Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tempest

Tempest

Uploaded by

Adrish DeyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Jo-Ann Shelton - As The Romans Did - A Sourcebook in Roman Social History-Oxford University Press (1997) PDFDocument505 pagesJo-Ann Shelton - As The Romans Did - A Sourcebook in Roman Social History-Oxford University Press (1997) PDFChilcos Flavian91% (22)

- Racism IN SHAKESPEARE'S THE TEMPESTDocument14 pagesRacism IN SHAKESPEARE'S THE TEMPESTSiddhartho Sankar Roy100% (4)

- Caliban's CharacterDocument1 pageCaliban's CharacterMiss_M90No ratings yet

- UhuruDocument9 pagesUhuruapi-303025168No ratings yet

- The Tempest Within ProsperoDocument7 pagesThe Tempest Within ProsperoElizabeth100% (2)

- The Floyd Family Whole ClothLondon To Georgia in Eight GenerationsDocument158 pagesThe Floyd Family Whole ClothLondon To Georgia in Eight GenerationsMargaret Woodrough100% (2)

- Prospero-Caliban Relationship In: The TempestDocument17 pagesProspero-Caliban Relationship In: The TempestShah RajNo ratings yet

- A Post-Colonial Interpretation of The TempestDocument4 pagesA Post-Colonial Interpretation of The TempestMuHammAD ShArjeeLNo ratings yet

- The Tempest As A Post Colonial PlayDocument16 pagesThe Tempest As A Post Colonial PlayJannatul Nayma MouNo ratings yet

- The Tempest: As A Post-Colonial PlayDocument16 pagesThe Tempest: As A Post-Colonial PlayShah Raj100% (1)

- Postcolonial Reading of William Shakespeare'S: The TempestDocument4 pagesPostcolonial Reading of William Shakespeare'S: The TempestMuHammAD ShArjeeLNo ratings yet

- Caliban 1Document1 pageCaliban 1peopleupcheererNo ratings yet

- Caliban The TempestDocument15 pagesCaliban The TempestSelma HadzicNo ratings yet

- The Tempest-NotesDocument3 pagesThe Tempest-Notesapi-336553511No ratings yet

- Parallels and Contrasts in ShakespeareDocument3 pagesParallels and Contrasts in ShakespeareKingshuk Mondal50% (2)

- Chapter 1 in The Beginning .AbdelghaniDocument3 pagesChapter 1 in The Beginning .Abdelghanizahi100% (1)

- English Literature: The Relationship Between Prospero and Caliban Is That of The Coloniser and The Colonised.'discussDocument3 pagesEnglish Literature: The Relationship Between Prospero and Caliban Is That of The Coloniser and The Colonised.'discusshiral baidNo ratings yet

- ThemesDocument5 pagesThemesXaresh Noor100% (1)

- Tempest As A Postcolonial PlayDocument4 pagesTempest As A Postcolonial PlayMonalisa01No ratings yet

- The TempestDocument2 pagesThe Tempest93fionachangNo ratings yet

- Would Control My Dam's God, Setebos, / and Make A Vassal of Him." (I, Ii, 372-74), But Even When He MeetsDocument6 pagesWould Control My Dam's God, Setebos, / and Make A Vassal of Him." (I, Ii, 372-74), But Even When He MeetsSakshi Sadhana ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- The Tempest Revision 1Document11 pagesThe Tempest Revision 1renell simonNo ratings yet

- Colonisation in The TempestDocument1 pageColonisation in The Tempest62459No ratings yet

- Key Themes - BBCDocument4 pagesKey Themes - BBCremelroseNo ratings yet

- A Reimagining of Shakespeare's "The Tempest" in Toufann.Document17 pagesA Reimagining of Shakespeare's "The Tempest" in Toufann.caitlinhokage08No ratings yet

