Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rethinking China's Rise: Chinese Scholars Debate Strategic Overstretch

Rethinking China's Rise: Chinese Scholars Debate Strategic Overstretch

Uploaded by

Muser SantiagoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rethinking China's Rise: Chinese Scholars Debate Strategic Overstretch

Rethinking China's Rise: Chinese Scholars Debate Strategic Overstretch

Uploaded by

Muser SantiagoCopyright:

Available Formats

Rethinking China’s rise: Chinese scholars

debate strategic overstretch

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

XIAOYU PU AND CHENGLI WANG *

The report of the 19th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress sets out an

ambitious goal for China’s national rejuvenation. It envisions that China will

become a ‘global leader in innovation, composite national strength, and inter

national influence in the coming decades’.1 In this report, Chinese leader Xi Jinping

describes China as a ‘Great Power’ (daguo) or a ‘strong power’ (qiangguo) 26 times.2

It is not surprising that a rising China seeks a more active global role. However, in

the context of shifting global power, a rising China faces dilemmas involving how

assertively to pursue its interests: acting provocatively too soon could generate

balancing and backlash, while ‘waiting too long could mean forgoing strategic

opportunities for substantial benefit’.3

Since the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, scholars in and on China have been

heatedly debating China’s status and role in the world.4 The continuing debate

reveals a high level of uncertainty over China’s position on the global stage. Some

scholars see the problems in the West—such as the global financial crisis, Brexit

and the Trump presidency—as strategic opportunities for China; in particular, an

inward-looking America under Trump as providing a new strategic opportunity

*

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2017 American Political Science Association (APSA)

Annual Meeting, the International Relations and East Asia (IREA) Online Colloquium, The Global Emerg-

ing Scholars Summit hosted by Tongji University, and at an international relations seminar hosted by Nankai

University. Our thanks to Ja Ian Chong, Thomas Christensen, Benjamin Creutzfeldt, John Delury, Kai He,

Eric Hundman, Liu Feng, Men Honghua, Dong Jung Kim, Jeehye Kim, Patricia Kim, Jiyoung Ko, Sun

Xuefeng, Tang Shiping, Christopher Twomey, Xu Jin, Brandon Yoder, Zhou Fangyin, Zuo Xiying and the

reviewers of International Affairs for their helpful comments.

1

Xi Jinping, Secure a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society in all respects and strive for the great success

of socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era, report delivered at 19th National Congress of the CCP,

Beijing, 18 Oct. 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/download/Xi_Jinping%27s_report_at_19th_CPC

_National_Congress.pdf. (Unless otherwise noted at point of citation, all URLs cited in this article were

accessible on 17 July 2018.)

2

Chris Buckley and Keith Bradsher, ‘Xi Jinping’s marathon speech: five takeaways’, New York Times, 18 Oct.

2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/18/world/asia/china-xi-jinping-party-congress.html.

3

For an analysis of rising powers in general, see David Edelstein, Over the horizon: time, uncertainty, and the rise of

Great Powers, Kindle edn (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017), p. 218.

4

See e.g. Thomas Christensen, The China challenge: shaping the choices of a rising power (New York: Norton, 2015),

pp. 3–8; Xiaoyu Pu, ‘Controversial identity of a rising China’, Chinese Journal of International Politics 10: 2,

2017, pp. 131–49; Xiaoyu Pu, Rebranding China: contested status signaling in the changing global order (Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press, 2019); Jinghan Zeng and Shaun Breslin, ‘China’s “new type of Great Power rela-

tions”: a G2 with Chinese characteristics?’, International Affairs 92: 4, July 2016, pp. 773–94; Zhang Yunling,

‘China and its neighbourhood: transformation, challenges and grand strategy’, International Affairs 92: 4, July

2016, pp. 835–68.

International Affairs 94: 5 (2018) 1019–1035; doi: 10.1093/ia/iiy140

© The Author(s) 2018. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of The Royal Institute of International

Affairs. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1019 29/08/2018 16:38

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

for China to expand its power and influence on the global stage.5 However, others

worry that Beijing’s policy-makers might have taken steps too bold and too soon,

and they see the warning signs. In the latest version of the US National Security

Strategy, China is identified as a ‘revisionist power’ that challenges US values

and interests.6 Meanwhile, there has been a backlash against increasing Chinese

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

influence across several western countries, where there are anxieties about China’s

‘sharp power’, a term used to refer to the information warfare being waged by

authoritarian regimes.7 In international relations, competition between rising

powers and established powers can be dangerous.8 To avoid confrontation and

conflict, rising powers must carefully design and implement their grand strategies,

sending reassuring messages to neighbouring countries as well as to the established

powers.9 Some scholars in China worry that there might be plausible connections

between China’s assertive foreign policy and increasing perceptions in the West

of threat from China.10 Although the new wave of ‘China threat’ discourse may

have complicated sources,11 the recent backlash against China is a wake-up call

for Beijing.

In recent years, some Chinese elites have started to rethink the strategies and

tactics of China’s rise. For instance, Renmin University Professor Shi Yinhong

has published a series of articles on this topic. In these writings, Shi suggests

that China might face a problem of ‘strategic overdraft’ or ‘strategic overstretch’

(zhanlue touzhi).12 For most scholars, the essence of strategic overstretch is similar

to the economics of cost–benefit analysis: strategic overstretch occurs if the cost of

maintaining the existing system exceeds the benefits it yields. The British historian

Paul Kennedy proposed the idea of ‘imperial overstretch’ to explain the imbalance

between strategic commitments and the economic base.13 In the Chinese context,

Shi defines strategic overstretch more broadly as the lack of focus or mismatch

5

For a recent analysis of the Chinese perspective, see Astrid H. M. Nordin and Mikael Weissmann, ‘Will

Trump make China great again? The Belt and Road Initiative and international order’, International Affairs 94:

2, March 2018, pp. 231–49. Some American scholars also think this way: see Randall Schweller, ‘Opposite but

compatible nationalisms: a neoclassical realist approach to the future of US–China relations’, Chinese Journal

of International Politics 11: 1, 2018, pp. 23–48.

6

The White House, The National Security Strategy of the United States (Washington DC, 2017), p. 25.

7

Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig, ‘From “soft power” to “sharp power”: rising authoritarian influence

in the democratic world’, in The International Forum for Democratic Studies, eds, Sharp power: rising authori-

tarian influence (Washington DC: National Endowment for Democracy, 2017).

8

Graham Allison, Destined for war: can America and China escape Thucydides’s trap? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Harcourt, 2017); Ronald L. Tammen and Jack Kugler, ‘Power transition and China–US conflicts’, Chinese

Journal of International Politics 1: 1, 2006, pp. 35–55; John J. Mearsheimer, ‘The gathering storm: China’s chal-

lenge to US power in Asia’, Chinese Journal of International Politics 3: 4, 2010, pp. 381–96.

9

For a detailed discussion of China’s reassurance strategy, see Avery Goldstein, Rising to the challenge: China’s

grand strategy and international security (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005).

10

See e.g. Zuo Xiying, ‘Zhanlue jinzheng shidai de zhongmeiguanxi tujin’ [Roadmap of Sino-American rela-

tions in the era of strategic competition], Zhanlue jueche yanjiu [Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 2,

2018, pp. 79–88.

11

For a Chinese perspective, see Zhao Kejin, ‘Xin yilun “zhongguo weixielun”, xin zai na’ [New wave of

China threat thesis, what is new?], Huanqiushibao [Global Times], 2 Feb. 2018, http://opinion.huanqiu.com/

hqpl/2018-02/11576518.html.

12

Shi uses the term ‘strategic overdraft’ to translate zhanlue touzhi. But the meaning is almost the same as ‘stra-

tegic overstretch’, which is a more commonly used term in the western IR and strategic studies literature.

13

Paul Kennedy, The rise and fall of the Great Powers: economic change and military conflict from 1500 to 2000 (London:

Unwin Hyman, 1987).

