Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Redemptive Education 3

Redemptive Education 3

Uploaded by

kasserian.sealy4066Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Toki Pona The Language of GoodDocument158 pagesToki Pona The Language of GoodAJ Ajson86% (7)

- Elliott, Kevin Christopher - A Tapestry of Values - An Introduction To Values in Science-Oxford University Press (2017)Document225 pagesElliott, Kevin Christopher - A Tapestry of Values - An Introduction To Values in Science-Oxford University Press (2017)Juan Jacobo Ibarra SantacruzNo ratings yet

- ECE Board Exam Room Assignment Manila CompleteDocument99 pagesECE Board Exam Room Assignment Manila CompleteTheSummitExpressNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Education A Beginners GuideDocument51 pagesPhilosophy of Education A Beginners GuideSacha CherringtonNo ratings yet

- DISS - Q1 - Mod1 - Social Sciences To A Better WorldDocument18 pagesDISS - Q1 - Mod1 - Social Sciences To A Better Worldapol92% (13)

- AlexWorshipSongbook 2-8-13 PDFDocument204 pagesAlexWorshipSongbook 2-8-13 PDFJose Ignacio TorrealbaNo ratings yet

- Bill Bright - A Life Lived WellDocument16 pagesBill Bright - A Life Lived WellIvan Dias100% (1)

- 32 AcceptNoSubstitutesDocument14 pages32 AcceptNoSubstitutesorarickNo ratings yet

- Introduction To World Religion and Belief Systems: Ms. Niña A. Sampaga Subject TeacherDocument65 pagesIntroduction To World Religion and Belief Systems: Ms. Niña A. Sampaga Subject Teacherniña sampagaNo ratings yet

- 11 HUMSS IWRBS CH 1 Lesson 1Document45 pages11 HUMSS IWRBS CH 1 Lesson 1Lc CacaoNo ratings yet

- The CispDocument40 pagesThe CispPerry FranciscoNo ratings yet

- IWRBS Module #2 Religion - Blessing and CurseDocument23 pagesIWRBS Module #2 Religion - Blessing and CurseLuigi ChristianNo ratings yet

- 6.-Appreciating-the-Roots-of-the-Gospel-of-Jesus-intro-lecture 2Document12 pages6.-Appreciating-the-Roots-of-the-Gospel-of-Jesus-intro-lecture 2Ecal, Karyl Rose M.100% (1)

- Developing A Whole PersonDocument27 pagesDeveloping A Whole PersonEnRile TaguRoNo ratings yet

- Synergistic Collaborations: Pastoral Care and Church Social WorkFrom EverandSynergistic Collaborations: Pastoral Care and Church Social WorkNo ratings yet

- DLL in MarxismDocument8 pagesDLL in MarxismJefferson DimayugoNo ratings yet

- Institutionalism 123Document9 pagesInstitutionalism 123Kenneth Carl AyusteNo ratings yet

- RAWS2019 - Week3 Properties of A Well-Written TextDocument3 pagesRAWS2019 - Week3 Properties of A Well-Written TextSheryl Santos-VerdaderoNo ratings yet

- The Creation Myth of The Rig VedaDocument15 pagesThe Creation Myth of The Rig VedaOliverNo ratings yet

- Redemptive Education 1Document18 pagesRedemptive Education 1kasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- Redemptive Education 2Document17 pagesRedemptive Education 2kasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- Assignment No1Document18 pagesAssignment No1TOP TEN 10No ratings yet

- Introduction To World Religion and Beliefs System: Calasanz de Davao Academy, IncDocument10 pagesIntroduction To World Religion and Beliefs System: Calasanz de Davao Academy, IncJuanmiguel Ocampo Dion SchpNo ratings yet

- Cobern (1996) : (Worldview Theory and Conceptual Change in Science Education)Document32 pagesCobern (1996) : (Worldview Theory and Conceptual Change in Science Education)Eduardo Andres50% (2)

- Major Foundations of CurriculumDocument3 pagesMajor Foundations of CurriculumSherah Maye78% (9)

- Chapter 5 - Perennialism - Social Foundations of K-12 EducationDocument9 pagesChapter 5 - Perennialism - Social Foundations of K-12 Educationsuriasabir6No ratings yet

- Module 2.philosophyDocument22 pagesModule 2.philosophyMC CheeNo ratings yet

- 1 The Teacher and The Community 3Document46 pages1 The Teacher and The Community 3Angelika Joy AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- Module 2.philo - PsychDocument31 pagesModule 2.philo - PsychAlbert Yazon100% (1)

- EdD - Educ .Mngt. Focus - Qustions - Final KDVDocument56 pagesEdD - Educ .Mngt. Focus - Qustions - Final KDVKristine VallejoNo ratings yet

- Assignmen 8609 IrshanDocument17 pagesAssignmen 8609 IrshanSufyan KhanNo ratings yet

- EdD - Educ .Mngt. Focus - Qustions - Final KDVDocument55 pagesEdD - Educ .Mngt. Focus - Qustions - Final KDVKristine VallejoNo ratings yet

- Final Answer .... Doctorate NewDocument87 pagesFinal Answer .... Doctorate NewKristine VallejoNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Module 1Document15 pagesPhilosophy Module 1Carmela CarmelaNo ratings yet

- Manzar 8609Document13 pagesManzar 8609Muhammad zeeshanNo ratings yet

- Student Version Q1 Introduction of The Philosophy of The Human Person LatestDocument34 pagesStudent Version Q1 Introduction of The Philosophy of The Human Person LatestLei-anne Ballesteros100% (1)

- Trevor Curnow (Auth.), Michel Ferrari, Georges Potworowski (Eds.) - Teaching For Wisdom - Cross-Cultural Perspectives On Fostering Wisdom (2009, Springer Netherlands)Document237 pagesTrevor Curnow (Auth.), Michel Ferrari, Georges Potworowski (Eds.) - Teaching For Wisdom - Cross-Cultural Perspectives On Fostering Wisdom (2009, Springer Netherlands)pleasantsong100% (3)

- Ed.d Major in Educational Management - Final Answer - Kristine VallejoDocument153 pagesEd.d Major in Educational Management - Final Answer - Kristine VallejoKristine VallejoNo ratings yet

- What Is Philosophy of EducationDocument97 pagesWhat Is Philosophy of EducationRyan San LuisNo ratings yet

- EdD-Educ - Mngt-Focus-Questions - Final AnswerDocument49 pagesEdD-Educ - Mngt-Focus-Questions - Final AnswerKristine VallejoNo ratings yet

- Philosphy of EducationDocument10 pagesPhilosphy of EducationSAIF K.Q100% (1)

- Educational PhilosophyDocument21 pagesEducational PhilosophyUzma Siddiqui100% (1)

- Ferra Makalah Middle Age or Medieval PhilosophyDocument8 pagesFerra Makalah Middle Age or Medieval PhilosophyKano LiquidNo ratings yet

- 8609 1 SeeratDocument16 pages8609 1 SeeratHameed KhanNo ratings yet

- Science and TechDocument53 pagesScience and TechcherylhzyNo ratings yet

- PHILOSOPHY-WEEK-1-8 AnswerDocument20 pagesPHILOSOPHY-WEEK-1-8 AnswerBilly Joe Tan100% (1)

- INTRO-TO-PHILO - Q1-Week-1-And-2Document19 pagesINTRO-TO-PHILO - Q1-Week-1-And-2Mikaela Sai ReynesNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Introduction To Philosophy-Roland ApareceDocument5 pagesSyllabus Introduction To Philosophy-Roland ApareceRoland ApareceNo ratings yet

- CDN Ed Developmental Psychology Childhood and Adolescence 4th Edition Shaffer Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesCDN Ed Developmental Psychology Childhood and Adolescence 4th Edition Shaffer Solutions ManualMichaelMeyerfisp100% (57)

