Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Residents of An Assisted Living Facility

Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Residents of An Assisted Living Facility

Uploaded by

Norma Alejandra AbrenaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Onan DKD Service Manual PDFDocument71 pagesOnan DKD Service Manual PDFStalin Paul Rodriguez Leon100% (3)

- Confined Space Entry Procedure WorksheetDocument5 pagesConfined Space Entry Procedure WorksheetToma AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Are Nurses Ready - Disaster Preparedness in - 2008 - Australasian Emergency Nur PDFDocument10 pagesAre Nurses Ready - Disaster Preparedness in - 2008 - Australasian Emergency Nur PDFHikmat PramajatiNo ratings yet

- Advanced Space Hulk v1.0Document92 pagesAdvanced Space Hulk v1.0adlard_matthew100% (2)

- 1 s2.0 0022437596869787 MainDocument2 pages1 s2.0 0022437596869787 MainLanlan WeiNo ratings yet

- Quan L. Do Parents Value Drowning Prevention Information at Discharge From The Emergency DepartmentDocument4 pagesQuan L. Do Parents Value Drowning Prevention Information at Discharge From The Emergency DepartmentVictoriaMuroNo ratings yet

- Icnirp SCI Review: Review of The Epidemiologic Literature On Emf and HealthDocument24 pagesIcnirp SCI Review: Review of The Epidemiologic Literature On Emf and HealthAshu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Disaster Preparedness Among Older Japanese Adults With Longterm Care Needs and Their Family CaregiversDocument8 pagesDisaster Preparedness Among Older Japanese Adults With Longterm Care Needs and Their Family Caregiversistianna nurhidayatiNo ratings yet

- Caring Lansia Dalam BencanaDocument5 pagesCaring Lansia Dalam Bencanaistianna nurhidayatiNo ratings yet

- Burn Prevention and First Aid KnowledgeDocument6 pagesBurn Prevention and First Aid KnowledgeBudi SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Student: AwarenessDocument4 pagesStudent: Awarenessoendila debnathNo ratings yet

- Phelan 2018Document16 pagesPhelan 2018Santiago MayorNo ratings yet

- Nov 23 Trauma Geriátrico Hruska 2018Document17 pagesNov 23 Trauma Geriátrico Hruska 2018lfc2086No ratings yet

- Siddharama M Bolakotagi: E-ISSN: 2664-1666 P-ISSN: 2664-1658Document5 pagesSiddharama M Bolakotagi: E-ISSN: 2664-1666 P-ISSN: 2664-1658Mamata BeheraNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 13185Document13 pagesIjerph 19 13185hello mircadoNo ratings yet

- Patient Analytical Report On BurnsDocument57 pagesPatient Analytical Report On Burnsisnaira imamNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Trauma Life Support 3e Update 2017 FINALDocument21 pagesPediatric Trauma Life Support 3e Update 2017 FINALAnita MacdanielNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument13 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptGeorge UngureanuNo ratings yet

- Clarke S. Et Al (2017) Conscientious Objection To VaccinationDocument7 pagesClarke S. Et Al (2017) Conscientious Objection To VaccinationSANDHYANo ratings yet

- 6.children in DisasterDocument76 pages6.children in DisasterIsmail SlimNo ratings yet

- How Lightning Kills and Injures: Corresponding Author Address: Mary Ann CooperDocument3 pagesHow Lightning Kills and Injures: Corresponding Author Address: Mary Ann Cooperjuan832No ratings yet

- First Page PDFDocument1 pageFirst Page PDFRatna HidayatiNo ratings yet

- Uncorrected Manuscript: Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older PeopleDocument9 pagesUncorrected Manuscript: Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older PeopleKiky HaryantariNo ratings yet

- Infant Deaths - Is There An Association With Vaccines - by Julian Gillespie, LLB, BJurisDocument11 pagesInfant Deaths - Is There An Association With Vaccines - by Julian Gillespie, LLB, BJurisSY LodhiNo ratings yet

- Adult ImmunizationsDocument12 pagesAdult ImmunizationsredroseeeeeeNo ratings yet

- Melanoma - PregradoDocument8 pagesMelanoma - PregradoDaniela DuránNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Outcomes of Burn Injuries at A Tertiary Burn Care Center in BangladeshDocument7 pagesEpidemiology and Outcomes of Burn Injuries at A Tertiary Burn Care Center in BangladeshE.sundara BharathiNo ratings yet

- Communicating The Benefits and Risks of VaccinesDocument8 pagesCommunicating The Benefits and Risks of VaccinesBrandeice BarrettNo ratings yet

- 6 Promoting SafetyDocument30 pages6 Promoting SafetyFaisal QureshiNo ratings yet

- Older Adults' Attitudes To Death, Palliative Treatment and Hospice CareDocument9 pagesOlder Adults' Attitudes To Death, Palliative Treatment and Hospice CarefiennesrnNo ratings yet

- Initial Management of Seizure in Adults: Clinical PracticeDocument13 pagesInitial Management of Seizure in Adults: Clinical PracticeMatthew MhlongoNo ratings yet

- Logistical and Structural Challenges Are The Major Obstacles For Family Medicine Physicians' Ability To Administer Adult VaccinesDocument7 pagesLogistical and Structural Challenges Are The Major Obstacles For Family Medicine Physicians' Ability To Administer Adult Vaccinescarla laureanoNo ratings yet

- Preventive Measures For Fire-Related Injuries and Their Risk Factors in Residential Buildings: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesPreventive Measures For Fire-Related Injuries and Their Risk Factors in Residential Buildings: A Systematic ReviewTR NahidNo ratings yet

- PEDIATRIC BURN Clin NorthDocument8 pagesPEDIATRIC BURN Clin NorthRaul PerezNo ratings yet

- doença de alzheimerDocument17 pagesdoença de alzheimerBeatriz PaivaNo ratings yet

- Prevenção QuedasDocument10 pagesPrevenção Quedasgabrielapetitot_9179No ratings yet

- Radiation and ChildrenDocument2 pagesRadiation and ChildrenNikki No-NukesNo ratings yet

- Sample Case StudyDocument23 pagesSample Case StudyDELFIN, Kristalyn JaneNo ratings yet

- A Review of Electrical Burns Admitted in A Philippine Tertiary Hospital Burn CenterDocument5 pagesA Review of Electrical Burns Admitted in A Philippine Tertiary Hospital Burn CenterRiza Paula LabagnoyNo ratings yet

