Professional Documents

Culture Documents

We Do Need A Philosophy of Library and Information Science - We're Not Confused Enough - A Response To Zwadlo

We Do Need A Philosophy of Library and Information Science - We're Not Confused Enough - A Response To Zwadlo

Uploaded by

3x4 ArchitectureOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

We Do Need A Philosophy of Library and Information Science - We're Not Confused Enough - A Response To Zwadlo

We Do Need A Philosophy of Library and Information Science - We're Not Confused Enough - A Response To Zwadlo

Uploaded by

3x4 ArchitectureCopyright:

Available Formats

We Do Need a Philosophy of Library and Information Science -- We're Not Confused Enough:

A Response to Zwadlo

Author(s): Gary P. Radford and John M. Budd

Source: The Library Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 3 (Jul., 1997), pp. 315-321

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40039736 .

Accessed: 16/06/2014 23:58

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Library Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

COMMENT

WE DO NEED A PHILOSOPHYOF LIBRARYAND INFORMATION

SCIENCE- WE'RENOT CONFUSED ENOUGH:

A RESPONSETO ZWADLO

GaryP. Radford1and John M. Budd2

Is there a philosophy of libraryscience? The thesis presented

here is that there is not, and we do not need one. That is,

we do not need, nor do we have, one single philosophy.

(JamesZwadlo [1] )

The title of Jim Zwadlo's recent essay,"We Don't Need a Philosophyof Library

Science- We'reConfusedEnoughAlready"[1] is intriguing.There is, no doubt,a

need for thoughtful,reflexiveexplorationsof the natureof libraryand information

science as a discipline.The paper's abstract,which states that "we do not need,

nor do we have,one single philosophy,to either fill a philosophicalvacuum,or to

replace an existingphilosophy,"is a provocativethesis.However,the questionre-

mains as to whetheror not Zwadlohas managedin this paper to offer a new way

of thinking about the intellectualchallenges confronting the discipline. On the

whole we have to answerin the negative,for a number of reasonsthat we discuss

below.

Firstof all, the title and the paper'sstated purpose are misleading.Despite his

centralthesisthatwe do not need a philosophyof libraryscience, Zwadloneeds to

(indeed, he must) invoke a particularphilosophicalfoundationto make his argu-

ment. In otherwords,Zwadloneeds philosophyto arguethatwe do not need philos-

ophy. Zwadlorecognizesthis in his abstract,where he statesthat "we need to find

a wayto manage a confusion, 'fused together' mass of many contradictoryideas,

in order to do useful things,and to be helpful to our patrons.This searchamounts

to a philosophicaldiscussionaboutwhylibrariansand informationscientistsdo not

need a philosophy"[1, p. 103].

Whilewe agree with the thesis that libraryand informationscience (LIS) could

certainlybenefitfromphilosophicaldiscussionof "contradictoryideas"in the field

"in order to do usefulthings,"Zwadlodoes not make the case for whya discussion

of "whylibrariansand informationscientistsdo not need a philosophy"would be

1. Department of Communication, William Paterson College of New Jersey, Wayne, New Jer-

sey 07470; E-mail: radford@frontier.wilpaterson.edu.

2. School of Libraryand Information Science, University of Missouri at Columbia, 104 Stewart

Hall, Columbia, Missouri 65211; E-mail: libsjmb@showme.missouri.edu.

[LibraryQuarterly,vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 315-321]

© 1997 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

0024-2519/97/6703-0005 $02.00

315

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

316 THE LIBRARYQUARTERLY

useful to anybody,whether they be practicinglibrarians,libraryusers, or philoso-

phers.Howwould thisbelief be usefulto a libraryuser?Or a librarianassistingthat

user? Or an LIS scholar empiricallyinvestigatingthe librarian-userrelationship?

Moreuseful,in our view,wouldbe a considerationof the philosophies,paradigms,

and frameworksthat do (and must) guide the day-to-daypracticesof libraryprac-

titioners,users, and researchers.

A majorproblemwithZwadlo'sargumentis the particularwayin whichhe charac-

terizesthe term"philosophy"as a strawman and inaccuratelyattributesthischarac-

terizationto the recent philosophicaldiscussionsof John Budd [2], GaryRadford

[3], and Archie Dick [4]. Zwadloportraysphilosophyas a kind of verbalmission

statementor creed that is articulated,presumablyby some form of authority,and

then "followed"on a rationalbasisby its adherents.This characterizationevokes

imagesof acolytesfollowinga religion. For example, Zwadlowritesthat "we seem

not to agree on which one [philosophy]we follow now, assumingwe even have

one, or which philosophyto choose to replace it" [1, p. 104] and that "even if

positivismwere the philosophyof LIS, it was not reallyfollowed, and was not an

appropriateone to follow" [1, p. 105]. The continued use of the word "follow"

characterizesphilosophyas a conscious,articulableset of rulesfor the rationaland

deliberateguidanceof thoughtand action.This is an easystrawman to knockdown

because it allowsZwadloto argue that no such consciousand articulablephiloso-

phies, including that positivism,can be found in the everydaypracticesand dis-

coursesof librariansand libraryscholarsand that, by extension, they do not need

one. Thus Zwadlospeculatesthat "perhapsone reasonwhymanylibrariansdo not

miss a philosophyof LIS is that writerson libraryand informationscience rarely

discussphilosophy" [1, p. 104]. But by placing philosophyat the level of formal

discourseand of clearand articulablecodes providedby LISphilosophers,Zwadlo

missesthe point of philosophizingabout issues germane to LIS.