- Jcs 1986spring MacdonaldDocument11 pagesJcs 1986spring MacdonaldKhana ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- Modern Philosophy of Education - JoycepabloDocument38 pagesModern Philosophy of Education - JoycepabloJoyz Tejano100% (1)

- bc200401705 ASSIGNMENT 601Document14 pagesbc200401705 ASSIGNMENT 601haleel rehisNo ratings yet

- A New Program For The Philosophy of ScienceDocument5 pagesA New Program For The Philosophy of ScienceJmanuelRuceNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Social Sciences and PhilosphyDocument24 pagesModule 1 Social Sciences and PhilosphychristianpaulbromaNo ratings yet

- Living Issues in Philosophy An Introductory Textbook OCRDocument450 pagesLiving Issues in Philosophy An Introductory Textbook OCRrujukan100% (1)

- 8609 1Document16 pages8609 1anees kakarNo ratings yet

- Semester: Autumn, 2021: Assignment No. 1 Q.1 Explain The Different Branches of PhilosophyDocument16 pagesSemester: Autumn, 2021: Assignment No. 1 Q.1 Explain The Different Branches of Philosophygulzar ahmadNo ratings yet

- Mam Joan 1Document4 pagesMam Joan 1abba may dennisNo ratings yet

- Major Foundations of CurriculumDocument3 pagesMajor Foundations of CurriculumGela LaceronaNo ratings yet

- 8609 01Document14 pages8609 01شکیل احمدNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesCerelina MestiolaNo ratings yet

- Running Records RevisitedDocument7 pagesRunning Records Revisitedkasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- Classroom Obs Toolkit FINAL - Nov 2019Document94 pagesClassroom Obs Toolkit FINAL - Nov 2019kasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- Redemptive Education 2Document17 pagesRedemptive Education 2kasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- Redemptive Education 1Document18 pagesRedemptive Education 1kasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- AU EDTE 175 Philosophy of Adventist Education Summer 2019Document8 pagesAU EDTE 175 Philosophy of Adventist Education Summer 2019kasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- 6 Curriculum Guides Social Studies2Document89 pages6 Curriculum Guides Social Studies2kasserian.sealy4066No ratings yet

- CFC Financial StewardshipDocument4 pagesCFC Financial StewardshipChryss Merry75% (4)

- The Decapitation Ritual and The AncientDocument12 pagesThe Decapitation Ritual and The AncientB'alam DavidNo ratings yet

- Common Recruitment Process For RRBs (Ibps-RRBs-XII) For Recruitment of Group - A - Officers (Scale-I)Document5 pagesCommon Recruitment Process For RRBs (Ibps-RRBs-XII) For Recruitment of Group - A - Officers (Scale-I)Karan RoyNo ratings yet

- Pranic EnergyDocument4 pagesPranic EnergyHenry SimNo ratings yet

- Get Reign of The Seven Spellblades Vol 7 1st Edition Bokuto Uno and Ruria Miyuki PDF Full ChapterDocument24 pagesGet Reign of The Seven Spellblades Vol 7 1st Edition Bokuto Uno and Ruria Miyuki PDF Full Chapterglxfaggi100% (8)

- Philippine Literature (Spanish Period)Document57 pagesPhilippine Literature (Spanish Period)Zelskie CastleNo ratings yet

- Peeling The Orange An Intertextual Reading of Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit (Xiaowei Chen)Document52 pagesPeeling The Orange An Intertextual Reading of Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit (Xiaowei Chen)Vicky BahlNo ratings yet

- Maran Vidya in Shabar TantraDocument9 pagesMaran Vidya in Shabar TantraSayan BiswasNo ratings yet

- English Kindness To ParentsDocument77 pagesEnglish Kindness To ParentsMelissa WilderNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 - ExtractDocument9 pagesChapter 11 - ExtractESVILDA CELINA DIONICIO RAMOSNo ratings yet

- Kece BDocument8 pagesKece BMogili sivaNo ratings yet

- E. Two Prophetic Oracles (1:7-8) : BibliographyDocument29 pagesE. Two Prophetic Oracles (1:7-8) : BibliographyTeodomiro CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Fedotov, Russia and FreedomDocument25 pagesFedotov, Russia and Freedompunktlich100% (1)

- G671 StudiesDocument11 pagesG671 StudiesVictoria SmithNo ratings yet

- Aspects of DostoievskyDocument27 pagesAspects of DostoievskylalsNo ratings yet

- Spanish Political Remapping 2Document51 pagesSpanish Political Remapping 2XAVIER DOMINGONo ratings yet

- Alexander Pope Was Born in London inDocument29 pagesAlexander Pope Was Born in London innaeem rasheedNo ratings yet

- Rite For The Opening Salutations at The Grotto of Our Lady of The PoorDocument17 pagesRite For The Opening Salutations at The Grotto of Our Lady of The PoorMark Anthony MuyaNo ratings yet

- Pengembangan Lembar Kegiatan Siswa Berbasis Keterampilan Proses Sains Untuk Sma Materi Sistem Reproduksi ManusiaDocument9 pagesPengembangan Lembar Kegiatan Siswa Berbasis Keterampilan Proses Sains Untuk Sma Materi Sistem Reproduksi ManusiaAnnisa RahmiNo ratings yet

- A Conversation With Professor B. N. PatnaikDocument7 pagesA Conversation With Professor B. N. PatnaikSridhar RamanNo ratings yet

- Full Download Test-Bank-For-Human-Geography-6th-0321775856-9780321775856 PDF Full ChapterDocument34 pagesFull Download Test-Bank-For-Human-Geography-6th-0321775856-9780321775856 PDF Full Chapterhoy.guzzler67fzc100% (21)

- Part of Bhagavatipadyapushpa - Njalistotra As Mahishasuramardini StotraDocument8 pagesPart of Bhagavatipadyapushpa - Njalistotra As Mahishasuramardini Stotravsrikala68No ratings yet

- The ASATRUFin Cpya 8 REBTACGRY3 A1 atDocument531 pagesThe ASATRUFin Cpya 8 REBTACGRY3 A1 atREBECCATACOSAGRAY,CALIFORNIANo ratings yet

- A Dispensational TheologyDocument630 pagesA Dispensational Theologydoctorbush75% (4)

- The Way of Love - Overflow From A Sufi HeartDocument69 pagesThe Way of Love - Overflow From A Sufi HeartTaoshobuddha100% (1)

- O Come o Come EmmauelDocument2 pagesO Come o Come EmmauelJoh TayagNo ratings yet

- Moot Court Case Law Report FINALLYDocument22 pagesMoot Court Case Law Report FINALLYSavitha Sree0% (1)

Redemptive Education 3

Redemptive Education 3

Uploaded by

kasserian.sealy4066Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Redemptive Education 3

Redemptive Education 3

Uploaded by

kasserian.sealy4066Copyright:

Available Formats

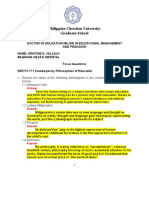

R E D E M P T I V E

E D U C A T I O N

P A R T I I I

Implications

of Philosophy for

Adventist Education

(CONTINUED)

B Y G E O R G E R . K N I G H T

AP P R O V E D F O R 0.5 CO N T I N U I N G ED U C A T I O N UN I T S *

38 The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 http://jae.adventist.org

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Part I in this sequence discussed the major philosophic categories related to reality,

truth, and value and examined each of those areas from an Adventist perspective. Build-

ing upon that philosophic foundation, Part II began to explore its implications for educa-

tional practice, particularly in terms of the nature of the student, the aims of Adventist

education, and the ministerial role of the teacher. Part III discusses a Christian approach

to curriculum, moves on to the implications of a Christian philosophy for teaching

methodology and the social function of Adventist education, and closes with a perspec-

tive on the importance of Adventist educators being faithful to the philosophy that un-

dergirds their schools.

A fuller discussion of many of the topics covered in this article may be found in the

author’s Philosophy and Education: An Introduction in Christian Perspective, 4th ed.

