Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Portrait of The Artist As An Employee The Impact of Personality On Career Satisfaction

A Portrait of The Artist As An Employee The Impact of Personality On Career Satisfaction

Uploaded by

Esther WangCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- D&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveDocument208 pagesD&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveLeonardo Sanchez100% (12)

- DGR LR40 ManualDocument59 pagesDGR LR40 ManualPiratsik Orbotana20% (5)

- Art Appreciation Course OutlineDocument3 pagesArt Appreciation Course OutlineFrance BejosaNo ratings yet

- Abstract Chapter 2 How Languages Are LearnedDocument4 pagesAbstract Chapter 2 How Languages Are LearnedDanielGonzálezZambranoNo ratings yet

- PS1 SolutionDocument8 pagesPS1 SolutionColin Jennings100% (1)

- Warehouse Management System in SAPDocument10 pagesWarehouse Management System in SAPWaaKaaWNo ratings yet

- Using BAPI To Migrate Material Master - BAPI's in SAP - SAPNutsDocument10 pagesUsing BAPI To Migrate Material Master - BAPI's in SAP - SAPNutsAshish MohapatraNo ratings yet

- Work CV - Jen YuDocument2 pagesWork CV - Jen Yuapi-455091043No ratings yet

- Musical MashDocument6 pagesMusical MashSuccsurraNo ratings yet

- Hall - 2010 - Making Art, Teaching Art, Learning Art ExploringDocument8 pagesHall - 2010 - Making Art, Teaching Art, Learning Art ExploringAlexandra NavarroNo ratings yet

- Yinka GraphicWorkDocument6 pagesYinka GraphicWorkYinka DanmoleNo ratings yet

- Rivera 2012 Hiring As Cultural MatchingDocument24 pagesRivera 2012 Hiring As Cultural Matchingjannah.sherif06No ratings yet

- Syllabus-OBE - Ge 6 Art Appreciation BUSINESS ADMINISTRATIONDocument11 pagesSyllabus-OBE - Ge 6 Art Appreciation BUSINESS ADMINISTRATIONVanessa L. VinluanNo ratings yet

- Arts Education Policy ReviewDocument14 pagesArts Education Policy Reviewdiajeng lissaNo ratings yet

- Ego Boundaries and Self-Esteem: Two Elusive Facets of The Psyche of Performing MusiciansDocument19 pagesEgo Boundaries and Self-Esteem: Two Elusive Facets of The Psyche of Performing Musiciansparisa baseremaneshNo ratings yet

- Brand Guide: Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & CommunicationsDocument50 pagesBrand Guide: Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & CommunicationskimillerNo ratings yet

- Horticulturist 122.fullDocument5 pagesHorticulturist 122.fullbillNo ratings yet

- The Stanford Daily: Class of 11 Starts Job HuntDocument8 pagesThe Stanford Daily: Class of 11 Starts Job Hunteic4659No ratings yet

- Assessing Professional Attributesusing Conjoint AnalysisDocument20 pagesAssessing Professional Attributesusing Conjoint AnalysisivNo ratings yet

- Perdev MELC Learning GuideDocument8 pagesPerdev MELC Learning GuideJonel Joshua RosalesNo ratings yet

- Crafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraDocument25 pagesCrafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraCastañeda ValeriaNo ratings yet

- Class-ART APPRECIATION PresentationDocument11 pagesClass-ART APPRECIATION PresentationCharmaine JanorasNo ratings yet

- A Career Guide For Studio Art Majors: SkillsDocument9 pagesA Career Guide For Studio Art Majors: SkillsNenkent AndersonNo ratings yet

- Improvisation in Service PerformancesDocument22 pagesImprovisation in Service PerformancesTam NguyenNo ratings yet

- Domainbsusan Orr Article Issue 10 PP 9 13Document5 pagesDomainbsusan Orr Article Issue 10 PP 9 13api-279812605No ratings yet

- Jordan, Noel - How New Is New MediaDocument11 pagesJordan, Noel - How New Is New MediaSandra SankatNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Assessment ProjectDocument7 pagesRenaissance Assessment Projectapi-707110713No ratings yet

- An Evidence-Based Roadmap For Success: Part 1-The Bumpy Road of Graduate SchoolDocument15 pagesAn Evidence-Based Roadmap For Success: Part 1-The Bumpy Road of Graduate SchoolMothi GhimireNo ratings yet

- Jackie Otero - Music Resume For WebDocument1 pageJackie Otero - Music Resume For WebJackie OteroNo ratings yet

- Developing HR Strategy: May 2010 Issue 32Document24 pagesDeveloping HR Strategy: May 2010 Issue 32Augustin IordacheNo ratings yet

- Impact of The Perceived Image of Celebrity Endorsers On Tourists' Intentions To VisitDocument14 pagesImpact of The Perceived Image of Celebrity Endorsers On Tourists' Intentions To VisitCyprien DelaporteNo ratings yet

- Senior Residents Views On The Meaning Of.19Document4 pagesSenior Residents Views On The Meaning Of.19N N100% (1)

- Brochure IntroDocument1 pageBrochure IntroShahed FacebookNo ratings yet

- Aom-Dll 17-21 Week 3Document4 pagesAom-Dll 17-21 Week 3frances_peña_7No ratings yet

- Art App Module BSFDocument19 pagesArt App Module BSFJumreih CacalNo ratings yet

- Downs and Windchief 2015 Vol27 Issue 2Document8 pagesDowns and Windchief 2015 Vol27 Issue 2Alan DvořákNo ratings yet

- Musical and Social Communication in Expert Orchestral PerformanceDocument19 pagesMusical and Social Communication in Expert Orchestral PerformanceAna HespanhaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Art and The ArtistDocument4 pagesThe Role of Art and The ArtistNahla LeilaNo ratings yet

- Thang Đo OCBDocument8 pagesThang Đo OCBMai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Who Goes FreelanceThe Determinants of Self-Employment For ArtistsDocument22 pagesWho Goes FreelanceThe Determinants of Self-Employment For ArtistsJeffJeffNo ratings yet

- The Role of Art and The Artist Edgar H. ScheinDocument3 pagesThe Role of Art and The Artist Edgar H. ScheinBetsey Merkel100% (1)

- Art and MusicDocument2 pagesArt and MusicflaviohoboNo ratings yet

- White BELTINGAcademicDiscipline 2011Document4 pagesWhite BELTINGAcademicDiscipline 2011MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- HRM Chapter 10Document28 pagesHRM Chapter 10Shahadat Hossain TipuNo ratings yet

- Crafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraDocument25 pagesCrafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraOrnela RigottiNo ratings yet

- Area Appreciation 1Document25 pagesArea Appreciation 112Jagtap HritikaNo ratings yet

- Cres AssignmentDocument5 pagesCres AssignmentFahad LumambasNo ratings yet

- Box 3.15 Focus On Student Research: Developing A Thematic Analysis GridDocument2 pagesBox 3.15 Focus On Student Research: Developing A Thematic Analysis GridMuhammad MoazNo ratings yet

- Knowledge 2Document16 pagesKnowledge 2Jake Arman PrincipeNo ratings yet

- PuchainaDocument21 pagesPuchainaAlfonso RomeroNo ratings yet

- 潘玥 EAED定校+专业 2Document1 page潘玥 EAED定校+专业 2panyue99999No ratings yet

- Speech Pathologists' Professional Identity in Response To Working With AssistantsDocument1 pageSpeech Pathologists' Professional Identity in Response To Working With AssistantsKaren DanielaNo ratings yet

- Cuff WordsImagesAlchemy 1982Document9 pagesCuff WordsImagesAlchemy 1982untilted1212No ratings yet

- Img 0001Document4 pagesImg 0001Zico RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Estudo de Caso - Professor ArtistaDocument51 pagesEstudo de Caso - Professor ArtistaHelena FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Andrew Mayo Added Value From HR MetricsDocument28 pagesAndrew Mayo Added Value From HR MetricsVinita SeshadriNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Grid CCCA3 Stand For Your CauseDocument2 pagesEvaluation Grid CCCA3 Stand For Your CauseMohamed RahalNo ratings yet

- ThinkerDocument1 pageThinkerindhraniNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-692586049No ratings yet

- Megan Meyer: Product Design PortfolioDocument30 pagesMegan Meyer: Product Design PortfoliomeganmeyNo ratings yet

