Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children in Emergency Department-Role of Adjunct Therapies

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children in Emergency Department-Role of Adjunct Therapies

Uploaded by

aryaharishalCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Eric Roman Coins PDFDocument2 pagesEric Roman Coins PDFBenNo ratings yet

- Penugasan Bahasa Inggris Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Matakuliah Bahasa Inggris Yang Dibina Oleh Ibu Eka Wulandari, S.PD., M.PDDocument14 pagesPenugasan Bahasa Inggris Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Matakuliah Bahasa Inggris Yang Dibina Oleh Ibu Eka Wulandari, S.PD., M.PDmufid dodyNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Strategi Coping Dengan Dispepsia Fungsional Pada Pasien Di Poliklinik Penyakit Dalam Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Wangaya DenpasarDocument6 pagesHubungan Strategi Coping Dengan Dispepsia Fungsional Pada Pasien Di Poliklinik Penyakit Dalam Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Wangaya DenpasarZilfiah LNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 14 1171661Document9 pagesFpsyt 14 1171661breiyaprouvellau-8047No ratings yet

- USA - A Pilot Project Using Pediatricians As Initial Diagnosticians in - 2018Document11 pagesUSA - A Pilot Project Using Pediatricians As Initial Diagnosticians in - 2018Karel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Fped 09 745212Document7 pagesFped 09 745212Nguyễn Trọng ThiệnNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric Research Ijpr 9 109Document4 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric Research Ijpr 9 109VsbshNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Infants - Children - AdolescentsDocument9 pagesPain Management in Infants - Children - AdolescentsOxana Turcu100% (1)

- Day Hospital Adolescence BeogradDocument3 pagesDay Hospital Adolescence BeogradBran KNo ratings yet

- Satisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesSatisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleVANESA REYESNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument26 pagesRetrievemarta_gasparNo ratings yet

- Original ArticlesDocument7 pagesOriginal ArticlesĐan TâmNo ratings yet

- E20190178 Full PDFDocument12 pagesE20190178 Full PDF2PlusNo ratings yet

- Prevention and Management of Procedural Pain in The Neonate An U 2016Document13 pagesPrevention and Management of Procedural Pain in The Neonate An U 2016Indra WijayaNo ratings yet

- Grissom2016 Article Play-basedProceduralPreparatioDocument7 pagesGrissom2016 Article Play-basedProceduralPreparatioFrancisco MartinezNo ratings yet

- Gengoux2019 PDFDocument12 pagesGengoux2019 PDFmartinfabyNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in ChildrenDocument9 pagesPain Management in ChildrenNASLY YERALDINE ZAPATA CATAÑONo ratings yet

- Determinants of Parent Delivered Therapy Interventions in Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Qualitative Synthesis and ChecklistDocument11 pagesDeterminants of Parent Delivered Therapy Interventions in Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Qualitative Synthesis and Checklistying reenNo ratings yet

- Adolescents DMT1Document8 pagesAdolescents DMT1Mia ValdesNo ratings yet

- Acute Pain Management in ChildrenDocument20 pagesAcute Pain Management in Childrenfuka priesleyNo ratings yet

- Family Centered Preparation For Surgery Improves.13Document10 pagesFamily Centered Preparation For Surgery Improves.13Laura GilNo ratings yet

- Author Response To We Need Precise Interventio 2021 American Journal of PreDocument2 pagesAuthor Response To We Need Precise Interventio 2021 American Journal of PreEstreLLA ValenciaNo ratings yet

- fitri 2021Document8 pagesfitri 2021Bambang RinandiNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngologyzaenal abidinNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Neurodevelopmental Treatment Based.3Document13 pagesEffects of A Neurodevelopmental Treatment Based.3ivairmatiasNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Attitudes of Pediatric Clinicians Regarding Pediatric Pain ManagementDocument11 pagesKnowledge and Attitudes of Pediatric Clinicians Regarding Pediatric Pain ManagementIkek StanzaNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument18 pagesDownloadying reenNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceDocument4 pagesEffectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceMarlisa LionoNo ratings yet

- Joi 140178Document11 pagesJoi 140178holisNo ratings yet

- Sucrose For Procedural Pain Management in Infants: AuthorsDocument10 pagesSucrose For Procedural Pain Management in Infants: AuthorsmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Policy On Pediatric Dental Pain ManagementDocument3 pagesPolicy On Pediatric Dental Pain ManagementمعتزباللهNo ratings yet

- Telepsychiatry AACAP 2017Document19 pagesTelepsychiatry AACAP 2017dominiakzsoltNo ratings yet

- Gomez Conesa2016Document1 pageGomez Conesa2016Maura Pilquiman MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- PIIS0882596321000488Document6 pagesPIIS0882596321000488Agus SubrataNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation For Children With Dysphagia - A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesNeuromuscular Electrical Stimulation For Children With Dysphagia - A Systematic ReviewJaviera PalmaNo ratings yet

- Akut DistoniaDocument5 pagesAkut DistoniaawendikaNo ratings yet

- Sedation and Analgesia in Children Undergoing Invasive ProceduresDocument7 pagesSedation and Analgesia in Children Undergoing Invasive ProceduresSantosa TandiNo ratings yet

- ContentServer AspDocument6 pagesContentServer AspchristyNo ratings yet

- Effects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisDocument4 pagesEffects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisMiguel TuriniNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Implementation of Pain Neuroscience Education: A Survey StudyDocument13 pagesThe Clinical Implementation of Pain Neuroscience Education: A Survey Studycookiepower54321No ratings yet

- Reduction of Perioperative Anxiety Using A Hand-Held Video Game DeviceDocument7 pagesReduction of Perioperative Anxiety Using A Hand-Held Video Game DeviceFiorel Loves EveryoneNo ratings yet

- Sexual & Reproductive HealthcareDocument7 pagesSexual & Reproductive HealthcareLindaNo ratings yet

- Sexual & Reproductive HealthcareDocument7 pagesSexual & Reproductive HealthcareYukdo AmbariNo ratings yet

- REAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Efektifitas Intervensi Psikoedukasi Terhadap Kepatuhan Berobat Pasien SkizofreniaDocument12 pagesREAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Efektifitas Intervensi Psikoedukasi Terhadap Kepatuhan Berobat Pasien SkizofreniaAHNAF MARUF MAHENDRANo ratings yet

