Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Luvian SIG Surita Balls of Yarn

Luvian SIG Surita Balls of Yarn

Uploaded by

Mar AlexCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Abusir and SaqqaraDocument159 pagesAbusir and SaqqaraReham100% (1)

- Archaic Greece New Approaches and New EvidenceDocument479 pagesArchaic Greece New Approaches and New EvidencePaulo E. Galdini100% (9)

- Akkade Is King A Collection of Papers byDocument346 pagesAkkade Is King A Collection of Papers byLuana Teixeira Barros LuaNo ratings yet

- Minni and MuninnDocument254 pagesMinni and MuninnXiomara Velázquez LandaNo ratings yet

- Tracing the Indo-Europeans: New evidence from archaeology and historical linguisticsFrom EverandTracing the Indo-Europeans: New evidence from archaeology and historical linguisticsBirgit Anette OlsenNo ratings yet

- Swords, Crowns, Censers and Books: Francia Media - Cradles of European CultureDocument56 pagesSwords, Crowns, Censers and Books: Francia Media - Cradles of European CultureAnte Vukic100% (1)

- (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 48) Anna Giacalone Ramat, Onofrio Carruba, Giuliano Bernini (Eds.)-Papers From the 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics-John Benjamins PublishingDocument689 pages(Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 48) Anna Giacalone Ramat, Onofrio Carruba, Giuliano Bernini (Eds.)-Papers From the 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics-John Benjamins Publishingjgaviramarcos100% (1)

- Sargent TechniqueDocument16 pagesSargent TechniqueTia Ram100% (2)

- Info 1Document28 pagesInfo 1Veejay Soriano Cuevas0% (1)

- Robot Project Report RoboticsDocument34 pagesRobot Project Report Roboticsdcrust_amit82% (11)

- Full Ebook of Usque Ad Radices Indo European Studies in Honour of Birgit Anette Olsen Bjarne Simmelkjaer Editor Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of Usque Ad Radices Indo European Studies in Honour of Birgit Anette Olsen Bjarne Simmelkjaer Editor Online PDF All Chaptermarsithsairi100% (10)

- (Ritus Et Artes, 7) Wojtek Jezierski, Lars Hermanson, Hans Jacob Orning, Thomas Småberg - Rituals, Performatives, and Political Order in Northern Europe, C. 650-1350-Brepols (2015)Document382 pages(Ritus Et Artes, 7) Wojtek Jezierski, Lars Hermanson, Hans Jacob Orning, Thomas Småberg - Rituals, Performatives, and Political Order in Northern Europe, C. 650-1350-Brepols (2015)BernardoyDiomiraNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of ThingsDocument166 pagesMaking Sense of ThingsBoppo Grimmsma100% (1)

- The Earliest Indo-Europeans in AnatoliaDocument15 pagesThe Earliest Indo-Europeans in Anatoliaruja_popova1178100% (1)

- Religion, Myth, and Folklore in The World's EpicsDocument601 pagesReligion, Myth, and Folklore in The World's EpicsDorinda100% (5)

- 214 200 1 PBDocument14 pages214 200 1 PBJéssica IglésiasNo ratings yet

- Contacts and Networks in The Baltic Sea Region: Austmarr As A Northern Mare Nostrum, Ca. 500-1500 AdDocument298 pagesContacts and Networks in The Baltic Sea Region: Austmarr As A Northern Mare Nostrum, Ca. 500-1500 AdAlexander SoltészNo ratings yet

- The Indo-European Puzzle RevisitedDocument358 pagesThe Indo-European Puzzle RevisitedfelipeNo ratings yet

- Zbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta I PDFDocument446 pagesZbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta I PDFEdita Vučić100% (1)

- Koerner e Andersen 1987 - Historical Linguistics 1987 Papers From The 8th International Conference On Historical Linguistics, Lille, August 31-September...Document589 pagesKoerner e Andersen 1987 - Historical Linguistics 1987 Papers From The 8th International Conference On Historical Linguistics, Lille, August 31-September...Gláucia Aguiar100% (1)

- Es Pak PeeterDocument157 pagesEs Pak PeeterNicole SigaudNo ratings yet

- Attilas Europe Structural TransformationDocument15 pagesAttilas Europe Structural TransformationБългарско Бранно УмениеNo ratings yet

- Rules and Misrules Hide Beamer VariabiliDocument19 pagesRules and Misrules Hide Beamer Variabilizsuzsanna.toth11No ratings yet

- Early Contacts Between Uralic and Indo European Linguistic and ArchaeologicalDocument456 pagesEarly Contacts Between Uralic and Indo European Linguistic and ArchaeologicalJoel ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Samoyedic Shamanic Drums Some Symbolic InterpretationDocument22 pagesSamoyedic Shamanic Drums Some Symbolic InterpretationGerard Canals PuigvendrelloNo ratings yet

- The Temples of Anahid at Estakhr SoutherDocument23 pagesThe Temples of Anahid at Estakhr SoutherRay DocNo ratings yet

- Ilok Ottoman MosqueDocument33 pagesIlok Ottoman MosqueAndrea RimpfNo ratings yet

- Anatoliaantiqua 303 PDFDocument11 pagesAnatoliaantiqua 303 PDFschauerNo ratings yet

- Aeolian Scripts 2014 - Studies in Honour of Viola T. Dobosi, Inventaria Praehistorica Hungariae 13, 2014Document344 pagesAeolian Scripts 2014 - Studies in Honour of Viola T. Dobosi, Inventaria Praehistorica Hungariae 13, 2014Paolo BiagiNo ratings yet

- Sacralization of Landscape and Sacred Places: Zbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta Instituti Archaeologici KnjigaDocument21 pagesSacralization of Landscape and Sacred Places: Zbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta Instituti Archaeologici KnjigaTareNo ratings yet

- Scodel Ruth - Defining Greek NarrativeDocument393 pagesScodel Ruth - Defining Greek Narrativeernesto borges100% (2)

- Artumes in Etruria-LibreDocument47 pagesArtumes in Etruria-LibreВерка ПавловићNo ratings yet

- Sec 19 12Document10 pagesSec 19 12Visual AdditionNo ratings yet

- "Scripta Islandica" / "ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK", Vol. 65, 2014Document248 pages"Scripta Islandica" / "ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK", Vol. 65, 2014Before AfterNo ratings yet

- An Onvestigation Into The Origins of Domestic Sheep in The Southern Levant - ICAZ 1998 - Horwitz & DucosDocument19 pagesAn Onvestigation Into The Origins of Domestic Sheep in The Southern Levant - ICAZ 1998 - Horwitz & Ducosgjs77496No ratings yet

- From Late Bronze To Early Iron Age ThracDocument23 pagesFrom Late Bronze To Early Iron Age ThracVolkan KaytmazNo ratings yet

- Le Statut Juridique Des Cites Grecques PDFDocument25 pagesLe Statut Juridique Des Cites Grecques PDFAna Honcu0% (1)

- JRA 28 2015 56 Scherrer KouretesinEphesosDocument17 pagesJRA 28 2015 56 Scherrer KouretesinEphesosvladan stojiljkovicNo ratings yet

- 1Document19 pages1KonradNo ratings yet

- Ενότητα Γ - 5.EleusinianMysteries BremmerDocument27 pagesΕνότητα Γ - 5.EleusinianMysteries BremmerNick Psillakis100% (1)

- Attila'S Europe?: Structural Transformation and Strategies of Success in The European Hun PeriodDocument29 pagesAttila'S Europe?: Structural Transformation and Strategies of Success in The European Hun PeriodKiss AttilaNo ratings yet

- Epidaurus (Teatro)Document3 pagesEpidaurus (Teatro)VGVNo ratings yet

- A. Chaniotis, Unveiling Emotions (2012)Document465 pagesA. Chaniotis, Unveiling Emotions (2012)Adrian Drișcu100% (2)

- Homer's OgygiaDocument22 pagesHomer's OgygiaAbbey GrechNo ratings yet

- 0446 PDFDocument224 pages0446 PDFtyrue100% (2)

- Leszek Gardela Bad Death Final PreprintDocument4 pagesLeszek Gardela Bad Death Final PreprintHeather FreysdottirNo ratings yet

- (Intersections Volume 50) Enenkel, Karl A. E. - Smith, Paul J - Emblems and The Natural World (2017)Document701 pages(Intersections Volume 50) Enenkel, Karl A. E. - Smith, Paul J - Emblems and The Natural World (2017)analauraiNo ratings yet