- Natural History of Burnout Stress and Fatigue in A Pediatric Resident CohortDocument10 pagesNatural History of Burnout Stress and Fatigue in A Pediatric Resident CohortIkunda IsmaelNo ratings yet

- Science of Risk AssessmentDocument4 pagesScience of Risk AssessmentDrBishnu Prasad MahalaNo ratings yet

- Keinginan 1 PDFDocument11 pagesKeinginan 1 PDFMerySeprianiNo ratings yet

- Daniels Et Al (2015) 508Document9 pagesDaniels Et Al (2015) 508Forum PompieriiNo ratings yet

- Baldwin 2016Document10 pagesBaldwin 2016Nahda Fini SNo ratings yet

- HSJ Vol.9no.2 2020-31-37Document7 pagesHSJ Vol.9no.2 2020-31-37ROSALINDA BULANo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 (K)Document17 pagesPractical Research 1 (K)Joshua ValledorNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Childhood Leukemia: A Comprehensive Literature ReviewDocument37 pagesRisk Factors For Childhood Leukemia: A Comprehensive Literature Reviewmisbahhari_mdNo ratings yet

- Afaa 274Document5 pagesAfaa 274arman ahdokhshNo ratings yet

- Injury Risks of EMS Responders: Evidence From The National Fire Fighter Near-Miss Reporting SystemDocument9 pagesInjury Risks of EMS Responders: Evidence From The National Fire Fighter Near-Miss Reporting SystemAna OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Care in Disasters 2013Document6 pagesPediatric Care in Disasters 2013Cris TobalNo ratings yet

- Early-Onset Basal Cell CarcinomaDocument11 pagesEarly-Onset Basal Cell CarcinomajxmackNo ratings yet

- Level of Awareness of Criminology Students On CBRN Issues F2 PDFDocument33 pagesLevel of Awareness of Criminology Students On CBRN Issues F2 PDFRODOLFO RUBISNo ratings yet

- Disaster Nursing SAS Session 20Document5 pagesDisaster Nursing SAS Session 20Niceniadas CaraballeNo ratings yet

- Niehs PDFDocument2 pagesNiehs PDFagusNo ratings yet

- Fpubh 01 00040 PDFDocument2 pagesFpubh 01 00040 PDFMeidy RamschieNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Ring Injury in The Elderly Fragile Patients With Substancial Mortality Rates and Long Term Physical Impairment. 2019Document12 pagesPelvic Ring Injury in The Elderly Fragile Patients With Substancial Mortality Rates and Long Term Physical Impairment. 2019Gonzalo JimenezNo ratings yet

- Radiation Safety Paper - Kristen DezellDocument4 pagesRadiation Safety Paper - Kristen Dezellapi-568316609No ratings yet

- Public Perception 1Document8 pagesPublic Perception 1Calvin SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Burn Contracture Outcome in Developing CountriesDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting Burn Contracture Outcome in Developing CountriesWahyu IndraNo ratings yet

- Lived Experiences of Regular Volunteer Emergency First Responders A Phenomenological ResearchDocument12 pagesLived Experiences of Regular Volunteer Emergency First Responders A Phenomenological ResearchInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument25 pagesAcute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaJavierNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older People: Roy L. Soiza, Chiara Scicluna, Emma C. ThomsonDocument5 pagesEfficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older People: Roy L. Soiza, Chiara Scicluna, Emma C. ThomsonMauricioNo ratings yet

- WSES Handbook of Mass Casualties Incidents ManagementFrom EverandWSES Handbook of Mass Casualties Incidents ManagementYoram KlugerNo ratings yet

- Integrals QUIZDocument3 pagesIntegrals QUIZNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Royal Society For The Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Journal of The Royal Society of ArtsDocument8 pagesRoyal Society For The Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Journal of The Royal Society of ArtsNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Contribution To The Investment Evaluation in Terms of The Forest Fires Prevention Using The Cost-Benefit Analysis MethodDocument13 pagesContribution To The Investment Evaluation in Terms of The Forest Fires Prevention Using The Cost-Benefit Analysis MethodNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Hazardous Material Accidents With Mass Casualties Prevention Strategies by Hamburg Fire BrigadeDocument2 pagesHazardous Material Accidents With Mass Casualties Prevention Strategies by Hamburg Fire BrigadeNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- MonologueDocument1 pageMonologueNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Receiving The Unshakeable Kingdom of GodDocument3 pagesReceiving The Unshakeable Kingdom of GodNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Year 9 English Examination 2014Document19 pagesYear 9 English Examination 2014api-246403506No ratings yet

- Pokemon Red Rescue Faq by HswbazDocument44 pagesPokemon Red Rescue Faq by HswbazHafiz Maulana AhmadNo ratings yet

- 英语作文高级替换词Document14 pages英语作文高级替换词sqhaaNo ratings yet

- Mark BFPDocument3 pagesMark BFPmarz sidNo ratings yet

- Fire Sprinkler - ABCB Reference Document - Automatice Fire Sprinkler SystemDocument193 pagesFire Sprinkler - ABCB Reference Document - Automatice Fire Sprinkler SystemJeffrey WalkerNo ratings yet

- FMDS0102Document69 pagesFMDS0102hhNo ratings yet

- 7-88 Flammable Liquid Storage TanksDocument44 pages7-88 Flammable Liquid Storage TanksAchraf BoudayaNo ratings yet

- Maintenance (22.09.2022)Document2 pagesMaintenance (22.09.2022)Imelisya JaulinNo ratings yet

- Fire PPT CompilationDocument9 pagesFire PPT CompilationDonna Mae MartinezNo ratings yet

- Qatar Civil Defence ExaminationDocument10 pagesQatar Civil Defence Examinationali.abk2017No ratings yet

- Foaming AgentsDocument6 pagesFoaming AgentsrmaffireschoolNo ratings yet

- Emergency Evacuation PlanDocument14 pagesEmergency Evacuation PlanGlenn MadeloNo ratings yet

- Emergency Evacuation Plans and ExercisesDocument12 pagesEmergency Evacuation Plans and ExercisesSamier MohamedNo ratings yet

- The Flixborough, UK, Cyclohexane Disaster, 1 June 74Document24 pagesThe Flixborough, UK, Cyclohexane Disaster, 1 June 74rodofgodNo ratings yet

- Aosh Assessment QuestionDocument7 pagesAosh Assessment QuestionMd Imran HossainNo ratings yet

