Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Does Effort Still Count?

Does Effort Still Count?

Uploaded by

K57 TA THU HIENCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- BryqDocument5 pagesBryqsumeetfullstackdeveloperNo ratings yet

- Final Annotatedbibliography ZamoraDocument8 pagesFinal Annotatedbibliography Zamoraapi-460651104No ratings yet

- Mind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentDocument21 pagesMind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentPhu NguyenNo ratings yet

- 11 Scaffholding Relationship Among Online Quizz ParameteresDocument4 pages11 Scaffholding Relationship Among Online Quizz ParameteresPhilippe DurandNo ratings yet

- Tracking, Students' Effort, and Academic AchievementDocument24 pagesTracking, Students' Effort, and Academic AchievementEduardson Maguddayao100% (1)

- Stress Vulnerability and Academic Performance Among Management Students of UM TAGUM College: Basis For Enhancement ProgramDocument5 pagesStress Vulnerability and Academic Performance Among Management Students of UM TAGUM College: Basis For Enhancement ProgramThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Alexander Research 2breview 2bproject Final 2bpaperDocument8 pagesAlexander Research 2breview 2bproject Final 2bpaperapi-308646731No ratings yet

- Dolores Stand Alone Senior High School: The Problem and Review of Related LiteratureDocument15 pagesDolores Stand Alone Senior High School: The Problem and Review of Related LiteratureSophia VirayNo ratings yet

- Teaching To The Test or Testing To Teach: Exams Requiring Higher Order Thinking Skills Encourage Greater Conceptual UnderstandingDocument23 pagesTeaching To The Test or Testing To Teach: Exams Requiring Higher Order Thinking Skills Encourage Greater Conceptual UnderstandingAli RaufNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Classroom Evaluation Practices On STDocument44 pagesThe Impact of Classroom Evaluation Practices On STEstefavcvm99No ratings yet

- Cohen 1981Document29 pagesCohen 1981CQNo ratings yet

- MethodDocument7 pagesMethodUmar SaleemNo ratings yet

- Student Perceptions of Teaching EvaluationsDocument6 pagesStudent Perceptions of Teaching EvaluationsPamela Francisca Bobadilla BurgosNo ratings yet

- 12 Stirner G5 PR2Document12 pages12 Stirner G5 PR2ryancarles17No ratings yet

- Marshi 1Document15 pagesMarshi 1zlie79No ratings yet

- Student and Teacher Characteristics On Student Math AchievementDocument13 pagesStudent and Teacher Characteristics On Student Math AchievementSALMA SHAFIYYAH SHUKRINo ratings yet

- Mathematics Course Work Distribution and Student SuccessDocument4 pagesMathematics Course Work Distribution and Student Successapi-386746776No ratings yet

- Research Final Paper Group 4Document22 pagesResearch Final Paper Group 4Azalea NavarraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Test Item Classifications: Dr. Charles E. Notar (Emeritus)Document5 pagesIntroduction To Test Item Classifications: Dr. Charles E. Notar (Emeritus)NeelutpalGogoiNo ratings yet

- Research Thesis 01Document3 pagesResearch Thesis 01rajshree01No ratings yet

- Involving Students in AssessmentDocument7 pagesInvolving Students in AssessmentMaricris BlgtsNo ratings yet

- Article Revere Elden BartschDocument16 pagesArticle Revere Elden BartschDhanue Artha AjahNo ratings yet

- Tippin & Lafreniere, 2012Document10 pagesTippin & Lafreniere, 2012MadelynNo ratings yet

- Emeryetal 2018Document24 pagesEmeryetal 2018muththu10No ratings yet

- KKP Researchproposal 4249 1206Document15 pagesKKP Researchproposal 4249 1206api-592527773No ratings yet

- Exploring Common Correlates of Business Undergraduate Satisfaction With Their Degree Program Versus Expected EmploymentDocument10 pagesExploring Common Correlates of Business Undergraduate Satisfaction With Their Degree Program Versus Expected EmploymentvyonabusinessNo ratings yet

- PR2 BANGCALS GROUP. Updated Chapter 2Document21 pagesPR2 BANGCALS GROUP. Updated Chapter 2Justine BangcalNo ratings yet

- Larang RRL 5Document6 pagesLarang RRL 5Zenon Cynrik Zacarias CastroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document30 pagesChapter 3Rahmi MNo ratings yet

- Focusing On How Students StudyDocument8 pagesFocusing On How Students StudysajjadjeeNo ratings yet

- Jamain2021 PDFDocument20 pagesJamain2021 PDFOppo IndonesiaNo ratings yet

- Student Exam Analysis (Debriefing) Promotes Positive Changes in Exam Preparation and LearningDocument6 pagesStudent Exam Analysis (Debriefing) Promotes Positive Changes in Exam Preparation and LearningJanine Bernadette C. Bautista3180270No ratings yet

- Classroom Assessment For Student LearningDocument29 pagesClassroom Assessment For Student LearningAyi HadiyatNo ratings yet

- EEA622.Educational - Assessment.jan.2015 - AnswerDocument31 pagesEEA622.Educational - Assessment.jan.2015 - AnswerKesavanVekraman100% (1)

- AnnotatedDocument49 pagesAnnotatedAnish VeettiyankalNo ratings yet

- Final Research Analysis and CritiqueDocument6 pagesFinal Research Analysis and CritiquekathrynjillNo ratings yet

- 2 SigmaDocument14 pages2 SigmaDiseño SAurochNo ratings yet

- Assessment Literacy For Teacher Candidates: A Focused ApproachDocument18 pagesAssessment Literacy For Teacher Candidates: A Focused ApproachAiniNo ratings yet

- Departmental Examination Among The Tourism and Hospitality Management StudentsDocument9 pagesDepartmental Examination Among The Tourism and Hospitality Management StudentsHeiro KeystrifeNo ratings yet

- Peer Groups and Academic Achievement: Panel Evidence From Administrative DataDocument35 pagesPeer Groups and Academic Achievement: Panel Evidence From Administrative DatatapceNo ratings yet

- 1 - Analyzing - Factors - Affecting - Students - SatDocument8 pages1 - Analyzing - Factors - Affecting - Students - Satameera mohammed abdullahNo ratings yet

- Beumann Wegner2018 Article AnOutlookOnSelf AssessmentOfHoDocument7 pagesBeumann Wegner2018 Article AnOutlookOnSelf AssessmentOfHoFeleke BekeleNo ratings yet

- 4 HolisticAssessmentDocument10 pages4 HolisticAssessmentSmriti BalyanNo ratings yet

- Professional Paper AnnotatedDocument19 pagesProfessional Paper AnnotatedDayra CampoverdeNo ratings yet