The fact is thatlibraryinstitutionsand the people who workwithinand use them

are operatingwithinepistemologicalframeworksor normativesystemsthat enable

people to understandwhatthe libraryis, whatit does, and how one behaveswithin

its systems.For example, librarybuildingsand the location of the stacksand the

reference desk are somethingthat most people take for granted.But AbigailVan

Slyck[5] has recentlydescribed,througha historicaland architecturalanalysisof

the Carnegielibrariesfrom 1890 to 1920, how particularnorms, ideologies, and

power relationshipswere actualizedinto the architectureof librarybuildingsand

the layoutof their interiors.Zwadloarguesthat "This paper is about the missing

philosophyof libraryand informationscience (LIS). It is also about why so few

librariansseem to missit" [1, p. 103]. But it is not that philosophyis "missing"or

librariansmiss it, but that such practices and perspectivesbecome, in Thomas

Kuhn'sterms, "invisible"[6, pp. 136-43]. With respect to science, Kuhnwrites:

'

'Thoughmanyscientiststalkeasilyand well aboutthe particularindividualhypoth-

eses that underlie a concrete piece of currentresearch,they are little better than

laymenat characterizingthe establishedbasesof theirfield, its legitimateproblems

and methods. If they have learned such abstractionsat all, they show it mainly

throughtheir abilityto do successfulresearch.That abilitycan, however,be under-

stood withoutrecourseto hypotheticalrules of the game" [6, p. 47].

Zwadlomakesa similarpoint with respectto practitionersand scholarsof library

and informationscience:of course they can carryout their occupationalpractices

or researchwithoutbeing able to explicitlyarticulatethe underlyingparadigmatic

bases of their acts. However,this does not mean that such a basisis "missing,"in

Zwadlo'sterms. Indeed, it should be and is an object of great interest to library

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

COMMENT 317

and informationscholarsand philosophersto try to articulatethe natureof these

underlyingsystemsof knowledgeand power.It is this problematicthatis addressed

in the recent articlesby Budd [2], Radford[3], and Dick [4]. It is in this context

that Budd and Radfordequate this invisibleguiding paradigmwith the tenets of

positivism.They viewpositivismas a relevantproblematicfor LISscholarship,not

because it representsa frameworkthat needs to be overthrown,but ratheras an

"invisible"epistemologicalfoundation whose contours and structureshave not

been recognizedas such in the practicesof LIS practitionersand scholars.

The value of writerssuch as Budd, Radford,and Dick is that they attempt to

generatean awarenesswithinLISthat such an epistemologicalfoundationis pres-

ent at all, and that there are alternatives.As John Budd writes, "It is true that

method, data, evidence, and analysiscontributeto understanding,but something

is antecedentto all these.The keyto study,research,and discourseis a more funda-

mental understanding.This is achievedby delving into the nature of knowledge

and knowingin the field" [2, p. 315]. Thus Budd'sgoal is "to shift, firstthought,

then discourse,then research,by initiatinga questioningof assumptionsand pur-

pose" [2, p. 315]. Similarly,Radford's[3] objectiveis to questiona prevailingposi-

tivistorientationtowardknowledgein orderto foregrounddifferentviewsof knowl-

edge thathavethe potentialof providingalternativeframesof referencefromwhich

to re-createthe perceivedrealityof the libraryexperience.To articulatesuch alter-

nativeframeworks,one has to identifywhatthese frameworksare an alternativeto.

Thus, the critiqueof positivismis necessaryfirst in order to raise awarenessthat

alternativesexist, and, more important,that the idea of an alternativeworldview

even makessense. If the tenets of positivismremainimplicitand takenfor granted,

then discussionceases.

What Zwadloclaims to be the objectivesof these writersis quite differentand

misrepresentativeof their work.Zwadlowritesthat Budd, Radford,and Dick seek

to "implythata powerstruggleis the wayto choose philosophies,witha newphilos-

ophy adopted through a kind of culturalcoup" [1, p. 117], and that "perhaps

Budd and Radfordsee the confusion of LIS as a powervacuum,and thereforeas

an opportunityfor a moveto takepower.Theyproposenewphilosophiesthatwould

justifythe seizureof power,althoughit seems doubtfulthat the libraryhas the kind

of power that is seizeable" [1, p. 118].

WhatZwadlomeansby "seizureof power"is not made clear.Is it personalpower

thatBuddand Radfordseek?Or the powerto imposea particularmode of thought

and action?Who would be subjectto this power?Librarians?Users?Libraryschol-

ars?ClearlyZwadlo'suse of the term "power"is totallyinconsistentwith Budd's

and Radford'suse of the term. Budd and Radforddo not seek powerof any kind,

but only a discussionof power/ knowledgestructuresinherent in prevailinglibrary

discoursesand institutions.The misreadingof Budd's,Radford's,and Dick'swork

is clearin the followingstatementby Zwadlo:" [They] conveythe idea that for LIS,

obtaininga philosophyis somethinglike borrowinga book from our libraries.But

like the borrowedbooks, the borrowedphilosophiesdo not reallybelong to us,

alwaysseem to need to be renewed,and we end up returningthem, only to borrow

others" [1, p. 105]. The epistemologicalinvestigationand philosophicaldiscussion

found in Budd, Radford,and Dick is not about seizureof "power"or the mixing

and matchingof philosophicalfashions.Theyare the firststepson a road to greater

clarityaboutthe natureof the LISenterprise,not only in termsof whatframeworks

LISmight investigatein the futurebut also in termsof a greaterunderstandingof

the positivistfoundationof LIS at the present.

