Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Who Are The Waswahili Eastman

Who Are The Waswahili Eastman

Uploaded by

Yussuf HamadOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Who Are The Waswahili Eastman

Who Are The Waswahili Eastman

Uploaded by

Yussuf HamadCopyright:

Available Formats

Who Are the Waswahili?

Author(s): Carol M. Eastman

Source: Africa: Journal of the International African Institute , Jul., 1971, Vol. 41, No. 3

(Jul., 1971), pp. 228-236

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the International African

Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1158841

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Africa: Journal of the International African Institute

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

[z228]

WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI?

CAROL M. EASTMAN

THE question as to who are the Swahili has long been controv

C. H. Stigand is responsible for the most widely accepted definiti

A Swahili . . . in the more confined sense of the word, is a descendant o

original Arab or Persian-Arab settlers on the East African Coast. In the b

the word it includes all who speak a common language, Swahili.'

As a field-worker doing linguistic research in East Africa on the Sw

this problem of identification became acute for me. Certain people

selves Swahili and others not, while some of those so considered may

self concept at all. With the standardization of Swahili and its growt

language in Tanzania and its use as a lingua franca all over East Afric

of definition is about to resolve itself. Swahili-speaking people are be

and Tanzanians, rather than Swahili or non-Swahili. A pattern, how

evident allowing me to categorize componentially the Swahili peopl

The Swahili language, while indeed a lingua franca is also the first and

for some East Africans. These people are Swahili in a sense that

For others, Swahili is a language used in order to communicate with t

neighbours, and friends from diverse linguistic backgrounds.

Linguistic criteria may be used to differentiate people who are calle

selves Swahili. Some useful indices are:

I. The amount and kind of loan words a speaker employs, e.g. Arabic, English,

Gujerati, etc.

2. The degree to which a speaker adheres to the grammatical rules of the lan-

guage, e.g. to what extent grammatical concord is used syntactically; whether

or not the intonation patterns are influenced by other languages.

3. Is Swahili the speaker's first and only language? If not, what are his other

languages ?

Complicating factors such as the teaching of Swahili to all children in many East

African schools and the implication of such a procedure that the ' best' speakers are

more truly Swahili than the' worst' also need to be taken into account.2 An approach

such as this can only show how many types of Swahili speakers there are.

Without resting our definition of the WaSwahili on criteria like these, i.e. how well

or how grammatically a person speaks, I thought it might be possible to arrive at an

analysis based on contrasts which correspond to East African conceptions of who

a Swahili is, the idea being that such a contrastive analysis would reflect what is

considered to be the inclusive connotation of the term Swahili as applied to a people

and what a person considers his own position to be within that connotation.

X Stigand, 1913, ' The Swahili', chapter 6, p. I 6. Polome, I967, chapter i ' The Language Situation'

S Regarding the people who speak Swahili see Section A, pp. x-8.

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI? 229

It seems that while a Swahili must have knowledg

all who know or use Swahili are considered or consid

other hand, in the broadest sense, to be a Swahili d

also being something else. For example, a member of

and speak Swahili. He may call himself a Swahili an

a Kikuyu to be termed a Swahili would be unusu

a statement, given later in this paper, as to whom

in which Swahili speakers of the 'suburbs' coul

up-country tribes such as the Kikuyu. Thus the ran

is very great indeed and is variable according to th

My field notes constantly indicate '. . . is non-

considers self Swahili ' or ' ... is considered to be an

with Muslim names,'. . . does not consider himself

use only 'Swahili' informants for my work. The v

as I looked for my informants will be indicated bel

For the purpose of my study of Swahili dialect, m

from one end of the resulting definitional continuu

Muslims of coastal parentage who had Muslim n

extent, geographically and culturally homogeneous

The basic criteria which emerged in my search f

Swahili speakers were:

i. Religion: Muslim, Christian, other

2. Geographical origin: self or parents born on th

3. Name: Muslim, Christian, other

4. Educational background: Koranic school, Miss

A. H. J. Prins' gives the following criteria which a

a type of civilization, and a Coastal habitat. But he also

I. '... any man from the coast who speaks Swahili a

2. ... any Muslim African from anywhere.'

