Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Maqāma Collection by A Mamlūk Historian: Mu Ammad Al - Afadī (Fl. First Quarter of The 8th/14th C.)

A Maqāma Collection by A Mamlūk Historian: Mu Ammad Al - Afadī (Fl. First Quarter of The 8th/14th C.)

Uploaded by

mpomeranOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Maqāma Collection by A Mamlūk Historian: Mu Ammad Al - Afadī (Fl. First Quarter of The 8th/14th C.)

A Maqāma Collection by A Mamlūk Historian: Mu Ammad Al - Afadī (Fl. First Quarter of The 8th/14th C.)

Uploaded by

mpomeranCopyright:

Available Formats

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

brill.com/arab

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian:

al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya by al-Ḥasan b. Abī

Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī (fl. First Quarter of the

8th/14th c.)

Maurice A. Pomerantz

New York University Abu Dhabi

Abstract

This article is a description and guide to the contents of al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya by

al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī (fl. first quarter of the 8th/14th c.). The article

begins with a discussion of the life of the author al-Ṣafadī and his works. It provides

evidence for his biography derived from unpublished manuscript sources. The article

then considers features of the authorial context of al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, including

notes found in Laleli MS 1929, and evidence for the dedication of al-Maqāmāt

al-Ǧalāliyya to the famed geographer, historian, and ruler of Hama, al-Malik

al-Muʾayyad Abū l-Fidāʾ (672/1273-732/1332). The remainder of the article provides a

description of al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, its narrative structures, the contents of the

thirty individual maqāmāt, and explores parallels between al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya

and other works of the maqāma genre. The final section includes a sample text of

al-Maqāma l-Tīzīniyya and an accompanying commentary.

Keywords

classical Arabic literature, picaresque, maqāma, Mamlūk, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya,

al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī, al-Malik al-Muʾayyad Abū l-Fidāʾ

* The author would like to express his utmost thanks to Prof. Bilal Orfali (Beirut), Dr. John

Meloy (Beirut) and Prof. Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Helsinki) for their comments and sugges-

tions on this article.

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���4 | doi ��.����/�5700585-12341326

632 Pomerantz

Résumé

Cet article est une description et un guide de lecture pour al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya

d’al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī (fl. premier quart du VIIIe/XIVe siècle). L’article

commence par une évocation de la vie de l’auteur al-Ṣafadī et de ses œuvres. Des élé-

ments historiques provenant de sources manuscrites inédites y sont donnés pour sa

biographie. L’article examine ensuite les caractéristiques du contexte d’écriture d’al-

Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, en s’appuyant sur des notes trouvées dans le MS Laleli 1929, et

la dédicace d’al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya au célèbre géographe, historien et gouverneur

de Hama, al-Malik al-Muʾayyad Abū l-Fidāʾ (672/1273–732/1332). Le reste de l’article

fournit une description d’al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, de ses structures narratives, du

contenu de chacune des trente maqāmāt, et explore les parallèles entre al-Maqāmāt

al-Ǧalāliyya et d’autres œuvres du genre des maqāmāt. La dernière section comprend

le texte d’al-Maqāma l-Tīzīniyya et un commentaire d’accompagnement.

Mots clés

littérature arabe classique, picaresque, maqāma, Mamelouks, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya,

al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī, al-Malik al-Muʾayyad Abū l-Fidāʾ

1 Al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī and his al-Maqāmāt

al-Ǧalāliyya

Al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya is a collection of thirty maqāmāt written in the early

8th/14th century. It has heretofore not been included in any general study of

the maqāma genre.1

The work is preserved in two manuscripts:

1.) Istanbul, Laleli collection, MS no. 1929, copied in 727/1327.2

1 For a general overview of this period, see Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila, Maqama: A history of a

genre, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz, 2002, p. 328-346; Devin Stewart, “The maqāma”, in The

Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: Arabic Literature in the Post-Classical Period, ed.

R. Allen and D.S. Richards, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 145-159.

2 Oskar Rescher, “Über arabische Manuscripte der Lālelī-moschee”, Le Monde Oriental, 7, (1913),

p. 10; see Brockelmann, GAL, S II, p. 208; a microfilm of this work is found in the Institute for

Arabic Manuscripts in Cairo, see Fihris al-Maḫṭūṭāt al-Muṣawwara, ed. Ayman Fuʾād Sayyid,

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 633

2.) Cairo, Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya, Taymūr (adab) 293, copied in 1097/

1685-1686.3

The author of the MǦ is Ǧalāl al-Dīn al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī

l-Barīdī.4 In addition to the MǦ, he also composed a minor chronicle of Egypt

written during the reign of the Egyptian sultan al-Malik al-Nāṣir Muḥammad

b. Qalāwūn (d. 741/1341), Nuzhat al-mālik wa-l-mamlūk.5 Biographical sources

of the Mamlūk period do not mention al-Ṣafadī, and thus, his date of birth and

death are both unknown.6

An outline of al-Ṣafadī’s life can be reconstructed from various notices

that he supplies in his own works as well as contemporary sources. Al-Ṣafadī

traced his lineage seven generations back to the ʿAbbāsid caliph al-Muhtadī

(r. 255/869-256/870).7 He spent his early years in the city of Ṣafad in the Galilee.

After the sultan Baybars (r. 658/1260-676/1275) destroyed the Frankish garrison

that was stationed there in 664/1266, Ṣafad became an administrative center

for the Mamlūk dynasty of Egypt and Syria.

Cairo, Maʿhad iḥyāʾ al-maḫṭūṭāt al-ʿarabiyya, 1954, I, p. 530; see also Hämeen-Anttila, Maqama,

p. 385.

3 Fihris al-maḫṭūṭāt al-muṣawwara fī Dār al-kutub, ed. ʿI. al-Šanṭī, Cairo, Maʿhad al-maḫṭūṭāt

al-ʿarabiyya, 1996, I, p. 75-76.

4 Al-Ṣafadī presented his name in different forms depending on the context; for example, at

the conclusion of his Āṯār al-uwal fī tartīb al-duwal, ed. ʿA. ʿUmayra, Beirut, Dār al-ǧīl, 1989, p. 373,

he states that his name is al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar b. Maḥāsin b. ʿAbd

al-Karīm b. ʿAbd al-Muḥsin b. ʿAbd al-Karīm b. Muḥammad b. Hārūn b. Muḥammad b. Hārūn

Abī Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh b. al-ʿAbbās; in Husām b.

al-ʿAṭṭār, al-Maqāmāt al-Qurašiyya, MS Aya Sofya 4297, f. 219b, al-Ṣafadī states that his name is

al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar al-Hāšimī l-ʿAbbāsī; whereas in his history,

Nuzhat al-mālik wa-l-mamlūk fī muḫtaṣar sīrat man waliya Miṣr min al-mulūk, ed. ʿUmar

al-Tadmurī, Beirut, Ṣaydā, 2003, p. 172, al-Ṣafadī provides al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-Ṣafadī.

5 F. Krenkow and D.P. Little, “al-Ṣafadī, al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh al-Hāshimī”, EI2;

Donald P. Little, An Introduction to Mamlūk Historiography, Wiesbaden, Franz Steiner, 1970,

pp. 38-39.

6 Al-Ṣafadī, Nuzha, p. 6.

7 Al-Ṣafadī emphasizes his ʿAbbāsid lineage enumerating his caliphal ancestors in the opening

of al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 2b: al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar b. Maḥāsin

b. ʿAbd al-Karīm b. ʿAbd al-Muḥsin b. ʿAbd al-Karīm b. Muḥammad al-Muhtadī bi-Llāh amīr

al-muʾminīn b. Hārūn al-Wāṯiq b. amīr al-muʾminīn Muḥammad al-Muʿtaṣim b. amīr

al-muʾminīn Hārūn al-Rašīd b. amīr al-muʾminīn Muḥammad al-Mahdī b. amīr al-muʾminīn

ʿAbd Allāh al-Manṣūr b. Muḥammad al-Kāmil b. ʿAlī l-Saǧǧād b. ʿAbd Allāh Ḥibr al-Umma

l-ʿAbbās al-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad al-ʿAbbāsī.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

634 Pomerantz

In 685/1285, al-Ṣafadī studied with the Sufi scholar and littérateur Ḥusām

al-Dīn b. al-ʿAṭṭār, who was the commander (isbāsalār) of the fortress of Ṣafad.8

In the year 687/1287, al-Ṣafadī departed Ṣafad, likely heading to Cairo where he

found employ in the Mamlūk administration and postal service.

Al-Ṣafadī was not a prolific author by the standards of his contemporaries

in the Mamlūk period, but several of his works concerning history and politics

have survived:

1. Nuzhat al-mālik wa-l-mamlūk fī muḫtaṣar sīrat man waliya Miṣr min

al-mulūk

ʿUmar al-Tadmurī prepared an edition based on the British Museum manu-

script.9 Although al-Ṣafadī begins his short chronicle with the history of the

Pharaohs, he devotes approximately half of his narrative to events concerning

the Mamlūk Sultanate in Egypt and Syria, concluding his account in the year

717/1317.

2. Al-Āṯār al-uwal fī tartīb al-duwal

This work is extant in one manuscript and has been edited and published. It

focuses on political theory and advice for rulers.10 Al-Ṣafadī quotes several pas-

sages from this work in his MǦ.11

3. Al-Taḏkira l-kāmiliyya fī l-siyāsa l-mulūkiyya

Possibly the same work as #2.