- CalibanDocument2 pagesCalibanrehan ahmedNo ratings yet

- Theme of The Play "The Tempest"Document4 pagesTheme of The Play "The Tempest"Layba KhalidNo ratings yet

- Sample Post Colonial Reading of The TempestDocument5 pagesSample Post Colonial Reading of The TempestEmerick AubameyangNo ratings yet

- The Difficulty of Distinguishing "Men" From "Monsters"Document4 pagesThe Difficulty of Distinguishing "Men" From "Monsters"Arihant KumarNo ratings yet

- Tempest NotesDocument9 pagesTempest Notesneet2025rudynmNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study Between ShakespearesDocument6 pagesA Comparative Study Between ShakespearesCenwyNo ratings yet

- Attitudes Towards ProsperoDocument2 pagesAttitudes Towards ProsperoMiss_M90No ratings yet

- Imperialism in The TempestDocument3 pagesImperialism in The TempestaayushNo ratings yet

- The Tempest-Plot SummaryDocument4 pagesThe Tempest-Plot SummaryboomalNo ratings yet

- Caliban: Shakespeare's Howling Monster: The TempestDocument3 pagesCaliban: Shakespeare's Howling Monster: The Tempestvirginia fradeNo ratings yet

- AvdicDocument20 pagesAvdicpepper2008No ratings yet

- English Literature Project 2 - Tempest by Scott Vareso DavidDocument13 pagesEnglish Literature Project 2 - Tempest by Scott Vareso DavidSkottayy0% (1)

- Craming Exa EnglishDocument1 pageCraming Exa EnglishEmerick AubameyangNo ratings yet

- The Tempest - Post Colonial ReadingDocument4 pagesThe Tempest - Post Colonial ReadingDhanush NNo ratings yet

- Shadab Jamil Drama Assignment Sem IIDocument2 pagesShadab Jamil Drama Assignment Sem IIShadab JamilNo ratings yet

- End of Year EssayDocument3 pagesEnd of Year EssayAna PecchioNo ratings yet

- English PPT PresentationDocument9 pagesEnglish PPT PresentationVihaan JNo ratings yet

- HFVBBDocument2 pagesHFVBBclashofclans.brothers69No ratings yet

- Analysis of Major CharactersDocument3 pagesAnalysis of Major CharactersMechiet SoniaNo ratings yet

- Tempest NotesDocument4 pagesTempest NotesAfraz AliNo ratings yet

- The Tempest and PowerDocument5 pagesThe Tempest and PowerAnthony Read83% (6)

- Second Paper ShakespeareDocument2 pagesSecond Paper ShakespeareMaria PrietoNo ratings yet

- Tempest VideoDocument4 pagesTempest Videoqs5cj2h49wNo ratings yet

- Throughout Act The Question of Rightful Authority, A MajorDocument14 pagesThroughout Act The Question of Rightful Authority, A Majoryingy0116No ratings yet

- Tempest WordDocument6 pagesTempest WordM vemaiahNo ratings yet

- The TempestDocument3 pagesThe Tempesthassan20572No ratings yet

- Themes TempestDocument3 pagesThemes Tempestapi-375048250% (2)

- Tempest QuestionsDocument2 pagesTempest QuestionslukehyunohNo ratings yet

- Caliban EssayDocument1 pageCaliban EssayknightissavageNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's The Tempest and Post ColonialismDocument13 pagesShakespeare's The Tempest and Post Colonialismchristianpranay83% (6)

- Notes On Shakespeare's The Tempest: Tempestuous ThoughtsDocument4 pagesNotes On Shakespeare's The Tempest: Tempestuous Thoughtsfcrocco100% (3)

- How Does Prospero Establish The Brave NeDocument11 pagesHow Does Prospero Establish The Brave NeIllıllı AMAZING SPIDER MAN IllıllıNo ratings yet

- Tempest EssayDocument19 pagesTempest Essaycedriclamb100% (1)

- The Tempest Revision2Document36 pagesThe Tempest Revision2Kai KokoroNo ratings yet