- EGADE Atr Brochure EMBA - GRL - PPDocument9 pagesEGADE Atr Brochure EMBA - GRL - PPGabo S.nNo ratings yet

- Teacher As PerformerDocument20 pagesTeacher As PerformerPedro Braga100% (2)

- DLL Week 6Document4 pagesDLL Week 6maria victoria sagaysay100% (1)

- VLSI QnA - Interview Questions On Blocking and Nonblocking AssignmentsDocument3 pagesVLSI QnA - Interview Questions On Blocking and Nonblocking AssignmentsVIKRAMNo ratings yet

- Constitution and By-Laws of SSCDocument12 pagesConstitution and By-Laws of SSCJaypee Mercado Roaquin100% (1)

- Coca Cola ManagementDocument87 pagesCoca Cola Managementgoswamiphotostat43% (7)

- English: Quarter 1 - Module 7Document26 pagesEnglish: Quarter 1 - Module 7Jhing Loren86% (14)

- The Psychology of Effective CoachingDocument454 pagesThe Psychology of Effective CoachingLuchoNo ratings yet

- Flamenco FormsDocument3 pagesFlamenco FormsNayvi KirkendallNo ratings yet

- MAT 171 Precalculus Algebra Section 9-7 Parametric EquationsDocument10 pagesMAT 171 Precalculus Algebra Section 9-7 Parametric EquationsZazliana IzattiNo ratings yet

- Effect of English Teachers EffectivenessDocument3 pagesEffect of English Teachers EffectivenessMaybelle Tecio PabellanoNo ratings yet

- Hypertension, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians in Ulaanbaatar, MongoliaDocument6 pagesHypertension, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians in Ulaanbaatar, MongoliaUurtsaikh BaatarsurenNo ratings yet

- Development of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingDocument221 pagesDevelopment of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingsekharsamyNo ratings yet

- SYLLABUS Communication ArtsDocument8 pagesSYLLABUS Communication ArtsPhee May DielNo ratings yet

- Sultans of Swing TabDocument5 pagesSultans of Swing TabNadiaNo ratings yet

- De Guzman VDocument100 pagesDe Guzman VRoel PukinNo ratings yet

- Maoism in Bangla PDFDocument15 pagesMaoism in Bangla PDFAyub Khan JrNo ratings yet

- Drugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravisDocument3 pagesDrugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravispapitomalosoNo ratings yet

- SotDL - Scions of The BetrayerDocument28 pagesSotDL - Scions of The BetrayerGabrijel Klarić100% (2)

- Dustin Hoffman Masterclass NotesDocument5 pagesDustin Hoffman Masterclass NotesDorian BasteNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Intro SociologyDocument13 pagesFinal Exam Intro SociologyJoseph CampbellNo ratings yet

- UGCF-Flowchart (4 Yrs Course)Document4 pagesUGCF-Flowchart (4 Yrs Course)cooljishu2020No ratings yet

- Simple Present: Example: I Am HungryDocument4 pagesSimple Present: Example: I Am HungryWarren EllisNo ratings yet

- Sirs & ModsDocument26 pagesSirs & Modsnerlyn silao50% (2)

- (1900) The Game Birds and Wild Fowl of The British IslesDocument594 pages(1900) The Game Birds and Wild Fowl of The British IslesHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (2)

- 11 - NCPsDocument6 pages11 - NCPsellian3leiNo ratings yet

- Lebato-Pr2Document6 pagesLebato-Pr2Sir JrNo ratings yet

A Portrait of The Artist As An Employee The Impact of Personality On Career Satisfaction

A Portrait of The Artist As An Employee The Impact of Personality On Career Satisfaction

Uploaded by

Esther WangOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Portrait of The Artist As An Employee The Impact of Personality On Career Satisfaction

A Portrait of The Artist As An Employee The Impact of Personality On Career Satisfaction

Uploaded by

Esther WangCopyright:

Available Formats

A Portrait of the Artist as an Employee: The Impact of Personality on Career

Satisfaction

Author(s): James M. Loveland, Katherine E. Loveland, John W. Lounsbury and Danilo C.

Dantas

Source: International Journal of Arts Management , FALL 2016, Vol. 19, No. 1 (FALL

2016), pp. 4-15

Published by: HEC - Montréal - Chair of Arts Management

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44989674

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of

Arts Management

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Resources Management

A Portrait of the Artist as an Employee:

The Impact of Personality on Career Satisfaction

James M. Loveland, Katherine E. Loveland, John W. Lounsbury, Danilo C. Dantas

human resources (HR) managers in particular,

An artist is not paid for his labor but for as the companies hiring these artists are now James M. Loveland

his vision. is Assistant Professor of

facing the daunting and novel challenge of select-

- James McNeill Whistler Marketing at Xavier University.

ing and retaining artists as employees. This situ-

He has a PhD in Marketing

ation creates challenges for both the artists and

from Arizona State University

the HR managers, who have little guidance con- and a PhD in Psychology

cerning how artists might be expected to interact from the University of

with the firm and with work itself. Tennessee. His research inter-

Although

Although visual research

visualartists, itresearch

devoted

artists, therebeen

has hasdevoted

it haspiecemeal been beentocharacteristics

to the and the characteristics

piecemeal considerable andof

of

While we know that some artists, such as danc- ests include brand communi-

ers, face considerable challenges transitioning to ties, career development

fragmented, and the career trajectories of artists,

other fields (Jeffri and Throsby 2006), the roles and luxury marketing.

especially in the role of company employees, have

of disposition and career satisfaction have been Katherine E. Loveland

been ignored (for an exception, see Jeffri and

under-researched for artists as a group. From the is Assistant Professor of

Throsby 2006). In part, this fragmentation orig-

manager s point of view, it is important to under- Marketing at Xavier University.

inates in the notion that artists are unique and

stand the link between personality and career She has a PhD in Marketing

different, and thus academic research and the

satisfaction among artists, as more satisfied from Arizona State University.

popular literature have been long interested in - or Her research interests include

employees tend to be more productive (Kelloway

perhaps biased towards - those personal factors nostalgia, atmospherics,

et al. 2010) and to enjoy longer tenure with a firm

or dispositional tendencies that are related to the (Hofstetter and Cohen 2014). From the artist s

consumer decision-making

"artistic temperament" often associated with visual and self-concept.

point of view, it is important to understand the

artists (e.g., Drevdahl and Cattell 1958). link because career satisfaction, apart from being John W. Lounsbury

Consequently, research in this domain has con- a valuable construct from a purely humanistic recently retired from his posi-

centrated on the case study approach, giving sig- perspective, is highly predictive of key outcomes

tion as Professor of Psychology

nificance to personality facets or flaws of famous at the University of Tennessee.

such as life satisfaction (Seibert and Kraimer

His research centred on the

(or infamous) artists based on their work or on 2001). At the same time, art is a field that seems

role of personality in various

their life outcomes. While this approach makes to engender a career path that places considerable aspects of intrinsic and extrin-

for interesting conversation, it does little to illu- value on developing authenticity as a milestone sic career success.

minate the life of artists from an overarching (Svejenova 2005); this is in stark contrast to many

Danilo C. Dantas

perspective, or to highlight the unique needs of career fields, where progression is measured by

is Associate Professor of

artists as employees. Historically, visual artists tenure, promotion, increased span of control or

Marketing at HEC Montreal and

have tended to be self-employed, while today a other organizationally centred outcomes. a member of Development

considerable number are working within firms Investigating the artistic personality from the of Music Audiences in Quebec

(Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014). This underscores vantage point of artists as employees presents a (DMAQ). His research focuses

a need for more focused research addressing this unique opportunity to make a substantive con- on the themes of music mar-

population along constructs of importance to tribution both to managerial practice and to our keting and online marketing.

I 4 I INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS MANAGEMENT

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

conceptual understanding of the management of importance of assessing occupations by the com-

artists and their careers. We approach this chal- monalities in personality profiles, which furthers

lenge by addressing two overarching research ques- our understanding of Person- Environment fit

tions: What traits are important for the career (Holland 1996) and extends this model to the career

satisfaction of artists ? What insights do these traits field domain. In addition, we show how personality

provide about working as visual artists in North can translate into differences in the career satisfac-

America and what are the implications for HR man- tion of artists, which has implications for the recruit-

agers charged with the selection , retention and career ment, selection and training of artists.

development of these artists ?

