Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EACFFPC Freight Forwarding Module Training Manual

EACFFPC Freight Forwarding Module Training Manual

Uploaded by

Wilson De GuzmanCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- ITT Understanding Freight Forwarding Part 1Document6 pagesITT Understanding Freight Forwarding Part 1Digital EraNo ratings yet

- Freight Clearing and Forwarding ProceduresDocument285 pagesFreight Clearing and Forwarding ProceduresSerdar Kontaş88% (17)

- HIMP Guide E-Feb17Document23 pagesHIMP Guide E-Feb17JeganeswaranNo ratings yet

- Eacffpc Customs Laws and Procedure Training ManualDocument146 pagesEacffpc Customs Laws and Procedure Training ManualKerretts Kimoikong89% (9)

- 23 23 Market Potential of Freight Forwarding BusinessDocument71 pages23 23 Market Potential of Freight Forwarding BusinessAjaish AuNo ratings yet

- Logistics Management-Unit2 CompleteDocument93 pagesLogistics Management-Unit2 CompleteVasanthi Donthi100% (1)

- Sustainability of Freight Forwarding FinDocument49 pagesSustainability of Freight Forwarding FinVictor Rattanavong0% (1)

- The Freight Forwarding Process FlowDocument7 pagesThe Freight Forwarding Process Flowomair ashfaqNo ratings yet

- Export Documentation and ProceduresDocument29 pagesExport Documentation and ProceduresVetri M KonarNo ratings yet

- Clearing and Forwarding AgentsDocument6 pagesClearing and Forwarding Agentshermandeep5100% (1)

- TLIA3107C - Consolidate Freight - Learner GuideDocument54 pagesTLIA3107C - Consolidate Freight - Learner GuideromerofredNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Maritime Logistics PDFDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Maritime Logistics PDFTambe Chalomine AgborNo ratings yet

- Global GPS Tracking Device Market - Industry Trends and Forecast To 2026Document5 pagesGlobal GPS Tracking Device Market - Industry Trends and Forecast To 2026suraj hambirepatilNo ratings yet

- Study On Planning, Development and Operation of Dry Ports of International Importance - 26-02-2016 PDFDocument145 pagesStudy On Planning, Development and Operation of Dry Ports of International Importance - 26-02-2016 PDFAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 On The WatchDocument10 pagesUnit 9 On The WatchmytnameNo ratings yet

- Eacffpc Freight Forwarding Module Training ManualDocument161 pagesEacffpc Freight Forwarding Module Training ManualKerretts Kimoikong100% (5)

- Freight Forwarding End To End in PakistanDocument13 pagesFreight Forwarding End To End in PakistanehsanNo ratings yet

- The Future of ForwardingDocument10 pagesThe Future of ForwardingSalman HamidNo ratings yet

- Role of ConsolidatorDocument8 pagesRole of ConsolidatornehabhatnagarNo ratings yet

- Business ExaminationsDocument51 pagesBusiness ExaminationsEnqdepart100% (1)

- Incoterms CanadaDocument13 pagesIncoterms CanadaNicolas MarionNo ratings yet

- Freight Forwarding Practice and ProcedureDocument50 pagesFreight Forwarding Practice and Procedurezama zamazuluNo ratings yet

- Global Logisitics Freight ForwardersDocument11 pagesGlobal Logisitics Freight ForwardersJaya Prakash LoganathanNo ratings yet

- Freight ForwardingDocument56 pagesFreight ForwardingSujith Nair100% (1)

- Nvocc ReportsDocument11 pagesNvocc Reportsmahi5061100% (1)

- The Complexity Effect of Freight Forwarding Trade Instruments in Project LogisticsDocument12 pagesThe Complexity Effect of Freight Forwarding Trade Instruments in Project LogisticsFariz RahmanNo ratings yet

- Transport and Logistics Insights January 2014Document19 pagesTransport and Logistics Insights January 2014mutton moonswamiNo ratings yet

- Discover The Advantage of A Smarter Supply ChainDocument10 pagesDiscover The Advantage of A Smarter Supply ChainAsma BerkaneNo ratings yet

- Shipping Market Report ChinaDocument11 pagesShipping Market Report ChinaRadostin DechevNo ratings yet

- Container IzationDocument22 pagesContainer IzationMegha JhawarNo ratings yet

- Port Planning As A Strategic ToolDocument89 pagesPort Planning As A Strategic ToolVarun Patel100% (2)

- Introduction To Freight ForwardingDocument336 pagesIntroduction To Freight ForwardingAbdkarim Abbas KederNo ratings yet

- Handbook On Customs Clearance en FinalDocument102 pagesHandbook On Customs Clearance en FinalRitu Raj RamanNo ratings yet

- Freight Forwarder My ProjectDocument21 pagesFreight Forwarder My ProjectAnju Kurup75% (4)

- Freight ForwardingDocument48 pagesFreight ForwardingAnantha Regis0% (1)

- Changing Logistics - Freight Forwarders Evolve With TradeDocument5 pagesChanging Logistics - Freight Forwarders Evolve With Tradesutawijaya_masNo ratings yet

- Shipping Industry: Submitted byDocument32 pagesShipping Industry: Submitted byAkhsam PaleriNo ratings yet

- Freight Forwarding Service PDFDocument2 pagesFreight Forwarding Service PDFSLR Shipping Services100% (1)

- EAC Customs Valuation ManualDocument111 pagesEAC Customs Valuation Manualrodgerlutalo100% (1)

- Business Concept:: Key Success FactorsDocument5 pagesBusiness Concept:: Key Success FactorsRoxan AssemienNo ratings yet

- International Freight Forwarding: How U.S. & Canadian Importers Can Find A Better Freight SolutionDocument30 pagesInternational Freight Forwarding: How U.S. & Canadian Importers Can Find A Better Freight Solutionjas100% (1)

- Logistics and Transportation 3PL Vs 4 PLDocument23 pagesLogistics and Transportation 3PL Vs 4 PLRahul Singh100% (5)

- My Final Project ReportDocument115 pagesMy Final Project ReportTanju RoyNo ratings yet

- Freight Forwarding Final UCP Project 1Document20 pagesFreight Forwarding Final UCP Project 1madihahmadNo ratings yet

- Cargo Insurance: International Trade GuidesDocument6 pagesCargo Insurance: International Trade GuidesnimitpunyaniNo ratings yet

- Air Freight DocumentationDocument17 pagesAir Freight DocumentationSubhashis ModakNo ratings yet

- Freight Forwarding Chapter 3Document63 pagesFreight Forwarding Chapter 3Ajeet Krishnamurthy100% (2)

- Freight ForwarderDocument3 pagesFreight ForwarderSreekese PsNo ratings yet

- BMI Vietnam Freight Transport Report Q2 2014Document89 pagesBMI Vietnam Freight Transport Report Q2 2014BiểnLêNo ratings yet

