Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SUDA Entry Epsilon 2405:: (Epicurus, Epikouros)

SUDA Entry Epsilon 2405:: (Epicurus, Epikouros)

Uploaded by

Fernando Garcia GarciaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Riddle 1Document7 pagesRiddle 1Jeck Oro100% (3)

- Duvet: Arranged by RurouniDocument5 pagesDuvet: Arranged by RurouniNNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Nelson Mandela Early YearsDocument3 pagesNelson Mandela Early YearsnitaNo ratings yet

- Đề cương môn NNHXHDocument4 pagesĐề cương môn NNHXH207220201084No ratings yet

- Manuscripts of Ottoman-Safavid RelationsDocument18 pagesManuscripts of Ottoman-Safavid RelationsfauzanrasipNo ratings yet

- Malone - 1926 - Agelmund and LamichoDocument29 pagesMalone - 1926 - Agelmund and LamichocarlazNo ratings yet

- Keynotes HamletDocument9 pagesKeynotes Hamletjesusangelsanchez87100% (1)

- Rachel Green, The Real Protagonist of FriendsDocument9 pagesRachel Green, The Real Protagonist of Friendskrmce pNo ratings yet

- Investigationofa19pres BWDocument800 pagesInvestigationofa19pres BWAnElysianNo ratings yet

- Impact of Christian Missionaries and English Language On Tribal Languages and Culture of Jharkhand With Special Reference To OraonsDocument2 pagesImpact of Christian Missionaries and English Language On Tribal Languages and Culture of Jharkhand With Special Reference To OraonsShayantani Banerjee PrabalNo ratings yet

- Paterno Brothers PDFDocument1 pagePaterno Brothers PDFsara sibumaNo ratings yet

- Ali Baba and The Forty ThievesDocument1 pageAli Baba and The Forty ThievesjNo ratings yet

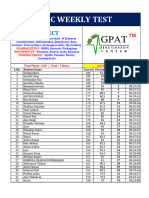

- Result Weekly Test 07.04.2024Document29 pagesResult Weekly Test 07.04.2024Swathi GNo ratings yet

- Marcel Mauss, A Category of The Human Mind: The Notion of Person The Notion of SelfDocument13 pagesMarcel Mauss, A Category of The Human Mind: The Notion of Person The Notion of Selflupocos100% (2)

- Latihan SoalDocument3 pagesLatihan SoalSasusakuNo ratings yet

- Listado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Listado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Iv Nivel I NivelDocument4 pagesListado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Listado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Iv Nivel I Nivellaura caroNo ratings yet

- 91 (SubtitleTools - Com) Friends - (3x09) - The One With The Football + Audio CommentaryDocument33 pages91 (SubtitleTools - Com) Friends - (3x09) - The One With The Football + Audio CommentaryaliNo ratings yet

- In The Heights DramaturgyDocument66 pagesIn The Heights DramaturgyJessica López-BarklNo ratings yet

- Units 5-6 Workshop B1Document6 pagesUnits 5-6 Workshop B1est.dpescadorNo ratings yet

- Mae Tha Raw Hta AgreementDocument3 pagesMae Tha Raw Hta Agreementmandalayspring0% (1)

- The Announcement of The 3 1st Recruitment of The Point System in Nepal ManufacturingDocument1,217 pagesThe Announcement of The 3 1st Recruitment of The Point System in Nepal ManufacturingarsukambangNo ratings yet

- Imam Ar-Ridha', A Historical and Biographical Research (8th Imam)Document147 pagesImam Ar-Ridha', A Historical and Biographical Research (8th Imam)Shahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- MS Qualified Students ListDocument68 pagesMS Qualified Students ListRabia RasheedNo ratings yet

- Cynicalex Master GuidesDocument42 pagesCynicalex Master GuidesJulia SatrianiNo ratings yet

- Soc NorDocument4 pagesSoc NorCIRO RAMOSNo ratings yet

- 637916Document20 pages637916Anonymous n8Y9NkNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter SpellsDocument68 pagesHarry Potter SpellsKohinoor B.100% (1)

- Calendar 2388 - 30 Day MonthsDocument3 pagesCalendar 2388 - 30 Day MonthsTheodore James TurnerNo ratings yet

- The Iranian World From The Timurids To The Safavids (1370 - 1722)Document16 pagesThe Iranian World From The Timurids To The Safavids (1370 - 1722)insightsxNo ratings yet

SUDA Entry Epsilon 2405:: (Epicurus, Epikouros)

SUDA Entry Epsilon 2405:: (Epicurus, Epikouros)

Uploaded by

Fernando Garcia GarciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SUDA Entry Epsilon 2405:: (Epicurus, Epikouros)

SUDA Entry Epsilon 2405:: (Epicurus, Epikouros)

