Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Edwards Photographs and The Sound of History

Edwards Photographs and The Sound of History

Uploaded by

RaduOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Edwards Photographs and The Sound of History

Edwards Photographs and The Sound of History

Uploaded by

RaduCopyright:

Available Formats

PHOTOGRAPHS AND THE

SOUND OF HISTORY

ELIZABETH EDWARDS

This article explores the nature of photographs as relational objects in the making and articulating of histories.

It argues that, in the contexts of indigenous and cross-cultural histories in Australia and elsewhere, photographs

have a relational quality, occupying the spaces between people and people and people and things. They are so-

cially salient objects and tactile, sensorially engaged objects that exist in time and space and thus in social and

cultural experience. As such, they operate not only at a visual level but become absorbed into other ways of telling

history. Photographs become not simply visual history but crucially, oral history, linked to sound, gesture and

relationships. [Key words: photography, social practices, senses, histories, indigenous Australians]

This article proposes an overview of a growing tangled with the nature of photography itself (Edwards

recognition of the importance of the material and sen- 1999, 2003; Edwards and Hart 2004; Wright 2004).

sory in the communicative power of photographs.1 My Following Miller (1998:9), I shall argue that it is only

objectives are methodological—to explore the way by engaging with the mundane and taken-for-granted

in which photographs operate as objects in the tell- that we can see what photographs actually do in social

ing of history,2 occupying the spaces between people terms. My argument also draws on Gell’s suggestion

and people, and people and things. My focus will be that “action-centered” approaches to material are more

the way in which sensory modes beyond the merely “anthropological” because they place objects in a “prac-

visual are integral to the constitution of photographic tical mediatory role...in the social process” (1998:6).

meaning and usage. In keeping with the themes of this Thus, rather than seeing photography as an abstract

special issue, I shall explore this through photographic formation or a solely instrumental practice (e.g., Tagg

meaning and usage as they pertain to Australian Ab- 1988), such a strategy places photographs as image-

original communities. At the same time, however, I objects in sets of relationships in which they are made

will be concerned with broader methodological issues meaningful through different forms of apprehension.

which, one hopes, might have wider application. I Materiality is central to this because, I shall argue, it is

shall be drawing largely, but not exclusively, on the the fusion and performative interaction of image and

recent writing on the subject in Australian contexts, materiality that gives a sensory and embodied access to

namely Roslyn Poignant’s work with Axel Poignant’s photographs. This places photographs in subjectivities

1952 photographs at Maningrida, Arnhem Land (1992, and emotional registers that cannot be reduced to the

1996), Benjamin Smith’s study of the Aboriginal com- visual apprehension of an image, and positions them

munity at Coen, Queensland (2003), and Gaynor Mac- strongly as what I shall term “relational objects.”

donald’s study of Wiradjuri/Koori use of photographs The shift toward a more evocative and experien-

(2003), as well as the works of scholars such as Michael tial anthropology, and thus the possibility of sensory

Aird (1993, 2003) and Jo-Anne Dreissens (2003). My knowledge, is a concern which has inflected visual

intention is to pull some of these ideas together and anthropology for some time. This shift acknowledges

explore them in the contexts of visual anthropology “the plurality of modes of experience and cognition

and its methodologies. by which we may both visualize theory and theorize

The central tenet of my argument is that photo- visuality” (Taylor 1994:xiii), while Taussig argues

graphs are not merely images but social objects, and the necessity of rethinking the term “vision” in rela-

that the power of those social objects is integrally en- tion to other sensory modalities (1993:26). It is pre-

Visual Anthropology Review, Volume 21, Issues 1 and 2, pages 27-46, ISSN 1053-7147, online ISSN 1548-7458. ©2006 by the

American Anthropological Association, all rights reserved. Send requests for permission to reprint to: Rights and Permissions,

University of California Press; Journals Division; 2000 Center Street, Suite 303; Berkeley, CA 94704-1223. 27

VAR_21.indd 27 2/13/06 11:28:42 AM

cisely from this concern with performative embodi- Constructing photographs as relational objects is

ment within the everyday usage of images that Pin- particularly persuasive outside the confines of Western

ney has developed the term “corpothetics” as “the photographic theory, which has dominated analysis

sensory embrace of images, the bodily engagement of photography, and more generally in anthropology.

that most people…have with artworks” (2001:158), “Dominant Western concerns of realism, subjectiv-

and Stafford has drawn attention to the way in which ity and individual and in Western modes of historical

the Saussurean “linguistic turn” of textualism, which truth, narrative and identity” (Edwards 2003:86), are

has impacted on photographic theory, has “emptied grounded in certain assumptions about the nature of

the mind of its body, obliterating the interdependence photography, often characterized in terms of death and

of physiological functions and thinking” (1997:5). In loss. Such assumptions have thus inflected the rela-

a similarly framed argument relating to embodiment tionship between photography and history. While the

of experience, Csordas has argued that the dominance recognition of the link between the photograph and

of semiotics—and hence concern with the problem of “having-been-there” (Barthes 1977:44) is probably

representation over the problem of being-in-the-world universal, how people use that link in their own con-

is evident in the relation between the parallel distinc- structions and performances of history is culturally

tion between “language” and “experience” (Csordas inscribed at a very profound level (Poignant 1996:10).

1994:11). Indeed, the relationship with disembodied Photographs are not only about loss,3 however, but,

“history” as opposed to an “experienced past,” might be about a grounded empowerment, repossession, renew-

similarly characterized. Drawing on such ideas, I shall al and contestation:

argue that in the engagement with history, photographs

are tactile, sensory things that exist in time and space, It was a beautiful day when the scales fell from

and thus in embodied cultural experience. As I have my eyes and I first encountered photographic sov-

suggested, Western notions of occularcentrism and the ereignty. A beautiful day when I decided that I

primacy of the visual in thinking about photographs would take responsibility to reinterpret images of

has elided the sensory and emotional impact of photo- Native people. [Tsinhnahjinnie 1998:42]

graphs as things that matter. I use the word “matter”

intentionally for it suggests the emotional and sensory. Betty’s [McKenzie] collection is important not

As Miller has argued “importance” and “significance” only for the photos, but also for her memories of

are distancing, analytical words, whereas “matter” “is the people in the photographs. It is the information

more likely to lead us to the concerns of those being she attaches to these photographs that make them

studied than those doing the studying” (1998:11). It an important historical record. [Aird 2003:31]

is a concern that becomes especially pertinent in an

Australian context, where family photographs and If, as visual anthropologists, we are to understand

snapshots have assumed a central role in articulating the significance of photographs in the telling of his-

suppressed, submerged, contested or fractured histo- tory, it is necessary to destabilize those dominant theo-

ries (e.g., Aird 2001). For instance, as Macdonald has ries and find other tools and methodologies that draw

argued in her study of Wiradjuri use of historical and on indigenous categories and practices of image use.

family photographs, “The fact that valued Wiradjuri Such strategies belong to the broader move away from

photos are usually simply ‘snapshots,’ of the family the grand narratives toward the localized and partic-

album type, is most probably what has contributed to ular, and from formalist models of analysis, such as

their underestimation in cultural terms” (2003:226). psychoanalysis to the study of practices on the ground

Elizabeth Edwards is Professor and Senior Research Fellow at the University of the Arts London (LCC). She

was formerly Head of Photograph Collections, Pitt Rivers Museum and Lecturer in Visual Anthropology, ISCA,

University of Oxford. She has published extensively on the relationship between photography, anthropology and

history and is currently working on materiality and the social practices of photography and on photography and

historical consciousness in Britain.

