Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In The "Image" and "Likeness" of God, J. Maxwell Miller - Article

In The "Image" and "Likeness" of God, J. Maxwell Miller - Article

Uploaded by

Pishoi ArmaniosOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

In The "Image" and "Likeness" of God, J. Maxwell Miller - Article

In The "Image" and "Likeness" of God, J. Maxwell Miller - Article

Uploaded by

Pishoi ArmaniosCopyright:

Available Formats

In the “Image” and “Likeness” of God

Author(s): J. Maxwell Miller

Source: Journal of Biblical Literature , Sep., 1972, Vol. 91, No. 3 (Sep., 1972), pp. 289-304

Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3263163

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3263163?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Journal of Biblical Literature

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IN THE "IMAGE" AND "LIKENESS" OF GOD

J. MAXWELL MILLER

EMORY UNIVERSIIY, ATLANTA, GA. 30322

tHE three passages in which the priestly writer introduces the concept that

1 man was created in the "image" (seZem) and "likeness" (demg6t) of God

have already been explored so thoroughly by biblical scholars that one may ques-

tion whether any further significant observations can possibly be made.l Most

of the previous studies have concentrated on the first of these three passages,

however, Gen 1:26-27, with less attention given to the other two, Gen 5:1-3

and 9:6. The first part of this paper is devoted to a brief review of the major

exegetical issues involved and the various lines of interpretation which have been

most popular among critical scholars during recent years. The second part con-

centrates on the old saying which the priestly writer quotes in 9:6. A form-criti-

cal analysis of this old saying will provide, I believe, an important clue to the

nature of the "image of God" concept during its pre-priestly stage of transmis-

sion.

A few preliminary comments are necessary concerning the priestly stratum

of the Pentateuch as a whole. This stratum reflects a complex literary history

and cannot be attributed, without extensive qualification, to a single writer or

even to a single period of Israel's history. It incorporates many old traditions,

some of which have undergone significant changes during the process of trans-

mission.2 The references throughout this paper to "the priestly writer" are not

1 For bibliographical information, see esp. J. J. Stamm, "Die Imago-Lehre von Karl

Barth und die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft," Antwort: KoFrl BoFrth zm4m siebzigsten Ge-

bartstoFg (Zurich: Evangelischer Verlag, 1956) 84-98. W. H. Schmidt, Die Schopfm4ngs-

geschichte der PriesterschoFft (BWANT 17; Neukirchen: Neukirchener Verlag, 1964)

127-49; and C. Westermann, Genesis (BKAT 1/3; Neukirchen: Neukirchener Verlag,

1966) 203-14.

2The extent to which the priestly writer based his account of creation and the be-

ginnings of human history upon earlier literary formulations remains uncertain. I my-

self tend to be cautious in this regard. The tension between God's creation by divine com-

mand and his creation by divine activity has, for example, probably been overempha-

sized. The sequence of divine command followed by divine creative acts is clearly paral-

lelled in both the Atrabasss Epic and the Ergmv Elish. The essential difference and

this is what gives rise to the supposed tension is that both the divine command and the

divine activity are attributed to the same God in the priestly account. Cp. esp. Gen 1:26-

(Q) 1972, by the Society of BibZicvZ Literatre

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITEVTUE

290

entirely unjustified, on the other hand, since the stratum also reflects a coher

literary structure and a continuity of style and thought. This is especially true

of the priestly materials in Genesis 1-11.3 The weight of evidence also suggests

that the priestly stratum reached essentially its present form during or soon after

the Babylonian exile. This means that we must take very seriously the possibility

of direct Mesopotamian influence. The Exile was, of course, not the first occa-

sion for cultural contact between the people of Israel and Mesopotamia. Yet the

exiles were surely under more direct and intensive Mesopotamian illfluence tha

any of their predecessors had been. They must have been impressed by the splen-

dor of Babylon and the military might of her kings. They no doubt learned very

quickly the language of the land, which was a Semitic language similar to their

own. And they could hardly have escaped the influence of Mesopotamian re-

27 with the creation of man in the Atratvsss Fpic (W. G. Lambert and A. R. Millard,

eds., Atro^-doFsis: The Babylonias Story of tbe F]ood [London: Oxford University, 1969]

57-61 ) . As for the supposed incongruency in Genesis 1 between the eight acts of creation

and the seven day schedule, I suspect that this has been more of a problem for modern

commentators than it was for the priestly writer himself. His account is carefully organized,

not according to the number of individual creative acts, but according to the major phases

of creation. The schedule is as follows:

(l) The establishment of day and night. This involved the creation of light, the

separation of this light from darkness, and the naming of day and night.

(2) The division of the waters above from those below. This involved the creation

and naming

those below. of the firmament (heaven) which holds the waters above from

(3) The establishment of order beneath the heavens. This involved the draining of

the waters which remained below into seas so that dry land (earth) could ap-

pear and the initiation of vegetation on the earth.

(4) The creation of the heavenly bodies (especially the sun and moon) to rule over

and maintain the order which had been established thus far.

(5) The creation of animal life in the seas and skies.

(6) The

overcreation

the otherofcreatures.

animal life on dry land, including man who is given dominion

(7) The sanctification of the Sabbath.

It is significant to note that the priestly writer recognizes two realms of authority deriving

from creation, each of which is under a divinely appointed category of sovereigns. The

first of these is the inanimate universe, including the earth with its vegetation. This

realm is ruled (masa]) by the luminaries, particularly the sun which rules by day and the

moon which rules by night. The other realm is that of the living creatures who dwell in

the seas, in the skies, and on the earth. It is over these that man has dominion (radoFh).

It is altogether reasonable that the ancient writer would have associated the earth's vegeta-

tion with the realm dominated by the luminaries rather than that dominated by man. The

ancients were well aware that the growing season corresponds in some way to the position

andrefers

14b movements

specifically toof

thethe luminaries.

seasons. This is not to assume, however that mo'adsm in vs.

3See, e.g., O. Eissfeldt, The Old TestoFmeRnt: ARn Introdm4ctioRn (New York: Harpet

and Row, 1965) 207-8; A. Weiser, The Old TestoFment: Its FormoFtioRn oFnd De2velopment

(NewYork:

(New York: Association,

Abingdon, 1961 ) 139; G. Fohrer, lRntroduction to the Old TestoFment

1968) 185-86.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MILLLR: IN THE IMAGL D LIKLNLSS OF GOD 291

ligious concepts, especially when these concepts were reflected in the colorful

Mesopotamian mythology and Babylon's impressive religious festivals. We may

assume, therefore, that the priestly writer was familiar with the Mesopotamian

traditions concerning the origins of man, and that these traditions were having

some influence upon the community for which he produced his work. This as-

sumption is confirmed, of course, by the numerous similarities between the

priestly materials in Genesis 1-11 and such Mesopotamian documents as the

Atrahas«s Epic, the Sgmerian King List, the Ergma Elish, and the Gi1Kgameth

Epic.4

(a) The telmage of God" in Reference to Man's Corporea1 Appevrance: It

is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the "image of God" passages are at least

reminiscent of the widespread view among the peoples of the ancient Near

East that man is similar to the gods with regard to his corporeal appearance. This

is suggested in the first place by the priestly writer's choice of terminology.

Selem is a rather concrete term which is normally used in the OT to refer to a

model or idol of something and always has to do with a similarity in physical ap-

pearance.5 Demg6t is a more abstract term with a broader range of usage, but it too

is normally used in connection with visual similarities. Ezekiel's use of demg6t

in the description of his vision of God is especially instructive. Although Ezekiel

is extremely cautious and leaves us with the overall impression that the appear-

ance of God's glory defies adequate description, he uses demgt very effectively

4This is not to ignore the equally striking dissimilarities, of course, nor the very

likely possibility (see below) that the Mesopotamian influence upon the priestly account

. . .

was as muc :1 negatlve as posltlve.

