Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Smoking and Mental Illness - Breaking The Link: Perspective

Smoking and Mental Illness - Breaking The Link: Perspective

Uploaded by

kinasihasyaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Alternatives To Addict BehaviorDocument5 pagesAlternatives To Addict BehaviorYungstonNo ratings yet

- Mark Klimek Lecture 4 Canes N CrutchesDocument4 pagesMark Klimek Lecture 4 Canes N CrutchesJohn Desir100% (1)

- Durkhiem On LawDocument2 pagesDurkhiem On LawJyotsnaNo ratings yet

- Social Cognition (Making Sense of People)Document8 pagesSocial Cognition (Making Sense of People)Julia SNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheet Week 5 ORAL COMM PDFDocument2 pagesLearning Activity Sheet Week 5 ORAL COMM PDFMark Allen LabasanNo ratings yet

- Solty 2009Document10 pagesSolty 2009Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Psychological Features of Smokers: Askin Gu Lsen MD and Bu Lent Uygur MDDocument6 pagesPsychological Features of Smokers: Askin Gu Lsen MD and Bu Lent Uygur MDMarianaNo ratings yet

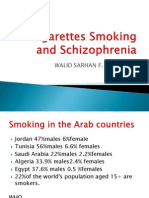

- Walid Sarhan F. R. C. PsychDocument46 pagesWalid Sarhan F. R. C. PsychFree Escort ServiceNo ratings yet

- Nejmcp 2032393Document10 pagesNejmcp 2032393JEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Psychological Effect F NicotineDocument6 pagesPsychological Effect F NicotinehelfiNo ratings yet

- Nihms 122181Document23 pagesNihms 122181Carlos BareaNo ratings yet

- Dong Liu WuDocument29 pagesDong Liu WuJohn Vincent Consul CameroNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Tobacco and Cigarette Consumption and Their Relationship Between Psychological Behaviour - A Narrative ReviewDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Tobacco and Cigarette Consumption and Their Relationship Between Psychological Behaviour - A Narrative ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 2022 Tobacco AdictionDocument10 pages2022 Tobacco AdictionJuan jose Cacua DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento en Patología DualDocument7 pagesTratamiento en Patología DualBalmaNo ratings yet

- Marijuana Facts NIDADocument6 pagesMarijuana Facts NIDALexi PrunellaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Prolonged Cannabis Withdrawal in Young Adults With Lifetime Psychiatric IllnessDocument15 pagesHHS Public Access: Prolonged Cannabis Withdrawal in Young Adults With Lifetime Psychiatric Illnessyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- Factors Relating To Failure To Quit Smoking A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument7 pagesFactors Relating To Failure To Quit Smoking A Prospective Cohort StudySilas SilvaNo ratings yet

- Summary of ResearchDocument7 pagesSummary of Researchapi-549189480No ratings yet

- Review: Managing Smoking CessationDocument9 pagesReview: Managing Smoking CessationARAFAT MIAHNo ratings yet

- Wilson-Comorbid Mood, Psychosis, and Marijuana Abuse Disorders (2008)Document14 pagesWilson-Comorbid Mood, Psychosis, and Marijuana Abuse Disorders (2008)Pau RochaNo ratings yet

- Tobacco Dependence Treatment For Special Populations: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument8 pagesTobacco Dependence Treatment For Special Populations: Challenges and OpportunitiesJonatan VelezNo ratings yet

- Mariguana InformationDocument8 pagesMariguana InformationAlberto Aguirre SanchesNo ratings yet

- Efectividad de Bupropion y Otras IntervencionesDocument12 pagesEfectividad de Bupropion y Otras IntervencionesFranco LaviaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Ajp 2019 05 002Document7 pages10 1016@j Ajp 2019 05 002Dwi Rachma MeilinaNo ratings yet

- A Preliminary Trial: Double-Blind Comparison of Nefazodone, Bupropion-SR, and Placebo in The Treatment of Cannabis DependenceDocument12 pagesA Preliminary Trial: Double-Blind Comparison of Nefazodone, Bupropion-SR, and Placebo in The Treatment of Cannabis DependenceJai KunvarNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Bing 3Document11 pagesJurnal Bing 3Abangnya Dea AmandaNo ratings yet

- LoweD J E Etal 2018 Eur Arch Psychiat Clin NeurosciinpressDocument15 pagesLoweD J E Etal 2018 Eur Arch Psychiat Clin Neurosciinpressjjj-marta8474No ratings yet

- Smoking, Electronic MetDocument7 pagesSmoking, Electronic MetThomas PendersNo ratings yet

- Accepted ManuscriptDocument40 pagesAccepted ManuscriptsueffximenaNo ratings yet

