Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Overconsumption in Rich Countries & Deforestation in Poor Countries

Overconsumption in Rich Countries & Deforestation in Poor Countries

Uploaded by

Nguyễn Thanh Tuyền0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views2 pagesThe document discusses how deforestation is often displaced from rich to poor countries due to international trade. While rich countries have increased forest cover at home, their consumption contributes to forest loss abroad through imports of goods like soy, beef, cocoa and timber. A study found that G7 countries contributed to a net loss of 20,000 sq km of foreign forests in 2015 alone. The location of deforestation matters - loss of forests in the Amazon basin cannot be offset elsewhere due to its biodiversity and carbon storage. To truly address deforestation, rich countries must ensure sustainable supply chains and imports in addition to domestic conservation efforts.

Original Description:

Original Title

Overconsumption in rich countries & deforestation in poor countries

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses how deforestation is often displaced from rich to poor countries due to international trade. While rich countries have increased forest cover at home, their consumption contributes to forest loss abroad through imports of goods like soy, beef, cocoa and timber. A study found that G7 countries contributed to a net loss of 20,000 sq km of foreign forests in 2015 alone. The location of deforestation matters - loss of forests in the Amazon basin cannot be offset elsewhere due to its biodiversity and carbon storage. To truly address deforestation, rich countries must ensure sustainable supply chains and imports in addition to domestic conservation efforts.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views2 pagesOverconsumption in Rich Countries & Deforestation in Poor Countries

Overconsumption in Rich Countries & Deforestation in Poor Countries

Uploaded by

Nguyễn Thanh TuyềnThe document discusses how deforestation is often displaced from rich to poor countries due to international trade. While rich countries have increased forest cover at home, their consumption contributes to forest loss abroad through imports of goods like soy, beef, cocoa and timber. A study found that G7 countries contributed to a net loss of 20,000 sq km of foreign forests in 2015 alone. The location of deforestation matters - loss of forests in the Amazon basin cannot be offset elsewhere due to its biodiversity and carbon storage. To truly address deforestation, rich countries must ensure sustainable supply chains and imports in addition to domestic conservation efforts.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 2

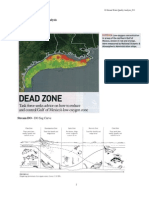

Daily chart

How rich countries cause deforestation in poor ones

Such losses cannot be offset by planting more trees at

FOREST ARE crucial to the functioning of the Earth. They provide homes for

plants and animals, absorb rainfall, produce oxygen and suck up carbon

dioxide, helping to keep global temperatures in check. Environmentalists are

increasingly worried about their loss. Then thousand years ago, more than half

of the world’s habitable land was covered in trees; since then one-third have

been cut down to make way for agriculture and an ever-growing number of

humans. Efforts to reserve this trend, including tree-planting programmes in

America, Europe, China and India, among other places, have helped replenish

some of what is left of the world’s forests.

But such gains do not tell the whole story. For all their tree-planting efforts at

home, rich countries continue to contribute, through their consumption, to the

levelling of vast tracts of forests in poor ones. A study, published on March 29 th

in Nature Ecology & Evolution, reveals the extent and location of the world’s

“deforestation footprint”. Keiichiro Kanemoto and Nguyen Tien Hoang, of the

Research Institute of Humanity and Nature in Japan, combined date on global

forest loss with that on international trade between 2001 and 2015. They

calculated that rich-country demand for goods led overwhelmingly to

deforestation outside their own borders, and mostly in tropical countries. In

G7 countries, for example, the area covered by forests increase every year

between 2001 and 2015. But after adjusting for trade, the authors found that

these countries contributed to a net loss of 20,000 square kilometres of forest

in the rest of the world in 2015 alone.

Each country has a unique deforestation footprint. Japan’s hankering for

cotton and sesame seeds, for example, has led in particular to the destruction

of trees in coastal Tanzania; Germany’s appetite for cocoa has contributed to

the stripping of forests in Ghana and Ivory Coast; China’s demand for timber

and rubber has helped to wipe out forest in Indochina. America, for its part, is

responsible for deforestation in Cambodia (timber)m Liberia (rubber),

Guatemala (fruit and nuts) and Brazil (soya and beef).

