Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How We Know Whether and When To Pay Attention

How We Know Whether and When To Pay Attention

Uploaded by

Fred PascuaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- q4 Shs EAPP - q2 - Mod1 - Arguments in ManifestoesDocument26 pagesq4 Shs EAPP - q2 - Mod1 - Arguments in Manifestoesלארה מאי100% (4)

- Experiment 2 Kinematics of Human MotionDocument8 pagesExperiment 2 Kinematics of Human MotionAldrin Agawin50% (2)

- Log Book (Science Investigatory Project)Document70 pagesLog Book (Science Investigatory Project)norilyn fonte100% (1)

- Prediction, Cognition and The BrainDocument15 pagesPrediction, Cognition and The BrainMichael HamoudiNo ratings yet

- Pressentiment SensorielDocument12 pagesPressentiment SensorielPatriceNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 06 00147Document19 pagesFnhum 06 00147Bruno Saboya de AragãoNo ratings yet

- Journal Pbio 3002195Document23 pagesJournal Pbio 3002195philosophos1No ratings yet

- A Dual Role For Prediction Error inDocument11 pagesA Dual Role For Prediction Error inmiguel.amendozaNo ratings yet

- Perceiving Patterns in Random Series: Dynamic Processing of Sequence in Prefrontal CortexDocument6 pagesPerceiving Patterns in Random Series: Dynamic Processing of Sequence in Prefrontal CortexEdward Ventura BarrientosNo ratings yet

- PhysicsEssays Radin DoubleSlit 2012Document15 pagesPhysicsEssays Radin DoubleSlit 2012Anca AngheleaNo ratings yet

- Regularity Detection Under StressDocument20 pagesRegularity Detection Under StresszakfosNo ratings yet

- Mingdi Xu, Satoshi Morimoto, Eiichi Hoshino, Kenji Suzuki, and Yasuyo MinagawaDocument15 pagesMingdi Xu, Satoshi Morimoto, Eiichi Hoshino, Kenji Suzuki, and Yasuyo MinagawajaimesampaioNo ratings yet

- AI & ML in AnesthesiaDocument24 pagesAI & ML in AnesthesiaSana HashemiNo ratings yet

- A Brain Network Supporting Social Influences in Human Decision-Making - Lei Zhang, Jan GläscherDocument20 pagesA Brain Network Supporting Social Influences in Human Decision-Making - Lei Zhang, Jan GläscherGustavo ZukowskiNo ratings yet

- HeartMath Inuition StudyDocument12 pagesHeartMath Inuition StudyAdrian AlecuNo ratings yet

- Lectura 1. Contextual CognitionDocument27 pagesLectura 1. Contextual CognitionManuel Guerrero GómezNo ratings yet

- The Multiphasic Model of Precognition. The RationaleDocument15 pagesThe Multiphasic Model of Precognition. The Rationalemauricio gómezNo ratings yet

- Human Eye Research PaperDocument5 pagesHuman Eye Research Paperaflefvsva100% (1)

- Articulo Lisa FeldmanDocument28 pagesArticulo Lisa FeldmanLaia Colom BertrånNo ratings yet

- Exploring Global ConsciousnessDocument25 pagesExploring Global ConsciousnessManuel MeglioNo ratings yet

- M.A. Proposal - FinalDocument22 pagesM.A. Proposal - FinalSityhilelo GwenxaneNo ratings yet

- Brainsci PisicoDocument9 pagesBrainsci PisicoJairo BalcazarNo ratings yet

- Journal Pcbi 1010490Document27 pagesJournal Pcbi 1010490Ahmed Karam EldalyNo ratings yet

- Raymond Trevor Bradley - The Psychophysiology of Intuition: A Quantum-Holographic Theory of Nonlocal CommunicationDocument38 pagesRaymond Trevor Bradley - The Psychophysiology of Intuition: A Quantum-Holographic Theory of Nonlocal CommunicationDominos021100% (1)

- UntitledDocument50 pagesUntitledCharles LenayNo ratings yet

- Nonlinear Dynamics of The Brain: Emotion and Cognition: Home Search Collections Journals About Contact Us My IopscienceDocument17 pagesNonlinear Dynamics of The Brain: Emotion and Cognition: Home Search Collections Journals About Contact Us My Iopsciencebrinkman94No ratings yet

- 2018 - Attent Models - Garrido+Document12 pages2018 - Attent Models - Garrido+K JaneNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 10 00077Document14 pagesFnhum 10 00077RavennaNo ratings yet

- (Gabriel A. Radvansky, Jeffrey M. Zacks) Event Cog (Z-Lib - Org) - 3Document25 pages(Gabriel A. Radvansky, Jeffrey M. Zacks) Event Cog (Z-Lib - Org) - 3Judy Costanza BeltránNo ratings yet

- Develop Med Child Neuro - 2016 - Cioni - Early Intervention in Neurodevelopmental Disorders Underlying Neural Mechanisms PDFDocument6 pagesDevelop Med Child Neuro - 2016 - Cioni - Early Intervention in Neurodevelopmental Disorders Underlying Neural Mechanisms PDFRenan MelloNo ratings yet