- Swanson and Cole 2022 ValidationDocument26 pagesSwanson and Cole 2022 ValidationkenzieyohanespirituNo ratings yet

- Effective Teaching Behaviors in The College Classroom: A Critical Incident Technique From Students' PerspectiveDocument11 pagesEffective Teaching Behaviors in The College Classroom: A Critical Incident Technique From Students' Perspectivejinal patelNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Stress in Self and Peer AssessmentDocument15 pagesThe Impact of Stress in Self and Peer Assessmenta.ingham61No ratings yet

- Self-Efficacy, Test Anxiety, and Self-Reported Test-Taking Ability: How Do They Differ Between High-And Low-Achieving Students?Document8 pagesSelf-Efficacy, Test Anxiety, and Self-Reported Test-Taking Ability: How Do They Differ Between High-And Low-Achieving Students?amalia nur fitriatiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationDocument19 pagesComparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationJesús AlfredoNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationDocument19 pagesComparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationNicolas Santiago Jimenez CruzNo ratings yet

- Effort Value PersistanceDocument16 pagesEffort Value PersistancejohnNo ratings yet

- Academic Stress of College StudentsDocument11 pagesAcademic Stress of College StudentsYatheendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Maricutoiu ValidareDocument13 pagesMaricutoiu ValidareLupuleac ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- American Educational Research Association Educational ResearcherDocument14 pagesAmerican Educational Research Association Educational ResearcherTuan Mastura Tuan SohNo ratings yet

- This Paper To Fulfill The Last Assignment With Subject: Assessment and TeachingDocument5 pagesThis Paper To Fulfill The Last Assignment With Subject: Assessment and TeachingBayu Ren WarinNo ratings yet

- Academic Self-Efficacy As A PredictorDocument24 pagesAcademic Self-Efficacy As A PredictorAbubaker Mohamed HamedNo ratings yet

- Applying JDR To StudyingDocument16 pagesApplying JDR To StudyingYasmine GreenNo ratings yet

- Class Size and Teaching Competency Template 1 1Document8 pagesClass Size and Teaching Competency Template 1 1noelroajrNo ratings yet

- Cho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2010) - Student Revision With Peer and Expert Reviewing PDFDocument11 pagesCho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2010) - Student Revision With Peer and Expert Reviewing PDFJC REYESNo ratings yet

- Norm and Criterion-Referenced TestsDocument5 pagesNorm and Criterion-Referenced TestsBenjamin L. Stewart100% (4)

- Playful Testing: Designing a Formative Assessment Game for Data ScienceFrom EverandPlayful Testing: Designing a Formative Assessment Game for Data ScienceNo ratings yet

- 9.3 - Weinstein (2018) - The Social Media See-Saw - Positive and Negative Influences On Adolescents' Affective Well-BeingDocument27 pages9.3 - Weinstein (2018) - The Social Media See-Saw - Positive and Negative Influences On Adolescents' Affective Well-Beingazzy bacsalNo ratings yet

- Trends in Posting Frequency On Social Media PlatformsDocument12 pagesTrends in Posting Frequency On Social Media PlatformsMaryam AsadNo ratings yet

- HRM, Employee Well-Being and Organizational Performance: A Balanced PerspectiveDocument220 pagesHRM, Employee Well-Being and Organizational Performance: A Balanced PerspectiveHRzone67% (3)

- Our Findings Show Unit PlanDocument3 pagesOur Findings Show Unit PlansofianeNo ratings yet

- Binomial and Poisson DistributionsDocument2 pagesBinomial and Poisson DistributionsAnthea ClarkeNo ratings yet

- Lecture The Research Proposal PDFDocument28 pagesLecture The Research Proposal PDFTrish RamosNo ratings yet

- Integrating Sustainable Development in The Supply Chain: The Case of Life Cycle Assessment in Oil and Gas and Agricultural BiotechnologyDocument20 pagesIntegrating Sustainable Development in The Supply Chain: The Case of Life Cycle Assessment in Oil and Gas and Agricultural BiotechnologyAnonymous TX2OckgiZNo ratings yet

- 62233fp Bachelor Thesis EUR IBEB Final DraftDocument50 pages62233fp Bachelor Thesis EUR IBEB Final DraftLYNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Commentaries 2018: ST104b Statistics 2Document19 pagesExaminers' Commentaries 2018: ST104b Statistics 2Xinjie LinNo ratings yet

- Department of Statistics: Course Stats 330Document4 pagesDepartment of Statistics: Course Stats 330PETERNo ratings yet

- Students-Manual PDFDocument30 pagesStudents-Manual PDFdenzon malazarteNo ratings yet

- RES 6101 The Reading Guide 211Document95 pagesRES 6101 The Reading Guide 211Hà ThuNo ratings yet

- On Free Vibration Analysis of Thin-Walled Beams With Nonsymmetrical Open Cross-SectionsDocument5 pagesOn Free Vibration Analysis of Thin-Walled Beams With Nonsymmetrical Open Cross-SectionsAndras ZajNo ratings yet

- Dey's Medical Stores LTDDocument12 pagesDey's Medical Stores LTDAnirban KunduNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document5 pagesChapter 2KristinemaywamilNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Effect of Supply Chain Strategies and Collaboration On Performance Improvement Using MIMIC ModelDocument10 pagesAnalyzing The Effect of Supply Chain Strategies and Collaboration On Performance Improvement Using MIMIC ModelSiwaporn KunnapapdeelertNo ratings yet

- Specification For Glazed Fire-Clay Sanitary AppliancesDocument15 pagesSpecification For Glazed Fire-Clay Sanitary AppliancesyesvvnNo ratings yet

- Images of God and The Imaginary in The Face of Loss: A Quantitative Research On Vietnamese Immigrants Living in CanadaDocument18 pagesImages of God and The Imaginary in The Face of Loss: A Quantitative Research On Vietnamese Immigrants Living in Canadachu bikaNo ratings yet

- Alemayehu MesheshaDocument76 pagesAlemayehu MesheshaAyayaya YuyaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Food Trucks ' Service Quality On Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact Toward Customer LoyaltyDocument14 pagesThe Influence of Food Trucks ' Service Quality On Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact Toward Customer Loyaltynorhaya09No ratings yet

- 6 Qualitative Research and Its Importance in Daily LifeDocument25 pages6 Qualitative Research and Its Importance in Daily LifeDorinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter One PDFDocument22 pagesChapter One PDFmohammed jimjamNo ratings yet

- Core Tools Forms V5Document128 pagesCore Tools Forms V5hudelvillar100% (1)

- How Long Should Your Literature Review BeDocument6 pagesHow Long Should Your Literature Review Beafmyervganedba100% (1)

- Zhai PPT (Final)Document30 pagesZhai PPT (Final)Erap UsmanNo ratings yet

- Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Director - Yemen Mission Round of Momentum APSDocument2 pagesMonitoring, Evaluation and Learning Director - Yemen Mission Round of Momentum APSEsamNo ratings yet

- Experiment I - Introduction To The Analytical Balance and Volumetric Glassware ObjectiveDocument2 pagesExperiment I - Introduction To The Analytical Balance and Volumetric Glassware Objectivekarina_s_No ratings yet

- Literature Review of BRMDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of BRMChBabarBajwaNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Opportunities Facing Young EntrepreneursDocument58 pagesChallenges and Opportunities Facing Young EntrepreneursTimothy Sosa87% (15)

Does Effort Still Count?

