Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe

Uploaded by

aurimiaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Ebook PDF Living Sociologically Concepts and ConnectionsDocument61 pagesEbook PDF Living Sociologically Concepts and Connectionsina.mccrea979100% (50)

- Job CostingDocument35 pagesJob Costingjpg17100% (2)

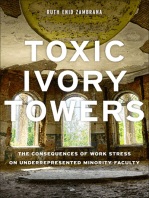

- Toxic Ivory Towers: The Consequences of Work Stress on Underrepresented Minority FacultyFrom EverandToxic Ivory Towers: The Consequences of Work Stress on Underrepresented Minority FacultyNo ratings yet

- Critical Sexual Literacy: Forecasting Trends in Sexual Politics, Diversity and PedagogyFrom EverandCritical Sexual Literacy: Forecasting Trends in Sexual Politics, Diversity and PedagogyNo ratings yet

- CAPE Sociology SyllabusDocument8 pagesCAPE Sociology SyllabusDari Debauchery100% (1)

- Privilege, Power, and Difference-2Document7 pagesPrivilege, Power, and Difference-2Rana AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Research Topics of SociologyDocument8 pagesResearch Topics of SociologyM BNo ratings yet

- Diversity in SchoolDocument72 pagesDiversity in SchoolCronopialmente100% (1)

- The Romani Women's MovementDocument284 pagesThe Romani Women's Movementaurimia100% (2)

- Φίγγου και συνεργάτες-επιπολιτισμοποίηση ως διαγενεακή διαδικασίαDocument33 pagesΦίγγου και συνεργάτες-επιπολιτισμοποίηση ως διαγενεακή διαδικασίαkaterinaNo ratings yet

- Creating An Inclusive Society Evidence From Social Indicators and Trends - RobertoFoaPaperDocument37 pagesCreating An Inclusive Society Evidence From Social Indicators and Trends - RobertoFoaPaperRosyada Amiirul HajjNo ratings yet

- Race Relations and Racism in The LGBTQ Community of Toronto: Perceptions of Gay and Queer Social Service Provide..Document39 pagesRace Relations and Racism in The LGBTQ Community of Toronto: Perceptions of Gay and Queer Social Service Provide..Pau MendozaNo ratings yet

- Giulia Suciu - Feminism and Gender Inequality in RomaniaDocument9 pagesGiulia Suciu - Feminism and Gender Inequality in RomaniaIrina IliseiNo ratings yet

- Zachos, Dimitrios, Institutional Racism? Roma Children, Local Community and School Practices, Journal For Critical Education Policy Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2, Pp. 53-66. Institutional RacismDocument14 pagesZachos, Dimitrios, Institutional Racism? Roma Children, Local Community and School Practices, Journal For Critical Education Policy Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2, Pp. 53-66. Institutional RacismDimitris ZachosNo ratings yet

- 14.3.1 Shamsul AB M. Fauzi BSDocument17 pages14.3.1 Shamsul AB M. Fauzi BSArdian DekwantoNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Transgender and Gender Diverse Representation in The Media: Impacts On The PopulationDocument18 pagesThe Rise of Transgender and Gender Diverse Representation in The Media: Impacts On The PopulationJunior LopesNo ratings yet

- Sexual Prejudice and Stigma of LGBT People: PHD Candidate, Adisa TelitiDocument10 pagesSexual Prejudice and Stigma of LGBT People: PHD Candidate, Adisa TelitiAlyssa EucylleNo ratings yet

- Gender, Development, and DiversityDocument95 pagesGender, Development, and DiversityOxfamNo ratings yet

- Popular Explanations of Poverty in EuropeDocument20 pagesPopular Explanations of Poverty in EuropeKőmivesTimeaNo ratings yet

- Majda Elidrissi, S2 Research MethodologyDocument14 pagesMajda Elidrissi, S2 Research MethodologyMajda Elidrissi ElalouaniNo ratings yet

- Female Household HeadshipDocument71 pagesFemale Household HeadshipCarmina FernandezNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Science and Higher Education: Social Anthropology (Anth 1012)Document22 pagesMinistry of Science and Higher Education: Social Anthropology (Anth 1012)Amots AbebeNo ratings yet

- Cultural Inequality and Sustainable DevelopmentDocument16 pagesCultural Inequality and Sustainable DevelopmentMd. Mahmudul AlamNo ratings yet

- Format Penulisan UiDocument19 pagesFormat Penulisan UiWahyumiNo ratings yet

- Gender Work Organization - 2020 - Bourabain - Everyday Sexism and Racism in The Ivory Tower The Experiences of EarlyDocument20 pagesGender Work Organization - 2020 - Bourabain - Everyday Sexism and Racism in The Ivory Tower The Experiences of EarlyRoseli MachadoNo ratings yet

- Languague, Culture and SocietyDocument10 pagesLanguague, Culture and SocietyHuyền TrangNo ratings yet

- Seminar 3Document4 pagesSeminar 3kidpursuitNo ratings yet

- Lesbian Relationship ThesisDocument9 pagesLesbian Relationship Thesisreznadismu1984100% (2)

- Childhood and Sexuality - Contemporary Issues and Debates (2018)Document307 pagesChildhood and Sexuality - Contemporary Issues and Debates (2018)Ofelia KerrNo ratings yet

- Critical race theory and inequality in the labour market: Racial stratification in IrelandFrom EverandCritical race theory and inequality in the labour market: Racial stratification in IrelandNo ratings yet

- (Julie McLeod and Katie Wright) The Talking Cure in Everyday Life Gender, Generations and FriendshipDocument19 pages(Julie McLeod and Katie Wright) The Talking Cure in Everyday Life Gender, Generations and FriendshipValerita83No ratings yet

- SODSOD Module 4Document2 pagesSODSOD Module 4ryanNo ratings yet

- Yashasvi Sharma 1120202148 SEM IV Law Poverty and DevelopmentDocument14 pagesYashasvi Sharma 1120202148 SEM IV Law Poverty and DevelopmentYashasvi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Science and Higher Education: Social Anthropology (Anth 1012)Document30 pagesMinistry of Science and Higher Education: Social Anthropology (Anth 1012)Natty Nigussie100% (1)

- Worldconnectors Statement Gender and DiversityDocument16 pagesWorldconnectors Statement Gender and DiversityWorldconnectorsNo ratings yet

- Contained Mobility and The Racialization PDFDocument18 pagesContained Mobility and The Racialization PDFJulian Andres MarinNo ratings yet

- A Study of Beggars Characteristics and Attitude of People Towards TheDocument14 pagesA Study of Beggars Characteristics and Attitude of People Towards TheLaiKamChongNo ratings yet

- Transphobic Violence in Educational CentersDocument15 pagesTransphobic Violence in Educational CentersamayalibelulaNo ratings yet

- Development and Social DiversityDocument113 pagesDevelopment and Social DiversityOxfamNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four Marginalized, Minorities, and Vulnerable GroupsDocument73 pagesChapter Four Marginalized, Minorities, and Vulnerable GroupsRoNo ratings yet

- Articol RomiDocument22 pagesArticol RomiIasmin BodeaNo ratings yet

- State, Societyand EnvironmentDocument6 pagesState, Societyand EnvironmentDoreen SamuelNo ratings yet

- ABS426 FinalDocument7 pagesABS426 FinalNic ConnorsNo ratings yet

- Sociology Senior Thesis ExamplesDocument4 pagesSociology Senior Thesis ExamplesSarah Morrow100% (1)

- Capurihan Et Al., 2023Document11 pagesCapurihan Et Al., 2023Angela Mae SuyomNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Educational DevelopmentDocument9 pagesInternational Journal of Educational DevelopmentHawi DadhiNo ratings yet