Zwadlospendsmuch of his paper discussingpositivismand whether"positivism

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

318 THE LIBRARYQUARTERLY

ever reallywas the philosophyof LIS" [1, p. 105]. The heart of the matteris not

whetheror not positivismhasworkedor is overduefor replacement.Indeed,positiv-

ism has a historyof successon a numberof fronts.As an epistemologyit has allowed

for the establishmentand growthof some of the social sciences,has given a basis

for knowledgeclaims,and has been useful in enablingresearchinitiativesto grow.

Further,it has afforded a rationalefor objectivityand value neutralitythat have

been mainstaysof social science practiceand inquiryfor manyyears.One of the

problemswith positivismin the social sciencesin general, and LISin particular,is

that its functioningas an epistemologicalfoundationhas not been recognized.It

has remainedlatent, assumed,and taken for granted,and, as such, has not been

subjectedto much criticalscrutiny.What Budd, Radford,and Dick have done is

generate an awarenessthat there is indeed an epistemologypresent in LIS, and

that there are alternativesto the tacitlyaccepted one- positivism.Partof the au-

thor'sintent is to makejust such a point. Zwadlostates,"The advantageof begin-

ning withoutthe assertionthatpositivismis the philosophyof LISis that it obviates

the need to specifyan alternativeto positivism"[1, p. 106]. Whilethis maybe true

on the surface,the taskof examiningthe foundationsof knowledgeand knowledge

growthin LISremainsthe same- exploringalternativewaysto envisionthe struc-

ture, methods, and validityof knowledge.

Statementssuch as the foregoingrenderit verydifficultto discernZwadlo's cen-

tral points. There appear to be some contradictionsand apparent misunder-

standingsregardingwhatpositivismis and whatBudd, Radford,and Dick observe.

Forinstance,Zwadlowritesthatpositivism,when found wanting,is changedby phi-

losophers,scientists,and others;Zwadlothen infersfrom the alterationsto positiv-

ism that it is too variablea philosophicalstanceto critique.For instance,in a note

Zwadloclaimsthat the variancesin expressionsof positivismnegate any possibility

of identifyingsome commonpreceptsamongthe severalstances.Thereis a seeming

rejectionof the premisethattherearesome consistentclaimsinherentin a positivist

epistemology,but there is no accompanyingexplanationof the rejection,save to

differingversionsof what has been called positivismover the years.Zwadlothen

almostwillfullymisreadsBudd and Radford,who illustratethat adherence to the

common claimsof positivismis not necessarilyconsciousin the minds of those in

LIS.At one point he cites Budd as makinga statementthat is actuallya reference

toJamesFaulconerand RichardWilliams[7]. He then assertsthat "attackingposi-

tivismactuallyis a positivistthing to do" [1, p. 108].

These and other misunderstandings demonstratea particularshortcomingof the

assumedepistemologythat has been dominantin LIS.SteveFuller [8] recognizes

that Comte and Millwere epistemologicalpioneers and that they were concerned

with the social constructionof knowledge.Not only do Budd, Radford,and Dick

not dispute such an assertionbut they too recognize the inevitablyof the social

aspectof knowledgeand knowledgegrowth.Fullergoes on to saythat "the continu-

ityof this concern [for the socialconstructionof knowledge]is nowadayslost, how-

ever, mainlybecauselogical positivism'slegacyhas been greaterin the techniques

it introducedfor doing epistemologythan in the actual project for which those

techniqueswere introduced"[8, p. 149]. It might be even more appropriateto say

that the legacyof positivismis the persistenceof its claims.If there is a quest,stated

or not, for underlyinglaws,alongwithan accompanyingreductionismand phenom-

enalism,the socialbecomeslost in the individual.Zwadloappearsto missthispoint.

Zwadlofurthermissesthe point of the socialin HansVaihingerand the philoso-

phy of "As If" [9]. If we were to accept Vaihinger'sthesis that knowledgegrows

by the use of fictions,we wouldhave to reach the conclusionthat some fictionsare

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

COMMENT 319

only effectiveif they are shared;that is, certain fictions that are constructedfor,

say,disciplinarypurposesto proposetheoriesor offerexplanationswouldfailunless

theyaresharedbyothersin the discipline.If, to use Zwadlo'sexample,classification

in librariesis a fiction thatworks,it can only workif most of us in LISagree to the

premisesof the fiction. That much is requiredto assurethat the fiction is main-

tainedand maintainedin a workableform.Whilesuch socialacceptanceis implied

by Vaihinger,he focusesmore on the individualand the psychicmechanismsthat

the individualemploysin both abstractand practicalendeavors.It is not verysur-

prisingthat Zwadlochooses Vaihingeras a foundationfor critiquingthe work of

Budd,Radford,and Dick.Vaihingerhimselfwasin some waysa precursorof logical

empiricismand was influenced by nineteenth-centuryFrench positivism.The in-

fluence of the pastand the connectionwiththe contemporaryand futureis evident

in statementssuch as the following:"Onlythroughthe reductionof the concepts,

'thought,action, observation,'etc., to elements ultimatelyphysiological,to sensa-

tion, do we obtain a correctstandardfor the valuationof logicalwork,which con-

vertselements of sensationinto logical structures"[9, p. 5].

