Professional Documents

Culture Documents

An Evaluation of Space Planning Design of House Layout To The Traditional Houses in Shibam, Yemen

An Evaluation of Space Planning Design of House Layout To The Traditional Houses in Shibam, Yemen

Uploaded by

priyaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

An Evaluation of Space Planning Design of House Layout To The Traditional Houses in Shibam, Yemen

An Evaluation of Space Planning Design of House Layout To The Traditional Houses in Shibam, Yemen

Uploaded by

priyaCopyright:

Available Formats

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No.

2; July 2010

An Evaluation of Space Planning Design of House Layout

to the Traditional Houses in Shibam, Yemen

Anwar Ahmed Baessa

School of Housing, Building and Planning

Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang

E-mail: anwarbaesa@yahoo.com

Ahmad Sanusi Hassan (Corresponding author)

Associate Professor

School of Housing, Building and Planning

Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang

Tel: 60-4-653-2835 E-mail: sanusi@usm.my, sanusi.usm@gmail.com

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to evaluate on how good traditional house design is able to give residential satisfaction

levels and could contribute towards habitability in Shibam, Yemen. House design in this study is a subject

dealing with efficient space-function design of the house layout which shows cultural aspects of the community.

Houses in Shibam typify the traditional architecture which reflects to the structure of family, and social and

cultural realms. The houses comprises mid and high-rise mud brick house types, considered as one of the earliest

high-rise house type built in the world. Today, the city of Shibam with mid and high-rises mud brick house types

is recognized as one of the heritage sites under UNESCO’s World Heritage Lists. The literature study is

conducted to understand the definitions of the title, which is important to identify the measurable factors for the

research analysis. The study finds that diwan, dining area, bedrooms, bathrooms, corridor and storage, courtyard

and balcony, and the composition of the rooms’ layout are important measurable checklist’s factors under

category of space planning and function. There are two types of the research analyses which are qualitative and

quantitative analysis. The qualitative analysis is a study by the researcher based on the researcher’s observation

on the house design during the site visit while the quantitative analysis is from the respondents’ answers (300

respondents) on their satisfaction level from the research questionnaires. With high average scores of 94% in

qualitative and 90% in quantitative analysis on satisfactory level, it shows that both results of qualitative and

quantitative analysis support the research assumption. In that light, within the ambit of this study, the house

design in Shibam can and does serve as a reference.

Keywords: House design, Space planning and function, Shibami houses

1. Introduction

This paper discusses space planning and function of the traditional house design in the city of Shibam at

Hadhramout region, Yemen. The study will look on how the Shibami house design can serve as model of

habitability. The city of Shibam is named after its King Shibam bin Al-Harith bin Hadhramout bin Saba

Al-Asghar. This area is about 600-700 meters from the sea level. It had played a crucial role as a capital of Wadi

Hadhramout in the fourth B.C. (Damluji, 2007). This city is built on a small mound or on a podium. The present

city of Shibam is situated in the core of Wadi Hadhramout above the ruin of the ancient city of Shibam. The city

of Shibam today (Figures 1 and 2) is one of the cities in the world that is recognized as World Heritage site and

placed under the UNESCO World Heritage lists since 1982 for its uniqueness of its house form and design

(Lewcock, 1986). The houses are mid and high-rise mud brick house types. The house units for generations are

dwelled by households with extended family system with their parent’s, son’s, daughter’s family units.

This tradition has been widely practiced in Shibam, Yemen especially among the low and middle income

families (UN-HABITAT, 2002) where it has shaped organization of space planning and function in the house

layout. This sustenance has been seen to permit the development of the local culture, religious values and

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 15

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

promotion of regional identity of the traditional architecture. Considering these, a study on the traditional house

design of the mid and highrise (from 3 storeys to maximum of 9 storeys) houses in Shibam (Figures 2) is deemed

important as well. The result of this study will be able to serve as a reference to the present and future development

of house design.

2. Literature study

This section discusses definitions of the terminological terms used in this study. These important definitions are

house design, space planning and function, and Shibami houses as follows:

2.1 House Design

The Arabic dictionary Al-Munjid (Al-Balabki, 1987) states that a house (al-sakan) means a place, “…to settle

down, relax, become calm, calm down, reside in a place, and house unit." In Oxford Dictionary (Allen, 1987), a

house is defined as “…a building for human habitation.” It covers the “…dwelling of houses as a provision of

shelter or lodging.’ The United Nations (United Nations, 1977) defines a house not only as a shelter but also as a

mean of the creation of communities. House design means the quality of the house layout in terms of the

organization and the allocation of living space areas relative to the key functions that a household requires which

is space planning and function. Such a layout always sets to measure the quality of a house. It has been

suggested by Caudill (1978) that an adequate layout always takes care of both the current and the future needs;

and such needs may be evaluated on the basis of quality rather than the cost, size and building that make up the

physical environment that the residents interact with. Therefore, the living space in house design that man

creates should meet a kind of needs, and the design adequacy calls for the ability of the designer to put all the

required elements within a defined and cleared relationships.

