Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 viewsHorizonte Medio en El Norte Chico

Horizonte Medio en El Norte Chico

Uploaded by

Cesar Fernando Tocto SotoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Clasificacion de Monumentos Arqueologicos PrehispanicosDocument15 pagesClasificacion de Monumentos Arqueologicos PrehispanicosCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Juventud y Cultura Politica en El PeruDocument5 pagesJuventud y Cultura Politica en El PeruCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Las Claves de La Participacion Estudiantil (U)Document9 pagesLas Claves de La Participacion Estudiantil (U)Cesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Temas Recurrentes UnmsmDocument1 pageTemas Recurrentes UnmsmCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- San Isidro LabradorDocument140 pagesSan Isidro LabradorCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Historia de La Facultad de Educacion - UNJFSCDocument4 pagesHistoria de La Facultad de Educacion - UNJFSCCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Escudos Chancay (Museo UNTDocument6 pagesEscudos Chancay (Museo UNTCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Fijazas de La UnmsmDocument21 pagesFijazas de La UnmsmCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Apuntes para La Investigación y La Enseñanza de La Historia Local y RegionalDocument16 pagesApuntes para La Investigación y La Enseñanza de La Historia Local y RegionalCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Cardenas Sobre Antonio RaimondiDocument10 pagesCardenas Sobre Antonio RaimondiCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

- Investigaciones Arqueologicas en HualmayDocument17 pagesInvestigaciones Arqueologicas en HualmayCesar Fernando Tocto SotoNo ratings yet

Horizonte Medio en El Norte Chico

Horizonte Medio en El Norte Chico

Uploaded by

Cesar Fernando Tocto Soto0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views17 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views17 pagesHorizonte Medio en El Norte Chico

Horizonte Medio en El Norte Chico

Uploaded by

Cesar Fernando Tocto SotoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 17

Carrer 10

x

Piecing Together the Middle

‘The Middle Horizon in the Norte Chico

Kir Netson, NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL PERALES

HE DATA FOR THE Norte Cuico do not fit

Tose of social or political control by

the Wari during the Middle Horizon (MH).

Instead, they reveal participation of local polities in

at least two panregional iconographic phenomena as

wall as in theie own localized systems. These levels of

participation are visible in architecture and pottery sty-

liseicfeataces in both the Pativilea and Huaura valleys.

Stylisic similarities in architecture document local sol-

arity by the presence of repeated room forms, invoking

shared concepts of architecture and space. Pottery styles

represent a duality tha is indicated by the inclusion of

both Central Coase press-mold portery and more gen-

eral MH polychromes. Both architecture and pottery,

which each represent multilevel and multimedia sys-

‘ems of style, come together to form the complex MH

of the Norte Chico.

Previous notions of che incorporation of che Norte

Chico in the Wari Empire have been based on expan-

sionist models that include the north-central coast in

she broad area of control. These assumptions of Wari

dominance were based on characterizations of the Wari

as having broad concrol over vast regions (Isbell and

‘MeBiwan 1991; Schceiber 1992) and on isolaced finds of

Wasiclike architecture and pottery in the region, The

Norte Chico was included within che Wari Empire

because of is location close eo sites such as Pachacamac

(Roscoworski de Diez Canseco 1992; Shimada 1991;

Uhle 1903) and Socos (Isla and Guerrero 1987), which

were argued co have Wari components. The incerpre-

tation of the Norte Chico as one of the many areas

under Wari domination was sealed by afew tantalizing

descriptions of Wari-type artifuceual remains discov-

cred in the Supe Valley (Menzel 1977; Reiss and Scuebel

1880; Uble 1925) and at the coastal site of Véguerain che

Huaura Valley (Shady and Ruiz 1975). As eesule, che

Norte Chico is assumed to have been under Wari domni-

nation even though there was scant empirical evidence

of direct control.

Using broadscale patterning of eats, we explore

the stylistic elements that compose the MH complex

in the Norte Chico. We use these data co documene

different levels of stylistic spheres, including panre-

gional, regional, and local distribucions. These stylistic

modalities are displayed in a variety of medi

ing archicecrure and pottery, and detail che complex

stylistic systems of this frontier zone during the MEL

This reevaluation of the MH in the Norte Chico raises

larger questions of the role of the Wari in this and

other intermediary or frontier areas. These results sup-

pore a dynamic model of interaction that includes the

importance of ocal systems of power and authority chat

develop wichin the context of negotiating the incorpo-

ration of specific components of the political ideology

shat likely underlie the larger stylist systems.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

The Pativilea and Huaura valleys are located on the

Central Coast in an area referred to locally as the Norte

Chico (Figure 102). Alchough identified as a distinct

region, che various cultural connections among val

leys in the Norte Chico changes through time. During

some periods, these connections articulate beyond, and

172 NIT NELSON, NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL FERALES

Jn some cases are stronger outside of, the Norte Chico.

Archaeological research documents long human occu-

pation of the Norte Chico. Although focused on the

caliest and latest prehistoric periods, this work has

revealed a range of site types and occupational periods

inthis region.

Research in the Norte Chico began in the 19208

with the visits by Uhle (1935) to the Supe Valley and

included basic published descriptions of the archaeol-

‘gy: In 1943 preliminary excavations fhe ste of Puerto

4e Supe and other sites outside of the Norte Chico were

carried out by Secongand Willey (1943).Following these

Figure to. Map of the

Norte Chico marked

with sts discussed in

the text

carly studies, more detailed projects were conducted.

“These lacer investigations are dominated by a focus on

sites dating to the Preceramic (or Late Archaic) Period.

General discussions concerning the Preceramic in the

Norte Chico cover social organization, consumption,

conetol, and other diverse topics (Engel 1957a, 1957b;

Feldman 1985, 1985,1987; Haasand Creamer2001,2004:

Haas et al. 20042; Moseley 1975; Vega-Cenceno Sara-

Lafosse 2005a; Vega-Centeno Sara-Lafosse etal. 1998;

Zechenter 1988). Derailed investigations have occurred

a several Preceramic sites including Aspero (Feldman

1980; Moseley 197s) and Lampay (Vega-Centeno Sara

Lafosse 2003b, 2006, 2007: Vega-Centeno Sara-Lafosse

etal, 006), and projectsare ongoingat the sites of Caral

(Shady 1993, 1995, 1997, 19998, 1999, 1999, 19994,

2000a, 2000b, 2000¢; Shady et al. 2001), Caballete

(Haas etal. 2004b), Huaricanga (Haas tal. 2007), and

Banduria (Chu Barrera 2006; Fung 1974)

‘The later periods of the Norte Chico have received

less attention (Ruiz Estrada 1999). Surveys of the lower

and middle valleys have provided basic information such

as site location and general time period. These surveys

provide the basis for underseanding change through

time and period-specific settlement patterns. The first

survey of sites was carried out in the Huaura Valley

using air photos by Cardenas (1977, 1977-1978, 1988),

which resulted in a list and descriptions of sites based

‘on Cardenas’ study by Miasta Gutiérrez and Merino

Jiménez. (1986). Several more recent comprehensive sur-

veys of the Huaura (Nelson and Ruiz 2004), Pativiles

(Perales Mungufa 2006), and Fortaleza valleys (Perales

‘Munguia 2007) incorporate new data collection meth-

ods including Global Positioning System (GPS) and

geographic information system (GIS) technology and

provide improved coverage of the lower and middle val-

leys of the Norte Chico.

‘The majority of excavation projects at late period

sites in. the Norse Chico has been focused on Late

Incermediate Period (LIP) sites and their association

to the Chancay. These include descriptions of che sites

of Centinela and Vileahuaura by Kosok and Schaedel

(Kosok 1965) and small-scale excavations at Rontoy,

Quipico, Centinela and Chambara (Nelson and Ruiz

Estrada 2010; Ruiz Estrada and Nelson 2008), and Casa

Blanca and Quintay (Krzanowski 1991) in the Huaura

Valley. The fortress of Acaray has both an LIP and Early

Horizon occupation that has been studied in more detail

(Brown Enrile 2005, 2006; Brown Enrile and Rivas

Panduro 2004; Brown Vega 2008, 2009; Horkheimer

1962; Ruiz Estrada and Domingo Torero 1978), includ-

ing large open excavations and radiocarbon dating con-

firming the timing of use (Brown Vega 2008).