3. one's inferior

4. anyone who is a mixed descendant of Africans, Ara

the exact ethnic makeup or proportion of these comp

East African coast or the islands adjacent to it'.

5. any coastal African who speaks Swahili either as hi

speech of his daily life. (Prins, pp. I 1-2)

Thus, Prins himself is not very clear in his definit

further that' The name Swahili is not applied by the

selves' (p. 12). He mentions that earlier writers did

was that many people did apply the term to thems

agreement with Prins's further observation that' In

however, it is always true that a man is never Swa

Prins also indicates that, at the time of his stu

to imply negative characteristics such as 'slave

I Prins, x96i, pp. II-i2.

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

230 WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI?

occupational position, and a general "boorish ", unciviliz

look on life' although some people answering such a de

Arab descent.

Today, however, the situation seems to be changing. An example of this may be

seen among the members of the Arab League in a place such as Mombasa, Kenya.

The members today purposely emphasize their self concept of being Swahili rather

than Arab. If a person is considered a Swahili today, he is assumed to be of' good '

lineage. It may be argued that this is a matter of political expediency following the

attainment of independence in the countries of East Africa and the subsequent

development of nationalism. As mentioned above, all distinctions such as these

discussed here are being discouraged with the intent that people should think of

themselves as Africans first, and then as Kenyans or Tanzanians.

My findings indicate that all Swahili are to some extent Swahili users, no Swahili

may also be an Asian or European, and that no one is primarily a Swahili. The two

extremes are Muslim-Arab Coastal Swahili and non-Muslim Up-Country African

Swahili. All people who are considered Swahili today are native-born Kenyans or

Tanzanians. The references in this paper to coastal and non-coastal areas refer to the

coasts, off-shore islands, and interiors of those two countries alone. The non-

Muslim-Swahili tend to refer to Muslim Swahili speakers as 'Arabs' while the

Muslim-Swahili call the non-Muslims 'Africans '. The non-Muslims confuse Arabs

with other Muslims since many Muslims descend from Arabs or call themselves

Arabs. The Muslims call the non-Muslims Africans, implying that they have no

Oriental background.

Since independence there is a growing trend in both countries for all to consider

themselves Africans. At the same time, with the current development of Swahili

literature and pride in Swahili as a national language, it seems that the extremes are

now merging. Indeed, the term is today rarely used in any derogatory sense. The

decline in numbers of people who use the Arabic script' is hastening this merger,

although, among literary men, a distinction is made between those who write tradi-

tional poetry (using either Roman or Arabic script) who regard themselves as 'true'

Swahili, and those who use modern literary forms and Roman script who are regarded

more as Africans than Swahili.

People on the island of Pate and in parts of northern Kenya made it plain to me

that in their opinion those who speak the Bajun dialect of Swahili are Bajun and not

Swahili. The Bajun made this clear as did their neighbours on Lamu. It seemed to me,

however, subjectively, that the Bajun took pride in being Bajun while at the same

time the inhabitants of Lamu were proud to be Arab, Swahili, or African. The Bajun

are Muslim, Coastal, of mixed parentage (i.e. generally of Persian and/or Arab plus

African descent), with Muslim names and users of the Arabic script.z

Using the four contrasts mentioned above, I found that eight groups of people

who fall under the broad term Swahili could be distinguished. The following labels

may be attached to the feature complexes defining each type:

Harries, 1962, chapter 2. Arab-Swahili have ' tribal' roots. The Bajun report

2 Among the 'Arab' Swahili, just as among the that there are Chinese-Bajun among them. See

'African', there are many ethnic groups. As you Eastman and Topan, I966.

have Giriama Swahili or Digo Swahili, so, too, the

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI? 231

I. Mwarabu safi 'Pure Arab'

2. Mwarabu 'Arab'

3. MSwahili safi ' Pure Swahili'

4. MSwahili' Swahili'

5. Mmasihii wa Pwani ' Christian of the Coast '

6. Mwafrika wa Pwani 'African of the Coast'

7. Mkristo wa Bara ' Up-Country Christian'

8. Mwafrika wa Bara ' Up-Country African'

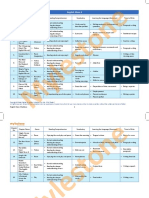

' A g 11 3 B C

Muslim + + + + -

Coastal origin + + - -

Muslim name + + - -3

Christian name + - + 4

Koranic school + - + - 5

Distinctive Feature Matrix: Swahili

(blanks represent redundancy features)

This feature matrix may be illustrated in the following diagram:

Swahili

These labels are only labels. Any East African hearing them in the context of

Swahili would understand them as designating within broad limits a particular feature

matrix. The terms are all used and understood to mean what their make-up indicates.

