Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Politics, Philosophy & Economics: Rothbard and Hoppe's Justifications of Libertarianism: A Critique

Politics, Philosophy & Economics: Rothbard and Hoppe's Justifications of Libertarianism: A Critique

Uploaded by

Julián David González CruzCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 2015 Cdi Final CoachingDocument24 pages2015 Cdi Final CoachingDioner Ray95% (22)

- (Oxford Moral Theory) Guy Fletcher, Michael Ridge - Having It Both Ways - Hybrid Theories and Modern Metaethics (2014, Oxford University Press)Document321 pages(Oxford Moral Theory) Guy Fletcher, Michael Ridge - Having It Both Ways - Hybrid Theories and Modern Metaethics (2014, Oxford University Press)Septi Lastiani100% (2)

- Charles Beitz Human Dignity in The Theory of Human RighsDocument32 pagesCharles Beitz Human Dignity in The Theory of Human RighsLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaNo ratings yet

- El gran Libro de la Ciencia Política: EL GRAN LIBRO DE...From EverandEl gran Libro de la Ciencia Política: EL GRAN LIBRO DE...No ratings yet

- All About Philippine EpicsDocument39 pagesAll About Philippine EpicsEnzo Pilot ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Getting Libertarianism Right (2018) by Hans HoppeDocument126 pagesGetting Libertarianism Right (2018) by Hans HoppeIrene RagonaNo ratings yet

- T O P R: AC R H N R: HE Rigin OF Roperty Ights Ritique OF Othbard AND Oppe ON Atural IghtsDocument9 pagesT O P R: AC R H N R: HE Rigin OF Roperty Ights Ritique OF Othbard AND Oppe ON Atural Ightsklen_abaNo ratings yet

- Abdel Nour (2004) Farewell To Justification Habermas, Human Rights, and Universalist MoralityDocument25 pagesAbdel Nour (2004) Farewell To Justification Habermas, Human Rights, and Universalist MoralityMikel ArtetaNo ratings yet

- Ethics of LibertyDocument336 pagesEthics of LibertyJMehrman33No ratings yet

- The Will To SynthesisDocument21 pagesThe Will To SynthesisFelipeNo ratings yet

- A Meaningful Score Hartman V RokeachDocument20 pagesA Meaningful Score Hartman V RokeachClaudia MorenoNo ratings yet

- Speech, Media, and Ethics - The Limits of Free ExpressionDocument240 pagesSpeech, Media, and Ethics - The Limits of Free ExpressionCancino, Samantha B.No ratings yet

- Hoppe Reading ListDocument6 pagesHoppe Reading ListClinton MillerNo ratings yet

- Ethics of Liberty PDFDocument2 pagesEthics of Liberty PDFStuartNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Public Affairs 2011 NUSSBAUM Perfectionist Liberalism and Political LiberalismDocument43 pagesPhilosophy Public Affairs 2011 NUSSBAUM Perfectionist Liberalism and Political LiberalismAlguien AnonimoNo ratings yet

- Speculative Realism and Public Theology - John ReaderDocument12 pagesSpeculative Realism and Public Theology - John ReaderBrett GustafsonNo ratings yet

- Perfectionist LibralismDocument43 pagesPerfectionist LibralismDiem PhanNo ratings yet

- Rothbard - Ethics of LibertyDocument336 pagesRothbard - Ethics of LibertyAna-Maria Anghelescu100% (3)

- Teori Keadilan John RawlsDocument14 pagesTeori Keadilan John RawlsA Khudori Soleh100% (8)

- James Bohman - Pluralism and The Pragmatic Turn - The Transformation of Critical TheoryDocument465 pagesJames Bohman - Pluralism and The Pragmatic Turn - The Transformation of Critical TheoryLuciano T. FilhoNo ratings yet

- Is Political Authority An Illusion A Debate Little Debates About Big Questions - Michael Huemer, Daniel LaymanDocument219 pagesIs Political Authority An Illusion A Debate Little Debates About Big Questions - Michael Huemer, Daniel Laymanwagiham556No ratings yet

- Campbell Et Al. 2019 TCSDocument17 pagesCampbell Et Al. 2019 TCSCarlos Augusto AfonsoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Review of International StudiesDocument20 pagesCambridge University Press Review of International StudiesIkbal PebrinsyahNo ratings yet

- Justin A. Elardo, Marx, Marxists, and Economic AnthropologyDocument8 pagesJustin A. Elardo, Marx, Marxists, and Economic AnthropologySotiris LontosNo ratings yet

- S5 Rubin Rational Choice Rat Choice PDFDocument37 pagesS5 Rubin Rational Choice Rat Choice PDFSharunSUttamchandaniMNo ratings yet

- Teori HabermasDocument51 pagesTeori HabermasedonisNo ratings yet

- Chaper 6 Justice in RobesDocument28 pagesChaper 6 Justice in Robesjk1409No ratings yet

- EOp EcPhil 2012Document37 pagesEOp EcPhil 2012andrea pineda galazNo ratings yet

- DISCOURSE THEORY AND HUMAN RIGHTS - Robert Alexy PDFDocument23 pagesDISCOURSE THEORY AND HUMAN RIGHTS - Robert Alexy PDFAnonymous 1CH7B6Y100% (2)

- R. Dworkin, Hart's Postscript and The Character of Legal Philosophy'Document25 pagesR. Dworkin, Hart's Postscript and The Character of Legal Philosophy'Iosif KoenNo ratings yet

- Lesson 7.-Theories of Justice (2) : 1. - Left and RightDocument11 pagesLesson 7.-Theories of Justice (2) : 1. - Left and RightJTNo ratings yet

- Richard Rorty's Critique of Horkheimer and AdornoDocument2 pagesRichard Rorty's Critique of Horkheimer and AdornoheliloNo ratings yet

- Textbook Hobbesian Applied Ethics and Public Policy 1St Edition Shane D Courtland Editor Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Hobbesian Applied Ethics and Public Policy 1St Edition Shane D Courtland Editor Ebook All Chapter PDFoscar.wiley826100% (12)

- Kants Humanistic Business EthicsDocument20 pagesKants Humanistic Business EthicsaggarwalmeghaNo ratings yet

- Textbook Emancipation Democracy and The Modern Critique of Law Reconsidering Habermas 1St Edition Mikael Spang Auth Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument54 pagesTextbook Emancipation Democracy and The Modern Critique of Law Reconsidering Habermas 1St Edition Mikael Spang Auth Ebook All Chapter PDFdavid.wasserman776100% (14)

- REVIEW of "Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari" - by Ismael Al-Amoudi For Organization StudiesDocument9 pagesREVIEW of "Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari" - by Ismael Al-Amoudi For Organization StudiesdrumetNo ratings yet

- What Is To Be DistributedDocument8 pagesWhat Is To Be DistributedrobertoNo ratings yet

- Valentini - Ideal - Vs - Non-Ideal TheoryDocument14 pagesValentini - Ideal - Vs - Non-Ideal TheoryAntonio Pablo QuintanillaNo ratings yet

- Di Iorio Mises and PopperDocument36 pagesDi Iorio Mises and PopperecrcauNo ratings yet

- The State of No Nature: Thomas Hobbes and The Natural World: January 2014Document18 pagesThe State of No Nature: Thomas Hobbes and The Natural World: January 2014MiyNo ratings yet

- Capitalism As A Space of Reasons AnalytiDocument25 pagesCapitalism As A Space of Reasons AnalytiSebastian LeonNo ratings yet

- Hobbes Locke Rousseau M06Document6 pagesHobbes Locke Rousseau M06stewe wondererNo ratings yet

- Bagg-Anti-Essentialist Subject DemocracyDocument24 pagesBagg-Anti-Essentialist Subject DemocracyWalterNo ratings yet

- Hobbes Studies Natural Justice Law and Virtue in Hobbess LeviathanDocument31 pagesHobbes Studies Natural Justice Law and Virtue in Hobbess LeviathanMalachiasz CzechowiczNo ratings yet

- POL 203 Intro To Western Political PhilosophyDocument202 pagesPOL 203 Intro To Western Political PhilosophyShan Ali Shah100% (1)

