Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Policy On Patient Safety: Latest Revision

Policy On Patient Safety: Latest Revision

Uploaded by

Karin SumOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Policy On Patient Safety: Latest Revision

Policy On Patient Safety: Latest Revision

Uploaded by

Karin SumCopyright:

Available Formats

ORAL HEALTH POLICIES: PATIENT SAFETY

Policy on Patient Safety

Latest Revision How to Cite: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on

2018 patient safety. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago,

Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2020:156-9.

Purpose possible sources of error in the dental office are miscom-

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) munication, interruptions, stress, fatigue, failure to review the

recognizes patient safety as an essential component of quality patient’s medical history (e.g., current medications, allergies),

oral health care for infants, children, adolescents, and those and lack of standardized records, abbreviations, and

with special health care needs. The AAPD encourages dentists processes.1,21,23 Treating the wrong patient or tooth/surgical

to consider thoughtfully the environment in which they deliver site, delay in treatment, disease progression after misdiagnosis,

health care services and to implement practices to improve inaccurate referral, incorrect medication dosage ordered/

patient safety. This policy is not intended to duplicate safety administered, breach in sterilization, and unintentional

recommendations for medical facilities accredited by national swallowing, aspiration, or retention of a foreign object are

commissions such as The Joint Commission or those related examples of patient safety events that occur in dentistry.24-28

to workplace safety such as Occupational Safety and Health Adverse events may be classified in terms of severity of harm

Administration. (e.g., none, mild, moderate, severe, death).29

Standardized processes and workflows help assure clerical

Methods and clinical personnel execute their responsibilities in a safe

This document is a revision of the policy developed by the and effective manner.23 Policy and procedure manuals that

Council on Clinical Affairs, adopted in 2008, and revised describe a facility’s established protocols serve as a valuable

in 2013. This policy is based on a review of current dental training tool for new employees and reinforce a consistent

and medical literature, including search of the PubMed /

MEDLINE database using the terms: patient safety AND

® approach to promote safe and quality patient care.23 Identi-

fying deviations from established protocols and studying

dentistry, fields: all; limits: within the last 10 years, humans, patterns of occurrence can help reduce the likelihood of

English. Eight hundred twenty-two articles met these criteria. adverse events.7

Papers for review were chosen from this list and from the Safety checklists are used by many industries and health-

references within selected articles. care organizations to reduce preventable errors.31,32 Data

supports the use of procedural checklists to minimize the

Background occurrence of adverse events in dentistry (e.g., presedation

All health care systems should be designed to provide a checklist).33-35 In addition, order sets, reminders, and clinical

practice environment that promotes patient safety.1 The guidelines built into an electronic charting system may im-

World Health Organization (WHO) defines patient safety as prove adherence to best practices.28

“the reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with Reducing clinical errors requires a careful examination of

healthcare to an acceptable minimum.”2 The most important adverse events23,28,30 and near-miss events22,36. In a near-miss

challenge in the field of patient safety is prevention of harm, event, an error was committed, but the patient did not ex-

particularly avoidable harm, to patients during treatment and perience clinical harm.22,36 Detection of errors and problems

care.2 Dental practices must be in compliance with federal within a practice or organization may be used as teaching

laws that help protect patients from preventable injuries and points to motivate changes and avoid recurrence.37 A root

potential dangers such as the transmission of disease.3-5 Laws cause analysis can be conducted to determine causal factors

help regulate hazards related to chemical and environmental and corrective actions so these types of events may be avoided

factors (e.g., spills, radiation) and facilities (e.g., fire prevention in the future.31,38,39 Embracing a patient safety culture demands

systems, emergency exits).6 The AAPD’s recommendations and a non-punitive or no-blame environment that encourages all

oral health policies provide additional information regarding personnel to report errors and intervene in matters of patient

the delivery of safe pediatric dental care.7-18 Furthermore, state safety.22,38 Alternatively, a fair and just culture is one that

dental practice acts and hospital credentialing committees are learns and improves by openly identifying and examining its

intended to ensure the safety of patients and the trust of

the public by regulating the competency of and provision of

services by dental health professionals.19-21 ABBREVIATIONS

AAPD: American Academy Pediatric Dentistry. WHO: World

Patient-centered health care systems that focus on pre- Health Organization.

