Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Belgium (Flemish)

Belgium (Flemish)

Uploaded by

Useful StuffOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Belgium (Flemish)

Belgium (Flemish)

Uploaded by

Useful StuffCopyright:

Available Formats

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY

Dirk Janssens

Patrick Durieux

Department of Education, Ministry of the Flemish Community

Jan Van Damme

Kim Bellens

University of Leuven, KU Leuven

Language and Literacy

Belgium is a federated country with three official languages: Dutch, French, and German. The Flemish

region of Flanders, a Dutch speaking community with nearly 6.5 million inhabitants, is in the northern

part of the country. French and Dutch are the official languages of the region of Brussels, and Wallonia

is a French speaking community situated in the southern part of Belgium next to a small German

speaking community in the eastern part of the country.

Dutch is the official language and the language of instruction in the Flemish Community, which

includes the Dutch speaking schools in the region of Brussels. The Flemish population, however, is

becoming more ethnically and culturally diverse, with the percentage of students speaking a home

language other than Dutch increasing annually; during the 2015–2016 school year, this included up to

17 percent of the population in primary education.1 The larger cities in Flanders tend to have

significant immigrant populations speaking different mother tongues at home. In the classroom, these

children are educated in Dutch.

Overview of the Education System

The Minister of Education heads the Flemish Ministry’s Department of Education and Training, and

the Flemish government supervises education policy from the preprimary level through university and

adult education. The Belgian Constitution guarantees all children the right to education.2 Mainstream

preprimary education, which is not compulsory, is available for children ages 2½ to 6. Almost all

children in Flanders receive preprimary education. Compulsory education starts on September 1 of

the year in which children reach age 6 and continues for 12 years. Students must attend school full time

until age 15 or 16. After that, at least part time schooling (a full time combination of part time study

and work) is required, although most young people continue to attend full time secondary education.

Free compulsory education ends in June of the year in which the student reaches age 18. Preprimary,

primary, and secondary schools that are funded or subsidized by the government cannot demand any

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 1

fees. Compulsory education does not necessarily require attendance at a school; home education is an

alternative.

The Flemish government develops the attainment targets and the minimum objectives of the core

curriculum (e.g., for the end of primary school). Governing bodies (i.e., school boards) are the main

key to the organization of education in Flanders and can be responsible for one or several schools.

These bodies are free to choose teaching methods based on their own philosophy or educational vision.

They also can determine their own curriculum and timetables and appoint their own staff. Most

schools in Flanders are part of an educational association of schools—an organization that supports

schools in terms of logistics, administration, and pedagogy (e.g., the association of Catholic schools or

the associations of public schools commissioned by the Flemish Community or organized by a town

or a province). These associations of schools develop their own curricula for each grade or each phase

of two grades. In that sense, there are several national curricula in Flanders.

In Flanders, preprimary and primary education are offered in two forms: mainstream and special.

Special preprimary and primary education are meant for children who need special help, temporarily

or permanently. Many students with special needs are able to remain in regular education with some

special attention and aid from a teacher or a remedial teacher. However, regular education is not always

equipped to meet the needs of students who require special assistance temporarily or permanently.

Special education schools provide these children (6.3 percent of the population of students in primary

education) with adapted education, training, care, and treatment.

These students are divided into eight education types based on the nature and degree of the main

disability within a certain group. Approximately 60 percent of them belong to the type “Education-

basis offer”: children whose special educational needs are significant and for whom it is proven that

the adaptations are disproportional or insufficient to include the student in the common curriculum

in a mainstream primary school. This type combines the former type 1 (minor mental disability) and

type 8 (severe learning disability), which was slowly phased out. The other types are organized for

students with a mental disability (type 2); an emotional or behavioral disorder (type 3); a motor

disability (type 4); a temporary admission to a hospital, residential setting, or preventorium (type 5); a

visual impairment (type 6); aural impairment or a speech or language defect (type 7); or an autism

spectrum disorder without a mental disability (type 9).

There is no common curriculum in special schools. Students in special schools have an

individualized curriculum that is adapted to the needs and possibilities of each student. The objectives

are autonomously selected by the school, based on the attainment targets of mainstream primary

education and/or the developmental objectives of the educational types 1, 2, 7, or 8. With the exception

of education types 2 and 5 and subject to certain conditions, all students of all education types can

receive support in mainstream education within a framework of integrated education. With support,

a limited number of students who have a moderate or severe intellectual disability (with a registration

report for education type 2) can be catered to in mainstream primary education within the framework

of inclusive education.

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 2

Language/Reading Curriculum in the Fourth Grade

Reading Policy

Freedom of education is a constitutional right in Belgium. The Flemish government doesn’t regulate

educational processes and methods. The responsibility for the quality of education lies mainly with the

school and the teachers. The Flemish coalition agreement is very clear about this: the government

imposes the “what” but not the “how.”3 Schools thereby have an increasing amount of responsibility

for their own projects. This allows schools to develop their own educational policies—including their

own pedagogical plan, teaching methods, curriculum, and timetables—and to appoint their own staff.

Although schools receiving public funding are required to operate within a regulatory framework, they

have considerable autonomy.4

Quality control by the Ministry is limited to quality control by the Flemish Inspectorate, which acts

as an independent professional system of external supervision. The government, through the eyes of

the inspectorate, evaluates whether the efforts of schools toward these attainment targets—including

those for Dutch—are sufficient. In addition, the Inspectorate examines whether the curriculum-based

objectives are being reached and whether the developmental objectives and cross-curricular

attainment targets have been sufficiently pursued.