(Berrien Springs, Mich.: Andrews University Press, 2006) and Myths in Adventism: An

Interpretive Study of Ellen White, Education, and Related Issues (Hagerstown, Md.: Re-

view and Herald Publ. Assn., 1985, 2010).

“T

he term curriculum comes from the Latin classified human activity in a hierarchical order

word currere, which means to run a race.” based on importance. He chose the following

In a general sense it represents “all the stratification, in terms of descending conse-

courses and experiences at an institution.”1 quence: (1) those activities relating directly to

One author defines it as “a road map in self-preservation, (2) those activities that indi-

broad strokes that points individuals in the rectly minister to self-preservation, (3) those

direction of Christian maturing.”2 activities having to do with the rearing of off-

But, we need to ask, what should be included spring, (4) those activities pertaining to politi-

in the map? And on what basis should decisions cal and social relations, (5) those activities that

be made? Those questions bring us to the issue relate to the leisure part of life and are devoted

of what knowledge is of most worth. to the tastes and appetites.4

His essay then proceeded to analyze human

What Knowledge Is of Most Worth? affairs from a naturalistic-evolutionary perspec-

One of the most enlightening and coherent es- tive, and eventually provided an unequivocal

says ever published on the relationship of philo- reply to his leading question: “What knowledge

sophic beliefs to the content of the curriculum is of most worth?—the uniform reply is—Sci-

was developed by Herbert Spencer (a leading so- ence. This is the verdict on all the counts.”

cial Darwinist) in 1854. “What Knowledge Is of Spencer’s explanation of his answer related Sci-

Most Worth?” was both the title and the central ence (broadly conceived to include the social

question of the essay. To Spencer, this was the and practical sciences, as well as the physical

“question of questions” in the realm of educa- and life sciences) to his five-point hierarchy of

tion. “Before there can be a rational curriculum,” life’s most important activities. His answer was

he argued, “we must settle which things it most built upon the principle that whichever activities

concerns us to know; . . . we must determine the occupy the peripheral aspects of life should also

relative value of knowledges.”3 occupy marginal places in the curriculum, while

Spencer, in seeking to answer his question, those activities that are most important in life

H O W I T W O R K S :

After you have studied the content presented here, send for the test, using the form on page 60. Upon successful completion

of the test, you will receive a report on the Continuing Education Units you’ve earned, and the certification registrar of your

union conference office of education will be notified (North American Division only).

*Approved by the North American Division Office of Education. The tests for Parts I, II, and III must be successfully completed

to meet alternative teaching certification requirements as outlined in Section 5.1 of the K-12 Educators Certification Manual.

http://jae.adventist.org The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 39

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

should be given the most important place in the jects of the curriculum in such a way that they

course of studies.5 make sense, but to discover such a pattern. We

Christians will of necessity reject Spencer’s live in a world that has so fragmented knowl-

conclusions, which are built upon a naturalistic edge that it is difficult to see how our various

metaphysics and epistemology, but they must realms of expertise relate to the whole. It is in

not miss the larger issue underlying his argu- this context that C. P. Snow’s “Two Cultures”—

ment. It is crucial that Adventists understand with its discussion of the great gulf between the

the rationale for the curriculum in their institu- humanities and the sciences—takes on partic-

tions of learning. Mark Van Doren noted that ular significance and meaning.8

“the college is meaningless without a curricu- Our world is one in which subject-area

lum, but it is more so when it has one that is scholars have too often lost the ability to com-

meaningless.”6 municate with one another because they fail to

The Adventist educator must, with Spencer, see the significance of their subject matter in

settle the issue of “which things it most con- relation to the ”big picture.” To complicate mat-

cerns us to know.” The answer to that ques- ters, we find existentialists and postmodernists

tion, as Spencer noted, leads directly to an un- denying external meaning, and analytic phi-

derstanding of the relative values of various Modern secular losophers suggesting that since we can’t dis-

kinds of knowledge in the curriculum. Ad- Why should there cover meaning, we should focus on defining

ventist educators can study Spencer’s essay and people have thrown our words and refining our syntax.

the methodology included therein and gain be a blind spot The search for meaning in the total educa-

substantial insights into the important task of

out Christianity tional experience has been a major quest for

curriculum development in the context of their

distinctive worldview. in hiring qualified more than a century. Some have defined the in-

tegrating center as the unity of the classics, while

Authentic and viable curricula must be de- as a unifying force others have viewed it in terms of the needs of so-

veloped out of, and must be consistent with, a teachers— ciety, vocationalism, or science. None of those

school’s metaphysical, epistemological, and ax-

and have tended to approaches, however, has been broad enough,

iological bases. It is therefore a foundational

truth that different philosophic approaches will

individuals who and their claims have usually been divisive

rather than unifying. We seem to live in a schiz-

concentrate on

emphasize different curricula. One implication

of that fact is that the curriculum of Adventist work with the most ophrenic world in which many claim that there

is no external meaning, while others base their

schools will not be a readjustment or an adap- the details of their scientific research on postulates that point to an

tation of the secular curriculum of the larger so- valuable entities overall meaning. Modern secular people have

ciety. Biblical Christianity is unique. Therefore,

knowledge thrown out Christianity as a unifying force and

the curricular stance of Adventist education

will be unique.

on earth, the future have tended to concentrate on the details of their

knowledge rather than on the whole. As a result,

Another major issue in curriculum develop- rather than on the intellectual fragmentation continues to be a large

ment is to discover the pattern that holds the cur- generation. problem as human beings seek to determine

riculum together. Alfred North Whitehead

claimed that curricular programs generally suffer

whole. what knowledge is of most worth.

For Adventist educators, the problem is quite

from the lack of an integrating principle. “Instead different. They know what knowledge is of most

of this single unity, we offer children—Algebra, worth, because they understand humanity’s

from which nothing follows; Geometry, from greatest needs. They know that the Bible is a cos-

which nothing follows; Science, from which mic revelation that transcends the limited realm

nothing follows; History, from which nothing fol- of humanity, and that it not only reveals the

lows; a Couple of Languages, never mastered; human condition but also the remedy for that

and lastly, most dreary of all, Literature, repre- condition. They further realize that all subject

sented by plays of Shakespeare, with philological matter becomes meaningful when seen in the

notes and short analyses of plot and character to light of the Bible and its Great Controversy strug-

be in substance committed to memory. Can such gle between good and evil. The problem for Ad-

a list be said to represent Life, as it is known in ventist educators has not been to find the pattern

the midst of the living of it? The best that can be of knowledge in relation to its center, but rather

said of it is that it is a rapid table of contents to apply what they know.

which a deity might run over in his mind while All too often the curriculum of Christian

he was thinking of creating a world, and has not schools, including Adventist institutions, has

yet determined how to put it together.”7 been “a patchwork of naturalistic ideas mixed

However, the crux of the problem has not with Biblical truth.” That has led, Frank Gae-

been ignorance of the need for some overall belein claims, to a form of “scholastic schizo-

pattern in which to fit together the various sub- phrenia in which a highly orthodox theology

40 The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 http://jae.adventist.org

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

coexists uneasily with a teaching of non-reli- can develop—an educational context in which

gious subjects that differs little from that in sec- young people can be taught to think “Chris-

ular institutions.”9 The challenge confronting tianly” about every aspect of reality.12

the curriculum developer in an Adventist

school is to move beyond a curricular view fo- The Strategic Role of the Bible in

cused on the bits and pieces, and to find a way the Curriculum

to clearly and purposefully integrate the details A second postulate follows that of the unity

of knowledge into the biblical framework. That of all truth: The Bible is the foundational and

task brings us to the unity of truth. contextual document for all curricular items in

the Christian school. This postulate is a natural

The Unity of Truth outcome of a bibliocentric, revelational episte-

A basic postulate underlying the Christian mology. Just as special revelation forms the basis

curriculum is that “all truth is God’s truth.”10 of epistemological authority, so also it must be

From the biblical viewpoint, God is the Creator the foundation of the curriculum. Our discussion

of everything. Therefore, truth in all fields stems of epistemology noted that the Bible is not an ex-

from Him. Failing to see this point clearly has led haustive source of truth. Much truth exists out-

many to construct a false dichotomy between the side of the Bible, but it is important to note that

secular and the religious. That dichotomy im- no truth exists outside the metaphysical frame-

plies that the religious has to do with God, while work of the Bible. “The teaching authority of

the secular is divorced from Him. From that Scripture,” Arthur Holmes asserts, “commits the

point of view, the study of science, history, and believer at certain focal points and so provides

mathematics is seen as basically secular, while an interpretive framework, an overall glimpse of

the study of religion, church history, and ethics how everything relates to God.”13

is viewed as religious. The concept of an interpretive framework

That is not the biblical perspective. In the needs constant emphasis in Adventist education.