- Western Political Philosophy - 2Document202 pagesWestern Political Philosophy - 2Asif MirzaNo ratings yet

- As Free and as Just as Possible: The Theory of Marxian LiberalismFrom EverandAs Free and as Just as Possible: The Theory of Marxian LiberalismNo ratings yet

- Towards A Climate Change Justice TheoryDocument26 pagesTowards A Climate Change Justice Theorytim clayNo ratings yet

- Postcolonialism and Global JusticeDocument15 pagesPostcolonialism and Global JusticeDerek Williams100% (1)

- LP 9 2 5Document28 pagesLP 9 2 5Antônio DiasNo ratings yet

- New Environmental Ethics BookDocument6 pagesNew Environmental Ethics BookMagistrandNo ratings yet

- Critical Social Theory. An Introduction and CritiqueDocument22 pagesCritical Social Theory. An Introduction and CritiqueJosé LiraNo ratings yet

- Hobbes Conception of Human Nature & Its Social Contract: A Project Report OnDocument16 pagesHobbes Conception of Human Nature & Its Social Contract: A Project Report OnDevendra DhruwNo ratings yet

- Justice As Mutual Advantage and The Vulnerable - Peter VanderschraafDocument30 pagesJustice As Mutual Advantage and The Vulnerable - Peter VanderschraafIgor DemićNo ratings yet

- Murray N. Rothbard - Toward A Reconstruction of Utility & Welfare EconomicsDocument41 pagesMurray N. Rothbard - Toward A Reconstruction of Utility & Welfare EconomicsJumbo ZimmyNo ratings yet

- Essays on Philosophy, Praxis and Culture: An Eclectic, Provocative and Prescient CollectionFrom EverandEssays on Philosophy, Praxis and Culture: An Eclectic, Provocative and Prescient CollectionNo ratings yet

- Art, Morality and Human Nature: Writings by Richard W. BeardsmoreFrom EverandArt, Morality and Human Nature: Writings by Richard W. BeardsmoreNo ratings yet

- The Classical Roots of Ethnomethodology: Durkheim, Weber, and GarfinkelFrom EverandThe Classical Roots of Ethnomethodology: Durkheim, Weber, and GarfinkelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Refutación AutopropiedadDocument14 pagesRefutación AutopropiedadJulián David González CruzNo ratings yet

- 1887 19510-Master ThesisDocument55 pages1887 19510-Master ThesisJulián David González CruzNo ratings yet

- Foundations LibtardDocument34 pagesFoundations LibtardJulián David González CruzNo ratings yet

- Communist Reading List (Ultra-Left)Document30 pagesCommunist Reading List (Ultra-Left)Julián David González Cruz100% (1)

- Loren Goldner - Amadeo Bordiga, The Agrarian Question, and The International Revolutionary MovementDocument28 pagesLoren Goldner - Amadeo Bordiga, The Agrarian Question, and The International Revolutionary MovementJulián David González CruzNo ratings yet

- ScaleAnarchy PDFDocument20 pagesScaleAnarchy PDFJulián David González CruzNo ratings yet

- Looting As A Symptom of An Ill SystemDocument1 pageLooting As A Symptom of An Ill SystemJulián David González CruzNo ratings yet

- A Report On The Study of Gram Kachahari in BiharDocument31 pagesA Report On The Study of Gram Kachahari in BiharSubodhksrm100% (2)

- Chapter 1 None CompressDocument9 pagesChapter 1 None CompressiadcNo ratings yet

- International Business Opportunities and Challenges in A Flattening World Version 3 0 3rd Carpenter Solution ManualDocument11 pagesInternational Business Opportunities and Challenges in A Flattening World Version 3 0 3rd Carpenter Solution ManualJenniferNelsonfnoz100% (41)

- Msds Benzyl AlcoholDocument8 pagesMsds Benzyl AlcoholFrendiiNo ratings yet

- Proforma Invoice - Bruno Rodrigues - PI - BRU.01.09.2023 - QU408716Document4 pagesProforma Invoice - Bruno Rodrigues - PI - BRU.01.09.2023 - QU408716Giovanni JorgeNo ratings yet

- Desmodur VL 50 - en - 00830437 17844529 19840335Document3 pagesDesmodur VL 50 - en - 00830437 17844529 19840335rosarioNo ratings yet

- Ching Vs RodriguezDocument4 pagesChing Vs RodriguezbimbyboNo ratings yet

- GGSR Kant and RawlDocument30 pagesGGSR Kant and RawlCarl Bryan AberinNo ratings yet

- Respestas A Las Canciones de Topnot, Pearson, My Englis LabDocument6 pagesRespestas A Las Canciones de Topnot, Pearson, My Englis LabjessicaNo ratings yet

- 2017 BCSC 1226 (CanLII) - H.C.F. V D.T.F. - CanLIIDocument3 pages2017 BCSC 1226 (CanLII) - H.C.F. V D.T.F. - CanLIICharles BinghamNo ratings yet

- M. G. RamachandranDocument8 pagesM. G. Ramachandranayushonline2No ratings yet

- 1.history of Banking LawDocument13 pages1.history of Banking LawneemNo ratings yet

- Adult STS Jacob's Sojourn in Laban's House - Lesson 19Document3 pagesAdult STS Jacob's Sojourn in Laban's House - Lesson 19Ichechuku EnwukaNo ratings yet

- Bob Moore Lawsuit Against ICE, DBP, DHS For FOIA ViolationsDocument66 pagesBob Moore Lawsuit Against ICE, DBP, DHS For FOIA ViolationsDebbie NathanNo ratings yet

- Women in Military DebateDocument15 pagesWomen in Military DebateRebecca Isabel Ponce Cepeda100% (1)

- Malcom X Militant Black LeaderDocument111 pagesMalcom X Militant Black LeaderDada Poskovic100% (1)

- Executive Order 2023Document14 pagesExecutive Order 2023Jovelyn AlaNo ratings yet

- Hero Vinoth Minor Vs Seshammal - AIR 2006 SC 2234Document10 pagesHero Vinoth Minor Vs Seshammal - AIR 2006 SC 2234sankhlabharatNo ratings yet

- Gazette Notification Diploma Engineers Service Rule-2012.Document8 pagesGazette Notification Diploma Engineers Service Rule-2012.us dNo ratings yet

- Term 2 - Grade 8 Finance NotesDocument4 pagesTerm 2 - Grade 8 Finance Notesris.aryajoshiNo ratings yet

- NRIA Summary C D Order 6-21-2022Document63 pagesNRIA Summary C D Order 6-21-2022RSNo ratings yet

- Deed of AssignmentDocument7 pagesDeed of Assignmentmayurisurti32No ratings yet

- Kirushika 0037 Eway BillDocument1 pageKirushika 0037 Eway BillTechnetNo ratings yet

- King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand, 1927-2016Document5 pagesKing Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand, 1927-2016Tom ElderNo ratings yet

- Delhi Public School:: An Online Cryptic HuntDocument4 pagesDelhi Public School:: An Online Cryptic HuntRishika SinghNo ratings yet

- Gender Based ViolenceDocument45 pagesGender Based ViolencejhayNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Six Selected Master's Theses by College of Europe StudentsDocument304 pagesSix Selected Master's Theses by College of Europe StudentsLiubomir GuțuNo ratings yet

Politics, Philosophy & Economics: Rothbard and Hoppe's Justifications of Libertarianism: A Critique

Politics, Philosophy & Economics: Rothbard and Hoppe's Justifications of Libertarianism: A Critique

Uploaded by

Julián David González CruzOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Politics, Philosophy & Economics: Rothbard and Hoppe's Justifications of Libertarianism: A Critique

Politics, Philosophy & Economics: Rothbard and Hoppe's Justifications of Libertarianism: A Critique

Uploaded by

Julián David González CruzCopyright:

Available Formats

Politics, Philosophy & Economics

http://ppe.sagepub.com/

Rothbard and Hoppe's justifications of libertarianism: A critique

Marian Eabrasu

Politics Philosophy Economics published online 22 November 2012

DOI: 10.1177/1470594X12460645

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://ppe.sagepub.com/content/early/2012/11/22/1470594X12460645

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

The Murphy Institute of Political Economy

Additional services and information for Politics, Philosophy & Economics can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://ppe.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://ppe.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Nov 22, 2012

What is This?