2.2 Space Planning and Function

According to Caudill (1978), a space is a room which consists mainly of several spaces. Some rooms are

interlocking and some are distinguishable. That is, some spaces are restricted with no openings and no space for

movement. A static space may be created by closing up the bedroom at night, drawing the drapes, and shutting the

doors. Citing Schulz (1971), Zevi (1957) holds that architecture is the "art of space" without defining the nature of

the space itself. Here, the concept of space is immaturely realistic as is the case with the researchers in this field

who look at it as a uniform extension of 'material' that can be 'modeled' in several ways. Awareness of Shariah

(Islamic Law) principles and references by the architects while designing the house design integrated with social

aspects is lacking. Shariah law provides an essential body of legislation to enhance the social life of people,

including the built environment: it encourages people to live peacefully and to share responsibilities to enhance

their social and urban life (Akbar, 1992; Allam et. Al, 1993; Ibrahim, 1994; and Eben Saleh, 1998). Many studies

have been done which suggest the importance of spatial layout in house design. Here are some of them: As

quoted by Sheikh Alalbany (2007) in one of the Hadiths that Prophet Mohammad (peace be upon him) said;

"Contentment comes from four: good wife, spacious dwelling, kind-hearted neighbor and obedient riding animal.

And four sources of unhappiness: bad neighbour, bad wife, narrow dwelling and disobedient riding animal."

3. Factors of House Design in Space Planning and Function in Shibam

This section will identify the factors by space planning and function of house design of the traditional houses in

Shibam. These factors comprise five important topics as follows:

3.1 Space Planning and Function

According to Al-Shibany and Al-Madhajy (2000), the layout of interior space and function becomes an

important factor by the local master builders when building the traditional Shibami houses. Nagib argued this

spatial design has preserved the local culture over the years. He also noticed that the design is relevant towards

the sustainable development. In Shibami house design, the space planning and function consists of five important

factors which are as follows:

a. Diwan, dining area, bedrooms

b. Bathrooms

c. Corridor and storage

d. Courtyard and balcony

e. Compositions of the rooms’ layout

16 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

3.1.1 ‘Diwan’, dining area, bedrooms

In Shibami house design, diwan, dining area and bedrooms are closely related to each other. These three factors

cannot be described into separate entities as they cover interrelated social activities. The diwan consists of the

following spaces: (a) living room, (b) visitor room, and (c) furniture setting. The dining area consists of the

following spaces: (a) dining room, (b) kitchen, and (c) top floor room/terrace. The bedrooms comprises

following features: (a) master bedroom, (b) bedroom for the males, and (c) bedroom for the females. Damluji

(1992) argued that the main reception room or (Majlis or Diwan) (Figure 3 & 4) is accessible through a door

located at the entrance of the shorter side. According to her, until the last century, these doors were not higher

than 1.2 meters. The frames are carved deeply and the surfaces are decorated with long iron nails with huge

heads (5cm) varnished with lead. He also noted that on both sides of the door, wooden chests are placed that are

used to place sleeping mats and pillows during daytime. In addition, these chests are studded with brass or tinned

iron ornaments that are considered as the only furniture in the room.

Damluji (1992) noted that in the first floor there are several mahadir (the singular is al mahdarah which are the

house main living and reception rooms. The 'mahdarah' is a large room split by four columns or (ashum) (plural

of saham meaning arrow). There is a smaller room or (mahdarah) which is adjacent to the larger one reserved

for reception or sleeping place during the winter time. In addition to mahadir, there is a house stairway to the

second floor (Damluji, 1992). Damluji (1992) noted that the second floor consists of the living rooms reserved

for woman and for carrying out ceremonies such as weddings. These living rooms are divided in the same or

similar way as the mahadir. A large reception room divided by four poles or columns opens onto small,

windowless, locked room known as al maghlulah which contains more than one niche and used for several

purposes such as sitting room in winter or to store utensils and clothes. He adds that a kitchen and a toilet

(taharah) are located on the third floor. This is a common house layout design among the traditional houses in

Shibam. The toilets and the kitchens are built on top of each other next to the service well that contains the

disposal openings and the canals. The third floor is called al marawih or tarawih (Figure 5). There are rooms

where business, social activities, and reception of male strangers are carried out. Other private rooms are

reserved for daytime activities for women and children. On this floor there is a series of roof terraces. The fourth

floor is reserved for women activities. It consists of a large mirwah with a small marawih on top of them that

open out towards the roof or the sky called raym (plural is ruyum). They are similar to terraces but more like

patios in design and function and are used for living and sleeping during the summer season (Damluji, 1992).

3.1.2 Bathrooms

There are two types of bathrooms: (a) bathrooms for male, and (b) bathrooms for female. According to Damluji

(1992), the main part of the toilet generally is an open canal leading to an opening in the wall; and it extents to

an elevated platform on each side to stand on. Sometimes it is accompanied with a system of earthenware pipes,

or cylinders completed of burnt clay and known as qasb, which are fitted after being painted with lime (Nurah)

on the inside. Generally, the conventional arrangements for disposing of waste water depend on a network of

openings in the back or side walls, open canals flowing along these walls and the ground at the back of the

constructions and on pits (habisah) combined by a number of adjoining and connected thin constructions

(Damluji, 1992).