Thus, as pointed out earlier, there are Christians, Arabs, and Africans who, in no

I Mmasihii is the Swahili word for ' Christian' word in Swahili for ' Christian' and is more com-

and is more common on the Coast. Mkrisfo is a loan monly used by Up-Country or non-native speakers.

Q

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

232 WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI?

way, could also be classed as Swahili. Often to disting

Arab, he would be called a Swahili while a Coastal

Swahili to distinguish him from a Coastal non-Christia

Up-Country African, he tends to think of all Coastal p

with no sharper divisions. If he is a Coastal Christian,

people as Swahili. But, an analysis such as this contras

validity for the researcher. Prins stated that, '... the

an epithet of reference and hence an important sociolo

ever used for self-identification '. This is perhaps becau

always going to be a different kind of Swahili from onese

one or a few features of contrast.

The following is an analysis of the term Swahili person. It assumes only that by the

general term Swahili is meant one who speaks the kiSwahili language and is a native

of Kenya or Tanzania. Categories 7 and 8 actually define people who are not commonly

thought of as Swahili. These categories are included because they present minimal

contrasts with the Coastal African and Coastal Christian who are thought of as

Swahili, for in many instances these people think of themselves as Swahili. These last

two categories refer to the Up-Country Christian and African Kenyan or Tanzanian

citizen who uses Swahili.

From the matrix and tree analysis, it would appear that a person designated

MSwahili is one who is a Muslim, but who has a non-Muslim name (i.e. a Bantu one

instead) and who did not receive Islamic schooling: he differs from an Mswahili

Safi in that the latter received training at a Koranic School, from a Mwarabu who has

a Muslim name, and from a Mwarabu Safi in both name and education. All four are

Swahili by religion. This distinguishes them from the other four who only have

language and nationality in common with this group but who are still Swahili in

that respect.

Two examples of the definition of a Swahili follow, which were supplied to me by

a native Zanzibar woman of Comoro Island ancestry and by a man from Up-Country

Tanzania. Both regarded themselves as Swahili. These indicate that the preceding

analysis is in some ways too specific and in others too general, and that a number of

the indices of contrast may need reworking. They show that a working definition

such as that derived from my analysis cannot apply uniformly but serves only as an

indicator of the range of applicability of the term.

SUMMARY OF STATEMENT OF ZANZIBAR WOMAN

The people referred to as WaSwahili are not so called on a linguistic basis alone.

The term MSwahili (pl. WaSwahili) varies with the time and place of reference apart

from the individual using the term. In Zanzibar, for instance, at one time an MSwahili

was anyone whose father and mother were Africans regardless of their birthplace.

The term Mwafrika was rarely used until the early nineteen-fifties.

An MSwahili would be anyone answering to one of these combinations:

i. Both parents Africans born in Zanzibar or Pemba or neighbouring coastal

areas (Mombasa, Lamu, Tanga, Mafia).

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI? 233

2. Father African, mother Indian, Arab, or other, regardless

language spoken at home was Arabic (a very rare case) or an I

and regardless of whether or not the person's physical feature

Any African born on Zanzibar (even though the parents may hav

mainland) speaking Swahili and another language in addition wou

as MSwahili by an Arab or Indian or Up-Country African.

An African whose father was an indigenous African and whose m

of the Comoro Islands is still referred to as MSwahili. On the oth

father or both parents came from the Comoro Islands, the child i

even if he and his siblings were born on Zanzibar. Even descenda

came from the Comoros five or six generations back are not regar

people.

In contrast, the inhabitants of the East African Coast known as the Shirazi-

descendants of the Persians who intermarried with Zanzibar natives-are regarded

as true WaSwahili. They speak only Swahili and live mainly in villages north of

Tumbatu island and on the island itself.