Of specific interest co this paper ae the studies of

MU sites, The MH in the Norte Chico islargely unstud-

ied; few published reports are available, and chese rep-

resent a small number of sites, ll of which are focused

‘on individual finds or descriptions of single sites. Shady

and Ruiz (1979) discuss the multiple design styles pres-

ent on pottery from MH-period burials From the site

of Véguera located in the coastal zone of the Huaura

Valley, sessing the importance of local polities in the

Norte Chico during the MHL. The site of Caldera was

examined by Seamer (1952), who provides a general site

map and discusses the types of portery found, inluding

both MH and LIP pottery styles. More recent work at

the MH sites of Caldera and El Carmen in the Huaura

Valley include targeted excavations within MH archi-

tecture (Heaton et al 2010; Pierce Terry etal. 2010). In

all, although the valleys ofthe Norte Chico are rich in

sites dating zo all periods, very ltl is known about the

archaeology of this area.

ASSESSING ARCHITECTURAL STYLE

‘This study isbased on a combination of valley survey and

stylistic analysis oftraits. These data are preliminary and

based on analysis of data collected duringan inital valley

survey and small amounts of additional site documenta-

tion. In che Pativilea Valley and Huaura Valley, initial

steps of systematic regional investigation were operation-

alized chcough siceess survey (Dunnell and Dancey 1985:

‘Thomas 1975) using Differential GPS (DGPS)-enabled

mobile GIS (Tripcevich 20042, 2004b, 2006) to system-

atically document artifact and architectural distcibu-

tions on the landscape (Craig eal. .007), Shuttle Radar

‘Topographic Mission (SRTM) (van Zyl 2001) 90 m digi-

«al elevation models (DEMS) and histori aerial photo-

graphs from the Servicio Acrofotogrifico Nacional

PIECING TOGETHER THEMIDOLE 173

(SAN) were added to the GIS database to create a more

detailed picture of the sites and their relationships co

the valley topography. These data provided the discribu-

sion of sites by general time period as well as very basic

maps of each site. Additional data were also collected,

including general potcery information based on surface

scatters and types of construction techniques utilized.

The second phase, sill in progress is designed to furcher

develop che valley chronology using radiocarbon dat

ing and ceramic analysis. This phase includes additional

‘mapping, small-scale excavation, and artifact analysis of

sites throughout che valleys.

‘MH sites were documented during the survey, and.

the site of Caldera was chosen for a small architectural

seudy due cits high level of preservation, Located in the

middle ofthe lower valley on the north side ofthe river,

Caldera rests in a small guebrada and is visibly promi-

nent from che valley lor. A map of selected architecture

at the site was created using che DGPS-enabled mobile

GIS, and datz on each room, including presence and

description of doorway embellishment, wall construc-

tion, plaster color, doorway wideh, wall height, number

of stories, and type of subdivisions, were recorded for

‘ach ofthe thirteen buildings studied. Although this is

by no means a complete record of the ste of Caldera, ie

isa sample chat represents some ofthe diversity in archi-

tecture ata well: preserved MH site that i typical ofthe

architecture ofthis period in che Huaura Valley, in con-

trast to the Pativilea Valley, where no such well-preserved

sites were identified during survey.

‘he detailed study of the site of Caldera was then

compared to observational data collected during survey

and used to mote broadly define the MH architeccural

traditions. Special focus was given to architectural styis-

sicelements that were present atallstes and features that

defined the MH and were not present at sites dating to

periods directly before and following the MH. Detailed

featutes at Caldera include embellished doorways, spe-

sialized wall form, and distinctive wall color. These fex-

‘tures were present at sites in the Huaura Valley and not

present in the Pativilea Valley. Sites in the Pativilea Valley

shared fewer and more general features. In both cases,

architecture represented localized expresions of ideas of.

space, function, ideology, and aesthetic (Moore 1996)

174 KIT NELSON. NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL PERALES

ARCHITECTURE AS STYLE AND

‘THE MH oF THE Norte Cuico

The patterning ofarchiteceuralrypes within che Patvilea

and Huaura valleys reveals the localized nacure of syle

and possibly the extent of local polities in the Noree

Chico during the MH. The regularity of architecture in

the Huaura Valley, and toa lesser extent in the Pativilea

Valley, presents and represents shared concepts of space

(Hillier and Hanson 19843 Lawrence and Low 990) as

documented in the repetition of layout and architectural

featuresat both the intersite and intrasit levels

In the Norte Chico, the MH settlement pattern

consists of small (<1o ha) dispersed sits. Stylistic dis-

twibution of architectural forms is valley specific. In the

Pativilea Valley, these similarities inchude three types of

archivecvure distributed throughout the valley. In the

Huaura Valley, che similarities among sites are much

greater, s0 that each ste is dominated by the same archi-

tectural style denoting a greater level of internal consis-

tency than the sitesin the Pativilea Valley show. In both

valleys, there is @ lack of typical Wari administrative

architecture; instead pacterning of architectural styles

by valley represents both local expressions of style and

local attempts at control

Architecture ofthe Pativilea Valley

Acoral of fifty MH habitation sites were identified in the

Pativilea lower and middle valley during a comprehen-

sive survey carried out between 2005 and 2006 (Perales

Munguia 2006). The sites, with single-component sur

face assemblages, are dispersed from the coast o 20 km

inland, where a concentration of sites is located juse

before the valley constrits at the hydrologic apex or

valley neck. Above this constriction, fewer sites are pres-

ent. The second cluster of sces is located near che mod-

xn village of Huaylillas, which is near the upper limi

of the survey area, The clustering of MH architecture

in the Pativilea Valley may be strategic for controlling

down-valley irrigation. Thisis especially imporrane given

the arguments for droughe conditions during the MH

(Shimada eal. 1991).

‘Much ofthe architeceure ofthe MH in che Patvilea

has been heavily eroded or completely destroyed by

modern agricultural expansion chrough the lower and

middle valle. The destruction of surface remains atsome

sitesis complete due to bulldozing to lateenateas for agr-

culture and che expansion ofitrigation canals chav enable

new areas tobe farmed, Other sites are disturbed by boch

smallerscale agriculture, modern habitation, and loot

ing, Due to these factors, the daca for the MH horizon

‘occupation in the Pativilca are based on acombination of

both survey and close examination of air photos to docu-

ment sites. From these sources, chree types ofhabieation

sites have been identified in the Patvilea Valley: adobe

compounds (ten sites), room aggregates (six site), and

terraced complexes (thirty-four sites), These sites were

classified as belonging to the MH based on the sucface

scatters oflocal polychrome pottery.

Adobe compounds are groups of buildings oxga-

nized in a square or reesangular plan that is intcznally

subdivided and enclosed by a surrounding wall. Some

compounds re oriented norch~south (Figure 10), oth-

ers have a more random organization (Figure 10), and

there is no regular plan co the internal layout for either

north-south or randomly oriented compounds. These

compounds are large, spacious, and organized. The

internal rooms range in size to 8-10 x 1215 m. Internal

construction is usually composed of adobe brick walls

(Chickness= 5m), while che outer wal is made of adobe

tapia,or poured adobe (thickness =0.8-1 m),andistypi-

cally thicker than che inner walls. Medium-sized blocks

of fieldstones are sometimes used as the foundation

of the oucer walls. Although doorways ae pooely pre-

served, their preservation is sufficient to determine that

they lack che typical entryway embellishments observed

at Huaura Valley MH sites (to be described fureher). In

the Pativilea Valley, these compounds seem co be part of

larger architectural complexes chat would have excended

toward the valley loor but that have been destcoyed by

modern agriculture and looting. Site size canges from

approximately 2 to 10 ha,

Evidence of use of compounds is based on examina

tion of stratigcaphy exposed in looters’ pits. These sites

ate more commonly targeted by looters due to location

and the common presence of intrusive burials, and so

some evidence of use can be determined. While surface

refuse is scarce in these buildings, deeper deposits reveal

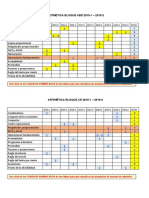

Figure 10.2 Plan map of the ste of PVsg-am located in the

Pativilea Valley.