venting errors are critical to assuring patient safety.21,22 Some

156 THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

ORAL HEALTH POLICIES: PATIENT SAFETY

own weaknesses; individuals know that they are accountable • accuracy of patient identification with the use of at

for their actions but will not be blamed for system faults least two patient identifiers, such as name and date of

in their work environment beyond their control.39 Evidence- birth, when providing care, treatment, or services.

based systems have been designed for healthcare professionals • an accurate and complete patient chart that can be

to improve team awareness, clarify roles and responsibilities, interpreted by a knowledgeable third party.13 Standard-

resolve conflicts, improve information sharing, and eliminate izing abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols throughout

barriers to patient safety.40-42 the record is recommended.

The environment in which dental care is delivered impacts • an accurate, comprehensive, and up-to-date medical/

patient safety. In addition to structural issues regulated by dental history including medications and allergy list to

state and local laws, other design features should be planned ensure patient safety during each visit. Ongoing com-

and periodically evaluated for patient safety, especially as they munication with health care providers, both medical

apply to young children. Play structures, games, and toys are and dental, who manage the child’s health helps ensure

possible sources for accidents and infection.43,44 comprehensive, coordinated care of each patient.

The dental patient would benefit from a practitioner who • a pause or time out with dental team members present

follows current literature and participates in professional before invasive procedure(s) to confirm the patient,

continuing education courses to increase awareness and planned procedure(s), and tooth/surgical site(s) are

knowledge of best current practices. Scientific knowledge and correct.

technology continually advance, and patterns of care evolve • appropriate staffing and supervision of patients treated

due, in part, to recommendations by organizations with in the dental office.

recognized professional expertise and stature, including the • adherence to AAPD recommendations on behavior

American Dental Association, The Joint Commission, WHO, guidance, especially as they pertain to use of advanced

Institute for Health Improvement, and Agency for Health- behavior guidance techniques (i.e., protective stabili-

care Research and Quality. Data-driven solutions are possible zation, sedation, general anesthesia).

through documenting, recording, reporting, and analyzing • standardization and consistency of processes within

patient safety events.26,46,47 Continuous quality improvement the practice. A policies and procedures manual, with

efforts including outcome measure analysis to improve patient ongoing review and revision, could help increase em-

safety should be implemented into practices.28,45 Patient safety ployee awareness and decrease the likelihood of un-

incident disclosure is lower in dentistry compared with medicine toward events. Dentists should emphasize procedural

since a dental-specific reporting system does not exist in the protocols that protect the patient’s airway (e.g., rubber

United States.47 Identifiable patient information that is col- dam isolation), guard against unintended retained

lected for analysis is considered protected under the Health foreign objects (e.g., surgical counts; observation of

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).48,49 placement/removal of throat packs, retraction cords,

cotton pellets, and orthodontic separators), and mini-

Policy statement mize opportunity for iatrogenic injury during delivery

To promote patient safety, the AAPD encourages: of care (e.g., protective eyewear).

• patient safety instruction in dental curricula to promote • minimizing exposure to nitrous oxide by maintaining

safe, patient-centered care. the lowest practical levels in the dental environment.

• professional continuing education by all licensed den- This includes routine inspection and maintenance of

tal professionals to maintain familiarity with current nitrous oxide delivery equipment as well as adherence

regulations, technology, and clinical practices. to clinical recommendations for patient selection and

• compliance and recognition of the importance of in- delivery of inhalation agents.

fection control policies, procedures, and practices in • minimizing radiation exposure through adherence to

dental health care settings in order to prevent disease as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) principle,

transmission from patient to care provider, from care equipment inspection and maintenance, and patient

provider to patient, and from patient to patient.2-4 selection criteria.