1020

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1020 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

between strategic goals and tactics.14 In March 2017, a special workshop on China’s

foreign policy and strategic overstretch was organized by Zhou Fangyin at Guang-

dong University of Foreign Studies.15 Participants in the workshop included

scholars from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Tsinghua University and

Nankai University, as well as policy-makers from the Chinese Foreign Ministry.16

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

Most of the papers presented were later published as a special issue of the Journal

of Strategy and Decision-making (Zhanlue jueche yanjiu) in 2017. Chinese scholars also

published their opinions on the topic through other journals and media outlets.

Luo Jianbo, a professor at the Central Party School of the CCP, published an

influential essay calling for the Chinese government to prioritize domestic welfare

rather than seeking world leadership.17 Through various media outlets, Tsinghua

Professor Yan Xuetong has argued that China should clarify the priority of its

national interests and avoid ‘strategic rash advance’ (zhanlue maojin).18

Why has the topic of strategic overstretch become increasingly salient in China’s

foreign policy community? Why do Chinese scholars take different positions on

the issue? What are the implications for Chinese foreign policy and international

relations? This article aims to provide an updated analysis of Chinese strategic

debate that will shed new light on Chinese foreign policy. The first section explains

why the debate over China’s strategic overstretch is interesting and important.

The second section analyses the context of the debate, highlighting the changing

domestic and international contexts. The third section interprets the scholarly

debate. The fourth section discusses implications for Chinese foreign policy. The

conclusion summarizes the findings and implications.

Why does the debate matter?

The debate over strategic overstretch may seem an unlikely and counter-intuitive

phenomenon in Chinese foreign policy. First, while most studies on the topic in

the western IR literature focus on cases of empire, hegemonic power or established

powers,19 contemporary China is instead a rising power. Second, Chinese internal

14

Shi Yinhong, ‘Chuantong zhonguo jingyan yu dangdai zhongguo shijian: zhanlue tiaozheng, zhanlve touzhi

yu weida fuxing wenti’ [Traditional Chinese experience and contemporary Chinese practice: strategic adjust-

ment, strategic overdraft, and national rejuvenation], Waijiao pinglun [Foreign Affairs Review], no. 6, 2015, pp. 57–68.

15

Guangdong University of Foreign Studies has recently become one of the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s key

partners of policy research. The other key partners include, among others, Peking University, Fudan Univer-

sity and Tsinghua University.

16

Xiaoyu Pu attended this workshop in March 2017.

17

Luo’s article was originally published in the Financial Times (Chinese edition), and later was widely distributed

in China’s social media. But it was eventually censored in China and was also taken down from its original

website. Some overseas Chinese websites still have the article. See Luo Jianbo, ‘Zhongguo de jiushizhu xintai

yao bude’ [China should avoid the mindset of a world saviour], Xianggangshangbao [Hongkong Business], 25 May

2017, http://www.hkcd.com/content/2017-05/25/content_1049740.html.

18

Yan Xuetong, ‘Zhongguo yinggai mingque guojialiyi paixu, fangfan zhanlue maojin’ [China should clarify

priority of national intersts, avoid strategic rash advance], Fenghuangwang [Phoenix Satellite TV Website],

3 Aug. 2017, http://pit.ifeng.com/a/20170803/51555156_0.shtml.

19

For research and debate on strategic overstretch in the western context, see Kennedy, The rise and fall of the Great

Powers; Paul K. MacDonald and Joseph M. Parent, ‘Graceful decline? The surprising success of Great Power

retrenchment’, International Security 35: 4, 2011, pp. 7–44; Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry and William C.

Wohlforth, ‘Don’t come home, America: the case against retrenchment’, International Security 37: 3, 2013, pp. 7–51.

1021

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1021 29/08/2018 16:38

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

debate over strategic overstretch may present a contrast with China’s image on the

global stage.20 It is widely known that China under Xi Jinping has pursued a much

more ambitious and assertive foreign policy at both regional and global levels.21

Why would Chinese elites consider strategic overstretch a potentially important

problem? Third, given tightening political control and censorship in China,22

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

it is surprising to find any discussions that deviate noticeably from the official

propaganda line. By demonstrating the existence of diverse opinion in China, our

study might potentially challenge the image of the monolithic Chinese state.23

The scholarly debate provides a window on Chinese foreign policy. An

increasing amount of research focuses on the relationship between the academic

world and foreign policy making in China.24 China’s foreign policy-making process

has become increasingly complicated, with different institutions and government

agencies sometimes advocating different interests.25 The increasingly complex

decision-making process has created space for a variety of voices to emerge. To

conceptualize the relationship between scholars and the foreign policy-making

process in China, Huiyun Feng and Kai He suggest that there are four models: the

epistemic community model, the free market model, the signalling model and the

mirroring policy model.26 These different models highlight different relationships

between scholarly debates and policy-making circles in China. It should be noted

that these four models are heuristic frameworks that may help us understand the

relationship between the academic world and the policy process in China; they

are not meant to be mutually exclusive.

We propose an information model that combines the insight from both the

mirroring policy model and the signalling model. In the proposed information

model, the relationship between academic research and policy decision-making is

a two-way process. First, IR scholars can serve as a ‘mirror’ to reflect the orienta-

tion of Chinese policy-makers. This might reflect a general cross-national pattern

20

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this point.

21

Xiaoyu Pu, Dingding Chen and Alastair Iain Johnston, ‘Debating China’s assertiveness’, International Security

38: 3, 2014, pp. 176–83; Nien-chung Chang Liao, ‘The sources of China’s assertiveness: the system, domestic

politics or leadership preferences?’, International Affairs 92: 4, July 2016, pp. 817–33; Nordin and Weissmann,

‘Will Trump make China great again?’.

22

Gary King, Jennifer Pan and Margaret E. Roberts, ‘How censorship in China allows government criticism

but silences collective expression’, American Political Science Review 107: 2, 2013, pp. 1–18; Margaret E. Roberts,

Censored: distraction and diversion inside China’s great firewall (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018).

23

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

24

Bonnie Glaser and Phillip Saunders, ‘Chinese civilian foreign policy research institutes: evolving roles and

increasing influence’, China Quarterly, no. 171, 2002, pp. 597–616; David Shambaugh, ‘China’s international

relations think tanks: evolving structure and process’, China Quarterly, no. 171, 2002, pp. 575–96; Quansheng

Zhao, ‘Epistemic community, intellectuals, and Chinese foreign policy’, Policy and Society 25: 1, 2006, pp.

39–59; Bonnie Glaser and Evan Medeiros, ‘The changing ecology of foreign policy-making in China: the

ascension and demise of the theory of “peaceful rise”’, China Quarterly, no. 190, 2007, pp. 291–310; Huiyun

Feng and Kai He, ‘How Chinese scholars think about Chinese foreign policy’, Australian Journal of Political

Science 51: 4, 2016, pp. 694–710; Huiyun Feng and Kai He, ‘Why Chinese international relations (IR) scholars

matter: understanding the rise of China through the eyes of Chinese IR scholars’, paper presented at Griffith–

Tsinghua workshop, ‘Chinese scholars debate International Relations’, December 2016, Beijing; Xu Jin and

Li Wei, Gaige kaifang yilai zhongguo duiwai zhengce bianqian yanjiu [The study of China’s foreign policy change

in the opening and reform era] (Beijing: Social Science Academic Press, 2016).

25

Qingmin Zhang, ‘Bureaucratic politics and Chinese foreign policymaking’, Chinese Journal of International

Politics 9: 4, 2016, pp. 435–58.

26

Feng and He, ‘Why Chinese international relations (IR) scholars matter’.

