Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Epidemiology Of: Milk-Borne Diseases

Epidemiology Of: Milk-Borne Diseases

Uploaded by

abdulqudus abdulakeemCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Evaluation and Prevention of Food Poisoning in A Catering EstablishmentDocument5 pagesEvaluation and Prevention of Food Poisoning in A Catering EstablishmentAlex Stryder40% (5)

- Personal Hygiene and Life Expectancy Improvements Since 1850 Historic and Epidemiologic Associations PDFDocument4 pagesPersonal Hygiene and Life Expectancy Improvements Since 1850 Historic and Epidemiologic Associations PDFMarko MojsilovićNo ratings yet

- STM 211 Prat.Document74 pagesSTM 211 Prat.abdulqudus abdulakeem100% (3)

- STP 221 TheoryDocument97 pagesSTP 221 Theoryabdulqudus abdulakeem100% (4)

- On The Safety of Raw Milk (With A Word About Pasteurization)Document69 pagesOn The Safety of Raw Milk (With A Word About Pasteurization)kirti1111No ratings yet

- Sardi - Not Milk!Document9 pagesSardi - Not Milk!Rey JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Mother's Milk and Infant Death in Britain, Circa 1900-1940, Atkins, P.J. (2003) Anthropology of Food No 2 Http://aof - Revues.org/document310.htmlDocument8 pagesMother's Milk and Infant Death in Britain, Circa 1900-1940, Atkins, P.J. (2003) Anthropology of Food No 2 Http://aof - Revues.org/document310.htmlPeter J. AtkinsNo ratings yet

- Vas Avada 1988Document8 pagesVas Avada 1988Shatumbu WilbardNo ratings yet

- L.loaf - The Truth About Vaccination and Immunization (1951)Document35 pagesL.loaf - The Truth About Vaccination and Immunization (1951)BobNo ratings yet

- Puerperal Sepsis WMSD Chapter7 RefDocument9 pagesPuerperal Sepsis WMSD Chapter7 RefMuhammad JulpianNo ratings yet

- Unpasteurized Milk: A Continued Public Health Threat: InvitedarticleDocument8 pagesUnpasteurized Milk: A Continued Public Health Threat: InvitedarticlecezalynNo ratings yet

- ACH-REF-10 Bacteria Associated With Foodborne DiseaseDocument25 pagesACH-REF-10 Bacteria Associated With Foodborne DiseaseJeffreyNo ratings yet

- Pathogens 10 01341Document10 pagesPathogens 10 01341IsabelNo ratings yet

- Emerging Issues in Water and Infectious Disease-WHO 2003Document24 pagesEmerging Issues in Water and Infectious Disease-WHO 2003Orangel RocaNo ratings yet

- Foodborne Agents Causing IllnessDocument175 pagesFoodborne Agents Causing IllnessFrank FontaineNo ratings yet

- Foorborne DiseasesDocument10 pagesFoorborne DiseasesAudi Murphi SimanjuntakNo ratings yet

- Safety: Public Health Significance of Foodborne IllnessesDocument16 pagesSafety: Public Health Significance of Foodborne IllnessescysautsNo ratings yet

- Chapter one-WPS OfficeDocument2 pagesChapter one-WPS OfficedavidtitangohNo ratings yet

- Rimsa12 18-EDocument14 pagesRimsa12 18-EEnnur NufianNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 and Its Global Impacts: Essay For Css/Pms (2880 WORDS)Document28 pagesCovid-19 and Its Global Impacts: Essay For Css/Pms (2880 WORDS)Agha Khan DurraniNo ratings yet

- 1517-Article Text-5844-1-10-20081031 PDFDocument6 pages1517-Article Text-5844-1-10-20081031 PDFJohn Bryan JamisonNo ratings yet

- Ama Foodborne Illness OutbreaksDocument3 pagesAma Foodborne Illness OutbreaksJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- NCM 113 (Lec) Semifinals ModuleDocument5 pagesNCM 113 (Lec) Semifinals ModuleHelen GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Foodborne Botulism - Scalfaro2018Document6 pagesFoodborne Botulism - Scalfaro2018david ojNo ratings yet

- A 100-Year Review: Microbiology and Safety of Milk Handling: Transition To PasteurizationDocument19 pagesA 100-Year Review: Microbiology and Safety of Milk Handling: Transition To PasteurizationOmar PopocaNo ratings yet

- The 1918 "Spanish Flu" Only The Vaccinated Died - Rights and FreedomsDocument1 pageThe 1918 "Spanish Flu" Only The Vaccinated Died - Rights and FreedomsDavid ZuckermanNo ratings yet

- NatureMedicine Dec 2000Document2 pagesNatureMedicine Dec 2000paddyvzNo ratings yet

- Bacteria and VirusesDocument45 pagesBacteria and VirusesKringKring 47No ratings yet

- Introduction For Food SafetyDocument16 pagesIntroduction For Food SafetyEdi AshraffNo ratings yet

- Almond FluDocument41 pagesAlmond FlujayNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Effects On Livestock Production: A One Welfare IssueDocument16 pagesCOVID-19 Effects On Livestock Production: A One Welfare Issueyudi adinataNo ratings yet

- FDA Bad Bug BookDocument306 pagesFDA Bad Bug BookSaif Al-hazmi Al-KalantaniNo ratings yet

- Disease Transmitted Through MilkDocument12 pagesDisease Transmitted Through MilkSUTHAN100% (9)

- International Conference en Enfermedades Infecciosas Emergentes 2008Document262 pagesInternational Conference en Enfermedades Infecciosas Emergentes 2008Pablo RavettiNo ratings yet

- Personal Hygiene and Life Expectancy Improvements Since 1850: Historic and Epidemiologic AssociationsDocument4 pagesPersonal Hygiene and Life Expectancy Improvements Since 1850: Historic and Epidemiologic AssociationsOutlawHealthNo ratings yet

- Tendencia y Causas de La Mortalidad Materna en Chile de 1990 A 2018Document10 pagesTendencia y Causas de La Mortalidad Materna en Chile de 1990 A 2018Daani LagosNo ratings yet

- Reprint Of: Microbial Food Safety in The 21st Century: Emerging Challenges and Foodborne Pathogenic BacteriaDocument1 pageReprint Of: Microbial Food Safety in The 21st Century: Emerging Challenges and Foodborne Pathogenic BacteriaMario DavilaNo ratings yet

- Food Borne Diseases:: Dr. Amr El-Dakroury Dept. of Medical Commission Supreme Council of HealthDocument42 pagesFood Borne Diseases:: Dr. Amr El-Dakroury Dept. of Medical Commission Supreme Council of Healthhadi yusufNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking in Global Challenges Week 4 Global Challenge Focus: Infection Diseases, DR Kim PicozziDocument3 pagesCritical Thinking in Global Challenges Week 4 Global Challenge Focus: Infection Diseases, DR Kim PicozziBetania ArrochaNo ratings yet

- Mycobacterium Avium Subsp. Paratuberculosis in PowderedDocument9 pagesMycobacterium Avium Subsp. Paratuberculosis in PowderedDalonPetrelNo ratings yet

- Reviewer in CPHMDocument8 pagesReviewer in CPHMVianne TabiqueNo ratings yet

- History $ ContemporDocument10 pagesHistory $ ContemporVijith.V.kumarNo ratings yet

- Spanish FluDocument12 pagesSpanish FluВојин ДражићNo ratings yet

- A Disease of POORDocument16 pagesA Disease of POORTaruna KandpalNo ratings yet

- Introduction-to-Public-Health - Lecture 1Document42 pagesIntroduction-to-Public-Health - Lecture 1lsatkinsNo ratings yet

- tmpAB6C TMPDocument10 pagestmpAB6C TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Yersinia Enterocolitica, Is Common in Undercooked Pork. (Chit'lins, Anyone?) HepatitisDocument4 pagesYersinia Enterocolitica, Is Common in Undercooked Pork. (Chit'lins, Anyone?) HepatitisEdward McSweegan, PhDNo ratings yet

- 01 Urgent Information About Swine Flu PPT 2009/10Document4 pages01 Urgent Information About Swine Flu PPT 2009/10Oscar VilcaNo ratings yet

- Estudio de Brote Epidemiológico de Fiebre Tifoidea en ChileDocument10 pagesEstudio de Brote Epidemiológico de Fiebre Tifoidea en ChileChristopher VargasNo ratings yet

- A Socionomic View of Epidemic Disease A Looming Season of SusceptibilityDocument10 pagesA Socionomic View of Epidemic Disease A Looming Season of Susceptibilitybytestreams3400No ratings yet

- Microbial Quality and Safety of Milk and Milk Products in TheDocument37 pagesMicrobial Quality and Safety of Milk and Milk Products in TheWilson SilvaNo ratings yet

- Review: Recognition of The Challenge of DiabetesDocument9 pagesReview: Recognition of The Challenge of DiabetesJulia OlanNo ratings yet

- Special Article: Twentieth Century Nutrition: Public Health Nutrition and Food Safety, 1900-1999Document5 pagesSpecial Article: Twentieth Century Nutrition: Public Health Nutrition and Food Safety, 1900-1999annisa syahfitriNo ratings yet

- Bovine Mastitis An Evolving DiseaseDocument13 pagesBovine Mastitis An Evolving DiseaseIoana CriveiNo ratings yet

- The Amazing DeclineDocument26 pagesThe Amazing DeclineSuzanne HumphriesNo ratings yet

- History of Public Health 2 ND LectureDocument43 pagesHistory of Public Health 2 ND LectureAdam Ayman MukahalNo ratings yet