6 One must not be led astray by the fact that the psalmist parallels selem with balo

in 73 :20. It is obvious that the comparison which he wishes to draw between the evil men

who prosper and the visions of a dream has to do with the ephemeral existence of both

rather than with any non-physical quality. Just as the things which one sees in a dream

are only copies or "images' of real things and suddenly disappear when the dreamer

awakes, so are evil men set in slippery places and destroyed in a moment.

Truly you set them in slippery places;

you make them fall in ruin.

How they are destroyed in a moment,

swept away utterly by terrors!

They are like a dream when one awakes,

on awakening you despise your phantoms (salmam).

The intended implication of sflem is essentially the same in Ps 39:7, the only difference

being that here the focus is upon the ephemeral character of mankind in general. It is

significant to note, moreover, that selfm is paralleled in this psalm with nissab (vs. 6).

The translation of vss. 6-7 is problematic in any case, but nsb is the normal designation in

several of the Northwest Semitic dialects for a stela or a statue. Cf., e.g., the opening lines

of the steles of Zakir (a 1) and Ben-Hadad (1), and the comments by M. Dahood in

his Psaltns 1: 1-50 (AB 16; Garden City: Doubleday, 1966) 241.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE

to suggest that this appearance was in a form more like that of a man than of any

other creature.

And above the firmament over the heads there was a likeness (demgt) of a

throne, in appearance like sapphire; and seated above the likeness of a throne was

the likeness as it were ot a hllman form (demgt kemar'eh 'adam). And upward

from what had the appearance of his loins l saw as it were a gleaming bronze, like

the appearance of fire enclosed round about; and downward from what had the ap-

pearance ot his loins I saw as it were the appearance of fire....

Such was the appearance of the likeness (demgt) of the glory of the Lord

(Ezek 1 ;26-28 ) .

The view that man is similar to the gods with regard to his corporeal ap-

pearance is reflected in the Mesopotamian myths which assume that the primary

purpose of man's creation was to provide substitute workers for the gods.6 The

view is expressed more explicitly in the Gilgamesh Ep«c in connection with the

creation of Enkidu.

When Aruru heard this,

a double of Anu she conceived within her

Aruru washed her hands,

pinched off clay and cast it on the steppe.

(On the steppe) she created valiant Enkidu, . . .7

The anthropomorphic language which extends throughout the OT should also

be mentioned in this connection, but the theophanic tradition is perhaps the

clearest evidence that this view existed among the people of Israel. The biblical

writers were extremely cautious, of course, when describing God's theophanies,

usually giving more attention to the surroundings of his appearance than to God

himself. It is altogether clear from their descriptions, however, that God's bodily

form was understood to be essentially like that of a man.8 Ezekiel's description

of his vision of God stands as evidence, moreover, that the theophanic tradition

was still very much alive during the priestly writer's day. It also raises the possi-

bility that the term demgt had a special connection with this tradition.9

Noldeke10 argued as early as 1897 that the "image of God" concept had

6 See esp. the Atrabasss Ep«c, where the lesser gods go on strike because of the diffi-

culty of their assigned tasks which seems to have consisted primarily of digging the

rivers and canals and man is created to take over their jobs (Lambert and Millard, Atra-

Elasis, 57-61). This epic also calls attention to the distinction which was made between

male and female at the time of creation (ibid., 8, 43-63).

7Tr., E. A. Speiser (ANET [2d ed., 1955] 74).

8See J. Barr, "Theophany and Anthropomorphism in the Old Testament," VTSgp

7 ( 1959) 31-38.

u See J. Barr, "The Image of God in the Book of Genesis-A Study in Terminology,"

BJRL 51 (1968) 11-26, esp. p. 24.

10nle52 and :5s, ZAW 17 (1897) 183-87. Noldeke also argued that the meaning

and usage of sZem in Psalms 73 and 39 are not essentially different from its meaning

and usage elsewhere in the OT (p. 186).

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MILLER: IN THE "IMAGE" AND "LIKENESS" OF GOD 293

basicalty to do with man's physical appearance, and Gunkel1l took this position

in his commentary on Genesis in 1901. It was not until the publication of Paul

Humbert'slS careful word studies of selem and demgt in 1940, however, that

this view came to be widely accepted by critical scholars. The discussion since

1940 has? as J. J. Stamm13 recently observed, centered less arollnd the question

of whether the "image of God" concept has to do with man's physical appearance,

and more around the question of whether the priestly writer wished also to imply

some broader or deeper meaning.

(b) The Interchangecghle Vse of selem and demgt: The parallel and inter-

changeable use of selem and demSt in the three "image of God" passages is sus-

picious on at least three grounds- ( 1 ) The redundant sentence structure of Gen

1:26 and 5:3 suggests that one of the terms has been introduced secondarily. (2)

The combination of these two terms is unique to the "image of God" passages.

Nowhere else in the OT do they appear in parallelism or even in connection with

each other. ( 3 ) The two terms are not entirely paralTel and certainly not synony-

mous in their meaning and normal usage. The essential difference, as noted

above, is that demgt is a more abstract term and can be lased in reference to simi-

larities other than visual ones. In Isa 13:4a, for example it has to do with a simi-

larity in sound:

Hark, a tumult on the mountains as of (defnat) a great multitude!

Hark, an uproar of kingdoms, of nations gathering together!

Humbert argued that the priestly writer introduced the less specific and

more abstract demgt alongside selem in order to avoid the obvious implication

of the latter that man's body is a rather precise copy of God's.

En emplovant dans Gen. 1, 26; 5, 1.3 le terme demovt, le Code Sacerdotal use donc

de Ia meme precaution deja frequente chez tzechieI; iI precise que l'objet (sSe)

dont il est question et qui represente l'aspect physique de Dieu n'est pas substantielle-

ment identique a ce dernier, mais lui "ressemble" seulement.l

Scholars who have dealt with this problem since Humbert have followed the

same general approach more often than not. They have assumedS in other words,

that seZem was the key term in the priestly writer's thinking and supposed that

he introduced d°mgt alongside seZem in order to limit, clarify, or modify the lat-

ff Genesis (HKAT; 6th ed.; Gottingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1964) 112.

Cf. also G. von Rad, "Die Gottesebenbildlichkeit im AT," TWNT 2 (1935) 387-90, esp.

p. 389; or TDNT 2 (1964) 381-83, esp. p. 382.

l2"1Etudes sur le recit du paradis et de la chute dans la Genese," Memoires de 1's4ni-

?versite de Nes4chdtel 14. Although Humbert's monograph has to do primarily with the

Yahwistic account of creation, he devotes a concluding chapter (ch. 5, pp. 153-75) to

the "image of God" concept. Cf. also L. Kohler's expansion of Humbert's word studies

("Die Grundstelle der Imago-Dei-Lehre, Genesis 1,26," TZ 4 [1948] 16-22).

13p. 90.

lp. 165.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATUR8

ter's implications in some way.15 But there are at least two problems with this

approach. In the first place, when two terms are used together as selem and

d°mgt are in these passages, it is not the term with the broader and less specific

meaning which affects the implications of the more specific one, btlt the other

way around. If anything, selem seems to clarify the rather vague implications of

d°mgt in these passages by specifying that the similarity between God and man

to which it refers has to do with their corporeal appearance. Irl the second place,

it is difficult to understand why the priestly writer would have used selem at

a11, if he considered it problematic. Why did he not favor demgt and use it alone

if it was a more appropriate term for his ptlrpose? Eichrodt argtles in response

to this question that the choice of seZem was determined by earlier tradition.