3.1.3 Corridor and Storage

This factor consists of the following spaces: (a) corridor space, (b) stairs space, and (c) storage and basement

floor. Leslie (1991) observed that there is only a single door which leads to the staircase from the entrance. A

massive mud is created to leap around the staircase which runs throughout the height of the houses. For security

reasons, there is no window built on the walls of the ground floors, except for a few openings on the ceilings for

ventilation purposes. The ground floor (Figure 6) is usually reserved for storage purposes. In a ground floor,

there are a number of mayasim (storages) that are used to store grains, dates and other crops. In addition they are

also a place to store daily work tools. There are terraces areas to keep cattle at night. The height of the ground

floor ranges from 4 to 5 meters (13-16 feet). Leslie added that there is a passage that leads to a staircase to the

upper levels. Leslie (1991) further noticed that as they are not used for living spaces, and for ventilation purpose,

there are either small narrow longitudinal or circular holes known as al-Ukrah in the upper parts of the facade

walls constructed higher than the door’s level.

Furthermore, Damluji (1992) noted that the ground floor consists of a vertical tunnel opened towards the sky

called manwar or shammash built next to the stairwell, which stretch throughout the house floors, from the

ground floor to the roof level. These tunnels allow the sunlight penetrates into the house through openings in the

common wall, and they are also for air ventilation. He further noted that the stairwell is located centrally around

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 17

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

arus, a vertical column near the entrance forming the main support carrying the building loads. Damluji (1992)

argued that sometimes (due to the nature of the terrain during the actual construction) there is one and sometimes

two additional basement, known as khann. This space is to tackle the ground level’s variation between the main

street level and the level of the city's raised site. The construction of khann accommodates this gradient (between

the lower ground point of the slope and Shibam's higher flat site); and the slope is leveled with a fortified base

and additional foundation for the normal five or six storey above. The master builders do not count the basement

floor (khann) as an additional floor, or as a separate storey, even if it consists of two floor levels.

In addition, the ground and first floors consist of the house main entrance that leads to a narrow corridor (dacha)

or (dayqah). These two terms are derived from the Arabic language meaning “tightness or narrowness”.

Damaluji also noticed that this dakhlah leads to rooms called al mayasim (singular of maysamah) used for

storing grain and dhura ‘corn stalk’. He adds that in general, the ground floor is considered as the house main

storage area or diyaq (plural of dayqah) which is used also as a shop. Most houses have their entrance off

enclosed courtyards surrounded by fences whose walls have prickles on the top, (Figures 6 and 7). There is only

one main entrance that opens into a central passage with windowless walls, leading to animal barn (for example,

goats and sheep were often kept in the upper floor) (Damluji, 1992).

3.1.4 Courtyard and Balcony

In Shibami houses, courtyard is a spacious area which gives shades and protection from direct sun rays, wind

and sand (Al-Bahar, 1984). This factor consists of the following spaces: (a) the courtyard space; and (b) the

balcony space. Damluji (1992) mentioned that the houses in Shibam have been built with practical expansion in

mind in that the house designs are vertically; hence the houses have been built very close to each other. In the

house design of the top floors (ruyum, and tayarim), there are potential expansions at different locations and at

varied dimensions. For example, to compensate for the traditional courtyard, the builders instead provide the

required alternative spaces that are exposed to the sky. This feature preserves the privacy factor of the interior as

it is contained in an enclosure within the exterior walls of the house design. There is no balcony constructed in

this traditional house.

3.1.5 Compositions of the Rooms Layout

The arrangement of the interior space layout in this Shibami house is organized based on the space-function

design (Baeissa & Hassan, 2005). There is only a single entrance door which leads to a staircase. This door is

always situated against the external walls, (Figure 8). A massive mud wall leaps around the staircase which runs

throughout the height of the houses. The ground and the first floors are usually reserved for storage purposes.

There are opened rooms at the central landing on each floor. There are also family rooms; and this area also can

be used for eating, sleeping or to conduct business at different periods. On the upper floor there is a large hall

called diwan, (Figure 9) which is not always used by the family. It is a place reserved for the guests,

entertainment and special occasions. This room has small washing area at one corner and it is separated from the

rest of the other spaces. It is also an area used for praying and dining, and a small part of the area is for ablution

(Baeissa & Hassan, 2005).

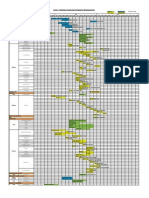

4. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

This research methodology consists of qualitative and quantitative survey. In qualitative survey, the criteria for

evaluation are on qualitative analysis from checklist factors as discussed in the literature review based on the

researcher’s observation on the house design during the site’s visit. The answer “Yes” represents as satisfactory

and “No” as unsatisfactory. For example, if the visitor’s room is satisfactory, the answer “Yes” will be marked as

‘x’, but when it is unsatisfactory, the answer is "No" will be marked as ‘x’. On the other hand, the quantitative

survey is the answers from the respondents. There are 300 respondents who reside in Shibam involved in this

survey. One respondent is selected for one building block. (mid or high-rise building). The selection is based on

from the level of the house unit. For example; the first respondent is from a house unit at the ground level of the

first building block; the second respondent is from a house unit at the second level of the second building block;

and so on. The answers are based on their satisfaction level from questionnaires related to the same checklist

factors. The measurable scale is based on five rating scales of preferences in which the respondent is required to

identify only one for each question. These rating scales are: No. 1: worst, No. 2: bad, No.3: no comment, No. 4:

good and No.5: best. According the Likert Scale (2006) an important distinction must be made between a Likert

scale and item. The Likert scale is the sum of the responses on several Likert items. The objective of the

quantitative survey in this study is to identify the factors of the level of satisfaction as perceived by the residents.