An Arab who marries an African on Zanzibar, Lamu, or anywhere on the Coast of

East Africa will have his offspring regarded as Arabs by his clan. However, a female

Arab marrying an African will have her offspring regarded as WaSwahili.

A Comorian woman who marries an Arab has Arab offspring. A Comorian man

who marries an Arab woman will have Comorian offspring.

The question of religion, skin colour, features, given name, and mode of attire

seems trivial in describing an MSwahili on the Coast-but, to an African from the

mainland, these are the criteria used.

Factors such as the ability to read the Koran, or to speak grammatical Arabic

(which few East African Arabs can do) or the degree of adherence to Arabic culture

are poor criteria for defining WaSwahili.

SUMMARY OF STATEMENT BY SUKUMA MAN

There are five main divisions of the people who fall into the category of

WaSwahili;

I. WaSwahili wa Pwani-the Swahili People of the Coast

2. WaSwahili wa Unguja-the Swahili People of Zanzibar

3. WaSwahili wa Bara-the Swahili People of Up-Country

4. WaSwahili wa MaShamba-the Swahili People of the ' Suburbs '

5. WaSwahili wa Tamaduni-Swahili Scholars

A Swahili person speaks Swahili and no other vernacular on most occasions. Today

there are Muslim and non-Muslim Swahili. Historically, the Swahilis are descendants

of Arabs, Persians, and Chinese who intermarried with Africans dwelling within

twenty miles of the shore all along the East African Coast. As a result of the ivory

trade, Swahili began to move to such places as Tabora, Ujiji, and Kigoma. Most

Up-Country Swahili today are still found near the commercial centres.

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

234 WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI?

The Swahili people of the Coast may be either Muslim

are in contact with outside influences (i.e. the mass me

cultures, etc.). These people may be further divided into

(a) The Swahili people from Tanga who are'... pretty c

there and there is a tradition for people from distan

go to Tanga to train to be Sheikhs and the like.'

(b) The Swahili people of Mvita who ' speak a strange ty

less cultured than those of Tanga '.

(c) The Swahili people of Mombasa. These Swahilis are

Swahilis to the Swahilis of Zanzibar and are, thus, t

Coastal groups.

The Swahili people of Zanzibar are mostly Muslim.

than the Coastal Swahili because of little outside influe

Swahili.

The Swahili people of Up-Country may be divided int

(a) The Swahili people of Tabora who speak Swahili wit

accent.

(b) The Swahili people of Ujiji and Kigoma who speak Swahili with th

accents.

The Swahili people of the suburbs (lit. the fields or plantations) are t

who live in areas around urban centres. They are usually new arrivals in

and do not know the prevalent language. They are people in transition w

ungrammatical form of Swahili and they are generally non-Muslim.

The Swahili scholars comprise those people who live anywhere in East

being well-trained Islamic theologians and Muslims.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

These two statements, as may easily be seen, contradict partly what is

in this paper. Therein lies the crux of the problem. The statement by

girl brings out the fact that whether a child is Swahili or not depends up

father is. Here, too, we see that there are groups of people, such as the

to whom none of the labels in my analysis directly apply. They are no

or African than Swahili-they are Comorians. Culturally, however, they

analysis more as Swahili than as non-Swahili. The argument that the pr

absence of a Koranic School education is not a valid criterion for definin

is a good one. It is valued in so far as education of any kind is inappropr

ferentiating peoples. It is valid, too, in so far as Koranic schooling exclu

young and the female-many of whom indeed are WaSwahili. However,

to diffoentiate the 'pure' Arab and the ' pure' Swahili from Arabs and

general, it seems useful. A wife or child of a Mwarabu Safi would also be Mwa

The point that criteria such as religion, skin colour, features, given n

type of dress are used by mainland Africans to distinguish coastal peopl

Swahilis, or Africans, is a salient one. The classification of the WaSwahili

Sukuma man is a case in point.

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI? 235

His classification, too, is very broad, including all those wh

often than any other vernacular. This classification includes

(Category 7, incidentally, would include this particular man

A comparison of his classification with my categories break

I. Mwarabu Safi

2. Mwarabu WaSwahili wa Pwani

3. MSwahili Safi WaSwahili wa Unguja

4. MSwahili WaSwahili wa Tamaduni

5. Mmasihii wa Pwani

6. Mwafrika wa Pwani

7. MKristo wa Bara WaSwahili wa Bara

8. Mwafrika wa Bara WaSwahili wa Mashamba

It must be pointed out that Coastal origin or contact somewhere in the p

to be an integral part in defining the WaSwahili. It is interesting that the

girl's statement assumes coastal or Zanzibar origin regardless of where th

father or mother came from while the Sukuma man takes into account m

albeit from coastal areas.

