Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Judicial Freview of Award

Judicial Freview of Award

Uploaded by

Hanu MittalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Judicial Freview of Award

Judicial Freview of Award

Uploaded by

Hanu MittalCopyright:

Available Formats

20 Finality of arbitral awards and

judicial review

Clive M Schmitthoff

The problem of judicial review

Arbitration is essentially a contractual system of dispute resolution. The

parties agree that their dispute, or any dispute which may arise between them

in the future, shall be settled by a private judge, the arbitrator, or a private

court, the arbitration tribunal. As a contractual arrangement, arbitration is, at

least in theory, governed by the principle of party autonomy. According to this

principle the parties are at liberty to make such arrangements as they like but,

as is well known, in all legal systems the principle of party autonomy is subject

to a great and growing number of qualifications. In English law, the principle

of freedom of contracting is not only limited by public policy considerations

but also by a host of mandatory statutory provisions, contained in enactments

such as the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977, the Consumer Credit Act 1974

and the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982.

In the law of arbitration, the principle of party autonomy postulates that the

award should be final and there should be no judicial review on its merits.

This, at least, is usually the intention of the parties. Provided that the

arbitration proceedings are conducted in accordance with the requirements of

natural justice, the parties are normally prepared to accept that the arbitrator

may err in his decision on a point of fact or law. After all, public judges may

also err, and the whole appellate hierarchy of the courts is founded on this

assumption and aims at eradicating any mistake which, in the opinion of the

higher judges, the trial judge may have made. But this process of rectifying a

judicial error is slow and costly. One of the great advantages of arbitration, in

the eyes of the business community, is that it eliminates this process. The

experienced or well advised businessman knows that the other advantages

claimed for arbitration over litigation, namely that it is cheaper or speedier, are

questionable. But parties preferring arbitration to litigation expect at least

fmality of the settlement of their dispute and avoidance of costly and lengthy

appellate proceedings. The state, on the other hand, has another interest. The

courts fear that the uniformity of the law is lost if they do not exercise some

kind of review over arbitrations, at least as far as questions of law are involved.

Atkin LJ (as he then was) justified the new obsolete 'case stated' procedure by

saying that, if the parties were allowed to oust the jurisdiction of the courts on

questions of law, 'the result might be that in time codes of law would come to

230 be administered in various trades differing substantially from the English

J. D. M. Lew (ed.), Contemporary Problems in International Arbitration

© Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 1987

Finality of arbitral awards and judicial review 231

mercantile law', 1 and one of the most eminent - and bluntest - commercial

judges of this country, Scrutton LJ, said, 'There must be no Alsatia in England

where the King's writ does not run.' 2 The conflicting views on the desirability

of fmality and the need for judicial review are the crucial issues in the

relationship between arbitration and the courts.

The two kinds of judicial review

Before this issue is examined it is necessary to defme what is understood by

'judicial review'.

There are, in fact, two kinds of judicial review and it is confusing and

misleading if they are not kept separate because they are entirely different in

character.

The first type of judicial review concerns the question whether the

requirements of natural justice were observed in the arbitration proceedings

and the arbitration agreement is valid under the law to which the parties have

subjected it. The second type of judicial review concerns the merits of the

award and here the issue is whether the arbitrator has fallen into an error.

These two types of judicial review will have to be examined later. It will be

seen that quite different considerations apply to them. A judicial review of the

first type is admitted by the courts of all countries because they consider it to be

within the contemplation of the parties when agreeing on arbitration. But the

judicial review of the second type, namely on the merits, is, as we shall see, a

more questionable affair.

Judicial review in transnational arbitrations

Before proceeding to a closer examination of these two types of judicial review,

it has to be considered whether any type of judicial review should be admitted

in transnational arbitrations.