Does Effort Still Count?

Uploaded by

K57 TA THU HIENOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Does Effort Still Count?

Does Effort Still Count?

Uploaded by

K57 TA THU HIENCopyright:

Available Formats

Topical Article

Teaching of Psychology

38(1) 10-15

Does Effort Still Count? More on ª The Author(s) 2011

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

What Makes the Grade DOI: 10.1177/0098628310390907

http://top.sagepub.com

Tracy E. Zinn,1 John F. Magnotti,1 Kimberly Marchuk,1

Bridget S. Schultz,1 Andrew Luther,1 and

Veronika Varfolomeeva1

Abstract

Previous research has examined differences between students and faculty regarding the weight of effort in assigning grades. Here,

students and faculty responded to questions regarding the relative weight of performance and effort on final grades and what

letter grades faculty should assign across different types of courses. The authors asked these questions in 2 scenarios: (a) high

effort, poor performance (students worked hard but performed poorly) and (b) low effort, high performance (students per-

formed well but did not work hard). Results showed that, as in previous research, students and faculty differed in how they would

assign grades, and students gave more weight to effort than faculty did. Students responded differently in low- and high-effort

conditions, whereas faculty remained consistent in their assessments.

Keywords

college students, grading, effort

In 2004, a southern college fired two professors for not a nonmajor course when they showed significant effort,

following a university grading policy that called for 60% of a regardless of low performance. Therefore, in cases where stu-

freshman’s grade and 50% of a sophomore’s grade to be based dents believe they have shown substantial effort, but had less

on effort (Smallwood, 2005). The firing of these professors than stellar performance, there will likely be a discrepancy

resulted in the American Association of University Professors between what grade a professor assigns and the grade students

censuring that college’s administration, emphasizing that grad- believe they deserve. This discrepancy could have real conse-

ing policies should be protected by academic freedom. Would quences in terms of instructor evaluations as well as students’

most students and instructors agree with this type of grading satisfaction with their courses.

policy? Should we, as instructors, be measuring effort? And We investigated whether this discrepancy would hold if stu-

if so, how would we do that fairly? dents performed well in a class where they had to put forth little

Adams (2005) investigated student and faculty perceptions effort. Should effort only help a grade, or could it count nega-

of whether faculty should include student effort when assigning tively? Furthermore, would statements about the importance of

final grades. Previous research indicated that although students effort match the grades participants assigned in different sce-

tended to advocate including effort, faculty were apt to narios? We asked professors and students how much weight

disagree. Although the faculty perspective has varied across effort should receive in determining final grades across differ-

different studies (e.g., Friedman & Manley, 1992), the consen- ent conditions. Our study built on Adams’s (2005) research in

sus of measurement experts and official grading policies is that the following ways: (a) We examined the impact students and

instructors should use quality of student performance to deter- faculty believe effort should have on final grades when effort is

mine grades (e.g., Howley, Kusimo, & Parrott, 2001). For low as well as when effort is high, (b) we addressed the issue of

instance, a grading scale might define an A as indicating ‘‘out- how an instructor would measure effort if he or she did include

standing achievement or performance.’’ It is unlikely that many

college and university grading schemes include criteria for how

hard a student would need to work to earn that A.

1

Nonetheless, compared to faculty, students are more James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, USA

likely to say that effort should weigh heavily in the final course

Corresponding Author:

grade determinations. In fact, the disparity between faculty and Tracy E. Zinn, Psychology Department, James Madison University,

students was quite large in Adams’s (2005) study, with more Harrisonburg, VA 22807, USA

than 70% of students saying they should earn at least a C in Email: zinnte@jmu.edu

Downloaded from top.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on September 19, 2016

Zinn et al. 11

it in the final grade, and (c) we asked respondents to rate the material,’’ ‘‘F indicates unsatisfactory performance/failure to

accuracy of several common measures of effort. meet minimum course requirements’’). These grade definitions

were the same as those Adams used.

For the second condition (low effort/high performance), we

Method described a situation in which course material comes easily for

Participants a student. Participants responded to the following scenario:

Students (n ¼ 184; 94 men) and faculty (n ¼ 59; 29 men) A student takes a course and performs very well, meeting the

from a midsized, public institution in the Southeast partici- highest level of evaluation for all course requirements. At the

pated in the study. Student respondents were primarily under- same time, he or she puts minimal effort into the course. What

classmen (98 freshmen, 59 sophomores, 20 juniors, and grade would you recommend the student receive, if the course

7 seniors), and faculty represented 41 different disciplines were____?

(the most frequent department cited was psychology, with

11 faculty). We recruited students via the psychology depart- The course types were the same as in the first condition. We

ment’s participant pool, where students could earn course also presented grading criteria on this page. Again, participants

credit for participating in research. To get a broad sample, also indicated how much performance and effort should con-

we sent an e-mail to all full-time faculty at the university tribute to a final grade in these types of situations (i.e., low

requesting their participation in the online survey. Although effort/high performance).

the faculty response rate was low, approximately 10%, we Finally, participants responded to questions regarding their

were able to obtain responses representing many different perceptions of student effort and rated the accuracy of eight

departments on campus. different methods of measuring student effort (e.g., class

attendance, quantity of class participation, self-reported

Survey Questions and Procedure effort). Participants also answered questions pertaining to stu-

dents’ typical study habits as well as how many hours spent

We built on Adams’s (2005) original survey materials; how- studying a week would indicate a superior effort on the part

ever, instead of using a paper survey, we collected data via of the student. We collected demographic data as well, includ-

Websurveyor, an online survey and data collection tool ing gender, age, classification (e.g., freshman, faculty), and

(http://websurveyor.com, 2006). The first page of the survey GPA, if applicable.

was a cover letter explaining the study and the data collection

procedures. Participants then completed a 19-item web survey.