The results of the qualitative and the quantitative analysis of the data are presented in subsection of space

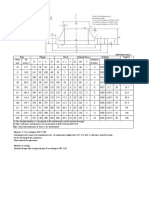

planning and function as follows (Table 1):

18 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

4.1 Discussions: Results of the Qualitative Analysis

The study finds that all results of the qualitative analysis are positive (except answers of balcony), which means

that space planning and functions of the house design are relevant as a good model for a house type in Shibam.

With respect to the category in space planning and function of diwan, dining area, bedrooms, bathrooms,

corridor and storage, and courtyard and balcony, the only negative response in this analysis is in the balcony.

The study finds that there is no balcony as a part of the house design in Shibami houses compared to other house

types in Yemen. The study suggests consideration for a need to integrate balcony as one of the factors in the

house design in the present and future development. Table 1 shows that the overall average result is very

satisfactory with 94%. The result illustrates that the traditional house design of the space planning and functions

fulfills the residents’ needs and gives them satisfaction.

4.2 Discussions: Results of the Quantitative Analysis

The study finds that the quantitative analysis also has positive results as in the qualitative analysis. All results

have cumulative answers by the respondents with more than 90% score except space planning and functions of

diwan, courtyard and the house layout’s composition. This analysis also supports the result from qualitative

analysis that balcony is not part of the house design in Shibami houses. It shows that there is a need to emphasis

on diwan, courtyard and the house layout’s composition as important design elements for the upgrades on the

habitability. The summarized results of this quantitative analysis are as in (a) through (g) as follows:

a) Diwan

Eighty eight percent of the respondents from Shibam are satisfied with the diwan (the living, visitors’ rooms and

furniture setting). In another words, generally the residents of Shibam satisfy with the diwan in their houses.

b) Dining area

The analysis finds that 96% of the respondents perceive the dining area in their houses as satisfactory.

c) Bedrooms

With respect to the bedrooms, 92% of the respondents perceive their bedrooms as satisfactory.

d) Bathrooms

With a score of 94% on this factor, there is no doubt that the respondents of Shibam are satisfied with their

bathrooms.

e) Corridor spaces and storage

On this factor, with a score of 96% the respondents give the answer as satisfactory.

f) Courtyard and balcony

Seventy eight percent of the respondents give satisfactory answers of the importance of courtyards in their house

design. The question on ‘balcony is not relevant because there is no balcony as a part of the house design in

Shibami house.

g) Composition of the house layout

Eighty three percent of the respondents have expressed satisfaction to the composition of the house layout.

5. Conclusion

The study concludes that the traditional houses in Shibam have a good house design with references to its space

planning and functions. Both results of the qualitative and quantitative analysis support the research assumption

that the traditional houses of Shibam can be considered as a model for the present and future development of

house design in Hadramout region, Yemen, in parallel with Shibam’s recognition as a traditional city under

UNESCO’s World Heritage Lists. Table 1 shows that it is quite apparent that the respondents from Shibam have

rated high satisfactory level in all the factors. As such these high average scores (triangulated between 94% in

qualitative and 90% in quantitative analyses) undoubtedly have served as expressions of much satisfaction

towards the house design and the nature of the amenities there. In that light, within the ambit of this study, the

house design in Shibam can and does serve as a reference. The study has used the layout of the house design of

the traditional houses of Shibam as the reference model. At the end of the study, it is suggested here that the

study has made the contributions with respect to people’s perception on the habitability of house design for the

low income group in Yemen in particular and some general ideas about habitability of house design in the field

of architecture in general. It has provided the definitions of the terms ‘house, designs and habitability’ within the

ambit of the perception of the residents in Shibam.

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 19

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank to Universiti Sains Malaysia for a financial support to this research article.

References

Aga Khan Award for Architecture. (2007). Intervention Architecture Building for Change. London: Tauris & Co

Ltd.

Al-Albany, N. (2007). Scientific White Forum. [Online] Available: http://www.albaidha.net/vb/showthread.

php?t = 4748 (25th March, 2008).

Al-Bahar, H. (1984). Traditional Kuwaiti Houses, MIMAR 13: Architecture in Development. Taylor, B.B. (ed.).

Singapore: Concept Media. 13, 71-78.

Al-Balabki, M. (1987). Kamus Al-Mawrid. Beirut: Darul Ilm Lelmalaein. (Arabic version)

Allam, K., Abdullah, M. & Al-Dinary, M. (1993). The History of Cities Planning. Cairo: Al-Aangalo.

