Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Idealism As Compromise in Modern Architecture: An Inter-Nordic Dilemma or A Tour-de-Force?

Idealism As Compromise in Modern Architecture: An Inter-Nordic Dilemma or A Tour-de-Force?

Uploaded by

didiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Idealism As Compromise in Modern Architecture: An Inter-Nordic Dilemma or A Tour-de-Force?

Idealism As Compromise in Modern Architecture: An Inter-Nordic Dilemma or A Tour-de-Force?

Uploaded by

didiCopyright:

Available Formats

Idealism as Compromise

in Modern Architecture

An Inter-Nordic Dilemma or a Tour-de-Force?

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten

T

he modern Nordic architect has often been regarded among the Nordic nations, at different times during the

as typically an idealist, and this was certainly true 20th century, as regards architectonic norms in relation to

in the decades around 1960. However, understan- political status. Such national tendencies may concern

dings of forms of idealism obviously differ, both in a historical, abstraction in form, versus a concern for the culturally

diachronic perspective and in a time-bound, synchronic evolved artefact-in-the making, or, as it turns out at the

view, a fact that makes a comprehensive analysis in a brief point in time discussed here, a common humanism expressed

format hard to achieve. Around 1960 it is particularly striking in universal cultural values rather than in sociopolitical,

that universalizing and idealistic interpretations of the democratic, imperatives.

concepts of “the individual” and of “humanism” take on And yet period tendencies have been seen frequently to

very different meanings in two, opposing, attitudes among touch and even conflate among modern architects of the

architects. different Nordic countries, overriding local/national eco-

In the following discussion of a division of priorities as nomic agenda and sociopolitical norms. Such tendencies

to current agenda among progressive Nordic architects on anticipate present globalization. Thus a preoccupation

the threshold between the 1950’s and the 1960’s, it will have with the notions of “idealism” and “universal values” is evi-

been presupposed that there is no common Nordic app- dent among internationally minded, Nordic architects in

roach in architecture, as is often assumed, but instead a the years around 1960, at the same time as the architect’s

particular, inter-Nordic mode of approach. This presuppo- responsibility towards the community of users in the tradi-

sition is made against the background of my previous re- tion of CIAM continues to be debated and questioned.

search which was most recently formulated in a paper pre- Here the question that is raised is whether “idealism” as

sented at the Utzon Symposium in Aalborg in 2003.1 Equally discussed by those same Nordic architects presupposes a

and on the same research basis, I will continue to maintain concern with responsibility. And further, whether respon-

here that a displacement of priorities may in fact be observed sibility spells compromise.

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten: Idealism as Compromise in Modern Architecture 19

Hence the specific question that has motivated the fol- Grung, Håkon Mjelva, Christian Norberg-Schulz and Odd

lowing review is whether – or under what conditions – the Østbye – who were young architects of an avantgarde pro-

Nordic architect allows himself/herself readily to compro- moting analysis through abstraction. Even an extract from

mise his/her autonomous architectonic formalism, and then, the concluding lines of what has the appearance of a mani-

too, if a humane and social orientation may be seen to differ festo expresses their hell-bent idealism:

from – or relate to – general period tendencies.

Modern is that architecture which realizes the possibilities of

A latent conflict in the normally pragmatic Nordic archi-

the era. The possibilities of an era have nothing to do with

tect, between architectonic idealism and sociopolitical com-

the conscious wishes of the public, but imply an unexpected

promise, may be spot-lighted in two citations from Finland

enrichment through realization. The conscious wishes of the

and Norway:

public will always adhere to detail without understanding

The professions specialize more and more. And the hyper- that architecture is not motif but environment, totality and

specialist becomes the superman of his line of business. Our interaction...

business is so close to the reality of life that we receive from

And they conclude:

the community that criticism and control which keep us away

from the lines of specialization... Architecture must there- Modern is that architecture which provides possibilities of

fore [...] seek out the universal phenomena in life and the growth for human values. Human values have nothing to do

universal reactions in the human individuals that make up with the idiosyncracies of the individual, but can only be

the communities. The architect is the tool of the commu- attained through an active attitude towards the environ-

nity, but he must not merely be its slave. Each person, the ment...

carpenter as well as the statesman, knows that in all profes- Group 5, in A5, Meningsblad for unge arkitekter, 1956 3

sions there are things where compromise is equal to treason. What Group 5 also had in common with Aulis Blomstedt

The striving for a synthesis which is as objective as possible (1906–79) was that they, led by Arne Korsmo (1900–68),

and an inclination for spineless compromise are each other’s were among the new Nordic bearers of the CIAM banner.

opposites. Individual representatives from the Nordic countries – ma-

Aulis Blomstedt, in Arkkitehti, 1962.2 jor first-generation functionalists such as Sven Markelius,

In the concluding statement of a brief exposition on the Uno Åhrén, Alvar Aalto, Lars Backer, Herman Munthe-Kaas,

subject of ”Measurements and proportions” in exhibition Frithjof Reppen – had attended various CIAM meetings as

design, Aulis Blomstedt confronts us with what appears to early as the end of the 1920s, as well as Vilhelm Lauritzen in

be a dilemma with wider, and inter-Nordic, implications. 1951; in 1952 there was even a preparatory meeting for CIAM