- A Game For SmokersDocument4 pagesA Game For SmokerstifaniNo ratings yet

- Research Paper-2Document9 pagesResearch Paper-2api-741551545No ratings yet

- Smoking in Psychiatric Hospitals: What Is The Role of Nursing Staff?Document5 pagesSmoking in Psychiatric Hospitals: What Is The Role of Nursing Staff?International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- CASE REPORT Family Therapy in Cigarette Addiction: Case ReportDocument5 pagesCASE REPORT Family Therapy in Cigarette Addiction: Case Reportrbatjun576No ratings yet

- Nicotine Dependence: Current Treatments and Future DirectionsDocument17 pagesNicotine Dependence: Current Treatments and Future DirectionsI Komang Ana MahardikaNo ratings yet

- Johnson Et Al. (2017) Smoking Quit With PsilocybeDocument11 pagesJohnson Et Al. (2017) Smoking Quit With PsilocybeJuanmaNo ratings yet

- AJGP 10 2019 Focus Manger Lifestyle Interventions Mental Health WEBDocument4 pagesAJGP 10 2019 Focus Manger Lifestyle Interventions Mental Health WEBisitugasnandasekarbuanaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Smoking Cessation Success in AdultsDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Smoking Cessation Success in AdultsSISNo ratings yet

- ASH Factsheet - Mental Health - v3 2019 27 August 1Document11 pagesASH Factsheet - Mental Health - v3 2019 27 August 1trishahannah.naguimbingNo ratings yet

- Dapus Referat No.4Document7 pagesDapus Referat No.4Muhammad AkrimNo ratings yet

- Role of The Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurse Practitioner PaperDocument10 pagesRole of The Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurse Practitioner PaperemmelineboneNo ratings yet

- Smoking Behaviour and Mental Health Disorders-Mutual Influences and Implications For TherapyDocument22 pagesSmoking Behaviour and Mental Health Disorders-Mutual Influences and Implications For TherapyRizza Faye BalayangNo ratings yet

- N Acetylcysteine For Therapy Resistant Tobacco Use Disorder A Pilot StudyDocument9 pagesN Acetylcysteine For Therapy Resistant Tobacco Use Disorder A Pilot Studytami syhabNo ratings yet

- Intervention For Smoking ReductionDocument15 pagesIntervention For Smoking Reductionben mwanziaNo ratings yet

- Feeling GreatDocument243 pagesFeeling GreatSunny LamNo ratings yet

- Add 12140Document9 pagesAdd 12140imadhassanNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Clinical TrialsDocument8 pagesContemporary Clinical TrialsAzisahhNo ratings yet

- Jama Stop SmokeDocument8 pagesJama Stop Smokeandrew herringNo ratings yet

- Prosser. Biological V Psychosocial Treatments - A Myth About Pharmacotherapy V PsychotherapyDocument3 pagesProsser. Biological V Psychosocial Treatments - A Myth About Pharmacotherapy V PsychotherapyNatalia López MedinaNo ratings yet

- Improving Patient Education About Tobacco Withdrawal and Nicotine Gum Use by Registered Nurses in Inpatient Psychiatry: A Feasibility StudyDocument10 pagesImproving Patient Education About Tobacco Withdrawal and Nicotine Gum Use by Registered Nurses in Inpatient Psychiatry: A Feasibility StudyIzzat HafizNo ratings yet

- National Trends in Cessation Counseling, Prescription Medication UseDocument13 pagesNational Trends in Cessation Counseling, Prescription Medication UseConstantin PopescuNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@jgsDocument10 pages10 1111@jgsFamilia En AcNo ratings yet

- Ats Guidelines Smoking CessationDocument27 pagesAts Guidelines Smoking CessationAna Milena CallejasNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Smoking Cessation and The Cardiovascular PatientDocument11 pagesHHS Public Access: Smoking Cessation and The Cardiovascular PatientNatalia CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Susbatnce Use Disorder PPT FinalDocument19 pagesSusbatnce Use Disorder PPT FinalSalami ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Kahan Et Al, 2019 CommentaryDocument5 pagesKahan Et Al, 2019 CommentaryswagciciliNo ratings yet

- Cannabis: PharmacologyDocument6 pagesCannabis: PharmacologyAntonio Tejero PocielloNo ratings yet

- Pratique D'une Intervention Motivationnelle Pour Les Consommateurs de Cannabis Souffrant de PsychoseDocument8 pagesPratique D'une Intervention Motivationnelle Pour Les Consommateurs de Cannabis Souffrant de Psychosecelia.longuetNo ratings yet

- Smoking Cessation Nursing InterventionsDocument12 pagesSmoking Cessation Nursing Interventionsapi-741272284No ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Tobacco Use in First-Episode PsychosisDocument11 pagesA Systematic Review of Tobacco Use in First-Episode PsychosisVivi DeviyanaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health - CannabisDocument14 pagesMental Health - CannabisEmmanuel Raphael SanturayNo ratings yet