- Spanish FluDocument33 pagesSpanish FluMae AstovezaNo ratings yet

- Listeria Listeriosis and Food Safety Third EditionDocument894 pagesListeria Listeriosis and Food Safety Third Editionziza20 Ziza100% (1)

- Actividades de Salud Pública Veterinaria en La FAO Cisticercosis y EquinococosisDocument4 pagesActividades de Salud Pública Veterinaria en La FAO Cisticercosis y EquinococosisAndres TejadaNo ratings yet

- White Paper - The Dietary Cause, Prevention and Reversal of CO-VID-19 Pneumonia - Sixth Version - 2 - 04 - 21Document15 pagesWhite Paper - The Dietary Cause, Prevention and Reversal of CO-VID-19 Pneumonia - Sixth Version - 2 - 04 - 21George SingletonNo ratings yet

- Public Health and Bovine Tuberculosis: What's All The Fuss About?Document6 pagesPublic Health and Bovine Tuberculosis: What's All The Fuss About?api-87936233No ratings yet

- Processing of Specimens in Mycology LabDocument36 pagesProcessing of Specimens in Mycology Lababdulqudus abdulakeemNo ratings yet

- Dairy Farming in Nigeria: Past, Present and Future: July 2020Document6 pagesDairy Farming in Nigeria: Past, Present and Future: July 2020abdulqudus abdulakeem100% (1)

- Bahan+Ajar Introduction+to+the+BacteriaDocument9 pagesBahan+Ajar Introduction+to+the+Bacteriaabdulqudus abdulakeemNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Antibacterial Activities of Actinomycete Isolates Collected From Soils of Rajshahi, BangladeshDocument7 pagesResearch Article: Antibacterial Activities of Actinomycete Isolates Collected From Soils of Rajshahi, Bangladeshabdulqudus abdulakeemNo ratings yet

- Com 125 Intro To System Analysis and Design TheoryDocument125 pagesCom 125 Intro To System Analysis and Design Theoryabdulqudus abdulakeemNo ratings yet

- COM 215 Computer Packages II Practical BookDocument18 pagesCOM 215 Computer Packages II Practical Bookabdulqudus abdulakeemNo ratings yet

- Ijmra 11932Document12 pagesIjmra 11932abdulqudus abdulakeemNo ratings yet

- Lattice Energy The Born-Haber CycleDocument4 pagesLattice Energy The Born-Haber Cycleabdulqudus abdulakeemNo ratings yet

- Mixed Conditionals - Test-EnglishDocument1 pageMixed Conditionals - Test-EnglishMilica MilunovićNo ratings yet

- BD100IX0012 - B1 TR For Multiphase FlowMeterDocument29 pagesBD100IX0012 - B1 TR For Multiphase FlowMetervamcodong100% (1)

- Glee.s05e01.Hdtv.x264 LolDocument71 pagesGlee.s05e01.Hdtv.x264 LolraffiisahNo ratings yet

- Intermediate I. Lesson Plan Submittal. 2019Document56 pagesIntermediate I. Lesson Plan Submittal. 2019juan vNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Asynchronous Activity: Asean Literature April 21, 2021, WednesdayDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Asynchronous Activity: Asean Literature April 21, 2021, WednesdayPatricia ByunNo ratings yet

- CRM Project SynopsisDocument6 pagesCRM Project Synopsishairavi10_Scribd0% (1)

- Ica Long ExamDocument189 pagesIca Long ExamHannah Kimberly ArejolaNo ratings yet

- Mcmurray El Hipogeo SecretoDocument6 pagesMcmurray El Hipogeo Secretoclaugtzp-1No ratings yet

- The Roman Ruins in GuelmaDocument1 pageThe Roman Ruins in GuelmaSalah BessioudNo ratings yet

- Research in International Business and Finance: Badar Nadeem Ashraf TDocument7 pagesResearch in International Business and Finance: Badar Nadeem Ashraf TbouziNo ratings yet

- Republic of The PhilippinesdwwwwDocument13 pagesRepublic of The PhilippinesdwwwwGo IdeasNo ratings yet

- Spanish Pediatric Immunisation Reccommendation 2012Document23 pagesSpanish Pediatric Immunisation Reccommendation 2012agungNo ratings yet

- Reflective Journal GuidelinesDocument3 pagesReflective Journal GuidelinesAnaliza Dumangeng GuimminNo ratings yet

- International Human Resource Management - Syllabus - VtuDocument2 pagesInternational Human Resource Management - Syllabus - Vtumaheshbendigeri5945No ratings yet

- As You Like It - Oliver LinesDocument14 pagesAs You Like It - Oliver LinesDaniel NixonNo ratings yet

- Vasisthasana - Side Plank PoseDocument2 pagesVasisthasana - Side Plank PoseMIBNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Audit) : CAGE QuestionsDocument3 pagesAlcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Audit) : CAGE QuestionsAndrei GilaNo ratings yet

- Entrance Into Year 5 Writing and Reading Mark Scheme and LevelsDocument28 pagesEntrance Into Year 5 Writing and Reading Mark Scheme and Levelstae hyungNo ratings yet

- Arab TexDocument9 pagesArab TexKornaros VincenzoNo ratings yet

- SocivoDocument16 pagesSocivoSlobodan MilovanovicNo ratings yet

- Verbos Regulares e Irregulares en InglesDocument5 pagesVerbos Regulares e Irregulares en InglesmiriamNo ratings yet

- Catholic Essentials PP Chapter 6Document21 pagesCatholic Essentials PP Chapter 6LogLenojNo ratings yet

- Procedure For Management ReviewDocument3 pagesProcedure For Management ReviewSharif Khan100% (1)

- OpenMind 1 Unit 1 Grammar and Vocabulary Test BDocument3 pagesOpenMind 1 Unit 1 Grammar and Vocabulary Test BRubenNo ratings yet

- History of Trinidad 1Document6 pagesHistory of Trinidad 1Reynaldo RamsobagNo ratings yet

- Adsorption Isotherms: (Item No.: P3040801)Document7 pagesAdsorption Isotherms: (Item No.: P3040801)Leonardo JaimesNo ratings yet

- Bronkhorst 2017 Brahmanism-Its Place in Ancient India PDFDocument9 pagesBronkhorst 2017 Brahmanism-Its Place in Ancient India PDFrathkiraniNo ratings yet

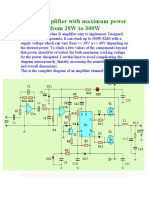

- Class D Amplifier With Maximum Power Adjustable From 20W To 300WDocument13 pagesClass D Amplifier With Maximum Power Adjustable From 20W To 300Wramontv032428No ratings yet

- MUDRA VIGYAN: The Science of Finger PosturesDocument11 pagesMUDRA VIGYAN: The Science of Finger PosturesArvind NadarNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarterly Long Test in Applied EconomicsDocument2 pages2nd Quarterly Long Test in Applied EconomicsKim Lawrence R. BalaragNo ratings yet

Epidemiology Of: Milk-Borne Diseases

Epidemiology Of: Milk-Borne Diseases

Uploaded by

abdulqudus abdulakeemOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Epidemiology Of: Milk-Borne Diseases

Epidemiology Of: Milk-Borne Diseases

Uploaded by

abdulqudus abdulakeemCopyright:

Available Formats

637

Journal of Food Protection. Vol. 46. No.7 Pages 637-649 (July 1983)

Copyright©. International Association 01 Milk. Food. and Environmental Sanitarians

Epidemiology of Milk-Borne Diseases

FRANK L. BRYAN

Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Centers for

Disease Control. Atlanta, Georgia 30333

(Received for pUblication November 22, 1982)

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

abundance of health hazards that were associated with in-

ABSTRACT

gestion of raw milk in the early 1900s until the end of

Secular trends in milk-borne diseases in the U.S.A. show World War n, Then, because most of the milk was pas-

numerous outbreaks associated with ingestion of raw milk in the teurized, outbreaks decreased dramatically.

early 1900s until the end of World War II. Diseases common in Reports of experimental milk pasteurization were just

this period, but no longer milk-borne, were typhoid fever, scarlet appearing in the public health literature in the early 1900s,

fever, septic sore throat, diphtheria, tuberculosis, shigellosis, and but the process did not come into common use for many

milk sickness. Milk-borne and milk-product-borne diseases rarely years thereafter. The first model milk ordinance recom-

reported somewhere in the world were botulism, Escherichia coli

mended by the U.S. Public Health Service, for instance,

enteritis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa enteritis, listeriosis, Clos-

was published in 1924 and a draft code followed in 1927.

tridium periringens enteritis, Bacillus cereus gastroenteritis,

Haverhill fever, Q fever, hepatitis A, poliomyelitis, toxoplas- From that time on, pasteurization for milk was stressed na-

mosis, histamine intoxication and hypertension. After most milk tionally. Since 1950, there have been reports of only a few

was pasteurized, outbreaks decreased dramatically. Milk-borne raw milk-associated outbreaks; but, such outbreaks still

diseases of contemporary importance in the U.S.A. are salmonel- occur, because some people prefer to drink raw milk.

losis, campylobacteriosis, staphylococcal intoxication, brucel- The percentage of reported outbreaks of milk-borne dis-

losis, and yersiniosis. These have usually been associated with in- ease by decade is shown in Table I, Several trends stand

gestion of raw milk, certified raw milk, home-made ice cream ouL During the period between the tum of the century and

containing fresh eggs, dried milk, pasteurized milk which WilS 1940, typhoid fever was the major milk-borne disease.

contaminated after heat processing, or either cheese made from Then after precipitous decline in two decades, no milk-

raw milk or cheese in which starter activity was inhibited during borne outbreaks of typhoid fever were reported during the

its manufacture.

sixties, the seventies, and early eighties, Streptococcal in-

fections (scarlet fever and septic sore throat) were the sec-

ond-most common cause of outbreaks reported during the

first three decades of the 1900s, but such reports dwindled

Throughout the years, epidemiologists, physicians and to extinction in the 1940s. Diphtheria, which accounted for

sanitarians in the United States have expressed concern a smaller share, declined until reports ceased in 1946,

about milk-borne and milk-product-borne diseases (8,31- As reports of outbreaks of these diseases waned, reports

40,54.58,115). Frequencies of reported outbreaks of of outbreaks of staphylococcal intoxication, nontyphoidal

milk-borne and milk-product-borne disease during the salmonellosis and diseases of unknown etiology gathered

1900-1981 period are shown in Fig. 11. Secular trends in impetus. Milk products (ice cream, dry milk, and cheese)

milk-borne (and milk-product-borne) diseases show the were the usual vehicles of these outbreaks. (The large

number of outbreaks reported in 1956 was due to 27 out-

breaks of staphylococcal intoxication from dried milk.)

