Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Botes Desde Uruk

Botes Desde Uruk

Uploaded by

romario sanchezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Botes Desde Uruk

Botes Desde Uruk

Uploaded by

romario sanchezCopyright:

Available Formats

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire

Author(s): Małgorzata Sandowicz

Source: Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 74, No. 2 (October 2015), pp. 197-210

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/682337 .

Accessed: 15/10/2015 14:35

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal

of Near Eastern Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian

Empire

Małgorzata Sandowicz, University of Warsaw*

Introduction 1956,2 then updated by Herbert P. H. Petschow in

a note published in 1987.3 Shortly afterwards, Paul-

From mid-539 bc, Babylonia was preparing for an

Alain Beaulieu reconstructed the steps that the Eanna

attack that was to bring about the end of its last in-

temple of Uruk took in preparation for the forth-

digenous dynasty. It was only in Tašrītu, the seventh

coming invasion.4 A view from the north was recently

month of the local calendar, that the Persian army un-

added by Stefan Zawadzki, who published a document

der Cyrus II the Great ultimately entered Babylonia.

revealing that the city of Sippar was also getting ready

Early in that month, Cyrus defeated the Babylonian

for an attack.5 The present article will add six docu-

army at the border town of Opis. Shortly afterwards,

ments to the body of the forty already-known tablets

on the fourteenth of Tašrītu, the Persians captured

drafted in Uruk and Sippar in the last four months

Sippar, and in another two days they entered the city

before their capture by Cyrus. These texts will provide

of Babylon.1

data allowing a more detailed reconstruction of the

Thanks to an unusual wealth of sources, the months

final episode of Neo-Babylonian history.

preceding the Persian Blitzkrieg may be restored in

remarkable detail, revealing a fascinating picture of a

state on the eve of an invasion. The textual evidence Boats for Eanna

on the period shortly before and after the major Baby-

Apart from military preparations, the Babylonians

lonian cities were taken by the Persians was first put

undertook steps aimed at providing security for their

together by R. A. Parker and W. H. Dubberstein in

* I am indebted to Elizabeth Payne for the collation of YOS 6 2

R. A. Parker and W. H. Dubberstein, Babylonian Chronology

207, to Stefan Zawadzki for reading and commenting on the paper, 626 B.C.–A.D. 75 (Providence, RI, 1956), 13–14.

and to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive remarks and 3

H. P. H. Petschow, “Zur Eroberung Babyloniens durch Cyrus.

suggestions. The Trustees of the British Museum are kindly ac- Die letzten vorpersischen und ersten persischen Datierungen aus

knowledged for permission to publish tablets under their care. My den Tagen um die persische Eroberung Babyloniens – Bemerkun-

research in the Museum was possible by a grant from the National gen zu CT 55, 191,” NABU 1987/84.

Science Center (DEC-2012/07/B/HS3/01126). Cuneiform texts 4

P.-A. Beaulieu, The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 556–

are cited according to the abbreviation system of the Chicago As- 539 B.C., YNER 10 (New Haven, 1989), 220–24, and “An Episode

syrian Dictionary. in the Fall of Babylon to the Persians,” JNES 52 (1993): 241–61.

1

Nabonidus Chronicle III.9–12 (A. K. Grayson, Assyrian and 5

S. Zawadzki, “The End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire: New

Babylonian Chronicles, TCS 5 [Locust Valley, 1975], 109, hereafter Data Concerning Nabonidus’s Order to Send the Statues of Gods

Grayson, ABC). to Babylon,” JNES 71 (2012): 47–52.

[JNES 74 no. 2 (2015)] © 2015 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 022–2968–2015/7402–001 $10.00. DOI: 10.1086/682337

197

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

198 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

gods. Several major temples were ordered to bring their Paul-Alain Beaulieu9 who, having put the contracts

divine statues to the capital, which was assumed to be together with evidence from letters and royal in-

safer than the provincial centers. Such precautions were scriptions, demonstrated beyond doubt their Sitz im

occasionally followed in the course of preparation for Leben.10 Beaulieu has shown that six such boat-rental

wars: Merodach-Baladan II took several cult statues to contracts were concluded by the Eanna over a short

the marshes when fleeing before the Assyrians in 709 period between Dūzu (month IV) and Ulūlu (VI) of

and 700 bc; the gods of Kiš, Šapaṣṣu, and Sippar sought the seventeenth year of Nabonidus. Below, another

shelter in Babylon during the war against Assyria in four contracts belonging to the same dossier will be

626/625 bc; the usurper Nebuchadnezzar IV brought edited. With these documents included, the body of

the Lady of Uruk to the capital upon the approach of evidence becomes large enough to allow a study of

the army of Darius I in 521 bc.6 further details of the remarkable operation carried out

Still, the decision of Nabonidus to transport the by the Eanna.

gods to Babylon must have been considered extraor-

dinary; the issue occupies the central place in the brief The Eanna Boat Documents: Texts 1–4 11

and laconic Nabonidus Chronicle, a major historio-

For the first four documents, please see Figures 1–4.

graphic source of this period.7 The royal order brought

about drastic changes in the everyday routine of the Text 1. BM 114453 (1920-6-15, 49). 5.8 cm × 4.2 cm

affected temples. Babylonian gods were provided for

1. [ul]-tu u4.1.kám šá iti.ne ⸢mu.17.kám⸣

daily by highly specialized staff, following very strict

2. dnà-i lugal tin.tir.ki a-di u4.1.kám šá iti.⸢kin⸣

rules; any infringement upon these regulations could

3. giš.má šá 1 me 50 gur i-de-ku-ú šá mmu-ra-nu

bring about a cultic catastrophe. With the gods taken

4. a-šú šá mden-šeš.meš-su šá ina igi mba-la-ṭu a-šú

away, the temple system had to be reorganized com-

5. šá mdna-na-a-dù-uš a-na 5½ gín kù.babbar

pletely. The priests followed their gods to Babylon in

6. a-na i-di-šú a-na é.an.na id-din kù.babbar-a4

order to carry on with their duties, while the person-

5½ gín

nel back in the provincial temples were charged with

7. i-di giš.má-šú ul-t[u] é.an.na e-ṭi-ir

sending the provisions required for the divine meals.

8. mim-mu šá la 1 me 50 gur i-ma-ṭu-ú

The amounts of products necessary to keep the divine

9. a-ki-i šá kù.babbar-šú a-ḫa-meš ip-pa-lu

table full were, as will be argued below, significant.

A major difficulty entailed by this operation was rev.

obviously the shipment of sacrificial products. The

10. ina gub-zu šá mdnà-gin-numun lú.šà.tam é.an.na

most convenient means of transporting them to Baby-

11. a-šú šá mna-di-nu a mda-bi-bi mdnà-šeš-mu

lon was by boat, but one imagines that few temples

12. lú.sag lugal lú.en pi-qit-tu4 é.an.na

possessed a fleet sufficiently large for such purposes.

13. lú.mu-kin-nu mìr-din-⸢nin⸣ a-šú šá mba-laṭ-su

Temple officials had no choice but to rent.

14. a m⸢zálag⸣-d30 mdna-na-a-šeš-mu a-šú šá

Several boat rental contracts from this period of un-

u.gur-ina-sùḫ-sur

md

rest survive among documents of the Eanna of Uruk,

one of the temples that agreed to dispatch their gods

9

Beaulieu, Reign of Nabonidus, 222, and “An Episode in the

to the capital. The link between these documents and

Fall”: 244–47.

the transport of sacrificial goods to Babylon was first 10

One more letter that possibly refers to the Eanna’s operation

suggested by Grant Frame,8 and then elaborated by is YOS 3 53, in which the qīpu Anu-šar-uṣur writes to four scribes

of the Eanna from Babylon (following the introductory formula),

6

See M. Cogan, Imperialism and Religion: Assyria, Judah and asking for grain (200+500 kor on top of that sent earlier on).

Israel in the Eighth and Seventh Centuries B.C.E., SBL Monograph The amounts correspond to those shipped by the Eanna in the

Series 19 (Missoula, MT, 1974), 30–33, and P.-A. Beaulieu, “An discussed period. The letter is not dated, but it could have been

Episode in the Reign of the Babylonian Pretender Nebuchadnezzar written in the last year of Nabonidus: the period when both the

IV,” in Extraction & Control. Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stol- qīpu and the scribes were in office extends from the latter part of

per, ed. M. Kozuh et al., SAOC 68 (Chicago, 2014), 17–25. On the reign of Nabonidus until the fourth year of Cyrus (cf. K. Kle-

the spoilation of divine statues in the ancient Near East in general, ber Tempel und Palast. Die Beziehungen zwischen dem König und

see Cogan, Imperialism and Religion, 24–41. dem Eanna-Tempel im spätbabylonischen Uruk, AOAT 358 [Mün-

7

Grayson, ABC, 104–11. ster, 2008], 31, 35–36). The letter mentions that part of the grain

8

Grant Frame, “Some Neo-Babylonian and Persian Documents should be sent with Ubār. Could he be identical with the boatman

Involving Boats,” OrAn 25 (1986): 38. References to texts in this of YOS 6 215?

article will be identified as “Frame, ‘Boats’.” 11

The tablets are reproduced at their approximate original size.

