Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

68 viewsGSM Report

GSM Report

Uploaded by

Zaffar KhanCorporate strategy involves selecting the industries a firm competes in, whereas business strategy is about how a firm competes within an industry. There are two dimensions of corporate strategy - diversification into new industries/markets, and vertical integration into suppliers' or buyers' industries. Superior firm performance results from effectively sharing resources, transferring competencies, and creating specific assets across industries, not just from how diversified or integrated the firm is. The three "building blocks" of corporate strategy that motivate diversification and integration are sharing existing resources in new markets, applying competencies developed in one industry to another, and creating customized assets that are more valuable to the firm than to others.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)From EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (25)

- Thomas Dorsey-Point and Figure Charting-EnDocument403 pagesThomas Dorsey-Point and Figure Charting-EnLily Wang100% (4)

- Types of MergersDocument13 pagesTypes of MergersJebin JamesNo ratings yet

- 73ac4horizontal & Vertical IntegrationDocument5 pages73ac4horizontal & Vertical IntegrationOjasvee KhannaNo ratings yet

- Consulting Interview Case Preparation: Frameworks and Practice CasesFrom EverandConsulting Interview Case Preparation: Frameworks and Practice CasesNo ratings yet

- Writing A Credible Investment Thesis - HBS Working KnowledgeDocument6 pagesWriting A Credible Investment Thesis - HBS Working KnowledgejgravisNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions Notes MBADocument24 pagesMergers and Acquisitions Notes MBAMandip Luitel100% (1)

- Horizontal and Vertical IntegrationDocument9 pagesHorizontal and Vertical IntegrationAmna Rasheed100% (1)

- Name: Zaffar-Ul-Lah Khan Class: Bba Vi Sec: (Ii) GR#: 252066Document7 pagesName: Zaffar-Ul-Lah Khan Class: Bba Vi Sec: (Ii) GR#: 252066Adeel Shafique KhawajaNo ratings yet

- Corporate StrategyDocument5 pagesCorporate StrategyMihir HariaNo ratings yet

- Corporate StrategyDocument9 pagesCorporate StrategyPallavi RanjanNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Concepts For ProfessionalsDocument6 pagesStrategic Management Concepts For Professionalsoumar06No ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisition Mba Final NotesDocument60 pagesMergers and Acquisition Mba Final NotestarunNo ratings yet

- Types of M&ADocument31 pagesTypes of M&Adhruv vashisth100% (1)

- CHAPTER 8 For Students (S.M.)Document6 pagesCHAPTER 8 For Students (S.M.)jeongyeonbin02No ratings yet

- TYPES OF MERGER and ACQUISITION (Based On Relatedness of Business)Document5 pagesTYPES OF MERGER and ACQUISITION (Based On Relatedness of Business)Urooba ZainNo ratings yet

- Lecture Topic 1Document30 pagesLecture Topic 1Sunaina BenNo ratings yet

- Mergers and DiversificationDocument6 pagesMergers and DiversificationJenny Rose Castro FernandezNo ratings yet

- Corporate Alliances and Acquisitions: Strategic Alliances Enable Companies To ShareDocument22 pagesCorporate Alliances and Acquisitions: Strategic Alliances Enable Companies To SharezachNo ratings yet

- Motives For Merger & AcquisitionDocument6 pagesMotives For Merger & AcquisitionFaisal KhanNo ratings yet

- FM Unit 5Document26 pagesFM Unit 5KarishmaNo ratings yet

- Introductio1 AmitDocument11 pagesIntroductio1 AmitKaranPatilNo ratings yet

- Are U Owner of Best AssetsDocument7 pagesAre U Owner of Best AssetsamitkulNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts: M & A DefinedDocument23 pagesBasic Concepts: M & A DefinedChe DivineNo ratings yet

- Activity # 3: Corporate Strategies: Questions 5.1Document5 pagesActivity # 3: Corporate Strategies: Questions 5.1Jonela LazaroNo ratings yet

- Channel MARKETING-finalDocument7 pagesChannel MARKETING-finalAhmadNo ratings yet

- Nature of Corporate RestructuringDocument5 pagesNature of Corporate RestructuringNadeem KhanNo ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument4 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsAnu SubediNo ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument33 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsRomNo ratings yet