As can be seen from notices in these works, al-Ṣafadī was close to several of the

Mamlūk sulṭāns. In the Nuzhat al-mālik wa-l-mamlūk, al-Ṣafadī states that he

was sent on a mission on behalf of the Mamlūk vizier Faḫr al-Dīn b. ʿUmar b.

al-Ḫalīlī al-Dārī to the village of Fāqūs in the province of al-Šarqiyya in Egypt

in the year 694/1294-5. He describes in detail how he witnessed the gruesome

sight of a woman in the process of cooking her husband’s corpse on account

of the major famine that had befallen the region. Al-Ṣafadī, thus, must have

8 R. Amitai-Preis, “Ṣafad”, EI 2; Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 1b.

9 Al-Ṣafadī, Nuzha.

10 Al-ʿAbbāsī, Āṯār al-uwal fī tartīb al-duwal.

11 Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, MS Laleli 1929, the relevant passages are found in

al-Māqama al-Ǧārraḥiyya (ff. 129b-140b). References to the corresponding pages in

al-Āṯār al-uwal fī tartīb al-duwal are cited below in the discussion pertaining to this

maqāma.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 635

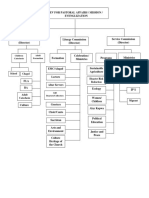

al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, MS Laleli 1929 fol. 2a.

begun his service in the Mamlūk administration as a scribe for Zayn al-Dīn

Kitbuġā al-Manṣūrī (r. 694-696/1295-1297).12

Al-Ṣafadī continued to serve in the state administration during the next

decade. In the introduction to his work, al-Āṯār al-uwal fī tartīb al-duwal, on

the conduct of the ruler, there is a praise poem addressed to the sulṭān Baybars

al-Manṣūrī Ǧašnakīr (r. 708-709/ 1308-1309).13

He also had ties to the sulṭān al-Malik Muḥammad al-Nāṣir (r. 709-741/1309-

1340) whom he praised in a poem quoted in his Nuzhat al-mālik wa-l-mamlūk.14

12 Al-Ṣafadī, Nuzha, p. 172-3.

13 Al-ʿAbbāsī, Āṯār al-uwal, p. 44-45.

14 Al-Ṣafadī, Nuzha, p. 179.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

636 Pomerantz

His relations with the sulṭān may have continued for some time, for Ibn

al-Dawādārī in his Kanz al-Durar mentions that al-Ṣafadī authored a poem for

the ruler later in his reign.15

2 Further Details of al-Ṣafadī’s Biography Drawn from the MǦ and the

Circumstances of its Authorship

Comments in the introduction to the MǦ provide further evidence about

al-Ṣafadī’s identity and the circumstances of the authorship of this collection

of maqāmāt. As noted above, al-Ṣafadī states that he first took an interest in

maqāma composition in 685/1285-1286 when he met with Ḥusām al-Dīn Ḫalīl

b. al-ʿAṭṭār al-Ḥalabī, who was, at that time, the commander (isbāsalār) of the

fortress of Ṣafad:

[. . .] in the months of the year 685/1285-1286, I met with Ḥusām al-Dīn

Ḫalīl b. Muḥammad b. al-ʿAṭṭār al-Ḥalabī, author of maqāmāt and inter-

preter of dreams. He was at that time the ruler of the fortress of Ṣafad. He

had composed fifty maqāmāt and I studied them with him. Among their

number, there were two maqāmāt, the first was a maqāma of pious

exhortation and the second includes the commentary of a schoolteacher.

I left him [viz. Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār] in the year 687/1287. He died after the siege of

Acre [i.e. 691/1291].

[. . .] annanī fī šuhūr sanat ḫams wa-ṯamānīn wa-sittimiʾa ǧtamaʿtu

bi-Ḥusām al-Dīn Ḫalīl b. al-ʿAṭṭār al-Ḥalabī wa-huwa yawmaʾiḏin isbāsalār

qalʿat Ṣafad al-maḥrūsa ṣāḥib al-maqāmāt al-saniyya wa-muʿabbir

al-manāmāt wa-qad ṣannafa l-maqāmāt ḫamsīn maqāma wa-qaraʾtu

ʿalayhi l-baʿḍ minhā wa-kāna min ǧumlatihā maqāmatān al-ūlā waʿẓiyya

wa-l-ṯāniya tataḍammanu šarḥ muʿallim al-maktab wa-fāraqtuhu fī ṣafar

sanat sabʿ wa-ṯamānīn wa-sittimiʾa wa-tuwuffiya ilā raḥmat Allāh taʿālā

baʿd fatḥ ʿAkkā.16

Al-Ṣafadī then states that he spent the next thirty three years [i.e. until c.

720/1320] in search of a copy of Ibn ʿAṭṭār’s Maqāmāt, until he finally found a

copy in the hands of a nephew of Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār in Gaza:

15 Ibn al-Dawādārī, Kanz al-durar wa-ǧamiʿ al-ġurar, ed. H.R. Roemer, Cairo, Sāmī l-Ḫānǧī,

1960, p. 310.

16 Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 1b.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 637

I kept hoping to find the Maqāmāt of Ibn ʿAṭṭār for thirty three years until

I found them in the possession of his nephew in Gaza. I borrowed them

from him and I copied them in Noble Cairo. Yet I did not find the two

maqāmāt, which had been replaced [in the collection] by two other

maqāmāt, thus completing the fifty [original] maqāmāt. And thus I

remained in sorrow for their loss, and then I sought guidance from God,

and I struck the flints of my mind, and there appeared a flash about a

maqāma concerning the alphabet. So I wove it on his loom, and I fol-

lowed the trace of his speech rather than his literal words. Then God

inspired me after this to author one maqāma after another until with the

help and praise of God, I reached thirty maqāmāt.

Wa-ẓalltu [sic] muddat ṯalāṯ wa-ṯalāṯīn sana atawaqqaʿu ʿalā l-maqāmāt

fa-lammā waǧadtuhā ʿinda walad aḫīhi bi-madīnat Ġazza staʿartuhā

minhu wa-nasaḫtuhā bi-l-Qāhira l-Muʿizziyya fa-lam aǧid al-maqāmatayn

fīhā wa-sudda l-maqāmāt bi-ġayrihimā wa-kulluhā ḫamsīn maqāma

fa-baqītu mutaʾassif ʿalayhimā fa-ʿinda ḏālika staḫartu Llāh taʿālā

wa-qadaḥtu zinād fikrī fa-ẓaharat lī bāriqa fī maʿnā l-maqāma l-muʿǧama

fa-nasaǧtu ʿalā minwālihi wa-qafawtu āṯār maqālihi lā qālihi ṯumma futiḥa

ʿalayya ʿalā aṯarihā bi-waḍʿ maqāma baʿd maqāma ilā an kammaltuhā

bi-ʿawn Allāh wa-ḥamdihi ṯalāṯīn maqāma.17

In addition to these thirty maqāmāt, al-Ṣafadī states that he added twenty five

additional maqāmāt as a supplement (takmila) bringing the total of his collec-

tion to fifty five maqāmāt. These additional maqāmāt do not appear to have

survived. In the conclusion to his introduction, al-Ṣafadī apologizes for the

shortcomings of his collection. He ends with the following lines stating that he

had been busy for some time with his work in the postal service:

For he [the author] was busy with military affairs and engrossed in the

postal service. And this was despite the need to socialize with people he

needed to consort with, of the sort who do not recognize excellence and

cannot “distinguish the flint from the wick,” from those recalcitrant chil-

dren and inimical babes.

Fa-innahu muštaġil bi-ǧundiyya wa-mutawaġġil fī l-waẓīfa l-barīdiyya

hāḏā maʿa muǧālasatihi man lā budda min muǧālasatihi mimman

17 Ibid., f. 2a.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

638 Pomerantz

yaǧhalu l-faḍīla wa-lā yufarriqu bayna l-zinād wa-l-fatīla min al-ʿiyāl

al-aliddāʾ wa-l-aṭfāl al-aʿdāʾ.18

3 Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār and al-Ṣafadī

The scholar Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār with whom al-Ṣafadī studied and whom he men-

tions in his introduction is the Sufi, Abū Isḥāq Ḫalīl b. Abī l-Rabīʿ Sulaymān b.

Abī l-Fatḥ Ġāzī. Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār authored a group of fifty maqāmāt in the style of

al-Ḥarīrī.19 In addition to his maqāmāt collection, Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār also composed

a work of Sufi doctrine, Kitāb Buġyat al-nāhiǧīn fī šarḥ Maqāmāt al-sāʾirīn (The

Desire of those who Travel: Commentary on The Stations of the Wayfarers).20

This work, copied in 688/1288, is a commentary on the famed Manāzil al-sāʾirīn

of Abū Ismāʿīl ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad al-Anṣārī l-Harawī (d. 481/1089).21

A copy of Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār’s al-Maqāmāt al-Qurašiyya is extant in a unicum

manuscript, MS Istanbul, Aya Sofya, 4297. On the title page of this manuscript,

al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī, is identified prominently as the copyist and commentator on

this work:

This work was composed by the mendicant slave of God Abū Isḥāq Ḫalīl

b. Abī l-Rabīʿ Sulaymān b. Abī l-Fatḥ Ġāzī b. Abī l-Ḥasan b. ʿAbd al-Ǧabbār

b. ʿAbd al-Malik al-Qurašī l-Ḥalabī l-Ḥanbalī known as Ḥusām b. al-ʿAṭṭār.

May God have mercy on him and upon his two parents and all of the

Muslims. The mendicant slave of God Abū ʿAlī l-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad

ʿAbd Allāh b. Abī Ḥafṣ ʿUmar b. Maḥāsin b. ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Hašimī

l-ʿAbbāsī, known as al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī has copied and commented on it.

And I read the majority of it in the presence of its author in the months

of the 685/1285 in the fortress of Ṣafad in a number of sessions.

Taʾlīf al-ʿabd al-faqīr ilā Llāh Abī Isḥāq Ḫalīl b. Abī l-Rabīʿ Sulaymān b. Abī

l-Fatḥ Ġāzī b. Abī l-Ḥasan ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-Ǧabbār b. ʿAbd al-Malik al-Qurašī

l-Ḥalabī l-Ḥanbalī l-maʿrūf bi-Ḥusām b. al-ʿAṭṭār ʿafā Llāh ʿanhu wa-ʿan

18 Ibid., f. 3a.

19 Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila, Maqama, p. 328, notes the possible confusion of al-Ḥusayn b.

al-ʿAṭṭār said to have written around 685/1286 with the later maqāma author, Ḥasan

al-ʿAṭṭār (d. 1250/1854). His suspicion is justified, for the name al-Ḥusayn b. al-ʿAṭṭār,

should be read as Ḥusām b. al-ʿAṭṭār.

20 MS Paris, BnF, Arabe 1345.

21 Al-Anṣārī l-Harawī, Manāzil al-sāʾirīn, Beirut, Muʾassassat al-balāġ, 2004.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 639

wālidayhi wa-ʿan ǧamīʿ al-muslimīn nasaḫahā wa-ʿallaqahā l-faqīr ilā Llāh

taʿālā Abū ʿAlī l-Ḥasan b. Abī Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh b. Abī Ḥafṣ ʿUmar b.

Maḥāsin b. ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Hāšimī l-ʿAbbāsī ʿurifa bi-l-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī

wa-qaraʾtu ʿalā muṣannifihā akṯarahā fī šuhūr sanat ḫams wa-ṯamānīn

wa-sittimiʾa bi-qalʿat Ṣafad fī maǧālis ʿidda.22

The colophon of this manuscript states that al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī completed this

copy of the al-Maqāmāt al-Qurašiyya in 721/1321 in Cairo, which squares well

with al-Ṣafadī’s report in the MǦ that he found the works of Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār in

720/1320.23 Al-Ṣafadī describes in the colophon of the manuscript how he had

studied with Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār, providing a slightly different version of his search for

the lost manuscript of the Maqāmāt:

From what the copyist says—may God have mercy upon him—I studied

most of these maqāmāt with their author—may God have mercy upon

him—in the fortress of Ṣafat [sic] the safeguarded, while he was its

isbāsalār in the months of the year 686/1286. Then I left him in the month

of ṣafar 687 and I continued to look for them until I found them in the

possession of his son, ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlī. He is one of the foremost persons

in the army of Gaza.