- Spirit Possession: Multidisciplinary Approaches to a Worldwide PhenomenonFrom EverandSpirit Possession: Multidisciplinary Approaches to a Worldwide PhenomenonNo ratings yet

- What's in A NameDocument9 pagesWhat's in A NamehoweNo ratings yet

- Papers On Ancient Greek Linguistics - Finnish Society (2018)Document595 pagesPapers On Ancient Greek Linguistics - Finnish Society (2018)mariomb36No ratings yet

- Mystery of Runes and Turkic InscriptionsDocument16 pagesMystery of Runes and Turkic Inscriptionsyelbuke50% (2)

- Res, Artes et Religio: Essays in Honour of Rudolf SimekFrom EverandRes, Artes et Religio: Essays in Honour of Rudolf SimekSabine Heidi WaltherNo ratings yet

- Folklore in Old Norse - Old Norse in Folklore - Daniel Sävborg, Karen Bek-Pedersen - Nordistica Tartuensia, 20, 2014 - University of Tartu Press - 9789949327041 - Anna's ArcDocument190 pagesFolklore in Old Norse - Old Norse in Folklore - Daniel Sävborg, Karen Bek-Pedersen - Nordistica Tartuensia, 20, 2014 - University of Tartu Press - 9789949327041 - Anna's ArcCammyla SaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Czekaj-Zastawny Kabaciski Terberger-LongdistanceexchangeDocument20 pages2014 Czekaj-Zastawny Kabaciski Terberger-LongdistanceexchangeChu Dinh TuanNo ratings yet

- 4b2ac53a3ea2a005ddd7117a8a39eca4Document411 pages4b2ac53a3ea2a005ddd7117a8a39eca4YotaNo ratings yet

- Marazzi - FS Poettol PDFDocument30 pagesMarazzi - FS Poettol PDFmasmarazziNo ratings yet

- Myth & Symbol IDocument332 pagesMyth & Symbol Ismaragda2007100% (3)

- Lands of the Shamans: Archaeology, Landscape and CosmologyFrom EverandLands of the Shamans: Archaeology, Landscape and CosmologyDragos GheorghiuNo ratings yet

- From Dust To Dawn: Uppsala Rhetorical StudiesDocument28 pagesFrom Dust To Dawn: Uppsala Rhetorical StudiesIntegrante TreceNo ratings yet

- Textbook Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects From Central Greece To The Black Sea Georgios Giannakis Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects From Central Greece To The Black Sea Georgios Giannakis Ebook All Chapter PDFterrence.mcgee263100% (5)

- The Temple The Tree and The Well. in Old PDFDocument50 pagesThe Temple The Tree and The Well. in Old PDFJake McIvryNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Mythology PDFDocument43 pagesThe Origins of Mythology PDFТомислав Галавић100% (1)

- Archaeological Institute of AmericaDocument4 pagesArchaeological Institute of AmericaNéféret MéréretNo ratings yet

- Bcu Iasi / Central University Library: Some RomanianDocument4 pagesBcu Iasi / Central University Library: Some RomanianMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Time To Gather Stones Together GreekDocument18 pagesTime To Gather Stones Together GreekMar AlexNo ratings yet

- ThePlaceNamesofFifeandKinross 10294386Document73 pagesThePlaceNamesofFifeandKinross 10294386Mar AlexNo ratings yet

- Studies in Lycian and Carian Phonology ADocument30 pagesStudies in Lycian and Carian Phonology AMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Notes On Three Acrostatic Neuter S StemsDocument11 pagesNotes On Three Acrostatic Neuter S StemsMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Rigveda FullDocument597 pagesRigveda FullGhanesh RS67% (3)

- Revisiting Proto Indo European SchwebeabDocument174 pagesRevisiting Proto Indo European SchwebeabMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Hamp, Eric P., Some Notes On Istoria Limbii Romane by Al. Rosetti, SCL, An. 27, Nr. 2, 1976, P. 181-184Document4 pagesHamp, Eric P., Some Notes On Istoria Limbii Romane by Al. Rosetti, SCL, An. 27, Nr. 2, 1976, P. 181-184Mar AlexNo ratings yet

- Surface Gravity and Hawking Temperature From EntroDocument8 pagesSurface Gravity and Hawking Temperature From EntroMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Strange Ablauts and Neglected Sound ChanDocument23 pagesStrange Ablauts and Neglected Sound ChanMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Tocharian Special Agents The NT ParticipDocument18 pagesTocharian Special Agents The NT ParticipMar AlexNo ratings yet

- On The Origin of Grammatical GenderDocument6 pagesOn The Origin of Grammatical GenderMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Adrese TV 2016Document33 pagesAdrese TV 2016Mar AlexNo ratings yet

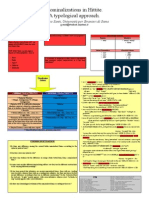

- Giacomo Santi, Università Per Stranieri Di Siena: Nominalizations in Hittite. A Typological ApproachDocument2 pagesGiacomo Santi, Università Per Stranieri Di Siena: Nominalizations in Hittite. A Typological ApproachMar AlexNo ratings yet

- The Language and Writing System of MS408 Voynich ExplainedDocument39 pagesThe Language and Writing System of MS408 Voynich ExplainedMar AlexNo ratings yet

- IRF5 Promotes Inflammatory Macrophage Polarization and T 1-T 17 ResponsesDocument9 pagesIRF5 Promotes Inflammatory Macrophage Polarization and T 1-T 17 ResponsesMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Hematopoietic Stem Cell: Self-Renewal Versus DifferentiationDocument14 pagesHematopoietic Stem Cell: Self-Renewal Versus DifferentiationMar AlexNo ratings yet

- An Algorithm For Pronominal Anaphora Resolution: Shalom Lappin" Herbert Leass TDocument28 pagesAn Algorithm For Pronominal Anaphora Resolution: Shalom Lappin" Herbert Leass TMar AlexNo ratings yet

- ZF5HP19FL VW+Audi+Porsche Gas North AmericaDocument63 pagesZF5HP19FL VW+Audi+Porsche Gas North Americadeliveryvalve100% (1)

- ObjectiveDocument22 pagesObjectiveKoratala HarshaNo ratings yet

- Computational Analysis of Centrifugal Compressor Surge Control Using Air InjectionDocument24 pagesComputational Analysis of Centrifugal Compressor Surge Control Using Air InjectionrafieeNo ratings yet

- Signals and Systems DE-40 EE - Semester 4 Spring 2020: Lab Report # 06Document21 pagesSignals and Systems DE-40 EE - Semester 4 Spring 2020: Lab Report # 06Muhammad YousafNo ratings yet

- Offset Flail Mowers: OFM3678, OFM3690 & OFM3698Document38 pagesOffset Flail Mowers: OFM3678, OFM3690 & OFM3698gomezcabellojosemanuelNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Design Document: GE401-Innovative Product Design & Development IDocument15 pagesPreliminary Design Document: GE401-Innovative Product Design & Development IvfoodNo ratings yet

- 4 WD SystemDocument126 pages4 WD SystemSantiago Morales100% (1)

- AV Control Receiver: Operating InstructionsDocument32 pagesAV Control Receiver: Operating InstructionsCuthbert Marshall100% (1)

- Dialysis: Prepared byDocument31 pagesDialysis: Prepared byVimal PatelNo ratings yet

- M.S. Al-Suwaidi Industrial Services, Co. Ltd. Hazard Identification PlanDocument6 pagesM.S. Al-Suwaidi Industrial Services, Co. Ltd. Hazard Identification PlanDarius DsouzaNo ratings yet

- Datasheet DiacDocument4 pagesDatasheet DiacOrlandoTobonNo ratings yet

- Company Analysis Report On M/s Vimal Oil & Foods LTDDocument32 pagesCompany Analysis Report On M/s Vimal Oil & Foods LTDbalaji bysani100% (1)

- Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis. Etiology, Anatomy, Pathogenesis, Classification, Clinical Picture, Diagnostics, Treatment and ComplicationsDocument36 pagesOdontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis. Etiology, Anatomy, Pathogenesis, Classification, Clinical Picture, Diagnostics, Treatment and ComplicationsАлександр ВолошанNo ratings yet

- University of Gondar Institute of Technology Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Project ProposalDocument32 pagesUniversity of Gondar Institute of Technology Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Project ProposalDasale DaposNo ratings yet

- Released FOR Manufacturing: 2509 ANTAMINA PERU SMC 100/14400 Truck Bridge Assembly Truck Bridge Steel Structure - RightDocument1 pageReleased FOR Manufacturing: 2509 ANTAMINA PERU SMC 100/14400 Truck Bridge Assembly Truck Bridge Steel Structure - RightCarlos ParedesNo ratings yet