Participants first reported the percentages (summing to 100)

they believed effort and performance should weigh in final

Results

course grades, in general (effort baseline). Participants then There were no significant differences across class rank (i.e.,

read a scenario that stated, freshman, sophomore, etc.) in terms of how much weight

effort should receive in the different scenarios, all ps > .20.

A student takes a course and performs unsatisfactorily, failing to Therefore, we classified participants as either students or

meet the minimum course requirements. At the same time, he or faculty for the analyses.

she puts a great deal of effort into the course. What grade would

you recommend the student receive, if the course were a ____?

Performance Versus Effort

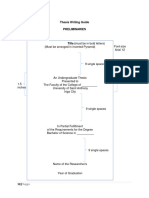

Participants responded to this high effort/low performance con- Using a mixed-factorial ANOVA, we found an interaction

dition for six different types of classes: (a) a general education between the effort condition (baseline, high, and low) and

requirement, (b) a general education elective, (c) a requirement participant classification (student vs. professor) on the

for his or her major, (d) an elective class for his or her major, percentage of the final grade attributed to effort, F(2, 480)

(e) a requirement for his or her minor, and (f) a class in medical ¼ 12.35, p < .001, Z2 ¼ .08 (see Figure 1). Faculty remained

school. These categories were similar to those used in Adams consistent in their weighting of effort across the different con-

(2005); however, we added two categories (elective class for ditions: The baseline effort (M ¼ 13.03, SD ¼ 12.01), high

his or her major and requirement for his or her minor) and effort/low performance (M ¼ 12.60, SD ¼ 11.73), and low

changed the wording to match that with which the sample effort/high performance (M ¼ 9.59, SD ¼ 10.43) conditions

population would be familiar (i.e., ‘‘liberal arts’’ to ‘‘general were not significantly different, t ¼ ns. However, planned

education’’). In addition, participants indicated how much comparison t tests, adjusted to control for family-wise error

performance and effort should weigh in grading students in rate, showed that although students weighted baseline effort

these types of situations (i.e., high effort/low performance). (M ¼ 40.25, SD ¼ 17.47) and high effort (M ¼ 38.75, SD ¼

To ensure that all participants had the same frame of reference 16.33) conditions similarly, t(183) ¼ 1.88, p ¼ .06; they

for assigning grades, we presented explanations of each grade weighted effort in both of these conditions higher than in the

letter on the same page (e.g., ‘‘A indicates outstanding/excellent low effort (M ¼ 27.66, SD ¼ 18.25) condition, t(183) ¼ 9.91,

achievement or performance; superior mastery of the course p < .0001, Z2 ¼ .35.

Downloaded from top.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on September 19, 2016

12 Teaching of Psychology 38(1)

p < .01. Sixty-eight percent of faculty and 53% of students

50

Baseline believed the typical student ‘‘mostly crams for tests.’’ There

High Effort/Low Performance

was also a significant difference between students (M ¼ 14.1,

Average % of Grade Attributable to Effort

Low Effort/High Performance

40 SD ¼ 9.55) and faculty (M ¼ 19.10, SD ¼ 11.56) on the esti-

mated average number of hours students spend studying, with

30

professors believing that students spend more time studying,

t(232) ¼ 3.23, p < .01, Z2 ¼ .06 (two outliers removed from the

student group).

20

10

Measuring Effort

We asked students and faculty, in both open-ended and closed

formats, what methods would be good measures of effort.

0

Faculty Student

Open-ended responses. Participants answered the question,

Figure 1. Average percentage of final grade (with SE bars) attributed ‘‘How should an instructor measure effort?’’ Responses of

to effort by faculty and students across three conditions (baseline, high faculty and students were similar in many respects. First, the

effort/low performance, low effort/high performance) responses indicated that both groups acknowledged that this

construct is difficult to measure. For example, one student

Assigned Grades stated, ‘‘This seems impossible to measure. Self reports may

work but they are easily misrepresented.’’ Along the same

Replicating Adams’s (2005) results, students in the high lines, one faculty member wrote, ‘‘There is no way for a profes-

effort/low performance condition were more lenient in assign- sor to know how much effort a student put forth on studying for

ing grades than faculty (see Table 1). Chi-square tests for inde- a test or writing a paper’’; and another stated, ‘‘This would be a

pendence showed that across each of the six course types, hard judgment call, considering professors don’t know exactly

students were more likely to assign higher grades than faculty, how much effort is put into a single student’s work.’’

all w2(4, N ¼ 242) > 70.00, ps < .001. Furthermore, although participants indicated that effort was

In the low effort/high performance scenarios, chi-square difficult to measure, both students and faculty alluded to the

tests for independence showed that the pattern of student and idea that an instructor would recognize effort when he or she

faculty grade distributions were significantly different for saw it. Representative student responses stated that faculty

(a) a major requirement, w2(4, N ¼ 240) ¼ 15.33, p < .01; and should base the effort score on ‘‘the appearance of how much

(b) a medical course, w2(4, N ¼ 241) ¼ 15.68, p < .01 (see work was done’’ or ‘‘the effort shown in class.’’ Faculty mem-

Table 2). The difference between the distributions was margin- bers included similar responses, with one professor saying,

ally significant for a minor requirement, w2(4, N ¼ 241) ¼ 8.54,

p ¼ .07. In contrast to the high effort/low performance condi- It is always obvious which students have put in effort into a

tion, students were more stringent than faculty with their grad- class and which students are doing the minimum . . . Professors

ing in these courses. For the remaining courses, students and are also able to see this, and need to take into account how much

faculty did not differ in their grading, ps > .05. effort is being put in by a student.

Faculty responses were nearly identical across the different

classes in the low effort/high performance condition, with Both students and faculty indicated that effort should count

more than 86% of respondents assigning As in all courses. more in the student’s favor than against him or her and also that

Students assigned As 57% to 78% of the time across the dif- effort should count more in certain courses, like art or music,

ferent courses. than in content courses of one’s major. For instance, one

instructor stated that ‘‘for some students course work is effort-

less and they understand the material quickly. I don’t think that

Student Study Habits and Effort should have a negative effect on their grade. However, I do feel

Similar to Adams (2005), in response to the question, ‘‘For a that effort should count for students who fail the class.’’ One

3-credit course, how many hours of studying per week would student said that ‘‘effort shouldn’t affect you if you are doing

indicate outstanding effort?’’ students (M ¼ 6.73, SD ¼ 4.41) excellent work; but if you are trying your best and not perform-

reported fewer hours than faculty (M ¼ 8.53, SD ¼ 3.72), ing up to the standards of the class, the amount of effort put in

t(232) ¼ 2.73, p < .01, Z2 ¼ .03 (three outliers removed from should be taken into account.’’

