Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters

Uploaded by

Raúl Carbonell HerreraCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Schalms Veterinary Hematology 7Th Edition Marjory B Brooks All ChapterDocument67 pagesSchalms Veterinary Hematology 7Th Edition Marjory B Brooks All Chapterefrain.blair179100% (13)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Persuasive Analytical Essays: Nguyen Khanh Huy EAP1119.5BDocument3 pagesPersuasive Analytical Essays: Nguyen Khanh Huy EAP1119.5BKhánh Huy NguyễnNo ratings yet

- 06 237046 001 - BDDocument1 page06 237046 001 - BDcarlos yepezNo ratings yet

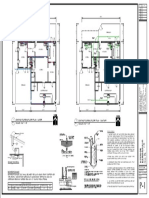

- Existing Plumbing Floor Plan - Water 1 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0" Existing Plumbing Floor Plan - Sanitary 2 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Document1 pageExisting Plumbing Floor Plan - Water 1 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0" Existing Plumbing Floor Plan - Sanitary 2 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- EXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0": Electrical Riser DiagramDocument1 pageEXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0": Electrical Riser DiagramRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- NW 7 AVE-A1 - FlattenedDocument1 pageNW 7 AVE-A1 - FlattenedRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- NOT MODIFIED IN The Hatch Selection: Date Revision NODocument1 pageNOT MODIFIED IN The Hatch Selection: Date Revision NORaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- Electrical Riser Diagram: EXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Document1 pageElectrical Riser Diagram: EXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- 890 SW 87 Ave-E1Document1 page890 SW 87 Ave-E1Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- 2916-E1 FlattenedDocument1 page2916-E1 FlattenedRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- 2007 Zeisel Inquiry by Design Review 2007Document3 pages2007 Zeisel Inquiry by Design Review 2007Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- Detail "A" Roof Penetration: Roof Mounted Make Up Air Hood Guy Wire Connection To Bar JoistDocument1 pageDetail "A" Roof Penetration: Roof Mounted Make Up Air Hood Guy Wire Connection To Bar JoistRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- La Consolacion College Manila: Report On Learning Progress and AchievementDocument2 pagesLa Consolacion College Manila: Report On Learning Progress and AchievementBryle Garnet FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Procedure Sick Bay 2017Document6 pagesProcedure Sick Bay 2017Syed FareedNo ratings yet

- Technical Specification For Sorghum GrainsDocument6 pagesTechnical Specification For Sorghum GrainsMohd SaifulNo ratings yet

- Name of Infection/virus Acquired at What Time How To Test For It Likely S/s HSVDocument1 pageName of Infection/virus Acquired at What Time How To Test For It Likely S/s HSVC RNo ratings yet

- List of Periodic Checks Life Saving & Fire Fighting EquipmentDocument5 pagesList of Periodic Checks Life Saving & Fire Fighting EquipmentSandro CheNo ratings yet

- Exp. (3) Comparing Specific Heat of Water and Vegetable Oil: Year Mr. Mohammed MahmoudDocument17 pagesExp. (3) Comparing Specific Heat of Water and Vegetable Oil: Year Mr. Mohammed Mahmoudجیهاد عبدالكريم فارس0% (1)

- SA2 2014 English Course - ADocument8 pagesSA2 2014 English Course - AsunnyNo ratings yet

- Line and Cable ModellingDocument23 pagesLine and Cable ModellingarunmozhiNo ratings yet

- Conservation of A Neolithic Plaster StatueDocument1 pageConservation of A Neolithic Plaster StatueJC4413No ratings yet

- TI Furadur Kitt 322 - enDocument3 pagesTI Furadur Kitt 322 - engonzalogvargas01No ratings yet

- Specimen Cover Letters and Job Application LettersDocument4 pagesSpecimen Cover Letters and Job Application LettersVthree YsNo ratings yet

- Implementing A Digital Transformation: November 2018Document5 pagesImplementing A Digital Transformation: November 2018Hasti YektaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Pipe NetworksDocument14 pagesAnalysis of Pipe NetworksAhmad Sana100% (2)

- 1 Bengaluru Urban Dist:: Sl. No. Industrial Area Date of Revision (B.M.Date) Prevailing Price/Acre (Rs. in Lakhs) 1 2 3 4Document8 pages1 Bengaluru Urban Dist:: Sl. No. Industrial Area Date of Revision (B.M.Date) Prevailing Price/Acre (Rs. in Lakhs) 1 2 3 4Raju BMNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Operation Assembly Repair Inspection of HM Cargo Tanks June 09 508Document105 pagesGuidelines For Operation Assembly Repair Inspection of HM Cargo Tanks June 09 508paulon9271No ratings yet

- (PPT) Anatomy 2.5 Lower Limbs - Blood and Nerve Supply - Dr. Tan PDFDocument110 pages(PPT) Anatomy 2.5 Lower Limbs - Blood and Nerve Supply - Dr. Tan PDFPreeti Joan BuxaniNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheets English 2, Quarter 3, Week 1Document11 pagesLearning Activity Sheets English 2, Quarter 3, Week 1CHERIE LYN TORRECAMPONo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management - Pgfa1941Document9 pagesSupply Chain Management - Pgfa1941Ravina SinghNo ratings yet