This article is organized as follows. First, we

discuss the literature on personality and different

career outcomes, such as job performance and Artistic Tension in the Workplace

career satisfaction. Next, we discuss the linkages

between this literature and the nature of the work

It ofofgoesartistic

artisticendeavour;

without one

endeavour;

cannot saying

discuss that

artistsone creativity cannot discuss is a hallmark artists

performed by artists, focusing particularly on

creativity. Then, using 13 personality traits (and in an employment setting without mentioning the

career satisfaction) that are commonly used in nature of creativity in the workplace, along with

personnel selection settings, we investigate the the tension that it could cause. Although it might

seem counterintuitive, there has been wide con-

linkages between these personality traits and

career satisfaction among a sample of 566 artists sensus as to the nature of creativity, with scholars

who participated in a career assessment program arriving at essentially the same working definition

offered by their respective firms. Previous research across the span of nearly 50 years (cf. Feist 1998;

has demonstrated that artists generally experience Guilford 1950): creativity must both be new or

higher levels of career satisfaction than typical original (novel) and be useful (adaptive). Thus,

workers in other fields (Steiner and Schneider simply being significantly different from the norm

2013), but has not investigated the specific per- is not sufficient to be considered creative; an idea

or a work must also be useful to others in order to

sonality profiles that might influence these levels

of satisfaction. Following regression analysis and represent creativity. For freelance art, the ways in

investigation of the correlations between 13 per- which something might be useful is much more

sonality traits and career satisfaction, we discuss flexible and likely to vary greatly from project to

the importance of the significant relationships, project, as artists are able to choose the projects

providing preliminary guidance for HR managers they work on and thus exert a significant level of

tasked with managing artists, as well as insights control over when and how they express their crea-

into career development concerns for artists. tivity. In a corporate setting, this is not as likely to

This article makes several important contribu- be the case, as usefulness will be constrained by

tions to both academic research and managerial the organizational context, such as the type of

practice. First and foremost, we provide a solid products or services the company produces or the

empirical basis from which to investigate how artists industry in which it operates. This need to be cre-

are different from their peers in other career fields ative on demand, but to do so within a constrained

along traits that are managerially rather than clini- environment, in order to reach instrumental goals

cally focused. Furthermore, we demonstrate the is somewhat contradfctory to our cultural image

ABSTRACT

Although there is a long hist

tion along personality dimen

sonality on job and career s

vocational interests of those w

an analysis of personality and

settings. The personality tra

satisfaction. Other traits, suc

as well, though not as stron

managed. These implications

Career sa

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 1 • FALL 2016 H

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of the artist as a free spirit. The investigation of The importance of these relationships cannot

artists in the workforce thus offers a unique oppor- be overstated. As Holland (1996) notes, "people

tunity to better understand the combination of flourish in their work environment when there is

personality traits that allows individuals to suc- a good fit between their personality type and the

cessfully use their individual vision and artistic characteristics of the environment. Lack of con-

sense to meet organizational needs. gruence between personality and environment

leads to dissatisfaction" (p. 397). While there has

been some debate about the effectiveness of the

RIASEC (Personality-Environment, or P-E, fit)

Personality and Career Satisfaction model itself, the central tenet that individuals who

do not possess the right attributes will experience

The outcomes

outcomes

use of

in personality

a variety ofinfields

a variety

has been

in of predicting fields has career been more pressure and stress within the work setting,

largely supported by meta-analytic research pro- resulting in dissatisfaction, has received strong

viding evidence for the assertion that personality empirical support and has also served as the basis

for other models (cf. Schneider 1987; Schneider,

dimensions predict intrinsic (job and career satis-

faction) and extrinsic (manager ratings) job suc- Goldstein and Smith 1995). This employee dis-

satisfaction can lead to undesirable outcomes such

cess. This meta-analytic research (cf. Judge, Heller

and Mount 2002; Judge et al. 2013) has also as counterproductive behaviours (Kelloway et al.

shown that, across different career fields, the 2010) and staff turnover (Horn and Kinicki 2001).

validity coefficients support the widespread use Furthermore, artists have been shown to possess

of personality measures for selection and retention traits associated with undesirable organizational

purposes, further advancing meta-analytic behaviours, such as low levels of conformity, self-

research conducted a decade earlier (e.g., Barrick control, tolerance and personal warmth (Feist

and Mount 1991). These same studies uncovered 1998), suggesting that the poor P-E fit of artists

significant differences across career fields in terms working within firms could lead to particularly

of the relationship between personality and career negative outcomes. However, the work on P-E

fit has tended to focus on the individual in a career

success. Two important implications emerge from

this research stream: first, traits that are essential field based on interests and basic dispositional

to success in one field might not be predictive of factors, rather than on groups of people working

success in another; and second, because similar across different firms in the same field. We extend

career fields share similar personality/outcome the reasoning suggested by P-E fit, as well as the

relationships, occupations are shaped and defined logic of individual fit with organizations suggested

by the characteristics that are shared across dif- by Schneider (1987), to argue that enduring dis-

ferent work settings. Thus, identifying key per- positional factors (i.e., personality traits) will shape

sonality dimensions that are related to intrinsic overall career satisfaction. Thus, the trait/satisfac-

career success in a given field provides insights tion relationship reveals commonalities that will

into what demands are being placed upon not change across work settings - this presents

its members and how managers can adapt to real and usable guidance for managers who wish

these relationships. to hire and manage artists.

RFS1JMF

Des re

qui con

de la p

ristiqu

combl

et la s

travai

stabili

impor

de cet

Ces im

dans cet article.

Satisfac

I 6 I INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS MANAGEMENT

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

There are managerial activities that can mini- Agreeableness and Emotional Stability - have

mize negative outcomes due to poor P-E fit. For been validated in a variety of contexts, with

example, firms can mitigate variability in job decades of meta-analytic research supporting their

performance by creating rigid work environments continued use in personnel selection (cf. Barrick

or by focusing on improving elements of the and Mount 1991; Judge, Heller and Mount 2002).

work environment that are not conducive to a

These broad categories of traits, while highly effec-

positive employee disposition (Keller and Semmer tive, do not always provide a complete picture of

2013). In short, careful design of the work envi- the individual. Therefore, many researchers have

ronment can diminish some of the effects of advocated the use of so-called narrow traits. These

personality in the workplace. However, because traits, such as Work Drive and Customer Service

personality and interests are very important in Orientation, tend to be focused on dispositions

vocational decision-making and tend to be rela-

within particular contexts and have been shown

tively stable over time (Low et al. 2005; Lubiński,

to add incremental predictive value above and

Benbow and Ryan 1995), selection and career-

beyond the Big Five (e.g., Ashton 1998; Dudley

development activities that consider personality

et al. 2006; Lounsbury et al. 2002). The inventory

are an important means of improving work out-

used to assess these traits (the PSI) has been

comes for both the firm and the individual, and

administered, for a variety of purposes, to over

even reducing negative work outcomes (MacLane

six million individuals in a wide range of jobs and

and Walmsley 2010).

organizational settings (Lounsbury and Gibson

2013) and has been widely used in both academic

and professional settings (e.g., Lounsbury and

Method Gibson 2013; Loveland, Lounsbury et al. 2015;

Loveland, Thompson et al. 2015).

Overview

The career development firm eCareerFit.com Participants

provided the data used in this study. The data

The sample comprised 566 visual artists who

were gathered for organizational decision-making

completed the PSI as part of ongoing career

purposes in the arenas of recruitment, pre-employ-

development at their firms. Of the participants,

ment testing, succession planning, leadership

246 (43.5%) were male and 320 (56.5%) female.

development, and ongoing coaching and mentor-

In terms of age, 6 (1%) were under age 20; 84

ing. All participants completed the personality

(14.9%) between 20 and 30; 194 (34.3%)

inventory on a voluntary basis for the purpose of

between 31 and 40; 166 (29.4%) between 41

self-knowledge and career planning, with the

assessments paid for by their employers. and 50; 103 (18.2%) between 51 and 60; 14

Participants were free to use either their own name (2.5%) between 61 and 70; and 1 was over the

or a pseudonym. The personality instrument used age of 70. Of these individuals, 94 (16.6%)

was the Personal Style Inventory (PSI), a work- worked in the communications industry, 165

based measure that includes the Big Five personal- (29.2%) in entertainment and 103 (18.2%) in

ity markers along with eight narrow personality publishing, while 57 (10.0%) were freelance

traits. The Big Five personality traits - Openness artists and the remaining 147 (26.0%) worked

to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, in various other industries.