IData in the Figure was extracted from the reviews by Trask (lIS).

Armstrong. and Parran (8). reports from the U.S. Public Health Service.

Salmonellosis and gastroenteritis of unknown etiology

Office of Milk Investigations (l925-1936). Domestic Quaral!line Division. dominated the 1970s. In the last of the 1970s, campylobac-

Sanitation Section (1937-1939). State Relations Division, Sanitation Sec- teriosis began to emerge as an important raw milk-borne

tion (1940-1943). Engineering Division. Milk and Food Section (1944- disease. The large percentage of outbreaks of unknown

1946). Division of Sanitation, Milk and Food Branch (1947-1949); Na-

etiology reported in the last few decades, almost certainly

tional Office of Vital Statistics-Reports by Dauer (31-40)-and surveil-

lance reports, reviews in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. and

included undetected outbreaks of campylobacteriosis. The

annual summaries about foodborne diseases by the Centerl s) for Disease relatively long gap between the report by Levy (75) and the

Control (I961-198Jj (22). later reports reflects the difficulty to recover Campylobac-

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION. VOL. 46. JULY 1983

638 BRYAN

80

o Raw milk or cream

BI Certified raw milk

70

Ili1 Milk, unspecified; most likely raw milk

£Xl Pasteurized milk

IDJ Oried (powdered) milk

51 Cheese

60 m Milk products. unspecified; malted

milk; milk formula

m Human milk

P»J Butter

• Ice cream, eggs frequently added

mJ Unknown

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

50

en

CIl

en

~

U

....0

Q) 40

..c

E

:::l

2

30

20

10

Year

10ata on specific vehicles, unavailable for the year 1950

20ata incomplete

Figure 1. Secular trends of milk-borne diseases by specific vehicle and year of occurrence, United States.

ter jejuni until laboratory procedures improved and con- for most of the ice cream-associated outbreaks (Fig. 1) dur-

cern about the problem was generated. ing the 1909 to 1925 period; staphylococcal intoxication

predominated from 1930 through the 1950s. Of the remain-

The types of milk and milk products that were impli- ing outbreaks, cheese and raw milk (including certified raw

cated as vehicles of outbreaks of specific milk-borne dis- milk) were often implicated as vehicles. The listing "milk,

eases during the 1970s are shown in Table 2. Ice cream, unspecified" refers, most likely, to raw milk; but, the re-

usually homemade and containing eggs, was the vehicle of ported data do not so specify. The pasteurized milk and

most of the outbreaks (usually of salmonellosis) reported chocolate milk were either improperly pasteurized or be-

during this period. Therefore, many of these should proba- came contaminated after being pasteurized. [For informa-

bly be omitted from the list because they would be better tion on recent milk-borne diseases that have occurred in

classified as egg-borne diseases. Typhoid fever accounted Canada, see data from the Health Protection Branch (4).]

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION, VOL. 46, JULY 1983

MILK-BORNE DISEASE 639

TABLE 1. Percent of reported milk-borne diseases by decade.

1900- 1910- 1920- 1930- 1940- 1950- 1960- 1970- 1980-

Disease 1909 1919 1929 1939 1949 1959 1969 1979 1982

Arizonosis

Botulism <1 1

Brucellosisa 8 4 9 1

Campylobacteriosis <1 3 40

Diphtheria 8 2 4 1

Escherichia coli

diarrhea

Haverhill fever <1

Hepatitis A <1 2

Histamine intoxication

Iron intoxication

Milk sickness <1

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

Petroleum poisoning 2

Poliomyetitis <1 <1 <1

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

infection <I

Q fever

Salmonellosis 3 2 7 21 28 41 50

Shigellosis 2 4 3

Staphylococcal

intoxication 8 26 50 30 5

Streptococcal

infections 14 15 18 27 8

Toxoplasmosis

Typhoid fever 78 80 68 50 17 3

Yersiniosis

alndividual cases not included, see Table 5.

MILK·BORNE DISEASES OF that of the 1971-1974 episode. This investigation impli-

CONTEMPORARY IMPORTANCE cated certified milk from the same dairy. Over 100 isola-

tions of Salmonella, including S. dublin, were made from

Salmonellosis milk produced by the dairy, and several hundred isolations

Milk-borne salmonelloses are common in those regions of Salmonella-including S. dublin-were made from cattle

of the world in which milk is neither pasteurized nor in the dairy's herds (30). (Outbreaks of campylobacteriosis

boiled. Many outbreaks of salmonelloses in the United also have been associated with milk from this dairy.)

States from 1965 to the present that have been summarized Increased isolations of Salmonella newbrunswick led

either in the professional literature or in official surveil- epidemiologists to make epidemiologic associations be-

lance reports are listed in Table 3. Either, raw milk or cer- tween ingestion of milk prepared from instantized dried

tified raw milk has usually been the vehicle, but pas- milk and 29 cases of salmonellosis (mostly infants) from

teurized milk, powdered milk and Cheddar cheese have 17 states (28). The same serotype was isolated from three

also been implicated. Marth (79) has reviewed salmonellae lots of the milk produced at a single processing plant. The

and salmonelloses associated with milk and milk-products. milk was heated during processing, but without either ther-

Certified raw milk produced at a single large dairy was mostatic or time controls to ensure pasteurization. The

ingested by 74 of 79 persons who became ill between April milk was then concentrated by a series of vacuum pan

1971 and March 1974 (70). Salmonella dublin was isolated evaporators before spray drying. The milk powder was

from all of the ill persons, 37 of whom had underlying de- then instantized (steam is applied to the powder and the

bilitating conditions. Fifty-nine (75%) of these persons agglomerate is dried). Samples of the product taken at vari-

were hospitalized and 16 (20%) died. S. dublin was iso- ous stages of processing indicated that the product most

lated from a sample of raw milk from a California dairy likely became contaminated in the instantizer. This piece

from which the ill persons obtained their milk, and sal- of equipment had several rough-surface welded joints,

monellae (but not S.dubUn) were isolated from cows of the numerous crevices and open seams, and contained numer-

dairy's herds. Milk from this same dairy was implicated as ous thin rods and divider plates. These all contributed to

the vehicle in two other outbreaks in 1958 and in 1964. build-up of caked powder in areas inaccessible to cleaning.

Investigation of a recurrence of S. dublin infections in The instantizer was wet-cleaned only weekly.

California during 1977-1979, disclosed a pattern similar to An epidemiologic investigation of an outbreak of Sal-

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION. VOL. 46. JULY 1983

640 BRYAN

TABLE 2. Milk and Milk products reported as vehicles of disease outbreaks, 1970-1979.

,:::

0

.~

"u '"

0)

,:::

':;i

0 .~

~ ell

,:::

0

.~

.5 0

'6 '2 u

';;]

.~

-;

u

';::

<l c'-' '"

0

'1'"5 .s ell

,:::

t>

..sl

<l

"u0

0 :9'"

.::1

'"....

'"or> '"

'{ii

.9

'" «en § 0-

8

,5

g

'2

0 ,:::

~

Product § >-. .~ 0

:S

0

,::: '" ::> .::> '80-

~ §-

<l .~ .!l 0

~

c::

E

-;

..<:i

0-

"'"8 ~

·c2

U

0- x e ,:::

-'Ci ~

"l

g

"l U" ~'"

v

>- .(

1:

iX:I ::c" 0

!-< ~ ::2 ,g ~ E-

Raw milk 3 2 7

Milk, unspecified 2 8 12

Certified milk 2 3

Pasteurized milk 2 2

Chocolate milk 3

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

Milk fonnula 1

Powdered milk 2 1 3

Butter 2 3

Whipped butter

Whipped topping

Cheese 10 14

Sour cream 1

Cheese puff

Milk shake mix 2 2

Ice cream 26 a 1" 12a 40a

Unspecified, dairy

product 1 2

Human milk 2 2

aEgg-borne rather than milk-borne in many outbreaks.

TABLE 3. Milk-borne arul milk-product-borne outbreaks of salmonellosis in the United States. 1965-1981.