Vaihinger,in his philosophyof "As If," is proposinga metaphilosophy - a far-

of

reachingprogram thinking about thinking.At the root of this metaphilosophy

is the assumptionthat almost all thought is governed by a psychic attractionto

fictions that can be used in place of fact, or even of truth, and that can embody

contradictionsthatenableus to conceivethingsthatwouldotherwisebe impossible.

A problemwithVaihinger's programis that,if it is correct,his own metaphilosophy

mayitselfbe a fiction.JayNewmansees this problemwithVaihingerand says,"We

are now in a position to see that fictionalismis self-defeating.There is Vaihinger,

lookingdownfromthe empyreanheightsof metaphilosophyat the mortalmetaphy-

sicianswho vainlyseek Truth. But if Vaihingeris going to be consistent,he must

admitthat metaphilosophicaltheorizingis no more objectivethan any other kind

of theorizing"[10, p. 55]. Zwadlocites RichardRortyand sayshe "concludedthat,

if we have no wayto choose between theories,we cannot choose at all, and so we

cannot have one theoryat all. If no theoryof knowledgecan tell us, a priori,that

it is better than a competing one, then we must live without such certainty,and

live withouta theorythat claimsthe specialprivilegeof telling us whatis true" [1,

p. 9] . If ZwadlobelievesRorty,then he would have to rejectVaihingeralong with

other alternativeepistemologies.

In completingthe critiqueof Budd,Radford,and Dick, Zwadlotakesin turn the

alternativespresentedin the three papers.In addressingphenomenology (a large

component of Budd's proposition) he speaks only of the personal ambitionsof

EdmundHusserland again cites Rortyas evidence that other phenomenologists

modifiedHusserl'sphilosophyand sometimesadamantlydisagreedwith him. Cer-

tainlythere are differingversionsof phenomenology,and Budd makes mention

of others, such as MartinHeidegger and Paul Ricoeur.Further,Budd notes the

complexityof dealingwithphenomenologyin a singlejournalarticleand the limita-

tions of a phenomenologybased solely on Husserl:"I recognize from the outset

thatEdmundHusserl'sphenomenologyis idealistic;that is, he envisionsphenome-

nology being able to make determinationsof essence and intention (for example)

that approachabsolute statements.Husserldoes, however,provideelements that

form an epistemic basis for phenomenology;that is, he constructsa framework

for an approachto knowingwhich is useful here" [2, p. 304]. Zwadlo'ssuperficial

dismissalof phenomenologyis indicativeof the lack of claritythat permeatesthe

paper.

Zwadlo'scritiqueof Radford'sdiscussionof MichelFoucaultis equallysuperficial

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

320 THE LIBRARYQUARTERLY

and consistsof the followingstatement:''AlthoughFoucaultwrote an essayabout

librariesit is difficultto see whathis philosophycan do for librariansand libraries"

[1, p. 28]. Firstof all, Foucault'sessay"Fantasiaof the Library"[11] wasnot about

librariesas institutionsbut was a literaryappreciationof GustaveFlaubert's"The

Temptationof SaintAnthony" [12]. Foucaultused the idea of "the library"as a

metaphorfor order and rationalityin contradistinctionto the idea of "fantasia."

Second, libraryscholarMichaelHarris[13] has describedFoucault'scontribution

to LISin termsof a desire to overturnthe powerof positivismin the socialsciences

and understandthe political economy of knowledgein new and innovativeways.

Harrisstatesthat "one can only wonderat the extent to whichFoucault'sworkhas

been ignored by such professionsas librarianshipand socialworkthatwould seem

to be in a position to benefit significantlyfrom his insights" [13, p. 116] and that

"librarians,who consider their practiceto be 'neutral'and apolitical,might find

Foucault'swork both challenging and disconcertingand, perhaps, redemptive"

[13, p. 116]. Zwadlo'sconclusion that "librariansshould use methods that work,

that serve the ends of the library,its users, and the community,instead of trying

to justifyprivilegedclaimsto truth" [1, p. 119] clearlyembracesthe idealisticidea

thatlibrarianscan somehowescapefromthe systemsof power/knowledge thatFou-

cault describesin his genealogies.Foucault'sworkdevelopsthe thesis that, at any

point in history,institutionsattempt to legitimatecurrentversionsof knowledge

and truth by controlling the manner in which texts are ordered with respect to

each other. Claimsto power and knowledgerely on "institutionalsupport:[they

are] both reinforcedand accompaniedby whole strataof practicessuch as peda-

gogy- naturally- the book system,publishing [and] libraries"[14, p. 219]. The

libraryis a key institutionin the legitimationof particularordersof discourseand

acts to enforce the "ensemble of rules accordingto which the true and false are

separated"[15, p. 132]. While Zwadlois correct in statingthat Foucaultdid not

write a book about libraries,Foucaultwrote much about the systemsof power/

knowledge in which libraries operate and derive their purposes and identity.

Clearly,Foucault'sphilosophyhas much to offer as a means of describing,under-

standing,and critiquinglibraryinstitutionsand their practices.