The question, 'Who are the WaSwahili? ' is by no means answered here. Perhaps

a more extensive study setting out to deal with this particular question which would

consider various linguistic criteria as well as these attitudinal ones of ' self' and

'others ' would be fruitful.

REFERENCES

EASTMAN, CAROL M., and FAROUK, M. T. TOPAN. I966. ' The Siu: Notes on the People and Their

Swahili, vol. 36/2, pp. 22-48.

HARRIES, LYNDON. 1962. Swahili Poetry. Oxford: Clarendon press.

POLOME, EDGAR C. I967. Swahili Language Handbook, Center for Applied Linguistics.

PRINS, A. H. J. I96I. The Swahili-Speaking Peoples of Zanzibar and The East African Coast. Dar

London: International African Institute (Ethnographic Survey of Africa Part XII).

STIGAND, C. H. I913. The Land of Zinj. London.

Resume

QUI SONT LES WASWAHILI?

A CETTE question difficile, il est couramment repondu par une definition de Sti

Swahili descendent d'un des premiers immigrants arabes ou persans etablis sur l

l'Afrique de l'Est, et comprennent, au sens le plus large, tous ceux qui parlent Sw

Cet article traite de nombreux autres points particuliers a considerer avant de

une definition. Bien que leur origine c6tiere et la connaissance de la langue Swah

des facteurs determinants, cela n'implique pas que ceux qui connaissent ou utilise

langue soient consideres eux-memes comme des Swahili. L'auteur a utilise le

suivants permettant de reconnaitre un veritable Swahili: (i) religion; (2) ori

graphique; (3) appellation; (4) systeme d'education. Selon ces criteres on peut

groupes en 8 categories: (i) Arabe authentique; (2) Arabe; (3) Swahili authe

Swahili; (5) Chretiens de la c6te; (6) Africain de la cote; (7) Chretiens apatrides; (

cains apatrides.

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

236 WHO ARE THE WASWAHILI?

II y a cependant quelques groupes, tels les habitants des iles Comores, auxque

de ces descriptions ne peut s'appliquer; ils ne sont pas plus arabes ou africains

ils sont Comoriens, bien que culturellement, ils soient proches des Swahili.

On peut dire que tous les Swahili sont a quelque degre pros des locuteurs Sw

Swahili ne peut etre en meme temps asiatique ou europeen; aucun n'est primit

Swahili. Les deux categories extremes sont constituees par les Swahili c6tiers

arabes, et les Swahili africains non-musulmans apatrides. Sont consideres

comme Swahili tous les groupes originaires du Kenya ou de Tanzanie. Les

musulmans ont tendance a considerer les Swahili musulmans comme des Arab

que les Swahili musulmans les appellent 'Africains '. Depuis l'independance

tendance croissante pour tous les habitants du Kenya et de Tanzanie a se consi

Africains. En meme temps, grace a la diffusion progressive de la litteratu

manifeste une certaine fierte de voir la langue Swahili reconnue comme langu

il semble que les positions extremes soient en train de se confondre. Aujourd'

'Africain ' est rarement utilise dans un sens pejoratif.

NOTES FOR CONTRIBUTORS TO AFRICA

CONTRIBUTIONS should be addressed to the Editor. Articles should not excee

including footnotes and references. Longer papers can be accepted in excep

stances if a subsidy can be provided to meet the cost of printing additiona

Articles should be typed in double spacing, on one side of the paper only

margins to allow for editorial marking. Clean copy ready for printing sho

Authors are advised to keep a copy of their texts as the return cannot be gu

in African languages should be underlined and special characters kept

Footnotes may be placed at the bottom of the page on which they occur o

the end. Bibliographical references should be cited only briefly (i.e. author a

text or in footnotes, and an alphabetical list of references given in full at

article. Where appropriate the text should be divided by suitable headings an

Tables outside the text should be typed on separate pages, numbered co

given headings. Maps and other line-drawings should be submitted in final

for size) on good-quality paper.