The location of such deforestation matters. Amazon basin, which mostly sits in

Brazil, is home to 40% of the world’s tropical forests and as much as 15% of all

the biodiversity on Earth. It also stores tens of billions of tonnes of carbon. The

destruction of the Amazon rainforest cannot be mitigated by planting trees

elsewhere: Mr Kanemoto and Mr Nguyen estimate that the environmental

impact of losing three Amazonian trees might be more severe than the loss of

14 trees in a boreal forest in country like Norway. Younger forests also may

have less carbon-sequestering ability than old ones, because they aren’t as tall.

The authors argue that it is not enough for rich countries to stop deforestation

at hone – they have to make sure their imports are sustainable, too. There is

some evidence that this is starting to happen. Joe Biden, America’s president,

has signalled that his diplomatic relationship with Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s

president, will hinge at least in part on whether the latter halts destruction of

the Amazon.

Đọc bài báo này để hiểu tại sao xu hướng tiêu dùng quá mức

(overconsumption) ở người giàu đã góp phần tàn phá rừng (deforestation) ở

các nước nghèo.

You might also like

- Aeration Manual DRAFT P PDFDocument251 pagesAeration Manual DRAFT P PDFgarisa1963100% (1)

- DeforestationDocument5 pagesDeforestationapi-408889360No ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document5 pagesChapter 4Nguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - MMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila BayDocument3 pagesCase Digest - MMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila BayJessica Vien Mandi91% (11)

- Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-36357025567% (12)

- Environmental issue-INTERNATIONALDocument3 pagesEnvironmental issue-INTERNATIONALSophia TorioNo ratings yet

- FAO National Geographic: LocationDocument3 pagesFAO National Geographic: LocationYashi KanodiaNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis About DeforestationDocument11 pagesCase Analysis About DeforestationMaria De leonNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument4 pagesDeforestationAlejandro CaramNo ratings yet

- The Consequences of Deforestation On The Evironment Consecinţele Despăduririlor Asupra MediuluiDocument4 pagesThe Consequences of Deforestation On The Evironment Consecinţele Despăduririlor Asupra MediuluiTeodora RNo ratings yet

- Impact of Deforest Ration On ClimateDocument13 pagesImpact of Deforest Ration On ClimateMohSin KawoosaNo ratings yet

- TITLEDocument6 pagesTITLEJulius MacaballugNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument5 pagesBackground of The StudyRolly GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Deforestation: Global Impact, Causes and RecommendationsDocument16 pagesDeforestation: Global Impact, Causes and RecommendationsP Yadav100% (1)

- Deforestation and Its Impact On Environment: Gursharn Singh, Beant SinghDocument7 pagesDeforestation and Its Impact On Environment: Gursharn Singh, Beant SinghChaitanya KadambalaNo ratings yet

- Deforestation (TEXTO)Document5 pagesDeforestation (TEXTO)Otoniel MaciasNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument3 pagesDeforestationRiza NgampusNo ratings yet

- Understanding DeforestationDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Deforestationapi-441535475No ratings yet

- Deforestation Causes, Effects, and Solutions: TOPIC: For The Month MAY 2019Document5 pagesDeforestation Causes, Effects, and Solutions: TOPIC: For The Month MAY 2019Marlon BongatoNo ratings yet

- TV Show: 1.the Real State of DeforestationDocument3 pagesTV Show: 1.the Real State of DeforestationChau HoangNo ratings yet

- Deforestation: Object 1 Object 2 Object 3 Object 4 Object 5 Object 6Document7 pagesDeforestation: Object 1 Object 2 Object 3 Object 4 Object 5 Object 6ANITTA SNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument5 pagesDeforestationonofreiilincaNo ratings yet

- Deforestation ProjectDocument10 pagesDeforestation ProjectSiddhi TarmaleNo ratings yet

- What Is DeforestationDocument5 pagesWhat Is DeforestationRonaldo AlocNo ratings yet

- Effects of DeforestationDocument15 pagesEffects of DeforestationLuis AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- Causes and Effects of DeforestationDocument2 pagesCauses and Effects of DeforestationDhexter L PioquintoNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument6 pagesDeforestationShubam SharmaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Part 1 - ANGKA GAS12-ADocument3 pagesAssignment Part 1 - ANGKA GAS12-AAndre AngkaNo ratings yet

- Deforestation Essay ThesisDocument7 pagesDeforestation Essay Thesisczbsbgxff100% (2)

- Deforestation: Jungle Burned For Agriculture in Southern MexicoDocument15 pagesDeforestation: Jungle Burned For Agriculture in Southern Mexicoshanmu666No ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument18 pagesDeforestationYzel DuroyNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument10 pagesDeforestationCynthia UnayNo ratings yet