Uploaded by

Fernando Garcia GarciaCopyright:

Available Formats

SUDA entry epsilon 2405:

̓Επίκουρος (Epicurus, Epikouros)

This man assigned no importance to religion;[1] but there were three brothers [sc. of his],[2] who died

in the most pitiful way, struck down by countless diseases.[3] As for Epicurus, although still young, he

was not able to easily descend from his bed by himself, but he was short-sighted and fearful of facing

the sunlight, for he disliked the most brilliant and shining of the gods. And indeed he turned his eyes

away even from the light of fire, and from his lower orifices blood used to drip down, and such was

the consumption of his body that he was not even able to carry the weight of his own clothes.[4] And

Metrodorus[5] and Polyaenus[6], both of them his companions, died in the worst way men can die,

and indeed they took for their impiety a requital that nobody might ever blame. So easily overcome by

pleasure was Epicurus that in his last moments he wrote in his will a disposition that a sacrifice be offered

once a year to his father, his mother and his brothers, and to the previously mentioned Metrodorus and

Polyaenus, but twice a year to himself;[7] so that even in this the sage honored the higher degree of

profligacy. And he had some tables of stone built, and gave orders that these be put in his tomb, this

greedy and gluttonous man. He devised these things not because he was rich, but because his appetites

had driven him mad, as if those things should die along with him. They banished the Epicureans from

Rome by a public senatorial decree.[8] And also the Messenians, the ones who live in Arcadia, expelled

those reputed to be members of this, let us say, "manger", saying that they were corrupters of the youth

and attaching to their doctrine the stain of infamy because of their effeminacy and impiety; and they gave

orders that, before sunset, the Epicureans be out of the borders of Messenia and that after they had left,

the priests purify the temples and the timouchoi (this is the name Messenians give to their magistrates)

purify the whole city, as delivered from some filthy contaminations and offscourings. [Note] that in Crete

the citizens of Lyktos[9] chased away some Epicureans who had come there. And a law was written

in the local language, stating that whoever thought of adhering to this effeminate and ignominious and

hideous doctrine were enemies of the gods and should be banished from Lyktos; but if anybody dared to

come and neglect the orders of the law, he should be bound in a pillory near the office of the magistrates

for twenty days, naked and with his body spread with honey and milk, so that he would be a meal for

bees and flies and the insects would in the stated time kill them. After this time, if he were still alive, he

should be thrown from a cliff, dressed in women's clothes.

Notes

For Epicurus see already epsilon 2404 (and again epsilon 2406). The present entry is Aelian fr. 42a

Domingo-Forasté (39 Hercher), from On Divine Manifestations; cf. epsilon 715, eta 630, kappa 2800,

omicron 773, pi 2870, sigma 1637, tau 510, phi 132.

Following a scheme familiar in Christian writers (e.g. Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum), Aelian shows

in this work the effects of divine punishment -- essentially, in terms of physical ailments -- on individuals

guilty of being an "enemy of the gods"; this means, in the surviving fragments, people held to adhere to the

Epicurean school. The attitude towards Epicurean doctrine that Aelian displays is based on the common

perception of Epicureans as atheists and effeminates -- one stemming from the misunderstanding of

the ethical aspect of Epicureanism, determining pleasure as the highest goal (see Epicurus, Epistula ad

Meneceum 132 for the definition of pleasure). Like Plutarch and especially Athenaeus, Aelian essentially

sees the Epicurean notion of pleasure as over-indulgence in food, and effeminacy.

[1] On Epicurus' indifference to popular religion see also Aelian fr. 64a D-F, 61 Hercher (also from On

Divine Manifestation).

[2] Neokles, Chairedemos and Aristoboulos: see under epsilon 2040.

[3] Neither the diseases which killed Epicurus' brothers nor the physical ailments that afflicted the

philosopher himself are attested elsewhere.

[4] The cause of Epicurus' death (in 270 BCE) was a urinary blockage and associated dysentery.

[5] Metrodorus of Lampsacus (c.331-278), a disciple and close friend of Epicurus, described as a "second

Epicurus" by Cicero (De Finibus 2.28.92). After Metrodorus' death, Epicurus took care of his family and

recommended his children to be cared for in his last will. Only fragments of his work survive.

[6] Polyaenus of Lampsacus (?340-278), a mathematician, whose friendship with Epicurus started when

the philosopher opened a school in Lampsacus in 307-306. Both Polyaenus and Metrodorus, together with

Hermarchus, had the rank of kathegemones, "secondary leaders", in the hierarchically-based Epicurean

school.

[7] Epicurus' birthday was celebrated each year; the twentieth day of each month was celebrated in honor

of Metrodorus. On the flattering attitude of the members of the school towards Epicurus cf. Plutarch,

Against Colotes 1117AB.