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire F 199

Figure 1—BM 114453 (Text 1) Figure 3—BM 114473 (Text 3)

Figure 2—BM 114465 (Text 2) Figure 4—BM 114486 (Text 4)

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

200 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

15. a lú.é.bar-bára lú.umbisag mki-na-a 14. šá mdin-nin-šeš.meš-mu a mden-ú-sa-⸢tu4⸣

16. a-šú šá mnumun-ia unug.ki iti.šu 15. mmu-še-zib-den a-šú šá mtin-su a mlú-didim

17. ⸢u4⸣.30.kám mu.17.kám ⸢dnà⸣-i 16. lú.umbisag mba-la-ṭu a-šú

u.e. u.e.

18. lugal tin.tir.ki 17. šá mmu-še-zib-den ⸢unug.ki iti.šu⸣

[(For the period) fr]om the first of Abu of the seven- 18. u4.30.kám mu.17.kám ⸢dnà-ní⸣.[tuku]

teenth year of Nabonidus, king of Babylon, until the l.h.e.

first of Ulūlu, (Balāṭu) has rented to the Eanna a boat

that takes a 150-kor (load), the property of Murānu/ 19. lugal tin.tir.ki

Bēl-aḫḫē-erība that is at the disposal of Balāṭu/ (For the period) from the first of Abu of the [seven]

Nanāya-ēpuš, for five-and-a-half shekels of silver. teenth year of Nabonidus, king of Babylon, until the

He has received from the Eanna the said five-and-a- first of Ulūlu, Arad-Innin/Marduk-iqī[ša?]//Ḫunzû

half shekels of silver, the rent of his boat. has rented a boat to the Eanna for six-and-a-half shek-

els [of silver].

Whatever (part of the boat-load) will be missing to

(the total of) 150 kor, they will mutually make adjust- Arad-Innin re[ceived the said] six-and-a-half shekels

ment with regard to his silver. [of silver], the rent of [his bo]at.

In the presence of: Nabû-mukīn-zēri/Nādin// In the presence of: Nabû-mukīn-zēri/Nādin[//]

Dābibī, the chief administra- Dābibī, the chief administra-

tor of the Eanna, tor of the Eanna,

Nabû-aḫu-iddin, the royal super- Nabû-aḫu-iddin, the [royal su-

visor of the Eanna. per]visor of the Eanna.

Witnesses: Arad-Innin/Balāṭsu//Nūr-Sîn, Witnesses: Arad-Innin/Innin-aḫḫē-iddin//

Nanāya-aḫu-iddin/ Bēl-usātu,

Nergal-ina-tēšê-ēṭir// Mušēzib-Bēl/Balāṭsu//

Šangû-parakki. Amēl-Ea.

Scribe: Kināya/Zēria. Scribe: Balāṭu/Mušēzib-Bēl.

Uruk, the thirtieth of Dūzu, seventeenth year of Na- Uruk, the thirtieth of Dūzu, seventeenth year of

bonidus, king of Babylon. Naboni[dus], king of Babylon.

Text 2. BM 114465 (1920-6-15, 61). 5.7 cm × 4.0 cm Text 3. BM 114473 (1920-6-15, 69). 5.7 cm × 3.9 cm

1. ul-⸢tu u4.1⸣.kám iti.ne 1. ⸢ul ⸣-tu u4.1.kám šá iti.ne mu.17.kám

2. šá mu.1[7.kám dn]à-ní.tuku lugal tin.tir.ki 2. dnà-i lugal tin.tir.ki a-di u4.1.kám šá iti.kin

3. a-di u4.1.kám šá iti.kin ⸢giš⸣.má 3. giš.má šá mdutu-a-a a-šú šá mdna-na-a-mu

4. šá mìr-din-nin a-šú šá m⸢damar⸣.utu-b[a-šá?] 4. a-na 6½ gín kù.babbar a-na i-di-šú a-na

5. a<<-šú šá>> mḫu-un-zu-ú a-na ⸢6½ gín⸣ 5. é.an.na id-din kù.babbar-a4 6½ gín

[kù.babbar] 6. ⸢i⸣-di giš.má-šú ul-tu é.an.na

6. a-na i-di-šú(over erasure) a-na é.an.na id-din 7. e-ṭi-ir

[kù.babbar-a4] rev.

7. 6½ gín i-di giš.m[á-šú]

8. mìr-din-nin e-ṭ[ir] 8. ina gub-zu šá mdnà-gin-numun lú.šà.tam é.an.na

9. a-⸢šú⸣ <šá> mna-din a mda-bi-bi mdnà-šeš-mu

rev. 10. lú.sag lugal lú.en pi-qit-tu4 é.an.na

9. ina gub-zu mdnà-gin-numun (erasure) 11. ⸢lú.mu⸣-kin-nu mìr-din-⸢nin⸣ a-šú šá mdù-dinnin!

10. lú.šà.tam é.an.na a-šú šá mna-din [a] 12. a mšu-dna-na-a mba-ni-ia a-šú

11. m(over erasure)da-bi-bi mdnà-šeš-mu lú.sa[g lugal] 13. [šá] ⸢m⸣dnà-pab a mdnà-šar-ḫi-dingir

12. lú.en pi-qit-ti é.an.na 14. [lú.umbisa]g m⸢na⸣-din a-šú šá mden-šeš.

13. lú.mu-kin-nu mìr-din-nin a-šú meš-⸢ba⸣-šá

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire F 201

15. [a me]-gì-bi unug.⸢ki⸣ iti.šu u4.30.kám els of silver monthly. (The contract comes into effect)

on the twenty-third of Abu.

u.e.

16. [mu].17.⸢kám⸣ dnà-i lugal e.ki In the presence of : Nabû-mukīn-apli, [the chief ad-

ministrator] of the Ezida,

(For the period) from the first of Abu of the seven- Nabû-mukīn-zēri, the chief ad-

teenth year of Nabonidus, king of Babylon, till the first ministrator of the Eanna.

of Ulūlu, Šamšāya/Nanāya-iddin has rented a boat to Witnesses: Lâbāši-⸢Marduk⸣/Arad-Bēl//

Eanna for six-and-a-half shekels of silver. Egibi,

He has received from the Eanna the said six-and-a-half Šamaš-mukīn-apli/

shekels, the rent of his boat. Madānu-aḫḫē-iddin//

Šigū<a>.

In the presence of: Nabû-mukīn-zēri/Nādin//

Scribe: Rēmūt/Iddinunu.

Dābibī, the chief administra-

Uruk, the twenty-first of Abu, seventeenth year of

tor of the Eanna,

Nabonidus, king of Babylon.

Nabû-aḫu-iddin, the royal super-

visor of the Eanna. This contract differs from the other ones in several

Witnesses: Arad-Innin/Ibni-Ištar// respects. Firstly, there is no mention of the payment

Gimil-Nanāya, received and no temporal limitation to the rental is

Bānia/Nabû-nāṣir// named. These are presumedly only formulaic nuances.

Nabû-šarḫi-ilī. The second irregularity is the appearance of two of-

[Scrib]e: Nādin/Bēl-aḫḫē-⸢iqīša⸣[//E]gibi. ficials: the chief administrator of the Ezida of Borsippa

Uruk, the thirtieth of Dūzu, seventeenth year of Na- (on which, see below p. 203), and Lâbāši-Marduk,

bonidus, king of Babylon. the supervisor of the Eanna’s bakers. As follows from

a letter published by M. Weisberg,12 Lâbāši-Marduk

See p. 203 for Bazūzu, the brother of the first wit-

accompanied the statue of Ištar to Babylon, and coor-

ness Arad-Innin/Ibni-Ištar//Gimil-Nanāya, and his

dinated the supplies of sacrificial products from there.

involvement in the transport of sacrificial grain.

His presence in Uruk must have been temporary; per-

Text 4. BM 114486 (1920-6-15, 82). 5.6 cm × 4.1 cm haps he was accompanying the šatammu of the Ezida.

1. giš.má šá 2 me gur i-de-ku-ú šá

2. mdnà-ùru-šú a-šú šá mdnà-ib-ni Contracts for Boat-Rentals

3. ul-⸢tu⸣ u4.23.kám šá iti.ne a-na

4. iti 7 gín kù.babbar a-na i-di-šú The documents follow a standard formulary of boat-

5. a-na níg.ga dgašan ⸢šá unug.ki id⸣-[din] rental contracts:13 they identify boat owners and

boatmen, specify rental periods, rental fees, and oc-

rev. casionally also vessel capacities (see Table 1). Their

6. ina gub-zu šá mdnà-gin-ibila l[ú.šà.tam] operative sections close with receipt clauses confirm-

7. é.zi.da mdnà-gin-numun lú.⸢šà.tam⸣ ing that the rental fees were paid. The lists of witnesses

8. ⸢é⸣.an.na lú.mu-kin-nu mla-ba-ši-d⸢amar.utu⸣ that follow open with the names of temple officials in

9. a-šú šá mìr-den a me-gi-bi whose presence the documents were drafted.

10. mdutu-gin-ibila a-šú šá mddi.ku5-šeš.meš-mu Three sets of documents were produced on the

11. a mši-gu-ú-<a> lú.umbisag same days; this coincidence offers insight into the

12. mre-mut a-šú šá msum-nu-nu unug.ki! temple’s daily chancellery practice. Two texts written

13. iti.ne u4.21.kám mu.17.<kám> on the twenty-ninth of Dūzu (Frame, “Boats” no. 5,

and YOS 19 11) were, as expected, drafted by the same

u.e.