In conclusion,we returnto Zwadlo'scentralclaimthat "wedon't need a philoso-

phy of libraryand informationscience,we're confusedenough already."Our ques-

tions are,Who is confused?And whatare they confusedabout?If, as Zwadlostates,

"writerson libraryand informationscience rarelydiscussphilosophy"[1, p. 104],

then the scholarsare not confused. Librariansand libraryusers in their everyday

discourseand practiceare not confused.They knowwhat librariesare, what they

do, and how to interactwithin their confines. In our view, there is not enough

confusion.The invisibleepistemologicalstructuresand paradigmsof our field have

not been raised,until very recently,to philosophicalscrutiny.As a result, library

practitionersand scholarsoperatewithinthe field as a ready-madeand given entity

where confusionis minimizedby an underlyingideology.If we, as a field, are pre-

paredto acceptthissituationas Zwadloproposes,then we haveno wayto determine

the limits of that field and the means to transgressthem if we should wish. We

have no means to describe the processesby which the field enables certain types

of practicesand knowledgeand marginalizesand forbidsothers.We haveno wayto

describeand understandhow the roles and relationshipswithinlibraryinstitutions

become constitutedand the systemsof power that they inevitablyserve.We have

no means of understandinghow knowledgeabout libraryprocessesis generated

and givenvalidityin libraryscholarship.The statusquo is cozyand easyto manage.

It discouragesconfusionin its constantmovementsto preserveitselfagainstalterna-

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

COMMENT 321

tiveworldviews.We need to understandthatprocessin order to overcomeit. Thus,

in responseto Zwadlo,we loudlyadvocatethat we do need a philosophyof library

and informationscience;we are not confused enough!

REFERENCES

1. Zwadlo, James. "We Don't Need a Philosophy of Library Science - We're Confused

Enough Already." LibraryQuarterly67 (April 1997): 103-21.

2. Budd, John M. "An Epistemological Foundation for Library and Information Science."

LibraryQuarterly65 (July 1995): 295-318.

3. Radford, Gary P. "Positivism, Foucault, and the Fantasia of the Library:Conceptions of

Knowledge and the Modern Library Experience." LibraryQuarterly62 (October 1992):

408-24.

4. Dick, Archie L. "Libraryand Information Science as a Social Science: Neutral and Norma-

tive Conceptions." LibraryQuarterly65 (April 1995): 216-35.

5. Van Slyck, Abigail A. Freeto All: CarnegieLibrariesand AmericanCulture,1890-1920. Chi-

cago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

6. Kuhn, Thomas. TheStructureof ScientificRevolutions.2d ed. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1970.

7. Faulconer, James E., and Williams, Richard N. "Temporality in Human Action: An Alter-

native to Positivism and Historicism." AmericanPsychologist40 (November 1985): 1179-

88.

8. Fuller, Steve. "On Regulating What Is Known: A Way to Social Epistemology." Synthese

73 (October 1987): 145-83.

9. Vaihinger, Hans. ThePhilosophyof "AsIf "New York: Harcourt Brace, 1925.

10. Newman, Jay. "The Fictionalist Analysis of Some Moral Concepts." Metaphilosophy12

(January 1981): 47-56.

11. Foucault, Michel. "Fantasia of the Library." Translated by Donald F. Bouchard and

Sherry Simon. In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice:SelectedEssaysand InterviewsbyMichel

Foucault,edited by Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1977.

12. Flaubert, Gustave. The Temptationof Saint Anthony. Translated, with introduction and

notes, by Kitty Mrosovsky. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1981.

13. Harris, Michael. Review of "Michel Foucault." LibraryQuarterly63 (January 1993): 115-

16.

14. Foucault, Michel. "The Discourse on Language." Translated by Rupert Sawyer. In The

Archaeologyof Knowledge,by Michel Foucault. New York: Pantheon, 1972.

15. Foucault, Michel. "Truth and Power." Translated by Colin Gordon. In Power/Knowledge:

SelectedInterviewsand OtherWritings,byMichelFoucault, 1972-1977, edited by Colin Gor-

don. New York: Pantheon, 1980.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.62 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 23:58:16 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Alvesson 2000 Reflexive Methodology PDFDocument340 pagesAlvesson 2000 Reflexive Methodology PDFAlessandra Nogueira Lima90% (10)

- G. Frankenberg - Critical Comparisons Re-Thinking Comparative LawDocument47 pagesG. Frankenberg - Critical Comparisons Re-Thinking Comparative LawIrene VanniNo ratings yet

- Psychic Reading Waiver and DisclaimerDocument2 pagesPsychic Reading Waiver and Disclaimer3x4 Architecture100% (1)

- Repetition and MinimalismDocument12 pagesRepetition and MinimalismFDRbard100% (1)

- Basic Tenets of PsychologyDocument48 pagesBasic Tenets of PsychologyRanjan LalNo ratings yet

- Biography of Murdo MacDonald-BayneDocument5 pagesBiography of Murdo MacDonald-BayneLora M100% (1)

- Classical Approaches To WorkDocument45 pagesClassical Approaches To WorkSaaish Rao90% (10)

- "We Don't Need A Philosophy of Library and Information Science: We're Confused Enough" ZwadloDocument20 pages"We Don't Need A Philosophy of Library and Information Science: We're Confused Enough" ZwadloPablo MelognoNo ratings yet