Mimmā yaqūlu nāsiḫuhā—ʿafā Llāh ʿanhu—annanī qaraʾtu akṯar hāḏihi

al-maqāmāt ʿalā muṣannifihā—raḥimahu Llāh—bi-qalʿat Ṣafat [sic]

al-maḥrūsa wa-huwa isbāsalāruhā fī šuhūr sanat sitt wa-ṯamānīn wa-

sittimiʾa ṯumma fāraqtuhu fī šahr ṣafar sanat sabʿ wa-ṯamānīn wa-sittimiʾa

wa-ẓalltu [sic] atawaqqaʿu ʿalā l-maqāmāt ilā an waqaʿtu bihā ʿinda wala-

dihi ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlī wa-huwa aḥad al-muqaddamīn bi-ḥalqat Ġazza.24

In contrast to al-Ṣafadī’s innovative collection, the al-Maqāmāt al-Qurašiyya is

composed of fifty maqāmāt and modeled closely on the Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī

(d. 516/1122). Notes in the margins of the manuscript identify the particular

maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī to which each of the maqāmat of Ibn al-ʿAttār are written

in imitation (muqābala).25 The first two maqāmas of this collection are both

modeled on the first maqāma of al-Ḥarīrī, and thus conform to the story that

was told by al-Ṣafadī that he had remembered other maqāmāt having been at

22 Ibn al-ʿAṭṭār, al-Maqāmāt al-Qurašiyya, MS Isyanbul, Aya Sofya, 4297, f. 1b.

23 Ibid., f. 219b.

24 Ibid.

25 For example f. 5a and f. 8b.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

640 Pomerantz

the beginning of the collection, for they do not contain either of the types of

maqāmāt described by the author. Only one of the maqāmāt, number forty

nine, al-Maqāma l-Uṣūliyya (f. 208a-215a) treating topics in ʿilm al-kalām and

philosophy, and uṣūl al-fiqh, is not modeled on the Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī.

4 Al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya: The Laleli Manuscript

The Laleli manuscript of the MǦ contains several indications of the circum-

stances and context of its initial reception. On ff. 1a and 1b, there are poems in

praise of the work (taqrīẓāt) from prominent individuals: Ǧamāl al-Dīn Āquš

al-Baysarī, Kamāl al-Dīn al-Ṣafadī, Nāṣir al-Dīn b. Ṣāḥib Šaraf.26 Āquš al-Baysarī

is identified in the manuscript as “one of the rulers of al-ḥalqa l-manṣūra in

Tripoli,” who was “one of the soldiers in Tripoli who composed poetry, amusing

anecdotes, and interesting stories” (wa-lahu šiʿr wa-mulaḥ wa-nawādir).27 Folio

1b contains a long poem in praise of the collection, written by “some of the

eminent rulers and gracious leaders” (baʿḍ al-ruʾasāʾ al-mutafaḍḍilīn wa-l-sāda

l-muḥsinīn).28

The Laleli manuscript lacks a colophon, but there is a note on the final folio

of the manuscript in the handwriting of the author which indicates the date

of the copy as 11 rabīʿ I 727/1327.29 Marginal notes indicate that the copy was

recited aloud in the presence of the author by Ibrāhīm al-Ǧazarī in two locations

in the city of Tripoli: the Mihmānḫāna Ṭarābulus and the Mosque of Qirān [?].30

5 Dedication to Abū l-Fidāʾ, Ruler of Hama (672/1273-732/1332)

There are several indications that this work was dedicated to the famed, Abū

l-Fidāʾ al-sulṭān al-Malik al-Muʾayyad, ruler of Hama (672/1273-732/1332).

In maqāma no. 1 (al-Ḥimṣiyya), Abū l-Fidāʾ is referred to as mawlānā l-sulṭān

26 Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 1a.

27 Id., Kitāb al-wāfī bil-wafayāt, ed. H. Ritter et al., Wiesbaden, Franz Steiner, 2004, IX,

p. 339-340.

28 Id., al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 1b.

29 See Rescher, “Manuscripte der Lālelī-moschee”, p. 104.

30 Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 23a [Mihmānḫāna]; f. 129b [Masǧid Qirān]. For the

ḫāns of Tripoli, see Hayat Salam-Liebich, The Architecture of the Mamluk City of Tripoli,

Cambridge, Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, 1983, p. 169-189; for a survey of the

mosques of the city, see Robert Saliba, Tripoli: The Old City, Beirut, American University in Beirut

Press, 1994. I have not been able to locate either the Mihmānḫāna or the Masǧid Qirān.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 641

al-Malik al-Muʾayyad ṣāḥib Ḥamāh.31 Maqāma no. 20 (al-Muʾayyadiyya) is a

panegyric addressed to Abū l-Fidāʾ in which both the narrator of the collection

and the trickster meet and address a variety of praise poems to him. In these

poems, he is referred to as “king of the kingdom of Hama” (malik al-mamlaka

l-Ḥamawiyya).32

The use of the title, sulṭān and al-Malik al-Muʾayyad both indicate that

al-Ṣafadī first composed the MǦ after Abū l-Fidāʾ officially received these titles

from al-Malik al-Nāṣir, i.e. post 17 muḥarram 720/28 February 1320.33 Indeed, in

maqāma no. 1 (al-Ḥimṣiyya ), the characters seek Abū l-Fidāʾ in Hama only to

learn that he is on a hunt in Egypt with al-Malik al-Nāṣir. This detail may be a

reference to Abū l-Fidāʾ’s visit to Egypt in the year 721/1321.34

6 Description of the Collection

The MǦ is comprised of thirty maqāmāt that describe the meetings of the nar-

rator Ṯāmir b. Zammām and the trickster character, Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī. The

names of the two characters rhyme with those of the two protagonists of the

Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī: Ḥāriṯ b. Hammām and Abū Zayd al-Sarūǧī. According

to Abū l-ʿAbbās al-Šarīšī (d. 620/1222), al-Ḥarīrī chose the names of Ḥāriṯ and

Hammām because, according to a ḥadīth of the Prophet, they were alleged

to be the most “truthful” of names. He explains that every man tills the earth

(yaḥriṯ) in search of acquiring wealth and worries on account of fulfilling his

needs (yahummu bi-ḥāǧatihi). As for Abū Zayd al-Sarūǧī, al-Šarīšī suggested

that the kunya was reference to the work of time and fate (dahr) while his

nisba al-Sarūǧī related to his old age and decrepitude.35 The names of the

characters in the MǦ, such as Ṯāmir b. Zammām (lit. sower son of the one

who bridles) is a meaningful variation on the meaning of Ḥāriṯ b. Hammām.

Similarly, Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī resembles Ḥarīrī’s Abū Zayd al-Sarūǧī, exchan

ging the notion of increase (zayd) for benefit ( fayd). The nisba al-Luǧūǧī both

31 Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 21a.

32 Ibid., f. 121a.

33 Enayatollah Reza and Farzin Negahban, “Abū al-Fidāʾ”, Encyclopaedia Islamica, 2012

(http://referenceworks.brillonline/entries/encylclopaedia-islamica/abu-al-fida-COM_

0065, accessed on April 1, 2012).

34 Abū l-Fidāʾ, al-Muḫtaṣar fī aḫbār al-bašar, Cairo, al-Maṭbaʿa l-ḥusayniyya, n.d., IV, p. 90.

35 Al-Šarīšī, Šarḥ maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī l-Baṣrī, Beirut, al-Maktaba l-ṯaqāfiyya, n.d., I, p. 27; the

relation of the nisba al-Sarūǧī to decrepitude and old age may be through the related

form, surǧaǧ, meaning long-lasting, perduring.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

642 Pomerantz

relates to his recalcitrance (luǧūǧihi) as well as a geographical connection to a

natural spring (nabʿ al-Luǧūǧ) near to the city of Baʿalbakk.36

The itineraries of the characters in the MǦ take place within the area of

Mamlūk rule between Egypt and Syria and roughly describe the borders of

state power and trade, albeit with some anomalous details. Of the maqāmāt

that are named after cities, thirteen are located in Syro-Palestine, four are set in

Egypt, three in the Arabian Peninsula, and three in Iraq. Several of the maqāma

settings such as Taʿizz, Mecca, and Qūṣ map out routes of Mamlūk Red Sea

trade, while the inclusion of Oman is difficult to explain. In the MǦ, the cha

racters visit the cities of Mosul, Tikrit and Baghdad which lay in the territory

of the Il-Ḫānids, possibly pointing to the existence of trade relations between

these two states.37 To the North, the city of Aḫlāṭ on Lake Van is the setting for

Maqāma no. 29; al-Ḫalāṭiyya features a discussion of the purchase of a slave

girl, which may relate to this city’s importance as way station on the route to

acquire slaves.

Building projects of al-Nāṣir Muḥammad figure prominently in this maqāma

collection.38 One maqāma, no. 25 (al-Muqtaraḥāt al-Nāṣiriyya ), lists the thirty

two mosques built by al-Nāṣir Muḥammad in Egypt and Syria and specifies the

large number of madrasas, ḫānqāhs and ribāṭs constructed during his reign.

Of particular note in this maqāma is the mention of the various hippodromes

(mayādīn) restored and reconstructed by al-Nāṣir Muḥammad, such as the

reconstruction of the Maydān al-Lūq completed in 714/1314, and the al-Maydān

al-Nāṣirī, begun in the same year.39

Although important cities are the settings for the majority of the māqāmāt,

the author of the MǦ also expresses interest in smaller towns and villages as

well. Maqāma no. 12 (al-Damālāṣiyya) begins in the small village of Damāṣ, in

the Eastern Egyptian delta describing the trade in linen, (kattān), which mer-

chants sold in Dalāṣ a city near Banū Suwayf in Upper Egypt.40

36 Ibn Faḍl Allāh al-ʿUmarī, Masālik al-Abṣār fī mamālik al-amṣār, ed. F. Sezgin, Frankfurt,

Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science, 1988, III, p. 267, notes the location of

this spring.

37 Reuven Amitai, “Il-Khanids: Dynastic History”, Encyclopaedia Iranica. My thanks to Dr.

John Meloy of American University in Beirut for suggesting this possibility.

38 On al-Nāṣir’s extensive construction programs, see Amalia Levanoni, A Turning Point in

Mamluk History: The Third Reign of al-Nāṣir Muḥammad Ibn Qalāwūn 1310-1341, Leiden,

Brill, 1995, p. 156-173.

39 Ibid., p. 158-160. The absence of mention of the large projects of Siryāqūs built in 723/1323

is evidence for a terminus ante quem for the collection.

40 Yāqūt, Muʿǧam al-buldān, II, p. 459.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 643

Historical events are also important to the texture of the MǦ. In Maqāma

no. 8 (al-Maʿarriyya), the narrator, Ṯāmir b. Zammām first goes to the city

of Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān, where he mourns the ruins of that city’s citadel and

the flight of the city’s inhabitants that began with the first siege of the city in

492/1098. Similarly, in Maqāma no. 9 (al-Tīzīniyya), the narrator describes his

visit to the cities of Antioch (Anṭākiyya) and Latakia (Lāḏiqiyya) where he is

lost in lament over the fates of the inhabitants of these locales. While he is in

the midst of this thought, a voice (lisān al-ḥāl) addresses him and describes

the advance of the army of al-Malik al-Ẓāhir Baybars I that lay siege to Antioch

in 665/1268.41 The text vividly describes how the Mamlūk army, “destroyed the

foundations of their churches, killed their priests and monks”(fa-hadamū min

kanāʾisihimā l-arkān wa-qatalū qasāqisahimā wa-l-ruhbān) and tells of how the

Mamluk army removed the crosses and idols from the Christian buildings, cap-

tured great numbers of women and children, and took spoils from the city.42

7 Narrative Structures

Most of the maqāmāt in the MǦ exhibit a common structure. On the whole,

they conform to the main scheme found in the Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī (follow-

ing Hämeen-Anttila):43

1. isnād,

2. general introduction,

—link,

3. episode,

4. recognition scene,

5. envoi,

6. finale.