- An Insight: Logistics in SCMDocument81 pagesAn Insight: Logistics in SCMSagarika Roy0% (1)

- Port Performance IndicatorsDocument21 pagesPort Performance Indicatorsrubyshaji96No ratings yet

- Container Terminal Management SystemDocument2 pagesContainer Terminal Management SystemPortNo ratings yet

- EY 2013 Shipping Industry AlmanacDocument492 pagesEY 2013 Shipping Industry AlmanacPriyadarshi Bhaskar100% (2)

- Business Concept:: Key Success FactorsDocument5 pagesBusiness Concept:: Key Success FactorsezrizalNo ratings yet

- CustomsDocument132 pagesCustomsAluma Muzamil100% (1)

- Eacffpc Ethics and Integrity Training ManualDocument48 pagesEacffpc Ethics and Integrity Training ManualKerretts Kimoikong73% (11)

- ReportDocument31 pagesReportGosaye ButunaNo ratings yet

- 222 - TPT - On Board Training To Foster Maritime LeadersDocument424 pages222 - TPT - On Board Training To Foster Maritime LeadersSolomon AginighanNo ratings yet

- East Africa Logistics Performance SurveyDocument42 pagesEast Africa Logistics Performance SurveyMike ZhangNo ratings yet

- Rehema Daniel ReportDocument24 pagesRehema Daniel Reportfabian mbigiliNo ratings yet

- Tounge TwistersDocument2 pagesTounge TwistersWilson De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Dos and Donts For MistakesDocument5 pagesDos and Donts For MistakesWilson De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- A Pound of ButterDocument1 pageA Pound of ButterWilson De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Behavior Engineering ModelDocument3 pagesBehavior Engineering ModelWilson De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- E-02 W-D of Power SystemDocument91 pagesE-02 W-D of Power SystemashleyNo ratings yet

- Ship RepairDocument27 pagesShip RepairMuhammed Razeem100% (1)

- Ui sc179 Rev2 pdf1513Document2 pagesUi sc179 Rev2 pdf1513gaty1234No ratings yet

- Siw - 05-09-2014Document20 pagesSiw - 05-09-2014SavisheshNo ratings yet

- Chief Mate Phase 1 Exam Paper Format - Naval Architecture 19052011Document3 pagesChief Mate Phase 1 Exam Paper Format - Naval Architecture 19052011Thapliyal SanjayNo ratings yet

- Ovpq - MV Seina 2Document10 pagesOvpq - MV Seina 2projectmasternigNo ratings yet

- C - 36 - Life Saving Appliances - Immersion SuitsDocument5 pagesC - 36 - Life Saving Appliances - Immersion Suitsandreaschrist1945No ratings yet

- (Bahasa Inggris Bisnis Pelayaran) - KALK Smt.8: Module Meeting 4Document9 pages(Bahasa Inggris Bisnis Pelayaran) - KALK Smt.8: Module Meeting 4anindyaNo ratings yet

- 1 DW1 MidtermDocument66 pages1 DW1 MidtermFrenziarho DoradoNo ratings yet

- Naga PelangiDocument7 pagesNaga PelangivijayndranNo ratings yet

- Deck Workbook Activity 9Document13 pagesDeck Workbook Activity 9rcmc ubasanNo ratings yet

- Passage Planning - Sharjah To Abu Dhabi 13 July 2010Document4 pagesPassage Planning - Sharjah To Abu Dhabi 13 July 2010Kunal Singh100% (2)

- Torm Marina Colision Con MSC CamilleDocument3 pagesTorm Marina Colision Con MSC CamilleSebastian UriarteNo ratings yet

- Indian Maritime UniversityDocument12 pagesIndian Maritime UniversityMohd AkifNo ratings yet

- Mooring Equipment and Wireropes Tails InspectionDocument37 pagesMooring Equipment and Wireropes Tails Inspectiondinar rosandy100% (1)

- Blank Vessel Safety Inspection Report - NPO FunctionDocument13 pagesBlank Vessel Safety Inspection Report - NPO Functioncaptafuentes100% (1)

- Form O 01 CertificatesDocument2 pagesForm O 01 Certificatesadel belkacemNo ratings yet

- Dockside Container Crane Workshop StructuralDocument30 pagesDockside Container Crane Workshop StructuralMAGSTNo ratings yet

- Mr. Emil AkumahDocument6 pagesMr. Emil AkumahLindsay PrattNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument7 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentPradeep PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Abrevieri CharterDocument16 pagesAbrevieri CharterBadea Ionel AndreiNo ratings yet

- Type of Vessels (Part 1) : Passenger ShipsDocument4 pagesType of Vessels (Part 1) : Passenger ShipsLobos WolnkovNo ratings yet

- Ship ParticularsDocument2 pagesShip ParticularsBurak YıldırımNo ratings yet

- KWave ReportDocument8 pagesKWave ReportDenys ShyshkinNo ratings yet

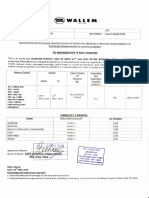

- Wallem: To Whomsoever It May ConcernDocument3 pagesWallem: To Whomsoever It May Concernshubham purohitNo ratings yet

- 4709 (P) /15 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA - Alaska - Aleutian Islands - Area To Be AvoidedDocument3 pages4709 (P) /15 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA - Alaska - Aleutian Islands - Area To Be AvoidedДмитрий БелецкийNo ratings yet

- Dry Berthing of Pleasure Boats Either For Maintenace or Complementary To Wet Berthing - Both The Technical and Financial Aspects (1980)Document22 pagesDry Berthing of Pleasure Boats Either For Maintenace or Complementary To Wet Berthing - Both The Technical and Financial Aspects (1980)Ermal SpahiuNo ratings yet

- ST T Haõng Taøu Soá Taøu Söùc Chôû (1000 TEU)Document5 pagesST T Haõng Taøu Soá Taøu Söùc Chôû (1000 TEU)yenleNo ratings yet

EACFFPC Freight Forwarding Module Training Manual

EACFFPC Freight Forwarding Module Training Manual

Uploaded by

Wilson De GuzmanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EACFFPC Freight Forwarding Module Training Manual

EACFFPC Freight Forwarding Module Training Manual

Uploaded by

Wilson De GuzmanCopyright:

Available Formats

THE EASTERN AFRICA CUSTOMS AND FREIGHT

FORWARDING PRACTICING CERTIFICATE (EACFFPC)

FREIGHT FORWARDING

OCTOBER 2012

THE FEDERATION OF EAST AFRICAN FREIGHT FORWARDERS

ASSOCIATIONS

In Collaboration with

EAST AFRICA REVENUE AUTHORITIES

With Support from

TRADEMARK EAST AFRICA (TMEA)

1|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

2|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

FOREWORD

Clearing agents in the East African Community (EAC) region play a vital role in

facilitation of trade particularly in regard to tax assessment and collection; this in

turn facilitates cargo movement and clearance from all requisite ports.