Year Product State Number of References

cases Serotype

1965 Raw milk Washington 2 typhimurum (4)

1965-1966 Powdered milk Nationwide 29+ newbrunswick (29)

1967 Raw milk Washington 40+ typhimurum (53)

1971 Human milk Illinois I kottbus (74)

1971-1975 Certified raw milk California 44-1- dublin (70,124)

1975 ' 'Pasteurized milk Louisiana 43+ newport (15)

1977 Raw milk Kentucky 3 typhimurum (82)

1977 Human milk Maine 7 kottbus (99)

1977-1978 Certified milk California 57 dublin (30)

1978 ' 'Pasteurized milk' , Arizona 23+ typhimurum (46)

1979 Powdered milk Oregon 1+ agona, typhimurum (59)

1980 Cheddar cheese Colorado 339+ heidelberg (52)

1980-1981 Raw milk Washington 125 dublin (89)

1981 Certified raw milk California 1+ saint paul (20)

1981 Raw milk Montana 59 typhimurum (41 )

1981 Raw milk 14 dublin (5)

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION, VOL. 46, JULY 1983

MILK-BORNE DISEASE 641

TABLE 4. Milk-borne and milk-product-borne outbreaks of campylobacteriosis in the United States .

.

---~- ..- -..- -..- -..- - . - - .

Year Product State Number of References

Cases

1946 Raw milk Illinois 357 (75)

1965 Raw milk Oregon I (67)

1976 Certified raw milk California 4 (110)

1978 Raw milk Colorado 3 (14)

1979 Grade A raw chocolate milk New Mexico 41 (30)

1980-81 Raw milk Oregon 52 ( 111)

1981 Raw Milk Kansas 60+ (114)

1981 Certified raw milk Georgia 50 (26)

1982 Certified raw milk California

monella heidelberg infections, which affected at least 339 was either raw milk or certified raw milk. Three of the out-

persons, showed statistically significant association be- breaks affected farm families only. The other out-

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

tween ill persons and their having eaten foods containing breaks were associated with milk that had been bottled in

Cheddar cheese in Mexican-style restaurants (52). The dairies.

cheese was from a single lot produced by a single man- Between 1978 and 1980 in England and Wales, raw

ufacturer. The milk used in the manufacture of the cheese milk was implicated in 14 documented outbreaks of cam-

had been held unrefrigerated for 3 d in insulated tanks be- pylobacteriosis, which affected at least 3,553 persons

fore it was pasteurized. The effectiveness of the pasteuriza- (l00,109). In one of these outbreaks, 2,500 school chil-

tion process was not monitored. After pasteurization, the dren became ill during a 3-week period (69).

milk was filtered; a violation of the U.S. Public Health The largest number-648-of cases in a common-source

Service Milk Ordinance and Code, 1978 (118). Informa- outbreak ever recorded in Scotland was caused by Cam-

tion on culturing, curd formation, and ripening was not re- pylobacter transmitted by raw milk (122). In another Scot-

ported. tish outbreak, Campylabacter jejuni was isolated from

In England and Wales from 1969 to 1976, either milk or stools of 148 patients, from 57 asymptomatic persons, and

cream (usually raw) was implicated in 60 outbreaks of sal- from a milk filter, during an investigation of an outbreak

monelloses (117). Three percent of milk sold in England that followed ingestion of unpasteurized milk (91).

and Wales did not receive a heat treatment. In Canada, an outbreak of campylobacteriosis that af-

In Scotland, where 10% of the milk is sold without heat fected 27 persons occurred at a camp. Raw milk purchased

treatment, 29 milk-borne outbreaks of salmonelloses, af- from a local dairy was found to be contaminated by Cam-

fecting at least 2,428 persons, occurred between 1970 and pylobacter (83).

1979 (103). During this period, one outbreak that affected A wide variety of warm-blooded vertebrates have been

at least 700 persons was reported (104). Unpasteurized infected by C. jejuni. This organism has been isolated from

milk was identified as the vehicle. the intestinal tract and feces of man, cattle, goats, sheep,

Another outbreak of salmonellosis in which more than pigs, chickens and some wild birds. It has also been iso-

500 persons were affected was reported from South Au- lated from poultry meat, salt water and fresh water (46).

stralia (102). Bottled, unpasteurized milk was implicated. Rapid cooling of milk should prevent growth of C. jejuni,

In Trinidad, approximately 3,000 persons developed and either thorough cooking or pasteurization can be ex-

Salmonella derby gastroenteritis after they ingested one of pected to kill it.

seven different brands of powdered milk, which had been

packaged at a single processing plant on the island (123). Staphylococcal food poisoning

Cows usually become infected with salmonellae from Raw milk from individual cows or goats has been impli-

either the feedstuffs they eat or from contaminated sources cated as a vehicle in numerous outbreaks of staphylococcal

in their farm or barn environment. They also shed these or- intoxication before the practices of rapid chilling of milk

ganisms in their feces. Their udder or hide may become and pasteurization became common (JJ , 14,85). Pas-

contaminated with salmonellae when they wade in streams teurized milk that has become contaminated after being

or lie on fecally-soiled litter or ground. Milk can become heat treated has been a vehicle on rare occasions (21,63).

contaminated from such sources. Rapid chilling of raw Spray-dried milk has been the vehicle for staphylococcal

milk inhibits multiplication of salmonellae, however, and enterotoxin at least two outbreaks (6,7).

pasteurization by approved procedures kills large numbers Cheese has been a vehicle for staphylococcal enterotoxin

of Salmonella. in several outbreaks (2,18,65,66,77,82,129).

Staphylococci multiplied in the milk and elaborated en-

Campylobacteriosis terotoxin before fermentation commenced.

Milk-borne campylobacteriosis has been reported in the Ice cream has also been implicated as a vehicle of

United States, England and Wales, Scotland and Canada. staphylococcal enterotoxin in several outbreaks

The outbreaks that have been reported in the United States (44,60,88,125). Usually, ice cream mix was contaminated

are summarized in Table 4. The vehicle in all outbreaks at the time of preparation and the staphylococci multiplied

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION, VOL. 46, JULY 1983

642 BRYAN

TABLE 5. Cases of brucellosis associated with ingestion of domestic and foreign milk and milk-products (usually cheese) by year (23).

Year Total Cases related to unpasteurized milk or milk-products (cheese)

1971 171!190b 5 (2.9) 21 (12.3) 26 (\5.2)

1972 1791184 3 (1.7) 10 (5.6) 13 (7.3)

1973 166c 2 (1.2) 31 (18.7) 33 (19.9)

1974 235/246 7 (3.0) 14 (5.9) 21 (8.9)

1975 309 8 (2.6) 16 (5.2) 24 (7.8)

1976 271 6 (2.2) 18(6.6) 24 (8.8)

1977 232 4 (/.7) 11 (4.7) 15 (6.4)

1978 161 9 (5.6) 5 (3.1) 14 (8.7)

1979 212 10 (4.7) 28 (13.2) 38 (17.9)

Total 1936/1971 54 154 208 (10.7)

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

apercent of total case reports.

bCases reports/total cases reported.

cCase reports.

before and during the long period of cooling before the mix TABLE 6. Countries from which dairy products were processed

froze. Butter has also been implicated as a vehicle that were vehicles of Brucella, 1971-1979 (23).

(50,92,105,126). Country Number

Staphylococcus aureus is frequently found on cows ud- of cases

ders and in their teat canals. It is a common cause of mas- Mexico 115

titis. From these sources, staphylococci reach milk readily. United States 54

Milk and milk-products can also be contaminated by either Italy 12

hands or nasal discharges of dairy or processing plant Greece 5

workers. Staphylococci must multiply to produce sufficient Unspecified, Latin American countries 5

enterotoxin in foods to cause illness. Unspecified, European countries 3

India 2

Brucellosis Portugal 2

Milk-borne and milk-pro duct-borne brucellosis is a con-

Unspecified, Asian countries 2

Costa Rica

tinuing problem in the United States. Table 5 summarizes

France

reports that implicated milk and milk-products as the most Germany

probable sources of infection for approximately 10% of the Iran

known cases during the period 1971-1978 (23). Most of Kenya

the dairy product-associated cases have a history that in- Tanzania

cludes ingestion of milk products, usually raw goat-cheese, Thailand

produced in other countries. The countries in which these Unspecified, Middle-East country

products were produced are listed in Table 6. Examples of Total 208

outbreaks in which Mexican-prepared raw goat-cheese was

implicated are described (16,48,106.128). school children became ill after they ingested raw milk

Milk-producing animals-cattie, goats, sheep, and buf- which had been held at room temperature in a home for

faloes-can be reservoirs of brucellae. This organism has a about 4 h.

propensity for localizing in the uteri of females that are An outbreak of yersiniosis was discovered in New York

pregnant and in the mammary glands of lactating females. State during an investigation to uncover the reasons for an

Thereby, infected animals can for years shed brucellae in unusually high incidence of appendectomies in children

their milk. under 18 years old (12). The illness that caused the acute

Milk can also become contaminated with brucellae syndrome suggestive of appendicitis was caused by Y. en-

through contact with infected organs or fomities or from terocolitica. Chocolate milk was the epidemiologically im-

excreta or dust. Brucellae are quite resistant to environ- plicated vehicle. Chocolate syrup had been mixed and

mental stress. They survive in raw milk several hours, and added to milk after pasteurization.

in cheese several weeks, but usually not as long as a year. A report has been made of a Yersinia pseudotuberculosis

They can survive in frozen products a few years. [See septicemia and post-diarrheal, hemolytic, uremic syn-

Bryan (19) for a review of Brucella and brucellosis.] drome in a I5-month old child (93). This child and his

mother both became ill 1 d after they ingested goat's milk

Yersiniosis that had not been pasteurized.

Raw milk was suspected as a vehicle in an outbreak of Recently, Y. enterocolitica was responsible for an out-

Yersinia enterocolitica enteritis in Canada (42). Fifty-eight break affecting 148 persons from three states; most were

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION, VOL. 46, JULY 1983

MILK-BORNE DISEASE 643

hospitalized, 17 underwent appendectomies, one of these either milked cows or handled milk or milking equipment

persons died. It was estimated that 857 cases may have oc- and were considered as the source.

curred. Pasteurized milk was the implicated vehicle; details Dried milk has also been implicated as a vehicle (1,94).

about the source of contamination were discovered (73). Canned milk that had been opened and diluted the evening

An investigation revealed that unsold milk was returned to before serving was responsible for three outbreaks that in-

the dairy and fed to hogs. At the hog farm, milk crates cluded 835 cases of tonsillitis and scarlet fever (l09).

were stored on the ground down slope from hog pens.