- Add 117 2075Document21 pagesAdd 117 2075hilda ZanibaNo ratings yet

- SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER Group 6Document36 pagesSUBSTANCE USE DISORDER Group 6Salami ibrahimNo ratings yet

- 10' Smoking CessationDocument1 page10' Smoking CessationfabiandionisioNo ratings yet

- Major Components of Curriculum DesignDocument8 pagesMajor Components of Curriculum DesignelynNo ratings yet

- COGSASH Response Ganya Bishnoi 21012009Document3 pagesCOGSASH Response Ganya Bishnoi 21012009Ganya BishnoiNo ratings yet

- Good NotesDocument5 pagesGood NotesMikee BoomNo ratings yet

- Organizational Learning: Sreenath BDocument23 pagesOrganizational Learning: Sreenath BSreenath100% (1)

- Psychometric TestDocument4 pagesPsychometric TestSakshi Mittal100% (1)

- Hilton Hotel ColomboDocument23 pagesHilton Hotel Colombokokila amarasingheNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Portfolio AssessmentDocument11 pagesChapter 10 Portfolio Assessmentapi-469710033No ratings yet

- Session 6-9 CFU - NUR 152 RLEDocument3 pagesSession 6-9 CFU - NUR 152 RLEDarwin QuirimitNo ratings yet

- Scied 204 Teaching Science Junabel7 Wilnie OfficeDocument32 pagesScied 204 Teaching Science Junabel7 Wilnie OfficeLyka Jane Genobatin BinayNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8 Perdev Understanding The SelfDocument13 pagesLesson 8 Perdev Understanding The SelfJasmin BasadreNo ratings yet

- HypnosisDocument18 pagesHypnosisapi-26413035No ratings yet

- Asm 1 Manh Cuong (BTEC HN)Document18 pagesAsm 1 Manh Cuong (BTEC HN)RyderNo ratings yet

- Neha HR Thesis 3Document21 pagesNeha HR Thesis 3Bidisha BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document14 pagesChapter 8Nhật DuyNo ratings yet

- LLU0021 EnglezaDocument52 pagesLLU0021 EnglezaNohai JojoNo ratings yet

- Unit IDocument2 pagesUnit ISNo ratings yet

- Buddying Programme: Supporting Employee InductionDocument5 pagesBuddying Programme: Supporting Employee InductionAnggitfenNo ratings yet

- Employee Development - PPT 9Document39 pagesEmployee Development - PPT 9sachinthestar2007No ratings yet

- GAS - General Adaptation SyndromeDocument2 pagesGAS - General Adaptation SyndromeabassalishahNo ratings yet

- Emotional ProcessingDocument4 pagesEmotional ProcessingLucy FoskettNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesLesson PlanMr. Cliff BhattNo ratings yet

- Course-Syllabus-Social ArtsDocument4 pagesCourse-Syllabus-Social Artsannelyn velascoNo ratings yet

- (1983) Sense of Humor As A Moderator of The RelationDocument13 pages(1983) Sense of Humor As A Moderator of The Relationarip sumantriNo ratings yet

- Ms Liji Raichel Kurian, Caritas College of NursingDocument52 pagesMs Liji Raichel Kurian, Caritas College of NursingJOSLINNo ratings yet

- Havinghurst Developmental TaskDocument1 pageHavinghurst Developmental TaskHazel DialinoNo ratings yet

Smoking and Mental Illness - Breaking The Link: Perspective

Smoking and Mental Illness - Breaking The Link: Perspective

Uploaded by

kinasihasyaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Smoking and Mental Illness - Breaking The Link: Perspective

Smoking and Mental Illness - Breaking The Link: Perspective

Uploaded by

kinasihasyaCopyright:

Available Formats

PERSPE C T I V E Smoking and Mental Illness — Breaking the Link

Smoking and Mental Illness — Breaking the Link

Judith J. Prochaska, Ph.D., M.P.H.

“M y doctor told me I’m too

stressed out to quit smok-

ing,” remarked a woman hospi-

little-to-no disturbance in pa-

tients’ behavior and time savings

for staff members.

tial social and financial costs to

patients, their families, and soci-

ety. As greater restrictions on ex-

talized with severe depression. Yet even in smoke-free psychi- posure to secondhand smoke are

“Well, 43 years later, I’m still atric settings, treatment of tobac- implemented in many public areas,

stressed and I’m still smoking.” co use remains relatively rare. In tobacco use is further isolating

This woman’s dilemma is all too my group’s recent studies, among an already-marginalized group.

familiar to health care providers 337 smokers recruited from inpa- Five prevailing myths have con-

and patients seeking the ideal time tient psychiatry units, 82% re- tributed to continuing tobacco

to treat tobacco dependence in the ported having attempted to quit, use among people with mental

face of chronic mental illness. and 42% reported having done illness. The first is that tobacco

