Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hemangiomas of Infancy

Hemangiomas of Infancy

Uploaded by

nissaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Perianal Abscesses and Fistulas in Infants and ChildrenDocument5 pagesPerianal Abscesses and Fistulas in Infants and ChildrenLorena GarciaNo ratings yet

- Lesley Ann Bergmeier (Eds.) - Oral Mucosa in Health and Disease - A Concise Handbook-Springer International Publishing (2018)Document187 pagesLesley Ann Bergmeier (Eds.) - Oral Mucosa in Health and Disease - A Concise Handbook-Springer International Publishing (2018)Nadira Nurin100% (1)

- Ships Electrical Standards CANADA-Sep2007Document133 pagesShips Electrical Standards CANADA-Sep2007Meleti Meleti MeletiouNo ratings yet

- Familial HemangiomaDocument6 pagesFamilial HemangiomaMiradz 'demmy' MuhidinNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Christine Léauté-Labrèze, John I Harper, Peter H HoegerDocument10 pagesSeminar: Christine Léauté-Labrèze, John I Harper, Peter H HoegerMayaSuyataNo ratings yet

- Infantile Hemangiomas: From Pathogenesis To Clinical FeaturesDocument10 pagesInfantile Hemangiomas: From Pathogenesis To Clinical FeaturesIfadahNo ratings yet

- Vascular Anomalies in Pediatrics 2012 Surgical Clinics of North AmericaDocument32 pagesVascular Anomalies in Pediatrics 2012 Surgical Clinics of North AmericaAntonio TovarNo ratings yet

- Paper PunyaDocument18 pagesPaper PunyaRiefka Ananda ZulfaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1083318821003247 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S1083318821003247 MainMeta ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Infantile HemangiomaDocument25 pagesInfantile Hemangiomaicha_putyNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Infantile HemangiomaDocument47 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Infantile HemangiomaSteph FergusonNo ratings yet

- Hemangiomas An OverviewDocument18 pagesHemangiomas An OverviewRochnald PigaiNo ratings yet

- 8 PDFDocument10 pages8 PDFYusmiatiNo ratings yet

- Overgrowth Syndromes: Andrew C. Edmondson Jennifer M. KalishDocument8 pagesOvergrowth Syndromes: Andrew C. Edmondson Jennifer M. KalishJuan Antonio Herrera LealNo ratings yet

- Pediatric AcneDocument8 pagesPediatric AcneKadir KUCUKNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics 11 00333Document30 pagesDiagnostics 11 00333Nicolás Mosso F.No ratings yet

- Abdominal Masses in Pediatrics - 2015Document5 pagesAbdominal Masses in Pediatrics - 2015Jéssica VazNo ratings yet

- Cervicofacial Vascular Anomalies. I. Hemangiomas and Other Benign Vascular TumorsDocument9 pagesCervicofacial Vascular Anomalies. I. Hemangiomas and Other Benign Vascular TumorsBikash ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Infantile HemangiomaDocument8 pagesInfantile Hemangiomaansar ahmedNo ratings yet

- Infantile Hemangiomas: An Update On Pathogenesis and TherapyDocument12 pagesInfantile Hemangiomas: An Update On Pathogenesis and TherapyNovian Anindito SantosaNo ratings yet

- When To Suspect A Genetic SyndromeDocument8 pagesWhen To Suspect A Genetic Syndromecamila.belloarellanoNo ratings yet

- Kaban 1986Document11 pagesKaban 1986hamdanNo ratings yet

- Ceisler 2004Document9 pagesCeisler 2004SALMA HANINANo ratings yet

- Infantile Hemangioma-Mechanism(s) of Drug Action On A Vascular TumorDocument10 pagesInfantile Hemangioma-Mechanism(s) of Drug Action On A Vascular TumorRaulFranciscoTorresSepulvedaNo ratings yet

- Tumo Wilms 6Document2 pagesTumo Wilms 6Isabela Rebellon MartinezNo ratings yet

- Hemangioma of InfancyDocument7 pagesHemangioma of InfancyAdi Bachtiar TambahNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations: Current Theory and ManagementDocument11 pagesReview Article: Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations: Current Theory and ManagementDewi AngrianaNo ratings yet

- Infantile Hemangiomas: A Review: Pediatric Ophthalmology UpdateDocument9 pagesInfantile Hemangiomas: A Review: Pediatric Ophthalmology UpdateYipno Wanhar El MawardiNo ratings yet

- Update On Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma: ReviewDocument4 pagesUpdate On Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma: ReviewPhn StanleyNo ratings yet

- 104 FullDocument5 pages104 FullSamNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0738081X14002375 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0738081X14002375 Mainmarisa araujoNo ratings yet

- Hafiizh Dwi Pramudito, Dr. Dr. Agung Prasmono, SP.B-TKV (K) : AdvisorDocument29 pagesHafiizh Dwi Pramudito, Dr. Dr. Agung Prasmono, SP.B-TKV (K) : AdvisorhafiizhdpNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2013 Chen 99 108Document12 pagesPediatrics 2013 Chen 99 108Johannus Susanto WibisonoNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1751722217302172Document4 pagesPi Is 1751722217302172Louis WakumNo ratings yet

- Neoplasias SebaceasDocument25 pagesNeoplasias SebaceasKAREN ROCIO LATORRE RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- 8 Diseases of Infancy and ChildhoodDocument23 pages8 Diseases of Infancy and ChildhoodBalaji DNo ratings yet

- Birthmarks Identificationandmx201205ryanDocument4 pagesBirthmarks Identificationandmx201205ryanDanielcc LeeNo ratings yet

- Non-Immune Fetal Hydrops: Are We Doing The Appropriate Tests Each Time?Document3 pagesNon-Immune Fetal Hydrops: Are We Doing The Appropriate Tests Each Time?dian_067No ratings yet

- Pediatric Neck Masses: William J. Curtis, DMD, MD, Sean P. Edwards, DDS, MDDocument6 pagesPediatric Neck Masses: William J. Curtis, DMD, MD, Sean P. Edwards, DDS, MDMashood AhmedNo ratings yet

- Management Vascular MalformationDocument18 pagesManagement Vascular MalformationRini RahmawulandariNo ratings yet

- Prader Willi Syndrome AAFP PDFDocument4 pagesPrader Willi Syndrome AAFP PDFflower21No ratings yet

- 55 Cardiac TumorsDocument8 pages55 Cardiac TumorsVictor PazNo ratings yet

- Frequencies of Congenital Anomalies Among Newborns Admitted in Nursery of Ayub Teaching Hospital Abbottabad, PakistanDocument5 pagesFrequencies of Congenital Anomalies Among Newborns Admitted in Nursery of Ayub Teaching Hospital Abbottabad, PakistanSaad GillaniNo ratings yet

- TTTS NeoreviewsDocument13 pagesTTTS NeoreviewsNeha OberoiNo ratings yet

- Dermatology and Dermatologic DiseasesDocument4 pagesDermatology and Dermatologic DiseasesM TarmiziNo ratings yet

- CapilarDocument1 pageCapilarAndreea AncaNo ratings yet

- Cornejo 2019 Sex Cord Stromal Tumors of The TestDocument10 pagesCornejo 2019 Sex Cord Stromal Tumors of The TestfelipeNo ratings yet

- Abnomal Uterine Bleeding in Premenopausal Women AAFPDocument9 pagesAbnomal Uterine Bleeding in Premenopausal Women AAFPAliNasrallahNo ratings yet

- Guia - S Down IDocument6 pagesGuia - S Down IVeronica EncaladaNo ratings yet

- Grand Rounds KASABACH MERRIT SYNDROMEDocument92 pagesGrand Rounds KASABACH MERRIT SYNDROMEJohanna LomuljoNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Genetic SyndromesDocument11 pagesNeonatal Genetic SyndromesNoel Saúl Argüello SánchezNo ratings yet

- Haemophilia: For Carrier and Diagnosis : Strategies Detection PrenatalDocument30 pagesHaemophilia: For Carrier and Diagnosis : Strategies Detection PrenatalAnh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument25 pagesAcute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaJavierNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document10 pagesJurnal 2lomba Panah Dies UnsriNo ratings yet

- Medip, IJCP-1422 CDocument3 pagesMedip, IJCP-1422 CdsagemaverickNo ratings yet

- Phimosis 5 PDFDocument4 pagesPhimosis 5 PDFNurul YaqinNo ratings yet

- Leukaemias: A Review: Aetiology and PathogenesisDocument6 pagesLeukaemias: A Review: Aetiology and PathogenesisCiro Kenidy Ascanoa PorrasNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics in Review 2006 Sugar 213 23Document13 pagesPediatrics in Review 2006 Sugar 213 23Berry BancinNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Vulvovaginal Disorders: A Diagnostic Approach and Review of The LiteratureDocument13 pagesPediatric Vulvovaginal Disorders: A Diagnostic Approach and Review of The LiteratureBeatrice Joy TombocNo ratings yet