1022

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1022 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

of academic–policy relationship as well as some Chinese characteristics. As many

IR scholars take a problem-driven approach to research, it is natural that their

research might resonate with the concerns of policy-makers in their country.27 In

the Chinese context, too, the government has used funding opportunities to shape

the research agenda of scholars.28 Second, scholarly research serves an important

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

feedback function for policy-makers. Chinese scholars are increasingly partici-

pating in policy deliberation processes hosted by a range of government institu-

tions. These scholars may be able to shape foreign policy through various channels,

including consultations with policy-makers, internal reports, conferences, public

policy debates and so on.29 The scholarly debate could help the Chinese govern-

ment to test the waters with potential policies. In the foreign policy process, it

makes sense to collect reactions from both domestic and international audiences,

and the scholarly debate can facilitate this process.30

As we emphasize the policy relevance of Chinese scholarly debate, so we should

also note some caveats. First, China has a vibrant scholarly community of IR

specialists, and there are genuine academic debates on a variety of issues.31 Think-

tanks in China do not just promote the government policy agenda; they can also

potentially play a public advocacy role to promote policy change.32 In this sense,

we are not claiming that all scholars simply serve the propaganda purposes of the

Chinese government. Second, while we suggest that scholarly discussions serve

an important information function in shaping China’s foreign policy, we do not

exaggerate the role of scholars. In most cases, the scholarly discussions might shape

the implementation of policy, but they do not shape the fundamental direction

of policy decisions.33

Context

China’s international profile has changed dramatically in recent years, and the

debate over strategic overstretch occurs in a new era for Chinese foreign policy.

Just as in the cases of the British empire or American hegemony, the strategic

debate is shaped by economic circumstances and a changing international environ-

ment. The current debate over strategic overstretch is a part of China’s wider

discussions on its identity and role since the global financial crisis or even earlier.34

27

Jack Snyder, ‘One world, rival theories’, Foreign Policy, no. 145, 2004, pp. 52–62.

28

For instance, government funding shapes the research agenda of international law in China. See Anthea

Roberts, ‘China’s strategic use of research funding on international law’, Lawfare/Brookings Institution, 8

Nov. 2017, https://www.lawfareblog.com/chinas-strategic-use-research-funding-international-law.

29

Zhao, ‘Epistemic community, intellectuals, and Chinese foreign policy’, pp. 39–59.

30

Feng and He, ‘Why Chinese international relations (IR) scholars matter’, pp. 694–710.

31

David Shambaugh, ‘Coping with a conflicted China’, Washington Quarterly 34: 1, 2011, pp. 7–27; Pu, ‘Contro-

versial identity of a rising China’.

32

Xufeng Zhu, ‘Government advisors or public advocates? Roles of think tanks in China from the perspective

of regional variations’, China Quarterly, no. 207, 2011, pp. 668–86.

33

Xu Jin, ‘Debates in IR academia and China’s policy adjustments’, Chinese Journal of International Politics 9: 4,

2016, pp. 459–85.

34

Zeng and Breslin, ‘China’s “new type of Great Power relations”’; Jinghan Zeng, Yuefan Xiao and Shaun

Breslin, ‘Securing China’s core interests: the state of the debate in China’, International Affairs 91: 2, March

2015, pp. 245–66; Barry Buzan, ‘China in international society: is “peaceful rise” possible?’, Chinese Journal of

1023

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1023 29/08/2018 16:38

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

Within this wider context, several factors are especially salient in shaping the

context of the Chinese debate.

The global financial crisis impelled China to centre stage in global economic

governance. To some extent, China’s economic status has outgrown the expecta-

tions of the country’s political and intellectual elites. In a 2005 Foreign Affairs article,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

Zheng Bijian, a political adviser to the Chinese leadership, emphasized: ‘China’s

economy is one-seventh the size of the United States’ and one-third the size of

Japan’s.’35 It is likely the Chinese elites did not expect that, only five years later in

2010, China’s economy would surpass Japan’s. Since the global financial crisis shook

the legitimacy and leadership of the United States on the global stage, Chinese

scholars and commentators have been talking more about the rapid change of the

international order and China’s changing role in this shifting order.36 In particular,

there has been vociferous debate on whether China should keep the legacy of

Deng Xiaoping’s strategic guidance of tao guang yang hui (generally understood as

meaning a ‘low-profile’ approach).37 Deng’s strategic thinking about China’s inter-

national posture has had an enduring impact on China’s diplomacy. While China

has emerged from being a marginalized actor to become an emerging superpower

on the world stage, some Chinese elites still think that their country should keep

a low profile in international affairs.38 Others think it should pursue a strategy

of ‘striving for achievement’.39 Some take a middle approach, emphasizing that

‘continuity through change is a realistic description of China’s present interna-

tional strategy’.40

The election of Donald Trump as US president has generated uncertainty in

international relations. As America under the Trump presidency has become more

inward-looking, China has implemented a much more active global diplomacy,

taking new international initiatives and hosting many multilateral meetings.41

Does a more inward-looking America provide a golden opportunity for China to

play a more prominent role on the global stage? According to strategic thinker and

CNN commentator Fareed Zakaria, the answer is absolutely yes: ‘Trump could

be the best thing that has happened to China in a long time.’42 In the view of He

International Politics 3: 1, 2010, pp. 5–36. For analysis of China’s striving for status and role before the global

financial crisis, see Rosemary Foot, ‘Chinese strategies in a US-hegemonic global order: accommodating and

hedging’, International affairs 82: 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 77–94; Yong Deng, China’s struggle for status: the realignment of

international relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

35

Zheng Bijian, ‘China’s “peaceful rise” to great-power status’, Foreign Affairs 84: 5, 2005, p. 19.

36

Randall Schweller and Xiaoyu Pu, ‘After unipolarity: China’s visions of international order in an era of US

decline’, International Security 36: 1, 2011, pp. 41–72; Yong Deng, ‘China: the post-responsible power’, Wash-

ington Quarterly 37: 4, 2014, pp. 117–32; Pu, ‘Controversial identity of a rising China’.

37

Dingding Chen and Jianwei Wang, ‘Lying low no more? China’s new thinking on the tao guang yang hui strat-

egy’, China: An International Journal 9: 2, 2011, pp. 195–216.

38

Wang Jisi, ‘The view from China’, Foreign Affairs 97: 4, 2018, p. 184.

39

Chen and Wang, ‘Lying low no more?’; Xuetong Yan, ‘From keeping a low profile to striving for achieve-

ment’, Chinese Journal of International Politics 7: 2, 2014, pp. 153–84.

40

Yaqing Qin, ‘Continuity through change: background knowledge and China’s international strategy’, Chinese

Journal of International Politics 7: 3, 2014, pp. 285–314.

41

It should be noted that some of China’s new initiatives, such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the Asian

Infrastructure Investment Bank, were proposed long before Trump’s presidency. Trump is important in shap-

ing China’s policy thinking, but not all the changes are a result of his arrival in power in the US.

42

‘Trump could be the best thing that’s happened to China in a long time’, Washington Post, 12 Jan. 2017,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trump-could-be-the-best-thing-thats-happened-to-china-in-

1024

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1024 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

Yafei, a former vice foreign minister of China, the political developments of 2017

have accelerated the arrival of the ‘post-American era’, which started with the 2008

financial crisis.43 For many years, the United States urged China to take up the role

of a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the American-led global order, while China for its

part generally played a more passive role as a large developing country. Since the

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

2016 US election, however, world politics has entered an uncertain and turbulent

period, in which the United States and China in particular seem to be shifting in

their roles on the global stage. At the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in

Davos in January 2017, President Xi, drawing on China’s own experience, actively

defended globalization and offered a vision of inclusive, sustainable development.44

Xi also made a major speech at the UN in Geneva, highlighting the vision of

building a shared future for humankind; he even talked about humanitarian issues,

saying: ‘In the face of frequent humanitarian crises, we should champion the spirit

of humanity, compassion, and dedication and give love and hope to the innocent

people caught in dire situations.’45 Meanwhile, in his inauguration speech, US

President Donald Trump attacked American global engagement and highlighted

the ‘America first’ principle.46

In recent years, China has pursued a more active foreign policy. No longer

do Chinese leaders typically emphasize the ‘low-profile’ approach to global

affairs; now leaders and intellectuals alike enthusiastically embrace such concepts

as ‘global governance’ (quanqiu zhili) and the ‘China solution’ (zhongguo fangan).