RESUMEN

Aunque se cuento con una larga historia

población en general en lo que se refier

sobre el impacto de la personalidad mis

concentrado sobre los atributos relacion

carrera artística. Para llenar este vacío

carrera con un muestreo de 566 artista

optimismo y estabilidad emocional se co

rísticas, como disposición a trabajar en eq

correlación. Los autores presentan los r

y sugieren orientaciones para futuras inv

Satisfacción con l

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 1 • FALL 2016 j 7 j

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Personality Factors career as a whole (Judge et al. 1995). Focusing on

overall career satisfaction is also a means of pre-

The PSI has been used in a variety of settings

venting the assessment of satisfaction from being

internationally, mainly for career development

unduly influenced by transient, job-specific issues,

and pre-employment screening purposes

such as an unpleasant manager or difficult work-

(Lounsbury and Gibson 2013). Following are

ing conditions, and is a more stable measure in

brief descriptions of the personality measures used

relation to personality traits. Career satisfaction

in the present study (along with Cronbach s a).

was assessed using a single-item measure of global

Assertiveness: disposition to speak up on matters

career satisfaction, for which there are no reliability

of importance, express ideas and opinions confi-

statistics. However, research has demonstrated

dently, defend personal beliefs, use initiative, and

that global indices of satisfaction can be more

exert influence in a forthright but non- aggressive

manner (Cronbach s a = .83). Conscientiousness:

valid than facet-based measures (Nagy 2002;

Scarpello and Campbell 1983).

dependability, reliability, trustworthiness, and

inclination to adhere to company norms, rules

and values (Cronbach s a = .74). Customer Service

Orientation: striving to provide highly responsive,

Results

personalized, quality service to (internal and exter-

nal) customers; putting the customer first; and

trying to satisfy the customer, even if it means Data regression wereapproach,

regression assessed which

approach, using which a forward-selection is appropriate

is appropriate

going above and beyond the job description or when there are no strong theoretical reasons for

policy (Cronbach s a = .69). Emotional Stability: entering variables in a specific order. This approach

overall high level of adjustment and emotional also prioritizes the variable with the strongest

resilience in the face of job stress and pressure correlation, followed by those with the strongest

(Cronbach s a = .81). Extraversion: tendency to partial correlation coefficients. We chose career

be sociable, outgoing, gregarious, expressive, satisfaction as the focal dependent variable,

warm-hearted and talkative (Cronbach s a = .83). because this is considered more important from

Image Management: disposition to regulate and a humanistic perspective and because it is a more

control self-presentation and image projected dur- global assessment of the individuals collective

ing- interactions (Cronbach s a = .82). Intrinsic work experiences. Regression results generated a

Motivation: tendency to be motivated by the chal- multiple correlation of R = .470 (p < .01), F(6,

lenge, meaning and significance of work 559) = 26.395, MSE = 1.16, p < .01, with the

(Cronbach s a = .82). Openness: receptivity to variables of Optimism (ß = .350, t(560) = 4.492,

change, innovation, novel experience and new p < .01), Teamwork Orientation (ß = .261, t(560)

learning (Cronbach s a = .78). Optimism: an = 4.215, p < .01), Work Drive (ß = .290, t(560) =

upbeat, hopeful outlook on situations, people, 4.747, p < .01), Assertiveness (ß = -.168, t(560) =

prospects and the future, even in the face of dif- -2.726, p < .01), Emotional Stability (ß = .253,

ficulty and adversity; a tendency to minimize t(560) = 3.069, p < .01) and Openness (ß = .350,

problems and persist in the face of setbacks t(560) = -2.144, p < .05). These results are reported

(Cronbach s a = .85). Teamwork Orientation: pro- in Table 1. We further investigated the correlations

pensity for working as part of a team and func- for each of the study variables with career satisfac-

tioning cooperatively on group efforts tion. These results, along with means and standard

(Cronbach s OL = .83). Tough-Mindedness: tendency deviations for all study variables, are included in

to make work decisions based on logic rather than Table 1 as well. The correlations for the study

on feelings or emotions. Work Drive: disposition variables ranged from high levels for Optimism

to work long hours (including overtime) and to (r= .388, />< .01) and Emotional Stability (r = .353,

keep an irregular schedule, investing high levels p < .01), more moderate levels for Teamwork

of time and energy into job and career; motivated Orientation (r= .271, p< .01), Work Drive (r= .213,

to extend oneself, if necessary, to finish projects, p < .01), Customer Orientation (r = .183, p < .01),

meet deadlines, be productive and achieve job Conscientiousness (r = AA',p< .01) and Extraversion

success (Cronbach s OL = .81). Visionary Thinking: (r = .155, p < .01), to low but still statistically

a personal style that emphasizes an organizational significant levels for Assertiveness (r = .102, p < .01),

vision and mission, development of corporate Openness (r= .088, />< .01) and Image Management

strategy, identification of long-term goals and (r = -.069, p < .01). Tough-Mindedness, Visionary

planning for future contingencies (Cronbach s a Thinkingznà Intrinsic Motivation did not produce

= .88). Career satisfaction was measured using a significant correlations with career satisfaction.

single-item global scale; respondents were asked

to evaluate their overall satisfaction with their

g INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS MANAGEMENT

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

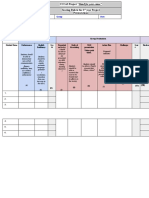

TABLE 1

MEANS, CORRELATIONS AND REGRESSION COEFFICIENTS (ß) FOR ARTISTS

Means Correlations

Dimension M SD Career Satisfaction ß

Asserti veness 3.43 .85 .102* -.168

Conscientiousness 3.18 .72 .141* NS

Customer Orientation 4.07 .68 .183* NS

Emotional Stability 3.28 .77 .353* .253

Extraversion 3.71 .80 .155* NS

Image Management 2.62 .81 -.069 NS

Intrinsic Motivation 3.72 .75 .001 NS

Openness 3.75 .73 .088* -.169

Optimism 3.68 .86 .388* .350

Teamwork Orientation 3.33 .80 .271* .261

Tough-Mindedness 2.84 .74 .033 NS

Visionary Style 3.22 .74 .013 NS

Work Drive 3.27 .81 .213* .290

Career Satisfaction 3.36 1.21

* p < .05

Discussion optimistic can also better handle negative feedback

about their work, because they view such an out-

come as impersonal and transitory, not personal

The connections results

connections of between

between this study

the personality the indicate personality multiple traits

traits

of artists and career satisfaction. In this sense, or permanent (Seligman 1990). Similarly, with

their more positive cognitive set, more optimistic

the contribution of the study is twofold. First,

artists are better equipped to handle job setbacks

regarding the arts management literature, the

and persevere in the face of adversity than their

study represents the first attempt to measure the

more pessimistic peers. Over time, such factors

impact of personality traits of artists, as employ-

will lead to higher levels of career satisfaction.

ees, on career satisfaction using a quantitative

An important implication of this finding is that

approach. Second, from a managerial point of

managers of artists should be vigilant to ensure

view, we propose a broader understanding of artist

that their more optimistic artistic employees do

management by showing which personality traits

not take on projects that are simply too expansive

have a significant influence on job outcomes. By or that are unfeasible, as they could easily over-

specifying the personality traits that lead to greater estimate their ability to complete projects

career satisfaction among artists, we aim to help (McNulty and Finchman 2012). The centrality

managers of artists better understand, and thus of optimism becomes especially problematic for

manage, the challenges faced by visual artists who managers when we consider that research has

create in service to organizational goals. shown that artists, compared to non-artists, are

More precisely, among the respondents, lower in emotional stability (Feist 1998). This is

Optimism was the trait most highly correlated likely driven by the nature of their work, as sen-

with career satisfaction. An obvious explanation sitivity towards potential threats and a focus on

for this finding is that artists have some degree of internal states are important aspects of working

anticipation of a positive outcome for their work, creatively. Thus, artists are more likely to be sensi-

whether it is personal satisfaction or financial tive to the failures that arise from their willingness

success in the marketplace. Artists who are more to attempt too much. The combination of higher