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Article

Politics, Philosophy & Economics

1–20

Rothbard’s and ª The Author(s) 2012

Reprints and permissions:

Hoppe’s justifications sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1470594X12460645

ppe.sagepub.com

of libertarianism: A

critique

Marian Eabrasu

Groupe ESC Troyes en Champagne, France

Abstract

Murray N. Rothbard and Hans-Hermann Hoppe build their libertarian theory of justice

on two axioms concerning self-ownership and homesteading, which are bolstered by two

key arguments: reductio ad absurdum and performative contradiction. Each of these

arguments is designed to demonstrate that libertarianism is the only theory of justice

that can be justified. If either of these arguments were valid, it would prove the libertar-

ian claim that the state is an unjust political arrangement. Giving due weight to the

importance of the libertarian anarchist claim, this article exposes and criticizes the

arguments that substantiate it.

Keywords

homesteading, libertarianism, performative contradiction, reductio ad absurdum,

self-ownership

Perhaps, property, the rule of law, and free markets are, after all, intrinsically valuable. But I

don’t know that could be demonstrated to someone who thought otherwise. (Barry, 1989: 127)

Introduction

This article offers a critical assessment of two arguments (reductio ad absurdum and

performative contradiction) formulated by Murray N. Rothbard (1996) and

Corresponding author:

Marian Eabrasu, Champagne School of Management, Department of Economics, Finance and Law, 217, avenue

Pierre Brossolette, BP 710, Troyes, Cedex 10002, France

Email: marian.eabrasu@get-mail.fr

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

2 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

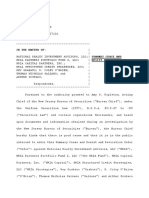

Table 1. xxxxxxx

THE SELF-OWNERSHIP AXIOM THE HOMESTEADING AXIOM

‘The right to self-ownership asserts the absolute ‘Every man has the right to own . . . whatever

right of each man, byvirtue of his (or her) property he has‘created’ or gathered out of

being a human being, to ‘own’ his orher own the previously unused, unowned state

body; that is, to control that body free of ofnature. . . . The pioneer, or homesteader,

coercive interference’(Rothbard, 1996: 33). is the man who first brings thevalueless

unused natural objects into production and

use’ (Rothbard,1998: 49).

THE REDUCTIO AD ABSURDUM ARGUMENT

‘Consider, too, the consequences of denying each man the rightto own his own person. There are

then only two alternatives: either (1) acertain class of people, A, have the right to own another

class, B; or (2)everyone has the right to own his own equal quotal share of everyone else.

. . . The libertarian . . . rejects these alternatives and concludes by adopting as hisprimary axiom

the universal right of self-ownership’ (Rothbard, 1996:34).

THE PERFORMATIVE CONTRADICTION ARGUMENT

‘Any person who would try to dispute the property right in hisown body would become caught up

in a contradiction, as arguing in this way andclaiming his argument to be true, would already

implicitly accept precisely thisnorm as being valid’ (Hoppe, 2006: 318).

Hans-Hermann Hoppe (1989) to justify the monist claim that only the libertarian the-

ory of justice grounded on the axioms of self-ownership and homesteading is morally

acceptable (Hoppe, 2006: 338) (see Table 1).

Hoppe (1998; 2006: 381–99), who is ‘typically regarded as one of the foremost heirs

of Rothbard’s legacy’ (Callahan, 2012: 9), entirely endorses the Rothbardian insights

and Rothbard (1988, 1990) fully agrees with the argument formulated by Hoppe. Within

the variety of libertarian theories, we can therefore legitimately speak of the Rothbard–

Hoppe justifications of libertarianism. If the arguments from reductio ad absurdum and

performative contradiction are valid, then any pattern of resource distribution that does

not follow from the axioms of self-ownership and homesteading would become ipso

facto unjust. With these two axioms in hand, Rothbard (1998: 60) dismisses as immoral

any form of non-provoked coercion. He maintains, for instance, that conscription is slav-

ery (Rothbard, 1998: 83) and that taxation is theft (Rothbard, 1998: 172). It is precisely

such radical claims that lead scholars explicitly to state their ‘hatred’ of libertarianism

(Haworth, 1994: 133).

However, most scholars who disagree with the radical conclusions of libertarianism

largely ignore the Rothbard–Hoppe justifications (Friedman, 1992) and usually target

the ‘essentially unargued affirmation of each person’s right over himself’ (Cohen,

1995: 70). This disregard for the Rothbard–Hoppe justifications greatly weakens the

effect of the current critiques against libertarianism (Attas, 2005). Moreover, such lack

of interest among the detractors of libertarianism is highly disappointing when we

know that numerous contemporary libertarians are firmly convinced that these argu-

ments are valid and explicitly mobilize them to justify libertarianism (Block, 1996;

Hülsmann and Kinsella, 2009; Kinsella, 2002b). Block’s 2010 collection, I Chose

Liberty: Autobiographies of Contemporary Libertarians, provides concrete testimo-

nies of the influence of these arguments among libertarian scholars. In any event, those

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 3

who disagree with the libertarian claims cannot simply ignore the Rothbard–Hoppe

arguments.

To be sure, each argument has already been amply discussed by distinguished liber-

tarian scholars. Osterfeld (1977, 1983), Hospers (1982), Horn (1984), Barry (1995), and

Kyriazi (2004) indicate the limits of the justification by reductio ad absurdum, initially

formulated by Rothbard, while Rasmussen (1980) and Casey (2009) defend it. Friedman

(1988), Osterfeld (1988), Richman (1988), Steele (1988), Yeager (1988), Lomasky

(1989), Terrell (2000), and Godefridi (2004) criticize the justification by performative

contradiction, initially formulated by Hoppe. Meng (2002), Kinsella (2002a), and

Gordon (2006) review the history of the debate and defend this libertarian justification.

Rothbard (1988, 1990) and Hoppe (2006: 399–418) themselves have done significant

work on improving their own arguments and replying to some of their critics. More

recently, a seminal article by Gene Callahan and Robert Murphy (2006) drastically

criticized Hoppe’s argument from performative contradiction. The replies to this specific

critique formulated by Van Dun (2009), Eabrasu (2009), and Block (2011), however,

implicitly show that the debate over libertarian justification is still open.

Given this state of the art, a reasonable question springs out: What should the reader

expect from a new attempt to revisit the debate? On the one hand, the specificity of this

new analysis rests on its unbiased aim, as it has no interest in the success or failure of the

libertarian monist claim. This article takes the Rothbard–Hoppe justifications seriously,

so as to propose a fair description of the arguments that bolster it. This should prevent

future rejoinders similar to those usually addressed to the existing critiques, which often

claim a misconstruction of these arguments. On other hand, this critique of the

Rothbard–Hoppe arguments mainly focuses on their soundness, setting aside the debates

over essentially contested concepts such as ‘person’, ‘property’, ‘aggression’, and so on.

This strategy should enable us to isolate the specific limits of these arguments and to

avoid rejoinders indicating a different interpretation of these notions. It is mainly for

these two reasons that this new line of critique should be more successful than its

forerunners.

Moreover, even those readers who already consider these arguments to be flawed (for

whatever reason) may find an interest in reading this article, as the importance of this

discussion goes beyond the inner circle of libertarian scholars. The current article not

only examines the arguments from reductio ad absurdum and self-ownership as such,

but also and especially their success in supporting the libertarian monist claim. The

stakes of the debate on the justification of libertarianism extend to the theory of political

obligation (Sylvan, 2007: 264). Indeed, if at least one of the two libertarian lines of

defence (reductio ad absurdum and performative contradiction) could withstand critical

scrutiny, then there would be no such thing as political obligation. Rothbard (1998: 172)

concludes that the state is an unjust political arrangement, indistinguishable from any

criminal organization. Hence, a refutation of the Rothbard–Hoppe arguments should

nuance the aforementioned libertarian claim and shed new light on the theory of political

obligation.