This, of course, raises the question whether transnational arbitrations exist

at a1l 3 and also the wider question: what is transnational law? I have expressed

my understanding of this term in the following passage4 :

'It is ... wrong to attribute the character of international or supranational

law to international trade law. It acquires its autonomous character by leave

and licence of all national sovereigns. In character it is very different from

public international law. Ultimately it is founded on national law but has

be~n developed by international business in an area in which all national

1 In Czarnikow& Co v Roth, Schmidt & Co [1922]2 KB 478, 491; On the old 'case stated'

procedure, see CM Schmitthoff, 'Arbitration: The Supervisory Jurisdiction of the Court' in

[1967]JBL 318.

2 Ibid, at 488.

3 Delaume, 'L'arbitrage transnational et les tribunaux nationaux' HI Clunet 521 (1984); Sir

Michael Mustill, 'Transnational Arbitration in English Law, [1984] Current Legal Problems

133.

4 Clive M Schmitthoff, Commercial Law in a Changing Economic Climate, 2nd ed, London

1981, at 22.

You might also like

- Williams David - Defining The Role of The Court in Modern Intl Commercial Arbitration PDFDocument56 pagesWilliams David - Defining The Role of The Court in Modern Intl Commercial Arbitration PDFPooja MeenaNo ratings yet

- Workman Under Industrial Dispute ActDocument22 pagesWorkman Under Industrial Dispute ActHanu Mittal83% (6)

- Limits To Party Autonomy in International Commercial ArbitrationDocument13 pagesLimits To Party Autonomy in International Commercial ArbitrationdiannageneNo ratings yet

- Lew Mistelis Kroll Arbitration Chap01Document9 pagesLew Mistelis Kroll Arbitration Chap01Gabriela PieniakNo ratings yet

- Minimum Wagesd ActDocument17 pagesMinimum Wagesd ActHanu MittalNo ratings yet

- EXPLOITATION OF WORKERS and Diiferent PatternDocument13 pagesEXPLOITATION OF WORKERS and Diiferent PatternHanu Mittal100% (2)

- Big Questions, Little Answers Barbara GeddesDocument21 pagesBig Questions, Little Answers Barbara GeddesGustavo Garcia NitaNo ratings yet

- Winthrop Defense of An Order of CourtDocument2 pagesWinthrop Defense of An Order of CourtJasmine WangNo ratings yet

- Res JudicataDocument20 pagesRes Judicatasamuel mwangiNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction and Powers of Arbitral Award: Who DecidesDocument18 pagesJurisdiction and Powers of Arbitral Award: Who DecidesDerick HezronNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On International Commercial ArbitrationDocument13 pagesResearch Paper On International Commercial Arbitrationanon_911366681No ratings yet

- 12 - Chapter 3 PDFDocument28 pages12 - Chapter 3 PDFMaheshNo ratings yet

- #?JB ?% E V@9B?A C9 EAD C: %D Cef/ ") ') )Document5 pages#?JB ?% E V@9B?A C9 EAD C: %D Cef/ ") ') )Ishaan MundejaNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1715664 PDFDocument21 pagesSSRN Id1715664 PDFJudith BainomugisaNo ratings yet

- Arbitrating Competition Law DisputesDocument24 pagesArbitrating Competition Law DisputesPraneeth Sree KamujuNo ratings yet

- 12 - Chapter 5Document72 pages12 - Chapter 5VishakaRajNo ratings yet

- Lex Arbitri: Submitted ToDocument12 pagesLex Arbitri: Submitted ToLEX-57 the lex engine100% (1)

- IcaDocument6 pagesIcaAbhinavSinghNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument9 pagesReaction Paperarajara16No ratings yet

- ICA SynopsisDocument4 pagesICA SynopsisArpit GoyalNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of Adr ActDocument8 pagesSalient Features of Adr ActLhai Tabajonda-Mallillin0% (1)

- 07 - Chapter 4Document68 pages07 - Chapter 4adv.varshasharmaaNo ratings yet

- Amicable Dispute Resolution in Civil and CommerciaDocument30 pagesAmicable Dispute Resolution in Civil and Commerciakiyamenge7No ratings yet