14. dnà-i lugal tin.tir.ki 12

M. Weisberg, “A Neo-Babylonian Temple Report,” JAOS 87

(1967): 8–12. For collations and an extensive commentary on the

(Concerning) a boat that takes a 200-kor (load), the letter, see Beaulieu, “An Episode in the Fall”: 248–57.

property of Nabû-uṣuršu/Nabû-ibni: he has (hereby) 13

Cf. Frame, “Some Neo-Babylonian and Persian Documents

ren[ted] it to the treasury of the Eanna for seven shek- Involving Boats”: 36.

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

202 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

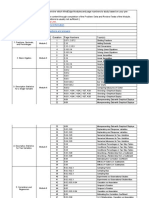

Table 1—Eanna boat rentals in the seventeenth year of Nabonidus.

Text Date Boat owner // boatman Capacity Rental Rental period Officials

(in kors)1 fee present

YOS 6 215 28.4.17 Ubār/Nabû-šumu-ibni (170) 6š 1 month –

(1.5–1.6)

Frame, “Boats” 29.4.17 Aḫušunu (slave of Nabû-rēmu-šukun) 30 3š 1 month šatammu

no. 5 (PTS 2301) ↪Nabû-mušētiq-uddī/Nabû-uṣalli (1.5–1.6) bēl piqitti

YOS 19 11 29.4.17 Ea (temple) 180 6.5 š 1 month šatammu

↪Lāqīpi/Ea-kāṣir (1.5–1.6) bēl piqitti

Text 1 30.4.17 Murānu/Bēl-aḫḫē-erība 150 5.5 š 1 month šatammu

↪Balāṭu/Nanāya-ēpuš (1.5–1.6) bēl piqitti

Text 2 30.⸢4⸣.17 Arad-Innin//Marduk-iqī[ša?]//Ḫunzû (180) 6.5 š 1 month šatammu

(1.5–1.6) bēl piqitti

Text 3 30.4.17 Šamšāya/Nanāya-iddin (180) 6.5 š 1 month šatammu

(1.5–1.6) bēl piqitti

YOS 6 195 8.5.17 Kināya/Bēl-nā’id 150 5š 1 month šatammu

(10.5–10.6) bēl piqitti

Text 4 21.5.17 Nabû-uṣuršu/Nabû-ibni 200 7š from 23.5 on šatam Ezida

šatam Eanna

TCL 12 121 6.6.17 Murānu/Bēl-aḫḫē-erība 150 5.5 š 1 month šatammu

↪Balāṭu/Nanāya-ēpuš (6.6–6.7) bēl piqitti

YOS 19 12 [6].6.17 Nabû-šar-aḫḫēšu/Ea-taqbi-līšir 120 4.5 š [1] month šatammu

↪Guzānu/[. . .]-ṣānu-ēreš ([6].6–6.7) bēl piqitti

1 The numbers in brackets are either adopted from contracts with identical rent or calculated based on the assumption that one shekel was enough to ship

an average of 28 kors (values of 27–30 kors are attested in the dossier).

Table 2—Witnesses and scribes of contracts drafted on 30.4.17Nbn

Text Text 1 Text 2 Text 3

Ina ušuzzi- šatammu šatammu šatammu

witnesses bēl piqitti bēl piqitti bēl piqitti

Witnesses Arad-Innin/Balāṭsu//Nūr-Sîn Arad-Innin/Innin-aḫḫē-iddin// Arad-Innin/Ibni-Ištar//

Nanāya-aḫu-iddin/ Bēl-usātu Gimil-Nanāya

Nergal-ina-tēšê-ēṭir//Šangû-parakki Mušēzib-Bēl/Balāṭsu//Amēl-Ea Bānia/Nabû-nāṣir//Nabû-šarḫi-ili

Scribe Kināya/Zēria Balāṭu/Mušēzib-Bēl Nādin/Bēl-aḫḫē-iqīša[//E]gibi

scribe and before the same set of witnesses. The same conventional. Whichever the case, it speaks of an un-

is the case for the two documents written on the sixth usual workload for the temple’s “legal department”

of Ulūlu (TCL 12 121 and YOS 19 12). during this turbulent period.

On the other hand, three contracts of the thirtieth

of Dūzu were drafted by three different scribes before

Parties to the contracts: officials

different witnesses and yet still said to be “in the pres-

ence of ” the šatammu and bēl piqitti (see Table 2). Beaulieu noted that, in distinction from the Eanna

These documents could have been produced in the boat rentals in other years, those drafted in the sev-

course of three consecutive sittings. Alternatively, the enteenth year of Nabonidus were witnessed by the

three groups of witnesses and scribes worked side-by- temple’s high functionaries, the šatammu and bēl

side in the Eanna chancellery; in that case, the men- piqitti. This observation is also true of the four new

tion of the šatammu and the bēl piqitti was merely documents edited here, with the exception of Text 4,

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire F 203

in which the bēl piqitti is missing.14 In all the contracts, of the god).18 The Eanna temple was evidently look-

the šatammu and bēl piqitti represented the temple, ing for boats among both private and institutional

and thus their role was closer to that of contractors entrepreneurs.

than witnesses. The men who rented the boats to the temple seem

Personal supervision by top officials indicates the to have been local Urukeans (rather than men from

importance attached to these transactions by the other cities attracted by business opportunities), as

temple. The only document of the dossier from which suggested by the names characteristic of the Uruk

these officials are missing is the earliest contract, YOS onomasticon.19 They are identified by their fathers’

6 215, drafted on the twenty eighth of Dūzu; already names only, and not by the three-tier filiation char-

the next day, the šatammu and bēl piqitti were present acteristic of Babylonian urban elites. Thus, they were

at the transaction. This could mark the moment when seemingly not members of the temple staff, but rather

officials begun to supervise the rentals personally. The simple Urukeans. It is true of most individual boat

shipments could not have started much earlier. owners in these texts, as well as boatmen. Arad-Innin,

A surprising ina-ušuzzi-witness appears in Text 4, son of Marduk-iqī[ša?] of Text 2 is an exception: he

where the šatammu of the Eanna is accompanied by was a member of the influential Ḫunzû family, which

Nabû-mukīn-apli, son of Šulāya of the Šikkûa family, produced three governors of Uruk and numerous

the šatammu of the distant Ezida temple of Borsip- scribes.20

pa.15 According to the Nabonidus Chronicle, the gods Arad-Innin was not, however, the only prebendary

of Borsippa were not sent to Babylon,16 so the cultic to have engaged in the boat-rental business in this

routine of the Ezida could have gone on undisturbed, time of unrest. YOS 19 94, written at Kār-Nanāya on

and the constant presence of the šatammu in Borsippa the fifth of Abu of the seventeenth year of Nabonidus,

was not essential. Was Nabû-mukīn-apli’s visit to Uruk relates that a certain Bazūzu, son of Ibni-Ištar of the

linked to the operation the Eanna was carrying out? Gimil-Nanāya family “rented a boat in Babylon saying:

Could he have been supervising the shipments in any ‘I will deliver barley for regular offerings of the Lady

way or helping out his colleagues at Uruk? of Uruk to Babylon’.”21 The document records for-

mal proceedings carried out before the mār banê, but

since the text is damaged, the difficulties that Bazūzu

Parties to the contracts: boat-owners

encountered are regrettably unclear. It is noteworthy

and boatmen

that, six days earlier, Bazūzu’s brother Arad-Innin had

Five documents17 are third-party rentals, in which the acted as a witness to boat rental Text 3.

first party (introduced by eleppu ša PN) is the boat

owner, while the second (ina pāni PN2) is the person

Rental terms and conditions

in charge of the boat, presumably its boatman. An

unusual owner appears in YOS 19 11: the god Ea (i.e., Most contracts were to come into effect on the first

the Ea temple, presumably a local Urukean sanctuary day of the following month. Exceptions include agree-

ments concluded later, in Abu and Ulūlu: TCL 12 121

14

Beaulieu’s observation is further strengthened by the absence and possibly YOS 19 12 (to come into effect on the

of the officials in three yet-unpublished Uruk boat rentals drafted sixth day of the month), YOS 6 195 (on the tenth),

out of this period (BM 114596, BM 114610, and BM 114662). and Text 4 (on the twenty-third). TCL 12 121 is in

15

Cf. C. Waerzeggers, The Ezida Temple of Borsippa. Priesthood,

Cult, Archives, Achaemenid History 15 (Leiden, 2010), 73. The

presence of the šatammu of the Ezida in Uruk in this month is 18

For the cult of Ea in Uruk, see P.-A. Beaulieu, The Pantheon

further confirmed by TCL 12 119, a record of an investigation into of Uruk during the Neo-Babylonian Period, Cuneiform Monographs

misappropriation of temple sheep. Since the case was not linked to 23 (Leiden, 2003), 337–38.

the Ezida’s businesses in any way, it seems possible that the Ezida 19

Cf. Nanāya-ēpuš in Text 1 and TCL 12 121, Nanāya-iddin

official was asked to attend sittings of the local high body for reasons in Text 3.

of prestige. 20

H. M. Kümmel, Familie, Beruf und Amt im spätbabylonischen

16

III.11–12: dingir.meš šá bar-sip.ki gú.du8.a[.ki] u sip-par.ki Uruk. Prosopographische Untersuchungen zu Berufsgruppen des

nu ku4.meš-ni, “The gods of Borsippa, Cutha, and Sippar did not 6. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. in Uruk, ADOG 20 (Berlin, 1979), 131,

enter (Babylon)” (Grayson, ABC, 109). 139–40.