It is important to note that clearing agents who also double up as customs agents

in the region work very closely hand in hand with customs authorities to ensure

that trade in the region is facilitated.

Whereas customs officers have continued to be trained and refreshed developing

experts from their work force, the same has not been the case with their work

counterparts; the customs agents.

The need to train and capacity build the customs agents has never been more

necessary particularly after it has become imminent that the requisite knowledge

gap continues to widen.

The customs agents who also double up as freight logisticians have a wider scope

compared to customs officers creating need for more attention on their ability to

deliver professionally.

Most development partners have been focusing more on training customs officers

who apart from having better resources have better entry points. On the other

hand the clearing agents do not have a defined academic entry point or defined

resources for training.

This has resulted to a struggling clearing agent trying to catch up with the

knowledgeable counter parts in the customs, yet both MUST work together.

Customs agents originate documents that facilitate movement and clearance of

cargo culminating into errors that slow down the flow of business.

3|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Movement of cargo depends on how fast and perfect the documentation is done

by Customs agents that are verified by the respective customs authorities. A delay

in customs clearance increases the cost of doing business.

The intervention by Trade Mark East Africa (TMEA) came at the right time to

facilitate revision of EACFFPC training materials to enhance training and capacity

build the private sector with emphasis on the practicing customs agents in the

EAC region.

This support has not only focused on revision of the materials but also brought

together the private sector and the regional revenue authorities’ experts who

have worked together to come up with EACFFPC training materials acceptable to

both parties.

With these revised materials, the road to enhancing training for clearing agents

has earnestly begun.

4|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Curriculum Implementation Committee (CIC) is grateful to the National Revenue

Authorities and the National Freight Forwarders Associations for accepting to release their staff

and members to carry out the development of the training materials. CIC acknowledges the

FEAFFA secretariat for excellent co-ordination of the process of materials development and the

eventual compilation of the manuals.

Special thanks go to William Ojonyo who steered the team of experts that developed the

materials.

The tremendous support provided by our development partner, Trade Mark East Africa (TMEA),

cannot go unnoticed bearing in mind that they provided all financial support that culminated

into the development of the training materials.

A big THANK YOU to the following individual subject experts who took their valuable time and

wide experience in developing this FREIGHT FORWARDING MODULE- PORT CLEARANCE AND

FREIGHT FORWARDING OPERATIONS UNITS that have gone down the history lane.

1. John Kutyabami.

2. Walter Mndeme.

5|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

3. Josephine Nyebaza.

4. William Ojonyo.

5. Hussein Kiddedde.

6. George Otieno Ogutu.

7. Jean Marie Kinyarushatsi.

8. Benigne Manirakiza.

9. Stephen Ngatunga.

……………………………………………………………………………..

Lillian Umuhire Rugambwa

Chairperson

Curriculum Implementation Committee (CIC)

TABLE OF CONTENT

TABLE OF CONTENT ............................................................................................................................................ 6

FREIGHT FORWARDING MODULE ......................................................................................................................... 12

UNIT 1: PORT CLEARANCE .................................................................................................................................... 12

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................ 12

TOPICS: ................................................................................................................................................................. 12

Ports...................................................................................................................................................................... 12

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 12

Types of port .................................................................................................................................................... 13

Importance, Roles or Functions of Ports ...................................................................................................... 15

Port infrastructure ................................................................................................................................................ 16

Infrastructure ................................................................................................................................................... 16

Definition of infrastructure and its composition ......................................................................................... 16

Various Operations of superstructure and infrastructure ........................................................................... 16

Port clearance procedure ..................................................................................................................................... 18

Port charges .......................................................................................................................................................... 19

6|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Definition of Port Charges ................................................................................................................................ 19

Port Charges/ Pricing objectives ...................................................................................................................... 19

Basic approaches in establishing port tariff structure ..................................................................................... 20

Types of Port Charges ...................................................................................................................................... 21

Various parties involved and their roles in port clearance operations ................................................................ 30

UNIT 2: FREIGHT FORWARDING OPERATIONS ..................................................................................................... 34

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................ 34

TOPICS: ................................................................................................................................................................. 34

Freight forwarder ................................................................................................................................................. 34

Definition .......................................................................................................................................................... 34

Roles of a Freight Forwarder ............................................................................................................................ 34

Rights and Obligations of a Freight Forwarder to various parties ............................................................... 35

The Legal Framework of a Freight Forwarder .............................................................................................. 36

Work Environment of a Freight Forwarder .......................................................................................................... 39

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 39

Internal Environment ....................................................................................................................................... 39

Elements/Components of the internal environment .................................................................................. 39

External Environment ....................................................................................................................................... 40

Intervening Parties and how they influence the Freight Forwarding Industry ............................................ 40

Standard trading terms and conditions. ............................................................................................................... 41

Concepts of standard trading terms and conditions ........................................................................................ 41

Purpose of trading terms ............................................................................................................................. 42

TRADING GUIDELINES FOR FREIGHT FORWARDING BUSINESS ................................................................... 42

Documents and Processes of Freight Forwarding ................................................................................................ 43

Definitions ........................................................................................................................................................ 43

Types, sources and functions of various documents in Freight Forwarding .................................................... 44

7|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Carriage of goods .................................................................................................................................................. 60

Air Transport .................................................................................................................................................... 60

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 60

Types of Air Cargo ........................................................................................................................................ 60

Characteristics of Air Cargo .......................................................................................................................... 60

Regulatory Authorities in Air Transport ....................................................................................................... 60

Sea Transport ................................................................................................................................................... 63

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 63

Requirement for Efficient Sea Transportation ............................................................................................. 64

Criteria for Selection of Suitable Shipping Carrier or Service ...................................................................... 65

Advantages and Disadvantages of Sea Transport ........................................................................................ 66

Road Transport ................................................................................................................................................. 67

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 67

Advantages and Disadvantages ................................................................................................................... 68

Rail Transport ................................................................................................................................................... 70

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 70

Types of Rail Transport ................................................................................................................................ 70

Advantages and Disadvantages ................................................................................................................... 71

Pipelines ........................................................................................................................................................... 72

Multimodal/Intermodal Transport ................................................................................................................... 72

Definition ..................................................................................................................................................... 72

Terms commonly used in Multimodal transport ......................................................................................... 73

General Features/characteristics of Multimodal transport ......................................................................... 74

Infrastructure Requirements ....................................................................................................................... 76

Importance of MT ........................................................................................................................................ 77

Demerits of Multimodal transport ............................................................................................................... 77

8|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Operations and operators in Multimodal transport .................................................................................... 77

Parties in Multimodal transport................................................................................................................... 78

Documents used in Multimodal transport ................................................................................................... 78

FREIGHT RATE COMPUTATION IN VARIOUS MODES OF TRANSPORT .................................................................. 80

Definition .......................................................................................................................................................... 80

Theory of Freight Rates .................................................................................................................................... 80

Constituents of Freight Rates ........................................................................................................................... 82

