Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Session 7: Sisir Debnath Indian School of Business

Session 7: Sisir Debnath Indian School of Business

Uploaded by

Sakshi AgarwalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Session 7: Sisir Debnath Indian School of Business

Session 7: Sisir Debnath Indian School of Business

Uploaded by

Sakshi AgarwalCopyright:

Available Formats

Session 7

Sisir Debnath

Indian School of Business

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 1

Today

6. Public Goods and Externalities (Async)

7. Individual Behavior under Uncertainty

► Utility and expected utility

► Risk aversion

► Insurance

► Adverse selection

► Signaling

► Moral Hazard

7. Market Competition

8. Simultaneous Games

9. Sequential and Repeated Games

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 4

Individual Behavior

• Individuals are the basic unit of decision-

making in firms and in the economy

• Individuals (students, consumers,

shareholders, managers) are faced with choices

everyday

• Uncertainty and lack of information are

common features of these choices

• The objective of today’s class is to analyze

uncertainty and missing information in

systematic ways

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 5

Utility

• According to traditional economists, our

behavior is motivated by rational self interest

• Two things determine choices:

► The pleasure of consumption

► The price of the product

• Goods and services increase utility, though

Bads decrease utility

• Financial payoffs are not the only

determinants of utility

• Individuals can gain utility from the act of

work, giving, happiness of others, relaxation

etc.

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 7

Total Utility and Marginal Utility

• Utility = Satisfaction

• Total utility is the total satisfaction one gets

from consuming a product

• Marginal utility is the satisfaction you get

from the consumption of one additional unit of

the product

• The marginal utility of a product decreases as

you consume more of it

• Although the shape of the utility function for

wealth may vary depending on individual

preferences

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 8

Lottery

• A lottery is any event with an uncertain

outcome

• Example:

► Payoff from a equity share for an investor

► Outcome of a roulette wheel for a gambler

► Amount of rainfall for a farmer

• If you are to choose between

► Rs. 1 million for sure

► 25% chance of winning Rs. 4 million

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 10

Probability

• An event’s relative frequency in a large number of

trials is the probability of the event.

• Probability of event i ( pi ) =

► N: Large number of trials

► ni : Number of times event i occurs in those trials

• Probabilities cannot be less than zero or greater

than one

• Given a list of mutually exclusive, collectively

exhaustive events, the sum of the probabilities of the

events must be equal to one

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 11

Expected Value

• When dealing with uncertain events, we need

a way to characterize the level of risk that you

face.

• Expected Value refers to the most likely

outcome (i.e. the average)

N

E ( x) piVi

i 1

Probability of event i Payout of event i

• Note: if all the probabilities are equal, then

the expected value is the average.

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 12

Expected Value: Example

• You are offered the following choice

• .01% chance of winning Baisakhi Bumper

(Rs.1 Million)

• 0.05% chance of winning Rakhi Bumper

(Rs.5 Million)

• E(Baisakhi Bumper) = ?

• E(Rakhi Bumper) =?

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 13

Risk Averse Managers

• Between two lotteries that offer equal

expected wealth, a risk averse manager prefers

the one with less risk

• Suppose that a manager has to choose

between:

► 50% chance of earning Rs.200 (B), 50%

chance of earning Rs.100 (A)

► Rs.150 for Sure

• Expected value of the lottery, E(L)?

U(E(L)) = U(150) > ½ ×U(200) + ½ ×U(100) = E(U(L))

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 14

Risk Averse Managers

Expected

value of the

lottery: E(L)

U(B=200)

Utility from

U(E(L)=150)

the Expected

value of the

E(U(L)) lottery:

U(E(L))

Expected

U(A=100)

Utility of the

Lottery:

E(U(L))

A (100) E(L) = 150 B (200)

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 15

Risk Neutral Manager

• A risk neutral individual is indifferent

between a lottery with a more certain outcome

and one with a less certain outcome, as long as

each lottery offers equal expected wealth.