17

Frame, “Boats” no. 5; YOS 19 11; Text 1; TCL 12 121; and 21

Cf. Beaulieu, Reign of Nabonidus, 221–22, and “An Episode

YOS 19 12. in the Fall”: 245.

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

204 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

fact a re-rental: Murānu, son of Bēl-aḫḫē-erība, had The rental fees were always expressed in shekels

let his boat to the Eanna over a month earlier for the paid per month. The range is not very wide:

entire month of Abu (Text 1). The same scenario is

30 kor – 3 shekels (Frame, “Boats” no. 5)

possible also in the case of the other three contracts

120 kor – 4.5 shekels (YOS 19 12)

which came into effect later in the month: they may

150 kor – 5 shekels (YOS 6 195); 5.5 shekels

represent renewed rentals, with earlier documents

(Text 1 and TCL 12 121)

missing from the dossier at our disposal. This pos-

180 kor – 6.5 shekels (YOS 19 11)

sibility is significant, as it suggests that in reality even

200 kor – 7 shekels (Text 4)

more boats had been contracted and, consequently,

the quantities of sacrificial goods transported could Excluding the first text, the average price for shipping

have been in fact higher than calculated below. 100 kor of cargo was three-and-a-half shekels. The no-

In contrast to earlier documents, TCL 12 121 (and tably high fee in Frame, “Boats” no. 5 was presumably

possibly also YOS 19 12) was to come into effect im- linked to the relatively small size of the boat (involving

mediately, on the day it was drafted. This suggests proportionately high transport costs). No additional

that by Ulūlu the temple must have been under a lot costs (e.g., wages of crews, towers, their food rations,

of pressure. harbor dues) were ever mentioned;28 they must have

In all but one contract, the rental period was one been covered by the boatmen out of the rental fee

month.22 A boat trip from Uruk to Babylon took ap- received. These fees did not diverge from ones attested

proximately three weeks, and another seven days were in similar contracts drafted in more peaceful times,29

needed to sail back downstream.23 Thus, the boats thus, the high demand for boats in Uruk did not raise

were clearly rented for the sake of specific shipments the prices in a significant way.

only. Text 4 is the sole document in which the rental Yet another clause that appears in several docu-

period was not named, but since the rental fee was ments is mimmu ša lā X kur imaṭṭû akî kaspišu aḫāmeš

specified in a month’s term, the same provision may ippalū “Whatever (part of the boat-load) will be miss-

be assumed. ing to (the total of) X kor, they will mutually make

The carrying capacity of boats is always given by adjustment with regard to his (i.e., the boatman’s)

their load: eleppu ša x kur idekkû, “a boat that takes X- silver.”30 This ambiguous stipulation is found only in

kor (load).”24 The vessels that the Eanna rented were third-party contracts; indeed, it is not missing from

standard, ranging from 30 to 200 kor. The average any contract of this type. Its two alternative functions

capacity of a Neo-Babylonian boat fell between 100 may be considered. The clause could have provided

and 200 kor, although boats as large as 350 kor have against theft: should the boatman steal part of the

been attested.25 The quantities fit the middle-size quf- cargo, the equivalent of the missing amount would

fas used in Iraq still in the previous century: quffas be deducted from his fee. However, since no puni-

of 1.8–3 m in diameter carried loads of 3–7 tons.26 tive damages are mentioned, another possibility seems

It cannot be excluded, however, that what the Eanna more likely: the clause provides for cases in which the

rented were reed rafts, wooden mashhūfs, or plank Eanna did not dispose of the entire boat-load. Should

riverboats.27 this have happened, the rent would be proportionately

22

For year-long rentals in Uruk, see M. Weszeli, “Schiff und 28

For such costs, see G. Ries, “Miete. B. II. Neubabylonisch,“

Boot. B. In mesopotamischen Quellen des 2. und 1. Jahrtausend,” in RlA VIII (1993): 178–79.

in RlA XII (2009): 167, and BM 114610. 29

See Fr. Joannès, Textes économiques de la Babylonie récente

23

A boat with a load of 60 kor made 9–10 km a day traveling up- (Paris, 1982), 329, Frame, “Some Neo-Babylonian and Persian

stream, and 30–35 km downstream (M.-Ch. de Graeve, The Ships of Documents Involving Boats”: 33, and Ries, “Miete”: 179. Add:

the Ancient Near East [c. 2000–500 B.C.], OLA 7 [Leuven, 1981], BM 114610 (3Cyr, Uruk): six-and-a-half shekels monthly, BM

152). Uruk lies about 177 km away from Babylon. 114596 (9Cyr, Uruk): four shekels monthly; BM 114662 (1Camb,

24

Another form of description was boat width: A. Salonen, Die Borsippa): ten shekels monthly, though nowhere is the carrying

Wasserfahrzeuge in Babylonien, StOr 8.4 (Helsinki, 1939), 154–58, capacity of the boat given. Note also the divergent rents paid by

and Weszeli, “Schiff und Boot”: 162. the Eanna during an operation of sending cult statues to Babylon

25

Ibid.: 162. For the capacities of Mesopotamian boats in gen- under Nebuchadnezzar IV: three shekels (Beaulieu, “An Episode in

eral, see Salonen, Wasserfahrzeuge: 154–60. the Reign,” 21) and twelve shekels (YOS 17 302, cf. ibid., 21–22).

26

De Graeve, Ships of the Ancient Near East, 86. 30

Frame, “Boats,” no. 5, YOS 19 11; Text 1, TCL 12 121, and

27

Cf. ibid., 89–93, 107–108, and 109–22 respectively. YOS 19 12.

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire F 205

reduced. The fact that the clause appears only in third- in kor-load, while shipments could have included

party contracts is difficult to account for, but perhaps various other goods. In letters sent by the Eanna’s

boatmen did not always dispose of the entire capaci- functionaries from Babylon, requests were made for

ties of the boats under their care, but had to allow for wool,36 and animal offerings and beer should also be

shipments that boat owners contracted independently. taken into consideration. But even if the total of 100

tons does not include grain alone, this number still

gives an idea of the scale of the Eanna’s sacrificial

Shipments

economy.

With four new documents added to the dossier, the Similarly copious amounts of sacrificial products

data on quantities of sacrificial products shipped to must have been delivered to Babylon by other temples

Babylon has become quite extensive. This is especially that had followed the royal order and dispatched their

true with regard to Abu (month V), covered by eight gods. After having been presented to the gods, the of-

contracts.31 Six boats were contracted for the entire ferings were ordinarily distributed among priests and

month (the first of Abu to the first of Ulūlu), and members of the cultic personnel. Now that most of

another two were to sail out of Uruk on the tenth those entitled to the sacrificial remains stayed at home,

and the twenty third of Abu, respectively. Taking into it is difficult to resist the suspicion that by bringing the

consideration just this first coherent group of six con- gods to Babylon, Nabonidus tried to score more goals

tracts referring to the entire month of Abu, we arrive than one: to protect divine statues, to boost morale

at a surprisingly high amount of products that the among the defenders, but also to attract to the capital

Eanna sent to Babylon: these six boats were to trans- supplies necessary to hold out against a long siege—a

port a total of 890 kor, which in barley makes 160,200 siege that never took place.

liters (approximately 100,926 kilos).32 This means that

Ištar’s offerings consumed about 30 kor a day.

Urukeans in Babylon

These numbers seem very high when compared

with other data from Uruk. According to the Seleucid In his 1993 and 2014 studies, Beaulieu showed that

ritual prescriptions from Uruk TCL 6 38, merely 108 several Eanna officials followed the statue of Ištar to

sūtu (about 648 l, or 408 kg) of barley and emmer Babylon. They escorted the statue to the capital, took

were spent daily on the ginû-offerings of all Urukean care of the daily needs of the goddess and oversaw reg-

gods.33 The Seleucid Rēš temple was, however, con- ular deliveries of sacrificial goods from Uruk. Among

siderably smaller and less important than the Neo- these officials were supervisors of the temple’s two

Babylonian Eanna. Moreover, one should add to the most important prebendary groups (bakers and brew-

ginû the grain spent during festivals; the amounts ers), trustees (qīpānu), and the chief rent farmer.37 As

were usually significant. Stefan Zawadzki has calcu- follows from Text 4, officials tended to travel: the su-

lated that the Ebabbar spent a monthly average of 20 pervisor of bakers, Lâbāši-Marduk, formerly in Baby-

large kor (about 4,300 liters) of barley on the šalam lon, was in Uruk in the end of Abu. The text published

bīti ceremony alone.34 An Uruk text OIP 122 82 men- below (see Fig. 5) demonstrates that the movement

tions a yearly issue of as much as 350 kor of barley for of functionaries between Uruk and Babylon in this

the same purpose in Uruk.35 period was even more dynamic.