Both these concepts have been mentioned with increasing frequency in China’s

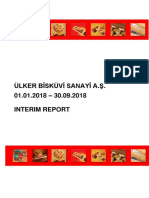

social science journals. A content analysis of Xi’s speeches shows that he too has

mentioned ‘global governance’ specifically more and more often in recent years

(see figure 1). Furthermore, the politburo of the CCP has held two special sessions

on global governance, at which two IR scholars—Qin Yaqing and Gao Fei from

the China Foreign Affairs University—were invited to give lectures to high-

ranking Chinese leaders.47

Despite occasional triumphalism in the Chinese media, China’s top elites remain

for the most part sober-minded.48 As China increasingly plays a more active role

on the global stage, some elite figures emphasize that it should take a positive and

a-long-time/2017/01/12/f4d71a3a-d913-11e6-9a36-1d296534b31e_story.html?utm_term=.a1214900a0ef; Nana

de Graaff and Bastiaan van Apeldoorn, ‘US–China relations and the liberal world order: contending elites,

colliding visions’, International Affairs 94: 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 113–32.

43

He Yafei, ‘The “American century” has come to its end’, Global Times, 20 Aug. 2017, http://www.globaltimes.

cn/content/1062243.shtml.

44

Xi Jinping, ‘President Xi’s speech to Davos in full’, World Economic Forum, 17 Jan. 2017, https://www.

weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/full-text-of-xi-jinping-keynote-at-the-world-economic-forum/.

45

Xi Jinping, ‘Speech by Xi Jinping at the United Nations office at Geneva’, China.org.cn, 25 Jan. 2017, http://

www.china.org.cn/chinese/2017-01/25/content_40175608.htm.

46

Donald J. Trump, ‘The inaugural address’, The White House, 20 Jan. 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/

inaugural-address; Peter Dombrowski and Simon Reich, ‘Does Donald Trump have a grand strategy?’, Inter-

national Affairs 93: 5, Sept. 2017, pp. 1013–38.

47

‘Xi Jinping emphasizes the importance of building a more fair and reasonable institution of global gover-

nance for China’s development and world peace’, Xinhua.net, 13 Oct. 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/

politics/2015-10/13/c_1116812159.htm; ‘Xi Jinping proclaims to strengthen cooperation in transforming the

global system of governance and promoting the peace and development of humanity’, Xinhua.net, 28 Sept.

2016, http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-09/28/c_1119641652.htm.

48

Wang, ‘The view from China’, p. 184.

1025

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1025 29/08/2018 16:38

Figure 1: Use of phrases ‘Global Governance’, ‘China Solution’ and their

synonym in Xi Jinping’s speeches and Chinese social science journals, 2012-

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

2017.

Figure 1: Use of phrases ‘global governance’, ‘China solution’ and their synonyms

in Xi Jinping’s speeches and Chinese social science journals, 2012-2017.

450 14

400 12

350

10

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

300

250 8

200 6

150

4

100

50 2

0 0

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Academic articles: 'global

124 175 188 227 393 424

goverance'

Academic articles: 'China

0 1 2 5 42 134

solution'

Xi Jinping: 'global governace' 0 3 7 11 9 12

non-zero-sum approach to global governance. For instance, Qin Yaqing empha-

sizes three

themes in China’s approach to global governance: multilateralism;

public goods provision; and the positive role of Chinese culture.49

Interpretations

As Chinese scholars debate strategic overstretch, what are the points of agree-

ment and difference among them? This section addresses this question by

analysing original Chinese materials from several sources: first, the special issue

of the Journal of Strategy and Decision-making (mentioned above), which published

revised papers from the Guangzhou workshop in 2017; second, articles published

by leading Chinese scholars in journals and media outlets that directly discuss

strategic overstretch; third, some Chinese articles focusing on specific policy issues

that indirectly reflect the discussions of strategic overstretch; and finally, several

rounds of interviews with Chinese scholars and policy-makers conducted by Pu.50

It should be noted that the materials were selected qualitatively rather than on

the basis of standardized criteria. This distinguishes our work from other studies

that analyse Chinese IR journals in a more quantitative way.51 While the external

validity or the extent to which the results of our study could be extended to a

49

Pu’s discussion with Qin Yaqing, president of China Foreign Affairs University, Ningbo, China, 18 May 2018.

Qin has elaborated some of his ideas in published work. See Yaqing Qin, ‘Rule, rules, and relations: towards

a synthetic approach to governance’, Chinese Journal of International Politics 4: 2, 2011, pp. 117–45; Yaqing Qin,

A relational theory of world politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 318–56.

50

The interviews were conducted in two formats. First, in 2017 and 2018, Pu made five trips to China for meetings

and research, during the course of which he took the opportunity to discuss the topic with dozens of leading

Chinese scholars and several policy-makers. For instance, this author met all participants of the Guangzhou

workshop in March 2017, and also interacted with Chinese strategic thinkers and senior diplomats in Beijing

in August 2017. Second, in early June 2018, Pu sent an email to six influential Chinese scholars, requesting

them to update him with new thinking on the debate. These interviews helped to identify new contributions

to the debate, and also to clarify the mechanisms by which academic and policy circles interact in China.

51

See e.g. Zeng et al., ‘Securing China’s core interests’; Zeng and Breslin, ‘China’s “new type of Great Power

relations”’.

1026

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1026 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

wider context might be limited, the purpose of the article is not to demonstrate

how widely these ideas might be distributed in China’s foreign policy community;

rather, our aim here is primarily to analyse the internal logic and policy context

of the debate. Our qualitative approach also has some advantages: we pay close

attention to the influence of the scholars in China’s foreign policy community,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

and Chinese materials are analysed on the basis of their theoretical frameworks as

well as their policy implications.

Most Chinese scholars agree that the topic itself is a useful one for China’s

foreign policy community to study. From the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to

the deployment of the Chinese military overseas, the country is actively involved

in various issues of global governance. China needs a well-designed strategy

to maintain a favourable environment for its rise. Even though some scholars

dispute the contention that it already has a problem of strategic overstretch, they

acknowledge the positive value of discussing the problem as a valuable reminder

for Chinese policy-makers.52 One senior military strategist said: ‘I believe the

Chinese leaders are wise enough not to make the mistake of strategic overstretch.

However, it is still useful for some scholars to discuss such an issue.’53

As Chinese scholars and analysts take different positions on the subject, how

do we classify the debate theoretically? In a general sense, grand strategy refers to

‘the distinctive combination of military, political, and economic means by which

a state seeks to ensure its national interests’.54 Three questions are related to grand

strategy: what are the core interests? What are the major threats? How can a

nation defend its interests against those threats?55 In this article, we focus on three

dimensions of grand strategic debate: goals, means and time horizon.

Regarding the goals of China’s grand strategy, Chinese scholars have different

interpretations of the priorities of China’s national interests. According to Shi

Yinhong, China is using both ‘strategic military’ (zhanlue junshi) and ‘strategic

economics’ (zhanlue jingji) to fulfil its long-term goal of expanding its power in

Asia and the western Pacific. The key question is how to keep an internal balance

between ‘strategic striving’ (zhanlue tujin) and ‘strategic prudence’ (zhanlue

shensheng).56 Shi identifies some worrisome trends: in the security domain, China

has had an increasingly tense relationship with several regional countries owing to

maritime disputes, and in economic statecraft, the BRI has dramatically expanded

the Chinese presence in many regions. Shi cautions that the country’s foreign

52

Liu Feng, ‘Zhanlue touzhi: yixiang gainian fenxi’[Strategic overstretch: a conceptual analysis], Zhanlue jueche

yanjiu [Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 3, 2017, pp. 25–30; Zhou Fangyin, ‘Fengfa youwei de shouyi

yu chengben’ [The cost–benefit analysis of striving for achievement], Zhanlue jueche yanjiu [Journal of Strategy

and Decision-making] 3, 2017, pp. 56–68.

53

Pu’s discussion with General Gong Xianfu, vice-chairman of the China Institute for International Strategic

Studies, Beijing, Aug. 2017. It should be noted that this attitude is widely shared within China’s foreign policy

community. See also Liu, ‘Zhanlue touzhi: yixiang gainian fenxi’.

54

Avery Goldstein, Rising to the challenge: China’s grand strategy and international security (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford

University Press, 2005), p. 17.

55

Wang Jisi, ‘China’s search for a grand strategy: a rising Great Power finds its way’, Foreign Affairs 90: 2, 2011,

pp. 68–79.