- Vascular Limb Occlusion in Twin To Twin Tranfusion SyndromeDocument10 pagesVascular Limb Occlusion in Twin To Twin Tranfusion Syndromejhon heriansyahNo ratings yet

- Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Hydrops FoetalisDocument10 pagesAetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Hydrops FoetalisMargareta OktavianiNo ratings yet

- Benign Hematologic Disorders in Children: A Clinical GuideFrom EverandBenign Hematologic Disorders in Children: A Clinical GuideDeepak M. KamatNo ratings yet

- Giant PandaDocument6 pagesGiant PandaJasvinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Finger Sprain: Active Finger Flexion ExercisesDocument7 pagesFinger Sprain: Active Finger Flexion ExercisesTJPlayzNo ratings yet

- Ryan Fitzgerald Resume Feb 2021Document2 pagesRyan Fitzgerald Resume Feb 2021api-547397529No ratings yet

- Parental Satisfaction (Parents of Children 0-17, Elementary-High School) - 0Document4 pagesParental Satisfaction (Parents of Children 0-17, Elementary-High School) - 0Sergio Alejandro Blanes CàceresNo ratings yet

- Enabling Health and Healthcare Through IctDocument416 pagesEnabling Health and Healthcare Through Ictarif candrautamaNo ratings yet

- Penyakit Paru Akibat KerjaDocument59 pagesPenyakit Paru Akibat Kerjanurliah armandNo ratings yet

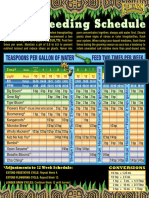

- Fox FarmDocument1 pageFox Farmjohnny chauNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Sodium-Glucose CotransportDocument12 pagesHHS Public Access: Sodium-Glucose CotransportAlexandra VásquezNo ratings yet

- RPD Daily Incident Report 1/5/23Document5 pagesRPD Daily Incident Report 1/5/23inforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Coastal Mitigation and Adaptation MeasuresDocument5 pagesCoastal Mitigation and Adaptation Measuresjames kaririNo ratings yet

- Model Answer Sheet: Multistored Cropping 11% 0.002mm CAMDocument11 pagesModel Answer Sheet: Multistored Cropping 11% 0.002mm CAMSonam RanaNo ratings yet

- US Internal Revenue Service: Irb07-39Document72 pagesUS Internal Revenue Service: Irb07-39IRSNo ratings yet

- Broken BeautyDocument143 pagesBroken BeautyAngelica MakAngelNo ratings yet

- 1echocardiography and The NeonatologistDocument4 pages1echocardiography and The NeonatologistAbuAlezzAhmedNo ratings yet

- Filipendula Ulmaria BrochureDocument3 pagesFilipendula Ulmaria BrochureMamta maheshwariNo ratings yet

- PDF TextDocument5 pagesPDF TextPihooNo ratings yet

- Methodology For Puff Test at Descharge Pressure.Document4 pagesMethodology For Puff Test at Descharge Pressure.kazmi naqashNo ratings yet

- Outline of Indian Labour MarketDocument11 pagesOutline of Indian Labour MarketAnurag JayswalNo ratings yet

- Pitting Corrosion Rate - FlatDocument1 pagePitting Corrosion Rate - Flatja23gonzNo ratings yet

- Decreased Pulmonary Blood Flow (CYANOTIC HEART DEFECTS)Document88 pagesDecreased Pulmonary Blood Flow (CYANOTIC HEART DEFECTS)leenaNo ratings yet

- Myx Menu (New)Document16 pagesMyx Menu (New)G Sathesh KumarNo ratings yet

- ENERCON Super Seal JR Cap SealerDocument26 pagesENERCON Super Seal JR Cap SealerEdgar MárquezNo ratings yet

- Premature BurialDocument9 pagesPremature Burialaidee bogadoNo ratings yet

- Maintenance PKSDocument63 pagesMaintenance PKSBunga PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- Electrical Conduits & Fittings: Protect Electrical Cables and WiresDocument18 pagesElectrical Conduits & Fittings: Protect Electrical Cables and WiresA Ma RaahNo ratings yet

- Commissioning Tests For HV Underground Cables (Up To 33Kv) SWPDocument13 pagesCommissioning Tests For HV Underground Cables (Up To 33Kv) SWPCharles Robiansyah100% (1)

- BST Gen Cns Mos Aip 10003 10003 00 Pin Brazing Method StatementDocument42 pagesBST Gen Cns Mos Aip 10003 10003 00 Pin Brazing Method StatementRao DharmaNo ratings yet

- Full Download Test Bank For Sectional Anatomy For Imaging Professionals 3rd Edition Kelley PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Sectional Anatomy For Imaging Professionals 3rd Edition Kelley PDF Full Chapterflotageepigee.bp50100% (30)

Hemangiomas of Infancy

Hemangiomas of Infancy

Uploaded by

nissaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hemangiomas of Infancy

Hemangiomas of Infancy

Uploaded by

nissaCopyright:

Available Formats

Hemangiomas of Infancy: Clinical and

Biological Characteristics

Kara N. Smolinski, MD, PhD

Albert C. Yan, MD

Summary: Hemangiomas of infancy are common in the general pediatric population, are usually

easily diagnosed, and generally do not require treatment. However, a small but significant

percentage of hemangiomas of infancy may develop complications, including infection or

ulceration. In addition, hemangiomas located in some anatomic regions may be associated with

other anomalies and therefore require more careful monitoring and earlier intervention to

prevent permanent sequelae. This review focuses on distinguishing hemangiomas from vascular

malformations and delineates the natural history of hemangiomas of infancy, with an emphasis on

identifying those hemangiomas that require additional evaluation and closer follow-up. Current

treatment modalities, including the use of systemic steroids and the pulsed-dye laser, are discussed.

In addition, several conditions that often present with cutaneous hemangiomas are described,

including PHACES syndrome and neonatal hemangiomatosis. Finally, an assessment is made of the

current understanding of the biology of hemangioma proliferation and involution, including

the role of endothelial growth factors and GLUT1, a new marker for hemangiomas of infancy.

Clin Pediatr. 2005;44:747-766

Introduction fants and children. They are pre- African-American, Hispanic, or

sent in approximately 2% to 3% Asian descent. They are also more

H emangiomas are benign

congenital vascular neo-

plasms composed of vas-

cular endothelial cells that have

the capacity for excessive prolifer-

of neonates and in 10% of all in-

fants by 12 months of age.1-4 For

reasons that are not clear, heman-

giomas are approximately 3 times

more common in female infants

common in premature infants,

and are seen in approximately

20% of premature infants with a

birth weight of less than 1000 g.5,6

There are also reports of families

ation and represent one of the and are also more common in in whom the development of he-

most common birthmarks in in- white infants than in those of mangiomas appears to be inher-

ited as an autosomal dominant

trait.7

Classification

Section of Pediatric Dermatology, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Historically, the nomenclature

of hemangiomas and other vascu-

Reprint requests and correspondence to: Albert C. Yan, MD, Director, Pediatric Dermatology, lar birthmarks has been confus-

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 34th and Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

ing. Currently, the classification

© 2005 Westminster Publications, Inc., 708 Glen Cove Avenue, Glen Head, NY 11545, U.S.A. system devised by Mulliken and

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 747

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

Glowacki and recently refined in

1997 by the International Society Table 1

for the Study of Vascular Anom-

alies provides the best framework

for understanding vascular anom- COMPARISONS OF HEMANGIOMAS OF INFANCY

alies in infants and children. 8,9 VS. VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