- Playground Arduino CC Code NewPingDocument11 pagesPlayground Arduino CC Code NewPingimglobaltraders100% (1)

- 1974-5 Gibson Super 400CES PDFDocument6 pages1974-5 Gibson Super 400CES PDFBetoguitar777No ratings yet

- Silage Pile Sizing Documentation 5 12 2016 3Document9 pagesSilage Pile Sizing Documentation 5 12 2016 3Zaqueu Ferreira RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Horizontal Jaw RelationsDocument90 pagesHorizontal Jaw RelationsKeerthiga TamilarasanNo ratings yet

- MWR-SH11UN Installation+Manual DB68-08199A-01 ENGLISH 11092020Document20 pagesMWR-SH11UN Installation+Manual DB68-08199A-01 ENGLISH 11092020Jahir UddinNo ratings yet

- Skema Jawapan Instrumen Bi PTTS 2023Document9 pagesSkema Jawapan Instrumen Bi PTTS 2023Darina Chin AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Piping Info - Carbon Steel & Stainless Steel Guide SpacingDocument2 pagesPiping Info - Carbon Steel & Stainless Steel Guide SpacingpalluraviNo ratings yet

- Clinical Update: The Deficient Alveolar Ridge: Classification and Augmentation Considerations For Implant PlacementDocument2 pagesClinical Update: The Deficient Alveolar Ridge: Classification and Augmentation Considerations For Implant PlacementJordan BzNo ratings yet

- Apour Pressure For Liquid Vapour Equilibrium: Antoine'S Equation Fitting (T in Kelvin and P in Kpa)Document2 pagesApour Pressure For Liquid Vapour Equilibrium: Antoine'S Equation Fitting (T in Kelvin and P in Kpa)makari66No ratings yet

- Red Oxide Primer (ENG)Document3 pagesRed Oxide Primer (ENG)Evan BadakNo ratings yet

- Barang 3Document12 pagesBarang 3Sujoko SkinzNo ratings yet

- Lab1 - ArrayDocument6 pagesLab1 - Arrayezz AymanNo ratings yet

Luvian SIG Surita Balls of Yarn

Luvian SIG Surita Balls of Yarn

Uploaded by

Mar AlexCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Luvian SIG Surita Balls of Yarn

Luvian SIG Surita Balls of Yarn

Uploaded by

Mar AlexCopyright:

Available Formats

USQUE AD RADICES

Indo-European studies in honour of

Birgit Anette Olsen

Edited by

Bjarne Simmelkjær Sandgaard Hansen · Adam Hyllested

Anders Richardt Jørgensen · Guus Kroonen

Jenny Helena Larsson · Benedicte Nielsen Whitehead

Thomas Olander · Tobias Mosbæk Søborg

Museum Tusculanum Press

2017

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Usque ad Radices: Indo-European Studies in Honour of Birgit Anette Olsen

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the authors 2017

Edited by Bjarne Simmelkjær Sandgaard Hansen, Adam Hyllested, Anders

Richardt Jørgensen, Guus Kroonen, Jenny Helena Larsson, Benedicte

Nielsen Whitehead, Thomas Olander & Tobias Mosbæk Søborg

Cover design by ora Fisker

Printed in Denmark by Specialtrykkeriet Viborg

ISBN 978 87 635 4576 1

Copenhagen Studies in Indo-European, vol. 8

ISSN 1399 5308

Published with support from:

Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen

Museum Tusculanum Press

Dantes Plads 1

dk – 1556 Copenhagen V

www.mtp.dk

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Contents

Preface xiii

Henrik Vagn Aagesen

Electronic dictionary and word analysis combined: Some practical

aspects of Greenlandic, Finnish and Danish morphology 1

Douglas Q. Adams

Thorn-clusters in Tocharian 7

Miguel Ángel Andrés-Toledo

Vedic, Avestan and Greek sunrise: The dawn of an Indo-European

formula 15

David W. Anthony & Dorcas R. Brown

Molecular archaeology and Indo-European linguistics: Impressions

from new data 25

Lucien van Beek

Greek βλάπτω and further evidence for a Proto-Greek voicing rule

*-Ń̥ T- > *-Ń̥ D- 55

Lars Brink

Unknown origin 73

Antje Casaretto

Encoding non-spatial relations: Vedic local particles and the

conceptual transfer from space to time 87

James Clackson

Contamination and blending in Armenian etymology 99

Paul S. Cohen

PIE telic s-extensions and their diachronic implications 117

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

viii Contents

Varja Cvetko-Orešnik & Janez Orešnik

Natural syntax of the English imperative 135

Hannes A. Fellner

The Tocharian gerundives in B-lle A-l 149

José Luis García Ramón

Anthroponymica Mycenaea 10: The name e-ti-ra-wo /Erti-lāwos/ (and

Λᾱ‑έρτης): ἔρετο· ὡρμήθη (Hsch.), Hom. ὁρμήθησαν ἐπ’ ἀνδράσιν, and

Hom. ἔρχεσθαι μετὰ φῦλα θεῶν, Cret. MN Ἐρπετίδαμος 161

Jost Gippert

Armeno-Albanica II: Exchanging doves 179

Laura Grestenberger

On “i-substantivizations” in Vedic compounds 193

Bjarne Simmelkjær Sandgaard Hansen

Alleged nursery words and hypocorisms among Germanic kinship

terms 207

Jón Axel Harðarson

The prehistory and development of Old Norse verbs of the type

þrøngva / þręngia ‘to make narrow, press’ 221

Jan Heegård & Ida E. Mørch

Kalasha dialects and a glimpse into the history of the Kalasha language 233

Irén Hegedűs

The etymology of Prasun atˈəg ‘one; once, a (little)’ 249

Eugen Hill

Zur Flexion von ›sein‹ im Westgermanischen: Die verschollene

Entsprechung von altenglisch 3. Singular Präsens bið auf dem Festland 261

George Hinge

Verzweifelte Versuche: Zur Herkunft des pindarischen τόσσαι 279

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Contents ix

Adam Hyllested

Armenian gočazm ‘blue gemstone’ and the Iranian evil eye 293

Britta Irslinger

The ‘sewing needle’ in Western Europe: Archaeological and linguistic

data 307

Jay H. Jasanoff

The Old Irish f-future 325

James A. Johnson

Sign of the times? Spoked wheels, social change, and signification in

Proto-Indo-European materials and language 339

Folke Josephson

Theoretical and comparative approaches to the functions of Hittite local

particles: Interplay between local adverbs, local particles and verbs 351

Aigars Kalniņš

Hittite nt-numerals and the collective guise of an individualising suffix 361

Jared S. Klein

Two notes on Classical Armenian: 1. erkin(kc) ew erkir;