the student group). We also asked participants to indicate the Finally, many students and faculty reiterated that perfor-

most typical study pattern of students—cramming before a test, mance should count more than effort, with even a few students

mostly cramming, weekly study and exam review, and daily acknowledging that they were inconsistent in how they

study. There was a significant difference between students weighted effort in the different scenarios. One student summed

and faculty on this question as well, w2(3, N ¼ 240) ¼ 23.18, it up this way:

Downloaded from top.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on September 19, 2016

Zinn et al. 13

Table 1. Percentages of Faculty and Students Assigning Grades Across Course Types (High Effort, Low Performance Condition)

General Education Requirement General Education Elective Major Requirement Major Elective

Grade Faculty Student Faculty Student Faculty Student Faculty Student

A 0.0 3.8 0.0 7.1 0.0 2.7 0.0 1.6

B 0.0 27.7 0.0 23.9 0.0 8.7 0.0 15.2

C 8.6 44.6 8.6 37.5 3.4 31.0 5.2 46.2

D 25.9 19.0 29.3 23.4 10.3 33.2 24.1 27.7

F 65.5 4.9 62.1 8.2 86.6 24.5 70.7 9.2

n ¼ 58 n ¼ 184 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 184 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 184 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 184

Minor Requirement Medical Course

Grade Faculty Student Faculty Student

A 0.0 2.7 0.0 3.8

B 0.0 14.2 0.0 6.0

C 5.2 29.5 3.4 12.5

D 13.8 35.5 5.2 32.1

F 81.0 18.0 91.4 45.7

n ¼ 58 n ¼ 183 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 184

Table 2. Percentages of Faculty and Students Assigning Grades Across Course Types (Low Effort, High Performance Condition)

General Education Requirement General Education Elective Major Requirement Major Elective

Grade Faculty Student Faculty Student Faculty Student Faculty Student

A 87.9 78.7 87.9 76.9 86.2 58.2 86.2 69.9

B 10.3 15.3 10.3 17.6 12.1 35.2 12.1 23.5

C 1.7 3.8 1.7 3.8 1.7 4.4 1.7 4.4

D 0.0 2.2 0.0 1.1 0.0 2.2 0.0 1.6

F 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.5 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.5

n ¼ 58 n ¼ 183 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 182 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 182 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 183

Minor Requirement Medical Course

Grade Faculty Student Faculty Student

A 86.2 66.7 86.2 57.9

B 12.1 27.3 12.1 33.3

C 1.7 3.8 1.7 6.6

D 0.0 1.6 0.0 2.2

F 0.0 0.5 0.0 0.0

n ¼ 58 n ¼ 183 n ¼ 58 n ¼ 183

I gave inconsistent answers because I hadn’t considered if a students’ ratings of the accuracy of the measures were higher

student put in little effort and did well. Effort should be a than faculty’s: (a) class attendance, U ¼ 4,231, p ¼ .015;

small part of the grade, and performance should be much more (b) attending professor office hours, U ¼ 4,412, p ¼ .04; (c)

important. However this can vary greatly with different sub- completing extra credit assignments, U ¼ 3,059, p < .001;

jects. I would certainly not want my doctor to [earn an] F, but (d) quality of required assignments, U ¼ 4,556, p ¼ .05; (e)

[be an] A effort student. It would be like ‘‘I’m sorry, we have self-reported effort U ¼ 3,850, p ¼ .001; and (f) self-

some bad news, we just replaced your heart with a baked potato, reported study time, U ¼ 3,712, p < .001.

and you have about 5 seconds to live.’’ Nonetheless, the rank order of which measures were most

accurate was similar for the two groups. Both faculty (M ¼

Accuracy of effort measures. For the closed-ended responses, 4.34) and students (M ¼ 4.55) considered quality of assign-

students and faculty differed in how accurately they thought ments to be the most accurate measure of effort (scores could

different methods could measure student effort. Mann- range from 1 to 5, with 5 being very accurate), followed by

Whitney U analyses showed that, for six of the eight methods, class attendance (M ¼ 4.11 and 4.34 for faculty and students,

Downloaded from top.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on September 19, 2016

14 Teaching of Psychology 38(1)

respectively). The two groups also deemed self-reported study going to be different interpretations of how hard students are

time as the least accurate measure of effort, (M ¼ 2.53 and 3.58 working. Students might believe that they are performing

for faculty and students, respectively). closer to an ‘‘outstanding’’ level than faculty believe they are.

Other research has noted that students, especially freshmen,

who composed a large proportion of our sample, are likely

Discussion to underestimate the effort required in college courses

Results of our study were similar to those of Adams (2005), (Woehr & Cavell, 1993). Furthermore, Foushee and Sleigh

who found that in a situation describing high effort and low (2004) identified ‘‘poor awareness of teacher expectations’’

performance faculty ascribed approximately 17% of the grade (p. 305) as one of the leading reasons why students have poor

to effort, whereas students designated a much higher 38% to performance in a course. By explicitly addressing the discre-

effort. In our study, faculty reported that effort should count for pancy between their expectations and those of students,

approximately 13% of the grade compared to students’ sugges- faculty could alleviate some student problems, including stu-

tions of around 39%. Also as in Adams (2005), the grade distri- dents’ beliefs that they should have earned a higher grade,

butions for the high effort/low performance condition changed thus helping them in their college courses.

depending on the course type. Students were more lenient with

assigning grades, giving a modal grade of C for three course Measuring Effort

types—a general education requirement, a general education

To some extent, both faculty and students reported that effort

elective, and a major elective—but a modal grade of D in the

should count when assigning grades in both high effort/low

remaining courses—a major requirement, a minor requirement,

performance and low effort/high performance conditions; dif-

and a medical course. For faculty, the modal response was a

ferences were in degree. However, how to measure effort, if at

grade of F for all six conditions. These results mirror student and

all, is a difficult question for many instructors, a sentiment

faculty views of how much effort should contribute to the final

that was echoed by both faculty and student open-ended

grade in the high effort/low performance situations.

responses. Upon examination of the open-ended responses,

Extending Adams’s (2005) study, we found that faculty

it appears as though some of the remarks contradicted the

were consistent in how they weighted effort in the low- and

quantitative results. For example, students and faculty

high-performance conditions. In the low effort/high perfor-

responded that effort should count more in a student’s favor

mance condition, faculty and students reported that effort

than against him or her. Nonetheless, we do not believe this

should count for approximately 11% and 28% of the course

sentiment is necessarily at odds with the quantitative results.