- Loopholes in ACADocument16 pagesLoopholes in ACAKriti ParasharNo ratings yet

- Role of Courts in ArbitrationDocument23 pagesRole of Courts in ArbitrationAkanksha Singh0% (1)

- Essay On Conflict of Laws - Part IIDocument4 pagesEssay On Conflict of Laws - Part IIAldrinmarkquintanaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 5Document5 pagesAssignment 5Adhara SalfarlieNo ratings yet

- A Second Look at ArbitrabilityDocument37 pagesA Second Look at ArbitrabilitylulakrynskiNo ratings yet

- Scope of Arbitrability in International Commercial ArbitrationDocument10 pagesScope of Arbitrability in International Commercial ArbitrationAnanya DasNo ratings yet

- Land LawDocument13 pagesLand Lawroopam singhNo ratings yet

- 4) Civil Procedure Code: Salient FeaturesDocument6 pages4) Civil Procedure Code: Salient FeaturesRahul ChhabraNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument3 pagesIntroductionPrishu SharmaNo ratings yet

- Administrator,+unblj v60 Forum02Document23 pagesAdministrator,+unblj v60 Forum02VAISHNAVI RASTOGI 19113047No ratings yet

- Arbitration As An ADR Mechanism: The Civil Procedure Code (Amendment) Act, 1999 Carries Section 89Document19 pagesArbitration As An ADR Mechanism: The Civil Procedure Code (Amendment) Act, 1999 Carries Section 89Ayush SharmaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment: Subject: Law On Comercial ArbitrationDocument9 pagesFinal Assignment: Subject: Law On Comercial ArbitrationThảo NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Brief History and Origin of Res JudicataDocument12 pagesBrief History and Origin of Res JudicataSonali betkarNo ratings yet

- Public International Law ProjectDocument10 pagesPublic International Law ProjectJenniferNo ratings yet

- Delocalization in International Commercial Arbitration: Facta UniversitatisDocument9 pagesDelocalization in International Commercial Arbitration: Facta UniversitatisPlannerNo ratings yet

- SCA Rushton 2009 02Document11 pagesSCA Rushton 2009 02firthousiyaNo ratings yet

- Role of Arbitrator in Settlement of DisputesDocument12 pagesRole of Arbitrator in Settlement of Disputesadv_animeshkumarNo ratings yet

- 872-Texto Del Artículo-2419-1-10-20131008Document15 pages872-Texto Del Artículo-2419-1-10-20131008Thảo NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws 2022-2023Document18 pagesConflict of Laws 2022-2023Uchechukwu KaluNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Law - Proper Law of ContractDocument31 pagesConflict of Law - Proper Law of ContractRachit Munjal100% (1)

- Attachment of DecreeDocument15 pagesAttachment of DecreeHrishika Netam100% (1)

- Au Meng Nam & Anor V Ung Yak Chew & Ors2007Document62 pagesAu Meng Nam & Anor V Ung Yak Chew & Ors2007Muhammad NajmiNo ratings yet

- Civil Code Provisions On Adr Final ReportDocument13 pagesCivil Code Provisions On Adr Final Reportmae krisnalyn niezNo ratings yet

- Report of Chapter 3 - Redfern and HunterDocument9 pagesReport of Chapter 3 - Redfern and HunterLucas Vasconcelos de LimaNo ratings yet

- Offence May Be The Best Defence For The Jurisdiction of International ArbitrationsDocument5 pagesOffence May Be The Best Defence For The Jurisdiction of International ArbitrationsThomas G. HeintzmanNo ratings yet

- The Law Governing The Arbitration Agreement - Why We Need It and How To Deal With It - International Bar AssociationDocument4 pagesThe Law Governing The Arbitration Agreement - Why We Need It and How To Deal With It - International Bar AssociationKaran BhardwajNo ratings yet

- 04 - Chapter 1Document30 pages04 - Chapter 1adv.varshasharmaaNo ratings yet

- Hasegawa Vs KitamuraDocument4 pagesHasegawa Vs KitamuraJupiterNo ratings yet

- KAZUHIRO HASEGAWA and NIPPON ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS CODocument5 pagesKAZUHIRO HASEGAWA and NIPPON ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS CORon AceNo ratings yet