28 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 28 2/13/06 11:28:42 AM

(Finnegan 1992:50–1). In recognizing this position, Marshall 1999, Edwards and Hart 2004). In this con-

we can find ways of thinking about the specifically cul- text, photographs operate not only simply as visual his-

tural and the culturally specific nature of photographs tory but are performed, I shall argue, as a form of oral

that will open new theoretical and analytical spaces; history, linked to sound, gesture and thus to the relation-

these do not necessarily have to answer to the rational- ships in which and through which these practices are

ist, positivist or unproblematically evidential, in the embedded. In many ways, this article picks up Paul

way that photographs have been linked to historical Stoller’s challenge that we require a “sensuous schol-

documentation in the past. The material, relational and arship” that tacks between the sensual and the analyti-

sensory approach can open up the emotional and sub- cal, embodied form as well as disembodied logic and

jective. There are, of course, a number of approaches academic analysis (1997:xiv). As such, it might be said

one might take to subjectivities—for instance, the to explore photography beyond the visual: photogra-

psychoanalytical. However, my approach owes more phy whose social meanings are not necessarily dictat-

to the phenonemological with its sense of “being-in- ed exclusively by the visual but also by their percep-

the-world”, or Bourdieu’s notion of “habitus” which tion as objects through which the visual is performed

positions feeling not only in the interior subjective and understood.

space but in the space of everyday engagement with Importantly, this way of thinking about photo-

the world (Bourdieu 1977:78–87; Ingold 2000:162, graphs in relation to history strengthens their integral

169). As Jackson has argued, many of the leitmotifs position in constituting alternative histories, which

of anthropological analysis which have been used in are embodied in objects, song, movement and bodies

relation to the sociability of objects and that resonate (Stoller 1997:xvi). As Seremetakis has argued, “the

through my argument here—“practice, embodiment, interpretation of and through the senses becomes a re-

experience, agency, biography, reflexivity and narra- covery of truth as a collective, material experience”

tive”—are drawn from the phenomenological tradi- (1994:6). This resonates with what David MacDou-

tion of Husserl and Heidegger (Jackson 1996:vii). A gall has called “social aesthetics,” which reunites the

fluid sense of experience within the cultural allows an sensory, feeling and emotion with the cultural land-

experience of the past that is both constituted by and scape (1999:3–4) and where “unconscious strata of

constitutive of photographs. This is not only in terms culture are built into social routines as bodily dispo-

of discourses of representation, but, more particularly, sition” (Taussig 1993:25). Within such a framework

as a phenomenologically apprehended existence in the the understanding of the ways in which photographs

physical world that gives equal weight to all modali- are made to tell history can be extended beyond the

ties in the immediacy of human experience (Jackson visual in ways that heightens the understanding of the

1996:2). If, as Pinney has argued, the “concern for the visual itself.

political consequences of photographs has effectively

eroded any engagement with its actual practice” (Pin- ON THE SOCIALITY OF OBJECTS

ney 2003:14), then the material and sensory approach

implied within the “relational” moves us away from It is necessary first to explore the materiality of

the form of visual analysis in which photographs are images as related to the nature of photographs then to

simply the result of abstract concepts vested in power consider how this operates within sets of relationships

relations or semiotic codes. Instead, it allows us to before finally extending these ideas to look at the re-

think about the complex and shifting relationships lationship between photographs, orality and sensory

through which photographs as experienced are cre- registers of photographs beyond the visual. However

ated and endowed with meaning and purpose (Dant photographs are not merely a result of social relations

1999:124). Thus, photographs not only represent but but active within them, maintaining, reproducing and

also evoke. articulating shifting relations. This reflects the model

Images, in their many material forms, are active developed in actor network theory, in that we might

objects with the whole range of sociality with which see photographs as “intermediaries,” or as Callon

other classes of material culture are now endowed (see writes, “something passing between actors which de-

Appadurai 1986, Miller 1987 and 1998, Gosden and fines the relationship between them” (Dant 1999:124).

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 29

VAR_21.indd 29 2/13/06 11:28:42 AM

Dobres has taken this further arguing that people expe-

rience their technologies as materially grounded are-

nas in which interactions of all sorts—social and ma-

terial—occur, constituting, shaping and being shaped

simultaneously through the social and cultural. This

is not simply in terms of the physical actions of ar-

tifact production and use, but “the unfolding of sen-

suous, engaged, mediated, meaningful and materially

grounded experience that makes individuals and col-

lectives comprehend and act in the world as they do”

(Dobres 2000:5).

The recent studies of Australian Aboriginal expe-

rience to which I am referring have all stressed the

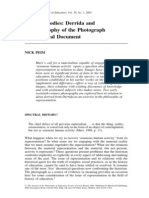

relational and material qualities of photographs: Figure 1. Lena Djabbiba (right) looking at Axel

Poignant’s photographs, with her daughter Rachel

photos are material evidence of connectedness and granddaughter Stephenie. Maningrida 1992.

Photo © Roslyn Poignant.

to what is now “past”. The more photos connect,

the more they are valued. Photos are stories about

connections through time, affirming the exis-

tence and significance of the past in the present. ing history: Gell’s position echoes Tonkin’s suggestion

[Macdonald 2003:236] that, in order to “understand how history-as-lived is

connected to history-as-recorded, we have to look at

But the relational qualities extend beyond the im- the actors concerned, who are living and developing

age itself. The promise of recent material culture stud- in times that also change”; indeed, memory might be

ies lies in the concern with the way in which “things” seen as “the site of the social practices that make us”

are actually used by people and thus how their sensory (1992:12). If photographs are central to the recupera-

apprehension impacts on, and is impacted by, objects tion of Aboriginal identities and histories (Taylor 1988;

(Myers 2001:5). Indeed, it is possible to argue that Aird 2001, 2003; Dreissens 2003; Peterson 2003; and

photographs, like other classes of material object, “are Stanton 2003 to cite a few), they become central to the

bundles of sensory properties which respond to specif- relations inherent in those social practices.

ic sets of relationships and environments” (Edwards, Photographs as objects of history emerge from

Gosden & Phillips, forthcoming). multiple sets of relationships at many levels. Photo-

While readings of photographs may, on the sur- graphs as sets of relationships are, like all relation-

face, be a forensic extrapolation of content—“This is ships, subject to negotiation, exchange, trade and mul-

my grandmother”; “This is the camp that was cleared tiple performances and meanings. Not only are they

when I was a child”—the social systems of telling objects, produced through sets of social relations that

histories into which images are absorbed are socially can be collected, exchanged through sets of relation-

grounded, embodied and expressed through subjective ships. One should add here that this applies, of course,

relations with photographs (Figure 1). Thus, we need not only to photographs active in the social relations of

to consider the network of relationships surrounding the community but also those in “the archive”; indeed,

particular photographs or groups of photographs in a number of the photographs discussed by Poignant

interactive settings (Gell 1998:8). As Latour has ar- (1996) and Stanton (2003), for instance, involved pho-

gued, it is non-humans (photographs) as well as hu- tographs that have been moved back from the archive

man actants that offer the possibility of durable social to the community.4 Whatever the course and location

cohesion (1991:103); indeed, given the indexicality of of images, the photographs’ very existence—what they

photographs, there is a sense in which the non-human/ are—is embedded in a relationship that stays with the

human divide is blurred, a point to which I shall return. photograph forever—that is, the relationship between

This impacts on the way photographs are used in tell- the subject and chemical trace of their existence that

30 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 30 2/13/06 11:28:44 AM

is the photograph itself. That relationship is projected Gosden & Phillips, forthcoming). It stresses spaces

into new spaces to perform within new relationships of relationships into which entities are placed—each

in different contexts as the image is re-engaged with domain being represented through different sets of re-

repeatedly:5 “So now I have this new relationship with lationships. What is important, for my argument here,

any photographs that I view of Nancy Chambers who I is that a relational position is intrinsically anti-essen-

can confidently say is my great-grandmother” (Dries- tialist, because those relations are made up of multiple

sens 2003:20). It is this powerful, original relationship intersections of intention, process and action. It is such

with the referent—“the trace of bodily connection” a position that allows the re-viewing and re-appropria-