The artist architect – using measurements and proportions IX and its Habitat Charter at Sigtuna, Sweden. But what

as the painter uses his colours – is held up vis-à-vis the happened now was a different start, and this presentation

community of individuals. From their subjective stand- of their work and aims by Group 5 in fact both reflected and

points they must generalize, since it is their task to control anticipated the shift of initiative – to a young generation –

and criticize the work he does for them. They are each of which was to be advised by Le Corbusier in a ”Message” to

them members of a larger community of people and this the CIAM X congress in August that same year.4 Parallel to

fact is at the same time the very reason for him to insist on the Group 5 statement, a couple of articles in the same first

offering them a universal synthesis. In pursuing the univer- issue of A5 in 1956, thematizing Modern Norwegian Archi-

sal, the architect demonstrates his idealism, and he makes it tecture, focused on the contributions of the Norwegian

clear that he has no intention of compromising that idea- 1930s pioneering generation; tribute was paid to their buil-

lism. dings, and the demise of their political efforts was debated,

Blomstedt’s pronouncement may remind us of another respectively, while Arne Korsmo turned directly to the

one made some six years earlier in Norway on the opposite contemporary, young ”architect-minds” in an account of

side of the Nordic region, by Group 5 – Sverre Fehn, Geir his own work.5 And central to Korsmo’s approach was the

20 Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2004: 4

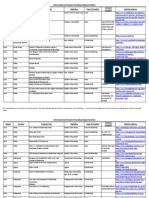

“The individual” and “El-pe” lamps by Arne Jacobsen. Illustrations on opposite pages of A5, Meningsblad for unge arkitekter, 1959: 4-5-6.

function of the artistic idea as an illuminator of the greater of the Finnish CIAM-group, started in 1953. And Blomstedt

structure of things, in almost diametrical opposition to on his part predicated ”an absolute architecture” which was

the dominant sociopolitical and urbanistic prerogative programmatically anti-intuitive and instead focused on

of CIAM. pure, architectonic solutions to spatial problems.6 It consti-

At this time, what might be described as local sub-frac- tutes an even more abstract approach than Korsmo’s.

tions of CIAM had already been established in Norway and Meanwhile, against the background of the two statements

Finland – only. The initiative had been taken in Norway it is important to recall that at this point the democratic

through the early, post-war formation of a group of young welfare state had been in full flower for at least one generation

progressive architects with ideological links to sympathizers of architects and planners in the Nordic countries. Since

in Denmark. Subsequently, in 1949, they declared them- the 1930s social politics had increasingly infiltrated the

selves as the Norwegian PAGON-group (active until 1956); processes of public building – primarily, of course, within

Danish Jørn Utzon was a guest member. In Finland it was housing and urban planning; from the post-war years until

Aulis Blomstedt, ably seconded among others by the young the early 1970s this directed process of modernization was

Reima Pietilä (1923–87), who became the ideological leader instigated by a Social Democracy that was either in govern-

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten: Idealism as Compromise in Modern Architecture 21

mental position or frequently allied to it, in all four countries; tion and independence.9 It appears, too, that the autonomy

here meaning Sweden and Denmark as separate from Nor- of the Finnish artist architect’s vision may coincide with the

way and Finland, where the effects of WWII and Reconst- aesthetic idealism of the state cultural apparatus, disregar-

ruction were far more thoroughgoing, delaying somewhat ding common – Nordic – cultural norms.10

the construction of a welfare state into the 1950s. But the The central question here, then, concerns the way in

basis for a general democratic effort, in spite of party diffe- which such artistic idealism differs – disregarding its univer-

rences, was without doubt an interrelated set of Nordic salizing rhetoric – from a democratic-humanistic form

cultural and sociopolitical norms going back on sufficiently for idealism, explicitly interested in the conditions for

similar geographical and economic conditions – apart from living of the human community and expressed in uni-

intermittently shared histories. This meant now that in an versal cultural values. One may naturally ask whether ide-

overall picture the political left had – in company with the alism – by definition directed towards an ideal and shun-

centre and the liberal right – generally accepted economic ning present reality – could possibly admit of compro-

growth as the engine of society. And the wheel of the engine mise. That means to say, whether the democratic ”pro-

was the open Nordic tradition of negotiations, sufficiently ject” of the welfare state as regards ideals in architecture

often in a spirit of mutual agreement and democratic loyalty, and planning can be anything but a contradiction in terms?

despite evident divergences between the nations as regards Would a utopistic “middle way” – such as the one bet-

normative ways of perception.7 This produced the Nordic ween economic individualism and collectivism that the

humanist-utopistic model for social planning, and is, I sug- Swedish welfare state and many collaborating architects

gest, an expression of what I shall describe as ”democratic attempted to take in the 1930s to 60s – be a tour-de-force,

idealism” in this paper. a dilemma or even a joke?11

What is relevant here, however, is that the actual concept To illustrate the problem, a democratic idealism may be

of democracy is in fact absent in the two statements – from traced in the call for an all-embracing approach in architec-

differing sources – cited above. A democratic procedure as ture that had been made by the ageing Walter Gropius in a

between client group and architect, or between the architect talk at the San Paolo Museum of Modern Art in 1954; it was

and other professional consultants representing ”the com- reprinted in a Danish translation in the January number of

munity” and involved in the design and building process, is A5 in 1955,12 meaning to say here, that it was considered

not even implied. As regards the community of users, accor- important by the young Danish architects who edited the

ding to the 1956 statement they are to be unexpectedly magazine. The talk has a critical bearing, bringing up two

