Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Medication Errors: Prescribing Faults and Prescription Errors

Medication Errors: Prescribing Faults and Prescription Errors

Uploaded by

Cut Shanah Roidotul IlmiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Medication Errors: Prescribing Faults and Prescription Errors

Medication Errors: Prescribing Faults and Prescription Errors

Uploaded by

Cut Shanah Roidotul IlmiCopyright:

Available Formats

British Journal of Clinical DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03425.

Pharmacology

Correspondence

Medication errors: Professor Giampaolo P. Velo, Clinical

Pharmacology Unit, Policlinico ‘G.B. Rossi’,

P. le L.A. Scuro 10, 37134 Verona, Italy.

prescribing faults and Tel: +39 045 8027451 - +39 045 8124904

Fax: +39 045 8027452 - +39 045 8124876

E-mail: gpvelo@sfm.univr.it

prescription errors ----------------------------------------------------------------------

Keywords

drug monitoring, drug prescription, fault,

Giampaolo P. Velo & Pietro Minuz1 medication error, training

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Clinical Pharmacology Unit and 1Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Verona, Italy Accepted

18 March 2009

1. Medication errors are common in general practice and in hospitals. Both errors in the act of writing (prescription errors) and

prescribing faults due to erroneous medical decisions can result in harm to patients.

2. Any step in the prescribing process can generate errors. Slips, lapses, or mistakes are sources of errors, as in unintended omissions in

the transcription of drugs. Faults in dose selection, omitted transcription, and poor handwriting are common.

3. Inadequate knowledge or competence and incomplete information about clinical characteristics and previous treatment of

individual patients can result in prescribing faults, including the use of potentially inappropriate medications.

4. An unsafe working environment, complex or undefined procedures, and inadequate communication among health-care personnel,

particularly between doctors and nurses, have been identified as important underlying factors that contribute to prescription errors

and prescribing faults.

5. Active interventions aimed at reducing prescription errors and prescribing faults are strongly recommended. These should be

focused on the education and training of prescribers and the use of on-line aids. The complexity of the prescribing procedure should

be reduced by introducing automated systems or uniform prescribing charts, in order to avoid transcription and omission errors.

Feedback control systems and immediate review of prescriptions, which can be performed with the assistance of a hospital

pharmacist, are also helpful. Audits should be performed periodically.

Prescribing faults and prescription errors are major prob- Prevalence

lems among medication errors. They occur both in

general practice and in hospital, and although they are The prevalence of prescribing faults and prescription

rarely fatal they can affect patients’ safety and quality of errors has been quantified in prospective and retrospec-

healthcare. A definition states that a ‘clinically meaningful tive cohort studies. Internal or external reviews of prescrip-

prescribing error occurs when . . . there is an uninten- tions, performed mostly by experienced pharmacists, or

tional significant reduction in the probability of treat- direct interviews or voluntary reports from prescribers

ment being timely and effective or increase in the risk of have been used as sources of information [4, 5]. Depending

harm when compared with generally accepted practice’ on the reference parameters used, the observed incidence

[1]. This definition is clearly oriented to the outcome varies greatly. It is usually higher in process-oriented

of the error. However, it does not take into account studies, which evaluate the presence in the prescription

failures that can occur during the whole process of of potentially harmful errors, than in outcome-oriented

prescribing, independently of any potential or actual studies, which mostly evaluate the incidence of prevent-

harm [2]. Prescription errors encompass those related to able adverse drug effects. Prescription errors account for

the act of writing a prescription, whereas prescribing 70% of medication errors that could potentially result in

faults encompass irrational prescribing, inappropriate adverse effects. A mean value of prescribing errors with the

prescribing, underprescribing, overprescribing, and inef- potential for adverse effects in patients of about 4 in 1000

fective prescribing, arising from erroneous medical judge- prescriptions was recorded in a teaching hospital. Such

ment or decisions concerning treatment or treatment errors are also frequent in ambulatory settings [4–6].