Scriptures, God is seen as the Creator of the ob- The Bible is not the whole of knowledge, but it

jects and patterns of science and math, as well does provide a frame of reference within which

as the Director of historical events. In essence, to study and interpret all topics. Whether that

there are no “secular” aspects of the curricu- framework is the view of evolutionary natural-

lum. John Henry Newman pointed to that truth ism, the Greek and Roman classics, the biblical

when he wrote that “it is easy enough” on the worldview, or some other perspective makes a

level of thought “to divide Knowledge into great deal of difference. An Adventist school is

human and divine, secular and religious, and Christian only when it teaches all subjects from

to lay down that we will address ourselves to the perspective of God’s Word.

the one without interfering with the other; but Elton Trueblood noted that “the important

it is impossible in fact.”11 question is not, Do you offer a course in religion?

All truth in the Christian curriculum, Such a course might be offered by any institu-

whether it deals with nature, humanity, society, tion. The relevant question is, Does your reli-

or the arts, must be seen in proper relationship gious profession make a difference? . . . A mere

to Jesus Christ as Creator and Redeemer. It is department of religion may be relatively insignif-

true that some forms of truth are not addressed icant. The teaching of the Bible is good, but it is

in the Scriptures. For example, nuclear physics only a beginning. What is far more important is

is not explained in the Bible. That, however, the penetration of the central Christian convic-

does not mean that nuclear physics is not con- tions into the teaching” of every subject.14

nected with God’s natural laws or that it does Frank Gaebelein was making the same point

not have moral and ethical implications as its when he wrote that there exists “a vast differ-

applications affect the lives of people. Christ ence between education in which devotional

was the Creator of all things—not just those exercises and the study of Scripture have a

things people have chosen to call religious place, and education in which the Christianity

(John 1:1-3; Colossians 1:16). of the Bible is the matrix of the whole program

All truth, if it be truth indeed, is God’s truth, or, to change the figure, the bed in which the

no matter where it is found. As a result, the cur- river of teaching and learning flows.”15

riculum of the Christian school must be seen as An educational system that maintains a split

a unified whole, rather than as a fragmented and between the areas it defines as secular or reli-

rather loosely connected assortment of topics. gious can justify tacking on religious elements

Once that viewpoint is recognized, education to a basically secular curriculum. It may even

will have taken a major step forward in creating go so far as to treat the Bible as the “first

an atmosphere in which the “Christian mind” among equals” in terms of importance. But the

http://jae.adventist.org The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 41

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

school whose constituency and teachers em- even human life itself, takes on new meaning in

brace the idea that “all truth is God’s truth” will the light of God’s Word. It is imperative, there-

find itself bound by that belief to develop a cur- fore, that Adventist schools teach every subject

ricular model in which the biblical worldview from the biblical perspective.

permeates every aspect of the curriculum. Gaebelein, in his classic treatment of the

According to Ellen White, “the science of re- issue, has suggested that what we need is the

demption is the science of all sciences,” and the “integration” of every aspect of the school pro-

Bible is “the Book of books.”16 Only an under- gram with the biblical worldview. Integration

standing of that “science” and that “Book” “means ‘the bringing together of parts into the

makes everything else meaningful in the fullest whole.’”19 “The call, then,” he writes, “is for a

sense. Viewed in the light of “the grand central wholly Christian worldview on the part of our

thought” of the Bible, Ellen White points out, education. We must recognize, for example,

“every topic has a new significance.”17 Every stu - that we need teachers who see their subjects,

dent, she noted in another connection, should whether scientific, historical, mathematical, lit-

gain a knowledge of the Bible’s “grand central erary, or artistic, as included within the pattern

theme, of God’s original purpose for the world, of God’s truth.”20 This is the rightful place of

of the rise of the great controversy, and of the religion in education, claimed Henry P. Van

work of redemption. He should understand the Dusen in his Rockwell Lectures, not because

nature of the two principles that are contending the churches say so or because it is dictated by

for supremacy, and should learn to trace their tradition, but “because of the nature of Real-

working through the records of history and proph- ity.”21 After all, God is the being whose exis-

ecy, to the great consummation. He should see tence brings unity and meaning to the universe,

how this controversy enters into every phase of and it is His revelation that provides unity and

human experience; how in every act of life he meaning to the curriculum.

himself reveals the one or the other of the two Unfortunately, in the most common curricu-

antagonistic motives; and how, whether he will lum design, Bible or religion is just one topic

or not, he is even now deciding upon which side among many, as illustrated in Figure 122 on

of the controversy he will be found.”18 page 43. In that model, every topic is studied

The conflict between good and evil has left in the context of its own logic, and each is re-

no area of existence untouched. On the nega- garded as basically independent of the others.

tive side, we see the controversy in the deteri- History or literature teachers are not concerned

oration of the world of nature, in war and suf- with religion, and religion teachers do not in-

fering in the realm of history and the social volve themselves with history or literature,

sciences, and in humanity’s concern with lost- since all teach their own specialty. Each subject

ness in the humanities. On the positive side, we has its own well-defined territory and tradi-

discover the wonder of a natural order that tional approach. This model rarely delves into

seems to be purposefully organized, in human- the relationship between fields of study, let

ity’s ability to relate to and care for its fellows alone their “ultimate meaning.”

in social life, and in its deep visions and desires In an attempt to correct the above problem,

for wholeness and meaningfulness. “Why,” some enthusiastic reformers have gone to the

every individual is forced to ask, “is there evil other extreme and developed a model that is il-

in a world that seems so good? Why is there lustrated in Figure 2.23 This model seeks to

death and sorrow in an existence that is so del- make the Bible and religion into the whole cur-

icately engineered for life?” riculum, and, as a result, also misses the mark,

The questions go on and on, but without su- since the Bible never claims to be an exhaustive

pernatural help, earthbound humans are help- source of truth. It sets the framework for the

less as they seek to discover ultimate answers. study of history and science and touches upon

They can discover bits and pieces of “truth” those topics, but it is not a “textbook” for all

and build theories concerning their meaning, areas that students need to understand. On the

but only in God’s cosmic breakthrough to hu- other hand, it is a “textbook” in the science of

manity in its smallness and lostness is that ul- salvation and a source of inspired information

timate meaning provided. concerning both the orderliness and the abnor-

God’s special revelation contains the answers mality of our present world, even though it

to humankind’s “big questions.” It is that reve- never claims to be a sufficient authority in all

lation, therefore, that must provide both the areas of possible truth.

foundation and the context for every human A third organizational scheme could be la-

study. Each topic within the curriculum, and beled the foundational and contextual model

42 The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 http://jae.adventist.org

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

(see Figure 324 below). It implies that the Bible schools must approach each subject in the light

(and its worldview) provides a foundation and of the biblical perspective in order to under-

a context for all human knowledge, and that its stand its fullest meaning.

overall meaning infuses every area of the cur- The broken lines in Figure 3 signify the lack

riculum and adds significance to each topic. of rigid divisions between the various subjects,

This corresponds with what Richard Edlin help- and the absence of any false dichotomy between

fully refers to as the “permeative function of the the sacred and the secular. The two-headed ar-

Bible.” “The Bible,” he notes, “is not frosting rows indicate not only that the Bible helps us un-

on an otherwise unaltered humanist cake. It derstand every topic in the curriculum, but also

needs to be the leaven in the educational loaf, that the study of history, science, and so on also

shaping the entire curriculum from its base up sheds light on the meaning of Scripture. God has

as it permeates through the whole school pro- revealed Himself through the Bible in a special

gram.”25 Figure 3 sets forth an integration revelation, and through His created world in a

model, indicating that educators in Adventist general revelation. We can grasp the significance

of the latter only in the light of the former, but

both shed light on each other since all truth has

its origin in God. Every topic in the curriculum

has an impact upon every other, and all achieve

Mathematics

maximum meaning when integrated within the

Literature

Et Cetera

Religion

Science

History

biblical context.