Several steps will be taken by this article to achieve its aim. First, the article replies to

Rothbard’s reductio ad absurdum argument by showing that the alternatives to the

self-ownership axiom are not absurd. Second, it shows that reductio ad absurdum is

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

4 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

unsuccessful even when it is customized by Hoppe for the homesteading axiom. Third, it

points to the failure of the performative contradiction argument in justifying the

self-ownership axiom. Finally, the conclusion will assess the implications of this critique

for moral and political theory.

The justification of the self-ownership axiom by reductio ad

absurdum

Reductio ad absurdum is usually considered a basic method of argumentation (Foster,

2007: 229–31; Martinich, 2005: 121–7). Initially employed in geometry (Heath,

2006), it is widely used in philosophy (Hare, 1993: 113–31; Kant, 1996: A446/B474;

Plato, 1998: 128d, 2006: 338c–343a). Rothbard uses reductio ad absurdum in order to

provide an indirect defence of the self-ownership axiom (to prove that its alternatives are

absurd). His demonstration follows three main steps. First, he assumes, for the sake of

the argument, that the self-ownership axiom is false. Second, he lists its alternatives.

Third, if he succeeds in showing the absurdity of all alternatives, then he can conclude

that only the right to self-ownership can be justified. Inevitably, further attention is

required when this argument is applied in ethics. Since it is very likely that the proposi-

tion to be demonstrated in ethics may have several alternatives and not just one, the

argument would be fallacious if an alternative were omitted. Furthermore, when this

argument is used in ethics, the propositions to be demonstrated may be normative.

Hence, it is important to avoid the ‘is-ought problem’ (Hume, 1952: 177–8) and to

refrain from deducing normative statements from descriptive statements.

Rothbard’s exposition (1998: 45–6) of reductio ad absurdum to justify the

self-ownership axiom goes as follows:

Let us ... concentrate on the question of a man’s ownership rights to his own body. Here are

two alternatives: either we may lay down a rule that each man should be permitted (i.e. have

the right to) the full ownership of his own body, or we may rule that he may not have such

complete ownership. If he does, then we have the libertarian natural law for a free society as

treated above. But if he does not, if each man is not entitled to full and 100 percent

self-ownership, then what does that imply? It implies either one of two conditions: (1) the

‘communist’ one of Universal and Equal Other-ownership, or (2) Partial Ownership of One

Group by Another – a system of rule by one class over another. These are the only logical

alternatives to a state of 100 percent self-ownership for all ... Hence, no society which does

not have full self-ownership for everyone could enjoy a universal ethic. For this reason alone,

100 percent self-ownership for every man is the only viable political ethic for mankind.

Given Rothbard’s formulation of the argument, it is easy to concede that the afore-

mentioned precautions were taken. First, it can be said that all the possible alternatives

are considered. Rothbard (1998: 46) excludes the situation of ‘no-one’s ownership’; on

this precise point, he follows those scholars who consider that control is a necessary con-

dition for ownership (Grunebaum, 1997: 20–25). For instance, the debate over the

ownership of the moon makes sense inasmuch as humans can effectively control this

resource (Pop, 2009: 2–3). Hence, if individual ownership is denied, it follows that there

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 5

is shared ownership – the shares can be equal or not. The difficult part of the argument is

to show why both types of shared ownership entail absurd consequences. Second, Roth-

bard’s defence of the self-ownership axiom is not concerned with the ‘is-ought problem’.

In this argument, ‘the right to self-ownership’ of a person is not deduced from actual

control of his or her own body. The proposition to be demonstrated is already normative:

‘one has the right to own one’s body’. The alternatives are also normative: ‘one ought to

share (equally or not) the ownership of one’s own body’. If the latter norms lead to

absurdity, then, logically, the initial norm must be the only morally acceptable one.

By arguing in this way, Rothbard’s aim is not to establish what is actually the case, but

what ought to be the case. Of course, the major difficulty is to show that the right to

shared (equal or not) ownership of one’s body is absurd.

In order to assess the absurdity of the alternatives to the right to self-ownership, it is

crucial to understand the criterion by which an argument is said to be absurd.

If an ethical goal can be shown to be self-contradictory and conceptually impossible of

fulfilment, then the goal is clearly an absurd one and should be abandoned by all. It should

be noted that we are not disparaging ethical goals that may be practically unrealizable in a

given historical situation; we do not reject the goal of abstention from robbery simply

because it is not likely to be completely fulfilled in the near future. What we do propose

to discard are those ethical goals that are conceptually impossible of fulfilment because

of the inherent nature of man and of the universe. (Rothbard, 2009: 1297)

This conception of absurdity corresponds to the usual interpretation of ‘absurdity’ in

logic. A statement is absurd if it is logically impossible or, as modal logic puts it, neces-

sarily false, that is, false in all possible worlds. It is important to note that this conception

of absurdity is objective, in the sense that it does not depend on what one might subjec-

tively consider as ‘unreasonable’. There are various ways of assessing absurdity, for

instance inconceivability (‘this is a square circle’) and contradiction (‘a circle is not a

circle’). Rothbard uses the former interpretation to assess the absurdity of the alternatives

to the self-ownership axiom in the reductio ad absurdum argument, while Hoppe mainly

focuses on the latter interpretation to assess the absurdity of denying the right to self-

ownership in the performative contradiction argument. Let us now try to understand if

Rothbard succeeds in demonstrating by reductio ad absurdum that the alternatives to the

self-ownership axiom are absurd (that is, conceptually impossible).

The first alternative

Rothbard (1998: 46) explains as follows why the first alternative is unacceptable:

This view ... does have the merit of being a universal rule, applying to every person in the

society, but it suffers from numerous ... difficulties. In the first place, in practice, if there are

more than a very few people in the society, this alternative must break down and reduce to

Alternative (2), partial rule by some over others. For it is physically impossible for everyone

to keep continual tabs on everyone else, and thereby to exercise his equal share of partial

ownership over every other man. In practice, then, this concept of universal and equal

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

6 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

other-ownership is Utopian and impossible, and supervision and therefore ownership of oth-

ers necessarily becomes a specialized activity of a ruling class.

Rothbard considers that the alternative ‘everyone has the right to own everyone’ must

be based on unanimous consent, and he adds that such a situation is not practicable

within a large society. His point seems to be that even if unanimity could be reached

in a society with a small number of members, this would be practically impossible in the

case of a larger society.

It should first be acknowledged that it is not obvious whether impracticability entails

inconceivability. A state of affairs is not absurd by virtue of its being unattainable.

Second, the case here is not one of an absolute impracticability, but rather of partial

impracticability. A patent difficulty will be to find out the threshold that makes it

practically impossible for the members of a society to take unanimous decisions. There

is no obvious agreement on the distinction between a small and a large society. Even if

we suppose that there is only one criterion for distinguishing small and large societies,

the Rothbardian argument would show at best that it is only in certain cases (highly

populated areas) that this solution cannot be applied. At this point, it is important to note

that a partial argument grounded on a variable criterion would be the opposite of

Rothbard’s intention, which is to provide a principle applying to all situations.

To this argument, Rothbard (1998: 46) adds another which is much more incisive:

But suppose for the sake of the argument that this Utopia could be sustained. What then? In

the first place, it is surely absurd to hold that no man is entitled to own himself, and yet to

hold that each of these very men is entitled to own a part of all other men! ... Can we picture

a world in which no man is free to take any action whatsoever without prior approval by

everyone else in the society? Cleary no man would be able to do anything, and the human

race would quickly perish. But if a world of zero or near zero self-ownership spells death for

the human race, then any steps in that direction also contravene the law of what is best for

man and his life on earth.

This argument is in some important aspects very different from the previous one. Let

us split it into three parts: (1) even if the norm ‘everyone has the right to own everyone’

were practicable, it is absurd; (2) this is so, because if applied, this norm will cause the

death of those who have adopted it; (3) this is because in order to perform an action, any

one person will need the agreement of everyone else. At the outset, we should note,

again, that the first part of the argument conflates logical absurdity and practical

impossibility. While Rothbard aims to prove that equal self-ownership is absurd (that

is, logically inconceivable), his argument, if correct, would only prove its practical

impossibility. That said, we must now see if the equal ownership regarding bodies is

indeed practically impossible.