- GlobalizationDocument13 pagesGlobalizationMOUMITA MOKNDALNo ratings yet

- Gender and HealthDocument19 pagesGender and Healthlaura davidNo ratings yet

- 326-Article Text-585-1-10-20190926Document16 pages326-Article Text-585-1-10-20190926Mara KarlbergNo ratings yet

- Anti-Roma Kendeetal Ijir2017Document17 pagesAnti-Roma Kendeetal Ijir2017Lacatus OlimpiuNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotypes PPDocument4 pagesGender Stereotypes PPArceusizel 1No ratings yet

- Precious Research ProposalDocument10 pagesPrecious Research ProposalTatenda Precious KativuNo ratings yet

- Societal Sources of Negative Attitudes Against The RomaDocument18 pagesSocietal Sources of Negative Attitudes Against The RomaLacatus OlimpiuNo ratings yet

- Ethnic and Racial Disparities in EducationDocument4 pagesEthnic and Racial Disparities in EducationRam MulingeNo ratings yet

- Status Questionis: Home List Theses Contence Previous NextDocument72 pagesStatus Questionis: Home List Theses Contence Previous NextMit. Manta , PhDNo ratings yet

- Dissertation MulticulturalismDocument5 pagesDissertation MulticulturalismDltkCustomWritingPaperUK100% (1)

- Social ExclusionDocument49 pagesSocial ExclusionxxxxdadadNo ratings yet

- Benefits and Challenges of Interracial Marriage in UKDocument6 pagesBenefits and Challenges of Interracial Marriage in UKعمر الخيامNo ratings yet

- Opportunities For Roma InclusionDocument36 pagesOpportunities For Roma InclusionUNDP in Europe and Central AsiaNo ratings yet

- MWP LS 2013 03 Modood - CleanedDocument19 pagesMWP LS 2013 03 Modood - CleanedMelvin SalibaNo ratings yet

- Midterm Test Bkep - 30% - May 2020Document3 pagesMidterm Test Bkep - 30% - May 2020Hồng LêNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity and Anti-PovertyDocument12 pagesCultural Diversity and Anti-PovertyHaryo BagaskaraNo ratings yet

- Rachel Lea - The Shitful BodyDocument12 pagesRachel Lea - The Shitful BodyaurimiaNo ratings yet

- Two Exhumations and An Attempted Theft: The Posthumous Biography of ST Cuthbert in The Nineteenth Century and Its Historicist NarrativesDocument20 pagesTwo Exhumations and An Attempted Theft: The Posthumous Biography of ST Cuthbert in The Nineteenth Century and Its Historicist NarrativesaurimiaNo ratings yet

- Massino, Jill - Constructing The Socialist Worker - Gender, Identity and Work Under State Socialism in Braşov, RomaniaDocument30 pagesMassino, Jill - Constructing The Socialist Worker - Gender, Identity and Work Under State Socialism in Braşov, RomaniaaurimiaNo ratings yet

- Heidi A. Campbell, Ruth Tsuria (Eds.) - Digital Religion Understanding Religious Practice in Digital MediaDocument309 pagesHeidi A. Campbell, Ruth Tsuria (Eds.) - Digital Religion Understanding Religious Practice in Digital Mediaaurimia100% (2)

- VAN DRIEL, Mels - With The Hand. A Cultural History of MasturbationDocument258 pagesVAN DRIEL, Mels - With The Hand. A Cultural History of Masturbationaurimia100% (2)

- Jud Nirenberg - (Ed.) - Gypsy Sexuality. Romani and Outsider Perspectives On IntimacyDocument267 pagesJud Nirenberg - (Ed.) - Gypsy Sexuality. Romani and Outsider Perspectives On IntimacyaurimiaNo ratings yet

- Ednan Aslan, Marcia Hermansen (Eds.) - Religion and Violence - Muslim and Christian Theological and Pedagogical Reflections (2017)Document266 pagesEdnan Aslan, Marcia Hermansen (Eds.) - Religion and Violence - Muslim and Christian Theological and Pedagogical Reflections (2017)aurimiaNo ratings yet

- Madawi Al-Rasheed, Marat Shterin - Dying For Faith - Religiously Motivated Violence in The Contemporary World (2009)Document257 pagesMadawi Al-Rasheed, Marat Shterin - Dying For Faith - Religiously Motivated Violence in The Contemporary World (2009)aurimiaNo ratings yet

- Wolfgang Palaver - Transforming The Sacred Into Saintliness - Reflecting On Violence and Religion With René Girard (2020)Document96 pagesWolfgang Palaver - Transforming The Sacred Into Saintliness - Reflecting On Violence and Religion With René Girard (2020)aurimiaNo ratings yet

- ROGERS, Katharine M. - CatDocument210 pagesROGERS, Katharine M. - CataurimiaNo ratings yet

- KLOTS, Yasha - Varlam Shalamov Between Tamizdat and The Soviet Writers' Union (1966-1978)Document30 pagesKLOTS, Yasha - Varlam Shalamov Between Tamizdat and The Soviet Writers' Union (1966-1978)aurimiaNo ratings yet

- The Grey Zones of Witnessing: Levi, Améry, Shalamov: 1 Entangled MemoriesDocument21 pagesThe Grey Zones of Witnessing: Levi, Améry, Shalamov: 1 Entangled MemoriesaurimiaNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Technology For Rural DevelopmentDocument12 pagesTransfer of Technology For Rural DevelopmentiamgonnarocksNo ratings yet

- SBQ Surprised - Ss GuideDocument23 pagesSBQ Surprised - Ss GuideSaffiah M Amin100% (1)

- ISO 27001:2013 Gap AnalysisDocument8 pagesISO 27001:2013 Gap AnalysisOubaouba FortuneoNo ratings yet

- Chapter-1 F&B Staff OrganisationDocument3 pagesChapter-1 F&B Staff OrganisationAnurag SehrawatNo ratings yet

- Assistant Manager Cooks: Manag ERDocument6 pagesAssistant Manager Cooks: Manag ERSharon AmondiNo ratings yet

- Resume For Union JobDocument4 pagesResume For Union Jobrxfzftckg100% (1)

- BIR Citizen - S Charter 2021 EditionDocument999 pagesBIR Citizen - S Charter 2021 EditionRosalie FeraerNo ratings yet

- 5.19 Ethics & Culture in A Digital WorkplaceDocument4 pages5.19 Ethics & Culture in A Digital WorkplacejfariasNo ratings yet

- Business To Business Marketing: International Islamic University Islamabad, Fall 2015Document11 pagesBusiness To Business Marketing: International Islamic University Islamabad, Fall 2015Ciprian PaulNo ratings yet

- Janata Bank Micro CreditDocument25 pagesJanata Bank Micro CreditMahfoz KazolNo ratings yet

- Annals 2016 0108Document77 pagesAnnals 2016 0108kashifNo ratings yet

- TenderDocument2 PlumbingDocument10 pagesTenderDocument2 PlumbingAadarsh KoliNo ratings yet

- CS8T1 - Engineering Economics and Management-Course Material Feb 2021Document163 pagesCS8T1 - Engineering Economics and Management-Course Material Feb 2021bandaiah gnNo ratings yet

- Employment Agreement (With ESOPs)Document15 pagesEmployment Agreement (With ESOPs)RandoNo ratings yet

- Contract No. IQ-P20-Package 3B Ver 01 PDFDocument274 pagesContract No. IQ-P20-Package 3B Ver 01 PDFAnonymous xqOeyJh9100% (1)

- Case Study of Disadvantaged Families (Poorest of The Poor) of Naogaon District Towards Possible Linkage Under The Coverage of SSNPDocument21 pagesCase Study of Disadvantaged Families (Poorest of The Poor) of Naogaon District Towards Possible Linkage Under The Coverage of SSNPJahid Hasnain0% (1)

- Delve 2020 State of The Sector Report 0504Document170 pagesDelve 2020 State of The Sector Report 0504eliotsmsNo ratings yet