Factors Influencing the Formulation of Freight Rates ...................................................................................... 85

Air Freight Rates and their Computation ..................................................................................................... 85

Handling of goods. ................................................................................................................................................ 87

General procedure for handling of goods ........................................................................................................ 87

Packing and Packaging ..................................................................................................................................... 87

Factors to consider when Packing ............................................................................................................... 88

Packaging types............................................................................................................................................ 89

Purpose/Function of a package ................................................................................................................... 90

Guidelines on the choice of Packaging ........................................................................................................ 90

The purposes of packaging and package labels ........................................................................................... 91

Marking and labeling ........................................................................................................................................ 93

Marking Practice .......................................................................................................................................... 93

Essential details on labels ............................................................................................................................ 94

Effects of poor marking and labeling ........................................................................................................... 95

Cargo Consolidation ......................................................................................................................................... 95

Definition/Concept ...................................................................................................................................... 95

Advantages and Disadvantages of Cargo Consolidation .............................................................................. 96

Break Bulking .................................................................................................................................................... 96

Definition ..................................................................................................................................................... 96

9|P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Illustrations on Break Bulk Operations ........................................................................................................ 97

Methods of handling Bulk Cargo.................................................................................................................. 99

Special goods .................................................................................................................................................. 100

Live animals:............................................................................................................................................... 100

Perishable Goods: ...................................................................................................................................... 101

Project Cargo: ............................................................................................................................................ 102

Dangerous Goods:...................................................................................................................................... 104

Warehousing/Cargo Storage .............................................................................................................................. 125

Introduction and Definition ............................................................................................................................ 125

Importance of warehousing ........................................................................................................................... 126

Types of Warehouses ..................................................................................................................................... 127

Types of Cargo/Goods stored in Warehouses ........................................................................................... 129

Characteristics of Ideal Warehouses .......................................................................................................... 130

Functions of Warehouses .......................................................................................................................... 131

Advantages of Warehousing ...................................................................................................................... 133

STORAGE ECONOMY ...................................................................................................................................... 134

Methods of handling cargo in a warehouse .............................................................................................. 135

Choice of equipment used in cargo handling ............................................................................................ 137

Containerization ................................................................................................................................................. 138

Introduction and Definition ............................................................................................................................ 138

Development of Containerisation .............................................................................................................. 139

Standardisation .......................................................................................................................................... 140

Types of Containers ........................................................................................................................................ 141

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 141

Types/Classification of Containers ............................................................................................................. 142

Container Markings /Container Identifications ......................................................................................... 145

10 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Container charges ...................................................................................................................................... 148

Advantages and Disadvantages of containerization .................................................................................. 149

Basis of International trade and transport ......................................................................................................... 149

Definition and History .................................................................................................................................... 149

Rules for Any Mode(s) of Transport ............................................................................................................... 150

Rules for Sea and Inland Waterway Transport .......................................................................................... 152

Previous terms from Incoterms 2000 that was eliminated from Incoterms 2010 ......................................... 154

References for Incoterms........................................................................................................................... 155

CASE STUDIES ..................................................................................................................................................... 155

REFERENCES........................................................................................................................................................ 160

11 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

MODULE 2: FREIGHT FORWARDING MODULE

(TIME: 80 HOURS)

Module description

This module is aimed at introducing trainees to Freight Forwarding Operations with a view of

enabling the trainees to competently execute freight forwarding services.

The Module will be divided into two learning Units namely;

1. Port Clearance

2. Freight Forwarding Operations

UNIT 1: PORT CLEARANCE

INTRODUCTION

This unit is intended to equip trainees with knowledge and skills that will enable them process

cargo through the port.

TOPICS:

PORTS

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, a Port was defined as a location on a coast or a shore containing one or more

harbors where ships can dock and transfer people and/or cargo to and from land e.g. Mombasa

Port, Dar-es-salaam Port, Port Bell, and Bujumbura Port.

With the dynamics of trade and transport today, Ports have become interfaces that facilitate

the loading and offloading operations of cargo and passengers as well as the change of the

12 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

mode of transport accordingly e.g. Magerwa in Rwanda, Multiple ICD in Uganda, Jomo Kenyatta

International Airport, JK airport in Tanzania, and Garreroutiere in Bujumbura.

TYPES OF PORT

Ports should be classified based on the following;

A. Classification of Ports based on Physical Locations

Sea/Lake/River Ports

These types of ports are located adjacent to the sea, lakes or rivers.

They facilitate transfer of cargo and people from land to sea transport and vice versa.

Airports

An Airport is a place where planes land and take off. In addition to the airports also handle

people and cargo. They are commonly found adjacent to water bodies.

Dry Ports

They are cargo centers located inland. They may be seen as extensions of seaports

Their main purpose is to bring services closer to the customers as a means of decongesting and

improving the efficiency of the sea ports. They are linked to seaports by road, rail or inland

waterways. Examples: ISAKA, KISUMU, ICD, MAGERWA

B. Classification of Ports based on Ownership

State owned

These are common user ports, owned entirely and are under the jurisdiction of the

government. The Government appoints a Board of Directors to run the port on its behalf. These

ports are established under an act of Parliament and incomes generated belong to the

13 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Government, which has direct control of its capital expenditure. Governments consider these

facilities to be of national importance. Examples of State owned ports are: the port of

Mombasa and Dar-Es-Salaam

Municipal Owned Ports

These ports are owned and managed by the local authorities who undertake construction and

maintenance of the facilities. Example: Port of Rotterdam

Private Ports

Private ports are owned and operated by private Companies. In some cases, the Government

may own some shares for purposes of control. Most of private ports specialize in handling

specific commodities e.g. break bulking. Private ports are common in USA and Europe, it is

anticipated that Kibuye may become a private port for handling Methane Gas terminal.

These types of Ports are characterized by a professional and efficient management system and

are very flexible in their procedures for operations as they are profit oriented.

C. Classification of Ports based on Services rendered

Free Ports

Free Ports operate in an environment free of Government taxes. Facilities offered here include

warehousing, industrial plants, banking and various support facilities. Traders import and sell

goods within the port without paying duty Dubai and very soon Rwanda.

Container Ports

Container Ports specifically handle container vessels and containers like in Kenya and

Dar-es-salaam they have specific container terminals, Singapore and also Inland Container

depots (ICDs) like Nairobi ICD.

14 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

General Cargo Ports

General Cargo Ports are ports that handle multiple types of goods. Examples of these ports

include Magerwa in Rwanda, Kenya Ports Authority Berth number 1 – 10 in Mombasa and Berth

number 1-8 in Dar-es-salaam.

Gas and Liquid Product Ports

These are specialized ports for handling gas and liquid products. Examples of such ports include

Dar-es-salaam, Shimanzi in Mombasa and Gatsata in Rwanda.

IMPORTANCE, ROLES OR FUNCTIONS OF PORTS

In general, Ports are used for gathering huge amounts of goods both for local, regional and

international needs.