Since smoking and mental ill- so within the previous year; only is necessary self-medication for

ness commonly occur together, 4% reported receiving assistance the mentally ill. The tobacco in-

many clinicians see them as in- with quitting smoking from a dustry has fostered this belief by

extricably linked and believe that mental health care or general funding research and presenta-

smoking in the mentally ill is health care provider. Moreover, tions on the self-medication hy-

therefore particularly challenging there are still outpatient mental pothesis, supporting opposition

to treat. Little examined are the health programs that provide ciga- to the JCAHO smoking ban, pub-

systemic and treatment factors rettes as an incentive for patients lishing articles in the lay press,

that have contributed to dispari- to comply with treatment. and marketing cigarettes to peo-

ties in tobacco use and tobacco- The devastating consequences ple with mental illness.2

related morbidity and mortality of tobacco use among smokers Nicotine is a powerful rein-

among people with mental illness. with mental illness are evident. forcing drug that transiently en-

Twenty years ago, the Joint Smokers with serious mental ill- hances concentration and atten-

Commission on the Accredita- ness are at increased risk for can- tion, regardless of the smoker’s

tion of Healthcare Organizations cer, lung disease, and cardiovascu- mental health status. But it has

(JCAHO, now the Joint Commis- lar disease, and they die 25 years proved ineffective as an adjunc-

sion) proposed a national ban on sooner, on average, than Ameri- tive treatment for mental disor-

tobacco use in hospitals, noting cans overall. Tobacco use also ders (e.g., depression, schizophre-

the contradiction between hospi- complicates psychiatric treatment. nia, and attention-deficit disorder),

tals’ health care mission and their Components in tobacco smoke possibly because of the rapid de-

exposing of patients, staff mem- accelerate the metabolism of some crease in drug response with re-

bers, and visitors to the harms of antidepressant and antipsychotic peated exposure. The reality is

secondhand smoke. Patient-advo- medications, resulting in lowered that tobacco is another problem,

cacy groups for the mentally ill blood levels and probably reduced not a solution.

strongly opposed the ban, arguing therapeutic benefit. Studies have Myth number two is that peo-

that tobacco’s therapeutic, calm- revealed higher hospitalization ple with mental illness are not

ing effect was valuable and warn- rates, higher medication doses, interested in quitting smoking.

ing that psychiatric patients who and more severe psychiatric symp- Research argues otherwise: stud-

were denied their cigarettes would toms among patients with schizo- ies involving patients recruited

revolt. JCAHO conceded and ex- phrenia who smoke than among from outpatient and inpatient psy-

empted psychiatric and drug- those who do not. Though the chiatric settings suggest that they

treatment units from the smok- mechanism is unclear, tobacco use are about as likely as the general

ing ban. Psychiatric hospitals that also is one of the strongest pre- population to want to quit smok-

voluntarily adopted such bans, dictors of future suicidal behav- ing.1 In the United States, 20 to

however, have documented both ior.1 Smoking results in substan- 25% of smokers report that they

196 n engl j med 365;3 nejm.org july 21, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 27, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PERSPECTIVE Smoking and Mental Illness — Breaking the Link

Recommended Treatments for Tobacco Dependence and the Evidence Base for Use in Smokers with Mental Illness.*

Treatment Strategy Findings in Smokers with Mental Illness

Clinician advice to quit and referral In one trial in clinically depressed smokers, yielded abstinence rate of 19% at 18 months

of follow-up.1

Individual cessation counseling At 18 months of follow-up, individual counseling with access to cessation pharmaco‑

therapy achieved abstinence in 18% of smokers with PTSD3 and 25% of those with

depression.1

Group cessation counseling Group counseling plus nicotine replacement achieved 19 to 21% abstinence at 12

months of follow-up in outpatients with serious mental illness; tailoring content for

smokers with schizophrenia was equally effective.

Quit-lines The nearly 25% of callers to the California quit-line who had major depression were sig‑

nificantly less likely than nondepressed callers to have quit smoking at 2 months of

follow-up.

Nicotine replacement: patch, gum, One trial found nicotine gum particularly helpful among depressed (as compared with

lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray nondepressed) smokers (36% abstinence at 3 months). In acute care settings, nico‑

tine replacement reduced agitation in smokers with schizophrenia and was associat‑

ed with lower rates of leaving inpatient psychiatric settings against medical advice.

Extended use of a nicotine patch reduced relapse risk among smokers with schizo‑

phrenia. A case series documented that nicotine nasal spray was used appropriately

by smokers with schizophrenia and supported cessation.

Bupropion An effective cessation aid in smokers with or without current or past depression. A meta-

analysis of 7 trials in 260 smokers with schizophrenia showed significant effects at

6 months of follow-up.4 According to a case study, two smokers with bipolar disorder

quit smoking with no adverse effects on mood.