- Subject: Invitation To Join As "Resource Speaker" On Our Seminar On Fire Prevention and Safety ConsciousnessDocument6 pagesSubject: Invitation To Join As "Resource Speaker" On Our Seminar On Fire Prevention and Safety ConsciousnessRjay CadaNo ratings yet

- FIRE PREVENTION NSTPDocument7 pagesFIRE PREVENTION NSTPmariel rose bandeNo ratings yet

- Aux Boiler Fire Case StudyDocument3 pagesAux Boiler Fire Case StudyasNo ratings yet

- Buku Saku Proteksi Kebakaran 2022Document25 pagesBuku Saku Proteksi Kebakaran 2022rajaNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Emergency PlanDocument35 pagesLaboratory Emergency PlanMß WæžəəřNo ratings yet

- Fire DrillsDocument10 pagesFire Drillseliasox123100% (2)

- FO1 Journal 10000Document43 pagesFO1 Journal 10000Alta Tierra FssNo ratings yet

- Hazard AssessmentDocument2 pagesHazard AssessmentRahul ShajiNo ratings yet

- Protego PDFDocument18 pagesProtego PDFNemezis1987No ratings yet

- U42 Schlumberger MsdsDocument7 pagesU42 Schlumberger Msdsjangri1098No ratings yet

- Makati City Fire Station: Fire and Life Safety SeminarDocument60 pagesMakati City Fire Station: Fire and Life Safety SeminarAireen TanioNo ratings yet

- Unit 19Document14 pagesUnit 19Ashwani tyagiNo ratings yet

Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Residents of An Assisted Living Facility

Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Residents of An Assisted Living Facility

Uploaded by

Norma Alejandra AbrenaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Residents of An Assisted Living Facility

Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Residents of An Assisted Living Facility

Uploaded by

Norma Alejandra AbrenaCopyright:

Available Formats

BRIEF REPORT

Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices Among

Residents of an Assisted Living Facility

David Jaslow, MD, MPH; 1 2 Jacob Ufberg, MD; 1 Russell Yoon, MD; 1 Clay McQueen;2

Derek Zecher, PA-C, EMT;1-2 Greg Jakubowski, MS, EMT 2

Abstract

1. Temple University Department of Introduction: Assisted living facilities (ALFs) pose unique fire risks to the

Emergency Medicine, Division of EMS, elderly that may be linked to specific fire safety (FS) practices.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Objective: To evaluate self-reported FS practices among ALF residents.

2. Bryn Athyn Fire Company, Bryn Athyn, Methods: All residents of a small ALF were surveyed regarding actual and

Pennsylvania, USA hypothetical FS behaviors, self-perceived fire risk, and FS preparedness.

Results: Fifty-eight ALF residents completed the survey. Thirty-three

Correspondence: (58%) individuals reported one or more disabilities. Seven (12%) residents

David Jaslow, MD, M P H ignored the fire alarm and 21 (35%) could not hear it clearly. Sixteen (28%)

Albert Enstein Medical Center residents would attempt to locate the source of a fire rather than-escape from

Department of Emergency Medicine the building. Only 24 (42%) residents were familiar with the building fire

Division of EMS/Disaster Medicine plan. Twenty-three (40%) people surveyed believed that they were not at risk

60 E. Township Line Road of fire in the study facility.

Elkins Park, PA 19027 USA Conclusion: Residents of an ALF may be at increased fire injury risk due to

E-mail: jaslowd@einstein.edu their FS practices and disabilities.

Keywords: assisted living facility; burns; Jaslow D, Ufberg J, Yoon R, McQueen C, Zecher D, Jabukowski G: Fire

elderly; EMS; fire prevention; fire safety; safety knowledge and practices among residents of an assisted living facility.

injury; injury prevention Prehosp Disast Med 2005;20(2):134-138.

Abbreviations:

Introduction

ALF = assisted living facility

Thirty-four million Americans (12.5% of the population) are >65 years of

EMS = emergency medical services

age.1 According to the US Fire Administration, these older adults represent

FS = fire safety

one of the highest fire-risk populations in the United States. Approximately

1,200 deaths and 3,000 injuries each year occur in the elderly due to fire,

Web publication: 10 March 2005

making fire the sixth leading cause of injury-related death among older

adults. The rate of fire deaths increases after 65 years of age, and the rate

is more than tripled among those over 85 years of age compared with

national averages.2

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

approximately 1.5 million Americans live in a group setting such as a nurs-

ing home or assisted living facility (ALF). More than 90% of these people

are >65 years of age, and approximately 35% are >85 years of age. Of adults

over the age of 85 years, nearly 25% of people live in group-living facilities.3

Fires in group-living facilities pose greater-than-normal risks for several

reasons including high resident-to-staff ratios, bedridden residents, and

older construction.2'4-5

The US Fire Administration states that by practicing simple fire safety

tips, older adults can reduce their chances of experiencing a fire and subse-

quent injury or death.6 This study attempts to assess the fire-safety knowl-

edge and practices of a group of elderly adults living in an assisted-living

facility. The survey intends to assess the personalfire-safetypractices of the

inhabitants and their working knowledge of the fire safety plan in place at

their assisted living facility.

Prehospital and Disaster Medicine http://pdm.medicine.wisc.edu Vol. 20, No. 2

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of the Philippines - Manila, on 15 Feb 2020 at 10:04:40, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00002314

Jaslow, Ufberg, Yoon, et al 135

Methods

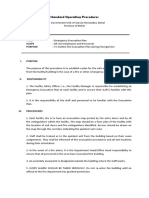

Study Design I. The first thing I would do upon smelling smoke or see-

A 25-question survey concerning knowledge of fire safety ing fire would be to:

a. Call for help

practices and comfort level regarding fire safety was b. Find the source

administered at a local assisted living facility in 2001 c. Run out of the building

(Figure 1). Additional demographic information was col-

lected on each participant including age, gender, education- 2.The first phone call I would make upon smelling smoke

or seeing fire is to:

al background, disabilities, and number of years residing at a. Office/front desk

the study facility. b. 911

c. Neighbor/friend

Population

All 58 residents of the facility were eligible for participation 3. When I hear the fire alarm, I:

a. Ignore it

in the study. Only two participants were unable to complete b. Exit the building

the survey themselves; (1) a 95-year old woman whose niece c. Call the office/front desk

read her the questions and filled in the responses; and (2) a

handicapped 54-year old man who did not complete the 4. The best way to exit a building when there is heavy

survey. The majority of the participants completed the sur- smoke in the hall is to:

a. Walk

vey in a communal setting immediately preceding an annual b. Crawl

lecture on fire safety. They were not informed of the actual c. Run

study until just prior to administration.