- The Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: Anil K. SethDocument51 pagesThe Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: Anil K. SethDarkwispNo ratings yet

- Neurociencia y ArquitecturaDocument23 pagesNeurociencia y ArquitecturaIsabelRosasMartindelCampoNo ratings yet

- Intuition Part1Document12 pagesIntuition Part1Luis Alberto Rebaza DominguezNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 04 00146Document8 pagesFpsyt 04 00146Andres RojasNo ratings yet

- A New EarthDocument13 pagesA New Earthnavuru5kNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 10 00694Document14 pagesFnhum 10 00694Nelson Alex Lavandero PeñaNo ratings yet

- How Do Expectations Shape Perception?: ReviewDocument16 pagesHow Do Expectations Shape Perception?: ReviewIgnacio DuqueNo ratings yet

- Expectations Shapes PerceptionDocument16 pagesExpectations Shapes PerceptionIgnacio DuqueNo ratings yet

- Brenda J. Dunne and Robert G. Jahn - Consciousness and Anomalous Physical PhenomenaDocument31 pagesBrenda J. Dunne and Robert G. Jahn - Consciousness and Anomalous Physical PhenomenaCanola_OliveNo ratings yet

- Shen Et Al. - 2017 - Using Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling To PredDocument27 pagesShen Et Al. - 2017 - Using Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling To PredfacepalmerNo ratings yet

- Homeconditionsquizzesnews & Expertsresearch & Resourcesfind HelpDocument5 pagesHomeconditionsquizzesnews & Expertsresearch & Resourcesfind HelpelmaNo ratings yet

- Embodiment and Schizophrenia - A Review of Implications and Applications - 2017Document9 pagesEmbodiment and Schizophrenia - A Review of Implications and Applications - 2017Pedro Gabriel LorencettiNo ratings yet

- Control The Impulse To Theow The Baby Out With The BathwaterDocument16 pagesControl The Impulse To Theow The Baby Out With The Bathwatertitan dioxideNo ratings yet

- NATUREDocument12 pagesNATUREGuadalupe BerbigierNo ratings yet

- Article Review Memory FingerprintsDocument7 pagesArticle Review Memory FingerprintsСветлана100% (1)

- Towards An Empirically Grounded Predictive Coding Account of Action UnderstandingDocument3 pagesTowards An Empirically Grounded Predictive Coding Account of Action UnderstandingAlan HartogNo ratings yet

- Sensory Information and The Development of CognitionDocument3 pagesSensory Information and The Development of CognitionInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Electrophysiological Evidence of Intuition: Part 1. The Surprising Role of The HeartDocument11 pagesElectrophysiological Evidence of Intuition: Part 1. The Surprising Role of The Heartalxzndr__No ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument50 pagesIntroductionMathumithaa karthikeyanNo ratings yet

- Ultrastructural Analysis of Neuroinflammation: Program SupportedDocument2 pagesUltrastructural Analysis of Neuroinflammation: Program SupportedAriel HananyaNo ratings yet

- Materials and MethodsDocument4 pagesMaterials and Methodsapi-253909330No ratings yet

- Neural Computations of Threat PDFDocument39 pagesNeural Computations of Threat PDFMerly Jimenez HuallancaNo ratings yet

- ConsScale A Plausible Test For Machine ConsciousnessDocument9 pagesConsScale A Plausible Test For Machine ConsciousnessFiuttenNo ratings yet

- The GCP Event Experiment: Design, Analytical Methods, ResultsDocument23 pagesThe GCP Event Experiment: Design, Analytical Methods, ResultsrdnelsongcpNo ratings yet

- Vagnoni Et Al-2015-European Journal of Neuroscience PDFDocument13 pagesVagnoni Et Al-2015-European Journal of Neuroscience PDFmysticmdNo ratings yet

- Embodied Prediction PDFDocument21 pagesEmbodied Prediction PDFmaria19854No ratings yet

- Smallwood 2009Document8 pagesSmallwood 2009NATALIA DE OLIVEIRA KUHNNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 371Document80 pages2017 Article 371AmirJabriNo ratings yet

- Aschwin de Wolf's Review of "Connectome," by Sebastian SeungDocument2 pagesAschwin de Wolf's Review of "Connectome," by Sebastian SeungadvancedatheistNo ratings yet

- Hans Op de Beeck, Chie Nakatani - Introduction To Human Neuroimaging (Cambridge Fundamentals of Neuroscience in Psychology) (2019, Cambridge University Press) - Libgen - LiDocument808 pagesHans Op de Beeck, Chie Nakatani - Introduction To Human Neuroimaging (Cambridge Fundamentals of Neuroscience in Psychology) (2019, Cambridge University Press) - Libgen - LiRAMONA PAVELNo ratings yet

- Neurosciences in CriminologyDocument7 pagesNeurosciences in Criminologycristina andreu nicuesaNo ratings yet

- Consciousness Quantum TheoryDocument12 pagesConsciousness Quantum TheoryMokhtar MohdNo ratings yet