Hemangiomas are more properly

classified as vascular tumors com- Vascular Malformations

posed of hyperplastic vascular en- Hemangiomas of Infancy (capillary, venous, lymphatic, mixed)

dothelial cells that have the ca-

Endothelial cell hyperplasia Hamartoma of normal endothelial cells

pacity for excessive proliferation

but normally undergo eventual Spontaneous involution Do not involute

regression and involution. This is Present during early infancy Present at birth

in contradistinction to vascular

malformations, which are hamar-

tomas of mature endothelial cells

(Table 1). Vascular malformations

result from structural abnormali- tissue with little involvement of oration with softening and flat-

ties of endothelial cells that are the overlying skin. They appear as tening of the hemangioma is ob-

usually present at birth, are rela- compressible, rubbery, poorly-de- served as the blood vessels invo-

tively mature at presentation, and fined bluish nodules and may lute and f ibrosis and fatty

do not exhibit a tendency to- demonstrate visible draining su- infiltration occurs. Involution

wards hyperplasia with rapid pro- perficial veins. Mixed heman- proceeds slowly over many years,

liferation; rather, they display a giomas contain both superficial with approximately 50% of he-

normal pattern of growth and and deep components. mangiomas having reached the

only enlarge proportionally as Most hemangiomas are not point of maximal involution by

the child grows. Furthermore, identified at birth, but often a age 5 years and 90% having

they do not spontaneously re- precursor lesion that appears as a reached maximal regression by 9

solve. Clinically, the distinction pale bluish-grey macule or a small years of age, although in some

between a port wine stain and he- cluster of telangiectasias may be children involution may be com-

mangioma of infancy is usually visible. They are most commonly plete by 2 or 3 years of age.10-12

straightforward but may be diffi- located on the head and neck The majority of hemangiomas will

cult during the first few weeks of (60%), followed by the trunk involute with minimal or no

life until the natural history of (25%), and the extremities residua; however, an estimated

the lesion declares itself. (15%).10 Most hemangiomas be- 20–50% will leave areas of scar-

come clinically evident within the ring, residual fibrofatty tissue, at-

Natural History first few weeks to months of life as rophy, hypopigmentation, or

On clinical examination, he- a result of extensive proliferation residual telangiectasias, which

mangiomas may display a super- of vascular endothelial cells. The may be visibly conspicuous (Fig-

ficial component, a deep com- growth rate of hemangiomas is ure 1).13,14 Patients with suspected

ponent, or both. Super f icial highest during the first 3 to 6 congenital hemangiomas which

hemangiomas are composed of months of life during the prolifer- are atypical in appearance or that

collections of telangiectatic mac- ative phase. The growth rate then do not follow the expected clini-

ules and papules located in the su- begins to slow between ages 6 to 9 cal course should be referred to a

perficial dermis that form raised, months of life, and by 12 months pediatric dermatologist for evalu-

well-def ined, non-blanchable of age most hemangiomas have ation, as there are a number of

plaques. A surrounding zone of reached their maximal size. Be- rare malignant vascular tumors of

pallor may be appreciated during ginning at approximately 12 to 18 infancy that may mimic the ap-

the active proliferative phase. months of age, hemangiomas en- pearance of an infantile heman-

Deep hemangiomas, in contrast, ter a gradual regression or involu- gioma, including Kaposiform he-

consist of collections of dilated tional phase. During the involu- mangioendothelioma, tufted

vascular channels located in the tional phase, the development of angioma, and infantile fibrosar-

deeper dermis and subcutaneous a super f icial, grayish discol- coma. In these cases, skin biopsy,

748 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

orbits are an ophthalmologic

emergency, because they may

compromise the developing vi-

sual system and cause a range of

sequelae, including refractive er-

rors, astigmatism, strabismus, pto-

sis, and stimulus deprivation am-

blyopia if untreated (Figure

2).15,16 Referral for urgent oph-

thalmologic evaluation may be

necessary to preserve vision and is

mandatory if the hemangioma is

rapidly growing or if there is a risk

of obstructing the visual fields or

compressing vital introrbital

str uctures. Per manent visual

deficits may result from a period

Figure 1. Involuting hemangioma with residual telangiectasias. of ocular compromise as short as

2 weeks. Inter ventions include

patching of the unaffected eye,

use of topical constrictive drops to

magnetic resonance imaging, and meticulous attention to wound the unaffected eye, systemic or in-

angiography will aid in the cor- care and may benefit from addi- tralesional steroids, and surgical

rect diagnosis, and prompt refer- tional therapies, including use of debulking of the affected eye.17

ral to addditional pediatric sub- the pulsed dye laser.

specialists, including pediatric Pelvic and Perineal

surgery and pediatric oncology, Periorbital Hemangiomas Hemangiomas

may be facilitated. Rapidly growing heman- Rarely, pelvic and perineal he-

giomas that are located near the mangiomas are associated with

Special Circumstances

Table 2

Hemangiomas of infancy that

are present in certain locations

may be associated with other WHEN TO WORRY: LOCATION AND HEMANGIOMA RISK

anomalies or may have an in-

creased risk of developing partic- Location Complication Risk

ular complications (Table 2).

Most complications arise during Beard distribution Laryngeal or subglottic hemangioma and risk

the proliferative phase of growth, of stridor, obstruction, respiratory failure

and prompt recognition and in- Anogenital, oropharynx, lip Ulceration, infection, scarring

tervention may be required in or-

Cervicofacial PHACES syndrome

der to prevent permanent seque-

lae. Hemangiomas that are Midline lumbosacral Spinal dysraphism, tethered cord

present in the following areas are Periorbital Strabismus, amblyopia, astigmatism

of particular concern and require

Nose, lip, parotid Poor spontaneous involution, scarring

closer follow-up, additional evalu-

ation, specialized therapy, or re- Multiple cutaneous Visceral hemangiomas (most commonly liver,

ferral to pediatric subspecialists gastrointestinal tract, lung, brain and

for further management: perior- meninges)

bital, pelvic and perineal, lum- Hepatic and large

bosacral, and facial. In addition, cutaneous hemangiomas Thyroid dysfunction

ulcerated hemangiomas require

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 749

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

urogenital and anorectal anom-

alies such as hypospadias, anterior

or vestibular anus, imperforate

anus, and atrophy or absence of

the labia minora.18 Perineal he-

mangiomas are prone to ulcera-

tion and infection as a result of

frictional and chemical trauma

(Figure 3).

Lumbosacral Hemangiomas

A definite correlation exists

Figure 2. Periorbital hemangioma. Hemangiomas in this location may compress the globe between lumbosacral heman-

or cause obstruction of the visual field, impairing the developing visual system. giomas and underlying spinal

anomalies, including occult spinal

dysraphism, tethered spinal cord,

and lipomeningomyelocele (Fig-

ure 4). A thorough neurologic ex-

amination and spinal imaging by

ultrasound (appropriate in very

young infants) or magnetic reso-

nance imaging (MRI) (for older

infants or children) is recom-

mended for all infants with a he-

mangioma overlying the midline

lumbosacral region.19-22 The inci-

dence of occult spinal dysraphism

was 17.5% in one large case series

involving 120 patients with a su-

perficial hemangioma even with-

out other stigmata overlying the

Figure 3. Perineal heman-

midline lumbosacral area. 23

gioma. Hemangiomas in this

Prompt neurosurgical consulta-

location are prone to ulcera-

tion is indicated for any infant

tion and infection.

with a clincally abnormal neuro-

logic examination with an accom-

panying midline lumbosacral he-

mangioma. In addition, close

neurologic follow-up is important,

because some infants who do not

manifest any initial neurologic

deficits will later develop perma-

nent neurologic sequelae that

may have been prevented by early

surgical intervention.

Facial Hemangiomas

The head and neck is the most

common location for heman-

giomas of infancy, accounting for

60% in one large series.10 Specific

Figure 4. Partially involuted lumbosacral hemangioma. Hemangiomas involving the lum- areas of concern on the face in-

bosacral area are associated with underlying spinal cord anomalies, including tethered cord. clude the preauricular area, the

750 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

parotid, the nasal tip, the lips and

orophayrnx, and the ears. In gen-

eral, hemangiomas involving the

lips and orophar ynx, the nasal

tip, and ears may incompletely in-

volute and may require surgical

intevention to minimize residual

scarring and deformity (Figures

5, 6). Preauricular hemangiomas

may be associated with heman-

giomas involving the parotid, but

do not usually compromise the fa-

cial nerve. Parotid hemangiomas

are rarely associated with conduc-

tive hearing loss and bony distor-

tion of the mandible and tend to

heal slowly and with scarring.

Figure 5. Nasal tip hemangioma. Hemangiomas involving the nose often leave residual

Rarely, hemangiomas that ob-

scarring and deformity after involution.

struct the external auditory canal

may result in hearing loss if per-

sistent and bilateral.

Recently, facial hemangiomas

have been further charcterized

based on their growth pattern

and on their anatomic location

as related to structural and devel-

opmental landmarks.24 The ma-

jority of hemangiomas, over

76%, are characterized as focal

lesions, which are localized and

tumorlike and appear to segre-

gate along putative lines of em-

bryonic fusion of the primitive

mesenchyme and ectoder m

that form the developing head

and neck str uctures. The re-

maining hemangiomas have a

Figure 6. Hemangioma involving the lower lip. Hemangiomas involving the beard distrib-

more diffuse, plate-like appear-

ution, which includes the preauricular area, the lower lip, and the chin, are associated with

ance and appear to localize to

laryngeal and subglottic hemangiomas.

more segmental distributions

within the frontonasal, maxillary,

or mandibular facial areas, al- giomas, most commonly involv- Hemangiomas located on the

though not correlating exactly ing the liver, gastrointestinal face in the beard distribution

with the dermatomal distrubu- tract, and brain.25 A significant (preauricular, chin, lower lip, an-

tion of the branches of the number of infants with facial seg- terior neck) raise concern due to

trigeminal nerve. Diffuse facial mental hemangiomas in associa- an association with laryngeal or

hemangiomas are more likely to tion with visceral hemangiomato- subglottic hemangiomas that may

be associated with complications, sis meet criteria for PHACES rapidly compromise the air way

including ulceration. Recent re- syndrome (posterior fossa abnor- during the proliferative growth

ports suggest that facial segmen- mality, hemangioma, arterial phase (Figure 6).26,27 Laryngeal

tal hemangiomas are also associ- anomaly, cardiac defects, coarc- and subglottic hemangiomas may

ated with an increased incidence tation of the aorta, eye/ocular cause stridor, persistent cough,

of associated visceral heman- abnormality, sternal defect).25 hoarseness, respiratory distress,

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 751

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

or cyanosis, and many infants will

present with respirator y symp-

toms between 6 to 12 weeks of life.