30-212 General Plan

rae UT Zon 108

Sonn wee

| erosanges Laer: ieeaty

CoreandScbnte G

‘Sot reona 05m

Soeettio

0125 255075 a0

———

Melon

Figure 105 Plan map ofthe site of PV39-212 located in the

Pativilca Valley.

MIEGING TOGETHER THE MIDDLE 175

poorly preserved rextiles, human remains, and pottery.

‘Also present are ash lenses and other features that sug-

gest some residential activities in these spaces. In some

cases, the pottery present includes Late Intermediate

Period sherds, which may denote intcusive burials in

this MH architecture, « common phenomenon in the

Norte Chico.

In summary, compounds are an important feature

of the MH architecture in the Patvilea Valley. They are

the most formal architectural evidence in the Pativilea,

and, even when they show some degree of variability,

their size, organization, and structure are important

markers of the MH in both the Pativilea Valley and the

Norte Chico.

Room aggregates, or clusters of rooms, ate present

in all sections of the valley. These, t00, ae heavily dis-

turbed by modern agriculture and Jooting. The rooms

are square to rectangular in plan and small, measuring

approximately 2-3 m per side. Walls, measuring approx-

imately 0.4 m in thickness, are made of worked stone

and mortar. They differ from compounds in that they

do not create a rectangular or square plan, they are not

organized within a single surrounding wall, and they are

random in orientation and layout.

‘Terraced complexes are sites that were cut into the

lower slopes of the valley edge, usually following the

natural topography of che hillside, These sites are most

abundant in the area where the valle begins o constrict

at the hydrologic apex. The reduction in available land

‘on the valley floor and the absence ofa large frst verrace

above the valley foor may be the reason that this type of

site is Found cut into the slopes at the valley edge. They

may also have been partoflargersites chat were destroyed

and are not visible on the 190s air photos.

Architecture ofthe Huausa Valley

Similar architectural features are shared among the

‘majority of MH sites within the Huaura Valley (n= 54).

‘The MH architecture shows a complete stylistic

connect with earlier Early Intermediate Period (EIP)

architecture, with MH architeccure typically located

adjacent to or in differen places from earlier architec-

ture. Moreover, ic differs in construction techniques,

176 KIT NELSON. NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL PERALES

structure layout, and site organization, Architecture of

‘the EIP is made from unworked stone masonry, not the

adobe brick or tapia chat has been noted for EIP sites,

Sice layout includes clustered two-roomed structures

focused around a hilleop foreress with litle internal

organization. MH sites are typically more organized and

are not defensive in nacure,

MH sites are composed of clusters of individual

rooms, of which few are subdivided. The majority of

structures that make up these MH sites share architec-

tural features chat include embellished doorways, exter

nal decorative elements, and brightly painted exteriors.

‘hisarchitectural style is repeated chroughout the alley

at every MH site recorded in the survey.

‘The embellished doorways are present not only

in one or two examples at each site, but are a canonical

element of the majoriey of structures (Figure 10.4). This

architectural feature is easy to identify, even when embed-

ded in later architecture or within sites that were heavily

Tooted due to the presence of later cemeteries within the

abandoned MH architecture. The embellished doorways

are an extension of the exterior wall into the bounded

space of the room, forming a 90-degree angle or L shape.

This feature i present on both sides ofthe door and cre-

ates a restrictive passageway into the room. There is minor

‘aabiliy in this feacue; for example, some appear only

a a thickening ofthe doorway and not wall extensions,

others ate more rectangular or columnlike in shape, and

a few structures, those with internal subdivisions, are

missing this feature entirely. At che ste of Caldera (PV

671) Figure 105), embellished doorway width (x= 83 cm,

sd.= 1 em,n = 9, range = 47-120 em) and embellish

ment width (i= 6o cm, s.d.= 1 m,n =12,range= 34-82

cm) vary in size, while wall width (= 38 em, sid. = 5 cm,

n=12,range = 30-46 cm) isless varied, These embellished

doorways are an idencifying feature ofthe MH in this va:

leyin that they are not present at sites that pre-or posdate

the MH in the Huaura Valley. These kinds of doorways

have not been widely reported at sites beyond Huaura (see.

Benavides 1991:60; Williams 2001;Figure 10, Structure B,

as possible examples at Wari sts) and are not typical fea-

tures of Wari architecture,

Tivo other feavures of MH architecture in the

Hiuaura Valley are the use of shaped exterior walls and

Figure 10.4 Cluster of architecture a the upper end ofthe qubrada at Caldera, Hau Valley. Each

's coated in brightly colored plaster and inches the achiteccralfeatute ofan embellished doorway.

Pryor: Zoe 18,

one wees

‘enadoges Locate Ottery

maa Serr G28

Sestnanat con

Seuss

os

Nes

Figure 105 The archaeological sce

‘of Caldera. Lines represent walls

‘mapped in che field using submecer

dlifferencally corrected GPS. The

gray area represent che limits of the

Instturo Nacional de Culkura site

boundary polygon.

tinted plaster. External wall decoration is sometimes

present on MH architecture, The wall decoration

includesa shoulder present on the exterior that does not

appear to be structural buestessing. At Caldera (PVgx

671), ewelve cases had external wall decorations present

‘on buildings. The presence of this exterior decoration

does not seem to be correlated with internal subdivisions

of che building (internal building complexity). In seven

of the rwelve cases, rooms with exterior decoration are

not subdivided. In four cases externally decorated rooms

are subdivided, and one room is not subdivided and does

not have external decoration.

External walls are often plastered to form a smooth

exterior, with some rooms decorated in plaster tinted

in either yellow or red (See Figure 10.4). This feature

enhances both intersie visibility of these structures and

their visibility from the valley. The majority of the build

ingsat MH sitesin the Huaura Valleyhave taupe-colored

exteriors. Taupe is the natural color of the sediment of

the area and represents untinted plaster, and the most

cost-efficient plaster co uilize, while afew buildings are

plastered in bright yellow or red.

‘The wall color was recorded for a sample of build-

ings at the site of Caldera. The colored plastered walls

ate clustered at the site ina single sector located in an

area chat i farchest from the floodplain, where they are

the most isolated from other architecture and where the

natural ground is the highest. Of the small sample of

thirteen buildings, seven had caupe-colored exteriors,

four were yellow, and two red. It should be noted that,

this small sample does not represent the normal color

distribution of the site, as the area sampled was where

the majority of colored plastered buildings were located.

‘The notmal representation of taupe-colored buildings at

‘MH sites in the Huaura Valley is closer to 75 percent or

more of the architecture at each site.

Inthe thirteen buildings at Caldera, the dominance

of taupe-colored exteriors is interesting when viewed in

light of the distcibution of subdivided verses unsubdi-

vided rooms. Six ofthe seven buildings with taupe exte-

riorshave no internal subdivisions, while halfofboth the

yellowand red buildings have subdivisions. This suggests

‘a mote complex internal structure of the buildings wich

brightly colored facades. This, in combination with the

178 KITNELSON, NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL PERALES

presence of brightly colored architecture in a cluster at

the site, and the inereased labor and access to materials

needed to create the yellow and red plaster, may suggest

hae these buildings represented administration build-

ings, elite residences, or, as Isbell and Vranich (2004)

suggest, ceremonial architecture. The importance of

brightly colored structures, stylistic feature of MH sites

within the Huaura Valley, demonstrates that although

these structures have restricted accessibility, they were

shared by the MH population due to their wide visibil

Sines such as Caldera are composed of architecture

that is ubiquitous at MH sites throughout the Huaura

Valley. The characteristics ofthe sample of architecture

reveal alittle about the function of the structures them-

selves or each site as a whole, Ths is not cypical habita-

sion architecture, First chereisalack ofdomesticrefuse or

cooking areas that are typical of habitation architecture.