Christianity and the Radical Reorientation

of the Curriculum

One of the challenges that educators must

face in developing a biblically oriented curricu-

lum in the 21st century is the diverse world-

views that permeate contemporary society, in-

Figure 1. Curriculum Model: Self-Contained Subject Matter Areas cluding that of postmodernism, which claims

that there is no such thing as a genuine world-

view anchored in reality—that all worldviews

or grand narratives are human constructions.

But that claim is itself a worldview with defi-

Bible and Religion nite metaphysical and epistemological presup-

positions.26

That thought raises the issue of the general

lack of self-consciousness evidenced by most

people. Harry Lee Poe reflects upon that topic

Figure 2. Curriculum Model: The Bible as the Whole when he writes that “every discipline of the

academy makes enormous assumptions and

goes about its business with untested and un-

BIBLICAL PERSPECTIVE challenged presuppositions. We are used to

this. Assumptions and presuppositions have

BIBLICAL PERSPECTIVE

BIBLICAL PERSPECTIVE

become so much a part of the fabric of life that

we do not notice the threads. These threads

make up the worldview of the culture in which

Mathematics

we live. They are the things ‘everybody knows’

Literature

Et Cetera

Science

and that, therefore, go untested. They are so

History

deeply ingrained in us that we are rarely even

aware of them.”27 In short, worldviews for

many people are subliminal—a part of the

larger culture that is accepted without chal-

lenge.

On the other hand, Poe notes that “in the

marketplace of ideas, the fundamental assump-

BIBLICAL PERSPECTIVE tions . . . to which people cling are the very

things that Christ challenges.”28 Clearly, the

Figure 3. Curriculum Model: The Bible as Foundational and Contextual biblical worldview and the predominant men-

http://jae.adventist.org The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 43

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

tality of the larger culture are often at odds, and along the way. By way of contrast, the Bible

there are different religious and even different features hope in spite of serious problems. It

Christian worldviews. Making people aware of also explores the “only story,” but with revela-

the contrasts results in what sociologist Peter tory insight into the meaning of a world that

Berger refers to as “collisions of conscious- forms the battleground for a cosmic clash be-

ness”29 and what philosopher David Naugle la- tween the forces of good and evil.

bels “worldview warfare.”30 The responsibility of the literature teacher in

From that perspective, by its very nature, the the Adventist school is to help students learn

biblically based curriculum challenges other to read critically so that they can grasp the

methods of curricula organization and suggests meaning of their assignments in terms of the

a radical reorientation of the subject matter in great controversy between good and evil.33 Lit-

Adventist schools. The essential point that the erary study is not merely a relaxing excursion

Adventist educator must grasp is that the teach- into the realm of art. T. S. Eliot observed that

ing of any topic in an Adventist school must not what we read affects “the whole of what we

be a modification of the approach used in non- are. . . . Though we may read literature merely

Christian schools. It is rather a radical reorien- for pleasure, of ‘entertainment’ or of ‘aesthetic

tation of that topic within the philosophical enjoyment,’ this reading never affects simply a

framework of Christianity.

A good place to begin examining the radical The impact of sort of special sense: it affects our moral and

religious existence.”34 There is no such thing as

reorientation of the curriculum is the field of artistic neutrality. The function of literary study

literary study.31 The study of literature holds a literary study is all in an Adventist school is not just to help stu-

crucial position in all school systems because dents become “learned” in the great writers of

literature addresses and seeks to answer peo-

ple’s most important questions; reveals human-

the more powerful the past and present; it must also help them to

view the issues at stake in the controversy be-

ity’s basic desires, wishes, and frustrations; and

develops insight into human experience. Be- because it is tween good and evil with more clarity and sen-

sitivity.

yond raising aesthetic sensitivity, the study of The Bible in this context provides an inter-

literature leads to inductive insights in such delivered in a pack- pretive framework that transcends human in-

areas as psychology, philosophy, religion, his- sights. “Every topic,” including literature, “has

tory, and sociology; and it provides information

about such topics as human nature, sin, and

age with which a new significance,” Ellen White suggests,

when viewed in the light of the “grand central

the meaning and purpose of human existence. theme” of the Scriptures.35 The Bible is quite a

The impact of literary study is all the more humans emotionally realistic book. Those literary extremes that ig-

powerful because it is delivered in a package nore evil at one end of the spectrum or glorify

with which humans emotionally identify. That

is, it reaches people at the affective and cogni-

identify. it at the other are neither true nor honest and

certainly allow no room for a viable concept of

tive levels simultaneously. In the fullest sense justice. The challenge for Christians is to ap-

of the words, literary content is philosophical proach literary study in such a way that it leads

and religious because it deals with philosophi- readers to see the reality of humanity and its

cal and religious issues, problems, and an- world as it actually is—filled with sin and suf-

swers. Literary study, therefore, holds a central fering, but not beyond hope and the redeeming

position in curricular structures and provides grace of a caring God.

one of the most powerful educational tools for The interpretive function of literary instruc-

the teaching of religious values. tion has generally been approached in two dif-

Secularist John Steinbeck caught the signif- ferent ways (see Drawings A and B in Figure 436

icance of the central core of great literature in on page 45). Drawing A represents a classroom

his classic East of Eden when he wrote that “I approach that emphasizes the literary qualities

believe that there is one story in the world, and of the material and uses the Bible or ideas from

only one. . . . Humans are caught—in their the Bible from time to time as asides. The only

lives, in their thoughts, in their hungers and difference between this approach and the way

ambitions, in their avarice and cruelty, and in literature is taught in non-Christian institutions,

their kindness and generosity too—in a net of is that biblical insights are added.

good and evil. . . . There is no other story.”32 Drawing B depicts the study of literature in

While there may be no other story, there are the context of the biblical perspective and its

certainly multiple interpretations of the impli- implications for humanity’s universal and per-

cations of that story. For Steinbeck, from his sonal dilemmas. It interprets literature from the

earthbound perspective, there is no hope. The distinctive vantage point of Christianity, recog-

end is always disastrous despite hopeful signs nizing the abnormality of the present world and

44 The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 http://jae.adventist.org

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

God’s activity in that world. Using that ap- The same might be said of the life, physical,

proach, the study of literature in a Christian in- and social sciences, or physical education, or

stitution can be richer than in a secular school, agriculture in the curriculum of an Adventist

since non-Christians are handicapped by their school. The Bible provides the framework for

lack of the all-important (in terms of insight understanding a troubled world, while the dis-

and interpretation) biblical view of sin and sal- ciplines bring forth the bits and pieces. The

vation. That does not mean that literary ele- Bible provides the pattern that gives interpre-

ments such as plot and style are unimportant, tative meaning to the otherwise meaningless

but rather that they are not, within the context details uncovered by the scholar. The Bible thus

of Christianity, the most important aspects of becomes the focal point of integration for all of

literary study. human knowledge.