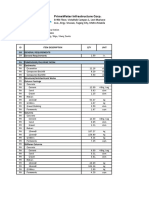

- Kaong PS, Silang Construction Drawings 11june2021-1-11Document11 pagesKaong PS, Silang Construction Drawings 11june2021-1-11Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Biga PS Silang, Boq 11jun2021Document9 pagesBiga PS Silang, Boq 11jun2021Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Kaong PS, Silang, Boq 11jun2021Document11 pagesKaong PS, Silang, Boq 11jun2021Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- EAPP - q2 - Mod8 - Write Various Reports On SurveysDocument24 pagesEAPP - q2 - Mod8 - Write Various Reports On SurveysFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Scientists Discover A New Class of Memory Cells For Remembering FacesDocument2 pagesScientists Discover A New Class of Memory Cells For Remembering FacesFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Genetic Effects of Chernobyl Radiation: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesGenetic Effects of Chernobyl Radiation: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- What Happened To Mars's Water? It Is Still Trapped There: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesWhat Happened To Mars's Water? It Is Still Trapped There: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Why Our Brains Miss Opportunities To Improve Through SubtractionDocument2 pagesWhy Our Brains Miss Opportunities To Improve Through SubtractionFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Video Games Can Change Your BrainDocument2 pagesVideo Games Can Change Your BrainFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Open-Label Placebo Works As Well As Double-Blind Placebo in Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument2 pagesOpen-Label Placebo Works As Well As Double-Blind Placebo in Irritable Bowel SyndromeFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Among COVID-19 Survivors, An Increased Risk of Death, Serious IllnessDocument2 pagesAmong COVID-19 Survivors, An Increased Risk of Death, Serious IllnessFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Multivitamins, Omega-3, Probiotics, Vitamin D May Lessen Risk of Positive COVID-19 TestDocument2 pagesMultivitamins, Omega-3, Probiotics, Vitamin D May Lessen Risk of Positive COVID-19 TestFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Wisdom, Loneliness and Your Intestinal Multitude: Full StoryDocument2 pagesWisdom, Loneliness and Your Intestinal Multitude: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Astronomers Release New All-Sky Map of Milky Way's Outer ReachesDocument2 pagesAstronomers Release New All-Sky Map of Milky Way's Outer ReachesFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- People Affected by COVID-19 Are Being Nicer To Machines: Full StoryDocument2 pagesPeople Affected by COVID-19 Are Being Nicer To Machines: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- New Super-Earth Detected Orbiting A Red Dwarf Star: April 16, 2021Document2 pagesNew Super-Earth Detected Orbiting A Red Dwarf Star: April 16, 2021Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Evidence of AntarcticDocument3 pagesEvidence of AntarcticFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Automated Product Picks ExploredDocument2 pagesAutomated Product Picks ExploredFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- 50-Million-Year-Old Sea Creatures Had A Leg Up On BreathingDocument3 pages50-Million-Year-Old Sea Creatures Had A Leg Up On BreathingFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Eye Color Genetics Not So Simple, Study Finds: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesEye Color Genetics Not So Simple, Study Finds: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- How Hummingbirds Hum: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesHow Hummingbirds Hum: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Experts Recreate A Mechanical Cosmos For The World's First ComputerDocument2 pagesExperts Recreate A Mechanical Cosmos For The World's First ComputerFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Lizard Skull Fossil Is New and 'Perplexing' Extinct Species: Full StoryDocument2 pagesLizard Skull Fossil Is New and 'Perplexing' Extinct Species: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Neanderthals Had The Capacity To Perceive and Produce Human SpeechDocument2 pagesNeanderthals Had The Capacity To Perceive and Produce Human SpeechFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- How Did Dogs Get To The Americas? An Ancient Bone Fragment Holds CluesDocument2 pagesHow Did Dogs Get To The Americas? An Ancient Bone Fragment Holds CluesFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Origin of Life: The Chicken-And-Egg Problem: Date: Source: SummaryDocument3 pagesOrigin of Life: The Chicken-And-Egg Problem: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- 'Space Hurricane' in Earth's Upper Atmosphere Discovered: Analysis Reveals Swirling Mass of Plasma Above The North PoleDocument2 pages'Space Hurricane' in Earth's Upper Atmosphere Discovered: Analysis Reveals Swirling Mass of Plasma Above The North PoleFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Secrets of Sealed 17th Century Letters Revealed by Dental X-Ray ScannersDocument2 pagesSecrets of Sealed 17th Century Letters Revealed by Dental X-Ray ScannersFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Extinct Monitor Lizard Had Four Eyes, Fossil Evidence Shows: Full StoryDocument2 pagesExtinct Monitor Lizard Had Four Eyes, Fossil Evidence Shows: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- ABA Exam Study GuideDocument12 pagesABA Exam Study GuideTaylorNo ratings yet

- Nano Satellite Separation Experiment Using A P-POD Deployment MechanismDocument37 pagesNano Satellite Separation Experiment Using A P-POD Deployment MechanismJawhni DepNo ratings yet