- The Tempest by William Shakespeare (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandThe Tempest by William Shakespeare (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- Student Camp 2021: Ministry of Education & YouthDocument22 pagesStudent Camp 2021: Ministry of Education & Youthhowelljoshua23No ratings yet

- Ten Times More Ebook - C.J. OrtizDocument13 pagesTen Times More Ebook - C.J. OrtizmeNo ratings yet

- Fire Eater's PDFDocument5 pagesFire Eater's PDFPatrick DuhamelNo ratings yet

- Hunters Sufis Soldiers and Minstrels TheDocument22 pagesHunters Sufis Soldiers and Minstrels TheMohammed GhazalNo ratings yet

- Unit 11 LecturesDocument7 pagesUnit 11 Lecturesthefiasco110No ratings yet

- Closer Union (Attempts at Regional Integration)Document19 pagesCloser Union (Attempts at Regional Integration)jemimaNo ratings yet

- Reconstruction DBQDocument29 pagesReconstruction DBQSarah Chu50% (2)

- ReconstructionDocument56 pagesReconstructionyatada s.No ratings yet

- Dragon 408 PDFDocument46 pagesDragon 408 PDFDanielL'Abbe100% (3)

- Sky's End: By: Elisabeth TrebleDocument10 pagesSky's End: By: Elisabeth TrebleElisabeth TrebleNo ratings yet

- On The Age of Exploration Affecting Philippine HistoryDocument2 pagesOn The Age of Exploration Affecting Philippine Historymonkeyballs12360% (5)

- Luisa Valdez-The Middle Passage EssayDocument5 pagesLuisa Valdez-The Middle Passage EssayLuisa ValdezNo ratings yet

- Noah's SF 181 With Attached DocumentsDocument16 pagesNoah's SF 181 With Attached DocumentsEMPRESS_OM100% (4)

- Creole Voodoo GlossaryDocument14 pagesCreole Voodoo Glossaryadamsmorticia100% (1)

- Athens and Sparta WorksheetDocument1 pageAthens and Sparta WorksheetOlivia ScallyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Section 3 NotesDocument6 pagesChapter 4 Section 3 NotesJaysway 16No ratings yet

- Apush Thesis Statement ExamplesDocument8 pagesApush Thesis Statement Examplesgbwygt8n100% (2)

- Civil Rights Overview: Understandings and QuestionsDocument107 pagesCivil Rights Overview: Understandings and QuestionsPhil JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Capitalist Patriarchy and Socialist FeminismDocument23 pagesCapitalist Patriarchy and Socialist FeminismindrajitNo ratings yet

- Historiography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?Document2 pagesHistoriography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?sofiaNo ratings yet

- Prayers That Break Iron YokesDocument3 pagesPrayers That Break Iron YokesDivino Henrique SantanaNo ratings yet

- Brazil Geography and History PresentationDocument35 pagesBrazil Geography and History PresentationJoshua Miranda100% (1)

- Author's Note From Conform by Glenn BeckDocument6 pagesAuthor's Note From Conform by Glenn BeckSimon and SchusterNo ratings yet

- Marche SlaveDocument2 pagesMarche SlaveLilika94No ratings yet

- 240 Hedwig Dohm Women's Vote 58Document18 pages240 Hedwig Dohm Women's Vote 58Beatriz VieiraNo ratings yet

- Venice: Portugal's Eastern Trade: 1508-1595Document5 pagesVenice: Portugal's Eastern Trade: 1508-1595Tay MonNo ratings yet

- Something RandomDocument3 pagesSomething RandomJames100% (1)

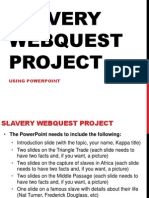

- Slavery WebquestDocument4 pagesSlavery Webquestapi-244459124No ratings yet

Tempest

Tempest

Uploaded by

Adrish DeyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tempest

Tempest

Uploaded by

Adrish DeyCopyright:

Available Formats

William Shakespeare’s The Tempest is a play from the beginning of the

seventeenth century. It is believed to be one of Shakespeare’s last works.