Allen, R.E. (1987). The Oxford Dictionary of Current English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Al-Shibany, A.R. & Al-Madhajy, M. (2000). Al-Saluk fi Tashkeel Al-fadhah Al-memari fi Al-Yameen.

(Behaviour of the Architectural Spaces Composition in the Yemeni Clay Architectural). Proceedings of First

Scientific Conference of Clay Architecture on the Threshold of the 21st Century on 10-13th February 2000.

Mukalla: Hadhramout University of Science and Technology.

Baeissa, A.A. & Hassan, A. S. (2005). Sustainable Mud Brick Construction: Material in High-rise Houses at

Hadhramout Valley, Yemen. Proceedings of the International Conference on Construction and Real Estate

Management: Challenge and Innovation in Construction and Real Estate on 12-13th December 2005. vol.2,

Penang: Universiti Sains Malaysia.

Caudill, W. et. al. (1978). Architecture and You: How to Experience and Enjoy Buildings. New York:

Watson-Guptill Publications.

Damluji, S.S. (1992). The Valley of Mud Brick Architecture Shibam, Tharim and Wadi Hadhramout. London:

Garnet Publishing.

Damluji, S.S. (2007). The Architecture of Yemen: From Yafi to Hadhramout. London: Laurence King Publishing

Ltd.

Eben Saleh, M. (1998). The Impact of Islamic Customary Law on Urban Form Development in Southwestern

Saudi Arabia. Habitat International, 22(4), 143-47.

Ibrahim, A. (1994). Islamic View to Urban Development. Cairo: Architectural and Planning Studies Centre.

Leslie, J. (1991). Building with Earth in South Arabi. MIMAR 38: Architecture in Development. Khan,

Hasan-Uddin (ed.). London: Concept Media Ltd. 38, 60-67.

Lewcock, R. (1986). Wadi Hadhramout and the Walled city of Shibam. London: UNESCO Publishing.

Schulz. C.N. (1971). Existence Space and Architecture. London: Studio Vista Publication.

UN-HABITAT. (2002). United Nations Human Settlements Programme. [Online] Available:

http://www.un-ngls.org/spip.php?page=article_s&id_article=819 (12th May 2006).

United Nations. (1977). The Social Impact of Housing: Goals, Standards. Social. Indicators and Population

Participation. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Zevi, B. (1957). Architecture and Space. Gendel, M. (trans.). New York: Horizon Press.

20 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

Table 1. Summary of the results in the analysis from the Checklist Factors.

Qualitative Quantitative

Factor Space Planning and Function

Survey Survey

Yes No

Diwan 88%

a

(a) living room x 87%

(b) visitor room x 88%

(c) furniture setting x 89%

Dining Area 96%

b (a) Dining room x 94%

(b) Kitchen x 96%

(c) Top floor room/terrace x 97%

Bedrooms 92%

c (a) master bedroom x 91%

(b) Bedroom for male x 93%

(c) Bedroom for female x 92%

Bathroom 94%

d (a) Bathroom for male x 95%

(b) Bathroom for female x 92%

Corridor and Storage 96%

(a) Corridor Space x 98%

e

(b) Stairs Space x 95%

(c) Storage and basement floor x 94%

Courtyard and Balcony 78%

f (a) Courtyard x 79%

(b) Balcony NULL 77%

g Composition of the rooms’ layout x 83%

N=17 Total 16 1 627

Total number of positive answers

over the total number of items 16/17 1/17 627/7

Overall average answers in percentages 94% 6% 90%

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 21

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

Figure 1. Old City of Shibam

Source: Aga Khan Award for Architecture

Figure 2. Shibami houses (mid and highrise buildings)

Source: Mukallatoday (2007)

Figure 3. Interior Space (Diwan) of Shibami House

22 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

Figure 4. The first floor plan

Top floor /terrace

Marawih

Figure 5. The third floor plan

Figure 6. The ground floor plan

Courtyard

Courtyard

Figure 7. Plans of a Traditional House in Shibam

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 23

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 2, No. 2; July 2010

Ground Floor Plan Main Facade

Scond Floor Plan Section

Figure 8. Interior space (diwan) of Shibami house

Figure 9. Circulation the interior space of Shibami house

24 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663

You might also like

- AISC Design Guide 24 - Hollow Structural Section Connections - 2nd EditionDocument356 pagesAISC Design Guide 24 - Hollow Structural Section Connections - 2nd EditionIvan Alejandro Miramontes MunguiaNo ratings yet

- Terms of Referance-Detailed Design & Construction Supervision - Light Rail Transit Project PDFDocument4 pagesTerms of Referance-Detailed Design & Construction Supervision - Light Rail Transit Project PDFakanages100% (1)

- A Multidimensional Framework For Unmanned Aerial System Applications in Construction Project ManagementDocument15 pagesA Multidimensional Framework For Unmanned Aerial System Applications in Construction Project ManagementAnonymous JwdzqOkl5HNo ratings yet

- Traditional Islamic-Arab House Vocabulary and SyntaxDocument8 pagesTraditional Islamic-Arab House Vocabulary and SyntaxsakNo ratings yet