- 2017-Psychological Interventions For Psychogenic Non Epileptic SeizuresDocument9 pages2017-Psychological Interventions For Psychogenic Non Epileptic SeizuresFidel ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal JurdingDocument11 pagesJurnal JurdingAqniettha Haarys BachdimNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Treatment in The Field of Child andDocument2 pagesEvidence-Based Treatment in The Field of Child andRayén F. HuenchunaoNo ratings yet

- Evidenced-Based Interventions For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument16 pagesEvidenced-Based Interventions For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDarahttbNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Paper For Summative EvaluationDocument9 pagesSynthesis Paper For Summative Evaluationapi-641561231No ratings yet

- ChayapathiDocument8 pagesChayapathiVINICIUS CAMARGO KISSNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Slow Deep Breathing On Pain Intensity in Children Through CircumcisionDocument8 pagesThe Effectiveness of Slow Deep Breathing On Pain Intensity in Children Through CircumcisionHarvina SindyNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Massage For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesThe Effectiveness of Massage For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewAl MukaramahNo ratings yet

- Dolor Crónico Infantily FTDocument13 pagesDolor Crónico Infantily FTmonicaNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Sedation An Analgesia in Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (ICU)Document7 pagesA Practical Guide To Sedation An Analgesia in Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (ICU)fuka priesleyNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Research: A A B A A C D A e F A G H A C BDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia Research: A A B A A C D A e F A G H A C BopanocayNo ratings yet

- Artigo - NeuroplasticidadeDocument26 pagesArtigo - NeuroplasticidadeGesiane SantosNo ratings yet

- (Journal Reading) A Randomized Trial of Adenotonsillectomy For Childhood Sleep ApneaDocument27 pages(Journal Reading) A Randomized Trial of Adenotonsillectomy For Childhood Sleep ApneaRizqon Yassir KuswondoNo ratings yet

- Wood 2022 Sensory GI Issues Ver PDFDocument9 pagesWood 2022 Sensory GI Issues Ver PDFcLAUDIANo ratings yet

- 2017 Locher - Antidepressants RS and MetaanalisisDocument10 pages2017 Locher - Antidepressants RS and MetaanalisisMaria Fernanda AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Advances in Critical Care Pediatric Nephrology: Point of Care Ultrasound and DiagnosticsFrom EverandAdvances in Critical Care Pediatric Nephrology: Point of Care Ultrasound and DiagnosticsSidharth Kumar SethiNo ratings yet

- Practical Treatment Options for Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents: An Interdisciplinary Therapy ManualFrom EverandPractical Treatment Options for Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents: An Interdisciplinary Therapy ManualNo ratings yet

- Herpes Zoster - Ofx007Document9 pagesHerpes Zoster - Ofx007aryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Hemorrhoid: Arief Aulia Rahman Pembimbing: Dr. Hj. Yanti Daryanti, SP.B-KBDDocument35 pagesHemorrhoid: Arief Aulia Rahman Pembimbing: Dr. Hj. Yanti Daryanti, SP.B-KBDaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study: Assessment of Spontaneous Retinal Arterial Pulsations in Acute Central Retinal Vein OcclusionsDocument5 pagesClinical Study: Assessment of Spontaneous Retinal Arterial Pulsations in Acute Central Retinal Vein OcclusionsaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus Kejang Demam Sederhana: Pembimbing: Dr. H. Jauhari Triwasito, Sp.ADocument1 pageLaporan Kasus Kejang Demam Sederhana: Pembimbing: Dr. H. Jauhari Triwasito, Sp.AaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Referat "Imunisasi": Pembimbing: Dr. Arief S. Ghazali, Sp.ADocument1 pageReferat "Imunisasi": Pembimbing: Dr. Arief S. Ghazali, Sp.AaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Experiment No. 3: Preparation of SoapDocument16 pagesExperiment No. 3: Preparation of SoapTrisha TadiosaNo ratings yet

- SLEN - August 2012Document12 pagesSLEN - August 2012Ashan FonsekaNo ratings yet

- Answers (Chapter 4)Document3 pagesAnswers (Chapter 4)Abhijit Singh100% (1)

- PicoStocks Business PlanDocument17 pagesPicoStocks Business PlanJignesh ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Light and Lens - P2Document37 pagesLight and Lens - P2Mustafa SalmanNo ratings yet

- Simplified Basic and Applied ResearchDocument2 pagesSimplified Basic and Applied ResearchMarwan ezz el dinNo ratings yet

- 1-Newton Second Law-ForMATDocument5 pages1-Newton Second Law-ForMATVAIBHAV KUMARNo ratings yet

- GAD Checklists 2: For The Project Identification and Design StagesDocument3 pagesGAD Checklists 2: For The Project Identification and Design StagesTago DinNo ratings yet

- IdealDocument8 pagesIdealAzza Sundus AntartikaNo ratings yet

- 5 Steps To Writing A Position Paper: ASSH2005Document2 pages5 Steps To Writing A Position Paper: ASSH2005KrishaNo ratings yet

- Technical Data Sheet: Elastic GunfoamDocument2 pagesTechnical Data Sheet: Elastic Gunfoams0n1907No ratings yet

- FA Doctrine and OrganizationDocument93 pagesFA Doctrine and OrganizationGreg JacksonNo ratings yet

- Micro Medical MicroLoop - Service ManualDocument14 pagesMicro Medical MicroLoop - Service Manualcharly floresNo ratings yet

- Pip Adg011-2018Document7 pagesPip Adg011-2018d-fbuser-93320248No ratings yet

- CV Rodrigo MorenoDocument4 pagesCV Rodrigo MorenoRodrigo MorenNo ratings yet

- Paper - 1983 - Vertical Flight Path and Speed Control Autopilot Design Using Total Energy Principles - Antonius A LambregtsDocument11 pagesPaper - 1983 - Vertical Flight Path and Speed Control Autopilot Design Using Total Energy Principles - Antonius A LambregtsSinggih Satrio WibowoNo ratings yet

- Kanhaiya PandeyDocument2 pagesKanhaiya Pandeypavankumarjatav9No ratings yet

- "I'm Your Number One Fan" A CLINICAL LOOK VWWDocument5 pages"I'm Your Number One Fan" A CLINICAL LOOK VWWfarhani afifahNo ratings yet