2. The 3rd pers. sg. (medio)passive imperfect in -iwr 377

Alwin Kloekhorst

The Hittite genitive ending -ā̆n 385

Petr Kocharov

The etymology of Armenian əntceṙnul ‘to read’ 401

Daniel Kölligan

Armenian lkti, lknim ‘(be) wild’ 415

Kristian Kristiansen

When language meets archaeology: From Proto-Indo-European to

Proto-Germanic in northern Europe 427

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

x Contents

Martin Joachim Kümmel

Even more traces of the accent in Armenian? The development of

tenues after sonorants 439

Sandra Lucas

Verbal complementation in Medieval Greek: A synthetic view of the

relationship between the dying infinitive and its finite substitute 453

Rosemarie Lühr

Verbakzent und Informationsstruktur im Altindischen 467

Robert Mailhammer

Subgrouping Indo-European: A fresh perspective 483

J. P. Mallory

Speculations on the Neolithic origins of the language families of

Southwest Asia 503

Hrach Martirosyan

Some Armenian female personal names 517

H. Craig Melchert

An allative case in Proto-Indo-European? 527

Hans Frede Nielsen

From William the Conqueror to James I: Language and identity

in England 1066–1625 541

Benedicte Nielsen Whitehead

Composition and derivation: A review of some elementary concepts 551

Alexander Nikolaev

Luvian (SÍG) šūrita ‘balls of yarn’ 567

Alan J. Nussbaum

The Latin “bonus rule” and benignus ‘generous, kind’ 575

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Contents xi

Norbert Oettinger

Gall. Cernunnos, lat. cornū ›Horn‹ und heth. Tarhunna-: Mit einer

Bemerkung zu gr. πᾶς ›ganz‹ 593

Thomas Olander

Drinking beer, smoking tobacco and reconstructing prehistory 605

Einar Østmo

Bronze Age heroes in rock art 619

Michaël Peyrot

Slavic onъ, Lithuanian anàs and Tocharian A anac, anäṣ 633

Georges-Jean Pinault

Tocharian tsälp- in Indo-European perspective 643

Tijmen Pronk

Curonian accentuation 659

Per Methner Rasmussen

Some notes on Caesar’s De Bello Gallico liber II 671

Peter Schrijver

The first person singular of ‘to know’ in British Celtic and a detail of

a-affection 679

Stefan Schumacher

Old Albanian /u ngre/ ‘he/she arose’ 687

Matilde Serangeli

Lyc. Pẽmudija (N322.2): Anatolian onomastics and IE word formation 695

O. B. Simkin

The frontiers of Greek etymology 705

Roman Sukač

Is having rhythm a prerequisite for being Slovak? 717

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

xii Contents

Finn Thiesen

Paṩto etymologies: Corrections and additions to A new etymological

vocabulary of Pashto 731

Theo Vennemann gen. Nierfeld

Zum Namen der Cevennen 749

Brent Vine

Armenian lsem ‘to hear’ 767

Seán D. Vrieland

How old are Germanic lambs? PGmc *lambiz- in Gothic and Gutnish 783

Michael Weiss

King: Some observations on an East–West archaism 793

Paul Widmer & Salvatore Scarlata

Good to go: RV suprayāṇá- 801

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Luvian (SÍG) šūrita ‘balls of yarn’

Alexander Nikolaev

Boston University

This paper argues that Luv. (SÍG) šūrita ‘balls (of yarn)’ is etymological-

ly related to Gk. σφαῖρα ‘sphere, ball, globe’ and YAv. zgərəsna- ‘round,

circular’ (IE *sgwher‑).

1 Attestations

Nom.–acc. pl. šū̆rita is attested in the following passages from Hittite ritual

texts:

KBo 5.1 iii 55–iv 8 (Pāpanikri’s Ritual = CTH 476, MH/NS):

nu SÍG SA5 anda (iv 1) taruppanzi n=at=šan ANA TÚG šer (2) tianzi

šurita=ya iyanzi nu=za LÚ patiliš (3) wātar Ì.DÙG.GA dāi n=at=kan parā

pēdāi (4) nu SILA4 wetenit katta ānšanzi KA×U-an (5) GÌR=ŠU arḫa ārri

namma=an Ì.DÙG.GA-it (6) iškizzi nu=(š)šan SÍG SA5 ANA GÌR MEŠ =ŠU (7)

ḫamanki SÍG šūrita=ma=(š)ši=(š)šan ANA SAG.DU=ŠU anda ḫūlaliyanzi1

‘They collect the red wool, put it on top of the cloth (garment?) and

make (ready? ) šūrita. The patili-officiator takes water and good oil and

brings them. They wipe down the lamb with water; he washes its mouth

and foot. Then he anoints it with good oil. He attaches red wool to his

feet, while šurita- they wrap around his head’.

KUB 5.10+ Ro 7–10 (oracular text concerned the cult of Ištar of Nineveh =

CTH 567, NH):

EZEN ašraḫitaššin=wa kuwapi iyanzi (8) nu=wa ANA DINGIR LIM IŠTU

É.GAL LIM 1 GÌN KÙ.BABBAR SÍG SA5 SÍG ZA.GÌN 1-NUTUM KU ŠNÍG.

BÀR ḫI.A (9) pisker kinuna=wa EZEN ašraḫitaššin ier KÙ.BABBAR=ma=

1 Ed. Mouton 2008: 95–109.

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

568 Alexander Nikolaev

wa SÍG SA5 SÍG ZA.GÌN KUŠ NÍG.BÀR ḫI.A =ya (10) UL pier SÍG šurita=wa

wezzapanta2

‘when (before) they celebrated the ašraḫitašši-festival, they would offer

the goddess from the palace one shekel of silver, red wool, blue wool and

one set of curtains; now they celebrated the ašraḫitašši-festival, but did

not offer silver, red wool, blue wool or curtains, [and even] the šurita are

old’.3

The noun is also attested in ABoT 17 ii 6–7 (Birth Ritual of Kizzuwatna =

CTH 477A, MH), but this passage does not contribute much to our under-

standing of SÍG šurita because the governing verb is mutilated in both copies

of the text (the other being KUB 9.22 ii 11):

4 muriyališ katta gank[i] (7) SÍG šurita=ya=kan peran arḫa…4

‘Four grape(shaped)-loaves are hung down. And šurita in the front…’

Textual evidence for (SÍG) šūrita is limited to these three passages,5 but it seems

sufficiently clear that the word refers to conglomeration of wool that can be

wrapped around the lamb’s head (as in the Pāpanikri’s Ritual) or hung? at the

door (as in the Birth Ritual of Kizzuwatna). The standard translation of the

word is therefore ‘Ballen, (Woll)knäuel’ (Sommer & Eheloff 1924: 71), ‘ball,

skein of wool’ (Melchert 1993: 197). The characteristically Luvian stem in -it-

points to a Luvianism.6

In Hittite oracular texts we also find a term šuri which is a somewhat elu-

sive characteristic of entrails used in extispicy: according to Beal 2002: 63, if a

2 Ed. by Vieyra 1957: 132–33.

3 For translation of wezzapanta as a predicate see Wegner 1981: 104; slightly differ-

ently HEG II, 1208: “Alte Knäuel? (hat man geliefert)”.

4 For the verb Beckman 1983: 88 proposed k[ur]anzi ‘cut off ’, while Mouton 2008:

85 reads i[ya]nzi ‘make’.

5 KUB 14.23 6 is too broken to be informative. Beckman 1983: 100 restored a

form of šurit in KBo 31.108 i 8´–9´: -]zi SÍG miteškanzi (9) SÍG š]ūritaš dLAMÁ-aš

memiškizzi “they attach the wool … s/he speaks” (the use of mitai- would be

parallel to ḫūlaliyanzi in Pāpanikri’s Ritual), but see Starke 1990: 209 n. 686 who

argues for a different supplement of line 9 ([URU T]aurišaš). Finally, HEG II, 1208

mentions PN sù+ra/i-tà]-nu (Suritanu) allegedly written on a seal from Troy

VIIb (E9.573) in the Anatolian hieroglyphic script, but this reading has for the

most part been conjectured by edd. pr. who prudently add that “the microscopic

examination detects none of the postulated traces” (Hawkins & Easton 1996: 112;

see Alp 2001: 29 who argues for reading Tarhunta]nu).

6 See Starke 1990: 209.

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Luvian (SÍG) šūrita ‘balls of yarn’ 569

part of entrails or the zizahi ‘cyst caused by the larvae of tapeworm’7 was seen

to be šuriš, the polarity of the outcome is reversed.8 Given the abundance of

Hurrian terminology in Hittite oracular texts, the word šuri- is probably of

Hurrian origin and is unrelated to (SÍG) šūrita.9

2 Etymology

The word has no universally accepted etymology.10 Čop 1960: 6 (followed

by Rieken 1999: 479) argued that šūrita goes back to the root *s(i̯)eu̯h1- ‘to

sew’, but this suggestion is beset with morphological and semantic problems:

on the one hand, the ‑r‑ remains unaccounted for,11 and on the other hand,

there is no evidence that the word referred to sewn articles of any kind. A

new suggestion is called for.

This paper submits that Luv. šūrit‑ with the basic meaning ‘ball’ is related

to Gk. σφαῖρα ‘sphere, ball, globe’ which likewise has no good etymology

according to the standard works of reference.12 Morphologically the Greek

word is best analyzed as an *-ih2-derivative from a root noun *σφώρ / *σφαρ‑,

most likely an endocentric *-ih2-extension (compare Gk. φύζα vs. φύγ- in

7 Haas 2008: 61 (cf. Akkad. ziḫḫum ‘pustule, cyst’ on which see Biggs 1969: 163 n.

1).

8 For a full list of attestations see de Martino 1992: 154; for a discussion see Schuol

1994: 287–8.

9 See e.g. Starke 1990: 209: “Ein Zusammenhang mit dem hurr. Orakelterminus

šuri- > heth. šuri- c. […] besteht wohl nicht”. However, some scholars have

viewed šuri- and (SÍG) šūrita as forms of the same, originally Hurrian word (nota-

bly HEG 2, 1208).

10 EDHIL 792: “No further etymology”; Hurrian origin is advocated by HEG 2, 1208

(see n. 9 above).