monitoring [3, 4]. Appropriate prescribing results when However, given the inconsistency of the criteria used to

errors are minimized and when the prescriber actively identify errors and the various definitions used, it is not

endeavours to achieve better prescribing: both actions surprising that a recent meta-analysis showed that the

are required. range of errors attributable to junior doctors, who are

624 / Br J Clin Pharmacol / 67:6 / 624–628 © 2009 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2009 The British Pharmacological Society

Prescribing faults and prescription errors

responsible for most prescriptions in hospitals, can vary inadequate feedback control or lack of cooperation

from 2 to 514 per 1000 prescriptions and from 4.2 to 82% between doctor and nurses, with undefined roles concern-

of patients or charts reviewed [7]. ing responsibility in prescribing, generate a cascade of

errors that can lead to an adverse effect. Among doctors,

stressful conditions, a heavy workload, a difficult work envi-

Sources ronment, insufficient communication within the team,

and not being in good physical and mental condition are

All procedures related to prescribing are error-generating among the primary causes of prescribing faults and

steps. A prescribing fault can arise from the choice of the prescription errors [8].

wrong drug, the wrong dose, the wrong route of adminis- Inappropriate prescribing most often derives from a

tration, and the wrong frequency or duration of treatment, wrong medical decision, because of lack of knowledge or

but also from inappropriate or erroneous prescribing in inadequate training. Junior doctors often work in stressful

relation to the characteristics of the individual patient or circumstances that are perceived as routine by experi-

co-existing treatments; it may also depend on inadequate enced doctors. Errors are more frequently made by junior

evaluation of potential harm deriving from a given treat- members of staff and inadequate knowledge or training

ment [3, 8]. Errors in dose selection occur most commonly, often underlie inappropriate prescribing and other faults

and represent >50% of all prescribing faults. [3, 8]. Inadequate staffing, lack of skills and knowledge of

Inaccuracy in writing and poor legibility of handwrit- relevant rules, tasks outside the routine, or taking care of

ing, the use of abbreviations or incomplete writing of a another doctor’s patient have also been identified as

prescription, for example by omitting the total volume of conditions associated with prescribing faults [8].

solvent and duration of a drug infusion, can lead to misin- Adverse outcomes can be related to lack of knowledge

terpretation by healthcare personnel. This can result in or skill. Even the apparently simple act of transcribing pre-

errors in drug dispensing and administration. Unintended vious medications and collecting information as part of

omissions – or failure to withdraw a drug – are also fre- the medication history requires a knowledge of pharmaco-

quent. A critical point is the transcription of previous therapy as well as adequate information about the patient’s

treatments at the time of admission to hospital, so- clinical condition. Equally, the choice of dose requires infor-

called ‘medication reconciliation’. Unintended omission or mation about the patient’s clinical status and immediate

changes in the dosing regimen are frequent, and account verification of the appropriateness of treatment.

for 15–59% of medication errors [9]. Inaccurate medication Factors related to patients can also result in errors,

history taking can cause omission of treatment, resulting in leading to adverse effects, since these are associated in

potential harm in more than one-third of patients taking most cases with identifiable clinical conditions, such as

more than four drugs [10]. Transfer of a patient’s care reduced renal and hepatic function or a history of allergy

within the same institution or between a hospital and a requiring atypical or unusual dosage and frequency [3, 15].

general practitioner also favours prescribing faults due to Polypharmacy and management of elderly patients or chil-

omission [11]. dren are associated with inappropriate or potentially inap-

Why do these errors occur? According to the theories of propriate prescribing and errors [15]. Monitoring of drug

human error, errors in prescribing, as in any other complex action is necessarily part of the prescribing process, to

and high-risk procedure, are occasioned by and depend on allow optimization or adjustments of doses or treatments.

failure of individuals, but are generated, or at least facili- In ambulatory care, prescribing faults are mostly related to

tated, by failures in systems [12]. It might therefore be the use of inappropriate doses and inadequate monitoring

expected that the larger the number of prescriptions, [16].

and the more steps in the prescribing procedure, the

higher the risk of error.

