Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 171.50.140.117 On Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 171.50.140.117 On Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

Uploaded by

Chill FilmsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 171.50.140.117 On Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 171.50.140.117 On Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

Uploaded by

Chill FilmsCopyright:

Available Formats

The Lost Courses of the Saraswati River in the Great Indian Desert: New Evidence from

Landsat Imagery

Author(s): Bimal Ghose, Amal Kar and Zahid Husain

Source: The Geographical Journal , Nov., 1979, Vol. 145, No. 3 (Nov., 1979), pp. 446-451

Published by: The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British

Geographers)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/633213

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wiley and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are

collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE LOST COURSES OF THE SARASWATI RIVER

IN THE GREAT INDIAN DESERT:

NEW EVIDENCE FROM LANDSAT IMAGERY

BIMAL GHOSE, AMAL KAR and ZAHID HUSAIN

Interpretation of landsat imagery and field investigation in the western part of

Jaisalmer district in India have revealed some hitherto unknown abandoned courses of

the former Saraswati river. It has been suggested that these courses were alive before the

Saraswati occupied the Raini or the Wahinda courses, and contributed to the alluviation

of the region. The subsurface water in the region is contributed mainly by the

Himalayan precipitation flowing subterraneously through the former courses of the

Saraswati.

MUCHThe

river. WORK has already

river originates been

in the doneHills

Siwalik on the lost 1)courses

(see Fig. of the Saraswati

ofthe Himalayan

mountain range and flows through the Punjab and Haryana States and then

through the northern part of Rajasthan (Ganganagar district) where it dries out

leaving a wide valley extending roughly from Hanumangarh through Pilibangan

and Anupgarh towards Fort Abbas in Pakistan. For most ofthe early workers on

the Saraswati, the inspiration to trace out the course ofthe river was provided by

the presence of this dry valley and they were motivated by an urge either to

explore the river beyond its visible length of dry valley or to unearth the relics of

prehistoric cultures in the region. The present authors' interest in the Saraswati

was aroused, however, when dealing with the distribution of alluvium and the

source of the perennial supply of subsurface water in the western part part of the

Great Indian Desert, where the annual rainfall is so meagre and erratic (less than

150 mm) that it cannot contribute substantially to the perennial wells ofthe area.

During their search, the authors came across some hitherto unknown courses of

the Saraswati which are described in the present article.

Literary sources

The Saraswati has been described as a mighty Himalayan river in the earliest

and authentic Sanskrit literature of the sub-continent, the Rigveda (Wilson,

1854). The earliest available report of the drying up of this river is in the epic

literature of the Mahabharata where it says that the river went underground at

Binasana, near the present town of Sirsa. The Mahabharata also mentions the

reappearance of the Saraswati at three places downstream, then known as

Chamasodbheda, Sirodbheda and Nagodbheda (Dey, 1927). The present

geographical locations of these places are not known to the authors. None of the

ancient Sanskrit literature, however, systematically described the course of this

river from its source to its terminus.

From the last quarter of the nineteenth century, a number of authors have

written of their attempts to explore the former course of the Saraswati and have

concluded that the river used to flow through the Raini and the Wahinda rivers

and then through the eastern Nara and Hakra in the Sind province of Pakistan to

the Rann of Kutch (Oldham, 1893; Wadia, 1938; Ali, 1942; Stein, 1942;

-> The authors of this paper are members of the Central Arid Zone Research Institute at Jodhpur,

India.

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE LOST COURSES OF THE SARASWATI RIVER 447

Krishnan, 1960; Wilhelmy, 1969). Allchin, Goudie and Hegde (197

summarized the findings of these authors in the following way:

'Evidence from many sources, including that of archaeological rem

associated with old river courses, indicates that a major river, stemming

from the same sources as the present Sutlej, flowed through Nort

Rajasthan, Bahawalpur and Sind?to the southeast ofthe present cours

Sutlej and the Indus?in the third to second millennium BC. This river, k

as the Saraswati in its upper course, at different times either joined the

course of the Indus in Sind, or found its way independently into the Ar

Sea via Rann of Kutch' (p. 198).