The poetic envoi of the trickster is a very common motif in the collection, pre

sent in more than half of its maqāmāt.

The MǦ collection is remarkable for its wide range of styles of different

maqāmāt treating a diversity of different topics. Some maqāmāt in the col-

lection resemble those found in other collections such as no. 1 (al-Ḥimṣiyya)

resembles the first maqāma in the collection of the Maqāmāt of Aḥmad b. Abī

41 G. Wiet, “Baybars I”, EI2.

42 Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 62a.

43 Hämeen-Anttila, Maqama, p. 152.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

644 Pomerantz

Bakr b. Aḥmad al-Rāzī l-Ḥanafī, in that it treats poems in which each of the

words contain the same letter.44 While maqāma no. 19 (al-Ṭuyūriyya) seems

to be a symbolic allegory using the figures of birds along symbolic lines simi-

lar to al-Suyūṭī’s Maqāmat al-Rayāḥīn.45 Maqāma no. 26 (al-Ḥarrāniyya), in its

description of banquets and food, references the long-standing relationship

between gastronomy and maqāmāt.46

Many of the individual maqāmāt in the MǦ deal with unusual topics that

lend great interest to the entire collection. Maqāma no. 16 (al-Miyāhiyya)

describes how the narrator first observed the various weights of bodies of

water in Mamlūk Egypt and then learned of the magical properties of various

water sources in ways that suggestively juxtapose the act of scientific observa-

tion to the contemplation of the mysterious (ʿaǧāʾib). Similarly, Maqāma no. 7

(al-Taʿbīriyya l-Dimyāṭiyya), treats the topic of dream interpretation. The final

Maqāma that survives from the MǦ, no. 30 (al-Faraǧ baʿd al-šidda), weaves

together several stories of miraculous escape, along the lines of those found

in al-Tanūḫī’s (d. 327/939-384/994) famed work of the same name.47 Taken

as a whole, the collection tends to highlight the great diversity of knowledge

brought together by its author.

Throughout the work, al-Ṣafadī also employs a wide variety of poetic

forms. For example, Maqāma no. 1 (al-Ḥimṣiyya) showcases one long poem in

which each bayt of the twenty nine-line poem is devoted to a particular let-

ter of the alphabet, in which all of the words of the bayt contains the same

letter. Following this poem, there is a series of twenty nine five-line love

poems in which each word again contains the same letter of the alphabet, and

each bayt begins and ends with the same letter.48 Similarly, in Maqāma no. 1

(al-Ḥimsiyya), there is an example of tašǧīr, a praise poem that is written in

the shape of a tree, in which each of the branches completes the same verse of

poetry in different manners.49

44 Devin J. Stewart, “The Maqāmāt of Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr b. Aḥmad al-Rāzī al-Ḥanafī and the

Ideology of the Counter-Crusade in Twelfth-century Syria”, Middle Eastern Literatures, 11

(2008), p. 211-230.

45 Al-Suyūṭī, Maqāmāt al-Suyūṭī, ed. S. al-Durūbī, Beirut, Muʾassasat al-risāla, 1989, I, p. 431.

46 See for instance, Ibrahim Ḫ. Geries, A Literary and Gastronomical Conceit, Wiesbaden,

Harrassowitz, 2002.

47 Al-Ṣafadī, al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya, f. 176b and following.

48 Bakrī Šayḫ Amīn, Muṭālaʿāt fī l-šiʿr al-mamlūkī wa-l-ʿuṯmānī, Beirut, Dār al-ʿilm li-l-

malāyīn, 1986, p. 222.

49 Amīn, Muṭālaʿāt fī l-šiʿr, p. 182, incorrectly states that this style of poetry was not known

prior to the 11th/17th century; for an example, see p. 656.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 645

It is, however, in the area of popular poetry that the MǦ is particularly inte

resting. In the Maqāma no. 28 (al-Qūṣiyya), there is a long discussion on vari-

ous types of poetry: al-muḫammas, al-muraṣṣaʿ, al-muraǧǧaz, al-mawāliyyā,

al-dūbayt, kān wa-kān, al-ḫabab, al-ḥammāq, and the various regions famed for

particular forms. Al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī was an older contemporary of the poet, Ṣafī

l-Dīn al-Ḥillī (d. 750/1349) who authored the ʿĀṭil al-ḥālī wa-l-muraḫḫaṣ al-ġālī,

recently described as the first “poetics of Arabic dialect poetry.”50 Al-Ḥillī

wrote the work “some time after 723/1323” i.e. at roughly the same time as the

MǦ. Since the two poets were both attached to the circles of al-Malik al-Nāṣir

and Abū l-Fidāʾ, the account of al-Ṣafadī may provide important further mate-

rial for contextualizing al-Ḥillī’s work.

8 Contents of the Collection

8.1 al-Ḥimṣiyya (ff. 2a-23a)

The narrator, Ṯāmir b. Zammām, after wandering alone in a starless night

arrives in the city of Homs. He passes through the city and asks in the market

who is the most talented of the city’s men of letters. He finally meets a teacher

who has a large number of pupils gathered around him. A young boy, who is

dressed as if he was from the awlād al-nās but has fallen on hard times, is the

first to speak. He recites an alphabetical poem of twenty seven verses in which

every word of each successive verse contains a particular letter of the alphabet

(i.e. every word in verse 1 of the poem is written with an alif, every word in verse

2 of the poem is written with a bāʾ and so forth). When he completes this poem,

the teacher calls on other young men, who, each take turns reciting five-line

poems in which every word contains a particular letter of the alphabet. After

traversing the entire alphabet, the teacher calls upon a Christian boy, named

Ibn Šammās, to recite a poem. When he completes his recitation, the teacher

and Ibn Šammās debate and argue about the relative merits of their verses

until a man dressed in blue arrives on a horse. Having heard the cause of their

discord, the horseman suggests that the only person capable of settling their

disputes is the sulṭān al-Malik al-Muʾayyad, Abū l-Fidāʾ. He then recites a poem

of praise for Abū l-Fidāʾ. Seeking a resolution, the three men hasten to his court

in Hama, however upon arriving, they learn that Abū l-Fidāʾ has gone hunting

50 Margaret Larkin, “Popular Poetry in Post-Classical, Period 1150-1850”, in The Cambridge

History of Arabic Literature: Arabic Literature in the Post-Classical Period, p. 191-242, quote

on p. 202. See Ṣafī l-Dīn al-Ḥillī, ʿĀṭil al-ḥālī wa-l-muraḫḫaṣ al-ġālī, ed. Ḥusayn Naṣṣār,

Cairo, Maṭbaʿat dār al-kutub, 2003.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

646 Pomerantz

in Egypt with the sulṭān al-Malik al-Nāṣir. They then head to Egypt, where they

find Abū l-Fidāʾ. The narrator follows them and learns that the entire plot was

an elaborate hoax: the three men are staying in a inn (bayt funduq) near Bāb

al-Lūq in Cairo where they meet up with the horseman. Ṯāmir recognizes the

horseman as the trickster, Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī and the teacher and the boy turn

out to be his sons, al-Surayǧī and al-Sarūǧī.

8.2 al-Taʿizziyya (ff. 23a-26b)

The narrator, Ṯāmir, describes how he departed from Cairo, and crossed the

desert, accompanied by a group of excellent scholars who were passing the

time by engaging in edifying conversation. When the group reaches a settle-

ment in the desert, they desire food. They immediately come upon a šayḫ,

dressed in a cloak of camel hair and a young man. The šayḫ welcomes the

group to his home. They display their prowess in literature, and he invites them

to a meal. Following the meal, the šayḫ leads a discussion, asking specific ques-

tions about the Qurʾān which none of the travelers are capable of answering.

A young man, however, speaks up and responds to the šayḫ. Speaking in verse,

the young man relates such details as the number of Meccan and Medinan

verses, the number of verses of prostration, the number of verses concerning

“promise and threat” and so on. When he concludes this long answer, the šayḫ

asks the youth to enumerate the number of times dotted and un-dotted letters

occur in the Qurʾān. When the young man answers correctly, the onlookers are

astonished by his knowledge and eloquence. Ṯāmir decides to follow the two

men and learns that the šayḫ is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī, and the young man is his

son, al-Surayǧī.

8.3 al-Dimašqiyya (ff. 26b-31a)

Ṯāmir describes his poverty and his flight from his home, escaping from his

creditors. While on the road he meets up with some travelers, who, impressed

with his eloquence, offer him fine clothes and a mount. Arriving in Damascus,

Ṯāmir visits the Umayyad mosque, where he sees one particular šayḫ who is

surrounded by a large audience. The šayḫ discusses God’s command and will

(al-amr wa-l-irāda) and then recounts differences between the four schools

of Islamic law. Concluding his lecture, he poses riddles which confound the

audience, save for a youth who solves his puzzles in both prose and in verse.

The šayḫ and youth continue to perform in this manner, until the audience

offers the youth a monetary reward. After this impressive display, Ṯāmir fol-

lows the šayḫ and the youth to their home and discovers that the šayḫ is Abū

Fayd al-Luǧūǧī, and the youth is his son, al-Surayǧī.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 647

8.4 al-Qadasiyya (ff. 31a-43b)

Ṯāmir b. Zammām states that he was traveling in the mountains of Jerusalem

(bayt al-maqdis) in solitude, attempting to purify himself from sin, when he

encountered a Muslim šayḫ and Christian monk (rāhib) engaging in a reli-

gious debate. He witnesses a Muslim challenging the Christian, stating that he

has wasted most of his life in the practice of a religion that was unbelief. The

Muslim quotes numerous passages from the Qurʾān proving the rectitude of

Islam, until finally, the monk converts. The monk passes away, however, only

three days after his conversion. Upon burying the monk, Ṯāmir discovers that

the Muslim šayḫ is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.5 al-Ṣād Sīniyya (ff. 43b-48b)

Ṯāmir b. Zammām goes to a bathhouse at night where he meets a šayḫ around

whom a large group of men are gathered. The šayḫ raises the topic of diffe

rences in meanings between words written with the letter ṣād as opposed to

sīn, and ġayn as opposed to rāʾ. A youth answers the old man’s questions in

great detail providing a list of such words. The two men are then rewarded by

the other men at the bath for their eloquence. Ṯāmir follows them outside of

the bathhouse, and learns that the pair is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī and his son.