11 In theory, one could consider a following derivational chain *s(i̯)eu̯h1- → *suh1‑ro

→ *suh1-ri → *suh1-ri-t, but in the absence of other *-ro- derivatives from the root

*s(i̯)eu̯h1- this analysis has little to recommend itself (eminently sensible critique

of Čop’s handling of this root can be found in Rasmussen 1989: 112–3, 118).

12 GEW 826: “Ohne außergriech. Entsprechung”, EDG 1427: “No cognates outside

Greek”. Hiersche 1964: 196–7, hesitantly followed by DELG and Peters 1980: 223,

proposed a connection to (ἀ)σπαίρω ‘pant, gasp’ (*sperH-), but the variation in

consonants (“qui doit être expressive”, DELG 1074) remains unexplained. Mas-

son 1986 argued that σφαῖρα is a Semitic loanword.

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

570 Alexander Nikolaev

φύγαδε or γλῶσσα vs. γλῶχες).13 Phonologically, the root of σφαῖρα may go

back to either *sbher‑ (*spher‑ with Siebs’ Law?) or *sgwher‑: the scales are

turned in favor of *sgwher‑ by YAv. zgərəsna- ‘round, circular’ (AiW 1698–9),

plausibly identified as a cognate of Gk. σφαῖρα by Scheftelowitz 1927: 229.

Scheftelowitz’ suggestion (made en passant in support of a different argu-

ment), has never got much traction among etymologists, but the compari-

son is impeccable both formally (Transponat *sgwhr̥tsno14) and semantically.

The meaning ‘round’ appears to be fairly certain to judge from the three

attestations of zgərəsna-: at V. 14.10 the compound zgərəsnō.vaγδana- ‘with

a rounded head’ describes a pestle (the Pahlavi gloss is gird waγdān ‘round-

topped’), at Frahang ī ōīm 20 the lemma +zgərəsnəm is provided with the

same translation gird ‘round’, and at N. 76.1 (Kotwal & Kreyenbroeck = 94

D.) loc. du. uzgərəsnāuuaiiō may refer either to headdress15 or to a couple of

blousy garments.16. YAv. zgərəsna- is not isolated in Iranian, as was noticed

already by Bartholomae 1899: 7–9, who realized that Mid. Pers. gird ‘round’

(never wird17), Mod.Pers. gird ‘around’ must be related to this root and not

to *u̯ert‑ ‘turn’.18

13 σφαῖρα could also be a possessive *ih2- derivative of the type μέλισσα (Att.

μέλιττα) ‘bee’ < *melit-i̯a- ‘having honey’ (μελιτ-), ϑρίσσα (Att. ϑρίττα) ‘a “hairy”

fish’ < *thrik(h)-i̯a ‘having hair’ (ϑρίξ, τριχ‑) or ἄγυια ‘street’ < *‘having lead-

ing’ (*h2eg̑us- from the root of Greek ἄγω, Latin agō); see on this type Jochem

Schindler apud Peters 1980: 200.

14 For word formation compare Av. raoxšna- ‘shining’, n. ‘light’ (< *leu̯ksno-, cf. Lat.

lūna ‘moon’) or its counterpart in Sanskrit jyotsnā ‘moonlight’ (jyut- ‘to shine’).

On the strength of these derivational parallels the *-t- in the Proto-Indo-Iranian

Transponat *sgr̥t-sna should be analyzed as part of the root: most likely, the den-

tal is due to lexical contamination with the Indo-Iranian root *u̯art- ‘to turn

around’ and its reflexes, see below, n. 18.

15 So Bailey 1970: 29, whose main reason for this interpretation is the Pahlavi trans-

lation gird waγdān ‘round-topped’ (but see Kotwal & Kreyenbroeck 2009: 47 n.

97 who argue that the commentator adopted this translation of unclear Avestan

expression from V. 14.10; for the same reason they consider unnecessary Waag’s

emendation to uzgərəsnō.vaγδana as in the Vendidad passage).

16 So Kotwal & Kreyenbroeck 2009: 47 n. 97.

17 Contrast Av. varəta-, Mid. Pers. (Bk. Pahl.) wrd ‘to turn’ (intr.), Mod. Pers. gāšt

‘to turn’ (tr.) or Av. vazra-, Mid. Pers. (Bk. Pahl.) wazr, Mod. Pers. gurz ‘cudgel’.

18 Other Iranian cognates may include Sogdian prγrs’y ‘round’ (if from

*pari‑gr̥ts, see Gharib 1995: 286), Šughni žurn ‘round’ (if from Proto-Iranian

*garθna-, see Morgenstierne 1974: 111) or Wakhi γ̆ərt ‘round’ (see Steblin-

Kamenskij 1999: 190), but while these and other forms assembled in ESIJa 3:

196–203 under the heading *gart‑ ‘to turn; round, spherical’ may point to an

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Luvian (SÍG) šūrita ‘balls of yarn’ 571

3 PIE *sgw( h)‑ > Proto-Luvic *su̯‑ > Luv. šu‑?

To sum up our results so far, a root *sgwher‑ ‘(to be) round’ can be recon-

structed on the strength of Gk. σφαῖρα and YAv. zgərəsna- (along with its

congeners in Middle and Modern Iranian). It appears that this root can also

give us Luv. šūrit‑ ‘ball (of wool)’. The stem šūrit‑ is most straightforwardly

analyzed as containing the denominative suffix ‑id‑ (compare Luv. paḫḫit-

‘beater’ from the root paḫḫ‑ found in Hittite paḫḫiya- ‘to beat’).19 Based on

what we know about Luvian historical phonology at present, the remaining

sequence šūr can directly continue a PIE root noun *sgwhor‑ / *sgwhr̥‑, even

though the precise sequence of sound changes required cannot be indepen-

dently demonstrated.

While Luvian undoubtedly simplified initial *sT- clusters by deleting the

sibilant (cf. Luv. tūmmant- ‘ear’ vs. Hitt. ištāman‑ ‘id.’20), it is important to

bear in mind that at the Proto-Luvic stage the (unconditional) deocclusion

of gw would have already taken place and our root would have looked like

*su̯ar‑.21 Now, we simply have no evidence to tell us the fate of initial *s + so-

norant in Luvian, and I know of no counterexamples to the following chain

of phonological developments: PIE *sgwhor‑ > PA *sgwar‑ > PLuvic *su̯ar‑ >

PLuvic *suu̯ar‑ with epenthesis > šūr‑ with contraction and accent retrac-

tion.22 Zero-grade *sgwhr̥- would probably give the same result: PA *sə gwur-23

> PLuvic *suu̯ar‑ > šūr‑ (cf. Luv. kuu̯ar- / kūr- (ku-ú-rV-) ‘to cut’, Hitt. 3 pl.

kuranzi < PIE *kwr̥-). If the phonology works, Gk. σφαῖρα, YAv. zgərəsna-

and Luv. šūrita fit together as if dovetailed.24

s-less version of the IE root *sgwher- posited above (as Bartholomae 1899: 8 sug-

gested), they may also result from contamination with reflexes of the Proto-Ira-

nian root *u̯art- with a very similar meaning.

19 See HED 8: 3–4. Incidentally, the root paḫḫ finds an etymological match in Gk.

πηρός, Lesbian πᾶρος ‘infirm, invalid, blind, lame’: this word (labeled as “iso-

lated” in EDG 1188) likely continues *peh2-ró- ‘beaten, maimed’.

20 See Melchert 1994: 271. Yakubovich 2009: 553 has recently argued that s- would

disappear before any consonant, but cf. Melchert (forthcoming). Rieken 2010:

657 suggested that initial *s‑ was not lost before a velar stop.

21 See Melchert 1994: 239.

22 For accent retraction in what must have been no longer morphologically analyz-

able stem see Yates 2015.

23 For *R̥ > uR cf. HLuv. zurnid- ‘horn’ < *k̑r̥ng-id (Hitt. karkidant- ‘horned’, Skt.

śŕ̥ṅga- ‘horn’; for the reading of hieroglyphic sign 448 as zú see Melchert 2012).

24 It might not be unreasonable to speculate that sg. šuriš, used to qualify the zizahi-

cyst in oracular texts, is not an unrelated Hurrian word (despite p. 2 above), but

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

572 Alexander Nikolaev

References

AiW = Christian Bartholomae. 1904. Altiranisches Wörterbuch. Strassburg:

Trübner.

Alp, Sedat. 2001. Das Hieroglyphensiegel von Troja und seine Bedeutung für

Westanatolien. In Gernot Wilhelm (ed.), Akten des IV. Internationalen

Kongresses für Hethitologie (Würzburg, 4.–8. Oktober 1999), 27–31. Wies-

baden: Harrassowitz.