• Suppose that a manager has to choose

between:

► 50% chance of earning Rs.200 (B), 50%

chance of earning Rs.100 (A)

► Rs.150 for Sure

U(E(L)) = U(150) = ½ ×U(200) + ½ ×U(100) = E(U(L))

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 16

Risk Neutral Manager

Expected value

of the lottery:

E(L)

U(B=200)

Utility from

the Expected

value of the

lottery: U(E(L))

U(E(L)=150)

=

E(U(L))

Expected

Utility of the

Lottery:

E(U(L))

U(A=100)

A(100) E(L) = 150 B (200)

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 17

Risk Loving Managers

• Between two lotteries that offer equal

expected wealth, a risk lover manager prefers

the one with larger spread

• Suppose that a manager has to choose

between:

► 50% chance of earning Rs.200 (B), 50%

chance of earning Rs.100 (A)

► Rs.150 for Sure

U(E(L)) = U(150) < ½ ×U(200) + ½ ×U(100) = E(U(L))

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 18

Risk Loving Preferences

Expected

value of the

lottery: E(L)

U(B=200)

Utility from

the Expected

value of the

lottery:

U(E(L))

E(U(L))

Expected

U(E(L)=150) Utility of the

Lottery:

E(U(L))

U(A=100)

A (100) E(L) = 150 B (200)

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 19

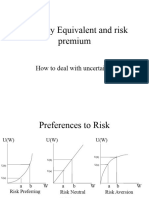

Preferences Towards Risk

Type Condition Example

Risk Loving U ' ' (I ) 0 U (I ) I 2

Risk Neutral U ' ' (I ) 0 U (I ) 2I

Risk Averse U ' ' (I ) 0 U (I ) I

• Suppose you have to choose between:

► Rs.1 million for sure

► 25% chance of winning Rs. 5 million

• What is the expected value of the lottery?

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 20

Measures of Risk

• Managers often rely on standard deviation as

a measure of risk

• Standard Deviation is the square root of the

expected value of squared differences from the

mean

N

p V E ( x)

2

SD( x) i i

i 1

Probability of event i Squared difference between

the payout of each event

and the expected value

• What is the SD of the lottery?

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 21

Certainty Equivalence and the

Market for Insurance

• The certainty equivalent is the guaranteed

payoff at which a person is indifferent between

certain wealth and a lottery with uncertain

wealth.

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 22

Risk Averse Expected

value of the

lottery: E(L)

U(B)

Expected

Utility of the

lottery:

E(U(L)) E(U(L))

Certainty

Equivalent

U(A) of the

lottery:

CE(L)

A CE(L) E(L) B

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 23

Market for Insurance

• Seinfeld Insurance Company is risk neutral

and is willing to buy Kramer’s bond, i.e., take

on Kramer's risk

• What is the maximum Seinfeld will pay for

the bond?

• What is the minimum Kramer will accept for

the bond?

• The difference is the risk premium

• Works only for risk averse preferences

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 27

Adverse Selection

• Buyer and seller have different information

• Market breakdown; even though sellers are

willing to sell goods and buyers willing to

purchase goods at the same price

• The reason is hidden information.

• The mechanism is adverse selection.

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 29

The Lemons Problem

• Two types of cars: Peaches and Lemons

• Both look the same, but Peaches work and

Lemons don't

• Peaches are a fraction 0.6 of the market

• Lemons are a fraction 0.4 of the market

• Buyers cannot distinguish between the two,

but sellers can.

• Peaches are worth Rs. 2 lakh to buyers

• Lemons are worth Rs. 1 lakh to buyers

• Market clearing price for new cars should be

(0.6 × 2) + (0.4 × 1) = Rs. 1.6 lakh

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 32

The Lemons Problem

• But the market will not clear at Rs. 1.6 lakh!

• Recall that buyers cannot distinguish between

Lemons and Peaches

• Sellers know which car is which

• At Rs. 1.6 lakh, sellers will gladly sell Lemons,

but not Peaches

• Buyers know that the only cars offered are

Lemons

• Market clearing price will be Rs. 1 lakh

• Only Lemons are sold, all Peaches are unsold

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 33

Car Insurance

• Asymmetric information case

• Insurer cannot distinguish between High and

Low risk drivers

• Average premium is 50

• High risk drivers will buy insurance at this

price, but Low risk drivers will not

• Since only High risk drivers will buy

insurance, insurance premium increases to 75

• Asymmetric information implies no insurance

for Low risk drivers

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 38

Signalling

• Overcoming Adverse Selection

• Definition: A signal is a costly action that

sellers undertake to convey credible

information about a product's quality.