- Leave Policy Template For Human ResourcesDocument12 pagesLeave Policy Template For Human Resourcesvignesh RNo ratings yet

- Preclaro Vs Sandiganbayan CDDocument1 pagePreclaro Vs Sandiganbayan CDKenneth Ray AgustinNo ratings yet

- HRM Test 2Document2 pagesHRM Test 2sivapathasekaranNo ratings yet

- People v. GatchalianDocument1 pagePeople v. GatchalianDarryl CatalanNo ratings yet

- Construction Safety Benchmarking: June 2006Document10 pagesConstruction Safety Benchmarking: June 2006Eng-Sharaf Al-smadiNo ratings yet

- Guideline For The Employers On Deducting Withholding Tax Paye From 01-01-2020 To 31-03-2020Document4 pagesGuideline For The Employers On Deducting Withholding Tax Paye From 01-01-2020 To 31-03-2020kNo ratings yet

- Managing General Overhead Costs FinalDocument43 pagesManaging General Overhead Costs FinalCha CastilloNo ratings yet

- Abesco Corp v. Ramirez - Case DigestDocument2 pagesAbesco Corp v. Ramirez - Case DigestLawrence EsioNo ratings yet

- 1 - PERTEMUAN KE 13 Kepemimpinan Di Hospitality Industry (Lanjutan)Document14 pages1 - PERTEMUAN KE 13 Kepemimpinan Di Hospitality Industry (Lanjutan)Deby Aini SaputriNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Leadership Leads To Competitive Advantage - MercerDocument5 pagesInclusive Leadership Leads To Competitive Advantage - MercerRayno MareeNo ratings yet

- Unit - 1 Industrial Relations - Definition and Main AspectDocument14 pagesUnit - 1 Industrial Relations - Definition and Main AspectSujan ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Module 8 Health and Safety (Final Draft, After Comment, Sent) 1Document29 pagesModule 8 Health and Safety (Final Draft, After Comment, Sent) 1Tewodros Tadesse100% (1)

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe

Uploaded by

aurimiaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe

Uploaded by

aurimiaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/313899271

“Challenges faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education,

Employment, Health and Housing: focus on Czech Republic,

Romania and Greece”

Article · January 2015

CITATIONS READS

3 226

3 authors, including:

Roxana Andrei George Martinidis

University of Coimbra

3 PUBLICATIONS 7 CITATIONS

13 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

(Re)sources for Conflict and Cooperation in the Caspian – Black Sea region: the impact of energy dynamics View project

Building Ontological (In)Securities in the Caspian - Black Sea Region View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Roxana Andrei on 16 April 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on

Education, Employment, Health and Housing - Focus on

Czech Republic, Romania and Greece

Roxana ANDREI

e-mail: roxanna.andrei@gmail.com

George MARTINIDIS

e-mail: gmart55@yahoo.com

Tana TKADLECOVA

e-mail: tana.tkadlecova@gmail

Abstract

Roma women in Europe are probably discriminated

against more than any other group, facing discrimination both

for their ethnic origin and their gender. Due to being part of a

minority facing isolation, poverty, discrimination and often

embracing masculine social values, Roma women have to face

multiple challenges. However, the nature of these challenges

varies between the different states, as is evident in the case of the

three countries examined here. Although positive steps have been

taken in all three countries lately, in practice, Roma girls and

women still face discrimination with respect to equal access to

education, employment, health care and housing. Current

policies and initiatives do not have a significant impact because

they are most often designed in a top-down approach, with little

or no consultation and direct involvement of the Roma

community. What is needed to produce a real impact is a

different approach: a bottom-up initiative taking place within

Roma communities, both geographically and organisationally.

Keywords: Roma women, discrimination, integration, minorities,

social policies, vulnerable social groups, education, employment,

health, housing

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

INTRODUCTION

Discrimination against Roma women has a structural and pervasive

character, deeply rooted in the history and practices of many European

cultures and communities, and impregnating all sectors and areas throughout

their lives. Inequalities experienced by Roma women have a cumulative

effect, in the sense that discrimination experienced in one area at one stage of

their lives will lead to subsequent disadvantages later on. Discrimination thus

becomes a multi-layered phenomenon for Roma women, who are often

subjected to multiple discrimination.

Roma women face discrimination shared by their ethnic group in

terms of access to employment, education, health care and housing, but also

related to their gender, in the broader context of the discrimination of women,

especially in more traditional societies, as well as in the specific context of

Roma culture and role of Roma women. This leads to one of the „dilemmas of

intersectionality” (Oprea, 2005, p. 140): being forced to choose between their

gender and their race in an environment where they are constructed as

mutually exclusive. “There is a false dichotomy between women’s rights and

Romani-ness where they become construed as mutually exclusive, ultimately

forcing Romani women to chose between their race and gender” (Oprea, 2005,

p. 140).

In Europe, Roma are probably discriminated against more than any

other group. They seem to be an invisible minority living on the fringes of

European ‘mainstream’ society. The number of Roma in Europe is estimated

between 10 and 12 million, with more than half of them in the EU, making

them the largest minority in Europe by far. Most of the European Roma are of

Indian origin, moving from country to country the last 1,000 years to escape

persecution, like so many other minorities in Europe’s tumultuous history

(ENAR-ERIO, 2011). However, European Roma are far from a homogeneous

group in terms of origin, nationality, religion, culture or way of life. Perhaps

the strongest element they have in common is the degree of discrimination that

they face. This is even truer for the Roma women, who can face a double

discrimination, based on their gender as well as on their ethnicity.

The current article focuses on identifying the main challenges and

opportunities faced by Roma women with respect to access to education,

employment, health care and housing in Czech Republic, Romania and

Greece. The effect of the existing measures and policies is critiqued, and

feedback from Roma women is collected with respect to their impact. In an

attempt to work close to our target group, we have interviewed two

representatives of the Roma women community in order to best identify the

324 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

most appropriate recommendations for changing and improving the condition

of Roma women on the way to their full empowerment.

I. THEORETICAL APPROACHES: EMPOWERMENT, DISCRIMINATION,

ROMA CULTURE, VALUES AND BEHAVIOURAL PATTERNS

To be disempowered means to be denied choice, while

empowerment refers to the processes by which those who have

been denied the ability to make choices acquire such ability. In

other words, empowerment entails change (Kabeer, 2005, p. 13).

The process of empowerment can be regarded as an internal one,

deeply rooted in the meaning, motivation, and purpose that individuals bring

to their actions, along with the external actions of decision-making. It is about

how people see themselves, thereby leading to other people’s perception on

them. The process also has external elements, such as the way in which

resources are distributed. “If a woman’s primary form of access to resources is

as a dependent member of the family, her capacity to make strategic choices is

likely to be limited” (Kabeer, 2005, p.15).

According to social psychology, discrimination refers to unjustifiable

negative behaviour towards a group or its members, where behaviour is

adjudged to include actions towards and judgements about, group members

(Al Ramiah et al., 2010, p.85). Discrimination is closely linked with other

social phenomena such as prejudice or stereotypes, but it is a distinct concept,

and social psychologists are careful to emphasise the distinction.

Discrimination can be fuelled by stereotypes and prejudice, but itself refers to

an outcome behaviour, which is unfortunately very common in every part of

the world and every sphere of life (Link & Phelan, 2001, p.365).

In addition, discrimination has many dire consequences that are often

more pervasive and far-reaching than is commonly assumed. Other than the

obvious issues with housing, education, healthcare and other fundamental

human rights, various study findings show that the stigma of discrimination

can lead to anxiety, stress and other problems related to mental well-being, to

underperforming in professional and personal capacities, and to poorer health

outcomes even if the same healthcare standards are provided (Al Ramiah et

al., 2010, p.103).