(Wright 2004:76)—that inflects all other relationships tion of colonial images in Aboriginal historical frames

in which the photographs might become entangled. (Aird 2003:23–6; Smith 2003:12–17; MacDonald

Similar to Barthes’ argument on the indissoluble 2003:239) and thus moves away from dominant theo-

relation between trace and referent (1984:6), Gell ries of photography.

has argued that the indexical trace, in making a rep- The nature of photography is itself important

resentation, literally binds the index “fixed or impris- here. Photographs not only hold time and space, but

oned” to the prototype (referent). Thus, the agency of extend time and space through sets of multiple rela-

the person impressed in the representation for which tionships, their piled-up significances, an aggregate

Gell argues (1998:102) might be understood as the im- of relationships. I would argue that these sites of the

pression of social being. Even images emerging out photograph’s ambiguity lend themselves to a relational

of the profoundly asymmetrical power relations of the analysis, for the ways in which photographs exist with

colonial period might be understood in this way in that, their viewers and users are always, like relationships,

through tracing social being, such photographs carry dynamic. Indeed, following Gell (1998), one can argue

a humanizing potential that allows the possibility of that relational and performative theories of photogra-

subjective experience (Edwards 2001:19). Reading phy stress analysis of the systems of production and

images against the grain like this creates a powerful consumption, which moves photographs away from

historical presence. western categories of evaluation. This applies equally

to assumptions about the relationship between photo-

I have...often seen Aboriginal people look past graphs and history. For a material and relational ap-

the stereotypical way in which their relatives proach to images allows a performative dimension that

and ancestors have been portrayed, because they is central to the telling of histories, a point to which I

are just happy to be able to see photographs of shall return. The relational view is not simply different

people who played a part in their family history. people bringing different readings to images. Rather,

[Aird 2003:25] it is an engagement with the whole social dynamic

of photographs over space and time, in which photo-

Thus, clearly, relationships are contingent and graphs become entities acting and mediating between

mediated rather than necessarily systematic, be- peoples. The engagement with photographs as socially

cause they comprise a contradictory layering of at- salient objects both encapsulates and defines relations

titudes, sentiments and ambitions, through which between people.

photographs are both made and invested with value in As these considerations suggest, an important

the contexts of both shared and contested meanings concept in considering photographs as relational ob-

(Edwards 2004).6 As Gell has argued, objects are “a jects is as a form of extended personhood. Smith, fol-

congealed residue of performance and agency in ob- lowing Gell, has convincingly argued this position in

ject form, through which access to other persons can an Aboriginal context (Smith 2003:11). Through their

be attained and via which, their agency can be com- indexicality and reproducible form, photographs can

municated” (1998:68). be seen as “distributed objects” that initiate and act

The relational approach to photographs ac- in social relations (2003:11). Photographs are a form

cords with much current anthropological, and indeed of extended personhood in that they constitute a sum

archaeological, thinking (Gell 1998; Dant 1999; of relations over time. In this “the effect of images is

Dobres 2000; Gosden and Marshall 1999; Edwards, not simply symbolic or the result of social relations”

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 31

VAR_21.indd 31 2/13/06 11:28:44 AM

but “can themselves imitate and act in social relations” which can be attributed to a person and which, in

(2003:11). Engagements with photographs, linked to aggregate, testify to agency and patienthood dur-

the sensory—to which I shall be returning—blur the ing a biographical career which may, indeed, pro-

distinctions between internal personal and external, long itself long after biological death. [1998:222]

and relational in that “any social individual is the sum

of their relations distributed over biographical [or his- Photographs, in their social use, are created inten-

torical] time” (Gell 1998:222). Photographs distrib- tionally to project a present past into the future and

ute personhood “beyond the body-boundary” (Gell as such they become intermediaries in networks of

1998:104), the indexical trace functioning as a kind of use (Dant 1999:125). Continual re-engagement con-

detachable part or exuvia.7 firms and reaffirms “living presence,” even, as Gell

This is very important in relation to telling histo- suggests, “long after biological death.” For instance,

ries, for it is through the agency of photographs and “Cape York people speak of their old people, ‘looking

relations with photographs as objects that they are his- at us,’ from film and photographs” (Smith 2003:15),

torically enmeshed. They are, as Gell states: while Poignant quotes Gordon Machbirrbirr, Burarra

photographer at the Maningrida Bilingual Literature

not confined to particular spacio-temporal coor- Production Centre (Figure 2), as saying,

dinates, but consist of a spread of biographical

events and memories of events, and a dispersed It’s like a life coming to you. Like you have your

category of material objects. Traces and leavings, life coming back…I have never seen my ancestor,

Figure 2. Gordon Machbirrbirr with the “Die Bodies File”. Maningrida. 1992.

Photo © Roslyn Poignant.

32 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 32 2/13/06 11:28:46 AM

but I would like to see them in the photo you know tiate causal sequences and affect those persons who

and say “Ah yeah, this is my grandfather”...and come into contact with them” (Smith 2003:21)—that

when you look at the photo and say ‘Aah’ and you is, the emphasis is on the relationships that photo-

think that the spirit of that person came to life, and graphs represent through their indexical traces, rather

lived. [1992:75] than on individuals in their understandings of human

subjectivity and thus, history. Photographs are thus re-

Thus, “photos can constitute relatedness as a so- lationships made visible: “the theme which came to

cial fact. They can create a form of subjectivity, bring- dominate almost every photo-viewing session [was]

ing those distant in time and space into a present” the sense in which the photographs established con-

(MacDonald 2003:236). This process can also remove tinuities of self and families and made biographies

photographs from assumed models of periodization. and genealogies visible” (Poignant 1992:74). Indeed,

As Donna Oxenham has commented, indigenous iden- people were identified in photographs through what

tities are not necessarily locked into the periodization one might describe as a relational analysis: “identifi-

of past, present and future; rather, all three exist, like cations were made by noting the position one person

photographs, in the here and now (personal communi- occupied in relation to another—even from their back

cation, 2002). Smith, writing of the use of photographs view” (1992:74). MacDonald extends this point: “The

by the Aboriginal community at Coen, Cape York, genealogical memory is a memory of real people in

has stressed the way in which photographs fit into a real time. Photos have the capacity to extend sociali-

model by which people, things and land can all “ini- ties which, in the Koori case, are primarily based on

Figure 3. Senior men studying photographs of ceremonies. From left Bündubandu, Tommy

Wagbara and Steohen Kawürlkku. Maningrida. 1992. Photo © Roslyn Poignant.

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 33

VAR_21.indd 33 2/13/06 11:28:49 AM

face-to-face encounters”; also, “photos help to avoid have prohibitions on speaking the names of dead kin

loneliness and keep alive contacts with people through and, by extension, seeing a photograph of them (Mac-

space and time” (2003:232).8 “They [photos] allow donald 2003:236). Quoting Yasmine Mushharbash,

people to become known” (2003:235–6). In other MacDonald reports that photographs of the deceased

words, they are used to confirm and perform the pho- at Yuendumu, northern Australia, were no longer

tographs’ relationships. burned but held by people who were not close kin, for

As I have suggested, the material manifestations a later viewing at an appropriate time. Likewise, Poi-

of photographs are central to the relational, for the gnant reports that at Maringrida, photographs of the

affective tone of photographs cannot be reduced sole- recently dead were placed in “Die Bodies File,” an al-

ly to the power of the image, but the performance of bum that contains photographs from both personal and

that image as a material object. As such, photographs community occasions.10 After the period of mourning

assume a form of agency in the way they prescribe had elapsed, the bereaved could request prints so that

relations and the telling of history. The act of looking photographs could continue to function relationally in

at photographs is itself embedded in social relations the shared process of mourning (Poignant 1996:10).