- Interpreting Multielement Geochemical Data: Scott Halley July 2015Document40 pagesInterpreting Multielement Geochemical Data: Scott Halley July 2015boby dwi herguariyanto supomoNo ratings yet

- Arcosolv® DPM Acetate: Material Safety Data SheetDocument8 pagesArcosolv® DPM Acetate: Material Safety Data SheettiagojjNo ratings yet

- Financial CompensationDocument55 pagesFinancial CompensationJerome TimolaNo ratings yet

- Iom2 User ManualDocument13 pagesIom2 User ManualBogdan Florin SpranceanaNo ratings yet

- 1509846749lecture 11. 2k14eee Signal Flow GraphDocument62 pages1509846749lecture 11. 2k14eee Signal Flow GraphAmin KhanNo ratings yet

- Challenges Ppt-CorporateDocument21 pagesChallenges Ppt-CorporateBabust AwsNo ratings yet

- English G-11 Handout, 2012Document52 pagesEnglish G-11 Handout, 2012Ebrahim KhedirNo ratings yet

- Mopo SimopsDocument1 pageMopo SimopsKamal DeshapriyaNo ratings yet

- S3-4 Rotameter 010113Document21 pagesS3-4 Rotameter 010113Shaik HabeebullahNo ratings yet

- Arnett (2006)Document4 pagesArnett (2006)Wulil AlbabNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 New MediaDocument6 pagesAssignment 2 New MediaJishan ShaikhNo ratings yet

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children in Emergency Department-Role of Adjunct Therapies

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children in Emergency Department-Role of Adjunct Therapies

Uploaded by

aryaharishalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children in Emergency Department-Role of Adjunct Therapies

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children in Emergency Department-Role of Adjunct Therapies

Uploaded by

aryaharishalCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Journal of Anesthesiology, 2017, 7, 371-380

http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojanes

ISSN Online: 2164-5558

ISSN Print: 2164-5531

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children

in Emergency Department—Role of Adjunct

Therapies

Nirupama Kannikeswaran1*, Ahmad Farooqi2, Cindy Chidi2, Deepak Kamat1

Carman and Ann Adam Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, MI, USA

1

Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA

2

How to cite this paper: Kannikeswaran, Abstract

N., Farooqi, A., Chidi2 C. and Kamat, D.

(2017) Procedural Sedation and Analgesia Objective: To compare sedation efficacy and parent/consultant satisfaction

in Children in Emergency Depart- between standard sedation, sedation with music listening, and sedation with

ment—Role of Adjunct Therapies. Open

Certified Child life Specialists (CCLS) in children undergoing procedural se-

Journal of Anesthesiology, 7, 371-380.

https://doi.org/10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 dation in the Pediatric Emergency Department (PED). Methods: Eligible

children, aged 3 - 18 years, were randomly allocated to one of 3 groups: 1)

Received: October 12, 2017 standard sedation; 2) sedation with music listening; 3) sedation with CCLS

Accepted: November 24, 2017

intervention. All 3 groups received intravenous ketamine. The child life group

Published: November 27, 2017

received age appropriate comforting measures, while the music group listened

Copyright © 2017 by authors and to music of their choice during the procedure. The primary outcome was se-

Scientific Research Publishing Inc. dation efficacy, measured by Ramsay Sedation scale, FACES-P scale and need

This work is licensed under the Creative

for re-dosing. The secondary outcome was parent/consultant satisfaction.

Commons Attribution International

License (CC BY 4.0). Results: Fifty nine patients were analyzed (standard sedation: 20; sedation

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ with music listening: 20; and sedation with CCLS: 19). There was no signifi-

Open Access cant difference in mean initial ketamine dosing (1.58 ± 0.44 vs. 1.68 ± 0.36 vs.

1.42 ± 0.47, p = 0.26). There was no significant difference in median Ramsay

Sedation scores [6(IQR:4,6) vs. 6 (IQR:4,6) vs. 6 (IQR:5,6)], FACES-R pain

score [0 (IQR:0.0) vs. 0 (IQR:0.0) vs. 0 (IQR:0.0)] and need for re-dosing [9/20

(45%) vs. 4/20 (20%) vs. 8/19 (42.1%)] amongst the 3 groups. Parent and

consultant satisfaction was high in all 3 groups. Conclusion: Our pilot study did

not demonstrate a difference in sedation efficacy or parent/consultant satisfac-

tion when adjunct therapies were used during PSA. Further studies with a

large sample size are needed to define the role for such adjunct therapies dur-

ing procedural sedation in PED.

Keywords

Procedural Sedation, Music Therapy, Certified Child Life Specialists, Emergency

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 Nov. 27, 2017 371 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

Department, Children

1. Introduction

Providing pain relief associated with diagnostic and therapeutic procedures is an

ethical requirement in children. Additionally, it is measured as a quality of care

component from the perspective of family for Pediatric Emergency Department

(PED) visit. Procedural Sedation and Analgesia (PSA) is increasingly being used

in the PED to relieve children of pain, stress and anxiety during painful and un-

pleasant procedures while maintaining an adequate cardiorespiratory function.

While serious adverse events are rare, PSA is associated with adverse events

primarily affecting airway and respiratory system, in a small subset of patients

[1]. Furthermore, PSA can entail obtaining an intravenous access which by itself

is a painful procedure. Hence, it is important to study the role of non-invasive

modalities in reduction of pain and anxiety in children undergoing painful pro-

cedures in the PED.

Certified Child Life Specialists (CCLS) are formally trained professionals who

establish therapeutic relationships with pediatric patients by presenting age ap-

propriate information on procedures, providing play experiences and comfort-

ing measures as well as helping children and their families cope with anxiety and

the stresses of being in the hospital. They have been shown to reduce behavioral

stress during painful procedures in the ED [2] [3], but their role during PSA has

not been well defined. Music therapy’s capacity to decrease levels of stress, an-

xiety, and pain in patients is well documented in various health care settings [4]

[5] [6]. Furthermore, it has been shown to decrease patient’s requirements in

sedative and analgesic needs [7] [8]. However, the role of music therapy as an

adjunct to PSA in the PED has not been studied.