Bailey, H[arold] W. 1970. A range of Iranica. In Mary Boyce & Ilya Ger-

schevitch (eds.), W. B. Henning memorial volume, 20–36. London: Lund

Humphries.

Bartholomae, Christian. 1899. Arica XI. IF 10. 1–19.

Beal, Richard H. 2002. Hittite oracles. In Leda Ciraolo & Jonathan Seidel

(eds.), Magic and divination in the ancient world, 57–82. Leiden, Boston

& Köln: Brill.

Beckman, Gary M. 1983. Hittite birth rituals (Studien zu den Boğazköy-

Texten 29). 2nd rev. ed. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Biggs, R[obert] D. 1969. Qutnu, maṣraḫu and related terms in Babylonian

extispicy. Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 63. 159–167.

DELG = Pierre Chantraine. 1968–1980. Dictionnaire étymologique de la

langue grecque: histoire des mots. Paris: Klincksieck.

EDG = Robert Stephen Paul Beekes. 2010. Etymological dictionary of Greek.

Leiden & Boston: Brill.

EDHIL = Alwin Kloekhorst. 2008. Etymological dictionary of Hittite inher-

ited lexicon. Leiden & Boston: Brill.

ESIJa = Vera Sergeevna Rastorgueva & Džoj Iosifovna Ėdelman, Ėtimolo

gičeskij slovar’ iranskix jazykov. Vol. 1–3. Moscow: Vostočnaja literatura,

2000–.

GEW = Hjalmar Frisk. 1960–1972. Griechisches etymologisches Wörterbuch.

Heidelberg: Winter.

Gharib, B[adr al-Zamān]. 1995. Sogdian dictionary: Sogdian – Persian – Eng-

lish. Tehran: Farhangan Publications.

Haas, Volkert. 2008. Hethitische Orakel: Vorzeichen und Abwehrstrategien.

Ein Beitrag zur hethitischen Kulturgeschichte. Berlin & New York: Walter

de Gruyter.

rather a form of the same stem šurit- in the meaning ‘ball, round (thing)’, refer-

ring to a particular shape of the cyst (viz. ‘round’ as opposed to elongated or

simply irregular shape?). But this is, of course, a mere guess.

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

Luvian (SÍG) šūrita ‘balls of yarn’ 573

Hawkins, J. David & Donald F. Easton. 1996. A hieroglyphic seal from Troia.

Studia Troica 6. 111–118.

HEG = Johann Tischler. 1977–. Hethitisches etymologisches Glossar (Inns-

brucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 20). Innsbruck: Institut für

Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

HED = Jaan Puhvel. 1984–. Hittite etymological dictionary. Vol. 1–8. Berlin &

New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hiersche, Rolf. 1964. Untersuchungen zur Frage der Tenues aspiratae im Indo-

germanischen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Kotwal, Firoze M. & Philip G. Kreyenbroeck. 2009. The Hērbedestān and

Nērangestān. Vol. 4. Paris: Association pour l’avancement des études ira-

niennes.

de Martino, Stefano. 1992. Die mantischen Texte (Corpus der Hurritischen

Sprachdenkmäler 1(7)). Rome: Bonsignori.

Masson, Michel. 1986. Sphaira, sphairōtēr. BSL 81. 231–252.

Melchert, H. Craig. 1993. Cuneiform Luvian lexicon. Chapel Hill: self-pub-

lished.

Melchert, H. Craig. 2012. Luvo-Lycian dorsal stops revisited. In Roman

Sukač & Ondřej Šefčík (eds.), The sound of Indo-European 2: Papers on

Indo-European phonetics, phonemics and morphophonemics, 206–218.

München: Lincom.

Melchert, H. Craig. Forthcoming. Initial *sp- in Hittite and šipand- ‘to libate’.

Morgenstierne, Georg. 1974. Etymological vocabulary of the Shughni group.

Wiesbaden: Reichert.

Mouton, Alice. 2008. Les rituels de naissance kizzuwatniens. Un exemple de

rite de passage en Anatolie hittite. Paris: de Boccard.

Peters, Martin. 1980. Untersuchungen zur Vertretung der indogermanischen

Laryngale im Griechischen (Österreichische Akademie der Wissens-

chaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse 377). Wien: Verlag der Öster-

reichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften

Rasmussen, Jens Elmegård. 1989. Studien zur Morphophonemik der indoger-

manischen Grundsprache (Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft

55). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

Rieken, Elisabeth. 2010. Das Zeichen <sà> im Hieroglyphen-Luwischen. In

Aygül Süel (ed.), Acts of the VIIth International Congress of Hittitology,

Çorum, August 25–31, 2008, 651–660. Ankara: Anıt Matbaa.

Scheftelowitz, J. 1927. Idg. zgh in den Einzelsprachen. ZVS 54. 224–253.

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

574 Alexander Nikolaev

Schuol, Monika. 1994. Die Terminologie des hethitischen SU-Orakels. AoF

21. 247–304.

Sommer, Ferdinand & Hans Eheloff. 1924. Das hethitische Ritual des Pāpa

nikri von Komana (KBo V 1 = Bo 2001). Texte, Übersetzungsversuch, Er-

läuterungen (Boghazköi-Studien 10). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

Starke, Frank. 1990. Untersuchung zur Stammbildung des keilschriftluwischen

Nomens (Studien zu den Boğazköy-Texten 31). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Steblin-Kamenskij, Ivan Mixajlovič. 1999. Ėtimologičeskij slovar’ vaxanskogo

jazyka. St. Petersburg: Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie.

Vieyra, Maurice. 1957. Ištar de Ninive (suite). Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéo-

logie orientale 51(3). 130–138.

Wegner, Ilse. 1981. Gestalt und Kult der Ištar-Šawuška in Kleinasien (Hurrito-

logische Studien 3). Kevelaer: Butzon und Bercker & Neukirchen-Vluyn:

Neukirchener Verlag.

Yakubovich, Ilya S. 2009. Anaptyxis in Hitt. *spand- ‘to libate’: One more case

of Luvian influence on New Hittite. In Nikolaj A. Bondarko & Nikolaj N.

Kazanskij, (eds.), Indoevropejskoe jazykoznanie i klassičeskaja filologija /

Indo-European linguistics and classical philology XIII, 545–557. St. Peters-

burg: Nauka.

Yates, Anthony D. 2015. Anatolian default accentuation and its diachronic

consequences. Indo-European Linguistics 3. 145–187.

© Museum Tusculanum Press and the author(s) 2017

You might also like

- Abusir and SaqqaraDocument159 pagesAbusir and SaqqaraReham100% (1)

- Archaic Greece New Approaches and New EvidenceDocument479 pagesArchaic Greece New Approaches and New EvidencePaulo E. Galdini100% (9)

- Akkade Is King A Collection of Papers byDocument346 pagesAkkade Is King A Collection of Papers byLuana Teixeira Barros LuaNo ratings yet

- Minni and MuninnDocument254 pagesMinni and MuninnXiomara Velázquez LandaNo ratings yet

- Tracing the Indo-Europeans: New evidence from archaeology and historical linguisticsFrom EverandTracing the Indo-Europeans: New evidence from archaeology and historical linguisticsBirgit Anette OlsenNo ratings yet

- Swords, Crowns, Censers and Books: Francia Media - Cradles of European CultureDocument56 pagesSwords, Crowns, Censers and Books: Francia Media - Cradles of European CultureAnte Vukic100% (1)

- (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 48) Anna Giacalone Ramat, Onofrio Carruba, Giuliano Bernini (Eds.)-Papers From the 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics-John Benjamins PublishingDocument689 pages(Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 48) Anna Giacalone Ramat, Onofrio Carruba, Giuliano Bernini (Eds.)-Papers From the 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics-John Benjamins Publishingjgaviramarcos100% (1)

- Sargent TechniqueDocument16 pagesSargent TechniqueTia Ram100% (2)

- Info 1Document28 pagesInfo 1Veejay Soriano Cuevas0% (1)

- Robot Project Report RoboticsDocument34 pagesRobot Project Report Roboticsdcrust_amit82% (11)

- Full Ebook of Usque Ad Radices Indo European Studies in Honour of Birgit Anette Olsen Bjarne Simmelkjaer Editor Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of Usque Ad Radices Indo European Studies in Honour of Birgit Anette Olsen Bjarne Simmelkjaer Editor Online PDF All Chaptermarsithsairi100% (10)