The calculation of the amount of grain sent to

Text 5. BM 114477 (1920-6-15, 73). 5.7 cm × 3.9 cm

Babylon from Uruk is burdened by the fact that

boat capacity may have been conventionally given 1. [x+]3 gur zú.lum.ma i-mit-ti a.šà

2. ⸢šá⸣ i7-šá-mdidim-šeš.meš-gi

31

YOS 6 215; Frame, “Boats” no. 5; YOS 19 11; Text 1; Text 2; 3. ⸢níg⸣.ga dgašan šá unug.ki u dna-na-a (erasure)

Text 3; YOS 6 195; and Text 4. 4. ⸢šá⸣ giš.bán šá mkal-ba-a a-šú šá mba-šá

32

One litre of barley weighs ca. 0.63 kg. 5. ⸢a⸣ mba-si-ía šá ina muḫ-ḫi giš.bán

33

Cf. M. J. H. Linssen, The Cults of Uruk and Babylon: The 6. ⸢šá⸣ dgašan šá unug.ki ina muḫ-ḫi mdnà-šeš.meš-gi

Temple Ritual Texts as Evidence for Hellenistic Cult Practice, Cune-

7. a!-šú šá mdù-dinnin a lú.gal.dù <<aš>>

iform Monographs 25 (Leiden, 2004), 134.

34

S. Zawadzki, Neo-Babylonian Documents from Sippar Pertain-

ing to the Cult (Poznań, 2013), 34. 36

Beaulieu, “An Episode in the Fall”: 249–50.

35

Including malītu-income (cf. ibid.). 37

Ibid.: 247–49, 251, and “An Episode in the Reign,” 19–20.

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

206 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

aḫḫē-šullim/Ibni-Ištar//Rab-banê and Arad-Bēl/

Aḫušunu. They will deliver (the dates) in the month

of Tašrītu.

Apart from ten kor of dates from the Brook of Sîn-

māgir that are at the disposal of Nabû-aḫḫē-šullim.

Witnesses: Innin-šumu-ibni/Nabû-bēlšunu.

Scribe: Itti-Šamaš-balāṭu/Nabû-šumu-ukīn.

Babylon, the fourth of Tašrītu, seventeenth year of

Nabonidus, king of Babylon.

One of the parties to the contract was Kalbāya, son

of Iqīšāya, one of the Eanna’s rent farmers (ša muḫḫi

sūti). Entrepreneurs like him rented large tracts of

institutional farmland in exchange for a fixed amount

of agricultural products. They then divided the land

into smaller plots that they sublet to petty business-

men or farmers.38 Nabû-aḫḫē-šullim, son of Ibni-

Ištar, and Arad-Bēl, son of Aḫušunu, must have been

a sub-renter of this sort, about whom, unfortunately,

there is nothing known otherwise. Further, neither

canal mentioned in the text (Nāru-ša-Ea-aḫḫē-šullim,

Ḫarru-ša-Sîn-māgir) has been attested in the hitherto

published Uruk texts.39

The rent farmer Kalbāya, on the other hand, is very

well known.40 He was a man of high standing with close

ties to the king himself. He and his uncle Šumu-ukīn

Figure 5—BM 114477 (Text 5) (a former rent farmer of many years) contracted the

Eanna’s farmland from Nabonidus himself (rather than

through the temple authorities) in the first year of the

l.e. king’s rule.41 Nabonidus personally defended Kalbāya

8. u mìr-den a-šú šá mšeš-šú-nu before the temple officials when arrears mounted up

9. ina iti.du6 i-nam-din-u’ and the rent farmer was unable to meet them.42

Text 5 is a common promissory note for the rent

rev. due from a sublet date grove. Its uniqueness lies in the

10. e-lat 10 gur zú.lum.ma šá ḫar-ri

11. šá lú.sin-ma-gir šá ina igi mdnà-šeš.meš-gi 38

For a convenient survey of this institution, see M. Jursa, As-

12. lú.mu-kin7 mdinnin.na-mu(over erasure)-dù pects of the Economic History of Babylonia in the First Millennium

BC. Economic Geography, Economic Mentalities, Agriculture, the Use

13. a-šú šá mdnà-⸢en⸣-šú-nu

of Money and the Problem of Economic Growth (with contributions by

14. u lú.umbisag mki-dutu-tin a-šú J. Hackl [et al.]), AOAT 377 (Münster, 2010), 194–206.

15. šá mdnà-mu-gin tin.tir.ki 39

The latter is clearly different from Nār-Sîn-māgir known from

16. iti.du6 u4.4.kám mu.17.kám Nippur sources (R. Zadok, Geographical Names According to New-

and Late-Babylonian Texts, RGTC 8 [Wiesbaden, 1985], 382).

u.e. 40

Cf. D. Cocquerillat, Palmeraies et cultures de l’Eanna d’Uruk

(559–520), ADFU 8 (Berlin, 1968), 38–39, 93–97; Kümmel,

17. md

nà-i lugal tin.tir.ki

Familie, Beruf und Amt, 105–106; Beaulieu, Reign of Nabonidus,

[x+]3 kor of dates, the estimated rent of the field on 117–18; and Kleber, Tempel und Palast, 54–56.

41

Cocquerillat, Palmeraies et cultures, 38; Beaulieu, Reign of

the Canal of Ea-aḫḫē-šullim, property of the Lady of

Nabonidus, 117–18.

Uruk and Nanāya that belongs to the rent farm of 42

YOS 3 2, a letter warning the Eanna functionaries to stay away

Kalbāya/Iqīšāya//Basia, the rent farmer of the Lady from Kalbāya, is dated between the fourteenth and the sixteenth

of Uruk, is due from the (sub-)rented land of Nabû- year of Nabonidus (Kleber, Tempel und Palast, 55–56).

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire F 207

fact that it was drafted in or around Babylon rather witnesses together. This single witness is Innin-šumu-

than in Uruk. Furthermore, it was written only twelve ibni, a long-term agent of the Eanna based in the

days before the city was taken by the Persians. Tašrītu capital. He is attested as early as in the second year

was a month when the date harvest was estimated, of Neriglissar, handling silver brought to Babylon by

hence it would not be surprising to find the Eanna the qīpu of the Eanna for various purchases.45 In the

temple’s chief rent farmer traveling in the countryside, eighth year of Nabonidus, he bought gold for the

supervising fields under his care. It is certainly unusual, Eanna, again with silver sent from Uruk.46 However,

however, that he reached as far north as Babylon. His his main duty seems to have been supervising the Ean-

presence in the capital can hardly be treated apart from na’s granary in the capital. YOS 19 225 records the

the circumstances of time. receipt of “ten shekels of silver for the food rations of

It is possible to track the rent farmer’s journey to Innin-šumu-ibni, son of Nabû-bēlšunu who will guard

Babylon. In Text 5, Kalbāya is accompanied by the the storage area (bīt karam) of barley in Babylon.”47

scribe Itti-Šamaš-balāṭu, son of Nabû-šumu-ukīn. In YOS 3 140, a letter sent from Babylon to temple

Both men appear together in YOS 6 207, a document scribes, Innin-šumu-ibni wrote:

drafted in Maškānu on—according to Dougherty’s 8

20 mu.an.na-àm en.nun 9ina kar-am ki-i aṣ-

copy—the first of Dūzu of the seventeenth year of

ṣu-ru 10mim-ma šá l[a na-ṣa]-ri ina lìb-bi 11ul

Nabonidus. The month iti.šu (Dūzu) is distinguished

i[n]-né-pu-⸢uš⸣ en-na 12mdna-na-a-dù-⸢uš kar-

from iti.du6 (Tašrītu) by a single vertical wedge only,

am⸣ 13ki-i ip-tu š[e.bar] 14ul-tu lìb-bi i[t-ta]-ši

and thus the two signs are easily confused, whether by

scribe or copyist. A collation kindly made by Elizabeth For twenty years when I have guarded the storage

Payne confirms that Tašrītu is plausible and possible.43 area, no negligence in the guarding duties has

If the proposed reading is correct, Kalbāya and Itti- ever taken place. Now Nanāya-⸢ēpuš⸣ opened the

Šamaš-balāṭu were in Maškānu three days before Text storage area and took b[arley?] from there.