• routine inspection of physical facility in regards to • all facilities performing sedation for diagnostic and

patient safety. This includes development and periodic therapeutic procedures to maintain records that track

review of office emergency and fire safety protocols adverse events. Such events then can be examined

and routine inspection and maintenance of clinical for assessment of risk reduction and improvement in

equipment. patient safety.

• recognition that informed consent by the parent is • dentists who utilize in-office anesthesia providers take

essential in the delivery of health care and effective all necessary measures to minimize risk to patients. Prior

relationship/communication practices can help avoid to delivery of sedation/general anesthesia, appropriate

problems and adverse events. The parent should under- documentation shall address rationale for sedation/

stand and be actively engaged in the planned treatment. general anesthesia, informed consent, instructions to

THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 157

ORAL HEALTH POLICIES: PATIENT SAFETY

parent, dietary precautions, preoperative health evalua- 8. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Use of nitrous

tion, and any prescriptions along with the instructions oxide for pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent 2018;

given for their use. Rescue equipment should have 40(6):281-6.

regular safety and function testing and medications 9. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Prescribing

should not be expired. The dentist and anesthesia dental radiographs for infants, children, adolescents, and

providers must communicate during treatment to share individuals with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent

concerns about the airway or other details of patient 2017;39(6):205-7.

safety. 10. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Behavior

• ongoing quality improvement strategies and routine guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent

assessment of risk, adverse events, and near misses. A 2017;39(6):246-59.

plan for improvement in patient safety and satisfaction 11. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Protective

is imperative for such strategies.5,6 stabilization for pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent

• comprehensive review and documentation of indica- 2017;39(6):260-5.

tion for medication order/administration. This includes 12. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Informed

a review of current medications, allergies, drug inter- consent. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(6):397-9.

actions, and correct calculation of dosage. 13. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Monitoring

• promoting a culture where staff members are empowered and management of pediatric patients before, during, and

and encouraged to speak up or intervene in matters of after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures:

patient safety. Update 2016. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(6):278-307.

14. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Use of anes-

References thesia providers in the administration of office-based

1. Bailey E, Tickle M, Campbell S. Patient safety in primary deep sedation/general anesthesia to the pediatric dental

care dentistry: Where are we now? Br Dent J 2014;217 patient. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(6):317-20.

(7):333-44. 15. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Use of local

2. World Health Organization. Patient safety: Making anesthesia in pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent 2017;

health care safer. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health 39(6):266-72.

Organization; 2017. License CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 16. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on

Available at: “http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/ acute pediatric dental pain management. Pediatr Dent

10665/255507/;jsessionid=A2E0196DF284A670341F5FF 2017;39(6):99-101.

B6DA4EF41?sequence=1”. Accessed August 21, 2018. 17. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Use of anti-

org/71qPk9eTT”)

®

(Archived by WebCite at: “http://www.webcitation. biotic therapy for pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent

2017;39(6):371-3.

3. Boyce JM, Pittet D, Healthcare Infection Control Prac- 18. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatric

tices Advisory Committee, HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA restorative dentistry. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(6):312-24.

Hand Hygiene Task Force. Guideline for hand hygiene 19. American Association of Dental Boards. Composite –

in health-care settings. Available at: “http://www.cdc. 29th edition (2018). Chicago, Ill.: American Association

gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5116a1.htm”. Accessed of Dental Boards; 2018:1-108.

www.webcitation.org/6vmkKjYxM”)

®

December 17, 2017. (Archived by WebCite at: “http:// 20. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on

hospital staff membership. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(6):

4. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand 106-7.

hygiene in health care. Available at: “http://apps.who. 21. The Joint Commission. 2017 National Patient Safety

int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44102/9789241597906 Goals Ambulatory Care Program. Available at: “https://

_eng.pdf.?sequence=1”. Accessed August 21, 2018. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/NPSG_Chapter_

71qQJvBLF”)

®

(Archived by WebCite at: “http://www.webcitation.org/ AHC_Jan2018.pdf ”. Accessed June 25, 2018.