- Experiment: 1 OverviewDocument7 pagesExperiment: 1 OverviewKashifChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Intelligent Data Analysis For Conservation: Experiments With Rhino Horn Fingerprint IdentificationDocument8 pagesIntelligent Data Analysis For Conservation: Experiments With Rhino Horn Fingerprint IdentificationSahar HafiziNo ratings yet

- Principles of Marketing - MGT301 Power Point Slides Lecture 12Document38 pagesPrinciples of Marketing - MGT301 Power Point Slides Lecture 12Ahmed RaXaNo ratings yet

- 1 - KSU Research Methodology Overview (A Mandil, Oct 2009)Document25 pages1 - KSU Research Methodology Overview (A Mandil, Oct 2009)Fatamii IiiNo ratings yet

- Lab Report FormatDocument7 pagesLab Report FormatAmir NaqueddenNo ratings yet

- Positive Pressure Breathing During Rest and Exercise: E.A. Den Hartog, R. HeusDocument10 pagesPositive Pressure Breathing During Rest and Exercise: E.A. Den Hartog, R. HeusAlex CastilloNo ratings yet

- Ess InternalDocument5 pagesEss InternalSAHARE CANO BADWAM-AlumnoNo ratings yet

- E177 13 Standard Practice For Use of The Terms Precision and Bias in ASTM Test MethodsDocument10 pagesE177 13 Standard Practice For Use of The Terms Precision and Bias in ASTM Test MethodsRaine HopeNo ratings yet

- Eapp HandoutsDocument8 pagesEapp HandoutsJo PinedaNo ratings yet

- Uma Sekaran Solution ManualDocument31 pagesUma Sekaran Solution ManualMohamad Rizal50% (2)

- ME156P Salvado EXP 1Document10 pagesME156P Salvado EXP 1John Henry SalvadoNo ratings yet

- Year 8 Lesson Plan - The Two Main Types of EnergyDocument4 pagesYear 8 Lesson Plan - The Two Main Types of Energy4357 Cristal Argelis Liu ZhuoNo ratings yet

- JONES, David - in Conversation With Bruno Latour, Historiography of Science in ActionDocument20 pagesJONES, David - in Conversation With Bruno Latour, Historiography of Science in ActionGaby CepedaNo ratings yet

- The Nature and Extent of CrimeDocument10 pagesThe Nature and Extent of CrimeRm AnimNo ratings yet

- Scientific ResearchDocument2 pagesScientific ResearchLenz BautistaNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics in Engineering - Lecture Notes, Study Material and Important Questions, AnswersDocument4 pagesProfessional Ethics in Engineering - Lecture Notes, Study Material and Important Questions, AnswersM.V. TVNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 TestDocument4 pagesPractical Research 2 TestLen MayNo ratings yet

- LE6 FinalDocument8 pagesLE6 FinalROWELL GALABAYNo ratings yet

- Parts of The Science Investigatory ProjectDocument4 pagesParts of The Science Investigatory ProjectIresh VelanoNo ratings yet

- Applications of Response Surface Methodology in The Food Industry ProcessesDocument21 pagesApplications of Response Surface Methodology in The Food Industry ProcessesFlorentina BucurNo ratings yet

- Effect of Core Stability Training On Dynamic Strength Among College Male StudentsDocument2 pagesEffect of Core Stability Training On Dynamic Strength Among College Male StudentsAlaguraja KNo ratings yet

- RSCH-121 Weeek 1-20Document34 pagesRSCH-121 Weeek 1-20Son Gohan100% (2)

- Lesson 11 Research MethodologyDocument17 pagesLesson 11 Research MethodologyNhaaaNo ratings yet

- Time Is Money-Time Pressure, Incentives, and The Quality of Decision-MakingDocument18 pagesTime Is Money-Time Pressure, Incentives, and The Quality of Decision-Makingpaulo macedoNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology BY VENKATESHDocument128 pagesResearch Methodology BY VENKATESHAnkitaNo ratings yet

- LRP Grade6 Model2 English.Document19 pagesLRP Grade6 Model2 English.Preeta VisanthNo ratings yet

How We Know Whether and When To Pay Attention

How We Know Whether and When To Pay Attention

Uploaded by

Fred PascuaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How We Know Whether and When To Pay Attention

How We Know Whether and When To Pay Attention

Uploaded by

Fred PascuaCopyright:

Available Formats

How we know whether and when to pay attention

Fast reactions are based on estimates of whether and when events will

occur

Date:

April 22, 2021

Source:

Max-Planck-Gesellschaft

Summary:

International team of researchers identifies cognitive computations underlying human

predictive behavior.

Share:

FULL STORY

Fast reactions to future events are crucial. A boxer, for example, needs to

respond to her opponent in fractions of a second in order to anticipate and

block the next attack. Such rapid responses are based on estimates of

whether and when events will occur. Now, scientists from the Max Planck

Institute for Empirical Aesthetics (MPIEA) and New York University (NYU)

have identified the cognitive computations underlying this complex predictive

behavior.