That this idea was, in fact, an innovation on the part of the priestly writer himself

is as improbable as anything could well be; rather, like so much else in his account,

it will have come down to him by way of an older tradition, the existence of which

is indicated also by the Babylonian texts.... It is consonant with this that he does

not adopt the crucial word (sflesn) as an adequate description of the picture of man

which he has in mind, but takes care to define it more closely; b°salmen?w is both

limited and weakened by the addition of kidm¢ten.16

The weakness of Eichrodt's argument, of course, is that this supposed older tra-

dition concerning the creation of man in wAnich reZem fvar t/se crgsial term has

yet to be verified. There is no evidence of the use of .relem (or a cognate) in

connection with man's creation or his association with the ,ods? either elsewhere

in the OT or in the texts of Israel's neighbors.17

(c) The Kingship IdeoZogy: It may be argued on at least three grounds

that the priestly account of the creation of man was influenced by the kingship

ideology of the ancient Near East: ( 1 ) The kings of the ancient Near East were

occasionally referred to as "images" of their gods, and three Akkadian texts from

15See, e.g., L. Kohler, "Die Grundstelle," 21; W. Eichrodt, Theology of the Old

Testament (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1967) 2, 122-23; F. Horst, "Face to Face: The

Biblical Doctrine of the Image of God," Int 4 (1950) 259-70, esp. p. 261; and J. Barr,

24.

16p. 122-23. Cf. Kohler, "Die Grundstelle," 21.

l7Man's similarity to the gods was generally assumed, as we have seen, and king,s

were occasionally referred to as "images" of their gods (see below). But never is man-

kind in general said to have been created in the "image" (sflem or a cognate) of the gods.

Gen 1:26-30 and Psalm 8 have in common the motif of man's domination over the other

creatures of the earth. Yet the "image of God" motif itself is conspicuously absent from

the psalm, as James Barr has recently emphasized: "This poetical passage [i.e., Ps 8:6-8]

is customarily associated with Genesis 1, and indeed it has close similarities with the

thought of the latter; it is likely to represent an earlier stage of the same tradition which

has come to later expression in Genesis. Nevertheless, and indeed for this very reason, it

is also important to observe that it does not use the term 'image of God', or any other

term in the semantic field of 'image, likeness, similarity', but remains within the semantic

fields of 'honour' and of 'glory, beauty'" ("The Image of God in the Book of Genesis,"

12).

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MILLLR: IN THL "IMAGL" "LIKLNLSS" OF GOD

295

the Sargonic period of Assyria's history actually use the Akkadian cognate of

selem in this context.18 (2) According to the priestly account, God bestowed a

special blessing upon man at the time of creation, establishing him in a position

of authority over the other creatures of the earth (Gen 1:28-30; 9:1-75. It is

significant to note, moreover, that the wording of this blessing is more sugges-

tive of a king's relationship to his subjects than of man's actual relationship to

the animals.19 (3) The priestly writer is also careful to note that the one char-

acteristic which most clearly distinguishes man from the other creatures-i.e., he

is in the "likeness" and "image" of God was passed on from Adam to Seth

and supposedly to each succeeding generation (Gen 5:1-3). This notation is at

least reminiscent of the Mesopotamian view reflected most clearly in the Su-

merian King List, viz., that kingship was "handed down from heaven" at the very

beginning of human history and passed on in unbroken line from king to king

thereafter.20

J. HehnS21 in 1915, seems to have been the first to interpret the "image of

l8See, e.g., Hans Wildberger, "Das Abbild Gottes," TZ 21 (1965) 245-59, 481-

501, esp. 253-55; and W. H. Schmidt, Schopfs6ngsgeschichte, 137-40.

See esp. H. Wildberger, "Das Abbild Gottes," 258-59.

bThe connection seems even more apparent in view of the striking literary simi-

larities between the priestly writer's pre-flood genealogy (Genesis 5) and the 5M6merian

King List. The names of the pre-flood patriarchs recorded in the priestly genealogy are

the same, with some slight differences in order and spelling, as those which appear in

the Yahwistic genealogies of Gen 4:17-26. These names are Palestinian in origin and the

Yahwistic geneaIogies reflect the literary form in which we would expect such genealogical

materials to have circulated in Palestine during the earlier stages of Israel's history. This

same genealogical material has been recast in the priestly source, however, into a literary

form so strikingly similar to that of the S¢mesian King List that this recasting must have

been the result of a conscious effort.

The great flood would presumably have interrupted th. continuity of the institution

of kingship which the compiler(s) of the king list wished to demonstrate. Thus it is

noted that kingship was handed down from heaven again immediately a*er the flood. The

flood would not have posed this sort of problem for the priestly writer who depicts man-

kind in general as a king and sees the continuity in the passing on of the "image of God"

characteristic from generation to generation. It is interesting to note, however, that he

follows the Mesopotamian pattern at this point as well i.e., the blessing which God be-

stowed upon man through Noah in Gen 9:1-7 is essentially a reconfirmation and expan-

sion of man's royal authority (see below).

I hope to deal with the genealogical materials in Genesis 4-5 more thoroughly in a

later study. For the moment, the reader's attention is called to W. F. Albright, "The

Babylonian Antediluvian Kings," JAOS 43 ( 1923 ) 323-29; Thorkild Jacobsen (ed. ),

The Sutnerian King List (Assyriological Studies 11; Chicago: University of Chicago,

1939 ); Marshall D. Johnson, The Purpose of the Biblical Genealogies (SNTSMS 8;

Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1969). See esp. Jacobsen's discussion of the basic

ideas, date, and purpose of the king list (pp. 138-41) and Johnson's comments concerning

the relationship between Genesis 5 and the king list (pp. 3-36, esp. p. 31).

="Zum Terminus Bild Gottes," Sacha-Pestschrift, 36-52, cited by C. Westermann,

Genesis, 203.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITEVTUE

296

God" passages in the light of the kingship ideology. His lead

lowed by several prominent scholars, including G. von Rad,22 and most recently

by H. Wildberger23 and T. H. Schmidt.24 This approach requires caution,

however, if for no other reason than it can so easily result in an oversimplifica-

tion of the issues involved. A popular exegesis of the passages in question goes

something like this: The kings of the ancient Near East often set up statues or

"images" of themselves over conquered territories to represent their authority in

their absence. Thus God has established man as his ";mage" to represent his au-

thority on the earth. CDrucial to this line of argument is the translation of the

beth in be salmenS, besogZmo, and besegem as a "beth essentiae." God created man

"s his image" rather than "in his image."

There are several problems, of course, with this sort of exegesis. While it

is true that the kings of the ancient Near East erected statles of themselves and

that these statues were olccasionally erected in conquered territories, the inscrip-

tions which appear on the statues seem to indicate that they were intended less

as representations of royal authority than as memorials to the kings and their

mighty deeds. Even if it could be demonstrated that these statues were intended

to represent royal authority in the king's absence, it is doubtful that such a prac-

tice would have been looked upon very favorably by the biblical writers. He-

brew law strictly forbade making images, or bowin.g down before, or serving

"anv likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath,

or that is in the water under the earth" (F,xod 20:4). As for the translation of

the heth as a "beth essentiae," this clearly depends more upon the necessities of

this }articular line of exegesis than upon the norms of Hebrew grammar. It is of

course theoretically possible to translate besalmeng in Gen 1:26 "vs our image,"

but the verse goes on to say: besvZmeng kigmuten. Note also that in 5:3 lzoth

the terms and the prepositions are reversed. The text reads: bidmgto kesalmo.