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 1 • FALL 2016 H

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

optimism and lower emotional stability will bring companies may want to recruit and hire indi-

unique challenges for both the manager and the viduals for artistic jobs who have higher levels

visual artist employed by the firm. Consequently, of extraversion. Second, those parties involved

managers should be circumspect in allowing art- in career planning and development should be

ists too much latitude, and perhaps provide spe- aware that extraversion is positively related to

cific "checkpoints" to ensure that artists' goals career satisfaction and, at the very least, inform

are realistic and achievable. individuals seeking vocational guidance in the

The findings for Emotional Stability are con- arts about the importance of building and main-

sistent with findings in other professions - those taining interpersonal relationships in order to

artists who are more stable and well adjusted are increase satisfaction. Third, since extraversion

better able to handle stress on the job (and in is related to higher levels of career satisfaction,

their personal lives), which is an inherent char- employers could offer employees working as

acteristic of most artist jobs (Kirchner 2011; artists more opportunities to talk, fraternize and

Kirschbaum 2007; Wills and Cooper 1984). The personally interact with each other (and other

types of stressor facing artists are often of high employees) through company-sponsored social

magnitude and persist throughout their careers. events, recreational groups, outings, luncheons,

They include pressure for financial success, heavy discussion groups, and other activities that facili-

competition from other artists, lack of venues tate social interaction, organizational connection

for showcasing their work, and lack of public and extraversion-related behaviours. Indeed, it

understanding of and appreciation for their cre- may be that one reason why extraverted artists

ations (Watts 2013). Other types of pressure that find higher career satisfaction is that the affili-

artists generally have to contend with include ative nature of extraversion allows them to per-

social isolation, continual demands for original- ceive greater overlap between their own artistic/

ity, unresolved personal issues, structural changes career goals and the goals of the organization.

in their artistic field (Kirschbaum 2007), and There are similar implications regarding the

reductions in funding for arts and culture finding of a positive relationship between

(National Endowment for the Arts [NEA] 2012). Teamwork Orientation and the career satisfaction

A general lack of access to counselling and mental of artists. Artists typically work on their own as

health resources (Grant 2010) contributes to the individual contributors and tend to be less social,

stress most artists face and favours artists who communal and collaborative (Feist 1998). Yet

are more emotionally resilient. Making matters those artists who are inclined towards teamwork

worse, the levels of emotional stability found in and working cooperatively are more satisfied

the present study tend to be lower than those with their careers. This aligns well with the cur-

seen within broader employment samples using rent trend towards working in teams - teamwork

a similar metric (cf. Lounsbury and Gibson 2013; is becoming a nearly universal fixture in the

Loveland, Thompson et al. 2015). However, as modern organizational workplace. However,

Feist (1998) reports, the gap between artists and team efforts could be derailed if care is not taken

non-artists does seem to be shrinking - perhaps to understand the different types of motivation

as more visual artists work within corporate that members of the team bring to it, especially

settings, artists, the educational setting and the the extent to which artists might be focused

workplace are slowly adapting together to the more on tasks than on the prosocial aspects

new relationship. needed for successful teamwork. Managers

Artists are widely regarded as being more should make sure that artists in a team context

introverted than extraverted. Indeed, several do not allow their focus on individual work to

studies (cf. Feist 1998) have shown that artists undermine their contribution to cooperative,

are more introverted than those in other occupa- interdependent efforts. In addition, artists work-

tions. However, the present results indicate that ing in an organization should be given oppor-

more extraverted artists are more satisfied with tunities to work on team projects and to become

their careers, which likely reflects the psychologi- members of cross-functional and interdisciplinary

cal benefits of being more sociable and affiliative, teams. Similarly, all other factors being equal

such as feeling less isolated and lonely, having (including abilities and prior work history), those

more friendships and acquaintanceships with hired for art positions should be team-oriented

other artists and others within the organizational and have a demonstrated ability to work co-

hierarchy, and experiencing reduced anxiety operatively and supportively with other employ-

through personal interaction and relationships. ees. This will lead to more satisfied, and thus

There are several organizational implications of more assiduous, employees in the long term.

the present findings concerning extraversion. The positive finding for Customer Service

First, all other factors being relatively equal, Orientation is consistent with an increasing

10 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS MANAGEMENT

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

emphasis, in the art world, on adopting a strong rules and values, something that may not come

commitment to customer service. This, again, naturally to all artists but that does lead to higher

is consistent with the idea that, in order to achieve career satisfaction, as it demonstrates a willing-

career success, artists must not focus solely on ness to allow one s artistic vision to be shaped by

their internal vision but incorporate their vision organizational needs and values.

with the needs of their customer, at both the Because working artists must simultaneously

organizational level and the consumer level. This tap into their creativity, which is often deeply

is particularly true for artists who interact directly personal, and meet organizational goals, the

with customers or who have a direct hand in ability to diplomatically straddle the boundary

producing customer experiences (Kubacki 2008). between the personal and the public is an impor-

The importance of customer service orientation tant skill for career satisfaction. The personality

as a valued attribute of artists is likely to increase traits of Assertiveness and Image Management

in the future given the multiple internal custom- both tap into this skill. For example, because

ers that artists working in companies must serve, much of the work done by artists is high in

such as marketing and sales personnel, and the autonomy, in order to ensure that their voice is

push for ever-increasing integration of artistic heard and their creative vision is understood by

work with other organizational functions. stakeholders, organizations should engage artists

The remaining variables that we found to be who are comfortable being assertive. Specifically,

positively related to career satisfaction among to experience higher levels of career satisfaction

artists - Conscientiousness, Work Drive, artists should be capable of speaking up on mat-

Assertiveness, Openness and Image Management ters of importance, expressing their ideas and

- have a lesser but still important impact on opinions confidently, and exerting influence in

career satisfaction. The main factors accounting a forthright but non-aggressive manner. When

for higher career satisfaction among artists, com- working with artists, HR managers should also

pared to the general working population, in recent build environments in which a free and open

work by Steiner and Schneider (2013) - namely exchange of ideas is encouraged and reinforced,

job variety and on-the-job learning and autonomy which is consistent with the creative and autono-

- can be directly related to the relationships we mous nature of most artistic work. At the same

found between career satisfaction and the vari- time, a willingness to engage in image manage-

ables of work drive, assertiveness and openness. ment is also important, in order to minimize

For example, because artists generally experience any organizational resistance to artistic work,

greater on-the-job autonomy than their counter- which is often done in isolation and is inevitably

parts in other fields (Steiner and Schneider 2013), a reflection of the artist s vision. Indeed, a dis-

it is unsurprising that higher career satisfaction position to regulate and control self-presentation

among artists is associated with higher work drive during interactions is likely to result in higher

and conscientiousness. Work drive entails the acceptance of ones work, with less conflict,

motivation to work long, irregular hours and to resulting in higher career satisfaction.

extend oneself, if necessary, to finish projects and The final personality trait that we found to be

meet deadlines, characteristics that are necessary positively correlated with career satisfaction among

for success in situations high in autonomy. Given artists - Openness - has clear implications for

the relatively autonomous nature of most artistic two of the characteristics that Steiner and

work, and the correlation we found between work Schneider (2013) found to be drivers of high levels

drive and career satisfaction among artists, HR of job satisfaction among artists: job variety and

managers would be well advised to engage artists on-the-job learning. Because artists enjoy a high

who are high in work drive. If organizations level of variety, and consequently learning, on the

engage artists who are lower in work drive, strate- job, our finding that openness to experience is

gies for maintaining productivity might include positively correlated with career satisfaction among

creating a more structured work environment artists is not surprising. We recommend that,

and imposing intermediate, shorter deadlines. when engaging artists, HR managers hire indi-

Similarly, conscientiousness is associated with viduals who are relatively high in openness.

dependability, reliability and trustworthiness, Managing artists in such a way as to foster

traits that facilitate successful work habits in their creativity within the constraints of a cor-

autonomous work environments. Because artistic porate structure represents a somewhat contra-

work is rarely supervised closely, artists need to dictory set of goals. The arts are a competitive

be capable of regulating their own work behav- industry - there is intense competition not only

iours in order to create in a dependable and reli- for talent but also for customers and scarce fund-

able manner. Another aspect of conscientiousness ing. This complexity could easily undermine

is the inclination to adhere to company norms, the cogent analysis or measurement of the

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 1 • FALL 2016 j ^ j

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

organizational effectiveness of an arts-related and conscientiousness, and comfortable connect-

organization (e.g., Turbide and Laurin 2009). ing and working with others, as expressed by the

This difficulty is amplified by the difficulties personality traits of extraversion, teamwork,

associated with managing the artistic talent customer orientation and openness. They should

within any organization. We contend that the also possess the emotional maturity and confi-

first step in making the task more tractable is to dence - as expressed by emotional stability,

understand what type of people are attracted to assertiveness, image management and optimism

working as artists and what type of career out- - necessary to bridge the gap between individual

comes they experience. creativity and organizational needs.