Specific importance, roles or functions may include;

Loading and offloading of cargo

International Trade Facilitation

Revenue collection

Immigration Control

Embarking and disembarking of passengers

Limitation of International trade crimes

Economic contribution to the country

Creation of Employment and

Facilitation of the supply chain

Port as hub- country entry and exit point

15 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Note: The Trainer should introduce to the trainee the Port Layout of a specific country.

Duration: 4 hours

PORT INFRASTRUCTURE

INFRASTRUCTURE

DEFINITION OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND ITS COMPOSITION

Infrastructure can be defined as anything that facilitates the production of services and goods

for example roads are important because they help in transporting goods and distributing them

to the market.

Infrastructure in some other context may also include hospitals, schools and various other basic

social services.

In the context of the Port, we can divide Infrastructure into two categories namely

Superstructure and Infrastructure.

Superstructure may include port equipment, cargo handling equipment like fork lifts, pallets,

cranes, excavators etc.

Infrastructure may include buildings, roads, information technology, hospitals, police centres,

etc. and Security Equipment.

VARIOUS OPERATIONS OF SUPERSTRUCTURE AND INFRASTRUCTURE

16 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Container handling equipment

Ship to shore gantries (SSGs): These are overhead cranes used to handle containers into and

from the ships. SSGs are mounted and move on rails which run along the berth. They are

equipped with twist locks which fit into the container corner pockets and automatically lock

before the container is lifted.

Rubber tyred Gantries (RTGs): As the name implies unlike the SSGs that move on rails, RTGs

move on rubber tyres. Their functions are similar in every respect to the SSGs but are used in

the yard to load or offload trucks (terminal handling).

Rail Mounted Gantries (RMGs): These are also similar to SSGs and RTGs but are mounted on

rails and are used to handle containers at rail terminals.

Top Loaders and Reach Stackers: These are custom made four wheeled trucks with telescopic

lifting arms, extendable vertically in the case of top loaders and horizontally in the case of reach

stackers. They are also equipped with twist locks and locking mechanisms similar to the SSGs,

RTGs and RMGs.

Empty Container Handlers: These are similar to top loaders and reach stackers in construction

but are designed to lift empty containers.

Forklift Trucks: These use their forks to lift containers. They are designed to lift varying

tonnages.

Terminal Tractors: These are custom built heavy duty trailers used to transfer containers within

the port and on Ro/Ro vessels.

Pallets: Pallets are considered as handling equipment. The use of pallets is regulated by a

Convention from Commonwealth called: Commonwealth Handling and Equipment Pool (CHEP)

whose standards are 40’’ x 48’’ made in timber. Pallets facilitate the handling movement and

17 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

ensure an easy location and identification. The first pallets were tested used and registered in

1945 in Australia.

Infrastructure

Roads and maneuverability ways: Roads and maneuverability ways enable faster movement of

cargo within the port and also to and from the port. They must be tarmacked, stone paved and

strong enough roads able to sustain the heavy equipment within the port and avoid slow

movement of cargo to and from the port.

Buildings: Ports should have buildings that encompass administrative offices for customs,

police, port authorities, bureau of standards, banks, hospitals, accommodation etc.

Security Equipment

The ports should have sufficient security equipment to secure the ports and cargo depending

on the level of security. These may include security cameras, surveillance boats, alarms,

electrical fences, security radios etc.

Duration: 2 hrs.

PORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURE

Port Clearance is part and parcel of customs clearance which focuses on how goods are

inspected, paid for respective port dues and how the goods move in and out of the port area.

18 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Different ports have different clearance procedures depending on the level of automation

particular ports have reached.

Some other ports use manual systems whereby all procedures involved are handled manually

with more paper work involved such as use of declaration dispose order (D & DO), port revenue

invoice, gate passes, cargo/container interchange and cargo release notes while, other ports

use semi manual systems where by some procedures are automated and others are not.

Port of Dar-es-salaam are in the final stage of full automation where they have established a

web based cargo clearance system where Clearing Agents in line with Port community system

can clear port cargo through their offices.

The Trainer should expose students to the existing port clearance systems in specific countries

for Inland ports – CFS, Lake Ports, Dry ports, Airports,Sea ports,Border posts and other parties.

Duration: 2 hrs.

PORT CHARGES

DEFINITION OF PORT CHARGES

The Port Cargo Tariff is the total charges paid at the port by the cargo owner and ship owner for

services rendered in respect of that cargo or ship. It does not matter what type of port it is

these charges will always attach to cargo or ship passing through a port.

These charges are normally based on unit tonnage and unit volume but they may also be value

related (advalorem), or related to the nature of the cargo, such as passengers, live animals,

dangerous cargoes.

PORT CHARGES/ PRICING OBJECTIVES

19 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

In formulating port charges/pricing policies and establishing tariffs, ports generally endeavor to

incorporate the following pricing objectives;

a) To promote the most efficient use of the facilities: A principal objective of port pricing is

to ensure that port facilities are used in the most efficient manner. The pricing system

can influence the utilization of assets particularly when the demand for the services is

price elastic. When demand for a service is inelastic, other measures, generally more

authoritative than pricing, have to be found;

b) To retain the benefits resulting from investment within the country: An objective of

port pricing of particular interest for ports in developing countries is to establish

charges at a level that tends to retain the benefits arising from port improvements

within the country;

c) To recover sufficient revenue to meet financial objectives: A third objective relates to

building up financial reserves to prepare for unexpected falls in revenue or rises in

costs. Nevertheless, the acceptable amount of the reserve may be limited, if other

more important objectives, for instance the improvement of the utilization of assets,

are to be achieved.

d) Other objectives of port pricing include minimizing total logistics costs from a national

point of view; providing an incentive to port users to improve their facilities and

services; and ensuring that the tariff is both practical and simple.

BASIC APPROACHES IN ESTABLISHING PORT TARIFF STRUCTURE

Among the considerable number of factors that should be taken into consideration, a review of

actual practices and expert literature suggests that ports should take note of the following

critical aspects:

a) Clarification of the relationship between port facilities and users: Although identifying

the users of port facilities is not usually easy, most of the payers can be identified under

the current tariff system. Any port tariff structure should establish a clear framework for

20 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

the relationship between the charges and the "who pays" factor and should provide

fairness and flexibility;

b) Prevention of double payment: To assist in understanding the relationship between port

facilities and relevant charges, the tariff structure should provide a one-to-one

relationship between facilities and port tariffs;

c) Price mechanisms to prevent congestion: Facilities in which there is no cost input at all

in the port areas should be exempt from charges. But congestion caused by 'free of

charge' in the port may occur when traffic increases to such an extent that the level of

traffic flow eventually becomes saturated. In that situation, congestion could be

prevented by introducing congestion prevention charges;

d) Simplification of port tariffs: It is a common phenomenon for ports to be faced with

continuous confusion on port charges and, therefore, a constantly increasing demand

for a simplification of the tariff structure. Approaches to achieve simplification include

reducing the number of charges and/or reducing the number of variables in the basis for

each charge.