If considered from a postcolonial lens it can be interpreted that in this work

Shakespeare offers an examination of colonization, particularly the moral

aspects of it. In The Tempest the idea of colonization is communicated

primarily through the relationship between the colonizers and the colonized in

the play, specifically the relationship between Prospero and Caliban, and the

parallels between the process of European colonization and the plot of the

play. A chief idea that Shakespeare communicates throughout the play is the

idea of colonization and the relationship between colonizers and colonized.

During the time when The Tempest was written and first performed, both

Shakespeare and his audiences would have been very interested in the

efforts of English and other European settlers to colonize distant lands

around the globe. The Tempest explores the complex and problematic

relationship between the European colonizer and the native colonized peoples

through the relationship between Prospero and Caliban.

In addition to the relationship between the colonizer and colonized, The

Tempest also explores the fears and opportunities that colonization creates.

Exposure to new and different peoples leads to racism and intolerance, as

seen when Sebastian criticizes Alonso for allowing his daughter to marry an

African. Exploration and colonization led directly to slavery and the

conquering of native peoples. For instance, Stephano and Trinculo both

consider capturing Caliban to sell as a curiosity back at home, while

Stephano eventually begins to see himself as a potential king of the island.

At the same time, the expanded territories established by colonization

created new places in which to experiment with alternative societies.

Shakespeare conveys this idea in Gonzalo's musings about the perfect

civilization he would establish if he could acquire a territory of his own.

The character of Caliban dramatizes otherness and exoticism. Trinculo,

upon first seeing Caliban, questions whether he is “a man or a fish?” and

later repeatedly calls him “monster” (Shakespeare 2.2.25, 2.2.31).

Stephano consistently refers to Caliban as “servant monster,” “man-

monster,” and “mooncalf” (3.2.8, 3.2.12, 3.2.23). But even if these

characters emphasize Caliban’s monstrosity, I support Vaughan and

Vaughan’s reading of Caliban as clearly human (10). Prospero states, when

introducing Caliban and setting up his own coming to the island that it “was

not honored with a human shape” except “the son that she [Sycorax,

Caliban’s mother] did litter here”(1.2.281-83). The First Folio version of

the play describes Caliban in the Dramatis Personae as “a saluage and

deformed slaue.” However, the deformity is never specified, and staging

choices are left to the choices made by each production of the play.

Caliban’s otherness clearly has to do with his behavior as much as with his

looks. Prospero declares that despite his own humane treatment of Caliban,

Caliban refuses to behave appropriately. One of his complaints is that

Caliban, “with humane care,” was allowed to live in the cave with Prospero

and Miranda, but subsequently tried to rape her (1.2.346-48). Prospero

implies that gratitude would have been a more appropriate response to

sharing habitation with him and Miranda. Caliban, on the other hand,

laments that learning the language of his oppressors have done him no good,

only taught him to “curse” (1.2.363). In contrast to Prospero, who uses

magic to dominate other characters, Caliban’s curses are ineffective as a

tool. In other words, even if Prospero has made an effort to teach Caliban

the ways of the civilized world, Caliban is unwilling to behave according to

Prospero’s expectations.

Caliban is written as a sympathetic and composite character. As argued by

Deborah Willis, Caliban and his claim to the island is strong enough to

(partly) undermine Prospero as a just ruler (279, 284). Caliban explains to

the audience how “this island’s mine by Sycorax my mother,” a more

convincing claim to the island than Prospero is able to come up with

(1.2.331). He further details how Prospero pretended to “ma[ke] much” of

him, but then promptly enslaved him and now keeps him confined in a rock

when he is not working (1.2.472, 1.2.481-82). In this earnest and

eloquent speech, Caliban appears to have good reasons to complain of his

servitude, which again serve to undermine Prospero’s absolute authority.