5. If I open my door and there is heavy smoke in the hall,

I should:

Setting a. Run out the door

The study was conducted at a small, assisted-living facility b. Leave the door open

in suburban Philadelphia. The facility is composed of a sin- c. Close the door and stay inside

gle, two-story, garden-style apartment building consisting

of individual living units surrounding a central common YES/NO Questions

6. Do you live alone?

area. AH living units have access to the outside either by 7. Is a copy of the fire plan posted in your apartment?

doorway or balcony. 8. Is a map of the fire escape route posted in your

The building is equipped with sprinklers and contains apartment?

both smoke detectors and a fire alarm system. The local fire 9. Did you participate in the last fire drill?

10. Do you live on the second floor?

company has been summoned to the building several times II. Have you ever called 9-1-1 to report an emergency

in recent years for emergency events, which have included here?

fire alarms, broken sprinkler heads, burnt food on a stove 12. Are you a smoker?

causing a smoke condition, and other minor problems. 13. Does anyone who visits you smoke in your

There has been no actual working fire in the facility with- household?

14. Have you ever been forced from any residence due

in the last 15 years. to fire?

This facility was chosen because it is located within the 15. I go to an assigned meeting place when I evaucate

fire protection district of the volunteer fire company in this facility.

which several of the authors are members, including the

Likert Scale questions

primary author who is an assistant chief and the medical 16. I am familiar with the facility's fire plan.

director. Once each year, fire company personnel provide a 17. We have enough fire drills each year.

two-hour educational session about fire safety and review 18. I know the closest exit to my apartment.

the building's fire safety and evacuation plans. This meet- 19. I have practiced the fire escape plan enough and I

ing attracts the majority of residents, which has greatly feel comfortable with its instructions.

20. I can hear the fire alarm clearly when it rings.

simplified the logistical issues surrounding survey adminis- 21. I participate in the facility's firedrills if I am at home.

tration. The few residents that did not attend^ the session 22. Fire is NOT a risk for me at this facility.

were identified by the facility manager and completed sur- 23. I have reviewed this facility's fire plan within the last

veys within one week following initial data collection. year.

24. My disabilities would hinder escape during

evacuation of the building.

Human Subject Committee Review 25. The time for me to evacuate the building from my

The Temple University Institutional Review Board grant- apartment is less than five minutes.

ed this study exemption from review provided that the sur-

Jaslow © 2005 Prehospital and Disaster Medicine

vey was administered anonymously.

Table 1—Survery instrument

Survey Tool and Measurements

The survey instrument used for the study is provided in

Table 1. Participants were given five multiple-choice ques-

tions, ten "yes/no" questions, and ten questions utilizing a

Likert-type scale. General instructions and an explanation

March-April 2005 http://pdm.medicine.wisc.edu Prehospital and Disaster Medicine

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of the Philippines - Manila, on 15 Feb 2020 at 10:04:40, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00002314

136 Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices

of a Likert scale were provided prior to survey administra- devices, and one person used a cane and other unspecified

tion. Additionally, volunteer fire department personnel who means. Five of the respondents who had difficulty with

had been in-serviced in survey administration by the prima- ambulation indicated that they did not need any devices to

ry author were present to assist residents in survey comple- assist them. Three respondents who did not indicate a dif-

tion. Volunteers were instructed not to provide answers or ficulty with ambulation stated that they used a cane to

hints to the answers. Their primary role was to explain the assist with ambulation.

survey questions, point out the existence of the three pages Nine questions were designed to evaluate the actions

of the questionnaire, and collect the completed surveys. respondents would use in case of fire. When asked what

Given the age of the participants, survey items were they would do upon detecting fire conditions, sixteen

designed to minimize confusion. Nine questions examined (28%) people answered that they would attempt to locate

individual fire safety behavior and five of these nine ques- the source rather than call for help or escape from the

tions were modeled after the actual building procedures for building. When asked what actions to take upon hearing

fire in place at the facility at the time of the survey. Ten the fire alarm, seven (12%) people stated they would ignore

questions were designed to evaluate personal beliefs con- it, 15 (26%) people would call the front desk to inquire

cerning fire safety and fire safety practices. Six questions about the circumstances, and 12 (21%) people did not

examined elements known to be associated with death or answer the question at all. Most respondents correctly

injury due tofires,such as living alone, smoking preference, answered to whom the first phone call should be placed

and experiences in a real emergency situation. No question upon detecting possible fire (46, 81%), how to correctly

addressed more than a single action or decision. Although move (crawl) through a smoke-filled hallway, (41, 72%),

study participants left individual questions blank on a spo- and that they would stay inside their apartments if there

radic basis, no specific pattern of incomprehension was heavy smoke in the hallway (50, 88%). However, five

appeared on review of completed surveys. (9%) participants answered that they would run into a

smoke-filled hallway rather than close the door and remain

Results inside. A total of 36 (63%) people indicated that they did

All 58 residents responded to the survey questionnaire, not have a copy of the fire safety plan posted in their apart-

yielding a 100% response rate. Two of the 58 returned sur- ment, forty-nine (86%) answered that they did not have a

veys were incomplete. A note on one incomplete survey map of the fire escape routes posted in their apartment.

indicated that the resident was severely handicapped and Thirty-one (54%) people indicated that they would not go

bedridden, could not read or write, and had minimal verbal to an assigned meeting place upon evacuating the building,

abilities. Given the improbability of this person escaping a although this action is referenced in their fire evacuation

fire on his own or learning fire safety, this survey was plan. At least 28 (49%) residents did not participate in the

excluded from analysis. The second incomplete survey last fire drill.

belonged to a resident who unintentionally left the second Ten questions were designed to measure the participants'

page of the document (containing questions 6-15) blank. personal opinions about their knowledge of fire safety at the

Since this complication did not affect statistical analyses, facility and their comfort level with this knowledge base. A

the remaining answers were included in the data pool. majority of participants felt that they could evacuate the

Thus, 57 surveys were included in the final analysis. building in less than five minutes (47, 82%), that their dis-

Eighteen (32%) of the respondents were male and 40 abilities would not hinder their escape (39, 68%), and that

(68%) were female. The median age of respondents was 78 they knew the exit closest to their apartment (51, 89%).