The concept note Measures for primary education and the first stage of secondary education, which

was approved by the Flemish government at the end of May 2016, aims to strengthen language

education in primary education.5 The note foresees the option of language initiation in French, English,

or German from the first year of primary education. From the third year onward, this can develop into

fully fledged foreign language education.

Concerning reading policy, the Flemish government is limited to decisions on the minimum

objectives, which is called the core curriculum (i.e., the “what”). Nevertheless, the Minister of

Education aims to strengthen primary education with special attention to language, develop a broad

framework for an active language policy in schools, and stimulate organizations to take initiatives to

promote reading.6,7 Consequently, many organizations take initiatives to enhance literacy and reading,

frequently in association with or sustained by the Ministry or one of its departments.

Summary of National Curriculum

Preprimary and primary schools have to implement at least the core curriculum of the Flemish

Ministry of Education and Training and have to pursue or achieve the “final objectives.”8 These

objectives are “minimum objectives the educational authorities consider necessary and feasible for a

particular part of the pupil population … [that] apply to a minimum set of knowledge, skills and

attitudes for this part of the pupil population.”

The common core curriculum in preprimary and primary schools consists of physical education,

art education, world studies (split into “Man and Society” and “Science and Technology”),

mathematics, and Dutch (listening, speaking, reading, writing, strategies, linguistics, and

[inter]cultural focus). Cross-curricular themes, particularly for primary education, include learning to

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 3

learn, social skills, and Information and Communications Technology (ICT). French is a compulsory

subject for students in Grades 5 and 6 of primary school. French may be offered from the third year

and in the Brussels-Capital Region from the first year of primary education.

The general objectives of preprimary and primary education are translated into developmental

objectives and attainment targets that indicate more concretely what is considered desirable and

achievable for children in elementary education. The general aims are a broad curriculum, active

learning, care for every student, and coherence.

For Dutch, the core curriculum contains more general objectives for students:

• Transmit information orally and in written form and incorporate various oral and written

messages from others into relevant situations in and out of school

• Think critically about language and about their own and others’ use of the language

• Know which factors are important in communication and take them into account

• Have a positive willingness to:

o Use language in different situations to develop themselves and to give and receive information

o Think about their own reading behavior

• Have an unbiased attitude toward linguistic diversity and language variation

• Find pleasure in dealing with language and linguistic expression

After the “independence” of Flanders, the first core curriculum was developed in 1997 before it was

partially updated and expanded in 2010. The Ministry currently focuses on the clear definition of

objectives by reducing the core curriculum and by (re)formulating concrete and ambitious goals that

meet the needs of the 21st century. However, preprimary and primary schools still have to follow the

core curriculum of 2010. The final objectives of mainstream primary education contain final objectives

of Dutch listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

During preprimary Dutch reading education, the emphasis is on preparatory instruction that

increases phonemic awareness and graphemic identification while introducing concepts that will be

used in later education. For this group of students, the final objectives need not be attained. The school

must make visible efforts to work toward these objectives and to aim for them. These developmental

objectives for Dutch reading state preprimary children are:

• Able to recreate a message using visual material

• Able to understand messages related to concrete activities that are represented by symbols

• Able to distinguish letters from other marks in materials, in books, and on signs

• Prepared to spontaneously and independently look at books and other sources of information

intended for them

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 4

Reading instruction in the first year of primary school focuses on the acquisition of decoding skills

(technical reading) and includes stories and activities aimed at the development of reading

comprehension. From that moment on, instruction in comprehension gradually and systematically

increases, aiming to develop autonomous and critical readers. The final objectives for Dutch reading

in primary schools are as follows:

• Students are able to find information (level of processing = description) in:

o Instructions for a range of activities intended for them

o The data in tables and diagrams for public use

o Magazine texts intended for them

• Students are able to arrange information (level of processing = structuring) that is found in:

o School and study texts intended for them and instructions for school assignments

o Stories, children’s books, dialogues, poems, children’s magazines, and youth encyclopedias

intended for them

• Students are able to evaluate information based on their own opinion or on other sources (level

of processing=evaluating) such as:

o Letters and invitations intended for them

o Advertising texts that are directly related to their own world

Besides these objectives, the core curriculum also includes skills and strategies. Students have to be

able to use skills and strategies in relation to the necessary skills of listening, speaking, reading, and

writing in achieving the respective final objectives. Among other things, students must take into

account, as indicated in the final objectives:

• The total listening, speaking, reading, and writing situation

• The type of the text

• The level of processing

The core curriculum also emphasizes the development of language criticism, which is needed to

achieve the final objectives. Students must be prepared within a specific language context to reflect on:

• The use of standard, regional, and social language variations

• Particular attitudes, prejudices, and role play in language

• The rules of language behavior

• Certain language activities

• How certain points of view are adopted and/or revealed through language

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 5

Additionally, students must be prepared to:

• Reflect on the listening, speaking, reading, and writing strategies that are used

• In a specific context, reflect on the following aspects of language:

o Sound level

o Word level (creation of words)

o Sentence level (word order)

o Text level (simple structures)

Regarding these final objectives, students must be able to use appropriate terms, including:

• Sender, receiver, message, intent, situation

• Noun (plus article), diminutive, verb, stem, ending, prefixes and suffixes, other words

• Subject, verb ending, part of sentence

• Heading, paragraph

The Decree on Elementary Education of 25 February 1997 (Article 8) states: “On the basis of a

pedagogical project, schools must create an educational and learning environment in which pupils can

experience a continuous learning process. This environment must be adapted to the development

progress of the pupils.”