56

Shi Yinhong, ‘Guanyu zhongguo duiwai zhanlue youhua he zhanlue shensheng wenti de sikao’ [Thoughts

on strategic improvement and strategic prudence in foreign policy], Taipingyang Xuebao [Pacific Journal] 23: 6,

2015, pp. 1–5.

1027

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1027 29/08/2018 16:38

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

policy might have focused on too many projects. In this process, it might lose its

focus in the implementation of its strategy. According to Yan Xuetong, a wise

foreign policy starts from a clear definition of national interest. China’s ‘core

national interests’ is a vague concept in Chinese academic discourse, despite its

increasing use by the government to legitimize its diplomatic actions and claims.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

While there are some agreed bottom lines, there remains a lack of clarity about

what issues deserve to be defined as core interests.57 China has not yet developed

a coherent foreign policy strategy largely because it does not have a clear defini-

tion of its identity and status.58 Not surprisingly, China’s foreign policy often

demonstrates a contradictory tendency in practice. Using a metaphor, Ye Hailing,

a senior analyst at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), suggests that

Chinese foreign policy often has contradictory goals, just like a person who is

chasing two rabbits in opposite directions.59 In Shi Yinhong’s analysis, China’s

problem with strategic overstretch is obvious and has resulted in tense relation-

ships with neighbouring countries as well as the distractions arising from too

many concurrent projects. Yan Xuetong thinks that China is still a rising power,

not a global power, and that it should therefore give priority to its regional inter-

ests in Asia, rather than global interests.60 Scholars such as Shi and Yan believe

China has a problem with strategic overstretch or a strategically rash advance, as

they think its national interests should be more limited.

Others, however, think the concept of strategic overstretch is not applicable to

Chinese foreign policy. Nankai University Professor Liu Feng suggests that the

concept of strategic overstretch is poorly defined, and is often used in an inappro-

priate way.61 Liu defines strategic overstretch more rigorously and narrowly, and

argues that it occurs only where (1) the cost of expansion exceeds the capabili-

ties of resource absorption and mobilization, and (2) the strategy ultimately

causes permanent damage to a Great Power.62 Tsinghua University Professor

Sun Xuefeng emphasizes that strategic overstretch is primarily applicable in the

context of hegemonic power, empire or established power.63

Regarding the means of defending China’s interests, there are different inter-

pretations of the postures the country has taken. Some think China has become

overstretched and in doing so has generated regional tensions. However, other

scholars interpret China’s actions as defensive—the implicit assumption being that

if its posturing is largely defensive, it should not be viewed as strategic overstretch

no matter how costly its foreign policy behaviours might be. For instance, while

57

Zeng et al., ‘Securing China’s core interests’.

58

Pu, ‘Controversial identity of a rising China’.

59

Ye Hailing, ‘Zhanlue mubiao xuanze, zhanlve youxian fangxiang yu zhanglve touzhi de kenengxing’ [Choice

of strategic goal, strategic priority, and the possibilities of strategic overstretching], Zhanlue jueche yanjiu

[Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 3, 2017, pp. 12–17.

60

Yan Xuetong, ‘Waijiao zhuanxing, liyi paixu yu daguo jueqi’ [Diplomatic transformation, prioritizing of

interests, and the rise of Great Powers], Zhanlue jueche yanjiu [Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 3,

2017, pp. 4–12.

61

Liu, ‘Zhanlue touzhi: yixiang gainian fenxi’.

62

Liu, ‘Zhanlue touzhi: yixiang gainian fenxi’.

63

Sun Xuefeng, ‘Zhanlve xuanze yu jueqiguo zhanlve touzhi’ [Strategic choice and strategic overstretching of

rising powers], Zhanlue jueche yanjiu [Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 3, 2017, pp. 31–41.

1028

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1028 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

Shi Yinhong suggests that China’s overstretch might cause tensions with neigh-

bouring countries and the United States,64 scholars such as Zou Zhibo and

Zhou Fangyin argue that China is essentially defending its own sovereignty and

rights.65 This divide between defensive and expansive posturing is also reflected

in the discussions of the South China Sea disputes and Sino-American tensions.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

Regarding China’s maritime disputes, there are different opinions in China: some

propose that China should take a more assertive posture while others suggest that

it should seek accommodations with neighbouring countries.66 Regarding Sino-

American relations, some scholars speculate that China’s high-profile behaviour

(including exaggeration of China’s rise in domestic propaganda) might poten-

tially increase the threat perception of China in western countries, leading to

an increasing backlash from the United States.67 However, others suggest that

Sino-American relations are driven by structural factors and America’s domestic

politics, not assertive behaviour on China’s part.68

There are also different relative emphases on military and economic means in

China’s foreign policy. CASS scholar Gao Chen partially agrees with Shi’s analysis

on strategic overstretch. In evaluating China’s strategic challenges, Gao makes a

distinction between the security and economic domains. In the economic domain,

she argues, China is facing a danger of overstretch, as the efficiency of China’s

economic statecraft is problematic. However, in the security domain China’s

problem is the opposite: it is not that China is overstretched, but that it has not

done enough.69 The competing logics of security and economic means may be

especially relevant in discussion of the BRI. China has put huge resources into

implementing the BRI, and it has become Xi Jinping’s signature project. The

country has often implemented a strategy to promote political influence through

economic means, and the BRI can be viewed as an extension of this strategy.70 But

the BRI faces many challenges, including security threats, geopolitical competition

and regional backlash.71 While China might want to mitigate its security challenges

64

Shi, ‘Chuantong zhonguo jingyan yu dangdai zhongguo shijian: zhanlue tiaozheng, zhanlue touzhi yu weida

fuxing wenti’, pp. 57–68.

65

Zou Zhibo is a senior research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Social Science. Zhou Fangyin is a professor

and programme director at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies. See Zou Zhibo, ‘Yu shiyinhong jiu

zhanluetouzhi shangque’ [Debating strategic overdraft with Shiyin Hong], Fenghuangwang [Phoenix Satel-

lite TV Website], 26 Sept. 2016, http://news.ifeng.com/dacankao/bianshiyinhong/1.shtml; Zhou, ‘Fengfa

youwei de shouyi yu chengben’.

66

Fangyin Zhou, ‘Between assertiveness and self-restraint: understanding China’s South China Sea policy’,

International Affairs 92: 4, July 2016, pp. 869–90; Feng Zhang, ‘Chinese thinking on the South China Sea and

the future of regional security’, Political Science Quarterly 132: 3, 2017, pp. 435–66.

67

Zuo, ‘Zhanlue jinzheng shidai de zhongmeiguanxi tujin’.

68

Gao Chen, ‘Zhongmei jinzheng tiaojianxia dui “wending fazhan zhongmei guanxi” de zai shengshi’

[Re-examining the proposal of “developing stable Sino-American relations” in the context of Sino-American

competition], Zhanlue jueche yanjiu [Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 2, 2018, pp. 14–25.

69

Gao Chen, ‘Zhongguo zuowei juqi daguo de zhanlve touzhi wenti tanxi’ [The analysis of the strategic over-

stretch of China as a rising power], Zhanlue jueche yanjiu [Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 3, 2017,

pp. 49–55.

70

Xiaoyu Pu, ‘One Belt, One Road: visions and challenges of China’s geoeconomic strategy’, Mainland China

Studies 59: 3, 2016, pp. 111–32.

71

Xue Li, ‘Zhongguo “yidai yilu” zhanlue miandui de waijiao fengxian’ [The diplomatic risk of China’s One Belt

One Road strategy], Guoji jingji pinglun [International Economic Review], no. 2, 2015, pp. 68–79; Zhang Yunling,

‘One Belt, One Road’, Global Asia 10: 3, 2015, pp. 8–12; Peter Ferdinand, ‘Westward ho—the China dream and

1029

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1029 29/08/2018 16:38

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

through economic incentives, whether the BRI can mitigate its existing security

problems is debatable.72

The final factor shaping strategic thinking considered here is the time horizon.