Prescription errors are typically events that derive from Prevention

slips, lapses, or mistakes [2], for example, writing a dose that

is orders of magnitude higher or lower than the correct Acquisition of information through error-reporting

one because of erroneous calculation, or erroneous pre- systems is a prerequisite for preventing prescribing faults

scription due to similarities in drug brand names or phar- and prescription errors, as is the adoption of shared criteria

maceutical names [13]. Human factors may therefore be for the appropriateness of procedures. Error-reporting

the first identifiable causes of error. However, in most cases, systems, both internal and external to healthcare institu-

analysis of error-inducing conditions shows an unsafe tions, have been widely used [14, 17–19]. Reporting is

environment as the ‘latent condition’ that contributes to usually voluntary and confidential, but must be timely and

the accident. According to Reason’s‘Swiss cheese’model of evaluated by experts, in order to identify critical conditions

accident causation, sequential failures in the system and and allow systems analysis. Prescribers should be informed

insufficient defences and counteractions are required for and become aware of errors that have been made in their

the event to occur [14]. In the case of prescribing errors, environment and of the conclusions of the analysis.

Br J Clin Pharmacol / 67:6 / 625

G. Velo & P. Minuz

Spontaneous reporting is about 10 times less effective Prescription charts

in detecting errors and potential adverse effects than Nevertheless, electronic systems are not yet widely avail-

active interventions, such as chart review and patient able, are expensive, and require training. Comprehensive

monitoring [20]. Active, systems-oriented interventions interventions aimed at improving patient safety using a

aimed at improving processes, rather than individual per- systematic approach are progressing in different institu-

formance, should therefore be advocated [14, 21]. Three tions, with the use of uniform medication charts, on which

major intervention strategies can be adopted: all the relevant clinical information is shown along with

the prescriptions, so that transcription is abolished. This

• reduction of complexity in the act of prescribing by the approach has been validated as a relatively simple alterna-

introduction of automation; tive to electronic drug prescribing and dispensing systems

• improved prescribers’ knowledge by education and the [24]. Furthermore, the use of electronic systems in addition

use of on-line aids; to a single uniform medication chart forces staff to develop

• feedback control systems and monitoring of the effects of interdisciplinary collaboration and procedures that allow

interventions [22]. immediate feedback control both among prescribers and

between prescribers and other staff (e.g. non-prescribing

nurses) (Figure 1).

Computerized systems The input of a hospital pharmacist has been regarded

The use of automated prescribing systems is recom- as a major contribution to the identification and reduction

mended as an effective tool to reduce medication errors. of error and is therefore recommended if it can be

They can reduce the risk of harm that arises from prescrib- afforded. Frequent review of prescriptions with the aid of a

ing faults and improve the quality of medical care by pharmacist reduces adverse effects, as recent reviews of

reducing errors in drug dispensing and administration. the literature have shown [25, 26].

Computerized advice can give significant benefits by

guiding the prescription of optimal dosages. This should

translate into reduced time to therapeutic stabilization, Education and systems approaches

reduced risks of adverse effects, and eventually reduced Education of medical students and junior doctors is

lengths of hospital stay [23]. highly advisable [27, 28]. Training and feedback control of

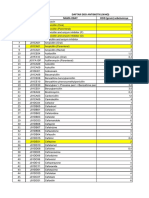

Prescription

The five ‘rights’:

REPORTING ERRORS - Patient

- Drug

- Dose

- Route

PRESCRIPTION

- Timing (frequency and duration)

Use on-line aids to prescription

and automated medication systems

or uniform medication charts

JUNIOR DOCTOR SENIOR DOCTOR Review of prescription

Monitor clinical benefits and

harms from treatment:

- Beneficial effects

- Adverse drug reactions

- Drug-drug interactions

REVIEW OF

Monitor plasma concentrations

PRESCRIPTION

or biomarkers to evaluate

adherence, benefits, and harms

Figure 1

A diagram of active interventions aimed at reducing adverse drug-related events

626 / 67:6 / Br J Clin Pharmacol

Prescribing faults and prescription errors

prescribing by tutors and senior doctors should be associ- 3 Lesar TS, Briceland L, Stein DS. Factors related to errors in

ated with availability of on-line references for immediate medication prescribing. JAMA 1997; 277: 312–7.

identification and verification of potential prescribing 4 Dean B, Vincent C, Schachter M, Barber N. The incidence of

faults [29]. The choice of treatment should generally be in prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: an overview of the

line with approved guidelines, although flexibility may be research methods. Drug Saf 2005; 28: 891–900.

necessary in individual cases.

5 Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Prescribing errors

Constraints can minimize omissions, for example the

in hospital inpatients: their incidence and clinical

introduction of check lists or strict rules in writing a pre- significance. Qual Saf Health Care 2002; 11: 340–4.

scription, and the use of well-structured medication charts,

as mentioned above. Handwritten prescriptions should 6 Kuo GM, Phillips RL, Graham D, Hickner JM. Medication errors

not contain ambiguous abbreviations or symbols. Fre- reported by US family physicians and their office staff. Qual

quent and immediate review of prescriptions as well as Saf Health Care 2008; 17: 286–90.

monitoring of potential harms deriving from treatment 7 Ross S, Bond C, Rothnie H, Thomas S, Macleod MJ. What is

should be encouraged. Polypharmacy requires special the scale of prescribing errors committed by junior doctors?

attention. Potentially inappropriate medications should be A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 67: 629–40.

identified, and drugs with narrow therapeutic ranges or 8 Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of

associated with frequent adverse reactions should be prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study.

avoided if possible and carefully monitored when used. Lancet 2002; 359: 1373–8.

Careful evaluation of drug–drug interactions and all

types of adverse reactions is necessarily part of a pro- 9 Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, Tam V, Shadowitz S,

Juurlink DN, Etchells EE. Unintended medication

gramme aimed at improving patient safety and may

discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern

require monitoring of plasma drug concentrations and Med 2005; 165: 424–9.

evaluation of biomarkers of beneficial or adverse effects.

Audit can contribute to appropriate prescribing and error 10 Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL, Fine N, Marchesano R,

reduction [24]. Etchells EE. Frequency, type and clinical importance of

medication history errors at admission to hospital: a

systematic review. CMAJ 2005; 173: 510–5.

Conclusion 11 Knudsen P, Herborg H, Mortensen AR, Knudsen M,

Hellebek A. Preventing medication errors in community

Errors and faults in prescribing are in most cases prevent- pharmacy: root-cause analysis of transcription errors. Qual

able. Intervention strategies should be primarily focused Saf Health Care 2007; 16: 285–90.

on education and the creation of a safe and cooperative

12 Reason JT, Carthey J, de Leval MR. Diagnosing ‘vulnerable

working environment, to strengthen defence systems and system syndrome’: an essential prerequisite to effective risk

minimize harm to the patient. management. Qual Health Care 2001; 10 (Suppl. II): ii21–5.

Systems-oriented interventions increase awareness of

risk among healthcare personnel [14]. Interventions aimed 13 Aronson JK. Medication errors resulting from the confusion

at improving knowledge and training, and reducing com- of drug names. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2004; 3: 167–72.

plexity, and the introduction of strict feedback control and 14 Nolan TW. System changes to improve patient safety. BMJ

monitoring systems are highly advisable. However, large- 2000; 320: 771–3.

scale information on the beneficial effects of interventions

15 Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, Hughes C, Lapane KL,

aimed at reducing harm from prescribing faults and pre- Swine C, Hanlon JT. Appropriate prescribing in elderly

scription errors is not yet available and is needed. people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet

2007; 370: 173–84.

Competing interests 16 Thomsen LA, Winterstein AG, Søndergaard B, Haugbølle LS,

Melander A. Systematic review of the incidence and

None to declare. characteristics of preventable adverse drug events in

ambulatory care. Ann Pharmacother 2007; 41: 1411–26.