- Tradicional Islamic PDFDocument6 pagesTradicional Islamic PDFEgonVettorazziNo ratings yet

- Traditional Islamic-Arab House Vocabulary and SyntaxDocument8 pagesTraditional Islamic-Arab House Vocabulary and SyntaxBarbarah MendonçaNo ratings yet

- Pitch Presentation StructureDocument11 pagesPitch Presentation StructuremariyaNo ratings yet

- Traditional Pol Houses of Ahmedabad: An Overview: Gaurav Gangwar, Prabhjot KaurDocument11 pagesTraditional Pol Houses of Ahmedabad: An Overview: Gaurav Gangwar, Prabhjot Kaurflower lilyNo ratings yet

- Traditional Islamic-Arab House: Vocabulary and SyntaxDocument6 pagesTraditional Islamic-Arab House: Vocabulary and SyntaxAmriKemenNo ratings yet

- 6.islamic IdeologyDocument8 pages6.islamic IdeologyAhtisham AhmadNo ratings yet

- @428 HouseDocument21 pages@428 HouseXI LUNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Paper - Architect Aditi GuptaDocument83 pagesDissertation Paper - Architect Aditi GuptaAditi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Modifying Factors of House Form Socio-Cultural Factors and House FormDocument5 pagesModifying Factors of House Form Socio-Cultural Factors and House Formmoni johnNo ratings yet

- RESIDENTS' INTEGRITY IN THE CONCEPT OF HIJAB IN A SMALL TYPE OF URBAN ROW HOUSE - ndSIS2022Document7 pagesRESIDENTS' INTEGRITY IN THE CONCEPT OF HIJAB IN A SMALL TYPE OF URBAN ROW HOUSE - ndSIS2022Syam FitrianyNo ratings yet

- 2020 Transformation of Vernacular Houses - Casue andDocument8 pages2020 Transformation of Vernacular Houses - Casue andalankarNo ratings yet

- Traditional To Modern Residential ArchitectureDocument11 pagesTraditional To Modern Residential ArchitectureRimsha AkramNo ratings yet

- 554-Article Text-1711-2-10-20201014Document27 pages554-Article Text-1711-2-10-20201014UMT JournalsNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 - DoneDocument4 pagesAssignment 2 - DoneArchitexture Build BetterNo ratings yet

- Louis Kahn, Correa, DoshiDocument52 pagesLouis Kahn, Correa, DoshiJaseer Ali100% (1)

- 48CXVDocument18 pages48CXVSonu MohapatraNo ratings yet

- Housing Typology AfricaDocument24 pagesHousing Typology AfricaCAPO CHICHI EliadadNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Houses of The Shan in Myanmar in The South-East Asian ContextDocument23 pagesVernacular Houses of The Shan in Myanmar in The South-East Asian ContextFranco Louis RomeroNo ratings yet

- 686-Main Article Text-1317-1-10-20181114 Visual Communication of The Traditional House in Negeri SembilanDocument12 pages686-Main Article Text-1317-1-10-20181114 Visual Communication of The Traditional House in Negeri SembilanbolehemailNo ratings yet

- Indian Vernacular PlanningDocument12 pagesIndian Vernacular PlanningMatthew JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Principles of Designing Optimized Dwelling Apartments in Small ScaleDocument11 pagesPrinciples of Designing Optimized Dwelling Apartments in Small ScaleDB FasikaNo ratings yet

- RajasthanDocument4 pagesRajasthanshantbhardwaj100% (1)

- Donia Zhang Courtyard Housing in ChinaDocument20 pagesDonia Zhang Courtyard Housing in Chinahuang miaoNo ratings yet

- An Architect S Adaptation To The Mass Production System A Quincy Jones S Tract HousesDocument9 pagesAn Architect S Adaptation To The Mass Production System A Quincy Jones S Tract HousesFahed FarwatiNo ratings yet

- Fakulti Kejuruteraan & Alam Bina, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), 43650, BangiDocument14 pagesFakulti Kejuruteraan & Alam Bina, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), 43650, BangiDiana ZulkifliNo ratings yet

- 5812-Article Text-13176-1-10-20181231Document23 pages5812-Article Text-13176-1-10-20181231AEGISNo ratings yet

- Arly Islamic Architecture and Structural Configurations: AbstractDocument8 pagesArly Islamic Architecture and Structural Configurations: AbstractedrisNo ratings yet

- Vol 4 Issue 5 M 37Document7 pagesVol 4 Issue 5 M 37Renuka ChalikwarNo ratings yet

- House Form & Culture: Amos RapoportDocument11 pagesHouse Form & Culture: Amos RapoportSneha PeriwalNo ratings yet

- Louis Kahn, Correa, DoshiDocument52 pagesLouis Kahn, Correa, DoshiJenifer MonicaNo ratings yet

- FullPaper SEATUC PDFDocument6 pagesFullPaper SEATUC PDFNurul syara ainaa RahimNo ratings yet

- FullPaper SEATUC PDFDocument6 pagesFullPaper SEATUC PDFNurul syara ainaa RahimNo ratings yet