- Nandha Engineering College (Autonomous) : 17mex12 - Internal Combustion EnginesDocument36 pagesNandha Engineering College (Autonomous) : 17mex12 - Internal Combustion EnginesSugumar MuthusamyNo ratings yet

- 501c3.guidelines Issued by The IRSDocument31 pages501c3.guidelines Issued by The IRSThe Department of Official InformationNo ratings yet

- 4.1overview of Preventive MaintenanceDocument32 pages4.1overview of Preventive MaintenanceVANESSA ESAYASNo ratings yet

- Histology EssayDocument4 pagesHistology EssayalzayyanauroraNo ratings yet

- Goonj..: Making Clothing A Matter of Concern.Document46 pagesGoonj..: Making Clothing A Matter of Concern.sharat2170% (1)

- Jung Typology TestDocument2 pagesJung Typology TestPhuong Thanh ANNo ratings yet

- School Orientation Narrative Report 1Document2 pagesSchool Orientation Narrative Report 1Marry Joy Molina100% (5)

- Short Catalog 160719 HRDocument30 pagesShort Catalog 160719 HRtuanudinNo ratings yet

- Contents and Front Matter PDFDocument13 pagesContents and Front Matter PDFAbdelrhman MadyNo ratings yet

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters

Uploaded by

Raúl Carbonell HerreraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters

Uploaded by

Raúl Carbonell HerreraCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/259432942

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related

Disasters

Article in Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness · February 2013

DOI: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22

CITATIONS READS

479 11,966

2 authors:

Ginny Sprang Miriam Silman

University of Kentucky University of Kentucky

126 PUBLICATIONS 2,547 CITATIONS 14 PUBLICATIONS 497 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Scientific Meeting 2008 from Neuroscience to Social Practice View project

STSI-OA View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Ginny Sprang on 30 March 2020.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth

After Health-Related Disasters

Ginny Sprang, PhD, and Miriam Silman, MSW

ABSTRACT

Objectives: This study investigated the psychosocial responses of children and their parents to pandemic

disasters, specifically measuring traumatic stress responses in children and parents with varying

disease-containment experiences.

Methods: A mixed-method approach using survey, focus groups, and interviews produced data from 398

parents. Adult respondents completed the University of California at Los Angeles Posttraumatic Stress

Disorder Reaction Index (PTSD-RI) Parent Version and the PTSD Check List Civilian Version (PCL-C).

Results: Disease-containment measures such as quarantine and isolation can be traumatizing to a

significant portion of children and parents. Criteria for PTSD was met in 30% of isolated or quarantined

children based on parental reports, and 25% of quarantined or isolated parents (based on self-reports).

Conclusions: These findings indicate that pandemic disasters and subsequent disease-containment

responses may create a condition that families and children find traumatic. Because pandemic

disasters are unique and do not include congregate sites for prolonged support and recovery, they

require specific response strategies to ensure the behavioral health needs of children and families.

Pandemic planning must address these needs and disease-containment measures. (Disaster Med

Public Health Preparedness. 2013;7:105-110)

Key Words: PTSD, pandemic, psychosocial, disasters

P

andemic disasters have been a part of human to pandemics appear in either. While the recommen-

history for centuries, and while recent out- dations of these reports are important and useful, they

breaks have been either extremely mild or fail to address some of the most unique contributing

quickly contained, experts predict that a major factors of adverse mental health responses to pandemics.

pandemic with projected morbidity rates from 18 to

100 million and projected death rates ranging from It is true that pandemics have much in common with

89 000 to 207 000 will occur sometime during the other disasters: community impact, unpredictability,

next century.1,2 Of note is the shift in mortality and fatalities, and persistent effects. Response to pandemics

morbidity to younger age groups, which has been necessarily differs from that of other disasters by

notable in both seasonal influenza and the recent discouraging convergence and gathering of victims;

influenza A (H1N1) pandemic.3-5 High rates of instead, the exact opposite—separation, isolation,

pediatric infection are predicted for future pandemics,3 and quarantine—is demanded. While such disease-

and children will continue to be both victims of illness containment measures may quell the outbreak, they

and vectors of transmission. However, while pediatric have the unintended consequence of inhibiting family

deaths may be numerous, equally important is poten- rituals, norms, and values, which regulate and protect

tially high pediatric morbidity: many more children will family functioning in times of crisis.8 Relational

live through such illnesses. Pandemic planning, there- functioning among family, community, and peers

fore, must consider the needs of those children and their influences individual resilience,9 and the inhibition

families, ensuring that they do not suffer long-term or interruption of such functioning may both diminish

trauma from either the experience of pandemic illness or individual and family resilience and increase the

public health response strategies. potential for adverse reactions.10 As Masten and

Obradovic wrote about pandemic illness, ‘‘families

The unique and specific needs of children during often infect each other before any individual is

disasters have recently been documented in the diagnosed, they also infect each other with fear’’ (p 9).