Varenicline Three case series involving medically stable outpatients with schizophrenia reported

significant smoking reduction, 8-to-75% quit rates, improvements on some cogni‑

tive tests, and no serious adverse effects; individual case reports reveal mixed effects

in smokers with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Three randomized, controlled trials

in smokers with schizophrenia or depression are in process.

Nortriptyline Demonstrated efficacy in the general population and among smokers with a history of

depression; no data on smokers with current mental illness.

Clonidine Demonstrated efficacy in the general population; no data on smokers with mental

illness.

* Information on recommended treatments for tobacco dependence is from Fiore et al.5 Bupropion and varenicline include an

FDA-mandated black-box warning highlighting the risk of serious neuropsychiatric symptoms, including changes in behavior,

hostility, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal thoughts and behavior, and attempted suicide. Nortriptyline and clonidine are

second-line cessation pharmacotherapies that have been identified as efficacious in the general population but are not FDA-

approved. PTSD denotes post-traumatic stress disorder.

intend to quit smoking in the dependence is challenging, sev- for help doing so) and similar to

next 30 days, and another 40% eral randomized treatment trials cessation rates in the general pop-

say they intend to do so in the and systematic reviews involving ulation.1 A cessation intervention

next 6 months. Furthermore, smokers with mental illness have integrated into treatment for post-

among smokers with mental ill- documented that success is pos- traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

ness, readiness to quit appears to sible. With a stepped-care inter- doubled patients’ odds of quit-

be unrelated to the psychiatric vention tailored to depressed ting.3 And a meta-analysis of sev-

diagnosis, the severity of symp- smokers’ readiness to quit, a 25% en randomized controlled trials

toms, or the coexistence of sub- abstinence rate at 18-month fol- involving smokers with schizo-

stance use. low-up was achieved — a rate phrenia revealed a nearly three-

The third myth is that men- significantly higher than that in fold increase in abstinence rates

tally ill people cannot quit smok- the group that received usual 6 months after treatment among

ing. Although treating tobacco care (advice to quit and referrals those who used bupropion.4

n engl j med 365;3 nejm.org july 21, 2011 197

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 27, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PERSPE C T I V E Smoking and Mental Illness — Breaking the Link

Fourth, many people believe assess their readiness to quit, apply to all hospitalized smok-

that quitting smoking interferes tailor assistance accordingly, and ers, regardless of mental health

with recovery from mental illness, arrange for follow-up. Key strate- status. More generally, we need

eliminating a coping strategy and gies for smokers who are not greater advocacy for smoke-free

leading to decompensation in ready to quit include focusing on environments for mental health

mental health functioning. Five the benefits of change and the treatment; training for clinicians

randomized tobacco-treatment tri- risks associated with tobacco use, in cessation treatment; and sys-

als in patients concurrently receiv- as well as addressing key barriers tems for routinely identifying pa-

ing mental health treatment have to cessation (e.g., stress, fear of tients who smoke, advising ces-

found that smoking cessation did weight gain, and nicotine with- sation, and providing treatment

not exacerbate depression or PTSD drawal). Smokers who are ready to or referral.

symptoms or lead to psychiatric quit should be encouraged to set a The history of tobacco use in

hospitalization or increased use quit date in the next 2 weeks, the mental health field is long

of alcohol or illicit drugs.1 given a prescription for pharma- and troubling. It is time to make

Finally, some argue that smok- cologic cessation treatment (un- effective cessation treatments

ing, which is perceived as having less it is contraindicated), and readily available to all smokers.

distal effects, is the lowest-prior- linked with counseling support. Disclosure forms provided by the author

ity concern for patients with Mood-management strategies may are available with the full text of this arti-

cle at NEJM.org.

acute psychiatric symptoms. Yet also be helpful for smokers with

people with psychiatric disorders current or past mental illness. In- From the Department of Psychiatry, Univer‑

are far more likely to die from tegrating cessation treatment into sity of California, San Francisco, San Fran‑

cisco.

tobacco-related diseases than from existing care results in greater

mental illness. Smokers know to- engagement, greater use of ces- 1. Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Treatment of

bacco use has deadly consequences sation pharmacotherapy, and in- smokers with co-occurring disorders: em‑

phasis on integration in mental health and

and expect health care profession- creased likelihood of abstinence.3 addiction treatment settings. Annu Rev Clin

als to intervene. Indeed, raising Ongoing contact allows clinicians Psychol 2009;5:409-31.

the issue of tobacco use with pa- to monitor and address any chang- 2. Prochaska JJ, Hall SM, Bero LA. Tobacco

use among individuals with schizophrenia:

tients enhances the rapport be- es in psychiatric symptoms dur- what role has the tobacco industry played?

tween patients and clinicians. ing quitting attempts. Relapse Schizophr Bull 2008;34:555-67.

