Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History 35

History 35

Uploaded by

nicolearetano4170 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views4 pagesIn the early 18th century, bronze lined pasta presses with metal pistons and copper dies were used to knead and compress dough into chambers and force it out through the dies. By the late 19th century, steam and hydraulic powered machines were used but the press design slowed production. In 1922, a continuous screw was developed for a French factory, improving efficiency. This technology is still used today. Further innovations led to automatic mixing, kneading and forming machines in the 1930s, though drying remained separate. Drying is critical but difficult, though multi-stage drying methods improved industrial production starting in the early 20th century.

Original Description:

Notes

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIn the early 18th century, bronze lined pasta presses with metal pistons and copper dies were used to knead and compress dough into chambers and force it out through the dies. By the late 19th century, steam and hydraulic powered machines were used but the press design slowed production. In 1922, a continuous screw was developed for a French factory, improving efficiency. This technology is still used today. Further innovations led to automatic mixing, kneading and forming machines in the 1930s, though drying remained separate. Drying is critical but difficult, though multi-stage drying methods improved industrial production starting in the early 20th century.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views4 pagesHistory 35

History 35

Uploaded by

nicolearetano417In the early 18th century, bronze lined pasta presses with metal pistons and copper dies were used to knead and compress dough into chambers and force it out through the dies. By the late 19th century, steam and hydraulic powered machines were used but the press design slowed production. In 1922, a continuous screw was developed for a French factory, improving efficiency. This technology is still used today. Further innovations led to automatic mixing, kneading and forming machines in the 1930s, though drying remained separate. Drying is critical but difficult, though multi-stage drying methods improved industrial production starting in the early 20th century.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 4

In the beginning of the eighteenth century, the inside of

the compression chamber was lined with bronze; the piston

was made of metal and the die of copper. The piston

packed

the kneaded dough into the compression chamber and

further kneaded and forced it out through the die. By the

end of the nineteenth century, steam- and hydraulic-

powered machines were used to make pasta, but the press

continued to be a barrier to speed and efficiency because it

required the drawing out of the piston to repack the

chamber after each batch of dough

was pushed through. In 1922 Ferréol Sandragné built an end-

less screw (or worm) that advanced dough continuously for

the Grands Moulins de Corbeil pasta factory in Toulouse,

France. This technology is notably one of the mainstays of

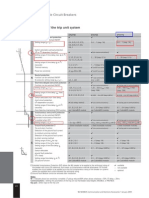

Wooden pasta press from the Barilla Pasta Museum.

manufacturing processes today and is used not only for

making foods for humans and animals, but for making

other products such as pellets for the plastics industry.

This concept was

improved upon several times and in 1933 the Milanese

company

M. & G. Braibanti launched the first generation of an

industrial pasta-making press that was capable of

automatically and con- tinuously mixing, kneading and

forming. Just four years later, Braibanti integrated an

assembly of machines for the synchron- ized continuous

production of pasta, including the proportioning of

ingredients, mixing, kneading and forming. Drying was the

only process not integrated. The line was presented at the

Fair of Milan in 1937 and Buhler of Switzerland subsequently

commercialized automatic pasta-making, except for drying.

Drying is the most sensitive phase of the entire pasta-

making process and the pasta makers guarded this

4

knowledge zealously to protect their trade. Neapolitan

pasta maintained supremacy for as long as the drying was

natural. That the region around Naples was uniquely

endowed with a climate that suited pasta makers was

realized only when other regions tried to adopt industrial

pasta production. The alternating warm, humid scirocco and

the dry, cool tramontana favoured the complex and delicate

process of drying and it rarely took more than ten days to

dry even the bulkiest forms of pasta. Industrial production

of pasta in other regions struggled with drying, which was

labour-intensive and risky because of its suscept- ibility to

souring, mildew, fermentation and other damages. Machine

tool companies and pasta manufacturers experi- mented

with different types of artificial drying methods; the

economical benefits of mechanized drying was apparent

from the twenty or so patents filed between 1875 and 1904.