The present authors, on the basis of their interpretation of aerial photo

Ganganagar* ;.._..?**"" ,.?**

Hanumangarh, <"^^ ^4

Pilibangan^'-A* ~~^<*< 7-','

AnIipgbrh>V^ Surat9arh ^'Z^T.:.,

^V '" ,'Nohar

Bikaner ? / :x28"NH

?ambhar Lake

Jaipur

/\jmer

-Former courses of the river

26H

J^ Earliest course of the river

__? _ Successive major courses of the river

Existing drainage channels

Other former drainage channels

Salt marsh

Mountains

Fig. 1. The shifting courses ofthe Saraswati River

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

448 THE LOST COURSES OF THE SARASWATI RIVER

and LANDSAT imagery, have suggested in an earlier

that the Saraswati used formerly to flow through a mo

Rajasthan part of the desert when the Luni river w

Subsequently the river shifted its course to the west se

its contact with the Luni (Fig. 1). The suggestion was th

that when this severance from the Luni occurred the r

Rann of Kutch through another southerly course whose

Pakistan as Hakra or Nara' (Ghose et al., 1978). Howev

of that article, some more information has been collect

of the Saraswati river. The present article emphasizes w

that when the river severed itself from the Luni and sh

occupy the Raini-Wahinda-Nara-Hakra course in Pak

through another channel running through the present

the Jaisalmer district in India. The Raini-Wahinda-

occupied by the Saraswati later. The study is based on i

imagery and field verification in the Indian part of the

Evidence from LANDSAT imagery

The black and white LANDSAT imagery of the we

contiguous part of Pakistan, taken in band 7 (near in

year 1972, clearly indicates the wide valley of the

Suratgarh through Anupgarh to Fort Abbas and Ahmad

Anupgarh another wide belt of discontinuous patche

southwestward up to Sakhi (Plate V). From Sakhi, the r

can be traced towards the west, but a closer look at

presence of a narrow zone of saline/alkaline fields,

overlying sand dunes, extending up to Khangarh. To

narrow strip of green vegetation, producing a sligh

surroundings, can be identified. It runs from Islamgarh

Ghantial, Shahgarh, Babuwali and Rajar to Mihal Mungr

the Saraswati from the Himalaya to the Rann of Kutch

relations with the Luni. South of Mihal Mungra, the co

the present Hakra channel and there are indications of

Hakra channel (Plate VI). This signifies that the co

might have been somewhere to the west of the pre

authors did not trace out that course between the Hakr

Holmes (1968) has reconstructed and described the fo

that region from his interpretation of aerial photograp

It has also been possible to trace out from the LANDSA

minor westward shifts in the course from Ghotaru sou

courses of the Saraswati could be identified further to

and Sandh, the remnants of which are now known as t

rivers. Here also the river shifted its course several time

to the east of the Wahinda river, through Mundo (F

ceased to flow southward and met the Sutlej to the

Evidence from field investigation

The field investigation to confirm the existence of th

Saraswati river was carried out in the Indian part ofthe

to Shahgarh. The abandoned, earlier courses ofthe tr

shown in Figure 2, were also verified from field i

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE LOST COURSES OF THE SARASWATI RIVER 449

Fig. 2. Former courses of the Saraswati River

Pokaran, Jaisalmer and Myajlar. It was found that the area through which th

Saraswati was traced supports lush green vegetation, even during the hot Indian

summer months. The area is covered with sand dunes of 40 to 50 m in heigh

transverse to the north of Tanot and longitudinal to its south. Although th

interdunal areas are generally covered with thick sandy deposits, those to th

north of Tanot are relatively free from sand and the surface is silty. This silty so

is used by the local inhabitants for making sun-dried bricks. The few wells along