- Haslanger KnowledgeOughtBe 1999Document23 pagesHaslanger KnowledgeOughtBe 1999Estela c:No ratings yet

- IJISRT24JUN893 PracticalismDocument6 pagesIJISRT24JUN893 PracticalismSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- Embedding "Practicalism" As An Intrinsic Constituent of The Philosophy of Science: Positioning "Practicalism" As An Essential Pre-Requisite For Rapid Scientific ProgressDocument6 pagesEmbedding "Practicalism" As An Intrinsic Constituent of The Philosophy of Science: Positioning "Practicalism" As An Essential Pre-Requisite For Rapid Scientific ProgressInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Vdocuments - MX - Philosophy An Introductionby J M BochenskiDocument4 pagesVdocuments - MX - Philosophy An Introductionby J M Bochenskimsns1981No ratings yet

- International Phenomenological SocietyDocument7 pagesInternational Phenomenological Societyandre ferrariaNo ratings yet

- Szostak, R InterdisciplinaryKnowledgeOrganization (2016)Document241 pagesSzostak, R InterdisciplinaryKnowledgeOrganization (2016)academicjbtNo ratings yet

- Archeology of LibraryDocument19 pagesArcheology of LibraryHeni PujiastutiNo ratings yet

- Sujay Irreducible Simplicity Final Final Final Final FinalDocument10 pagesSujay Irreducible Simplicity Final Final Final Final FinalSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- 1 Godfrey-Smith 03 Kap-1Document9 pages1 Godfrey-Smith 03 Kap-1Luciano Carvajal JorqueraNo ratings yet

- Dreyer, Jaco S., Knowledge, Subjectivity, (De) Coloniality, and The Conundrum of ReflexivityDocument26 pagesDreyer, Jaco S., Knowledge, Subjectivity, (De) Coloniality, and The Conundrum of ReflexivityHyunwoo KooNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Science PDFDocument332 pagesCognitive Science PDFJOSEPH MONTESNo ratings yet

- Educational Research Philosophy ApplicationDocument128 pagesEducational Research Philosophy Application4066596No ratings yet

- Elucidating The Certainty Uncertainty Principle For The Social Sciences Guidelines For Hypothesis Formulation in The Social Sciences For Enhanced Objectivity and Intellectual Multi-PolarityDocument20 pagesElucidating The Certainty Uncertainty Principle For The Social Sciences Guidelines For Hypothesis Formulation in The Social Sciences For Enhanced Objectivity and Intellectual Multi-PolarityInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The Future of Knowledge Organization and Information OrganizationDocument6 pagesThe Future of Knowledge Organization and Information OrganizationIgor AmorimNo ratings yet

- Review of Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of EducationDocument6 pagesReview of Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of EducationFELIPE GIRONDONo ratings yet

- What Are Academic DisciplinesDocument59 pagesWhat Are Academic DisciplinesJohn Michael ArtangoNo ratings yet

- Towards Institutional Coherentism in Scientific Endeavour FINAL FINAL FINAL FINAL FINALDocument10 pagesTowards Institutional Coherentism in Scientific Endeavour FINAL FINAL FINAL FINAL FINALSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff On Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCDocument30 pagesThis Content Downloaded From:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff On Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCIgnacio VergaraNo ratings yet

- Sujay Practicalism Final Final Final Final FinalDocument10 pagesSujay Practicalism Final Final Final Final FinalSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- Faraday Paper 3 Alexander - ENDocument4 pagesFaraday Paper 3 Alexander - ENNuno GuerreiroNo ratings yet

- Dorothy Giles WilliamsDocument3 pagesDorothy Giles WilliamsShalu SinhaNo ratings yet

- IJISRT24JUN620 Probabilistc ApproachesDocument6 pagesIJISRT24JUN620 Probabilistc ApproachesSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- Why An Alignment of Hypothesis-Formulation and Theorization With Cultural and Cross-Cultural Frames of Reference Is Required: A Rough Guide To Better Hypothesis-Formulation and TheorizationDocument6 pagesWhy An Alignment of Hypothesis-Formulation and Theorization With Cultural and Cross-Cultural Frames of Reference Is Required: A Rough Guide To Better Hypothesis-Formulation and TheorizationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The PHD in Writing Accompanied by An Exegesis: Journal of University Teaching & Learning PracticeDocument17 pagesThe PHD in Writing Accompanied by An Exegesis: Journal of University Teaching & Learning PracticeEzlina AhnuarNo ratings yet

- Book Review: The Cambridge Companion To The Philosophy of Biology.-EditedDocument2 pagesBook Review: The Cambridge Companion To The Philosophy of Biology.-EditedAizen SousukeNo ratings yet

- Fuller 1991Document26 pagesFuller 1991Jean KwonNo ratings yet

- Literature Review EpistemologyDocument9 pagesLiterature Review Epistemologyc5qxzdj7100% (1)

- CASE Looking For Information 7Document29 pagesCASE Looking For Information 7KjhllsjjNo ratings yet

- Michael Bowler Review IIDocument4 pagesMichael Bowler Review IILee Michael BadgerNo ratings yet

- Collins TEA SetDocument22 pagesCollins TEA SetFabricio NevesNo ratings yet

- A Heterodox Reading of Jayadeva Uyangoda's Social Research: Philosophical & Methodological Foundations - Vangeesa SumanasekeraDocument3 pagesA Heterodox Reading of Jayadeva Uyangoda's Social Research: Philosophical & Methodological Foundations - Vangeesa SumanasekeraSocial Scientists' Association100% (1)