The Milanese industrialist Vitaliano Tommasini made the

important

contribution of drying pasta in three stages, a concept

seminal to all future dryers. Artificial drying soon became

the de facto

You might also like

- Apple Pay Payment Method GuideDocument4 pagesApple Pay Payment Method GuideMahadevan Venkatesan100% (1)

- Test2-Reading Passage 1Document2 pagesTest2-Reading Passage 1vanpham248No ratings yet

- A750-A761E VacTestLocationsDocument5 pagesA750-A761E VacTestLocationsPedroMecanico100% (5)

- Salesgram: Cat Motor Grader Blade ForcesDocument4 pagesSalesgram: Cat Motor Grader Blade ForcesVictorDjChiqueCastilloNo ratings yet

- Mido History enDocument4 pagesMido History enRobertIonicaNo ratings yet

- Reference Book of Textile Technologies - Manmade FibersDocument75 pagesReference Book of Textile Technologies - Manmade FibersfernandoribeiromocNo ratings yet

- The Industrial Revolution in EuropeDocument3 pagesThe Industrial Revolution in EuropeSouhila AbidNo ratings yet

- Social Change: Textile Mill Workers. Spinning Machinery. Macon, Georgia, 1909Document12 pagesSocial Change: Textile Mill Workers. Spinning Machinery. Macon, Georgia, 1909InAm MaliCkNo ratings yet

- Industrial RevolutionDocument6 pagesIndustrial RevolutionInduwara AdeeshanaNo ratings yet

- History, CH-5 G-X - The Age of IndustrializationDocument16 pagesHistory, CH-5 G-X - The Age of IndustrializationSavageDD GamingNo ratings yet

- Textile - Reference Book For Man Made FibersDocument73 pagesTextile - Reference Book For Man Made Fibersviswa5263100% (6)

- Evolutionary History of KnittingDocument3 pagesEvolutionary History of KnittingScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Baking Historical BackgroundDocument5 pagesBaking Historical Backgroundnovny andryaniNo ratings yet

- 07 The Industrial RevolutionDocument3 pages07 The Industrial RevolutionHeidy Teresa MoralesNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Industrial RevolutionDocument14 pagesIntroduction To The Industrial RevolutionMartina CalcaterraNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument13 pagesUntitled DocumentnirikdhaNo ratings yet

- The Age of IndustrialisationDocument15 pagesThe Age of Industrialisationthinkiit100% (1)

- CBSE Class 10 Revision Notes On History Chapter 4 - The Age of IndustrialisationDocument7 pagesCBSE Class 10 Revision Notes On History Chapter 4 - The Age of IndustrialisationPari SinghNo ratings yet

- YT - Age of Industrialization Full ChapterDocument124 pagesYT - Age of Industrialization Full ChapterPrabhnoor kaurNo ratings yet

- La Revoloucion IndustrialDocument5 pagesLa Revoloucion IndustrialESTELA ORÚS FALGÁSNo ratings yet

- Questions and Answers 1st Part Unit 4-Industrial Revolution Copia 2Document5 pagesQuestions and Answers 1st Part Unit 4-Industrial Revolution Copia 2alejandra.menmigNo ratings yet

- Prelim HandoutDocument14 pagesPrelim Handoutsammy lopezNo ratings yet

- Invention After Industrial RevolutionDocument5 pagesInvention After Industrial Revolutiondipikathakare5112010No ratings yet

- 20 ChapteroutlineDocument11 pages20 ChapteroutlineJames BrownNo ratings yet

- The Beginnings of Industrialization: Key Terms and PeopleDocument3 pagesThe Beginnings of Industrialization: Key Terms and PeopleUtziieNo ratings yet

- IET Brochure - ENGLISHDocument12 pagesIET Brochure - ENGLISHmohamed kassemNo ratings yet

- Textile Industry HistoryDocument15 pagesTextile Industry HistorycircacircleNo ratings yet

- The Age of Industrialisation - NotesDocument14 pagesThe Age of Industrialisation - NotesPuja BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Essay On Engineers in Society.Document2 pagesEssay On Engineers in Society.Siti RaudahNo ratings yet

