Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ireland 2017

Ireland 2017

Uploaded by

Hòa HồCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Joint InfectionsDocument10 pagesJoint InfectionsJPNo ratings yet

- Hesi Practice ExamDocument14 pagesHesi Practice ExamYieNo ratings yet

- BJOG 2014 GBS Và PROMDocument10 pagesBJOG 2014 GBS Và PROMHòa HồNo ratings yet

- Interstitial Collagen Synthesis and Processing in Human Amnion: A Property of The Mesenchymal Cells'Document8 pagesInterstitial Collagen Synthesis and Processing in Human Amnion: A Property of The Mesenchymal Cells'Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- An Autocrine/Paracrine Role of Human Decidual Relaxin. II. Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) and Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1)Document9 pagesAn Autocrine/Paracrine Role of Human Decidual Relaxin. II. Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) and Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1)Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics For Preterm Rupture of Membranes (Review) : Kenyon S, Boulvain M, Neilson JPDocument36 pagesAntibiotics For Preterm Rupture of Membranes (Review) : Kenyon S, Boulvain M, Neilson JPHòa HồNo ratings yet

- Biolreprod 0772Document7 pagesBiolreprod 0772Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Katsura 1989Document4 pagesKatsura 1989Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Jcem 2244Document7 pagesJcem 2244Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Cases With Ruptured Membranes That "Reseal": Gainesville, FloridaDocument7 pagesCases With Ruptured Membranes That "Reseal": Gainesville, FloridaHòa HồNo ratings yet

- Alexander 1999Document5 pagesAlexander 1999Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Alger 1988Document8 pagesAlger 1988Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- AmniSure ROM Test Instructions For Use (2019)Document1 pageAmniSure ROM Test Instructions For Use (2019)Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Hafiz Zaid MahmoodDocument1 pageHafiz Zaid MahmoodraomuhammdshahzadNo ratings yet

- NCP FinalDocument7 pagesNCP FinalRuss RussNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Athletic TrainingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics Athletic Traininggz7vxzyz100% (1)

- Alergi 1Document7 pagesAlergi 1illaNo ratings yet

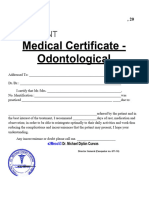

- Dental Medical CertificateDocument1 pageDental Medical CertificateScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Gordons Eleven Funcional AreasDocument2 pagesGordons Eleven Funcional Areasblue_kitten14No ratings yet

- Financial Difficulties Faced by University StudentsDocument7 pagesFinancial Difficulties Faced by University StudentsMuhammad Mazhar BashirNo ratings yet

- CH62 Management of Differentiated Thyroid CancerDocument52 pagesCH62 Management of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer許懷朔No ratings yet

- Health-7 Q4 LAS Week6-7Document12 pagesHealth-7 Q4 LAS Week6-7Reque RadomesNo ratings yet

- Passi City College City of Passi, Iloilo: School of Criminal JusticeDocument15 pagesPassi City College City of Passi, Iloilo: School of Criminal JusticeKenneth P PablicoNo ratings yet

- Newborn Infant Hearing Screening DMIMSUDocument12 pagesNewborn Infant Hearing Screening DMIMSUSharnie JoNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Basis of Professional Nursing. BOPN317 Dorothea Orem'S Theory of NursingDocument45 pagesTheoretical Basis of Professional Nursing. BOPN317 Dorothea Orem'S Theory of Nursinggideon A. owusuNo ratings yet

- Overview of PHNDocument14 pagesOverview of PHNariel camusNo ratings yet

- Student ProfileDocument4 pagesStudent ProfileJomark OrpillaNo ratings yet

- Human Capital NcertDocument17 pagesHuman Capital NcertYuvika BishnoiNo ratings yet

- Apa Template UvariDocument10 pagesApa Template Uvariapi-507327723No ratings yet

- Volume of DistributionDocument11 pagesVolume of DistributionDr. Mushfique Imtiaz ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Bacterial InfectionDocument122 pagesBacterial InfectionElga MuralidharanNo ratings yet

- Healthy EatingDocument24 pagesHealthy EatingDr. Jayesh Patidar100% (1)

- Renal Management in The Critically Ill PatientDocument16 pagesRenal Management in The Critically Ill PatientAbygail RHNo ratings yet

- Department of Biochemistry, Major S D Singh Medical College & Hospital, Fatehgarh (U.P.), India Tel: 7607879471Document15 pagesDepartment of Biochemistry, Major S D Singh Medical College & Hospital, Fatehgarh (U.P.), India Tel: 7607879471marioNo ratings yet