How does the brain know when to pay attention? Every future event carries two distinct kinds of

uncertainty: Whether it will happen within a given time span, and if so, when it will likely occur. Until

now, most research on temporal prediction has assumed that the probability of whether an event will

occur has a stable effect on anticipation over time. However, this assumption has not been

empirically proven. Furthermore, it is unknown how the human brain combines the probabilities of

whether and when a future event will occur.

An international team of researchers from MPIEA and NYU has now investigated how these two

different sources of uncertainty affect human anticipatory behavior. Using a simple but elegant

experiment, they systematically manipulated the probabilities of whether and when sensory events

will occur and analyzed human reaction time behavior. In their recent article in the

journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the team reports two novel

results. First, the probability of whether an event will occur has a highly dynamic effect on

anticipation over time. Second, the brain's estimations of whether and when an event will occur take

place independently.

"Our experiment taps into the basic ways we use probability in everyday life, for example when

driving our car," explains Matthias Grabenhorst of the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics.

"When approaching a railroad crossing, the probability of the gates closing determines our overall

readiness to hit the brakes. This is intuitive and known."

You might also like

- q4 Shs EAPP - q2 - Mod1 - Arguments in ManifestoesDocument26 pagesq4 Shs EAPP - q2 - Mod1 - Arguments in Manifestoesלארה מאי100% (4)

- Experiment 2 Kinematics of Human MotionDocument8 pagesExperiment 2 Kinematics of Human MotionAldrin Agawin50% (2)

- Log Book (Science Investigatory Project)Document70 pagesLog Book (Science Investigatory Project)norilyn fonte100% (1)

- Prediction, Cognition and The BrainDocument15 pagesPrediction, Cognition and The BrainMichael HamoudiNo ratings yet

- Pressentiment SensorielDocument12 pagesPressentiment SensorielPatriceNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 06 00147Document19 pagesFnhum 06 00147Bruno Saboya de AragãoNo ratings yet

- Journal Pbio 3002195Document23 pagesJournal Pbio 3002195philosophos1No ratings yet

- A Dual Role For Prediction Error inDocument11 pagesA Dual Role For Prediction Error inmiguel.amendozaNo ratings yet

- Perceiving Patterns in Random Series: Dynamic Processing of Sequence in Prefrontal CortexDocument6 pagesPerceiving Patterns in Random Series: Dynamic Processing of Sequence in Prefrontal CortexEdward Ventura BarrientosNo ratings yet

- PhysicsEssays Radin DoubleSlit 2012Document15 pagesPhysicsEssays Radin DoubleSlit 2012Anca AngheleaNo ratings yet

- Regularity Detection Under StressDocument20 pagesRegularity Detection Under StresszakfosNo ratings yet

- Mingdi Xu, Satoshi Morimoto, Eiichi Hoshino, Kenji Suzuki, and Yasuyo MinagawaDocument15 pagesMingdi Xu, Satoshi Morimoto, Eiichi Hoshino, Kenji Suzuki, and Yasuyo MinagawajaimesampaioNo ratings yet

- AI & ML in AnesthesiaDocument24 pagesAI & ML in AnesthesiaSana HashemiNo ratings yet

- A Brain Network Supporting Social Influences in Human Decision-Making - Lei Zhang, Jan GläscherDocument20 pagesA Brain Network Supporting Social Influences in Human Decision-Making - Lei Zhang, Jan GläscherGustavo ZukowskiNo ratings yet

- HeartMath Inuition StudyDocument12 pagesHeartMath Inuition StudyAdrian AlecuNo ratings yet

- Lectura 1. Contextual CognitionDocument27 pagesLectura 1. Contextual CognitionManuel Guerrero GómezNo ratings yet

- The Multiphasic Model of Precognition. The RationaleDocument15 pagesThe Multiphasic Model of Precognition. The Rationalemauricio gómezNo ratings yet

- Human Eye Research PaperDocument5 pagesHuman Eye Research Paperaflefvsva100% (1)

- Articulo Lisa FeldmanDocument28 pagesArticulo Lisa FeldmanLaia Colom BertrånNo ratings yet

- Exploring Global ConsciousnessDocument25 pagesExploring Global ConsciousnessManuel MeglioNo ratings yet

- M.A. Proposal - FinalDocument22 pagesM.A. Proposal - FinalSityhilelo GwenxaneNo ratings yet

- Brainsci PisicoDocument9 pagesBrainsci PisicoJairo BalcazarNo ratings yet

- Journal Pcbi 1010490Document27 pagesJournal Pcbi 1010490Ahmed Karam EldalyNo ratings yet

- Raymond Trevor Bradley - The Psychophysiology of Intuition: A Quantum-Holographic Theory of Nonlocal CommunicationDocument38 pagesRaymond Trevor Bradley - The Psychophysiology of Intuition: A Quantum-Holographic Theory of Nonlocal CommunicationDominos021100% (1)