The second part of the argument merely follows the course of his previous argument

based on practicability. In order to constitute a decisive argument, it needs the justifica-

tion of principle that arrives in the third part, when Rothbard explains why equally shared

ownership is unconceivable. He interprets the norm ‘everyone has the right to own

everyone’ as implying that every participant ought to have (1/N) of M (where N is the

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 7

number of participants and M is an object of ownership). What this means precisely is

that were someone to perform an action (M), they would need the agreement of all others

(N–1); but in order to ask for this agreement, they would need a previous agreement from

the others (N–1) and so on.

In a nutshell, asking is itself an action, which could not be performed without the

permission of others. Unless the unanimity is spontaneous or predetermined, the very

action of asking for a unanimous decision requires a previous unanimous agreement.

Moreover, consider M not as a random action, but as a physical part of one person. Take,

for example, M as being vocal cords. Then 1/N of M would mean everyone is entitled to

1/N part of the vocal cords under consideration. Now consider M as being a brain.

Everyone would be entitled to 1/N of any brain. And so on. Since M could represent

infinite elements of human beings and of human actions, the division of property into

1/N parts concerns all possible M’s.

Here is how Hoppe (2001: 201 n. 17) puts it:

If it [equal co-ownership] were adopted all of mankind would perish immediately, for every

action of a person requires the use of scarce means (at least his body and its standing room).

However, if all goods were co-owned by everyone, then no one at any time or place would

be allowed to do anything unless he had previously secured everyone else’s consent to do

so. Yet how could anyone grant such consent if he were not the exclusive owner of his own

body (including its vocal chords) by means of which this consent would be expressed?

Indeed, he would first need others’ consent in order to be allowed to express his own, but

these others could not give their consent without first having his, etc.

At first sight, one can easily agree that it is practically impossible to establish

collective ownership, if this means obtaining the agreement of 7 billion people. Yet, it

is simplistic to consider that collective ownership only exists if it concerns all existing

human beings and if it applies to everything. Collective decisions can be effectively

reached if at least two people perfectly agree on at least one issue. The fact that the col-

lective ownership of 7 billion is practically impossible does not prove the practical

impossibility, and a fortiori the inconceivability, of collective ownership on a smaller

scale. Moreover, the third part of the argument (which considers that explicit and

unanimous consent for every single action is the only way of taking decisions in a com-

munity) is fallacious. Specific rules may greatly facilitate such decision-making without

lessening the ‘collective features’. For instance, the members of a community may unan-

imously vote to limit the ‘unanimity rule’ for certain important decisions only or they

may use the liberum veto (that is, as long as nobody explicitly opposes a proposal, it

is recognized as having the support of the community).

Finally, it is important to note that the rather simplistic description of collective

ownership provided by Rothbard and Hoppe drives them to formulate a ‘straw-man argu-

ment’. In point of fact, there is no pre-eminent scholar asking for a universal collective

ownership of bodies. Even in relation to land, egalitarians reject the simple idea of full

joint ownership (Cohen, 1995: 93–4), and even ‘simple egalitarianism’, in opposition to

which Walzer (1984) proposes his theory of ‘complex egalitarianism’, does not match

this description. So even if Rothbard and Hoppe were correctly proving the

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

8 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

inconceivability of collective ownership, their demonstration would still not have any

importance because nobody upholds this argument. While focusing on a simplistic ver-

sion of collective ownership, they lose sight of some of its other variants which are

incompatible with the self-ownership axiom and currently defended by various egalitar-

ian scholars. In a nutshell, for the reasons indicated above, even if the collective owner-

ship of 7 billion people is practically impossible, collective ownership as such is neither

inconceivable nor practically impossible.

The second alternative

Rothbard (1998: 45–6) explains as follows why the second alternative is unacceptable:

Let us consider alternative (2); here, one person or group of persons, G, are entitled to own

not only themselves but also the remainder of society R. But, apart from many other prob-

lems and difficulties with this kind of system, we cannot here have a universal or natural-

law ethic for the human race. We can only have a partial and arbitrary ethic ... Indeed, the

ethic which states that Class G is entitled to rule over the Class R implies that the latter, R,

are subhuman beings who do not have a right to participate as full humans in the rights of

self-ownership enjoyed by G – but this of course violates the initial assumption that we are

carving out an ethic for human beings as such. And, as we saw above, any ethic where one

group is given full ownership of another violates the most elementary rule for any ethic: that

it apply to every man. No partial ethics are any better, though they may seem superficially

more plausible, than the theory of all-power-to-the-Hohenzollerns.

This argument can be split into two constituent parts: (1) ‘one has the right to own

someone else’ cannot be accepted as an ethical axiom because it is partial; (2) it is partial

because it is not applicable to every human being.

Let us start the analysis of this argument from its second part and disclose its implicit

presupposition: moral theory should be exclusively confined to human beings. Here,

Rothbard contents himself with attentively following Kant (1991: 237) on the idea that

‘man can have no duty to any beings other than men’. Under the cover of the Kantian

principle of universality, what Rothbard really disputes is that partial ownership would

set up a category of moral subjects narrower than the category of all human beings.

Indeed, libertarians are in profound disagreement with any attempt to introduce cate-

gories or classes of moral subjects within humankind, as for instance with Aristotle’s dis-

tinction in Politics (1998: 1254a 23–4) between human beings ‘marked out for

subjection’ and those ‘marked out for rule’. However, the mere declaration that all, and

only, human beings are self-owners remains highly unsatisfactory. This idea highlights

the first limit of Rothbard’s argument. Further arguments are required to bolster it and to

demonstrate that to argue otherwise would be inconceivable.

Moreover, the very concept of a human being is patently fuzzy and subject to various

interpretations. Although Rothbard does not offer further detail on how exactly human

beings are to be defined, Hoppe (2006: 385), who is definitely aware of the importance

of this matter, insists that the self-ownership axiom applies only to those beings capable

of engaging in argumentation. This definition of human beings is manifestly very

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 9

restrictive. It excludes from humankind unborn foetuses, babies, children up to a certain

age, mentally impaired people, and individuals in a vegetative state. Leaving aside

the specific debate regarding this particular definition (Callahan and Murphy, 2006:

57–60; Eabrasu, 2009: 9–11), we must bear in mind that it distinguishes between human

beings who are capable of argumentation and those who are not. Following Rothbard’s

own rationale, Hoppe’s formulation of the self-ownership axiom would thereby be par-

tial (that is, non-universal) since it would exclude the aforementioned categories of

human beings. In addition, any formulation of the self-ownership axiom may appear

to be partial from the point of view of a theory which adopts a broader concept of a moral

person. For instance, Korsgaard (2004: 104–5) argues that it is ‘our animal nature, not

just our autonomous nature, that we take to be an end-in-itself’ and thereby concludes

that there is no reason to exclude animals from the category of moral subjects. From this

standpoint, both Rothbard’s self-ownership axiom (restricted to human beings) and a

fortiori Hoppe’s self-ownership axiom (applied solely to human beings capable of argu-

mentation) are partial. This is the second limit of Rothbard’s argument.

Partiality is not sufficient reason for dismissing the norm ‘one has the right to own

someone else’. This is because any formulation of the self-ownership axiom is poten-

tially partial and the universality of the self-ownership axiom depends on the way we

define the moral subject. Let us now suppose, for the sake of argument, that the norm

‘one has the right to own someone else’ is not universal, whereas the norm ‘everyone

has the right to own themselves’ is. One must ask why a statement should have to be

universally applicable to human beings in order to be considered an axiom. Rothbard

leaves this question unanswered and he simply assumes that universality is a prerequisite

for an axiom. The third limit of Rothbard’s argument is that this assumption is far from

obvious and needs amplification.