Managerial Implications Limitations and Suggestions for

Future Research

The outcomes,

outcomes,

relationship

such as such

performance

between and

as performance

satisfac- personality and and satisfac- career

tion, exists at an unusual intersection. On the one There could

couldareaffect

affecttheseveral the gathered

insights limitationsin insights

the to gathered this study in that the

hand, HR managers, many of whom use personal- work. First, the study centred on artists working

ity for selection purposes, are acutely aware of the in the visual arts and predominantly within organ-

value of personality as an instrument for gauging izations. Thus, it is not a foregone conclusion that

the potential effectiveness of employees. On the our implications would hold true for those in other

other hand, art as a field tends to be somewhat domains of art or for those not working within

insular and focused on development from the the confines of an organization. An interesting

perspective of talent, ability and performance. approach would be to investigate the importance

Ultimately, artists must display an ability to create of different personality factors and career satisfac-

- this is completely irrespective of personality or tion across different career domains of art, such

P- E fit, but is a very important component of as the performing arts or freelance practice.

career success, be it intrinsic or extrinsic. The However, given that more and more artists are

challenge is that of applying what HR knows to working in corporate settings, our results do high-

a distinct audience about which it knows very light the fact that managers likely face significant

little, for which talent and ability are often not challenges with this unique group. Second, our

trainable, and where many people believe that they data are cross-sectional in nature; it would be

have a true and unique calling to the profession interesting to know if there are changes across the

(cf. Dobrow and Tosti-Kharas 2011). career span of artists along these different traits.

Artists pose an interesting challenge to manag- Naturally, this would require the collection of

ers, as one of the major resources they bring to longitudinal data. Such data could provide insight

the workplace is their individual creativity, which, into how artists attempt to manage their careers

in order to form a mutually beneficial relation- and the effect of a corporate work setting on their

ship, must be directed towards the needs of the ultimate productivity as artists. Third, future

hiring organization. This challenge leads to both research could examine the criteria by which artists

benefits and costs from the point of view of the are evaluated. While job performance can be dif-

artist: the benefits of greater job variety, learning ficult to define in many professions, evaluating

and autonomy (Steiner and Schneider 2013), and job performance among visual artists is especially

the costs of lower-than-average income relative daunting. Such research would not only be useful

to education and lower job stability (Alper and in helping artists choose work settings that are

Wassail 2006; NEA 2008). Keeping in mind appropriate to their personal styles and preferences

both the benefits and the costs inherent to work- but also provide unique insights into how the

ing as an artist, our research suggests that HR corporate world is shaping the careers, and pot-

managers would be well advised to carefully entially the work, of artists. Finally, research on

consider the personalities of the artists they hire career satisfaction and intrinsic job success might

and devote managerial effort to the unique train- ignore other elements of how people assess their

ing and development needs of artists, rather than careers, with some researchers calling for a re-

taking a one-size-fits-all approach. Our findings conceptualization of the term "career success," to

suggest that artists are most likely to experience include other, more existential, elements of career

higher career satisfaction, and thus exhibit fewer (Heslin 2005). Thus, while this study has provided

intentions to quit and fewer counterproductive preliminary insights into how personality affects

behaviours, if they are both personally driven, as career satisfaction among visual artists, there is

expressed by the personality traits of work drive still considerable work to be done.

12 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS MANAGEMENT

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

References predictors of executive career success. Personnel

Psychology 48(3) , 485-519.

Alper, N.O., and G.H. Wassal. 2006. Artists' careers

and their labor markets. In Handbook of the economics Judge, T.A., D. Heller and M.K. Mount. 2002. Five-

of arts and culturey V.A. Ginsburgh and D. Thorsby, Factor Model of Personality: A meta-analysis. Journal

eds. (pp. 813-864). Amsterdam: North-Holland. of Applied Psychology 87 (3) , 530-54 1 .

Ashton, M.C. 1998. Personality and job performance: Judge, T.A., J.B. Rodell, R.L. Klinger, L.S. Simon and

The importance of narrow traits. Journal of E.R. Crawford. 2013. Hierarchical representations

of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in predicting

Organizational Behavior 19(3), 289-303.

job-performance: Integrating three organizing frame-

Barrick, M.R., and M.K. Mount. 1991. The Big Five

works with two theoretical perspectives. Journal of

personality dimensions and job performance:

Applied Psychology 98(6), 875-925.

A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology 44(1), 1-26.

Keller, A.C., and N.K. Semmer. 2013. Changes in

Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor.

situational and dispositional factors as predictors of

2014. Craft and fine artists: Job outlook.

job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior 83(1),

Occupational outlook handbook. Accessed 88-98.

13 December 2014 at http://www.bls.gov/ooh/

arts-and-design/craft-and-fine-artists.htm#tab-6.

Kelloway, K.E., L. Francis, M. Prosser and J.E.

Cameron. 2010. Counterproductive work behavior

Dobrow, S.R., and J. Tosti-Kharas. 201 1. Calling: The

as protest. Human Resource Management Review

development of a scale measure. Personnel Psychology

20(1), 18-25.

64(4), 1001-1049.

Kirchner, J.M. 201 1 . Incorporating flow into practice

Drevdahl, J.E., and R.B. Cattell. 1958. Personality and

and performance. Work 4 0(3), 289-296.

creativity in artists and writers. Journal of Clinical

Kirschbaum, C. 2007. Careers in the right beat: US jazz

Psychology 14(2), 107-111.

musicians' typical and non-typical trajectories. Career

Dudley, N.M., K.A. Orvis, J.E. Leblecki and J.M.

Development International 1 2(2) , 1 87-20 1 .

Cortina. 2006. A meta-analytic investigation of

Kubacki, K. 2008. Jazz musicians: Creating service

conscientiousness in the prediction of job perform-

experience in live performance. International Journal

ance: Examining the intercorrelations and the incre-

mental validity of narrow traits. Journal of Applied

of Contemporary Hospitality Management 20(4),

401-411.

Psychology 91(1), 40-57.

Lounsbury, J.W., and L.W. Gibson. 2013. Personal

Feist, G.J. 1998. A meta-analysis of personality in

style inventory. Knoxville, TN: Resource Associates.

scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social

Psychology Review 2(4), 290-309. Lounsbury, J.W., E. Sundstrom, J.M. Loveland and

L.W. Gibson. 2002. Broad versus narrow traits in

Grant, D. 2010. Art students' mental health: A com-

predicting academic performance of adolescents.

plicated picture. Chronicle of Higher Education ,

Learning and Individual Differences 14(1), 65-75.

12 November. Accessed 12 December 2014 at http://

chronicle.com/blogs/ arts/ art-students-men tal- Loveland, J.M., J.W. Lounsbury, S.-H. Park and DA.

health-a-complicated-picture/27 923. Jackson. 2015. Are salespeople born or made?

Biology, personality, and the career satisfaction of

Guilford, J.P. 1950. Creativity. Ameńcan Psychologist

5(5), 444-454. salespeople. Journal of Business and Industrial

Marketing 30(2) , 233-240.

Heslin, P.A. 2005. Conceptualizing and evaluating

Loveland, J.M., S.A. Thompson, J.W. Lounsbury and

career success. Journal of Organizational Behavior

26(2), 113-126. D. Dantas. 2015. Is diffusion of marketing com-

petence necessary for a market orientation? A com-

Hofstetter, H., and A. Cohen. 2014. The mediating parative investigation of marketing managers and

role of job content plateau on the relationship their defining traits. Marketing Intelligence and

between work experience characteristics and early Planning 33(3) , 469-484.

retirement and turnover intentions. Personnel Review

Low, K.D., M. Yoon, B.W. Roberts and J. Rounds.