If we translate the beth in these passages as a "beth essentiae," how can we then

avoid translating the kogph the same way? Yet the kvph is never used in the

sense of a "kozph essentiae" elsewhere in biblical Hebrew.25

Finally, the possibility must be kept in mind that the "image of God" con-

cept originated independently of the motif concerning man's kingly position

and that the priestly writer has combined these two elements of tradition sec-

ondarily. This is suggested, in fact, by Psalm 8 and Gen 9:6. Psalm 8 stands as

evidence that the motif concerning man's dominion over the animals could be

f Genesis:

28"Das X Commentosy (Philadelphia:

Abbild Westminster, 1961) Gottes."

58.

a&Die Schopfungsgesch

26Cf. Humbert, "Atudes," 159. James Barr has also rejected the beth essertiae trans-

lation on slightly different grounds: "I think it (i.e., the beth essentiae) unlikely for our

Genesis passage (a) because it seems to be absent from the style of P and (b) because

be "in", when used in this way, seems tO indicate a property of the subject, and not of the

object,

God of the

in the Book verb17).(if there is one, as in most good cases there is not)" ("The Image of

of Genesis,"

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MILLER: IN THE "IMAGE" D "LIKENESS" OF ZD 297

transmitted and expounded without any reference at all to his creation in the

"image of God."26 On the other hand, it is apparent from the old saying in Gen

9:6, as we shall see below, that the motif of man's similarity to God could be

transmitted without any reference to his dominion over the other creatures. One

must be cautious, therefore, lest he lean too heavily upon either of these motifs in

his attempt to explain the origin and intended implications of the other. Even

in the priestly account, where these two motifs are combined, man's authority

over the animals is clearly attributed, not to his creation in the "image of God,"

but to the blessing which he received immediately following creation and which

was reconfirmed after the flood.

(d) James BarFs Tteatment of the "Imdge of God" Pvssowges: Bart's re-

cent study of the "image of God" passages27 deserves individual attention. Ac-

cording to him, the priestly writer was strongly irlfltlenced by Second Isaiah,

especially the latter's view that God could not be legitimately compared with

anyone or anything on earth.

To whom then will you liken God,

or what likeness (demut) compare with him?

The idol! A workman casts it,

and a goldsmith overlays it with goId,

and casts for it silver chains. (Isa 40:18-19)

Yet the priestly writer could not simply iarlore, as Seeend Tsaiah had done. the

traditional view that man is unique among the creatures with specific regard to

his similarity to God. If for no other reason, as Barr sees it, to do so in his cre-

ation account would have left the impression that man is nothirlg more than a

dominant animal. What the priestly writer was attempting to do in the "image

of God" passages, therefore, according to Barr, was to call attention to the God/

man similarity without specifying the nature of this similarity any more than

was absolutely necessary.

There is no reason to believe that this writer had in his mind any definite idea about

the content or the location of the image of God. There were reasons in the past de-

velopment of Israelite thinking about the relation between God and man, and in

the particular kind of literary work upon which P was engaged, which made it im-

portant for him to express the existence of a likeness between man and God; but

there were also, in the same development and especially in the whole delicacy and

questionability, according to Israelite thought, of any idea of analogies to God and

representations of God in the world, very powerful reasons why the subject could

not be more narrowly or more exactly expressed without the danger that the whole

attempt might be ruined.28

Presupposing this understanding of the priestly writer's purpose, Barr then at-

tempts to demonstrate that the other terms which fall within the same general

28 See note 17 above.

27"The Image of God in the Book of Genesis."

28 Ibid., 30.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURB

semantic range as selem would have been unsuitable for one reason or another.

Mvf'eh and tabnzt would have been unsuitable, for example, because of their

high degree of transparency i.e., they are closely associated with the verbs

ra'ah and banah. The former might have suggested, therefore, that God can be

seen; the latter might have suggested the human activity of building. Other

terms would have been unusable because of their derogatory connotations. "Pe-

sel and mvssekah were both normal designations for an object always evil, ex-

plicity forbidden by the ancient laws. Semel also is invariably negative."29

T°mralf would be disqualified on the same grounds, although Barr admits that

it could be used in relatively positive situations.

Barr's study raises a possibility which deserves careful attention, viz., that

the use of selem in the three "image of God" passages had less to do with the

term's referential value than with the priestly writer's concern to avoid some

objectionable allusion or implication. Barr's own exploration of this possibility

fails to convince, however, in at least three points: (1) Second Isaiah's com-

ments in 40:18-19 and 4645 must be understood in the context of his bitter at-

tack upon idolatry and do not necessarily imply a total rejection of the traditional

view that man is at least vaguely similar to God (or to the Elohim). Ezekiel

wotlId surely have supported this attack for example, and would have agreed with

Second Isaiah's contention that God's appearance cannot be reduced to plastic

form. We noted above that the overriding impression otle receives from Ezekiel's

description of his vision is that the appearance of God's glory defied descrip-

tion. Yet Ezekiel was also willing to speak of God's glory as having "the like-

ness as it were of a human form." (2) It is questionable whether the priestly

writer was so dependent upon the thinking of Second Isaiah as Barr's thesis re-

quires. Similarities in content and terminology are also to be observed when

the priestly stratum is compared with Ezekiel. This is especially obvious when

the "image of God" passages are compared with Ezekiel's description of his

vision of God. (3) The least convincing part of Barr's treatment of the "image

of God" passages, however, is his attempt to demonstrate that the other terms

which fall within the same general semantic range as selem would have been

Iess suitabIe for the priestly writer's purpose i.e., if one assumes with him that

this purpose was to call attention to the God/man similarity without specifying

its nature. The problem is that the same sort of arvlments which Barr uses to

disqualify these other terms could be used to disqualify seZem as well. If mvf'eh

would ha>re suggested that God can be seen, selem would surely have called to

mind the traditional view concerning man's corporeal similarity to God which,

according to Barr, the priestly writer wished to avoid.30 If peseZ, motrekah, and

semeZ were unsuitable because of the context in which they were normally used,

then we must suppose that the same was true of selem. The biblical writers ad-

sIbid., 19.

80 See, e.g., H

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1WILLBR: IN THE ' IMAGB" AND "LIKBNESS" OF GOD 299

mittedly used these other terms more often than selem when referring to pagan

idols and figurines. But when they did use selem they almost always used it for

this purpose or in a distinctly derogatory fashion.31 Num 33:52 is especially

instructive since it is the single occasion outside the three "image of God" pas-

sages where the priestly writer himself uses SeZem.32

. . . then you shall drive OUt all the inhabitants of the land from before you, and de-

stroy all their figured stones, and destroy all their molten images (kol salme mas-

sekotam) and demolish all their high places.

Ezekiel uses sele7n exclusively in reference to pagan objects, and Second Isaiah

never uses it at all.

Actually, d°mSt would seem to have been the ideal term for the priestly

writerss purpose (as understood by Barr). Barr is more conventional in his treat-

ment of d°mgt, however, agreeing with Humbert that it was included in order to

clarify or modify the implications of selem in some way.33

II

Gen 9:1-7, God's blessing of Noah after the flood, is essentially a recon-

firmation and expansion of the blessing which God had already bestowed upon

mankind at the time of creation. The expansion has to do with the eating of

meat or, more specifically, with the blood which flows in the veins of all liv-

ing creaelres. Blood was looked upon in the ancient Near East as the basic in-

gredient of life, and blood which had been shed was believed to have a dan-

gerously contaminating effect.34 Thus the priestly writer seems to have asstlmed

that man was not originally intended to eat meat and has been allowed to do so

following the flood only with the restriction that meat never be eaten with its

blood. The priestly writer also takes this occasion to emphasize another pro-

hibition concerning the shedding of blood which he believed to have been or-

dained by God i.e., the prohibition of murder, the shedding of human blood.