- Horizontal Merger: Reason For MergersDocument5 pagesHorizontal Merger: Reason For MergershiteshNo ratings yet

- Micheal Anyika A.: What Is Supply Chain Design?Document19 pagesMicheal Anyika A.: What Is Supply Chain Design?spartNo ratings yet

- Porter's ForcesDocument5 pagesPorter's ForcesJoshua RamosNo ratings yet

- Backward IntegrationDocument10 pagesBackward IntegrationKrishelle Kate PannigNo ratings yet

- Synp 02 Growth Through Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument14 pagesSynp 02 Growth Through Mergers and AcquisitionsSamman GuptaNo ratings yet

- CH9-Diversification and AcquisitionsDocument9 pagesCH9-Diversification and AcquisitionsVincent LeruthNo ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument85 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsAnubhav AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Mergers and AcquisitionDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Mergers and AcquisitionkairavizanvarNo ratings yet

- Merger and AcquisitionsDocument16 pagesMerger and Acquisitionsanuja kharelNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4Document4 pagesTutorial 4Aminath AzneeNo ratings yet

- Organizational ArchitectureDocument3 pagesOrganizational ArchitectureFranciskaNo ratings yet

- Section C - 660 - SMDocument4 pagesSection C - 660 - SMDrPalanivel LpprvNo ratings yet

- CH 6Document6 pagesCH 6rachelohmygodNo ratings yet

- E-Commerce BCA S309FirstUnitRemainNotesDocument18 pagesE-Commerce BCA S309FirstUnitRemainNotesAshish SachanNo ratings yet

- Launching A Successful Business-to-Business Consortium: Opportunities For Action in Industrial GoodsDocument10 pagesLaunching A Successful Business-to-Business Consortium: Opportunities For Action in Industrial Goodstaona madanhireNo ratings yet

- MBA - N.DINESH - VUCA - Unit 3 - EnotesDocument21 pagesMBA - N.DINESH - VUCA - Unit 3 - EnotesRajeshNo ratings yet

- Strategic ManagementDocument14 pagesStrategic ManagementMAXWELL gwatiringaNo ratings yet

- Supply RiskDocument6 pagesSupply RiskFARAI KABANo ratings yet

- Porters 5 Mckinseys 7sDocument15 pagesPorters 5 Mckinseys 7sVernie O. HandumonNo ratings yet

- Project Paper 3PLDocument7 pagesProject Paper 3PLDinesh RamaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 International BusinessDocument12 pagesChapter 13 International BusinessnihalNo ratings yet

- Critical Success FactorsDocument4 pagesCritical Success FactorsAnonymous RVOJZzzhNo ratings yet

- SFMDocument10 pagesSFMSoorajKrishnanNo ratings yet

- Mission & Vision of The Firm Know Yourself: SWOT Analysis Scan External EnvironmentDocument14 pagesMission & Vision of The Firm Know Yourself: SWOT Analysis Scan External EnvironmentavijeetboparaiNo ratings yet

- Mergers & AcquisitionsDocument22 pagesMergers & AcquisitionsLAKHAN TRIVEDINo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 ReportDocument29 pagesChapter 10 ReportMay Jude Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- What's The Difference Between A Merger and An Acquisition? AnswerDocument4 pagesWhat's The Difference Between A Merger and An Acquisition? Answerjaiswalroshni05No ratings yet

- CH 05Document14 pagesCH 05leisurelarry999No ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument12 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsSaurav NishantNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management 2Document10 pagesMarketing Management 2Pankaj YadavanNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisition ProjectDocument21 pagesMergers and Acquisition ProjectNivedita Kotian100% (1)

- 2019491243256731WHTRateCardupdated09 03 19FinSupSecAmendAct2019Document5 pages2019491243256731WHTRateCardupdated09 03 19FinSupSecAmendAct2019Shoaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- Q2 FY22 Financial TablesDocument13 pagesQ2 FY22 Financial TablesDennis AngNo ratings yet

- ch01 The Role of Financial ManagementDocument25 pagesch01 The Role of Financial ManagementBagusranu Wahyudi PutraNo ratings yet

- Outreach NetworksDocument3 pagesOutreach NetworksPaco Colín50% (2)

- Global Trust BankDocument19 pagesGlobal Trust BankLawi Anupam33% (6)