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 41

Warranties as Signals

• Adverse Selection in the Product Market

• Experience goods: Goods whose quality can be

evaluated only after they have been consumed

• If quality cannot be discerned by consumers

then there would be a single market

• Incentive for high-quality producers to

separate their product from others and increase

buyer’s willingness to pay

• Product warranties act as a separating

mechanism

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 46

Warranties as Signals

• Notation:

High Quality Low Quality

Willingness to pay PH PL

Production cost CH CL

• Annual warrantee cost

• Number of years warrantee offered:

• is chosen by managers

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 47

Warranties as Signals (Case 1)

• Consumers believe that any good with a warranty is a

high-quality good

• Consumers will pay only PL for any product that does

not have warrantee

• Profit from high quality good with warranty

• Profit from high quality good without warranty

• High quality producer will issue a warranty if

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 48

Warranties as Signals (Case 1)

• Profit from low quality good with warranty

• Profit from low quality good without warranty

• Low quality producer will not issue a warranty if

• Credible warranty requires

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 49

Warranties as Signals (Case 2)

• Consumers believe that goods with longer

warranties are of higher quality

• Longest warranty low quality producer can afford

to offer

• Longest warranty high quality producer can

afford to offer

• Since WL > WH → YH > YL

• High quality product will have warranty

YH = YL + 1

• Low quality product will not have warranty

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 50

The Principal-Agent Relationship

• The Principal owns resources

• The Agent is hired by the principal and given

stewardship over resources

• Contract imperfectly describes future

contingencies

• Post-contractual behaviour of the agent must

be either monitored or properly motivated

• Incentive problem exists within firms as

owners and employers have fundamentally

different objective.

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 52

Moral Hazard

• Market breakdown

• The principal cannot observe, verify or enforce

all actions of the agent

• Agents change actions to suit their own

welfare, rather than principal's welfare

• Impossible to write contracts

• The reason is hidden action

• The mechanism is moral hazard

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 53

Takeaways from this Session

• Analysis of individual choice and decisions

► The objective of an individual is to maximize

utility

► But, uncertainty and lack of information

complicate decision-making

► Most people in most situations are risk averse

and try to reduce uncertainty

• Insurance can mitigate uncertainty

► But, insurance markets suffer from adverse

selection and moral hazard

• Signaling is one way to overcome adverse

selection

• Pay-for-performance is one way to overcome

moral hazard

Sisir Debnath, Managerial Economics, Indian School of Business 56

You might also like

- QF2104 Tutorial - Assignment 5 (Discussion Q4 II Rephased)Document3 pagesQF2104 Tutorial - Assignment 5 (Discussion Q4 II Rephased)igndunnoNo ratings yet

- Utility Theory: CS 2710 Foundations of AI Lecture 20-ADocument7 pagesUtility Theory: CS 2710 Foundations of AI Lecture 20-ASarwar SonsNo ratings yet

- Risk Averse Vs Risk Neutral InvestorsDocument9 pagesRisk Averse Vs Risk Neutral InvestorsYinghong chenNo ratings yet

- Ecmc49 4Document37 pagesEcmc49 4Xin SunNo ratings yet

- Solutions - Utility v2Document3 pagesSolutions - Utility v2ΩmegaNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure Under Asymmetric Information: Problem Sets. 4 Part SeriesDocument8 pagesCapital Structure Under Asymmetric Information: Problem Sets. 4 Part SeriesVedBakshi100% (1)

- The Tools of Portfolio AnalysisDocument12 pagesThe Tools of Portfolio AnalysisTheYellowKingNo ratings yet

- Risk Theory: Professor Peter Cramton Economics 300Document17 pagesRisk Theory: Professor Peter Cramton Economics 300Henmark Arisga AbejuelaNo ratings yet

- 41 MeasuringRiskAversionDocument8 pages41 MeasuringRiskAversionjared demissieNo ratings yet

- Prospect Theory & Reference-Dependent Preferences: AE6307 Behavioral Economics For Policy AnalysisDocument97 pagesProspect Theory & Reference-Dependent Preferences: AE6307 Behavioral Economics For Policy AnalysisHeidy JNUNo ratings yet

- Msqe Peb 2020Document8 pagesMsqe Peb 2020Siddhant MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Examination Advanced Microeconomics (ECH 32306) : InstructionsDocument2 pagesExamination Advanced Microeconomics (ECH 32306) : InstructionsHector CupperNo ratings yet

- Book ChapterDocument29 pagesBook ChapterVinay DuttaNo ratings yet

- ECON236 4.uncertaintyDocument43 pagesECON236 4.uncertaintyMarie StéphanNo ratings yet

- HW Ims555Document2 pagesHW Ims555Muhammad Afandi Bin OsmanNo ratings yet

- W2. Decision Tree PDFDocument32 pagesW2. Decision Tree PDFHENRIKUS HARRY UTOMONo ratings yet

- FIN 435 - Exam 2 SlidesDocument157 pagesFIN 435 - Exam 2 SlidesMd. Mehedi HasanNo ratings yet

- Math ReviewDocument29 pagesMath ReviewSaiful AmriNo ratings yet

- Session 6 - 7Document16 pagesSession 6 - 7V SURENDAR NAIKNo ratings yet

- Additional Exercises - Risk and Risk AversionDocument2 pagesAdditional Exercises - Risk and Risk AversionshalommothapoNo ratings yet