findings of the National Commission on Children During a pandemic, family and community response

and Disasters6 and an earlier report from the National strategies and resulting regulatory actions will significantly

Center for Disaster Preparedness,7 but little reference influence the health and functioning of individuals,

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 105

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. The University of Iowa, on 30 Mar 2020 at 12:29:35, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

Copyright & 2013 Society

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. for Disaster Medicine and Public Health, Inc. DOI: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22

https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22

Posttraumatic Stress in Parents and Youth

families, communities, and the nation. Population health, in Parents were recruited for surveys through broad-based print

its broadest sense, is best served by carefully considering all (via major newspapers in the targeted regions) and website

areas of need for children and families in pandemic disaster advertising and flyers distributed in health departments,

preparedness. private and public medical offices, conferences, and work-

shops. Recruitment ads ran for 1 month during the data

Deleterious effects of pandemic and pandemic response collection period, and provided a link to a web-based survey.

strategies occurred after the outbreak of severe acute respiratory A waiver of consent was obtained from the University of

syndrome (SARS) among patients and hospital workers.11,12 Kentucky Institutional Review Board, but participants were

Family-centered care, a hallmark of pediatric crisis response, was asked to check a box agreeing to participation after reading

abandoned, with detrimental effects on patients, families, and an informed consent document, which then routed them

caregivers.13,14 The incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder automatically to the survey. A series of screening questions at

(PTSD) after the SARS pandemic in Canada was found to be the beginning of the survey linked parents to an appropriate

similar to that of natural disasters and terrorism (28.9%);15 set of questions based on their experiences with pandemic

however, critics argue that little improvement in pandemic quarantine or isolation. The survey was completed by 398

planning has occurred, even in Canada, since then.16,17 participants; each was offered $10 as incentive payment via a

‘‘request for incentive’’ page that was accessible only at the

Even milder pandemics have demanded an examination of end of the survey and that was unlinked to the responses.

their psychosocial effects. Following the H1N1 pandemic, the

World Health Organization noted: Measurements

A mixed method approach used surveys, focus groups, and

A large amount of information about the natural history

and clinical management of 2009 H1N1 virus infection interviews for data collection to support a convergence

approach to understanding the data regarding the emerging

has been obtained in a remarkably short period of time,

outbreak. The process of measurement development

but considerable gaps remainy.public health efforts to

respected standard social science research requirements for

reduce risk factors and to identify at-risk populations y

psychometric construction, including attention to question-

should focus on social as well as clinical factors.17

ordering effects, item exclusivity, and clear and consistent use

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has of key terms. Focus group and interview instruments used a

recently acknowledged that ‘‘mental health is part of the semistructured interview schedule according to recommended

mission’’ of addressing communicable disease18 and should approaches.19

serve as a model for public health. To that end, this report

examines rates of PTSD symptoms in parents and children The parent survey included multiple choice questions, a

who self-identified as having exposure to pandemic condi- rating scale, and open-ended questions about experiences and

tions. Specifically, this study hypothesizes that disease- anticipated areas of need during the pandemic, experiences

containment efforts will negatively impact parent and child with quarantine or isolation, sources of and trust in

mental health, as evidenced by increased symptoms of PTSD. information, and perceptions of risk. It also included the

Further explication of the biopsychosocial response of those parent-report version of the University of California at Los

exposed to pandemic disasters is the first step toward Angeles Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index

developing best practice approaches to planning, response, (PTSD-RI), and the PTSD Check List - Civilian Version

and recovery for children and families. (PCL-C). The PTSD-RI is a 48-item scale measuring parent

reporting of a child’s symptoms of trauma. Parents rated the

frequency of PTSD symptoms during the previous month

METHODS (from 0 5 none of the time to 4 5 most of the time). These

Sample items map directly onto the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Data were collected from 586 parents who completed a survey of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) PTSD criteria

in the Spring of 2009 about their experiences with pandemic B (intrusion), C (avoidance/numbing), and D (arousal). Of

illness. A ‘‘follow-the-virus’’ sampling method was developed these items, 20 assess PTSD symptoms; 2 additional items

to identify potential respondents, with an emphasis on areas assess associated features—fear of recurrence and trauma-

most severely impacted by H1N1, particularly those that related guilt. Developed by Pynoos et al20, it has strong

experienced high rates of pediatric illness and mortality. This sensitivity and specificity, validity, and internal consistency.

method yielded 5 sample states: Arizona, California, Florida, The PCL-C is a 17-item self-report that can be used

New York, and Texas. In addition, Kentucky was designated for PTSD screening, diagnosis, or symptom monitoring.

a sample site based on proximity and its role as the pilot state. Developed by Weathers and colleagues,21 the civilian version

Two locales in Mexico were sampled, Mexico City and can be applied generally to any traumatic event and is easily

Juarez, as Mexico was the site of the original H1N1 outbreak. modified to fit specific time frames or events. It is self-

Also, Toronto, Canada, was targeted to provide comparative administered and requires respondents to rate how often they

data to the experience and impact of SARS. have been bothered by PTSD symptoms using a 5-point scale