years with a range of 54-95 years. All but five of the Fewer people agreed that they were familiar with the build-

respondents were >70 years of age. The median length of ing fire plan (24, 42%), and that they had reviewed it with-

time residing full-time at the study facility was three years, in the last year (24,42%). Only 21 (37%) participants agreed

with a range of 0-19 years. Thirteen apartments were occu- that they had practiced the fire escape plan enough to feel

pied by two people. Most of the residents (n = 48, 84%) comfortable with it. Thirty-nine (68%) people surveyed did

had at least some college education and 32 (56%) of these not agree that there were enough fire drills held each year.

listed themselves as college graduates. None of the resi- While 42 (74%) of the participants agreed that they had

dents were smokers, and only one resident reported having participated in fire drills when they were at home, only 37

any household visitors who were smokers. Eight (14%) of (65%) agreed that they could hear the fire alarm clearly

those surveyed reported that they had called the 9-1-1 when it rang. Twenty-three (40%) people surveyed believed

emergency number about some emergency while living in that they were not at risk of fire in the study facility.

the study facility, and six (11%) residents reported that at

some time they had been forced from a residence by fire Discussion

(not necessarily the study facility). By the year 2050, the elderly population of the US is

Thirty-three (58%) people had a disability. Fifteen expected to double and exceed 20% of the population.1 The

(26%) participants had a visual deficit, 17 (30%) had an fastest growing subgroup among the elderly is the group 85

auditory deficit, and 17 (30%) had difficulty with ambula- years of age and older. As people reach 65 years of age, the

tion. Fifteen (26%) persons used devices to assist their risk offire-relateddeath surpasses the national average. At

mobility. Nine of the 15 used only a cane to ambulate, two 75 years of age, the risk is double the national average, and

each used a walker or a scooter, one person used all three the risk is tripled >85 years of age.7

Prchospit-.il and Disaster Medicine http://pdm.medicine.wisc.edu Vol. 20, No. 2

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of the Philippines - Manila, on 15 Feb 2020 at 10:04:40, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00002314

Jaslow, Ufberg, Yoon, et al 137

There are a number of factors that place the elderly at tices. For example, more than one-third of respondents

greater risk for injury or death from fire. Disabilities com- would either ignore a fire alarm or call to inquire about the

monly are cited as a major contributor to the increasing risk circumstances of the alarm, rather than immediately exit-

of fire-related death as age progresses, presumably because ing the building.

they limit the ability of the individual either to recognize or Lack of participation in fire drills and unfamiliarity with

respond quickly to an emergency situation.8 Nearly half of the building fire plan are personal actions that directly may

people >65 years of age and nearly three-quarters of people increase the chances of death or injury in an actual fire

>80 years of age can be classified as having a disability and event. It was not a surprise to find a relative indifference to

more than half of all wheelchair users are >65 years of fire-safety preparedness in this elderly population, since the

age.9'10 same attitudes are prevalent in the general population.16

During the last decade, many elderly persons have cho- However, almost half of the participants did not believe

sen to move from their homes into assisted living facilities that they were at risk of death or injury byfirein their facil-

(ALF).11 There is no universal definition of an ALE ity. Ninety-six percent of those surveyed were aware that

However, it is generally accepted that a range of services their building was equipped with smoke detectors, a fire-

are offered to the resident in order to maximize their inde- alarm system, and a sprinkler system. It is possible that this

pendence while enabling them to complete their activities perceived safety net provides a false sense of security to the

of daily living.12 Unfortunately, the National Fire Incident respondents and dissuades them from appropriate recogni-

Reporting System (NFIRS) does not collect data on the tion of the risk for injury or death due to fire. Finally, the

age of occupants in afire,nor is elderly housing captured as dearth of injury-prevention education provided to this

a specific, fixed-property use or occupancy group. Thus, population may contribute to a certain level of ignorance

there are no national estimates of the incidence of fires in regarding the true risks of injury.

these facilities.13 The results of this study lead to several questions relative

There are additional fire risks incurred by those choos- to the next step in reducingfire-injuryrisk among residents

ing to live in a group-living facility. Fluctuations in staffing of ALE First, can these results be reproduced in different

may leave a high resident-to-staff ratio during the nights.4 populations? One small study of fire-safety knowledge

In emergency situations, bedridden or severely disabled among elderly people who lived at home found similar

residents may be totally dependent on the staff, leaving results and concluded that continued fire-safety education-

those with milder disabilities unattended. The type of con- al programs targeting the elderly were essential.17 Second,

struction used in group-living facilities also contributes to how is education best delivered to this population, and how

the fire risk, since many buildings are designed with large, frequently must it be delivered in light of the forgetfulness

open, meeting places that facilitate the passage of smoke that occurs with age? There are unique challenges in deliv-

and toxic gases through several stories.14 Additionally, ering fire prevention and safety education to the elderly

many older retirement facilities were built with limited population. Such education is delivered routinely to school

exits, combustible finishes, and a lack of automatic sprin- children during Fire Prevention Week, but this education

klers.5 Finally, the inhabitants may have certain fire haz- only has been presented formally since the late 1950s, well

ards such as smoking materials and cooking appliances after the elderly were out of primary or secondary school.18

within their residential area. There are well-designed fire-safety education programs

There is relatively little information in the medical lit- available from both the National Fire Protection

erature regarding the potential impact of senior citizen's Association and the US Fire Administration, but these

individual behavior or actions on their fire injury risk. The materials are not widely available.19'20 Thus, those >65 years

Center for Fire Research recommends assessment of seven of age are unlikely to ever have been serially exposed to these

risk factors when evaluating the risk of injury or death from concepts. There are no studies to support how initial fire-

fire of an older adult. They include the: (1) risk that the safety education should be delivered to the elderly, nor are

individual will resist leaving the structure; (2) individual's there studies looking at retention of this information.

response to fire drills; (3) individual's response to instruc- This latter point provides a golden opportunity for local

tions; (4) individuals mobility impairments; (5) need for fire departments and emergency medical services (EMS) to

extra help; (6) individual's waking response to alarms; and fulfill one of the mission statements of the EMS Agenda

(7) probability that the individual will lose consciousness in for the Future regarding delivery of preventive healthcare

an emergency (i.e., is life support equipment necessary). education to the community.21 Fire services and EMS rou-

The goal of the study was to determine whether some of tinely perform pre-incident surveys in order to respond

these actions may contribute to an increased fire risk. effectively to an emergency at specific buildings, such as

The responses to this survey highlight the danger that schools, factories. Such "pre-plans" include modes of entry

fire poses to inhabitants of assisted-living facilities when ' into the facility, locations of special patient populations,

considering the risk factors listed above. More than one- locations of standpipes, etc.22 Pre-plans usually address the

third of those surveyed could not clearly hear the fire response phase of an emergency, but they may not ade-

alarm. The responses also indicate that technology alone quately address the preparedness phase of emergency

may not be sufficient in preventing fire injuries or death, response. Such planning could include an analysis of at-

since the actions of those whom the technology is designed risk populations in the coverage area and a plan for annual

to alert may not follow commonly accepted fire safety prac- injury prevention education they should receive.