Evaluation by imaging with lateral

neck radiographs, MRI scan, or di-

rect laryngoscopic visualization

will aid in defining the extent of in-

volvement. In infants with exten-

sive involvement, tracheostomy

may be required if local measures,

which include corticosteroids, irra-

diation, surgical excision, and

laser ablation, fail to adequately

control the airway.28-32

Ulcerated Hemangiomas Figure 7. Ulcerated hemangioma.

Genital and orophar yngeal

hemangiomas are particularly sus-

ceptible to ulceration and infec-

tion as a result of chronic irrita-

tion (Figures 7, 8). Common

organisms isolated from infected

hemangiomas include Staphylo-

coccus aureus, group A beta-

hemolytic streptococci, and

Enterobacteriaceae, although

anaerobic and mixed infections

are also seen frequently.33 Treat-

ment of ulcerated hemangiomas

includes meticulous attention to

wound care, with gentle cleans-

ing, application of topical antibi-

otics and the use of barrier oint-

ments such as zinc oxide and

occlusive dressings such as Duo-

Derm or petroleum gauze. The

use of superabsorbent diapers, as

well as frequent diaper changes to

minimize exposure to irritants, is

an important adjunct to therapy.

To minimize the risk of infection, Figure 8. Ulcerated perineal hemangioma.

topical mupirocin ointment is

recommended for ulcerated he- form of recombinant human mon in ulcerated hemangiomas

mangiomas involving the lips or platelt-derived growth factor that is or those involving the scalp, and

oropharynx, while topical metro- currently approved for use in the can usually be easily controlled

nidazole gel is efficacious for ul- treatment of diabetic ulcers, has with pressure and occasional use

cerated anogenital heman- shown potential in the treatment of of gel-foam. Adequate pain con-

giomas.34 Systemic antibiotics are ulcerated hemangiomas that are trol is an important component of

indicated in any child with an ul- refractory to standard therapy.35 treatment as ulcerated heman-

cerated hemangioma that shows Despite the fears of many par- giomas can be quite painful, with

signs of wound infection, such as ents, hemangiomas rarely cause infants often manifesting irritabil-

fever or cellulitis. Recently, the significant or life-threatening ity, behavioral changes, and sleep

use of becaplermin gel, a topical bleeding. Bleeding is more com- disturbances. Administration of

752 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

oral analgesics is often required, type of these congenital heman- mations (including Dandy-Walker

and may include acetaminophen giomas is the rapidly involuting malformation, cerebellar atrophy,

or codeine products. Topical congenital hemangioma (RICH); agenesis of the corpus callosum),

agents, such as 2.5% lidocaine the second type is the noninvolut- hemangiomas, arterial anomalies

ointment, can provide prompt ing congenital hemangioma (persistent embryonic intra- and

pain relief when used judiciously; (NICH). Another condition of extracranial arteries, aneurysmal

however, prolonged use of topical special interest, although not as- dilatations and anomalous

anesthetics which contain prilo- sociated with benign heman- branches of the internal carotid

caine, such as EMLA, is not rec- giomas of infancy, is Kasabach- artery, and absence of ipsilateral

ommended due to the risk of Merritt phenomenon, which is a carotid or cerebral vessels have

methemoglobinemia. potentially fatal complication of been reported), cardiac defects

Ulcerated hemangiomas heal other vascular tumors, in particu- and coarctation of the aorta (in-

more slowly that those that have lar Kaposifor m hemangioen- cluding patent ductus arteriosis

not ulcerated and are more likely dothelioma and tufted angioma. and ventricular septal defects), eye

to heal with scarring. Pulsed dye abnormalities (including microph-

laser treatments have been shown PHACES Syndrome thalmia, congenital cataracts,

to be of benefit in treating ulcer- The presence of a large, glaucoma, and optic ner ve hy-

ated hemangiomas by hastening plaque-like segmental cervicofa- poplasia), and midline sternal

healing and reducing pain; how- cial hemangioma is one defining malformations (most commonly

ever, the laser may also cause ulcer- component of PHACES syn- supraumbilical raphae and ster-

ation, scarring, and hypopigmenta- drome (Figure 9). This multisys- nal clefts) (Table 3).39-41

tion. 34,36-38 On rare occasions, temic constellation of associations A review of cases reported in

surgical excision may be required includes posterior fossa malfor- the literature reveals that the ma-

for ulcerated hemangiomas that

have not responded to more con-

servative wound care, topical and

systemic antibiotic administration,

or pulsed dye laser therapy.

Special Circumstances

Certain presentations of he-

mangiomas of infancy are indica-

tors of possible systemic or syn-

dromic manifestations. Although

rare, clinicians should be aware of

these associations in order to as-

sure prompt recognition and

evaluation. Two well-defined con-

ditions associated with heman-

giomas of infancy are PHACES

syndrome, one component of

which is a large facial segmental

hemangioma, and neonatal he-

mangiomatosis, in which multiple

small focal hemangiomas are pre-

sent, usually distributed diffusely.

There are also two rare presenta-

tions of hemangiomas that are

present at birth and do not ex-

hibit the typical growth pattern of Figure 9. Large facial segmental hemangioma in PHACES

hemangiomas of infancy. One syndrome.

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 753

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

Table 3

PHACES CRITERIA

Criterion Examples

P—posterior fossa abnormality Dandy-Walker malformation, agenesis of the corpus callosum,

cerebellar atrophy

H—hemangioma Cervicofacial location

A—arterial anomaly Aneurysms and anomalies of internal carotid arteries

C—cardiac defects, coarctation of the aorta Coarctation of the aorta, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus

E—eye/ocular abnormality Cataracts, microphthalmia, optic nerve hypoplasia, glaucoma

S—sternal defect Supraumbilical raphae, sternal cleft

jority of affected patients (70%) prior to surgical repair in any in- neonatal hemangiomatosis (Fig-

possess only one extracutaneous fant with PHACES syndrome and ure 10). In general, these heman-

manifestation in addition to the an aortic anomaly.42 giomas are benign and involute

cervicofacial hemangioma; how- The association of large cervi- within the first 2 years of life.43-47

ever, reported cases are found pre- cofacial hemangiomas with other However, multiple, progressive,

dominantly in the dermatology lit- significant comorbidities indi- rapidly growing cutaneous he-

erature and are therefore biased cates that any infant who presents mangiomas may be associated

towards the recognition of the fa- with a cervicofacial hemangioma with widespread visceral heman-

cial hemangioma as a defining should be considered at risk for giomas in the liver, lungs, gas-

characteristic of the syndrome. PHACES syndrome. They should trointestinal tract, brain and

The most common reported ex- undergo careful neurologic meninges. This presentation, re-

tracutaneous manifestation in in- evaluation and should be re- ferred to as diffuse neonatal he-

fants with PHACES syndrome is ferred for ophthalmologic evalu- mangiomatosis, carries the risk of

structural and arterial brain mal- ation, brain MRI/magnetic reso- systemic complications, including

formations, which are present in nance angiography (MRA), and high-output cardiac failure, hem-

71% of affected infants.40 These cardiac evaluation. In addition, orrhage, and neurologic defects,

anomalies place infants at high cervicofacial hemangiomas in the with an attendent high mortality

risk for neurologic sequelae, in- beard distribution are also associ- rate (Table 4).48-52

cluding developmental delay and ated with laryngeal and subglottic Infants who present with mul-

seizures. Congenital heart disease hemangiomas, and infants with tiple cutaneous hemangiomas

was reported in over one-third of hemangiomas in this location should be evaluated for the in-

cases reported in the literature should also be monitored care- volvement of other organ systems

and in 21% of cases in one small fully for respiratory distress with with close follow-up. An abdomi-

case series.40 One recent case se- otolar yngologic consultation nal ultrasound with Doppler is

ries of infants with PHACES syn- where appropriate. recommended in all symptomatic

drome and aortic arch anomalies infants presenting with multiple

demonstrated that there appears Neonatal Hemangiomatosis hemangiomas. Hepatic involve-

to be a strong correlation be- Hemangiomas usually occur ment represents the most com-

tween the laterality of the facial as isolated lesions. Multiple scat- mon site of extracutaneous dis-

hemangioma and the underlying tered, small, dome-shaped he- ease and greatest cause of

cerebrovascular and aortic arch mangiomas that present at birth morbidity and mortality in infants

anomalies, leading the authors to or during the first few weeks of with systemic involvement. He-

suggest vascular imaging studies life are referred to as benign patic hemangiomas commonly