106 Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness VOL. 7/NO. 1

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. The University of Iowa, on 30 Mar 2020 at 12:29:35, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22

Posttraumatic Stress in Parents and Youth

(from 1 5 not at all to 5 5 extremely). It has been shown to a score of 25 indicated probable PTSD, and a score of

be valid and reliable, and the instrument is available in the 30 indicated a diagnostic threshold for PTSD was met.

public domain. Of parents who experienced quarantine or isolation, 25% had

a PTSD screening score of 25 or greater, indicating that they

These measurements were available online (Survey Monkey) were at risk for PTSD; 28% had scores of 30 or greater,

and on paper, along with demographic items regarding gender, meeting the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Only 7% of the

age, type of exposure to disease, containment procedures (none, parents who did not experience social distancing through

isolation, or quarantine), location of residence (by state), isolation or quarantine had a severity score of 25 or

mental health services used as a result of the pandemic (yes, no, greater, and only 5.8% scored above 30. Further analysis

prefer not to respond), and open-ended questions regarding found that these differences in meeting criteria for PTSD

participation in follow-up interviews and focus groups. All were significant (x2 5 31.411, P , .001). Analysis using an

research instruments and consent forms for parents living independent samples t test found significant differences

in the United States and Canada were in English. All between the mean scores of parents who did (M 5 46.67)

research instruments and consent forms for Spanish-speaking and did not experience isolation or quarantine (M 5 39.77)

populations were translated by professional translators and (t 5 2.39, P 5 .020).

reviewed for content integrity and comprehension by the

project’s cultural consultant who is a native of Mexico City and Traumatic stress in children was measured by parent reporting

a long-time resident of the Juarez area. on the PTSD-RI, and significant differences were also found

between those who experienced social distancing measures

and those who did not. Children who experienced isolation

RESULTS or quarantine were more likely to meet the clinical cutoff

The parent sample was predominantly female (78%), White score for PTSD (30%) than those who had not been in

(66.1%), and aged from 18 to 67 years (mean age, 37 years). isolation or quarantine (1.1%; x2 5 49.56, P , .001, Cramer

More than half were employed full time, although 40% reported V 5 .449). Further analysis using independent samples t test

average annual household incomes of less than $50 000. Parents revealed a significant difference in mean scores between the

from all target areas participated; most were urban or suburban 2 groups (t 5 6.59, P 5 .000), with the mean of the isolated

dwellers (87%). Respondents came from all 6 target states, and quarantined groups (22.3) 4 times higher than that of the

Mexico, and Canada. When asked to name the most serious general group (5.5). In addition, the respondents in the

pandemic event they or someone in their immediate family had quarantined and/or isolated groups indicated that their child

experienced, 91% answered H1N1, with 8% reporting SARS met the PTSD criteria for the subscales of avoidance/

and 1% identifying avian influenza. Regarding disease contain- numbing (57.8%), re-experiencing (57.8%), and arousal

ment experiences, 20.9% reported that they were ordered into (62.5%) at high rates.

isolation, 3.8% reported being quarantined, and 75% reported

no quarantine or isolation experience. Examination of PTSD symptoms in parents and children

within the same family revealed a significant relationship

Regarding mental health service use, clear differences were between the 2: of parents meeting PTSD cutoff levels, 85.7%

seen in utilization patterns between isolated and quarantined had children also meeting clinical cutoff scores for PTSD,

families and those with no containment experience. while among parents not meeting PTSD criteria, only 14.3%

A substantial number of parents who were quarantined or had children with PTSD symptoms (x2 5 65.91, df 5 1,

isolated (44.4%) reported that their children did not receive P 5 .000 and Cramer V 5 .518).

mental health services. However, 33.4% said that their

child/children began using mental health services, either PCL-C Scores for Parents

during or after the pandemic, related to their experience. The One-way ANOVA post hoc Tamhane tests for the PCL-C

most common diagnoses were acute stress disorder (16.7%), revealed that women reported significantly higher rates of

adjustment disorder (16.7%), and grief (16.7%). Only 6.2% PTSD than men. The overall ANOVA was not significant

of these children were diagnosed with PTSD. Conversely, (P 5 .21) for location of residence; therefore, no post hoc

93.2% of parents who completed the general survey reported tests were investigated. Parents with disease-containment

that their children did not receive mental health services experience had significantly higher rates of PTSD than those

related to the pandemic. Of the youth who received services who were not quarantined or isolated. A correlational analysis

either during or after the pandemic, the most common diagnoses between age and total PTSD score revealed a significant

were generalized anxiety disorder (20%) and adjustment disorder negative correlation (r 5 -.34, P , .000) suggesting that younger

(20%), with 1.4% receiving a PTSD diagnosis. parents had higher rates of posttraumatic stress on the PCL-C.

