting assumptions with

If we lose faith in the management, we just sell it. equity investment returns, an actuary indicates to the trustees

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013

176 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

that pension fund income and funding level can be higher Consultants’ advice is not objective, because they are after a fee

than in the scenario where the actuarial assumptions are income. There is not enough long-term thinking within the

calculated without the investment returns. Contrasting managers and trustees, and that is partly a fault of the consult-

funding scenarios send a powerful signal to the trustees to ants, because they are getting paid to do something, analyse the

focus their investment strategy on asset allocation, and to managers, make recommendations – and that tends to create

pick fund managers who can outperform the market. In short, short-term thinking and pressures – and that is the problem.

an actuary also implicitly encourages the trustees to link their

Furthermore, the evidence from all pension fund inter-

investment aims with the stock-picking abilities of the equity

viewees, as well as the accounts of the investment fund

fund managers. This also sets the tone for how the investment

managers, indicated that because consultants act at the inter-

consultant approaches the task of advising the trustees.

face between trustees and the investment industry, the fund

In establishing the appropriate asset allocation mix, and

managers are under pressure to produce short-term invest-

selecting investment fund managers, we found that, despite

ment returns through “portfolio churning,” in order to be

the concerns of the Myners Report (2001), investment con-

able to obtain and sustain a place on consultants’ recommen-

sultants have significant influence over the formulation of

dation lists and thus access the pension fund clients. More-

pension fund investment strategy, and subsequently how

over, the rivalry between investment fund managers for

the pension fund equity investments are being managed on

pension fund business also encourages these managers to

behalf of pension funds. Although trustees have the legal

“trade” in order to generate more investment income and be

power and responsibility to make strategic investment deci-

more competitive.

sions, much of the influence within the investment strategy

Guided by the pressing need to fill in the pension fund

still lies with the expertise of a small number of investment

deficits, trustees, actuaries, and consultants are all primarily

consultants, like Mercer, Watson Wyatt (currently Tower

focused on investment performance and delivery of bench-

Watson), Hewitt and Hymans, who dominate the industry.

marks, and trustees actively intensify this focus on invest-

Interviewees’ perceptions about investment consultants’

ment performance through quarterly fund manager

influence and significance is mirrored almost identically

appraisals. What do our findings mean for the broader own-

in the same order of mention within the Actuaries,

ership and control debates? We discuss the theoretical and

Pension Funds Consultants & Investment Advisers

policy implications next.

League Table 2010 (Pension Funds Online, http://www.

pensionfundsonline.co.uk/, accessed June 2010). The

sources of consultants’ power include vast specialized DISCUSSION

research and investment analysis capabilities, good connec-

tions within the investment community, and the lack of Within the governance literature about ownership and

investment expertise within pension funds. control, the relationship between corporate management

Interviews with pension fund trustees and chief execu- and institutional investors has been traditionally conceptu-

tives as well as investment advisers, indicated that it is the alized in terms of a relationship between agents and princi-

investment consultants who provide “the leadership,” “put pals, the underlying agency rationale being that there is an

things on the agenda,” “choose the issues” within pension incentive for institutional investors to engage with firms and

funds’ investment strategy, and decide what the pension the incumbent management in order to ensure managerial

fund clients “want” and what the fund managers “should accountability (Anabtawi, 2006; David et al., 2001; Gillian &

sell.” A trustee of an industry-wide pension fund with assets Starks, 2000; Hoskisson et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2010;

under management exceeding £3 billion and a Director of Mallin, 1994).

one of the UK’s civil society organizations, aimed at encour- Empirically, we found limited evidence to suggest that

aging responsible investment among pension funds, pension funds behave in a way that supports this theoretical

explained how this happens: argument. Although we document a variation in pension

fund behavior vis-à-vis investee corporations where a very

Trustees aren’t sure what to do, they feel they need to trust

small number of well-resourced and internally managed

somebody, and they trust their investment consultant. As a

pension funds are willing and able to express “voice” (Hir-

result, trustees end up being advised into investment strate-

schman, 1970) and exhibit ownership behavior, these funds

gies, which are complex, putting not enough emphasis on asset

are an exception rather than the norm. Rather, our findings

allocation, and far too much emphasis on stock picking by active

support the view that despite theoretical ideals, the owner-

fund managers.

ship behavior of institutional investors is more assumed

This in turn encourages a “trading” mentality among the than demonstrated. Consistent with Davis (2008, 2009) and

fund managers. Jackson (2008), this study reveals that there is very little

The interviews with pension fund trustees, chief execu- evidence to suggest that pension funds and their financial

tives and chief investment officers all suggest that consult- intermediaries, such as investment fund managers, see them-

ants play a significant role in determining pension fund selves as principals and act as engaged share owners. Rather

asset allocation and fund manager selection, biasing pension the vast majority of pension funds operate at a distance from

fund investment strategy towards the short-term return for their investee corporations. These funds exhibit “exit” own-

the fund. By way of motives, interviewees suggest that this is ership behavior (Hirschman, 1970) and conduct their invest-

because consultants are financially gaining from the provi- ment strategy through a chain of relationships involving

sion of such advice. A CIO of one of the UK’s top 5 pension actuaries, investment consultants, investment managers, and

funds highlighted that: corporations. By examining pension fund investment prac-

Volume 21 Number 2 March 2013 © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

PENSION FUNDS’ OWNERSHIP 177

tice and how it informs pension fund ownership behavior, In the context of agency theory, we are able to offer expla-

this study illuminates something of what Pye (2001), Hendry nations to the “theoretically puzzling” ownership paradox

et al. (2006), and Roberts et al. (2006) identified as the little (Davis, 2008) – an ownership alarmingly absent of any sig-

explored multi-layered agency relationships that link firms, nificant stewardship responsibility – this despite enthusias-

their managers and suppliers of capital. tic regulatory and other policy encouragements. The

Operating with high dependence on external experts, findings of this study suggest an empirical reality that is

pension funds’ investment practices are shown to be laced more complex than the dyadic principal/agent or owner/

with interests and influence which ensure that pension fiduciary conceptualization of the investor/company rela-

funds give primary emphasis to fund investment perfor- tionship. This study identifies a disconnect between the

mance rather than matters of corporate governance. Further- beneficiaries of investment and the activities through which

more, the lines of responsibility and accountability between their money is invested. This disconnect is rooted in distinc-

the actors within the investment chain are loose, perhaps tions between the actual share owners (pension fund benefi-

even confused. Although the trustees have the fiduciary ciaries), the institutions that hold shares (pension funds), the

responsibility to decide the investment strategy, hampered institutions that provide investment expertise services (actu-

by personal liability concerns, trustees draw on the expertise aries and investment consultants), and those institutions

of the actuaries and investment consultants and give the that actually manage the stocks (investment fund managers).

responsibility for the execution of the investment strategy, The complexity and the interdependencies between these

particularly equities management, to their investment fund actors provide a new focus on the content of corporate own-

managers. However, unlike trustees, the external experts ership and control, which should be taken into account. This

have only limited accountability for their effects. For study therefore has very significant implications for corpo-

example, if the investment strategy does not yield the rate governance research in that it identifies the need for new

expected results due to an investment adviser’s poor choice theory building, so as to develop more appropriate ways of

of asset allocation options, or if a pension fund loses a sig- understanding and analyzing the current and emerging