the tract provide additional evidence in support of the earlier course of the

Saraswati. At Dharmi Khu, Ghantial, Ghotaru and to the west of Shahgarh th

wells have sweet water at 30 to 40 m depth. The water has been struck in riverin

materials and the discharge is good. The well at Ghantial, for example, supports

more than 2000 livestock consisting of camels, cattle, sheep and goats and there

no report of the well drying up even during severe droughts. The other wel

mentioned above also do not dry up in the summer months, suggesting a

continuous supply of water from the upstream side. In contrast, the wells away

from the old courses ofthe Saraswati river have insufficient water and are most

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

450 THE LOST COURSES OF THE SARASWATI RIVER

brackish or saline (e.g. at Tanot). Hence, it may be sugg

subsurface hydrology of the region is mainly controlled b

catchment of the Saraswati in the Himalaya and adjoining

present meagre rainfall (less than 150 mm per annum) in t

Great Indian Desert.

Possible causes of the rivefs westward shift

The gradual westward shift of the river was explained earlier by the present

authors (Ghose et al., 1968) as due to the advancing sand and aridity. However,

the possibilities of mild tectonic movement, occurring at least during the late

Quaternary period, cannot be ruled out as an additional cause for such shifting.

Although no stratigraphic record is available to enable one to be definite about

such tectonism, there have been earth movements in the Himalaya and the Rann

of Kutch in the recent historical period, indicating instability in both these areas.

For example, in the year 1819 there was a sudden uplift of land across the mouth

ofthe river causing a natural barrier, several metres high, called the 'Allah Band'*

(Wadia, 1975). The headwater region of the river, the Siwalik Hills, is also

tectonically unstable (Wadia, 1975). Instability in any of these zones may have

affected the river's courses in addition to climatic changes and consequent aridity.

It is also not ruled out that sometimes the Sutlej (the Satadru of the ancient

Sanskrit literature) also contributed water to the flow of the Saraswati, possibly

near places like Jakhal, and Hanumangarh (Fig. 1). However, the role of the

Sutlej in this region is not discussed in this article.

Whatever may be the cause of the shifting courses of the Saraswati, those

courses of the river traced to the east of the Raini and the Wahinda may provide

clues to the early settlements and civilization in the region. The possibility ofthe

Tndus valley' civilization spreading into the present Thar desert has recently been

pointed out by Mughal (1979), with supportive evidence of traces of

pre-Harappan, Harappan and post-Harappan settlements along a dry valley of

the Saraswati from Fort Abbas to Derawar Fort.

Conclusion

A major former, abandoned course ofthe Saraswati river has been discovered

through the present extreme desert terrain of Jaisalmer. This course was in

existence before the Saraswati occupied the Wahinda or the Raini courses.

Afterwards, the river gradually shifted westward and occupied the Wahinda and

the Raini courses. This was followed by another westward shift when the river no

longer debouched into the Rann of Kutch independently, but met the Sutlej near

Ahmedpur East. This last course has also been abandoned and fans out on the

alluvial plain before reaching the Sutlej. We suggest that the alluvium in the

extreme western part of the desert was contributed by the Saraswati river, and

that the subsurface water in the western part of this desert is mainly derived from

precipitation in the Himalaya flowing subterraneously through the former

courses of the Saraswati.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their gratitude to Dr H. S. Mann, Director, and to Dr

K. A. Shankarnarayan, Head of the Basic Resources Studies Division, of the

Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, both of whom encouraged them

and provided facilities to carry out this research.

*Literally meaning a dam created by the Almighty.

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE LOST COURSES OF THE SARASWATI RIVER 451

References

Ali, S. M. 1942 The problem of desiccation ofthe Ghaggar plains. Calcutta Geographical Review 4,1.

Allchin, B., Goudie, A., and Hegde, K. 1978 The Prehistory and Palaeogeography ofthe Great Indian

Desert. London: Academic Press.

Dey, N. L. 1927 (reprinted 1979) The Geographical Dictionary of Ancient and Mediaeval India. Ne

Delhi: Cosmo Publications.