The objective of our study was to compare the sedation efficacy as well as

consultant and parental satisfaction between standard sedation, standard seda-

tion with music listening, and standard sedation with CCLS intervention in

children who undergo PSA in the PED for painful (orthopedic, laceration repair,

incision and drainage) procedures.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a prospective randomized control trial of standard sedation vs.

standard sedation with child life intervention vs. standard sedation with music

listening in children aged 3 to 18 years of age who required IV ketamine for PSA

for orthopedic procedures, laceration repairs and incision and drainage of ab-

scess (I & D) in a PED over a one period from October 2015-2016. Our PED is a

level 1 trauma center attached to a free-standing children’s hospital with 92,000

patient visits annually. Of these, approximately 1200 children receive PSA for

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 372 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

painful procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or

legal guardian of the patient. In addition, an assent was collected from all child-

ren > 7 years of age. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board

(IRB). The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT02518919.

2.2. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Children between the ages of 3 to 18 years with American Society of Anesthesi-

ologists (ASA) classification I or II [9] who required IV ketamine for PSA for

orthopedic procedures, I & D of skin abscess and laceration repair were eligible

for participation in the study. We enrolled a convenience sample of eligible pa-

tients based on availability of the research assistants and child life personnel.

Study participants were identified using an electronic medical tracking board,

which lists the presenting complaint and after the need for PSA with IV keta-

mine was established by the research assistant with the treating physician.

We excluded the following patients from the study:

1) Children with known allergy to or contraindications to use of ketamine;

2) Children who received intramuscular, intranasal or oral sedation or sedation

medications other than ketamine;

3) Those who had experienced previous adverse events with ketamine;

4) Those who receive sedation for procedures not listed in the inclusion criteria;

5) Those who are outside the age range listed above;

6) Those whose parent or legal guardian was not available or declined to provide

informed consent for the study, or if the child declined to provide assent.

2.3. Study Interventions

Study subjects were randomized into 3 groups: 1) standard sedation; 2) standard

sedation with music listening; 3) standard sedation with CCLS intervention.

Randomization was performed by a pharmacist from the Investigational Drug

Section of the Pharmacy Department via a computer generated random number

table. The study research assistant would assign the patient to the randomization

group by opening a sealed envelope after informed consent was obtained.

For study subjects assigned to the standard sedation with CCLS intervention

group, trained child life personnel introduced the procedure to the child and

family. The child life specialist also provided comforting measures appropriate

to the age of the patient and according to the patient’s and family’s preference

during the placement of intravenous line and throughout the procedure. The

child life specialist also explained the procedure to the child using a teaching doll

and real as well pretend medical equipment. There are two child life specialists

who work in our PED from 3 pm - midnight during the weekdays.

Those study subjects assigned to the music listening arm were asked to select

music of their choice. We felt that the music listening intervention would be

more effective if the patient was allowed to listen to the music of their choice ra-

ther than to preselected music. The patient listened to the music of their choice

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 373 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

downloaded using icloud via ipad using headphones during the placement of

intravenous line as well as during the entire procedure. The study research as-

sistant pre set the volume of music to be the same level for all study patients.

The family was allowed to stay with their child during the procedure and in-

teract with the child for all the three study groups based on their choice.

Children enrolled in the study received sedation after a pre-sedation assess-

ment using current institutional guidelines as applied to all PED sedation pa-

tients. Patients were monitored using published sedation guidelines with mea-

surements of vital signs and pulse oximetry at baseline, every 5 minutes during

the procedure and post procedure for the entire duration of sedation. The dose

of sedation medication administered was left to the discretion of the sedation

physician. The research team neither participated nor intervened during the se-

dation or with the clinical care of the patient. The research assistant however

observed the sedation and recorded the sedation depth and pain scores during

and after the sedation.

2.4. Study Measurements

The following variables were collected by a trained research assistant: patient

demographics, eligible procedure type, NPO status, ASA classification, type and

dose of pain medication administered prior to sedation, initial ketamine dosing

in mg/kg, need for re-dosing, sedation related adverse events, interventions per-

formed to overcome adverse events and ED disposition. Sedation related adverse

events were defined using the standardized definitions provided by the Quebec

Guidelines for ED sedation terminology and reporting of adverse events in

children [10].

The trained research assistant documented sedation efficacy using the Ramsay

Sedation Scale [11] and at the following time points:

• Pre-sedation (three minutes prior to study drug administration);

• During the procedure (after ketamine administration and prior to and after

any re-dosing);

• Post sedation (prior to discharge).

Severity of pain was assessed using Faces Pain Scale [12] on a scale of 0 - 10 (0:

no pain - 10: most pain, respectively) during three time points mentioned above.

During sedation, pain severity was determined by the research assistant using

the patient’s facial expression and/or response. No facial expression and/or lack

of response throughout the sedation were scored as zero. Pre- and post-sedation

pain severity were self-assessed using a verbal response from the study subjects.

In addition, a 3-point Likert scale (not satisfied, satisfied, or very satisfied with

the sedation) was used to assess sedation efficacy by the parent as well as the

physician performing the procedure.

2.5. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure for this study was the sedation efficacy as meas-

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 374 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

ured by Ramsay Sedation scale, FACES-P scale during sedation and the number

of additional doses of ketamine administered to achieve adequate sedation. The

secondary outcome measure was consultant and parent satisfaction using Likert

scale.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A database and coding scheme were created using Excel® to host all data col-

lected for this study. The research assistant performed double data entry to veri-

fy accuracy. Categorical data was analyzed and reported using numbers and percen-

tages. The normality of continuous scaled data was tested by Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test and reported using mean and standard deviation, whereas non-normally

distributed continuous data are reported by median and inter quartile range.

Pearson’s Chi-squared Test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the distri-

bution of categorical data by groups. Comparisons of two or more normal con-

tinuous variables is conducted using Student t test and ANOVA respectively,

whereas non-normally distributed continuous variables are compared using the

Wilcoxon rank sum test and Kruskal-Wallis (ANOVA for ranks) tests. We used

SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, North Carolina) to perform statistical

analyses. Significance level was set at 0.05. Since this was a pilot study, we did

not perform a power analysis or sample size calculation.