Contributors are asked to provide a summary of their articles of 250

translation into French or English.

Galley proofs are submitted to authors but only essential corrections can

additional matter cannot be inserted at proof stage. The Editor reserves th

any corrections or alterations he may deem necessary.

Contributors receive 25 free offprints of their articles; extra copies can be

price on request, if ordered before publication.

This content downloaded from

197.221.210.239 on Tue, 01 Jun 2021 06:45:15 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Jolly Phonics Parent Teacher GuideDocument12 pagesJolly Phonics Parent Teacher Guidebonitarodz73% (41)

- Affluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the BushmenFrom EverandAffluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the BushmenRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Methali Za Kiswahili - Swahili ProverbsDocument368 pagesMethali Za Kiswahili - Swahili ProverbsKombe ZabdiNo ratings yet

- Generous Tolerance in Islam Hamza YusufDocument17 pagesGenerous Tolerance in Islam Hamza YusufDawudIsrael1100% (1)

- Hausa CompleteDocument321 pagesHausa CompleteOscar Federico Spada100% (3)

- The Swahili Civilization: Advances and Change in An Age of TurmoilDocument32 pagesThe Swahili Civilization: Advances and Change in An Age of Turmoilalan_gicheru0% (2)

- Lesson Plan 1 - Sentence StructureDocument4 pagesLesson Plan 1 - Sentence StructureLovely Grace GarvezNo ratings yet

- Final Culture Essay 1Document6 pagesFinal Culture Essay 1Nina HolmesNo ratings yet

- Changing Swahili Cultures in A Globalising WorldDocument17 pagesChanging Swahili Cultures in A Globalising WorldAlex BojovicNo ratings yet

- Kiswahili People Language Literature and Lingua FRDocument21 pagesKiswahili People Language Literature and Lingua FRelsiciidNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Swahili LanguageDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Swahili LanguagePhilemon SundayNo ratings yet

- The Odyssey of Ajamī and The Swahili People: John MuganeDocument24 pagesThe Odyssey of Ajamī and The Swahili People: John Muganelindahnyambura21No ratings yet

- Arabic Langage Culture and CommunicationDocument4 pagesArabic Langage Culture and CommunicationNanzhao DaliguoNo ratings yet

- History SwahiliDocument7 pagesHistory SwahiliHarvey KadyanjiNo ratings yet

- Adnan J Almaney - Cultural Traits of The ArabsDocument10 pagesAdnan J Almaney - Cultural Traits of The ArabsHada fadillahNo ratings yet

- Swahili Term PaperDocument10 pagesSwahili Term PapersaberchickenNo ratings yet

- Vernacularization of Islam and Sufism inDocument18 pagesVernacularization of Islam and Sufism inAmber TajwerNo ratings yet

- Islam and Iran A Historical Study of Mutual ServicesDocument24 pagesIslam and Iran A Historical Study of Mutual ServicesAfraNo ratings yet

- Islamic Culture in Swahili AfricaDocument5 pagesIslamic Culture in Swahili Africaizhar ahmadNo ratings yet

- Fallou Ngom - Ajami Scripts in SenegaleseDocument23 pagesFallou Ngom - Ajami Scripts in SenegaleseStefan MihajlovicNo ratings yet

- Thomas Spear - Early Swahili History ReconsideredDocument35 pagesThomas Spear - Early Swahili History ReconsideredDiego MarquesNo ratings yet

- AU Adamu - The Intangible MigrantDocument16 pagesAU Adamu - The Intangible MigrantZamalo WarureNo ratings yet

- Swahili Language, Culture and LiteratureDocument12 pagesSwahili Language, Culture and LiteratureMwiinyi RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- AFRICAN Language SituationDocument8 pagesAFRICAN Language SituationBradNo ratings yet

- Event Article - MMW 1Document2 pagesEvent Article - MMW 1api-460758621No ratings yet

- No Title: Arabic RevivalDocument3 pagesNo Title: Arabic RevivalAbu TalhaNo ratings yet

- Developing Resources For Modern South Arabian LanguagesDocument12 pagesDeveloping Resources For Modern South Arabian Languagesme youNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press International African InstituteDocument3 pagesCambridge University Press International African InstituteBopailop KopaliopNo ratings yet