Caliban might be partly savage and crude, but he also speaks in iambic

pentameter (like the noble characters of the play), and his side of the

story shows Prospero’s abuse and willingness to use magic and power to get

his own way. Thus, Caliban’s character works against simple stereotypes of

“savage natives” and invites the audience to ponder why, exactly, Prospero

might be justified in ruling over him.

The issues brought up by the character of Caliban also emphasize the

economic concerns of the colonial enterprise. When Prospero and Miranda

first came to the island, we learn, Caliban showed them “all the qualities o’

th’ isle / the fresh springs, brine pits, barren place and fertile” (1.2.337).

He, in other words, has knowledge of the raw materials they needed for

their survival. In addition, Caliban represents labor for Prospero. While the

newcomers to the island refer to Caliban as “monster,” Prospero’s

descriptor of choice is “slave.” When Caliban first enters the stage, he is

repeatedly called “slave,” “my slave,” “poisonous slave” and “most lying

slave,” all in quick succession (1.2.307, 1.2.312, 1.2.319, 1.2.343).

Caliban works for Prospero: fetching wood, tending the fire, and other

“offices that profit [Prospero and Caliban]” (1.2.307). In this way, Caliban

represents both wealth, labor, and survival for Prospero and his daughter.

Other characters also see Caliban in terms of his monetary value. Trinculo

speculates that Caliban would “make a man” in England, i.e. make Trinculo

rich by attracting people who would be willing to pay to see him (2.2.30-

32). Likewise Antonio, Prospero’s brother, states that Caliban is “very

marketable” (5.1.266). They are not interested in Caliban’s qualities as a

person or his potential autonomy, but view him as an object, something they

can make money on. This, of course, mirrors colonial financial concerns.

The geographical location of the island of Prospero’s island is vague. This in

turn has contributed to the longevity of the play: after all, we still deal

with colonialism and post-colonialism, and the issues raised by Prospero and

Caliban have been specific enough to be useful, yet general enough to be

applicable to more modern contexts. We see this for instance in

Mannoni’s Prospero and Caliban: the Psychology of Colonization, where the

psychoanalyst uses the characters from The Tempest to illustrate,

generalize, and problematize the mindsets and effects of colonialism.

In addition to the relevance gained from this geographical ambiguity,

Caliban’s character and thus his colonized condition stays with the audience.

Whereas the spirit Ariel, who has been bound to Prospero throughout the

play, is released by Prospero at the end of the last act, Caliban’s future is

not resolved (5.1.320). Caliban, on the other hand, recognizes that

Prospero is now his master (again) and that he will likely be punished

(5.1.261) and Prospero, in turn, exclaims that “this thing of darkness I /

acknowledge mine” (5.1.275). They are back in the same kind of

relationship they had at the beginning of the play, except Caliban now vows

to “be wise hereafter, / and seek for grace” because he fears the

punishment Prospero can give him (5.1.295). First, this ending is tenuous

because obedience grounded in fear often backfires or leads to unwanted

consequences. Second, Prospero leaves it up to the readers’ imagination

what will happen to Caliban next. Some critics hold that Caliban will get the

island and his liberty back when Prospero returns to Milan (Vaughan and

Vaughan 9). I agree with Willis’ reading of the end where Caliban’s

future is really up in the air: he might be allowed to stay at the island by

himself, but it is equally possible that he has to come with Prospero to

Milan (286). Either way, Caliban’s presence is ongoing and uneasy, even

after the ending of the play.

In conclusion, The Tempest deals with colonialism and power in a nuanced

way. While demonstrating how Caliban is viewed by the colonizer, Prospero,

and the Old World newcomers to the island, the play also portrays him as a

sympathetic and oppressed character. Shakespeare’s combination

of contemporary, topical references to colonialism and natives and the

wider, overarching themes of the long-lasting effect of colonialism and

legitimacy of power, make this play feel relevant also in the 21st century.