- Cornwall & Isles of Scilly LMC Newsletter Dec 2013Document8 pagesCornwall & Isles of Scilly LMC Newsletter Dec 2013Cornwall and Isles of Scilly LMCNo ratings yet

- OBE - Syllabus - Psych 109 Abnormal PsychologyDocument15 pagesOBE - Syllabus - Psych 109 Abnormal PsychologySharrah Laine AlivioNo ratings yet

- Blood LettingDocument23 pagesBlood LettingNars Akoh100% (1)

- Current Epidemiology Studie Critical ReviewDocument10 pagesCurrent Epidemiology Studie Critical ReviewMarvin ItolondoNo ratings yet

- Th1 - Th2 Dominance SymptomsList PDFDocument3 pagesTh1 - Th2 Dominance SymptomsList PDFPetra JobovaNo ratings yet

- Proton TherapyDocument21 pagesProton Therapytrieu leNo ratings yet

- DGJKHVDocument7 pagesDGJKHVGILIANNE MARIE JIMENEANo ratings yet

Ireland 2017

Ireland 2017

Uploaded by

Hòa HồOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ireland 2017

Ireland 2017

Uploaded by

Hòa HồCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Research

Incidence and Timing of Thromboembolic

Events in Patients With Ovarian Cancer

Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Patricia S. Greco, MD, Ali A. Bazzi, MD, Karen McLean, MD, PhD, R. Kevin Reynolds, MD,

Ryan J. Spencer, MD, Carolyn M. Johnston, MD, J. Rebecca Liu, MD, and Shitanshu Uppal, MBBS

OBJECTIVE: To identify the incidence and timing of venous therapy, six (5.4%, 95% CI 2.4–11.5%) developed a

thromboembolism as well as any associated risk factors in postoperative venous thromboembolism, and 11

patients with ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal (9.9%, 95% CI 5.5–17%) developed a venous thrombo-

cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. embolism during adjuvant chemotherapy. Two of the

METHODS: We conducted a retrospective cohort study four patients with clear cell histology developed

of patients diagnosed with ovarian, fallopian tube, and a venous thromboembolism in this cohort.

primary peritoneal cancer and receiving neoadjuvant CONCLUSION: Overall new diagnosis of venous throm-

chemotherapy from January 2009 to May 2014 at a single boembolism was associated with one fourth of the

academic institution. The timing and number of venous patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for

thromboembolic events for the entire cohort were ovarian cancer with nearly half of these diagnosed during

categorized as follows: presenting symptom, during chemotherapy cycles before interval debulking surgery.

neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment, after debulking Efforts to reduce venous thromboembolism so far have

surgery, and during adjuvant chemotherapy. largely focused on the postoperative period. Additional

RESULTS: Of the 125 total patients with ovarian cancer attention to venous thromboembolic prophylaxis during

undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 13 of 125 pa- chemotherapy (neoadjuvant and adjuvant) in this patient

tients (10.4%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 6.1–17.2%) population is warranted in an effort to decrease the rates

had a venous thromboembolism as a presenting symp- of venous thromboembolism.

tom and were excluded from further analysis. Of the 112 (Obstet Gynecol 2017;0:1–7)

total patients at risk, 30 (26.8%, 95% CI 19.3–35.9%) DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001980

experienced a venous thromboembolism. Based on the

P

phase of care, 13 (11.6%, 95% CI 6.8–19.1%) experienced atients with ovarian cancer have a 10–22% incidence

a venous thromboembolism during neoadjuvant chemo- of venous thromboembolism.1,2 Previously identi-

fied risk factors include obesity, age older than 65 years,

See related editorial on page 971.

histology, advanced stage, CA 125 greater than 500,

debulking surgery, and the use of antiangiogenic

From the Division of Gynecologic Oncology and the Institute for Healthcare agents.1,2 Thromboembolism in malignancy is also asso-

Policy and Innovation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and the Department

of Obstetrics and Gynecology, St. John Hospital, Detroit, Michigan; and the ciated with lower survival and poor quality of life.3,4 It is

Division of Gynecologic Oncology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin. unclear whether venous thromboembolism is causally

Presented as a poster at the Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, Society of related to a reduction in overall survival or reflects

Gynecologic Oncology, March 19–22, 2016, San Diego, California. a higher tumor burden, more aggressive tumor biology,

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for or both. Nevertheless, preventing thromboembolism is

authorship.

of paramount importance to avoid short- and long-term

Corresponding author: Shitanshu Uppal, MBBS, University of Michigan, 1500 complications. In addition to the perioperative thrombo-

E Medical Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; email: uppal@med.umich.edu.

embolic prophylaxis, prolonged prophylaxis is becom-

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

ing a standard of care in women with ovarian cancer.