TYPES OF PORT CHARGES

a) Stevedoring:

Stevedoring refers to the function/process of loading and discharging cargo from a ship.

Stevedoring costs should be directly related to the costs involved in handling commodities.

Stevedoring companies in many ports are characterized by the high level of variable costs, for

example, labor and a comparatively low level of fixed costs such as mobile plant, buildings.

Therefore, in stevedoring operations the marginal costs and average costs may be identical.

The stevedoring charge is usually levied per freight ton, metric ton, cubic meters or TEU of

cargoes. Stevedoring firms often reserve the right to calculate the charge on the volume or

weight of the cargoes. It is common for all cargoes to be divided into groups according to

various criteria and a uniform rate applied to each group.

21 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

b) Wharf age

Wharf age is a charge assessed by a shipping terminal/port when goods are moved through the

port location/dock/pier.

Wharf age is normally a cargo-related charge to recover the costs associated with the provision

of the basic infrastructure and superstructure of the port to facilitate the movement of cargo

from shipside to hinterland and vice versa. It includes the costs of providing roadways, railways,

quays, parking areas, transit shed facilities, police surveillance etc.

Similar to port dues, wharf age is charged by freight ton, metric ton, cubic meters or TEU, and

its differentiation unit is the type of cargo.

c) Pilotage

Pilotage is the process of guiding the vessel in and out of the port/harbor.

Pilotage arises in two areas: the seaway gaining access to the river estuary and the port area

itself. In many instances, the pilot service is compulsory.

The pilotage may be based on the GRT of the vessel or a charge per ship. In general, as the cost

of providing pilot service does not vary for different sizes of vessels, it is appropriate to charge

pilotage simply based on the vessel's port call. However, it can be differentiated by the location

where the pilotage starts and ends.

d) Berth Hire (Dock or Berth due)

This is a charge normally, related to the ship to recover costs with the berthing/anchorage of

the vessel and for the use of the berth for a stated period of time. It may include expenditure

on the provision, maintenance and operation of docks, maintenance of dredged depths

alongside and in the dock basin, fendering, provision of quays and facilities provided on the

quay apron.

22 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

The charging unit of the berth due is meter-hours, computed as the length of the vessel

multiplied by the hours that the vessel is at the berth. The unit of differentiation distinguishes

among the berths by their characteristics, such as alongside depth, back-up area and cargo

handling capacities.

e) Storage

This refers to the fee given by the Port Authority for late removal of cargo after a specified free

period. Storage Charge is charged per day per unit of measure/charges.

In most ports, there is a free period during which no charge is made for storage. Warehousing

charges apply to goods that need to remain longer in the port and are, therefore, transported

to special premises reserved for that purpose.

After the free period has expired, the tariff usually takes account of the length of stay of the

goods in the storage place. In some cases, this charge per unit of time, usually the day, remains

constant, regardless of how long cargo remains in storage after the given free period. However,

in many cases, the charge per unit of time increases with the length of time spent in storage in

order to discourage any abusive lengthy storage. This charge can be differentiated by type of

storage, such as open, closed or frozen storage and by different types of cargo.

f) Transit storage

This is the charge to recover the costs of the storage of transit goods in transit sheds or areas.

The temporary storage rates are usually set to minimize cargo dwell time and maximize

throughput.

The charging unit is the amount of storage occupied multiplied by the period of storage

measured in days. The storage can be differentiated based on the dwell time so as to charge

higher rates for an extended period of storage. Separate tariffs can also be used to distinguish

between open and closed storage and among different types of cargo.

23 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

g) Handling

This refers to activities involved in loading the cargo from the quayside to a truck for transfer to

the storage area and handling at the stack for loading onto the cargo Owners’ transport or

railway wagon for delivery. The port uses its workers and cargo handling equipment such as

forklift trucks, cranes, and stackers etc. to perform this function. The charges therefore relate

to the equipment and labor used.

h) Removal Charges

This refers to late cargo documentation charges/penalties. Each port has a different tariff and

allowable time before being charged. For example in Mombasa and Dar-es-salaam removal

charges apply after 7 days.

i) Towing

This service is usually optional. Occasionally, the towage tariff is included in another charge

such as pilotage.

Towage is usually based either on the characteristics of the ship or the tugs performing the

operation. Towing costs increase with the size of the tugboat used and the time of use.

Therefore, the common practice is to charge a towage per hour and to differentiate based on

the size of the tugboat used. However, in some cases it is charged as a fixed rate irrespective of

the time taken for the operation and differentiated by the vessel's type and size.

j) Mooring/unmooring (berthing/unberthing)

This is a specific tariff applied for berthing/unberthing and mooring operations. This tariff is

charged simply by the vessel movement, but can be differentiated by the vessel's size measured

in Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT), Net Registered Tonnage (NRT) or some combination of

length, beam, and draft.

24 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

k) Conservancy and port dues

It is common to establish a charge to recover the cost incurred in providing the facilities and

services which are necessary to ensure the safe navigation of vessels within the area under the

port's jurisdiction. It may include dredging, the provision of breakwaters, training walls,

navigational aids and harbor surveillance facilities, but usually excludes the costs of providing

pilot and tow services which are charged by separate tariffs.

Conservancy is a port charge which is levied for the utilization of general nautical facilities in the

approaches to the port (i.e., outside the port area), whereas port dues are levied for the

services or utilization of facilities within the port, including channels, vessel traffic service,

emergency fire services, breakwaters, pollution control and marine security.

Port dues on ships are based on the type and size of the vessels. The charging units would be

the carrying capacity of the vessel measured in gross registered tonnage (GRT), net registered

tonnage (NRT) and deadweight tonnage (DWT) or some combination of length, beam and draft,

and the unit of differentiation should be the type of the vessel.

l) Other charges

Lashing or Unlashing:

In some ports, the ship may contract workers from outside the port to lash or unlash cargo on

board the vessel. In other ports all such functions are undertaken by the port itself, in which

case this cost is transferred by the port to the cargo owner

Security:

Certain cargoes, for example explosives, although not normally stored inside the port may

require security guards. A security charge is therefore applicable.

25 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

From July 2003 ports are required to comply with and enforce international security standards

according to the International Ship and Port Security Code (ISPS). Shipping lines levy a security

charge in respect of all containers to meet the additional costs due to compliance with the ISPS.

Transfer charges:

Transfer charges relate to the activity of moving cargo from the quayside to a storage stack and

vice versa during discharge or loading. Another form of transfer is where the cargo owner may

request the port to carry out activities outside the normal procedures. In the port of Mombasa,

for example, transfer charges apply when a consignment is shifted within the port at the

request of the cargo interest, such as positioning of containers for survey, weighing, customs

verification etc. Because resources are used, the port levies additional charges to meet the

additional costs.