22. Ramoni RB, Walji MF, White J, et al. From good to

5. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on better: Towards a patient safety initiative in dentistry. J

infection control. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(6):144. Am Dent Assoc 2012;143(9):956-60.

6. U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and 23. Jadhay A, Kumar S, Acharya S, Payoshnee B, Ganta S.

Health Administration. OSHA Law and Regulations. Patient safety practices in dentistry: A review. Int J Sci

Available at: “https://www.osha.gov/law-regs.html”. Study 2016;3(10):163-5.

Accessed December 18, 2017. (Archived by WebCite

at: “http://www.webcitation.org/6vpmTao5J”)

® 24. Black I, Bowie P. Patient safety in dentistry: Develop-

ment of a candidate ‘never event’ list for primary care.

7. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Br Dent J 2017;222(10):782-8.

minimizing occupational health hazards associated with

nitrous oxide. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(6):104-5.

158 THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

ORAL HEALTH POLICIES: PATIENT SAFETY

25. Cullingham P, Saksena A, Pemberton MN. Patient 37. Tucker AL, Edmondson AC. Why hospitals don’t learn

safety: Reducing the risk of wrong tooth extraction. Br from failures: Organizational and psychological dynamics

Dent J 2017;222(10):759-63. that inhibit systemic change. Calif Manag Rev 2003;45

26. Obadan EM, Ramoni RB, Kalenderian E. Lessons learned (2):55-72.

from dental patient safety case reports. J Am Dent Assoc 38. Ramoni R, Walii MF, Tavares A, et al. Open wide:

2015;146(5):318-26. Looking into the safety culture of dental school clinics.

27. Ensaldo-Carrasco E, Suarez-Ortegon MF, Carson-Stevens J Dent Educ 2014;78(5):745-56.

A, Cresswell K, Bedi R, Sheikh A. Patient safety inci- 39. Frankel AS, Leonard MW, Denham CR. Fair and just

dents and adverse events in ambulatory dental care: A culture, team behavior, and leadership engagement: The

systematic scoping review. J Patient Saf 2016;0(0):Epub tools to achieve high reliability. Health Serv Res 2006;

ahead of print. Available at: “https://pdfs.semantic 41(4 Pt 2):1690-709.

scholar.org/b11d/1d99a0edc003f6d7d3327c3b14f543

151725.pdf ”. Accessed August 29, 2018. (Archived by

40. Sheppard F, Williams M, Klein V. TeamSTEPPS and

patient safety in healthcare. J Healthc Risk Manag 2013;

®

®

WebCite at: “http://www.webcitation.org/72KqzpPm4”)

28. American Academy of Pediatrics. Principles of patient

32(3):5-10.

41. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency

safety in pediatrics: Reducing harm due to medical care.

Pediatrics 2011;127(6):1199-210. Erratum in Pediatrics

for Healthcare Research and Quality. TeamSTEPPS

Dental Module. Available at: “https://www.ahrq.gov/

®

2011;128(6):1212. teamstepps/dental/index.html”. Accessed August 29,

29. Kalenderian E, Obadan-Udoh E, Maramaldi P, et al.

Classifying adverse events in the dental office. J Patient

®

2018. (Archived by WebCite at: “http://www.web

citation.org/71qQoi3QN”)

Saf 2017;0(0):Epub ahead of print. Available at: “https: 42. Leonard M, Frankel A, Federico F, Frush K, Haradan C.