8.6 al-Mawṣiliyya (ff. 48b-52b)

The narrator finds himself in Mosul amidst a group of merchants. He meets a

šayḫ there who narrates the story of his life steeped in the vanities of the world

and his subsequent reform, after which he encourages the audience to reward

him for his eloquence. After the šayḫ recites a kān wa-kān that moves the nar-

rator, he follows the šayḫ and learns that he is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.7 al-Taʿbīriyya al-Dimyāṭiyya (ff. 52b-58a)

The narrator sets out on a boat with a group of travelers heading to Damietta.

While aboard, a youth asks a šayḫ to inform the group about the science of

dream interpretation (ʿilm al-taʿbīr) and he provides a long informative speech.

They reward him with gifts upon their safe arrival on shore. The narrator recog-

nizes the youth and šayḫ as Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī and his son, ʿUbayd al-Surayǧī.

8.8 al-Maʿarriyya (ff. 58a-62a)

The narrator arrives in Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān and laments the destruction of the

city. He then visits the tomb of Yūšaʿ b. Nūn where he sees people from the city

listening to a preacher. The preacher delivers a ḫuṭba lacking dots and a long

poem concerning moral behavior. Moved by the preacher’s performance, the

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

648 Pomerantz

audience offers him money. The narrator follows him to his home and disco

vers that he is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.9 al-Tīzīniyya (ff. 62a-65a)

The narrator visits the cities of Anṭākiyya and Lāḏiqiyya and mourns the

destruction of these cities by the Mamlūk armies. He then travels to the village

of Tīzīn, near the city of Hama, where he listens to an eloquent šayḫ preaching.

He so moves the audience with his words that they offer him material rewards.

Upon following the šayḫ, he discovers that it is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.10 al-Ḥalabiyya (ff. 65a-68a)

The narrator travels to the city of Aleppo, where he enters a hospital. He is then

treated by a doctor from his illness which is described as having been caused

by his profligate lifestyle. Cured by the doctors, he visits the markets and the

area beneath the city’s citadel (qalʿa). There, he comes upon a display of a šayḫ

and a youth engaging in a contest of paranomastic expressions, in which one

deciphers the speech of the other. Ṯāmir finally discovers that the pair are Abū

Fayd al-Luǧūǧī and his son.

8.11 al-Baġdādiyya (ff. 68a-75a)

The narrator visits the city of Baghdad and explores the city. He joins a group

of people listening to a šayḫ preaching to a youth. The šayḫ accuses the youth

of disloyalty, while the youth pleads his innocence by swearing oaths of loyalty.

The audience attempts to intercede on the youth’s behalf by offering money to

the šayḫ, which he accepts. The šayḫ and youth then head to another location,

where another group gathers around the šayḫ, impressed by his mastery of

paranomasia (ǧinās). They encourage him to relate stories concerning the ages

of those men who have lived long lives (muʿammarūn), among other topics.

His student then recites a list of the originators (awāʾil) of various arts and sci-

ences. The audience rewards them both, and the narrator learns that they are

Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī and his son.

8.12 al-Damālāṣiyya (ff. 75a-78a)

The narrator is traveling with a group of linen merchants from Damāṣ, in the

eastern delta, to Dalāṣ, a village near Banī Suwayf in Egypt. When the group is

preparing to leave, a šayḫ warns them of the potential evils of trade. The nar-

rator meets with the šayḫ, whom he discovers to be Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī and

addresses a poem to him.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 649

8.13 al-Nābulusiyya (ff. 78a-83a)

The narrator is traveling with a group of young men when he encounters a

group of young slave girls by a spring. One of the girls recounts that she had

been the daughter of a king, but was taken captive when her city was sacked.

The narrator, however, hears a voice which tells him to repent of his own sins.

He then leaves Nablus and travels until he reaches a mosque, whereupon he

meets a šayḫ. The šayḫ is confronted by a young man completely bare, save

a wrap made of camel wool, who asks him about the reason that man wor-

shipped fire and idols prior to Islam. The šayḫ then answers with a history of

fire and idol worship composed in muzdawaǧ verse. This proves so eloquent

that the audience showers him with gold and silver, which is collected by the

young boy. When the narrator discovers the pair to be Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī and

his son, the former recites a poem on the theme of the disappearance of for-

mer rulers and peoples.

8.14 al-Sarūǧiyya (ff. 83a-86a)

The narrator sets out from Baghdad in a caravan in which there is a beautiful

woman whom he describes in verse. He then comes across a group of travel-

ers from Aleppo whom he accompanies to Sarūǧ, whereupon he sees a group

gathered around a šayḫ reciting a riddle (luġz) to a young man in verse, the

young man answers him, astonishing the onlookers who offer them both

rewards. When the narrator confronts the šayḫ, the šayḫ recites to him a

muwaššaḥa that delights him.

8.15 al-Lubnāniyya (ff. 86a-90a)

The narrator sets out after feeling distressed on a long journey where he ends

up on the Ǧabal Lubnān and falls asleep under a tree. When he awakes, he

is surrounded by a group of the poor men, and some sons of amīrs who ask

him the reason for his arrival in this location. The group then prays together,

and a šayḫ appears. The group of men then ask the šayḫ to explain the diffe-

rence between al-rūḥ and al-nafs. Following the šayḫ, who is accompanied by

a young boy, the narrator discovers that the šayḫ is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī, who

recites a poem to him, encouraging his repentance. The narrator is moved by

this poem, which is followed by another poem by his son.

8.16 al-Miyāhiyya (ff. 90a-97b)

The narrator states that when he was in Syria he began to think about water,

so one day he went to the Orontes river. He bent down and touched and tasted

its waters, and then weighed a measure of it on a scale. When he went to Egypt

he did the same with the Nile river. He then did the same at the Euphrates,

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

650 Pomerantz

the Luǧūǧ spring in Baʿlabakk as well as water sources in Aleppo, in Tripoli,

in Nablus, and in Damascus. The narrator then goes to Cairo where he comes

across a šayḫ mentioning the wonders of water. The šayḫ recites a poem

describing the flooding of the Nile, Baḥr Yūsuf in the Fayyūm, Dayr Arǧinus

[Dayr Ǧarnūs], the Hijaz, ʿUyūn al-Qāṣab (a location on the ḥaǧǧ route from

Egypt), ʿAyn al-Silwān in Jerusalem, a cave in the Ǧabal ʿĀmil, a hot spring

in Tiberias, a cold stream in Baʿlabakk, the course of the Orontes river, the

waterwheels at Homs and Hama, the Sāǧūr River, the course of the Euphrates,

the mineral spring of Raʾs al-ʿAyn, and other wonders related to water. After

being recognized by the narrator, the šayḫ, Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī, recites a poem

encouraging repentance.

8.17 al-Iskandarāniyya (ff. 97b-102b)

The narrator begins questioning many aspects of his existence. He recites a

poem beseeching the Prophet Muḥammad for aid. After this, he encounters

a šayḫ who accompanies him to Alexandria. The two men pray, and the šayḫ

recites a muwaššaḥa in praise of the Prophet. The audience is moved by the

eloquence of his words and offer him money, however the narrator follows him

and discovers that he is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.18 al-Ḥamawiyya (ff. 102b-110a)

The narrator is in the outskirts of Homs near the water wheel (nāʿūra) enjoy-

ing worldly pleasures of wine, women, and song, when suddenly an unspeci-

fied act causes him to leave the group and set out on his own. He travels to

Hama where he meets a šayḫ who counsels him to lead a more pious life. The

šayḫ then gives several long metaphorical descriptions of piety using terms

derived from medicine, chancery, and the military arts. The audience moved

by his eloquence rewards him and the narrator learns that the šayḫ is Abū Fayd

al-Luǧūǧī.

8.19 al-Ṭuyūriyya (ff. 110a-118a)

The narrator is among a group of men of different ages (šayḫ, kahl, šābb) and

characteristics (amrad, ḫādim) and composes verses. The verses liken each of

the individuals who are each holding bows, to different planets (šayḫ=Jupiter,

kahl=Mars, šābb=Mercury, amrad=Moon, ḫādim= Saturn). At this point, the

narrator notices a šayḫ to speak to them about the importance of archery. He

recites an urǧūza concerning hunting. The poem includes a description of vari-

ous birds, as well as accompanying illustrations. When the šayḫ concludes, the

narrator recognizes him to be Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 651

8.20 al-Muʾayyadiyya (ff. 118a-126b)

The narrator begins with the conventional theme lamenting the loss of lite

rary cultivation in his time which forces him to set out on travels. He describes

his delight at learning of the presence of Abū l-Fidāʾ as the ruler of Hama. He

recites an urǧūza in praise of Abū l-Fidāʾ when he comes across a šayḫ as he

is in the Ġūṭa outside of Damascus. This šayḫ responds with a mawāliyyā, a

dūbayt mardūf, a muwaššaḥ, and a kān wa-kān of his own in praise of Abū

l-Fidāʾ. The two men then seek out the ruler, who is first in Egypt, and then

returns to Hama, where the two men finally reach him. The narrator finally

identifies the šayḫ as Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.21 al-ʿAsqalāniyya (ff. 126b-130b)

The narrator falls in among a group of thieves who are attempting to rob the

home of the ruler (wālī), but they are apprehended by a group of guards. The

narrator escapes from this scene only to find himself on the shore amidst

a group of anxious merchants who are about to board boats, and when the

weather changes, heads to ʿAsqalān. When they arrive in the city, they meet a

šayḫ, who tells them that he once was a wealthy man. He describes how he was

once on a boat, and the waves overtook it, and everyone on it, except for him,

drowned. He lived for a while by foraging for food, until one day, miraculously

he was saved and brought to this city. When they hear the tale of this man, the

audience is moved to generosity. Ṯāmir b. Zammām then follows him and dis-

covers that he is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.22 al-Ǧārraḥiyya (ff. 130b-141b)

Ṯāmir b. Zammām meets a šayḫ in a garden who recites a poem about spring-

time. The poem astonishes Ṯāmir and upon closer inspection he recognizes

that the poet is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī. As the two men are talking, suddenly, a

troop of horsemen surrounds them, and the two are taken to see the ruler of

the territory. They are informed that the king loves to hunt, however his favorite

hunting birds have fallen ill, and for this reason he is upset. Abū Fayd informs

the ruler that he is knowledgeable about the treatment of hawks. The king asks

Abū Fayd for a description of the types of birds of prey.51 The king questions

Abū Fayd which animals’ flesh is licit to consume.52 Abū Fayd then continues

51 F. 132b is identical to al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī, al-Āṯār al-uwal, p. 262-263.

52 F. 133a is identical to al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī, al-Āṯār al-uwal, p. 265-266, lacking the final ḥadīṯ

on p. 266 related on the authority of al-Nasāʾī.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

652 Pomerantz

to speak about hunting and kingship,53 and to describe various animals used

in the hunt,54 and recites a poem on hunting dogs. The final section concerns

birds of prey (ǧawāriḥ min al-ṭayr), advice concerning hunting,55 and the ill-

nesses that befall birds of prey.56 At the conclusion of the speech, the king asks

Abū Fayd to remain at his court, however, Abū Fayd complains of having to

return to his children. The king generously rewards him with a cloak of honor

and gold and silver. The narrator and Abū Fayd leave together, and the narrator

asks him to share some of his wealth, Abū Fayd tells him to accompany him to

al-Luǧūǧ, whereupon he recites a poem in which he refuses to share any of his

wealth with the narrator. The two men part company.