School boards (often in conjunction with the educational umbrella organizations) draw up their

own curriculum containing the final objectives stated in the core curriculum of the government. That

curriculum must be approved by the government upon the advice of the inspectorate. This curriculum

is a required guide for preprimary and primary education. The final objectives must be clearly

incorporated into curricula, work plans, and textbooks used by the schools. Most schools use a

curriculum drawn up by their association of schools (e.g., “GO! Education” for public schools in the

Flemish community, government aided public education of local authorities, or government aided

private education). These organizations have developed a comprehensive curriculum and

accompanying didactic suggestions to achieve the attainment targets of the core curriculum of the

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training.

Teachers, Teacher Education, and Professional Development

Teacher Education Specific to Reading

In her policy note for 2014–2019, the Flemish Minister of Education guaranteed sufficient,

professional, and motivated teaching personnel. To do so, she wants to strengthen initial teacher

education; actualize the basic competencies and the professional profile of teachers; realize a

professional, challenging, and varied educational career; and development for and support of teachers’

careers.

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 6

Initial teacher education includes a three year program for teachers of preprimary, primary, or the

first phases of secondary school, in which there is a distinction between teacher education courses and

their courses linked to the subject areas. In teacher education, however, there is no education program

specific to teaching reading in preprimary and primary schools; this is part of the general (language)

education of the primary school teacher.

Requirements for Ongoing Professional Development in Reading for Teachers

The Ministry takes no specific initiatives to enhance the competencies of teachers to teach reading. The

Decree on Quality of Education in 2009 clarifies that schools are responsible for providing good quality

education, which includes organizing professional development for teachers. Schools can organize

training on their own premises or in their school community, or work together with one or more

external organizations.

The educational umbrella organizations have their own Pedagogical Advisory Services (paid by the

government) to provide educational and methodological support to schools. These are among the most

important partners of most schools in quality assurance. The school counselors offer support to schools

within their network, including in-service training, support for self-evaluation, and quality assurance.

Many other training organizations offer various activities to enhance the competencies of teachers.

Although all these organizations can support professional development in teaching reading, this is no

official structure by the Flemish Community.

Reading Instruction in the Primary Grades

Instructional Materials

The freedom of education implies the autonomy of choosing instructional approaches. The only

suggestions regarding materials are in the curricula developed by the educational umbrella organizations.

Therefore, schools are free to use any materials the teachers prefer. Most schools use a series of textbooks

developed by an educational publishing house. These textbooks generally are written by teachers or

educational counselors. Most schools choose one series of textbooks to ensure continuity in all grades.

In the first grade, there is an emphasis on technical reading. Most schools use a specific method, including

a specific manual to learn the technicalities of letters, words, and sentences.

Generally, Flemish schools are adequately resourced to achieve the final objectives of the core

curriculum. In preprimary and primary schools, many tools are available to stimulate the development

of reading skills of students. Special education resources can be made available to students with a visual,

auditory, or physical disability who attend mainstream preprimary and primary education. These

resources include technical equipment, paper or digital transcripts or adaptations of lesson materials,

sign language interpreters, and copies of other students’ notes.9

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 7

Use of Technology

Information and communications skills are important for children and adults, and Information and

Communications Technology (ICT) is influencing teaching and learning methods. New cross-

curricular attainment targets and developmental objectives for ICT have been in use in preprimary and

primary school since 2007. All schools are equipped with modern computers and other technological

instruments, depending on their own needs and wishes. The tendency toward more inclusive

education challenges schools to use gradually more assistive technology tools for reading, such as text

to speech technology, audiobooks, optical character recognition software, graphic organizers, and

digital schoolboards.

Role of Reading Specialists

Reading specialists are rare in primary schools; typically, the classroom teacher is the only reading

specialist. If necessary, he or she can receive additional help from a remedial teacher, a care teacher, or

a care coordinator. For a limited time, students with special needs can be helped in regular primary

schools by a specialist teacher or a speech therapist inside or outside the classroom. However, the

current political emphasis on a language policy in every school leads to increasing attention in schools

to improve the quality of language teaching. A 2013 survey of the Flemish Ministry of Education on

Dutch reading and listening showed that 91 percent of Flemish students achieved the final objectives

of the core curriculum.10 Almost all the teachers involved spend time on reading instruction at least

once a week. Generally, school teams do not have a need for language or reading specialists for Dutch

instruction.

Second Language Instruction

An increasing number of students has limited or even absent knowledge of Dutch when starting

preprimary or primary education. For this reason, attention is paid to monitoring the knowledge of

Dutch and to adapting the provision of Dutch language training to the needs of the students. Schools

may use the Toolkit of Broad Evaluation Competences Dutch to measure competence in Dutch or set

up a language trajectory tailored for each student individually. Remediation within regular classes is

possible, but primary schools also may choose to organize language immersion classes that offer

intensive training in Dutch.

Students with Reading Difficulties

Diagnostic Testing

There is no structural or systematic testing of students to diagnose reading difficulties. The language

and reading curriculum does not prescribe assessment standards and testing methods. The schools

decide whether students have attained all the objectives and, thus, use their own tests and award

qualifications. Most teachers use formative assessments to follow up on the development of their

students.