(Figure 3). Not only the restrictions of looking at Moreover Poignant states,

photographs of the deceased apply in some Aborigi-

nal communities, but equally so in relations with the On one level it would seem that there is sometimes

living. Further, these processes cannot be homog- a straightforward extension of the name avoidance

enized, but constitute complex and sometimes contra- rule to include the image of a recently dead person.

dictory contexts, within communities—as narratives On another level, however, the possession of a

inflected with age, gender or lineage for instance, are photograph of a deceased relative not only serves

woven with and around photographs. to hold the image of that person in the memory

Poignant reports Jackie Nabuliya, a Maningrida but also provides a way of sharing the process of

elder, explaining some of Axel Poignant’s photographs mourning and/or recollection with others, within

in detail to his daughter. After doing so the photographs a private domain, while avoiding the same senti-

were passed back away from the women and taken to ments verbally. [1992:73]

the other side of the yard by the young men of the

family, in accordance with the community’s complex Here, we see complex relations between visual

avoidance rules. She also notes, however, that there and oral being worked out. This is so both literally, in

was sometimes the quiet illicit pleasure of scrutinizing the somatic or kinetic relations with photographs as

a photograph of one’s tabooed kin (1992:73).9 Simi- the examples suggested, and metaphorically through

larly, Bell, working in the Purari Delta region of Pap- the relations that are engendered through the spaces

ua New Guinea, describes how, at Koiriki, he handed between peoples. But, within this, we have to consider

photographs first to male elders as protocol demand- how material forms hold images in certain configu-

ed, after which they were passed down through the rations and bodily relations, giving cultural meaning

hierarchy (2003:115). However, we must distinguish and concreteness to intentions. Material forms of pho-

between formal and informal acts of looking at photo- tographs prescribe responses to them because they

graphs, and between public and private performance. demand specific bodily relations. These constitute

Each has its different verbal and embodied practices specific presences and co-presences in spaces which

and ways of scrutinizing the stories that emerge on “not only form an inescapable dimension of human

these differently understood occasions. What is impor- interactions but are also regulated by complex com-

tant here is that the experiential conditions of viewing municative conventions” concerning the way bodies

photographs are not neutral, but integral to the telling interact with one another in social space (Finnegan

of history. 2002:104).

As both Poignant and MacDonald have noted, the Loose photos induce perhaps a freer narrative,

use of photographs reflects and impacts upon changing for albums structure time and space, retemporalize

social practices concerning relationships in the treat- and guide narratives (Edwards 1999; Langford 2001).

ment of the dead. Many Australian Aboriginal societies While loose prints and albums will generate multiple

34 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 34 2/13/06 11:28:50 AM

histories, shifting on their access with each viewing,

the narrative structure of albums must be considered

as an active element in the replaying of those histories.

Albums also demand different physical and kinetic en-

gagements: they demand that the viewers gather around

one object, rather than pass single and successive ob-

jects from hand to hand, creating a differently inflected

social-spatial dynamic (Edwards and Hart 2004:11;

Bell 2003:115). Likewise, displays of photographs in

homes create landscapes of relationships and state-

ments of identity through the display and arrangement

of material objects (Wright 2004:80–1).11 As such, we

can see them “materially” located in a social world

which established their personal identity and cultural

legitimacy” which places them in a web of “meaning,

relatedness and history” (MacDonald 2003:230).

It is even more pressing to address these issues at

a time when the material and embodied experiences

of looking at images are changing radically with easy

access for many communities across the world via the

Web or CDs.12 The question remains, in time to what

extent will these technological changes impact upon

the way in which memory practices are constituted

and histories are recounted? The social act of gath-

ering around a computer screen to look at images is

Figure 4. Livingstone West with files of

markedly different from that of handling photographs,

photographs from the Berndt Museum. Kimberley,

touching them, stroking them and handing them to kin Western Australia. Photo © John Stanton

and to friends (Edwards 2003:90–1), or sitting alone courtesy of the Berndt Museum.

in quiet contemplation of an image held in the hand.

However, while digital images are often desired and

produced as material prints, one must not overlook the

fact that new ways of looking at photographs demand Indeed such a material form allowed community lead-

their own sets of embodied relations with a material ers to inspect material, assess it and control dissemina-

culture, as eyes run over the screen and fingers tap the tion as they deemed appropriate. This response cannot

keyboard, and bodies touch, clustered around the com- be reduced to a technical resistance. Surely, part of the

puter screen.13 One is making no judgment about the explanation is that the photographs as material objects

relative qualities of these very different social experi- offered a more “comfortable,” bodily engaged way of

ences, but the fact remains that they are different and telling histories with photographs. The different tech-

we must take account of them in considering the ways nologies and their material forms mediated the way in

in which photographs are understood. For instance, which the photographs, as social objects, participated

Stanton (2003:145) reports that there was resistance in social relations: they focused the act of looking, and

to the use of new technologies by older community thus telling, in certain ways.

members from Kimberley, Western Australia, in the Ownership of photographs, and access to photo-

community collaboration and visual repatriation un- graphs is an important material consideration.14 As

dertaken by the Berndt Museum as part of the Kim- MacDonald (2003:231) has demonstrated, photo-

berley Website Project. The elders were nonetheless graphs as objects of history telling move through a

keen to have albums of photographic prints (Figure 4), community as images are shown, exchanged, repro-

which could be held in the hands and perused quietly. duced and displayed. Likewise, Smith has suggested

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 35

VAR_21.indd 35 2/13/06 11:28:51 AM

the way in which the social contexts of ownership and we suffer...from forms of agency mediated via

dissemination of visual records track the complex his- images of ourselves, because as social persons,

torical relations, including blurring of the divide those we are present, not just in our singular bodies, but

between whites and Aboriginal people (2003:14). But in everything in our surroundings which bears

ownership implies the possession of a material object witness to our existence, our attributes, and our

and thus social expectations are both attached to and agency. [Gell 1998:103]

worked out through the material forms of images:

“There are many fights over photos, reflections of This position again points to the way in which

communally understood breaches of rights or eti- we have to understand images not simply in visual but

quettes, usually stemming from expectations of kin- in sensory relations in which they are enmeshed as

relatedness” (MacDonald 2003:231). Photographic social objects.

objects are entangled in a system of social rights,

obligations and values: “The value of an object is PHOTOGRAPHS, ORALITY AND

relative in terms of its potential to influence and SENSORY LANDSCAPES

determine the nature of various social outcomes”

(MacDonald 2000:96). This position would seem to Social relationships are, of course, based in com-

extend Deborah Poole’s well-known model of “visual munication, “a working through of the resources of

economy”, whereby photographs acquire meaning our bodies and our environments” (Finnegan 2002:3).

and value through the social uses of photographic In bringing material and relational thinking together

objects and commodities: “It becomes clear that the in our analysis of the way in which photographs are

value of images is not limited to the worth they accrue experienced, “the force of such photographs can be

as representations seen (or consumed) by individual linked to the effects that images are able to manifest

viewers. Instead, images also accrue value through on those who encounter them” (Smith 2003:11). We

the social processes of accumulation, possession, must now extend this and look at the nature of that

circulation or exchange” (Poole 1997:11). As Mac- effect. For photographs are the focus of intense emo-