754 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

complete blood cell counts, an

ophthalmologic examination,

urinalysis, and stool guaiacs. Of

note, the development of hy-

pothyroidism as a result of in-

creased type 3 iodothyronine

deiodinase activity has been re-

ported among infants with he-

patic hemangiomas.53

Congenital Hemangiomas

Rarely, fully developed vascu-

lar tumors that clinically resemble

hemangiomas may present at

birth. These congenital heman-

giomas are believed to result from

the in utero development of he-

Figure 10. Neonatal hemangiomatosis. The presence of multiple hemangiomas may be mangiomas with a proliferative

associated with internal hemangiomas involving the gastrointestinal tract, the lungs, and phase. They differ clinically from

the central nervous system. common hemangiomas of infancy

in appearance, natural history, and

biologic origins. They present at

Table 4 birth as raised violaceous-grey tu-

mors with overlying telangiectasias

and a peripheral rim of pallor, and

BENIGN NEONATAL HEMANGIOMATOSIS VS are often quite large, averaging sev-

DIFFUSE NEONATAL HEMANGIOMATOSIS eral centimeters in diameter (Fig-

ure 11). They may also demon-

Benign Neonatal Diffuse Neonatal strate warmth and a palpable bruit

Hemangiomatosis Hemangiomatosis as the result of high-flow vascula-

ture. Some of these hemangiomas

Multiple cutaneous hemangiomas Yes Yes will begin to involute early in in-

Systemic involvement Infrequent Yes fancy and will have regressed com-

pletely by 12 to 18 months of age.

Requires therapy No Yes

These rapidly involuting congeni-

Requires close follow-up Yes Yes tal hemangiomas (RICH) require

Prognosis Excellent Poor no intervention unless complica-

tions occur.54-56 Histopathologic

evaluation demonstrates capillary

lobules in a dense, fibrotic stroma

present within the f irst few temic complications and who fail with focal thrombosis and sclerosis

months of life with hepatomegaly, to respond to systemic steroids. of capillary lobules and associated

congestive heart failure, and ane- Interferon-alpha, vincristine, he- thin-walled vessels in the absence

mia as a result of a large arteri- patic arter y embolization, and of normal tissue elements.54 On

ovenous shunt and high-output partial hepatectomy have all been angiography, RICH demonstrate

cardiac failure. Early consultation used with variable success. Fre- proliferating vascular lobules

with a pediatric cardiologist and quent monitoring of infants at composed of proliferating capil-

initiation of systemic corticos- risk for diffuse neonatal heman- laries and thin-walled vessels set

teroids is essential in infants with giomatosis to evaluate for involve- in a fibrous stroma; large, irregu-

hepatic involvement and conges- ment of other organ systems lar, disorganized feeding arteries

tive heart failure. More aggressive should include a thorough physi- with arterial aneurysms; arteri-

therapy may be indicated for in- cal examination as well as tar- ovenous shuts; and intravascular

fants who have developed sys- geted screening tests, including thrombi.54,57

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 755

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

RICH and NICH lesions are

distinct clinical entities and differ

from hemangiomas of infancy in

their various surface markers as

well as in their histology. Neither

RICH nor NICH express GLUT1,

a vascular marker for heman-

giomas of infancy. 54,58 The ap-

pearance of RICH and NICH on

MRI and ultrasound also show dis-

tinctive patterns, and can help to

differentiate these atypical vascu-

lar tumors from benign heman-

giomas of infancy. Rarely, chil-

dren may present with a RICH or

a NICH in association with a he-

mangioma of infancy, or may pre-

Figure 11. Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma. sent with a lesion initially diag-

nosed as a RICH that fails to

undergo complete involution and

persists as a lesion more compati-

ble with a NICH.59 Clearly, our un-

derstanding of the biology of he-

mangiomas remains incomplete

and continues to evolve.

Kasabach-Merritt Phenomenon

Kasabach-Merritt phenome-

non indicates a consumptive coag-

ulopathy that manifests as severe

thrombocytopenia, hemolytic

anemia, and disseminated in-

travascular coagulation occuring

in the setting of a rapidly growing

vascular tumor (Table 5). Despite

prior reports in the literature, he-

mangiomas of infancy are not as-

Figure 12. Noninvoluting congenital hemangioma.

sociated with Kasabach-Merritt

phenomenon.60-64 Large venous

or mixed vascular malformations

may rarely be associated with a

In contrast, some congenital found most frequently on the consumptive coagulopathy that is

hemangiomas do not involute but head and neck. On Doppler ultra- milder than that seen with

continue to proliferate. These sound, NICH demonstrate persis- Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon;

noninvoluting congenital heman- tant fast arterial flow. Histopatho- significant coagulopathy is not as-

giomas (NICH) also manifest as logic examination shows small, sociated with hemangiomas of in-

purplish nodules and plaques thin-walled vessels arranged into fancy. Kasabach-Merritt phenom-

with overlying telangiectasias and lobules with dilated, dysplastic in- enon has been associated

central or peripheral pallor, and terlobular veins and small arteries primarily with Kaposiform he-

may also demonstrate palpable that shunt into lobular vessels.58 mangioendotheliomas, but has

warmth and a bruit (Figure 12).58 NICH are treated with surgical ex- also been reported to occur with

They have been reported more cision and exhibit no tendency to tufted angiomas, congenital he-

commonly in males and are recurrence. mangiopericytomas, and certain

756 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

recommended during early in-

Table 5 fancy, when the rapid growth

phase predominates. When the

growth rate slows and the heman-

KASABACH-MERRITT PHENOMENON gioma is stable in size, less fre-

quent monitoring is necessar y

Associated vascular malformations Kaposiform hemangioepithelioma, tufted and annual evaluations are usu-

angioma, congenital hemangiopericytoma, ally sufficient for involuting he-

lymphatic malformations mangiomas, unless families re-

Hematologic manifestations Thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, quire more frequent evaluations

coagulopathy in order to receive psychological

Risks Severe hemorrhage, infection, locally support. In addition, photo-

aggressive with obstruction of vital graphic documentation may be a

structures useful adjunct to expectant man-

agement, allowing physicians and

Treatment Combination therapy—corticosteroids,

families to record the progression

chemotherapy, antiplatelet medications,

transfusions and involution of the heman-

gioma over time.

Hemangiomas located near vi-

tal structures and those that cause

obstruction or compression or

lymphatic malformations. 8 Ka- ment requires a multidisciplinary that have developed complica-

posifor m hemangioendothe- approach that includes dermatol- tions such as ulceration require

lioma is a rare vascular tumor that ogy, oncology, and pediatric surgi- additional evaluation and man-

presents at birth or within the first cal subspecialties. In patients who agement. Approximately 5% of

year of life and clinically appears do not succumb to complications, hemangiomas will ulcerate dur-

as a rapidly growing, purplish, in- spontaneous, often incomplete, ing the proliferative phase, and a

durated, compressible tumor. It resolution usually occurs.60 significant proportion of heman-

occurs most commonly in the giomas (20%) interfere with vital

retroperitoneum and on the ex- Treatment structures.66,67 Intervention may

tremities. The tumor is locally ag- The majority of hemangiomas also be indicated for a heman-

gressive, and complications may require no intervention and in gioma present in any location that

include life-threatening hemor- general the ultimate cosmetic out- demonstrates a very rapid growth

rhage, compression of vital struc- come is usually better in heman- rate with tripling or quadrupling

tures, infection, and respiratory giomas that are allowed involute in size within weeks in order to

distress. There is a high mortality spontaneously.65 It is imperative slow progression. Certain heman-

rate in affected infants. MRI, to educate parents and caregivers giomas, particularly those occur-

Doppler ultrasound, and histol- on the natural history of heman- ring on the nasal tip, the lip, and

ogy are useful in diagnosing Ka- giomas of infancy, particularly as perhaps some parotid lesions,

posifor m hemangioendothe- some parents are quite distressed characeristically show poor or in-

lioma. Coagulation studies and by the physical appearance of the complete involution. Heman-

complete blood cell counts hemangioma, especially during giomas present in these locations

should be followed carefully. Ag- the phase of rapid growth or with benefit from early intervention

gressive therapy is indicated and hemangiomas located on the with systemic corticosteroids and

may include systemic corticos- face. Sensitivity to these psychoso- with elective surgical intervention

teroids, cytotoxic medications cial issues is an integral part of the before school age.