Traumatic Stress Responses Table 1 displays the standardized regression coefficients (b),

PTSD in parents was measured based on scores meeting the DR2, and indicators of individual variable significance after

clinical cutoff point on the PCL-C. For screening purposes, sequential entry of all predictors. After step 1, with gender

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 107

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. The University of Iowa, on 30 Mar 2020 at 12:29:35, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22

Posttraumatic Stress in Parents and Youth

TABLE 1 TABLE 2

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting

PCL-C Scores (N 5 378) PTSD-RI Scores (N 5 369)

Predictor DR2 b Predictor DR2 b

a a

Step 1 .21 Step 1 .11

Gender .24a Gender .13

Age -.19a Age -.16a

Step 2 .01 Step 2 .00

Location Location

Kentucky Kentucky

California .06 California .11

Florida .09 Florida .09

Arizona .07 Arizona .07

New York .11 New York .06

Texas .06 Texas .08

Step 3 .23a Step 3 .33a

Disease-containment groups Disease-containment groups

None None

Isolation -.15a Isolation -.25a

Quarantine -.19a Quarantine -.19a

Total R2 .45a Total R2 .44a

Abbreviation: PCL-C, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Check List - Civilian Abbreviation: PTSD-RI, University of California at Los Angeles

Version. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index.

a a

P ,.001. P ,.001.

and age in the equation, R2 5 .21, Finc (1, 367) 5 19.63, and Qualitative Responses

P , .001. After step 2, with residential location added to Qualitative data from interviews with parents who were affected

PCL-C score with age and gender, no significant contribution by pandemic illness provide insight into possible psychosocial

to R2 was noted (R2 5 .22, Finc [2, 367] 5 3.25, P 5 .06). impact of pandemic on children and their parents and highlights

After step 3, with disease-containment group added to the the perceived threat, confusion, disruption, and isolation

PCL-C scores above and beyond gender, age, and living imposed by this type of health-related crisis.

location, R2 5 .45, Finc (4, 367) 5 31.76, and P , .001, The kids’ anxiety was the hardest thing to deal withy

indicating a reliably increased R2. my daughter said, ‘‘Mommy, are you going to die?’’ and

that was absolutely heartbreaking.

PTSD-RI Scores for Trauma Symptoms in Children I stayed away from everyone. I didn’t know if it could

One-way ANOVA post hoc Tamhane tests for the PTSD-RI happen, but I had heard a lot about people dying from

disclosed that parents reported no gender differences in this H1N1y my daughter was so upset! She thought

posttraumatic stress symptoms based on the gender of their I didn’t want to be near her.

children. The overall ANOVA was not significant (P 5 .53)

for location of residence; therefore, no post hoc tests were One healthcare worker noted the relationship disruption

investigated. Parents with disease-containment experience imposed by her professional role.

reported higher levels of posttraumatic distress in their I’m now suddenly working 20 hours a day and isolating

children than those without quarantine or isolation experi- myself, and away from them, and wearing a mask when

ence. No significant correlation was found between parent we’re close and not hugging and not sleeping, they can’t

age and PTSD-RI scores (r 5 .08, P 5 .09). crawl into bed with you. That was tough, that was the

toughest, the hardest party.

Table 2 displays the standardized regression coefficients (b),

One father who was hospitalized with a serious case of H1N1

DR2, and indicators of individual variable significance

explains:

after entry of the predictor variables in the PTSD-RI model.

After step 1, with gender and age in the equation, R2 5 .11, My children were scared. There was no time for good-

Finc (2, 364) 5 15.11, and P , .001. After step 2, with living byes or (to) tell them why. I did not know if I would see

location added to age and gender, no significant contribution them again.

to R2 was noted (R2 5 .11, Finc [2, 362] 5 3.44, P 5 .07). After

step 3, with the disease-containment group added to gender, DISCUSSION

age, and living location, R2 5 .44, Finc (4, 365) 5 33.87, and Parents reported that the pandemic had a significant impact

P , .001, indicating a reliably increased R2. on their child’s mental health. In this study, nearly one-third

108 Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness VOL. 7/NO. 1

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. The University of Iowa, on 30 Mar 2020 at 12:29:35, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22

Posttraumatic Stress in Parents and Youth

of the children who experienced isolation or quarantine When no sites for triage are indicated in a pandemic,

demonstrated symptoms that met the overall threshold for PTSD pediatric health care workers are best suited to conduct

and showed significantly higher rates of PTSD symptoms on all screening for traumatic stress symptoms in affected children and

subscales. The estimated prevalence of PTSD in the general families. However, these professionals may need formal training

population for children varies, but a telephone survey based on in administering the tools; facilitating appropriate referrals

a national sample of 4023 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years based on the results; and using evidence-informed responses

indicated a lifetime prevalence of 8.1%.22 In a community to address those at elevated risk of traumatic stress response.

sample of older adolescents, 14.5% of those who experienced These responses should include a range of interventions from

a serious trauma developed PTSD.23 A review of children psychoeducation and prevention education (eg, normal and

exposed to specific traumas found wide ranges in rates of PTSD abnormal responses to pandemic, symptoms of traumatic stress,

diagnoses: 20% to 63% in survivors of child maltreatment, red flags, familial response strategies, and preventive measures)

12% to 53% in the medically ill, and 5% to 95% in disaster to community service referrals (medical, mental health, and

survivors.24 Results indicated that isolated and quarantined social services) and trauma-focused therapy.