5 was drafted. Both men appear further in Joannès

One can only speculate on what exactly brought

Textes économiques 42 written in [Bīt]-bārî, a šīḫu-

Kalbāya to the capital. The Basia family originally came

domain of the Lady-of-Uruk. The date of this docu-

from Babylon,48 and he could have simply returned to

ment is damaged, but year 10+[x] of Nabonidus is

his hometown and family in view of the approaching

mentioned in the text; thus, Nabonidus’s seventeenth

danger. It seems much more likely, however, that the

year cannot be excluded. Moreover, both YOS 6 207

trip was linked to Kalbāya’s function as ša muḫḫi sūti.

and Joannès Textes économiques 42 record identical

The Eanna urgently needed agricultural products, and

transactions: the receipt of slaves in lieu of outstand-

the uncertainty regarding the future must have made

ing dues in barley owed to the Eanna.44 Thus one can

its officials press the temple debtors harder. The fact

speculate as to the route taken by Kalbāya and the

that Kalbāya continued to exercise his duties and the

scribe who assisted him: they probably left from Uruk,

presence of the Eanna’s agent strengthen the latter

passed through Bīt-bārî (Joannès Textes économiques

possibility. It is further noteworthy that during the

42) and Maškānu (YOS 6 207), to arrive finally in

uprisings against Darius I, the then-chief rent farmer

Babylon (Text 5). On the way, Kalbāya attended to

Gimillu was actively involved in the operation to bring

his duties as rent farmer.

the Lady-of-Uruk to the capital: together with his

Text 5 was witnessed by one man only; apparently

there was no time or no need to put a larger body of

45

Joannès Textes économiques 60: 15 lists three minas of silver

43

E. Payne communicates: “There is a bit of damage on the taken by him out of the silver brought to Babylon by the qīpu of

left of the month name, precisely where the small vertical wedge the Eanna.

distinguishing du6 from šu would be. Within this damage, however, 46

YOS 6 112: 15.

there is a small tick-mark. While this tick could be additional dam- 47 10

10 gín kù.⸢babbar⸣ a-na kurum.ḫi.a 11šá mdin-n[in]-mu-dù a

age, it could also be traces of the head of the vertical wedge. Given md

nà-en-šú-nu 12šá é ka-⸢ra-am⸣ šá še.bar ina tin.tir.ki 13i-nam-ṣa-ru

this, reading the month name as Tašrītu is entirely possible. It is not (14.12.2 Nbn). The Eanna’s (bīt) karam in Babylon is mentioned

absolutely certain, but it is certainly possible.” also in YOS 7 99: 1, 7 (0Camb).

44

One more similar transaction is recorded in Joannès Textes 48

Cf. M. Jursa, Neo-Babylonian Legal and Administrative Docu-

économiques 41 written in the tenth year of Nabonidus and drafted ments: Typology, Contents and Archives, GMTR 1 (Münster, 2005),

by another scribe. 141.

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

208 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

people, he was in charge of safeguarding the divine

statue on its way to Babylon.49

Boats for the Ebabbar

The Nabonidus Chronicle states explicitly that the

northern centers of Borsippa, Cutha, and Sippar did

not send their gods to Babylon.50 Various reasons for

this decision have been considered, among them the

opposition to Nabonidus in the priestly circles of these

cities, and various other political and military causes.51

Yet, as shown by Zawadzki, Sippar did take steps to

provide security for the statues of its satellite centers.52

In the very beginning of Ulūlu (VI), temple authori-

ties arranged for the transfer to the capital of the statue

of Bēl-ṣarbi of Šapaṣṣu (Baṣ), a small town that lay in

Sippar’s sphere of influence. Zawadzki considered the

dispatch of the Baṣ statue a possible gesture of good

will of the authorities seeking to show their obedience

towards the king.

Further evidence suggests that Sippar authorities

might have been less reluctant to follow the royal

order than has been previously assumed. Two texts

edited below (Text 6 [see Figure 6] and CT 55 191)

show that the Ebabbar sought to secure boat trans-

port just before the coming of the Persians. The doc-

uments cannot be confidently linked to an operation

similar to the one carried out by the Eanna, but such

a context seems very probable in view of the fact that Figure 6—BM 63873 (Text 6)

the contracts were drafted only a few days before the

city was taken by the Persians on the fourteenth of l.e.

Tašrītu. By the point at which the contracts were

7. šá giš.má i-pa-ṭar-ri

concluded, the news of the battle of Opis, in which

Cyrus defeated the Babylonian army, must have al- 8. giš.má ina igi dutu

ready reached Sippar. rev.

Text 6. BM 63873 (82-9-18, 3841) Bertin 1633. 9. lú.mu-kin-nu mdnà-sur a-šú

4.7 cm × 3.4 cm 10. šá m⸢ìr⸣-dnà a mìr-didim

11. mdutu-mu-giš a-šú šá

1. 3½ gín kù.babbar i-di ⸢giš.má-šú⸣ šá

12. mre-mut lú.dub.sar

2. mda-ad (over erasure)-di (over erasure)-i’-ia lú.qal-la

13. mmu-dnà a-šú šá mdutu-sig15

3. šá mdutu-lugal-⸢ùru⸣ ina šuii

14. a lú.sanga dutu sip-par.ki

4. mdutu-sig15 u mden-gi

15. ⸢iti⸣.du6 u4.9.kám mu.⸢17⸣.kám

5. ki-i pi-i iti 10½ gín kù.babbar

6. ma-ḫi-ir ta ugu u4-mu u.e.

49

Beaulieu, “An Episode in the Reign,” 19–20. 16. [mdn]à-i lugal e.ki

50

Cf. n. 16 above.

Three-and-a-half shekels of silver, the rent of his boat,

51

See Beaulieu, Reign of Nabonidus, 223–24, and Zawadzki,

“End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire”: 51 nn. 15–16, for references

has been received by Daddīʾa, the slave of Šamaš-šar-

to theories of S. Smith, A. T. Olmstead, and M. Weinfeld. uṣur, from Šamaš-udammiq and Bēl-ušallim. In accor-

52

Ibid.: 49–52. dance with the monthly rate of ten-and-a-half shekels.

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

More on the End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire F 209

From the day he releases the boat, the boat will be at paid by two contractors. The clause stating that the

the disposal of Šamaš. boats will be “at the disposal of Šamaš” leaves no

doubt that the contracting party was the Ebabbar.

Witnesses: Nabû-ēṭir/Arad-Nabû//Arad-Ea,

The choice of the formulation ina pāni Šamaš over

Šamaš-šumu-līšir/Rēmūt.

the expected ina pāni PN (“is at the disposal of PN [a

Scribe: Iddin-Nabû/Šamaš-udammiq//

temple official]”) or ana idi ana Ebabbar iddin (“he

Šangû-Šamaš.

rented to the Ebabbar”), seems to emphasize the fact

Sippar, the ninth of Tašrītu, seventeenth year of Na-

that the boat would serve the god himself and not

bonidus, king of Babylon.

plain administrative purposes.54

CT 55 191 (BM 55705) The two men who paid the rent, Šamaš-udammiq

and Bēl-ušallim, must have been temple officials. Their

1. 6 (erasure53) gín kù.babbar i-di giš.má-šú

filiation was not given in either text, which must in-

2. šá 15.kám u4-mu.meš mdnà-numun-gál-ši

dicate that they were known figures whose identity

3. a-šú šá mre-mut ina šuII

did not have to be specified. Both texts were drafted

4. mdutu-sig15 u mden-gi

by the same scribe, who was possibly the son of the

5. ma-ḫi-ir ki-i pi-i iti 11 gín kù.babbar

first functionary. Should this assumption prove true,

6. ta ugu u4-mu šá giš.má

the official must be identical with Šamaš-udammiq/

l.e. Šūzubu//Šangû-Šamaš,55 possibly a royal merchant.

He is attested receiving silver for the purchase of sheep

7. i-pa-ṭar-ri giš.má

(CT 57 149: 2, 41Nbk; Nbn. 1130: 5, [x]Nbn),

8. ina igi dutu

luxury garments (BM 60866: 4, 6Nbn), agricultural

rev. products (CT 57 147: 9, 1AM), and rations due to

9. lú.mu-kin-nu mdutu-tin-iṭ royal merchands (Nbn. 464: 3, 10Nbn). The identity

10. a-šú šá mgi-mil-lu of his partner Bēl-ušallim is more difficult to establish.

11. mdutu-mu a-šú šá ma-ra-bi The documents vary in further details from those

12. lú.umbisag mmu-dnà a-šú drafted by Eanna scribes. The rental periods in Text 6

13. šá mdutu-sig15 a lú.sanga dutu and CT 55 191 are ten and fifteen days, respectively

14. sip-par.ki iti.du6 u4.10.kám (rather than an entire month), presumably because

15. mu!(text: u4).17.kám mdnà-i the place the boat was to reach was located not far

away. During this time, a return trip from Sippar to

u.e. Babylon (60 km) could easily have been completed,

16. lugal e.ki thus the rental period makes the capital (rather than,

e.g., Uruk) a plausible destination.

Six shekels of silver, the rent of his boat for fifteen days, The rents charged in the two texts are twice as high

has been received by Nabû-zēru-šubši/Rēmūt from as those from Uruk. The capacities of the vessels the

Šamaš-udammiq and Bēl-ušallim. In accordance with Ebabbar contracted are unknown: they could have

the monthly rate of eleven shekels of silver. been larger than those rented by the Eanna. Another

From the day he releases the boat, the boat will be at possible reason for this discrepancy is that boat rents

the disposal of Šamaš. in Sippar seem to have been generally higher than in

the provincial south.56 Lastly, rents could have gone up

Witnesses: Šamaš-uballiṭ/Gimillu,

Šamaš-iddin/Arrabi.

Scribe: Iddin-Nabû/Šamaš-udammiq//

54

Suggestion courtesy S. Zawadzki.

55

Bongenaar, The Neo-Babylonian Ebabbar Temple at Sippar: Its

Šangû-Šamaš.