”enriched”, but they are apparently spurned by the ”active” major, and possibly contradictory, aspects of the dream of a

architects who will conceptualize and form their environ- humanistic, universal approach.

ment for them. While in 1962 no compromise is to be The first aspect is Gropius’ evident concern regarding

expected. the influence of the visual environment on users and the

The statements exhibit an idealism which in reality fosters role of architects and planners in the effort to make the lives

aesthetic autonomy in the architect’s work and is readily of men and women happier and more productive. Taking

characterized by architectonic formalism. One thesis I have issue with the growing tendency towards specialization,

put forward, is that in architectonic terms collective, na- Gropius proposes ”a human standard that suits all of so-

tion-defining agenda in Norway and Finland – resulting ciety”, but which may at the same time also satisfy the

from their having achieved national independence in 1905 wishes of the individual, through applied modifications.

and 1917, respectively – may explain a directed cultivation He claims that it is not enough just to defend democracy;

of international and rationalist, formal tendencies in their instead he states that ”we must win the struggle of ideas by

modern architecture.8 In both countries the agenda is pushed making democracy into a positive strength”. For the young

by a conspicuous elite. In Finland the additional fact of generation this should mean finding ”a common expression,

the shared borderline with Soviet Russia, has also favoured rather than a pretentious individualism”. “Individualism”

a differing code of demeanour – a political stance of cau- is here seen as propagating an autonomous approach.

22 Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2004: 4

“Microcosm” and “Macrocosm”. Double-page illustrations in A5, Meningsblad for unge arkitekter, 1959: 4-5-6.

Gropius’ underlying assumption is that the fulfilment of his article to the young architects mentioned above. In both

the need for beauty is at least as important for a civilized these texts by – different – young, Nordic, progressive archi-

life, as is the satisfaction of material needs for our physical tects the point of departure is the logical structures of nature

well-being. Asking himself whether he who creates a rose or as seen in the plant world, with reference in the 1947 state-

a tulip is an artist or a technician, Gropius asserts that in ment also to the mineral world. Alvar Aalto, on his part,

nature usefulness and beauty are integral as well as mutu- had originally used the concept of mutually variant combi-

ally interdependent; the organic process of creation in na- nations of nature as a model already in 1941 when he deve-

ture is the model for all human creation, whether the result loped his ideas on an “archi-technic” art of building. This

is the spiritual endeavour of the inventor, or the intuition of meant “a system” which was capable of absorbing “the

the artist. And this is the second aspect. whole scale of dissimilarities that we find among people

In fact Gropius here mirrors the humanistic standpoint and groups of people”.14 Korsmo echoes both Alvar Aalto

taken by Jørn Utzon and Tobias Faber in a joint manifesto and, following Aalto, Utzon when he maintains that

in the Danish journal Arkitekten already in 1947,13 as well as

the position of Arne Korsmo – who of course collaborated …all nature has a clear and logical structure, but at the same

with Utzon in some competition projects in 1947–49 – in time every living thing must adapt itself to changing living

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten: Idealism as Compromise in Modern Architecture 23

conditions and seek out its form and nuances of growth in to fulfill another task: work for the rights of the individual

time and space. against collectivism and standardization.

But Korsmo’s conclusion regarding the inevitable univer- It is obvious that the more clear-cut, opposing issues of the

salization that this insight brings differs from Gropius’ 1960s are imminent, and that the lurking, autonomous for-

critical stand, and instead foreshadows Aulis Blomstedt’s malism of the new architects is correspondingly present in

position of abstraction: the arts. The same division and the same formalism is especi-

ally visible in Denmark, evident in a troubled relationship

In architecture as in the world of objects we seek for the uni-

between craft design and fine art, as well as in the auto-

versal. Geographical position and country give rise to diffe-

nomy of work such as Arne Jacobsen’s, or that of Halldor

rences according to the law of adaption, therefore we must

Gunnlögsson and other Danish contemporaries. But what

work first with universal standards. In all parts of the world

is about to counter this phenomenon – certainly in Swedish

men are working to-day on such basic principles.15

large-scale housing programmes (”Miljonprogrammet”

One asks oneself if Korsmo’s conclusion in fact reveals a 1965–74) and in the innovative, so-called ”low-dense” habi-

wishful agenda, or whether he believed, simply, that it is tations as developed by the architectural firm Vandkunsten

only by examining what is universal, that we may underst- in Denmark – is the emergence in concrete terms of a struc-

and the variation. turalism that is at one and the same time formalist in cha-

What, then, is the inevitable next stage in the Norwegian racter and socially oriented. Vandkunsten’s ambition was to

discourse as presented in A5? In a special issue, Modern Nor- see architecture as a framework for, and around, life.17

wegian Art, in 1959, we find a similar division along parallel What we of course know as a historical fact, is that demo-

lines.16 Writing on the task of the progressive “creators of cratic-humanistic idealism is under continuous ideological

environment” to respond to Norway’s dominant “beautiful threat, but that the threat changes in appearance, as it is tied to

and changing nature” and her cultural treasures, and work a time-bound, societal and economic situation. In the Utzon

towards the creation of a modern culture and society, the Symposium paper of 2003 mentioned above, I had already