- Kazuhiro Hasegawa Vs KitamuraDocument5 pagesKazuhiro Hasegawa Vs KitamuraMi-young Sun100% (2)

- ADR Notes - Final - 1Document40 pagesADR Notes - Final - 1AmrutaNo ratings yet

- Arbi - Unit 01 - LLB3Document16 pagesArbi - Unit 01 - LLB3meenakshi kaurNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Law For ArbitratorsDocument17 pagesConflict of Law For ArbitratorsJovana Poppy GolubovićNo ratings yet

- Grounds For Review (3) : Procedural Impropriety: Aims and ObjectivesDocument14 pagesGrounds For Review (3) : Procedural Impropriety: Aims and Objectivesmohamm3dNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To International Commercial Arbitration FinalDocument17 pagesAn Introduction To International Commercial Arbitration Finalarihant_219160175100% (1)

- Emmert-IBTChap10 0DisputeSettlementDocument130 pagesEmmert-IBTChap10 0DisputeSettlementZviagin & CoNo ratings yet

- Private International LawDocument14 pagesPrivate International LawBoikobo MosekiNo ratings yet

- People - v. - Rosenthal20210424-14-Q22osaDocument17 pagesPeople - v. - Rosenthal20210424-14-Q22osaVee ManahanNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Procedural Issues in International ArbitrationDocument13 pagesA Guide To Procedural Issues in International Arbitrationabuzar ranaNo ratings yet

- Courts and Procedure in England and in New JerseyFrom EverandCourts and Procedure in England and in New JerseyNo ratings yet

- Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India and OthersDocument14 pagesBandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India and OthersHanu Mittal100% (1)

- Exploitation of Labour and Its PatternDocument13 pagesExploitation of Labour and Its PatternHanu Mittal100% (1)

- Method of Settlment of Industrial DisputeDocument27 pagesMethod of Settlment of Industrial DisputeHanu MittalNo ratings yet

- Project Report: Industrial TribunalDocument15 pagesProject Report: Industrial TribunalHanu MittalNo ratings yet

- Project Report On: Submitted To: Submitted byDocument15 pagesProject Report On: Submitted To: Submitted byHanu MittalNo ratings yet

- Arbitration and Commencement of AwardDocument17 pagesArbitration and Commencement of AwardHanu MittalNo ratings yet

- Labour Laws and Industrial Laws: A Project Report OnDocument14 pagesLabour Laws and Industrial Laws: A Project Report OnHanu Mittal100% (3)

- FORENSIC Science ProjectDocument15 pagesFORENSIC Science ProjectHanu Mittal100% (4)

- Moot Diary oDocument17 pagesMoot Diary oHanu MittalNo ratings yet

- Steel Authority of India LTDDocument13 pagesSteel Authority of India LTDHanu Mittal100% (1)

- Project Report On: Application For Grant of Compensation Under Section 166 of Motor Vehical Act, 1988Document16 pagesProject Report On: Application For Grant of Compensation Under Section 166 of Motor Vehical Act, 1988Hanu MittalNo ratings yet

- Internation Human RightDocument16 pagesInternation Human RightHanu MittalNo ratings yet

- Tendernotice 1Document42 pagesTendernotice 1Hanu MittalNo ratings yet

- The Path Not Taken G. M. SyedDocument214 pagesThe Path Not Taken G. M. SyedSani Panhwar75% (4)

- Vulnerable Groups: Arsalan Ahmad B.A.LL.B 5 Semester Self Finance Human Rights Assignment Roll No. - 09Document12 pagesVulnerable Groups: Arsalan Ahmad B.A.LL.B 5 Semester Self Finance Human Rights Assignment Roll No. - 09Arsalan AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Masonic OathDocument1 pageThe Masonic OathBálint FodorNo ratings yet