One needs to tread carefully in assessing Roma values and

behaviours, as a number of common myths and stereotypes have created an

image of Roma society as extremely “primitive” and “backwards” (ENAR-

ERIO, 2011). Modern studies show that masculine social values are quite

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 325

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

strong within the European Roma. This is reflected in various aspects of social

life such as marriage, sexuality and domestic abuse. For example, nearly a

third of Roma parents in Europe that prefer to get their daughter married

before she completes basic education to make sure she does not start sexual

life before the marriage,, This proportion is quite high but not as high as

Roma stereotypes seem to indicate. Still, it is roughly three times the

percentage of non-Roma parents. However, there are staggering differences

among Roma parents in these percentages if age and education are taken into

account, so these masculine values are changing for younger and more

educated people, especially for more educated Roma women (Cukrowska &

Kocze, 2013, p.70).

Overall, masculine social values are still prominent within Roma

society and culture, although there seems to be a pattern of change. Still, it

would be extremely biased to attribute the prevalence of these values to some

“inherent backwardness” of Roma culture or society as local media are

sometimes quick to do (Petrova & Cahn, 2001, p.18). For a long time, similar

masculine values were equally prominent in the non-Roma groups of the

countries under study before they changed along with the shape of the

societies in these countries (Beynon, 2002). As the Roma in these countries

were generally excluded from the beneficial social developments, the

continued prevalence of chauvinist values can be associated with the

socieconomic and educational lag that the Roma experience. This notion is

supported by the findings that the impact of masculine values on Roma society

is much weaker for better educated Roma, being roughly the same as that for

non-Roma (Cukrowska & Kocze, 2013, p.69). In any case, the main victims of

the prevalence of masculine values seem to be Roma women, who become the

targets of multiple discrimination, both from within and from without Roma

society (Ziomas, Bouzas & Spyropoulou, 2011, p.13).

Positive steps have been taken in the last years to address the issue of

Roma women discrimination, both at domestic level, as well as at the

international level. However, there is still much to be done with respect to

their empowerment, a lengthy and challenging process. Of significant

importance is the prioritization of Roma-related issues and of the

empowerment of women on the international agenda. In this sense, the

Decade of Roma Inclusion (2005-2015), a project supported by 12

participating countries – Czech Republic, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Bosnia

and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia,

Slovakia and Spain (plus Slovenia and US as external observers), focuses on

improving socio-economic conditions and inclusion for Roma population

(ERRC, 2013). The priority areas are education, housing, employment and

326 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

health. Focus of the national projects is on self-employment and

entrepreneurship by providing business skills trainings and promoting

traditional Roma crafts (UNDP, 2006).

II. ROMA WOMEN AND ACCESS TO EDUCATION

1. Main problems related to education and their impact on Roma

women and girls

Poverty, early marriages and giving birth at a young age have been

identified as the main causes of school absenteeism and drop-out for Roma

girls in Central and Eastern Europe by the UNDP/ILO Survey. This survey

concluded, school attendance drops when “the opportunity costs of sending

children to school rise in households with falling incomes” (UNDP, 2002, p.

54). Poverty and associated factors such as the health risks associated with

poor-quality housing have also been identified as “possible causal factors for

the lower educational status of Roma” (UNDP, 2006, p. 29).

1.1 Roma culture and its role on access to education

In the framework of Roma culture and its impact on the development

of Roma women, it is generally considered that an important source of

discrimination stems from the Roma communities themselves being linked to

the role of women in Roma culture and family structure (Corsi et al., 2008). In

the traditional patriarchal Roma family, women are expected to assume a

subordinate position and to be in charge of the family from as early as 11

years old. Early marriages of Roma girls, a widespread practice and the main

intersectional ethnic-gender issue faced by them in Romania, have stirred up

political, cultural and legislative debates. By entering early marriages, Roma

girls are prevented from going to school and later on from entering the formal

labour market, being expected to marry and to care for their families already

since 15-16 years old. At the same time, divorce is not common among Roma

women, both in traditional and more modern marriages (Corsi et al., 2008). In

addition, lacking education and a secure job, Roma women face an increased

vulnerability, especially if they lose the support and acceptance of their

community, being thus exposed to illegal employment, trafficking in human

beings or delinquency.

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 327

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

Based on the sample averages of working age individuals (16-64) of

the 2011 UNDP/WB/EC regional survey on Roma communities, Roma males

spend on average 6.71 years in education, while Roma women 5.66 years,

significantly below the non-Roma population averages: 10.95 and 10.7. As a

consequence, “Romani women are subject both to ethnic as well as gender

gaps when it comes to the time spent in an educational system” (Cukrowska

and Kóczé, 2013, p. 14).

Moreover, the difference in the average number of years spent in

education between Roma and non-Roma women increases with age, possibly

due to the fact that Roma are more likely to leave school. If Roma males aged

18-34 spend 6.5 years in the education system compared to Roma females

who spend 5.8 years, in the 35-49 age group Roma males spend an average of

7 years in school while Romani females only 5.7 years (Cukrowska and

Kóczé, 2013). Also, 28% of Romani women aged 16 to 64 have no formal

level of education compared to 18% of Romani men and 2% of non-Romani

women.

Consequently, dropout rates amongst Roma are more than three times

higher than amongst non-Roma, with a slightly higher rate among Roma

women compared to Roma men. Therefore, ethnicity seems to play a more

important role than gender with respect to drop out rates, affecting Roma girls

and boys equally. UNDP/WB/EC regional survey on Roma communities also

highlights the fact that the differences in the literacy rate are mainly due to

ethnicity, while gender is less obvious as a differentiating criteria, non-Roma

women displaying slightly lower literacy rates than men (Cukrowska and

Kóczé, 2013).

However, “culture is constantly negotiated and is multiple and

contradictory” and Romani culture “is not constructed under ‘hermetically

sealed’ boxes” (Volpp, see Oprea, 2005, p. 137). Notwithstanding the role of

culture in the status of Roma women, Oprea (2005) draws attention to the risk

of overestimating its role, while ignoring the importance of other factors, of

turning a blind eye to the practices that are harmful to women within this

group in the name of preserving cultural autonomy or criticizing in a way that

portrays the entire culture as primitive.

Traditions related to early marriages of Roma girls and their level of

education and access on the labour market are closely entangled in a vicious

circle. On one hand, being expected to enter early marriages, Roma girls are

prevented from going to school and later on from accessing the formal labour

market. On the other hand, facing a double ethnic and gender discrimination,

Roma girls lack equal treatment in schools and are highly discriminated

against when it comes to employment; therefore, their families see no other

328 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

viable option for them than marriage and the role of care givers for their

families.

There are also limits to education as a mean to women’s

empowerment, in the absence of a gender-awareness system and curricula.

Thus, “in societies that are characterised by extreme forms of gender

inequality ... where women’s role in society is defined purely in reproductive

terms, education is seen in terms of equipping girls to be better wives and

mothers, or increasing their chances of getting a suitable husband” (Kabeer,

2005, p. 17). Moreover, gender stereotyping is reproduced in the school

curricula and “can limit the development of the natural talents and abilities of

boys and girls, women and men, in their educational and professional

experiences as well as life opportunities in general” (Council of Europe, 2014,

p. 9).

With respect to Roma, references to them are almost absent in the

curricula, or quoted in pejorative contexts in the literature. However, steps

have been taken in some countries to improve this situation. In Romania,

topics such as the genocide of the Roma during the Second World War are

being taught in schools and high schools.

1.2 Czech Republic, Greece and Romania: Roma girls and women,

and their access to education

Czech Republic

The most severe problems encountered by Roma girls, along with the

Roma boys, regarding access to education are the overrepresentation of Roma

pupils in special schools

for children with mental

disabilities, despite the

absence of a disability,

and the segregation of

Roma pupils from the

non-Roma in ordinary

schools.