Specifically, he quotes at this point the old saying which prohibits the shedding

of human blood on the grounds that man was created in the "image" of God.

And God blessed Noah and his sons, and said to them, "Be fruitful and multiply,

and fill the earth. The fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of

S1The only possible exceptions are 1 Sam 6:5, 11 and Pss 39:7 and 73:20. But

selfm can hardly be considered a favorable term even in these cases.

s2Note, however, that some commentators would not assign this passage to P (eg.,

M. Noth, Ngmbers: A Commentary [Philadelphia: Westminster, 1969] 247-48).

88p. 24.

84 See esp. J. Pedersen, Israel, Its Life and Cgltgre (London: Oxford University,

1940) 315, 335, 338; Lambert and Millard, Atra-7Sfasss, 21-92; and T. H. Gaster, Myth,

Legend, and Cgstom ss the Old Testatnent (New York; Harper and Row, 1969) 65-69.

The third sentence on p. 69 includes a misprint. It should read, "This, it may be added,

is the real origin of the Biblical commandment (Genesis 9:6) against the shedding of

blood."

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE

the earth, and upon every bird of the air, upon everything that creeps on the ground

and all the fish of the sea; into your hand they are delivered. Every moving thing

that lives shall be food for you; and as I gave you the green plants, I give you every-

thing. Only you shalI not eat flesh with its life, that is, its blood. For your lifeblood

I will surely require a reckoning; of every beast I will require it and of man; of every

man's brother I will require the life of man.

Whoever sheds the blood of man,

by man shall his blood be shed;

for in the image of God,

he created man.

And you, be fruitful and multiply, bring forth abundantly on the earth and multiply

in it." (Gen 9:1-7)

Thus, white the third of the three priestly references to man's creation in

the "image of God" appears in the general context of the primordial blessing of

man, it appears more specificaIly in the context of a series of prohibitions con-

cerning the shedding of blood. The old saying which embodies this reference is

to be distinguished from the remainder of the blessing, moreover, and even from

vss. 4-5 which have also to do with the shedding of blood, on at least three

form-critical grounds: (1) Although God is supposedly pronouncing the bless-

ing arad this supposition is maintained throughout the passage, this particular

verse refers to God in the third person. (2) This verse is a carefully constructed

poeticaI statement, in contrast to the remainder of the passage which is cast in

prose. (3) This verse is a complete literary unit in itself, reflecting a literary

form which normally appears in the legaI sections of the OT.

Gtlnkel himself identified the first half of this verse, "Whoever sheds the

blood of man by man shall his blood be shed," as "ein alter Rechtsspruch,"35 but

seems to have assumed that the motive clause, "for in llis imave God created

man*" was added secondarily by the priestlv writer. Note. however, that it is the

motive cIavlse in particular of this old saying which refers to Ged irl the third

person. B. Gemser36 has observed, moreover, that several of Tsrael's oldest Iaws

are cast in rhythmic form and that this rhythmic form is maintained throughout

their motive clauses. Citing Gen. 9:6 as an example. he concludes that there is no

"insurmountable difficulty in assuming that the motive clause here is an authentic

part of the stipulation."37

If there is any difficulty at all in assumin.g the avlthenticity of the motive

clause in Gen 9:6, it is because the point of the clause is not entirely clear. That

exactly is the connection between the "shedding of blood" and man's creation in

the "image of God?" One gets the impression that a rather specific connection

is prestlpposed, but one which is no longer obvious. Note alsc) that the saying is

based on a series of assonances between the words for "bIood" (rlam) and "man"

gP. 149.

S6"The Im

50-66.

87Ibid., 64.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MILLLR: IN THL IGL D LIKLNLSS OF CD 301

('fidam). One would expect this play on words to reach a climax in the motive

dause, yet the assonances are interrupted at precisely that point by b6selem.

Jopek dam ha'adam, ba'adamdamo ysssapek

kg beselfm 'elohsm 'asah 'et-ha'adam.

If, on the other hand, one reads bSmxt rather than beseleœn in the motive clause,

the series of assonances is completed and the point of the clause becomes im-

mediately obvious-i.e., demgt creates a pun with dSm.

Iopek dom ha'adam, bo'adam damo y«ssapek

ks b«dmxt, '£10hm 'asah'et-ha'adam.

The redundant and interchangeable use of sele7n and dCmgt in the first two

"image of God" passages suggests, as we have seen, that one of these terms is a

secondary if not an intrusive element in the "image of God" tradition. Most

commentators have assumed that selem is the primary term and that Jemgt is the

secondary one, if for no other reason than that selem alone is used in Gen 9:6.

The preceding analysis of 9:6 suggests, however, that the reverse is true. It

would appear, in other words, that the pre-priestly core of the so-called "image

of God" passages is an old saying which prohibited murder on the grounds that

man was created in the "likeness" (demgt) of God. The priestly writer appar-

ently substituted selem for demgt when he incorporated this old saying into his

account, and used selem alongside demgt when he included the "likeness of God"

motif in his account of the creation of man (Gen 1:26-27) and his genealogy

of the pre-flood patriarchs (Gen 5 :1-3 ) .

The question was raised above in reaction to Humbert's widely accepted

thesis, as to why the priestly writer would have used selem at all if he considered

its implications problematic, or whether the secondary introduction of demgt

alongside selem would have clarified or modified the latter's implications in any

way. This problem becomes considerably less difficult if we approach it from

the opposite direction- i.e., if we concede that demgt was the prior term and

ask why the priestly writer might have felt it necessary to clarify the implication

of demgt with sele7r;. A reasonable explanation, in my opinion, has again to do

with this matter of the similarity between demzat and the word for "blood" (dam

in Hebrew, damg in Akkadian). It must be remembered that according to

Mesopotamian tradition the gods had in fact created man from divine blood.

The Mesopotamian view, more specifically, was that the gods had created

man from divine blood mixed with clay and charged him with the daily toil

which had previously demanded their own energies. Since the creation of man

relieved the gods from their daily toil, the natural result was that the gods were

able to rest. This dual motif of the creation of man followed by the resting of

the gods is, as W. G. Lambert has recently noted, one of the clearest Mesopota-

mian parallels to the priestly source.

On this last point (i.e., man's creation for the purpose of sening the gods and

their subsequent rest) all the Mesopotamian accounts agree; man existed solely to

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE

302

serve the gods, and this was expressed practically in that all major deities at least

had two meals set up before their statues each day. Accordingly, manss creation re-

sulted in the gods' resting, and the myths reach a climax at this point. Even in

Engma Elish this is clear, despite much conflation. At the beginning of Tablet VI Ea

and Marduk confer on what is called 'the resting of the gods,' and thereupon man

is created and the gods are declared free from toil. 1his common Mesopotamian

tradition thus provides a close parallel to the sixth and seventh days of creaiion.<8

Both the context of the priestly writer's first reference to manSs creation in the

"likeness" of God, and the similarity between the words for "likeness" and

"blood" would have immediately called to the minds of the first readers of the

priestly account, therefore, the Mesopotamian view that the gods had created

man from divine blood. There was also a possibility of confusion at this point,

due to the abstract and non-specific nature of demgt. It would have been pos-

sible, and perhaps even natural, for these first readers to suppose that the simi-

larity between God and man to which demgt refers involves not only man's gen-

cral appearance but also and even more specifically the blood which flows in his

veins. Note also what a radical change would be wrought in the meaning of Gen

9:6 (as reconstructed) if only the slightest change were made in its pronuncia-

tion-i.e., if bidmgt were read bSmo or bidtms.39

It is understandable, therefore, why the priestly writer might have felt it

necessary to clarify the implications of de4t with selem. SeZem is, to be sure, a

more specific and concrete term than we would normally have expected him to

use in view of his otherwise anti-anthropomorphic tendencies. But it was pre-

cisely the concrete and specific nature of the term which rendered it useful in

this case. Selem specifies, namely, that the divine similarity to which demgt re-

fers is confined to man's general corporeal appearance and has nothing to do

with the blood which flows in his veins.