- Syntax ErbilDocument11 pagesSyntax ErbilLuqman Sabir Ali AzizNo ratings yet

- Traditional Dwellings: An Architectural Anthropological Study From The Walled City of LahoreDocument7 pagesTraditional Dwellings: An Architectural Anthropological Study From The Walled City of LahoreAzka Gul ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- User's Perception of The Relevance of Courtyard Designs in A Modern Context: A Case of Traditional Pol Houses, AhmedabadDocument11 pagesUser's Perception of The Relevance of Courtyard Designs in A Modern Context: A Case of Traditional Pol Houses, AhmedabadGaurav GangwarNo ratings yet

- Un Estudio Tipológico, Ambiental y Sociocultural de Los Espacios Semiabiertos en El Mediterráneo Orientalvernáculo Arquitectura El Caso de ChipreDocument19 pagesUn Estudio Tipológico, Ambiental y Sociocultural de Los Espacios Semiabiertos en El Mediterráneo Orientalvernáculo Arquitectura El Caso de Chiprekatia.flor28No ratings yet

- Hausa Project 1Document23 pagesHausa Project 1ehizeleagbonyemeNo ratings yet

- JLR23 - 01 DwiRetno-DESAIN&DEKORASIDocument10 pagesJLR23 - 01 DwiRetno-DESAIN&DEKORASIRahmawan D. Prasetya100% (1)

- CIB11022Document9 pagesCIB11022Adi PrasetyaNo ratings yet

- Cours de Géographie de L'habitat 2 Année Semestre Quatre Responsable de La Matière: Mme: Tebbi HafidaDocument22 pagesCours de Géographie de L'habitat 2 Année Semestre Quatre Responsable de La Matière: Mme: Tebbi HafidaAmina AminaNo ratings yet

- Charles CorreaDocument73 pagesCharles CorreaTrishala ChandNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Houses of The Shan in Myanmar in The South-East Asian ContextDocument23 pagesVernacular Houses of The Shan in Myanmar in The South-East Asian ContextLulayNo ratings yet

- Hermanto and Hendriani - 2018 - BAGENEN-BOTOLAN - CompressedDocument13 pagesHermanto and Hendriani - 2018 - BAGENEN-BOTOLAN - Compressedmuhs.riyadi2No ratings yet

- 71-Article Text-113-1-10-20140518Document8 pages71-Article Text-113-1-10-20140518mariamNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Low Cost HousingDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Low Cost Housingz0pilazes0m3100% (1)

- Concurrence of Thermal Comfort of Courtyard Housing and Privacy in The Traditional Arab House in Middle EastDocument9 pagesConcurrence of Thermal Comfort of Courtyard Housing and Privacy in The Traditional Arab House in Middle Eastsweetdevil1993No ratings yet

- 3.4 Charles CorreaDocument60 pages3.4 Charles CorreaFathima NazrinNo ratings yet

- Islamic ArchitectureDocument3 pagesIslamic ArchitectureMoomal ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Traditional Approach Towards Contemporary Design: A Case StudyDocument11 pagesTraditional Approach Towards Contemporary Design: A Case StudyShaikh MohsinNo ratings yet

- 14-Weso OwskiDocument12 pages14-Weso OwskiSansSouciNo ratings yet

- Ca LNDocument51 pagesCa LNnetworkedurbanismNo ratings yet

- Space Use Patterns and Building Morphology in Yoruba and Benin Domestic ArchitectureDocument24 pagesSpace Use Patterns and Building Morphology in Yoruba and Benin Domestic ArchitectureLola Adeokun100% (1)

- Scientific African: Gali Kabir Umar, Danjuma Abdu Yusuf, Abubakar Ahmed, Abdullahi M. UsmanDocument8 pagesScientific African: Gali Kabir Umar, Danjuma Abdu Yusuf, Abubakar Ahmed, Abdullahi M. UsmanNafila AdrianaNo ratings yet

- The Riverfront Settlement Study of EcoximDocument7 pagesThe Riverfront Settlement Study of EcoximKshama SawantNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Vernacular ArchitectureDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Vernacular Architectureafedyqfbf100% (1)

- IJARVol 11Issue2Al-JokhadarJabiDocument16 pagesIJARVol 11Issue2Al-JokhadarJabiEunice Veanca ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ethnoarchaeology As A Tool For A Holistic Understanding of Mudbrick Domestic Architecture in Ancient EgyptDocument16 pagesEthnoarchaeology As A Tool For A Holistic Understanding of Mudbrick Domestic Architecture in Ancient EgyptLorenzoNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 - MODERNIST ARCHITECTS AND THEIR WORKSDocument90 pagesUnit 4 - MODERNIST ARCHITECTS AND THEIR WORKSpriyaNo ratings yet

- Department Presentation 2022Document52 pagesDepartment Presentation 2022priyaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 - Reactions To IndustrialisationDocument97 pagesUnit 2 - Reactions To IndustrialisationpriyaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - Imp TopicsDocument40 pagesUnit 5 - Imp TopicspriyaNo ratings yet

- Tod-2 Unit Ii Design Methodology MovementDocument67 pagesTod-2 Unit Ii Design Methodology MovementpriyaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Modernity - ArchitectureDocument82 pagesUnit 1 - Modernity - ArchitecturepriyaNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Evolution of Modern ArchitectureDocument79 pagesUnit 3 - Evolution of Modern ArchitecturepriyaNo ratings yet