8.23 al-ʿUmāniyya (ff. 141b-147b)

Ṯāmir b. Zammām leaves the city of Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān and finds himself tra

veling among a group of merchants (tuǧǧār) who are entertaining one another

through the recitation of poetry. The group eventually reaches Oman, where

they search for wise and learned men. Ṯāmir visits the central mosque where-

upon he sees a šayḫ reciting a poem surrounded by a large group of students.

A youth then emerges who asks the šayḫ questions, such as the number of

breaths a person takes in the course of a day and a night, the size of the sun,

and how many stars there are in the sky. The šayḫ answers these questions in

verse. Astonished by the display, the onlookers offer both money. Still curious,

the narrator follows the pair whereupon he discovers that they are Abū Fayd

al-Luǧūǧī and his son. The narrator tells Abū Fayd that he has not given an

answer about the number of stars in the sky. Abū Fayd replies that every calcu-

lation in astrology is made for the sake of gaining money from the ignorant. He

then encourages him consider writing a risāla on astrology.

8.24 al-Makkiyya (ff. 147b-149b)

The narrator mentions sins he committed as a youth. He describes how he tra

veled to Mecca on the hajj in order to repent of his transgressions. When he

arrives in Mecca, he meets a šayḫ who appears to sense the sincerity of his

repentance and accompanies him. On the return trip, the narrator suddenly

53 F. 133a-b is drawn from al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī, al-Āṯār al-uwal, p. 267-268.

54 FF. 133b-134b are identical to Ṣafadī l-Barīdī, al-Āṯār al-uwal, p. 270-271 with several altera-

tions and additions. See esp. the poem on the leopard (fahd), p. 271, which is altered and

expanded from 2 verses to 7 on f. 134b.

55 FF. 135b-136a is drawn from al-Ṣafadī l-Barīdī, al-Āṯār al-uwal, p. 275 and following.

56 F. 139b.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 653

falls asleep. When he awakes, the caravan in which he was traveling has disap-

peared. In the midst of his confusion, the šayḫ appears to him again, and recog-

nizes him as the narrator, Ṯāmir b. Zammām. The šayḫ tells Ṯāmir that he will be

saved on the condition that he goes to his neighbor and takes his white rooster

with a blue comb, roasts it, and then eats it. Ṯāmir is then returned to his cara-

van and tells his friend nothing of this strange encounter. Returning to his vil-

lage, he visits his neighbor’s home, in order to take the rooster. As he is about to

eat the rooster, someone screams that the daughter of the house has been kid-

napped, and he is blamed. The narrator travels on the hajj a second time. When

he arrives to the same place where the šayḫ appeared to him before, he sees

the neighbor’s daughter there with another man. The man informs the narra-

tor that he loved the young woman, however the rooster prevented them from

meeting one another. When the narrator killed the rooster, it became possible

for them to meet. The man then asks the narrator to recite verses from Kor 85,

and upon hearing them, he disappears. The narrator returns to his home with

the young woman. The narrator then visits the neighbor and he forgives him.

The narrator states that the story had remained in his heart until he revealed it

to the trickster, Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī at the Umayyad mosque.

8.25 al-Muqtaraḥāt al-Nāṣiriyya (ff. 149b-153a)

Ṯāmir describes how he has wandered all over the earth and has seen the

monuments of every ruler prior to his arrival in Cairo. He meets a man who

leads him to the area of Bayn al-Qaṣrayn. There he sees a šayḫ preaching who

begins to applaud the wonderful architectural works of al-Malik al-Nāṣir and

his contemporaries, listing each of these monuments by name first in Cairo,

then in al-Šām. He then lists all of the schools (madrasas), lodges (ḫānqāhs)

and a hospital (bīmāristān) founded in the days of al-Nāṣir as well as those

buildings which were renovated. He describes the īwān constructed by al-Nāsir,

the maydāns, such as Maydān al-Lūq in which he planted trees from al-Šām,

his construction of the horse market, the tower of happiness (Burǧ al-saʿāda). He

finally recites several long poems in praise of al-Nāṣir and his building projects.

Ṯāmir then follows the šayḫ, and discovers that he is Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.26 al-Ḥarrāniyya (ff. 153a-162b)

Ṯāmir recounts how after some misfortune, he arrived in the city of Ḥarrān.

As he is wandering the streets in a state of despair, poverty and hunger, he

sees a large group of men invited to a feast and follows them. A šayḫ emerges

who addresses the audience “on behalf” of the host, named Zayn al-Dīn, in a

pompous fashion. When Zayn al-Dīn asks the šayḫ to be quiet in private, the

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

654 Pomerantz

guest says that the host has just given him the task to describe the foods at

the banquet. The guest then proceeds to recite a list of euphemistic expres-

sions for the various foods in a long speech. When he concludes, Zayn al-Dīn

is even angrier, slaps the šayḫ, and orders him to leave the house at once. The

šayḫ then leaves and walks to the house of a qāḍī whom he promptly invites

to the banquet along with the legal witnesses, scribes, and other functiona

ries. The group of 180 men arrive at Zayn al-Dīn’s home, and he realizes to

his great embarrassment that he does not have enough food, and orders his

servants to get more from the market. Meanwhile, Zayn al-Dīn again sends

the guest him from his home. The guest then goes to the home of the ruler

of the city (wālī l-madīna) and the same scene is replicated once again. Zayn

al-Dīn finally asks the reason for the šayḫ’s behavior and the šayḫ explains

that it was the man’s initial refusal to let him speak which drove him to these

actions. Finally Ṯāmir follows the guest home and discovers that he is Abū

Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.27 al-Takrītiyya (ff. 162b-168a)

Ṯāmir describes how he traveled in a group to Tikrit seeking literary know

ledge. He describes how the city of Tikrit had been ravaged by war. He then

states that he went to the main mosque of the city where he listened to a

šayḫ enumerating qualities which should be prohibited for a man, and quali-

ties that should be fostered. After this, a young man stands up and praises the

šayḫ, making an invocation (duʿāʾ). He then asks the šayḫ to recite a ḫuṭba in

which one word is made up of letters that are dotted and the following entirely

lacking in dots, which he does. The šayḫ continues by pronouncing a blessing

(taḥmīd) completely lacking in dotted letters. Ṯāmir reports how a scribe at

the ruler’s court learned of šayḫ’s eloquence and the ṣāḥib dīwān invites him

to the court. He recites a poem. However, the ṣāḥib does not immediately pro-

vide the šayḫ with a gift. The šayḫ, who is revealed to be Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī,

persists until he receives his reward.

8.28 al-Qūṣiyya (ff. 168a-173b)

Ṯāmir states that he has been occupied with seeking knowledge for a long time.

While he is in the midst of this search, he hears that an excellent preacher lives

in the city of Qūṣ in Upper Egypt. Thus, he decides to travel up the Nile on a

boat (šaḫtūr). On the way, he listens to the captain speaking in sailor’s argot.

Upon arriving in Qūṣ, Ṯāmir disembarks to find the šayḫ whom he had sought

out. After finding the šayḫ and listening to him, a boy from the audience asks

the šayḫ to lecture on adab. The šayḫ provides a comprehensive account of

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 655

various types of Classical and colloquial poetry. When they hear the excellence

of his speech the audience showers him with gold and silver. Ṯāmir then fol-

lows the preacher as he leaves the scene, and learns that he is also the chief

sailor. In the final envoi, the captain/preacher reveals that he is none other

than the trickster Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī.

8.29 al-Ḫalāṭiyya (ff. 173b-177b)

Ṯāmir relates how he became enamored with singing girls while he was in the

city of Aḫlāṭ. Soon, he sees a young woman with whom he falls in love and

desires to find out whether she is a free woman or a slave. He learns that she

is a free woman from one of the wet nurses of the city. He then confesses that

he does not have adequate money to pay the bride price. A wet nurse agrees

to invite him to see the singing girl, and at a nightly gathering she performs

music for him with such elegance that he falls even more deeply in love. In the

midst of his rapture, however, a man comes in with a scale and demands him

to pay 20 dīnārs for the wine and other accoutrements of the evening perfor-

mance. He pays money to this man, and stays until the call to prayer sounds

as he agreed with the man leaving from the girl without achieving his “aim.”

He returns night after night until he is destitute. He then wanders the streets

until he comes across a šayḫ. The šayḫ recites a poem in which he describes the

many other men who had been deceived by the same singing girl. Moreover, he

learns that the man who performed the call to prayer was, in fact, being paid

by the singing girl. In despair, Ṯāmir then goes to the Ǧazīra where he is in a

mosque, after falling asleep he meets a šayḫ who attempts to discuss Shiʿite

thought with him. He states that he is a Sunnī. Finally, Abū Fayd al-Luǧūǧī

appears and recites a poem in favor of Sunnism.

8.30 al-Faraǧ baʿd al-šidda (ff. 177b-179b)

Ṯāmir recounts how he once was traveling on a very hot day through the desert.

While he was lost in thought, a ferocious lion appears in his path. Fearing for

his life, Ṯāmir flees to a nearby cave and the lion follows him such that he is

situated right outside of the cave opening. The lion attacks but is not able to

reach Ṯāmir. However, when Ṯāmir turns toward the opening of the cave he

sees two gigantic snakes that are carrying a hydra (šuǧāʿ). The hydra wraps

himself around the body of Ṯāmir, but instead of killing him, it bites the lion

instead. The hydra then kills the lion and then mounts the two snakes and

leaves. Shaken, but unharmed, Ṯāmir manages to escape to a city after a jour-

ney of two days. Wandering through the ruins of the city, he encounters a dying

man, whose wounds accidentally spray him with blood. He is then arrested

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

656 Pomerantz

for the murder of the man. He is only saved from execution by the miraculous

story of his escape delivered in verse, for which he is handsomely rewarded.

al-Maqāmāt al-Ǧalāliyya MS Istanbul, Laleli, 1929, f. 20b

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 657

9 Text of al-Maqāma al-Tīzīniyya

اسعة تُ ْع َر ُف بال ِت ّ ِزي ِينيَّة قامة الت ّ ُ ا َمل ُ

زمامٍ: ِ

قال ثام ُر بن ّ َ

س دت ِم َن اجلُال ِ اس َوان ْ َف َر ُ كُنْ ُت يف غالِ ِب أوقاتي ُأغالِب ُخرافاتي وقَ ْد انْع َزل ْ ُت ع ِن النّ ِ

ّ َ َ َ ُ ْ

ينت ِ َ ٍ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ

قيم مبد َ رب الربيّة على كُ ّل أ ْمر وقضيّة وأنا ُم ٌ واستَعنْ ُت ب ّ وقَ َن ْع ُت ب ُص ْح َبة اجلَالّس ْ