Note also that in Drawing B the arrows indi- That fact is especially important in the sci-

cate a two-way transaction between the biblical ences, an area in which

perspective and literary study. Not only does the past century has wit- A

the biblical worldview help us interpret litera- nessed one of the most

ture, but literary insights also help us to better significant “cultural wars” L I T E R A T U R E

understand religious experience within the con- of all time. Unfortunately,

text of religious truth. unproven hypotheses re-

Adventist teachers must help students move lated to macroevolution39

beyond the story to the meaning of its insights have too often been

for daily life. The function of literary study in a granted the status of Bible

Christian institution, Virginia Grabill writes, is “fact” and then been used

to help students learn how to “think” about the to provide the interpretive and

issues of life—their personal identity and pur- framework for science in Religion

pose, the presence of good and evil, justice and most schools.

forgiveness, the beautiful and the ugly, sexual- The basic problem: The

ity and spirituality, ambition and humility, joy cosmologies of macro-

and suffering, purity and guilt, and so on.37 evolution and biblical cre- B

C. S. Lewis made a similar point when he ationism are incompati-

wrote that “one of the minor rewards of con- ble. The latter begins with B I B L I C A L

version is to be able at last to see the real point a perfect creation, contin- P E R S P E C T I V E

of all the literature we were brought up to read ues on with humanity’s

with the point left out.”38 The goal of literary fall into sin, and then

study in a Christian school is not to transmit a transitions to God’s solu-

body of knowledge, but to develop a skill—the tion for removing the ef-

ability to think critically and to interpret literary fects of the Fall. But the Literature

insights from the perspective of the biblical macroevolution scenario

worldview. is diametrically opposed

We have spent a great deal of time examin- to the biblical model.

ing literary study in the reoriented Christian From the perspective of

curriculum. Similar observations could be macroevolution, all crea-

made about history and social studies. History tures originated as less- Figure 4. The Contextual

in the Christian curriculum is viewed in the complex organisms and Role of the Biblical

Perspective

light of the biblical message as God seeks to have been improving

work out His purpose in human affairs. The through the processes of

Bible is seen as providing the interpretive natural selection. In that model there is no need

framework for events between the fall of Adam for redemption and restoration.

and the second coming of Jesus. The Bible is The biblical framework for interpreting nat-

not treated as a comprehensive history text- ural history is constructed from the Genesis ac-

book, but as an account that focuses on the his- count, which states that God created the earth

tory of salvation. There are, of course, points of in six days, and that He created human beings

intersection between general history and the in His own image. The basic facts of the Gene-

Bible in terms of events, prophecy, and archae- sis creation story do not allow for either

ology. But the Christian teacher of history real- macroevolution (in which God has no involve-

izes that the specific points of intersection are ment) or theistic evolution (which limits God

in the minority, and that the major function of to the role of mere initiator of the evolutionary

the Bible in his or her discipline is to provide a process). Adventist schools must be unapolo-

perspective for understanding. getically creationist. The biblical metaphysic

http://jae.adventist.org The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 45

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

stands at the very foundation of why the Sev- universe and the validity of empirical observa-

enth-day Adventist Church chose to establish tion are metaphysical and epistemological pre-

Adventism’s educational alternative. suppositions that undergird science but are

The integration of human knowledge into rejected by many modern and postmodern peo-

the biblical framework is important, but it must ple in both Western and Eastern cultures. It is

be done with care and wisdom. Frank Gae- essential to make these assumptions evident in

belein, in discussing how to develop correla- class presentations because they are often

tions between Christian concepts and the sub- taken as facts and are “invisible” to the average

ject matter of the various fields of study, points student who has been raised in an age that has

out some necessary cautions. A major pitfall, placed its uncritical faith in science and math-

as he sees it, is the danger “of a false integra- ematics rather than in the Creator of scientific

tion through forced correlations that are not and mathematical reality. This integration is

truly indigenous to the subject in question. most natural at the elementary, secondary, and

Such lugging in of stilted correlations, even introductory college levels, since courses at

though motivated by Christian zeal, is liable to these levels provide the intellectual context for

do more harm than good through giving the im- such sophisticated courses as theoretical me-

pression that integration of specific subjects chanics and advanced calculus.

with God’s truth is a put-up job. Christian math and science teachers will

“What may be needed is a more relaxed at- also creatively utilize the natural points of in-

tack upon the problem and a clearer realization tegration between their subject matter and re-

of the limits under which we are working. Here ligion. Mathematics, for example, certainly has

a suggestion by Emil Brunner is useful. Speak- contact points with the Christian faith when it

ing of the distortion brought into our thinking deals with such areas as infinity and the exis-

through sin, he sees it at its greatest in such tence of numbers in other parts of daily life,

areas as theology, philosophy, and literature, from music to crystallography and astronomy.

because these are nearest man’s relation to God The world of mathematical precision is God’s

and have thus been most radically altered world; thus, mathematics is not outside the pat-

through the fall. They therefore stand most in tern of God’s truth.42

need of correction, and in them correlation Before moving away from the radical reori-

with Christianity is at its highest. But as we entation of the curriculum, we need to empha-

move from the humanities to the sciences and size that it is of the utmost importance for Ad-

mathematics, the disturbance through sin di- ventist educators and their constituents to

minishes almost to the vanishing point. Thus realize that the biblical worldview must domi-

the Christian teacher of the more objective sub- nate the curriculum of our schools to ensure that

jects, mathematics in particular, ought not to they are Adventist in actuality rather than

seek for the detailed and systematic correla- merely in name. Adventist educators must ask

tions that his colleagues in psychology, litera- themselves this probing question: If I, as a

ture, or history might validly make.”40 teacher in an Adventist school, am teaching the

Gaebelein does not mean that there are no same material in the same way that it is pre-

points of contact between Christianity and top- sented in a public institution, then what right

ics such as mathematics, but rather that they do I have to take the hard-earned money of my

are fewer and less obvious.41 Christian teachers constituents? The answer is both obvious and

will utilize those points while not seeking to frightening. Adventist education that does not

force integration in an unnatural manner. provide a biblical understanding of the arts, sci-

However, the integration of mathematics ences, humanities, and the world of work is not

and the physical sciences with Christian belief Christian. One major aim of Adventist educa-

may be even more important than the integra- tion must be to help students think christianly.

tion of literature and the social sciences with

Christianity because many students have im- The Balanced Curriculum

bibed the idea that they are “objective,” neu- Beyond the realm of specific subject matter

tral, and functional and have no philosophical in the Adventist school is the larger issue of the

presuppositions, biases about reality, or cosmo- integration of the curricular program in such a

logical implications. On the contrary, the study way that it provides for the balanced develop-

of mathematics and the “hard” sciences is to- ment of the various attributes of students as

tally embedded in bias and assumption. they are being restored to their original position

Mathematics, for example, like Christianity, as beings created in the image and likeness of

is built upon unprovable postulates. Beyond God. In the section on the nature of the stu-

that, assumptions such as the orderliness of the dent, we noted that at the Fall humanity, to a

46 The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 http://jae.adventist.org

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

large extent, experienced a fracturing of that moral training has been neglected. Many youth

image in the spiritual, social, mental, and phys- come forth from institutions of learning with

ical realms. We also saw that education is basi- morals debased, and physical powers enfee-

cally an agent of redemption and restoration as bled; with no knowledge of practical life, and

God seeks to use human educators to restore little strength to perform its duties.”45 The prac-

fallen individuals to their original state. tical aspects of life were important to Ellen