While most scholars would agree that the essence of strategic overstretch is

similar to economic cost–benefit analysis, the political nature of strategic evalu-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

ation brings fundamental uncertainty and complexity to the discussion. Zhou

Fangyin highlights the time horizon as an important uncertain factor. The impact

of foreign policy is often apparent only in the long term, and it is difficult to use

short-term outcomes to judge the success or failure of a foreign policy initiative.

Instead of evaluating China’s strategy with reference to short-term interests and

returns, Zhou therefore suggests a long-term view be taken in judging Chinese

foreign policy. He argues that a grand strategy yields returns over a long period;

accordingly, it would be normal to see spending on a strategy exceeding its returns

during the early stages of its implementation. As long as the deficits are not persis-

tent, and the burden is not unsustainable for the national economy, there will be

no strategic overstretch.73

Time horizon is also related to another matter: the speed of China’s rise. Both

Yan Xuetong and Liu Feng suggest that the expansion of China’s power is a

natural tendency: a rising China should increase its power and raise its status in

the international arena. In this sense, strategic overstretch is largely not applicable

to a rising China.74 For established powers, the fundamental question is the scope

of their military and diplomatic presence, and there is a real danger of strategic

overstretch. For rising powers such as China, the key risk is not the scope and

direction of their expanding influence, but the speed and priorities of their rise.

According to Yan and Liu, China’s key problem is ‘strategic rash advance’ (zhanlue

maojin).75 Agreeing with Yan and Liu, Feng Chuanlu argues that China’s growing

influence in the Indian Ocean is not a case of strategic overstretch, but an inevi-

table expansion of influence as China’s interests are expanding internationally.76

Other scholars disagree. For instance, according to Jiang Peng, a maritime power

(such as the United States) could potentially strengthen alliances with China’s

neighbouring land powers to balance against China. A rising China should avoid

such a strategic overstretch problem by strengthening cooperation with neigh-

bouring countries.77

Above all, Chinese scholarly debate on strategic overstretch may reflect the

concerns of Chinese policy-makers, given the current pursuit by China of a more

ambitious foreign policy. There are many inherent difficulties and uncertainties

“One Belt, One Road”: Chinese foreign policy under Xi Jinping’, International Affairs 92: 4, July 2016, pp. 941–57.

72

Pu, ‘One Belt, One Road’.

73

Zhou, ‘Fengfa youwei de shouyi yu chengben’, pp. 56–68.

74

Yan, ‘Waijiao zhuanxing, liyi paixu yu daguo jueqi’; Liu, ‘Zhanlue touzhi: yixiang gainian fenxi’.

75

Yan, ‘Waijiao zhuanxing, liyi paixu yu daguo jueqi’; Liu, ‘Zhanlue touzhi: yixiang gainian fenxi’.

76

Feng Chuanlu, ‘Zhanlue touzhi yihuo zhanlue shenzhang’ [Strategic overstretch or strategic growth], Yinduy-

ang jingjiti yanjiu [Study of Indian Ocean Economy], no. 4, 2017, pp. 1–24.

77

Peng Jiang, ‘Hailu fuhexing daguo jueqi de “feili xianjin” yu zhanlue touzhi’ [The trap of Philip II and the

strategic overstretch of the rising of ocean and land powers], Dangdai yatai [Journal of Contemporary Asia-Pacific

Studies], no. 1, 2018, pp. 4–29.

1030

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1030 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

regarding strategic evaluations. CASS scholar Xu Jin suggests that the key feature

of strategic judgement is that it is an art belonging to political leaders.78 Chinese

scholars have different understandings of China’s national interests, and they also

differ on how strategic outcomes should be evaluated.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

Implications

Even though the overstretch debate has not yet changed Chinese foreign policy

in any fundamental way, it may reflect rethinking among Chinese elites about the

strategy and tactics of China’s rise on the global stage. These academic discussions

have important policy implications.

First, the debate reflects the strategic prudence and continuity of Chinese

foreign policy even as China has entered into a new era under the leadership of

Xi Jinping. Largely abandoning Deng Xiaoping’s low-profile approach in global

affairs, China under Xi has implemented a much more active and assertive foreign

policy. Some Chinese diplomats have started to talk about China’s leadership in

global governance more explicitly.79 As economic circumstances often shape

discussions of the trajectory of Great Powers, some Chinese analysts and officials

may have overestimated China’s rise and America’s decline since the global

financial crisis.80 The debate over strategic overstretch reflects the emergence of

a cautious voice in China’s foreign policy community. Shi Yinhong’s argument

has stimulated deep reflection on the challenges and problems in China’s regional

diplomacy.81 Fudan University Professor Tang Shiping cautions about the

tendency to overestimate China’s capabilities to remake the international order.82

Such a cautious attitude is not restricted to certain Chinese scholars; some senior

officials express a similar point of view. During his visit to Australia in 2017,

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi cautioned against an inflated expectation of

China’s global role, saying that ‘China has no intention to lead anyone, nor does

it intend to replace anyone … As the largest developing country, China is moving

to work tirelessly for upholding the legitimate rise and interest of the developing

countries.’83 For many decades, Chinese officials have avoided describing China

as a potential superpower. Chinese officials associate superpower status with

hegemony, which has negative connotations in the Chinese context. While the

international audience increasingly views China as an emerging superpower that

should take a leadership role, Chinese intellectuals and policy-makers are not

78

Xu Jin, ‘Cong yishu de jiaodu kan zhanlve touzhi’ [The art of analysing strategic overstretching], Zhanlue

jueche yanjiu [Journal of Strategy and Decision-making], no. 3, 2017, pp. 42–8.

79

Reuters, ‘Senior Chinese diplomat: China will assume world leadership if needed’, Business Insider, 23 Jan. 2017,

http://www.businessinsider.com/r-diplomat-says-china-would-assume-world-leadership-if-needed-2017-1.

80

Zhen Qin, ‘Jinrong weiji yu zhongguo jueqi de lishi jiyu’ [Financial crisis and the historic opportunity of

China’s rising], Qiushi, no. 1, 2009, pp. 59–63; Joseph S. Nye, ‘American and Chinese power after the financial

crisis’, Washington Quarterly 33: 4, 2010, pp. 143–53.

81

Shi, ‘Guanyu zhongguo duiwai zhanlve youhua he zhanlve shensheng wenti de sikao’.

82

Shiping Tang, ‘China and the future international order(s)’, Ethics and International Affairs 32: 1, 2018, pp. 31–43.

83

Julie Bishop and Wang Yi, ‘Australia–China foreign and strategic dialogue’, transcript of joint press confer-

ence, Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, 7 Feb. 2017, http://

foreignminister.gov.au/transcripts/Pages/2017/jb_tr_170207.aspx.

1031

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1031 29/08/2018 16:38

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

well prepared for China’s sudden high profile in global affairs, and some of them

continue to downplay the country’s elevated position.84

Second, the debate serves a useful feedback function for Chinese policy-

makers.85 While some Chinese scholars might doubt whether strategic overstretch

is applicable to China, designing and implementing a prudent grand strategy is

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

an enduring challenge for all Great Powers. The problem of overstretch could

be further driven by domestic politics. According to Jack Snyder, some interest

groups often justify their parochial interests in terms of national security, and

promote the myth of security through expansion.86 In his masterpiece The myths

of empire, Snyder tells a dramatic story of imperial Japan. Shortly before the attack

on Pearl Harbor, a Japanese colonel returned from a fact-finding mission to the

United States and provided a report to the chief of the Japanese army’s general

staff. According to the colonel’s analysis, the United States was capable of ten

times the war production Japan could muster. The chief of staff commended the

colonel for an excellent report, burned it, and had the author fired.87 In ignoring

prudent strategic analysis such as this, Japanese elites initiated an unwinnable war.

In the new era of Chinese foreign policy, the BRI is especially significant, having

the potential to transform China’s domestic and foreign policies in the years to

come. At the 19th CCP Congress, the BRI was enshrined in the party constitu-

tion.88 This could give political weight to Xi’s hallmark initiative, as institutions

and government agencies in China now have political incentives to implement the

BRI. But the new status of the BRI in the CCP constitution might also create new

political dynamics: will opposing the BRI be viewed as a politically risky behav-

iour, almost as bad as opposing the CCP? Contemporary China is different from

imperial Japan. Chinese leaders should be wise enough not to destroy any honest

internal analysis of the BRI. The scholarly debate provides a useful feedback

mechanism for Chinese policy-makers as they implement many projects related

to the BRI.