This assumption is not only questionable, it is also unclear. A closer look at the

second part of the argument indicates that Rothbard might be confusing two different

meanings of the word ‘partial’: incomplete (as opposed to universal) and discrimina-

tory (as opposed to impartial). To be sure, contrary to what Rothbard seems to suppose,

a discriminatory norm is not necessarily incomplete. If human beings are divided, as

Rothbard invites us to suppose, into class R and class G, a norm such as ‘class G is

entitled to rule over class R’, although discriminatory, applies nonetheless to all human

beings (be they members of class R or class G). However, let us skip this confusion and

suppose that Rothbard dismisses this norm because he considers it discriminatory.

Following this supposition, it is possible to emphasize a fourth limit of his argumenta-

tion: discrimination does not entail absurdity, as it is not conceptually impossible. It is

important to remember that Rothbard uses a reductio ad absurdum argument and his

objective is to prove the inconceivability of the norm ‘one has the right to own some-

one else’. In turn, what Rothbard’s argumentation shows is that this norm is unaccep-

table because it is discriminatory. At the outset we may note that Rothbard simply takes

for granted a strong normative assumption: discrimination is immoral. However, this

statement still does not prove the inconceivability of the aforementioned discrimina-

tory norm. At its very best, the argument states that given its intrinsic immorality, a

discriminatory norm is not a desirable candidate for an ethical axiom, but it does not

prove that it is absurd.

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

10 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

Furthermore, this observation leads us to the fifth, final, and most important limit of

Rothbard’s argument: petitio principii. Let us remember again that Rothbard’s chief aim

is to demonstrate that such a discriminatory norm is absurd. However, instead of showing

the absurdity of a discriminatory norm, Rothbard switches the argument and simply

declares that an ethical axiom must not discriminate. Such arguments are said to ‘beg

the question’. Rothbard’s argument fails as a proof because it will only be judged to

be sound by those who already accept its conclusion. For each of these five reasons, it

is now possible to conclude that Rothbard’s argument fails to prove the absurdity of

partial ownership.

To sum up this argument, both alternatives to self-ownership (collective and partial

ownership) are neither inconceivable nor practically impossible. Hence, the libertarian

monist claim stating that only the self-ownership axiom can be justified must be rejected.

The justification of the homesteading axiom by reductio ad

absurdum

This critique of the justification of libertarianism would remain incomplete if we were to

limit the discussion to the self-ownership axiom. Libertarian scholars in the tradition ini-

tiated by Rothbard (1996: 33) extend the self-ownership axiom to external resources: ‘if

every man owns his own person and therefore his own labour, and if by extension he

owns whatever property he has ‘‘created’’ or gathered out of the previously unused,

unowned, ‘‘state of nature’’, then what of the last great question: the right to own or

control the earth itself [?]’. To answer this question, Rothbard follows closely the Lock-

ean formulation of the homesteading principle: ‘whatsoever, then, he removes out of the

state that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and joined

to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property’ (Locke, 1980: V, §27).

Rothbard believes that ‘the natural rights justification for the ownership of ground land is

the same as the justification for the original ownership of all other property’ (1996: 34,

emphasis added). This idea is disputed by contemporary left-libertarians (Otsuka, 2003),

who point to the fact that the right to self-ownership does not necessarily equate to the

homesteading principle. Therefore, additional arguments have to be formulated in

defence of the homesteading principle.

Why should those who first have access to and de facto control of an external resource

also be its legitimate owners? Hoppe (2006: 336) uses reductio ad absurdum to demon-

strate that it could not possibly be otherwise. In doing so, he pays attention to the fact that

the alternatives to the homesteading axiom must be different from the alternatives to the

self-ownership axiom. Even though the argumentative structure remains the same, the

justification of the homesteading principle is different from the justification of

the self-ownership axiom and must be studied separately. Homesteading requires on the

one hand, that the respective resource should not have been previously used, and on the

other hand, that labour should be mixed with it. If these are the conditions, the alterna-

tives become obvious. Indeed, by denying the right to homesteading, it follows that

either a property right may be obtained by declaration or latecomers may be entitled

to ownership of such land without the initial agreement of a homesteader. If these

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 11

alternatives were inconceivable, then the axiom of homesteading would be justified.

Each alternative will now be detailed and discussed separately.

First, land may be appropriated by declaration:

If a person did not acquire the right of exclusive control over other, nature-given goods by

his own work, that is, if other people, who had not previously used such goods, had the right

to dispute the homesteader’s ownership claim, then this would only be possible if one would

acquire property titles not through labor, i.e., by establishing some objective link between a

particular person and a particular scarce resource, but simply by means of verbal declara-

tion. This solution ... would not even qualify as a solution in a purely technical sense in that

it would not provide a basis for deciding between rivalling declarative claims. (Hoppe,

2006: 336)

Indeed, declaration as a principle for land appropriation seriously complicates the assign-

ment of property rights. Since almost everyone can claim the same piece of land, additional

criteria would be required to deal with any ensuing conflicts between incompatible claims.

However, even if we agree with Hoppe that declaration is an insufficient principle for legit-

imizing the ownership of land, this still does not make this alternative absurd. As with our

discussion of the rejection of the first alternative to the self-ownership axiom, we can note

again the same category mistake: the confusion between practical and logical impossibility.

Let us now focus on the second alternative: the possibility that latecomers may

become owners.

If a person were not permitted to acquire property in these goods and spaces by means of an

act of original appropriation, i.e., by establishing an objective (inter-subjectively ascertain-

able) link between himself and a particular good and/or space prior to anyone else, but if,

instead, property in such goods or spaces were granted to late-comers, then no one would be

permitted to ever begin using any good unless he had previously secured such comers’

consent. Yet how can a late-comer consent to the actions of an early-comer? Moreover,

every late-comer would in turn need the consent of other still later-comers, and so on. That

is, neither we, nor our forefathers or our progeny would have been or will be able to survive

if one were to follow this rule. However, in order for any person – past, present, or future –

to argue anything it must be obviously possible to survive then and now; and in order to do

just this property rights cannot be conceived of as being timeless and unspecific with respect

to the number of persons concerned. (Hoppe, 2006: 383)

In formulating this argument, Hoppe closely follows Locke (1980: V, §28). Before

going any further, it is important to observe that the Lockean appropriation theory itself

has numerous interpretations. This theory is simultaneously used in various (and incom-

patible) theories of justice ranging from natural to contingent property rights and from

egalitarian to communitarian property rights (Widerquist, 2010: 5).

In addition to the multiple interpretations of the Lockean homesteading principle, we

can observe that this is not the only way of assigning property rights. Imagine a society in

which ownership is conceded only to old people. Instead of the homesteading axiom, this

society would function according to an alternative norm: ‘only people older than 65

years have the right to ownership’. This means that first comers under 65 may only

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

12 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

‘borrow’ a resource (so they will not perish) until they turn 65 or until another person

over 65 requests it. Although different than the axiom of homesteading, the rule of ‘over

65’ is neither inconceivable nor practically impossible. Not only is the application of this

rule possible, in some specific cases it is even intuitive: it is easy to observe, for example,

how some categories of people (older people and pregnant women) are entitled to prior-

ity seating on public transport.

This norm, proposed as a counter-example to the homesteading axiom, is based on a

prima facie rule (Ross, 1930: 19). This principle says that a norm is binding, ceteris

paribus, unless it is overridden by another norm. More precisely, the homesteading

axiom can be trumped by a norm saying that latecomers may be the just owners of a good

if they satisfy some specific conditions. The conditions may be, for instance, that they are

more than 65 years old, that they are poorer, taller, or stronger than the current user, and

so on. It is crucial to note that this alternative to homesteading does not postpone ad infi-

nitum the appropriation of a particular item. Hence, Hoppe’s argument falls short. Any

pioneer being the first to discover a good may use it until another person satisfying some

particular conditions requests its ownership. This idea makes clear that the order of

arrival is not the unique manner of granting the right of ownership. For example, eye

colour, strength, poverty, or similar could be possible criteria for allocating property

rights. Therefore, the rule of first appropriation should also be tested against such alter-

native norms and not only against the rule of second appropriation.

Furthermore, even if it is checked against the rule of second appropriation there are

not sufficient reasons to claim that only the homesteading axiom can be justified. Con-

sider, for example, a chair and a finite list of users at precise and different moments in

time: A, B, C, and D. Assume also that only one of these users can be the rightful owner.