Norwegian editor Olaf Liisberg calls for a collaboration asked myself the question where the client with the expec-

with artists. And since “visual culture depends on manifold tations and norms of the local/national community could

factors” and groups of people, Liisberg declares that these enter the architect’s – in effect – autonomous picture. The

“require a common direction and a dynamic universal under- contradiction inherent in the two forms of idealism, demo-

standing”, and that Norway “accepts a visual evolution”. He cratic and artistic, may be recognized in the “double move-

follows his declaration up by reproducing a series of abstract ment” that has been identified by Claes Caldenby in regard

art works by several artists, mixing them with photographs to Swedish late-modern architecture.18 It concerns two sides

from nature. However, the special issue ends with what of modernization. Applying the concept here, one side

appears to be a counter statement as regards collaboration indicates modernity’s collective faith in progress, sanctioning

with artists. It is an article by an academic on “Co-opera- the architect’s specialization within a collective process, and

tion and [the] individual” where a socially oriented huma- presupposing cultural access on the part of the community’s

nism is disclaimed and the individual rights of the artist are average potential client; the other is aesthetic modernity’s

reestablished. The reason is that Norway already over the assumption of artistic autonomy and self-realization.

last 20–30 years has seen the development of a monumental An early warning of this contradiction in real terms may

art that has aimed at integrating “the people”, in a new icono- be found in a pamphlet, Architecture and Democracy, written

graphy where the heroes have been “the intellectual, the by Uno Åhrén and published in 1942 by the Cooperative

fisherman, the farmer and the worker”. But the new approach Society in Stockholm. He saw himself forced to conclude

ought to be a different one: that the ideals of democracy cannot be implemented in an

economic system that opposes them in important respects.

Today the situation has changed. The social moment is losing

This circumstance, he deemed, was as much the architects’

its appeal. Humanism, which has been at its origin once, has

24 Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2004: 4

Klemensker Central School, Denmark. Wall mosaic by the painter Preben Hornung, executed by the architects Gunnar Jensen and Finn Monies. Illustration in A5,

Meningsblad for unge arkitekter, 1961:1.

dilemma as it was that of the present social organization. constructive forces” must be put to increased work to secure

We may recall that we are here a good decade into the human rights and ideals – the same feat of critical will that

Swedish, post-1930, social housing programme which had Walter Gropius was to call for, as in 1954 and particularly in

meant a period of upturned architectural norms. What Åhrén many of his late statements.19 Åhrén and Gropius both

regrets now to find is a romantic escape by the architects continually raised the ethical problem of the architect’s

into old artistic ways and into “other ideals” that may bring responsibility vis-à-vis the community of users.

easier recognition. But he himself is intent on resisting a In the context of the present discussion of diverse Nordic

”let-go” approach as incompatible with a humanistic demo- reception of international impulses, it should be noted as

cratic system; he is also refusing to accept a more efficient – indicatory that the journal of the Danish architectural asso-

non-democratic – political and economic coordination as ciation in 1962 published the main part of another talk by

an option at the expense of a humanistic ideal of respon- Gropius, “Arkitekten i fællesskabets spejl” (Der Architekt

sible liberty. Instead democracy’s ”unlimited reserves of im Spiegel der Gesellschaft) from 1961, which explicitly urged

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten: Idealism as Compromise in Modern Architecture 25

However, what the Swede Åhrén could barely foresee

was that the type analysis and urban planning that he set

store by, would turn into a bureaucratic wave of inhuman

technologization and self-serving building research which

was to sweep in over Sweden in the name of a state-run

system, and which would break only with economic reces-

sion.21 While, again, in divergent Finland Juhani Pallasmaa

was to protest continually over time against planning and

technology as international phenomena pursued in their own

right.22

Åhrén’s critical position may be briefly contrasted for

emphasis with the openly market-driven, pluralistic scenario

of the permissive 1980’s.23 Sweden, by tradition fearless of

popular and cooperative attitudes now combined with an

idiosyncratic, frihetlig or ”libertarian” aesthetic approach in

her modern architecture, was to take a direct hit by post-

modernism;24 meanwhile sociopolitical factors had contri-

buted increasingly to severe restrictions on her architects’

authority in practice. Norway, too, was hard hit in a com-

bined regional and postmodern urge towards detailing, but

here the use of flashy materials was due to technocratic

tendencies that had been visible already in the 1950s and

were amplified as a result of the industrial exploration of

newly discovered oil resources. Conversely, postmodern

impulses have been only episodic in Denmark, stable in her

hang to a reserved universalism and the anonymous, finis-

hed detailing of the culturally evolved artefact-in-the making,

while Finland appears to have adapted again on rational and

heroic grounds to an alien, but international, phenomenon.