//dentistry.ucsf.edu/sites/default/files/event/attachments/ The Essential Guide for Patient Safety Officers, 2nd

E.Kalenderian-EBD%20JC%205-15-18%20Article.pdf ”. ed. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.: The Joint Commission, Inc.;

Accessed August 29, 2018. (Archived by WebCite at:

“http://www.webcitation.org/72KqqUzml”)

® 2013:1-160.

43. Rathmore MH, Jackson MA. Infection prevention and

30. Hurst D. Little research on effective tools to improve control in pediatric ambulatory services. Pediatrics 2017;

patient safety in the dental setting. Evid Based Dent 140(5):1-23.

2016;17(2):38-9. 44. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury,

31. Harden SW, Roberson JB. 8.5 tips for dental safety Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement – Pre-

checklists. Todays FDA 2013;25(6):40-3, 45. vention of choking among children. Pediatrics 2010;

32. World Health Organization. Surgical Safety Checklist 125(3):601-7.

2009. Available at: “http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/ 45. Kiersma ME, Plake KS, Darbishire PL. Patient safety

10665/44186/2/9789241598590_eng_Checklist.pdf ”. institution in U.S. health professions education. Am J

Accessed August 29, 2018. (Archived by WebCite at:

“http://www.webcitation.org/72Kr6z52T”)

® Pharm Educ 2011;75(8):162.

46. Spera AL, Saxon MA, Yepes JF. Office-based anesthesia:

33. Bailey E, Tickle M, Campbell M, O’Malley L. System- Safety and outcomes in pediatric dental patients. Anesth

atic review of patient safety interventions in dentistry. Prog 2017;64(3):144-52.

BMC Oral Health 2015;15(152):1-11. 47. Thusu S, Panasar S, Bedi R. Patient safety in dentistry –

34. Saksena A, Pemberton MJ, Shaw A, Dickson S, Ashley State of play as revealed by a national database of errors.

MP. Preventing wrong tooth extraction: Experience in Br Dent J 2012;213(E3):1-8.

development and implementation of an outpatient safety 48. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Record-

checklist. Br Dent J 2014;217(7):357-62. Erratum in Br keeping. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(6):401-8.

Dent J 2014;217(10):585. 49. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office

35. Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Stearns SC. Agreement between for Civil Rights. HIPAA Administration Simplification

structured checklists and Medicaid claims for preventive Regulation Text. 2013. Available at: “https://www.hhs.

dental visits in primary care medical offices. Health gov/sites/default/files/hipaa-simplification-201303.pdf”.

Informatics J 2010;16(2):115-28.

36. Frankel A, Haraden C, Federico F, Lenoci-Edwards J. A

Accessed June 25, 2018. (Archived by WebCite at:

“http://www.webcitation.org/70RmKz8cI”)

®

framework for safe, reliable, and effective care. White

Paper. Cambridge, Mass.: Institute for Healthcare

Improvement and Safe & Reliable Healthcare; 2017.

Available at: “http://www.ihi.org”. Accessed June 25,

®

2018. (Archived by WebCite at: “http://www.web

citation.org/71Ov0TcbO”)

THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 159

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- Tarot of The AbyssDocument119 pagesTarot of The Abyssb2linda100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Statics and Mechnics of StructuresDocument511 pagesStatics and Mechnics of StructuresPrabu RengarajanNo ratings yet

- Wohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 2Document32 pagesWohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 2Karin SumNo ratings yet

- Wohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 1Document20 pagesWohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 1Karin SumNo ratings yet

- Wohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 1Document20 pagesWohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 1Karin Sum100% (1)

- Wohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 2Document32 pagesWohlfahrt Selected Studies Book 2Karin SumNo ratings yet

- Nyvad CriteriaDocument9 pagesNyvad CriteriaKarin SumNo ratings yet

- Solar System EssayDocument1 pageSolar System Essayapi-327692674No ratings yet

- HRM PPT EiDocument7 pagesHRM PPT EiKaruna KsNo ratings yet

- CceDocument19 pagesCcebabagoudNo ratings yet

- 【拉图尔】临界区域:关键区域Critical ZonesDocument472 pages【拉图尔】临界区域:关键区域Critical Zoneszhang yanNo ratings yet