In the D.H. and

others v. the Czech

Republic, 2007, the

European Court of

Human Rights found

violation of Art.14

(prohibition of

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 329

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

discrimination) in conjunction with Art.2 of Protocol No. 1 (right to

education) of the European Convention of Human Rights: 18 applicants of

Roma origin were discriminated against in the enjoyment of their right to

education on account of their race or ethnic origin, being placed in special

schools for children (zvláštní školy) for children with learning difficulties.

The Court noted that the Czech authorities had admitted that in 1999 Roma

pupils made up between 80 % and 90 % of the total number of pupils in some

special schools. Moreover, although the exact percentage of Roma children in

special schools at present is difficult to establish, their number is

disproportionately high and Roma pupils represent the majority of the pupils

in special schools (European Court of Human Rights, 2007). Placing Roma

children in special schools for mentally disabled pupils prevents them from

accessing good education and employment opportunities later on compared to

the non-Roma children (European Roma Information Office, 2013; UNICEF,

2011; UNICEF, 2009).

Ordinary schools remain highly segregated. On one hand, segregation

in schools is linked to housing segregation, with Roma communities and

schools separated from the Czech ones. On the other hand, Roma parents do

not trust the ordinary schools fearing that their children will be there subjected

to discrimination and violence (European Commission against Racism and

Intolerance, 2009a, p. 27).

Greece

Roma children are still confronted with the refusal of schools to enrol

them, often under the pressure of non-Roma parents. Even when allowed to

register, Roma

children are placed in

separate classes,

increasing the

segregation. In the

Sampanis and Others

v. Greece, 2005, the

European Court of

Human Rights found

violation of Art.14

(prohibition of

discrimination) in

conjunction with

Art.2 of Protocol No.

330 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

1 (right to education) of the European Convention of Human Rights: 11

applicants, Greek nationals of Roma origin, were refused enrolment in the

primary school by the principals of two schools and were later on placed in

special classes, in an annexe to the main Aspropyrgos primary school

building, a measure which the applicants claimed was related to their Roma

origin. The decision to segregate the Roma pupils followed the non-Roma

parents’ protests about the admission to primary school of Roma children and

blockade of the school, demanding that the Roma children be transferred to

another building, with the police intervening several times to prevent illegal

acts being committed against pupils of Roma origin (European Court of

Human Rights, 2008).

To highlight the impact of the intersection between ethnicity and

gender on the level of education of Roma women, the European Commission

found that in Greece, for example, Roma men have lower levels of illiteracy

than Roma women since they are more exposed to an environment where they

can learn how to read and write (European Commission against Racism and

Intolerance, 2009b).

Romania

Roma pupils in Roma record high rates of dropout and absenteeism,

although, according to European Commission against Racism and Intolerance

(2006), discrimination is not a reflection of institutional discrimination.

In this sense, it is

worth mentioning

that in the

Notification no.

29323/20.04.2004,

the Ministry of

Education and

Research has

banned all forms

of segregation in

Romanian schools.

School mediators

facilitated the

integration of

Roma pupils,

technical training

was provided to

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 331

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

Roma children who have left school and dedicated places have been reserved

for Roma students in Romanian universities. However, segregation still

persists in practice, Roma pupils being often forced to attend lower standards

schools or being placed in separate classes (European Commission against

Racism and Intolerance, 2006, p. 31).

Poverty and living in remote areas seem to be the main reasons

hindering Roma children to attend school, despite the authorities’ support

measures. Moreover, as in the case of adults, many Roma children do not

identify themselves as such and do not wish to study Roma language and

history, facing a self-esteem problem (European Commission against Racism

and Intolerance, 2006). Negative attitudes on the side of teachers and

colleagues still persist, or, in the words of Lia Gaudi, our Roma interview

guest, “there are so many negative examples of Roma students fighting much

more that many of the majority for their place in the academic environment,

and the details of these stories, just make integration, tolerance, equality and

‘peace among people’ fade”.

The main challenges faced by Roma girls and women with respect to

education and schooling in Romania have been identified to be: some aspects

of Roma culture and traditions, rejection by the society, general stereotypes

among teachers and public policies.

III. ROMA WOMEN AND ACCESS TO EMPLOYMENT

The transition from socialist to market economy in Central and

Eastern Europe (CEE) has brought many changes and challenges to the

population of the region. The income inequality and unemployment has risen

and Roma people, particularly women, became even more vulnerable

(O’Higgins, 2010; O’Higgins and Ivanov, 2006; Ringold et al, 2005).

“Because of their low skills levels, as well as discrimination in the labour

market, Roma were frequently among the first to be laid off; this has directly

influenced Roma welfare” (Ringold et al, 2005, p. 38).

Since 2009, the economic crisis has resulted in the doubling of Roma

unemployment, affecting mostly Roma women. Unemployment rates for

Roma women are higher than for Roma men in most of the European

countries (Cukrowska & Kocze, 2013) Although, measuring unemployment

among Roma people might be a difficult task with respect to self-perceived

unemployment, which is often much higher than the real unemployment

(UNDP, 2002).

332 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

Main problems related to employment and their impact on Roma

women and girls

Based on an analysis of existing research on Roma and Roma women

employment, the major issues faced by Roma women hindering their

participation in labour market have been identified as lack of education, low

levels of employability skills, low income, and participation in informal work.

Lack of education can be perceived as one of the main problems

related to employment but also as the key source of the problem with

disproportionate unemployment rates among Roma women and whole Roma

population (O’Higgins, 2010, p. 164). Roma women are more likely to have a

lower level of education than Roma men due to their involvement in childcare

and other household activities. Therefore, due to traditional gender roles

among Roma people, their future job prospects might be rather limited

comparing to Roma men (UNDP, 2006). Lack of education presents a key

obstacle in future job seeking (O’Higgins, 2010; O’Higgins & Ivanov, 2006)

and number of years of schooling is commonly perceived as an important

determinant of employment for Roma women, as educated women are more

likely to look for employment than are Roma men (O’Higgins, 2010).

Low levels of employability skills closely relate to education and

present one of the major hindrances in Roma women labour market

participation (O’Higgins & Ivanov, 2006; UNDP, 2006; UNDP, 2002). Roma

people often interpret rejection from job interview as discrimination rather

than result of low employability skills. Under the Decade of Roma Inclusion,

several programmes have been launched in participating countries aiming at

improving employability skills of Roma population. Unfortunately, according

to O’Higgins (2010), general mistrust in trainings among Roma population

hinders such attempts.

According to Cukrowska & Kocze (2013), Roma women have

significantly lower wages than non-Roma women and generally lower income

than Roma men; however this trend varies country to country and type of job.

Thus, Roma women contribute to the household income much less than do

men. The gender pay gap is considerably higher among Roma population than

non-Roma population. Besides low levels of education, the gap between male

and female Roma population in employment might be caused by other

activities and responsibilities of Roma women, such as childcare and

household up-keeping (UNDP, 2006). Such activities are substantial part of

traditional status of Roma women. The role of Roma man is to protect his

family and to support his parents, while woman’s role mainly lies in giving

births, childcare and managing external family relations such as

communication with school and official bodies (Magyari-Vincze, 2006, p. 28).

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 333

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

Long-term unemployment might be identified as the most visible

impact of inactivity within the labour market. Generally long-term

unemployment leads to loss of employability skills as well as potential loss of

welfare benefits (ILO, 2014; O’Higgins & Ivanov, 2006), on which a large

proportion of Roma population relies. With low income, the housing and

health conditions of Roma families often deteriorate, presenting even more

obstacles in future job seeking and thus creating a vicious circle. In order to

save money on housing, Roma family might decide to move into a larger

Roma community, which will commonly be segregated. Roma people living

in mixed areas are more likely to find a job than those who live in segregated

areas (UNDP, 2006). Roma women have generally more access to

employment in urban rather than rural areas, particularly because of

prevalence of traditional gender roles in rural areas (UNDP, 2006).