If the hypothesis proposed above is found acceptable, the tradition-history

of the so-called "image of God" concept may be reconstructed essentially as fol-

lows:

(1) The pre-priestly core of the so-called "image of God" passages is an

old "Rechtsspruch" which, in its original form, prohibited the shedding of hu-

man blood (dam) on the grounds that man was created in the "likeness"

(demgt) of God. This old saying reflects a view which was widely held among

the peoples of the ancient Near East, including Israel- i.e., that man is similar

to the gods, especially with regard to his corporeal appearance.

(2) Both Second Isaiah and Ezekiel use the term demut in reference to

God's appearance. Second Isaiah scoffs at the idea that God could be adequately

represented in plastic form, "to whom then will you liken God, or what likeness

38W. G. Lambert, "A New Look at the Babylonian Background of Genesis,>> JTS 16

( 1965 ) 287-300, esp. p. 298.

39The possibility cannot be completely ignored, of course, that this saying did reflect

the pagan view in its original form and that it has been revised in content as well as

terminology by the priestly writer.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MILLBR: IN THB IGB" AND LIENESS OF GOD 303

(demgt) compare with him?" And Ezekiel, in the description of his vision, uses

demgt to create the impression that God's glory actually defied description in

spite of the vague resemblance to a human form. The priestly writer seems to

have held a position very similar to that of Ezekiel. Just as Ezekiel, in spite of

his realization that God's glory defied adequate description, indicates that it

"had the appearance as it were of a human form" (demgt kemarDeh 'Xam), so

the priestly writer, well known for his otherwise anti-anthropomorphic tenden-

cies, contends that man was created in the demgt of God.

( 3 ) The priestly account of creation and the origins of human civilization

in Genesis 1-11 is to be understood against the background of the Mesopotamian

traditions. It is significant to note, for example, that the priestly account pre-

supposes essentially the same order of primordial events as do the Mesopotamian

documents i.e., the establishment of order in the universe, followed in tulrn

by the creation of man, the resting of the gods, the establishment of kingship, a

succession of pre-flood kings with fantastically long reigns, the great flood, and

finally the re-establishment of kingship.4° But the dissimilarities between the

priestly account and the Mesopotamian traditions are equaLly significant. The

priestly writer speaks of one God rather than many and maintains a clear dis-

tinction between this God and his creation. Man, according to the priestly writer,

was not created from divine "blood" (dam) but in the divine "likeness"

(demgt). Man's primary purpose is to rule over the creatures of the earth

rather than to serve the gods, and God's rest which followed man's creation is

explained on entirely different grounds. The priestly writer naturally rejected

the belief that the authority of the Mesopotamian kings had been divinely or-

dained at the beginning of human history and insisted, instead, that it is the di-

vine "likeness" which has been passed down from generation to generation since

creation. The flood was decreed, according to him, not because people were so

noisy that they kept the gods awake, but because the earth was corrupt (nssha-

tah) in God's sight and filled with violence (hamas). Noah escaped, not by out-

witting God and defeating his plan, but in accordance with God's plan.

In short, the priestly writer seems to have affirmed the order of primeval

events presupposed by the Mesopotamian myths, and may have even patterned

his own account after a Mesopotamian prototype. Yet he radically modified the

basic concepts and motifs reflected in the Mesopotamian myths and substituted

details from his own Hebrew heritage. His dual emphasis uporl man's creation

40None of the Mesopotamian documents recovered thus far actually include all the

elements of this pattern. The Atrahasss Epic is the most complete in t}liS regard, includ-

ing the creation of man, the resting of the gods, and the flood. It may have also dealt

with the establishment of kingship and the pre-flood kings, but this is uncertain due to

the fragmentary nature of the tablets. The Enutna Elish describes the creation of man

and implies the resting of the gods, but the matters of kingship and the flood were not

pertinent to its purpose. It is possible also that the 5a4merian King List did not in its

earliest form mention the flood. The flood motif has been incorporated secondarily into

the G;lgatnesh Ep«c.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

304 JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LlTLMTUE

in the "likeness" of God and man's royal status among the creatures is to be un-

derstood in this light. It represents, namely, a conscious rejection of the assump-

tion that the gods had created man with their own blood and had established the

authority of the Mesopotamian kings at the beginning of human history.

(4) The similariw of sound between the words for "likeness" and "blood"

rendered the concept that God had created man in his own "likeness" an espe-

cially effective counter to the popular view that the gods had created man from

divine "blood." But the non-specific and abstract nature of demut would also

have allowed for confusion between the two concepts. It was in order to avoid

any such confusion that the priestly writer introduced the more specific term,

selens into his account. The use of a second term alongside demut posed l10

problem in Gen 1:26-27 and 5:1-3, although it resulted in an obvious redundan-

cy. The situation was more complicated in 9:6, however, where the poetical

structure of the old saying was at stake. It was necessary in this latter case,

therefore, to replace demut with selem altogether. The careful distinction which

the priestly writer attempted to emphasize by the introduction of selem would

have been especially obvious to his contemporaries, of course, who knew the old

saying in its original form.41

41 It is possible, of course, that the priestly writer's introduction of selfm was also in-

fluenced by the royal ideology of the ancient world. If he was familiar with the practice

of referring to kings as "images' of their gods-and there is no reason to doubt that

he would have been he may have introduced sflfm into his creation account in order

to further emphasize man s lofty position in the created order and authority over the other

creatures. It is questionable, on the other hand, whether the term sflem was so closely

associated with the royal ideology as this explanation would require. While it is true that

three Akkadian texts refer to Assyrian kings as "images" (salmg4) of their gods, salmg4

does not seem to be one of the terms most often used in this context, and sflfm is never

used in connection with the kings of Israel. We have noted as well that sZem is con-

spicuously absent from Psalm 8. The fact that sflem has become the dominating term

specifically in Gen 1:26-27 and 9:6 is also noteworthy. Clarification was especially ur-

gent in these two cases. The former passage parallels the dual pagan motif concerning the

creation of man from divine blood and the subsequent resting of the gods, while the latter

appears in the context of a series of prohibitions concerning blood and calls attention to

the demgt/dam similarity. In Gen 5:1-3, on the other hand, wllich is the least suggestive

of the three passages regarding the blood motif, yet the one which seems most obviously

r.miniscent of the kingship ideology, demg2t remains the dominating term.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:16:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- ShraddhA SUktam - ShAnti SUktamDocument6 pagesShraddhA SUktam - ShAnti SUktamSriram Sundararajan100% (1)

- Symbaroum - The Art of SymbaroumDocument56 pagesSymbaroum - The Art of SymbaroumThibault Mlt Ericson100% (2)

- Q2 MODULE 4 Creative NonfictionDocument14 pagesQ2 MODULE 4 Creative NonfictionMarissa Dulay - Sitanos100% (9)

- Waltke Crux Genre GenesisDocument9 pagesWaltke Crux Genre GenesisJosé BarajasNo ratings yet

- The Early History of Heaven PDFDocument337 pagesThe Early History of Heaven PDFCarlos Cordus100% (5)

- One Act Play SamplesDocument2 pagesOne Act Play SamplesD Garcia100% (1)