- CDSL Kra PDFDocument5 pagesCDSL Kra PDFRamesh SathyamoorthiNo ratings yet

- Exit Offer Letter and Delisting Circular PDFDocument172 pagesExit Offer Letter and Delisting Circular PDFInvest StockNo ratings yet

- Earnings Per Share (Loi Nhuan Tren CP)Document34 pagesEarnings Per Share (Loi Nhuan Tren CP)Chi HoàngNo ratings yet

- Applied Corporate Finance: Journal ofDocument15 pagesApplied Corporate Finance: Journal ofTrâm Anh ĐoànNo ratings yet

- GenMath Q2 Mod13Document20 pagesGenMath Q2 Mod13roxtonandrada8No ratings yet

- Bailment and PledgeDocument14 pagesBailment and PledgeBijitashaw GøgøiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument5 pagesNew Microsoft Word Documentrajmv7No ratings yet

- International Banking EvolutionDocument8 pagesInternational Banking EvolutionKathleen Faith C. BrionesNo ratings yet

- Form ITR-6Document35 pagesForm ITR-6Accounting & TaxationNo ratings yet

- Unvielded - Final2Document102 pagesUnvielded - Final2massimoNo ratings yet

- Pro Forma Financial StatementsDocument3 pagesPro Forma Financial StatementsWaiLonn100% (1)

- Rescue3 AsdDocument7 pagesRescue3 AsdHay JirenyaaNo ratings yet

- Activity No. 1. Accounting PracticesDocument3 pagesActivity No. 1. Accounting PracticesNalin SNo ratings yet

- 1.5 Common Probability DistributionDocument48 pages1.5 Common Probability DistributionMarioNo ratings yet

- Utkashtripathi 11909588 Finca 2Document12 pagesUtkashtripathi 11909588 Finca 2vinay100% (1)

- Hexaware DelistingDocument48 pagesHexaware DelistingNihal YnNo ratings yet

- Comparison of AlternativesDocument26 pagesComparison of AlternativesMarielle CambaNo ratings yet

- Investment Property and Other InvestmentsDocument4 pagesInvestment Property and Other InvestmentsMiguel MartinezNo ratings yet

- Eliot Waves E Book Part1 PDFDocument13 pagesEliot Waves E Book Part1 PDFByron Arroba0% (1)

- DAX Performance Between 1959 and 2016: Foundation OperatorDocument6 pagesDAX Performance Between 1959 and 2016: Foundation OperatorJesu JesuNo ratings yet

- AssignmentsDocument2 pagesAssignmentsGauravGupta100% (1)

- Bond Analysis and ValuationDocument76 pagesBond Analysis and ValuationMoguche CollinsNo ratings yet

- Impact of Festival Affecting Stock Market Indices in BRICS RewrittenDocument9 pagesImpact of Festival Affecting Stock Market Indices in BRICS RewrittensushmasreedaranNo ratings yet

- Nest TraderDocument74 pagesNest Traderpercysearch100% (1)

GSM Report

GSM Report

Uploaded by

Zaffar Khan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

68 views5 pagesCorporate strategy involves selecting the industries a firm competes in, whereas business strategy is about how a firm competes within an industry. There are two dimensions of corporate strategy - diversification into new industries/markets, and vertical integration into suppliers' or buyers' industries. Superior firm performance results from effectively sharing resources, transferring competencies, and creating specific assets across industries, not just from how diversified or integrated the firm is. The three "building blocks" of corporate strategy that motivate diversification and integration are sharing existing resources in new markets, applying competencies developed in one industry to another, and creating customized assets that are more valuable to the firm than to others.