43(3), 350-376.

2005. The stability of vocational interests from early

Holland, J.L. 1996. Exploring careers with a typology: adolescence to middle adulthood: A quantitative

What we have learned and some new directions.

review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin

Ameńcan Psychologist 5 1 (4) , 397-406. 131(5), 713-737.

Horn, P.W., and A.J. Kinicki. 2001. Toward a greater Lubiński, D., C.P. BenbowandJ. Ryan. 1995. Stability

understanding of how dissatisfaction drives employee of vocational interests among the intellectually gifted

turnover. Academy of Management Journal 44(5), from adolescence to adulthood: A 1 5-year longi-

975-987.

tudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology 80(1),

Jeffri, J., and D. Throsby. 2006. Life after dance: Carper196-200.

transition of professional dancers. International

MacLane, C.N., and P.T. Walmsley. 2010. Reducing

Journal of Arts Management 8(3), 54-63. counterproductive work behavior through employee

Judge, T.A., D.M. Cable, J.W. Boudreau and R.D.selection. Human Resource Management Review

Bretz Jr. 1995. An empirical investigation of the20(1), 62-72.

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 1 • FALL 2016 13

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

McNulty, J.K., and F.D. Finchman. 2012. Beyond Seibert, S.E., and M.L. Kraimer. 2001. The Five-Factor

positive psychology? Toward a contextual view of Model of Personality and career success. Journal of

psychological processes and well-being. American Vocational Behavior 58(1), 1- 21 .

Psychologist 67 {2) y 101-110. Seligman, M.E. 1990. Learned optimism. New York:

Pocket Books.

Nagy, M.S. 2002. Using a single-item measure to meas-

ure facet job satisfaction. Journal of Occupational Steiner, L., and L. Schneider. 2013. The happy artist:

and Organizational Psychology 75(1), 77-86. An empirical application of the Work-Performance

National Endowment for the Arts. 2008. Artists in the Model. Journal of Cultural Economics 37(2),

225-246.

workforce , 2000 to 2005 . Washington: Author.

Accessed 6 February 2014 at http://arts.gov/sites/ Svejenova, S. 2005. "The path with the heart": Creating

default/files/ArtistsInWorkforce.pdf. the authentic career. Journal of Management Studies

42(5), 947-974.

National Endowment for the Arts. 2012. How the

United States funds the arts. Washington: Author.

Turbide, J., and C. Laurin. 2009. Performance meas-

urement in the arts sector: The case of the per-

Accessed 16 December 2014 at http://arts.gov/sites/

default/files/how-the-us-funds-the-arts.pdf.

forming arts. International Journal of Arts

Management 1 1 (2), 56-70.

Scarpello, V., and J.P. Campbell. 1983. Job satisfaction:

Watts, A. 2013. What kind of stress do full-time com-

Are all the parts there? Personnel Psychology 36(3),

377-600.

posers experience? Slate , 26 October. Accessed

6 February 2014 at http://www.slate.com/blogs/

Schneider, B. 1987. The people make the place. quora/ 2013/10/21/ what_kind_of_stress_do_full_

Personnel Psychology 40(3), 437-433. time_ composers_experience.html.

Schneider, B., H.W. Goldstein and D.B. Smith. 1995. Wills, G.I., and C.L. Cooper. 1984. Pressures on pro-

The ASA framework: An update. Personnel Psychology fessional musicians. Leadership and Organization

48(4), 747-773. Development Journal 5(4), 17-20.

APPENDIX 1

LISTING AND DESCRIPTION OF TRAITS

Dimension Description

Agreeableness Propensity to work well in a team environment and to work cooperatively within

a work group (7 items)

Conscientiousness Tendency to be reliable, organized and rule-following (9 items)

Emotional Overall level of adjustment and emotional resilience in the face of job stress

Stability and pressure (6 items)

Extraversion Disposition to be sociable, gregarious, warm-hearted and talkative (7 items)

Openness Propensity to seek out change, innovation and new experiences (9 items)

Assertiveness Ability to assert oneself, take charge of situations, speak up on matters of

importance and defend personal beliefs (8 items)

Image Tendency to monitor, observe, regulate and control how one presents oneself

Management and to carefully regulate the image one projects in work interactions (6 items)

Intrinsic Disposition to be focused more on the pleasure associated with work itself than

Motivation on the financial rewards of work; interested in the challenge, meaning, autonomy,

variety and significance of work (6 items)

Optimism An upbeat and hopeful outlook concerning people, prospects and the future; tendency

to not focus on problems, even in the face of setbacks and adversity (6 items)

Tough- Tendency to appraise information and make work-related decisions based on logic,

Mindedness facts and data rather than on feelings, values or intuition (8 items)

(continued on next page )

14 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS MANAGEMENT

This content downloaded from

140.1f:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LISTING AND DESCRIPTION OF TRAITS (continued)

Dimension Description

Work Drive Disposition to work long hours and to invest time and energy in job and career;

motivated to do whatever it takes to complete projects, meet deadlines and

achieve job success (8 items)

Visionary A style that emphasizes achieving an ambitious organizational vision and mission;

Thinking focused on developing a strong corporate strategy and planning for future

contingencies (8 items)

Customer Desire to provide personalized, responsive and high-calibre service to customers,

Orientation putting the customer first, wanting to keep customers satisfied - even if it means

going above and beyond normal job requirements (8 items)

Career Overall level of satisfaction with one's chosen career path (1 item)

Satisfaction

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 1 • FALL 2016 15

This content downloaded from

140.123.22.21 on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 12:13:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- D&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveDocument208 pagesD&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveLeonardo Sanchez100% (12)

- DGR LR40 ManualDocument59 pagesDGR LR40 ManualPiratsik Orbotana20% (5)

- Art Appreciation Course OutlineDocument3 pagesArt Appreciation Course OutlineFrance BejosaNo ratings yet

- Abstract Chapter 2 How Languages Are LearnedDocument4 pagesAbstract Chapter 2 How Languages Are LearnedDanielGonzálezZambranoNo ratings yet

- PS1 SolutionDocument8 pagesPS1 SolutionColin Jennings100% (1)

- Warehouse Management System in SAPDocument10 pagesWarehouse Management System in SAPWaaKaaWNo ratings yet

- Using BAPI To Migrate Material Master - BAPI's in SAP - SAPNutsDocument10 pagesUsing BAPI To Migrate Material Master - BAPI's in SAP - SAPNutsAshish MohapatraNo ratings yet

- Work CV - Jen YuDocument2 pagesWork CV - Jen Yuapi-455091043No ratings yet

- Musical MashDocument6 pagesMusical MashSuccsurraNo ratings yet

- Hall - 2010 - Making Art, Teaching Art, Learning Art ExploringDocument8 pagesHall - 2010 - Making Art, Teaching Art, Learning Art ExploringAlexandra NavarroNo ratings yet

- Yinka GraphicWorkDocument6 pagesYinka GraphicWorkYinka DanmoleNo ratings yet

- Rivera 2012 Hiring As Cultural MatchingDocument24 pagesRivera 2012 Hiring As Cultural Matchingjannah.sherif06No ratings yet

- Syllabus-OBE - Ge 6 Art Appreciation BUSINESS ADMINISTRATIONDocument11 pagesSyllabus-OBE - Ge 6 Art Appreciation BUSINESS ADMINISTRATIONVanessa L. VinluanNo ratings yet

- Arts Education Policy ReviewDocument14 pagesArts Education Policy Reviewdiajeng lissaNo ratings yet

- Ego Boundaries and Self-Esteem: Two Elusive Facets of The Psyche of Performing MusiciansDocument19 pagesEgo Boundaries and Self-Esteem: Two Elusive Facets of The Psyche of Performing Musiciansparisa baseremaneshNo ratings yet

- Brand Guide: Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & CommunicationsDocument50 pagesBrand Guide: Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & CommunicationskimillerNo ratings yet

- Horticulturist 122.fullDocument5 pagesHorticulturist 122.fullbillNo ratings yet

- The Stanford Daily: Class of 11 Starts Job HuntDocument8 pagesThe Stanford Daily: Class of 11 Starts Job Hunteic4659No ratings yet

- Assessing Professional Attributesusing Conjoint AnalysisDocument20 pagesAssessing Professional Attributesusing Conjoint AnalysisivNo ratings yet