There is growing evidence that rates may be high, and combined 3. McFall M, Saxon AJ, Malte CA, et al. Inte‑

grating tobacco cessation into mental health

smokers with mental illness are and extended use of cessation care for posttraumatic stress disorder: a ran‑

as ready to quit as other smokers medications may be warranted. domized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:

and can do so without any threat There is a critical need to en- 2485-93.

4. Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Efficacy

to their mental health recovery. gage health care providers, poli- and safety of bupropion for smoking cessa‑

Evidence supports the use of most cymakers, and mental health ad- tion and reduction in schizophrenia: system‑

recommended cessation treat- vocates in the effort to increase atic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry

2010;196:346-53.

ments in smokers with mental ill- access to evidence-based tobacco 5. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Clinical

ness (see table). treatment. The Joint Commission practice guideline: treating tobacco use and

Clinicians are therefore encour- plans to adopt revised hospital dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD:

Department of Health and Human Services,

aged to ask all patients about to- standards for tobacco treatment 2008.

bacco use, advise smokers to quit, next January. The standards should Copyright © 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society.

The Clean Air Act and Health — A Clearer View from 2011

Jonathan M. Samet, M.D.

F rom my office, I have views

of downtown Los Angeles

and the San Gabriel Mountains.

these views, and only rarely are

my eyes and throat irritated by

smog when I’m outdoors. The

better than that of the mid-20th

century, when severe oxidant pol-

lution, initially of unknown ori-

Air pollution infrequently obscures Los Angeles air of today is far gins, threatened the health and

198 n engl j med 365;3 nejm.org july 21, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 27, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Alternatives To Addict BehaviorDocument5 pagesAlternatives To Addict BehaviorYungstonNo ratings yet

- Mark Klimek Lecture 4 Canes N CrutchesDocument4 pagesMark Klimek Lecture 4 Canes N CrutchesJohn Desir100% (1)

- Durkhiem On LawDocument2 pagesDurkhiem On LawJyotsnaNo ratings yet

- Social Cognition (Making Sense of People)Document8 pagesSocial Cognition (Making Sense of People)Julia SNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheet Week 5 ORAL COMM PDFDocument2 pagesLearning Activity Sheet Week 5 ORAL COMM PDFMark Allen LabasanNo ratings yet

- Solty 2009Document10 pagesSolty 2009Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Psychological Features of Smokers: Askin Gu Lsen MD and Bu Lent Uygur MDDocument6 pagesPsychological Features of Smokers: Askin Gu Lsen MD and Bu Lent Uygur MDMarianaNo ratings yet

- Walid Sarhan F. R. C. PsychDocument46 pagesWalid Sarhan F. R. C. PsychFree Escort ServiceNo ratings yet

- Nejmcp 2032393Document10 pagesNejmcp 2032393JEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Psychological Effect F NicotineDocument6 pagesPsychological Effect F NicotinehelfiNo ratings yet

- Nihms 122181Document23 pagesNihms 122181Carlos BareaNo ratings yet

- Dong Liu WuDocument29 pagesDong Liu WuJohn Vincent Consul CameroNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Tobacco and Cigarette Consumption and Their Relationship Between Psychological Behaviour - A Narrative ReviewDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Tobacco and Cigarette Consumption and Their Relationship Between Psychological Behaviour - A Narrative ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 2022 Tobacco AdictionDocument10 pages2022 Tobacco AdictionJuan jose Cacua DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento en Patología DualDocument7 pagesTratamiento en Patología DualBalmaNo ratings yet

- Marijuana Facts NIDADocument6 pagesMarijuana Facts NIDALexi PrunellaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Prolonged Cannabis Withdrawal in Young Adults With Lifetime Psychiatric IllnessDocument15 pagesHHS Public Access: Prolonged Cannabis Withdrawal in Young Adults With Lifetime Psychiatric Illnessyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- Factors Relating To Failure To Quit Smoking A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument7 pagesFactors Relating To Failure To Quit Smoking A Prospective Cohort StudySilas SilvaNo ratings yet

- Summary of ResearchDocument7 pagesSummary of Researchapi-549189480No ratings yet

- Review: Managing Smoking CessationDocument9 pagesReview: Managing Smoking CessationARAFAT MIAHNo ratings yet

- Wilson-Comorbid Mood, Psychosis, and Marijuana Abuse Disorders (2008)Document14 pagesWilson-Comorbid Mood, Psychosis, and Marijuana Abuse Disorders (2008)Pau RochaNo ratings yet

- Tobacco Dependence Treatment For Special Populations: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument8 pagesTobacco Dependence Treatment For Special Populations: Challenges and OpportunitiesJonatan VelezNo ratings yet