Recent studies show decreased thromboembolic events

© 2017 by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Published

by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. in patients receiving prolonged postoperative prophy-

ISSN: 0029-7844/17 laxis for 4 weeks.5,6

VOL. 0, NO. 0, MONTH 2017 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY 1

Copyright Ó by The American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

However, studies have shown a continued risk of surgery were considered as undergoing neoadjuvant

venous thromboembolic events well beyond the chemotherapy and were included in this report.

perioperative and prolonged prophylaxis periods. Patients seeking a second opinion or those who

During adjuvant chemotherapy, venous thromboem- underwent surgery at the University of Michigan but

bolism occurs in up to 12.5% of the patients.7 These received chemotherapy elsewhere were not included

data suggest that active ovarian cancer is a hypercoag- as a result of concerns of incomplete follow-up and

ulable state. Despite multiple studies examining the limited access to detailed medical records from outside

perioperative and postoperative phases of care in hospitals. For this study, we categorized age as younger

women with ovarian cancer, the rates of thromboem- than 65 years or 65 years or older, race as white

bolism in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemo- compared with nonwhite, and tobacco use as having

therapy remain unknown. The recommended initial smoked within the prior year or not. Date of diagnosis,

treatment for patients with advanced-stage ovarian date of recurrence, date of the last contact, and vital

cancer is surgical debulking followed by adjuvant plat- status were recorded.

inum and taxane chemotherapy.8 However, patients Medical comorbidities were abstracted from the

with high likelihood of not achieving optimal debulk- medical chart and the Charlson comorbidity score

ing or high surgical morbidity frequently receive neo- was calculated.13 Comorbidities included in the

adjuvant chemotherapy.8,9 Given that these factors Charlson score are diabetes mellitus (categorized as

influencing the choice of neoadjuvant chemotherapy diet-controlled, noninsulin-dependent, or insulin-

have all been associated with increased risk of throm- dependent), hypertension (if previously diagnosed or

boembolism, we hypothesized that patients receiving multiple recorded blood pressure readings greater

neoadjuvant chemotherapy have a high rate of venous than 140/90 mm Hg), obesity (categorized as nonob-

thromboembolism. ese if body mass index [calculated as weight (kg)/

[height (m)]2] less than 30 or obese if body mass index

MATERIALS AND METHODS 30 or greater), history of cardiovascular-related

We performed a descriptive retrospective cohort issues (including congestive heart failure, myocardial

study of women diagnosed with ovarian, fallopian infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, and

tube, or primary peritoneal cancer at the University of peripheral vascular disease), neurovascular diseases

Michigan from January 1, 2009, to May 31, 2014. (including transient ischemic attack and cerebrovascu-

These dates were selected based on a 5-year time- lar accidents with or without neurologic deficit),

frame calculated from the time of institutional review chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kid-

board approval of this study. Individual patient ney disease, and the functional status of the patient

electronic medical record review and data collection (categorized as dependent or independent with regard

were carried out using the University of Michigan to performance of basic activities of daily living). Dis-

Health System Electronic Medical Record Search ease histology was categorized as serous, endome-

Engine patient data search engine.10 Study data were trioid, clear cell, mucinous, or other. The primary

collected and managed using Research Electronic tumor site was recorded as ovarian, fallopian tube,

Data Capture electronic data capture tools hosted at or primary peritoneal. CA 125 levels were recorded

the University of Michigan Medical School.11 at multiple time points, which included: 1) initial diag-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational stud- nosis, 2) after the completion of neoadjuvant chemo-

ies in Epidemiology guidelines were used.12 The insti- therapy, 3) postoperatively, and 4) postadjuvant

tutional review board of the University of Michigan chemotherapy. Imaging data were reviewed and dis-

Health System approved this study (protocol #HUM ease distribution was dichotomized based on the loca-

00095719). tion of the tumor seen on the images as follows: upper

The primary outcome of this study was the number abdomen disease (transverse colon, stomach, liver,

and timing of venous thromboembolic events in the liver parenchyma, intraparenchymal hepatobiliary

neoadjuvant chemotherapy ovarian cancer patient system, diaphragm), mid- and lower abdominal dis-

population. The secondary objective of our study was ease (small bowel and corresponding mesentery), the

to identify patient or treatment factors associated with presence of ascites (categorized as minimal or moder-

increased risk of venous thromboembolism. ate to significant), and the presence or absence of

Women 18 years of age or older with ovarian, omental disease. The stage of the cancer was re-

fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma of corded. Residual disease at the time of interval cytor-

high-grade histology undergoing one or more cycles eduction was defined as microscopic, less than 5 mm,

of chemotherapy before undergoing debulking 5–10 mm, 11–20 mm, or greater than 20 mm.