After all, just like Caliban stays with us after the curtain goes down, so do

issues related to power and (post-)colonialism.

You might also like

- Jo-Ann Shelton - As The Romans Did - A Sourcebook in Roman Social History-Oxford University Press (1997) PDFDocument505 pagesJo-Ann Shelton - As The Romans Did - A Sourcebook in Roman Social History-Oxford University Press (1997) PDFChilcos Flavian91% (22)

- Racism IN SHAKESPEARE'S THE TEMPESTDocument14 pagesRacism IN SHAKESPEARE'S THE TEMPESTSiddhartho Sankar Roy100% (4)

- Caliban's CharacterDocument1 pageCaliban's CharacterMiss_M90No ratings yet

- UhuruDocument9 pagesUhuruapi-303025168No ratings yet

- The Tempest Within ProsperoDocument7 pagesThe Tempest Within ProsperoElizabeth100% (2)

- The Floyd Family Whole ClothLondon To Georgia in Eight GenerationsDocument158 pagesThe Floyd Family Whole ClothLondon To Georgia in Eight GenerationsMargaret Woodrough100% (2)

- Prospero-Caliban Relationship In: The TempestDocument17 pagesProspero-Caliban Relationship In: The TempestShah RajNo ratings yet

- A Post-Colonial Interpretation of The TempestDocument4 pagesA Post-Colonial Interpretation of The TempestMuHammAD ShArjeeLNo ratings yet

- The Tempest As A Post Colonial PlayDocument16 pagesThe Tempest As A Post Colonial PlayJannatul Nayma MouNo ratings yet

- The Tempest: As A Post-Colonial PlayDocument16 pagesThe Tempest: As A Post-Colonial PlayShah Raj100% (1)

- Postcolonial Reading of William Shakespeare'S: The TempestDocument4 pagesPostcolonial Reading of William Shakespeare'S: The TempestMuHammAD ShArjeeLNo ratings yet

- Caliban 1Document1 pageCaliban 1peopleupcheererNo ratings yet

- Caliban The TempestDocument15 pagesCaliban The TempestSelma HadzicNo ratings yet

- The Tempest-NotesDocument3 pagesThe Tempest-Notesapi-336553511No ratings yet

- Parallels and Contrasts in ShakespeareDocument3 pagesParallels and Contrasts in ShakespeareKingshuk Mondal50% (2)

- Chapter 1 in The Beginning .AbdelghaniDocument3 pagesChapter 1 in The Beginning .Abdelghanizahi100% (1)

- English Literature: The Relationship Between Prospero and Caliban Is That of The Coloniser and The Colonised.'discussDocument3 pagesEnglish Literature: The Relationship Between Prospero and Caliban Is That of The Coloniser and The Colonised.'discusshiral baidNo ratings yet

- ThemesDocument5 pagesThemesXaresh Noor100% (1)

- Tempest As A Postcolonial PlayDocument4 pagesTempest As A Postcolonial PlayMonalisa01No ratings yet

- The TempestDocument2 pagesThe Tempest93fionachangNo ratings yet

- Would Control My Dam's God, Setebos, / and Make A Vassal of Him." (I, Ii, 372-74), But Even When He MeetsDocument6 pagesWould Control My Dam's God, Setebos, / and Make A Vassal of Him." (I, Ii, 372-74), But Even When He MeetsSakshi Sadhana ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- The Tempest Revision 1Document11 pagesThe Tempest Revision 1renell simonNo ratings yet

- Colonisation in The TempestDocument1 pageColonisation in The Tempest62459No ratings yet

- Key Themes - BBCDocument4 pagesKey Themes - BBCremelroseNo ratings yet

- A Reimagining of Shakespeare's "The Tempest" in Toufann.Document17 pagesA Reimagining of Shakespeare's "The Tempest" in Toufann.caitlinhokage08No ratings yet