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 8

In primary education, teachers are attentive in detecting reading difficulties. They follow students’

progress through continuous observation and periodic testing, particularly via tests linked to the series

of textbooks used. Once a reading difficulty is detected, teachers rely on the Pupil Guidance Center

during a periodic multidisciplinary consultation to confirm the initial diagnostics through specialized

testing. Most schools, however, do not wait for a formal diagnosis to support students with reading

difficulties.

Instruction for Children with Reading Difficulties

Students with reading difficulties often receive support in their own classroom as a result of formative

assessments and diagnostic testing. In general, teachers use differentiation to meet the reading

difficulties of their students. This support consists mostly of similar learning activities (i.e., same

materials, process, and instructions).

Students get more specific support in the case of persistent reading difficulties such as dyslexia.

Once these difficulties are determined, remedial teaching procedures can be implemented inside or

outside the classroom. Remedial teachers, care teachers, or a care coordinator mostly are responsible

for this additional support. In the case of a more severe, specific difficulty, schools use a thoroughly

individualized curriculum and individual assistance with consideration of students’ specific needs. In

recent years, learning difficulties, including reading difficulties, have been increasingly dealt with by

schools with curricular adaptations, remediation, compensation, or dispensation—STICORDI

measures (i.e., measures to STimulate, COmpensate, REmediate, DIfferentiate, and DIscharge, from

STImuleren, COmpenseren, Remediëren, DIfferentiëren, and DIspenseren).

Although many students with reading difficulties remain in regular primary education, the needs

of some students exceed the capacity of regular schools. Special education schools provide these

students with adapted education, training, care, and treatment. Teaching methods are highly

individualized in special education. In addition to the assistance of teachers and depending on their

difficulties, students receive social, psychological, orthopedagogical, medical, and/or paramedical

integrated assistance.

Monitoring Student Progress in Reading

In the Flemish community, education is explicitly regarded as more than training and instruction. In

addition to instructional content, a school also must convey values, attitudes, and convictions to its

(freely specified) pedagogical framework. This often leads to outcomes that do not easily lend

themselves to exact measurement. For this reason, there are no externally imposed tests and no

national examinations.

The freedom of education in Belgium includes the autonomy of Flemish schools in choosing

instructional methods and subsequently in testing their students. Nevertheless, the standards and the

procedure for the assignment of a primary school certificate are laid out in the education legislation.

At the end of elementary education, the class council autonomously decides whether a certificate of

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 9

primary education will be issued. The class council judges whether students have reached and mastered

the attainment targets for primary education. The Ministry has provided on its website an overview of

“tests for schools” to support schools in making these determinations. Three types of tests have been

available on this website since 2009:

• The Flemish version of the student monitoring system of the Dutch organization CITO (Centraal

Instituut voor Toetsontwikkeling, or the Central Institute for Assessment Development),

including tests of language and technical reading

• The Start of Primary Education Linguistic Skills Screening test (known by its Dutch acronym,

SALTO), a listening test to screen the Dutch language proficiency of students starting their first

grade of primary education

• The parallel tests developed by the Flemish Ministry within the framework of the periodical

survey on final objectives and development objectives, including a parallel test for Dutch reading

The schools decide whether students have attained the final objectives of the core curriculum. Most

teachers use tests linked to a series of textbooks and/or develop their own tests. On a more objective

level, most schools also use standardized tests for technical reading and reading comprehension.

Additionally, a follow-up system is applied independently from the series of textbooks in use to verify

student achievement level or learning gains. Students and their parents are regularly informed about

results, progress, learning behavior, and personal development through written school reports.

Many schools also use a test that includes reading at the end of Grade 4 or 6, provided by an

educational association of schools. Thus, individual teachers and school teams receive external data of

the achievements of their pupils. They confront these data with their own results to obtain a more

objective assessment. School teams also can use the data from these assessments to control the effects

of their education.

Since 2002, systematic surveys have been organized to enable authorities to get an overview of the

quality of the Flemish education system based on reliable and objective student performance data. In

2002, 2007, and 2013, the review focused on reading. The results of the latest survey were reassuring:

91 percent of Flemish students succeeded in acquiring the learning outcomes for reading in 2013.

Nevertheless, when considering that 2 or 3 percent of a birth cohort goes directly from Grade 5 or even

4 to a secondary school and that many students go to special education schools and in many cases do

not meet the attainment targets, this result is perhaps not reassuring at all. A parallel test of this survey

is available for schools to use for internal quality management, but the test is not suited for the

assessment of individual students.

Special Reading Initiatives

The Flemish Minister of Education and Training has undertaken several initiatives to enhance

students’ knowledge of and competence in the Dutch language and foreign languages (particularly

French, English, and German). The Ministry of Education aims to broaden literacy for students in

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 10

compulsory education and for adults in general—especially for those with a home language other than

Dutch. The targets of the Flemish Minister are the:

• Elaboration of a strong(er) language policy

• Amelioration of the didactical approach of languages, especially Dutch

• Review and actualization of the curriculum for Dutch

• Development of additional teaching materials

• Continuation and the extension of additional support for immigrants

• Organization of several actions to promote reading

Currently, the following initiatives of the Ministry promote literacy in the Flemish Community

include:

• Concept note on languages at school (2011)—Initiatives on enhancing the knowledge of the

Dutch language and of foreign languages such as French (possible from the third year of regular

primary school) and English or German (offered as initiation)