Crates were returned to the dairy and washed, but the Diphtheria

washing failed to remove some of the mud in the triangular Before pasteurization became a common practice, many

configurations on the undersurface of the crates. Aulisio et diphtheria epidemics were epidemiologically associated

al. (10) hypothesized that the mud contaminated the bot- with raw milk. These outbreaks have been summarized by

tom of the milk containers when they were put into the various authors and reviewed by Bryan (19). In many of

crates; tops of the containers could have been contaminated the outbreaks, implicated milk came from farms on which

during stacking. Animals are frequently infected with Y. dairy workers were either carriers of Corynebacterium

diphtheriae or they suffered from clinical manifestations of

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

enterocolitica. Water in streams, often contain this or-

ganisms. Milk can become contaminated from these diphtheria. In other outbreaks, implicated milk came from

sources (68,120). cows that had superficial ulcers on their udders. Ice cream

has also been implicated as a vehicle (19). No milk-borne

outbreaks of diphtheria have been reported in the United

States since 1948.

MILK-BORNE DISEASES OF HISTORIAI, INTEREST

Tuberculosis

Typhoidfever Mycobacterium bovis can be transmitted by raw milk.

Before the practice of pasteurization and at a time before The ingested organisms penetrate the orophamx and intes-

farm sanitation was commonplace, there were frequent re- tine and give rise to lesions in the cervical lymph and

ports of outbreaks of milk-borne typhoid fever. Reviews of mesenteric nodes. From these sites, they are diseminated to

milk-borne typhoid fever outbreaks have been made bones and joints resulting in kyphosis, a condition in which

(8,19,107,115). the afflicted are commonly called hunchbacks. In recent

During investigations several sources of contamination years in the United States, the incidence of alimentary

were found: persons who had typhoid fever, who were car- tuberculosis has been low; however, in some other coun-

riers of Salmonella typhi or who nursed sick persons in tries, reports of this disease are much more common.

their family either milked cows or handled milk or milk Strong circumstantial evidence has incriminated raw

utensils or containers on milk-producing farms or in milk milk as a vehicle for transmitting M. bovis to man; out-

shops. Well water used to wash and rinse utensils and breaks have been reviewed (19). Factors that influence

equipment was another source of contamination. Bottles transmission of M. bovis are: (a) incidence of infection in

returned from homes of sick persons were suspected to be cows, (b) opportunities for contamination with M. bovis

the sources of contamination on a few occasions. More re- and the presence of and quantity of this organisms in milk,

cently, in Trinidad, ice cream was implicated as a vehicle (c) whether or not milk is boiled or pasteurized and (d) the

of S. typhi in an outbreak affecting 132 persons (106). milk-drinking habits of the populace.

Large quantities of tubercle bacteria can readily reach

milk of infected animals because both the mammary gland

Streptococcal infections and the lungs discharge into the same canalicular system.

Outbreaks of milk-borne scarlet fever and septic sore They can also reach milk from feces, which may dry upon

throat were frequent in the United States (and no doubt, and cling to the udder, tailor flanks of cows. Contamina-

elsewhere) before pasteurization of milk became nearly tion can come also from infected udders and from air-borne

universal. These outbreaks are reviewed (8,19,115). Sev- organisms that have orginated in respiratory discharges.

eral were traced to cows with either mastitis or lesions on Tuberculin testing and slaughter of reactors has almost

their teats or udders. The cows usually acquired group A eradicated tuberculosis from dairy cows in the United

streptococcal mastitis through contact with a human car- States. So contamination of milk from animal sources is

rier. Thereafter, they discharged large numbers of strep- quite rare today. Furthermore, the pasteurization process

tococci in their milk. If this milk was not pasteurized, out- was initially designed to kill large numbers of M. bovis

breaks resulted. (71).

Outbreaks of scarlet fever and septic sore throat were

also attributed to primary cases working at a farm or in Shigellosis

milk shops and either milking cows or otherwise handling A few outbreaks of shigellosis have been associated with

milk or milk equipment. For instance, milk was contami- milk and cheese. These have been reviewed (19,107). The

nated by a worker who, while suffering from an acute sore implicated milk or milk product was contaminated by a

throat, bottled the milk and capped the bottles. In some human carrier, and the milk was frequently held for several

outbreaks, persons who nursed sick persons in their family hours without refrigeration.

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION, VOL. 46, JULY 1983

644 BRYAN

Milk sickness was isolated from rectal swabs taken from 5 of 25 infants,

Grazing animals have developed trembles as a result of from the pump and from the vessel in which the pump had

eating leaves and stems of white snakeroot (Eupatorium been disinfected.

rugosum) or rayless goldenrod (Aplopappus heterophyllus

or lsocoma wrighii). Animals having this condition elimi- Listeriosis

nate tremetol ( a higher alcohol which is toxic to the liver) Foodborne transmission of listeriosis has not been con-

in their milk. Milk sickness is manifested by weakness, firmed in humans, but raw milk has been suspected to be

prostration, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, nausea, vom- a vehicle. For example, Potel (92) told about a woman

iting, muscular tremors and coma. It is frequently fatal. who had drunk milk from a cow with atypical mastitis and

Although, this disease is rare today, numerous cases and later gave birth to twins prematurely. The infants had mul-

deaths occurred among early settlers, particularly in the tiple tumors composed of granulation tissue, Listeria

midwest, before land was cleared. Significant to the occur- monocytogenes was isolated from the infants and from the

rence was that cattle foraged wooded areas and were cow's milk. In several cases of listeriosis that occurred in

milked only sporadically (81). Halle, Germany, raw milk was suspected as the vehicle,

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

and in other cases, suspicion was cast on cream, sour milk,

DISEASES RARELY REPORTED and cottage cheese (101).

AS BEING MILK·BORNE Listeriosis has been observed in cattle; udder infections

Botulism due to L. monocytogenes have been described, and this or-

Milk has been implicated as the vehicle in two outbreaks ganism has been found in milk. [See the review by Bryan

of botulism involving 5 cases. Outbreaks of botulism have (19) for further discussion and references.]

infrequently been traced to cheese (84). Seven cheese-as-

sociated outbreaks involving 21 cases, 9 of whom died, Clostridium perfringens enteritis

have been reported in the United States (25,81). Cottage In 1933, a report incriminated Clostridium perfringens

cheese was the vehicle in three outbreaks, cheese curd in as the cause of an outbreak of fever and flatulent diarrhea

one, Neufchatel in one, Liederkranz cheese spread in one, in infants (87). Although, the syndrome is not typical of C.

and an unspecified cheese in one. In 1974, an outbreak that perfringens enteritis, the hypothesis is interesting because

affected 11 persons who ate a commercially-prepared, C. perfringens can readily reach milk and its spores can

plastic-packaged, cheese spread containing dehydrated on- survive pasteurization. The heat of pasteurization would

ions was reported from Argentina (43). Yogurt has been heat-activate the spores and reduce populations of competi-

suspected of being a vehicle (5). tive organisms. Amino acids and growth factors necessary

to sustain growth of C. perfringens are constituents of

Escherichia coli enteritis milk, and this organism grows in milk causing a stormy

Camembert and Brie cheese from France were vehicles fermentation. Refrigerated storage of heat-treated milk

in an outbreak of diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli 0 would, however, prevent outgrowth of spores and multipli-

group 124, a non-lactose fermenter that reacted to Shigella cation of the vegetative cells.

antiserium (116). More than 100 episodes-387 cases-were

eventually traced to this source (78). A milk-borne out- Bacillus cereus gastroenteritis

break among children has been reported in the U.S.S.R. Milk and ice cream have been implicated as vehicles in

(80). outbreaks of gastroenteritis caused by Bacillus cereus. [See

Man and other animals shed large numbers of E. coli in Gilbert (61) for a more complete discussion of the role of

their feces. These organisms have been recovered from the B. cereus as a foodborne pathogen and for references.]

milk of apparently healthy animals, from those that had

mastitis and from samples of milk and cheese in retail Haverhill fever

stores. A few milk-borne outbreaks of Haverhill fever have been

reported (90). In one outbreak, Streptobacillus monilifor-

mis, the etiologic agent of rat-bite fever, was isolated from

Pseudomonas aeruginosa enteritis

most of the cases and serum antibodies were demonstrated

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which produces a heat-labile

in the other cases. All persons who were affected had

enterotoxin, has, on rare occasions, been implicated as an

drunk raw milk bottled from the same dairy. A cow in the

etiologic agent of milk-borne disease. In an outbreak invol-

herd from which the implicated milk came had a healed le-

ving 409 cases, infants were severely affected and 9 died

sion, suggestive of a rat-bite, on one teat. The outbreak

(49). Contaminated pasteurized milk was epidemiologi-

ended after the dairy began to pasteurize its milk.

cally implicated as the vehicle. During an investigation of

the plant that had processed the milk, P. aeruginosa was Qfever

recovered from a rag that had been used to wrap a pipe Coxiella burnetii is sometimes found in raw milk, and

joint. Drippings from the rag fell into the pasteurized milk. some investigators have implicated raw milk as a vehicle