children in our sample met the criteria for PTSD at rates closer

to children who have experienced disasters and other serious

traumatic events. Documented rates of PTSD after exposure to Limitations

isolation and quarantine experiences suggested a trauma-informed Survey research that provides high reliability and standardiza-

approach to understanding the biopsychosocial reactions tion in data collection is ideal for comparing responses across

to pandemics, indicating subsequent disease-containment groups. However, this approach presents some challenges.

measures. This finding appears especially important, because This study relies on a parent’s retrospective perception of

more than two-thirds of those meeting the diagnostic feelings and behaviors associated with a stressful experience;

threshold by self-report and parent report were identified as as such, responses are potentially flawed by recall bias and

suffering from PTSD when seeking treatment services from social desirability. Furthermore, the parents’ subjective level

community providers. of distress may interfere with their perceptive capacities

regarding their child’s symptoms and functioning. Because

A strong relationship was found between clinically-significant parent-child discrepancies in reporting appear most evident

levels of PTSD symptoms in parent respondents and their in clinical populations,28 the role that traumatic stress

children. Among adult respondents who met the clinical reactions may have played in the parents’ identification and

cutoff score for PTSD, nearly 86% had children who also met awareness of symptoms should be the focus of future research.

the clinical cutoff score. The finding that many parents and Also, the respondents who completed the online survey

children simultaneously meet PTSD criteria also strongly suggests represent a self-selected group who may have had a special

that public health professionals and behavioral health profes- interest in the topic; therefore, the generalizability of the results

sionals conducting postpandemic surveillance for mental is guarded. However, the disease-containment experiences of

disorders, and behavioral health professionals conducting the respondents varied, and they approximated isolation and

diagnostic screening, should consider that identification of quarantine practices used by the general population.27

PTSD in parents should trigger an investigation for behavioral

health disorders in their family members.

CONCLUSIONS

These tools can easily be integrated into the standard Pandemics are infrequent but potentially devastating

public health response to a pandemic: Available screening crises that are likely to affect the lives of many children

tools have between 4 and 19 questions, take an average of and their families physically, socially, and psychologically.

30 to 40 seconds to complete, may be administered by a range Responders in public health, health care, and behavioral

of professionals and para-professionals, and are free and health must collaborate during pandemics to ensure that

publicly available (see www.nctsn.org). Further, using a disease-containment measures are understood and implemen-

screening tool for traumatic stress enables comparison of ted in a manner that minimizes the potential for negative

symptom profiles at different times for the same client and psychosocial consequences in children and families. Use of

between individuals and groups of clients based on estab- a traumatic stress framework for organizing the response

lished national norms. Integration of this trauma screening is a first step toward providing evidence-informed care to

tool into pediatric health care settings can be accomplished survivors of pandemics.

with little impact on service providers or patients. In fact,

pilot testing an adult trauma screening tool and a child About the Authors

trauma screening tool during a peak rush period University of Kentucky, College of Medicine, Center on Trauma and Children,

in a rural health department revealed that they were easily Lexington, Kentucky (Dr Sprang and Ms Silman).

administered (on average, taking less than 1 minute), Address correspondence and reprint requests to University of Kentucky, Center on

integrated easily into intake protocols, and well-received by Trauma and Children, 3470 Blazer Pkwy, Ste 100, Lexington, KY 40509

subjects, with no refusals to participate.25 (e-mail: sprang@uky.edu).

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 109

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. The University of Iowa, on 30 Mar 2020 at 12:29:35, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22

Posttraumatic Stress in Parents and Youth

Acknowledgements 12. Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and

The authors would like to acknowledge research team members James Clark, occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital.

Ph.D., Phyllis Leigh, CSW, A. Scott LaJoie, Ph.D. and Candace Jackson, CMAJ. 2003;168(10):1245-1251.

CSW and Gerardo Rosas, LPC, Cultural Consultant, who participated in the 13. Nicholas DB, Koller D, Gearing RE. The experience of SARS

larger data collection effort from which this study was extracted. from a pediatric perspective. Ontario Lung Association UPDATE. 2003;

19(3):10.

14. Nicholas DB, Gearing RE, Koller D, Salter R, Selkirk EK. Pediatric

Funding and Support

epidemic crisis: lessons for policy and practice development. Health

Funding was provided in support of community and business resilience by

Policy. 2008;88(2-3):200-208.

the Kentucky Critical Infrastructure Protection Program, managed by the

15. Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R.

National Institute for Hometown Security for the US Department of

SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada.

Homeland Security.

Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206-1212.

Received for publication July 9, 2012; accepted September 10, 2012. 16. Nicholas D, Patershuka C, Koller D, Bruce-Barrett C, Lache L,

Zlotnik Shaulf R, Matlow A. Pandemic planning in pediatric care: A

website policy review and national survey data. Healthcare Policy. 2010;

REFERENCES 96(2):34-142.

17. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of

1. Chen H, Deng G, Li Z, et al. The evolution of H5N1 influenza viruses in Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza; Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T,

ducks in southern China. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(28): et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus

10452-10457. infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1708-1719.