- Eco501 Homework Risk Solutions Summer2020Document3 pagesEco501 Homework Risk Solutions Summer2020maruf91No ratings yet

- Week 07Document11 pagesWeek 07nsnnsNo ratings yet

- Lec1 pt1Document25 pagesLec1 pt1feacasNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Finance - Tutorial 2 With SolutionsDocument7 pagesBehavioral Finance - Tutorial 2 With Solutionsimran_omiNo ratings yet

- Assign 1Document3 pagesAssign 1Hrishikesh KasatNo ratings yet

- Mva CapmDocument27 pagesMva Capmjc820809No ratings yet

- ProblemSet1 SolDocument13 pagesProblemSet1 SolAlejandro álvarez MartínezNo ratings yet

- Sample Questions - MSC DelhiDocument18 pagesSample Questions - MSC DelhiPriyanath PaulNo ratings yet

- Lecture 8 - Risk AversionDocument7 pagesLecture 8 - Risk AversionNikanon AvaNo ratings yet

- Capital Asset Pricing ModelDocument24 pagesCapital Asset Pricing ModelGouravAgarwalNo ratings yet

- Topic 14 Uncertainty PDocument50 pagesTopic 14 Uncertainty Provertgnow1No ratings yet

- Utility and Risk Aversion: (Asset Pricing and Portfolio Theory)Document45 pagesUtility and Risk Aversion: (Asset Pricing and Portfolio Theory)Lena PhanNo ratings yet

- Risk 2Document33 pagesRisk 2Alba María Carreño GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Corporate Finance I - Unit 1Document46 pagesMathematical Corporate Finance I - Unit 1ernestessel95No ratings yet

- Economics 302Document13 pagesEconomics 302Rana AhmedNo ratings yet

- Expected Utility Theory: Behavioral Economics Patrick McalvanahDocument28 pagesExpected Utility Theory: Behavioral Economics Patrick McalvanahKübra ÇakırNo ratings yet

- Risk Aversion and Utility TheoryDocument47 pagesRisk Aversion and Utility TheoryanirudhjayNo ratings yet

- Risk Premium 3rd LectDocument9 pagesRisk Premium 3rd LectRishu PanditNo ratings yet

- Return, Risk and The Security Market LineDocument25 pagesReturn, Risk and The Security Market Linewww_peru9788No ratings yet

- Chapter 0.2 LESSONDocument13 pagesChapter 0.2 LESSONpohpaymmNo ratings yet

- Exercises Week 7 (Text Only)Document3 pagesExercises Week 7 (Text Only)Giorgia FantiniNo ratings yet

- I13 - MGEC - Assignment 1 SubmissionDocument7 pagesI13 - MGEC - Assignment 1 Submissionshalin.bhansali242No ratings yet

- 2assetallocation (9) 1vmodr11cDocument61 pages2assetallocation (9) 1vmodr11cGabriel PodolskyNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document3 pagesAssignment 2Rahul UdainiaNo ratings yet

- Saikeerthi - GT - Lecture 2Document4 pagesSaikeerthi - GT - Lecture 220saikeerthiNo ratings yet

- ECON 312 Microeconomics Uncertainty and Risks 2021Document48 pagesECON 312 Microeconomics Uncertainty and Risks 2021Mary AmoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6Document40 pagesLecture 6Vishal kumar SawNo ratings yet

- 2019NOVMSDocument9 pages2019NOVMSgirdozagneNo ratings yet

- Demand Analysis Managerial EconomicsDocument12 pagesDemand Analysis Managerial EconomicsAkshay ShindeNo ratings yet

- Infinite Horizon ModelDocument9 pagesInfinite Horizon ModelDynamic ClothesNo ratings yet

- AF Practice Final ExamDocument4 pagesAF Practice Final ExamrtchuidjangnanaNo ratings yet

- AF PS1 2014 15 SolutionDocument9 pagesAF PS1 2014 15 SolutionrtchuidjangnanaNo ratings yet

- FINECO - 03 - Investments Under UncertaintyDocument25 pagesFINECO - 03 - Investments Under UncertaintyQuyen Thanh NguyenNo ratings yet

- MicroEcon Assignment - 2 - KeyDocument4 pagesMicroEcon Assignment - 2 - KeyOrochi ScorpionNo ratings yet

- Exercises For Week 6: SharecroppingDocument3 pagesExercises For Week 6: SharecroppingPrachi TamtaNo ratings yet