قد ِر ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ

باكية لا َح َّل ب ِهم م َن األم ِر امل ُ َّ ٌوع ُيوني ٌ ود ُموعي على أهليهما واكفة ُ الالّذقيّة وأنطاكية ُ 5

حال ْم حالم وما كانوا عليه وافْتكرت كَثة أو ِ ِ الكا ِئن واخلطَر املُسطَّ ِر احلائِ ِن َفف َّكرت يف ِ ِ

ُ ْ َ ْ ْ ُ َ َ

لقال: لقيل وا ِ يان ا ِ سان ِ وكُفْ ِر ِهم وما ركَنوا إليه فجاوبين لِ

وخاطبين بَ ُ َ احلال ُ َ َ ْ َ

ِ احلر ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ َ

وحادثات مان أيُّها امل ُ َف ّك ُر يف تقلُّبات األيّا ِم ون َ َكبات ا َأل ْعوا ِم َو َغ َدرات ا ّلزمان ُوم ْو َجبات ْ

ِ ِ ٍ ٍ ِ ِ

وج ٍال وج ٍال َ َ حاب هذه املَديْنتني َأ ْرباب ن ْعمة بَديْنة وز ٍين َ َ

اللّيايل ونائبات التَّوايل قَ ْد كانوا أ ْص ُ

وش ْه ٍو و َأ َر ٍب َو َغفْ ٍلة وأحوال َوم َر ٍح َو َف َر ٍح وهل ْ ٍو وط ََر ٍب َ وخ ُيول وبغال ومواشي ْ

وأموال ُ ٍ ِ ٍ ٍ ٍ

ومال 10

س ور ٍ ِ ئس ُ ٍ وع ٍ ُغيان وتفن ٍد ِ وحيلة وهل َ ٍع ومتر ٍد وط ٍ ٍ

هبان وقد وصلبان وقَ َسائ ٍ ُ صيان وكنا ٍ ُّ ُّ َ َوول ٍع

تني َو َص َّر َف ُهم يف َأ ْر ِض ِه َو َأ ْو َس َع هلم ِس َعتَ ْ ِي َفل َ َّما َج َح ُدوها عمة نِعم ِ

َْ

أنعم اهلل عليهم فو َق ا ِلن ِ

َْ ّ َْ َ ُ

األحدي ّ ِة ِ

املأجورة ْ َ

ِ

احملمديّة وا ّلدساك َر ُ ّ ورة ص ُ ْ نَ امل ر ط علَيهم ا ِ

لعساك َ َ ل وس

َ يْ ع

َ فة َر

ْ ط يف بوها سِ

ل ُ

ومساء ُهما ْأر ًضا وطُوهلُما وقاطنهما ِ

جافل َ ُهما سافلَهما ِ ِ ِ ِِ ِ

َ ُ يف ا َّلد ْولة الظّاهري ّة َف َج َعلُوا عاليهما ُ

نامهما ص ساقسهما والرهبان ون َ َّكسوا َ

أ عر ًضا فهدموا ِمن كَنا ِئس ِهما األركان وقتلُوا ق ِ

َ ْ ُّ ُ َ ْ َ ََ َ َ ْ ََ َ ُ

15

الد ُه ْم ون َ َهبوا َ

نساء ُه ْم َو ْأو َ وسل َ ُبوا َ واستَأ َسروا كا َفتَ ُه ْم واستأصلوا شأفتَ ُه ْم َ لصلبان ْ وا ُّ

داد ُه ْم ون َ َز َل علي ِهم ال َقضاء ِبا َص َد َر ِمنْ ُه ْم فيما َم َضى {فهذا جزاء الكافرين} تاع ُه ْم وكُ َ َم َ

( )٩:٢٦يف هذه ا ُّلدنيا الفانية الثّانية األوىل َو َلُ ْم يف اآلخرة َأ َش ّد ا َلع َذاب يف اهلاو ِية.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

658 Pomerantz

شرارة من نا ِر ِهم َفركَ ْض ُت ٌ ية ْأن تَلْفحين ِ ِ ِ

َفعنْ َد ذلك َخ َر ْج ُت منْها هاربًا م ْن ديا ِرهم َخش َ

ِ ِ

ب ُت ِ األرض ب َق َد َمي َوقَط َْع ُت ا َلع ْمق ب ِر ْجلي وأنا َأ ْمشي وأنني إىل ْأن

وصلت إىل تزيين َفع َ ْ ُ َ 20

َّ َّ

ِ ِ ِ

املتوسنياعةً من ّ يت فيه مجاعةً من املُتَ َع ّممني وربَ َ وأتبارك فرأ ُ َ بارك ُألصلّي فيه اجلامع امل ُ َ

َ

س ٍ

حنيف ضعيف ون َ َف ٍ ٍ سيقول ِحب ٍ ِِ َ َ

هو على ظ َْهره ُملقى وهو ُ ّ وبينهم َشيْ ٌخ قد أنْقى وما أب ْ َقى َو َ

أحوايل َفن َه َض إليه ِ ِ ِ

لكالم واستوفوا َمقايل واستعفوا م ْن ْ واسعوا م ّن ا َ أجل ُسوني بسال ٍم ْ ْ

ط حاج ِب ِيه ُبرفادة قاده َربَ َ ساعة فلَما استوى جالِسا من ر ِ ٍ اجلماعة َو َأق ْ َعدوه يف ِ َر ْه ٌط من

ُ ً َّ

ياء لفْ ِظ ِهبعصابة [كذا] ولبس خلق ِجلبابِه ثم أشار إىل القو ِم متك ِلما واستنار ِبض ِ ِ وشدها

ًّ ْ َ ّ َ َْ َ ََ ّ 25

مج ًما وقال: جا وأنار بسن ِاء وع ِظه ُم ِ ُم َتْ ِ ً

َ َ َ َ ْ َ

وعوا ِ وب ا ِ

لواعية والنُّ ُف ِ ول ا ّلش ِام ِلة وال ُقل ُ ِ لكام ِلة والن ُق ِ ول ا ِ يا ذوي الع ُق ِ

اسعوا ُ وس ا ّلداعية ْ َ ُّ ُ

ْفروا َو َتاوزوا ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ

واص ُبوا تَظ ُ وانْتَفعوا وأنْف ُعوا وأقْل ُعوا تُنْ َفعوا َوصلوا تَصلوا واتَّض ُعوا تُرفعوا ْ

واس ِع ُفوا تُ ْس َع ُفوا وال تَ ْع ِس ُفوا تُ ْع َسفوا واع ُفوا تُ ْع َر ُفوا ْ

ِ

صدقُوا تَلْتَ ُقوا و َأنْف ُقوا تُ ْل َ ُفوا ْ تُ ْ َرزوا َوتَ َّ

ناص ُحوا تَفْل َ ُحوا َف َم ْن َز َر َع َح َص َد وال تن ِدموا تندموا و ِيسروا وال تع ِسروا وساحموا تربوا و ِ

َُ ّ َ َ ُ ََُْ َ َُ ّ َْ َ َ ّ 30

شرا يره}()٩٩:٧-٨ ومن فرش رقد {فمن يعمل ِمثقال ٍ

ذرة ًّ ذرة خريا ً يره ومن يعمل مثقال ّ َ ّ ََ ْ َََ َََ ََ ْ

لسة العلَماء ا ِ اورة الصاحلني والنفق ِة يف ا ِلدي ِن وما ِ ليقني وم ِ ِ

لعاملني ُ ّْ َ ُ َََ ّ باد اهلل ُحب ْس ِن ا ِ ُ فعليكم ع َ

أصل ُ ُه ِم َن ال ِطّني ثُ َّم ِم ْن املاء امل َ ِهني ثُ َّم َخل َ َق َك يف ِ ِ ِ ِ

َو ُمرا َف َقة ا ُملْسنني َو ُمالَطَة املَساكني فيا َم ْن ْ

ْمت ِه يا ِم ْسكني َو َأ ْخ َر َج َك بَ َش ًرا َس ِويًّا َو َج َعلَك طيف ِحك ِ شاء ج ِنني ودبر َك بِل َ ِ ظُلمات ا َألح ِ

َ َ َ َّ َ ّ َ

ِِ ِ ِم َن امل ُ ْس ِل ِمني َفهذه ِم ْن تَ َن ُّو ِع نِ َع ِم اهلل عليْ َك بتمكني

فاعبد َرب َّ َك َوكُن م َن ا َّلشاكرين َوال تَغْ َتَّ ْ 35

ب على َعزائ ِم ا ُألمو ِر وال واإلنعا ِم واإلفضال والسعة وا َّلدعة ْ ِ باإلمهال والرفاه ِة وا َألم ِ ِ

واص ْ َّ ْ َّ َ

ط وإن ط لك يف ال ِ ّرزق ال تَ ْشتَ ْ ط وإن بُ ِس َ عليك يف ِر ْز ِق َك ال تَقْ َن ْ ت َ ِ

وإن قُ ّ َ تَظْ َفر بال َف َر ِج واحل ُ ُبور ْ

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 659

ِ

واخل َ ْع ِر َداء ب ِبَ ْن َم َضى تَ َ

لق ا ِ ّلرضى ْ وإن حاسبت نَفْس َك ال تَغْل َ ْ ِ

ط واعتَ ْ َ َ تسخط ْ بت ال َ ُعوق َ

ِ ِ ِ ِ

الط ََّم ِع َوال تَ َق ْع يف ا َّلز َم ِع واعتم ْد على هذه ا َألبيات وما فيها من ا َلوصيّات فإن ّي ّ

مسيتُها ا ُلع ْمدة

َلينْ َجلي بها ُص َدأ املعدة ّثم متايل ط ََربًا وأنشد ُمط ِربًا وقال[ :من البسيط] 40

ِإي َاك يغْ ِر َ ِ ِ ِ

يك با َألط َْما ِع َم ُ

غرور ُ َّ وريَا طَال َب ا ِ ّلر ْزق َع ْسفًا َو ْه َو َمقْ ُه ُ

ِ ِ ف ا َّلس ِب ُيل ِإ َل َما لَيْ َس تُقْ َس ُم ُه

طور َغ ْ َي الذي قَ ْد ُر ُه ف الل َّ ْو ِح َم ْس ُ كَيْ َ

ِ َ ِ

هور ِ

َوأن ْ َت ف قَ ْب َضة ال َق َّهار َمقْ ُ ف تُ ْد ِركُ ُه تَ ُر ُوم بِاجل َ ْه ِل َأ ْم ًرا كَيْ َ

ْ ِ

ما َل ْ يَك ُْن لَكْ َوإ َّن ا ِ ّلر ْز َق َمأ ُ

مور ن ا ُلع ْم ِر ُملْتَ ِم ًسا ِ ِ ِ

أفْ َنيْ َت باحل ْرص كَ ْ َ

َ

ودة ِسيَّ َما َما ِف ِيه تَ ْس ِخيـ ُـر َمْ ُم ٌ احل ْر ُص يف طَل َ ِب ال َفانِي َع َو ِاق ُب ُهما ِ 45