3. Results

A total of 419 patients underwent PSA in the PED during the study period. Of

these, 356 patients were excluded and 63 patients were randomized for the study

as follows: standard sedation (n = 21), standard sedation with music listening (n

= 21) and standard sedation with CCLS intervention (n = 21). Protocol violation

occurred in 4 patients. Two of these patients were assigned to the CCLS inter-

vention group but the child life personnel were unavailable. In two other pa-

tients, the sedation physician and the mother requested the presence of CCLS

during sedation though these patients were assigned to standard sedation and

standard sedation with music listening respectively. These four patients were ex-

cluded from the final study analysis (Figure 1).

There was a higher proportion of girls in the child life group but there was no

difference in race and ethnicity, ASA classification, indication for PSA, adminis-

tration of pre procedural pain medication amongst the study three groups

(Table 1). There was no significant difference in the mean initial dose of IV ke-

tamine (1.58 ± 0.44 vs. 1.68 ± 0.36 vs. 1.42 ± 0.47; p = 0.26) or the proportion of

children who required re-dosing amongst the 3 groups [9/20 (45%) vs. 4/20

(20%) vs. 8/19 (42.1%)] (Figure 2).

There was no difference in the median Ramsay Sedation scores [6 (IQR:4.6)

vs. 6 (IQR:4.6) vs. 6 (IQR:5.6)] and FACES-R score [0 (IQR:0.0) vs. 0 (IQR:0.0)

vs. 0 (IQR:0.0)] during sedation between the three groups. A higher proportion

of children experienced adverse event secondary to vomiting in the music listening

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 375 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

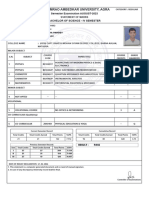

Table 1. Patient demographics of the three study groups.

Standard sedation Standard sedation with Standard sedation

Variable p value

n = 20 music listening = 20 with CCLS n = 19

Age Median, IQR 5.0 (4.5, 9.5) 8.5 (6.5, 11.0) 9.0 (6.0, 11.0) 0.12

Male 12 14 6

Gender 0.04

Female 8 6 13

African American 12 9 10

Caucasian 4 9 3

Race Asian 2 1 3 0.12

Mixed 0 1 0

Other 2 0 3

Hispanic 2 0 2

Ethnicity 0.45

Non-Hispanic 18 20 17

I 16 15 16

ASA 0.92

II 4 5 3

Fracture/dislocation reduction 12 16 13

Procedure type Incision and drainage 1 1 2 0.80

Laceration repair 7 3 4

Pre-sedation pain Yes (Any) 14 10 14

0.25

medications No 6 10 5

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 376 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

Figure 2. Mean initial dosing of ketamine and need for re-dosing amongst the three study groups.

group but the difference was not statistically significant [3/29 (15%) vs. 8/20

(40%) vs. 3/19 (15.8%), p = 0.12]. The most common adverse event was vomit-

ing in all 3 groups. Three children experienced oxygen desaturation, one in

standard sedation group and two in child life group.

Consultants were either “satisfied” [13/20 (65%) vs. 8/20 (40%) vs. 6/19

(31.6%)] or “very satisfied” with the sedation [7/20 (35%) vs. 12/20 (60%) vs.

13/19 (68.4%); p = 0.09]. Parental satisfaction was similarly high (satisfied or

very satisfied) in the 3 groups [20/20 (100%) vs. 19/20 (95%) vs. 18/19 (94.7%); p

= 0.12].

4. Discussion

Non-pharmacological interventions are an integral part of pain management in

the PED along with pain medications. Unlike pharmacological interventions,

non-pharmacological interventions have the advantage of lack of adverse events,

being able to be tailored to the needs of the particular child as well as providing

the patient with a sense of control. Child life intervention and music therapy are

two such non-pharmacologic interventions which have been shown to have a

positive impact on pain and distress in children. While previous studies have

evaluated the efficacy of such interventions in reducing pain and anxiety asso-

ciated with procedures in children, ours is the first study to our knowledge to

evaluate the effects of these interventions on sedation medication requirements

and sedation efficacy in a PED.

Scott et al. [13] evaluating the effectiveness of CCLS on the frequency of use of

daily anesthesia in a pediatric oncology unit showed an absolute reduction of

16% in children aged 3 to 12 years with a significant reduction from 62.3% to

28.8% in children aged 5 to 8 years of age. Another study showed that the insti-

tution of mandatory child life consultation in a Magnetic Resonance Imaging

suite led to avoidance of general anesthesia in 102 patients during a one year in-

tervention period with the avoidance of sedation being particularly significant in

the older age group of children between 5 to 10 years [14]. In a systematic review

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 377 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of music therapy in children un-

dergoing clinical procedures, Klassen et al. [15] showed that music therapy re-

sulted in a significant reduction in pain and anxiety and concluded that it may

be considered as an adjunct therapy during painful procedures. Walworth et al.

[16] examined the cost effectiveness of music therapy as procedural adjunct for

computerized tomograms, echocardiograms and other procedures and con-

cluded that music therapy-assisted procedures resulted in successful elimination

of sedation, reduction in procedural times and decrease in the number of staff

members present for the procedures.

Previous studies have shown higher parent and physician satisfaction scores

and a lower perception of child’s pain and distress with increased patient coop-

eration and ease of performance of procedure with CCLS intervention and mu-

sic therapy compared to standard intervention [6] [17]. While our study did not

demonstrate a difference in satisfaction or pain scores amongst the three groups

perhaps due to the small sample size, it did show high satisfaction scores in both

the intervention groups.

Non-pharmacologic adjuncts play a crucial role in improving the preparation,

coping and adjustment of the child to painful procedure and therefore should be

offered to families and children along with pharmacologic interventions. Further,

passive music therapy which was used in our study is relatively easy to implement

and is not limited by availability of trained personnel. Such non-pharmacologic

approaches should be integrated into clinical care along with procedural seda-

tion to create a pain-free environment for children in PED.

5. Limitations

Our study has several limitations. We enrolled a convenience sample of eligible

patients based on availability of research assistants and child life personnel. The

sample size was small as this was a pilot study. There were protocol violations in

four study patients who were excluded from the final analysis. Study subjects

chose the music of their own choice which meant that there were different

forms of music that they listened to during the procedure. We did not control

for this difference in our analysis. The study could not be blinded for obvious

reasons. We did not randomize study patients by the procedure type, which

could have confounded the sedation medication dose. However, the majority

of patients enrolled in all three study groups underwent PSA for orthopedic

procedures.