Original Description:

Original Title

gsm report

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCorporate strategy involves selecting the industries a firm competes in, whereas business strategy is about how a firm competes within an industry. There are two dimensions of corporate strategy - diversification into new industries/markets, and vertical integration into suppliers' or buyers' industries. Superior firm performance results from effectively sharing resources, transferring competencies, and creating specific assets across industries, not just from how diversified or integrated the firm is. The three "building blocks" of corporate strategy that motivate diversification and integration are sharing existing resources in new markets, applying competencies developed in one industry to another, and creating customized assets that are more valuable to the firm than to others.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as doc, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

68 views5 pagesGSM Report

GSM Report

Uploaded by

Zaffar KhanCorporate strategy involves selecting the industries a firm competes in, whereas business strategy is about how a firm competes within an industry. There are two dimensions of corporate strategy - diversification into new industries/markets, and vertical integration into suppliers' or buyers' industries. Superior firm performance results from effectively sharing resources, transferring competencies, and creating specific assets across industries, not just from how diversified or integrated the firm is. The three "building blocks" of corporate strategy that motivate diversification and integration are sharing existing resources in new markets, applying competencies developed in one industry to another, and creating customized assets that are more valuable to the firm than to others.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as doc, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 5

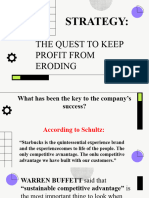

Corporate Strategy

Corporate strategy is the selection and development of the markets (or

industries) in which a firm competes. Therefore, corporate strategy

deals with what industries (or markets) a firm seeks to compete in.

Business level strategies (low cost, diversification, and focus) that were

discussed last chapter are HOW a firm competes in a single market or

industry. Therefore, corporate strategy and business strategy describe

very different issues.

Unlike business level strategy, work on corporate

strategy frameworks is not nearly as advanced or well done. Most

emphasis is on describing corporate strategy. Describing corporate

strategy involves two primary dimensions, vertical integration, where

firms engage in activities that were formerly done by their buyers or

suppliers and diversification where they enter additional markets.

While that often gets a lot of attention, “How diversified is the firm?” is

not really that important for understanding why firm performance

differs. What really allows corporate strategy to result in superior firm

performance are what I’ll call the “building blocks of corporate

strategy” - sharing resources, transferring competencies, and creating

specific assets. However, before moving into them, best to go ahead

and lay out how corporate strategy is described.

Describing Corporate Strategy

There are two basic descriptive dimensions of corporate strategy, how

diversified and how vertically integrated an organization is. It may be

helpful to think of both of these dimensions as a continuum.

Diversification occurs when a firm enters a new industry or market.

Just like when we discussed Porter's Five Forces, the definition of an

industry or market is critically important. There are formal

classification codes, the North American Industrial Classification

System (previously Standard Industrial Classification codes – see box in

external analysis), for trying to classify all industries in an economy.

However, for our purposes the NAICS is not very useful. However, it is

critical when doing your analysis to carefully define industries in

describing firm diversification. For example, was Coca-Cola's move

from carbonated beverages into bottled water an instance of

diversification? Depending on how you define the industry, it could be

yes or no.

How diversified a firm is can be determined by

what portion of its sales are derived from different markets. The larger

a percentage of sales are derived from different markets/industries the

more diversified the firm can be said to be. A wide range of labels can

be applied to the level of a firm's diversification from single business

(95% of sales from one industry), dominant business (70% from one

industry) to diversified (less than 70% from any one industry). While

single business firms are usually found in fast moving, rapidly evolving

industries where there is a need to focus, there are exceptions. William

Wrigley, the chewing gum manufacturer, is perhaps the most famous

single business firm. However, most large firms engage in some

diversification.

Related vs. Unrelated.

Diversification can be either related or unrelated. The key issue here is

if the operations of the firm in the new industry share some link in with

the firm's existing value chain. Is there some value adding activity that

can be shared? For example, is there a production facility, a

distribution network, or a marketing competence that both can use?

Historically it was thought that related diversification would be better

than unrelated diversification. However, the

Coordination costs of related diversification appear to consume a lot of

the expected benefits. Therefore, while most firms seem to engage in

related diversification its benefits are only slightly, if at all, better than

unrelated.

Vertical integration occurs when a firm takes on activities that were

formally done by others on its behalf. In a way, vertical integration is

just a special case of diversification, a firm is diversifying into either its

suppliers' or its buyers' industries. For example if a company starts to

make components for its products on its own or if it starts to distribute

products directly to customers it is engaged in vertical integration.

Ford Motor Company under Henry Ford was extremely vertically

integrated going so far at one time as to own the iron ore mines that

fueled its steel mills that fed its automobile assembly operations.

However, recently vertical integration has fallen out of favor in

preference to contract manufacturing and outsourcing. It will be

interesting to see how the expansion of the internet creates

opportunities for firms to vertically integrate downstream into direct

distribution.