such as cyclophosphamide and routine management of heman- The mainstay of treatment for

vincristine, antiplatelet agents, ε- giomas. Regular evaluations to symptomatic hemangiomas in-

aminocaproic acid, transexamic provide parental reassurance and volves the judicious administra-

acid, selective embolization, and to monitor growth, regression, tion of oral corticosteroids, which

transfusion of blood components. and the potential development of through mechanisms that remain

Surgical resection may be indi- complications are essential. More poorly characterized, help to pro-

cated in selected cases. Manage- frequent clinical evaluations are mote stabilization or regression of

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 757

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

most hemangiomas.68-70 A starting bone lengthening).74,75 Of note, tive necrosis with the production

dose of 2 to 3 mg/kg per day of adrenal suppression has been re- of self-limited post-laser purpura.

prednisone or prednisolone as a ported to occur in a significant Clinical improvement may be

single morning dose is commonly percentage of infants who have seen after the first treatment, al-

used, and the dose is increased as received intralesional or perile- though several treatments may be

needed to achieve a clinical re- sionsl steroid injections for the required to produce the desired

sponse. A decrease in the growth treatment of periorbital heman- clinical results. The pulsed-dye

rate, softening of the lesion, or giomas. 74,75 Administration of laser is most effective on superfi-

the development of bluish-gray stress-dose steroids following cial hemangiomas and remains

discoloration should be apparent completion of corticosteroid ther- ineffective in addressing the sig-

within 1 to 2 weeks of initiating apy should be considered under nificant dermal component of

therapy. Although various ap- appropriate circumstances in chil- deep hemangiomas. Pulsed dye

proaches have been used, therapy dren who have chronically re- laser therapy works optimally on

is typically maintained for 1 to 2 ceived systemic steroids due to fair skin types, as hypopigmenta-

months, after which time the dose concerns for adrenal suppression. tion may result when treating

is slowly tapered over several It should be recognized that in in- darker skin types as a result of in-

weeks to months. The use of high- fants who develop growth delay cidental damage to melanocytes.

potency topical steroids has been while on short courses of systemic In addition, hyperpigmentation,

of limited benefit for small super- steroids, catch-up growth is gener- scarring, and atrophy are poten-

ficial hemangiomas and currently ally seen after discontinuation.75 tial complications of pulsed dye

is used infrequently.71,72 Intrale- To minimize the risk of gastritis, laser therapy. Although many par-

sional corticosteroids can be use- prophylactic administration of an ents pressure clinicians to initiate

ful for selected small heman- oral H2 antihistamine may be pulsed-dye laser treatments for

giomas involving the lips, ears, helpful. In addition, it is recom- otherwise uncomplicated heman-

nose, and eyes. Small, superficial mended that children not receive giomas to hasten regression, sev-

hemangiomas and those involv- live virus vaccines such as the oral eral studies have suggested that

ing the perioral area appear to polio and varicella vaccines dur- the final cosmetic outcome when

have the best response rate; how- ing systemic steroid therapy. using the pulsed dye laser to treat

ever, there is a small but signifi- For life-threatening heman- uncomplicated hemangiomas is

cant risk of complications, includ- giomas that have failed to re- not improved when compared to

ing atrophy, skin necrosis, and spond to systemic corticosteroids, the results after natural regres-

adrenal suppression.73 Periorbital interferon-alpha, pulsed dye laser, sion. 88,90,94 However, heman-

intralesional injections are best surgery, and sclerotherapy have giomas on the nose, lips, or ears

performed by ophthalmologists, been employed. Interferon alpha often heal poorly with scarring af-

as there is a small but finite risk of therapy, although efficacious, is ter natural regression; therefore,

central retinal artery occlusion limited by an adverse effect pro- selected patients with superficial

and subsequent blindness. As in- file that includes fever, myalgias, hemangiomas in these locations

tralesional corticosteroids require transaminase elevations, neu- might benefit from early inter-

expertise and patience during ad- tropenia, anemia, and both re- vention with pulsed dye laser ther-

ministration to minimize the risk versible and irreversible neuro- apy in an effort to provide a better

of complications, many dermatol- logic sequelae such as spastic cosmetic outcome. In addition,

ogists prefer to administer sys- diplegia.76-86 children with telangiectatic re-

temic corticosteroids. The use of the flash-lamp mants of facial hemangiomas may

Although uncommon during pulsed-dye laser has gained popu- also benefit from pulsed dye laser

short-term therapy, the use of cor- larity for the treatment of residual therapy prior to enrolling in

ticosteroids can have several ad- telangiectasias in involuted he- school if they are self-conscious of

verse effects. Infants and children mangiomas as well as in the treat- their appearance.

must be monitored for side ef- ment of proliferating or ulcerated Surgical excision is indicated

fects such as hypertension, im- hemangiomas. 66,87-95 In current for localized hemangiomas on the

munosuppression, irritability, gas- usage, the pulsed dye laser emits a face that are unresponsive to sys-

tritis, weight gain or loss, and 585- to 595-nm wavelength that temic glucocorticoids and that

temporar y growth retardation targets oxyhemoglobin and re- are causing obstruction or com-

(through transitory inhibition of sults in selective vascular coagula- pression of vital structures such as

758 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

the ear or eye; excision is also ben- mune-modulator, was shown to be about their biology on a cellular

eficial for ulcerated or bleeding efficacious in the treatment of or molecular level. The identifica-

hemangiomas that have not re- two infants with uncomplicated tion of the progenitor cell that

sponded to more conser vative hemangiomas.113 In both cases, gives rise to hemangiomas of in-

treatment. 96-100 Some pediatric treatment was complicated by the fancy remains controverial; how-

plastic surgeons also recommend development of significant local ever, several cell markers for he-

early excision of pedunculated inflammation and crusting, which mangiomas have been recognized,

hemangiomas predicted to invo- resolved after a 2-week drug holi- including GLUT1, FcgammaRII,

lute with residual fibrofatty tissue day. Both infants showed com- merosin, and Lewis Y antigen.116

that would require subsequent plete resolution of the heman- Recently, several growth factors

surgical resection. Hemangiomas gioma after 2 treatment courses have been identified that are asso-

on the ears and those on the tip of of 3 to 6 weeks each, with no evi- ciated with the proliferation and

the nose (“Cyrano nose”) also dence of recurrence at 1 to 4 involution of hemangiomas. In-

tend to heal poorly as a result of months after treatment. Im- vestigations into the pathogenesis

damage to underlying cartilage, iquimod is US Food and Drug Ad- of hemangiomas of infancy are

and cosmetic outcome may be im- ministration–approved for the closely correlated with studies in-

proved by early treatment with treatment of genital warts and volving angiogenesis, and en-

pulsed-dye laser or surgical exci- basal cell carcinoma, but has been dothelial growth factors such as

sion.101-106 Some psychologically used extensively as an off-label vascular endothelial growth factor

distressing hemangiomas on the treatment for a variety of other cu- (VEGF) are are believed to play

face, in particular those on the taneous diseases, including com- an important role in the develop-

ears, lips, and in the periorbital mon warts, actinic keratoses, and ment of hemangiomas. As the ma-

region, may be removed during alopecia areata. Imiquimod stim- jority of hemangiomas occur spo-

the preschool years before school ulates innate and acquired immu- radically, genetic linkage studies

entry if involution is incomplete. nity through a variety of mecha- have provided only limited infor-

In addition, surgical excision to nisms, including the activation of mation on other candidate genes

improve final cosmetic outcome toll-like receptor-7 and the pro- to date.

may be indicated in those heman- duction of a variety of cytokines,

giomas that involute with residual including interferon alpha (IFN-α) Histopathology

scarring, cutaneous redundancy, and IL-12.114 Other investigators, The histopathology of heman-

areas of alopecia on the scalp, or using a mouse hemangioendothe- giomas varies depending on the

atrophy. Rarely, sclerotherapy has lioma model, have demonstrated clincal stage. During the prolifer-

been used, either alone or as an that application of imiqimod to ative stage of superficial heman-

adjunct therapy, for the treatment implanted tumors results in de- giomas, proliferating lobules of

of rapidly growing hemangiomas creased tumor growth and in- endothelial cells arranged in

in cosmetically sensitive areas or creased survival, with decreased strands and masses with few capil-

hemangiomas that have not fully tumor cell proliferation, in- lary lumens are seen in the super-

involuted.107-111 While generally creased tumor cell apoptosis, and ficial dermis. As the hemangioma

favorable results can be achieved, increased expression of tissue in- matures to the involutional stage,

there is small complication risk hibitor of metalloproteinase-1 the capillary lumens enlarge and

of cutaneous ulceration at the in- (TIMP-1).115 Further controlled the endothelial cells flatten; even-

jection site. Recently, MR-guided trials are indicated in order to val- tually, fibrosis ensues with obliter-

sclerotherapy has been studied idate use of imiquimod in the ation of the blood vessel lumens.