March-April 2005 http://pdm.medicine.wisc.edu Prehospital and Disaster Medicine

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of the Philippines - Manila, on 15 Feb 2020 at 10:04:40, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00002314

138 Fire Safety Knowledge and Practices

This study has several limitations. The study population Conclusion

suffers from selection bias since it does not reflect the typ- Elderly residents of the assisted living facility surveyed may

ical make-up of a senior citizen group. It was comprised of be at increased risk for injury and death due to fire based

a very educated core of non-smokers who are likely to be in on poor fire safety knowledge and practices. Educational

relatively good health for their age based on self-described curricula focused on basic concepts of fire safety, including

disabilities. The study group also is a very homogenous recognition and escape from a fire emergency, should be

one. All study participants were Caucasian and most were implemented in these facilities in conjunction with

raised in the tiny, affluent, and tightly knit community in improvements in technology to further enhance the

which they currently reside. Although the study sample chances of survival in a structural fire. Whether such a cur-

comprised the entire population of interest, it also repre- riculum can be mastered or remembered by residents and if

sents a very small segment of the senior citizen population this impacts the fire death and injury rates remains to be

in the region. Thus, the ability to generalize the conclu- seen.

sions to a larger segment of society is limited.

References

1. US Bureau of the Census: U.S. population projections of the United States 11. Hall JR: The elderly, the sick, and health care facilities. Fire J 1990;84:

by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin: 1995-2050. Current Population Reports, 32(5);37-42.

February 1996. 12. AARP Money and Work website. Available at www.aarp.org/confacts/

2. United States Fire Administration: Fire Risks for Older Adults. Federal money/assistliv.html. Accessed 11 January 2005.

Emergency Management Agency, October 1999. 13. Special Data Information Package: Housing for Older adults, NFPA, One-

3. Strahan G: An overview of nursing homes and their current residents: Data Stop data Shop, Fire Analysis and Research Division, 1 Batterymarch Park,

from the 1995 national nursing home survey. Centers for Disease Control and PO Box 9101, Quincy, MA, July 1999.

Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 23 January 1997.. 14. Blye P, Yess JP: Fire safety in elderly housing. NFPA Journal 1987;Nov/Dec.

4. Cherry RL: Agents of nursing home quality of care: Ombudsman and staff 15. Kuns J: Public education. Proceedings of the 1980 conference on life safety and

ratios revisited. Gerontologist 1991;31:3O2-308. the handicapped. National Bureau of Standards, NBS-GCR Series

5. Petraglia JS: Fire and the aging of America. NFPA Journal 1991;85:36-38, (Washington DC: GPO), 1981.

41-46. 16. Silverstein P, Lack B: Fire prevention in the United States. Are the home

6. NFPA Center for High-Risk Outreach: Remembering When: A Fire and Fall fires still burning? Surg C/in North Am 1987;67:1-14.

Prevention Program for Older Adults. National Fire Protection Association: 17. Stiles NJ, Bratcher D, Ramsbottom-Lucier M, Hunter G: Evaluating fire

Quincy, Massachusetts, 1987. safety in older persons through home visits. J KY Med Assoc 2001;99:

7. National Fire Data Center, United States Fire Administration: Fire in the 105-110.

United States (FITUS) 1986-1995. Federal Emergency Management 18. NFPA: Education website. Available at www.nfpa.org/Education/FPW/

Agency, August, 1998. History_of_FPW/history_of_fpw.asp. Accessed 11 January 2005.

8. Gulaid J, Sacks J, Sattin R: Death from residential fires among older people. 19. NFPA: Education website. Available at www.nfpa.org/Education/

JAm GeriatrSoc 1989; 37:331-334. RememberingWhen/RememberingWhen.asp. Accesssed 11 January 2005.

9. United States Bureau of the Census: Population Profile of the United States. 20. US Fire Administration: At Risk: Older Americans. Available at www.usfa.

1997. fema.gov/Safety/older.htm. Accessed 11 January 2005.

10. Vital and Health Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, Center for 21. NHTSA: EMS Agenda For The Future. Washington, DC, NHTSA, 1996.

Disease Control and Prevention, Current Estimates From the National Health 22. Hall R, Adams B (eds): Essentials of Fire Fighting. Fire Protection

Interview Survey, Series 10, No. 192,1994. Publications, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma, 1998.

Prehospital and Disaster Medicine http://pdm.medicine.wisc.edu Vol. 20, No. 2

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of the Philippines - Manila, on 15 Feb 2020 at 10:04:40, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00002314

You might also like

- Onan DKD Service Manual PDFDocument71 pagesOnan DKD Service Manual PDFStalin Paul Rodriguez Leon100% (3)

- Confined Space Entry Procedure WorksheetDocument5 pagesConfined Space Entry Procedure WorksheetToma AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Are Nurses Ready - Disaster Preparedness in - 2008 - Australasian Emergency Nur PDFDocument10 pagesAre Nurses Ready - Disaster Preparedness in - 2008 - Australasian Emergency Nur PDFHikmat PramajatiNo ratings yet

- Advanced Space Hulk v1.0Document92 pagesAdvanced Space Hulk v1.0adlard_matthew100% (2)

- 1 s2.0 0022437596869787 MainDocument2 pages1 s2.0 0022437596869787 MainLanlan WeiNo ratings yet

- Quan L. Do Parents Value Drowning Prevention Information at Discharge From The Emergency DepartmentDocument4 pagesQuan L. Do Parents Value Drowning Prevention Information at Discharge From The Emergency DepartmentVictoriaMuroNo ratings yet

- Icnirp SCI Review: Review of The Epidemiologic Literature On Emf and HealthDocument24 pagesIcnirp SCI Review: Review of The Epidemiologic Literature On Emf and HealthAshu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Disaster Preparedness Among Older Japanese Adults With Longterm Care Needs and Their Family CaregiversDocument8 pagesDisaster Preparedness Among Older Japanese Adults With Longterm Care Needs and Their Family Caregiversistianna nurhidayatiNo ratings yet