Ultimately, architectonic response may be seen to have

been steered in each country by local/national variants of a

Nordic communality of norms.

Themes in architecture introduced by the Danish architectural firm Vand- Therefore one still asks if artistic idealism could possibly

kunsten: Town-making in landscape, social space, the common and the

communal, unity of form and material translated into new types and aesthetic be consonant with and even collaborate with modern society’s

concepts. Page 197 in Arkitektur (Dk), 1985: 5–6. pragmatic idealism? Reformulated from a social viewpoint,

might a Nordic, humanistic-and-normative approach be

decoded as applied idealism? In spite of different approaches,

is the assumption of an undercurrent of communal respon-

the collaboration between the creative, individual architect sibility common to the Nordic countries correct? When –

“spirit” and a collective of users and colleagues. Their com- and only when – an applied idealism seems to hold true,

mon, spontaneous intuition would create an interchange not only in principle but is temporarily achieved in fact, we

between “our pragmatic requirements and our spiritual may talk of a tour-de-force on Nordic terms. Yet in a con-

ideals”, and a continued contact with the wider goals of the tinuously troubled world – of which we are part – the

larger group.20 dilemma remains.

26 Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2004: 4

7. For historical data referred to in this section, cf. H. Gustafs-

son, Nordens historia. En europeisk region under 1200 år, Lund:

Studentlitteratur 1997, as well as more specifically, S. Hade-

nius, Svensk politik under 1900-talet. Konflikt och samförstånd,

Stockholm: Hjalmarson och Högberg 2000 (5th ed.), E. Bull,

Norgeshistorien etter 1945, Oslo: Cappelen 1982/1990 and O.

Jussila-S. Hentilä-J. Nevakivi, Finlands politiska historia, 1809–

1998, Esbo: Schildts Förlag 1998.

8. G. Bloxham Zettersten 2000, pp. 502–13.

9. For an account of Finland’s struggle to maintain her national

independence, see M. Jakobsson, Finlands väg 1899–1999,

Stockholm: Atlantis 1999; this book in its turn had originated

in an article, ”Finland: A nation that dwells alone”, The Wash-

ington Quarterly, 1996:4.

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten, fil. dr 10. This has recently been thoroughly documented by Petra Ceferin,

Institute of Art and Cultural Studies in Image as Product: The International Expositions of Finnish

Copenhagen University Architecture 1957–67, Licentiate thesis, Helsinki University of

gbz@email.dk Technology 2003.

11. The reference is to M.W. Childs, Sweden, the Middle Way, Yale

University Press 1936/1974.

12. W. Gropius, ”Arkitekten og vore synlige omgivelser”, A5,

Meningsblad for unge arkitekter, 1955: 5–6, 210–19. The cita-

Notes tions are my own translation from the Danish.

1. The latest research referred to is G. Bloxham Zettersten, “Is 13. T. Faber-J. Utzon, ”Tendenser i Nutidens Arkitektur”, Arki-

there a Nordic Janus-face? The relation between idealism and tekten (DK) 1947: 7–8–9, pp. 63–69.

pragmatism in Nordic architecture”, in: M. Mullins-A. Carter 14. A. Aalto, ”Europas återuppbyggnad aktualiserar det centralaste

(eds.), Proceedings. Utzon Symposium: Nature Vision and Place, problemet för vår tids byggnadskonst”, Arkitekten (FL) 1941,

University of Aalborg, August 28th–30th 2003, pp. 37–47. This pp. 75–80, reprinted in Byggekunst 1944, pp. 4–13.

was a desk-top publication, and the article will be forth- 15. The two citations are from the English version of Korsmo’s

coming in print in the spring of 2005. It takes off from, as well text in A5; see note 5.

as elaborates on, conclusions reached in my doctoral disserta- 16. The references are to O. Liisberg, ”Moderne norsk kultur”,

tion, ibid., Nordiskt perspektiv på arkitektur. Kritisk regiona- pp. 11–16, and to P. Anker, ”Samarbeide og individ”, pp. 111–12,

lisering i nordiska stadshus 1900–1955, Stockholm: Arkitektur in A5, Meningsblad for unge arkitekter, 1959: 4–5–6; the cita-

Förlag 2000. tions are from the English version.

2. A. Blomstedt, ”Mått och proportion”, Arkkitehti-Arkitekten 17. Cf. a special issue on Vandkunsten, Arkitektur (DK) 5–6, 1985,

1962: 9, p. 176. My own translation from the Swedish version. and esp. pp. 196–7, 216–17 and 238–40.

3. ”Gruppe 5”, A5, Meningsblad for unge arkitekter, 1956: 1–2, pp. 18. C. Caldenby (ed.), Att bygga ett land. 1900-talets svenska arki-

67–80. My own translation from the Norwegian original. tektur, Stockholm: Byggforskningsrådet 1998, p. 160ff.

The magazine (1942–62) was produced by students at Nordic 19. U. Åhrén, Arkitektur och demokrati, Stockholm: Koopera-

architectural schools, but had its home base in Copenhagen. tiva Förbundets Bokförlag 1942, in particular pp. 22–29 and

4. E. Mumford, The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928–1960, 37–42. Nils-Ole Lund has set Åhrén’s protest in a Danish

The MIT Press 2002, p. 248 perspective in ”Enquete om demokratisk arkitektur: Sam-

5. The articles referred to are: E. Kjeldset-N.-O. Lund, ”Epoken fundsengagementet”, Arkitekten (DK), okt. 1993, pp. 526–

som ble borte/The epoch that disappeared”, pp. 5–19; U. 29.