Ghose, B., Kar, Amal and Husain, Zahid 1978 Comparative role ofthe Aravalli and the Himala

river systems in the fluvial sedimentation of the Rajasthan desert. Paper presented at t

Symposium on Tertiary and Quaternary climatic and environmental changes, Tenth

International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, December 1978 (to

published).

Holmes, D. A. 1968 The recent history ofthe Indus. GeogrlJ. 134, 3: 367-82.

Krishman, M. S. 1960 Geology of India and Burma. Madras: Higginbothams.

Mughal, M. Rafique 1979 New archaeological evidence from Bahawalpur. Paper presented at the

International Seminar on the Indus Valley Civilization: Karachi. (Mimeo.).

Oldham, C. F. 1893 The Saraswati and the lost river ofthe Indian desert. Journal ofthe Royal Asiatic

Society (N.S.) 34: 49-76.

Stein, A. 1942 A survey of ancient sites along the 'lost' Saraswati river. GeogrlJ. 99: 173-82.

Wadia, D. N. 1938 The post-Tertiary hydrography of northern India and the changes in the courses

of its rivers during the last geological epoch. Proc. National Institute of Sciences of India: 387-94.

Wadia, D. N. 1975 Geology of India. New Delhi: Tata-McGraw Hill Publ. Co.

Wilson, H. H., Cowell, E. B., and Webster, W. F. 1854 (Reprinted 1977) The Rigveda Sanhita.

Vols. I to VII. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications.

Wilhelmy, H. 1969 Das Urstromtal am Ostrand der Indusebene und der Sarasvati-Problem

Zeitschrift fur Geomorphologie, Supp. 8: 76-93.

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LANDSAT photograph showing the suggested course of the Saraswati River

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 2021 20:54:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LANDSAT photograph showing the suggested course of the Saraswati River in the area

of the Hakra channel

This content downloaded from

171.50.140.117 on Thu, 05 Aug 20hu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Comparative Analysis of PD 957 & BP 220Document4 pagesComparative Analysis of PD 957 & BP 220berolyan0690% (10)

- German Atv-Dvwk Rules and StandardsDocument50 pagesGerman Atv-Dvwk Rules and StandardsMehmet Emre Bastopcu100% (14)

- The Mechanics of Earthquakes and FaultingDocument7 pagesThe Mechanics of Earthquakes and FaultingcmendozatNo ratings yet

- IB Geography Oceans Case StudiesDocument6 pagesIB Geography Oceans Case StudiesMarc Wierzbitzki0% (1)

- Origin of Early Harappan Cultures in The Sarasvati Valley - Recent Archaeological Evidence and Radiometric DatesDocument67 pagesOrigin of Early Harappan Cultures in The Sarasvati Valley - Recent Archaeological Evidence and Radiometric Datesdharma next100% (7)

- River SysDocument30 pagesRiver Syssadananddubey1987No ratings yet

- Satellite Images As Scientific Tool For Sarasvati Palaeochannel and Its Archaeological Affinity in NW India - Bidyut K Bhadra & JR SharmaDocument31 pagesSatellite Images As Scientific Tool For Sarasvati Palaeochannel and Its Archaeological Affinity in NW India - Bidyut K Bhadra & JR SharmaSrini KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- Vedic Saraswati A.b.roy and S.R.jakharDocument8 pagesVedic Saraswati A.b.roy and S.R.jakharMool AryaNo ratings yet

- NadiDocument125 pagesNadiRajneesh VyasNo ratings yet

- Tracing The Origin of Saraswati River To Tons and Baspa RiversDocument5 pagesTracing The Origin of Saraswati River To Tons and Baspa RiversDr. Ashok MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Sarasvati RiverDocument30 pagesSarasvati RiverDeepak Ramchandani100% (1)

- Scientific Reason For Drying of River SARASWATIDocument11 pagesScientific Reason For Drying of River SARASWATIParas PrateekNo ratings yet