Donald has argued in relation to Wiradjuri use of pho- tional engagement.15 As I have suggested, in premis-

tographs, this places photographs and the telling of ing of photographic effect on the visual and the foren-

history into a set of demands and expectations: “Pho- sic alone, we not only limit our understanding both of

tos are a form of capital whose value is determined the idea of images as relational objects. We also limit

within the social relations of which the photo itself is our understanding of the modes through which histo-

a part” (2003:231). ries are transmitted and maintained. For photographs,

If preciousness of photographs in most commu- as will have become clear, both focus and extend the

nities is premised on the aura of the perceived direct verbal articulation of histories. If photographs both

link with the past and the presence of the extended, extend the person and stand for relations between per-

distributed person, the force of this can be understood sons—past, present and future—the oral, tactile and

in relation to the social act of destroying photographs. haptic component of telling histories becomes crucial

Not only is there the symbolic and actual violence of here. It is to this that I now want to turn and consid-

tearing or burning the indexical trace, but, the de- er photographs as sensory objects and consider how

struction of photographs points to a breakdown or their operation within broader sensory worlds impacts

secession of social relations. Macdonald reports that upon the social relations from which histories emerge.

in the Wiradjuri community, as in many places, it I would argue that sensory engagement—handling,

was not unusual for new lovers to tear up the photo- touching, talking, and singing—is integral to the “idea

graphs of partners’ old lovers or cut them from the of personhood being spread around in time and space...

image (2003:234), yet, at the same time they rarely a component of innumerable cultural and institutional

throw the photographs away (2003:227). Converse- practices” (Gell 1998:221).

ly, photographs are often handled gently, with care A shift toward oral, tactile and embodied ways

as if a living entity. Photographs here are extensions of thinking through photographs is part of a broader

of relationships: response to concern about the way in which margin-

36 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 36 2/13/06 11:28:52 AM

alization of the senses which has resulted, objectified, which we should consider photographs not only as

and textualized analyses of the body rather than a way visual history but, as a form of oral history, and, by

of being-in-the world, saturated with intentionality, extension, the way in which the oral constitutes an

inter-subjectivity and existential immediacy (Csordas embodied vocalisation.16 The oral penetrates all levels

1994:4,10; Howes 2003:29–32). This position is par- of historical relations with photographs to the extent

alleled by recent concerns about the “decarnalization” that spoken and seen cease to be separate modalities.

of objects and, the way in which the analysis of ma- Orality is not simply the verbalising of content, a play-

terial objects is often premised solely on the visual, ing back of the forensic reading—“this is where we

and its linguistic translation. As Pinney has argued had a fishing camp”—but the processes and styles in

(2003:82), “the stress on the cultural inscription of which photographs have dynamic and shifting stories

objects and images has erased any engagement with woven around, and through, them, “imprinting them-

materiality except in linguistic terms.” As I suggested selves and being played back repeatedly through dif-

in my concern over the dominance of the semiotic, ferent tellings” (Edwards 2003:89). Photographs and

discourse around objects—and certainly images—has voice are integral to the performance of one another,

been inflected through textual metaphors of “read- connecting, extending and integrating ways of telling

ing,” of the signs and symbols to be decoded. Indeed, histories. As Poignant has reported of the response to

Stafford argues that “visual culture,” with its domi- photographs at Maringrida, not only was the commu-

nant metaphors of “reading,” merely reproduces the nity view that photographs were like bark paintings in

dominance of textualism (1997:5). This position re- that they had stories (Poignant 1992:74) but,

flects the values attached to Western understandings of

the hierarchy of the senses where seeing and hearing Sometimes, an elder’s use of the photographs to

stand for the production of rational knowledge—and transmit his reflections of a past time and a way of

touch, smell and taste for the lower, “irrational” sen- doing things to the young who had gathered around

sory (Claessen 1997:405). Significantly, in the context took on the character of storytelling, so that the in-

of Aboriginal histories considered here, Serematakis tegration of photographs seemed no more than an

has suggested the ways in which seductive imported or extension of traditional oral modes of represent-

imposed theories, such as visualism, can hide sensory ing the past. For others in the community, some

dispositions of the cultural periphery, suppressing sub- of whom were already involved in the integration

jectivities—including the sensory—which are strug- of traditional forms of visualising the past in pres-

gling within world systems of discourse and knowl- ent-day recording systems, the introduction of the

edge (1994:x). The arguments emerging from detailed photographs—an additional resource—sparked

local ethnographies and collaborations such as that of notions of history that went beyond a genealogi-

Smith and Macdonald—but more widely in the work, cal patterning of history. [1996:8]

for instance, of Brown and Peers in Canada (2005),

and Wright in Solomon Islands (2004)—is the poten- Photographs are therefore enmeshed in oral sto-

tial for reinserting the emotional, visceral and affective ries—personal, family and community histories.

into our understanding of photographs—as Pinney has They are performed through the spoken or sung hu-

argued, attending to the “praxis through which people man voice telling stories to an audience—formal or

articulate their eyes and their bodies in relation to pic- informal. Martha Langford, in her interesting analysis

tures” (2001:168). of Canadian photographic albums, has positioned se-

I am going to consider first the relationship be- ries of photographs in terms of the oral in and around

tween the visual and the oral. In the everyday use of them—the narratives they engender (2001:122–57).

photographs as conduits of historical consciousness, Her analysis draws heavily on the work of Walter Ong

photographs are spoken about and spoken to—the and, as such, she positions photographs within formal

emotional impact articulated through forms of vocal- definitions of oral literature. It thus shares the prob-

ization. Just as there has come to be a greater aware- lems of Ong’s characterization of oral culture as overly

ness of the interaction between oral and written forms ahistorical, undymanic, totalized and technically de-

of history (Finnegan 1992:50), there is a sense in termined. However, her stress on the orality of photo-

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 37

VAR_21.indd 37 2/13/06 11:28:52 AM

graphs, the specificity of oral consciousness, and the Here is a subtle intermingling of individually-

way in which “an album’s oral structure and interpre- sounded and -heard creations, of specific context,

tive performance will bring us closer to understand- and of patterns which are more or less enduring

ing the photographic work” (Langford 2001:122–3) is and agreed with others. In its own capacity to

pertinent, and instructive in the contexts we are con- draw on auditory resources in thus versatile mix

sidering here. of ways, human vocal interaction makes up a

My argument here extends Langford’s notion of remarkable, highly flexible and enormously far-

the oral dimension of the photographs by placing oral ranging human-created tool for sonic communica-

responses to them in the active sensory, experiential tion. [Finnegan 2002:80]

reiterations of history-telling and in the social embed-

dedness of photographs, rather than in formal terms. Indeed, it is, as Howes has argued a “curious fact

Contemporary Aboriginal communities should not, of that anthropologists, for all their concern with language

course, be characterized “oral societies” in the sense and “discourse” rarely pay much attention to the medi-

that anthropologists and linguistic theorists have talk- um of speech, namely sound which is taken for grant-

ed about them in the past. Rather Aboriginal societies, ed” (2003:36). For if photographs are enmeshed in the

on the whole, have a wide range of imaging and textu- oral, they are also enmeshed in sound—the sound of

alizing powers and experiences across a multiplicity of voices, spoken or sung, in rising and falling rhythms,

media, including the photographic and oral (Langton tones and volumes. Sound creates the environment for

1993:9), which makes such an analysis appropriate. viewing photographs and constitutes a social act in

What is important here is the way in which the links that it reinforces sociality of objects and the relations

between the oral and the visual can counter and mesh in which they are enmeshed and the sense of the social

with other forms in a contemporary society, shifting self (Tacchi 1998:25–7). Feld has described the flow

the balance and allowing “traditional” and multiple of sound as: “the flow of poetic song paths, [which] is

forms of history transmission to operate.17 emotionally and physically linked to the sensual flow