- Caring Lansia Dalam BencanaDocument5 pagesCaring Lansia Dalam Bencanaistianna nurhidayatiNo ratings yet

- Burn Prevention and First Aid KnowledgeDocument6 pagesBurn Prevention and First Aid KnowledgeBudi SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Student: AwarenessDocument4 pagesStudent: Awarenessoendila debnathNo ratings yet

- Phelan 2018Document16 pagesPhelan 2018Santiago MayorNo ratings yet

- Nov 23 Trauma Geriátrico Hruska 2018Document17 pagesNov 23 Trauma Geriátrico Hruska 2018lfc2086No ratings yet

- Siddharama M Bolakotagi: E-ISSN: 2664-1666 P-ISSN: 2664-1658Document5 pagesSiddharama M Bolakotagi: E-ISSN: 2664-1666 P-ISSN: 2664-1658Mamata BeheraNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 13185Document13 pagesIjerph 19 13185hello mircadoNo ratings yet

- Patient Analytical Report On BurnsDocument57 pagesPatient Analytical Report On Burnsisnaira imamNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Trauma Life Support 3e Update 2017 FINALDocument21 pagesPediatric Trauma Life Support 3e Update 2017 FINALAnita MacdanielNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument13 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptGeorge UngureanuNo ratings yet

- Clarke S. Et Al (2017) Conscientious Objection To VaccinationDocument7 pagesClarke S. Et Al (2017) Conscientious Objection To VaccinationSANDHYANo ratings yet

- 6.children in DisasterDocument76 pages6.children in DisasterIsmail SlimNo ratings yet

- How Lightning Kills and Injures: Corresponding Author Address: Mary Ann CooperDocument3 pagesHow Lightning Kills and Injures: Corresponding Author Address: Mary Ann Cooperjuan832No ratings yet

- First Page PDFDocument1 pageFirst Page PDFRatna HidayatiNo ratings yet

- Uncorrected Manuscript: Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older PeopleDocument9 pagesUncorrected Manuscript: Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older PeopleKiky HaryantariNo ratings yet

- Infant Deaths - Is There An Association With Vaccines - by Julian Gillespie, LLB, BJurisDocument11 pagesInfant Deaths - Is There An Association With Vaccines - by Julian Gillespie, LLB, BJurisSY LodhiNo ratings yet

- Adult ImmunizationsDocument12 pagesAdult ImmunizationsredroseeeeeeNo ratings yet

- Melanoma - PregradoDocument8 pagesMelanoma - PregradoDaniela DuránNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Outcomes of Burn Injuries at A Tertiary Burn Care Center in BangladeshDocument7 pagesEpidemiology and Outcomes of Burn Injuries at A Tertiary Burn Care Center in BangladeshE.sundara BharathiNo ratings yet

- Communicating The Benefits and Risks of VaccinesDocument8 pagesCommunicating The Benefits and Risks of VaccinesBrandeice BarrettNo ratings yet

- 6 Promoting SafetyDocument30 pages6 Promoting SafetyFaisal QureshiNo ratings yet

- Older Adults' Attitudes To Death, Palliative Treatment and Hospice CareDocument9 pagesOlder Adults' Attitudes To Death, Palliative Treatment and Hospice CarefiennesrnNo ratings yet

- Initial Management of Seizure in Adults: Clinical PracticeDocument13 pagesInitial Management of Seizure in Adults: Clinical PracticeMatthew MhlongoNo ratings yet

- Logistical and Structural Challenges Are The Major Obstacles For Family Medicine Physicians' Ability To Administer Adult VaccinesDocument7 pagesLogistical and Structural Challenges Are The Major Obstacles For Family Medicine Physicians' Ability To Administer Adult Vaccinescarla laureanoNo ratings yet

- Preventive Measures For Fire-Related Injuries and Their Risk Factors in Residential Buildings: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesPreventive Measures For Fire-Related Injuries and Their Risk Factors in Residential Buildings: A Systematic ReviewTR NahidNo ratings yet

- PEDIATRIC BURN Clin NorthDocument8 pagesPEDIATRIC BURN Clin NorthRaul PerezNo ratings yet

- doença de alzheimerDocument17 pagesdoença de alzheimerBeatriz PaivaNo ratings yet

- Prevenção QuedasDocument10 pagesPrevenção Quedasgabrielapetitot_9179No ratings yet

- Radiation and ChildrenDocument2 pagesRadiation and ChildrenNikki No-NukesNo ratings yet

- Sample Case StudyDocument23 pagesSample Case StudyDELFIN, Kristalyn JaneNo ratings yet

- A Review of Electrical Burns Admitted in A Philippine Tertiary Hospital Burn CenterDocument5 pagesA Review of Electrical Burns Admitted in A Philippine Tertiary Hospital Burn CenterRiza Paula LabagnoyNo ratings yet

- Natural History of Burnout Stress and Fatigue in A Pediatric Resident CohortDocument10 pagesNatural History of Burnout Stress and Fatigue in A Pediatric Resident CohortIkunda IsmaelNo ratings yet

- Science of Risk AssessmentDocument4 pagesScience of Risk AssessmentDrBishnu Prasad MahalaNo ratings yet

- Keinginan 1 PDFDocument11 pagesKeinginan 1 PDFMerySeprianiNo ratings yet

- Daniels Et Al (2015) 508Document9 pagesDaniels Et Al (2015) 508Forum PompieriiNo ratings yet

- Baldwin 2016Document10 pagesBaldwin 2016Nahda Fini SNo ratings yet

- HSJ Vol.9no.2 2020-31-37Document7 pagesHSJ Vol.9no.2 2020-31-37ROSALINDA BULANo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 (K)Document17 pagesPractical Research 1 (K)Joshua ValledorNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Childhood Leukemia: A Comprehensive Literature ReviewDocument37 pagesRisk Factors For Childhood Leukemia: A Comprehensive Literature Reviewmisbahhari_mdNo ratings yet

- Afaa 274Document5 pagesAfaa 274arman ahdokhshNo ratings yet

- Injury Risks of EMS Responders: Evidence From The National Fire Fighter Near-Miss Reporting SystemDocument9 pagesInjury Risks of EMS Responders: Evidence From The National Fire Fighter Near-Miss Reporting SystemAna OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Care in Disasters 2013Document6 pagesPediatric Care in Disasters 2013Cris TobalNo ratings yet