26 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

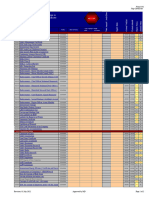

Port charges can be categories according to various service groups as illustrated in table

below:

Service Component/ Charging

group system

type of service

Basis Units Payee Recipient

Navigation Shipping

Port dues Size of ship GRT Port operator

line

Size of ship GRT Shipping Port/Pilotage

Pilotage

Time Hours line Association

Tug time involved Number Shipping Port/

Tug services

Size of ship GRT line Tug owner

Mooring/unmoo Shipping

Size of ship GRT Port operator

ring line

Shipping

Ancillary services Various Various Port operator

line

Berth Time of ship

Hours Shipping

Berth hire alongside Port operator

GRT line

Size of ship

Volume/weight/siz

Wharf age Tons/ Consignee/ Port operator

e

27 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Service Component/ Charging

group system

type of service

Basis Units Payee Recipient

of cargo TEU/㎥ Consignor

Shipping

Ancillary services Amount consumed Various Port operator

line

Cargo Tons/

Volume/weight/siz Shipping Provider of

operations Stevedoring

e of cargo TEU/㎥ line service

Volume/weight/siz

Tons/ Consignee/ Provider of

Wharf handling e

TEU/㎥ Consignor service

of cargo

Volume/weight/siz

Tons/ Consignee/ Provider of

Extra-movement e

TEU/㎥ Consignor service

of cargo

Volume/weight/siz

e

Special cargo Unit Shipping Provider of

of cargo

handling Types line service

Type of special

handling

Storage Time Tons/ Consignee/ Provider of

28 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Service Component/ Charging

group system

type of service

Basis Units Payee Recipient

service

TEU/㎥ Consignor

Days

Tons/

Volume/weight/siz

Packing/unpacki TEU/㎥ Shipping Provider of

e

ng line service

of cargo Unit

type

Equipment/servi

Hours of use by Equipment/

ce/ Hours Stevedore

item services owner

facility hire

Other Real estate,

Business licensing,

management Various Various Hirer Port operator

services and

consultancy etc.

Lease Dedicated costs Lease area Various Lessee Port operator

Rental charge Lease area Various Lessee Port operator

Duration: 6 hrs.

29 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

VARIOUS PARTIES INVOLVED AND THEIR ROLES IN PORT CLEARANCE OPERATIONS

The illustration below shows the intervening parties involved in port clearance operations;

Food and Drug

Authorities

Bureau of

standards

Freight forwarding Road, Airways

Industries & Railway

transport

Port (truckers)

Authorities

Customs Shipping lines

Authorities

a) Port authorities

Port Authorities are entities mandated to operate and manage the ports. They are usually

government departments or agencies e.g. Kenya Ports Authority (KPA), Exploitation du Port de

Bujumbura (EPB) and Tanzania Port Authorities (TPA). Physical inspection of goods is done

within the ports by customs or other authorities involved in controlling international cargo flow.

Port Authorities act as custodians of goods before clearance to export or import.

b) Customs

30 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Customs department is one of departments under Revenue authority charged with control of

movement of goods, coming in and going out of the country. An efficient and effective Customs

administration is key for facilitating trade and investment and, hence, growth. While the core

roles and responsibilities of Customs administrations throughout the world have remained

essentially the same for many years, the manner in which individual Customs administrations

discharge these roles and responsibilities and the relative priority afforded to each has changed

significantly in recent times. The drivers for this change are;

Heightened international awareness and quantification of the high transitional costs

associated with inefficient, time consuming and outdated border formalities;

Increased investment by the private sector in modern logistics, inventory control,

manufacturing and information systems, leading to increased expectations for prompt

and predictable processing of imports and exports;

Greater policy and procedural requirements associated with the implementation of

international commitments;

Increased regional and international competition for foreign investment;

Proliferation of regional trading agreements which significantly increase the complexity

of administering border formalities and controls; and

Increased awareness of the importance of transparency, good governance and sound

integrity within Customs;

31 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Customs Authorities are the ones who license, control and give guidance to customs agents on

matters related with the clearance of the goods. In fact, most of the documents are used by

clearing agents to declare and clear goods.

c) Carriers/shipping lines

Carriers/shipping lines own the different modes of transport e.g. vessels, aircrafts, trucks etc.

While freight forwarders are considered as architects of transport, they obtain this service of

moving the cargo from one place to another from the carriers. Cargo manifests are generated

by carriers and will be required for the clearance procedure. They also issue delivery orders.

d) Bureau of standards

Bureau of Standards (BS) provides ISO certification through various laboratories and provides

quality assurance and compliance certification of international standards. It also contributes to

export growth by providing certification of exports commodities such as coffee, tea, and fish for

consumption abroad. Bureau of Standards staffs move across various clearance points to check

compliance of the imported and exported goods to the pre described international acceptable

standards to the particular country or region. The performance of BS to some extent hinder fast

clearance of goods as to some extent is not well coordinated with other players in clearance

process.

e) Food and Drugs Authority-FDA

FDA is a regulatory body responsible for controlling the quality, safety, and effectiveness of

food, drugs, cosmetics and medical devices imported into the region. FDA was established by

combining two legacy agencies; the Pharmacy Board and the Food Control Commission. Freight

Forwarders’ must have approval from FDA before final release of cargo under this category.

32 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

f) Shipping agents

Shipping Agents are shipping line representatives who ensure that the interest of shipping lines

is met. They are intermediaries when freight forwarders’ need to book space on the carriers or

any other related activity to movement of cargo. Clearing Agents receive order to collect their

goods from ports through shipping agents. Also when Clearing agents process exports they

have to book the ship space through these shipping agents.

g) Truckers

Truckers provide transport services to send the cargo to and from ports to the owner of the

goods through truckers. Clearing Agents when contracting with these third parties on behalf of

the owner of the goods, they must make sure that standard trading conditions are compiled to

that particular place.

Duration: 2 hrs.

Delivery Mode:

The learning unit will be delivered through a series of lectures, case studies and seminars.

Trainees are required to attend lectures and associated seminars.

Delivery: Lectures: 16 HOURS

33 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

UNIT 2: FREIGHT FORWARDING OPERATIONS

INTRODUCTION

This unit is intended to equip the trainees with the knowledge and basic skills of freight

forwarding operations.

TOPICS:

FREIGHT FORWARDER

DEFINITION

A freight forwarder undertakes many complex activities and is known by several names in the

industry each depending on the range of services provided and country of origin.

Some of the alternative names include forwarding agent, freight broker, freight agent, and

ocean transport intermediate (OTI), Freight Forwarding agent, customs agent, Third party

logistics, Fourth party logistics, Economic Operator and Freight logistics.

In Uganda they are known as clearing agents, or customs Agents which basically mean a freight

forwarder.

ROLES OF A FREIGHT FORWARDER

Roles of a freight Forwarder include but are not limited to;

Arranging storage and shipping of merchandiseon behalf of its shippers.