2 Greco et al Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright Ó by The American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Chemotherapy regimen, route of administration, the that are easily obtained during a routine outpatient

platinum sensitivity of the chemotherapy treatment, evaluation for oncology patients. This score uses

and the timing of any blood transfusions were hemoglobin level, platelet count, and white blood cell

recorded. count at the time of initial diagnosis along with tumor

The number and timing of venous thromboem- histology to assign a patient’s risk of a venous throm-

bolic events were placed in one of four time periods: boembolic event during chemotherapy.14 To examine

venous thromboembolism before neoadjuvant che- whether this model could serve as a predictor in our

motherapy (at the time of diagnosis), venous throm- study cohort, these laboratory values were collected at

boembolism development during neoadjuvant each time point and the Khorana score was calculated

chemotherapy before interval cytoreductive surgery, for each patient.

postoperatively (from the time of cytoreduction until Descriptive analyses of the patient information

reinitiating chemotherapy), or during adjuvant che- were performed. Pearson x2 tests and Fisher exact test

motherapy after surgery. Patients were diagnosed with were used for categorical variables. Multivariable

a venous thromboembolism by either a computed regression modeling and predictive analyses were

tomography scan or Doppler ultrasonography. Pa- not performed as a result of low sample size.

tients with venous thromboembolic disease at the time

of presentation were excluded from further analysis

because they were already on full anticoagulation RESULTS

before initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Six hundred twenty patients with ovarian cancer were

Throughout the study, all patients received sequential identified in the study period. Of these, 161 patients

compression devices and subcutaneous heparin dur- received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and 36 of these

ing their hospitalization postoperatively. The institu- patients were excluded because they did not receive

tional policy of prolonged postoperative prophylaxis their care primarily at the University of Michigan. Of

started at the University of Michigan Hospitals mid- the remaining 125 patients who received neoadjuvant

way through the study period. Therefore, data collec- chemotherapy primarily at the institution of study, 13

tion included whether the patient received prolonged patients (10.4%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 6.1–

prophylactic anticoagulation postoperatively for 28 17.2%) had a venous thromboembolism before or at

days after discharge from the hospital. The Khorana the time of diagnosis. These patients were excluded

score is a risk assessment tool used by medical from further analysis, leaving 112 patients in the final

oncologists for predicting venous thromboembolism cohort who had the potential for a new venous throm-

during outpatient adjuvant chemotherapy.14,15 This boembolism during their cancer care and met all

model is relatively simple and contains parameters inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Study flow diagram. VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Greco. Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Obstet Gynecol 2017.

VOL. 0, NO. 0, MONTH 2017 Greco et al Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy 3

Copyright Ó by The American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

An overview of the timing and incidence of during neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not been pre-

venous thromboembolism at three different time viously reported; 2) despite a low incidence of post-

points is provided in Figure 1. Of the 112 total pa- operative thromboembolism after hysterectomy

tients at risk, 30 (26.8%, 95% CI 19.3–35.9%) experi- (approximately 2%), prevention of venous thrombo-

enced a venous thromboembolism. Based on the embolic disease in the perioperative phase is currently

phase of care, 13 (11.6%, 95% CI 6.8–19.1%) experi- considered a quality-of-care indicator.16,17 In compar-

enced a venous thromboembolism during neoadju- ison, our data show that the rate of thromboembolism

vant chemotherapy (with one death as a result of during neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy is

venous thromboembolism), six (5.4%, 95% CI 2.4– greater than 10%. Based on these data, we recom-

11.5%) developed a postoperative venous thrombo- mend that randomized controlled trials of prophylac-

embolism, and 11 (9.9%, 95% CI 5.5–17%) developed tic anticoagulation during neoadjuvant and adjuvant

a venous thromboembolism during adjuvant chemo- chemotherapy in ovarian cancer should be strongly

therapy. The mean age of the patients who developed considered.

a clot during neoadjuvant chemotherapy was 70.1 Overall, venous thromboembolism complicated