- (Ritus Et Artes, 7) Wojtek Jezierski, Lars Hermanson, Hans Jacob Orning, Thomas Småberg - Rituals, Performatives, and Political Order in Northern Europe, C. 650-1350-Brepols (2015)Document382 pages(Ritus Et Artes, 7) Wojtek Jezierski, Lars Hermanson, Hans Jacob Orning, Thomas Småberg - Rituals, Performatives, and Political Order in Northern Europe, C. 650-1350-Brepols (2015)BernardoyDiomiraNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of ThingsDocument166 pagesMaking Sense of ThingsBoppo Grimmsma100% (1)

- The Earliest Indo-Europeans in AnatoliaDocument15 pagesThe Earliest Indo-Europeans in Anatoliaruja_popova1178100% (1)

- Religion, Myth, and Folklore in The World's EpicsDocument601 pagesReligion, Myth, and Folklore in The World's EpicsDorinda100% (5)

- 214 200 1 PBDocument14 pages214 200 1 PBJéssica IglésiasNo ratings yet

- Contacts and Networks in The Baltic Sea Region: Austmarr As A Northern Mare Nostrum, Ca. 500-1500 AdDocument298 pagesContacts and Networks in The Baltic Sea Region: Austmarr As A Northern Mare Nostrum, Ca. 500-1500 AdAlexander SoltészNo ratings yet

- The Indo-European Puzzle RevisitedDocument358 pagesThe Indo-European Puzzle RevisitedfelipeNo ratings yet

- Zbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta I PDFDocument446 pagesZbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta I PDFEdita Vučić100% (1)

- Koerner e Andersen 1987 - Historical Linguistics 1987 Papers From The 8th International Conference On Historical Linguistics, Lille, August 31-September...Document589 pagesKoerner e Andersen 1987 - Historical Linguistics 1987 Papers From The 8th International Conference On Historical Linguistics, Lille, August 31-September...Gláucia Aguiar100% (1)

- Es Pak PeeterDocument157 pagesEs Pak PeeterNicole SigaudNo ratings yet

- Attilas Europe Structural TransformationDocument15 pagesAttilas Europe Structural TransformationБългарско Бранно УмениеNo ratings yet

- Rules and Misrules Hide Beamer VariabiliDocument19 pagesRules and Misrules Hide Beamer Variabilizsuzsanna.toth11No ratings yet

- Early Contacts Between Uralic and Indo European Linguistic and ArchaeologicalDocument456 pagesEarly Contacts Between Uralic and Indo European Linguistic and ArchaeologicalJoel ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Samoyedic Shamanic Drums Some Symbolic InterpretationDocument22 pagesSamoyedic Shamanic Drums Some Symbolic InterpretationGerard Canals PuigvendrelloNo ratings yet

- The Temples of Anahid at Estakhr SoutherDocument23 pagesThe Temples of Anahid at Estakhr SoutherRay DocNo ratings yet

- Ilok Ottoman MosqueDocument33 pagesIlok Ottoman MosqueAndrea RimpfNo ratings yet

- Anatoliaantiqua 303 PDFDocument11 pagesAnatoliaantiqua 303 PDFschauerNo ratings yet

- Aeolian Scripts 2014 - Studies in Honour of Viola T. Dobosi, Inventaria Praehistorica Hungariae 13, 2014Document344 pagesAeolian Scripts 2014 - Studies in Honour of Viola T. Dobosi, Inventaria Praehistorica Hungariae 13, 2014Paolo BiagiNo ratings yet

- Sacralization of Landscape and Sacred Places: Zbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta Instituti Archaeologici KnjigaDocument21 pagesSacralization of Landscape and Sacred Places: Zbornik Instituta Za Arheologiju Serta Instituti Archaeologici KnjigaTareNo ratings yet

- Scodel Ruth - Defining Greek NarrativeDocument393 pagesScodel Ruth - Defining Greek Narrativeernesto borges100% (2)

- Artumes in Etruria-LibreDocument47 pagesArtumes in Etruria-LibreВерка ПавловићNo ratings yet

- Sec 19 12Document10 pagesSec 19 12Visual AdditionNo ratings yet

- "Scripta Islandica" / "ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK", Vol. 65, 2014Document248 pages"Scripta Islandica" / "ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK", Vol. 65, 2014Before AfterNo ratings yet

- An Onvestigation Into The Origins of Domestic Sheep in The Southern Levant - ICAZ 1998 - Horwitz & DucosDocument19 pagesAn Onvestigation Into The Origins of Domestic Sheep in The Southern Levant - ICAZ 1998 - Horwitz & Ducosgjs77496No ratings yet

- From Late Bronze To Early Iron Age ThracDocument23 pagesFrom Late Bronze To Early Iron Age ThracVolkan KaytmazNo ratings yet

- Le Statut Juridique Des Cites Grecques PDFDocument25 pagesLe Statut Juridique Des Cites Grecques PDFAna Honcu0% (1)

- JRA 28 2015 56 Scherrer KouretesinEphesosDocument17 pagesJRA 28 2015 56 Scherrer KouretesinEphesosvladan stojiljkovicNo ratings yet

- 1Document19 pages1KonradNo ratings yet

- Ενότητα Γ - 5.EleusinianMysteries BremmerDocument27 pagesΕνότητα Γ - 5.EleusinianMysteries BremmerNick Psillakis100% (1)

- Attila'S Europe?: Structural Transformation and Strategies of Success in The European Hun PeriodDocument29 pagesAttila'S Europe?: Structural Transformation and Strategies of Success in The European Hun PeriodKiss AttilaNo ratings yet

- Epidaurus (Teatro)Document3 pagesEpidaurus (Teatro)VGVNo ratings yet

- A. Chaniotis, Unveiling Emotions (2012)Document465 pagesA. Chaniotis, Unveiling Emotions (2012)Adrian Drișcu100% (2)

- Homer's OgygiaDocument22 pagesHomer's OgygiaAbbey GrechNo ratings yet

- 0446 PDFDocument224 pages0446 PDFtyrue100% (2)

- Leszek Gardela Bad Death Final PreprintDocument4 pagesLeszek Gardela Bad Death Final PreprintHeather FreysdottirNo ratings yet

- (Intersections Volume 50) Enenkel, Karl A. E. - Smith, Paul J - Emblems and The Natural World (2017)Document701 pages(Intersections Volume 50) Enenkel, Karl A. E. - Smith, Paul J - Emblems and The Natural World (2017)analauraiNo ratings yet

- Spirit Possession: Multidisciplinary Approaches to a Worldwide PhenomenonFrom EverandSpirit Possession: Multidisciplinary Approaches to a Worldwide PhenomenonNo ratings yet

- What's in A NameDocument9 pagesWhat's in A NamehoweNo ratings yet

- Papers On Ancient Greek Linguistics - Finnish Society (2018)Document595 pagesPapers On Ancient Greek Linguistics - Finnish Society (2018)mariomb36No ratings yet

- Mystery of Runes and Turkic InscriptionsDocument16 pagesMystery of Runes and Turkic Inscriptionsyelbuke50% (2)

- Res, Artes et Religio: Essays in Honour of Rudolf SimekFrom EverandRes, Artes et Religio: Essays in Honour of Rudolf SimekSabine Heidi WaltherNo ratings yet

- Folklore in Old Norse - Old Norse in Folklore - Daniel Sävborg, Karen Bek-Pedersen - Nordistica Tartuensia, 20, 2014 - University of Tartu Press - 9789949327041 - Anna's ArcDocument190 pagesFolklore in Old Norse - Old Norse in Folklore - Daniel Sävborg, Karen Bek-Pedersen - Nordistica Tartuensia, 20, 2014 - University of Tartu Press - 9789949327041 - Anna's ArcCammyla SaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Czekaj-Zastawny Kabaciski Terberger-LongdistanceexchangeDocument20 pages2014 Czekaj-Zastawny Kabaciski Terberger-LongdistanceexchangeChu Dinh TuanNo ratings yet

- 4b2ac53a3ea2a005ddd7117a8a39eca4Document411 pages4b2ac53a3ea2a005ddd7117a8a39eca4YotaNo ratings yet

- Marazzi - FS Poettol PDFDocument30 pagesMarazzi - FS Poettol PDFmasmarazziNo ratings yet

- Myth & Symbol IDocument332 pagesMyth & Symbol Ismaragda2007100% (3)

- Lands of the Shamans: Archaeology, Landscape and CosmologyFrom EverandLands of the Shamans: Archaeology, Landscape and CosmologyDragos GheorghiuNo ratings yet