A firm's level of vertical integration can be modeled

using an industry (rather than a firm) value chain. An industry value

chain models all the significant value adding steps that occur in an

industry from the most basic raw materials to the final consumers. The

more of these activities a firm encompasses the more vertically

integrated it is. A firm that enters activities to its left on the industry

value chain, replacing a supplier, is said to be vertically integrating

"upstream". A firm entering activities to its right, supplanting a buyer,

is said to be moving "downstream". So continuing the historical Ford

example, Ford buying coal mines would be upstream while him buying

a dealership would be downstream vertical integration. Vertical

integration entails coordination (bureaucratic) costs just like related

diversification. For example, a major issue for vertically integrated

firms is transfer prices, what should one part of the firm charge

another? Furthermore, a vertically integrated firm faces greater

technological risk and demand uncertainty. In many ways vertical

integration is a lot like financial leverage, when times are good, they

are very good as the firm profits all along the value chain, but when

they go bad, it's correspondingly bad all along the value chain.

However, both sets of these terms are wholly arbitrary

and simply descriptive. If a firm is single business versus dominant

business matters little to answering our question of why firm

performance differs. Some value chain function can almost always be

claimed as being shared to meet the definition of "relatedness".

Likewise, vertical integration, upstream or downstream, which is

better? Therefore, while it is important to be aware of these descriptive

terms, the key issue is how well an organization is able to share

resources, transfer competencies and create specific assets regardless

of the description of its corporate strategy.

The Benefits of Corporate Strategy: The Building Blocks of

Corporate Advantage

All (well 90%+) corporate strategy is motivated by what we'll term the

three building blocks of corporate strategy: shared resources,

transferred competencies, and the creation of specific assets. While

there are many possible reasons given for things like diversification,

they can almost all be traced back to one of these three motivations.

Sharing resources is taking something an organization already has

and using it in a new industry. For example, Wal-Mart plunking down

one-hour photo labs in its stores is an example of sharing a resource.

WMT already has stores (a resource) located all over the country.

Adding this service is simply a matter of sharing its existing resource.

Economies of scope, efficiencies gained due to the breath of one's

goods/services, is a fundamental example of sharing resources.7

Transferring competencies are taking something that an

organization is good at and using it in a new industry. The most famous

example of this of all time was Henry Ford and his mass

production/assembly line techniques. Today Ford is most famous for

cars, however Ford took his ideas and applied them to farm equipment,

large trucks, and even airplanes! Some of these businesses remain to

this day as you can still find Ford farm equipment.

Specific Assets. Much more complex is the idea of specific assets.

Specific assets are assets that have a much lower value in their next

best use OR to their next best user.8 A great example of a specific

asset might be a textbook for a college course. It has great value if you

are a college student in that course, but it doesn't have many alternate

uses, e.g. fire starter, and few people other than a college student

taking that course would pay a lot of money for it. Therefore, it is a

specific asset. Common examples of specific assets are things like

uniforms and pipelines. It may be helpful to think of specific assets as

assets that have been customized. This is because by customizing

something it frequently becomes more valuable to the person or firm

who did the customizing but less valuable to everyone else. Specific

assets are important for corporate strategy for two reasons. First, if

you don't own the specific asset it probably will not get created at all.

After all Ford is not likely to ever produce a car in your school’s color

scheme with your mascot painted on the hood. If you want one, you’ll

have to have it done yourself. Second, you frequently want to own

specific assets so that you are not "held up" by an opportunistic

partner. Hold up can occur when the provider of a specific asset

decides to withhold it from you at a critical time. For example, what if

you rented your

textbook from me rather than owned it? I might have an incentive to

increase the rental rate right before the exam when you needed the

book the most. You might be able to take me to court and win for

violation of contract, but by then the test is long past. You’ll have to

pay my higher rent.

This is what economists mean when they refer to

“hold up.”

A great illustration of the building blocks comes from Jack Welch’s

managerial evaluation system at GE - probably the most diversified

large company in the U.S. The central focus of the system was the

divisional director's ability to recognize, develop, and SHARE the talent

of their executives. If someone had someone who was really good at

solving problem X that another division had, then they were expected

to share that person. This further encouraged employees to devote

themselves to learning about GE and doing a great job, they knew

good work would be rewarded. This is a classic example of why sharing

resources, transferring competencies, and getting people to invest in

specific assets (especially important for organizational knowledge) is

important for the management and ongoing success of diversified

corporations. Managerial attention should be paid to these three

factors on an ongoing basis, not just at the time a diversification or

vertical integration decision is made.