6. Conclusion

Our pilot study demonstrates a role for adjunct therapies such as child life ther-

apy and music listening during PSA in children in the ED. Further studies with a

larger sample size are needed to evaluate if such adjunct therapies can reduce the

sedation medication dose or eliminate the need for intravenous sedation for cer-

tain procedures in the ED.

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 378 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of CCLS Steven Rubinstein and

Laura Walker as well as research assistant Isadora Porter for their role in partic-

ipation and recruitment of patients for the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source of Funding

This study was funded by the Children’s Hospital of Michigan Foundation

Grant, R1-2014-79.

References

[1] Cravero, J.P., Blike, G.T., Beach, M.L., et al. (2006) Pediatric Sedation Research

Consortium. Incidence and Nature of Adverse Events during Pediatric Seda-

tion/Anesthesia for Procedures outside the Operating Room: Report from the Pe-

diatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatrics, 118, 1087-1096.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-0313

[2] Stevenson, M., Bivins, C., O’Brien, K., et al. (2005) Child Life Intervention during

Angiocatheter Insertion in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatric Emer-

gency Care, 21, 712-718. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pec.0000186423.84764.5a

[3] Alcock, D.S., Feldman, W., Goodman, J.T., et al. (1985) Evaluation of Child Life In-

tervention in Emergency Department Suturing. Pediatric Emergency Care, 1,

111-115. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006565-198509000-00001

[4] Evans, D. (2002) The Effectiveness of Music as an Intervention for Hospital Pa-

tients: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37, 8-18.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02052.x

[5] Klassen, J.A., Liang, Y., Tjosvold, L., Klassen, T.P. and Hartling, L. (2008) Music for

Pain and Anxiety in Children Undergoing Medical Procedures: A Systematic Re-

view of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 8, 117-128.

[6] Hartling, S., Newton, A.S., Liang, Y., et al. (2013) Music to Reduce Pain and Distress

in the Pediatric Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA

Pediatrics, 167, 826-835. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.200

[7] Lepage, C., Drolet, P., Girard, M., et al. (2001) Music Decreases Sedative Require-

ments during Spinal Anesthesia. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 93, 912-916.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200110000-00022

[8] Koch, M.E., Kain, Z.N., Ayoub, C., et al. (1998) The Sedative and Anlgesic Sparing

Effects of Music. Anesthesiology, 89, 300-306.

[9] American Society of Anesthesiologists (1963) New Classification of Physical Status.

Anesthesiology, 24, 111.

[10] Bhatt, M., Kennedy, R.M., Osmond, M.H., et al. (2009) Consensus Panel on Seda-

tion Research of Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) and the Pediatric

Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Consensus-Based Recom-

mendations for Standardizing Terminology and Reporting Adverse Events for

Emergency Department Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Children. Annals of

Emergency Medicine, 53, 426-435.

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 379 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

N. Kannikeswaran et al.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.09.030

[11] De Jonghe, B., Cook, D., Appere-DeVecchi, C., Guyatt, G., Meade, M. and Outin,

H. (2000) Using and Understanding Sedation Scoring Systems: A Systematic Re-

view. Intensive Care Medicine, 26, 275-285.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340051150

[12] Bieri, D., Reeve, R.A., Champion, G.D., et al. (1990) The Faces Pain Scale for the

Self-Assessment of the Severity of Pain Experienced by Children: Development Ini-

tial Validation, and Preliminary Investigation for Ratio Scale Properties. Pain, 41,

139-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(90)90018-9

[13] Scott, M.T., Todd, K.E., Oakley, H., et al. (2016) Reducing Anesthesia and Health

Care Cost through Utilization of Child Life Specialists in Pediatric Radiation On-

cology. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 96, 401-405.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.06.001

[14] Durand, D.J., Young, M., Nagy, P., et al. (2015) Mandatory Child Life Consultation

and Its Impact on Pediatric MRI Workflow in an Academic Medical Center. Journal

of the American College of Radiology, 12, 594-598.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2014.12.015

[15] Klassen, J.A., Liang, Y., Tjosvold, L., et al. (2008) Music for Pain and Anxiety in

Children Undergoing Medical Procedures: A Systematic Review of Randomized

Controlled Trials. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 8, 117-128.

[16] Walworth, D.D. (2005) Procedural-Support Music Therapy in the Healthcare Set-

ting: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 20, 276-284.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2005.02.016

[17] Tyson, M.E., Bohl, D.D. and Blickman, J.G. (2014) A Randomized Controlled Trial:

Child Life Services in Pediatric Imaging. Pediatric Radiology, 44, 1426-1432.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-014-3005-1

Abbreviations

PED: Pediatric Emergency Department

PSA: Procedural Sedation and Analgesia

CCLS: Certified Child Life Specialists

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.711038 380 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

You might also like

- Eric Roman Coins PDFDocument2 pagesEric Roman Coins PDFBenNo ratings yet

- Penugasan Bahasa Inggris Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Matakuliah Bahasa Inggris Yang Dibina Oleh Ibu Eka Wulandari, S.PD., M.PDDocument14 pagesPenugasan Bahasa Inggris Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Matakuliah Bahasa Inggris Yang Dibina Oleh Ibu Eka Wulandari, S.PD., M.PDmufid dodyNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Strategi Coping Dengan Dispepsia Fungsional Pada Pasien Di Poliklinik Penyakit Dalam Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Wangaya DenpasarDocument6 pagesHubungan Strategi Coping Dengan Dispepsia Fungsional Pada Pasien Di Poliklinik Penyakit Dalam Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Wangaya DenpasarZilfiah LNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 14 1171661Document9 pagesFpsyt 14 1171661breiyaprouvellau-8047No ratings yet

- USA - A Pilot Project Using Pediatricians As Initial Diagnosticians in - 2018Document11 pagesUSA - A Pilot Project Using Pediatricians As Initial Diagnosticians in - 2018Karel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Fped 09 745212Document7 pagesFped 09 745212Nguyễn Trọng ThiệnNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric Research Ijpr 9 109Document4 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric Research Ijpr 9 109VsbshNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Infants - Children - AdolescentsDocument9 pagesPain Management in Infants - Children - AdolescentsOxana Turcu100% (1)