(613.4) years. Eight patients had serous histology; the treatment of one fourth of the patients undergoing

10 were white, 11 were nonsmokers, and nine were neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This is in comparison

nonobese. Moderate to significant ascites was present with previous reports that have demonstrated an

in 7 of the 13 patients. Upper abdominal disease was overall incidence of venous thromboembolism of

present in 10 of the 13 patients as was omental disease approximately 22% in patients with ovarian cancer.1,2

on initial diagnostic imaging. None of the patients in The clinical decision to administer neoadjuvant che-

this cohort had a medical history of venous thrombo- motherapy is generally influenced by the high tumor

embolic disease. burden and patient frailty. Because these two factors

Figure 2 provides a more detailed analysis of the are also the risk factors for developing thromboem-

timing of venous thromboembolism. Patients receiv- bolic disease, it is unsurprising that the incidence of

ing prolonged postoperative prophylaxis for 28 days venous thromboembolism was higher in this cohort.

after discharge had a lower postoperative venous Additionally, although we only had four patients with

thromboembolic event rate compared with those not clear cell histology, two (50%) developed a venous

receiving prolonged prophylaxis. From the 112 at-risk thromboembolism during neoadjuvant chemother-

patients, there were only four patients with clear cell apy. These results are similar to previous studies in

histology, but two of them developed a venous throm- patients with ovarian cancer in whom clear cell histol-

boembolism during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The ogy has been associated with higher risk of venous

rate of thromboembolism in those with nonclear cell thromboembolism.2,18

histology was 9.4% (10/107). On the univariate anal- Previous studies, in other malignancies, examining

ysis, there were no predictors of venous thromboem- the risk of thromboembolism during neoadjuvant

bolism identified for patients undergoing interval chemotherapy have shown similar results as the current

debulking after receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy study. In esophageal cancer, the incidence of venous

(Table 1). thromboembolism during neoadjuvant chemotherapy

is 12.5%.19 Similarly, in transitional cell carcinoma of

DISCUSSION the urinary bladder, 25% of the patients receiving

Our data demonstrate that one in four patients platinum-based chemotherapy developed thromboem-

undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy developed bolic disease (Botten J, Sephton M, Tillett T, Masson S,

a new venous thromboembolism throughout the Thanvi N, Herbert C, et al. Thromboembolic events

timeframe of initial treatment of their cancer. Specif- with cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy for

ically, 1 in 10 patient developed a venous thrombo- transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder [abstract].

embolism during neoadjuvant chemotherapy, an J Clin Oncol 2013;31(suppl 6):277.). In rectal cancer,

additional 10% during adjuvant chemotherapy after patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy concur-

debulking surgery and the remainder during the rently with radiation had an overall 13% incidence of

postoperative phase. These data are important for thromboembolic events.20 These consistently high

several reasons: 1) we observed a venous thrombo- numbers of thromboembolic events in several cancer

embolism rate similar to previously reported in the sites further suggest that patients receiving neoadjuvant

adjuvant chemotherapy phase of care (approximately chemotherapy have a very high risk of developing clots.

10%). However, a similar percentage of patients After the institutional policy of prolonged post-

experiencing thromboembolic events before surgery operative prophylaxis was started at the University of

4 Greco et al Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright Ó by The American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Fig. 2. Detailed demonstration of timing and number of thromboembolic events throughout the course of therapy for

patients with ovarian cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Greco. Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Obstet Gynecol 2017.

Michigan Hospital, we observed a reduction in the in patients with ovarian cancer who undergo debulk-

rate of thromboembolic events in the postoperative ing surgery.6 The institution of this policy midway

setting (6.2% compared with 2.9%). Because our study through our study period does not affect the main

was not powered to detect the efficacy of prolonged finding of our study, which is the high rate of venous

prophylaxis, we are unable to comment on the thromboembolism during neoadjuvant chemother-

efficacy of this intervention from these data. However, apy. Based on these data, as a quality measure, we

recent data from other studies support the use of propose that the institutional-level metrics of the

prolongation of postoperative prophylaxis to 4 weeks cumulative incidence of thromboembolic disease, in

VOL. 0, NO. 0, MONTH 2017 Greco et al Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy 5

Copyright Ó by The American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 1. Patient Demographics During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, With Patients Categorized by Who

Did and Did Not Experience a Venous Thromboembolism Before Interval Debulking Surgery

No Venous Thromboembolism Venous Thromboembolism

Patient Characteristic (n599) (n512) P

Age (y) .761

Younger than 65 40 (91) 4 (9)