17 Dean B. Learning from prescribing errors. Qual Saf Health

Care 2002; 11: 258–60.

REFERENCES 18 Leape LL. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 2002;

1 Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M. What is a prescribing error? 347: 1633–8.

Qual Health Care 2000; 9: 232–7.

19 Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, Forman-Hoffman VL, Levi BH,

2 Ferner RE, Aronson JK. Clarification of terminology in Rosenthal GE. Reporting medical errors to improve patient

medication errors: definitions and classification. Drug Saf safety: a survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Arch

2006; 29: 1011–22. Intern Med 2008; 168: 40–6.

Br J Clin Pharmacol / 67:6 / 627

G. Velo & P. Minuz

20 Jha AK, Kuperman GJ, Teich JM, Leape L, Shea B, influence of 10 years of serial audits and targeted

Rittenberg E, Burdick E, Seger DL, Vander Vliet M, Bates DW. interventions. Intern Med J 2008; 38: 243–8.

Identifying adverse drug events: development of a

computer-based monitor and comparison with chart review 25 Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, Burdick E, Demonaco HJ,

and stimulated voluntary report. J Am Med Inform Assoc Erickson JI, Bates DW. Pharmacist participation on physician

1998; 5: 305–14. rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit.

JAMA 1999; 282: 267–70.

21 Pollock M, Bazaldua OV, Dobbie AE. Appropriate prescribing

of medications: an eight-step approach. Am Fam Physician 26 Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyear L, Hall S, Wright D,

2007; 75: 231–6, 239–40. Loke YK. Does pharmacist-led medication review help to

reduce hospital admission and death in older people? A

22 Glasziou P, Irwig L, Aronson JK, eds. Evidence-based Medical systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol

Monitoring: From Principles to Practice. Oxford: 2007; 65: 303–16.

Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

27 Aronson JK, Henderson G, Webb DJ, Rawlins MD. A

23 Durieux P, Trinquart L, Colombet I, Niès J, Walton R, prescription for better prescribing. BMJ 2006; 333: 459–60.

Rajeswaran A, Rège Walther M, Harvey E, Burnand B.

Computerized advice on drug dosage to improve 28 Aronson JK. A prescription for better prescribing. Br J Clin

prescribing practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (3): Pharmacol 2006; 61: 487–91.

CD002894.

29 Thomas AN, Boxall EM, Laha SK, Day AJ, Grundy D. An

24 Gommans J, McIntosh P, Bee S, Allan W. Improving the educational and audit tool to reduce prescribing error in

quality of written prescriptions in a general hospital: the intensive care. Qual Saf Health Care 2008; 17: 360–3.

628 / 67:6 / Br J Clin Pharmacol

You might also like

- Test Bank For Oral Pharmacology For The Dental Hygienist 2nd Edition 2 e Mea A Weinberg Cheryl Westphal Theile James Burke FineDocument16 pagesTest Bank For Oral Pharmacology For The Dental Hygienist 2nd Edition 2 e Mea A Weinberg Cheryl Westphal Theile James Burke Finexavianhatmgzmz9No ratings yet

- Vol 51 No 2 01 Prevalence Med PDFDocument4 pagesVol 51 No 2 01 Prevalence Med PDFJustin VergaraNo ratings yet

- Oman Pharmacist Licensing Exam McqsDocument186 pagesOman Pharmacist Licensing Exam McqsMuhammad Amin100% (6)

- Lecture-09 Dose-Response RelationshipsDocument10 pagesLecture-09 Dose-Response RelationshipsChian WrightNo ratings yet

- PDF Manikanta J K TDocument60 pagesPDF Manikanta J K TSAURABH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Medication ErrorDocument7 pagesMedication ErrorLenny SucalditoNo ratings yet