Bergsgaard, ”Har 30-årsgenerasjonen sviktet?/Did the gene- 20. W. Gropius, “Arkitekten i fællesskabets spejl”, Arkitekten

ration of the 30’s fail”, pp. 21–23; A. Korsmo, ”Til unge arki- (DK) 1962: 26, pp. 509–513. The article was later published in

tektsinn/To young architects”, pp. 40–54; in: A5, Meningsblad its full length in an anthology, ibid., Apollo in der Demokratie,

for unge arkitekter, 1956: 1–2. Neue Bauhausbücher, Mainz & Berlin 1967.

6. A. Blomstedt, ”Prospects in architecture”, Arkkitehti-Arkitekten 21. Cf. U. Sandström, Mellan politik och forskning 1960–1992,

1952: 9–10. For his trendsetting attitude to internationalism Stockholm: Byggforskningsrådet 1994, and N. Ahrbom, ”Fem-

and universalism, see also ”Perspektiv på arkitekturen”, Arkki- tio- och sextiotalen”, in: ibid., Arkitektur och samhälle, Stock-

tehti-Arkitekten 1956: 6–7, pp. 101–02. holm: Arkitektur Förlag 1983, pp. 135–54.

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten: Idealism as Compromise in Modern Architecture 27

22. An early attack on contemporary planning is J. Pallasmaa,

”The tenses of planning”, Arkkitehti-Arkitekten, 1967:5, Sum-

mary, pp. 6–7 (in the English translation).

23. Cf. a special issue on contemporary Nordic architecture, with

contributions from the four architectural journals, Bygge-

kunst-Arkitektur-Arkitekten-Arkkitehti; published in Den-

mark in Arkitekten 1986: 21–22, in analyses by K.O. Ellefsen, C.

Caldenby-O. Hultin, K. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, J. Pallasmaa.

24. A thorough analysis of a contemporary Swedish approach has

been undertaken by Claes Caldenby in several texts; cf. for

example C. Caldenby, ”In the footsteps of Gunnar Asplund”,

in M. Quantrill-B. Webb (ed.), The Culture of Silence, Texas A

& M University Press 1998, as well as in C. Caldenby (ed.)

op.cit., pp. 143–96.

28 Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2004: 4

You might also like

- Programs and Manifestoes On 20th-Century Architecture - Ulrich Conrads 1 PDFDocument97 pagesPrograms and Manifestoes On 20th-Century Architecture - Ulrich Conrads 1 PDFIvo Vaz Barbosa100% (10)

- Matti Kuusi, Keith Bosley, Michael Branch - Finnish Folk Poetry. Epic - An Anthology in Finnish and English - Finnish Literature Society (1977) PDFDocument642 pagesMatti Kuusi, Keith Bosley, Michael Branch - Finnish Folk Poetry. Epic - An Anthology in Finnish and English - Finnish Literature Society (1977) PDFAlea Entropy100% (1)

- A Short History of FinlandDocument222 pagesA Short History of FinlandİlkerNo ratings yet

- 2000 2013 Çıkmış Yds Lys-5 TENSEDocument6 pages2000 2013 Çıkmış Yds Lys-5 TENSEAhmet ÖlçerNo ratings yet

- Irina Davidovici - Dilemma AuthenticityDocument7 pagesIrina Davidovici - Dilemma AuthenticityCosmin PavelNo ratings yet

- Expressionist Architecture-Deutsche Werkbund PDFDocument9 pagesExpressionist Architecture-Deutsche Werkbund PDFenistenebimNo ratings yet

- Constructive RegionalismDocument5 pagesConstructive RegionalismHajar SuwantoroNo ratings yet

- Summerson PDFDocument11 pagesSummerson PDFJulianMaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Dominance in Finland's Grocery Retail MarketDocument5 pagesDominance in Finland's Grocery Retail MarketLexisNexis Current AwarenessNo ratings yet

- Cultural Sustainability - Frampton PDFDocument3 pagesCultural Sustainability - Frampton PDFYeshicaNo ratings yet

- A Return To The Figure of The Free Nordic PeasantDocument12 pagesA Return To The Figure of The Free Nordic Peasantcaiofelipe100% (1)

- February 22 - Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity A Critique 2-18Document19 pagesFebruary 22 - Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity A Critique 2-18Ayşe Nur TürkerNo ratings yet

- Anna Klingmann, Philipp Oswalt, FormlessnessDocument18 pagesAnna Klingmann, Philipp Oswalt, FormlessnessMelanie PoetaNo ratings yet

- Lefaivre - Everything Is ArchitectureDocument5 pagesLefaivre - Everything Is ArchitectureBatakoja MeriNo ratings yet

- BANHAM Reyner, StocktakingDocument8 pagesBANHAM Reyner, StocktakingRado RazafindralamboNo ratings yet