Administration and its Prosopography, PIHANS 80 (Leiden, 1997),

Sippar, the tenth of Tašrītu, seventeenth year of Na- 456.

bonidus, king of Babylon. 56

CT 57 79 (14Nbn) mentions a boat rented for ten shekels

and an additional two shekels paid as the boatman’s fee. A similar

These two texts differ formulaically from the Eanna rate is attested in BM 66816, in which thirty shekels were paid as a

contracts. They are shaped as receipts for boat rent two-month rent. In CT 57 87 the rent is only two shekels, but the

boat was to bring a shipment from nearby Gilūšu. The silver was

53

Traces of ½ are visible under this erasure. issued on the 7.7.17Nbn, thus, just before the discussed boats were

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

210 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

due to ongoing military actions, circumstances under hypothesis, the boat rentals could then have been part

which people may have been ready to pay any amount of of arrangements made by the Ebabbar authorities im-

money in order to save themselves and their possessions. mediately after the feast. The rapid approach of the

The purpose of renting the boats has not been Persian army might have then obstructed the final

named in the documents, but with Uruk rentals in dispatch of the gods.

mind, one is tempted to speculate that the Ebabbar This scenario remains conjectural until conclusive

was aiming to dispatch a cargo to Babylon: the divine evidence turns up. If true, however, the Chronicle

statues, their paraphernalia or other temple valuables, entry mentioning that the three northern cities did

and perhaps also accompanying personnel. According not send their gods to Babylon should not be un-

to a scenario offered by Zawadzki, Sippar authori- derstood as critical of Nabonidus.58 Rather, it would

ties did not choose to keep their gods at home, but state the simple fact that, for various reasons, the

merely delayed the dispatch, e.g., until the feast of gods of Borsippa, Sippar, and Cutha did not make

the seventh of Tašrītu (VII), during which the divine it to the capital before Cyrus and his army knocked

statues had to be present in Sippar.57 Building on this at their doors.

contracted; however, due to formulaic differences, this transaction

has to be treated separately.

57

Zawadzki, “End of the Neo-Babylonian Empire”: 51, cf.

A. Cavigneaux and V. Donbaz, “Le mythe du 7.VII. Les jours fa- 58

As suggested by S. Smith, A. T. Olmstead, and M. Weinfeld

tidiques et le Kippour mésopotamiens,” OrNS 76 (2007): 293–335. (see references in n. 51).

This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Thu, 15 Oct 2015 14:35:48 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Mooney Itec 7600 Plan For Implementing Personalized LearningDocument12 pagesMooney Itec 7600 Plan For Implementing Personalized Learningapi-726949835No ratings yet

- Shu Jing IntralinearDocument498 pagesShu Jing Intralinearparaibologo100% (1)

- The Neo Babylonian Chronicle SeriesDocument24 pagesThe Neo Babylonian Chronicle Seriesromario sanchez100% (1)

- Judah and The Judeans in The Neo-Babylonian PeriodDocument625 pagesJudah and The Judeans in The Neo-Babylonian PeriodDAVIDSERGIO39946100% (3)

- A.H.sayce Religion of The Ancient BabyloniansDocument564 pagesA.H.sayce Religion of The Ancient BabyloniansSanskrit InstituteNo ratings yet

- Journal of The American Oriental Society Volume 117 Issue 2 1997 (Doi 10.2307/605488) Dov Gera and Wayne Horowitz - Antiochus IV in Life and Death - Evidence From The Babylonian Astronomical DiariesDocument14 pagesJournal of The American Oriental Society Volume 117 Issue 2 1997 (Doi 10.2307/605488) Dov Gera and Wayne Horowitz - Antiochus IV in Life and Death - Evidence From The Babylonian Astronomical DiariesNițceValiNo ratings yet

- How Bad Was The Babylonian Exile - Biblical Archaeology SocietyDocument4 pagesHow Bad Was The Babylonian Exile - Biblical Archaeology SocietyWilliam .williamsNo ratings yet

- Neo Babylonean EmpireDocument40 pagesNeo Babylonean EmpirekhadijabugtiNo ratings yet

- Quaker Oats & SnappleDocument5 pagesQuaker Oats & SnappleemmafaveNo ratings yet

- The Cult of AN - SAR Assur in Babylonia. After The Fall of The Assyrian Empire (1997)Document20 pagesThe Cult of AN - SAR Assur in Babylonia. After The Fall of The Assyrian Empire (1997)Keung Jae LeeNo ratings yet

- Christian OBrien and Zecharia SitchinDocument12 pagesChristian OBrien and Zecharia SitchinGraham CoupeNo ratings yet

- A Thousand Years of Philippine History Before The Coming of The Spaniards - TextDocument28 pagesA Thousand Years of Philippine History Before The Coming of The Spaniards - TextJakobMagbanuaNo ratings yet

- Origin of Pagan IdolatryDocument544 pagesOrigin of Pagan IdolatrySohrab100% (3)

- Zoroastrianism Among The KushansDocument46 pagesZoroastrianism Among The KushansszalerpNo ratings yet

- Leeman THE SABAEAN INSCRIPTIONS AT ADI KAWEH PDFDocument34 pagesLeeman THE SABAEAN INSCRIPTIONS AT ADI KAWEH PDFseeallconcernNo ratings yet

- 48417CCJDocument24 pages48417CCJCarmeloPappalardoNo ratings yet

- El Cilindro de BorsippaDocument17 pagesEl Cilindro de BorsippaWalter HerreraNo ratings yet

- The Spoils of The Jerusalem Temple at Rome and ConstantinopleDocument25 pagesThe Spoils of The Jerusalem Temple at Rome and ConstantinopleAnonymous r57d0G100% (2)

- The Sabaean Inscriptions at Adi Kaweh - Bernard LeemanDocument34 pagesThe Sabaean Inscriptions at Adi Kaweh - Bernard LeemanBntleeman67% (3)

- The Babylonian Story of the Deluge as Told by Assyrian Tablets from Nineveh The Discovery of the Tablets at Nineveh by Layard, Rassam and SmithFrom EverandThe Babylonian Story of the Deluge as Told by Assyrian Tablets from Nineveh The Discovery of the Tablets at Nineveh by Layard, Rassam and SmithNo ratings yet

- Dionysus or Liber Pater The Evidence of PDFDocument20 pagesDionysus or Liber Pater The Evidence of PDFVesna MatićNo ratings yet

- The New Year Ceremonies in Ancient BabylDocument21 pagesThe New Year Ceremonies in Ancient BabylNaim BaşodacıNo ratings yet

- Cyrus - Edict of Cyrus - Sstark - 230paper3Document9 pagesCyrus - Edict of Cyrus - Sstark - 230paper3SandraNo ratings yet

- The Length of Reigns of The Neobabylonian KingsDocument64 pagesThe Length of Reigns of The Neobabylonian KingsRaul Antonio Meza JoyaNo ratings yet

- 10.1515 - Janeh 2019 0003Document26 pages10.1515 - Janeh 2019 0003maskedwrit3rNo ratings yet

- Classical Association of Canada Phoenix: This Content Downloaded From 193.231.9.1 On Fri, 21 Apr 2017 14:08:16 UTCDocument16 pagesClassical Association of Canada Phoenix: This Content Downloaded From 193.231.9.1 On Fri, 21 Apr 2017 14:08:16 UTCPlat LapNo ratings yet

- Babylonian-Assyrian Religion, Part Of, Jastrow 1898Document16 pagesBabylonian-Assyrian Religion, Part Of, Jastrow 1898shayfaranasNo ratings yet

- Adams - WY - Architectural Evolution of The Nubian Church, 500-1400Document54 pagesAdams - WY - Architectural Evolution of The Nubian Church, 500-1400audubelaiaNo ratings yet

- Nebopolassar and The Temple To The Sun-God at SipparDocument21 pagesNebopolassar and The Temple To The Sun-God at SipparGabrielbotelho45No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 3.0.220.147 On Sun, 09 Apr 2023 08:50:17 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 3.0.220.147 On Sun, 09 Apr 2023 08:50:17 UTCT ZNo ratings yet

- Traces of The Lost 10 Tribes of Israel IDocument47 pagesTraces of The Lost 10 Tribes of Israel IvincetualjinnNo ratings yet

- The Ezida Temple of Borsippa PriesthoodDocument12 pagesThe Ezida Temple of Borsippa PriesthoodMah FudNo ratings yet

- Rebuilding the Temple at Jerusalem: The Persian Empire's Influence In The Rebuilding Of JerusalemFrom EverandRebuilding the Temple at Jerusalem: The Persian Empire's Influence In The Rebuilding Of JerusalemNo ratings yet

- Lin Ying 2007 Fulin Monks POC 57 (2007) 24-42Document10 pagesLin Ying 2007 Fulin Monks POC 57 (2007) 24-42高橋 英海No ratings yet

- Byblos Inscriptions PaperDocument20 pagesByblos Inscriptions PaperdanielandmarieNo ratings yet

- (1921) The Early Dynasties of Sumer and Akkad by Cyril John Gadd (1893-)Document64 pages(1921) The Early Dynasties of Sumer and Akkad by Cyril John Gadd (1893-)Herbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (2)

- Ezra NehemiahDocument147 pagesEzra NehemiahHerbert Adam Storck100% (3)

- The Babylonian Story of The Deluge As Told by Assyrian Tablets From Nineveh by Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1857-1934Document70 pagesThe Babylonian Story of The Deluge As Told by Assyrian Tablets From Nineveh by Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1857-1934Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Egyptian Pyramids - Connection To Rain and Nile Flood AnmoliesDocument20 pagesThe Egyptian Pyramids - Connection To Rain and Nile Flood AnmoliesKonstantin BorisovNo ratings yet