- On The Existence of A Perennial River in The Harappan HeartlandDocument7 pagesOn The Existence of A Perennial River in The Harappan Heartlandgautam mitraNo ratings yet

- Sara Swat Hi River ResearchDocument180 pagesSara Swat Hi River ResearchNagaraja Rao Mukhirala100% (1)

- 11 - Chapter 3Document28 pages11 - Chapter 3undyingNo ratings yet

- Possible Contribution of River Saraswati in Groundwater Aquifer System in Western Rajasthan, IndiaDocument6 pagesPossible Contribution of River Saraswati in Groundwater Aquifer System in Western Rajasthan, Indiasagar anandNo ratings yet

- Michel Danino - The Lost RiverDocument14 pagesMichel Danino - The Lost RiverMarijaDomovićNo ratings yet

- Saraswati - The Ancient River Lost in The DesertDocument8 pagesSaraswati - The Ancient River Lost in The DesertPooja ChandramouliNo ratings yet

- The Lost Vedic River SarasvatiDocument20 pagesThe Lost Vedic River SarasvatigabbahoolNo ratings yet

- Rigvedic Sarasvati Myth and RealityDocument10 pagesRigvedic Sarasvati Myth and RealityNikhil SajiNo ratings yet

- Sarasvati River: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument18 pagesSarasvati River: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaonlymusic16No ratings yet

- Saraswati As Himalayan River Val Diya 2013Document13 pagesSaraswati As Himalayan River Val Diya 2013kalyan974696No ratings yet

- The Sarasvati River Issues and DebatesDocument23 pagesThe Sarasvati River Issues and DebatesRitu SinghNo ratings yet

- Drainage System and WatershedDocument13 pagesDrainage System and Watershedamanamu436No ratings yet

- Rigvedic Sarasvati Myth and RealityDocument10 pagesRigvedic Sarasvati Myth and RealityTariq Maqsood KhanNo ratings yet

- Geographical Milieu of Ancient KashiDocument14 pagesGeographical Milieu of Ancient Kashismk11No ratings yet

- The Lost Saraswati River of Northwestern Indian PlaneDocument12 pagesThe Lost Saraswati River of Northwestern Indian PlaneChill Films100% (1)

- A Review of Studies On Saraswati (Central Ground Water Board, Dec., 2014)Document70 pagesA Review of Studies On Saraswati (Central Ground Water Board, Dec., 2014)Srini Kalyanaraman100% (2)

- Quest For Himalayan Gold: Need For Reappraisal of Subansiri River ProspectDocument8 pagesQuest For Himalayan Gold: Need For Reappraisal of Subansiri River ProspectDr-Bashab Nandan MahantaNo ratings yet

- Geological Evolution of Varanasi: January 2016Document26 pagesGeological Evolution of Varanasi: January 2016RAAZ GUPTANo ratings yet

- Rakhigarhi Capital City of Sarasvati Sin PDFDocument3 pagesRakhigarhi Capital City of Sarasvati Sin PDFjaargavi dendaNo ratings yet

- Indian Tradition and CultureDocument15 pagesIndian Tradition and CultureDeepesh RajpootNo ratings yet

- Geo11 3 India Drainage SystemDocument11 pagesGeo11 3 India Drainage Systemsuperman_universeNo ratings yet

- The Lost Saraswati River of Northwestern Indian PLDocument12 pagesThe Lost Saraswati River of Northwestern Indian PLJahnavi GopaluniNo ratings yet

- River Saraswati, An Integrated Study Based On Remote Sending and GIS Techniques, ISRO (JR Sharma Et Al, 2014)Document11 pagesRiver Saraswati, An Integrated Study Based On Remote Sending and GIS Techniques, ISRO (JR Sharma Et Al, 2014)Srini KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Survey of Charsadda Distr PDFDocument81 pagesArchaeological Survey of Charsadda Distr PDFAnonymous 4CZGb4RxNo ratings yet