[8] The reference is to the expulsion of the Epicureans Alcaeus and Philiscus in 154 BCE as a result of their

ethical teaching.

[9] An ancient city in Crete, a former Lacedaemonian colony mentioned by Homer and Hesiod as

participating to the Trojan War. See Stephanus of Byzantium s.v., and lambda 831.

Keywords: biography; Christianity; clothing; constitution; ethics; food; geography; law;

medicine; philosophy; religion; zoology

Translated by Antonella Ippolito; edited by Catharine Roth and David Whitehead.

This is the version of the Suda On Line entry created 9 September 2017; the current

version, at http://www.cs.uky.edu/~raphael/sol/sol-entries/epsilon/2405,

may be different.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Riddle 1Document7 pagesRiddle 1Jeck Oro100% (3)

- Duvet: Arranged by RurouniDocument5 pagesDuvet: Arranged by RurouniNNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Nelson Mandela Early YearsDocument3 pagesNelson Mandela Early YearsnitaNo ratings yet

- Đề cương môn NNHXHDocument4 pagesĐề cương môn NNHXH207220201084No ratings yet

- Manuscripts of Ottoman-Safavid RelationsDocument18 pagesManuscripts of Ottoman-Safavid RelationsfauzanrasipNo ratings yet

- Malone - 1926 - Agelmund and LamichoDocument29 pagesMalone - 1926 - Agelmund and LamichocarlazNo ratings yet

- Keynotes HamletDocument9 pagesKeynotes Hamletjesusangelsanchez87100% (1)

- Rachel Green, The Real Protagonist of FriendsDocument9 pagesRachel Green, The Real Protagonist of Friendskrmce pNo ratings yet

- Investigationofa19pres BWDocument800 pagesInvestigationofa19pres BWAnElysianNo ratings yet

- Impact of Christian Missionaries and English Language On Tribal Languages and Culture of Jharkhand With Special Reference To OraonsDocument2 pagesImpact of Christian Missionaries and English Language On Tribal Languages and Culture of Jharkhand With Special Reference To OraonsShayantani Banerjee PrabalNo ratings yet

- Paterno Brothers PDFDocument1 pagePaterno Brothers PDFsara sibumaNo ratings yet

- Ali Baba and The Forty ThievesDocument1 pageAli Baba and The Forty ThievesjNo ratings yet

- Result Weekly Test 07.04.2024Document29 pagesResult Weekly Test 07.04.2024Swathi GNo ratings yet

- Marcel Mauss, A Category of The Human Mind: The Notion of Person The Notion of SelfDocument13 pagesMarcel Mauss, A Category of The Human Mind: The Notion of Person The Notion of Selflupocos100% (2)

- Latihan SoalDocument3 pagesLatihan SoalSasusakuNo ratings yet

- Listado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Listado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Iv Nivel I NivelDocument4 pagesListado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Listado de Estudiantes Programa de Medicina Iv Nivel I Nivellaura caroNo ratings yet

- 91 (SubtitleTools - Com) Friends - (3x09) - The One With The Football + Audio CommentaryDocument33 pages91 (SubtitleTools - Com) Friends - (3x09) - The One With The Football + Audio CommentaryaliNo ratings yet

- In The Heights DramaturgyDocument66 pagesIn The Heights DramaturgyJessica López-BarklNo ratings yet

- Units 5-6 Workshop B1Document6 pagesUnits 5-6 Workshop B1est.dpescadorNo ratings yet

- Mae Tha Raw Hta AgreementDocument3 pagesMae Tha Raw Hta Agreementmandalayspring0% (1)

- The Announcement of The 3 1st Recruitment of The Point System in Nepal ManufacturingDocument1,217 pagesThe Announcement of The 3 1st Recruitment of The Point System in Nepal ManufacturingarsukambangNo ratings yet

- Imam Ar-Ridha', A Historical and Biographical Research (8th Imam)Document147 pagesImam Ar-Ridha', A Historical and Biographical Research (8th Imam)Shahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- MS Qualified Students ListDocument68 pagesMS Qualified Students ListRabia RasheedNo ratings yet

- Cynicalex Master GuidesDocument42 pagesCynicalex Master GuidesJulia SatrianiNo ratings yet

- Soc NorDocument4 pagesSoc NorCIRO RAMOSNo ratings yet

- 637916Document20 pages637916Anonymous n8Y9NkNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter SpellsDocument68 pagesHarry Potter SpellsKohinoor B.100% (1)

- Calendar 2388 - 30 Day MonthsDocument3 pagesCalendar 2388 - 30 Day MonthsTheodore James TurnerNo ratings yet

- The Iranian World From The Timurids To The Safavids (1370 - 1722)Document16 pagesThe Iranian World From The Timurids To The Safavids (1370 - 1722)insightsxNo ratings yet