Tracking inland transportation,

Preparation of import and exportdocuments, warehousing for purposes of Tax

computation and collection.

Bookingcargo space,

Negotiating of freightcharges,

Freight consolidation,

34 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Cargo insurance

Freight forwarders sometimes ship goods under their ownbills of lading or air

waybills (called house bill of lading or house air waybill) to their agents or associates

at the destination.

Freight Forwarders can also do consolidation/deconsolidation, and freight collection

services on commission from the carrier(Shipping line)

RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS OF A FREIGHT FORWARDER TO VARIOUS PARTIES

Customs:

East Africa Customs Management Act (EACMA) 2004 which regulates customs operations in

East Africa recognizes the freight forwarder where a customs agent is to be licensed by the

commissioner of customs to make preliminary documentation on behalf of customs for

purposes of tax collection.

The licensed agent is expected to;

Make accurate declarations for purposes of customs tax collection.

Correct routing of cargo from origin to destination.

Re-export with compliance strictly in line with requisite customs formalities.

Ensure that correct taxes are paid to customs prior to cargo release and delivery to the

Consignee.

Importers and exporters:

Freight Forwarders also have rights and obligations to Importers and exporters. They act as

agents of shippers and consignees in regard to facilitation and processing of cargo clearance

from customs areas.

They also advice the shipper correctly on all his obligations.

Make correct declarations on behalf of the importer, shipper/exporter

35 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

Collect all requisite dues payable on behalf of all institutions e.g., Customs, Bureau of

standards, Ports authorities etc.

Ensure that funds collected are used specifically for purposes of collection in the goods

therein.

Ensure that the goods are delivered safely to the consignee.

Other Parties:

A freight forwarder by virtue of being a customs agent and on the other hand an agent of the

shipper/ exporter/ importer has to interact with other parties during the process of clearance

of goods that may include but not limited to government agencies and ship agents.

Specific Roles;

Ensure conformity on regulations and or restrictions as may be determined by the

Government agencies. (Trainer to give examples)

Ensure that requisite documents are lodged on time with other trade logistic

interveners like ship agents, container freight stations etc.

Collect such documents as may be issued by interveners.

(Reference: Guide to international logistics by Singapore logistics association)

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF A FREIGHT FORWARDER

Locally (EAST AFRICA):

At regional level, at the moment we do not have any laws tailored specifically for the freight

forwarder, however, we have some laws that we can employ for to our benefit.

The East Africa Customs Management Act 2004, which regulates customs operations in East

Africa.

36 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

The Agency law under commercial law sets out the relationship when an agent is authorized to

act on behalf of another called a principal.

It talks about the liability of an agent to the third party, principal and vice versa to mention but

a few.

At International Level:

THE HAGUE VISBY RULES:

As amended by the Brussels protocol 1968, these laws govern the carriage of Goods by sea and

are employed by the shipping lines on their bills of ladings under contract of carriage.

They define who the carrier is, the consignee, shipper etc. They spell out the liability of the

carrier and the time allowed reporting loss and damage to the goods while under the custody

of the carriage.

e.g. In Article III section 6 the article talks about the reporting the loss , damage to the good in

writing to the carrier at the port of discharge immediately at time of removal of the goods at

delivery or when such damage is not immediately apparent with 3days.

HUMBURG RULES (UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON CARRIAGE OF GOODS BY SEA

1978).

They define the carrier, shipper, consignee etc.

Application:

Applied when the port of lading is in a contracting state.

Applied when the port of destination is in a contracting state. They are applied

regardless of the nationality of the ship, consignee, and shipper.

They are not applied to charter parties (renting a ship for your personal or business use)

unless if a Bill of Lading is issued –it will apply.

37 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

They are applied if for every shipment in the case where you have been contracted for a

series of shipments in the future. Just like in the Hamburg rules, these rules talk about

the time given to report in writing the loss and damage to the goods to the carrier,

however, under these rules, notice should be given with 1 day of delivery and 15 days

when the loss and damage is not immediately apparent. PART V. CLAIMS AND ACTIONS

Article 19:1 & 2

WARSAW CONVENTIONS:

As amended at The Hague, 1955 and by protocol no. 4 of Montreal, 1975

These laws apply to the carriage of goods by air in regards to persons, baggage and cargo

transported by air. For example in Article 17 & 18, the carrier is liable for the loss & damage to

person, cargo and baggage under the contract of carriage. INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER OF

COMMERCE (ICC RULES):

Also referred to as Incoterms they spell out the responsibilities, obligations of the buyer and the

seller in an international sales contract.

In some of these incoterms like DDP (Delivered Duty Paid), the buyer is responsible for shipping,

clearance and delivery of the goods at a named place of destination and therefore will engage a

freight forwarder to execute this contract.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the freight forwarder if ignorant of the law can lead to great loss to the freight

forwarder (agent) and the client not to mention a commercial suit. As the saying goes ignorance

is no defense.

Duration: 4 hours

38 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

WORK ENVIRONMENT OF A FREIGHT FORWARDER

INTRODUCTION

“A freight forwarding business operating Environment” is the atmosphere within which the

organization operates.

The factors within such atmosphere will go a long way in influencing directly or indirectly the

pattern of organizational performance of a freight forwarder either negatively or positively.

There are two types of organizational environment being the internal and external

environment.

INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

Internal Freight Forwarding Environment is simply defined as the aggregate of all inside factors

that influence the operations and performance of an organization from within.

ELEMENTS/COMPONENTS OF THE INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

Organizational guidelines

Freight Forwarding Organizations should have written documents as guidelines or corporate

charters, by-laws, Standard Operating Procedures (SOP).

These guidelines spell out the organizations stand points. All Managers in these organizations

are directed by what these documents guide.

Organizational Rules

An organization must develop rules pre-determined to place limits on what an organization

must abide by.

39 | P a g e

Freight Forwarding module

For instance a policy specifying that all organization’s cleared cargo must be accompanied by a

letter headed; signed and endorsed delivery note by the consignee must be obeyed to the

latter.

A rule specifying that employees must follow the chain of command upwards in seeking redress

to a grievance limits the lower staff/employees to go straight to top management for redress.

(Trainer to give more examples)

Remember that there may be many unwritten rules of the organization that dictate the way

things are done or handled in an organization, for instance an unwritten rule that all staff must

put on company T shirts with logos on every Friday becomes a rule that must be followed by all

staff.(Trainer to give more examples)

Organizational Structure

Freight forwarding organization structure should be well organized from top to bottom with

specific outlined roles and duty with clear cut reporting chains.

EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

External Environment for freight forwarding organization can be defined as the interventions

from outside the organization which are normally beyond their control.

INTERVENING PARTIES AND HOW THEY INFLUENCE THE FREIGHT FORWARDING INDUSTRY

Political instability that would divert the normal business routine

Trade monopoly from influential competitors in the supply chain management eg