These rooms are open on the interior, and access to these

scructures is limiced by their arrangement on the land-

scape and by the location of the eneryways, In addition,

the entryways are formed so that acess is restricted, vis-

ibility ofthe interior reduced, and only one person could

enter ata time. These sites are not defensive and, in the

case of Caldera and other MH ste in the Huaura Valley,

are easly seen from the center ofthe valley. The brightly

colored rooms draw additional axtention to these sites,

Since the architecture is not residential, the other

possible functions are administrative at some level or

another. This architecture could represent civic space

used for decision-making activities of small groups ot

councils. It may also represent storage that would have

been controlled. It could also be a combination of both

of these functions, In either case, it was meant to be seen,

and yec knowledge of what was cartied out or stored

inside the space was restricted and access to itwaslimited.

MH Architectural Features in the Norte Chico

‘Two features are shared among MH sites in the Pativilea

and Huaura valleys, The first is che presence of sites in

easily accessible locations, suggesting thae the Wari did

not have an aggressive military presence in the region.

‘The second commonality is the presence of repeated,

locally distinct themes of architectural embellishment.

None of the MH sites in the Patvilea and Huaura

valleys are located in typically defensive posiions, nor

do they contain che classic hallmarks of defensive archi-

tecture. The majority of MH sites are located on the first

terrace above the floodplain, usually in small quebradas

thac open tothe valley. Though not systematically ested

aguinscan expected pattern, sites are often highly visible

within the valley, Several of the buildings are brightly

coloced, making them even more visible from the valley

floor and suggesting that visual prominence may have

been an important criterion in their construction,

Though some sites, including Caldera and two sices

near the fortress of Acaray (PV41-69, PV41-76) ate sieu-

ated in small quebradas that have high ridges, the ridges

ate easily maneuvered, and no evidence of additional for-

tification along these ridges was encountered, No perim-

‘cer walls are present, and the eases ines of ener into

the sites fcom either the ridge othe valle are noe asi

cially fortified. Within che area of compact architecture,

small alleyways are present, and although maneuvering

through the tightly packed archicecture would have been

difficule, there ace multiple locations of entcy alongevery

side, which means it would not have been difficule co

overtake these small communities

The second notable architecoural feature in che

Norte Chico s the presence of locally distinct repetition

of architeceural elements. The tree forms ofarchitecture

ppresentin the Pativilea seem distince, bur due to the wide-

spread destruction of sites in this valley, we do not know

whether all chree forms are included within each of the

MH habitation sites in the Pativlea. This composite of

architectural features may reflect diferent functional

characteristics and not intersite differences. The MH

architecture of the Huaura Valley displays a greater sense

‘of cohesion, wich litele intersite variability. The repeti-

tion of cis architecture throughout the valley implies a

greater level of incernal consistency than is evidenced by

architectural distributions in the Pativilca Valley.

MISSING ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES—

Way Nor Warr?

Several features thar have been identified as typical in

the Wari architectural canon are absent in the Huaura

Valley. These elements include masonry or rubble walls,

Deshaped structures, patio groups, orthogonal architec-

cure, and great walled enclosutes. As Isbell (1991) notes,

Wari sites do not necessarily exhibit all of these archi-

cectural fearues. Yee in the valley we find none of these

imporcane features that have come to define both the

Wari core and che distribution of Wari influence. The

absence of these architeccual elements is importane in

assessing the role of the Wari in the Norte Chico.

Masonry or Rubble Walls

The majority of MH architecture identified in the

Pativilea and Huaura valleys is composed of adobe

brick or tapia walls. Neither finished stone nor unfin-

ished masonry architeceuce is present at MH sices in

the Huaura Valley, and few examples exist from ME

architecture in the Pativica Valley. Alchough unfin-

ished stone is sometimes present as foundation supports,

itis not used for che visible wall segments. Ie may not

have been possible ro make the finished stone masonry

archiveceure seen at Huari (Benavides 991: Jennings and

Yépez Alvarez 2001) because che Norte Chico lacks fine-

{rain stone as well asthe local masoncy experts needed

co create this architecture. Bur rubble-stone masonry

was possible—ic is present throughout the valley in

architectural examples that have been assigned to the

Late Preceramic, Initial Period, and Early Incermediate

Period. The masoney has been dated through analysis of

associated ceramic styles (Nelson and Ruiz 2004), while

mortar from masonry walls at Acaray was radiocarbon

dated to the Early Horizon (Brown Vega 2008, 1009).

D-Shaped Structures, Patio Groups, Orthogonal

Architecture, and Great Walled Enclosures

Absent from the MH architccture in the Pativilea

and Huaura valleys are several feacures that have come

to define the MH in the Wati cote: D-shaped seruc-

‘tures, patio groups, orthogonal architecture, and great

walled enclosures (for examples and descriptions of

these architectural types see Cook 2001; Isbell t991,

2006; bell and Vianich 2004:176;Jenningsand Yépez

Alvarez 2001; McEwan 1996; Moseley etal. 199). This

PIECING TOGETHER THE MIDDLE 179

suite of architectural features is in part time sensitive

(Isbell 2001), and so the timing of Wari expansion

into the Central Coast may be one of the reasons for

the absence of one or more of these architectural fea.

tures, The absence of them all suggests that there was

‘no major Wari administrative /religious cencer in these

valleys, These specialized facilities should exist for

administration with a state-level organization (Wright

and Johnson 1973). What is significant is not only that

these feacures are absent, or that planned settlements

and large urban centers are not present (see Anders

19895 Isbell 1991, .006; Schreiber 1992), rather itis this

toral ack of Wari-indicative architectural features, in

addition to the absence of planned sectlements and

large urban areas, amid a orescence of local MH archi-

tectural craditions thar do not embody the grandeur of

the Wari core.

Porrery AND ICONOGRAPHY

No derailed stylistic or sourcing studies have been car

ticd out on the MH pottery from either the Pativilea

cor Huaura valleys Sil, visible a each of the sites isthe

presence of both Central Coast press-mold and utili

tarian wares (Figure 10.6) and polychromes with MHI

features (Figures 10,7). Central coast press-mold pot-

tery is present from the Pativilica and Huaura valleys,

possibly from farther south, and from farther north as

found in the Casma Valley (Mackey and Klymyshyn

1990). These press-mold wares have a variety of names,

usually based on where they are found, a result of the

lack of detailed studies on similarities and differences

among valleys. Some local names include both Pativilea

and Huaura Impressed. These styles are created not by

impressions, but by the use of molds, several of which

were found in the Patvilea Valley during survey (Perales

Munguia 2006). The imagery usually includes the use of

framing lines to delineate areas of decoration, Within

these zones of decoration are typically patterns of raised

lines and bean shapes (see, for example, Shady and Ruiz

1979:Figure 6). Someexamples also include stylized birds

and sea animals, with greater variation in figures presenc

in the Pacivlea chan in the Huaura Valley. The broad dis-

tribution of this press-mold pottery is also documented

180 KIT NELSON. NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL FERALES

as a north-central coast phenomenon during the Late

Intermediate Period (Bria 2006). This distribution sty-

listically isthe valleys of the Norte Chico intoa norch-

central coast iconographic system, one that continues

into the following period.

Also present are polychromes that have been

defined as similar to polychrome pottery from Nasca

and Wari, with a specific example having shared char-

acteristics with the Epoch 2A style of the Wari chronol-

‘ogy (Shady and Ruiz 1979) and Epoch 3 and 4 (Menzel

1977). Beyond the small studies conducted by Shady

and Ruiz (1979) and Menzel (1977), no additional

detailed data have been collected, and so no data con-

cerning the similarities or differences to Wari style are

available, nor have the observations listed been quanti-

fied. Lacking these studies, there are some general fea-

tures that document traits that could be more broadly

defined as generalized MH traits and not the result of

Wari control.