- CalibanDocument2 pagesCalibanrehan ahmedNo ratings yet

- Theme of The Play "The Tempest"Document4 pagesTheme of The Play "The Tempest"Layba KhalidNo ratings yet

- Sample Post Colonial Reading of The TempestDocument5 pagesSample Post Colonial Reading of The TempestEmerick AubameyangNo ratings yet

- The Difficulty of Distinguishing "Men" From "Monsters"Document4 pagesThe Difficulty of Distinguishing "Men" From "Monsters"Arihant KumarNo ratings yet

- Tempest NotesDocument9 pagesTempest Notesneet2025rudynmNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study Between ShakespearesDocument6 pagesA Comparative Study Between ShakespearesCenwyNo ratings yet

- Attitudes Towards ProsperoDocument2 pagesAttitudes Towards ProsperoMiss_M90No ratings yet

- Imperialism in The TempestDocument3 pagesImperialism in The TempestaayushNo ratings yet

- The Tempest-Plot SummaryDocument4 pagesThe Tempest-Plot SummaryboomalNo ratings yet

- Caliban: Shakespeare's Howling Monster: The TempestDocument3 pagesCaliban: Shakespeare's Howling Monster: The Tempestvirginia fradeNo ratings yet

- AvdicDocument20 pagesAvdicpepper2008No ratings yet

- English Literature Project 2 - Tempest by Scott Vareso DavidDocument13 pagesEnglish Literature Project 2 - Tempest by Scott Vareso DavidSkottayy0% (1)

- Craming Exa EnglishDocument1 pageCraming Exa EnglishEmerick AubameyangNo ratings yet

- The Tempest - Post Colonial ReadingDocument4 pagesThe Tempest - Post Colonial ReadingDhanush NNo ratings yet

- Shadab Jamil Drama Assignment Sem IIDocument2 pagesShadab Jamil Drama Assignment Sem IIShadab JamilNo ratings yet

- End of Year EssayDocument3 pagesEnd of Year EssayAna PecchioNo ratings yet

- English PPT PresentationDocument9 pagesEnglish PPT PresentationVihaan JNo ratings yet

- HFVBBDocument2 pagesHFVBBclashofclans.brothers69No ratings yet

- Analysis of Major CharactersDocument3 pagesAnalysis of Major CharactersMechiet SoniaNo ratings yet

- Tempest NotesDocument4 pagesTempest NotesAfraz AliNo ratings yet

- The Tempest and PowerDocument5 pagesThe Tempest and PowerAnthony Read83% (6)

- Second Paper ShakespeareDocument2 pagesSecond Paper ShakespeareMaria PrietoNo ratings yet

- Tempest VideoDocument4 pagesTempest Videoqs5cj2h49wNo ratings yet

- Throughout Act The Question of Rightful Authority, A MajorDocument14 pagesThroughout Act The Question of Rightful Authority, A Majoryingy0116No ratings yet

- Tempest WordDocument6 pagesTempest WordM vemaiahNo ratings yet

- The TempestDocument3 pagesThe Tempesthassan20572No ratings yet

- Themes TempestDocument3 pagesThemes Tempestapi-375048250% (2)

- Tempest QuestionsDocument2 pagesTempest QuestionslukehyunohNo ratings yet

- Caliban EssayDocument1 pageCaliban EssayknightissavageNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's The Tempest and Post ColonialismDocument13 pagesShakespeare's The Tempest and Post Colonialismchristianpranay83% (6)

- Notes On Shakespeare's The Tempest: Tempestuous ThoughtsDocument4 pagesNotes On Shakespeare's The Tempest: Tempestuous Thoughtsfcrocco100% (3)

- How Does Prospero Establish The Brave NeDocument11 pagesHow Does Prospero Establish The Brave NeIllıllı AMAZING SPIDER MAN IllıllıNo ratings yet