- Mariguana InformationDocument8 pagesMariguana InformationAlberto Aguirre SanchesNo ratings yet

- Efectividad de Bupropion y Otras IntervencionesDocument12 pagesEfectividad de Bupropion y Otras IntervencionesFranco LaviaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Ajp 2019 05 002Document7 pages10 1016@j Ajp 2019 05 002Dwi Rachma MeilinaNo ratings yet

- A Preliminary Trial: Double-Blind Comparison of Nefazodone, Bupropion-SR, and Placebo in The Treatment of Cannabis DependenceDocument12 pagesA Preliminary Trial: Double-Blind Comparison of Nefazodone, Bupropion-SR, and Placebo in The Treatment of Cannabis DependenceJai KunvarNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Bing 3Document11 pagesJurnal Bing 3Abangnya Dea AmandaNo ratings yet

- LoweD J E Etal 2018 Eur Arch Psychiat Clin NeurosciinpressDocument15 pagesLoweD J E Etal 2018 Eur Arch Psychiat Clin Neurosciinpressjjj-marta8474No ratings yet

- Smoking, Electronic MetDocument7 pagesSmoking, Electronic MetThomas PendersNo ratings yet

- Accepted ManuscriptDocument40 pagesAccepted ManuscriptsueffximenaNo ratings yet

- A Game For SmokersDocument4 pagesA Game For SmokerstifaniNo ratings yet

- Research Paper-2Document9 pagesResearch Paper-2api-741551545No ratings yet

- Smoking in Psychiatric Hospitals: What Is The Role of Nursing Staff?Document5 pagesSmoking in Psychiatric Hospitals: What Is The Role of Nursing Staff?International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- CASE REPORT Family Therapy in Cigarette Addiction: Case ReportDocument5 pagesCASE REPORT Family Therapy in Cigarette Addiction: Case Reportrbatjun576No ratings yet

- Nicotine Dependence: Current Treatments and Future DirectionsDocument17 pagesNicotine Dependence: Current Treatments and Future DirectionsI Komang Ana MahardikaNo ratings yet

- Johnson Et Al. (2017) Smoking Quit With PsilocybeDocument11 pagesJohnson Et Al. (2017) Smoking Quit With PsilocybeJuanmaNo ratings yet

- AJGP 10 2019 Focus Manger Lifestyle Interventions Mental Health WEBDocument4 pagesAJGP 10 2019 Focus Manger Lifestyle Interventions Mental Health WEBisitugasnandasekarbuanaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Smoking Cessation Success in AdultsDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Smoking Cessation Success in AdultsSISNo ratings yet

- ASH Factsheet - Mental Health - v3 2019 27 August 1Document11 pagesASH Factsheet - Mental Health - v3 2019 27 August 1trishahannah.naguimbingNo ratings yet

- Dapus Referat No.4Document7 pagesDapus Referat No.4Muhammad AkrimNo ratings yet

- Role of The Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurse Practitioner PaperDocument10 pagesRole of The Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurse Practitioner PaperemmelineboneNo ratings yet

- Smoking Behaviour and Mental Health Disorders-Mutual Influences and Implications For TherapyDocument22 pagesSmoking Behaviour and Mental Health Disorders-Mutual Influences and Implications For TherapyRizza Faye BalayangNo ratings yet

- N Acetylcysteine For Therapy Resistant Tobacco Use Disorder A Pilot StudyDocument9 pagesN Acetylcysteine For Therapy Resistant Tobacco Use Disorder A Pilot Studytami syhabNo ratings yet

- Intervention For Smoking ReductionDocument15 pagesIntervention For Smoking Reductionben mwanziaNo ratings yet

- Feeling GreatDocument243 pagesFeeling GreatSunny LamNo ratings yet

- Add 12140Document9 pagesAdd 12140imadhassanNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Clinical TrialsDocument8 pagesContemporary Clinical TrialsAzisahhNo ratings yet

- Jama Stop SmokeDocument8 pagesJama Stop Smokeandrew herringNo ratings yet

- Prosser. Biological V Psychosocial Treatments - A Myth About Pharmacotherapy V PsychotherapyDocument3 pagesProsser. Biological V Psychosocial Treatments - A Myth About Pharmacotherapy V PsychotherapyNatalia López MedinaNo ratings yet

- Improving Patient Education About Tobacco Withdrawal and Nicotine Gum Use by Registered Nurses in Inpatient Psychiatry: A Feasibility StudyDocument10 pagesImproving Patient Education About Tobacco Withdrawal and Nicotine Gum Use by Registered Nurses in Inpatient Psychiatry: A Feasibility StudyIzzat HafizNo ratings yet

- National Trends in Cessation Counseling, Prescription Medication UseDocument13 pagesNational Trends in Cessation Counseling, Prescription Medication UseConstantin PopescuNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@jgsDocument10 pages10 1111@jgsFamilia En AcNo ratings yet