- Reading 8: Probability ConceptsDocument31 pagesReading 8: Probability ConceptsAlex PaulNo ratings yet

- Bab 3 Probabilitas DiskritDocument41 pagesBab 3 Probabilitas DiskritYuniNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance Formulas: A Simple IntroductionFrom EverandCorporate Finance Formulas: A Simple IntroductionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Piliart Nuts Rizal Street, Sagpon, Daraga, AlbayDocument5 pagesPiliart Nuts Rizal Street, Sagpon, Daraga, AlbayHazel Mae HerreraNo ratings yet

- Normal and Inferior GoodsDocument8 pagesNormal and Inferior GoodsVandana DubeyNo ratings yet

- Page 0009Document1 pagePage 0009Matteo BaldassariNo ratings yet

- Catalogue Golden Dragon MelamineDocument51 pagesCatalogue Golden Dragon MelamineYetty SyamsiyatiNo ratings yet

- Week 8 Media and The AudienceDocument3 pagesWeek 8 Media and The AudienceADMATEZA UNGGUINo ratings yet

- QCBS RFP For Gweir SHPP PMC PDFDocument125 pagesQCBS RFP For Gweir SHPP PMC PDFjayant pathakNo ratings yet

- Sample Requistion For Jay Vijay LLP Godrej Site DATED 23 JAN 2024Document4 pagesSample Requistion For Jay Vijay LLP Godrej Site DATED 23 JAN 2024kiranmisale7No ratings yet

- Vvneq1m5ymzryny1nuj2swrlwef0dz09 InvoiceDocument2 pagesVvneq1m5ymzryny1nuj2swrlwef0dz09 InvoiceTYCS35 SIDDHESH PENDURKARNo ratings yet

- Journal Entries and Ledger Accounts - FinalDocument6 pagesJournal Entries and Ledger Accounts - FinalMukul SinhaNo ratings yet

- Poverty and The Social ProblemsDocument4 pagesPoverty and The Social ProblemsBonggot LadyAntonietteNo ratings yet

- Solution Practice 1 Share CapitalDocument2 pagesSolution Practice 1 Share CapitalMya Hmuu KhinNo ratings yet

- Mindstone-Creating Change That Matters - HyperRevelanceDocument9 pagesMindstone-Creating Change That Matters - HyperRevelanceMoksh SharmaNo ratings yet

- P3W OVERLAND TOUR. Alya Tri LestariDocument10 pagesP3W OVERLAND TOUR. Alya Tri LestariGlittersparklesNo ratings yet

- Activity Based Costing - Chapter 8Document52 pagesActivity Based Costing - Chapter 8Qalb e AliNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument8 pages1 PBLaurensia Karin HaryadmoNo ratings yet

- P5 Math Diagnostic Test (Word Problem) (Student Copy)Document7 pagesP5 Math Diagnostic Test (Word Problem) (Student Copy)Aaron HeeNo ratings yet

- Gratuity CalculationDocument4 pagesGratuity CalculationmeetushekhawatNo ratings yet

- CHB Back-Up ComputationDocument36 pagesCHB Back-Up Computationkhim tugasNo ratings yet

- SFMDocument2 pagesSFMBhuvana GanesanNo ratings yet

- 2019 List of Govt ITIDocument41 pages2019 List of Govt ITISunny DuggalNo ratings yet

- RSP Solar Case StudyDocument3 pagesRSP Solar Case StudyBhakti Anand100% (1)

- Sas Certified Accounting Technician Level 1 Module 4Document10 pagesSas Certified Accounting Technician Level 1 Module 4Plame GaseroNo ratings yet

- UBS Invoice FormatDocument14 pagesUBS Invoice FormatAzrul AfiqNo ratings yet

- Mann Whitney U TestDocument19 pagesMann Whitney U TestANGELO JOSEPH CASTILLONo ratings yet

- Detail Syllabus - Elective StatisticsDocument2 pagesDetail Syllabus - Elective StatisticsSut MouNo ratings yet

- Strategy and Business Decision Making (University of Greenwich)Document32 pagesStrategy and Business Decision Making (University of Greenwich)sdrakopoulos323No ratings yet

- CSE Catalog - IndiaDocument67 pagesCSE Catalog - IndiaDheeraj SivadasNo ratings yet

- SAP MM PurchaseDocument56 pagesSAP MM PurchasesagarthegameNo ratings yet

- Brick Cladding To Steel Framed BuildingsDocument130 pagesBrick Cladding To Steel Framed BuildingsRonnie SmithNo ratings yet

- ECON 222-C SyllabusDocument7 pagesECON 222-C SyllabusAlexis R. CamargoNo ratings yet