A. great variability exists in the imagery present

and the location of decoration. Polychrome pottery of

the MH in general shares a similar color palette, includ-

ing yellow, ted, cream, and black decoration on a red

LT

Figure 10.6 Impressed Middle Horizon pottery fom

Lutiama, Huaura Valley

background. Utilizing this color scheme, the majority

of polychrome vessels from the Norte Chico have sparse

decoration that includes bands parallel ro and near the

rim ora band, sometimes with dots, perpendicular to the

rim. The characteristic MH features, uch asthe presence

cof mythical figures (Menzel 1977; Figure 1.72) are pres-

enc but rare and are not integrated into detailed design

motif like those found on Wari vessels. The blocky fig-

ures and design elements within larger motifs are also

rare in the Norce Chico. Overall che pure quantities of

clements and motifs are few, and motif are simple, typi-

cally composed of only few geomecric elements. These

motifs are then replicated across the zone of decoration.

This design layout mimics thae found on the local press-

‘mold ware that is the dominate poteery style during the

MH in the Norte Chico.

SrvListic SPHERES AND WARI FRONTIERS

Style is based on many factors (Hill 1985; Hodder

1982; Plog 198, 19915 Roe 1995) chat take on multivo-

cal and multivalent meanings and may be employed

to enforce boundaries or appeal to hybridity. The MH

of the Norte Chico shows culeural plurality, as repre-

sented in stylistic characteristics where “cultures exist

with different natures of contents and boundaries”

(Gullestrup 2006:167). This plurality is visible in che

local MH architectural canons as internally cohesive

and diseiner from che Wari core. Likewise, pluraliy is

Figure 197 Middle

Horizon polychrome

poccry fom the Huaura

Valley: devo wich mia

figure from Lariam (a),

lero fom Pampa de las

Animas (b), impressed

polychrome from Pampa

delas Animas (.

also exhibited by poctery style. In the Norte Chico dur-

ing the MH, there isa co-oceusrence of local Central

Coast press-mold wares with pottery bearing panre-

gional polychrome decorations that arc reminiscent and

yet atypical examples of classic Wari design elements

Using the broadscale patcerning of syle in both archi

tecture and pottery, we have addressed che interplay of

local and nonlocal symbol systems inthe Norte Chico

by examining the layering of architectural and pottery

attributes and the cole of outside forces in che frontier

policies of the Central Coast.

Panregional MH Style

At the broadest scale, style in the Norte Chico is part of

the pancegional MH symbol system. These styles, includ

ing the wide distribution of polychcome pozeery,crosscut

cultural boundaries and are integrated into local poli

ties. In the Norte Chico, these widely distributed traits

appear together with the advent of nev, locally distinct

architectural styles. The combination of cosmopolitan

seyles and the emergence of local ones marks the bitch

of the MH and is one of the mukiple symbol sets used

within the regio,

‘he shift co wha is defined asthe MH includes the

introduction and incorporation of a myriad of traits,

‘one of which is the advent of the MH.-seyle polychrome

pottery (also see Marcone, this volume). These traits are

prevalent and not randomly distributed. In fact, they

PIECING TOGETHER THE MIDDLE 181

cover large areas and occur in conjunction with broad-

scale changes in socioeconomic systems that inchide

the formation and expansion of state-level societies

such as the Wari In some cases, the spread and accep-

tance of the MH polychrome-style pottery represents

the expanding states through the formation of border-

lands (Parker 2006) and the usurping of local power

as part of locals’ incoxporation—whether militaristic,

economic, or religious—into the growing states. In

‘other cases, asin the Norte Chico example, the spread

of these stylistic features does not seem to be due to

domination of local powers by expanding states, The

absence of evidence for either military takeover, seen in

the lack of defensive localities, or state-sponsored con-

trol, seen in the dearth of typical Wari administrative

facilities, implies that in the Norte Chico the influence

of Wari did not entail direct control. Yet the MH style

is incorporated inco the local symbol system, including

use of mixed stylistic traits such as polychrome-zoned

decoration following local traditions and polychrome

designs on press-mold ware.

Although not directly controlled, the spread of this

styleisnotrandom when viewed in ight ofthe Tivwanakus

‘and Wari expansion. This period of organized state esca-

lation and advance of both the Wari and Tiwanaku may

have facilitated che distribution of the MH style, includ

ing the use of polychrome porcery and mychical figures,

through the north-central and North Coast of Peru. As

noted by Isbell and Schreiber (197), state-level systems

are one way in which information, and thus style, can be

distributed and enforced.

‘Multiregional Systems

In addition to the incorporation of regional MH styles,

the Norte Chico also participated in both mulkivalley

and valley-specific stylistic systems. Although differing

in the media in which they are portrayed, these reflect

the shared concepts of style at mulkple levels

Potcery styles reflect mulkivalley connections. The

presence of press-mold pottery vessels with similar

designs and use of decorated space is more restricted in

its distribution. The Pativilea and Huauta valleysare ust

‘wo of the north-central coastal valleys in which this

182 KIPNELSON.NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL YERALES

ware type is distributed. This distribution ties the Norte

Chico co valleys as far north as Casma and possibility

farther and may indicate a system of exchange of more

constant interaction in this region. Unforvunately, the

MBH of this area isnot yet well defined.

‘Ara smaller scale, both the Pativilea and Huaura

valleys show local stylistic traits in the form of archi-

tecture and pottery. These architectural features first

appear during the MH and show the reformation of

local cultures at che onset of the MH. Valley-specific

pottery styles are more difficult to tease out duc to the

lack of detailed studies, but i is possible, ifnot probable,

that thete will be localized expressions of style in this

media as well. The development and reproduction of

these styles are nor the result of emulation of the langer

sate systems—instead they represent specifi, localized

stylistic trajectories

Style in architecture, especially in reproduced

architecture, represents an important cultural maker.

‘The large and visible representations of local power in

architeccure are an important emblem of local control

visible not only a che personal, family, or community

level. Instead, architecture is displayed beyond local

“consumption.” ‘The presence of architectural styles

thar are valley wide demonstrates internal cohesion

and shared concepts of space and style throughout the

valley. These architectural features do not show emula-

tion of the architecture ofthe state-level systems of the

‘Wari, but instead embody local distinctness in their

structure and form. Local polities are then influenc-

ing or even controlling the patterning of architecture,

including the rules of construction, layout, and access.

The restricted distribution of these architectural forms

is in striking contrast to the broadly distributed stylis-

tic systems present in portery.

‘The Norte Chico Frontier Zone

“These multiple styles exist because the Norte Chico was

4 frontier a place “acthe edge fandin che mide] of eul-

tural spheres” (Patker2006:77). Combinations of slis-

tic traits ae expected in an area that serves asa frontier

zone where politcal, economic, and cultural boundaries

overlap (Elton 1996; Parker 2002, 2006). What results

is a complex mateix of stylistic expression—culearal

hybridity. Although the terms frontier and boundary

are usually used in the disciplines of history and his-

torical archaeology to define colonial expansion (i.e,

the Spanish frontier), these concepes ate applicable to

the study of any state expansion and influence—pre-

Columbian or otherwise. The complicated nature of

stylistic spheres in the Norte Chico sogether with the

presence of competing states tothe south, inchiding but

not limiced co Lima, Wari, and Tiwanaku, fits the defi-

nition ofa frontier zone and helps explain the plurality

of cultural expression present. Because frontier zones are

porous (Parker 2006), chese areas can maintain local tra

ditions while incorporating aspects of the systems that

surround them, These local expressions are preseneatdif-

ferent layers of these complicated matrices and so are not

necessarily regulated by others (ee, fr example, Morris

and Taompson 1970; Zimansky 1995)

‘The Norte Chico differs from other borderland

or frontier areas during the MH in thae i lacks both

administrative and miliary struccures that are present

in many other areas (Chapdelaine; Marcone; and Segura

and Shimada, this volume). lnseead of being directly sub-

sumed into the Wari system, the Norte Chico negotiated

4 relationship at one edge. Its role as a frontier zone is

visible in the multiple stylistic spheres that define this

region duringthe MH. Acknowledging areas adjacent to

the expanding states as frontier zones better defines their

relationship within the dynamic period of the MH and

helps co explain che multimedia and multilevel expres-

sions of syle present during this petiod.