• Toolkit of Broad Evaluation Competences Dutch (2011)—A set of valid and reliable instruments

for teachers and schools to measure the competencies of Dutch

• New strategic plan called Raising Literacy (2012–2016)—Raising the level of literacy of the

population is the central mission of the plan

The Ministry of Education and Training develops general objectives, but it is up to schools, experts

from the field of action, and key organizations to take initiative. Currently, the following initiatives to

promote reading and literacy in the Flemish Community includes:

• Book Babies—A project to enhance the use of children’s books by parents during early childhood

• The Book Finder—A website that stimulates reading by assisting children and teenagers in

choosing books

• Readers Tipping Readers—A website with reading tips from readers to readers, describing the

general content of their favorite books

• The week of readout—A week in which adults read books to children

• The Month of Youth Books—An annual campaign that focuses on increasing the enjoyment of

reading from reading and viewing illustrations, using a quality offering

• Best book teacher—This annual prize aims to reward teachers who show a practical and daily

effort to include children’s books in class

• O Mundo, A Little World Library—A project to introduce the most beautiful picture books in

multicultural classrooms

• IBBY-Flanders—A project from a department of the International Board on Books for Young

People in Flanders that strives for children to have access to books

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 11

• The Book Jury—The Children and Youth Jury is a jury of children ages 4 to 16, in which jurors

get a list of books to review and sometimes meet in groups to talk about books; it is the biggest

reading group in Flanders

• Culture Connect (Cultuurconnect)—An organization with projects to support libraries and local

cultural and community centers, including reading projects

• Culture in Schools Starts Here—A Web portal organized by CANON Cultuurcel and Cultuurnet

Vlaanderen that provides an overview of cultural activities, partners, and support

• The LIST Project—A research-based project organized by the Hogeschool Utrecht in the

Netherlands and implemented by school counselors to improve reading instruction and follow a

three phase system consisting of regular support, remedial teaching, and intensive remedial

teaching11

Use and Impact of PIRLS

In general, the PIRLS 2006 findings received little public attention in Flanders, with information

related to the study being made available mainly to the participating schools, policymakers, and

educational researchers. When the results were first released, a few newspaper reports (e.g., in De

Standaard) and radio items featuring the findings reached the general public. Later, the fact that only

a small percentage of students were positioned as advanced readers attracted commentary in journals

(e.g., in Onderwijskrant) and led to various groups such as parents of gifted children engaging in

actions directed at influencing educational policy.12

The PIRLS results also have been mentioned in various other contexts over time, such as in recent

discussions on reform of secondary education. In a document setting out government policy for

education for 2009 to 2014, the Minister of Education stated that “our well-performing children do not

perform very well.”13 This comment was a direct reaction to the PIRLS 2006 results.

A follow-up study conducted by Driessens and Faes on the impact of PIRLS 2006 in participating

schools found only limited evidence of influence on school policy and practice relating to reading.14

Driessens and Faes were particularly interested in how schools interpreted and used the school

feedback reports. Based on the findings of their quantitative and qualitative analyses, they concluded

that although school principals and some other school staff read the feedback report for their school,

most of these readers had difficulty interpreting the feedback results. This difficulty may partly explain

why only a few principals used these data to adjust school policy. Driessens and Faes also noted that

schools generally were only motivated to address issues highlighted by the data when stakeholders such

as parents exerted pressure on them to do so.

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 12

Suggested Readings

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training. (2013). Beter leren lezen en schrijven—Handvatten voor een effectieve

aanpak in het basis- en secundair onderwijs [Learning to read and write better—Keys to an effective approach in

primary and secondary education]. Retrieved from https://www.vlaanderen.be/nl/publicaties/detail/beter-leren-

lezen-en-schrijven-1

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training. (2014). Peiling Nederlands—Lezen en luisteren in het basisonderwijs.

[Periodical Assessment Dutch—Reading and listening in Elementary Education]. Retrieved from

https://www.vlaanderen.be/nl/publicaties/detail/peiling-nederlands-lezen-en-luisteren-in-het-basisonderwijs

Nusche, D., Miron, G., Santiago, P., & Teese R. (2015). OECD reviews of school resources: Flemish Community of

Belgium 2015. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264247598-en

European Literacy Policy Network. (2016). Literacy in Belgium (Flanders): Country report. Retrieved from

http://www.eli-net.eu/fileadmin/ELINET/Redaktion/user_upload/Belgium_Flanders_Short_Report1.pdf

References

1

Flemish Government. (2016). VRIND 2016: Vlaamse regionale indicatoren [VRIND 2016: Flemish regional

indicators]. Retrieved from http://regionalestatistieken.vlaanderen.be/vrind-2016

2

The Belgian Constitution. (2014). Retrieved from

http://www.dekamer.be/kvvcr/pdf_sections/publications/constitution/GrondwetUK.pdf

3

Crevits, H. (2014). Beleidsnota 2014–2019: Onderwijs [Policy note 2014–2019]. Retrieved from

https://www.vlaanderen.be/nl/publicaties/detail/beleidsnota-2014-2019-onderwijs

4

Nusche, D., Miron, G., Santiago, P., & Teese R. (2015). OECD reviews of school resources: Flemish Community

of Belgium 2015. Retrieved from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/oecd-reviews-of-school-resources-

flemish-community-of-belgium_9789264247598-en

5

Flemish Government. (2016). Conceptnota maatregelen basisonderwijs en eerste graad [Concept note: Measures

for elementary education and first grade of secondary education]. Retrieved from

https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/VR_2016_3105_DOC%200538_1.pdf