- Model Aliansi Untuk Peningkatan Kualitas Pembelajaran Dan Penyerapan Kerja AlumniDocument16 pagesModel Aliansi Untuk Peningkatan Kualitas Pembelajaran Dan Penyerapan Kerja Alumniagung djibranNo ratings yet

- K Beauty Decoded Achieving Glass Skin For Women - 65330591Document83 pagesK Beauty Decoded Achieving Glass Skin For Women - 65330591Arpit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Double Effect Evaporator OperationDocument6 pagesDouble Effect Evaporator Operationpaulhill222No ratings yet

- Michelangelo Research Paper OutlineDocument4 pagesMichelangelo Research Paper Outlinecampsxek100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Martial Arts RonelDocument2 pagesFundamentals of Martial Arts RonelRodne Badua RufinoNo ratings yet

- Verbal Communication SkillsDocument61 pagesVerbal Communication SkillsSOUMYA MUKHERJEE-DM 20DM215No ratings yet

- Topic No. 21 Child-Friendly EnvironmentDocument3 pagesTopic No. 21 Child-Friendly Environmentjezza linglingNo ratings yet

- Clock Arithmetic Aptitude Question With AnswersDocument4 pagesClock Arithmetic Aptitude Question With AnswersOpt TutorNo ratings yet

- EP001 LifeCoachSchoolTranscriptDocument13 pagesEP001 LifeCoachSchoolTranscriptVan GuedesNo ratings yet

- Philsec Investment v. CA (GR. No. 103493. June 19, 1997)Document15 pagesPhilsec Investment v. CA (GR. No. 103493. June 19, 1997)Mayjolica AgunodNo ratings yet

- IAD Compare Contrast Frame Method CC 2018Document2 pagesIAD Compare Contrast Frame Method CC 2018Sri NarendiranNo ratings yet

- Gpon - Vlan - Gem PortDocument5 pagesGpon - Vlan - Gem PortLe VuNo ratings yet

- Lab 5 - Archimedes PrincipleDocument13 pagesLab 5 - Archimedes PrincipleLance ShahNo ratings yet

- Ma History Dissertation StructureDocument7 pagesMa History Dissertation StructureCheapCustomPapersSingapore100% (1)

- Chapter 39 - Lower Digestive Tract DisordersDocument5 pagesChapter 39 - Lower Digestive Tract DisordersStacey100% (1)

- Max17201gevkit Max17211xevkitDocument24 pagesMax17201gevkit Max17211xevkitmar_barudjNo ratings yet

- Article 1162Document5 pagesArticle 1162hannabee00No ratings yet

- Introduction To Coastal Engineering D-AngremondDocument278 pagesIntroduction To Coastal Engineering D-Angremondthauwui86100% (2)

- Is Karma A Infinite LoopDocument13 pagesIs Karma A Infinite LoopAman SkNo ratings yet

- Pascal Contest: Canadian Mathematics CompetitionDocument5 pagesPascal Contest: Canadian Mathematics CompetitionJoshuandy JusufNo ratings yet

- Median and ModeDocument24 pagesMedian and Modemayra kshyapNo ratings yet

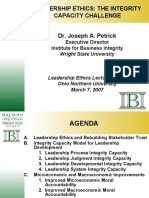

- Leadership Ethics and The Integrity Capacity ChallengeDocument38 pagesLeadership Ethics and The Integrity Capacity ChallengeJP De LeonNo ratings yet

- Cooling Water Treatment PDFDocument3 pagesCooling Water Treatment PDFdineshkbunker08No ratings yet

- Clarification of Ejection and Sweep in Rectangular Channel Turbulent FlowDocument21 pagesClarification of Ejection and Sweep in Rectangular Channel Turbulent FlowmedianuklirNo ratings yet