- UntitledDocument50 pagesUntitledCharles LenayNo ratings yet

- Nonlinear Dynamics of The Brain: Emotion and Cognition: Home Search Collections Journals About Contact Us My IopscienceDocument17 pagesNonlinear Dynamics of The Brain: Emotion and Cognition: Home Search Collections Journals About Contact Us My Iopsciencebrinkman94No ratings yet

- 2018 - Attent Models - Garrido+Document12 pages2018 - Attent Models - Garrido+K JaneNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 10 00077Document14 pagesFnhum 10 00077RavennaNo ratings yet

- (Gabriel A. Radvansky, Jeffrey M. Zacks) Event Cog (Z-Lib - Org) - 3Document25 pages(Gabriel A. Radvansky, Jeffrey M. Zacks) Event Cog (Z-Lib - Org) - 3Judy Costanza BeltránNo ratings yet

- Develop Med Child Neuro - 2016 - Cioni - Early Intervention in Neurodevelopmental Disorders Underlying Neural Mechanisms PDFDocument6 pagesDevelop Med Child Neuro - 2016 - Cioni - Early Intervention in Neurodevelopmental Disorders Underlying Neural Mechanisms PDFRenan MelloNo ratings yet

- The Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: Anil K. SethDocument51 pagesThe Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: Anil K. SethDarkwispNo ratings yet

- Neurociencia y ArquitecturaDocument23 pagesNeurociencia y ArquitecturaIsabelRosasMartindelCampoNo ratings yet

- Intuition Part1Document12 pagesIntuition Part1Luis Alberto Rebaza DominguezNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 04 00146Document8 pagesFpsyt 04 00146Andres RojasNo ratings yet

- A New EarthDocument13 pagesA New Earthnavuru5kNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 10 00694Document14 pagesFnhum 10 00694Nelson Alex Lavandero PeñaNo ratings yet

- How Do Expectations Shape Perception?: ReviewDocument16 pagesHow Do Expectations Shape Perception?: ReviewIgnacio DuqueNo ratings yet

- Expectations Shapes PerceptionDocument16 pagesExpectations Shapes PerceptionIgnacio DuqueNo ratings yet

- Brenda J. Dunne and Robert G. Jahn - Consciousness and Anomalous Physical PhenomenaDocument31 pagesBrenda J. Dunne and Robert G. Jahn - Consciousness and Anomalous Physical PhenomenaCanola_OliveNo ratings yet

- Shen Et Al. - 2017 - Using Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling To PredDocument27 pagesShen Et Al. - 2017 - Using Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling To PredfacepalmerNo ratings yet

- Homeconditionsquizzesnews & Expertsresearch & Resourcesfind HelpDocument5 pagesHomeconditionsquizzesnews & Expertsresearch & Resourcesfind HelpelmaNo ratings yet

- Embodiment and Schizophrenia - A Review of Implications and Applications - 2017Document9 pagesEmbodiment and Schizophrenia - A Review of Implications and Applications - 2017Pedro Gabriel LorencettiNo ratings yet

- Control The Impulse To Theow The Baby Out With The BathwaterDocument16 pagesControl The Impulse To Theow The Baby Out With The Bathwatertitan dioxideNo ratings yet

- NATUREDocument12 pagesNATUREGuadalupe BerbigierNo ratings yet

- Article Review Memory FingerprintsDocument7 pagesArticle Review Memory FingerprintsСветлана100% (1)

- Towards An Empirically Grounded Predictive Coding Account of Action UnderstandingDocument3 pagesTowards An Empirically Grounded Predictive Coding Account of Action UnderstandingAlan HartogNo ratings yet

- Sensory Information and The Development of CognitionDocument3 pagesSensory Information and The Development of CognitionInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Electrophysiological Evidence of Intuition: Part 1. The Surprising Role of The HeartDocument11 pagesElectrophysiological Evidence of Intuition: Part 1. The Surprising Role of The Heartalxzndr__No ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument50 pagesIntroductionMathumithaa karthikeyanNo ratings yet

- Ultrastructural Analysis of Neuroinflammation: Program SupportedDocument2 pagesUltrastructural Analysis of Neuroinflammation: Program SupportedAriel HananyaNo ratings yet

- Materials and MethodsDocument4 pagesMaterials and Methodsapi-253909330No ratings yet

- Neural Computations of Threat PDFDocument39 pagesNeural Computations of Threat PDFMerly Jimenez HuallancaNo ratings yet

- ConsScale A Plausible Test For Machine ConsciousnessDocument9 pagesConsScale A Plausible Test For Machine ConsciousnessFiuttenNo ratings yet

- The GCP Event Experiment: Design, Analytical Methods, ResultsDocument23 pagesThe GCP Event Experiment: Design, Analytical Methods, ResultsrdnelsongcpNo ratings yet

- Vagnoni Et Al-2015-European Journal of Neuroscience PDFDocument13 pagesVagnoni Et Al-2015-European Journal of Neuroscience PDFmysticmdNo ratings yet

- Embodied Prediction PDFDocument21 pagesEmbodied Prediction PDFmaria19854No ratings yet

- Smallwood 2009Document8 pagesSmallwood 2009NATALIA DE OLIVEIRA KUHNNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 371Document80 pages2017 Article 371AmirJabriNo ratings yet