6

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training. (2016). Sterker basisonderwijs met extra aandacht voor taal

[Stronger elementary education with an emphasis on language]. Retrieved from

https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/sterker-basisonderwijs-met-extra-aandacht-voor-taal

7

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training. (2016). Meertaligheid als realiteit op school: Onderzoek

[Multilingualism as a reality on schools: Research]. Retrieved from

https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/meertaligheid-als-realiteit-op-school-onderzoek

8

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, AKOV. (2010). Ontwikkelingsdoelen en eindtermen voor het

gewoon basisonderwijs [Developmental objectives and attainment targets in primary education]. Retrieved from

https://www.vlaanderen.be/nl/publicaties/detail/ontwikkelingsdoelen-en-eindtermen-voor-het-gewoon-

basisonderwijs-informatie-voor-de-onderwijspraktijk

9

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training. (n.d.). Speciale onderwijsleermiddelen [Special education learning

resources]. Retrieved from http://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/speciale-onderwijsleermiddelen

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 13

10

Flemish Ministry of Education and Training. (2014). Peiling Nederlands—Lezen en luisteren in het

basisonderwijs [Periodical Assessment Dutch—Reading and listening in Elementary Education]. Retrieved from

https://www.vlaanderen.be/nl/publicaties/detail/peiling-nederlands-lezen-en-luisteren-in-het-basisonderwijs

11

Houtveen, A.A.M., Smits, A.E.H., & Brokamp, S.K. (2010). Lezen is weer lezen. Achtergronden en

ontwikkelingen in de eerste twee projectjaren van het LeesInterventie-project voor Scholen met een Totaalaanpak

(LIST) [Reading is reading again. Background and development in the first two project years of the Reading

Intervention Project for Schools with a Global Approach]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Hogeschool Utrecht.

12

Liu, H., Knipprath, H., & Van Damme, J. (2012). The impact of PIRLS 2006 in Belgium (Flemish). In: K.

Schwippert & J. Lenkeit (Eds.), Progress in reading literacy in national and international context: The impact of

PIRLS 2006 in 12 countries (pp. 61–74). Münster, Germany: Waxmann.

13

Smet, P. (2009). Beleidsnota onderwijs 2009–2014 [Policy note on education 2009–2014]. Retrieved from

http://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/docs/stukken/2009-2010/g202-1.pdf

14

Driessens, A., & Faes, K. (2008). Schoolfeedback: Analyse van de interpretatie en aanwending van

schoolfeedbackrapporten n.a.v. deelname aan het PIRLS-onderzoek [School feedback: An analysis of the

interpretation and use of school feedback reports based on PIRLS 2006]. (Unpublished master’s thesis).

University of Leuven, Belgium.

PIRLS 2016 ENCYCLOPEDIA

BELGIUM, FLEMISH COMMUNITY 14

You might also like

- A Multimodal Framework For Analyzing Websites As Cultural ExpressionsDocument19 pagesA Multimodal Framework For Analyzing Websites As Cultural ExpressionsElaine Pereira AndreattaNo ratings yet

- Inventions That Changed The World A Reading Comprehension For Grade 5Document2 pagesInventions That Changed The World A Reading Comprehension For Grade 5Ghina ItaniNo ratings yet

- Education System in DenmarkDocument25 pagesEducation System in DenmarkAc Malonzo0% (1)

- Lesson Plan in Reading and Writing Grade 11-STEM I. ObjectivesDocument7 pagesLesson Plan in Reading and Writing Grade 11-STEM I. Objectivesjane de leon100% (1)

- Identification of The Historical Importance of The TextDocument13 pagesIdentification of The Historical Importance of The TextKawhileonard Leonard88% (17)

- The History and Present of The Finnish Education SystemDocument13 pagesThe History and Present of The Finnish Education SystemAnonymous hljEo9GDKt100% (2)

- Introduction To TelematicsDocument3 pagesIntroduction To TelematicsRivegel BaclayNo ratings yet

- Key Features of The Education System: Educational CompetenceDocument8 pagesKey Features of The Education System: Educational CompetencecioritaNo ratings yet

- Key Features of The Education System: Educational CompetenceDocument5 pagesKey Features of The Education System: Educational CompetencecioritaNo ratings yet

- Belgium Education Report (2006)Document7 pagesBelgium Education Report (2006)National Center on Education and the EconomyNo ratings yet

- Education System in BahrainDocument5 pagesEducation System in BahrainJB GandezaNo ratings yet

- Educational System in BelgiumDocument18 pagesEducational System in BelgiumRigor Martin100% (1)

- Belgium: Pujan Thakar 17U050 Section IiDocument23 pagesBelgium: Pujan Thakar 17U050 Section IiRia MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Eurydice 2011 - National System Overview On Systems in Europe and Ongoing Reforms (Germany)Document10 pagesEurydice 2011 - National System Overview On Systems in Europe and Ongoing Reforms (Germany)luiz carvalhoNo ratings yet

- 2003 The Educational Structure of The German School SystemDocument34 pages2003 The Educational Structure of The German School SystemchakritNo ratings yet

- Education System of BELGIUMDocument10 pagesEducation System of BELGIUMrachel reparepNo ratings yet

- Comparing Finland's Education SystemDocument30 pagesComparing Finland's Education SystemYM BaitNo ratings yet

- Education System in GermanyDocument27 pagesEducation System in GermanyBernadette Sambrano EmbienNo ratings yet