65 or older 59 (88) 8 (12)

BMI (kg/m2) 1.000

Nonobese 70 (88.6) 9 (11.4)

Obese 29 (90.6) 3 (9.4)

Race .631

White 88 (89.8) 10 (10.2)

Nonwhite 11 (84.6) 2 (15.4)

Smoker 1.000

No 86 (88.7) 11 (11.3)

Yes 13 (92.9) 1 (7.1)

No. of comorbidities in the Charlson Comorbidity .758

Index

0 22 (95.7) 1 (4.3)

1 29 (87.9) 4 (12.1)

2 25 (86.2) 4 (13.8)

Greater than 3 23 (88.5) 3 (11.5)

Stage of disease .753

III 63 (90.0) 7 (10.0)

IV 36 (87.8) 5 (12.2)

Khorana scoring .964

Less than 3 25 (89.3) 3 (10.7)

Greater than 3 37 (88.1) 5 (11.9)

Unknown 37 (90.2) 4 (9.8)

Blood transfusion during neoadjuvant .731

chemotherapy

No 77 (89.5) 9 (10.47)

Yes 22 (88.0) 3 (12.0)

Moderate to significant ascites on initial imaging 1.000

No 40 (88.9) 5 (11.1)

Yes 59 (89.4) 7 (10.6)

Omental disease on initial imaging 1.000

No 21 (91.3) 2 (8.7)

Yes 78 (88.6) 10 (11.4)

Upper abdomen disease on initial imaging .134

No 49 (94.2) 3 (5.8)

Yes 50 (84.8) 9 (15.2)

Lower abdomen disease on initial imaging .362

No 49 (86.0) 8 (14.0)

Yes 50 (92.6) 4 (7.4)

History of prior venous thromboembolism NA

No 99 (100) 12 (100)

Yes 0 (0) 0 (0)

Clear cell histology .057

No 97 (90.7) 10 (9.3)

Yes 2 (50) 2 (50)

BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable.

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

Table excludes one patient who experienced a fatal pulmonary embolism and did not undergo interval debulking.

patients with ovarian cancer, during all phases of care Our study has several limitations worth consid-

(neoadjuvant, postoperative, and adjuvant chemother- ering. First, this is a retrospective study with a rela-

apy) and just the postoperative phase of care should tively small sample size. Factors such as Khorana

be the focus of future studies. score and extensive upper abdominal disease have

6 Greco et al Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright Ó by The American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

been previously validated in large cohorts. Given following the implementation of extended duration prophylaxis

for patients undergoing surgeries for gynecologic malignancies.

a small sample size, to prevent type II error, we did Gynecol Oncol 2013;128:204–8.

not attempt any predictive analysis of known factors

7. Pant A, Liu D, Schink J, Lurain J. Venous thromboembolism in

in our study. Second, the generalizability of our results advanced ovarian cancer patients undergoing frontline adjuvant

may be limited because our study was performed at chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014;24:997–1002.

a single-institutional tertiary referral center. This 8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical prac-

could have led to an overestimation of overall risk tice guidelines in oncology—ovarian cancer. Available at: https://

www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL5https://www.

of thromboembolism, because patients in referral nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf. Retrieved

centers tend to have more extensive disease. Third, December 16, 2016.

the limited sample size also precluded us from 9. van Meurs HS, Tajik P, Hof MH, Vergote I, Kenter GG, Mol

performing meaningful survival analysis. Finally, we BW, et al. Which patients benefit most from primary surgery or

neoadjuvant chemotherapy in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer?

do not compare the rate of venous thromboembolism

An exploratory analysis of the European Organization for

in patients with ovarian cancer who did receive Research and Treatment of Cancer 55971 randomized trial.

neoadjuvant chemotherapy with those who did not. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:3191–201.

That is currently the subject of our ongoing investi- 10. Hanauer DA, Mei Q, Law J, Khanna R, Zheng K. Supporting

gation. However, we identified such a high incidence information retrieval from electronic health records: a report of

University of Michigan’s nine-year experience in developing

of venous thromboembolism in the neoadjuvant and using the Electronic Medical Record Search Engine

chemotherapy cohort that we felt these data needed (EMERSE). J Biomed Inform 2015;55:290–300.

to be reported given the lack of literature on this 11. Obeid JS, McGraw CA, Minor BL, Conde JG, Pawluk R, Lin

subject. Despite these limitations, there are several M, et al. Procurement of shared data instruments for Research

Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). J Biomed Inform 2013;46:

strengths to our study. The use of a detailed individual 259–65.

patient medical record review allowed for thorough

12. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC,

analyses. The retrospective nature of the study also Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of

allowed us to identify the temporal sequence and Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement:

timing of events with relation to phases of care. guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol

2008;61:344–9.