- From Dust To Dawn: Uppsala Rhetorical StudiesDocument28 pagesFrom Dust To Dawn: Uppsala Rhetorical StudiesIntegrante TreceNo ratings yet

- Textbook Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects From Central Greece To The Black Sea Georgios Giannakis Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects From Central Greece To The Black Sea Georgios Giannakis Ebook All Chapter PDFterrence.mcgee263100% (5)

- The Temple The Tree and The Well. in Old PDFDocument50 pagesThe Temple The Tree and The Well. in Old PDFJake McIvryNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Mythology PDFDocument43 pagesThe Origins of Mythology PDFТомислав Галавић100% (1)

- Archaeological Institute of AmericaDocument4 pagesArchaeological Institute of AmericaNéféret MéréretNo ratings yet

- Bcu Iasi / Central University Library: Some RomanianDocument4 pagesBcu Iasi / Central University Library: Some RomanianMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Time To Gather Stones Together GreekDocument18 pagesTime To Gather Stones Together GreekMar AlexNo ratings yet

- ThePlaceNamesofFifeandKinross 10294386Document73 pagesThePlaceNamesofFifeandKinross 10294386Mar AlexNo ratings yet

- Studies in Lycian and Carian Phonology ADocument30 pagesStudies in Lycian and Carian Phonology AMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Notes On Three Acrostatic Neuter S StemsDocument11 pagesNotes On Three Acrostatic Neuter S StemsMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Rigveda FullDocument597 pagesRigveda FullGhanesh RS67% (3)

- Revisiting Proto Indo European SchwebeabDocument174 pagesRevisiting Proto Indo European SchwebeabMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Hamp, Eric P., Some Notes On Istoria Limbii Romane by Al. Rosetti, SCL, An. 27, Nr. 2, 1976, P. 181-184Document4 pagesHamp, Eric P., Some Notes On Istoria Limbii Romane by Al. Rosetti, SCL, An. 27, Nr. 2, 1976, P. 181-184Mar AlexNo ratings yet

- Surface Gravity and Hawking Temperature From EntroDocument8 pagesSurface Gravity and Hawking Temperature From EntroMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Strange Ablauts and Neglected Sound ChanDocument23 pagesStrange Ablauts and Neglected Sound ChanMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Tocharian Special Agents The NT ParticipDocument18 pagesTocharian Special Agents The NT ParticipMar AlexNo ratings yet

- On The Origin of Grammatical GenderDocument6 pagesOn The Origin of Grammatical GenderMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Adrese TV 2016Document33 pagesAdrese TV 2016Mar AlexNo ratings yet

- Giacomo Santi, Università Per Stranieri Di Siena: Nominalizations in Hittite. A Typological ApproachDocument2 pagesGiacomo Santi, Università Per Stranieri Di Siena: Nominalizations in Hittite. A Typological ApproachMar AlexNo ratings yet

- The Language and Writing System of MS408 Voynich ExplainedDocument39 pagesThe Language and Writing System of MS408 Voynich ExplainedMar AlexNo ratings yet

- IRF5 Promotes Inflammatory Macrophage Polarization and T 1-T 17 ResponsesDocument9 pagesIRF5 Promotes Inflammatory Macrophage Polarization and T 1-T 17 ResponsesMar AlexNo ratings yet

- Hematopoietic Stem Cell: Self-Renewal Versus DifferentiationDocument14 pagesHematopoietic Stem Cell: Self-Renewal Versus DifferentiationMar AlexNo ratings yet

- An Algorithm For Pronominal Anaphora Resolution: Shalom Lappin" Herbert Leass TDocument28 pagesAn Algorithm For Pronominal Anaphora Resolution: Shalom Lappin" Herbert Leass TMar AlexNo ratings yet

- ZF5HP19FL VW+Audi+Porsche Gas North AmericaDocument63 pagesZF5HP19FL VW+Audi+Porsche Gas North Americadeliveryvalve100% (1)

- ObjectiveDocument22 pagesObjectiveKoratala HarshaNo ratings yet

- Computational Analysis of Centrifugal Compressor Surge Control Using Air InjectionDocument24 pagesComputational Analysis of Centrifugal Compressor Surge Control Using Air InjectionrafieeNo ratings yet

- Signals and Systems DE-40 EE - Semester 4 Spring 2020: Lab Report # 06Document21 pagesSignals and Systems DE-40 EE - Semester 4 Spring 2020: Lab Report # 06Muhammad YousafNo ratings yet

- Offset Flail Mowers: OFM3678, OFM3690 & OFM3698Document38 pagesOffset Flail Mowers: OFM3678, OFM3690 & OFM3698gomezcabellojosemanuelNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Design Document: GE401-Innovative Product Design & Development IDocument15 pagesPreliminary Design Document: GE401-Innovative Product Design & Development IvfoodNo ratings yet

- 4 WD SystemDocument126 pages4 WD SystemSantiago Morales100% (1)

- AV Control Receiver: Operating InstructionsDocument32 pagesAV Control Receiver: Operating InstructionsCuthbert Marshall100% (1)

- Dialysis: Prepared byDocument31 pagesDialysis: Prepared byVimal PatelNo ratings yet

- M.S. Al-Suwaidi Industrial Services, Co. Ltd. Hazard Identification PlanDocument6 pagesM.S. Al-Suwaidi Industrial Services, Co. Ltd. Hazard Identification PlanDarius DsouzaNo ratings yet

- Datasheet DiacDocument4 pagesDatasheet DiacOrlandoTobonNo ratings yet

- Company Analysis Report On M/s Vimal Oil & Foods LTDDocument32 pagesCompany Analysis Report On M/s Vimal Oil & Foods LTDbalaji bysani100% (1)

- Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis. Etiology, Anatomy, Pathogenesis, Classification, Clinical Picture, Diagnostics, Treatment and ComplicationsDocument36 pagesOdontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis. Etiology, Anatomy, Pathogenesis, Classification, Clinical Picture, Diagnostics, Treatment and ComplicationsАлександр ВолошанNo ratings yet

- University of Gondar Institute of Technology Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Project ProposalDocument32 pagesUniversity of Gondar Institute of Technology Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Project ProposalDasale DaposNo ratings yet

- Released FOR Manufacturing: 2509 ANTAMINA PERU SMC 100/14400 Truck Bridge Assembly Truck Bridge Steel Structure - RightDocument1 pageReleased FOR Manufacturing: 2509 ANTAMINA PERU SMC 100/14400 Truck Bridge Assembly Truck Bridge Steel Structure - RightCarlos ParedesNo ratings yet

- Playground Arduino CC Code NewPingDocument11 pagesPlayground Arduino CC Code NewPingimglobaltraders100% (1)

- 1974-5 Gibson Super 400CES PDFDocument6 pages1974-5 Gibson Super 400CES PDFBetoguitar777No ratings yet

- Silage Pile Sizing Documentation 5 12 2016 3Document9 pagesSilage Pile Sizing Documentation 5 12 2016 3Zaqueu Ferreira RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Horizontal Jaw RelationsDocument90 pagesHorizontal Jaw RelationsKeerthiga TamilarasanNo ratings yet

- MWR-SH11UN Installation+Manual DB68-08199A-01 ENGLISH 11092020Document20 pagesMWR-SH11UN Installation+Manual DB68-08199A-01 ENGLISH 11092020Jahir UddinNo ratings yet

- Skema Jawapan Instrumen Bi PTTS 2023Document9 pagesSkema Jawapan Instrumen Bi PTTS 2023Darina Chin AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Piping Info - Carbon Steel & Stainless Steel Guide SpacingDocument2 pagesPiping Info - Carbon Steel & Stainless Steel Guide SpacingpalluraviNo ratings yet

- Clinical Update: The Deficient Alveolar Ridge: Classification and Augmentation Considerations For Implant PlacementDocument2 pagesClinical Update: The Deficient Alveolar Ridge: Classification and Augmentation Considerations For Implant PlacementJordan BzNo ratings yet

- Apour Pressure For Liquid Vapour Equilibrium: Antoine'S Equation Fitting (T in Kelvin and P in Kpa)Document2 pagesApour Pressure For Liquid Vapour Equilibrium: Antoine'S Equation Fitting (T in Kelvin and P in Kpa)makari66No ratings yet

- Red Oxide Primer (ENG)Document3 pagesRed Oxide Primer (ENG)Evan BadakNo ratings yet

- Barang 3Document12 pagesBarang 3Sujoko SkinzNo ratings yet

- Lab1 - ArrayDocument6 pagesLab1 - Arrayezz AymanNo ratings yet