In another outbreak, newborn infants vomited and had (19). Most of the evidence implicating milk as a vehicle,

diarrhea after being fed human milk that had been obtained however, is the greater frequency that compliment-fixing

by a breast-pump (113). The same strain of P. aeruginosa antibodies are found in the sera of persons who drank raw

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION. VOL. 46, JULY 1983

MILK-BORNE DISEASE 645

milk, than the frequency with which these antibodies are Histamine and tyramine in cheese are usually degraded

found in the sera of persons who did not drink raw milk. in the body by monoamine oxidase. Certain drugs, how-

Epidemiologic evidence presented by Brown et al (17) ever, inhibit this enzyme. Persons who have taken one of

suggested that ingestion of raw milk from infected cattle these drugs, have experienced attacks of hypertension

resulted in a common-source outbreak; contact with ani- shortly after ingestion of cheese; cerebrovacular accidents

mals, farms, dust and insects were ruled out as possible have been reported (/3).

routes of transmission. Ingestion of raw milk that con-

tained C. burnetii by human volunteers, however, has not Arsenic poisoning

caused illness (51,73). In the summer of 1955, 12,131 children in western

c. burnetii can survive vat-pasteurization at 61.7°C Japan were poisoned because they ingested arsenic-con-

(143°F) for 30 min; pasteurization at 62.8°C (l45°F) for 30 taminated dry milk. One-hundred-thirty of these children

min or at 71. 7°C (161°F) for 15 sec is adequate to kill this died. The arsenic reached the milk from an inadequately

organism. purified "sodium phosphate" stabilizer which was used in

the manufacturing process. Fourteen years later, survivors

Hepatitis A

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

had a higher rate of physical and mental complaints than a

Just about any food that is handled by a person who is control group (127).

shedding hepatitis A virus can become a vehicle for this or-

ganism. Raw milk from a small dairy was implicated in an ROLE OF MILK

outbreak in Geiorgia (86). Cream used in a fruit salad and AND MILK PRODUCTS AS VEmCLES

in sherry trifles (prepared by a pastry-cook who was in the

incubation phase of hepatitis A) was the vehicle of another Raw milk

outbreak (27). Microorganisms that reach a cow's teats can enter them

through their openings and migrate to the interior. The

Poliomyelitis types and numbers of microorganisms that invade the

Raw milk-associated outbreaks of poliomyelitis have udder by this route vary from animal to animal and even

been reported. [See Cliver (27) for a review.] In one of among the quarters of the same udder. Such invasion can

these outbreaks, all cases had drunk milk from a small occur even in healthy animals. Micrococci, staphylococci,

dairy. At this dairy, a 16-year old milker handled milk for streptococci and diphteroides usually predominate among

4 d while in the acute phase of poliomyelitis (72). the microbial flora of the teat and udder.

Mastitis, an inflammitory disease of mammary tissue,

Russian spring-summer encephalitis (Disphastic milk can lead to development of millions of pathogens in the in-

fever) fected quarter and the discharge of large numbers of them

Ingestion of raw milk and of cheese made from raw milk to milk. Milk-borne pathogens that can cause mastitis, in-

from tick-infested sheep and goats has resulted in en- clude, S. aureus, streptococci, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, C.

cephalitis. Reports of this disease have been limited to the perfringens. streptococci, corynebacteria and mycobac-

U.S.S.R. (96). teria. Animals infected with other pathogens, such as

Toxoplasmosis Brucella spp., C. burnetii and M. bovis, can shed them,

The ingestion of raw milk from goats and cattle raises too, in milk.

the possibility of transmission of Toxoplasma gondii; ani- Microorganisms from soil, litter, feed, water, feces and

mal-to-animal transmission by milk has been demonstrated other items in a farm environment commonly contaminate

(57). A 7-month old child who had a history of being fed the surface of the udder and teats and the hair and skins of

almost exclusively on raw goat's milk developed toxoplas- cows and goats. From these sources they can get into milk

mosis (98). Goat's milk is sometimes prescribed for infants during milking. Sporeformers such as B. cereus and C.

who cannot tolerate cow's milk. perfringens can reach milk from soil and litter. Salmonel-

lae as weB as sporeformers can be transmitted to milk from

Histamine intoxication and hypertension feed. Yersinia and Campylobacter may reach milk from

Histamine is a powerful capillary dilator; it causes in- contaminated water in streams and ponds. Salmonella,

tense headaches, nausea, vomiting, facial flushing, burn- Campy/obacter, Yersinia, enterococci, E. coli and C. per-

ing throat, thirst, swelling of lips, and urticaria. Histamine fringens can reach milk if feces of infected animals reach

intoxication after ingestion of cheese has been reported milk either directly or from contaminated exteriors of

(45,1 19). Histamine was suspected to be the cause of an cows.

outbreak affecting 38 cases in persons who ate either Equipment used for milking, filtering, cooling, storing

cheese crepes or onion soup on which cheese had been or distributing milk are also important sources of microor-

placed (24). Histamine can be formed in cheese when his- ganisms. This situation is aggravated if the equipment is

tidine, which is often found in cheese, is decarboxylated. not properly cleaned and sanitized after use. Milk residues

Many Enterobacteriaceae, enterococci, and Lactobacillus left on equipment and utensil surfaces provide nutrients to

casei produce decarbocylase. [This topic has been re- support growth of many microorganisms, including patho-

viewed (19,97,121).] gens.

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION, VOL. 46. JULY 1983

646 BRYAN

Farm workers who either milk animals or handle milk, those organisms that reach raw milk may be found in the

or milking or storage equipment, can contribute additional cheese. Brucellae that reach cheese and survive the cheese

organisms to the milk. Such contamination has resulted in making process have caused several cases of brucellosis.

numerous milk-borne outbreaks of typhoid fever, Salmonellae, also frequently reach milk, and they can

diphtheria, septic sore throat, scarlet fever, shigellosis, grow during cheese making and persist during ripening of

staphylococcal enterotoxicosis, hepatitis A and certain cheeses for 60 days or more.

poliomyelitis. Slow acid production (low milling acidity) by a starter

culture can allow staphylococci to grow and perhaps pro-

Certified milk duce enough entertoxin to cause disease if process temper-

Certified milk is raw milk which is produced under strict tures are favorable during curd formation. If the pH of the

conditions that comply with standards of sanitation adopted curd is higher than normal (5.2-5.3), growth of

by the American Association of Medical Milk Commis- staphylococci can even continue during pressing, but sel-

sions (3). These procedures were originated in the early dom afterwards. Their numbers decline rapidly during ri-

1800's to produce safe milk before pasteurization became pening.

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

common. In spite of these precautions, including produc- E. coli hazards are of particular concern in soft and

tion of milk with low bacterial counts, certified milk has semisoft surface-ripened cheeses. E. coli can multiply in

been implicated as the vehicle in several milk-borne out- soft and semisoft surface-ripened cheses when there is lack

breaks throughout the years; including, the last few years. of acid production and low salt concentration in the interior

during the early stage of ripening (56). Furthermore, this

Pasteurized milk organism can grow on surfaces of these cheeses during the

Pasteurization or more severe heat treatments applied to development of the mold matt, if temperatures are suffi-

raw milk is the only way to ensure that pathogens likely to ciently high (55).

be present are killed and that the milk is safe. When pas- C. botulium sometimes reaches milk because of soil or

teurized milk has been implicated as a vehicle, further in- dust contamination. It's spores survive pasteurization. C.

vestigation has shown that there was either a process fail- botulium can multiply 'in lightly salted cheeses that have

ure or post-pasteurization contamination. Pasteurization, relatively high pH values (resulting from faulty starter cul-

more than improved dairy sanitation practices, has resulted ture activity) and a closed structure, which is conducive to

in the dramatic decrease in milk-borne diseases during the anaerobiosis.

past 35 years. Adequate heat treatment of milk and normal starter ac-

Ice cream tivity are the best preventives of cheese-borne disease out-

breaks. Prolonged ripening also results in a decrease in,

When raw milk was frequently used to make ice cream,

but not necessarily freedom from, pathogens.

outbreaks were common. Eggs, not milk, have been the

source of salmonellae in recent outbreaks of salmonellosis

that have been transmitted by ice cream (63). Whatever REFERENCES

their source, pathogens that are incorporated into ice cream

can survive in the frozen product many months. 1. Allen, R. F., and Baer, L. S. 1944. Outbreak of septic sore throat

Use of pasteurized milk in ice mixes, either omission of due to reconstituted powdered milk. J. Amer. Med. Assoc.

124:1191-1193.

eggs or use of pasteurized egg products in these mixes, and

2. Allen, V. D., and W. D. Stovall. 1960. Laboratory aspects of

rapid freezing of these mixes, minimize the possibility of staphylococcal food poisoning from Colby cheese. J. Milk Food

ice cream becoming a vehicle of sufficient numbers of Technol. 23:271-274.

pathogens to cause illness. 3. American Association of Medical Milk Commissions. 1976.

Methods and standards for the production of certified milk. Amer.

Assoc. Med. Milk Commissions, Alpharetta, Georgia.