The curriculum must, therefore, establish an White’s sense of educational balance. Thus she

integrated balance that facilitates that restora- could write that “for their own physical health

tion. It cannot focus merely on mental devel- and moral good, children should be taught to

opment or career preparation. It must develop work, even if there is no necessity so far as

the whole person—the physical, social, spiri- want is concerned.”46

tual, and vocational as well as the mental needs Balance is equally important in the informal

of each student. or extracurricular aspects of the school’s cur-

Unfortunately, traditional education focused riculum. This includes a multiplicity of organi-

almost exclusively on the mental. Greek ideal- zations and activities, such as clubs, musical

ism set the stage for more than two millennia groups, athletics, work experiences, school

of miseducation that ignored or denigrated both publications, and so on, which must all be

physical development and preparation for use- Adventist brought into harmony with the purpose of the

ful vocations. institution and integrated with the Christian

By contrast, the Bible is neither anti-physical

nor anti-vocational. After all, God created a

education that does message, just as is the formal curriculum, to

ensure that the school does not give a dichoto-

physical earth He deemed “very good” (Genesis

1:31),43 and He intends to resurrect human be-

not provide a mous message to its students, constituency,

and onlookers. The Adventist school has two

ings with physical bodies at the end of time (1 major tasks in regard to the informal curricu-

Thessalonians 4:13-18; Philippians 3:21). Be- biblical understand- lum—the choice of activities and the creation

yond that, Jesus was educated to be a carpen- of guidelines for the implementation of the ac-

ter, and the wealthy Paul was trained as a tent

maker even though it appeared that he would

ing of the arts, tivities selected. Both of those tasks must be

based on biblical values.

never need to work at the trade.

But those biblical principles were obscured sciences, humani- That thought brings us to the topic of values

education throughout the curriculum. Arthur

in the early centuries of the Christian Church Holmes made an important point when he

when its theology amalgamated with Greek ties, and the noted that “education has to do with the trans-

thought. That resulted in some very non-bibli- mission of values.”47 The issue of values is cen-

cal educational theory and practice.

The 19th century experienced a wave of re-

world of work is not tral to much of the conflict over education

today. What we find in most places, including

form, with calls for a return to balanced edu-

cation. Ellen White spoke about that needed re- Christian. schools, is an ethical relativism that goes

against the very core of the Bible’s teachings.

form. In fact, it was at the center of her When modern culture lost the concept of an

educational philosophy. We saw that in the eternal God it also lost the idea that there are

very first paragraph of Education, in which she universal values that apply across time, indi-

noted that “true education . . . is the harmo- viduals, and cultures. Ronald Nash was correct

nious development of the physical, the mental, when he asserted that “America’s educational

and the spiritual powers.”44 crisis is not exclusively a crisis of the mind,”

To restore individuals to wholeness, Advent- but also a crisis of the “heart,” a values crisis.48

ist education cannot neglect the balance be- This crisis is evident not only in schools, but

tween the physical and the mental. The impor- also in the public media, which all too often

tance of that balance is highlighted by the fact promotes values that are non-Christian or even

that it is the body that houses the brain, which anti-Christian.

people must use in order to make responsible These are realities that the Adventist school

spiritual decisions. Whatever affects one part cannot afford to ignore. The good news is that

of a person affects the total being. Individuals Christian educators, operating within the bibli-

are wholistic units, and the curriculum of the cal framework, have a strategic advantage over

Adventist school must meet all their needs to those with other orientations because they have

ensure that they achieve wholeness and operate an epistemological and metaphysical grounding

at peak efficiency. Ellen White was speaking for their value system, which is not available to

about the traditional imbalance in education others. As Robert Pazmiño puts it, “the Chris-

when she wrote that “in the eager effort to se- tian educator can propose higher values be-

cure intellectual culture, physical as well as cause he or she can answer such questions as:

http://jae.adventist.org The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 47

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

What are persons and their ultimate end? What pre-eminent purposes into consideration.

is the meaning and purpose of human activity? That does not mean that somehow Adventist

What, or rather, who is God? These questions education will invent unique and original ways

can be answered with a certainty and surety of teaching in the same sense that Christianity

which is not possible outside of a revealed is a unique religion and Christ is a unique per-

faith.”49 son. Obviously, Adventist educators will use

Pazmiño also points out the existence of a many, if not all, of the same methods as other

hierarchy of values, with spiritual values pro- teachers. They will, however, select and em-

viding the context for evaluating options in phasize those methodologies that best aid them

ethics and aesthetics, as well as in the scien- in helping their students to develop Christlike

tific, political, and social realms.50 That being characters and reach the other goals of Ad-

the case, Christian educators must purposefully ventist education.

develop formal and informal curricula in the

light of biblical values. The biblical value sys- Education, Thinking, Self-Control,

tem stands at the very foundation of Christian and Discipline

education.

And, we need to note, the values taught in When modern Central to the issue of the development of

Christian character is recognizing that human

a biblically based school system will not relate beings are not simply highly developed animals

only to individual decision-making but will also culture lost the that respond to reward and punishment. The

reflect upon the social whole. Like the Old Tes- Bible pictures human beings as being created

tament prophets, Adventist education will raise

significant issues related to social justice in an

concept of an eter- in the image of God and having, even in their

fallen state, the ability to think reflectively.

unjust world because biblical valuing involves

the public as well as the private world of be- nal God it also Because humans can engage in reflective

thought, they can make meaningful decisions

lievers. about their own actions and destiny. Students

As we view the Christian curriculum in all lost the idea that in an Adventist school must be educated to

of its complexity, we must never forget the con- think for themselves rather than merely be

troversy between the forces of good and the

powers of evil within our metaphysics, episte-

there are trained, like animals, to respond to environ-

mental cues. Human beings, created in God’s

mology, axiology, and our individual lives. The image, are to be educated “to be thinkers, and

conflict between Christ and Satan is evident in universal values not mere reflectors of other men’s thought.”51

the curriculum. Each Adventist school is a bat- It is true that there are some training aspects in

tlefield in which the forces of Christ are being

challenged by the legions of Satan. The out-

that apply the human learning process, but those ap-

proaches generally dominate only when the

come will, to a large extent, be determined by

the position given to the Bible in the Adventist across time, individ- person is very young or mentally impaired. The

ideal, as we shall see below, is to move as rap-

school. If Adventist schools are to be truly idly as possible, with any given student, from

Christian, then the biblical perspective must be uals, and cultures. the training process to the more reflective ed-

the foundation and context of all that is done. ucative process.

At the heart of Adventist education is the

Methodological Considerations for goal of empowering students to think and act

Adventist Educators reflectively for themselves rather than just to

respond to the word or will of an authority fig-

A major determinant of the teaching and ure. Self-control, rather than externally im-

learning methodologies of any philosophy of posed control, is central in Adventist education

education is the educational goals of that per- and discipline. Ellen White put it nicely when

spective and the epistemological-metaphysical she wrote that “the discipline of a human being

framework in which those goals are couched. who has reached the years of intelligence

The aims of Adventist education go beyond ac- should differ from the training of a dumb ani-

cumulating cognitive knowledge, gaining self- mal. The beast is taught only submission to its

awareness, and coping successfully with the master. For the beast, the master is mind, judg-

environment. To be sure, Adventist education ment, and will. This method, sometimes em-

shares those aspects of learning with other sys- ployed in the training of children, makes them

tems of education, but beyond that, it has the little more than automatons. Mind, will, con-

more far-reaching goals of reconciling individ- science, are under the control of another. It is

uals to God and one another and restoring the not God’s purpose that any mind should be

image of God in them. The methodologies cho- thus dominated. Those who weaken or destroy

sen by the Adventist educator must take those individuality assume a responsibility that can

48 The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 http://jae.adventist.org

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

result only in evil. While under authority, the dure in an intelligently chosen course in the

children may appear like well-drilled soldiers; face of distraction, confusion, and difficulty,

but when the control ceases, the character will and you have the essence of discipline. Disci-

be found to lack strength and steadfastness. pline means power at command; mastery of the

Having never learned to govern himself, the resources available for carrying through the ac-

youth recognizes no restraint except the re- tion undertaken. To know what one is to do

quirement of parents or teacher. This removed, and to move to do it promptly and by use of the

he knows not how to use his liberty, and often requisite means is to be disciplined.”55

gives himself up to indulgence that proves his Discipline as self-control has its roots deep

ruin.”52 in the Christian concepts of character develop-

It is for that reason that Ellen White never ment, responsibility, and perseverance. We

seemed to tire of driving home the point that noted earlier that character development is one

“the object of discipline is the training of the of the major aims of Adventist education. Char-

child for self-government. He should be taught acter development and discipline are inextrica-

self-reliance and self-control. Therefore as soon bly entwined. “Strength of character,” Ellen

as he is capable of understanding, his reason White wrote, “consists of two things—power of

should be enlisted on the side of obedience. Let will and power of self-control.”56 The will, fur-

all dealing with him be such as to show obedi- thermore, “is the governing power in the nature

ence to be just and reasonable. Help him to see of man, the power of decision, or choice.”57 Part

that all things are under law, and that disobe- of the function of Christian discipline in the

dience leads, in the end, to disaster and suffer- home and school is to guide and mold the

ing.”53 power of the will as students move toward ma-

Please note that in the above quotations turity.