Consequently, people living in rural areas might not have a formal address,

and thus face additional issues when looking for a job.

Regarding limited access to healthcare, the majority of UNDP, 2002

respondents stated that the reason for their poor health is the inability to pay

for medicines and insurance (UNDP, 2002). As a consequence of

unemployment, Roma women might have more limited access to reproductive

healthcare. A long-term consequence of this situation might be to hinder the

reduction of poverty rates, and the combating of HIV/AIDS (Magyari-Vincze,

2006).

As a result of short or long-term unemployment, participation in the

informal sector of economy might increase. Work in the informal sector is

usually equated with very low wages, poor job quality and very low social

protection (ILO, 2014; UNDP, 2006). Generally, Roma people tend to be

more involved in the informal sector than other ethnic and social groups

(UNDP, 2006). According to ILO (2014), women are more vulnerable within

work in the informal sector than men, applying particularly for Roma women.

Increased participation in the informal sector causes asymmetrical

participation in the state social welfare system. Thus Roma people who do not

participate in the official sector of economy do not pay the required social

taxes, which would in future cover their pensions and social benefits (UNDP,

2002). Therefore, Roma people might be active in accepting the benefits but

passive in producing them (UNDP, 2002), and resulting in weak social

protection (UNDP, 2006).

334 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

Czech Republic, Greece and Romania: Roma girls and women, and

their access to employment

Czech Republic

The Czech government has not signed yet the Council of Europe Convention

on violence against women, as “there is a general lack of political will to

promote gender equality beyond issues of work-life balance and domestic

violence” (European Women’s Lobby, 2013, p. 17).

Following

the issues

with

respect to

education

in Czech

Republic,

Roma

women

very often

do not

possess the

necessary

employabil

ity skills. Demand for low skilled workers has been decreasing in Czech

Republic; therefore training Roma women and improving their skills would be

desired.

Some of the Czech media promote stereotyping of Roma minority by

emphasizing their ethnic origin in criminal cases, and not producing any

positive news related to Roma issues. Anti-Roma reporting in several Czech

newspapers and online news, together with usage of anti-Roma catchphrases

in pre-election slogans by some extreme political parties (European

Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2009a), may further undermine

the status of Roma people and hence decrease their chances to participate in

the labour market. Potential prejudices of employers towards Roma candidates

for jobs might be caused and increased by promoting stereotypes of Roma

people on news. According to European Commission against Racism and

Intolerance (2009a), prejudices of employers towards Roma candidates remain

high in Czech Republic and in many cases, Roma people are likely to be

rejected from a job based on their ethnic background. Therefore, anti Roma

reporting on news can have far reaching consequences.

Living in a segregated community has a significant impact on

employment of Roma women due to lack of job opportunities and high levels

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 335

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

of unemployment in such localities. According to European Commission

against Racism and Intolerance (2009a), the unemployment among Roma

population in segregated communities is reaching up to 90 %. Furthermore,

most of the regions with large Roma communities are suffering from low

average wages and low demand for unskilled or low skilled workers.

Therefore, Roma women with lack of education and previous work experience

are further hindered from access to formal employment.

Greece

Since the crisis affected Greece, unemployment among women

rapidly increased from 13.1 % in 2009 to 29 % in August 2012.

As one of

the many

consequenc

es of the

crisis,

several cuts

affecting

education,

healthcare

and

childcare

have had a

major

impact on

women

who are the primary beneficiaries of these essential services (European

Women’s Lobby, 2013). The Integrated Action Plan has been adopted aiming

at improving the situation in the sphere of education, employment, health and

housing.

The source of income for a majority of the Greek Roma population is

garbage collection and very few are in formal employment (European

Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2009b). Due to high

unemployment and very low incomes of Roma families, many Roma people

live in poverty in Greece which affects their access not only to employment

but also to education and health care.

Similarly as in the other cases, due to low levels of education Roma

women lack necessary qualifications and expertise to participate actively in

the formal labour market in Greece.

336 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

Romania

During the communist era, Roma people were not able to practice their

traditional crafts and were mostly employed in rural areas (Magyari-Vincze,

2006; Ringold et al, 2005).

Since 1990, the

unemployment

rate of the Roma

population in

Romania has

grown. Also,

after the

collapse of

communism, the

general anti-

Roma attitude in

Romania has

strengthened.

Emphasis on

restoring

traditional roles

in Romanian

society promoted by ecclesiastical institutions as well as conservative political

parties applies successfully in rural areas of the country (Oprica, 2008). Thus

Roma women with their strong traditional inclinations might also be

influenced externally in turning their occupation preference into staying at

home with children. According to Magyari-Vincze (2006), Roma girls in

Romania do not usually graduate high school and leave education aged 13-15.

In some Roma communities they are ready to get married at this age. By early

marriages and interrupted education they are not developing and increasing

their employability skills, thus consequently reducing their chances to

participate in labour market and find permanent job.

The Romanian government has not presented many improvements that

would guarantee the integration of the Roma population in the labour market

(European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2006). Since 2002,

the unemployment rate has risen, but Romania still belongs to the countries

with rather lower levels of Roma unemployment compared to Greece and

Czech Republic. According to Women’s Watch report, there are no positive

developments towards women empowerment in Romania during the

researched period of 2009-2012. Unfortunately, since 2010, rather negative

developments are observable, such as the abolition of the National Agency for

Equal Opportunities for Women and Men by the government and also the

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 337

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

closure of the National Agency for Family Protection (European Women’s

Lobby, 2013).

IV. ROMA WOMEN AND ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE AND

HOUSING

1. Main problems related to health and their impact on Roma

women and girls

An analysis of the available literature on the health issue of Roma in

Europe (Foldes & Covaci, 2012) confirms that, clearly, Roma people suffer

from poorer health and unhealthier living conditions compared to the majority

populations in their home countries. Still, there is a need for better data in

order to explain the Roma health gap and design better interventions to reduce

it. However, such data does not seem to be easily available. For example, in

the Czech Republic and Slovakia since 1989, researchers have largely turned

away from health research on particular ethnic groups.

Available data show that Roma women in Europe report chronic

illnesses more frequently than Roma men, but the same pattern is true for non-

Roma and in fact the difference between women and men is double in the non-

Roma case (Cukrowska & Kocze, 2013). Interestingly, reproductive health

does not seem to be as much of a major issue as often assumed, In actuality,

younger Roma women (aged 15-24) have higher rates of visiting a

gynaecologist than non-Roma women, a trend that is reversed for the older

generations and might be indicative of an improvement in health awareness

among Roma. The same is true about the conditions of giving birth. Rates of

childbirths attended by professionals tend to be very high for Roma women in

most European countries, although in some countries, they are still extremely

low (Cukrowska & Kocze, 2013, p.53). Overall, it seems that Roma health

issues are directly connected to educational and economic issues. Lack of

education can create a lack of awareness of health issues, which in turn can

create an unwillingness to see a doctor. Even if awareness is present, however,

the lack of financial resources and thus affordability of healthcare services is

by far the main reason for not seeing a doctor when it is needed (Corsi et al.,

2008, p.46).

338 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

2. Main problems related to housing and their impact on Roma

women and girls

Housing might be one of the most critical issues for the Roma of

Europe and one of the most critical factors underpinning their exclusion from

“mainstream” society. Everywhere across Europe, Roma continue to be one of

the minorities most affected by inadequate housing conditions.

In many European countries, the authorities have failed to provide a

social housing programme for the Roma, as has been done for other social

groups, or are implementing it with limited results so far. The former is true

for the Czech Republic (European Commission against Racism and

Intolerance, 2008) and the latter for Greece (European Commission against

Racism and Intolerance, 2009b). In addition, Roma are often evicted from

even the poor housing they do have available, without authorities observing

the common legal procedure, as is the case in Greece and Romania (European

Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2006; Petrova & Cahn, 2001).