Why should this be A rather than B, C, or D? The answer ‘because A is the first user’ is

neither more nor less obvious than the answer ‘because B is the second user’. The appli-

cation of the norm ‘for any defined item, its second user has the right to own it’, although

curious, is not logically or practically impossible. In practice, it could appear that this

norm would represent a disincentive for people to mix their labour with unoccupied land,

but this would be a utilitarian objection based on individual psychology rather than a

logical assumption. This norm is applicable to exactly the same extent as the homestead-

ing axiom. Yet, these two norms are mutually incompatible and, therefore, they cannot

have a simultaneous application.

For all these reasons, the reductio ad absurdum argument is not sufficient to justify the

homesteading axiom, whether the homesteading axiom is deduced from the self-ownership

axiom or not. Even when the reductio ad absurdum argument is customized to justify the

homesteading axiom, the absurdity of the alternatives to this axiom still cannot be proved.

Hence, additional arguments are required to bolster the monist claim that only libertarian-

ism can be justified. This is precisely the task of the performative contradiction argument.

The justification of the self-ownership axiom by performative

contradiction

While performative contradiction plays only a secondary role within the Rothbardian

argumentative strategy (Rothbard, 1998: 32–3), it becomes central for Hoppe (2006:

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 13

342). In formulating the performative contradiction argument, Hoppe derives his inspira-

tion from Habermas’s critique of post-structuralist thought (1993), which rephrases a

long-standing argumentative structure from Aristotle’s Metaphysics (1993: Book G,

1006a 11–28). A performative contradiction occurs when an agent denies what makes

this denial possible. For instance, it is a performative contradiction to say ‘there are

no statements’ because a statement is required to say it. Mutatis mutandis, Hoppe pur-

ports that it is absurd to deny the right to self-ownership since one must have the right

to own oneself in order to deny it.

Unlike reductio ad absurdum (which enumerates the alternatives to the self-

ownership axiom and assesses their absurdity), the performative contradiction tests the

logical consistency of the respective axiom. The logic of argumentation generally con-

siders the former argument as an indirect proof (the alternatives are absurd because they

are inconceivable), while it regards the latter as a direct proof of logical soundness (deny-

ing self-ownership is absurd). Although both arguments share the same conceptual

framework (absurdity), they make a different use of it. The reductio ad absurdum

argument strives to show that the alternatives to the libertarian axioms are logically

inconceivable (like a square circle). The performative contradiction argument exclu-

sively focuses on the self-contradiction between presupposing and denying the right to

self-ownership.

Here is how Hoppe (2006: 342) formulates the performative contradiction argument:

It must be considered the ultimate defeat for an ethical proposal if one can demonstrate that

its content is logically incompatible with the proponent’s claim that its validity be ascertain-

able by argumentative means. To demonstrate any such incompatibility would amount to an

impossibility proof; and such proof would constitute the most deadly smash possible in the

realm of intellectual inquiry ... Such property right in one’s own body must be said to be

justified a priori. For anyone who would try to justify any norm whatsoever would already

have to presuppose an exclusive right to control over his body as a valid norm simply in

order to say ‘I propose such and such’. And anyone disputing such right, then, would

become caught up in a practical contradiction, since arguing so would already implicitly

have to accept the very norm which he was disputing.

In order to put this argument in its context, we must unpick its two main implicit

premises. First, in order to solve conflicts, a solution is always required. Performative

contradiction proposes to justify the set of solutions grounded on the self-ownership

axiom. Second, when choosing a solution one cannot ignore the principle of non-

contradiction. At this point, Hoppe’s performative contradiction argument maintains that

the self-ownership axiom is the only one of those under consideration that is sound.

At the outset, let us reformulate the second variant of the reductio ad absurdum

argument and put it in a self-referential form: ‘only I and someone else (but not all

human beings) have the right to self-ownership’. Although this statement denies the right

to self-ownership to some human beings, it can be endlessly repeated without falling into

a performative contradiction. It is neither more nor less self-contradictory than the self-

ownership axiom. Now, it is crucial to observe that the two norms (my aforementioned

statement and the self-ownership axiom) are incompatible. Since two incompatible

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

14 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

norms can be tested against the performative contradiction argument, the role that this

argument plays in ethics should be considered with more caution. Hoppe’s performative

contradiction argument fails to justify the axiom of self-ownership because there is

another norm (incompatible with the self-ownership axiom) which passes the same test.

Furthermore, performative contradiction is not a genuine contradiction and, therefore,

it does not entail logical absurdity. ‘A contradiction cancels itself and leaves nothing’

(Strawson, 1952: 2). Filling the blanks in ‘__ and not __’ with a sentence ‘A’ does not

produce another sentence. Yet performative contradiction is not a genuine contradiction

of this type. While it is contradictory ‘to speak and not to speak’, it is not contradictory

(and hence, it is not absurd) to say loudly ‘I don’t speak.’ To be sure, the simple negation

of a proposition is not sufficient to establish a contradiction. Supposing and not suppos-

ing the self-ownership axiom is a formal contradiction that entails absurdity. As a matter

of fact, it is inconceivable to encounter both situations simultaneously. Mutatis mutandis,

saying ‘I deny and I do not deny the self-ownership axiom’ is a formal contradiction that

entails absurdity. But refuting the right to self-ownership is neither contradictory nor

absurd. If I deny the fact that I am writing now, my assertion may be a lie, hypocritical,

insincere, or dishonest, but it is definitely not absurd.

We should remember that the principle of non-contradiction in Aristotle’s formula-

tion in Metaphysics (1993: Book G, 1005b 20) mentions that two propositions are contra-

dictory if one proposition denies the other at the same time and in the same respect.

Performative contradiction disregards the latter condition because its constituent parts

are not in the same respect: one of the members of the performative contradiction is a

necessary condition for the other. This shows very clearly the flaws of Hoppe’s demon-

stration that only libertarianism can be defended through argumentation. Hoppe draws

the following conditional: if I deny the right to self-ownership, I must have the right

to own myself. He then concludes that it must be absurd to deny the right to self-

ownership, because such a right is the necessary condition for denying it. Hoppe’s

conclusion is unfounded because the parts of a conditional cannot be in contradiction,

since they are not in the same respect. Hence, there is no logical absurdity in denying the

right to self-ownership.

Moreover, not only does performative contradiction not lead to absurdity, but it may

denote an astute strategy (Mackie, 1964). For instance, individuals may take advantage

of the right to free speech in order to demand its abolition (Chevigny, 1980). The

Libertarian Party in the USA strives to abolish the state by using the democratic electoral

system (Rothbard, 1996: 307). Such performative contradictions are usually interpreted

as strategies for reaching a definite goal, and they are acceptable even though the means

and the ends diverge. Hoppe (1999) certainly does not feel uncomfortable making the

case for private defence while benefiting from the protection of the state. Ceteris

paribus, he should also accept that one can use the right to self-ownership to deny this

axiom. It is neither inconceivable nor practically impossible and not even incoherent that

a group of self-owners may unanimously and voluntary agree upon a theory of justice

grounded on other principles than self-ownership and homesteading in order to solve

eventual conflicts among them. Such societies illustrate the fact that the right to

self-ownership as a condition for establishing a theory of justice does not influence the

content of the respective theory of justice.

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 15

The performative contradiction argument, as it is formulated by Hoppe, conflates two

different interpretations of the right to self-ownership: self-ownership-as-norm and self-

ownership-as-condition. On the one hand, the right to self-ownership is the fundamental

norm of a theory of justice. From this point of view, only consensual actions are just.

This approach applies on a case-by-case basis. For instance, the prohibition of prostitu-

tion would violate the right to self-ownership. On other hand, the right to self-ownership

is a necessary condition for establishing a norm. This approach exclusively refers to the

circumstances of a norm and leaves aside each particular case. From this standpoint, a

norm is morally acceptable only if the people enjoying the right to self-ownership con-

sider it as such. However, in this case there is no requirement whatsoever as to the con-

tent of the respective norm. For instance, self-owners may agree to prohibit actions (such

as prostitution) even though they are mutually consented to. Also, such self-owners may

agree to establish coercive taxation and to redistribute the available goods among

themselves.