- Tempest EssayDocument19 pagesTempest Essaycedriclamb100% (1)

- The Tempest Revision2Document36 pagesThe Tempest Revision2Kai KokoroNo ratings yet

- The Tempest by William Shakespeare (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandThe Tempest by William Shakespeare (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- Student Camp 2021: Ministry of Education & YouthDocument22 pagesStudent Camp 2021: Ministry of Education & Youthhowelljoshua23No ratings yet

- Ten Times More Ebook - C.J. OrtizDocument13 pagesTen Times More Ebook - C.J. OrtizmeNo ratings yet

- Fire Eater's PDFDocument5 pagesFire Eater's PDFPatrick DuhamelNo ratings yet

- Hunters Sufis Soldiers and Minstrels TheDocument22 pagesHunters Sufis Soldiers and Minstrels TheMohammed GhazalNo ratings yet

- Unit 11 LecturesDocument7 pagesUnit 11 Lecturesthefiasco110No ratings yet

- Closer Union (Attempts at Regional Integration)Document19 pagesCloser Union (Attempts at Regional Integration)jemimaNo ratings yet

- Reconstruction DBQDocument29 pagesReconstruction DBQSarah Chu50% (2)

- ReconstructionDocument56 pagesReconstructionyatada s.No ratings yet

- Dragon 408 PDFDocument46 pagesDragon 408 PDFDanielL'Abbe100% (3)

- Sky's End: By: Elisabeth TrebleDocument10 pagesSky's End: By: Elisabeth TrebleElisabeth TrebleNo ratings yet

- On The Age of Exploration Affecting Philippine HistoryDocument2 pagesOn The Age of Exploration Affecting Philippine Historymonkeyballs12360% (5)

- Luisa Valdez-The Middle Passage EssayDocument5 pagesLuisa Valdez-The Middle Passage EssayLuisa ValdezNo ratings yet

- Noah's SF 181 With Attached DocumentsDocument16 pagesNoah's SF 181 With Attached DocumentsEMPRESS_OM100% (4)

- Creole Voodoo GlossaryDocument14 pagesCreole Voodoo Glossaryadamsmorticia100% (1)

- Athens and Sparta WorksheetDocument1 pageAthens and Sparta WorksheetOlivia ScallyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Section 3 NotesDocument6 pagesChapter 4 Section 3 NotesJaysway 16No ratings yet

- Apush Thesis Statement ExamplesDocument8 pagesApush Thesis Statement Examplesgbwygt8n100% (2)

- Civil Rights Overview: Understandings and QuestionsDocument107 pagesCivil Rights Overview: Understandings and QuestionsPhil JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Capitalist Patriarchy and Socialist FeminismDocument23 pagesCapitalist Patriarchy and Socialist FeminismindrajitNo ratings yet

- Historiography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?Document2 pagesHistoriography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?sofiaNo ratings yet

- Prayers That Break Iron YokesDocument3 pagesPrayers That Break Iron YokesDivino Henrique SantanaNo ratings yet

- Brazil Geography and History PresentationDocument35 pagesBrazil Geography and History PresentationJoshua Miranda100% (1)

- Author's Note From Conform by Glenn BeckDocument6 pagesAuthor's Note From Conform by Glenn BeckSimon and SchusterNo ratings yet

- Marche SlaveDocument2 pagesMarche SlaveLilika94No ratings yet

- 240 Hedwig Dohm Women's Vote 58Document18 pages240 Hedwig Dohm Women's Vote 58Beatriz VieiraNo ratings yet

- Venice: Portugal's Eastern Trade: 1508-1595Document5 pagesVenice: Portugal's Eastern Trade: 1508-1595Tay MonNo ratings yet

- Something RandomDocument3 pagesSomething RandomJames100% (1)

- Slavery WebquestDocument4 pagesSlavery Webquestapi-244459124No ratings yet