- Clifford - 2016 - Creation Genesis 11-23Document9 pagesClifford - 2016 - Creation Genesis 11-23Carlos Cesar BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Decker 2014 - Live Long in The Land The Covenantal Langage of The OT Allusions in Message To Laodicea PDFDocument31 pagesDecker 2014 - Live Long in The Land The Covenantal Langage of The OT Allusions in Message To Laodicea PDFAndrew ButlerNo ratings yet

- Fallen Angels and Genesis 6 1-4-2000 DSDDocument25 pagesFallen Angels and Genesis 6 1-4-2000 DSDiraklis sidiropoulosNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Sommer, A Commentary On Psalm 24Document22 pagesBenjamin Sommer, A Commentary On Psalm 24stelianpascatusaNo ratings yet

- 05-3 17 PDFDocument13 pages05-3 17 PDFAbraham TonapaNo ratings yet

- Paul Copan vs. John MacArthur On Genesis 1Document4 pagesPaul Copan vs. John MacArthur On Genesis 1api-3769729100% (1)

- Brian Schultz - Jesus As Archelaus in Parable of PoundsDocument24 pagesBrian Schultz - Jesus As Archelaus in Parable of PoundsChris SchelinNo ratings yet

- The Jerusalem Bible New VersionFrom EverandThe Jerusalem Bible New VersionCTAD EditionsNo ratings yet

- Stuckenbruck AngelsGiantsGenesis 2000Document25 pagesStuckenbruck AngelsGiantsGenesis 2000artsan3No ratings yet

- The Hebrew Scriptures and The TheologyDocument18 pagesThe Hebrew Scriptures and The TheologyDavid EinsteinNo ratings yet

- The American Journal of Philology Vol. 100, No. 4 (Winter, 1979), Pp. 497-514Document19 pagesThe American Journal of Philology Vol. 100, No. 4 (Winter, 1979), Pp. 497-514MartaNo ratings yet

- YEC Summary Defense PDFDocument13 pagesYEC Summary Defense PDFGilson FernandesNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press The Biblical WorldDocument12 pagesThe University of Chicago Press The Biblical WorldAlvie MontejoNo ratings yet

- The Creation of Light in Genesis 1:3-5Document9 pagesThe Creation of Light in Genesis 1:3-5Sveto PismoNo ratings yet

- Chapter3 - What About Gap TheoriesDocument13 pagesChapter3 - What About Gap Theoriesmichael_vermaakNo ratings yet

- Antony F. Campbell (1979) - Yahweh and The Ark. A Case Study in Narrative. Journal of Biblical Literature 98.1, Pp. 31-43Document14 pagesAntony F. Campbell (1979) - Yahweh and The Ark. A Case Study in Narrative. Journal of Biblical Literature 98.1, Pp. 31-43wilfredo torresNo ratings yet

- The Formation of The Biblical NarrativeDocument29 pagesThe Formation of The Biblical NarrativeJose PinedaNo ratings yet

- THE THREE-STORY UNIVERSE - A Comparision of The Cosmology of The Ancient Near East PDFDocument12 pagesTHE THREE-STORY UNIVERSE - A Comparision of The Cosmology of The Ancient Near East PDFemschmidtNo ratings yet

- Final Exegetical PaperDocument6 pagesFinal Exegetical Paperapi-659775263No ratings yet

- CCRS Old Testament Essay 20.04.07Document9 pagesCCRS Old Testament Essay 20.04.07Richard PotterNo ratings yet

- Some Observations On The Origin ofDocument18 pagesSome Observations On The Origin ofArmandoVerbelDuqueNo ratings yet

- Donald E. Gowan Eschatology in The Old Testament 2000Document175 pagesDonald E. Gowan Eschatology in The Old Testament 2000Aleksandar Vasileski100% (2)

- This Content Downloaded From 197.40.63.213 On Sun, 15 Aug 2021 15:42:47 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 197.40.63.213 On Sun, 15 Aug 2021 15:42:47 UTCPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Context and Contextualization of AncientDocument51 pagesContext and Contextualization of AncientDavid EinsteinNo ratings yet

- The History of The Motto of RutgersDocument36 pagesThe History of The Motto of RutgersJessicaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 - PentateuchDocument19 pagesAssignment 1 - PentateuchCressida ShindleNo ratings yet

- Creation Matters 1998, Volume 3, Number 1Document8 pagesCreation Matters 1998, Volume 3, Number 1KerbspannungslehreNo ratings yet

- God and IlluvatarDocument11 pagesGod and IlluvatarakimelNo ratings yet

- Cycles of Salvation History: Genesis, the Flood and Marian ApparitionsFrom EverandCycles of Salvation History: Genesis, the Flood and Marian ApparitionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Why Prophecy Ceased by Frederick E. GreenspahnDocument14 pagesWhy Prophecy Ceased by Frederick E. GreenspahnAtmavidya1008No ratings yet

- Natural World in The Book of JoelDocument18 pagesNatural World in The Book of JoelFdaNo ratings yet

- Estudos DiversosDocument24 pagesEstudos DiversosHuddyNo ratings yet

- Isaiah XXI, A PalimpsetDocument169 pagesIsaiah XXI, A PalimpsetPasca Szilard100% (1)

- Genesis PDFDocument93 pagesGenesis PDFKing James Bible BelieverNo ratings yet

- Stern Bookdeuteronomy 2020Document35 pagesStern Bookdeuteronomy 2020Páll LászlóNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Article "21 Reasons To Believe The Earth Is Young" by Jeff MillerDocument25 pagesCritical Analysis of Article "21 Reasons To Believe The Earth Is Young" by Jeff MillerRaw TulumNo ratings yet

- The Origin of the World According to Revelation and ScienceFrom EverandThe Origin of the World According to Revelation and ScienceNo ratings yet

- 04 BERCHIE Different ApproachesDocument9 pages04 BERCHIE Different ApproachesJuan Carmelo Morales AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Proverbs 30:18-19 in The Light of Ancient Mesopotamian: Cuneiform TextsDocument18 pagesProverbs 30:18-19 in The Light of Ancient Mesopotamian: Cuneiform TextsMarlin ReyesNo ratings yet

- Where Did The Earth Come FromDocument21 pagesWhere Did The Earth Come FromdikoalamNo ratings yet

- William Brown - Creation in The Old TestamentDocument44 pagesWilliam Brown - Creation in The Old Testamentcesarrmoreno6983No ratings yet

- DeuteronomyDocument137 pagesDeuteronomymarfosdNo ratings yet

- Genesis PDFDocument508 pagesGenesis PDFLuísFernandoRibeiroDeSouzaAlvesNo ratings yet

- Short Study: Jack CollinsDocument8 pagesShort Study: Jack CollinsRazia MushtaqNo ratings yet

- JACKSON. The Bible and The Genesis Account of CreationDocument11 pagesJACKSON. The Bible and The Genesis Account of CreationMiguel Ángel NúñezNo ratings yet

- 13 Levinson JAOS130 1.3 LibreDocument12 pages13 Levinson JAOS130 1.3 LibreKeung Jae LeeNo ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument3 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldYami FubukiNo ratings yet

- BarclayDocument7 pagesBarclayMonika Prša50% (2)

- This Content Downloaded From 213.233.49.242 On Mon, 10 May 2021 08:27:09 UTCDocument34 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 213.233.49.242 On Mon, 10 May 2021 08:27:09 UTCCentinela de la feNo ratings yet

- Divine Insinuation in The 'Panegyrici Latini'Document37 pagesDivine Insinuation in The 'Panegyrici Latini'hNo ratings yet

- Simply From The Scriptures: From The Church of Christ in Richmond IndianaDocument3 pagesSimply From The Scriptures: From The Church of Christ in Richmond IndianaThe Richmond Church of ChristNo ratings yet