- Education in The NetherlandsDocument13 pagesEducation in The NetherlandsAbdul HanifNo ratings yet

- Key Features of The Dutch Education SystemDocument8 pagesKey Features of The Dutch Education SystemcioritaNo ratings yet

- B2b&agrofood Final ProjectDocument12 pagesB2b&agrofood Final ProjectEduard MagurianuNo ratings yet

- Arts Education in Finland: Dutch - Scandinavian Exchange On Cultural EducationDocument9 pagesArts Education in Finland: Dutch - Scandinavian Exchange On Cultural EducationFleur de MoisiNo ratings yet

- Belgian Education Innovations (2006)Document3 pagesBelgian Education Innovations (2006)National Center on Education and the EconomyNo ratings yet

- Education Policy in FinlandDocument11 pagesEducation Policy in FinlandWilma MarquezNo ratings yet

- German Education SystemDocument9 pagesGerman Education Systemrhona toneleteNo ratings yet

- Country AnalysisDocument21 pagesCountry AnalysisGLORIA MAY ORGANONo ratings yet

- Preschool Education in Sweden - LLL - Dec 08Document29 pagesPreschool Education in Sweden - LLL - Dec 08Julie HolmesNo ratings yet

- Curriculum, Subjects, Number of HoursDocument5 pagesCurriculum, Subjects, Number of HoursAna MariaNo ratings yet

- INGLESDocument46 pagesINGLESuniversidadsheilaNo ratings yet

- The Maltese Education SystemDocument4 pagesThe Maltese Education SystemMaltesers1976No ratings yet

- Luxembourg's Education SystemDocument6 pagesLuxembourg's Education SystemaviNo ratings yet

- The Education System in The Federal Republic of Germany 2012/2013Document10 pagesThe Education System in The Federal Republic of Germany 2012/2013kharismaNo ratings yet

- Essay On The Finnish Educational SystemDocument4 pagesEssay On The Finnish Educational SystemjipduynNo ratings yet

- Bilingual EducationDocument22 pagesBilingual EducationoanadraganNo ratings yet

- Key Features of The Education SystemDocument5 pagesKey Features of The Education SystemDC.075No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Education in FinlandDocument12 pagesEntrepreneurship Education in FinlandbrmartiNo ratings yet

- Primary School For Gifted Children A Dan - OdtDocument10 pagesPrimary School For Gifted Children A Dan - OdtCăuniac Paladi ManuelaNo ratings yet

- Ringkasan Resume 10Document2 pagesRingkasan Resume 10Naim ramlismeNo ratings yet

- Education System in FinlandDocument6 pagesEducation System in FinlandAndre AlagastinoNo ratings yet

- OverviewDocument5 pagesOverviewJessica ArdeliaNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine National Aerospace University "Kharkiv Aviation Institute"Document28 pagesMinistry of Education and Science of Ukraine National Aerospace University "Kharkiv Aviation Institute"matttaNo ratings yet

- Europian Model of CurriculumDocument25 pagesEuropian Model of CurriculumFrances Diane Arnaiz SegurolaNo ratings yet

- Education WikepediaDocument292 pagesEducation WikepediaRuth OyeyemiNo ratings yet

- UCSP Module 8Document12 pagesUCSP Module 8Eann JohnaNo ratings yet

- SEN AssignementDocument7 pagesSEN Assignementchisanga cliveNo ratings yet

- National Summary Sheets On Education System in Europe and Ongoing ReformsDocument12 pagesNational Summary Sheets On Education System in Europe and Ongoing Reformsjso-No ratings yet

- Danish Education SystemDocument16 pagesDanish Education SystemScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- The Role of Government: Formal EducationDocument10 pagesThe Role of Government: Formal EducationgeetukumariNo ratings yet

- Finnish Education SystemDocument5 pagesFinnish Education SystemZeycan KAMANo ratings yet

- National System Overviews On Education Systems in Europe and Ongoing ReformsDocument13 pagesNational System Overviews On Education Systems in Europe and Ongoing ReformsGeorgiana MedeleanuNo ratings yet

- Obwalden: The 26 Cantons of Switzerland Are The of TheDocument2 pagesObwalden: The 26 Cantons of Switzerland Are The of TheСоня БабичNo ratings yet

- Part-Time Education in The ArtsDocument4 pagesPart-Time Education in The Artsapi-219845821No ratings yet

- Education in FinlandDocument7 pagesEducation in Finlandrhona toneleteNo ratings yet

- Morocco TIMSS 2011 Profile PDFDocument14 pagesMorocco TIMSS 2011 Profile PDFالغزيزال الحسن EL GHZIZAL HassaneNo ratings yet

- Secondary Education in Comparative Perspective: Unit 6 Corse Code: 8624 B. Ed. Unit 6 Corse Code: 8624 B. EdDocument47 pagesSecondary Education in Comparative Perspective: Unit 6 Corse Code: 8624 B. Ed. Unit 6 Corse Code: 8624 B. EdRubeenaNo ratings yet

- Education in EuropeDocument3 pagesEducation in EuropeAdri DaswinNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Vs BelgiumDocument27 pagesPakistan Vs BelgiumTanzeela BashirNo ratings yet

- ENG218 Assignment 3Document5 pagesENG218 Assignment 3Kim ErichNo ratings yet

- Education in EnglandDocument21 pagesEducation in EnglandSimona AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Finland Homework StatisticsDocument4 pagesFinland Homework Statisticsafnaxfkjehonka100% (1)