- Forests Extension Information SheetDocument2 pagesForests Extension Information SheetMuskanNo ratings yet

- Position Paper G2Document16 pagesPosition Paper G2Aerish RioverosNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument6 pagesDeforestationJhonsenn Escosio RudioNo ratings yet

- Scientific Investigation Group 8Document2 pagesScientific Investigation Group 8kyoto.saeopNo ratings yet

- Manacio Tedx ScriptDocument2 pagesManacio Tedx ScriptEianna Lian SencioNo ratings yet

- Tedx ScriptDocument2 pagesTedx ScriptEianna Lian SencioNo ratings yet

- PBL Activity Group 3Document14 pagesPBL Activity Group 3Shailja BidaliaNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument5 pagesDeforestationRAFAEL CARLOS OMANANo ratings yet

- 1shweta EvsDocument6 pages1shweta EvsSiddhi Nitin MahajanNo ratings yet

- Forest EcosystemDocument3 pagesForest EcosystemKarpagam MahadevanNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Paper On Forest IssuesDocument6 pagesSynthesis Paper On Forest IssuesCallisto AstraeaNo ratings yet

- Baby ThesisDocument13 pagesBaby ThesisbarrymapandiNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument6 pagesDeforestationKristine Camille Sadicon Morilla100% (1)

- Course Name-Environmental Studies Topic-Forest Resources: Reference VideoDocument4 pagesCourse Name-Environmental Studies Topic-Forest Resources: Reference VideoMitali GuptaNo ratings yet

- 10 Negative Effects of Deforestation Human Rights CareersDocument1 page10 Negative Effects of Deforestation Human Rights CareersAllyssia Reigne SubidoNo ratings yet

- (Template) Englishdaily626 - Comprehension - 303Document2 pages(Template) Englishdaily626 - Comprehension - 303Rosanna ChioNo ratings yet

- Deforestation 1 Running Head: Deforestation of The Amazon Tropical RainforestDocument11 pagesDeforestation 1 Running Head: Deforestation of The Amazon Tropical RainforestKimani AllenNo ratings yet

- Deforestation in The Amazon - Dion Gilbert 1Document6 pagesDeforestation in The Amazon - Dion Gilbert 1api-547304115No ratings yet

- Deforestation: Deforestation Is The Clearance of Forests byDocument5 pagesDeforestation: Deforestation Is The Clearance of Forests byAbinayaNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Study Project: DeforestationDocument34 pagesWelcome To Study Project: DeforestationJoseph ChayengiaNo ratings yet

- Meded 9Document6 pagesMeded 9api-553659197No ratings yet

- Deforestation: Causes, Effects and Control StrategiesDocument9 pagesDeforestation: Causes, Effects and Control StrategiesSuper Star100% (1)

- Sample Term Paper About DeforestationDocument4 pagesSample Term Paper About DeforestationCustomizedWritingPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Effects of Deforestation: Live in ForestsDocument4 pagesEffects of Deforestation: Live in ForestsLaboni JudNo ratings yet

- Forest Ecosystem Threats and ProblemsDocument6 pagesForest Ecosystem Threats and Problemsdigvijay909No ratings yet

- Thesis Papers DeforestationDocument4 pagesThesis Papers Deforestationk1lod0zolog3100% (1)

- Deforestation Is The Permanent Destruction of Indigenous Forests and WoodlandsDocument3 pagesDeforestation Is The Permanent Destruction of Indigenous Forests and WoodlandsTara Idzni AshilaNo ratings yet

- Global Environment Issues and ConcernsDocument25 pagesGlobal Environment Issues and ConcernsCyrose John SalasNo ratings yet

- Forest Management Guide: Best Practices in a Climate-Changed World: Best Practices in a Climate Changed WorldFrom EverandForest Management Guide: Best Practices in a Climate-Changed World: Best Practices in a Climate Changed WorldNo ratings yet

- Why Is Free Trade GoodDocument2 pagesWhy Is Free Trade GoodNguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Test 1 Reading Passage 1Document11 pagesTest 1 Reading Passage 1Nguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- HanYu JiaoCheng XiuDingBen - DiErCe Shang - Q3Document7 pagesHanYu JiaoCheng XiuDingBen - DiErCe Shang - Q3Nguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document9 pagesUnit 1Nguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Noun ClauseDocument17 pagesNoun ClauseNguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Noun ClauseDocument17 pagesNoun ClauseNguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Rewrite Presidential ElectionDocument2 pagesRewrite Presidential ElectionNguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument2 pagesEssayNguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Week 4Document10 pagesVocabulary Week 4Nguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Environmental Impact Assessment: Ting Ting Hydroelectric Project, SikkimDocument18 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment: Ting Ting Hydroelectric Project, SikkimShreya MalikNo ratings yet