- Divine Fluidity The Priestly Texts in THDocument25 pagesDivine Fluidity The Priestly Texts in THblackmelehNo ratings yet

- In The BeginningDocument59 pagesIn The BeginningJanice Frankel BlockNo ratings yet

- Tohu Va BohuDocument29 pagesTohu Va BohuDimitris Mcmxix100% (1)

- Bible Before Books: A New Year's ResolutionDocument8 pagesBible Before Books: A New Year's ResolutionPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- What Will Make Our Children Happy?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdDocument9 pagesWhat Will Make Our Children Happy?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Yawning at Majesty: How To Fight Boredom With The BibleDocument10 pagesYawning at Majesty: How To Fight Boredom With The BiblePishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Are You Hiding From God's Voice?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdDocument9 pagesAre You Hiding From God's Voice?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Desiringgod Org Articles I Never Knew YouDocument1 pageDesiringgod Org Articles I Never Knew YouPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Unashamed of The Bible: Ten Aspirations For Christian CommunicatorsDocument14 pagesUnashamed of The Bible: Ten Aspirations For Christian CommunicatorsPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Desiringgod Org Articles Bright Hope From YesterdayDocument1 pageDesiringgod Org Articles Bright Hope From YesterdayPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Old TestamentDocument3 pagesOld TestamentPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- God Wrote A Book: The Wonder of Having His WordsDocument11 pagesGod Wrote A Book: The Wonder of Having His WordsPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 197.40.63.213 On Sun, 15 Aug 2021 15:42:47 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 197.40.63.213 On Sun, 15 Aug 2021 15:42:47 UTCPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:36:11 UTCDocument24 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:36:11 UTCPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- American Schools of Oriental ResearchDocument9 pagesAmerican Schools of Oriental ResearchPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Desiringgod Org Articles Tempt Him To Apologize For GodDocument1 pageDesiringgod Org Articles Tempt Him To Apologize For GodPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

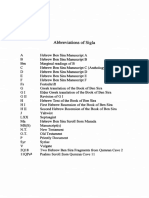

- Abbreviations of SiglaDocument1 pageAbbreviations of SiglaPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Ezekiel, P, and The Priestly SchoolDocument9 pagesEzekiel, P, and The Priestly SchoolPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- The Tabernacle and The Temple in Ancient Israel: Michael M. HomanDocument12 pagesThe Tabernacle and The Temple in Ancient Israel: Michael M. HomanPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- (9789004324732 - Sibyls, Scriptures, and Scrolls) The Social Location of The Scribe in The Second Temple PeriodDocument16 pages(9789004324732 - Sibyls, Scriptures, and Scrolls) The Social Location of The Scribe in The Second Temple PeriodPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- To Heaven With The Devil: The Importance of Satan's Salvation For God's Goodness in The Works of Gregory of NyssaDocument16 pagesTo Heaven With The Devil: The Importance of Satan's Salvation For God's Goodness in The Works of Gregory of NyssaPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:42:04 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:42:04 UTCPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Confronting Antisemitism NewDocument1 pageConfronting Antisemitism NewPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- How To Answer A Fool and To Translate THDocument30 pagesHow To Answer A Fool and To Translate THPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Holy or Foolish Gnostic Concept S of TheDocument18 pagesHoly or Foolish Gnostic Concept S of ThePishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Was Moses The Mudawwin of The Torah TheDocument33 pagesWas Moses The Mudawwin of The Torah ThePishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Bible TranslationDocument11 pagesBible TranslationPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Shall Not The Judge of All The Earth DoDocument37 pagesShall Not The Judge of All The Earth DoPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- G Barbiero M Pavan J Schnocks Edd The FoDocument2 pagesG Barbiero M Pavan J Schnocks Edd The FoPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Mwalimu Nyerere Engages His People ScripDocument13 pagesMwalimu Nyerere Engages His People ScripPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- MT, 44 (1) - BRDocument3 pagesMT, 44 (1) - BRPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Belonging: Research Commissioned byDocument46 pagesBelonging: Research Commissioned byPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - DOCTRINE - Adullt Sunday School Material - TEACHER's GUIDE - Committee On Christian Education - TMIQDocument2 pagesLesson 1 - DOCTRINE - Adullt Sunday School Material - TEACHER's GUIDE - Committee On Christian Education - TMIQiamoliver_31No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledMeyman WaruwuNo ratings yet

- (Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 88, No. 2) Dennis J. McCarthy - The Symbolism of Blood and Sacrifice-The Society of Biblical Literature (1969)Document21 pages(Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 88, No. 2) Dennis J. McCarthy - The Symbolism of Blood and Sacrifice-The Society of Biblical Literature (1969)Chirițescu AndreiNo ratings yet

- Lewis Carroll - Photography On The MoveDocument258 pagesLewis Carroll - Photography On The MoveAlsa Man100% (4)

- Daat Zkenim On Numbers - Tranlated by Eliyahu MunkDocument125 pagesDaat Zkenim On Numbers - Tranlated by Eliyahu MunkMarianaNo ratings yet

- ABC Poems - Alphabet PoemsDocument11 pagesABC Poems - Alphabet PoemsMonaifah SultanNo ratings yet

- ЛСА Калинина Алена,7171Document2 pagesЛСА Калинина Алена,7171Алена КалининаNo ratings yet

- Warwick Bans The Term 'Trigger Warnings' Due To Its Potential To Upset StudentsDocument18 pagesWarwick Bans The Term 'Trigger Warnings' Due To Its Potential To Upset StudentsJenniferNo ratings yet

- Scha DLP Year 2Document6 pagesScha DLP Year 2sweetzazaNo ratings yet

- Pace BusDocument1 pagePace BusAaron Bazil100% (1)

- Lyric Gallows PoleDocument10 pagesLyric Gallows PolecrdewittNo ratings yet

- Engl6100 - Prelim ExamDocument22 pagesEngl6100 - Prelim ExamClang MedinaNo ratings yet

- Malcolm Knox - The Wonder Lover (Extract)Document36 pagesMalcolm Knox - The Wonder Lover (Extract)Allen & UnwinNo ratings yet

- How To Write References in Research PaperDocument7 pagesHow To Write References in Research Paperhbkgbsund100% (1)

- Moving OnDocument2 pagesMoving OnDervalThomasNo ratings yet

- Webber Think of Me From The Phantom of The Opera ViolinDocument3 pagesWebber Think of Me From The Phantom of The Opera ViolinAnastasiia TunikNo ratings yet

- Samskaras and OriginDocument22 pagesSamskaras and Origins1234tNo ratings yet

- DeconstructionDocument14 pagesDeconstructionJauhar JauharabadNo ratings yet

- 24 - Jeremiah PDFDocument283 pages24 - Jeremiah PDFGuZsolNo ratings yet

- LimerickDocument3 pagesLimerickIoana MariaNo ratings yet

- UnknownDocument4 pagesUnknownSanjuktaNo ratings yet

- Domestication or Foreignization: A Message or The Message?Document12 pagesDomestication or Foreignization: A Message or The Message?Yiyong01No ratings yet

- Writing Your Own Song Charts PDFDocument8 pagesWriting Your Own Song Charts PDFYetifshum100% (1)

- Becoming Muhammad Ali: Home Kids' BooksDocument4 pagesBecoming Muhammad Ali: Home Kids' BooksMunezero GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Did God Fulfill Every Good Promise?: Toward A Biblical Understanding of Joshua 21:43-45Document29 pagesDid God Fulfill Every Good Promise?: Toward A Biblical Understanding of Joshua 21:43-45David SalazarNo ratings yet

- 3.contractul International de AgentieDocument13 pages3.contractul International de Agentietatianafrunze73481 FrunzeNo ratings yet