- Finland Inclusion 07Document12 pagesFinland Inclusion 07fairuz fadhilaNo ratings yet

- Education in The UK: Guide To British and American Culture, For Academic Purposes Only)Document3 pagesEducation in The UK: Guide To British and American Culture, For Academic Purposes Only)The Sun and The SeaNo ratings yet

- Info InglesDocument3 pagesInfo InglesBrenda BustamanteNo ratings yet

- Education in Ireland: Challenge and ChangeFrom EverandEducation in Ireland: Challenge and ChangeSheelagh DrudyNo ratings yet

- What Does it Mean to be Four?: A practical guide to child development in the Early Years Foundation StageFrom EverandWhat Does it Mean to be Four?: A practical guide to child development in the Early Years Foundation StageNo ratings yet

- Flemish Language in An Era of Globalisation: June 2014Document8 pagesFlemish Language in An Era of Globalisation: June 2014Useful StuffNo ratings yet

- Flemish Dutch: 1. Lieke: Dagget Wet (Axl Peleman)Document47 pagesFlemish Dutch: 1. Lieke: Dagget Wet (Axl Peleman)Useful StuffNo ratings yet

- The Michelin Schools and The Natural Method: How Georges Hébert's Physical Education Temporarily Prevails Over SportDocument21 pagesThe Michelin Schools and The Natural Method: How Georges Hébert's Physical Education Temporarily Prevails Over SportUseful StuffNo ratings yet

- Cha - 15 - Ismailova 253214 2017 08 28 13 57 10Document16 pagesCha - 15 - Ismailova 253214 2017 08 28 13 57 10Useful StuffNo ratings yet

- Updated ELSO Pediatric Guidelines 1617997662Document13 pagesUpdated ELSO Pediatric Guidelines 1617997662Useful StuffNo ratings yet

- Err 228Document46 pagesErr 228Useful StuffNo ratings yet

- Tuckman's Stages of Group Development: Introduction: The Model Describes Inevitable andDocument11 pagesTuckman's Stages of Group Development: Introduction: The Model Describes Inevitable andSuman KumarNo ratings yet

- Case 2 mgt368 Group 6Document6 pagesCase 2 mgt368 Group 6abdullah al nuraneeNo ratings yet

- RationaleDocument5 pagesRationaleapi-487574225No ratings yet

- Approaching A Forensic TextDocument10 pagesApproaching A Forensic TextKhadija SaeedNo ratings yet

- Rubric For ManifestoDocument3 pagesRubric For Manifestoapi-316144468No ratings yet

- Reported-Speech QUESTIONSDocument21 pagesReported-Speech QUESTIONSKhumarNo ratings yet

- Eled 330 Lesson Plan AssignmentDocument11 pagesEled 330 Lesson Plan Assignmentapi-541678284No ratings yet

- IkeaDocument5 pagesIkeaAyushi AggarwalNo ratings yet

- OOAD - Ch.03 - Sequence DiagramDocument9 pagesOOAD - Ch.03 - Sequence DiagramEL DORADONo ratings yet

- Is The Beauty Industry Growing? Especially Ecommerce Cosmetics in 2021 and Beyond? AbsolutelyDocument54 pagesIs The Beauty Industry Growing? Especially Ecommerce Cosmetics in 2021 and Beyond? Absolutelywidiaji100% (2)

- University of Minadanao Peñaplata College Island Garden City of SamalDocument61 pagesUniversity of Minadanao Peñaplata College Island Garden City of SamalNorie Rosary67% (3)

- DG Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesDG Lesson Planapi-306933574No ratings yet

- System Trading TREND ROOMDocument6 pagesSystem Trading TREND ROOMTejas V NanduNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary BuilderDocument2 pagesVocabulary Builderapi-260205329No ratings yet

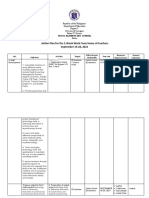

- Action Plan For The 2-Week Work From Home of Teachers September 14-28, 2021Document3 pagesAction Plan For The 2-Week Work From Home of Teachers September 14-28, 2021Aca GealoneNo ratings yet

- Teste de Conhecimento: Avalie Sua AprendizagemDocument3 pagesTeste de Conhecimento: Avalie Sua AprendizagemBruno SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tefl AssignmentDocument5 pagesTefl AssignmentLeeLowersNo ratings yet

- Mood in English Grammar With Examples PDFDocument4 pagesMood in English Grammar With Examples PDFhemisphereph2981No ratings yet

- How To Organise A Public Lecture: 1. Getting StartedDocument6 pagesHow To Organise A Public Lecture: 1. Getting Startedsneakstones9540No ratings yet

- Paul Alexander: Lead UX DesignerDocument1 pagePaul Alexander: Lead UX DesignersherNo ratings yet

- Syllabus: Cambridge IGCSE First Language Arabic 0508Document16 pagesSyllabus: Cambridge IGCSE First Language Arabic 0508Alfredo Martín MartínezNo ratings yet

- A Study of Thomas CookDocument2 pagesA Study of Thomas CookKapil ShereNo ratings yet

- Ax2009 Enus HRM 00 PDFDocument4 pagesAx2009 Enus HRM 00 PDFRamiro AvendañoNo ratings yet

- ICT Project For Social Change - Lesson 4Document61 pagesICT Project For Social Change - Lesson 4Maria MaraNo ratings yet

- The Collins Writing ProgramDocument11 pagesThe Collins Writing Programctaylor866No ratings yet