Therefore, in order for a corporate strategic

decision to help result in a sustained competitive advantage for a firm

the benefits from the shared resources, transferred competencies, and

specific assets must be greater than the integration and bureaucratic

costs of performing the function internally.

However, this leads to an interesting question, what about firms that

have pursued completely unrelated diversification yet have performed

quite well? While these are rather rare, examples of these firms have

included Hanson Trust and present day Berkshire Hathaway (BRK).

What may have happened is that these firms wind up embodying a

control or resource allocation function (perhaps capital) that is superior

to what their component firms could do individually. For

example, Warren Buffet often targets acquisitions on the foundation of

taking away the current CEO's headaches of dealing with boards and

regulators and letting the CEO get back to focusing on running the

company that they love.9 This of course is just a transferred

competency on the part of BRK that takes over corporate governance

concerns of the CEO. Warren Buffet’s exceptional skill in investing

could also be a transferred competency and his company's excellent

credit rating a shared resource.

Warning on Matrices. Initially, consulting groups and managers

attempted to deal with the complex challenges of corporate strategy

through "matrices." The matrices, e.g. Boston Consulting Group (Stars,

Problem Children, Cash Cows, and Dogs), you often see associated

with corporate strategy can be great external analysis tools and visual

aids. However, since they don't tell you how to share resources,

transfer competencies, or create specific assets, they are

"mostly worthless" for explaining why firm performance differs. While

matrices may have some value as investment guides for managers,

there are superior frameworks for investing based on the work of

economists and financial experts, so their value here is suspect as well.

You might also like

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)From EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (25)

- Thomas Dorsey-Point and Figure Charting-EnDocument403 pagesThomas Dorsey-Point and Figure Charting-EnLily Wang100% (4)

- Types of MergersDocument13 pagesTypes of MergersJebin JamesNo ratings yet

- 73ac4horizontal & Vertical IntegrationDocument5 pages73ac4horizontal & Vertical IntegrationOjasvee KhannaNo ratings yet

- Consulting Interview Case Preparation: Frameworks and Practice CasesFrom EverandConsulting Interview Case Preparation: Frameworks and Practice CasesNo ratings yet

- Writing A Credible Investment Thesis - HBS Working KnowledgeDocument6 pagesWriting A Credible Investment Thesis - HBS Working KnowledgejgravisNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions Notes MBADocument24 pagesMergers and Acquisitions Notes MBAMandip Luitel100% (1)

- Horizontal and Vertical IntegrationDocument9 pagesHorizontal and Vertical IntegrationAmna Rasheed100% (1)

- Name: Zaffar-Ul-Lah Khan Class: Bba Vi Sec: (Ii) GR#: 252066Document7 pagesName: Zaffar-Ul-Lah Khan Class: Bba Vi Sec: (Ii) GR#: 252066Adeel Shafique KhawajaNo ratings yet

- Corporate StrategyDocument5 pagesCorporate StrategyMihir HariaNo ratings yet

- Corporate StrategyDocument9 pagesCorporate StrategyPallavi RanjanNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Concepts For ProfessionalsDocument6 pagesStrategic Management Concepts For Professionalsoumar06No ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisition Mba Final NotesDocument60 pagesMergers and Acquisition Mba Final NotestarunNo ratings yet

- Types of M&ADocument31 pagesTypes of M&Adhruv vashisth100% (1)

- CHAPTER 8 For Students (S.M.)Document6 pagesCHAPTER 8 For Students (S.M.)jeongyeonbin02No ratings yet

- TYPES OF MERGER and ACQUISITION (Based On Relatedness of Business)Document5 pagesTYPES OF MERGER and ACQUISITION (Based On Relatedness of Business)Urooba ZainNo ratings yet

- Lecture Topic 1Document30 pagesLecture Topic 1Sunaina BenNo ratings yet

- Mergers and DiversificationDocument6 pagesMergers and DiversificationJenny Rose Castro FernandezNo ratings yet