- La Revoloucion IndustrialDocument5 pagesLa Revoloucion IndustrialESTELA ORÚS FALGÁSNo ratings yet

- The Industrial Revolution: Case StudyDocument15 pagesThe Industrial Revolution: Case StudyAndrés Tallón CastroNo ratings yet

- Textile Evolution: From Nylons To FuselageDocument37 pagesTextile Evolution: From Nylons To FuselageKate BondNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Industrial Revolution & French, Russian Revolution?Document10 pagesDifference Between Industrial Revolution & French, Russian Revolution?Anonymous 3owUL0ksVNo ratings yet

- Production BusinessDocument15 pagesProduction BusinessShaila ShamNo ratings yet

- The Age of Industrialisation: Important TermsDocument15 pagesThe Age of Industrialisation: Important TermsPravinBhaveNo ratings yet

- History ProjectDocument14 pagesHistory Projectvaghelashweta92No ratings yet

- Key Elements of IndustrialisationDocument4 pagesKey Elements of IndustrialisationSara AlgoraNo ratings yet

- Tyre HistoryDocument34 pagesTyre HistoryTrường Trường XuânNo ratings yet

- History Grade 8 Topic 1: The Industrial Revolution in Britain and Southern Africa From 1860Document95 pagesHistory Grade 8 Topic 1: The Industrial Revolution in Britain and Southern Africa From 1860TooniNo ratings yet

- Prerequisites For The Industrial RevolutionDocument3 pagesPrerequisites For The Industrial RevolutionSonya BladeNo ratings yet

- STS ReviewerDocument4 pagesSTS ReviewerFashiel JuguilonNo ratings yet

- Industrial RevolutionDocument10 pagesIndustrial Revolutionchinar_imran_newNo ratings yet

- Ntse Social Science - The Age of IndustrialisationDocument7 pagesNtse Social Science - The Age of IndustrialisationMohitNo ratings yet

- Unit-6 Patterns of Industrialisation PDFDocument12 pagesUnit-6 Patterns of Industrialisation PDFNavdeep SinghNo ratings yet

- TVL IA EP10 Week7Document4 pagesTVL IA EP10 Week7Erlyn AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- INDUSTRY PROFILE - OcrimDocument4 pagesINDUSTRY PROFILE - OcrimMilling and Grain magazineNo ratings yet

- About French Food: Name: Humaidy Nur Saidy, NIM: F051171507Document6 pagesAbout French Food: Name: Humaidy Nur Saidy, NIM: F051171507Humaidy Nur SaidyNo ratings yet

- Jess 304Document38 pagesJess 304DAKSH SACHDEVNo ratings yet

- Brit Civ Lesson 2 Oct 2023Document4 pagesBrit Civ Lesson 2 Oct 2023mohamedabdesselembecharef879No ratings yet

- Proses Pembuatan Tepung TeriguDocument17 pagesProses Pembuatan Tepung TeriguSilvy VeronicaNo ratings yet

- History of Economics Notes - BocconiDocument30 pagesHistory of Economics Notes - BocconiGeorge KolbaiaNo ratings yet

- Baker YeastDocument28 pagesBaker YeastVũ Quốc Việt0% (1)

- Financial Management1Document28 pagesFinancial Management1irfanahmed.dbaNo ratings yet

- The Beginnings of IndustrializationDocument3 pagesThe Beginnings of Industrializationyochoa1No ratings yet

- Kens Notes Session 4Document16 pagesKens Notes Session 4Lê NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Class 10 History CHP 4 NotesDocument19 pagesClass 10 History CHP 4 Noteskannan.nivedNo ratings yet

- Lesson 04Document25 pagesLesson 04Prithviraj MishraNo ratings yet

- Skjermbilde 2023-06-03 Kl. 19.32.51 (20 Files Merged)Document32 pagesSkjermbilde 2023-06-03 Kl. 19.32.51 (20 Files Merged)JohanneNo ratings yet