grade, respectively. These results show that students, but not

Although students did respond that effort should count against

faculty, counted effort more in students’ favor than against

students in the low effort/high performance condition, stu-

them. However, students still counted effort as much more of

dents also reported that effort should weigh less in the low

the grade than did faculty, a result shown also in the grade dis-

effort/high performance conditions than in the high effort/low

tributions for the low effort/high performance scenarios. As we

performance conditions.

stated earlier, 86% of faculty assigned As in each of the low

Of course, performance and effort measures are not orthogo-

effort/high performance scenarios. Students were more strin-

nal. Typically, class attendance is associated with better perfor-

gent in their grading, assigning fewer As across the different

mance (e.g., Buckalew, Daly, & Coffield, 1986), as is time on

classes. Thus, students did not completely disregard their

task (Astin, 1993). Class attendance also seems to have other

claims that effort should count as part of the grade in the

peripheral benefits (Sleigh & Ritzer, 2004) beyond course

low-effort condition, as they were more willing than faculty

grades. Therefore, by encouraging these types of ‘‘effort’’ from

to penalize students for low effort.

students, faculty can show students the link between effort and

performance. Sleigh and Ritzer (2004) discussed some ways

Student Study Habits and Effort to improve class attendance, which emphasized linking the

Respondents in the current sample, both faculty and students, effort of coming to class with overall course performance

reported approximately the same amount of study time was (e.g., activities in class that help students learn the material).

necessary for ‘‘outstanding effort’’ as in Adams (2005). Also, In addition, several alternative teaching methods attempt to

students again believed that ‘‘outstanding effort’’ requires less link time on task outside of class with later exam performance

time than faculty did. Furthermore, students reported studying (e.g., Benedict & Anderton, 2004; Saville, Zinn, Neef, Van

less than faculty think they do, and more than half the students Norma, & Ferreri, 2006). By emphasizing the links between

reported that ‘‘mostly cramming’’ was the typical student’s effort and learning, faculty can show students how they mea-

modus operandi. Thus, results suggest that students would sure student effort more indirectly.

likely rate their effort as greater than faculty would, due to the

fact that students and faculty will have different criteria for

what counts as ‘‘outstanding effort.’’ If students are studying

Conclusions

less than faculty believe they are, and if students believe that These data will not come as a surprise to many instructors—we

less studying would count as outstanding effort, there are likely all have examples of students who say they really tried in the

Downloaded from top.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on September 19, 2016

Zinn et al. 15

class and, therefore, believe they deserve a higher grade. References

However, these results suggest that students and faculty may Adams, J. B. (2005). What makes the grade? Faculty and student per-

benefit from communication about grading procedures and pol- ceptions. Teaching of Psychology, 32, 21-24.

icies, as well as a frank discussion regarding what faculty con- Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years

sider to be ‘‘outstanding effort’’ in a class. Students likely do revisited. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

not know what workload is appropriate for college-level courses Benedict, J. O., & Anderton, J. B. (2004). Applying the Just-in-Time

and may often struggle because they do not know how to direct Teaching approach to teaching statistics. Teaching of Psychology,

their effort (i.e., they have poor study habits; Foushee & Sleigh, 31, 197-199.

2004; Woehr & Cavell, 1993). By attempting to eliminate the Buckalew, L. W., Daly, J. D., & Coffield, K. E. (1986). Relationship

differences in faculty and student criteria for and perceptions of initial class attendance and seating location to academic perfor-

of effort, faculty can help students succeed and possibly reduce mance in psychology classes. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society,

the belief that a professor is unfair—both worthy goals. 24, 63-64.

Although not explicitly examined in the current study, stu- Foushee, R. D., & Sleigh, M. J. (2004). Going the extra mile: Identify-

dents likely believe that effort should weigh more heavily when ing and assisting struggling students. In B. Perlman, L. I. McCann,

there is a tenuous link between their effort and their class per- & S. H. McFadden (Eds.), Lessons learned: Vol. 2. Practical

formance. Helping students see the links between their work advice for the teaching of psychology (pp. 303-311). Washington,

and their performance should attenuate feelings of learned DC: American Psychological Society.

helplessness and the need students feel to have their effort Friedman, S. J., & Manley, M. (1992). Improving high school grading

graded. Instructors can explain the reasons behind their assign- practices: ‘‘Experts’’ vs. practitioners. NASSP Bulletin, 76,

ments as well as identify struggling students to help them direct 100-104.

their efforts appropriately (see Foushee & Sleigh [2004] and Howley, A., Kusimo, P. S., & Parrott, L. (2001). Grading and the ethos

Svinicki [2006] for ideas on how to help struggling students). of effort. Learning Environments Research, 3, 229-246.

This way faculty will not have to measure student effort; effort Saville, B. K., Zinn, T. E., Neef, N. A., Van Norma, R., & Ferreri, S. J.

will be a component of students’ performance. (2006). A comparison of interteaching and lecture in the college

classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 49-61.

Acknowledgments Sleigh, M. J., & Ritzer, D. R. (2004). Encouraging student attendance.

We thank Natalie Lawrence, Bryan Saville, and three anonymous ToP In B. Perlman, L. I. McCann, & S. H. McFadden (Eds.), Lessons

reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts. learned: Vol. 2. Practical advice for the teaching of psychology

(pp. 287-293). Washington, DC: American Psychological Society.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest Smallwood, S. (2005, January 21). Faculty group censures Benedict

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the author- College again, this time over ‘‘A for effort’’ policy [Electronic ver-

ship and/or publication of this article. sion]. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 51, A11.

Svinicki, M. D. (2006). Helping students do well in class: GAMES.

Funding APS Observer, 19(10), 31-34.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the Woehr, D. J., & Cavell, T. A. (1993). Self-report measures of ability,

research and/or authorship of this article: This research was supported effort, and nonacademic activity as predictors of introductory psy-

in part by a Psychology Department student grant. chology test scores. Teaching of Psychology, 20, 156-160.