Dry milk

4. Anderson, H, W. and D. R. Peterson. 1965. Salmonella

Dry milk has been the vehicle of outbreaks because (a) typhimurium infection traced to raw milk, Salmonella Surveillance

it was not pasteurized before drying, (b) it was held at tem- Rep. No. 49, Center for Disease Control, Atlanta.

peratures that permitted the growth of S. aureus and the 5. Anderson, H .. J. Ballard, J. Lewis, J. Allard, B. J. Edmundson,

production of entertoxin before drying, or (c) product ac- and Centers for Disease Control. 1981. Salmonella dublin as-

sociated with raw milk-Washington State. (u.S,) Morbidity Mor-

cumulation and persistence of moisture in an instantizer,

tality Week. Rept. 30:373-374.

led to multiplication of salmonellae. Pasteurizing, hot 6. Anderson. P. H. R., and D. M. Stone. 1955. Staphylococcal food

holding at not less than 65°C (149°F) in balance and surge poisoning associated with spray-dried milk. J. Hyg. 53:387-397.

tanks, and cleaning equipment surfaces that contact the dry 7. Armijo, R., D. A. Henderson, R. Timothee, and H. B. Robinson.

product to prevent product from accumulating in crevices 1957. Food poisoning outbreaks associated with spray-dried milk

an epidemiologic study. Amer. J. Public Health, 47:1093-1100.

and dead ends, and to keep moisture from reaching the

8, Armstrong, C, and T. Parran, Jr. 1927, Further studies on the im-

dried product, are essential to prevention of outbreaks as- portance of milk and milk products as a factor in the causation of

sociated with dried milk. outbreaks of disease in the United States. Public Health Rep.

Supp\. No. 62:1-8:

Cheese 9. Arnold, S. H., and W. D. Brown. 1978. Histamine (?) toxicity

Unless, the milk used to make cheese is pasteurized, from fish products. Adv. Food Res. 24:113-154,

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION. VOL. 46, JULY 1983

MILK-BORNE DISEASE 647

10. Aulisio, C. C., Lanier, J. M., and Chappel, M. A. 1982. Yersinia outbreaks. Public Health Rep. 74:715-720.

enterocolitica 0: 13 associated with outbreaks in three southern 36. Dauer, C. C., and D. J. Davids. 1960. 1959 summary of disease

states. J. Food Prot. 45:1263. outbreaks. Public Health Rep. 75: 1025-1030.

II. Barber, M. A. 1914. Milk poisoning due to a type of Staphylococ- 37. Dauer, C. C., and G. Silvester. 1954. 1953 summary of disease

cus albus occurring in the udder of a healthy cow. Philippine J. Sci. outbreaks. Public Health Rep. 69:538-546.

9B:515-519. 38. Dauer, C. C., and G. Silvester. 1955. 1954 summary of disease

12. Black, R. E., R. 1. Jackson, T. Tsai, M. Medvesky, M. outbreaks. Public Health Rep. 70:536-544.

Shayegani, J. C. Feeley, K. I. E. Macleod, and A. M. Wakelee. 39. Dauer, C. C., and G, Silvester. 1956. 1955 summary of disease

1978. Epidemic Yersinia enterocolitica infection due to contami- outbreaks. Public Health Rep. 71:797-803.

nated chocolate milk. N. Engl. J. Med. 298:76-79. 40. Dauer, C. C., and G. Silvester. 1957. 1956 summary of disease

13. Blackwell, B., E. Marley, J. Price, and D. Taylor. 1967. Hyper- outbreaks. Public Health Rep. 72:735-742.

tensive interactions between monoamine oxidase inhibitors and 41. Day, C., W. R. DeCov, D. Feffer, J. Glosser, B. Desonia, D, Ab-

food stuffs. Brit. J. Psychiat. 113:349-365. bott, M. Skinner, J. S. Anderson, and CDC. 1981. Salmonellosis

14. Blaser, M. 1., J. Cravens, B. W. Powers, F. M. Laforce, and W-L. associated with raw milk Montana. (U.S.) Morbidity Mortality

L. Wang. 1979. Campylobacter enteritis associated with unpas- Week. Rep. 30:211-212.

teurized milk. Amer. J. Med. 67:715-718. 42, de Grace, M., M. F. Laurin, C. Belanger, P. E. Rolland, R. Blais,

15. Blouse, Jr., L. E., R. E. Genglei, G. D., Lathrop, R. A. Hodder, J. P. Breton, and G. Martineau. 1976. Yersinia enterocolitica gas-

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

T. Nowosiwski, C. T. Caraway, FDA, and CDC. 1975. A com- trocnteritis outbreak-Montreal. Can. Dis. Week. Rep. 2(11):41.

mon-source outbreak of Salmonella newport-Louisiana. (U.S.) 43. de Lagarde, E. A., C. V. del Prodo, C. G. Malbran, and P. Gar-

Morbidity Mortality Week. Rep. 24:413-414. bugino. 1976. Botulism associated with cheese spread-Buenos

16. Brian, L., J. Kurowski, M. Eckman, T. M. Vernon, B. F. Aires, Argentina. Morbidity Mortality Week. Rep. 25:187,

Rosenblum, M. Apodaca, M. S. Dickerson, and CDC. 1973. Inter- 44. de Witt, R. F. 1935. A recent outbreak of food poisoning in

state outbreak of non-abattoir associated brucellosis. (U.S.) Mor- Shoreham, Vermont. N. Eng\. J. Med. 213:1283-1284.

bidity Mortality Week. Rep. 22:193-194. 45. Doeglas, H. M. G., J. Huisman, J. P. Nater. 1967. Histamine into-

17. Brown, G. L., D. C. Colwell, and H. L. Hooper. 1968. An out- xication after checse. Lanet 2:1361-1362.

break of Q fevcr in Slraffordshire. J. Hyg. 66:649-655. 46. Dominguez, L. B., A. Reiter, F. J. Marks, W. B. Press, K. M.

18. Bryan, F. L. 1976. Staphylococcus aureus. In M. P. Defigueiredo Starko, and CDC. 1979. Salmonella gastroenteritis associated with

and D. F. Splittstoesser (eds.), Food microbiology: Public health milk-Arizona. (U.S.) Morbidity Mortality Week. Rep. 28:117,119-

and spoilage aspects. AVI, Westport, Connecticut. 120.

19. Bryan, F. L. 1979. Infections and intoxications covered by other 47. Doyle, M. 1981. Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni. An old patho-

bacteria. In H. Riemann and F. L. Bryan (eds.), Foodborne infec- gen of new concern. J. Food Prot. 44:480-488.

tions and intoxications, 2nd ed. Academic Press, Ncw York. 48. Eckman, M. R. 1975. Brucellosis linked to Mexican cheese. J.

20. California Dcpartment of Health Services and FDA. 1981. Raw- Amer. Med. Assoc. 232:636-637.

milk associated illness-Oregon, California. (U.S.) Morbidity Mor- 49. Ensign, P. R. and C. A. Hunter. 1946. An epidemic of diarrhea in

tality Week. Rep. 30:91-92,97. the newborn nursery caused by a milk-borne epidemic in the com-

21. Caudill, F. W., and M. A. Meyer. 1943. An epidemic of food munity. J. Pediatr. 29:620-628.

poisoning due to pasteurized milk. J. Milk Techno!' 6:73-76. SO. Fanning, J. 1935. An unusual outbreak of gastroenteritis. Brit.

22. Center(s) for Disease Control. 1971-1981. Foodborne (and water- Med. J. 1:583-584.

borne) disease outbreaks. Annual Summary, 1970-1979. Centers 51. Fonseca, F., M. R. Pinto, J. Olivera, M. M. Dagama, and M. T.

for Disease Control, Atlanta. Lacerda. 1949. Q fever in Portugal. Disease caused by inoculation

23. Center for Disease Control. 1972-1979. Brucella surveillance an- into human beings. Clin. Contemp. 3:1567-1578.

nual summary. Center for Disease Control, Atlanta. 52. Fontaine, R. E., M. L. Cohen, W. T. Martin, and T, M. Vernon.

24. Center for Disease Control. 1977. Foodborne and waterborne dis- 1980. Epidemic salmonellosis from Cheddar cheese: Surveillance

ease outbreaks. Annual summary. 1976. Center for Disease Con- Prevention. Amer. J. Epidemiol. 111:247-253.

trol, Atlanta. 53. Francis, B. J., J. Allard, and CDC. 1967. Salmonella

25. Center for Disease Control. 1979. Botulism in the United States, typhimurium-Yakima County, Washington. Morbidity Mortality

1899-1977. Handbook for epidemiologists, clinicans, and laborato- Week. Rep. 16:178.

ry workers. Center for Disease Control, Atlanta. 54. Frank, L. C. 1940. Disease outbreaks resulting from faculty envi-

26. Center for Disease Control. 198 I. Epidemiologic investigation data ronment. Public Health Rep. 55: 1373-1382.

on certified raw milk. Center for Disease Control, Atlanta. 55. Frank, J. F., E. H. Marth, and N. F. Olson. 1977. Survival of en-

27. Chaudhuri, A. K. R., G. Cassie, and M. Silver. 1975. Outbreak of teropathogenic and nonpathogenic Escherichia coli during the man-

foodborne type-A hepatitis in greater Glasgow. Lancet. 2:223-225. ufacture of Camembert cheese. J. Food Prot. 40:835-842.

28. Cliver, D. O. 1969. Viral infections. In H. Riemann (ed.), Food- 56. Frank, J. F., E. H. Marth, and N. F. Olson. 1978. Behavior of en-

borne infections and intoxications. Academic Press. New York, teropathogenic Escherichia coli during manufacture of brick

29. Collins, R. N., M. D. Treger, J. B. Goldsby, J. R. Boring III, D. cheese. J. Food Prot. 41:111-115.

B. Coohon, and R. N. Barr. 1968. Interstate outbreak of Sal- 57. Frenkel, J. K. 1973. Toxoplasmosis: Parasite life cycle, pathology

monella newbrunswick infection traced to powdered milk. 1. and immunoloty. In D. M. Hammond and P. L. Long (eds.), The

Amer. Med. Assoc. 203:838-844. coccoidia, Vniversity Park Press, Baltimore.