شور لَع َّل يأْتِ َ ِ اح َر ْص ِ َب ْز ٍم َعلَى ا َلب ِاقي َو َح ِ ّصل ْ ُه

يك بامل َ ْسمو ِح َمنْ ُ َ َ ْ

زور َدعْ َعنْ َك ْز َين َة ُدن ْ َيا كُل ُّ َها ُ ِإ ْن كُنْ َت تَأْ َم ُل ِف ا ُأل ْخ َرى كَ َر َامتَ َها

َف ِإ َّنَـا ِهـي َت ْ ِيي ٌـل َوتَ ْص ِـوي ُـر َو َش ْه َوتَ َها ا ُّلدن ْ َيا َعنْ َك َو َخ ِّل

َ

ِ ِ

َع َسى يَك ُْن ل َ َك ِإ ْن ُوفّقْ َت تَأْث ُري اجتَ ِه ْد َما ُد ْم َت ُمقْتَ ِد ًرااع َم ْل َوقُ ْم َو ْ

َو ْ

َو َأن ْ َت تَ ْ َت َأ ِدي ِم ِ ِ

ِ

ا َأل ْرض َمقْ ُ

بور م ْن قَ ْب ِل َأ ْن تَ ْر َج َع ا َأل ْع َض ُاء بَال َيةً 50

تَقْ ِدي ٌـم َوتَأْ ِخي ُـر َفامل َ ْو ُت َما ِف ِيه َفا ْغ َن ْم َح َياتَ َك َوالتَّقْ َوى تَ َز َّو ْد ُه

ـور

احل َ ُـال َم ْست ُ ُرطُوبَ ٌة َو َعلَيْ َك ان بِ ِه ِ

يك بَ َقايا َوالل ّ َس ُ َما َد َام ِف َ

وف تَقْ ِص ُري وال يرى ل َ َك ِف املَعر ِ

ُْ َ َ َُ ات تَل ْ َق ِر ًضا واجهد علَى سب ِل الطَّاع ِ

َ َ َْ ْ َ ُُ

يص َوتَك ِْفي ُـر ِ ِ

َففي امل َ َقادي ِر َتْح ٌ

ِ يبات ا َّلد ْه ِر ُمْتَ ِسبًا واص ِب علَى نَا ِ

َ ْ ْ َ

لص ْ ِب َت ْ ِر ُير ودع َ ِي ِ

يء ف َش َر ِاب ا َّ

ْ َ َ لص ْ ِب كَأْ ًسا َفا ِّلش َف ُاء بِ ِه ِ

اش َر ْب م َن ا َّ َو ْ 55

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

660 Pomerantz

ـور ِ ش َأ ْو َع َد ُه ْم العر ِ لصابِ ِر َين ِإل َ ُه

وح امل َ ْـر ُء َم ْشك ُ هنئَةً َويَ ُر ُ َْ َفا َّ

يَأْتِيه ِم َن ا َلغيْ ِب َأ ْم ٌر ِف ِيه تَيْ ِسيـ ٌـر َأ ْم ٌر َأن ْ َت تَ ْ َذ ُر ُه ان

يَا طَا َلَا كَ َ

رور ويأْتِ ِه بِنجا ِح ا ِ قَد يد ِر ُك ا ِ

لص ْب َم ْس ُ َّ ََ ََ اجتَ ُه

ُور َح َلصاب ُر امل َ ْشك ُ َّ ْ ُْ

ِ

سور ْ

ول َو َمأ ُ ِف َو ْرطَة اهلَ ِّم َمك ُْب ٌ َو َم ْن يَك ُْن َح ِر ًجا ُم ْستَ ْع ِجال ً َأبَدا ً

ِ ِ

دورحالَن ُ ُه َواحلُك ُْم َمقْ ُ يد ُ ْ

يُف ُ َص ّر ْف َع ِن ال َقل ْ ِب َه ًّما َما ْ

استَط َْع َت َفما 60

َم َق ِادي ُـر

ِف كُ ِّل َما َر َام ِإ ْذ َحل َّ ْت َف َك ْم تَ َق ِاد َير َضل َّ ْت َع ْن ُم َق َّد ِر َها

ِ ِ ِ

ذور

َم ْع ُ افط َف َما ال َقانطُ ا َّلس َّر ُتَقْ َن ْ َو َسل ّ ِم احل َ َال لل ْ َم ْو َل ال َك ِري ِم َوالَ

ظ َم َقالِـي َف ْه َـو تَ ْذي ُـر وصي َك َها َأبَ ًدا َفه ِذ ِه عمدة ُأ ِ

اح َف ْن َف ُْ َ َّ

ب ُ ْ ٌَ َ

صور

يس َمْ ُ وطَعمها َذ َاك ِف التَّع ِك ِ َم ْن الَ َذ َاق ل َ َّذتَ َها َوالَ يَ ُغ َّر َك

ْ َ ََْ

والَ تُرى ِع ْبة لِلنَّ ِ

اس تَ ْع ِب ُري با ِ ِ َوكُ ْن ِبَ ْن قَ ْد

َ َ َم َضى م ْن قَ ْب ُل ُم ْعتَ ً 65

ثور ِ ِ ادتِ ِه ِ ِ

ف ن ُ ْصحي َف ْه َو َم ْع ُ َو َم ْن ُيَال ُ قَ ْول م ْن َس َع َ َف َم ْن تَ َدب َّ َر

قال ِ

ثام ُر بن َز َّمامٍ:

آفاقهم آماق ِهم وتَ سرت قلوب اجلمو ِع اجملتمعون ِمن ِ فتحدرت دموع املُستم ِعني ِمن ِ

ْ َ َّ َ ْ ُ ُ ُ ُ َ َ َّ ْ ُ ُ ْ َ َ

اس َم ْش ُغ ْوفون بِه ُحبًا ِِ ِ ِ ِِ

رت ُز ِبقاله َو َيْ َ ِت ُز على نَفْسه أن َي ْ ُر َج َع ْن َأقْواله والنّ ُ َو َج َع َل كُ ٌّل يَ ِ َ

وه إفضاال ً َحتَّى دواء ِعظَته ِط ّباً هذا ومستوفون ِمن ِ

وأو َس ُع ُ وه نواال ً ْ أس َع ُف ُ

والقوم قد ْ ُ َ 70

وداع ا َأل ِح َّب ِة َو َص َد َع قُلُوبَ ُهم بِتَ ْم ِك ِني احمل َ َّب ِة َفت ِب ْعتُ ُه

القوم َ ُمل َئ ِجرابُ ُه َو َ

حان َذهابُ ُه َو َو َّد َع َ

ِ

ِ

فقلت أبا كل تغريش ُ الغ ِريش وإمام ّ ألتّ َذ معه َع ْه ًدا و ُأ َوك ّ َد َم َع ُه ُو ًّدا فإذا هو أبو فيد َ

املوه َب َة َو َه َّذبَ َك بِهذه الت َّ ْه ِذبَ ِة َأ َأن ْ َت ِبا َص َد َر ِمنْ َك ُمشتَ ِبه أم َغ َري فيد ِبن َأوهب َك هذه ِ

َْ ََ

اجملتث]

ّ ُمنْتَبه فقال[ :من

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

A Maqāma Collection by a Mamlūk Historian 661

ْاشـة

َ ا َلب َش َو َخ ِّـل ُب

ْ َواقْط ون ا َلغ َر ِاشـة َ ُف ُن إع َم ْل

ْ

ِ ِم ْن ظ َو َح ِ ّد ْث َو ْار ِخـي ْ َو ِع

ْـاشـة

َ ْارت َع َر َاحتَيْ َك 75

اشـه

َ احل ُ َش ِف َيما تُ ِذي ُـب اعةَ لص َن

ِ

ّ شراك ا

َ َوان ْ ُص ْب

ال َف َر َاشه َش ِبي َـه َوكُ ْن وع اجل َ َو ِامد

َ اج ِر ا ُّلد ُم ْ َو

اشـه ِ َو ِإ ْن َوقَ ْع ل َ َـك ُخ ٌّش

َ َفاك ْ ُش ْب َو َح ّص ْل قُ َم

اشـه َ ُع َم ُمقْلَتَيْ ِـه ِفـي َغـ ِريبًـا َر َأي ْ َت َو ِإ ْن

َ َبِـري

ـاشـه احتَـ ِر ْم ْ َف ن اسـاَ َس ِول ْ ِد ِم ْن َف َذ َاك 80

ـاشـه َ َش بِتَقْ ِطيـ ِع ِمنْ ُه َم ْك ٌـر ورك

َ َ ُي اح َذ ْر

ْ َو

اشـهَ َم َع يَ ْب ِغـي ه َذ َاك ِمث ْ ِلـي ـانَ َك َم ْن َفك ُُّل

ِف َـر ِاشـه َف ْـو َق يَ َن ُام َو ٍان ِمث ْ َـل تَ ُك ْـن ََفال

اشـه

َ ُم َش احل َ ِلي ِـب ِم َن يَل ْ َقـى ا ِ ّلر ْز َق َويَطْل ُ ُب

وودعتُه ُ

ّ بت عن خياالته وفارقتُه وفارقين

ُ وحتج

ّ بت من أحبوالته

ُ فتعج

ّ زمام

ّ قال ثامر بن 85

.وودعين

ّ

10 Commentary on al-Maqāma l-Tīzīniyya

The edition reproduces the vowels of the text of the Maqāma as it is found in

MS Laleli 1929 to preserve rhyme and metre. In the commentary are noted vari-

ous deviations from Classical Arabic, as well as other irregularities.

l. 4 اجلَّالسis the plural of اجلَلْسwhich means “rugged ground or land” see

E.W. Lane, Lexicon, London, Williams and Norgate, 1863, II, p. 80.

l. 9 هذه املدينتنيis common in Middle Arabic texts, see Joshua Blau, A Handbook

of Early Middle Arabic, Jerusalem, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2002, p. 42.

Arabica 61 (2014) 631-663

662 Pomerantz

l. 9 قد كانواis common in Middle Arabic texts.

l. 11 كنائس؛ قسائسare diptotes. However, both are marked with tanwīn in the

Laleli MS; see Wolfdietrich Fischer, A Grammar of Classical Arabic transl.

J. Rodgers, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2002, p. 63.

l. 13 صورة احملمد ُية ِ

ّ ُ ْ العساك ُر املنis a reference to the forces of al-Malik al-Ẓāhir Baybars I

that lay siege to Antioch on 4 ramaḍān 666/19 May, 1268. The author here is

mistaken concerning Latakia, which was not taken by Muslim forces at the

same time as Antioch, but twenty years later in 5 rabīʿ I 686/20 April 1287.

l. 17 كُدادهمis that which remains in the pot after cooking, see al-Zabīdī, Tāǧ

al-ʿarūs, sub radice K.D.D.

l. 18 األولة

ّ appears to be a mistake for األوىل, common in Middle Arabic texts.

l. 20 تزيينis described by Yāqūt, Muʿǧam al-buldān, s.v. “tīzīn” as a large village

in the vicinity of Aleppo.

l. 24 رفادةa support (?) is unclear; see Reinhart Dozy, Supplément aux diction-