- Leonard Wood As Governor General-A Calendar of Selected CorrespondenceDocument22 pagesLeonard Wood As Governor General-A Calendar of Selected CorrespondenceTaliNo ratings yet

- PPT-Nature, Form, Elements of SaleDocument68 pagesPPT-Nature, Form, Elements of SaleRonah Abigail BejocNo ratings yet

- Opportunities For Sri Lankan Tea in PakistanDocument21 pagesOpportunities For Sri Lankan Tea in PakistanV Lotus HbkNo ratings yet

- USA V Binance Plea AgreementDocument10 pagesUSA V Binance Plea AgreementFile 411No ratings yet

- Riminology Ynopsis: P: Iv TDocument3 pagesRiminology Ynopsis: P: Iv TSiddhant BarmateNo ratings yet

- Hale Vs HenkelDocument25 pagesHale Vs Henkelsolution4theinnocent100% (2)

- Short-Term Rental RegulationsDocument7 pagesShort-Term Rental RegulationsiBerkshires.comNo ratings yet

- Jungle MajorDocument8 pagesJungle MajorWith Love From KashmirNo ratings yet

- 5HR02 - Talent Management and Workforce PlanningDocument17 pages5HR02 - Talent Management and Workforce Planningraranft0319No ratings yet

- 01/22/21 - Gideon's Army Weekly Conference Call Saturday 9 Am CST For American Political PrisonersDocument26 pages01/22/21 - Gideon's Army Weekly Conference Call Saturday 9 Am CST For American Political PrisonersLoneStar1776No ratings yet

- Miller v. Canales - ComplaintDocument13 pagesMiller v. Canales - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Daily Diary - Ojt - 62 - ProbationersDocument98 pagesDaily Diary - Ojt - 62 - Probationersmsnethrapal100% (1)

- German V Barangan G.R. No. 68828. March 27, 1985Document3 pagesGerman V Barangan G.R. No. 68828. March 27, 1985MWinbee VisitacionNo ratings yet

- Social Work in Canada An Introduction Third EditionDocument34 pagesSocial Work in Canada An Introduction Third EditionTimothy MolloyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1, 2 and 3 (History) Bls LLB: Chapter No. 1 East India Company and Its Administration (1757 - 1857)Document17 pagesChapter 1, 2 and 3 (History) Bls LLB: Chapter No. 1 East India Company and Its Administration (1757 - 1857)SANTOSH CHAUHANNo ratings yet

- Authorization FormDocument1 pageAuthorization Formdesecih806No ratings yet

- Aecom Code of Conduct ENGLISHDocument47 pagesAecom Code of Conduct ENGLISHashwinNo ratings yet

- The ABCs of JAMVAT - 0Document5 pagesThe ABCs of JAMVAT - 0SageNo ratings yet

- Note Summary Step 1: Meaning of LegislatureDocument4 pagesNote Summary Step 1: Meaning of LegislaturemarcusfunmanNo ratings yet

- Writing Task 2 VocabularyDocument3 pagesWriting Task 2 VocabularyDuy DươngNo ratings yet

- Practicum LogDocument3 pagesPracticum Logapi-659774512No ratings yet

- The Oriental Insurance Company Limited: Particulars of Insured VehicleDocument3 pagesThe Oriental Insurance Company Limited: Particulars of Insured VehiclehancyboxNo ratings yet

- Magdaraog Ass3econDocument8 pagesMagdaraog Ass3econDanielle Aubrey TerencioNo ratings yet

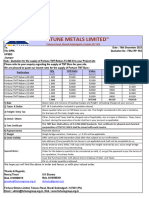

- "Fortune Metals Limited": Talwara Road, Mandi Gobindgarh, Punjab-147 301Document1 page"Fortune Metals Limited": Talwara Road, Mandi Gobindgarh, Punjab-147 301S K SharmaNo ratings yet

- Nunavut Court Sentencing Judgment On David LytaDocument5 pagesNunavut Court Sentencing Judgment On David LytaNunatsiaqNewsNo ratings yet