Downloaded from top.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on September 19, 2016

You might also like

- BryqDocument5 pagesBryqsumeetfullstackdeveloperNo ratings yet

- Final Annotatedbibliography ZamoraDocument8 pagesFinal Annotatedbibliography Zamoraapi-460651104No ratings yet

- Mind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentDocument21 pagesMind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentPhu NguyenNo ratings yet

- 11 Scaffholding Relationship Among Online Quizz ParameteresDocument4 pages11 Scaffholding Relationship Among Online Quizz ParameteresPhilippe DurandNo ratings yet

- Tracking, Students' Effort, and Academic AchievementDocument24 pagesTracking, Students' Effort, and Academic AchievementEduardson Maguddayao100% (1)

- Stress Vulnerability and Academic Performance Among Management Students of UM TAGUM College: Basis For Enhancement ProgramDocument5 pagesStress Vulnerability and Academic Performance Among Management Students of UM TAGUM College: Basis For Enhancement ProgramThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Alexander Research 2breview 2bproject Final 2bpaperDocument8 pagesAlexander Research 2breview 2bproject Final 2bpaperapi-308646731No ratings yet

- Dolores Stand Alone Senior High School: The Problem and Review of Related LiteratureDocument15 pagesDolores Stand Alone Senior High School: The Problem and Review of Related LiteratureSophia VirayNo ratings yet

- Teaching To The Test or Testing To Teach: Exams Requiring Higher Order Thinking Skills Encourage Greater Conceptual UnderstandingDocument23 pagesTeaching To The Test or Testing To Teach: Exams Requiring Higher Order Thinking Skills Encourage Greater Conceptual UnderstandingAli RaufNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Classroom Evaluation Practices On STDocument44 pagesThe Impact of Classroom Evaluation Practices On STEstefavcvm99No ratings yet

- Cohen 1981Document29 pagesCohen 1981CQNo ratings yet

- MethodDocument7 pagesMethodUmar SaleemNo ratings yet

- Student Perceptions of Teaching EvaluationsDocument6 pagesStudent Perceptions of Teaching EvaluationsPamela Francisca Bobadilla BurgosNo ratings yet

- 12 Stirner G5 PR2Document12 pages12 Stirner G5 PR2ryancarles17No ratings yet

- Marshi 1Document15 pagesMarshi 1zlie79No ratings yet

- Student and Teacher Characteristics On Student Math AchievementDocument13 pagesStudent and Teacher Characteristics On Student Math AchievementSALMA SHAFIYYAH SHUKRINo ratings yet

- Mathematics Course Work Distribution and Student SuccessDocument4 pagesMathematics Course Work Distribution and Student Successapi-386746776No ratings yet

- Research Final Paper Group 4Document22 pagesResearch Final Paper Group 4Azalea NavarraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Test Item Classifications: Dr. Charles E. Notar (Emeritus)Document5 pagesIntroduction To Test Item Classifications: Dr. Charles E. Notar (Emeritus)NeelutpalGogoiNo ratings yet

- Research Thesis 01Document3 pagesResearch Thesis 01rajshree01No ratings yet

- Involving Students in AssessmentDocument7 pagesInvolving Students in AssessmentMaricris BlgtsNo ratings yet

- Article Revere Elden BartschDocument16 pagesArticle Revere Elden BartschDhanue Artha AjahNo ratings yet

- Tippin & Lafreniere, 2012Document10 pagesTippin & Lafreniere, 2012MadelynNo ratings yet

- Emeryetal 2018Document24 pagesEmeryetal 2018muththu10No ratings yet

- KKP Researchproposal 4249 1206Document15 pagesKKP Researchproposal 4249 1206api-592527773No ratings yet

- Exploring Common Correlates of Business Undergraduate Satisfaction With Their Degree Program Versus Expected EmploymentDocument10 pagesExploring Common Correlates of Business Undergraduate Satisfaction With Their Degree Program Versus Expected EmploymentvyonabusinessNo ratings yet

- PR2 BANGCALS GROUP. Updated Chapter 2Document21 pagesPR2 BANGCALS GROUP. Updated Chapter 2Justine BangcalNo ratings yet

- Larang RRL 5Document6 pagesLarang RRL 5Zenon Cynrik Zacarias CastroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document30 pagesChapter 3Rahmi MNo ratings yet

- Focusing On How Students StudyDocument8 pagesFocusing On How Students StudysajjadjeeNo ratings yet

- Jamain2021 PDFDocument20 pagesJamain2021 PDFOppo IndonesiaNo ratings yet

- Student Exam Analysis (Debriefing) Promotes Positive Changes in Exam Preparation and LearningDocument6 pagesStudent Exam Analysis (Debriefing) Promotes Positive Changes in Exam Preparation and LearningJanine Bernadette C. Bautista3180270No ratings yet

- Classroom Assessment For Student LearningDocument29 pagesClassroom Assessment For Student LearningAyi HadiyatNo ratings yet

- EEA622.Educational - Assessment.jan.2015 - AnswerDocument31 pagesEEA622.Educational - Assessment.jan.2015 - AnswerKesavanVekraman100% (1)

- AnnotatedDocument49 pagesAnnotatedAnish VeettiyankalNo ratings yet

- Final Research Analysis and CritiqueDocument6 pagesFinal Research Analysis and CritiquekathrynjillNo ratings yet

- 2 SigmaDocument14 pages2 SigmaDiseño SAurochNo ratings yet

- Assessment Literacy For Teacher Candidates: A Focused ApproachDocument18 pagesAssessment Literacy For Teacher Candidates: A Focused ApproachAiniNo ratings yet

- Departmental Examination Among The Tourism and Hospitality Management StudentsDocument9 pagesDepartmental Examination Among The Tourism and Hospitality Management StudentsHeiro KeystrifeNo ratings yet

- Peer Groups and Academic Achievement: Panel Evidence From Administrative DataDocument35 pagesPeer Groups and Academic Achievement: Panel Evidence From Administrative DatatapceNo ratings yet

- 1 - Analyzing - Factors - Affecting - Students - SatDocument8 pages1 - Analyzing - Factors - Affecting - Students - Satameera mohammed abdullahNo ratings yet

- Beumann Wegner2018 Article AnOutlookOnSelf AssessmentOfHoDocument7 pagesBeumann Wegner2018 Article AnOutlookOnSelf AssessmentOfHoFeleke BekeleNo ratings yet

- 4 HolisticAssessmentDocument10 pages4 HolisticAssessmentSmriti BalyanNo ratings yet

- Professional Paper AnnotatedDocument19 pagesProfessional Paper AnnotatedDayra CampoverdeNo ratings yet

- Swanson and Cole 2022 ValidationDocument26 pagesSwanson and Cole 2022 ValidationkenzieyohanespirituNo ratings yet

- Effective Teaching Behaviors in The College Classroom: A Critical Incident Technique From Students' PerspectiveDocument11 pagesEffective Teaching Behaviors in The College Classroom: A Critical Incident Technique From Students' Perspectivejinal patelNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Stress in Self and Peer AssessmentDocument15 pagesThe Impact of Stress in Self and Peer Assessmenta.ingham61No ratings yet

- Self-Efficacy, Test Anxiety, and Self-Reported Test-Taking Ability: How Do They Differ Between High-And Low-Achieving Students?Document8 pagesSelf-Efficacy, Test Anxiety, and Self-Reported Test-Taking Ability: How Do They Differ Between High-And Low-Achieving Students?amalia nur fitriatiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationDocument19 pagesComparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationJesús AlfredoNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationDocument19 pagesComparison of Student Evaluations of Teaching With Online and Paper-Based AdministrationNicolas Santiago Jimenez CruzNo ratings yet