- Perdev MELC Learning GuideDocument8 pagesPerdev MELC Learning GuideJonel Joshua RosalesNo ratings yet

- Crafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraDocument25 pagesCrafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraCastañeda ValeriaNo ratings yet

- Class-ART APPRECIATION PresentationDocument11 pagesClass-ART APPRECIATION PresentationCharmaine JanorasNo ratings yet

- A Career Guide For Studio Art Majors: SkillsDocument9 pagesA Career Guide For Studio Art Majors: SkillsNenkent AndersonNo ratings yet

- Improvisation in Service PerformancesDocument22 pagesImprovisation in Service PerformancesTam NguyenNo ratings yet

- Domainbsusan Orr Article Issue 10 PP 9 13Document5 pagesDomainbsusan Orr Article Issue 10 PP 9 13api-279812605No ratings yet

- Jordan, Noel - How New Is New MediaDocument11 pagesJordan, Noel - How New Is New MediaSandra SankatNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Assessment ProjectDocument7 pagesRenaissance Assessment Projectapi-707110713No ratings yet

- An Evidence-Based Roadmap For Success: Part 1-The Bumpy Road of Graduate SchoolDocument15 pagesAn Evidence-Based Roadmap For Success: Part 1-The Bumpy Road of Graduate SchoolMothi GhimireNo ratings yet

- Jackie Otero - Music Resume For WebDocument1 pageJackie Otero - Music Resume For WebJackie OteroNo ratings yet

- Developing HR Strategy: May 2010 Issue 32Document24 pagesDeveloping HR Strategy: May 2010 Issue 32Augustin IordacheNo ratings yet

- Impact of The Perceived Image of Celebrity Endorsers On Tourists' Intentions To VisitDocument14 pagesImpact of The Perceived Image of Celebrity Endorsers On Tourists' Intentions To VisitCyprien DelaporteNo ratings yet

- Senior Residents Views On The Meaning Of.19Document4 pagesSenior Residents Views On The Meaning Of.19N N100% (1)

- Brochure IntroDocument1 pageBrochure IntroShahed FacebookNo ratings yet

- Aom-Dll 17-21 Week 3Document4 pagesAom-Dll 17-21 Week 3frances_peña_7No ratings yet

- Art App Module BSFDocument19 pagesArt App Module BSFJumreih CacalNo ratings yet

- Downs and Windchief 2015 Vol27 Issue 2Document8 pagesDowns and Windchief 2015 Vol27 Issue 2Alan DvořákNo ratings yet

- Musical and Social Communication in Expert Orchestral PerformanceDocument19 pagesMusical and Social Communication in Expert Orchestral PerformanceAna HespanhaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Art and The ArtistDocument4 pagesThe Role of Art and The ArtistNahla LeilaNo ratings yet

- Thang Đo OCBDocument8 pagesThang Đo OCBMai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Who Goes FreelanceThe Determinants of Self-Employment For ArtistsDocument22 pagesWho Goes FreelanceThe Determinants of Self-Employment For ArtistsJeffJeffNo ratings yet

- The Role of Art and The Artist Edgar H. ScheinDocument3 pagesThe Role of Art and The Artist Edgar H. ScheinBetsey Merkel100% (1)

- Art and MusicDocument2 pagesArt and MusicflaviohoboNo ratings yet

- White BELTINGAcademicDiscipline 2011Document4 pagesWhite BELTINGAcademicDiscipline 2011MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- HRM Chapter 10Document28 pagesHRM Chapter 10Shahadat Hossain TipuNo ratings yet

- Crafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraDocument25 pagesCrafting A Job Revisioning Employees As Active CraOrnela RigottiNo ratings yet

- Area Appreciation 1Document25 pagesArea Appreciation 112Jagtap HritikaNo ratings yet

- Cres AssignmentDocument5 pagesCres AssignmentFahad LumambasNo ratings yet

- Box 3.15 Focus On Student Research: Developing A Thematic Analysis GridDocument2 pagesBox 3.15 Focus On Student Research: Developing A Thematic Analysis GridMuhammad MoazNo ratings yet

- Knowledge 2Document16 pagesKnowledge 2Jake Arman PrincipeNo ratings yet

- PuchainaDocument21 pagesPuchainaAlfonso RomeroNo ratings yet

- 潘玥 EAED定校+专业 2Document1 page潘玥 EAED定校+专业 2panyue99999No ratings yet

- Speech Pathologists' Professional Identity in Response To Working With AssistantsDocument1 pageSpeech Pathologists' Professional Identity in Response To Working With AssistantsKaren DanielaNo ratings yet

- Cuff WordsImagesAlchemy 1982Document9 pagesCuff WordsImagesAlchemy 1982untilted1212No ratings yet

- Img 0001Document4 pagesImg 0001Zico RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Estudo de Caso - Professor ArtistaDocument51 pagesEstudo de Caso - Professor ArtistaHelena FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Andrew Mayo Added Value From HR MetricsDocument28 pagesAndrew Mayo Added Value From HR MetricsVinita SeshadriNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Grid CCCA3 Stand For Your CauseDocument2 pagesEvaluation Grid CCCA3 Stand For Your CauseMohamed RahalNo ratings yet

- ThinkerDocument1 pageThinkerindhraniNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-692586049No ratings yet

- Megan Meyer: Product Design PortfolioDocument30 pagesMegan Meyer: Product Design PortfoliomeganmeyNo ratings yet

- EGADE Atr Brochure EMBA - GRL - PPDocument9 pagesEGADE Atr Brochure EMBA - GRL - PPGabo S.nNo ratings yet

- Teacher As PerformerDocument20 pagesTeacher As PerformerPedro Braga100% (2)

- DLL Week 6Document4 pagesDLL Week 6maria victoria sagaysay100% (1)

- VLSI QnA - Interview Questions On Blocking and Nonblocking AssignmentsDocument3 pagesVLSI QnA - Interview Questions On Blocking and Nonblocking AssignmentsVIKRAMNo ratings yet

- Constitution and By-Laws of SSCDocument12 pagesConstitution and By-Laws of SSCJaypee Mercado Roaquin100% (1)

- Coca Cola ManagementDocument87 pagesCoca Cola Managementgoswamiphotostat43% (7)

- English: Quarter 1 - Module 7Document26 pagesEnglish: Quarter 1 - Module 7Jhing Loren86% (14)

- The Psychology of Effective CoachingDocument454 pagesThe Psychology of Effective CoachingLuchoNo ratings yet

- Flamenco FormsDocument3 pagesFlamenco FormsNayvi KirkendallNo ratings yet

- MAT 171 Precalculus Algebra Section 9-7 Parametric EquationsDocument10 pagesMAT 171 Precalculus Algebra Section 9-7 Parametric EquationsZazliana IzattiNo ratings yet

- Effect of English Teachers EffectivenessDocument3 pagesEffect of English Teachers EffectivenessMaybelle Tecio PabellanoNo ratings yet

- Hypertension, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians in Ulaanbaatar, MongoliaDocument6 pagesHypertension, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians in Ulaanbaatar, MongoliaUurtsaikh BaatarsurenNo ratings yet

- Development of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingDocument221 pagesDevelopment of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingsekharsamyNo ratings yet

- SYLLABUS Communication ArtsDocument8 pagesSYLLABUS Communication ArtsPhee May DielNo ratings yet

- Sultans of Swing TabDocument5 pagesSultans of Swing TabNadiaNo ratings yet

- De Guzman VDocument100 pagesDe Guzman VRoel PukinNo ratings yet

- Maoism in Bangla PDFDocument15 pagesMaoism in Bangla PDFAyub Khan JrNo ratings yet

- Drugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravisDocument3 pagesDrugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravispapitomalosoNo ratings yet

- SotDL - Scions of The BetrayerDocument28 pagesSotDL - Scions of The BetrayerGabrijel Klarić100% (2)

- Dustin Hoffman Masterclass NotesDocument5 pagesDustin Hoffman Masterclass NotesDorian BasteNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Intro SociologyDocument13 pagesFinal Exam Intro SociologyJoseph CampbellNo ratings yet

- UGCF-Flowchart (4 Yrs Course)Document4 pagesUGCF-Flowchart (4 Yrs Course)cooljishu2020No ratings yet