- Istvan Meszaros Lukacs S Concept of Dialectic The Merlin Press 1972 PDFDocument201 pagesIstvan Meszaros Lukacs S Concept of Dialectic The Merlin Press 1972 PDFLisandro Martinez100% (3)

- Art 00002Document24 pagesArt 00002Marcelo Rafael de CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Regionalism Introduction LMDocument12 pagesRegionalism Introduction LMarooj anjumNo ratings yet

- Archplus Ausgabe 129 130 Seite 115Document9 pagesArchplus Ausgabe 129 130 Seite 115Sapi33No ratings yet

- 2018 049 Elliott Enonce Elliott EnonceDocument85 pages2018 049 Elliott Enonce Elliott EnonceDenisa BalajNo ratings yet

- Oscar Niemeyer of Glass and Concrete 201 PDFDocument18 pagesOscar Niemeyer of Glass and Concrete 201 PDFMarcellin Gaby100% (1)

- Chapter 30. Since I945: A History of Architectural Theory From Vitruvius To The PresentDocument12 pagesChapter 30. Since I945: A History of Architectural Theory From Vitruvius To The PresentalexNo ratings yet

- Pattern Language - Design Method - Aleksander T. ŚwiątekDocument6 pagesPattern Language - Design Method - Aleksander T. ŚwiątekAlexSaszaNo ratings yet

- O Perspectiva Istoriografica - Introduction Renaissance and Baroque ArchitectureDocument22 pagesO Perspectiva Istoriografica - Introduction Renaissance and Baroque ArchitectureRaul-Alexandru TodikaNo ratings yet

- Modern Monument in The Context of ModernityDocument6 pagesModern Monument in The Context of ModernityWinner Tanles TjhinNo ratings yet

- Hollein Architecture Is EverythingDocument6 pagesHollein Architecture Is Everythingcookie319No ratings yet

- Marx, Architecture and Modernity: The Journal of Architecture April 2006Document19 pagesMarx, Architecture and Modernity: The Journal of Architecture April 2006Aarti ChandrasekharNo ratings yet

- The Vernacular Between Theory and practice-C.Machat PDFDocument14 pagesThe Vernacular Between Theory and practice-C.Machat PDFAlin TRANCUNo ratings yet

- Notes of ElementsDocument16 pagesNotes of ElementsAshwini AnandNo ratings yet

- Aldo Van EyckDocument22 pagesAldo Van EyckCatarina Albuquerque E CastroNo ratings yet

- Hunch Project Journal From Ciam To Cyberspace Architecture and The Community 44-51-1Document8 pagesHunch Project Journal From Ciam To Cyberspace Architecture and The Community 44-51-1joanaNo ratings yet

- Modernity Vs PostmodernityDocument5 pagesModernity Vs PostmodernityTer AiaNo ratings yet

- New EmpiricismDocument12 pagesNew EmpiricismAm30No ratings yet

- Utzon ParadigmDocument10 pagesUtzon ParadigmIsti IsWavyNo ratings yet

- 2013 AMZ FinalDocument12 pages2013 AMZ Finalzahariade.mail9419No ratings yet

- Referat EsteticaDocument8 pagesReferat EsteticaAnonymous lPD3sdSSyXNo ratings yet

- Robert A. M. Stern "Gray Architecture As Post-Modernism, Or, Up and Down From Orthodoxy"Document6 pagesRobert A. M. Stern "Gray Architecture As Post-Modernism, Or, Up and Down From Orthodoxy"Eell eeraNo ratings yet

- 05 B Lootsma FROM PLURALISM TO POPULISM PDFDocument16 pages05 B Lootsma FROM PLURALISM TO POPULISM PDFsamilorNo ratings yet

- Critical RegionalismDocument8 pagesCritical RegionalismHarsh BhatiNo ratings yet

- Language of Minimalism in ArchitectureDocument23 pagesLanguage of Minimalism in Architecturej rp (drive livros)No ratings yet

- Architecture As Nation-Building The SeaDocument40 pagesArchitecture As Nation-Building The SeaDiana CaducencoNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster - The ABCs of Contemporary DesignDocument9 pagesHal Foster - The ABCs of Contemporary DesignGabino KimNo ratings yet

- Rem KoolhaasDocument11 pagesRem KoolhaasAnusha Ivaturi100% (1)

- A Brutalist Story Involving The House, The City and The EverydayDocument9 pagesA Brutalist Story Involving The House, The City and The EverydayevasanchezgnzlzNo ratings yet

- Research For Research - Bart LootsmaDocument4 pagesResearch For Research - Bart LootsmaliviaNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology, Architecture and The Writing of Architectural HistoryDocument27 pagesPhenomenology, Architecture and The Writing of Architectural HistoryGustav Oscco PachecoNo ratings yet

- Publications de L'institut National D'histoire de L'artDocument16 pagesPublications de L'institut National D'histoire de L'artFlávio RaffaelliNo ratings yet

- What Belongs To Architecture HeynenDocument19 pagesWhat Belongs To Architecture HeynenSima NabizadehNo ratings yet

- Structuralism ArchitectureDocument24 pagesStructuralism ArchitectureKorowod100% (7)