- Day Hospital Adolescence BeogradDocument3 pagesDay Hospital Adolescence BeogradBran KNo ratings yet

- Satisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesSatisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleVANESA REYESNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument26 pagesRetrievemarta_gasparNo ratings yet

- Original ArticlesDocument7 pagesOriginal ArticlesĐan TâmNo ratings yet

- E20190178 Full PDFDocument12 pagesE20190178 Full PDF2PlusNo ratings yet

- Prevention and Management of Procedural Pain in The Neonate An U 2016Document13 pagesPrevention and Management of Procedural Pain in The Neonate An U 2016Indra WijayaNo ratings yet

- Grissom2016 Article Play-basedProceduralPreparatioDocument7 pagesGrissom2016 Article Play-basedProceduralPreparatioFrancisco MartinezNo ratings yet

- Gengoux2019 PDFDocument12 pagesGengoux2019 PDFmartinfabyNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in ChildrenDocument9 pagesPain Management in ChildrenNASLY YERALDINE ZAPATA CATAÑONo ratings yet

- Determinants of Parent Delivered Therapy Interventions in Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Qualitative Synthesis and ChecklistDocument11 pagesDeterminants of Parent Delivered Therapy Interventions in Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Qualitative Synthesis and Checklistying reenNo ratings yet

- Adolescents DMT1Document8 pagesAdolescents DMT1Mia ValdesNo ratings yet

- Acute Pain Management in ChildrenDocument20 pagesAcute Pain Management in Childrenfuka priesleyNo ratings yet

- Family Centered Preparation For Surgery Improves.13Document10 pagesFamily Centered Preparation For Surgery Improves.13Laura GilNo ratings yet

- Author Response To We Need Precise Interventio 2021 American Journal of PreDocument2 pagesAuthor Response To We Need Precise Interventio 2021 American Journal of PreEstreLLA ValenciaNo ratings yet

- fitri 2021Document8 pagesfitri 2021Bambang RinandiNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngologyzaenal abidinNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Neurodevelopmental Treatment Based.3Document13 pagesEffects of A Neurodevelopmental Treatment Based.3ivairmatiasNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Attitudes of Pediatric Clinicians Regarding Pediatric Pain ManagementDocument11 pagesKnowledge and Attitudes of Pediatric Clinicians Regarding Pediatric Pain ManagementIkek StanzaNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument18 pagesDownloadying reenNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceDocument4 pagesEffectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceMarlisa LionoNo ratings yet

- Joi 140178Document11 pagesJoi 140178holisNo ratings yet

- Sucrose For Procedural Pain Management in Infants: AuthorsDocument10 pagesSucrose For Procedural Pain Management in Infants: AuthorsmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Policy On Pediatric Dental Pain ManagementDocument3 pagesPolicy On Pediatric Dental Pain ManagementمعتزباللهNo ratings yet

- Telepsychiatry AACAP 2017Document19 pagesTelepsychiatry AACAP 2017dominiakzsoltNo ratings yet

- Gomez Conesa2016Document1 pageGomez Conesa2016Maura Pilquiman MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- PIIS0882596321000488Document6 pagesPIIS0882596321000488Agus SubrataNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation For Children With Dysphagia - A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesNeuromuscular Electrical Stimulation For Children With Dysphagia - A Systematic ReviewJaviera PalmaNo ratings yet

- Akut DistoniaDocument5 pagesAkut DistoniaawendikaNo ratings yet

- Sedation and Analgesia in Children Undergoing Invasive ProceduresDocument7 pagesSedation and Analgesia in Children Undergoing Invasive ProceduresSantosa TandiNo ratings yet

- ContentServer AspDocument6 pagesContentServer AspchristyNo ratings yet

- Effects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisDocument4 pagesEffects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisMiguel TuriniNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Implementation of Pain Neuroscience Education: A Survey StudyDocument13 pagesThe Clinical Implementation of Pain Neuroscience Education: A Survey Studycookiepower54321No ratings yet

- Reduction of Perioperative Anxiety Using A Hand-Held Video Game DeviceDocument7 pagesReduction of Perioperative Anxiety Using A Hand-Held Video Game DeviceFiorel Loves EveryoneNo ratings yet

- Sexual & Reproductive HealthcareDocument7 pagesSexual & Reproductive HealthcareLindaNo ratings yet

- Sexual & Reproductive HealthcareDocument7 pagesSexual & Reproductive HealthcareYukdo AmbariNo ratings yet

- REAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Efektifitas Intervensi Psikoedukasi Terhadap Kepatuhan Berobat Pasien SkizofreniaDocument12 pagesREAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Efektifitas Intervensi Psikoedukasi Terhadap Kepatuhan Berobat Pasien SkizofreniaAHNAF MARUF MAHENDRANo ratings yet

- 2017-Psychological Interventions For Psychogenic Non Epileptic SeizuresDocument9 pages2017-Psychological Interventions For Psychogenic Non Epileptic SeizuresFidel ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal JurdingDocument11 pagesJurnal JurdingAqniettha Haarys BachdimNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Treatment in The Field of Child andDocument2 pagesEvidence-Based Treatment in The Field of Child andRayén F. HuenchunaoNo ratings yet

- Evidenced-Based Interventions For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument16 pagesEvidenced-Based Interventions For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDarahttbNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Paper For Summative EvaluationDocument9 pagesSynthesis Paper For Summative Evaluationapi-641561231No ratings yet

- ChayapathiDocument8 pagesChayapathiVINICIUS CAMARGO KISSNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Slow Deep Breathing On Pain Intensity in Children Through CircumcisionDocument8 pagesThe Effectiveness of Slow Deep Breathing On Pain Intensity in Children Through CircumcisionHarvina SindyNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Massage For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesThe Effectiveness of Massage For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewAl MukaramahNo ratings yet

- Dolor Crónico Infantily FTDocument13 pagesDolor Crónico Infantily FTmonicaNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Sedation An Analgesia in Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (ICU)Document7 pagesA Practical Guide To Sedation An Analgesia in Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (ICU)fuka priesleyNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Research: A A B A A C D A e F A G H A C BDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia Research: A A B A A C D A e F A G H A C BopanocayNo ratings yet