- Medication ErrorDocument19 pagesMedication ErrorEvitaIrmayantiNo ratings yet

- WilliamsDocument4 pagesWilliamsRajesh KumarNo ratings yet

- MEdication ErrorsDocument6 pagesMEdication ErrorsBeaCeeNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors: What They Are, How They Happen, and How To Avoid ThemDocument9 pagesMedication Errors: What They Are, How They Happen, and How To Avoid ThemMoisesNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Pediatrics: PEDIATRICS Vol. 102 No. 2 August 1998Document5 pagesAmerican Academy of Pediatrics: PEDIATRICS Vol. 102 No. 2 August 1998Jemimah MejiaNo ratings yet

- Medication Safety: Mita Restinia, M.Farm, AptDocument57 pagesMedication Safety: Mita Restinia, M.Farm, Apt094DNORMINo ratings yet

- Medication Errors: P AperDocument4 pagesMedication Errors: P Aperdesk ayu okaNo ratings yet

- Social Pharmacy: Medication ErrorsDocument62 pagesSocial Pharmacy: Medication ErrorsEmmanuel KingsNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors in The United States and How To Improve Simple Mistakes 1Document7 pagesMedication Errors in The United States and How To Improve Simple Mistakes 1api-681331537No ratings yet

- Medication ErrorsDocument15 pagesMedication ErrorsShubhangi Sanjay KadamNo ratings yet

- Medication Error 2017Document51 pagesMedication Error 2017Christina100% (1)

- Medication SafetyDocument54 pagesMedication SafetyJuwitaASih100% (2)

- Medication ErrorsDocument10 pagesMedication Errorsjuliana bNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors Their Causative and Preventive Factors2.Doc 1Document11 pagesMedication Errors Their Causative and Preventive Factors2.Doc 1Mary MannNo ratings yet

- Figure 1. Indicator Framework of The Medication Error (Nerich Et Al., 2010)Document3 pagesFigure 1. Indicator Framework of The Medication Error (Nerich Et Al., 2010)balqiswulanNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors in Nursing 1Document6 pagesMedication Errors in Nursing 1Komal TanveerNo ratings yet

- The Epidemiology of Medication Errors: The Methodological DifficultiesDocument7 pagesThe Epidemiology of Medication Errors: The Methodological DifficultiesgabyvaleNo ratings yet

- Module 7: Medication Errors and Risk Reduction: Learning OutcomesDocument5 pagesModule 7: Medication Errors and Risk Reduction: Learning OutcomesShaina JavierNo ratings yet

- Med Errors OldDocument1 pageMed Errors OldAnonymous XvwKtnSrMRNo ratings yet

- TareDocument25 pagesTaremelkamu AssefaNo ratings yet

- Medication ErrorsDocument7 pagesMedication ErrorsNelly CheptooNo ratings yet

- The Assignment On Medication Errors in A Hospital & Some Examples of Adverse Reactions and Poisoning IncidencesDocument25 pagesThe Assignment On Medication Errors in A Hospital & Some Examples of Adverse Reactions and Poisoning IncidencesGroup Of Cheaters (ফাতরা)No ratings yet

- Medication Error in TemplateDocument5 pagesMedication Error in Templateapi-283173905No ratings yet

- 395-Main Article-1737-1-10-20210603Document11 pages395-Main Article-1737-1-10-20210603فاتن محمدNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors PaperDocument6 pagesMedication Errors Paperapi-542442476No ratings yet

- Ebp 1Document4 pagesEbp 1sabitaNo ratings yet

- Medication Error-Hisfarmasi PresentationDocument102 pagesMedication Error-Hisfarmasi PresentationLaura Khristiani MarbunNo ratings yet

- Medication Administration ErrorsDocument16 pagesMedication Administration ErrorspriyaNo ratings yet

- Medication Error PDFDocument61 pagesMedication Error PDFChelsea Ritz MendozaNo ratings yet

- E151 Medicationerrors-QJMDocument10 pagesE151 Medicationerrors-QJMRestu AriyusNo ratings yet

- Safe Administrations of Medications (Draft Chapter)Document74 pagesSafe Administrations of Medications (Draft Chapter)Caleb FellowesNo ratings yet