- Aschwin de Wolf's Review of "Connectome," by Sebastian SeungDocument2 pagesAschwin de Wolf's Review of "Connectome," by Sebastian SeungadvancedatheistNo ratings yet

- Hans Op de Beeck, Chie Nakatani - Introduction To Human Neuroimaging (Cambridge Fundamentals of Neuroscience in Psychology) (2019, Cambridge University Press) - Libgen - LiDocument808 pagesHans Op de Beeck, Chie Nakatani - Introduction To Human Neuroimaging (Cambridge Fundamentals of Neuroscience in Psychology) (2019, Cambridge University Press) - Libgen - LiRAMONA PAVELNo ratings yet

- Neurosciences in CriminologyDocument7 pagesNeurosciences in Criminologycristina andreu nicuesaNo ratings yet

- Consciousness Quantum TheoryDocument12 pagesConsciousness Quantum TheoryMokhtar MohdNo ratings yet

- Kaong PS, Silang Construction Drawings 11june2021-1-11Document11 pagesKaong PS, Silang Construction Drawings 11june2021-1-11Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Biga PS Silang, Boq 11jun2021Document9 pagesBiga PS Silang, Boq 11jun2021Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Kaong PS, Silang, Boq 11jun2021Document11 pagesKaong PS, Silang, Boq 11jun2021Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- EAPP - q2 - Mod8 - Write Various Reports On SurveysDocument24 pagesEAPP - q2 - Mod8 - Write Various Reports On SurveysFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Scientists Discover A New Class of Memory Cells For Remembering FacesDocument2 pagesScientists Discover A New Class of Memory Cells For Remembering FacesFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Genetic Effects of Chernobyl Radiation: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesGenetic Effects of Chernobyl Radiation: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- What Happened To Mars's Water? It Is Still Trapped There: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesWhat Happened To Mars's Water? It Is Still Trapped There: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Why Our Brains Miss Opportunities To Improve Through SubtractionDocument2 pagesWhy Our Brains Miss Opportunities To Improve Through SubtractionFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Video Games Can Change Your BrainDocument2 pagesVideo Games Can Change Your BrainFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Open-Label Placebo Works As Well As Double-Blind Placebo in Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument2 pagesOpen-Label Placebo Works As Well As Double-Blind Placebo in Irritable Bowel SyndromeFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Among COVID-19 Survivors, An Increased Risk of Death, Serious IllnessDocument2 pagesAmong COVID-19 Survivors, An Increased Risk of Death, Serious IllnessFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Multivitamins, Omega-3, Probiotics, Vitamin D May Lessen Risk of Positive COVID-19 TestDocument2 pagesMultivitamins, Omega-3, Probiotics, Vitamin D May Lessen Risk of Positive COVID-19 TestFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Wisdom, Loneliness and Your Intestinal Multitude: Full StoryDocument2 pagesWisdom, Loneliness and Your Intestinal Multitude: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Astronomers Release New All-Sky Map of Milky Way's Outer ReachesDocument2 pagesAstronomers Release New All-Sky Map of Milky Way's Outer ReachesFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- People Affected by COVID-19 Are Being Nicer To Machines: Full StoryDocument2 pagesPeople Affected by COVID-19 Are Being Nicer To Machines: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- New Super-Earth Detected Orbiting A Red Dwarf Star: April 16, 2021Document2 pagesNew Super-Earth Detected Orbiting A Red Dwarf Star: April 16, 2021Fred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Evidence of AntarcticDocument3 pagesEvidence of AntarcticFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Automated Product Picks ExploredDocument2 pagesAutomated Product Picks ExploredFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- 50-Million-Year-Old Sea Creatures Had A Leg Up On BreathingDocument3 pages50-Million-Year-Old Sea Creatures Had A Leg Up On BreathingFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Eye Color Genetics Not So Simple, Study Finds: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesEye Color Genetics Not So Simple, Study Finds: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- How Hummingbirds Hum: Date: Source: SummaryDocument2 pagesHow Hummingbirds Hum: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Experts Recreate A Mechanical Cosmos For The World's First ComputerDocument2 pagesExperts Recreate A Mechanical Cosmos For The World's First ComputerFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Lizard Skull Fossil Is New and 'Perplexing' Extinct Species: Full StoryDocument2 pagesLizard Skull Fossil Is New and 'Perplexing' Extinct Species: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Neanderthals Had The Capacity To Perceive and Produce Human SpeechDocument2 pagesNeanderthals Had The Capacity To Perceive and Produce Human SpeechFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- How Did Dogs Get To The Americas? An Ancient Bone Fragment Holds CluesDocument2 pagesHow Did Dogs Get To The Americas? An Ancient Bone Fragment Holds CluesFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Origin of Life: The Chicken-And-Egg Problem: Date: Source: SummaryDocument3 pagesOrigin of Life: The Chicken-And-Egg Problem: Date: Source: SummaryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- 'Space Hurricane' in Earth's Upper Atmosphere Discovered: Analysis Reveals Swirling Mass of Plasma Above The North PoleDocument2 pages'Space Hurricane' in Earth's Upper Atmosphere Discovered: Analysis Reveals Swirling Mass of Plasma Above The North PoleFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Secrets of Sealed 17th Century Letters Revealed by Dental X-Ray ScannersDocument2 pagesSecrets of Sealed 17th Century Letters Revealed by Dental X-Ray ScannersFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- Extinct Monitor Lizard Had Four Eyes, Fossil Evidence Shows: Full StoryDocument2 pagesExtinct Monitor Lizard Had Four Eyes, Fossil Evidence Shows: Full StoryFred PascuaNo ratings yet