Ellen White ties together education, thinking, Internal discipline concentrates on developing

self-control, and discipline. That is an impor- children’s wills through allowing them to make

tant insight and one that we too often overlook. choices and to experience the consequences.

In fact, most people equate discipline and pun- Arthur Combs has pointed out that “responsibil-

ishment. But they are two quite distinct con- ity is learned from being given responsibility; it

cepts. Ideally, punishment comes into play only is never learned from having it withheld. . . .

after discipline has failed. Punishment is a neg- Learning to be responsible requires being al-

ative, remedial activity, whereas discipline is lowed to make decisions, to observe results, and

positive and stands at the core of developing a to deal with the consequences of those decisions.

Christian character. A curriculum designed to teach responsibility

In a Christian approach to education, human needs to provide continuous opportunities for

beings must be brought to the place where they students to engage in such processes. To do so,

can make their own decisions and take respon- however, requires taking risks, a terribly fright-

sibility for those choices without continually ening prospect for many teachers and adminis-

being coaxed, directed, and/or forced by a trators.”58

powerful authority. When that goal is achieved, But even the very problem of allowing oth-

and the power to think and to act upon one’s ers to make mistakes arises from the nature of

thoughts is internalized, then people have God and His love. After all, He created a uni-

reached moral maturity. They are not under the verse in which mistakes are possible when He

control of another, but are making their own could have established one that was fool-

moral decisions about how to act toward God proof—but only at the price of creating humans

and other people. Such is the role of self-control as something less than beings in His image. Be-

in the shaping of human beings in the image of ings without genuine choices are automatons

God. Psychiatrist Erich Fromm makes the same rather than free moral agents. God created hu-

point when he writes that “the mature person mans in such a way as to make character de-

has come to the point where he is his own velopment a definite possibility. It is important

mother and his own father.”54 to remember that when people do not have the

Discipline is not something an authority fig- option of making wrong choices, neither do

ure does to a child, but something that adults they have the ability to make correct ones. Peo-

help children learn to do for themselves. John ple cannot develop character if they are con-

Dewey, America’s most influential 20th-century stantly controlled through having their choices

philosopher, reflected on that point when he curtailed. They are then, in essence, merely

wrote that “a person who is trained to consider complex machines rather than moral agents

his actions, to undertake them deliberately . . . created in God’s image. Love and freedom are

is disciplined. Add to this ability a power to en- risky and dangerous, but they are the way God

http://jae.adventist.org The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 49

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I

has chosen to run His universe. dation of the practice of Adventist education.

In a Christian framework, the answer to a One model that describes the progressive in-

lack of discipline is not bigger and better strate- ternalization of discipline appears in Figure 565

gies to bring young people under control, but on page 51. It illustrates in a general way the re-

conscious development and application of tech- lationship between internal and external control

niques to build self-control and a sense of re- and the weaning process that is the goal of re-

sponsibility in each child. We gain nothing if demptive discipline. Infants and extremely young

by authoritative methodologies we manage to children need a great deal of external control, but

produce quiet, order, and student conformity the maturation process should lead progressively

while sacrificing intelligent behavior, responsi- to greater self-control and less external control,

bility, and creativity. until individual children have reached the point

Developing intelligent self-control in others is of moral maturity. At that time, they are ready to

not an easy task. Ellen White writes that “this take their place as responsible persons in the

work is the nicest [most delicate and discerning], adult world. Christian discipline, therefore, is

the most difficult, ever committed to human be- both a positive and liberating power. It “is not,”

ings. It requires the most delicate tact, the finest A. S. De Jong points out, “to keep the child down

susceptibility, a knowledge of human nature, and or to break him, but to lift him up or to heal him;

a heaven-born faith and patience.”59 for that reason discipline may be called upon to

The number of biblically based books written repress only in order to set free, to train children

on this crucial aspect of Adventist education is in the exercise of the freedom of the children of

not great. The best place to begin is the chapter God.”66 The end product of Christian discipline

entitled “Discipline” in Ellen White’s Educa- will be young people who “do right because they

tion.60 It is perhaps the most insightful chapter believe it is right and not because some authority

that she ever wrote in the field of education. tells them to.”67

Deeply rooted in a Christian philosophy, it is a The connection between the developing of

methodological exposition second to none. Read- self-control and the restoration of the image of

ing those 11 pages every week for their entire ca- God has serious implications for educators as

reer, would enrich every teacher’s ministry. Here they select appropriate methodologies for the

are a few samples from that chapter: Christian school. That concept should act as a

• “The wise educator, in dealing with his screening device for Adventist educators as they

pupils, will seek to encourage confidence and choose learning and teaching strategies for the

to strengthen the sense of honor. Children and classroom. They must utilize those methodolo-

youth are benefited by being trusted. . . . Sus- gies that will help to develop what Harro Van

picion demoralizes, producing the very evils it Brummelen refers to as “responsible disciples.”68

seeks to prevent. . . . An atmosphere of unsym-

pathetic criticism is fatal to effort.”61 Beyond Cognition to Commitment

• “The true object of reproof is gained only and Responsible Action

when the wrongdoer himself is led to see his Closely related to the above discussion is the

fault and his will is enlisted for its correction. idea that Christian knowing is not merely pas-

When this is accomplished, point him to the sive. It is, as we noted in our discussion of epis-

source of pardon and power.”62 temology, an active, dynamic experience. Thus,

• “Many youth who are thought incorrigible in a Christian school, instructional methodol-

are not at heart so hard as they appear. Many ogy must move beyond strategies for passing

who are regarded as hopeless may be reclaimed on information. Nicholas Wolterstorff forcefully

by wise discipline. These are often the ones argues that Christian education “must aim at

who most readily melt under kindness. Let the producing alterations in what students tend

teacher gain the confidence of the tempted one, (are disposed, are inclined) to do. It must aim

and by recognizing and developing the good in at tendency learning.” He points out that Chris-

his character, he can, in many cases, correct the tian schools must move beyond techniques for

evil without calling attention to it.”63 merely teaching the knowledge and abilities re-

Such are the challenges and possibilities of quired for acting responsibly, since students

redemptive discipline in line with Christ’s min- can assimilate those ideas without developing

istry of seeking the lost and shaping the char- a “tendency to engage in such action.” Thus “a

acters of those in a relationship to God through program of Christian education will take that

Him. Many of the principles of redemptive dis- further step of cultivating the appropriate ten-

cipline are expounded upon in a very practical dencies in the child. It will have tendency learn-

way in Jim Roy’s Soul Shapers,64 which de- ing as one of its fundamental goals.”69

scribes the methodologies that lie at the foun- Donald Oppewal has developed a teaching

50 The Journal of Adventist Education • October/November 2010 http://jae.adventist.org

C O N T I N U I N G E D U C A T I O N — P A R T I I I