Third, the time horizon is especially interesting in relation to China’s foreign

policy and international politics. In international politics, the relationship between

the rising power and the established power is often difficult. In power transition,

two factors are key to shaping the power dynamics and the potential for conflict:

the extent to which the rising power is catching up with the established power,

and the extent to which the rising power is dissatisfied with the status quo within

the existing order.89 The Chinese debate on strategic overstretch reflects a third

dimension of power transition: the speed of China’s rise and of the power shift.90

84

Pu, ‘Controversial identity of a rising China’.

85

Pu’s correspondence with Zhou Fangyin, 8 June 2018.

86

Jack Snyder, Myths of empire: domestic politics and international ambition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press,

1991), pp. 14–19.

87

Snyder, Myths of empire, p. 112.

88

‘“Belt and road” incorporated into CPC constitution’, Xinhua, 24 Oct. 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com/

english/2017-10/24/c_136702025.htm

89

Jonathan DiCicco and Jack Levy, ‘Power shifts and problem shift: the evolution of the power transition

research program’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 43: 6, 1999, pp. 675–704.

90

For a book that brings the time horizon into theoretical discussion of power transition and the rise of China,

see Edelstein, Over the horizon.

1032

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1032 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

If China is eager to catch up with the United States in a short time, it will be more

difficult for the US to accommodate China’s increasing demands. However, if the

process of power shifting is gradual and incremental, this might create additional

space for both the rising power and the established power to make mutual adjust-

ments. According to IR scholar David Edelstein, the time horizon is important for

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

understanding competition and cooperation in Great Power politics.91 Despite the

fact that Great Powers have strategic incentives to compete, cooperation is likely

to emerge under two conditions: when existing powers are focused on short-

term benefits, deferring anticipation of any long-term threats; and when rising

powers prefer to maintain cooperation that fuels their rise, rather than acting in

ways that raise concerns. The leaders of the established power tend to procrasti-

nate when dealing with long-term threats associated with a rising power, as they

hope to profit from short-term cooperation.92 In this sense, cooperation between

declining and rising powers is more common than we might think, as long as the

process of power shifting is long and incremental. To assure the continuity of

cooperation from established powers, rising powers must avoid acting too assert-

ively and too soon, which is likely to generate balancing and backlash from the

established powers.

Finally, China has moderated its foreign policy behaviour in several respects.93

For instance, it has recently improved its relationship with several neighbouring

countries, including India, Japan and the Philippines.94 Regarding the Sino-

American relationship, China has tried to maintain a stable relationship with the

United States under the Trump presidency.95 Recently, there has been a backlash

against increasing Chinese influence not only in the United States, but also in

Australia, New Zealand, Germany and other western countries.96 In response to

this backlash, there has been some rethinking of and reflection on Chinese foreign

policy. Shi Yinhong has called for the rethinking of a Chinese ‘triumphalism’,

which has been driven by rising nationalism, China’s rising power and domestic

propaganda.97 Supporters of China’s triumphalism advocate that the country

should take a tougher position in disputes about sovereignty and marine inter-

ests. Shi argues that on the contrary China should moderate its positions, and

that it is especially crucial to improve relationships with neighbouring countries.98

According to Peking University Professor Wang Jisi, while some American elites

worry about China’s perception of US decline, their Chinese counterparts are still

91

Edelstein, Over the horizon.

92

Edelstein, Over the horizon.

93

Shi Yinhong, ‘Deng Xiaoping zhihou de zhongguo: tanshuo guocheng zhong de duiwai guojia zhanlue’

[China after Deng Xiaoping: the search process for national foreign strategies], Meiguo yanjiu [Chinese Journal

of American Studies] 32: 3, 2018, pp. 27–8.

94

Shi, ‘Deng Xiaoping zhihou de zhongguo’, pp. 27–8.

95

Shi, ‘Deng Xiaoping zhihou de zhongguo’, p. 28.

96

Joseph S. Nye, Jr, ‘How sharp power threatens soft power’, Foreign Affairs, 24 Jan. 2018, https://www.

foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-01-24/how-sharp-power-threatens-soft-power.

97

Shi, ‘Deng Xiaoping zhihou de zhongguo’, pp. 20–22. Shi also provides a more detailed critique of ‘trium-

phalism’ in one of his earlier articles: see Shi Yinhong, ‘Zhongguo zhoubian xinwei zhong chengyou de

“shenglizhuyi”: dongneng he fuzhaxing’ [The ‘triumphalism’ in China’s neighbouring diplomatic behav-

iours: motivations and complexity], Xiandai guoji guanxi [Modern International Relations], no.10, 2013, pp. 3–5.

98

Shi, ‘Deng Xiaoping zhihou de zhongguo’, pp. 20–22.

1033

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1033 29/08/2018 16:38

Xiaoyu Pu and Chengli Wang

debating whether the US is declining, and no consensus has emerged.99 According

to Renmin University professor Fang Changping, the top elites and many intel-

lectuals in China may still be cautious about their country’s power and status,

while Beijing’s propaganda system may have overemphasized China’s rise.100 In

responding to backlash from the US, Zhong Wei, a professor at Beijing Normal

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

University, has said that the Chinese government should play down the signifi-

cance of the ‘Made in China 2025’ project.101 Recently, the Chinese propaganda

system indeed has somewhat downplayed the theme of China’s rise and America’s

decline.102

As discussed above, we cannot claim that the scholarly debate has fundamen-

tally shaped China’s foreign policy, but there is at least a clear correlation between

the emergence of a cautious voice in the academic world and the adjustment of

Chinese diplomacy in the policy world. While there are important limitations

regarding how the scholarly debate could shape policy, the debate may provide

valuable feedback as policy-makers implement and adjust policy in specific areas.

Conclusion

While most studies on strategic overstretch focus on cases of hegemonic or estab-

lished powers, Chinese scholars have started to debate the question of strategic

overstretch at home in recent years. This continuing debate reveals a high level of

uncertainty over China’s status and role on the global stage.

This debate is a part of China’s grand strategic debate in a wider context, and

has been further shaped by events. The global financial crisis has dramatically

increased China’s profile in global affairs. The election of Donald Trump to the

US presidency has also brought a new element of uncertainty to the international

system, and there are wide expectations that China should play a more active role

on the global stage. Largely abandoning Deng Xiaoping’s low-profile approach,

China has implemented a much more ambitious foreign policy. The BRI has the

potential to transform China’s domestic and foreign policies.

Most Chinese scholars agree that the debate over strategic overstretch is

valuable for China’s foreign policy community. They disagree on the extent to

which China already has such a problem. Some feel that strategic overstretch is

primarily applicable in the context of hegemonic power, empire or established

99

Wang, ‘The view from China’, p. 184.

100

Fang Changping, ‘Meiguo xiangdui shuaitui jiaju zhanlue jinzheng, zhongguo xuzai pinggu zhongmeiguanxi

yi weiyu choumou’ [The relative decline of US intensifies strategic competition, and China must rethink

Sino-American relations], The Paper, 14 March 2018, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2028051.

101

Frank Tang, ‘Is it time Beijing ditched “Made in China 2025” and stopped upsetting the rest of the world?’,

South China Morning Post, 4 June 2018, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/article/2149223/it-time-

beijing-ditched-made-china-2025-and-stopped-upsetting.

102

Tara Francis Chan, ‘China quietly pulled a propaganda film celebrating its tech giants days after the US sanc-

tioned one of them’, Business Insider, 26 April 2018, https://www.businessinsider.nl/us-investigating-huawei-

breaching-iran-sanctions-2018-4/. In a recent commentary in People’s Daily, the CCP’s mouthpiece highlights

the enduring strengths of American hegemonic power, criticizing Trump’s exaggeration of America’s decline.