- ABA Exam Study GuideDocument12 pagesABA Exam Study GuideTaylorNo ratings yet

- Nano Satellite Separation Experiment Using A P-POD Deployment MechanismDocument37 pagesNano Satellite Separation Experiment Using A P-POD Deployment MechanismJawhni DepNo ratings yet

- Experiment: 1 OverviewDocument7 pagesExperiment: 1 OverviewKashifChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Intelligent Data Analysis For Conservation: Experiments With Rhino Horn Fingerprint IdentificationDocument8 pagesIntelligent Data Analysis For Conservation: Experiments With Rhino Horn Fingerprint IdentificationSahar HafiziNo ratings yet

- Principles of Marketing - MGT301 Power Point Slides Lecture 12Document38 pagesPrinciples of Marketing - MGT301 Power Point Slides Lecture 12Ahmed RaXaNo ratings yet

- 1 - KSU Research Methodology Overview (A Mandil, Oct 2009)Document25 pages1 - KSU Research Methodology Overview (A Mandil, Oct 2009)Fatamii IiiNo ratings yet

- Lab Report FormatDocument7 pagesLab Report FormatAmir NaqueddenNo ratings yet

- Positive Pressure Breathing During Rest and Exercise: E.A. Den Hartog, R. HeusDocument10 pagesPositive Pressure Breathing During Rest and Exercise: E.A. Den Hartog, R. HeusAlex CastilloNo ratings yet

- Ess InternalDocument5 pagesEss InternalSAHARE CANO BADWAM-AlumnoNo ratings yet

- E177 13 Standard Practice For Use of The Terms Precision and Bias in ASTM Test MethodsDocument10 pagesE177 13 Standard Practice For Use of The Terms Precision and Bias in ASTM Test MethodsRaine HopeNo ratings yet

- Eapp HandoutsDocument8 pagesEapp HandoutsJo PinedaNo ratings yet

- Uma Sekaran Solution ManualDocument31 pagesUma Sekaran Solution ManualMohamad Rizal50% (2)

- ME156P Salvado EXP 1Document10 pagesME156P Salvado EXP 1John Henry SalvadoNo ratings yet

- Year 8 Lesson Plan - The Two Main Types of EnergyDocument4 pagesYear 8 Lesson Plan - The Two Main Types of Energy4357 Cristal Argelis Liu ZhuoNo ratings yet

- JONES, David - in Conversation With Bruno Latour, Historiography of Science in ActionDocument20 pagesJONES, David - in Conversation With Bruno Latour, Historiography of Science in ActionGaby CepedaNo ratings yet

- The Nature and Extent of CrimeDocument10 pagesThe Nature and Extent of CrimeRm AnimNo ratings yet

- Scientific ResearchDocument2 pagesScientific ResearchLenz BautistaNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics in Engineering - Lecture Notes, Study Material and Important Questions, AnswersDocument4 pagesProfessional Ethics in Engineering - Lecture Notes, Study Material and Important Questions, AnswersM.V. TVNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 TestDocument4 pagesPractical Research 2 TestLen MayNo ratings yet

- LE6 FinalDocument8 pagesLE6 FinalROWELL GALABAYNo ratings yet

- Parts of The Science Investigatory ProjectDocument4 pagesParts of The Science Investigatory ProjectIresh VelanoNo ratings yet

- Applications of Response Surface Methodology in The Food Industry ProcessesDocument21 pagesApplications of Response Surface Methodology in The Food Industry ProcessesFlorentina BucurNo ratings yet

- Effect of Core Stability Training On Dynamic Strength Among College Male StudentsDocument2 pagesEffect of Core Stability Training On Dynamic Strength Among College Male StudentsAlaguraja KNo ratings yet

- RSCH-121 Weeek 1-20Document34 pagesRSCH-121 Weeek 1-20Son Gohan100% (2)

- Lesson 11 Research MethodologyDocument17 pagesLesson 11 Research MethodologyNhaaaNo ratings yet

- Time Is Money-Time Pressure, Incentives, and The Quality of Decision-MakingDocument18 pagesTime Is Money-Time Pressure, Incentives, and The Quality of Decision-Makingpaulo macedoNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology BY VENKATESHDocument128 pagesResearch Methodology BY VENKATESHAnkitaNo ratings yet

- LRP Grade6 Model2 English.Document19 pagesLRP Grade6 Model2 English.Preeta VisanthNo ratings yet