- Essay - How We Can Solve The Problem of Bottled Water? Angelika Taranenko, UE-16-1Document1 pageEssay - How We Can Solve The Problem of Bottled Water? Angelika Taranenko, UE-16-1Lika TaranenkoNo ratings yet

- Civil Drip Irrigation Report - 2Document20 pagesCivil Drip Irrigation Report - 2Deepak kumar YADAV57% (7)

- Sewage Treatment Plant Report For M/s Santla Devi Resorts Pvt. LTDDocument7 pagesSewage Treatment Plant Report For M/s Santla Devi Resorts Pvt. LTDSamNo ratings yet

- Phthalate Free Plasticizers in PVCDocument26 pagesPhthalate Free Plasticizers in PVCJuan Krloz Castañeda100% (1)

- Air PollutionDocument21 pagesAir PollutionstephanievogelNo ratings yet

- World Bank Report 2019 PDFDocument135 pagesWorld Bank Report 2019 PDFSamson RaphaelNo ratings yet

- GIL074 Domestic Condensing BoilersDocument4 pagesGIL074 Domestic Condensing BoilersIppiNo ratings yet

- Building Materials Reuse and RecycleDocument10 pagesBuilding Materials Reuse and RecyclemymalvernNo ratings yet

- NF P90 306 Piscinas FranciaDocument3 pagesNF P90 306 Piscinas FranciaJoseNo ratings yet

- 17-Stream Water Quality Analysis - F11Document12 pages17-Stream Water Quality Analysis - F11Michelle de Jesus100% (1)

- Abyip 2024Document7 pagesAbyip 2024Jo-em G. PadrigonNo ratings yet

- Triple Bottomline - ClassDocument11 pagesTriple Bottomline - ClassM ManjunathNo ratings yet

- Water Quality Modeling Pdf1Document11 pagesWater Quality Modeling Pdf1Juan Manuel Sierra Puello13% (8)

- Environmental Management 3Document28 pagesEnvironmental Management 3Shalinette PorticosNo ratings yet

- Nama PDD Wte Moldova enDocument107 pagesNama PDD Wte Moldova enGk MenonNo ratings yet

- Konkan Coastal Tourism - 2007Document30 pagesKonkan Coastal Tourism - 2007Kiran KeswaniNo ratings yet

- Incineration-Environment Group AssignmentDocument5 pagesIncineration-Environment Group AssignmentGary Chen100% (1)

- Indore Presentation - 23.02.15Document48 pagesIndore Presentation - 23.02.15arthiarulNo ratings yet

- SN2B02 Group ADocument22 pagesSN2B02 Group Aapple chanNo ratings yet

- Use of Waste Plastic in Flexible PavementDocument4 pagesUse of Waste Plastic in Flexible PavementEttaMahenderNo ratings yet

- DesalinizaciónDocument48 pagesDesalinizaciónLoren AlayoNo ratings yet

- Congreso - Cierre de Minas PDFDocument531 pagesCongreso - Cierre de Minas PDFYordy AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Disposal of Solid WastesDocument10 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Disposal of Solid WastesJoel CuestasNo ratings yet

- Indian Social and Political Environment Reflection-2: House On Fire-India's Ecological Security UnderminedDocument3 pagesIndian Social and Political Environment Reflection-2: House On Fire-India's Ecological Security UnderminedAnirban ChandraNo ratings yet

- COMPRO IGE 2020updateDocument14 pagesCOMPRO IGE 2020updateTrianda RusadiNo ratings yet

- Joint Motion For Prompt Referral of Question To SWRCB 03-21-18Document15 pagesJoint Motion For Prompt Referral of Question To SWRCB 03-21-18L. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- Identifikasi Penggunaan Lahan Di Hutan Lindung Kebun Kopi Desa Nupabomba Kecamatan Tanantovea Kabupaten Donggala Witno, Akhbar, Ida ArianingsihDocument10 pagesIdentifikasi Penggunaan Lahan Di Hutan Lindung Kebun Kopi Desa Nupabomba Kecamatan Tanantovea Kabupaten Donggala Witno, Akhbar, Ida ArianingsihMonalisa PutriNo ratings yet