30. Currier, R. W. 1981. Raw milk and human gastrointestinal disease: 58. Fuchs, A. W. 1941. Disease outbreaks from water, milk, and other

Problems resulting from legalized sale of "certified raw milk". J. foods. Public Health Rep. 56:2277-2284,2468.

Public Health Policy. 2:226-234. 59. Furlong, J. D., W. Lee, L. R. Foster, L. P. Williams, FDA, and

31. Dauer, C. C. 1952. Food and waterborne disease outbreaks. 1951 CDC. 1979. Salmonellosis associated with consumption of nonfat

summary. Public Health Rep. 67:1089-1095. powdered milk-OregQn. (U.S,) Morbidity Mortality Week. Rep.

32. Dauer, C. C. 1953. 1952 summary of foodborne, waterborne, and 28:129-130.

other disease outbreaks. Public Health Rep. 68:696-702. 60. Geiger, J. C., A. B. Crowley, and J. P. Gray. 1935. Food poison-

33. Dauer, C. C. 1958. 1957 summary of disease outbreaks. Public ing from ice cream on ships. J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 105:1980-

Health Rep. 73:681-686. 1981.

34. Dauer, C. C. 1961. 1960 summary of disease outbreaks and a 10- 61. Gilbert, R. 1979. Bacillus cereus, in H. Riemann and F. L. Bryan

year resume. Public Health Rep. 76:915-922. (eds.), Foodborne infections and intoxications. Academic Press,

35. Dauer, C. c., and D. J. Davids. 1959. 1958 summary of disease New York.

JOURNAL OF FOOD PROTECTION, VOL. 46, JULY 1983

648 BRYAN

62. Gunn, R. A. and G. Markakis. 1978. Salmonellosis associated with Hooper Foundation, UniVersity of California, San Francisco Medi-

homemade ice cream. An outbreak report and summary of out- cal Center.

breaks in the United States in 1966 to 1976. J. Amer. med. Assoc. 85. Minor, T. E. and E. H. Marth. 1976. Staphylococci and their sig-

240: 1885-1886. niticance in foods. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co., Tokyo.

63. Hacker. 1. F. 1939. Outbreak of Staphylococcus milk poisoning in 86. Murphy, W, J., L. M. Petrie, and S. D. Work. 1946. Outbreak of

pasteurized milk. Amer. J. Public Health. 29:1247-1249. infectious hepatitis apparently milk-borne. Amer. J. Public Health.

64. Health Protection Branch. 1976-1981. Foodborne and waterborne 36: 169-173.

disease in Canada. Annual summary 1973-1977. Health and Wel- 87. Nelson, C. I. 1933. Flatulent diarrhea due to Clostridium welchii.

fare Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. 1. Infect. Dis. 58:89-93.

65. Hendricks. S. L., R. A. Belknap, and W. J. Hausler, Jr. 1959. 88. New York State Department of Health. 1940. Gastroenteritis traced

Staphylococcal food intoxication due to Cheddar cheese. 1. to homemade ice cream. Health News 17:104.

Epidemiology. J. Milk Food TechnoL 22:313-317. 89. Nolan, C. M., H. W. Anderson, and D. E. T. Hoyt. 1981. Sal-

66. Hobbs. B. C. 1964. Food poisoning: Observations on sources of monella surveillance pays off. Epi-Iog July/August 1981. Seattle-

salmonellae, Clostridium peifringens and staphylococci. Ann. Inst. King County Department of Public Health, Seattle.

Pasteure Lille. 15:31-41. 90. Place, E. H., and L. E. Sutton, JI. 1934. Erythema Arthritcum

67. Holmes, M. A., W. Austin, W. Austin, and CDC. 1965. Vibrio epidemicum (Haverhill fever). Arch. Intern. Med. 54:659-684.

fetus infections in humans-Oregon. (U.S.) Morbidity Mortality 91. Porter, I. A., and T. M. S. Reid. 1980. A milk -borne outbreak of

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/46/7/637/1656112/0362-028x-46_7_637.pdf by Nigeria user on 29 July 2021

Week. Rep. 14:425-426. Campylobacterinfection. J. Hyg. 84:415-419.

68. Hughes, D., and N. Jensen. 1981. Yersinia enterocolitica in raw 92. Potel, J. 1953. Zur Epidemiologie der Listeriose der Neugeborenen

goats milk. AppL Environ. MicrobioL 41:309-310. (Granulomatosis infantiseptica). Wiss Z. t:niv. Halle. 3:341-364.

69. Jones, P. H., A. T. Willis, D. A. Robinson, M. B. Skirrow, and 93. Prober, C. G., B. Tune, and L. Hoder. 1979. Yersinia

D. S. Josephs. 1981. Campylobacter enteritis associated with the pseudotuberculosis septicemia. Amer. J, Dis. child. 133:623-624.

consumption offree school milk. J. Hug. 87:155-170. 94. Purvis, J. D., and G. C. Morris. 1946. Report offoodborne Strep-

70. Kamei, I., L. Mahoney, R. R. Sachs, E. Aaron, S. B. Werner, and tococcus outbreak. U.S. Nav. Bull. 46:613-615.

G. L. Humphrey. 1974. Human Salmonella dublin infections as- 95. Reinius, L. and H. Lemme. 1981. WHO Surveillance for control of

sociated with consumption of certifed raw milk-California. (U.S.) foodborne infections and intoxications in Europe. First Report.

Morbidity Mortality Week. Rep. 23:175. FAO/WHO colloborating. Centre for Research and Training in

71. Kells, H. R. and S. A. Lear. 1960. Thermal death time curve of Food Hygiene and Zoonoses, Berlin, West.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. bovis in artificially infected milk. 96. Rhodes, A. J., and C. E. van Rooyen. 1968. Textbook of virology,

App!. Microbiol. 8:234-236. 5th ed. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore.

72. Knapp, A. C., E. J. Godfrey, Jr., and W. L. Aycock, 1926. An 97. Rice, S. L., R. R. Eitcnmiller, and P. E. Koehler. 1976. Biologi-

outbreak of poiomyelitis, apparently milkborne. 1. Amer. Med. cally active amines in food. A review. J. Milk Food Techno!.

Assoc. 87:635-639. 39:353-358.

73. Krumbiegel, E. R., and H. J. Wisniewski. 1970. Q fever in the 98. Riemann, H, P., M. E. Meyer, J. H. Theis, G. Kelso, and D. E.

Milwaukee area II. consumption of infected milk by human volun- Behymer. 1975. Toxoplasmosis in an infant fed unpasteurized goat

teers. Arch. Environ. Health. 21 :63-65. milk. 1. Pedial. 87:573-576.

74. Lang, C. A., G. Simonek, P. R. Schurrenberger, F. D. Yoder, and 99. Ryder, R. W., A. Crosby-Ritchie, B. McDonough, and W. J. Hull

CDC. 1971. Salmonella kottbus meningitis associated with con- III. 1977. Human milk contaminated with Salmonella kottbus. A

taminated breast milk-Illinois. (U.S.) Morbidity Mortality Week. cause of nosocomical illness in infants. J, Amer. Med. Assoc.

Rep. 20;154. 238:1533-1534.

75. Levy, A. J. 1946. A gastro,enteritis probably due to a bovine strain 100. Robinson, D. A., and D. M. Jones. 1981. Milk-borne Campylobac-

of Vibrio. Yale J. BioI. Med. 18:243-258. ter infection. Brit. Med. J. 282:1374-1376.

76. Lofgren, J. P., C. Konigsberg, R. Rendtoff, V. Zee, R. H. Hutche- 101. Seeliger, H. P. R. 1961. Listeriosis. Hafner, New York.

son Jr., A. Rausa, D. Brower, W. E. Riecken, Jr., and CDC. 102. Seglenieks, Z., and S. Dixon. 1977. Outbreak of milkborne Sal-

1982. Multi-state outbreak of yersiniosis. (U.S.) Morbidity Mortal- monella gastroenteritis-South Australia. (U.S.) Morbidity Mortality

ity Week. Rep. 31:505-506. Week. Rep. 26:127.

77. Mac Donald, A. 1944. Staphylococcal food poisoning caused by 103. Sharp, 1. C. M., G. M. Paterson, and G. I. Forbes. 1980. Milk-

cheese. Mon. Bull. Min. Health, Public Health Lab. Servo (Gr. borne salmonellosis in Scotland. J. Infect. 2:333-340.

Brit.). 3: 121- 122. 104. Small, R. G" and J. C. M. Sharp. 1979. A milk-borne outbreak

78. Maier, R., J. G. Wells, R. C. Swenson, and I. J. Mehlman. 1973. due to Salmonella dublin. 1. Hyg. 82:95-100.

An outbreak of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli food borne dis- 105. Stone, R. V. Sr. 1943. Staphylococci food-poisoning with dairy

ease traced to imported French cheese. Lancet 2:1376-1378. products. 1. Milk Techno!' 6:7-16.

79. Marth, E. H. 1969. Salmonellae and salmonellosis associated with 106. Street, L .. W. W. Wilson. and J. D. Alva. 1975. Brucellosis child-

milk and milk products. A review. J. Dairy Sci. 52:283-315. hood. Pediatr. 55:416-421.

80. Matsievskii, V. A., A. V. Logacher, A. P. Fedorina, and A. S. 107. Tanner, F. W., and L. P. Tanner. 1953, Food-borne infection and

Pislova. 1971. Outbreak of food poisoning caused by Escherichia intoxication, 2nd ed. Garrard Press, Champaign, Illinois.

coli. 124:K72(B 17). Zhurnal. Mikrobiogii, Epidemiologii i Im- 108. Taylor, A. Jr., A. Santiago, A. Gonzalez-Cortes, and E., Gan-