- Ats Guidelines Smoking CessationDocument27 pagesAts Guidelines Smoking CessationAna Milena CallejasNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Smoking Cessation and The Cardiovascular PatientDocument11 pagesHHS Public Access: Smoking Cessation and The Cardiovascular PatientNatalia CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Susbatnce Use Disorder PPT FinalDocument19 pagesSusbatnce Use Disorder PPT FinalSalami ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Kahan Et Al, 2019 CommentaryDocument5 pagesKahan Et Al, 2019 CommentaryswagciciliNo ratings yet

- Cannabis: PharmacologyDocument6 pagesCannabis: PharmacologyAntonio Tejero PocielloNo ratings yet

- Pratique D'une Intervention Motivationnelle Pour Les Consommateurs de Cannabis Souffrant de PsychoseDocument8 pagesPratique D'une Intervention Motivationnelle Pour Les Consommateurs de Cannabis Souffrant de Psychosecelia.longuetNo ratings yet

- Smoking Cessation Nursing InterventionsDocument12 pagesSmoking Cessation Nursing Interventionsapi-741272284No ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Tobacco Use in First-Episode PsychosisDocument11 pagesA Systematic Review of Tobacco Use in First-Episode PsychosisVivi DeviyanaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health - CannabisDocument14 pagesMental Health - CannabisEmmanuel Raphael SanturayNo ratings yet

- Add 117 2075Document21 pagesAdd 117 2075hilda ZanibaNo ratings yet

- SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER Group 6Document36 pagesSUBSTANCE USE DISORDER Group 6Salami ibrahimNo ratings yet

- 10' Smoking CessationDocument1 page10' Smoking CessationfabiandionisioNo ratings yet

- Major Components of Curriculum DesignDocument8 pagesMajor Components of Curriculum DesignelynNo ratings yet

- COGSASH Response Ganya Bishnoi 21012009Document3 pagesCOGSASH Response Ganya Bishnoi 21012009Ganya BishnoiNo ratings yet

- Good NotesDocument5 pagesGood NotesMikee BoomNo ratings yet

- Organizational Learning: Sreenath BDocument23 pagesOrganizational Learning: Sreenath BSreenath100% (1)

- Psychometric TestDocument4 pagesPsychometric TestSakshi Mittal100% (1)

- Hilton Hotel ColomboDocument23 pagesHilton Hotel Colombokokila amarasingheNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Portfolio AssessmentDocument11 pagesChapter 10 Portfolio Assessmentapi-469710033No ratings yet

- Session 6-9 CFU - NUR 152 RLEDocument3 pagesSession 6-9 CFU - NUR 152 RLEDarwin QuirimitNo ratings yet

- Scied 204 Teaching Science Junabel7 Wilnie OfficeDocument32 pagesScied 204 Teaching Science Junabel7 Wilnie OfficeLyka Jane Genobatin BinayNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8 Perdev Understanding The SelfDocument13 pagesLesson 8 Perdev Understanding The SelfJasmin BasadreNo ratings yet

- HypnosisDocument18 pagesHypnosisapi-26413035No ratings yet

- Asm 1 Manh Cuong (BTEC HN)Document18 pagesAsm 1 Manh Cuong (BTEC HN)RyderNo ratings yet

- Neha HR Thesis 3Document21 pagesNeha HR Thesis 3Bidisha BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document14 pagesChapter 8Nhật DuyNo ratings yet

- LLU0021 EnglezaDocument52 pagesLLU0021 EnglezaNohai JojoNo ratings yet

- Unit IDocument2 pagesUnit ISNo ratings yet

- Buddying Programme: Supporting Employee InductionDocument5 pagesBuddying Programme: Supporting Employee InductionAnggitfenNo ratings yet

- Employee Development - PPT 9Document39 pagesEmployee Development - PPT 9sachinthestar2007No ratings yet

- GAS - General Adaptation SyndromeDocument2 pagesGAS - General Adaptation SyndromeabassalishahNo ratings yet

- Emotional ProcessingDocument4 pagesEmotional ProcessingLucy FoskettNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesLesson PlanMr. Cliff BhattNo ratings yet

- Course-Syllabus-Social ArtsDocument4 pagesCourse-Syllabus-Social Artsannelyn velascoNo ratings yet

- (1983) Sense of Humor As A Moderator of The RelationDocument13 pages(1983) Sense of Humor As A Moderator of The Relationarip sumantriNo ratings yet

- Ms Liji Raichel Kurian, Caritas College of NursingDocument52 pagesMs Liji Raichel Kurian, Caritas College of NursingJOSLINNo ratings yet

- Havinghurst Developmental TaskDocument1 pageHavinghurst Developmental TaskHazel DialinoNo ratings yet