The negative impact of insecure and overcrowded housing on Roma is

stronger for those who inhabit the worst possible housing options; ruined

houses or slums, as the poor living conditions can affect the occurrence of

chronic illnesses and their general health condition. In general, there is an

expected disproportional presence of health problems among the Roma

compared to non-Roma, such as the incidence of airways and lung diseases

related to dampness or the effects of overcrowding on mental health, which

are more likely to occur in substandard housing conditions. On one hand, men

seem to suffer more in terms of their health than women, but on the other

hand, women, because of the traditional gender roles that are often present in

Roma families, remain at home for longer periods and are thus more exposed

to the health risks of the substandard housing conditions, a fact that might

mean that Roma women might be more affected by asthma and certain lung

diseases than Roma men in most cases (Cukrowska & Kocze, 2013).

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 339

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

Czech Republic, Greece and Romania: Roma girls and women, and

their access to healthcare and housing

Czech Republic

Between 1972 and

1991, the Czechoslovak and

then the Czech government

supported and encouraged

sterilisations of Roma

women, a policy aimed at

reducing the Roma

population. The majority of

such sterilisations had been

undertaken without the

women’s knowledge and

permission. In 2004, an

investigation was opened

based on Roma women’s

complaints. During the

investigation several legal

loops were found with consent process Roma women being forced to sign the

agreement to undergo sterilisation. Nevertheless, no woman has yet received a

formal apology or compensation. Proposal for compensations (Approximately

200,000 CZK – around 7,300 Euro per case) should be introduced soon

(European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2009a; European

Roma Rights Centre, 2013).

According to EC/UNDP/WB 2011 survey, very small fraction of the

Roma population resides in their own property. Segregation from non-Roma

communities is still a major issue. Almost one quarter of the total Roma

population lives in very poor conditions such as ruined houses or slums,

resulting in frequent sanitation issues, and half is under a serious threat of

eviction (European Roma Rights Centre, 2013). Children of many evicted

families are being taken into institutional care if the family “does not have

roof over their head” (European Commission against Racism and Intolerance,

2009a). Even if a more lenient eviction policy was enforced, that would not

resolve things as the living conditions in these slums are a major health

hazard. Some kind of social housing policy is needed to provide a long term

solution for this forced moving issue.

340 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

Greece

Most Roma who live

in settlements continue to

earn their income from scrap

and garbage collection,

which poses a major threat to

their health. Poor housing

conditions also aggravate the

situation, although Socio-

Medical Centres, providing

basic health care services

such as primary health care

and vaccination in Roma

settlements have been

created. Greek Roma have

higher rates of disease and ill health, higher rates of child mortality and lower

life expectation than non-Roma. These health issues are connected to the

socioeconomic and educational profile of the Greek Roma, as well as to

discrimination against them by healthcare providers (Ministry of Labour and

Social Security, 2011, p.14).

The Roma population is scattered all over Greece, with the greatest

concentration found in the areas in or around major urban centres, as well as in

rural regions that present the most employment opportunities. Contrary to the

popular myth that Roma are nomadic (ENAR-ERIO, 2011), recent surveys

tend to show that Greek Roma have lived in more or less the same places in

the past 15 or 20 years, so the vast majority of them are settled with regards to

their living situation. On the other hand, Greek Roma usually live in specific

areas, neighbourhoods, suburbs, villages or communities, mostly in isolation

from non-Roma, a fact that may be reinforcing their social exclusion (Ziomas,

Bouzas & Spyropoulou, 2011, p.6). Housing seems to be the fundamental

problem, as roughly half or more than half of the Greek Roma population lives

in makeshift accommodation without basic forms of infrastructure. The

housing issue is also a main obstacle in any effort towards social inclusion and

improvement in the standard of living. Some social housing policy is urgently

needed.

In the last few years, despite the Decade of Roma Inclusion initiative

running since 2005, there is no official policy framework or any governance

arrangements for addressing Roma poverty and social exclusion in Greece

(Ziomas, Bouzas & Spyropoulou, 2011). On the other hand, some

programmes and initiatives are under way. Housing loans allowing Roma

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 341

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

families to purchase their own houses or apartments are available at extremely

low interest rates and extremely beneficial conditions as was the case for the

Greeks of the former USSR who emigrated in the 1990s. Unlike that case,

however, the participation of the Roma themselves in the scheme has been

limited, with outreach proving insufficient (Ziomas, Bouzas & Spyropoulou,

2011). The Greek National Reform Programme 2011-2014, is processing a

medium and long term strategy for the social inclusion of Roma, the

Operational Programme Human Resources Development 2007-2013 includes

many actions for vulnerable social groups including the Roma, and various

separate independent projects are under way, including the “Progress” EU

project, targeted specifically on Roma women and gender mainstreaming in

Greek municipalities (Skoulas et al., 2012). Perhaps the challenge lies in

promoting these actions and initiatives and encouraging participation of the

Roma in them.

Romania

More than half of the

Roma population in

Romania suffers from

obesity and dental

issues. Majority of

children do not have the

compulsory

immunizations, which

might result in further

health problems and an

increase of child

mortality. Furthermore,

absence of identity

documents usually

limits access to

healthcare. Since 1996 in Romania, the Health mediation programme, with its

focus on health has played a significant role in the empowerment of Roma

women. The programme aims to improve access to health care for Roma

women, provide health education, child vaccination and many other

improvements (Roma Health Mediation in Romania, 2013).

According to the European Commission against Racism and

Intolerance Report, some members of the Roma minority continue to live in

unhealthy housing, often as a result of discriminatory measures by local

342 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

authorities. Furthermore, Roma are sometimes unlawfully evicted from their

housing, even in the middle of winter and in the presence of the media,

without the observation of legal procedures (European Commission against

Racism and Intolerance, 2006, p.37). Also, Roma continue to live in

segregated communities, which has a major impact on access to better schools

and mobility for employment.

CONCLUSIONS

Although positive steps have been taken in all three countries to

improve the situation of women in general and of Roma in particular, in

practice, Roma girls and women still face discrimination with respect to equal

access to education, employment, health care and housing. Every

improvement is significant, but the main issues faced by Roma women still

remain unresolved. Roma girls spend fewer years in schools than Roma boys

due to the fact that they are expected to take up the role of care givers and

even to enter early marriages from the age of 11 and they display high dropout

rates. Low levels of education and early marriages hinder access to

employment for Roma women and girls due to deficiency of necessary skills

and qualifications. Furthermore, living in a segregated community presents an

additional challenge considering extreme unemployment and often poor

housing conditions in such areas. Roma girls might be more exposed to

traditional roles while living in segregated communities and due to the lack of

education and contact with other cultures, they might be forced to enter

marriage and start family life at a very young age. Doing so, Roma girls might

be entering a vicious circle of reliance on welfare benefits, inability to

participate in the labour market and hence incompetence to pay taxes.

Moreover, there seems to be no prospect of these issues being

resolved in the near future. Even recent legislation and policies are most often

designed in a top-down approach, with little or no consultation and direct

involvement of the Roma community. Roma culture is sometimes considered

to be responsible for the failure of the programmes and policies implemented,

ignoring the fact that it is often a reaction to a hostile society and to the lack of

trust in the system and in the majority population, or at least to poorly

designed policies that claim to be helping the Roma without taking their

specific needs and conditions into account. In practical terms, this results in a

waste of resources and effort with little effect on the quality of life of the

target population.

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 343

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

What is needed to produce a real impact is a different approach: a

bottom-up initiative taking place within Roma communities, both

geographically and organisationally, so that two common drawbacks of the

existing approaches, information not reaching the beneficiaries and lack of

active Roma involvement, can be surpassed. In addition, for this initiative to

prove more successful than the previous ones, a number of prerequisites are

necessary, such as proper information about the status and needs of the

beneficiaries, which must be collected as part of preliminary research, and also

political will and continuous and stable funding. If these requirements are met

then an innovative, active, bottom-up project has a fair chance of succeeding

where previous initiatives have failed and making an actual difference for one

of the most discriminated-against groups in Europe.