Yet this oral dimension is also highly regulated of the singing voice” as well as “a fusion of space and

and will inflect responses to photographs. This is time that joins lives and events as embodied memo-

because the oral expression of photographs embeds ries” (1996:91). Further, as Ingold has argued, sound

them in local structures. For instance, in traditional communicates directly and immediately through hear-

Australian contexts speaking rights are carefully con- ing. Hearing forms a porous boundary between the

trolled, knowledge itself being a form of property. external and the internal, which appeals directly to

Violating those rights of speaking is a form of theft “the ‘inwardness’ of life” (2000:245–7). But hearing

(Michaels 1991:260). There are rights to stories and also implies listening, which is an engaged intentional

histories and the control of photographs as objects is hearing (Carter 2004:44). Thus, one can argue that the

integrally related to the social patterns of the transmis- heard sound of the oral, listened to, draws the visual

sion of knowledge.18 Thus, the articulation of stories apprehension of the photograph deeper into the world

themselves, as an act of oral transmission and com- of the perceivers and their social relations, reinforcing

munication, are inflected and constrained through sets and moulding the understanding of the photograph.

of relationships. As performative objects, photographs create the

However vocalization and performance must not frame for patterns of telling, or reinforce extant ones,

be thought of simply in terms of “writable” words. If reinforcing memory not simply through the image but

the “gaze of Western thought” has ignored the mate- through the structure of repetitions—both the shape

rial, it has also ignored the dimension of sound (Stoller of telling and the contests of telling. Sound utterance,

1984:560). We need to see the oral expressions around like the photographic moment is fugitive (Langford

photographs in a more extended acoustical form, which 2001:122), but repetition, the continual re-performance

takes into account paralinguistic vocalizations such as of photographs within the oral dimension, ensures the

sobbing, laughing or the production of melody. These, longevity of both. However, silence, the absence of

Finnegan argues, create the affective tone through voice or sound, is equally significant. Forgetting and

which photographs are apprehended: loss are the silences or the non-functioning of the oral

38 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 38 2/13/06 11:28:52 AM

around photographs. The power of this suggestion is

demonstrated in the way that photographs are often

described in oral metaphors. For example, an exhibi-

tion, Lost Identities: A Journey of Rediscovery (1999),

curated by Shirley Bruised Head of the Peigan Nation,

Canada,19 proclaimed on its website that “photographs

can speak, they can whisper or shout” but they are

also described as voiceless: “many photographs...are

silent. When individuals, events or other details are not

known, photographs do not have voices.” People were

asked to “find voices and stories buried in the pictures”

(Lost Identities 1999). Oral articulation, the naming of

names, invests tellers with a dynamic power over their

own history, breaking the silence (Langton 2001:122;

Driessens 2003), articulating the interaction of photo-

graphs and people in historical relations; hence the im-

portance of photographs in telling genealogies (Mac-

donald 2003:235–6) as photographs return or reinforce

the power to speak of one’s history.20

Oral expression demands the interaction of a spe-

cific audience at a specific time—that is it is lodged in

relationships, creating the contexts for the transmission

of stories. “Understanding...photographs is a process of

reaching out for what is finally absent, rather than grasp-

Figure 5. Namaluda, Nangulumin and children in a

ing the presence of new ‘truths’” (Lippard 1992:20). group, looking at contact sheets. Maningrida. 1992.

The narrated story allows the audience to respond (Ong Photo © Roslyn Poignant.

1982:42) as stories are woven around photographs

which are held, passed from hand to hand and caressed

or even among groups clustered around the computer sorbed and refigured in the present. They can “reunite

screen. These are not single voices of linear narrative communities which are fragmented by the disparities

but polyphonic, dialogic narrations in which the nar- in generational experience and knowledge” (Peers, per-

rator shifts from point to point, adopting appropriate sonal communication, 2005). Thus, the oral entangle-

modes, effecting responses from the audience (Brown ments of photographs render them truly multi-vocal.

and Peers 2005:230–1). The rhythms shift from As this suggests, orality does not exist outside the

straight narration to song, lamentation, and laugh- broader patterns and practices of embodiment.21 As

ter—all demanding different sets of responses from discussed earlier in the contexts of materiality, photo-

listeners. Responses are not necessarily ordered, but graphs are viewed in groups—bodies touching, a prox-

multi-layered and dynamic. Perhaps the sound is of emic sense of an interpreting community. As such,

more than one language, especially in situations where proximity is not only constituted through “presences

the younger generation does not necessarily have the and co-presences” (Finnegan 2002:104) to which I

local language. have referred, but also within that space (Figure 5).

Photographs allow people to articulate histories in Proximity brings into play nonverbal channels of com-

interactive social ways that would not have emerged munication—facial expression, gesture, even smell

in those particular figuration if photographs had not (Howes 1991:171)—all of which contribute to photo-

existed. Photographs become a form of interlocutor. graphic meaning in that they create environments for

They literally unlock memories and emerge in multiple the affective experience of images.

soundscapes, allowing the sounds to be heard and thus There is a strong tactile and haptic component in

enabling knowledge to be passed down, validated, ab- oral expression of photographs as persons must be in

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 39

VAR_21.indd 39 2/13/06 11:28:54 AM

the presence of one another to communicate. Touch is,

in many ways, the most intimate of the senses, for it

registers the body to the outside world. It is arguably the

touch on the photograph that mediates the presence of

the ancestor, confirming vision, in that touch and sight

are bridged to define the real (Ong 1982:168–9) as the

finger is run over the images. It creates what Taussig,

following Benjamin, terms “optical tactility”—“the

plane where the object world and the visual copy

merge”—fulfilling the desire to get hold of something

very closely (Taussig 1993:35). Touch gives solidity

to the impressions of the other senses (Jay 1993:35),

and connects people to things. Photographs are held,

caressed, stroked, sung to. In this sense the distributed

personhood invested in the photograph is made mate-

rial, in that the photograph, through its indexical trace,

becomes an extension of the person—the ancestor per-

formed through physical engagement. As MacDonald

records of her own response to watching and hearing

people respond to photographs, “I began...to see them

as real people rather than simply images” (2003:231).

As Finnegan has argued, touch itself is not dis-

connected to the telling of history: “Human memory

is extended and embodied through our tactile as well

as our visual or auditory experience. Something of a

Figure 6. Frank Gurrmanamana singing “singray”.

commemorative function can be performed through Maningrida. 1992. Photo: © Roslyn Poignant.

the handling of familiar objects…symbolic tactile

contact between humans through external artefacts is

yet another way in which human beings extend their

experience beyond the here and now into the longer a formal sign language,22 but the “spontaneous cre-

ranges of the past” (2002:213–4). If the tactile quali- ations of individual speakers” (McNeill 1992:1).23 I

ties of photographs, with their smooth surfaces and am marking it here only as the articulation of touch

delicate paper bases, are secondary to visual, they are and embodied responses to photographs. However, it

none the less highly significant in the transmission of is worth noting in our relational concerns here that, in

shared values and memories. As a number of commen- Aboriginal sign-language, kin and social interaction

tators have suggested, history and memory are em- is mediated through the body (Kendon 1988:330–68).

bodied and materialized (Fentriss and Wickham 1992; Gesture coexists with speech, in that we should “re-

Connerton 1989; Forty and Kuechler 1999). “Human gard the gesture and the spoken utterance as different

memory [and thus history] is extended and embodied sides of a single underlying mental process” (McNeill

through tactile as well as visual and auditory experi- 1992:1), closely intertwined with the oral in time,

ence” (Finnegan 2002:213). Not only are photographs meaning and function, and thus, the telling of histo-

touched, but they are enmeshed in a fluid continuum ry. Even small movements reinforce both voice and

of touch and gesture cohering groups of interlocu- image and thus narration, making it more vivid and

tors. Touching is one of the most expressive gestures revealing the speaker’s conception of the discourse

that both links the personal, idiosyncratic and con- (Finnegan 2002:111; McNeill 1992:217). While a

text specific to socially regulated aspects, and frames detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this paper,

the pragmatic content of the oral image, marking the and in any case requires specific ethnographic

story (McNeill 1992:2, 183). By gesture, I mean not grounding, it is essential that we see photographs as