- 1.UNIT I FinalDocument9 pages1.UNIT I FinalpriyaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Design - Vi Semester Unit Ii IDocument8 pagesTheory of Design - Vi Semester Unit Ii IpriyaNo ratings yet

- 5.unit V NotesDocument8 pages5.unit V NotespriyaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Design - V Semester Unit IiDocument11 pagesTheory of Design - V Semester Unit IipriyaNo ratings yet

- The Sustainability of Recycled Concrete As Green Material SolutionDocument7 pagesThe Sustainability of Recycled Concrete As Green Material SolutionpriyaNo ratings yet

- Electromagnetic RadiationDocument22 pagesElectromagnetic RadiationpriyaNo ratings yet

- SONA SIGMA-BLOCK Case-StudyDocument5 pagesSONA SIGMA-BLOCK Case-StudypriyaNo ratings yet

- Shaping Futures Final Report WEBDocument115 pagesShaping Futures Final Report WEBpriyaNo ratings yet

- PhDThesis-Developing A Systemic Framework For Applying LEED System-2014 - Walaa SalahDocument314 pagesPhDThesis-Developing A Systemic Framework For Applying LEED System-2014 - Walaa SalahpriyaNo ratings yet

- 5a - Boiler Construction Continued - Internals - Superheaters LockedDocument0 pages5a - Boiler Construction Continued - Internals - Superheaters Lockedganeshan100% (1)

- Cement Lining of PipesDocument26 pagesCement Lining of PipesVasilica BarbarasaNo ratings yet

- Din Flange Din 2627: (Dimensions in MM.)Document12 pagesDin Flange Din 2627: (Dimensions in MM.)Wisüttisäk PeäröönNo ratings yet

- Construction Safety and Health Through Design: January 2014Document25 pagesConstruction Safety and Health Through Design: January 2014nonku ngubaneNo ratings yet

- Reliance Expansion & Pump Tank Brochure - 210568-RPMCP00211Document2 pagesReliance Expansion & Pump Tank Brochure - 210568-RPMCP00211AlejandroVCMXNo ratings yet

- RCC Short NotesDocument5 pagesRCC Short Notesashok pradhanNo ratings yet

- Proposal Sheet SH 27 9.6.17Document526 pagesProposal Sheet SH 27 9.6.17praveenNo ratings yet

- Assignment. III Year Mp-IIDocument4 pagesAssignment. III Year Mp-IIshanthakumargcNo ratings yet

- JRC 2kW Radar Cable Connector InstallationDocument4 pagesJRC 2kW Radar Cable Connector InstallationAnonymous amfMbuTBkNo ratings yet

- Fosroc Conbextra Sureflow 100 BrochureDocument4 pagesFosroc Conbextra Sureflow 100 BrochurejasonNo ratings yet

- Nitoproof 30Document4 pagesNitoproof 30Arif FadillahNo ratings yet

- Vacuum Circuit BreakerDocument7 pagesVacuum Circuit BreakerShiv Kumar VermaNo ratings yet

- Code Commentary: D D D DDocument8 pagesCode Commentary: D D D DanantharajceNo ratings yet

- Swing Check Valve TIS ITALY DN40-200Document1 pageSwing Check Valve TIS ITALY DN40-200Aya Abd-ElghafarNo ratings yet

- ECCS Report No 039Document34 pagesECCS Report No 039Cpm102No ratings yet

- Dictionary of Concrete TechnologyDocument12 pagesDictionary of Concrete TechnologyJoseRodrigoPastorNo ratings yet

- Questions CE2203, CE2201Document13 pagesQuestions CE2203, CE2201titukutty6032No ratings yet

- Questions For Stress AnalysisDocument3 pagesQuestions For Stress AnalysisSunday PaulNo ratings yet

- T Mech Clamp CatalogueDocument29 pagesT Mech Clamp CatalogueKABIR CHOPRANo ratings yet

- Fibres On OHL - RowlandDocument33 pagesFibres On OHL - RowlandRelu LambeanuNo ratings yet

- Technical Specification N3 Wind Conditions: Design NotesDocument1 pageTechnical Specification N3 Wind Conditions: Design NotesMinh HoNo ratings yet

- 2.2.4 Construction Schedule For Mechanical WorkDocument2 pages2.2.4 Construction Schedule For Mechanical WorkĐình Nam100% (1)

- 1175 PDFDocument24 pages1175 PDFMuhammad HamzaNo ratings yet

- Paroginog 5-231 Pa3Document3 pagesParoginog 5-231 Pa3Nhes Audrey ParoginogNo ratings yet

- Cryofab CL CLPB Series Specs 15Document1 pageCryofab CL CLPB Series Specs 15anupamNo ratings yet

- Ahp ManualDocument38 pagesAhp Manualelectroplex56No ratings yet

- P C M RC-M (C & B) S B L: Katchalla Bala KishoreDocument63 pagesP C M RC-M (C & B) S B L: Katchalla Bala KishoreAnonymous w8tjcvmymNo ratings yet