- PostmodernismDocument6 pagesPostmodernismsanamachasNo ratings yet

- DM RA Zaalblad ENG DEF 26-04-2021 LRDocument35 pagesDM RA Zaalblad ENG DEF 26-04-2021 LRAmbado TanNo ratings yet

- In Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationDocument41 pagesIn Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationMaria Camila GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Art History Supplement, Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2013Document73 pagesArt History Supplement, Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2013Leca RaduNo ratings yet

- Bauhaus, Art2, Greta GinotyteDocument11 pagesBauhaus, Art2, Greta GinotyteGreta GinoNo ratings yet

- 10.2478 - Aup 2020 0014Document6 pages10.2478 - Aup 2020 0014MaeNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument956 pagesUntitledDIEGO ESCALONA CASTAÑEDA100% (1)

- Expressionism in ModernDocument25 pagesExpressionism in ModernHomam BsoolNo ratings yet

- Functionalism (Architecture) : Jump To Navigation Jump To Search List of References Improve IntroducingDocument15 pagesFunctionalism (Architecture) : Jump To Navigation Jump To Search List of References Improve IntroducingSaya Amara BaybayNo ratings yet

- David Cunningham, Marx, Architecture and ModernityDocument23 pagesDavid Cunningham, Marx, Architecture and ModernityJohn LeanoNo ratings yet

- Spaces of the Poor: Perspectives of Cultural Sciences on Urban Slum Areas and Their InhabitantsFrom EverandSpaces of the Poor: Perspectives of Cultural Sciences on Urban Slum Areas and Their InhabitantsHans-Christian PetersenNo ratings yet

- Ambiguity in Contemporary Art and TheoryFrom EverandAmbiguity in Contemporary Art and TheoryFrauke BerndtNo ratings yet

- Topic: Intenational Marketing Planning For Instant Coffee C+ of Cong Coffee Company at FinlandDocument49 pagesTopic: Intenational Marketing Planning For Instant Coffee C+ of Cong Coffee Company at FinlandLê Đức Thành VinhNo ratings yet

- International Student Funding Opportunities - University of Michigan13 - v2Document11 pagesInternational Student Funding Opportunities - University of Michigan13 - v2riri_riim2000No ratings yet

- History of FinlandDocument39 pagesHistory of FinlandpathimselfNo ratings yet

- Hybrid Steering Approaches With Respect To European Higher EducationDocument19 pagesHybrid Steering Approaches With Respect To European Higher EducationLygia RoccoNo ratings yet

- State Funeral - WikipediaDocument33 pagesState Funeral - WikipediaRodrigoNo ratings yet

- pk1 Plus enDocument8 pagespk1 Plus enSiva Sankar MohapatraNo ratings yet

- BukakeDocument12 pagesBukakemobiNo ratings yet

- Finland: The FactsDocument10 pagesFinland: The FactsJerry StackhouseNo ratings yet

- HomeworkDocument2 pagesHomeworkKarlo AnogNo ratings yet

- Norway and The Northern Front: Wartime ProspectsDocument46 pagesNorway and The Northern Front: Wartime ProspectsAlaric SerraNo ratings yet

- Finland DocumentDocument96 pagesFinland DocumentgurmukhvNo ratings yet

- t2 G 4082 Ks2 Lapland Information Powerpoint English Ver 3Document16 pagest2 G 4082 Ks2 Lapland Information Powerpoint English Ver 3Isabela Rădeanu100% (1)

- MARINETEK Floating Brochure 2013Document20 pagesMARINETEK Floating Brochure 2013Radhika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Childhood FinlandDocument21 pagesChildhood FinlandNohora ConstanzaNo ratings yet

- Finland Business StructureDocument8 pagesFinland Business StructureRuhi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Yrjö Kallinen and The Finnish Civil War 1918Document7 pagesYrjö Kallinen and The Finnish Civil War 1918Juha Janne Olavi UskiNo ratings yet

- Finnish Cycling BarriersDocument12 pagesFinnish Cycling BarriersJ KaleNo ratings yet

- Opiskelijan Oleskelulupahakemus, OLE - OPI (En)Document8 pagesOpiskelijan Oleskelulupahakemus, OLE - OPI (En)Kseniia Laura BergNo ratings yet

- Strategic CultureDocument19 pagesStrategic Culturehandlaren123No ratings yet

- Jurnal Teknologi: T P D U L D: A RDocument8 pagesJurnal Teknologi: T P D U L D: A RMuhammad Iqbal NasutionNo ratings yet

- Bachelor Thesis Dipo DaramolaDocument101 pagesBachelor Thesis Dipo DaramolaAjibolaNo ratings yet

- Seurustelusuhde Liite enDocument7 pagesSeurustelusuhde Liite enBadreddine QNo ratings yet

- Messerschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe PDFDocument214 pagesMesserschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe PDFRoberto Carlos Subauste Pérez100% (1)

- Salonen Nord StreamDocument29 pagesSalonen Nord StreamstevekahnNo ratings yet

- Written AssignmentDocument2 pagesWritten AssignmentMario ShakarNo ratings yet

- How Does New Zealand's Education System Compare?Document37 pagesHow Does New Zealand's Education System Compare?KhemHuangNo ratings yet