344 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

Biblography

Al Ramiah, A., Hewstone, M., Dovidio, J. & Penner, L. (2010). “The social

psychology of discrimination: Theory, measurement and consequences”,

in F. McGinnity (ed.), Making equality count: Irish and international

approaches to measuring discrimination (pp. 84-112). Dublin: Liffey

Press

Beynon, J. (2002). Masculinities and culture. Philadelphia: Open University

Press

Corsi, M., Crepaldi, C., Samek Lodovici, M., Boccagni, P. & Vasilescu, C.

(2008). Synthesis Report: Ethnic minority and Roma women in Europe:

A case for gender equality? Luxembourg: Publications Office of the

European Union

Council of Europe (2014). Council of Europe Gender Equality Strategy 2014-

2017. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publications Office

Cukrowska, E. & Kóczé, A. (2013). Interplay between gender and ethnicity:

Exposing Structural Disparities of Roma women. Analysis of the

UNDP/World Bank/EC regional Roma survey data. Bratislava: UNDP,

Europe and the CIS Bratislava Regional Centre

ENAR-ERIO (2011). Debunking myths and revealing truths about the Roma.

Brussels: European Network Against Racism & European Roma

Information Office

European Commission (2007). Tackling Multiple Discrimination: Practices,

policies and laws, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs

and Equal Opportunities, Luxembourg

European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (2006). Third report on

Romania. ECRI Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and

Legal Affairs, Council of Europe

European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (2009a). ECRI Report

on the Czech Republic (fourth monitoring cycle). ECRI Secretariat,

Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs, Council of

Europe

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 345

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (2009b). ECRI Report

on Greece (fourth monitoring cycle). ECRI Secretariat, Directorate

General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs, Council of Europe

European Court of Human Rights (2007). D.H. and others v. the Czech

Republic [online], available at:

http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/sites/eng/pages/search.aspx?i=001-

83256#{"itemid":["001-83256"]}

European Court of Human Rights (2008). Sampanis and Others v. Greece

[online], available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/sites/eng-

press/pages/search.aspx?i=003-2378798-2552166#{"itemid":["003-

2378798-2552166"]}

European Roma Information Office (2013). The Charter of Fundamental

Rights of the European Union and the Roma

European Roma Rights Centre (2013). Written comments of the European

Roma Rights Centre Concerning the Czech Republic, European Roma

Rights Centre

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2009). EU-MIDIS Data in

Focus Report: The Roma

European Women’s Lobby (2013). Women’s Watch 2012-2013, European

Women’s Lobby, Brussels

Földes, M. E., & Covaci, A. (2012). Research on Roma health and access to

healthcare: state of the art and future challenges. International journal of

public health, 57(1), 37-39

Fundacion Secretariado Gitano and Efxini Poli (2009). Health and the Roma

Community: Analysis of the situation in Greece (in Greek). Athens:

Author

International Labour Organization (2012). Global employment trends for

women, International Labour Organization, Geneva

346 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

International Labour Organization (2014). Global employment trends 2014:

Risk of a jobless recovery? International Labour Organization, Geneva

Kabeer, N. (2005). “Gender equality and women's empowerment: A critical

analysis of the third millennium development goal 1”. Gender &

Development, 13:1, 13-24

Koupilová, I., Epstein, H., Holčı́k, J., Hajioff, S., & McKee, M. (2001).

“Health needs of the Roma population in the Czech and Slovak

Republics”. Social science & medicine, 53(9), 1191-1204

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). “Conceptualizing stigma”. Annual review

of Sociology, 363-385

Magyari-Vincze, E. (2006). “Social exclusion at the crossroads of gender,

ethnicity and class, A view of Roma women’s reproductive health”. CPS

International Fellowship Program, Open Society Institute, Budapest

Ministry of Labour and Social Security (2011). National strategic framework

for Roma. Athens: Ministry of Labour and Social Security

O’Higgins, N. (2010). “It’s not that I’m a racist, it’s that they are Roma. Roma

discrimination and returns to education in South Eastern Europe”.

International Journal of Manpower, 31: 2, 163-187

O’Higgins, N. and Ivanov, A. (2006). “Education and employment

opportunities for the Roma”. Comparative Economic Studies, 48, 6-19

Oprea, Alexandra (2005). “The Arranged Marriage of Ana Maria Cioaba,

Intra-Community Oppression and Roma Feminist Ideals Transcending

the ‘Primitive Culture’ Argument”. European Journal of Women’s

Studies, 1350-5068 Vol. 12(2): 133–148

Oprica, V. (2008). “Gender Equality and Conflicting Attitudes Toward Women

in Post-Communist Romania”. Human Rights Review, 9:29–40

Petrova, D. & Cahn, C. (2001). Focus: Roma in Greece. Budapest: European

Roma Rights Centre

Phenjalipe (2014). Strategy on the Advancement of Roma Women and Girls

(2014-2020), Third draft

Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351 347

Roxana ANDREI, George MARTINIDIS, Tana TKADLECOVA

Ringold, D. et al (2005). Roma in expanding Europe: Breaking the poverty

cycle. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The

World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Skoulas, M., Theleriti, M., Vougiouka, A. & Vassou, A. (2012). Gender

mainstreaming in Greek Municipalities Focusing on Socially

Disadvantaged Women – Roma Women. Athens: “Progress” EU project

Strategy of the Government of Romania for the inclusion of the Romanian

citizens belonging to Roma minority for the period 2012 – 2020 [online],

available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/justice/discrimination/files/roma_romania_strategy_e

n.pdf

UNICEF (2009). Toward Roma Inclusion: A Review of Roma Education

Initiatives in Central and South-Eastern Europe. Geneva: UNICEF

Regional Office for Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth

of Independent States

UNICEF (2011). The Right of Roma Children to Education: Position Paper.

Geneva: UNICEF Regional Office for Central and Eastern Europe and

the Commonwealth of Independent States

United Nations Development Programme (2002). Avoiding the Dependency

Trap. Bratislava: UNDP

United Nations Development Programme (2006). At Risk:Roma and the

Displaced in Southeast Europe. Bratislava: UNDP, Europe and the CIS

Bratislava Regional Centre

Whitley, B. & Kite, M. (2009). The psychology of prejudice and

discrimination. London: Cengage learning

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2013). Roma health mediation in Romania:

case study. Copenhagen, (Roma Health Case Study Series, No. 1)

Ziomas, D., Bouzas, N. & Spyropoulou, N. (2011). Promoting the social

inclusion of Roma. A study of national policies. Athens: Institute of

Social Policy – National Centre for Social Research (EKKE)

348 Balkan Social Science Review, Vol. 4, December 2014, 323-351

Challenges Faced by Roma Women in Europe on Education, Employment…

APPENDIX

SUMMARIES OF INTERVIEWS WITH ROMA WOMEN1

Participant 1 – Lia Gaudi, Roma woman from Romania

Lia is a very well educated lady from Romania with a vast experience

of working with Roma people. We can say that she represents a prototype of

very strong Roma woman and could be an example for many other women. As

a Roma woman, she has not experienced many difficulties at school but

admits that Roma children usually have to usually work harder than others.

Her parents were supportive in her educational and life choices. In her

opinion, the main challenges for Roma girls are traditions to some extent,

stereotypes and rejection by the society. She also appreciates the affirmative

measures in Romania, helping Roma students to have access to education.

However, Lia admits that her case is a happy one, that there are many

negative examples of Roma students fighting much more that many of the

majority for their place in the academic environment.

To empower Roma women, Lia suggests following bottom up

approach and direct work with Roma women and listening to their needs.

With regards to health, there are observable issues particularly lack of health

insurance, but our participant has not experienced any problems.