- Early-Onset Basal Cell CarcinomaDocument11 pagesEarly-Onset Basal Cell CarcinomajxmackNo ratings yet

- Level of Awareness of Criminology Students On CBRN Issues F2 PDFDocument33 pagesLevel of Awareness of Criminology Students On CBRN Issues F2 PDFRODOLFO RUBISNo ratings yet

- Disaster Nursing SAS Session 20Document5 pagesDisaster Nursing SAS Session 20Niceniadas CaraballeNo ratings yet

- Niehs PDFDocument2 pagesNiehs PDFagusNo ratings yet

- Fpubh 01 00040 PDFDocument2 pagesFpubh 01 00040 PDFMeidy RamschieNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Ring Injury in The Elderly Fragile Patients With Substancial Mortality Rates and Long Term Physical Impairment. 2019Document12 pagesPelvic Ring Injury in The Elderly Fragile Patients With Substancial Mortality Rates and Long Term Physical Impairment. 2019Gonzalo JimenezNo ratings yet

- Radiation Safety Paper - Kristen DezellDocument4 pagesRadiation Safety Paper - Kristen Dezellapi-568316609No ratings yet

- Public Perception 1Document8 pagesPublic Perception 1Calvin SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Burn Contracture Outcome in Developing CountriesDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting Burn Contracture Outcome in Developing CountriesWahyu IndraNo ratings yet

- Lived Experiences of Regular Volunteer Emergency First Responders A Phenomenological ResearchDocument12 pagesLived Experiences of Regular Volunteer Emergency First Responders A Phenomenological ResearchInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument25 pagesAcute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaJavierNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older People: Roy L. Soiza, Chiara Scicluna, Emma C. ThomsonDocument5 pagesEfficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older People: Roy L. Soiza, Chiara Scicluna, Emma C. ThomsonMauricioNo ratings yet

- WSES Handbook of Mass Casualties Incidents ManagementFrom EverandWSES Handbook of Mass Casualties Incidents ManagementYoram KlugerNo ratings yet

- Integrals QUIZDocument3 pagesIntegrals QUIZNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Royal Society For The Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Journal of The Royal Society of ArtsDocument8 pagesRoyal Society For The Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Journal of The Royal Society of ArtsNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Contribution To The Investment Evaluation in Terms of The Forest Fires Prevention Using The Cost-Benefit Analysis MethodDocument13 pagesContribution To The Investment Evaluation in Terms of The Forest Fires Prevention Using The Cost-Benefit Analysis MethodNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Hazardous Material Accidents With Mass Casualties Prevention Strategies by Hamburg Fire BrigadeDocument2 pagesHazardous Material Accidents With Mass Casualties Prevention Strategies by Hamburg Fire BrigadeNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- MonologueDocument1 pageMonologueNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Receiving The Unshakeable Kingdom of GodDocument3 pagesReceiving The Unshakeable Kingdom of GodNorma Alejandra AbrenaNo ratings yet

- Year 9 English Examination 2014Document19 pagesYear 9 English Examination 2014api-246403506No ratings yet

- Pokemon Red Rescue Faq by HswbazDocument44 pagesPokemon Red Rescue Faq by HswbazHafiz Maulana AhmadNo ratings yet

- 英语作文高级替换词Document14 pages英语作文高级替换词sqhaaNo ratings yet

- Mark BFPDocument3 pagesMark BFPmarz sidNo ratings yet

- Fire Sprinkler - ABCB Reference Document - Automatice Fire Sprinkler SystemDocument193 pagesFire Sprinkler - ABCB Reference Document - Automatice Fire Sprinkler SystemJeffrey WalkerNo ratings yet

- FMDS0102Document69 pagesFMDS0102hhNo ratings yet

- 7-88 Flammable Liquid Storage TanksDocument44 pages7-88 Flammable Liquid Storage TanksAchraf BoudayaNo ratings yet

- Maintenance (22.09.2022)Document2 pagesMaintenance (22.09.2022)Imelisya JaulinNo ratings yet

- Fire PPT CompilationDocument9 pagesFire PPT CompilationDonna Mae MartinezNo ratings yet

- Qatar Civil Defence ExaminationDocument10 pagesQatar Civil Defence Examinationali.abk2017No ratings yet

- Foaming AgentsDocument6 pagesFoaming AgentsrmaffireschoolNo ratings yet

- Emergency Evacuation PlanDocument14 pagesEmergency Evacuation PlanGlenn MadeloNo ratings yet

- Emergency Evacuation Plans and ExercisesDocument12 pagesEmergency Evacuation Plans and ExercisesSamier MohamedNo ratings yet

- The Flixborough, UK, Cyclohexane Disaster, 1 June 74Document24 pagesThe Flixborough, UK, Cyclohexane Disaster, 1 June 74rodofgodNo ratings yet

- Aosh Assessment QuestionDocument7 pagesAosh Assessment QuestionMd Imran HossainNo ratings yet

- Subject: Invitation To Join As "Resource Speaker" On Our Seminar On Fire Prevention and Safety ConsciousnessDocument6 pagesSubject: Invitation To Join As "Resource Speaker" On Our Seminar On Fire Prevention and Safety ConsciousnessRjay CadaNo ratings yet

- FIRE PREVENTION NSTPDocument7 pagesFIRE PREVENTION NSTPmariel rose bandeNo ratings yet

- Aux Boiler Fire Case StudyDocument3 pagesAux Boiler Fire Case StudyasNo ratings yet

- Buku Saku Proteksi Kebakaran 2022Document25 pagesBuku Saku Proteksi Kebakaran 2022rajaNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Emergency PlanDocument35 pagesLaboratory Emergency PlanMß WæžəəřNo ratings yet

- Fire DrillsDocument10 pagesFire Drillseliasox123100% (2)

- FO1 Journal 10000Document43 pagesFO1 Journal 10000Alta Tierra FssNo ratings yet

- Hazard AssessmentDocument2 pagesHazard AssessmentRahul ShajiNo ratings yet

- Protego PDFDocument18 pagesProtego PDFNemezis1987No ratings yet

- U42 Schlumberger MsdsDocument7 pagesU42 Schlumberger Msdsjangri1098No ratings yet

- Makati City Fire Station: Fire and Life Safety SeminarDocument60 pagesMakati City Fire Station: Fire and Life Safety SeminarAireen TanioNo ratings yet

- Unit 19Document14 pagesUnit 19Ashwani tyagiNo ratings yet