See ‘Telangpu bianben jiali, shi shihou geita suanqing jibi zhang le’ [Trump becomes relentless and it is time

to reckon the accounts], People’s Daily, 6 April 2018, https://m.21jingji.com/article/20180406/herald/10afdb6a

46551334ec73580decc8245e.html.

1034

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1034 29/08/2018 16:38

Rethinking China’s rise

power, and that for China, as a rising power, the expansion of power and influence

is inevitable: indeed, that by definition a rising power will expand its power and

influence. For an established power or empire, the key question is the scope of

its military presence, and there is real danger of strategic overstretch. For a rising

China, the key danger is not the scope or direction of its expanding influence,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/94/5/1019/5092108 by Bukkyo University Library user on 08 September 2018

but the speed of its rise. In this sense, some Chinese scholars focus the discussion

on the idea of ‘strategic rash advance’ rather than strategic overstretch. There are

many inherent difficulties and uncertainties regarding strategic overstretch. A wise

foreign policy must start from a clear definition of national interest, but China

has different priorities and understanding of its identity, role and national interest.

There are also fundamentally different interpretations of China’s posturing as

defensive or expansive.

While the debate has not yet changed Chinese foreign policy in any fundamental

way, it may reflect the rethinking of Chinese elites on the strategy and tactics of

China’s rise in a new era. In responding to rising backlash and pressure, some

Chinese thinkers are calling for a moderation of Chinese ‘triumphalism’. While

it is hard to prove that the Chinese scholarly debate has fundamentally changed

Beijing’s foreign policy, there is at least a connection between the emergence of a

cautious voice and the moderation of this policy. The scholarly debate may both

reflect the concerns of policy-makers and also provide them with constructive

feedback.

1035

International Affairs 94: 5, 2018

INTA94_5_03_Pu_Wang.indd 1035 29/08/2018 16:38

You might also like

- Robert W. Cox, Production Power and World Order Social Forces in The Making of HistoryDocument10 pagesRobert W. Cox, Production Power and World Order Social Forces in The Making of Historydetoe8125% (4)

- Understanding Hedging in Asia PacificDocument2 pagesUnderstanding Hedging in Asia PacificAkshay RanadeNo ratings yet

- Development and Significance of The Civil Service SystemDocument1 pageDevelopment and Significance of The Civil Service SystemMaribel LimsaNo ratings yet

- Indian Polity M.Laxmikanth Book NotesDocument8 pagesIndian Polity M.Laxmikanth Book Notesbalumahendra 4918No ratings yet

- Schweller, R. (1993) - Tripolarity and The Second World WarDocument32 pagesSchweller, R. (1993) - Tripolarity and The Second World WarFranco VilellaNo ratings yet

- Neorealism and Its CriticismDocument4 pagesNeorealism and Its CriticismTaimur khanNo ratings yet

- Stanley HoffmannDocument11 pagesStanley HoffmannAntohi Andra Madalina Luciana100% (1)

- Alesina, Alberto Et Al. (2010) - Fiscal Adjustments Lessons From Recent HistoryDocument18 pagesAlesina, Alberto Et Al. (2010) - Fiscal Adjustments Lessons From Recent HistoryAnita SchneiderNo ratings yet

- Gilpin - Neorealism and Its CriticsDocument1 pageGilpin - Neorealism and Its CriticsRoyKimNo ratings yet

- Mearsheimer Vs WaltzDocument3 pagesMearsheimer Vs WaltzKelsieNo ratings yet

- Spykman, Nicholas - Frontiers, Security and International Organization (1942)Document13 pagesSpykman, Nicholas - Frontiers, Security and International Organization (1942)Cristóbal BarruetaNo ratings yet

- Xuetong, Yan., (2016) - Political Leadership and Power RedistributionDocument26 pagesXuetong, Yan., (2016) - Political Leadership and Power RedistributionEduardo CrivelliNo ratings yet

- After Victory Ikenberry UP TILL PG 78Document37 pagesAfter Victory Ikenberry UP TILL PG 78Sebastian AndrewsNo ratings yet

- The Return of GeopoliticsDocument7 pagesThe Return of GeopoliticsESMERALDA GORDILLO ARELLANO100% (1)

- Keohane Martin, The Promise of Institution A List TheoryDocument14 pagesKeohane Martin, The Promise of Institution A List TheoryIoana CojanuNo ratings yet

- Keohane Estabilidad HegDocument17 pagesKeohane Estabilidad HegMarcia PérezNo ratings yet

- Abu LughodDocument12 pagesAbu LughodYasser MunifNo ratings yet

- Yan Xuetong On Chinese Realism, The Tsinghua School of International Relations, and The Impossibility of HarmonyDocument9 pagesYan Xuetong On Chinese Realism, The Tsinghua School of International Relations, and The Impossibility of HarmonyWen Yang SongNo ratings yet

- David Kang Getting Asia WrongDocument31 pagesDavid Kang Getting Asia WrongHasna Fadila KumalasariNo ratings yet

- Soft Power by Joseph S NyeDocument19 pagesSoft Power by Joseph S NyemohsinshayanNo ratings yet

- Debates in IR - LiberalismDocument23 pagesDebates in IR - LiberalismAfan AbazovićNo ratings yet

- Has Economic Power Replaced Military Might? Joseph S. NyeDocument3 pagesHas Economic Power Replaced Military Might? Joseph S. NyenalamihNo ratings yet

- Aaron L. Friedberg. 2007. Strengthening U.S. Strategic Planning. The Washington Quarterly (Winter 2007-2008) 311 Pp. 47-60Document14 pagesAaron L. Friedberg. 2007. Strengthening U.S. Strategic Planning. The Washington Quarterly (Winter 2007-2008) 311 Pp. 47-60Wu GuifengNo ratings yet

- Introduction To RealismDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Realismayah sadiehNo ratings yet

- Vietnam's Strategic Hedging Vis-A-Vis China - The Roles of The EU and RUDocument21 pagesVietnam's Strategic Hedging Vis-A-Vis China - The Roles of The EU and RUchristilukNo ratings yet

- Linder and Peters - Instruments of Government 1989 PDFDocument25 pagesLinder and Peters - Instruments of Government 1989 PDFPraise NehumambiNo ratings yet

- Recovering American LeadershipDocument15 pagesRecovering American Leadershipturan24No ratings yet

- The International Operations of National Firms - A Study of Direct Foreign Investment-MIT Press (MA) (Document288 pagesThe International Operations of National Firms - A Study of Direct Foreign Investment-MIT Press (MA) (Bhuwan100% (1)

- Levels of Analysis: - Chapter 3 - PS130 World Politics - Michael R. BaysdellDocument28 pagesLevels of Analysis: - Chapter 3 - PS130 World Politics - Michael R. BaysdellNasrullah AliNo ratings yet

- KAGAN Robert History's BackDocument5 pagesKAGAN Robert History's BackSimona StrimNo ratings yet

- (1992) André Gunder Frank. Nothing New in The East: No New World Order (In: Social Justice, Vol. 19, N° 1, Pp. 34-59)Document26 pages(1992) André Gunder Frank. Nothing New in The East: No New World Order (In: Social Justice, Vol. 19, N° 1, Pp. 34-59)Archivo André Gunder Frank [1929-2005]No ratings yet

- On A. Gunter Frank's Legacy by Cristobal KayDocument8 pagesOn A. Gunter Frank's Legacy by Cristobal KayVassilis TsitsopoulosNo ratings yet

- Kant and The Kantian Paradigm in International Relations (Hurrell) (1990)Document24 pagesKant and The Kantian Paradigm in International Relations (Hurrell) (1990)Madhumita DasNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy of Small States NoteDocument22 pagesForeign Policy of Small States Noteketty gii100% (1)

- An End To The Clash of Fukuyama and Huntington's ThoughtsDocument3 pagesAn End To The Clash of Fukuyama and Huntington's ThoughtsAndhyta Firselly Utami100% (1)

- System Structure and State StrategyDocument56 pagesSystem Structure and State StrategychikidunkNo ratings yet

- Undp-Cb Social Cohesion Guidance - Conceptual Framing and ProgrammingDocument76 pagesUndp-Cb Social Cohesion Guidance - Conceptual Framing and ProgrammingGana EhabNo ratings yet