- Corporate Alliances and Acquisitions: Strategic Alliances Enable Companies To ShareDocument22 pagesCorporate Alliances and Acquisitions: Strategic Alliances Enable Companies To SharezachNo ratings yet

- Motives For Merger & AcquisitionDocument6 pagesMotives For Merger & AcquisitionFaisal KhanNo ratings yet

- FM Unit 5Document26 pagesFM Unit 5KarishmaNo ratings yet

- Introductio1 AmitDocument11 pagesIntroductio1 AmitKaranPatilNo ratings yet

- Are U Owner of Best AssetsDocument7 pagesAre U Owner of Best AssetsamitkulNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts: M & A DefinedDocument23 pagesBasic Concepts: M & A DefinedChe DivineNo ratings yet

- Activity # 3: Corporate Strategies: Questions 5.1Document5 pagesActivity # 3: Corporate Strategies: Questions 5.1Jonela LazaroNo ratings yet

- Channel MARKETING-finalDocument7 pagesChannel MARKETING-finalAhmadNo ratings yet

- Nature of Corporate RestructuringDocument5 pagesNature of Corporate RestructuringNadeem KhanNo ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument4 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsAnu SubediNo ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument33 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsRomNo ratings yet

- Horizontal Merger: Reason For MergersDocument5 pagesHorizontal Merger: Reason For MergershiteshNo ratings yet

- Micheal Anyika A.: What Is Supply Chain Design?Document19 pagesMicheal Anyika A.: What Is Supply Chain Design?spartNo ratings yet

- Porter's ForcesDocument5 pagesPorter's ForcesJoshua RamosNo ratings yet

- Backward IntegrationDocument10 pagesBackward IntegrationKrishelle Kate PannigNo ratings yet

- Synp 02 Growth Through Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument14 pagesSynp 02 Growth Through Mergers and AcquisitionsSamman GuptaNo ratings yet

- CH9-Diversification and AcquisitionsDocument9 pagesCH9-Diversification and AcquisitionsVincent LeruthNo ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument85 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsAnubhav AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Mergers and AcquisitionDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Mergers and AcquisitionkairavizanvarNo ratings yet

- Merger and AcquisitionsDocument16 pagesMerger and Acquisitionsanuja kharelNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4Document4 pagesTutorial 4Aminath AzneeNo ratings yet

- Organizational ArchitectureDocument3 pagesOrganizational ArchitectureFranciskaNo ratings yet

- Section C - 660 - SMDocument4 pagesSection C - 660 - SMDrPalanivel LpprvNo ratings yet

- CH 6Document6 pagesCH 6rachelohmygodNo ratings yet

- E-Commerce BCA S309FirstUnitRemainNotesDocument18 pagesE-Commerce BCA S309FirstUnitRemainNotesAshish SachanNo ratings yet

- Launching A Successful Business-to-Business Consortium: Opportunities For Action in Industrial GoodsDocument10 pagesLaunching A Successful Business-to-Business Consortium: Opportunities For Action in Industrial Goodstaona madanhireNo ratings yet

- MBA - N.DINESH - VUCA - Unit 3 - EnotesDocument21 pagesMBA - N.DINESH - VUCA - Unit 3 - EnotesRajeshNo ratings yet

- Strategic ManagementDocument14 pagesStrategic ManagementMAXWELL gwatiringaNo ratings yet

- Supply RiskDocument6 pagesSupply RiskFARAI KABANo ratings yet

- Porters 5 Mckinseys 7sDocument15 pagesPorters 5 Mckinseys 7sVernie O. HandumonNo ratings yet

- Project Paper 3PLDocument7 pagesProject Paper 3PLDinesh RamaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 International BusinessDocument12 pagesChapter 13 International BusinessnihalNo ratings yet

- Critical Success FactorsDocument4 pagesCritical Success FactorsAnonymous RVOJZzzhNo ratings yet

- SFMDocument10 pagesSFMSoorajKrishnanNo ratings yet

- Mission & Vision of The Firm Know Yourself: SWOT Analysis Scan External EnvironmentDocument14 pagesMission & Vision of The Firm Know Yourself: SWOT Analysis Scan External EnvironmentavijeetboparaiNo ratings yet