2. McKibbin WJ, Sidorenko AA. Global Macroeconomic Influences of 18. Safran MA. Achieving recognition that mental health is part of the

Pandemic Influenza. Sidney, Australia: Lowy Institute for International mission of CDC. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(11):1532-1534.

Policy; 2006. 19. Ehrmann S, Etter Zúñiga R. The FlashlightTM Evaluation Handbook.

3. Miller MA, Viboud C, Blainska M, Simonsen L. The signature Washington, DC: The TLT Group; 1997: 357-361.

features of influenza pandemic: implications for policy. N Engl J Med. 20. Pynoos R, Rodriguez N, Steinberg A, Stuber M, Frederick C. UCLA

2009;360(25):2595-2598. PTSD Index for DSM IV (Child Version). Los Angeles, CA: UCLA

4. Relman DA, Choffnes ER, Mack A. The Domestic and International Trauma Psychiatry Services; revision 1, 1998; 2001.

Impacts of the 2009 H1N1 Influenza A Pandemic. Washington, DC: 21. Weathers F, Huska J, Keane T. PTSD Checklist (PCL). Washington, DC:

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2010. National Center for PTSD, US Department of Veterans Affairs; 1991,

5. Woods CR, Abramson JS. The next influenza pandemic: Will we be revised 1994.

ready to care for our children? J Pediatr. 2005;147(2):147-155. 22. Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Smith DW. Research in Brief: Youth

6. National Commission on Children and Disasters. Progress Report on Children Victimization: Prevalence and Implications. Washington, DC: US Depart-

and Disasters: U.S. Agencies Take Modest Steps to Achieve Mission Goal. ment of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2002.

Washington DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. 23. Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, Pakiz B, Frost AK, Cohen E.

7. Markenson D, Redlener I. Pediatric preparedness for disasters and terrorism. Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of

Presented at the National Consensus Conference. New York, NY: older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(5):

National Center for Disaster Preparedness, Mailman School of Public 599-611.

Health. March 2007. 24. Gabbay V, Oatis MD, Silva RR, Hirsch G. Epidemiological aspects of

8. Fiese BH, Spagnola M. The interior life of the family: looking from the PTSD in children and adolescents. In: Silva RR (ed). Posttraumatic Stress

inside out and the outside in. In: Masten AS, ed. Multilevel Dynamics Disorder in Children and Adolescents: Handbook. New York, NY: Norton;

in Developmental Psychopathology: Pathways to the Future. New York, NY: 2004:1-17.

Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007:119-150. 25. Sprang G, Clark J, LaJoie A, Leigh P, Silman M, Jackson C. Best

9. Luthar SS. Resilience in development: a synthesis of research across Practice Guidelines for Pandemic Disaster Response: Response from the

five decades. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ (eds.). Developmental Field (Part 2). Somerset, KY: National Institute for Hometown

Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Security; 2001.

John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006:739-795. 26. Barbosa J, Tannock R, Manassis K. Measuring anxiety: parent-

10. Masten AS, Obradovic J. Disaster preparation and recovery: lessons from child reporting differences in clinical samples. Depress Anxiety. 2002;

research on resilience in human development. Ecology Soc. 2008;13(1):9. 15(2):61-65.

11. Blendon RJ, Koonin LM, Benson JM, et al. Public response to 27. Mubayi A, Zaleta C, Martcheva M, Castillo-Chavez C. A cost-based

community mitigation measures for pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect comparison of quarantine strategies for new emerging diseases. Math

Dis. 2008;14(5):778-786. Biosci Eng. 2010;7(3):687-717.

110 Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness VOL. 7/NO. 1

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. The University of Iowa, on 30 Mar 2020 at 12:29:35, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Schalms Veterinary Hematology 7Th Edition Marjory B Brooks All ChapterDocument67 pagesSchalms Veterinary Hematology 7Th Edition Marjory B Brooks All Chapterefrain.blair179100% (13)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Persuasive Analytical Essays: Nguyen Khanh Huy EAP1119.5BDocument3 pagesPersuasive Analytical Essays: Nguyen Khanh Huy EAP1119.5BKhánh Huy NguyễnNo ratings yet

- 06 237046 001 - BDDocument1 page06 237046 001 - BDcarlos yepezNo ratings yet

- Existing Plumbing Floor Plan - Water 1 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0" Existing Plumbing Floor Plan - Sanitary 2 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Document1 pageExisting Plumbing Floor Plan - Water 1 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0" Existing Plumbing Floor Plan - Sanitary 2 P-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- EXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0": Electrical Riser DiagramDocument1 pageEXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0": Electrical Riser DiagramRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- NW 7 AVE-A1 - FlattenedDocument1 pageNW 7 AVE-A1 - FlattenedRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- NOT MODIFIED IN The Hatch Selection: Date Revision NODocument1 pageNOT MODIFIED IN The Hatch Selection: Date Revision NORaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- Electrical Riser Diagram: EXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Document1 pageElectrical Riser Diagram: EXISTING Electric Floor PLAN 1 E-1 SCALE: 3/16" 1'-0"Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- 890 SW 87 Ave-E1Document1 page890 SW 87 Ave-E1Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- 2916-E1 FlattenedDocument1 page2916-E1 FlattenedRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- 2007 Zeisel Inquiry by Design Review 2007Document3 pages2007 Zeisel Inquiry by Design Review 2007Raúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- Detail "A" Roof Penetration: Roof Mounted Make Up Air Hood Guy Wire Connection To Bar JoistDocument1 pageDetail "A" Roof Penetration: Roof Mounted Make Up Air Hood Guy Wire Connection To Bar JoistRaúl Carbonell HerreraNo ratings yet