as a technique to target heman- treatment of hemangiomas of in- Deep (cavernous) hemangiomas,

giomas more effectively with the fancy, both complicated and un- by contrast, may manifest larger,

use of a minimum amount of complicated. irregular vascular spaces lined

sclerosant.112 with flattened endothelial cells

Current therapies for treating present in the deeper dermis and

life-threatening or complicated Pathogenesis subcutaneous tissue.117

hemangiomas are often limited Mast cells, pericytes, intersti-

by adverse effects and delays in Despite the common occur- tial cells, and fibroblasts are pre-

therapeutic effects. Recently, the rence of hemangiomas of infancy, sent in hemangiomas in all stages,

use of imiquimod, a topical im- until recently little was known although mast cells may be more

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 759

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

prominent in involuting heman- chromosome 5q in both spo- mal developmental continuum,

giomas.118-120 Recently, a role for radic hemangiomas and in sev- or whether these cells represent a

mast cells in the involution of he- eral hemangioma kindreds.127,128 subset of intially more mature en-

mangiomas was proposed based Nonrandom X-inactivation has dothelial cells that have regressed

on the observation that expres- also been demonstrated in he- to a more embryonic state as a re-

sion of clusterin/apoJ, a glycopro- mangioma-derived endothelial sult of some environmental or ge-

tein involved in cell apoptosis, is cells.126,129 This population of “an- netic insult.

increased in involuting heman- gioblastic” endothelial cells be-

giomas and localizes to mast cell haves more like embryonic en- Growth Factors

granules. 120,121 Endothelial cell dothelial cells as opposed to The VEGF family, which in-

apoptosis is increased in involut- neonatal endothelial cells, and cluded the ligands VEGF-A,

ing hemangiomas, and is postu- may represent a clonal popula- VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VGF-D, and

lated to play a major role in the in- tion of cells derived from en- VEGF-E, and the angiopoietin

volutional process, although the dothelial progenitor cells. Expres- family are well-characterized

triggers for induction of apoptosis sion of the human stem cell/ growth factor families that regu-

remain unknown.122,123 A CD68(+) progenitor cell marker CD133 has late endothelial cell proliferation

population of cells with dendritic been demonstrated to occur in a and angiogenesis. 132,133 The

cell morphology have also been small percentage of endothelial VEGF receptor family includes

shown to occur in proximity to the cells derived from hemangiomas, VEGFR-1 (also known as fms-re-

vascular endothelial cells that com- some of which also co-expressed lated tyrosine kinase-1 [Flt-1]),

prise infantile hemangiomas.124 the endothelial cell marker kinase VEGFR-2 (also known as kinase

insert domain-containing recep- insert domain-containing recep-

Endothelial Cell Origins tor (KDR), which mediates VEGF- tor [KDR] or fetal liver kinase-1

The origin of the endothelial mediated endothelial cell prolif- [Flk-1]) and VEGFR-3 (also

cells that comprise hemangiomas eration.130 Endothelial cells from known as Flt-4). The angiopoi-

of infancy remains controversial. primary cultures of hemangiomas etins Ang-1 and Ang-4 (stimula-

Some investigators have sug- of infancy, similar to fetal en- tory) and Ang-2 and Ang-3 (in-

gested a placental origin, either dothelial cells, express lower lev- hibitor y) bind to the tunica

involving embolic endothelial els of von Willebrand factor (vWF) interna endothelial cell kinase-2

cells or the differentiation of and platelet-endothelial cell ad- (Tie-2) receptor; a Tie-1 receptor

progenitor endothelial cells to- hesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1).131 also exists, although its ligand is

wards a placental phenotype dur- In addition, these cultured hu- unknown. Flk-1/KDR, Flt-1, Tie-1,

ing gestation.116 The normal invo- man endothelial cells assume a Tie-2, and Ang-2 are strongly ex-

lution of hemangiomas during spindled morphology more char- pressed in cultured hemangioma-

infancy may result from the loss of acteristic of embryonic endothe- derived endothelial cells and in

angiogenic stimuli previously pre- lial cells. Hemangioma-derived hemangioma tissue, while there is

sent during gestation, or alterna- endothelial cells also express in- minimal expression of Ang-1.134

tively, the rapid growth of heman- terstitial-collagen types I, III, and VEGF expression may be reduced

giomas during the proliferative V in all stages but predominantly in involuting hemangiomas, but

phase in early infancy may result during involution; in contrast, conflicting data exists. 118,134-137

from the loss of inhibitors of an- neonatal endothelial cells express Mutations in the VEGF receptors

giogenesis that maintain the pla- epithelial-specific type IV colla- Flk-1/KDR and Flt-4 have been

centa during pregnancy.125 gen.118,131 Taken together, these demonstrated in two clonal he-

Hemangioma-derived en- findings suggest that the endothe- mangioma cell populations.129

dothelial cells are clonal, and un- lial cells that constitute heman- In addition to VEGF, prolifer-

like normal endothelial cells, are giomas of infancy represent a dis- ating hemangiomas express high

stimulated to migrate in response tinct population of endothelial levels of several cellular markers,

to the angiogenesis inhibitor en- cells that appear to express an em- including proliferating cell nu-

dostatin.126 Evidence supporting bryonic phenotype. It is unclear clear antigen (PCNA), type IV col-

a clonal etiology for the endothe- whether these hemangioma-spe- lagenase (a metalloproteinase), E-

lial cells in hemangiomas include cific endothelial cells represent a selectin, and basic f ibroblast

genetic studies that have revealed clonal cell population that has growth factor (b-FGF), that are

loss of heterozygosity involving failed to progress along the nor- not expressed in vascular malfor-

760 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

mations. 118,138,139 PCNA is a ing hemangiomas, as well as in in- Endothelial cells from both

marker for cell proliferation, voluting hemangiomas that have proliferating and involuting he-

while bFGF is a potent angiogenic been treated with steroids.121,141 mangiomas express CD31 and

growth factor. Expression of al- Further studies are needed to elu- von Willebrand factor, two en-

pha-smooth musle actin (alpha- cidate the factors responsible for dothelial cell markers.118,138 Ex-

SMA), another vascular endothe- the induction of apoptosis in in- pression of the cell surface adhe-

lial marker, is highly expressed in voluting hemangiomas. sion molecule CD 146, another

both proliferating and involuting endothelial cell marker, is not ex-

hemangiomas but is rare in Cellular Markers pressed in hemangioma-derived

RICH, providing further evi- The placental-associated vas- endothelial cells, although ex-

dence that congenital heman- cular antigens GLUT1, an er y- pression is present in surround-

giomas, or at least RICH, are de- throcyte-type glucose transporter ing pericytes. 144 Involuting he-

rived from a phenotypically whose expression is restricted to mangiomas also express the

distinct endothelial cell popula- tissues with blood-tissue barrier angiogenesis inhibitor tissue in-

tion. 122 In involuting heman- function; merosin; FcgammaRII; hibitor of metalloproteinase-1

giomas, expression of the growth and Lewis Y antigen (LeY) are (TIMP-1). 138 A switch from ex-

inhibitor transforming growth strongly expressed in heman- pression of beta(3) integrin to

factor-beta (TGF-β) in increased, giomas of infancy; other vascular beta(4) intergrin also accompa-

as is expression of placental lesions, including vascular malfor- nies the progression from the pro-

growth factor (PlGF).118,122,137 mations and Kaposiform heman- liferative phase to the involu-

Other growth factors have gioendotheliomas, fail to demon- tional phase.124

been implicated in the heman- strate expression of these

gioma growth and involution. Ex- markers. 116,142 Kaposiform he-

pression of IL-6, platelet-derived mangioendotheliomas express Conclusions

growth factor-A (PDGF-A), PDGF- the endothelial cell markers

B, TGF-β1, and TGF-β3 are de- CD31, CD34, and Friend Hemangiomas of infancy are

creased in involuting heman- leukemia vir us integration-1 common, benign, vascular tu-

giomas, including those treated (FLI1), further confirming that mors that express specific cellular

with steroids, while expression of these markers can help to differ- markers that distinguish them

bFGF, remains unchanged.135,136 entiate benign hemangiomas of from other vascular tumors and

DNA microarray analysis of gene infancy from vascular tumors with malformations. The natural his-

expression in proliferating and in- malignant potential.143 This ob- tory of these lesions includes an

voluting hemangiomas indicates servation suggests a critical dis- inital proliferative phase during

that insulin-like growth factor-2 tinction between the origin of he- the first 6 to 9 months of life, fol-