- Preventing Medication Error Based On Knowledge Management Against Adverse EventDocument9 pagesPreventing Medication Error Based On Knowledge Management Against Adverse EventJurnal Ners UNAIRNo ratings yet

- Common Prescribing ErrorsDocument3 pagesCommon Prescribing ErrorsNadial uzmahNo ratings yet

- ASHP Guidelines On Preventing Medication Errors in HospitalsDocument9 pagesASHP Guidelines On Preventing Medication Errors in HospitalsMedarabiaNo ratings yet

- Course: Patient Safety Solutions Topic:: Some DefinitionsDocument5 pagesCourse: Patient Safety Solutions Topic:: Some DefinitionsKian GonzagaNo ratings yet

- E151 Medicationerrors-QJMDocument10 pagesE151 Medicationerrors-QJMWens BambutNo ratings yet

- What We Need To Know For Patient SafetyDocument9 pagesWhat We Need To Know For Patient SafetyhusainiNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors PaperDocument6 pagesMedication Errors Paperapi-740209346No ratings yet

- Ch. 9Document4 pagesCh. 9Prince K. TaileyNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors 3Document6 pagesMedication Errors 3api-692972467No ratings yet

- The Percentage of Medication Errors Globally, and in Saudi ArabiaDocument7 pagesThe Percentage of Medication Errors Globally, and in Saudi ArabiaLeen alghamdNo ratings yet

- MedicationerrorsDocument11 pagesMedicationerrorsIkhwanir RaisaNo ratings yet

- Background. Registered Nurses (RNS) Have A Role in The Medication Administration ProcessDocument4 pagesBackground. Registered Nurses (RNS) Have A Role in The Medication Administration ProcessEdmarkmoises ValdezNo ratings yet

- 210 1437 1 PB LibreDocument62 pages210 1437 1 PB Librezozorina21No ratings yet

- ComplianceDocument13 pagesCompliancextremist2001No ratings yet

- Reducing Medication Risks of Electronic Medication Systems: Laura A. FinnDocument9 pagesReducing Medication Risks of Electronic Medication Systems: Laura A. FinnASHISH KUMAR YADAVNo ratings yet

- Attributable To The Use of Medications (: Near MissesDocument4 pagesAttributable To The Use of Medications (: Near MissesdudijohNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Medication Errors in Community Pharmacy Settings: A Retrospective ReportDocument4 pagesEvaluation of Medication Errors in Community Pharmacy Settings: A Retrospective ReportNicoleta CheptanariNo ratings yet

- RRL 8 Part 3Document55 pagesRRL 8 Part 3Joshua Christian Gan0% (1)

- Med Errors FinalDocument7 pagesMed Errors Finalapi-485620816No ratings yet

- Article Wjpps 1469869064Document10 pagesArticle Wjpps 1469869064Lucia SibiiNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument10 pagesCase StudyRezwan DihanNo ratings yet

- View of A Review On Adverse Drug Reactions Monitoring AndreportingDocument1 pageView of A Review On Adverse Drug Reactions Monitoring Andreporting9Asfara AzeezNo ratings yet

- Drug Errors: Consequences, Mechanisms, and Avoidance: Key PointsDocument7 pagesDrug Errors: Consequences, Mechanisms, and Avoidance: Key PointsRavikiran SuryanarayanamurthyNo ratings yet

- Abostrofic SytosisDocument17 pagesAbostrofic Sytosisasaad biqaiNo ratings yet

- Background: Frequency Relationship Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events Pharmacist's Role in Medication SafetyDocument3 pagesBackground: Frequency Relationship Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events Pharmacist's Role in Medication SafetyNono PapoNo ratings yet

- Pharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceFrom EverandPharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- List of WHO GMP Approved Manufacturers in Gujrat IndiaDocument28 pagesList of WHO GMP Approved Manufacturers in Gujrat IndiaRomana ZainNo ratings yet