ConcLusions

Broadscale patterning fseylstic elements in pottery and

archiecture from the Huaura and Patvileavalleysin the

Norte Chico indicates that this area was a frontier zone

that participaced ina range ofseylstic spheres duringthe

MH. The mukilayered, hybrid matrix of multimedia dis-

plays of style represents panregional, multiregional, and

local stylistic spheres.

At che broadest scale, panregional seyle is present

in the form of MH-style polychrome pottery Its pres-

«nce has been used to infer Wari control of the region,

but this discribution, although possibly aided by state

expansion, is spread beyond what can be argued as the

‘Wari state, Instead, when viewed feom the perspective

of che Norte Chico it is an iconographic constellation

that interfaced ina frontier zone. Ar the multiegional

and local scales, he Norte Chico both ted roche sur

rounding region whilealso locally defined. The stylistic

sphere of press-mold pottery stretches from the Huaura

Valley noreh as fr as Casma, eying the Norte Chico to

‘many north-central coast polities. Local styles exhibit

cohesion in the formality of valley-specific architec

tural styles thar show continuity in specific architec-

tural elements, suchas the embellished doorways in the

Huaura Valley.

‘The incorporation of multiple seylistic spheres in the

Frontier zone of the Norte Chico represents che compli-

‘cated emblematic systems at play during che MH. These

seylistic features represene mulkple levels of patticips-

tion in “overlapping politcal, economic, and culeural

boundaries” that define frontier zones (Parker 2006:80,

2002; Elton 1996) and reveal the pluralistic and hybrid

nature of culture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for the surveys used as che basis of this

research comes from several sources. The survey of the

Hluaura Valley was funded by grants from the Nacional

Geographic Society (Grant No. 7677-04), the Stone

‘Center for Latin American Seudies, and the H. Sophie

Newcomb Memorial College Insitute, and the survey

of che Pativilea Valley was completely supported by the

Field Museum, Nelson and Perales especially wish to

thank the Proyecto Arqueolégico Noree Chico, directed

by Jonathan Haas, Winifeed Creamer, and Alvaro

Ruiz and its many members for their grantsmanship

and logistical support. Many PANC members also pat-

ticipated in these surveys, including Miguel Aguilar,

Mateo Lopez, Gerbert Ascencios, Kasia Szzemski, Stacy

Dunn, Felipe Livora, Lucho Verastigui,and Don Galvez

and the Tulane 2004 field school

‘This paper resulted from an invitation by Justin

Jennings so participate ina session atthe seventh-fourth

meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, which

MiECING TOGETHER THEMUDDLE 185

was entitled “Beyond Wari Walls: Exploring the Nature

of Middle Horizon Peru Away from Wari Cencers” We

thank him for his tireless work to direct and organize

these papers. This paper also greatly beneficed from the

comments provided by Bill Isbell. The authors extend

their thanks to Margaret Brown Vega who assisted with

fieldwork and offered useful critiques ofthe paper in its

early forms

REFERENCES CITED

Andes Marcha

spa Evidence for the Dual Soco-Polscs! Orgentation and

Administrative Stare of che Wa Sete In The Nature

of Wart: A Resp ofthe Mae Horizon Period ef Per

diced by R. Michael Cowsrno, Frank M. Meddens, and

‘Alexandra Morgan, p. 35-2. BAR Ineratonl Seis 5

Bh Archaclogiel Repos, Oxford

Benavides C. Maco

1991 Chego Was, Hoar In Hard Adminlraive Stare:

Prebiderc Monumental Architecture and State Goverment,

edited by Willem H, bell and Gordon F. Mein, pp

46. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Calleson,

Wrshingion, DC

Bra Rebecca

2006 Linking the Cena and North Cent Pervian Coat

Pass inthe Lave Inermedite Period. Paper presented

the 7st Annual Meeting ofthe Society for Amerian

“Achaeclogy Sn Jun, Puro Rio

Brown Envi, Margaret,

2005, Pediminary Daa from he Archaeal Compler t Acary

2 Feed Sit inthe Hoaa Ville, Pern, Pper presented

a: the roth Annoal Mecing ofthe Soiey for American

-Archaology, ale Lake Cay

2006 Lae lmermedae Period Developmentsin the Huaur Vale,

Peru: Stating Miro-Seale Eres within Macro-Regional

Hino, Paper presented athe rsx Annual Meeting of he

‘Socey for Ameren Archaclogy, San Jan, Pert Rico

‘Brown Ene, Marae and Santiago Riss andro

2004, Proyecto arquolgiol Fortaleza de cae: Villede Haars,

el Final report submined wo the Iino de Naconl de

Calera, Per

Brown Vega Margaret

cot War and Social Life in Pehspanie Pers Ries, Defense,

aod Commis a the Forres of Acaray, Hoatra Vale

Unpublished PAD diseraon, University lino, Urbans

Champaign.

2609 Conf inthe Ex Horizon ad Lae Intermediate Period:

New Dats fom the Fores of Aca, Huaura Valley, ed

Gaent dthraplegy sol)s5-266

Cedenas Mercedes

1977 Informe prin del bj de campo cn lel de Haare

(Depaements de Lina), aq 197. Ponsa Universidad

384. KIT NELSON. NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL PERALES

Cassa de Pers, Ineo Ris Alero, Semiasio de

‘Aredia Lime.

syr7 Siiocanuclégcosen Mya Chis-Huacho (Valede

"O78 Hamar) In Belt del Seminar de dquo -20301-

16 Poni Unheried Catia del Pr, Lima.

ayH8 Artec pein delle de Hume in Simpson

“Apu Argue, Pasade yar dela contrin

nl Pe ead by Vicor Rancel Chiclayo, pp. 11-1

CONCYTEC, Universidad de Chiao, Chiclayo, Pera.

(Chu Bares, Akjando

zooé. La mided doméia dora el Prado recsimico en le

coma del ert Unenfoqu evlicinisa Ub Pat 95-15.

Cok. Ani

soo! Haat D-shaped Storrs, Saif Ofesings and Divine

Rlerhip. In Ral Serf in Ancient America, eid

by BlimbethP. Benson and Ania G. Cok, pp. 13-163

Univer of Texas Pres, Astin

Cig, Nathan, Mana! Pere, Nichols Tipcevich,Kic Nekon,

[Alto Rul, Jonathan Hass, Wied Creamer, Miguel

“Aula and Maco Liper

107 Sinema de informacion geogifica méviks come in

fret de informactn pra a clin y adi de

excenaas bates de dato reglonalescomparatas de sos

anqpolgins. Paper peed at the Conporave Pepecs

cn the Archeslogy of Cour Soth Amaia Lima

D?aloy, Terence N, nd Katharina Schreiber

2004 Andean Empire, In Andean Ares, eied by Heine

Siverman pp. 25-279 Blackwell New lok

Dannl Retr C, and William S. Dancy

1985 The Sele Survey: A Regonl Scale Dae Colon Sree.

Adsense Meth and Tey 6267-28

Elon Hogh

1996 Frome of te Roman Enpire. Indian University Pres.

Bloomington,

Engel rede

ros, Sits ec eablscmens sn craig de coe Pevienne

Journal del Soci de Americans Nucor a4

sorb Bay Ses om the Peaian Conte, Scena of

Autre 36-84

Feldman RobercA

i980 Apr, Peri: Architecture, Sobisence Economy and Ocher

“Arc ofa Precermc Markie Chiefdom, Unpublished

PhD. disernion, Harvard. Univers, Cambridge,

Masochmers

1985 From Mattime Chicdom to Agar Suen Formative

Coal erin Preston Setdoment Pater: Eun oor

of Gordon Wile, eed by Exon 2, Voge and Richard M.