Our study identifies the neoadjuvant chemotherapy

13. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of

ovarian cancer population as an extremely high-risk a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:

population of developing a venous thromboembolism 1245–51.

during the course of their treatment. Thromboembolic 14. Khorana AA, McCrae KR. Risk stratification strategies for

prophylaxis in these patients may decrease the inci- cancer-associated thrombosis: an update. Thromb Res 2014;

133(suppl 2):S35–8.

dence of venous thromboembolic events and poten-

tially affect overall survival. This becomes especially 15. Khorana AA, Rubens D, Francis CW. Screening high-risk can-

cer patients for VTE: a prospective observational study.

relevant because the proportion of patients with ovarian Thromb Res 2014;134:1205–7.

cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy is rapidly 16. Swenson CW, Berger MB, Kamdar NS, Campbell DA Jr,

increasing in the United States.21 Morgan DM. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism after

hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1139–44.

REFERENCES 17. The Joint Commission—Surgical Care Improvement Project

(SCIP) measure improvement set. Available at: https://man-

1. Abu Saadeh F, Norris L, O’Toole S, Gleeson N. Venous throm- ual.jointcommission.org/releases/archive/TJC2010B/

boembolism in ovarian cancer: incidence, risk factors and MIF0061.html. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

impact on survival. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;

170:214–8. 18. Ye S, Yang J, Cao D, Bai H, Huang H, Wu M, et al. Charac-

teristic and prognostic implication of venous thromboembolism

2. Bakhru A. Effect of ovarian tumor characteristics on venous in ovarian clear cell carcinoma: a 12-year retrospective study.

thromboembolic risk. J Gynecol Oncol 2013;24:52–8. PLoS One 2015;10:e1021818.

3. Metcalf RL, Fry DJ, Swindell R, McGurk A, Clamp AR, Jayson 19. Khanna A, Reece-Smith AM, Cunnell M, Madhusudan S,

GC, et al. Thrombosis in ovarian cancer: a case-control study. Thomas A, Bowrey DJ, et al. Venous thromboembolism in

Br J Cancer 2014;110:1118–24. patients receiving perioperative chemotherapy for esophageal

4. Vedantham S, Piazza G, Sista AK, Goldenberg NA. Guidance cancer. Dis Esophagus 2014;27:242–7.

for the use of thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of venous 20. Mezi S, Musio D, Orsi E, de Felice F, Verdinelli I, Morano F,

thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2016;41:68–80. et al. Incidence of thromboembolic events in patients with

5. Uppal S, Hernandez E, Dutta M, Dandolu V, Rose S, locally advanced rectal cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemo-

Hartenbach E. Prolonged postoperative venous thrombo- radiotherapy. Acta Oncol 2013;52:187–90.

embolism prophylaxis is cost-effective in advanced ovarian 21. Melamed A, Hinchcliff EM, Clemmer JT, Bregar AJ, Uppal S,

cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 2012;127:631–7. Bostock I, et al. Trends in the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy

6. Schmeler KM, Wilson GL, Cain K, Munsell MF, Ramirez PT, for advanced ovarian cancer in the United States. Gynecol On-

Soliman PT, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) rates col 2016;143:236–40.

VOL. 0, NO. 0, MONTH 2017 Greco et al Venous Thromboembolism During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy 7

Copyright Ó by The American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Joint InfectionsDocument10 pagesJoint InfectionsJPNo ratings yet

- Hesi Practice ExamDocument14 pagesHesi Practice ExamYieNo ratings yet

- BJOG 2014 GBS Và PROMDocument10 pagesBJOG 2014 GBS Và PROMHòa HồNo ratings yet

- Interstitial Collagen Synthesis and Processing in Human Amnion: A Property of The Mesenchymal Cells'Document8 pagesInterstitial Collagen Synthesis and Processing in Human Amnion: A Property of The Mesenchymal Cells'Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- An Autocrine/Paracrine Role of Human Decidual Relaxin. II. Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) and Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1)Document9 pagesAn Autocrine/Paracrine Role of Human Decidual Relaxin. II. Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) and Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1)Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics For Preterm Rupture of Membranes (Review) : Kenyon S, Boulvain M, Neilson JPDocument36 pagesAntibiotics For Preterm Rupture of Membranes (Review) : Kenyon S, Boulvain M, Neilson JPHòa HồNo ratings yet