(IGF-2) expression is upregulated mangiomas of infancy as opposed lowed by a slow involutional phase

in proliferating hemangiomas, to other vascular lesions, and fur- that begins after the first year of

suggesting a role for IGF-2 in he- ther implicates a cell phenotype life and progresses over several

mangioma growth.140 In addition, similar to placental-derived en- years. Most hemangiomas do not

several interferon-induced genes dothelial cells as the progenitor of require intervention and regress

are expressed in involuting he- hemangiomas of infancy. Con- spontaneously over several years.

mangiomas, indicating that inter- genital nonprogressive heman- However, treatment is indicated

feron may also play a role in the giomas (RICH), in contrast to for hemangiomas which obstruct

natural course of hemangioma common hemangiomas of infancy, or interfere with vital structures or

resolution. fail to express GLUT1 and LeY.54 are complicated by ulceration , in-

Apoptosis is believed to be a NICH are also negative for GLUT1 fection, or systemic involvement.

critical component of the involu- expression.58 The congenital he- First-line therapy is administration

tional pathway of hemangiomas mangiomas NICH and RICH, of systemic or, less commonly, in-

of infancy. Expression of clus- therefore, represent a phenotypi- tralesional corticosteroids. The

terin/apoJ, a marker of apopto- cally distinct subtype of vascular tu- most common complication of

sis, and mitochondrial cy- mor that may represent the end hemangiomas is ulceration,

tochrome b, which is also result of a different developmental which can be initially treated con-

involved in apoptosis, is in- pathway along the spectrum of en- servatively with topical therapy;

creased in spontaneously involut- dothelial cell maturation. pulsed dye laser treatments are in-

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS 761

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

S m o l i n s k i , Ya n

dicated for severe, non-healing ul- (new issues). Adv Dermatol. 1997; raphism: a neurosurgical problem

cerations. Early pulsed dye laser 13:375-423. with a dermatologic hallmark. Pediatr

therapy and surgical excision are 9. Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Heman- Dermatol. 1993;10(2):149-152.

reserved for hemangiomas which giomas and vascular malformations 23. Tubbs RS, Wellons JC, 3rd, Iskandar

in infants and children: a classifica- BJ, et al. Isolated flat capillary mid-

are life-threatening or have devel-

tion based on endothelial character- line lumbosacral hemangiomas as in-

oped complications and are not

istics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(3): dicators of occult spinal dysraphism.

responding to more conservative 412-422. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(2 Suppl):86-89.

management. Hemangiomas lo- 10. Finn MC, Glowacki J, Mulliken JB. 24. Waner M, North PE, Scherer KA, et al

cated in certain areas, including Congenital vascular lesions: clinical The nonrandom distribution of fa-

the midline lumbosacral area, the application of a new classification. cial hemangiomas. Arch Dermatol.

beard area of the face and neck, J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18(6):894-900. 2003;139(7):869-875.

and the periorbital area, may be as- 11. Bowers R, Graham E, Tomlinson K. 25. Metry DW, Hawrot A, Altman C, et al.

sociated with other anomalies, and The natural history of the strawberry Association of solitary, segmental he-

these children require appropriate nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:667- mangiomas of the skin with visceral

and timely evaluation . In addition, 680. hemangiomatosis. Arch Dermatol.

infants with facial segmental he- 12. Lister W. The natural history of straw- 2004;140(5):591-596.

mangiomas or the presence of berry nevi. Lancet. 1938;1:1429-1434. 26. Orlow SJ, Isakoff MS, Blei F. In-

multiple cutaneous hemangiomas 13. Waner M, Suen J. Hemangiomas and creased risk of symptomatic heman-

vascular malfomations of the head giomas of the airway in association

are at risk for potentially devastat-

and neck. In: M Waner JS, ed. The with cutaneous hemangiomas in a

ing systemic manifestations, and

Natural History of Hemangiomas. New “beard” distribution. J Pediatr.

should also receive further evalua- 1997;131(4):643-646.

York: Wiley-Liss; 1999:13-46.

tion as indicated. 27. Sie KC, Tampakopoulou DA. He-

14. Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Burrows

PE. Vascular anomalies. Curr Probl mangiomas and vascular malforma-

Surg. 2000;37(8):517-584. tions of the airway. Otolaryngol Clin

REFERENCES 15. Goldberg NS, Rosanova MA. Perior- North Am. 2000;33(1):209-220.

1. Holmahl K. Cutaneous heman- bital hemangiomas. Dermatol Clin. 28. Azizkhan RG. Laser surgery: new ap-

giomas in premature and mature in- 1992;10(4):653-661. plications for pediatric skin and air-

fants. Acta Paediatr. 1955;44:370-379. 16. Haik BG, Karcioglu ZA, Gordon RA, way lesions. Cur r Opin Pediatr.

2. Jacobs AH. Strawber r y heman- et al. Capillary hemangioma (infan- 2003;15(3):243-247.

giomas; the natural history of the un- tile periocular hemangioma). Surv 29. Madgy D, Ahsan SF, Kest D, et al. The

treated lesion. Calif Med. 1957;86 Ophthalmol. 1994;38(5):399-426. application of the potassium-titanyl-

(1):8-10. 17. Ceisler EJ, Santos L, Blei F. Periocu- phosphate (KTP) laser in the man-

3. Jacobs AH, Walton RG. The inci- lar hemangiomas: what every physi- agement of subglottic hemangioma.

dence of birthmarks in the neonate. cian should know. Pediatr Dermatol. Arch Otolar yngol Head Neck Surg.

Pediatrics. 1976;58(2):218-222. 2004;21(1):1-9. 2001;127(1):47-50.

18. Bouchard S, Yazbeck S, Lallier M. 30. Froehlich P, Seid AB, Morgon A.

4. Pratt AG. Birthmarks in infants. AMA

Perineal hemangioma, anorectal Contrasting strategic approaches to

Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;67(3):302-

malformation, and genital anomaly: the management of subglottic he-

305.

a new association? J Pediatr Surg. mangiomas. Int J Pediatr Otorhino-

5. Amir J, Metzker A, Krikler R, et al.

1999;34(7):1133-1135. laryngol. 1996;36(2):137-146.

Strawberry hemangioma in preterm

19. Albright AL, Gartner JC, Wiener ES. 31. Hughes CA, Rezaee A, Ludemann JP,

infants. Pediatr Der matol. 1986;3

Lumbar cutaneous hemangiomas as et al. Management of congenital sub-

(4):331-332. indicators of tethered spinal cords. glottic hemangioma. J Otolar yngol.

6. Powell TG, West CR, Pharoah PO, et Pediatrics. 1989;83(6):977-980. 1999;28(4):223-228.

al. Epidemiology of strawberry hae- 20. Allen RM, Sandquist MA, Piatt JH Jr, 32. Hawkins DB, Crockett DM,

mangioma in low birthweight in- et al. Ultrasonographic screening in Kahlstrom EJ, et al. Corticosteroid

fants. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116(5):635- infants with isolated spinal straw- management of air way heman-

641. berr y nevi. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(3 giomas: long-term follow-up. Laryn-

7. Blei F, Walter J, Orlow SJ, et al. Fa- Suppl):247-250. goscope. 1984;94(5 Pt 1):633-637.

milial segregation of hemangiomas 21. Humphreys RP. Clinical evaluation 33. Brook I. Microbiology of infected he-

and vascular malformations as an au- of cutaneous lesions of the back: mangiomas in children. Pediatr Der-

tosomal dominant trait. Arch Derma- spinal signatures that do not go away. matol. 2004;21(2):113-116.

tol. 1998;134(6):718-722. Clin Neurosurg. 1996;43:175-187. 34. Kim HJ, Colombo M, Frieden IJ. Ul-

8. Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. Vascular tu- 22. Serna MJ, Vazquez-Doval J, Vana- cerated hemangiomas: clinical char-

mors and vascular malformations clocha V, et al. Occult spinal dys- acteristics and response to therapy.

762 CLINICAL PEDIATRICS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 29, 2015

Hemangiomas of Infancy

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(6):962- the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. gioma: a rare cutaneous vascular

972. 2002;82(2):124-127. anomaly. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;

35. Metz BJ, Rubenstein MC, Levy ML, et 46. Herszkowicz L, dos Santos RG, Alves 107(7):1647-1654.

al. Response of ulcerated perineal EV, et al. Benign neonatal heman- 59. Mulliken JB, Enjolras O. Congenital

hemangiomas of infancy to becapler- giomatosis with mucosal involve- hemangiomas and infantile heman-

min gel, a recombinant human ment. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(6): gioma: missing links. J Am Acad Der-