- From Ancient Concrete To Geopolymers: Geopolymer InstituteDocument6 pagesFrom Ancient Concrete To Geopolymers: Geopolymer InstituteMithun BMNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Shoe Factory EngineeringFrom EverandHandbook of Shoe Factory EngineeringRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Industrial Revolution: Investigate How Science and Technology Changed the World with 25 ProjectsFrom EverandThe Industrial Revolution: Investigate How Science and Technology Changed the World with 25 ProjectsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Combined Impact and Attrition MethodDocument7 pagesCombined Impact and Attrition MethodBernadette Beltran33% (3)

- TirangaDocument1 pageTirangasurajraj0457No ratings yet

- Calling EPANET From MatlabDocument9 pagesCalling EPANET From Matlabmarting69No ratings yet

- Storage Tank ErectionDocument20 pagesStorage Tank ErectionMohamed RizwanNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry Genius UncoveredDocument2 pagesBiochemistry Genius UncoveredstanscimagNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Flotation TestingDocument19 pagesLaboratory Flotation Testingwilfredo trujillo100% (1)

- Master SetDocument624 pagesMaster SetEr Lokesh MahorNo ratings yet

- Edc BJT CeDocument5 pagesEdc BJT CeRavi JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Physics Exit 3q1718 .Document16 pagesPhysics Exit 3q1718 .Mikaella Tambis0% (1)

- Quotation For Commerical IP68 Grade LED String Light 2022Document5 pagesQuotation For Commerical IP68 Grade LED String Light 2022George RotaruNo ratings yet

- XLRIMandatory DisclosureDocument56 pagesXLRIMandatory DisclosureSUDEVJYOTHISINo ratings yet

- How To Use Easy Petty Cash in Ten MinutesDocument5 pagesHow To Use Easy Petty Cash in Ten MinutesmunideomiaNo ratings yet

- GTH4013SX Parts ManualDocument226 pagesGTH4013SX Parts ManualheniNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Research and Title ProposalDocument34 pagesIntroduction To Research and Title ProposalDave Matthew Campillos (Vilgacs)No ratings yet

- Updated Release and Due Submission ScheduleDocument1 pageUpdated Release and Due Submission ScheduleLorenzo R. BelardoNo ratings yet

- DSR - Dec. 26, 2022 - Jan. 8, 2023Document6 pagesDSR - Dec. 26, 2022 - Jan. 8, 2023BuenafeNo ratings yet

- BHIM TrainingDocument28 pagesBHIM TrainingVikas Singh SisodiaNo ratings yet

- Cork Chamber - Chamberlink (Nov 2013)Document24 pagesCork Chamber - Chamberlink (Nov 2013)Imelda V. MulcahyNo ratings yet

- TM Forum Input To ONAP Modeling Workshop 2017-12-14Document20 pagesTM Forum Input To ONAP Modeling Workshop 2017-12-14Rajiv100% (1)

- ETU 776 TripDocument1 pageETU 776 TripbhaskarinvuNo ratings yet

- ExperienceswithCommissioning HV CablesDocument20 pagesExperienceswithCommissioning HV CablesafwdNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word - Deployment Diagram - An - An IntroductionDocument6 pagesMicrosoft Word - Deployment Diagram - An - An IntroductionChandra MohanNo ratings yet

- Technical Offer From Thermax On 13.05.10Document32 pagesTechnical Offer From Thermax On 13.05.10venka07100% (1)

- AP CHHGH Full Final ListDocument23 pagesAP CHHGH Full Final ListYakshit JainNo ratings yet

- 1783-td001 - En-P - Switch Stratix PDFDocument58 pages1783-td001 - En-P - Switch Stratix PDFJuan Erwin Ccahuay HuamaniNo ratings yet

- Hydrogenerators: Transforming Energy Into SolutionsDocument8 pagesHydrogenerators: Transforming Energy Into Solutionsshcoway100% (1)

- Technology Enabled Solutions To Grow Your Business: Abuja: 5th Floor, IGI HouseDocument17 pagesTechnology Enabled Solutions To Grow Your Business: Abuja: 5th Floor, IGI HouseOyaje IdokoNo ratings yet