- Mergers & AcquisitionsDocument22 pagesMergers & AcquisitionsLAKHAN TRIVEDINo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 ReportDocument29 pagesChapter 10 ReportMay Jude Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- What's The Difference Between A Merger and An Acquisition? AnswerDocument4 pagesWhat's The Difference Between A Merger and An Acquisition? Answerjaiswalroshni05No ratings yet

- CH 05Document14 pagesCH 05leisurelarry999No ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument12 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsSaurav NishantNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management 2Document10 pagesMarketing Management 2Pankaj YadavanNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisition ProjectDocument21 pagesMergers and Acquisition ProjectNivedita Kotian100% (1)

- 2019491243256731WHTRateCardupdated09 03 19FinSupSecAmendAct2019Document5 pages2019491243256731WHTRateCardupdated09 03 19FinSupSecAmendAct2019Shoaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- Q2 FY22 Financial TablesDocument13 pagesQ2 FY22 Financial TablesDennis AngNo ratings yet

- ch01 The Role of Financial ManagementDocument25 pagesch01 The Role of Financial ManagementBagusranu Wahyudi PutraNo ratings yet

- Outreach NetworksDocument3 pagesOutreach NetworksPaco Colín50% (2)

- Global Trust BankDocument19 pagesGlobal Trust BankLawi Anupam33% (6)

- CDSL Kra PDFDocument5 pagesCDSL Kra PDFRamesh SathyamoorthiNo ratings yet

- Exit Offer Letter and Delisting Circular PDFDocument172 pagesExit Offer Letter and Delisting Circular PDFInvest StockNo ratings yet

- Earnings Per Share (Loi Nhuan Tren CP)Document34 pagesEarnings Per Share (Loi Nhuan Tren CP)Chi HoàngNo ratings yet

- Applied Corporate Finance: Journal ofDocument15 pagesApplied Corporate Finance: Journal ofTrâm Anh ĐoànNo ratings yet

- GenMath Q2 Mod13Document20 pagesGenMath Q2 Mod13roxtonandrada8No ratings yet

- Bailment and PledgeDocument14 pagesBailment and PledgeBijitashaw GøgøiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument5 pagesNew Microsoft Word Documentrajmv7No ratings yet

- International Banking EvolutionDocument8 pagesInternational Banking EvolutionKathleen Faith C. BrionesNo ratings yet

- Form ITR-6Document35 pagesForm ITR-6Accounting & TaxationNo ratings yet

- Unvielded - Final2Document102 pagesUnvielded - Final2massimoNo ratings yet

- Pro Forma Financial StatementsDocument3 pagesPro Forma Financial StatementsWaiLonn100% (1)

- Rescue3 AsdDocument7 pagesRescue3 AsdHay JirenyaaNo ratings yet

- Activity No. 1. Accounting PracticesDocument3 pagesActivity No. 1. Accounting PracticesNalin SNo ratings yet

- 1.5 Common Probability DistributionDocument48 pages1.5 Common Probability DistributionMarioNo ratings yet

- Utkashtripathi 11909588 Finca 2Document12 pagesUtkashtripathi 11909588 Finca 2vinay100% (1)

- Hexaware DelistingDocument48 pagesHexaware DelistingNihal YnNo ratings yet

- Comparison of AlternativesDocument26 pagesComparison of AlternativesMarielle CambaNo ratings yet

- Investment Property and Other InvestmentsDocument4 pagesInvestment Property and Other InvestmentsMiguel MartinezNo ratings yet

- Eliot Waves E Book Part1 PDFDocument13 pagesEliot Waves E Book Part1 PDFByron Arroba0% (1)

- DAX Performance Between 1959 and 2016: Foundation OperatorDocument6 pagesDAX Performance Between 1959 and 2016: Foundation OperatorJesu JesuNo ratings yet

- AssignmentsDocument2 pagesAssignmentsGauravGupta100% (1)

- Bond Analysis and ValuationDocument76 pagesBond Analysis and ValuationMoguche CollinsNo ratings yet

- Impact of Festival Affecting Stock Market Indices in BRICS RewrittenDocument9 pagesImpact of Festival Affecting Stock Market Indices in BRICS RewrittensushmasreedaranNo ratings yet

- Nest TraderDocument74 pagesNest Traderpercysearch100% (1)