Hoppe’s performative contradiction argument focuses on the self-ownership-as-norm

interpretation and maintains that it would be absurd to deny it because this would contra-

dict self-ownership-as-condition. It now appears clear why there is no absurdity involved

in this denial. This is precisely because these two dimensions of the right to self-

ownership are entirely separate. Stipulating that the right to self-ownership is a necessary

condition for formulating a norm does not say what the content of the respective norm

should be, and does not necessarily imply that the content of the respective norm must be

compatible with the right to self-ownership. To sum up, the performative contradiction

argument does not provide compelling reasons to sustain the proposition that only the

self-ownership axiom can be a premise for a theory of justice. Thus far, libertarianism

does not appear to be sounder than any other theory of justice.

Conclusion

This article has revealed the flaws of the two arguments (reductio ad absurdum and

performative contradiction) designed by Rothbard and Hoppe with a view to validating

the libertarian monist claim stating that only the theory of justice deduced from the self-

ownership and homesteading axioms can be justified. Obviously, the argument of this

article cannot prevent upgraded or additional arguments which may uphold the libertar-

ian claim on different grounds. Despite this limit, the current argumentation can contrib-

ute to fine-tuning the libertarian monist claim. As indicated in the introduction, it should

now be possible to reconsider the libertarian theory of political obligation and to relocate

libertarianism in the moral and political landscape. Let us now conclude by assessing

these implications, and thereby formulating avenues for future research.

The study of the reductio ad absurdum argument unveiled noteworthy difficulties in

proving that the alternatives to the self-ownership and homesteading rights are absurd

(inconceivable or contradictory). Not only are many of these alternatives conceivable,

but they also seem feasible, some of them having actually been concretely adopted in

the history of mankind. The alternatives to the homesteading axiom denote various pat-

terns of resource redistribution, legitimizing the ownership of people other than the first

occupant. As to the alternatives to the self-ownership axiom, they cover a wide range of

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

16 Politics, Philosophy & Economics

actions performed under coercion, from slavery and apartheid to conscription and

taxation. Moreover, the discussion of the performative contradiction argument showed

that the alternatives to the self-ownership axiom do not necessarily infringe it. A coer-

cive action indeed violates the right to self-ownership interpreted as the basic axiom

of a theory of justice. Therefore, within this perspective, a coercive action is always

morally unacceptable. Yet the coerced person could have consented (conditionally or

unconditionally) to the use of force against himself or herself. In this case, it appears that

the right to self-ownership is not infringed if it is interpreted as a necessary condition for

establishing a theory of justice. For instance, if taxation and slavery are consensual, then

they are perfectly compatible with the right to self-ownership as the condition for

establishing a theory of justice, although they necessarily infringe the right to self-

ownership interpreted as the basic axiom of a theory of justice.

The distinction between self-ownership-as-norm and self-ownership-as-condition

also opens new research perspectives regarding the theory of political obligation, as it

makes more complex the normative argument pertaining to the moral justification of the

state (Hasnas, 2003). With this distinction in hand, it will be possible to distinguish two

different grounds for declaring the state an unjust political arrangement, and

consequently two different libertarian streams. Within the first stream, the state is con-

sidered unjust because it is a form of coercive association established without the explicit

agreement of its members (that is, the state violates self-ownership-as-condition). Within

the second stream, the state is considered unjust because it prohibits many freely con-

senting relationships, such as drug consumption, prostitution, or weapon possession (that

is, it violates the self-ownership-as-norm). These two theories of political obligation

perfectly match the libertarian debate on the paradox of selling oneself into slavery,

exposed in Leviticus 25: 39. The advocates of the justness of this act refer to self-own-

ership-as-condition (Nozick, 1974). They consider that an agreement is just because it is

made by self-owners. Therefore, it must be just to sell oneself into slavery. The scholars

who dispute the justness of this act (Rothbard, 1998: 40–41) point to the fact that it

contradicts self-ownership-as-norm (that is, the fundamental norm of the theory of jus-

tice that they endorse). Additional research in this direction can establish more specifi-

cally the complex relationship between various patterns of resource redistribution,

coercion (Arneson, 2003), and self-ownership (Mack, 2002a, 2002b).

Moreover, the distinction between these two approaches to self-ownership sheds new

light on the disagreements between the three main libertarian lines of thought: libertarian

socialism, right-libertarianism, and left-libertarianism (Widerquist, 2008). For instance,

it should now be possible to show that when the right to self-ownership is interpreted as a

condition for establishing a theory of justice, these disagreements are less fundamental

than is usually supposed. This interpretation of self-ownership explains how left-

libertarians (Vallentyne, 2007) and right-libertarians (Kukathas, 2009) may agree upon

the circumstances of a theory of justice and may admit that coercive redistribution of

resources does not necessarily infringe the right to self-ownership (Vallentyne and

Steiner, 2004). Within this perspective, the debate between left- and right-

libertarianism is confined to a mere disagreement on the pattern of resource redistribu-

tion. All the possible theories of justice resulting from a mutually consented agreement

are thereby reciprocally compatible. Based on this observation, it is now possible to

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

Eabrasu 17

conclude that upholding the right to self-ownership-as-condition does not necessarily

oppose the theory of political obligation or left-libertarianism. Further research in this

direction can contribute to understanding whether self-ownership-as-condition can

support a more than minimal state (Widerquist, 2009) and to reassessing the internal

coherence of various libertarian streams (Risse, 2004).

To sum up, the libertarian theory of justice cannot be discarded just because of a

simple disagreement with its consequences, and its critiquing must be pursued with

caution. The above-mentioned difference between the two interpretations of the right

to self-ownership suggests that it is not necessary to throw the baby out with the bath-

water. The rejection of the libertarian theory of justice deduced from the axiom of

self-ownership does not discard ipso facto the right to self-ownership as a necessary con-

dition for a theory of justice.

References

Aristotle (1993) Metaphysics. Kirwan C (trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aristotle (1998) Politics. Barker E (trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arneson RJ (2003) Equality, coercion, culture and social norms. Politics, Philosophy and Econom-

ics 2(2): 139–63.

Attas D (2005) Liberty, Property and Markets: A Critique of Libertarianism. Aldershot: Ashgate

Publishing.

Barry N (1989) Libertarianism. In: Hunt GMK (ed.) Philosophy and Politics: Supplement to

Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.109–29.

Barry N (1995) Rothbard: Liberty, economy, and state. Journal des Economistes et des Etudes

Humaines (6)1: 105–19.

Block W (1996) Review of ‘The Economics and Ethics of Private Property’. Journal des Econo-

mistes et des Etudes Humaines 7(1): 161–5.

Block W (ed.) (2010) I Chose Liberty: Autobiographies of Contemporary Libertarians. Auburn,

AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Block W (2011) Rejoinder to Murphy and Callahan on Hoppe’s argumentation ethics. Journal of

Libertarian Studies 22(1): 631–9.

Callahan G (2012) Liberty versus libertarianism. Politics, Philosophy and Economics. Epub ahead

of print 5 February 2012. DOI: 10.1177/1470594X11433739.

Callahan G and Murphy R (2006) Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s argumentation ethics: A critique.

Journal of Libertarian Studies 20(2): 53–64.

Casey G (2009) Feser on Rothbard as a philosopher. Libertarian Papers 1(34): 1–13.

Chevigny PG (1980) Philosophy of language and free expression. New York University Law

Review 55: 157–94.

Cohen GA (1995) Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Eabrasu M (2009) A reply to the current critiques formulated against Hoppe’s argumentation

ethics. Libertarian Papers 1(20): 1–29.

Foster WT (2007) Argumentation and Debating. Cambridge, MA: Read Books.

Friedman D (1988) The trouble with Hoppe. Liberty, November.

Friedman J (1992) After libertarianism: Rejoinder to Narveson, MacCloskey, Flew, and Machan.

Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society (6)1: 113–52.

Downloaded from ppe.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on June 5, 2013

18 Politics, Philosophy & Economics