- Research Reflexivity Final Submission 27042020Document15 pagesResearch Reflexivity Final Submission 27042020Tasos TravasarosNo ratings yet

- Harding 230106 230029Document20 pagesHarding 230106 230029uzzituziiNo ratings yet

- Ben-David e CollinsDocument16 pagesBen-David e CollinsRicardo StreichNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Education: Semester:3 (Ste Exams)Document8 pagesPhilosophy of Education: Semester:3 (Ste Exams)Muhammad zeeshanNo ratings yet

- (Perspectives in Social Psychology) Arie W. Kruglanski (Auth.) - Lay Epistemics and Human Knowledge - Cognitive and Motivational Bases-Springer US (1989)Document286 pages(Perspectives in Social Psychology) Arie W. Kruglanski (Auth.) - Lay Epistemics and Human Knowledge - Cognitive and Motivational Bases-Springer US (1989)Rodrigo Seixas100% (1)

- Valor de Ser DesagradableDocument23 pagesValor de Ser DesagradableginopieroNo ratings yet

- Shaheed Muhammad Baqir As Sadr Logical Foundations of InductionDocument190 pagesShaheed Muhammad Baqir As Sadr Logical Foundations of InductionAli Asghar ShahNo ratings yet

- Maggetti Et Al (2013) Social Sciences and Research DesigDocument21 pagesMaggetti Et Al (2013) Social Sciences and Research DesigAlvaro Hernandez FloresNo ratings yet

- Scientific Models for Religious Knowledge: Are the Scientific Study of Religion and a Religious Epistemology Compatible?From EverandScientific Models for Religious Knowledge: Are the Scientific Study of Religion and a Religious Epistemology Compatible?No ratings yet

- American Educational Research AssociationDocument9 pagesAmerican Educational Research AssociationAbdul Rasyid HarahapNo ratings yet

- The Good The BadDocument9 pagesThe Good The BadAbdul Rasyid HarahapNo ratings yet

- READ 6 Phillips 1995Document9 pagesREAD 6 Phillips 1995Havva Kurt TaşpınarNo ratings yet

- FulltextDocument16 pagesFulltextAnderson BerbesiNo ratings yet

- Howard S. Becker - Falando Da Sociedade - Ensaio Sobre As Diferentes Maneiras de Representar o Social-Zahar (2014)Document22 pagesHoward S. Becker - Falando Da Sociedade - Ensaio Sobre As Diferentes Maneiras de Representar o Social-Zahar (2014)Marco CastroNo ratings yet

- HellawellDocument13 pagesHellawellLilaNo ratings yet

- IJISRT24FEB243 Sujay Rao MandavilliDocument6 pagesIJISRT24FEB243 Sujay Rao MandavilliSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- Instituting "Institutional Coherentism" As A Prerequisite For High-Quality Science: Another Crucial Step For Winning The Battle For Consistent High-Quality ScienceDocument6 pagesInstituting "Institutional Coherentism" As A Prerequisite For High-Quality Science: Another Crucial Step For Winning The Battle For Consistent High-Quality ScienceInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Basic Level Categories JIS2013 PreprintDocument14 pagesBasic Level Categories JIS2013 PreprintAviv SchoenfeldNo ratings yet

- Hull Informal AspectsDocument19 pagesHull Informal AspectsJavier MorenoNo ratings yet

- Intelligen & IntellectDocument7 pagesIntelligen & Intellectnishah.020289No ratings yet

- Wiley Ontario Institute For Studies in Education/University of TorontoDocument8 pagesWiley Ontario Institute For Studies in Education/University of Torontokanga_rooNo ratings yet

- What Is Knowledge Organization Finalrev CorrectedcDocument28 pagesWhat Is Knowledge Organization Finalrev CorrectedcAugustine OkohNo ratings yet

- Synthese Kluweracademic Publishers. Printed in The NetherlandsDocument19 pagesSynthese Kluweracademic Publishers. Printed in The NetherlandsLuiz Guilherme Araujo GomesNo ratings yet

- On The Educative Reading of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, L Vlie, L. (1995) - Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 39 (4), 277-294Document20 pagesOn The Educative Reading of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, L Vlie, L. (1995) - Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 39 (4), 277-2943x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Enchained Division - Blake's Orc, Dialectical Sacrifice, and The Revolutionary's Path of ResistanceDocument20 pagesEnchained Division - Blake's Orc, Dialectical Sacrifice, and The Revolutionary's Path of Resistance3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Advaita Vedānta and Typologies of Multiplicity and Unity - An Interpretation of Nondual Knowledge by Joseph Milne PDFDocument25 pagesAdvaita Vedānta and Typologies of Multiplicity and Unity - An Interpretation of Nondual Knowledge by Joseph Milne PDF3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Jung and Phenomenology PDFDocument3 pagesJung and Phenomenology PDF3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Berkeley Zoning Origins PDFDocument19 pagesBerkeley Zoning Origins PDF3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- 1494965444-17 18 WritingProcessDocument2 pages1494965444-17 18 WritingProcess3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Double Debunking Modern Divinatio PDFDocument47 pages2015 - Double Debunking Modern Divinatio PDF3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Extract From 2013 Housing Needs AssessmentDocument8 pagesExtract From 2013 Housing Needs Assessment3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Alan Moore's Promethea: Countercultural Gnosis and The End of The WorldDocument25 pagesAlan Moore's Promethea: Countercultural Gnosis and The End of The World3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Evangelions Human Instrumentality Projec PDFDocument5 pagesEvangelions Human Instrumentality Projec PDF3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Toby Houston Toole - The Ways of Reflection - Heidegger, Science, Reflection, and Critical InterdisciplinarityDocument67 pagesToby Houston Toole - The Ways of Reflection - Heidegger, Science, Reflection, and Critical Interdisciplinarity3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