- Rapid #: - 12485786: 877606 GZM:: Memorial Library BXM:: Main LibraryDocument30 pagesRapid #: - 12485786: 877606 GZM:: Memorial Library BXM:: Main LibraryCássia RenataNo ratings yet

- BabiloniaDocument124 pagesBabiloniaSergio AndrésNo ratings yet

- Apocryphal Book of BaruchDocument19 pagesApocryphal Book of BaruchMerveNo ratings yet

- Epigraphic Evidence From The Dakhleh Oasis in The Libyan Period PDFDocument15 pagesEpigraphic Evidence From The Dakhleh Oasis in The Libyan Period PDFAksël Ind'gzulNo ratings yet

- Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol 4 Excavation ReportDocument3 pagesKhirbet Qeiyafa Vol 4 Excavation ReportHans KristensenNo ratings yet

- J. W. McKay (1970) - Helel and The Dawn-Goddess. A Re-Examination of The Myth in Isaiah XIV 12-15. Vetus Testamentum 20.4, Pp. 451-464Document15 pagesJ. W. McKay (1970) - Helel and The Dawn-Goddess. A Re-Examination of The Myth in Isaiah XIV 12-15. Vetus Testamentum 20.4, Pp. 451-464OLEStarNo ratings yet

- The Alosaka Cult of The Hopi Indians by J Walter FewkesDocument34 pagesThe Alosaka Cult of The Hopi Indians by J Walter Fewkesadina100% (1)

- 1930 - CONFUCIUS - Crises in The Life of The Chinese SageDocument10 pages1930 - CONFUCIUS - Crises in The Life of The Chinese SageAssess GlobalNo ratings yet

- Israel's Settlement in Canaan: The Biblical Tradition and Its Historical Background, C.F. Burney, Schweich Lectures, 1917Document134 pagesIsrael's Settlement in Canaan: The Biblical Tradition and Its Historical Background, C.F. Burney, Schweich Lectures, 1917David Bailey100% (3)

- Babl Paper JocDocument14 pagesBabl Paper Jocken_griffith_4No ratings yet

- The Tabernacle, CaldecottDocument282 pagesThe Tabernacle, CaldecottDavid BaileyNo ratings yet

- (15685330 - Vetus Testamentum) Elusive Scrolls Could Any Hebrew Literature Have Been Written Prior To The Eighth Century BceDocument39 pages(15685330 - Vetus Testamentum) Elusive Scrolls Could Any Hebrew Literature Have Been Written Prior To The Eighth Century BceemmaNo ratings yet

- Ukraine in Bible Prophecy and End Time Events A Biblical Case For Ukrainian Involvement in The Latter Day Invasion of Israel Before Christ ReturnsDocument3 pagesUkraine in Bible Prophecy and End Time Events A Biblical Case For Ukrainian Involvement in The Latter Day Invasion of Israel Before Christ ReturnsDuncan Heaster100% (1)

- Current Science Association Current Science: This Content Downloaded From 61.3.61.242 On Sat, 24 Jul 2021 11:00:13 UTCDocument5 pagesCurrent Science Association Current Science: This Content Downloaded From 61.3.61.242 On Sat, 24 Jul 2021 11:00:13 UTCtelugutalliNo ratings yet

- Current Science Association Current Science: This Content Downloaded From 61.3.61.242 On Sat, 24 Jul 2021 11:00:13 UTCDocument5 pagesCurrent Science Association Current Science: This Content Downloaded From 61.3.61.242 On Sat, 24 Jul 2021 11:00:13 UTCtelugutalliNo ratings yet

- PG 70346Document22 pagesPG 70346XCrawlNo ratings yet

- Judah in The Neo-Babylonian PeriodDocument34 pagesJudah in The Neo-Babylonian PeriodJustin SingletonNo ratings yet

- Confucianism by Dorothy Hoobler and Thomas HooblerDocument43 pagesConfucianism by Dorothy Hoobler and Thomas HooblerPrachi TomarNo ratings yet

- Bethlehem CompleteDocument142 pagesBethlehem CompleteintiwisekingpNo ratings yet

- Natalie Naomi May - Portable Sanctuaries and Their Evolution - The Biblical Tabernacle and The Akkadian QersuDocument32 pagesNatalie Naomi May - Portable Sanctuaries and Their Evolution - The Biblical Tabernacle and The Akkadian QersuExequiel MedinaNo ratings yet

- What Happened at Piprahwa3Document23 pagesWhat Happened at Piprahwa3Stephanie Angngoching100% (1)

- 541 BC SardesDocument23 pages541 BC Sardesromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Mobilisation and Militarisation in The NDocument11 pagesMobilisation and Militarisation in The Nromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurs and Empire: Pihans - LivDocument343 pagesEntrepreneurs and Empire: Pihans - Livromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Bibliotecas de BabelDocument39 pagesBibliotecas de Babelromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- 1916, The Year Babylon Got Into Hollywood: An Historical Analysis of David W. Griffith's IntoleranceDocument24 pages1916, The Year Babylon Got Into Hollywood: An Historical Analysis of David W. Griffith's Intoleranceromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Fuentes Bíblicas Sobre BabiloniaDocument55 pagesFuentes Bíblicas Sobre Babiloniaromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Excavaciones en BabiloniaSin Título 02Document76 pagesExcavaciones en BabiloniaSin Título 02romario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Babilonia MedievalDocument44 pagesBabilonia Medievalromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Brewer - Adad GuppiDocument4 pagesBrewer - Adad Guppiromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Dupont Global PV Reliability: 2018 Field AnalysisDocument6 pagesDupont Global PV Reliability: 2018 Field AnalysissanNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 - Inventions and Technologies PDFDocument5 pagesUnit 4 - Inventions and Technologies PDFТимур выфыфNo ratings yet

- Real Numbers 40 Marks Test PaperDocument4 pagesReal Numbers 40 Marks Test Paperdinesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Shapes of The NailDocument23 pagesShapes of The NailJESSICA B. SUMILLERNo ratings yet

- Taussig - An Australian HeroDocument24 pagesTaussig - An Australian HeroasabiyahNo ratings yet

- Investigation of Small Dams Failures in Seasonal/Intermittent Streams: Unpublished PapersDocument33 pagesInvestigation of Small Dams Failures in Seasonal/Intermittent Streams: Unpublished Papersוויסאם חטארNo ratings yet

- Rindova & Martins 2023 Strsci - Moral Imagination and Strategic PurposeDocument13 pagesRindova & Martins 2023 Strsci - Moral Imagination and Strategic PurposercouchNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MgnregaDocument7 pagesIntroduction To MgnregaBabagouda Patil100% (1)

- 1 - Hassanpour Et Al., 2011. Plants and Secondary Metabolites (Tannins) A ReviewDocument7 pages1 - Hassanpour Et Al., 2011. Plants and Secondary Metabolites (Tannins) A ReviewFelipe Reyes PeñaililloNo ratings yet

- Health Teaching PlanDocument3 pagesHealth Teaching PlanEden LacsonNo ratings yet

- C955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Document3 pagesC955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Robert Allen Rippey0% (1)

- Importance of IqDocument4 pagesImportance of Iqmark ignacioNo ratings yet

- Exercises: Do You WantDocument1 pageExercises: Do You WantChan Myae Ko100% (1)

- Elecciones Injustas, Una Cronología de Incidentes No Democráticos Desde 1999. Por Vladimir Chelminski (No Publicado)Document124 pagesElecciones Injustas, Una Cronología de Incidentes No Democráticos Desde 1999. Por Vladimir Chelminski (No Publicado)AgusGulman100% (1)

- The Worst Day of My LifeDocument6 pagesThe Worst Day of My LifejoannaNo ratings yet

- Al Capone Biography - TTC 2023Document1 pageAl Capone Biography - TTC 2023Jerónimo CervellóNo ratings yet

- SR-OPL023 - MD04 - Display Stock Requirements ListDocument3 pagesSR-OPL023 - MD04 - Display Stock Requirements Listduran_jxcsNo ratings yet

- Pareto Dan Pasif KF HBJ 24 Maret 2022Document116 pagesPareto Dan Pasif KF HBJ 24 Maret 2022Indah C. KadullahNo ratings yet

- ContinueDocument3 pagesContinueNeeraj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Gererac Guardián 7.5 KWDocument52 pagesGererac Guardián 7.5 KWOPERACIONES TORRESANo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Deformable Bodies: Mapúa Institute of TechnologyDocument16 pagesMechanics of Deformable Bodies: Mapúa Institute of TechnologyAhsan AliNo ratings yet

- ResumeDocument1 pageResumeBecca SmartNo ratings yet

- Concept of LeadershipDocument142 pagesConcept of Leadershipv_sasivardhini100% (1)

- The New House of Money - Chapter 2 - Jim ChanosDocument35 pagesThe New House of Money - Chapter 2 - Jim ChanosZerohedge100% (2)

- Growth and Linkage of The East Tanka FauDocument14 pagesGrowth and Linkage of The East Tanka FauJoshua NañarNo ratings yet

- Pedodontic Lect 20-21Document8 pagesPedodontic Lect 20-21كوثر علي عدنان حسينNo ratings yet

- Jozef KronerDocument2 pagesJozef KronerAryan KhannaNo ratings yet