Leventhal pp ts-sio. Presiden and Felows of Harvard

College, Cambridge, Masachosers

vols Precramie Corporate Archie: Evidence for the

Deelopment of Nom Egalitarian Social Sysems in Peru.

In Ear CoroenielAritacare in the dnd, eid by

CCrinopher Donn, pp. 7-93. Dmbastn Osis, Wash

ingron, D.C.

votr Architect idence forth Developent of Nonlin

Soc Syemsin Coal Pet In The Onis nd Devdopment

(the Andee Se, eed by Jonathan Hans Shela Pozo,

and Thomas Pozors p. 9-14. Cambridge Universi Pres,

NewYork

FrangPineda, Rosa

1974 Elst precerimico de Bandueia (Hsu) Paper presened

athe Il Congreso Peruano del Hombre y la Calara Andina,

“iyo, Pera.

Galleserup, Hans

2006 Cultnl Anais: Towards Cro-Ciltral Undontending

Aalborg Univesity Pes, Alborg, Denmatk,

Haas, Jonatha, and Winiied Creamer

00r Amplifyingimporcance of New Research in Peru, Response.

Scene 9421652165.

2004 Coleurl Transformations inthe Late Archaic, Note Chico

Region, ln Andean Archaeology, cited by HelineSverman,

ps5. Blckuell New Yor.

‘Haas, Jonathan, Winiied Creamer and Alvaro Ruiz

20044 Dating the Late Archaie Occupation of che Norte Chico

Region in Peru. Nene g3:to20~i085

2004b Proyecto de imvestigacién argueoldgia en et Norte Chico:

Excaaciones en Caballee, Valle de Foreless, Prd, Fina

seporsbmitted the lnsiuo de Nacional de Clear, Pc.

2007 Proyeco de invetigcinarqueolégia en el Norte Chico

Excavaciones en Huarcang, Valle de Foreaezs, Pei. Final

‘spore submitted to che Inscto de Nacional de Cla, Pe

Heaton, Ashley Kemachan, and Sacy Dunn

o1o New Research on Loe Bite Conccol inthe Husa Valley

North-Central Coast of Peru, Paper presented a the 73th

Amaal Meeting of the Socery for American Archacology

Se Louis

HHL LN,

1985 Sole: A Coneepal Evolutionary Framework In Devding

Prehitorks Crames edited by Ben A. Nelion, pp. 362-385,

Southern ins University Press, Carbondale.

ili, il and Jlenne Hanson

1984 The Socal Logic of Spce. Cambridge Univesity Press New

York.

Hodder. tan

198 Symbols in Action: Etbnoarchacological Studies of Material

alte. Cambidge niversiy Press, New York

Hotkheimes, Hans

i962 Laforalerade Huaura, Cae 2830, 58.

‘ibell William H.

‘gat Conclusion: Huai Adminieration and che Orchogonal

Cellular Architecture Horizon, In Aluari Administ

Structure: Prebistaric Monumental Architecture and State

Groemment, edited by Wiliam H. libell and Gordon &

‘MeEwan,pp.295~15.Dambaron Oaks Research Libary and

Collection, Washington, D.C.

2001 Repensando el Horizonte Medio: El cazo de Conchopata

Ayacucho, Peni. [a Hluari y Tiwenahe: Modelos os

svidencias, Primera parte, ediced by Peter Kaslicke and

William FE. bbl p. 9-68. Boetn de Argueolgia PUCP

No.4, Fondo Edo Poles Univeriad Caria del

Peri Lima .

12006 Landsape of Power: A Nerwork of Palaces in che Middle

Horizon Peru. In Places and Power in the Americas: From

Peru to the Nerinest Coast edited by Jes . Chrisie and

Pac) Sar pp. 44-98. University of Texas Press, Ain,

‘bel, Wiliam Hand Goedon McEwan

tat A History of Huai Seudies and Introduction to Curtent

Tncerprecations. In Hurt Pall Organisation: Priore

Monumental Architecture and State Gaverament: Round

Tile Hel at Dumbarton Oat, May 17-1 its ed by

Welland G. Mea, ppc Dumbarton Oaks Research

Library and Colleton, Washingeon, D.C

‘ibel Wiliam Hand Kahana} Schreiber

1978 Was Waa Sate? mericn ntigiy alsa,

‘bel, Wim Hand Alessi Vanich

100g Experiencing the Cities of Was and Tiwanak, In dndeon

Arbaclgy, edited by Helin Sibean, pp. 67-18

Blcovel, Malden, Masachases.

s, Blabeth and Daniel Guero

1987 San Ua so Waren el vllede Chilo, Gata Arquliie

Andina 435-8.

Jing js, and Willy Yeper Saree

2001 Architecture, Loc Elie, and impcvl Enanglemenes The

‘Waci Empire and Corahuas lle of Peru Journal of Fd

Araecog 8 }a319

Kosok, Pal

1965, Wire, Land, and Len nce Por Long and Univesity

Pres, New York.

Krzanowat, Ards (editor)

typ1 Eni sobre Lact Chance. Universidad Jogucona,

Krakow:

Lawrence Deni Land SethaM. Low

8990 The BuileEnviroament and Spal Form, dona Reine of

Aachropelegy 9455-595

Mefvan, Goton E

4996 Archeological Ivesgaons Pill, Wisi Sein er.

Jounal of Fala Archaeology 1 165-186.

‘Mackey, Carol J, and Ulana Klymyshyn

‘990 The Southern Fonte of he Chima Emp. a The Norcbrn

Dynastin: Kinghip end Seataraft in Chime, edited. by

Michael E. Moseley and Alana Cordy-Calins, p. 195-226

Dunbacon Oaks, Washingson, DC.

ened. Dorochy

1977 The rchacalog of Peron he Woke Ma Ube RH. Lowie

Mascum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley

Misa Guise, Jaime and Mantel Meio Jiménez

1986 Incenar exer de monument arueligs dl ule de

Hua Seioatio de Historia Ral Andina, Univesad

ional Mayor de San Mas, Lima

Moo fry

1996 Aicitecre and Pur in he Aan Andes Te Arcaclegy

of Public Buldng. New Sead in Aachacoloy. Cambridge

Universi Press, Cambridge

Moris, Craig and Donald. Thompson

tg70 Huanoeo Vigjo: An Inca Adminsaive Center. American

Aig (3344-963.

Mosely. Michael

1975, The Martine Foundation of Andean Cieation Cuings,

Menlo atk, Calon,

Moseley, Michael E, Robert A. Fldma, Pal S. Goldstein and Luis

‘Wacanabe

‘991 Colonies and Conquest: Tahuanac and Hua in Moqugua,

In Hari dinsraive Sractare: Preborc Monamental

Arcbictare and Sta Government, eed by William H.

‘ball and Gordon F MeEvan pp i!-140: Dambartn Oaks

Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C

MECING TOGETHER THEMIDOLE 185

Nin, Ki and Ahr Ruiz

2004, Proyecto de inveigacién arquoldgca: Valle de Hugura,

Per, Fina repore submited tthe Initate de Nacional de

Cec, er.

Nelson, Kit and Arco Ruiz Bada

2010 The Chancay Tomb of Rontoy, Pera. Antiquity $a(s33) Project

Gallery Hecronic Docume, wewansguiyacuk’projgll/

ekonsy/, esd Jae, or,

Pathe Bradley.

xect At the Edge of Empite: Concepuaising Asya Anatolian

Frontier e700 BC. Journal of Anchoploialdrbacigy

uls}s7t-s95.

2606 Toward an Underanding of Bordedand Processes American

Ansigty 10)7.

Perales Mangia Manvel

1006 Proectodeimesigci “Reconocimint srqucgioen el

val boc Pave (Lima —Perd) Final epore submited

thelnsato Nacional de Clr, Lima,

2007 Proyecto de inveigacin “Reconocimientoarqucligco

cel vale de Foren (Lima-Ancash, Pera” Fra report

submited o:he lino Nacional de Clk, Lime

Piece Te, Stephani Stacy Michelle Dunn, and AsheyKerackan

Heston

ro Proyecto de nverigacin Arquebogia en el Valle de Husa

Costa Norenal del Peri, Final report submited tothe

Jnsiwo Nacional de Calera Lima.