- Origin of The BantusDocument13 pagesOrigin of The BantusBoss CKNo ratings yet

- Fusha andDocument9 pagesFusha andajismandegarNo ratings yet

- Al-Ahbash and Wahhabiyya: Interpretations of IslamDocument21 pagesAl-Ahbash and Wahhabiyya: Interpretations of IslamTeklay TesfayNo ratings yet

- Middle Eastern Cultural GuideDocument35 pagesMiddle Eastern Cultural GuideHaiati HabibiNo ratings yet

- SwahiliDocument13 pagesSwahiliapi-278043545No ratings yet

- Religions and Ethnic GroupsDocument2 pagesReligions and Ethnic Groupsapi-275304033100% (1)

- 1 Arabic and IdentityDocument11 pages1 Arabic and IdentityKateryna KuslyvaNo ratings yet

- RCR 121 NoteDocument15 pagesRCR 121 NoteAdeniyi MichealNo ratings yet

- Link Outside Newsletter Summer 2018-1Document8 pagesLink Outside Newsletter Summer 2018-1api-526753073No ratings yet

- HausaDocument2 pagesHausaJoseph SharonNo ratings yet

- Language Style and Register in ContemporDocument12 pagesLanguage Style and Register in Contemporadikwupraise462No ratings yet

- Swahilienglishdi00madauoft - BW - KopiaDocument770 pagesSwahilienglishdi00madauoft - BW - KopiaMartyneJohnNo ratings yet

- The Origins of the Lebanese National Idea: 1840–1920From EverandThe Origins of the Lebanese National Idea: 1840–1920Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Arab Identity and Ideology in SudanDocument23 pagesArab Identity and Ideology in SudanK El YunisNo ratings yet

- Ethnic and Religious Groups Africa RedyellownotesDocument36 pagesEthnic and Religious Groups Africa Redyellownotesapi-275304033No ratings yet

- Language and Identity in The Middle East and North AfricaDocument5 pagesLanguage and Identity in The Middle East and North AfricaEko ErnadaNo ratings yet

- KiswahiliDocument1 pageKiswahilihelene ganawaNo ratings yet

- The Genesis of The Somali Civil War: A New Perspective: Northeast African Studies January 2011Document18 pagesThe Genesis of The Somali Civil War: A New Perspective: Northeast African Studies January 2011Chrs HermesNo ratings yet

- Singing with the Mountains: The Language of God in the Afghan HighlandsFrom EverandSinging with the Mountains: The Language of God in the Afghan HighlandsNo ratings yet

- Nnresearch Paper FinalDocument14 pagesNnresearch Paper Finalapi-671094184No ratings yet

- The Translation Strategies of African American Vernacular EnglishDocument8 pagesThe Translation Strategies of African American Vernacular EnglishVo Minh TriNo ratings yet

- Nnresearch Paper DraftDocument14 pagesNnresearch Paper Draftapi-671094184No ratings yet

- Hausa NigeriaDocument6 pagesHausa NigeriafatimmansoorNo ratings yet

- Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the DisplacedFrom EverandPalestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the DisplacedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- African Ethnic GroupsDocument26 pagesAfrican Ethnic Groupsapi-326023494No ratings yet

- Wisdom of the Tumbuka People: Vinjeru vya Wanthu wa CitumbukaFrom EverandWisdom of the Tumbuka People: Vinjeru vya Wanthu wa CitumbukaNo ratings yet

- Talkin' About TribeDocument8 pagesTalkin' About TribeLaz KaNo ratings yet

- Cognate LanguagesDocument12 pagesCognate LanguagesUnubi Sunday AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Book 9789004233133 B9789004233133 009-PreviewDocument2 pagesBook 9789004233133 B9789004233133 009-PreviewAli Ahmed Wario AliNo ratings yet

- Jonna Rock - Intergenerational Memory and Language of The Sarajevo Sephardim-Springer International Publishing - Palgrave Macmillan (2019)Document293 pagesJonna Rock - Intergenerational Memory and Language of The Sarajevo Sephardim-Springer International Publishing - Palgrave Macmillan (2019)ABD SHATERNo ratings yet