- Who Trs 908-Annex9Document12 pagesWho Trs 908-Annex9Poorvi KumarNo ratings yet

- Drug Name Magnified Effects With AlcoholDocument1 pageDrug Name Magnified Effects With AlcoholMuhibpi IbrahimNo ratings yet

- DAFTAR ATC DDD ANTIBIOTIK WHO 2018 AbcDocument12 pagesDAFTAR ATC DDD ANTIBIOTIK WHO 2018 AbcMahezha DhewaNo ratings yet

- Código Descripción Costo Unita. Existencia Unidades Costo Existencia Precio 1 %utilDocument24 pagesCódigo Descripción Costo Unita. Existencia Unidades Costo Existencia Precio 1 %utilNiky Dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Eye Drops: Drug StudyDocument3 pagesEye Drops: Drug StudyChris PaguioNo ratings yet

- Mrs. Ailun P. Jaugan - BSN - BACTH 2024: PharmacologyDocument39 pagesMrs. Ailun P. Jaugan - BSN - BACTH 2024: Pharmacologytony montanNo ratings yet

- ScriptDocument2 pagesScriptNareshNo ratings yet

- Civic Drive, Filinvest City, Alabang 1781 Muntinlupa, PhilippinesDocument18 pagesCivic Drive, Filinvest City, Alabang 1781 Muntinlupa, Philippinesultimate_2226252No ratings yet

- Solid Dosage Form Part 1Document48 pagesSolid Dosage Form Part 1Claire Marie AlvaranNo ratings yet

- Stability StudiesDocument61 pagesStability StudiesSiddarth PalletiNo ratings yet

- BCS PrácticaDocument17 pagesBCS PrácticaEarvin GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Guideline 339 enDocument638 pagesGuideline 339 enJatin SinghNo ratings yet

- Nama Pasien Umur Waktu Tunggu Diagnosa No & TGL No. BpjsDocument18 pagesNama Pasien Umur Waktu Tunggu Diagnosa No & TGL No. BpjstriNo ratings yet

- Bourgoin Biologics MarketDocument29 pagesBourgoin Biologics Marketkohinoordas2007No ratings yet

- No. Nama Obat VEN Sediaan Harga Satuan JumlahDocument2 pagesNo. Nama Obat VEN Sediaan Harga Satuan Jumlahade rafniNo ratings yet

- Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology: Paul Baldrick, PHD Professor, Executive Director, Regulatory StrategyDocument6 pagesRegulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology: Paul Baldrick, PHD Professor, Executive Director, Regulatory StrategyPavanNo ratings yet

- Schedule yDocument11 pagesSchedule ySiva PrasadNo ratings yet

- LevocetirizineDocument3 pagesLevocetirizineAjayChandrakarNo ratings yet

- State Board of PharmacyDocument66 pagesState Board of PharmacyAnonymous hF5zAdvwCC100% (1)

- MarianoqueDocument8 pagesMarianoqueEunise Punzalan OprinNo ratings yet

- Blocked Stock 2100 140223Document22 pagesBlocked Stock 2100 140223Farmasi KenjeranNo ratings yet

- Medical Cannabis For Children Evidence and Recommendations Canadian Paediatric SocietyDocument22 pagesMedical Cannabis For Children Evidence and Recommendations Canadian Paediatric SocietyRegina de AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- MD Pharmacology Thesis TopicsDocument8 pagesMD Pharmacology Thesis Topicshqovwpaeg100% (1)

- DR - Joan Ramon Laporte 7feb2022Document6 pagesDR - Joan Ramon Laporte 7feb2022Heinz HurtigNo ratings yet

- Excipient Risk Assessment: Possible Approaches To Assessing The Risk Associated With Excipient FunctionDocument11 pagesExcipient Risk Assessment: Possible Approaches To Assessing The Risk Associated With Excipient FunctionKolisnykNo ratings yet

- Introduction and History of PharmacovigilanceDocument37 pagesIntroduction and History of PharmacovigilanceAmy Lon33% (3)