Plog Stephen

1985 Analysis of Sil in Accs, dnl Revi of thraplogy

na

1991 Chyonclagy Copsriction and che Sady of Pebissorc

alee Change jnrnalf Fld Arebalgy17:439-436

Reis Johann Wilhelm and Alphonse Stacbel

1880. TheNewopoliofdncan in Por Ashes, London.

Roe, PterG

1995 See, Socery, Myth, and Stace. In Sl Society, and

Pason, edited by Chricopher Car and ill E. Neil pp

27-76 len Pres New Yor,

Roseworowal de ier Canseco Mars

saps Pahacamacyel ser del: lag: Una nadinmleneria.

Insitute Estudos eran Lima

RuisEsuads, rro

1999 Tewrosaqueagie de Huach. Coleccion Deca Huscho

Fer,

Role Esvads, Arero and M. Domingo Toero

1978 Acaray,foralece yunge del elle de Huaure. Comite de

Education del Cooperative de Ahorro y Crédito "San

Bartloma Huscho, Per.

Rois Eseada, Arti, andKitNeon

200 Proyeco de imestigacién arqueldgica enc valle de Hua,

costa centel del Per. Final epore submited to he nse

de Nacional de Cur, Pew

Schrier Kehaig

1gg2 Wart Inpro i» Middle Horizon Por. Antopoloiel

Papers No. 82. Maseum of Anthropology, Univesity of

Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Shady, Ruch and Arr Rae

179 Evidence for Interregional Relonships during the Middle

Horton on the North-Central Coat of Per, Aeron

Antiquity 44(4):676-685.

186 KITNELSON, NATHAN CRAIG, AND MANUEL FERALES

Shady Sols Ruth

1993 Del Aric al Formatvo en los Andes cetales. Revie

Aadina s2305-38

1995 La neolidzzign en lot Andes centrale y los ergees del

sedentssno,ademesicctn ye dicncn socal Sutin

35.

1997 Le edad sagrade de Carl Sipe on ls albrs dela

Cilcain en el Peri Universidad Nacional Mayor de San

Marcos Lin

19990 La religion como forma decohsin social manejo politico

enloslbores dels cine en el er. Bolin de Mase de

Arqucegay Arreplgi (9).

1999 Flat de Cara: El conju sil més Ancgu de Armée.

Bok del Mas de relia Anrep (thas.

1999¢ El sustento econdmico del sugimieao de la civizacién

en el er, Bolen del Mate de Arnley Anropoepa

(uae

1959d_ Las orgenes dea ean yl fomacin del estado ene

Perdis Les evdencassrgueolgias de Carl Supe, primera

pate. Bolein del Museo de Arguesloga y Aniepologia

a{n)a—4.

20001 Rimal de entertamino de un eit en sco esdencal

‘Ae Cara Supe In El Prado cone Pes aca unt

dni de soins eied by Pee Kak, p18

Bolen de Argueologis PUCP No, 5. Pontificia Unies

Calica del Per Lima

scab Las rigens de lac y a fomaci del exado ene

Peri: Las evidencisarqueolgices de Carl Supe, segunda

pce Bolen ded Mawes de Agua Aral 0)2-7

2o0ce Prices moreors del sociedad de CaalSope durant el

‘Aeaio Turi. Blt dd Muse de Arquelogley tropa

(sats,

Shady Sol, Ruth Jonashan His and Winfed Ceamer

2001 Dating Carla Prceraie Urban Centrin the Supe Valley on

che Cenral Coast of Per. Sienegicase726

Shimada, at

sgp1 Pachacamac Archaologys Retospect and Prospect. In

Puchacaae: A Reprint ofthe ges Edton by Max Uhl

ved by Izumi Shinada, pp. aici. Uneity Maseum of

Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Penasylanis

Philadelphia,

Shimada, lumi, Cry B. Schl, Lonnie G. Thompson and Elen

Mealy-Thompuon

29p1 Calumet of Severe Droughs in che Prehistoric Andes

Application of 3 asootear Ie Core Peipation Recor

Wild Archaea 219)247- 70

Song, Wiliam D, and Gordon R. Wiley

1943. Atchicologil Note onthe Cental Coast th Accolia

Sais in Pru pe1-g42, edited by Willan D, Song,

Gordon R. Wille, and John M. Cobe, p.1=26 Columba

University res New Yok,

Scames Louis.

1952 Investigaciones de super en Caldera (alle de Hosur).

Ravi del Maven Nacional 38-6,

“Thomas David H.

1975 Nome Sampling in Archaeology Upthe Creek wihowr 2

‘Site. Sampling in Archaoloy,edited by James W. Mule,

p61 Unversity of Aizona Pes Taso.

“Tipevch, Nichols

so04a Febilcy by Design: How Mobile GIS Meets the Necds

of Aschacologieal Survey. Cartgraphy and Geegrphical

Information See 3257-56

sooab Inerfces: Mobile GIS in Archacologcal Sucve. Sd

Arce Rcd 437-2.

2006 Mobily and Exchange inthe Andean Preceraic sight

from Obsidian Sadie. Paper presented a he rise Anna

Mesing ofthe Sociery for American Archaeology San Jan,

Poet Ric,

Ule Max

1903 Puhacamac. Report ofthe Wiliam Pepper, MD, LD,

Persian Exeion of 6 Univer of Peanprania Pres,

Philadelphia

1935 Reporton Bloons at Supe (Append ose Uhl Poctery

Colleton from Supe, by Alted Keoebe). Uniseniy of

Cabra Pitionin American Aral and Ethnlgy

26(6)as7-365.

van Zyl lob

to01 The Shule Radar Topography Mision (SRTM): A

Breakthrough in Remote Sensing of Topography. dete

Aaron 4859-56,

eg Cee Sar Lafoe R

0032 Arqutecura plea del Arico Tino cnc! ale de Fralera

Reflexiones sobre las sociedades comple empranss eh

cone ceneal Argues Scdad 192-56

00s Rival and Archietireina ConrertofEmergeneCompleiy:

-Aerpezive from Cewo Lanpay a Late archi Se in che

Cowl Andes, Unpblihed PRD. drain, Universi of

‘aon, Taio,

2006 spacios y pricticas tales en un context de compleidad

emergent, Paper presented a the V Simposo lternacional

de Arqueologia: Proceos y Expresiones de Poder, densidad,

yy Orden Tempranos en Sudamésiea, Ponifica Universidad

(Caria del Per, Lima,

2007 Construction, Labor Organization, and Feasting during

the Late Archale Period in the Cental Andes Journal of

Anthropological Arhsclegy 6330-172

‘Vege-Centeno Sar-Lafose, Rafa, LF Villacoet, LE. Ceres, and

G. Matcote

998 Arquitectura monumental cempeana en el valle medio de

Foralea. Bolen Arguesigicax19-258

Vegr-Centeno Sara afose, RM. dC, Vga Dulenco, and P Lands

Cragg

2006 Muectesviolentas en vers de ancestos: Enos rardis en

Cerro Lampay. rquelogiay Sociedad 1255-172,

Willams, Pick Ryan

oot Cesro Bail: A Wari Center on che Tiwanaku Frontier. Latin

American Antiquity 069-8

Whighe, Heny , and Gregory A, Johnion

1975 Popolation, Exchange and Eadly Seate Formation in

Souchvestern ran, merien Anthropologist 7267-289.

Zeehencer, Elobiera

1988 Subsistence Satgis io the Supe Vlleyof che Peruvian Ce

«tal Coase during the Complex Peceramic and Ini Peids

Unpublished PRD. dissertation, University of California,

Lot Angles.

imma, Pul|

1995 The Unartian Frontier as an Archaeological Problem. In Neo

Ausrian Geography, edited by Mario Liven, p, 171-180,

Universita di Roma, La Sapienza Roms, Rome.

PIECINGTOGETHERTHEMIDDLE 187

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)