- La Consolacion College Manila: Report On Learning Progress and AchievementDocument2 pagesLa Consolacion College Manila: Report On Learning Progress and AchievementBryle Garnet FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Procedure Sick Bay 2017Document6 pagesProcedure Sick Bay 2017Syed FareedNo ratings yet

- Technical Specification For Sorghum GrainsDocument6 pagesTechnical Specification For Sorghum GrainsMohd SaifulNo ratings yet

- Name of Infection/virus Acquired at What Time How To Test For It Likely S/s HSVDocument1 pageName of Infection/virus Acquired at What Time How To Test For It Likely S/s HSVC RNo ratings yet

- List of Periodic Checks Life Saving & Fire Fighting EquipmentDocument5 pagesList of Periodic Checks Life Saving & Fire Fighting EquipmentSandro CheNo ratings yet

- Exp. (3) Comparing Specific Heat of Water and Vegetable Oil: Year Mr. Mohammed MahmoudDocument17 pagesExp. (3) Comparing Specific Heat of Water and Vegetable Oil: Year Mr. Mohammed Mahmoudجیهاد عبدالكريم فارس0% (1)

- SA2 2014 English Course - ADocument8 pagesSA2 2014 English Course - AsunnyNo ratings yet

- Line and Cable ModellingDocument23 pagesLine and Cable ModellingarunmozhiNo ratings yet

- Conservation of A Neolithic Plaster StatueDocument1 pageConservation of A Neolithic Plaster StatueJC4413No ratings yet

- TI Furadur Kitt 322 - enDocument3 pagesTI Furadur Kitt 322 - engonzalogvargas01No ratings yet

- Specimen Cover Letters and Job Application LettersDocument4 pagesSpecimen Cover Letters and Job Application LettersVthree YsNo ratings yet

- Implementing A Digital Transformation: November 2018Document5 pagesImplementing A Digital Transformation: November 2018Hasti YektaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Pipe NetworksDocument14 pagesAnalysis of Pipe NetworksAhmad Sana100% (2)

- 1 Bengaluru Urban Dist:: Sl. No. Industrial Area Date of Revision (B.M.Date) Prevailing Price/Acre (Rs. in Lakhs) 1 2 3 4Document8 pages1 Bengaluru Urban Dist:: Sl. No. Industrial Area Date of Revision (B.M.Date) Prevailing Price/Acre (Rs. in Lakhs) 1 2 3 4Raju BMNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Operation Assembly Repair Inspection of HM Cargo Tanks June 09 508Document105 pagesGuidelines For Operation Assembly Repair Inspection of HM Cargo Tanks June 09 508paulon9271No ratings yet

- (PPT) Anatomy 2.5 Lower Limbs - Blood and Nerve Supply - Dr. Tan PDFDocument110 pages(PPT) Anatomy 2.5 Lower Limbs - Blood and Nerve Supply - Dr. Tan PDFPreeti Joan BuxaniNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheets English 2, Quarter 3, Week 1Document11 pagesLearning Activity Sheets English 2, Quarter 3, Week 1CHERIE LYN TORRECAMPONo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management - Pgfa1941Document9 pagesSupply Chain Management - Pgfa1941Ravina SinghNo ratings yet

- Nandha Engineering College (Autonomous) : 17mex12 - Internal Combustion EnginesDocument36 pagesNandha Engineering College (Autonomous) : 17mex12 - Internal Combustion EnginesSugumar MuthusamyNo ratings yet

- 501c3.guidelines Issued by The IRSDocument31 pages501c3.guidelines Issued by The IRSThe Department of Official InformationNo ratings yet

- 4.1overview of Preventive MaintenanceDocument32 pages4.1overview of Preventive MaintenanceVANESSA ESAYASNo ratings yet

- Histology EssayDocument4 pagesHistology EssayalzayyanauroraNo ratings yet

- Goonj..: Making Clothing A Matter of Concern.Document46 pagesGoonj..: Making Clothing A Matter of Concern.sharat2170% (1)

- Jung Typology TestDocument2 pagesJung Typology TestPhuong Thanh ANNo ratings yet

- School Orientation Narrative Report 1Document2 pagesSchool Orientation Narrative Report 1Marry Joy Molina100% (5)

- Short Catalog 160719 HRDocument30 pagesShort Catalog 160719 HRtuanudinNo ratings yet

- Contents and Front Matter PDFDocument13 pagesContents and Front Matter PDFAbdelrhman MadyNo ratings yet