- Potentials of Language Documentation MetDocument146 pagesPotentials of Language Documentation MetYussuf HamadNo ratings yet

- Morphology Lecture 1Document8 pagesMorphology Lecture 1Yussuf HamadNo ratings yet

- File 45492Document11 pagesFile 45492Yussuf HamadNo ratings yet

- Babu A MemoirDocument8 pagesBabu A MemoirYussuf HamadNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Variation in NavajoDocument260 pagesLinguistic Variation in NavajoYussuf HamadNo ratings yet

- R.M. Santilli - Foundations of Hadronic ChemistryDocument282 pagesR.M. Santilli - Foundations of Hadronic Chemistry939392No ratings yet

- Character Analysis RubricDocument2 pagesCharacter Analysis Rubricapi-270339587No ratings yet

- Gnomish LexiconDocument76 pagesGnomish LexiconKarl Andersson100% (1)

- Eng5 Q4 Week7 16pDocument16 pagesEng5 Q4 Week7 16praymondcapeNo ratings yet

- TRAN 301 Arabic Newsletter Spring 2022Document3 pagesTRAN 301 Arabic Newsletter Spring 2022hNo ratings yet

- Adaptive Module: English-3 Solution: Class SheetDocument4 pagesAdaptive Module: English-3 Solution: Class SheetRamesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Polyglot How I Learn LanguagesDocument216 pagesPolyglot How I Learn Languagesleahgiesler100% (6)

- French Lesson 1 WebsiteDocument4 pagesFrench Lesson 1 WebsitemoNo ratings yet

- Mylestone Syllabus C4Document13 pagesMylestone Syllabus C4Nitesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Verbos Regulares en Inglés y EspañolDocument51 pagesVerbos Regulares en Inglés y EspañolJuan GarciaNo ratings yet

- HWPlusSE2e Beg Progress Test 1Document3 pagesHWPlusSE2e Beg Progress Test 1Ayed IbrahimNo ratings yet

- IELTS Letter Writing TaskDocument10 pagesIELTS Letter Writing TaskpragyaNo ratings yet

- Baga LanguageDocument2 pagesBaga LanguageMonahul Hristofor MocanuNo ratings yet

- Enseñanza de La Gramática: 1er SemestreDocument11 pagesEnseñanza de La Gramática: 1er SemestrePaulina MoyaNo ratings yet

- Interpreting PDFDocument28 pagesInterpreting PDFAndyNo ratings yet

- SubordinationDocument3 pagesSubordinationAna NosićNo ratings yet

- Descriptive WritingDocument8 pagesDescriptive Writingcorrnelia1No ratings yet

- Reading Skills 1. Read The Text. Choose The Best Heading For The TextDocument2 pagesReading Skills 1. Read The Text. Choose The Best Heading For The TextSanja BjelanovićNo ratings yet

- DLL - All Subjects 2 - Q2 - W7 - D1Document8 pagesDLL - All Subjects 2 - Q2 - W7 - D1BENITO LUMANAONo ratings yet

- IELTS Speaking Lesson 123Document46 pagesIELTS Speaking Lesson 123md shahidullahNo ratings yet

- Verb Tenses PDFDocument12 pagesVerb Tenses PDFHawraa HawraaNo ratings yet

- Impact Bre Foundation Lesson Planner Unit 1 1Document26 pagesImpact Bre Foundation Lesson Planner Unit 1 1Lucía Acuña BernyNo ratings yet

- Simple Past-29 Mayo 2017Document32 pagesSimple Past-29 Mayo 2017Anita de BorbonNo ratings yet

- Aappl Presentational RubricDocument1 pageAappl Presentational Rubricapi-505853151No ratings yet

- SHS Oc Q2 Module3 WK4-5Document8 pagesSHS Oc Q2 Module3 WK4-5Joniel Niño Hora BlawisNo ratings yet

- Nahw The Grammatical States PlaygroundDocument7 pagesNahw The Grammatical States Playgroundapi-3709915No ratings yet

- The C-V-C Spelling RuleDocument64 pagesThe C-V-C Spelling Ruledemiloc67% (3)

- Speakout 2e Pre Intermediate ContentsDocument2 pagesSpeakout 2e Pre Intermediate ContentsIngles DS100% (1)