- Biolreprod 0772Document7 pagesBiolreprod 0772Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Katsura 1989Document4 pagesKatsura 1989Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Jcem 2244Document7 pagesJcem 2244Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Cases With Ruptured Membranes That "Reseal": Gainesville, FloridaDocument7 pagesCases With Ruptured Membranes That "Reseal": Gainesville, FloridaHòa HồNo ratings yet

- Alexander 1999Document5 pagesAlexander 1999Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Alger 1988Document8 pagesAlger 1988Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- AmniSure ROM Test Instructions For Use (2019)Document1 pageAmniSure ROM Test Instructions For Use (2019)Hòa HồNo ratings yet

- Hafiz Zaid MahmoodDocument1 pageHafiz Zaid MahmoodraomuhammdshahzadNo ratings yet

- NCP FinalDocument7 pagesNCP FinalRuss RussNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Athletic TrainingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics Athletic Traininggz7vxzyz100% (1)

- Alergi 1Document7 pagesAlergi 1illaNo ratings yet

- Dental Medical CertificateDocument1 pageDental Medical CertificateScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Gordons Eleven Funcional AreasDocument2 pagesGordons Eleven Funcional Areasblue_kitten14No ratings yet

- Financial Difficulties Faced by University StudentsDocument7 pagesFinancial Difficulties Faced by University StudentsMuhammad Mazhar BashirNo ratings yet

- CH62 Management of Differentiated Thyroid CancerDocument52 pagesCH62 Management of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer許懷朔No ratings yet

- Health-7 Q4 LAS Week6-7Document12 pagesHealth-7 Q4 LAS Week6-7Reque RadomesNo ratings yet

- Passi City College City of Passi, Iloilo: School of Criminal JusticeDocument15 pagesPassi City College City of Passi, Iloilo: School of Criminal JusticeKenneth P PablicoNo ratings yet

- Newborn Infant Hearing Screening DMIMSUDocument12 pagesNewborn Infant Hearing Screening DMIMSUSharnie JoNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Basis of Professional Nursing. BOPN317 Dorothea Orem'S Theory of NursingDocument45 pagesTheoretical Basis of Professional Nursing. BOPN317 Dorothea Orem'S Theory of Nursinggideon A. owusuNo ratings yet

- Overview of PHNDocument14 pagesOverview of PHNariel camusNo ratings yet

- Student ProfileDocument4 pagesStudent ProfileJomark OrpillaNo ratings yet

- Human Capital NcertDocument17 pagesHuman Capital NcertYuvika BishnoiNo ratings yet

- Apa Template UvariDocument10 pagesApa Template Uvariapi-507327723No ratings yet

- Volume of DistributionDocument11 pagesVolume of DistributionDr. Mushfique Imtiaz ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Bacterial InfectionDocument122 pagesBacterial InfectionElga MuralidharanNo ratings yet

- Healthy EatingDocument24 pagesHealthy EatingDr. Jayesh Patidar100% (1)

- Renal Management in The Critically Ill PatientDocument16 pagesRenal Management in The Critically Ill PatientAbygail RHNo ratings yet

- Department of Biochemistry, Major S D Singh Medical College & Hospital, Fatehgarh (U.P.), India Tel: 7607879471Document15 pagesDepartment of Biochemistry, Major S D Singh Medical College & Hospital, Fatehgarh (U.P.), India Tel: 7607879471marioNo ratings yet

- Cornwall & Isles of Scilly LMC Newsletter Dec 2013Document8 pagesCornwall & Isles of Scilly LMC Newsletter Dec 2013Cornwall and Isles of Scilly LMCNo ratings yet

- OBE - Syllabus - Psych 109 Abnormal PsychologyDocument15 pagesOBE - Syllabus - Psych 109 Abnormal PsychologySharrah Laine AlivioNo ratings yet

- Blood LettingDocument23 pagesBlood LettingNars Akoh100% (1)

- Current Epidemiology Studie Critical ReviewDocument10 pagesCurrent Epidemiology Studie Critical ReviewMarvin ItolondoNo ratings yet

- Th1 - Th2 Dominance SymptomsList PDFDocument3 pagesTh1 - Th2 Dominance SymptomsList PDFPetra JobovaNo ratings yet

- Proton TherapyDocument21 pagesProton Therapytrieu leNo ratings yet

- DGJKHVDocument7 pagesDGJKHVGILIANNE MARIE JIMENEANo ratings yet