40 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 40 2/13/06 11:28:56 AM

embedded in gesture just as they are in oral expres- a recovery of truth as a collective, material experi-

sion. This link between body, gesture and historical ence,” revealed through gesture, experience and per-

narration has, of course been widely recognized by formance (1994:6). If touch is a defining characteristic

oral historians (for example Finnegan 1992:106–7; of vision in relation to the social use of photographs,

Tonkin 1992:51–2), however, it is equally important then, methodologically, there is no way in which we

to recognize that the presence of the photograph will can elide the material, and the sensory, in thinking

elicit specific gestural and haptic forms which shape about photographs.

the communication of history. Bell records how, in

Purari, photographs inspired women to demonstrate CONCLUSION

dances, and men to pound the floor in the rhythm of

hand drums (2003:116). If “photography produces a set of objects, mean-

The fact that touch and gesture become so impor- ings, and social relationships” (Smith 2003:22)

tant in the unspoken relations with photographs can through which histories are articulated, we need to

be linked back to the nature of the photograph look for fuller ways to understand their apprehension.

and its indexical quality. It would seem to enhance What I have argued for here is for a more sensory way

our argument for photographs as “distributed persons”, of thinking about photographs if we are to understand

and the way in which the communication with the their true impact in the making of histories. Stoller has

photograph/person at a subjective level cannot be eas- argued that “fully sensuous scholarship encompasses

ily disentangled. reality, imagination and reason, difference and com-

Touch and gesture bring us back to relationships, monality fused and celebrated in both rigorous and

because they operate in the “immediate bodily pres- imaginative practices as well as in expository and

ence of interacting participants” (Finnegan 2002:212). evocative expression” (1997:89). It is for this reason

This important point is demonstrated by Poignant’s that I have chosen to position photographs and histo-

description of Frank Gurrmanamana, the principle ries in Stoller’s model of sensory scholarship rather

Anbarra owner of the Jambich Rom ceremony, sing- than more formalist models of for instance psycho-

ing a series of Jambich manikay songs (Figure 6).24 logical and cognitive anthropology, psychoanalysis,

This he does in response to a series to Axel Poignant’s or psycho-dynamics. Such approaches require specific

photographs of the rom ceremony, and he does so by ethnographies to be meaningful, rather than the broad

matching the appropriate verse in the series of the im- methodological sweep that has been my concern here.

age. The verbal imagery of the songs mirrors the visual My aim has been rather to consider, with an increas-

imagery of the indexical trace of the rom pole motifs ing emphasis in visual anthropological research of the

(Poignant 1996:23). But the embodied interaction is practices and processes of visuality and photography

extended beyond the visual as Frank Gurrmanamana in many cultures, that maybe it is time to extend vi-

uses the photographs themselves as clapping sticks to sual anthropology beyond the visual, and to explore

accompany his singing (Poignant, personal communi- the ways in which visual practices, such as the use

cation, 2003), holding them in his hands, beating them of photographs, are integrally related to other sensory

rhythmically with his fingers, recalling the sound of forms through which the past is articulated.

the clapping stick and its significances. The experience Macdonald has argued that as photographs become

of the photographs, their meaning and impact cannot reproduced and performed in different contexts, the

be reduced merely to a visual response but, as I have value attributed to personal collections of photographs

argued throughout this paper, must be understood as a diminishes and the power of keepers of memory shifts

corpothetic engagement with photographs as bearers (2003:241). This may be so, but, I would argue, only

of stories in which visual, sound, and touch merge. up to a point. New forms, such as published books

As Seremetakis has argued, the sensory is not only and websites might constitute different performances

in the body but is external to it, and disperses into the of those images and prescribe different embodied and

surfaces of things which themselves impact percep- relational dynamics through their material perfor-

tual experience in a mutually sustaining relationship: mances. However, there remains, even in the digital

“the interpretation of and through the senses becomes age, an emotional desire to own photographs as mate-

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 41

VAR_21.indd 41 2/13/06 11:28:56 AM

rial objects. To hold them, display them, stroke them, 5 Significantly, in all the case studies from which I am

pass them around and tell stories whether those pho- drawing, portraits, formal and informal, constitute

tographs are produced as analogue, printed in a book, the main focus of attention.

recorded as digital pseudo-photography, or pulled off 6 Poignant has demonstrated the way in which a

a website. We must see them as part of ongoing social commercially produced photograph of a group of

biographies of images that remain entangled with dy- Aboriginal people taken in London inscribes Ab-

namic sets of sensory and social relations beyond and original relationships, as they stand according to

in excess of the image itself. their kin groups and people, rather than—despite

appearances—a grouping arranged by the photog-

NOTES rapher (2003:58).

7 Batchen (2004:40) has made this point in the discus-

1 I am most grateful to my colleagues Chris Gos- sion of Western practices and the 19th century pre-

den, Laura Peers and Roslyn Poignant for discuss- dilection of placing photographs in conjunction with

ing many aspects of this paper with me and for other detachable parts of the body, especially hair.

their invaluable comments. I should also like to 8 Indeed, expressions of political empowerment have

thank colleagues from across the world who took been expressed through the photographic metaphor

part in the Wenner-Gren Research Symposium on of “reclaiming the shadows“ (Edwards 2003:84).

material culture and the senses in Sintra, Portugal, 9 For instance, the avoidance by a young man of his

2003. Our stimulating discussions on that occa- sister or a married man of his mother-in-law.

sion started me thinking in this direction. I should 10 The album was kept at the Maningrida Bilingual Lit-

also like to thank Roslyn Poignant and John Stanton erature Production Centre by Gordon Machbirrbirr.

for kindly giving me permission to use their 11 Bell records how in private viewings in the Pu-

photographs. rari region heirlooms were brought out and shown

2 Throughout I am using “history” in the broadest alongside photographs, both merging into personal

sense of engaging with and narrating pasts. histories (2003:115).

3 The role of photographs in addressing the sense 12 For the implications of this technological shift and

of trauma and loss of identity and histories of the the values clustered around the scanned photograph

“Stolen Generation” in Australia has been of ma- see Sassoon (2004).

jor importance, especially in the wake of the 1997 13 I am grateful to Toby Wilkinson, with his deep un-

report Bringing Them, Home. There have been a derstanding of digital technologies, for discussing

number of important archival projects, for example, some of these ideas with me.

that with the Kimberley community, Western Aus- 14 This again has impacted on archival practices, with

tralia (Stanton 2003) or those around the historical increasing demands for access and sometimes con-

collections of the Queensland Museum (Aird 1993). trol over images in institutional environments (e.g.,

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Tor- Powers 1996; Fourmile 1990; Edwards 2003; Brown

res Strait Islander Studies in Canberra runs a fam- and Peers 2005).

ily history advice service for Aboriginal people 15 The anthropology of the emotions is beyond the

(see, http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/lbry/fmly-history/, scope of this paper although emotions are closely

accessed October 26, 2004). related to the senses and their differentiation is cul-

4 The material and sensory qualities of “the archive” turally and historically determined (see Howes 1991;

and its disruption of those qualities of photographs Claessen 1993, 1997). There is an extensive litera-

as “ a massive exercise in dehistoricisation and ture on emotion, (e.g., Lutz and White 1986; Lutz

decontextualisation” (Hayes et al. 1988:6) is beyond and Abu-Lughod 1990; Leavitt 1996). Harkin (2003)

the scope of this paper. However, the practices of has recently argued the importance of recognizing

archival arrangement and dissemination impact emotion as a modality in historical narrative. Given

upon community uses. (See Fourmile 1990; Edwards the traumatic histories to which photographs allude

2003; Sassoon 2004; and Brown and Peers 2005 in an Aboriginal context, Harkin’s argument would

for examples) make a useful extension of the one presented here.