- Kashmir-A Forgotten Paradise!Document113 pagesKashmir-A Forgotten Paradise!muqbil lateefNo ratings yet

- Palaeo-Channel Bisecting Puri Town, Odisha:Vestige of The Lost River Saradha'?Document11 pagesPalaeo-Channel Bisecting Puri Town, Odisha:Vestige of The Lost River Saradha'?janasubhamoy_8374402No ratings yet

- The Mystery of The Saraswati - by Wasudha Korke and DR Uday DokrasDocument85 pagesThe Mystery of The Saraswati - by Wasudha Korke and DR Uday DokrasudayNo ratings yet

- Rainage Ystem: Geography - Part IDocument11 pagesRainage Ystem: Geography - Part Ijagriti kumariNo ratings yet

- Rainage Ystem: Geography - Part IDocument16 pagesRainage Ystem: Geography - Part IShivani ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- SaradhaDocument11 pagesSaradhaPratyush NahakNo ratings yet

- Rainage Ystem: Geography - Part IDocument11 pagesRainage Ystem: Geography - Part IHari KishanNo ratings yet

- Samina 4104 Lec 2Document12 pagesSamina 4104 Lec 2Sakib MhmudNo ratings yet

- 46 John Mal VilleDocument8 pages46 John Mal VilleSanatan SinhNo ratings yet

- To Intercept Rain Water in KachchhDocument32 pagesTo Intercept Rain Water in KachchhDeepak RamchandaniNo ratings yet

- Saraswati River Flowed Till 1402 CE in Haryana CERSR Study Why DidDocument33 pagesSaraswati River Flowed Till 1402 CE in Haryana CERSR Study Why Didsagar anandNo ratings yet

- Rainage Ystem: Geography - Part IDocument11 pagesRainage Ystem: Geography - Part IChithra ThambyNo ratings yet

- Study Material Drainage SystemDocument10 pagesStudy Material Drainage Systemठलुआ क्लबNo ratings yet

- Some Evaporite Deposits of India: Proc Indian Natn Sci Acad 78 No. 3 September 2012 Pp. 401-406 Printed in IndiaDocument6 pagesSome Evaporite Deposits of India: Proc Indian Natn Sci Acad 78 No. 3 September 2012 Pp. 401-406 Printed in Indiavaishu2488No ratings yet

- A Outline of History of KashmirDocument240 pagesA Outline of History of KashmirVineet Kaul0% (1)

- Drainage System IghjjjDocument8 pagesDrainage System IghjjjAkhilesh YadavNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - (Philoid-IN)Document11 pagesChapter 3 - (Philoid-IN)Siddharth KumarNo ratings yet

- HARYANA - Cradle of World's Most Ancient CivilisationDocument6 pagesHARYANA - Cradle of World's Most Ancient CivilisationquigiNo ratings yet

- Late Quaternary Climatic Vicissitudes As Deciphered From Study of Lacustrine Sediments of Sambhar Lake, RajasthanDocument12 pagesLate Quaternary Climatic Vicissitudes As Deciphered From Study of Lacustrine Sediments of Sambhar Lake, RajasthanPralay MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Map India 2005 Geomatics 2005Document11 pagesMap India 2005 Geomatics 2005souleymane2013No ratings yet

- An Engraved Landscape: Rock carvings in the Wadi al-Ajal, Libya: 2 Volume SetFrom EverandAn Engraved Landscape: Rock carvings in the Wadi al-Ajal, Libya: 2 Volume SetNo ratings yet

- Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University Kakinada: College Name: Sri Sivani College of Engg, Chilakalapalem, Srikakulam:W6Document43 pagesJawaharlal Nehru Technological University Kakinada: College Name: Sri Sivani College of Engg, Chilakalapalem, Srikakulam:W6Devendra PotrakhandaNo ratings yet

- GeographyDocument189 pagesGeographyNijam Nagoor100% (1)