- Effort Value PersistanceDocument16 pagesEffort Value PersistancejohnNo ratings yet

- Academic Stress of College StudentsDocument11 pagesAcademic Stress of College StudentsYatheendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Maricutoiu ValidareDocument13 pagesMaricutoiu ValidareLupuleac ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- American Educational Research Association Educational ResearcherDocument14 pagesAmerican Educational Research Association Educational ResearcherTuan Mastura Tuan SohNo ratings yet

- This Paper To Fulfill The Last Assignment With Subject: Assessment and TeachingDocument5 pagesThis Paper To Fulfill The Last Assignment With Subject: Assessment and TeachingBayu Ren WarinNo ratings yet

- Academic Self-Efficacy As A PredictorDocument24 pagesAcademic Self-Efficacy As A PredictorAbubaker Mohamed HamedNo ratings yet

- Applying JDR To StudyingDocument16 pagesApplying JDR To StudyingYasmine GreenNo ratings yet

- Class Size and Teaching Competency Template 1 1Document8 pagesClass Size and Teaching Competency Template 1 1noelroajrNo ratings yet

- Cho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2010) - Student Revision With Peer and Expert Reviewing PDFDocument11 pagesCho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2010) - Student Revision With Peer and Expert Reviewing PDFJC REYESNo ratings yet

- Norm and Criterion-Referenced TestsDocument5 pagesNorm and Criterion-Referenced TestsBenjamin L. Stewart100% (4)

- Playful Testing: Designing a Formative Assessment Game for Data ScienceFrom EverandPlayful Testing: Designing a Formative Assessment Game for Data ScienceNo ratings yet

- 9.3 - Weinstein (2018) - The Social Media See-Saw - Positive and Negative Influences On Adolescents' Affective Well-BeingDocument27 pages9.3 - Weinstein (2018) - The Social Media See-Saw - Positive and Negative Influences On Adolescents' Affective Well-Beingazzy bacsalNo ratings yet

- Trends in Posting Frequency On Social Media PlatformsDocument12 pagesTrends in Posting Frequency On Social Media PlatformsMaryam AsadNo ratings yet

- HRM, Employee Well-Being and Organizational Performance: A Balanced PerspectiveDocument220 pagesHRM, Employee Well-Being and Organizational Performance: A Balanced PerspectiveHRzone67% (3)

- Our Findings Show Unit PlanDocument3 pagesOur Findings Show Unit PlansofianeNo ratings yet

- Binomial and Poisson DistributionsDocument2 pagesBinomial and Poisson DistributionsAnthea ClarkeNo ratings yet

- Lecture The Research Proposal PDFDocument28 pagesLecture The Research Proposal PDFTrish RamosNo ratings yet

- Integrating Sustainable Development in The Supply Chain: The Case of Life Cycle Assessment in Oil and Gas and Agricultural BiotechnologyDocument20 pagesIntegrating Sustainable Development in The Supply Chain: The Case of Life Cycle Assessment in Oil and Gas and Agricultural BiotechnologyAnonymous TX2OckgiZNo ratings yet

- 62233fp Bachelor Thesis EUR IBEB Final DraftDocument50 pages62233fp Bachelor Thesis EUR IBEB Final DraftLYNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Commentaries 2018: ST104b Statistics 2Document19 pagesExaminers' Commentaries 2018: ST104b Statistics 2Xinjie LinNo ratings yet

- Department of Statistics: Course Stats 330Document4 pagesDepartment of Statistics: Course Stats 330PETERNo ratings yet

- Students-Manual PDFDocument30 pagesStudents-Manual PDFdenzon malazarteNo ratings yet

- RES 6101 The Reading Guide 211Document95 pagesRES 6101 The Reading Guide 211Hà ThuNo ratings yet

- On Free Vibration Analysis of Thin-Walled Beams With Nonsymmetrical Open Cross-SectionsDocument5 pagesOn Free Vibration Analysis of Thin-Walled Beams With Nonsymmetrical Open Cross-SectionsAndras ZajNo ratings yet

- Dey's Medical Stores LTDDocument12 pagesDey's Medical Stores LTDAnirban KunduNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document5 pagesChapter 2KristinemaywamilNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Effect of Supply Chain Strategies and Collaboration On Performance Improvement Using MIMIC ModelDocument10 pagesAnalyzing The Effect of Supply Chain Strategies and Collaboration On Performance Improvement Using MIMIC ModelSiwaporn KunnapapdeelertNo ratings yet

- Specification For Glazed Fire-Clay Sanitary AppliancesDocument15 pagesSpecification For Glazed Fire-Clay Sanitary AppliancesyesvvnNo ratings yet

- Images of God and The Imaginary in The Face of Loss: A Quantitative Research On Vietnamese Immigrants Living in CanadaDocument18 pagesImages of God and The Imaginary in The Face of Loss: A Quantitative Research On Vietnamese Immigrants Living in Canadachu bikaNo ratings yet

- Alemayehu MesheshaDocument76 pagesAlemayehu MesheshaAyayaya YuyaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Food Trucks ' Service Quality On Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact Toward Customer LoyaltyDocument14 pagesThe Influence of Food Trucks ' Service Quality On Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact Toward Customer Loyaltynorhaya09No ratings yet

- 6 Qualitative Research and Its Importance in Daily LifeDocument25 pages6 Qualitative Research and Its Importance in Daily LifeDorinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter One PDFDocument22 pagesChapter One PDFmohammed jimjamNo ratings yet

- Core Tools Forms V5Document128 pagesCore Tools Forms V5hudelvillar100% (1)

- How Long Should Your Literature Review BeDocument6 pagesHow Long Should Your Literature Review Beafmyervganedba100% (1)

- Zhai PPT (Final)Document30 pagesZhai PPT (Final)Erap UsmanNo ratings yet

- Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Director - Yemen Mission Round of Momentum APSDocument2 pagesMonitoring, Evaluation and Learning Director - Yemen Mission Round of Momentum APSEsamNo ratings yet

- Experiment I - Introduction To The Analytical Balance and Volumetric Glassware ObjectiveDocument2 pagesExperiment I - Introduction To The Analytical Balance and Volumetric Glassware Objectivekarina_s_No ratings yet

- Literature Review of BRMDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of BRMChBabarBajwaNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Opportunities Facing Young EntrepreneursDocument58 pagesChallenges and Opportunities Facing Young EntrepreneursTimothy Sosa87% (15)