- Artigo - NeuroplasticidadeDocument26 pagesArtigo - NeuroplasticidadeGesiane SantosNo ratings yet

- (Journal Reading) A Randomized Trial of Adenotonsillectomy For Childhood Sleep ApneaDocument27 pages(Journal Reading) A Randomized Trial of Adenotonsillectomy For Childhood Sleep ApneaRizqon Yassir KuswondoNo ratings yet

- Wood 2022 Sensory GI Issues Ver PDFDocument9 pagesWood 2022 Sensory GI Issues Ver PDFcLAUDIANo ratings yet

- 2017 Locher - Antidepressants RS and MetaanalisisDocument10 pages2017 Locher - Antidepressants RS and MetaanalisisMaria Fernanda AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Advances in Critical Care Pediatric Nephrology: Point of Care Ultrasound and DiagnosticsFrom EverandAdvances in Critical Care Pediatric Nephrology: Point of Care Ultrasound and DiagnosticsSidharth Kumar SethiNo ratings yet

- Practical Treatment Options for Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents: An Interdisciplinary Therapy ManualFrom EverandPractical Treatment Options for Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents: An Interdisciplinary Therapy ManualNo ratings yet

- Herpes Zoster - Ofx007Document9 pagesHerpes Zoster - Ofx007aryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Hemorrhoid: Arief Aulia Rahman Pembimbing: Dr. Hj. Yanti Daryanti, SP.B-KBDDocument35 pagesHemorrhoid: Arief Aulia Rahman Pembimbing: Dr. Hj. Yanti Daryanti, SP.B-KBDaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study: Assessment of Spontaneous Retinal Arterial Pulsations in Acute Central Retinal Vein OcclusionsDocument5 pagesClinical Study: Assessment of Spontaneous Retinal Arterial Pulsations in Acute Central Retinal Vein OcclusionsaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus Kejang Demam Sederhana: Pembimbing: Dr. H. Jauhari Triwasito, Sp.ADocument1 pageLaporan Kasus Kejang Demam Sederhana: Pembimbing: Dr. H. Jauhari Triwasito, Sp.AaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Referat "Imunisasi": Pembimbing: Dr. Arief S. Ghazali, Sp.ADocument1 pageReferat "Imunisasi": Pembimbing: Dr. Arief S. Ghazali, Sp.AaryaharishalNo ratings yet

- Experiment No. 3: Preparation of SoapDocument16 pagesExperiment No. 3: Preparation of SoapTrisha TadiosaNo ratings yet

- SLEN - August 2012Document12 pagesSLEN - August 2012Ashan FonsekaNo ratings yet

- Answers (Chapter 4)Document3 pagesAnswers (Chapter 4)Abhijit Singh100% (1)

- PicoStocks Business PlanDocument17 pagesPicoStocks Business PlanJignesh ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Light and Lens - P2Document37 pagesLight and Lens - P2Mustafa SalmanNo ratings yet

- Simplified Basic and Applied ResearchDocument2 pagesSimplified Basic and Applied ResearchMarwan ezz el dinNo ratings yet

- 1-Newton Second Law-ForMATDocument5 pages1-Newton Second Law-ForMATVAIBHAV KUMARNo ratings yet

- GAD Checklists 2: For The Project Identification and Design StagesDocument3 pagesGAD Checklists 2: For The Project Identification and Design StagesTago DinNo ratings yet

- IdealDocument8 pagesIdealAzza Sundus AntartikaNo ratings yet

- 5 Steps To Writing A Position Paper: ASSH2005Document2 pages5 Steps To Writing A Position Paper: ASSH2005KrishaNo ratings yet

- Technical Data Sheet: Elastic GunfoamDocument2 pagesTechnical Data Sheet: Elastic Gunfoams0n1907No ratings yet

- FA Doctrine and OrganizationDocument93 pagesFA Doctrine and OrganizationGreg JacksonNo ratings yet

- Micro Medical MicroLoop - Service ManualDocument14 pagesMicro Medical MicroLoop - Service Manualcharly floresNo ratings yet

- Pip Adg011-2018Document7 pagesPip Adg011-2018d-fbuser-93320248No ratings yet

- CV Rodrigo MorenoDocument4 pagesCV Rodrigo MorenoRodrigo MorenNo ratings yet

- Paper - 1983 - Vertical Flight Path and Speed Control Autopilot Design Using Total Energy Principles - Antonius A LambregtsDocument11 pagesPaper - 1983 - Vertical Flight Path and Speed Control Autopilot Design Using Total Energy Principles - Antonius A LambregtsSinggih Satrio WibowoNo ratings yet

- Kanhaiya PandeyDocument2 pagesKanhaiya Pandeypavankumarjatav9No ratings yet

- "I'm Your Number One Fan" A CLINICAL LOOK VWWDocument5 pages"I'm Your Number One Fan" A CLINICAL LOOK VWWfarhani afifahNo ratings yet

- Interpreting Multielement Geochemical Data: Scott Halley July 2015Document40 pagesInterpreting Multielement Geochemical Data: Scott Halley July 2015boby dwi herguariyanto supomoNo ratings yet

- Arcosolv® DPM Acetate: Material Safety Data SheetDocument8 pagesArcosolv® DPM Acetate: Material Safety Data SheettiagojjNo ratings yet

- Financial CompensationDocument55 pagesFinancial CompensationJerome TimolaNo ratings yet

- Iom2 User ManualDocument13 pagesIom2 User ManualBogdan Florin SpranceanaNo ratings yet

- 1509846749lecture 11. 2k14eee Signal Flow GraphDocument62 pages1509846749lecture 11. 2k14eee Signal Flow GraphAmin KhanNo ratings yet

- Challenges Ppt-CorporateDocument21 pagesChallenges Ppt-CorporateBabust AwsNo ratings yet

- English G-11 Handout, 2012Document52 pagesEnglish G-11 Handout, 2012Ebrahim KhedirNo ratings yet

- Mopo SimopsDocument1 pageMopo SimopsKamal DeshapriyaNo ratings yet

- S3-4 Rotameter 010113Document21 pagesS3-4 Rotameter 010113Shaik HabeebullahNo ratings yet

- Arnett (2006)Document4 pagesArnett (2006)Wulil AlbabNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 New MediaDocument6 pagesAssignment 2 New MediaJishan ShaikhNo ratings yet