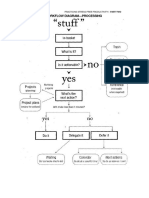

- Workflow Diagram-Processing: Practicing Stress-Free Productivity I Part TwoDocument1 pageWorkflow Diagram-Processing: Practicing Stress-Free Productivity I Part Two3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Child Abduction PreventionDocument4 pagesChild Abduction Prevention3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Vietnam DBQDocument7 pagesVietnam DBQapi-282797941No ratings yet

- Interview With Professor Piers HaleDocument4 pagesInterview With Professor Piers HaleAlex LinNo ratings yet

- Importance of Buddhist VandanaDocument3 pagesImportance of Buddhist VandanaUpali SramonNo ratings yet

- Myth and Worldview in Wole Soyinka's Death and The KIng's Horseman and Ola Rotimi's The Gods Are Not To BlameDocument67 pagesMyth and Worldview in Wole Soyinka's Death and The KIng's Horseman and Ola Rotimi's The Gods Are Not To BlameCaleb Kayleby Adoh100% (2)

- Tantra YogaDocument7 pagesTantra Yogahiren1206No ratings yet

- Senada Lamovska - Security Is What The State Makes of It. The Greece-Macedonia Name Dispute (2012)Document65 pagesSenada Lamovska - Security Is What The State Makes of It. The Greece-Macedonia Name Dispute (2012)MacedonianoNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Education Solved MCQ's With PDF Download (Set-2)Document10 pagesPhilosophy of Education Solved MCQ's With PDF Download (Set-2)Nilam ThatoiNo ratings yet

- Karl Barth, Walter Benjamin, and Historical MediationDocument38 pagesKarl Barth, Walter Benjamin, and Historical MediationKhegan DelportNo ratings yet

- CODINGDocument29 pagesCODINGBlack RoseNo ratings yet

- I. An Individual Group Relations.: Individualism vs. CollectivismDocument23 pagesI. An Individual Group Relations.: Individualism vs. CollectivismDeogratias LaurentNo ratings yet

- BRAUND & GILL (Eds) - The Pas Sions in Roman Thought and Literature (Epicuro Ciceron Seneca Tacito Catulo Virgilio)Document276 pagesBRAUND & GILL (Eds) - The Pas Sions in Roman Thought and Literature (Epicuro Ciceron Seneca Tacito Catulo Virgilio)Dionisie Constantin PirvuloiuNo ratings yet

- Self-Knowledge and Self-MasteryDocument14 pagesSelf-Knowledge and Self-Masteryあかさ あか100% (1)

- (Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 37 Iss. 1) Francisco R. Demetrio - The Shaman As Psychologist (1978) (10.2307 - 1177583)Document20 pages(Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 37 Iss. 1) Francisco R. Demetrio - The Shaman As Psychologist (1978) (10.2307 - 1177583)Lynnlin GamingNo ratings yet

- Un-Instagramable Self SpacecatDocument3 pagesUn-Instagramable Self Spacecatapi-525669940No ratings yet

- DISS Quarter 1 Module 5 7Document21 pagesDISS Quarter 1 Module 5 7Mark Anthony GarciaNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Attitude SurveyDocument2 pagesMathematics Attitude SurveyDanilo Siquig Jr.No ratings yet

- David C. Palmer - The Role of Private Events in The Interpretation of Complex BehaviorDocument18 pagesDavid C. Palmer - The Role of Private Events in The Interpretation of Complex BehaviorAnonymous srkJwyrgNo ratings yet

- Theinngu Method of MeditationDocument74 pagesTheinngu Method of MeditationPe Chit MayNo ratings yet

- Thinking Insights: Learning Activity SheetsDocument3 pagesThinking Insights: Learning Activity SheetsMhairo Akira67% (3)

- A10EL-Ib-1 A10EL-Ia-2 A10EL-Ia-3: Have The Class Answers TheDocument2 pagesA10EL-Ib-1 A10EL-Ia-2 A10EL-Ia-3: Have The Class Answers TheJoshua GuiriñaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Foundations of The Translation TheoryDocument3 pagesTheoretical Foundations of The Translation TheoryresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Roger Scruton - T S Eliot As Conservative MentorDocument8 pagesRoger Scruton - T S Eliot As Conservative MentorVitorsolianoNo ratings yet

- From Heidegger To Suhrawardi 'Mundus ImaginalisDocument23 pagesFrom Heidegger To Suhrawardi 'Mundus ImaginalisIsmael Kabbaj100% (1)

- Political Science Paper-I Part A Study Area 1-Western Political ThoughtDocument9 pagesPolitical Science Paper-I Part A Study Area 1-Western Political ThoughtAfzaal AhmadNo ratings yet

- BUDDHISMDocument17 pagesBUDDHISMFlare MontesNo ratings yet