42 Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 Vi s u a l A n t h ro p o l o g y R e v i e w

VAR_21.indd 42 2/13/06 11:28:56 AM

16 My concern here is with the condition and process Appadurai, Arjun

of the oral—orality—rather than the specifics of lan- 1986 The Social Life of Things. Cambridge: Cam-

guage itself. bridge University Press.

17 The precise dynamics of this will, of course, vary

Barthes, Roland

across different kinds of communities, whether “re- 1977 The Rhetoric of the Image. In Image Music Text.

mote” or “settled” (Langton 1993:11–13). S. Heath, trans. Pp. 32–51. London: Fontana.

18 Isaac has explored ways in which access to photo-

1984 Camera Lucida. R. Howard, trans. London:

graphs was controlled through the structures of tra- Fontana.

ditional knowledge at Zuni, New Mexico (2002).

19 In collaboration with the Alberta Community Devel- Batchen, Geoffrey

opment project. 2004 Ere the Substance Fade. In Photographs Objects

20 “Giving voice” has also, of course, had a literal and Histories: On the Materiality of Images. Elizabeth

metaphorical meaning in reflexive anthropological Edwards and Janice Hart, eds. Pp. 32–46. London:

practices in recent years, including in visual anthro- Routledge.

pology. (e.g., MacDougall 1998:93–122). Bell, Joshua

21 As Merleau-Ponty argued, “Embodiment is the ex- 2003 Looking to See: Reflections on Visual Repatria-

istential condition of possibility for culture and self” tion in the Purari Delta, Papua New Guinea. In

(Csordas 1994:12). Museums and Sources Communities. L. Peers and

22 Kendon’s argument is that in formal Aboriginal sign A. Brown, eds. Pp. 111–122. London: Routledge.

language not only is kin articulated in gesture and Bourdieu, Pierre

sign by pointing to a part of the body, but that “The 1977 Outline of a Theory of Practice. R. Nice, trans.

body-articulated character of kin-signs appears to be Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

a reflection of how social interaction, within a given

relationship, is mediated by way of the body.” This, Brown, Alison K., and Laura Peers with members of

in its turn, is reflected in language (1988:330–1). the Kainai Nation

23 There is an extensive literature on gesture (e.g., Mc- 2005 Pictures Bring Us Messages / Sinaakssiiksi

Neill 1992; Kendon 1997). There are also formalised aohtsimaahpihkookiyaawa: Photographs and His-

sign languages; see for example, Kendon (1988). A tories from the Kainai Nation. Toronto: University

special issue of Visual Anthropology Review, “The of Toronto Press.

Third Eye: Deaf Visual Traditions” (1999–2000, Carter, Paul

15:2) marks the established interests of visual an- 2004 Ambiguous Traces. Mishearing and Auditory

thropologists in gesture and sign. Space. In Hearing Cultures: Essays on Sound

24 Significantly, in the context of my argument here,

Listening and Modernity. Veit Erlmann, ed.

the Rom is a ceremony about making and consolidat- Pp. 43–63. Oxford: Berg.

ing friendly relationships and the sharing of special

Claessen, Constance

knowledge (Poignant 1996:21).

1993 Worlds of Sense: Exploring the Senses in History

and across Cultures. London: Routledge.

REFERENCES 1997 Foundations for an Anthropology of the

Senses. International Social Science Journal

Aird, Michael 153:401–12.

1993 Portraits of our Elders. Brisbane: Queensland

Museum. Connerton, Paul

2001 Brisbane Blacks. Southport, Queensland: Kee- 1989 How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cam-

aira Press. bridge University Press.

2003 Growing up with Aborigines. In Photography’s Csordas, Thomas J., ed.

Other Histories. Christopher Pinney and Nicolas 1994 The Embodiment of Experience: The Existen-

Peterson, eds. Pp. 23–39. Durham, NC: Duke Uni- tial ground of Culture and Self. Cambridge: Cam-

versity Press. bridge University Press.

Visual Anthropology Review Vo l u m e 2 1 Number 1 and 2 Spring/Fall 2005 43

VAR_21.indd 43 2/13/06 11:28:57 AM

Dant, Tim Forty, Adrian, and Susanne Kuechler, eds.

1999 Material Culture in the Social World: Values, Ac- 1999 The Art of Forgetting. Oxford: Berg.

tivities, Lifestyles. Buckingham: Open University Fourmile, Henrietta

Press. 1990 Possession is Nine-Tenths of the Law—and Don’t

Dobres, Marcia-Anne Aboriginal People Know It. COMA 23:57–67.

2000 Technology and Social Agency: Outlining a

Gell, Alfred

Practice Framework for Archaeology. Oxford:

1998 Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory.

Blackwell.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dreissens, Jo-Anne

Gosden, Chris, and Yvonne Marshall

2003 Relating to Photographs. In Photography’s Other

1999 The Cultural Biography of Objects. World Ar-

Histories. Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peter-

chaeology 31(2):169–178.

son, eds. Pp. 17–22. Durham, NC: Duke Univer-

sity Press. Harkin, Michael E.

2003 Feeling and Thinking. In Memory and Forget-

Edwards, Elizabeth

ting: Towards an Ethnohistory of the Emotions.

1999 Photographs of Objects of Memory. In Material

Ethnohistory 50(2):261–284.

Memories: Design and Evocation, M. Kwint, J.

Aynesley and C. Breward, eds. Pp. 221–236. Ox- Hayes, Patricia, W. Jeremy Silvester and Wolfram

ford: Berg. Hartmann

2001 Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and 1998 Photography, History and Memory. In The Co-

Museums. Oxford: Berg. lonialising Camera: Photographs in the Making

2003 Talking Visual Histories: Introduction. In Mu- of Namibian History. W. Hartman, W. J. Silvester

seums and Sources Communities. L. Peers and and P. Hayes, eds. Pp. 2–9. Cape Town: University

A. Brown, eds. Pp. 83–99. London: Routledge. of Cape Town Press.

2004 Thinking Materially/Thinking Relationally. In Howes, David

Getting Pictures Right: Context and Interpretation. 1991 Sensorial Anthropology. In The Varieties of Sen-

M. Albrecht, V. Arlt, B. Müller and J. Schneider, sory Experience. David Howes, ed. Pp. 167–191.

eds. Pp. 11–23. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Edwards, Elizabeth, Chris Gosden and Ruth Phillips, 2003 Sensual Relations, Ann Arbor: University of

eds. Michigan Press.

Forthcoming Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Muse- Ingold, Tim

ums and Material Culture. Oxford: Berg. 2000 Perception of the Environment. London: Rout-

Edwards, Elizabeth, and Janice Hart, eds. ledge.

2004 Photographs Objects Histories: On the Material- Isaac, Gwyneira

ity of Images. London: Routledge. 2002 Museums as Mediators. D. Phil. Dissertation,

Feld, Steven University of Oxford.

1996 Waterfalls of Song. In Senses of Place. Steven Jackson, Michael, ed.

Feld and Keith Basso, eds. Pp. 91–135. Santa Fe: 1996 Things as They Are: New Directions in Phenom-

School of American Research Press. enological Anthropology. Bloomington: Indiana

Fentriss, James, and Chris Wickham University Press.

1992 Social Memory. Oxford: Blackwell. Jay, Martin