- Training Manual-Piping: Piping Study Underground PipingDocument30 pagesTraining Manual-Piping: Piping Study Underground Pipingrams789100% (2)

- 1421 PQ Contract 2 WWTP Publication 200508 VVJDocument2 pages1421 PQ Contract 2 WWTP Publication 200508 VVJLuminita NeteduNo ratings yet

- Brochure BoosterDocument13 pagesBrochure BoosterBanupriya BalasubramanianNo ratings yet

- Unit Lecture - Freshwater Systems and Resources - DLDocument82 pagesUnit Lecture - Freshwater Systems and Resources - DLana lamiquizNo ratings yet

- Cee Bsce 1st Term 1st Sem Bce 313Document141 pagesCee Bsce 1st Term 1st Sem Bce 313SHALOM EMMANUEL OHAONo ratings yet

- Read The Text Carefully. Causes of FloodsDocument4 pagesRead The Text Carefully. Causes of FloodsAryNo ratings yet

- LaporanThermograf Blowdown Valve #1Document13 pagesLaporanThermograf Blowdown Valve #1Engineering PLTU BanjarsariNo ratings yet

- Complete Report PDFDocument93 pagesComplete Report PDFfurqan salabatNo ratings yet

- Drip Irrigation Guide For Potatoes: EM 8912 - Revised January 2013Document8 pagesDrip Irrigation Guide For Potatoes: EM 8912 - Revised January 2013palannny chakadyaNo ratings yet

- Water Systems: Water Conditioning For Process and Boiler UseDocument23 pagesWater Systems: Water Conditioning For Process and Boiler UseArun MuraliNo ratings yet

- Wrd13 2009 ReaffirmationDocument2 pagesWrd13 2009 Reaffirmationjamjam75No ratings yet

- CyclonesDocument8 pagesCyclonesbaljitNo ratings yet

- Design Calculation WWTP 1Document2 pagesDesign Calculation WWTP 1ekamitra-nusantaraNo ratings yet

- Earthen DamDocument11 pagesEarthen Dam20CE015 Swanand DeoleNo ratings yet

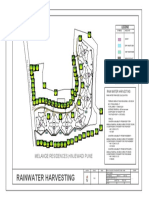

- Melange Residences, Hinjewadi Pune: Rainwater HarvestingDocument1 pageMelange Residences, Hinjewadi Pune: Rainwater HarvestingYukti AnandNo ratings yet

- Chap 4 - Wastewater - Effluent Treatment Plant Water Quality Testing - FactsheetDocument2 pagesChap 4 - Wastewater - Effluent Treatment Plant Water Quality Testing - FactsheetpharmacistnafiNo ratings yet

- Schematic Diagram of ETP in TPSDocument3 pagesSchematic Diagram of ETP in TPSKapil_1983100% (1)

- 07 RiverDocument66 pages07 RiverMehtab Ahmed KhanNo ratings yet

- Kasur Tanneries Waste Mnagment Agency (KTWMA)Document45 pagesKasur Tanneries Waste Mnagment Agency (KTWMA)Engr Muhammad Imran Nawaz0% (2)

- Alexandria - Urban History and Urban Future of Water ConflictsDocument334 pagesAlexandria - Urban History and Urban Future of Water ConflictsayamhannaNo ratings yet

- SplashDown Tri Fold Brochure Rev 1 7 2022 1Document2 pagesSplashDown Tri Fold Brochure Rev 1 7 2022 1JuanNo ratings yet

- Wetlands 'Nature's Kidneys'Document34 pagesWetlands 'Nature's Kidneys'AyushNo ratings yet

- Rain Water Storage & Pipe Gutter CalculationDocument17 pagesRain Water Storage & Pipe Gutter Calculationhera4u2No ratings yet

- DEDR PanchkhalVOL1Final 5 Sep 2019 REV 13 Sep PDFDocument95 pagesDEDR PanchkhalVOL1Final 5 Sep 2019 REV 13 Sep PDFAmul ShresthaNo ratings yet